- 1Independent Researcher, Trondheim, Norway

- 2Department of Sociology and Political Science, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim, Norway

In spring 2020, shortly after the outbreak of the Coronavirus diseases 2019 (COVID-19), Norway introduced the digital contract tracing app “Smittestopp” (“Stop infection”) as a measure to combat the pandemic. The launch was accompanied by scientific uncertainties about the technology: the app had been developed at lightning speed and hardly been tested, and its effects were unclear. It did not become a success, was strongly underused and soon had to be discontinued due to privacy issues. Our study starts from the assumption that in this situation of uncertainty about the technology, combined with and resulting from a lack of user experience, the app's public portrayal was a decisive factor for this outcome. We investigate the framing of “Smittestopp” in press releases by Norwegian public authorities and in news articles. By means of a qualitative content analysis, we identify 11 frames and uncover the opposition between health considerations and privacy concerns as central conflict line. In their press releases, the public authorities did not use frames very strategically. The news media provided diverse frames but at the same time focused relatively strongly on privacy issues that ultimately led to the app's discontinuation.

1 Introduction

When the Coronavirus diseases 2019 (COVID-19) hit the world, no cure or vaccine was available yet. The measures to limit its spread included face masks, reducing social contacts, isolation of infected people, and tracking their contacts. Digital contact tracing (DCT) apps quickly became a strategy to keep the pandemic under control. DCT can through smartphones identify people who may have encountered an infected person (Lapolla and Lee, 2020). Frequently mentioned advantages of DCT are that it is more efficient than manual infection tracing (Thayyil et al., 2020) and allows even alerting contacts an infected person does not know or remember to have met. The professional debate about the effectiveness of DCT, however, suggests that the technology can at best be an additional tool for manual infection detection (e.g., Barrat et al., 2020; Thayyil et al., 2020). The downsides of DCT include that it requires collecting sensitive personal information that could threaten privacy, equality, and justice (Morley et al., 2020) and that the surrounding infrastructure can become victim to cyber-attacks (Lapolla and Lee, 2020).

Under the COVID-19 pandemic, many countries introduced newly developed DCT apps while still lacking experience with this new, health-relevant technology. One of them was Norway which quickly had its own app available—“Smittestopp” (“Stop infection”), developed by the state-owned research institute Simula on behalf of the Norwegian Institute of Public Health (NIPH). It was launched on April 16th, 2020, only about 1 month after the lockdown, without time for intense pretesting. Having the risks described above in mind, this can bring along scientific uncertainties about the technology. When authorities launch a service collecting sensitive personal data, risks must be comprehensively assessed and carefully communicated to the citizenry, even in an exceptional situation such as a pandemic when time is short (Morley et al., 2020).

A controversial public debate arose around “Smittestopp” which set up the app's health benefits, advocated by NIPH, against privacy concerns, represented by the Norwegian Data Protection Authority (DPA). One main concern was that the app sent the data from the users' phones to a central database controlled by the NIPH which allowed to find the contacts of infected people but could also have been misused for surveillance. More than 300 academics advocated for a decentralized system which should store the data locally on the users' phones and only share information about close contacts of infected persons with the health authorities (Metzler and Åm, 2022). Already on June 15th, 2020, the DPA announced a temporary ban on the app (DPA, 2020). The NIPH's response was to delete the already collected data, to stop collecting new data, and to make the app unavailable for download (NIPH, 2020). In September 2020, the NIPH introduced an improved second version which took care of the privacy concerns but did not become a success either.

Given the novelty of “Smittestopp” and the uncertainty around the technology and its consequences, its presentation in the public debate may have influenced its acceptance in Norway. When considering to use the app or not, the population had to rely its risk assessment strongly on publicly available information, both from public authorities (such as NIPH and DPA) and the news media. Such a situation entails a potential for so-called frame building, that is, the creation of new frames (Scheufele, 1999), which can have affected the success of the app. By means of a qualitative content analysis, we investigate how the first version of “Smittestopp” was framed in press releases by the NIPH and the DPA as well as the coverage of three leading Norwegian news media.

Norway is an interesting case to investigate this. The Norwegian population traditionally shows a high level of trust in political institutions (Kleven, 2016). By the end of 2019, shortly before the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, a vast majority of Norwegians (84%) expressed trust toward the health system concerning the storage and usage of personal data, compared to only around 10% toward search engines, social media, messenger apps, and online shops (Datatilsynet, 2020). However, despite both the government and the NIPH as highly respected public authorities strongly recommended to use “Smittestopp,” people were quite hesitant in to do so, and it might have become a failure even without the interventions by the DPA. Our suspicion is that this was also due to communication problems during the launch of the app, which underlines the relevance of our study. We focus on the first version of the app which was much more heatedly debated in the Norwegian public than the second version (which was even less used, possibly because people had already lost trust in the app and faith in its usefulness with the first version).

We approach scientific uncertainties about issues that impact human health primarily in the sense of uncertainties about the newly developed technology (the app) and how they were communicated in public. Besides that, our study touches the concept of uncertainty in two more senses: uncertainties about the science of the disease/pandemic and uncertainties about how the general public would respond to both the pandemic and the technology.

Our contribution is threefold: (1) Taking a cutting-edge, underresearched topic (news coverage on DCT apps) as an example, our qualitative approach to framing allows for an in-depth, context-sensitive identification of all frames contained in the materials. (2) Therewith, our case study contributes to our understanding of how new technologies and the related uncertainties are presented in public communication, which can shape their public perception. (3) Our study helps to better understand the app's failure, which can contribute to avoiding possible mistakes in the future when communicating uncertainties resulting from new technologies, for example in future pandemics.

2 Conceptual framework

2.1 Framing and frame building

Framing research is a scattered field that lacks a clear operationalization of the concept (e.g., Scheufele, 1999; de Vreese, 2005; Matthes, 2009). We base our study on a widely used definition by Entman (1993): “To frame is to select some aspects of a perceived reality and make them more salient in a communicating context, in such a way as to promote a particular problem definition, causal interpretation, moral evaluation, and/or treatment recommendation for the item described” (Entman, 1993, p. 52). Thus, a frame consists of four elements, even though not all of them must be addressed for a frame to be present: the problem definition contains the main problem in the text. It is often measured in relation with the most important actors discussing it. The causal interpretation is about reasons and those who are responsible for the risks or benefits of the problem. The moral evaluation can be positive, negative, or neutral, and assesses the risks and benefits. The treatment recommendation includes a call to action (Matthes and Kohring, 2008).

Traditionally, framing studies were based on coding pre-defined frames (e.g., Semetko and Valkenburg, 2000). However, that resulted in the problem that they were only able to find frames they were looking for but not to uncover new ones. Matthes and Kohring (2008) addressed this core problem by a more open, inductive approach. They suggested to code the four frame elements separately in order to uncover frames that are composed of them by means of cluster analysis afterwards. However, also their quantitative approach requires pre-defined frame elements, which entails the danger of overlooking aspects that were not considered beforehand. This risk seems particularly large with new topics such as DCT apps. Therefore, we start a step earlier with the goal of identifying all frame elements occuring in the material by means of a qualitative approach.

The literature distiguishes two types of frames both of which have their justification, dependent on the research interest: generic frames are common, overarching frames (e.g., responsibility, human-interest, conflict, moral, and economic consequences frame) which can be used independent of the topic (Semetko and Valkenburg, 2000). This increases cross-study comparability but at the cost of ignoring issue-specific characteristics. Thematic frames are topic-dependent (de Vreese, 2005) and allow for more accurate descriptions of coverage on specific issues but at the cost of reduced transferability to other contexts. Since our study focuses on a specific topic, we follow the thematic framing approach.

Framing research has strongly focused on how the news media frame current issues (news framing), which provides the recipients with context that helps them to understand a phenomenon or a case (de Vreese, 2005). The process of how news frames are created is called frame building (Scheufele, 1999). It is influenced both by the news media themselves (e.g., media types, political orientation) and by external powerful actors (frame sponsors) such as political actors, authorities (e.g., NIPH, DPA), or interest groups who have an interest in pushing forward certain frames representing their positions. Scheufele (1999) assumes that frame building is particularly strong in case of new phenomena when no frames have been established yet, such as in case of “Smittestopp.” A central channel of communication from public authorities to the news media are press releases. Here, they can present their position on current issues in an unfiltered way. Therefore, we consider press releases a good means to examine what frames the authorities were trying to build around “Smittestopp.”

2.2 State of research

The news media are one of the most central sources when it comes to public information, confidence, and acceptance of new technologies (Hannink et al., 2008). Despite the centrality of news coverage on DCT apps for citizens' opinion formation, research on DCT apps has so far mainly focused on investigating attitudes and opinions toward this technology (e.g., Matt, 2021; Nurgalieva et al., 2023). To the best of our knowledge, only very few studies have investigated yet how the news media portrayed DCT apps during the COVID-19 pandemic. The few existing studies are limited to examining rather formal aspects (Zimmermann et al., 2021) or quite specific aspects of DCT apps such as validity claims (Chigona et al., 2021) or ethical debates. Samuel and Lucivero (2022), for example, find that the discussion around the app strongly focused on privacy issues. Studies on news coverage in Norway are almost entirely missing so far, with the exception of a study by Metzler and Åm (2022) which compares news articles and policy documents in Norway and Austria with a focus on technological governance and the shifting political geographies. Investigating how “Smittestopp” was portrayed in the news helps to close this research gap as well as uncovering challenges in communicating DCT apps and the uncertainties related with them to the population.

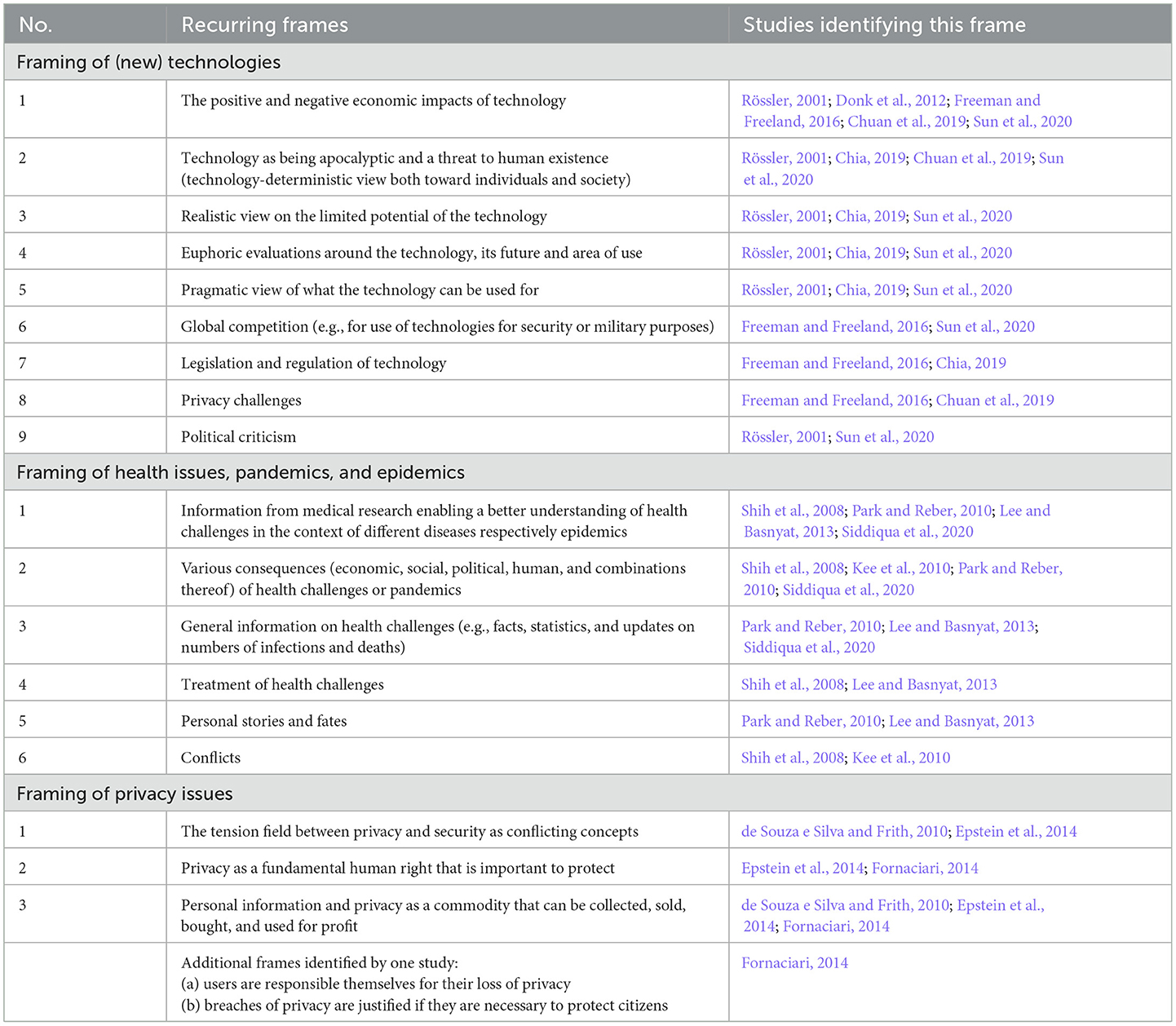

Our study builds on research traditions that deal with the news portrayal of three related phenomena: the framing of (1) (new) technologies (such as “Smittestopp”), (2) health issues, pandemics, and epidemics (such as the COVID-19 pandemic), and (3) privacy issues (since violations of privacy were a main concern in the debate about “Smittestopp”). Theoretically, there are both studies using generic and issue-specific frames. Methodologically, quantitative studies working with predefined frames dominate in these research fields [for an exception see the qualitative framing analysis by Siddiqua et al. (2020)]. This underlines the need for qualitative studies which identify frame elements and frames inductively.

Despite the diversity of studies across research fields, we have identified several recurring frames which have been named differently by different authors but are similar content-wise (Table 1). The communication about scientific uncertainties seems to be most prevalent in the recurring frames on health issues, pandemics, and epidemics, with a particular focus on health challenges and their consequences, which includes uncertainties about diseases and pandemics. Our study, however, focuses on uncertainties about “Smittestopp” as a brand new technology, launched in a situation unprecedented in the 21st century. The question arises whether similar frames also shape the debate about “Smittestopp” or whether case-specific frames developed in it. Therefrom follows our research question: How was the first version of “Smittestopp” framed in press releases by the NIPH and the DPA as well as in coverage by three Norwegian news media, and which role played uncertainties about the technology in the public communication?

3 Methods

We aim at uncovering patterns in the public portrayal of “Smittestopp” within a given theoretical framework (here: framing) which requires a combination of inductive and deductive elements. Qualitative content analysis is a method that meets these requirements well and has several advantages with regard to our research interest compared to other methods. Different from entirely open, explorative approaches to text analysis (e.g., grounded theory), qualitative content analysis structures both coding and analysis by and restricts them to categories (here: frame elements) derived from theory (here: framing) before starting the analysis (Mayring, 2019). Compared to the more intuitive thematic analysis—a related qualitative approach—qualitative content analysis “allows for more precise definitions and gets closer to the actual text” (Mayring, 2019), and opens up for quantitative analyses of the data (Humble and Mozelius, 2022), which we also aim at in our study. Different from quantitative content analysis whose “rule-based systematic principles” (Mayring, 2019) inspired the development of qualitative content analysis, the latter has the advantage that it enables to discover new frame elements on “Smittestopp” during the coding process. We consider this adequate when analyzing communication about a new phenomenon and the uncertainties related to it while yet lacking secure knowledge on what exactly to search for in the texts.

3.1 Selection of materials

For our analysis, we selected materials from public authorities and news media. We investigate press releases of the NIPH and the DPA as potential frame sponsors. These public authorities appeared as protagonists with contrary positions in the public controversy around “Smittestopp” and had agency—the NIPH by developing and launching the app, the DPA by banning it due to privacy concerns. Our rationale for the selection of news outlets is that the news media are the citizens' most important political information source (Maurer and Oschatz, 2016; Moe, 2022), and their potential for impact is likely to be greater the wider their reach is. Therefore, we analyze the most-used representatives of three central media types in Norway: the public broadcaster Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation (NRK), the quality newspaper Aftenposten, and the tabloid Verdens Gang (VG) (Moe, 2022). All three outlets are published nationwide, both online and offline. Given their wide reach in the Norwegian population, it seems plausible that many Norwegians received information about “Smittestopp” from these news outlets. Moreover, as lecacy media, these outlets should normatively feel committed to the task of informing the population comprehensively (Schudson, 2008) about such a pivotal, current topic as “Smittestopp” and about diverse, central arguments in the discourse about it, including uncertainties about the technology.

We identified the relevant materials within these five sources in a multi-step process that also served to inductively define our study period, dependent on when the first press releases respectively news articles on the app had been published. We started with looking for relevant press releases on the websites of both authorities, using the keyword “Smittestopp.” Since our study focuses on the public controversy about the app, we selected only press releases from the categories “News” (NIPH) and “Current news 2020” (DPA) but filtered out other content (e.g., theme pages about the app, Q&A articles, blog posts). The first press release we found had been published on 10th April 2020. To make sure that we had not overlooked press releases published before the app was named “Smittestopp,” we searched both websites again with the keyword “app” and found press releases from 27th March that referred to an “infection tracking app.” Thus, we defined our study period from 27th March to 11th September 2020—the point in time when the focus of the public debate turned to the app's second version.

Afterwards, we identified relevant news articles using the database Atekst Retriever. First, we searched for articles from 27th March to 11th September that contained “Smittestopp” in the title or lead to ensure that the app was the main focus of the identified articles. We excluded short articles up to 100 words that were first latest news and turned into longer articles later. To track news articles published before the app was named “Smittestopp,” we searched again in Atekst Retriever using the keyword “app.” After excluding all articles that did not deal with infection control, five articles remained. One of them, published by NRK, indicated that there had been relevant articles already before the first press release from the NIPH. Therefore, we conducted a third search in Atekst Retriever with the keyword “app” from 12th March (lockdown in Norway) to 27th April and identified another relevant article published by NRK on 24th March. This sets our final study period to 24th March to 11th September 2020. Before the coding process, our sample consisted of 23 press releases (NIPH: 14; DPA: 9) and 58 news articles (Aftenposten: 27; VG: 17; NRK: 14).

3.2 Coding process

Our coding process is inspired by Thomas (2006, p. 242) step-by-step guide for inductive analysis which consists of five steps: (1) reading of the texts (here: press releases/news articles), (2) identifying specific text segments (here: frame elements), (3) selecting text segments to create categories, (4) reducing overlap and redundancy in the categories, and (5) creating a model that includes the most important categories (here: frames). However, following the methodological approach of qualitative content analysis (Mayring, 2019), we combine inductive with deductive elements (here: the categories on the four frame elements in our initial coding scheme) in order to relate our study with framing as our theoretical framework. Therefore, specifically step 2 and 3 were conducted in combination with one another.

One of the authors coded all materials. She started with reading the texts (step 1) as a basis for identifying relevant frame elements. For steps 2 and 3, we developed a coding scheme based on Entman's (1993) four frame elements and oriented toward the operationalization by Matthes and Kohring (2008). The categories we started with were formulated as broad, open questions (see Mayring, 2019). For identifying problem definitions, we asked: What is the text's central topic? What does it define as a problem? Which actors are related with the problem definition? We understand an actor as a person, a company, or an organization expressing themselves, being (in)directly responsible, or raising a central position. More than one problem definition per text could be coded. Our question regarding causal interpretations was: Why is something considered a problem in the text? Concerning moral evaluations, we asked: What risk and benefit evaluations are mentioned related to the problem definition? Who is described as being responsible for risks and benefits related to the problem? Finally, we asked: Which treatment recommendations for the problem are mentioned?

The answers to these questions were noted down in the coding scheme. The coder coded one text at a time, filled in one coding sheet for each problem definition identified, and coded all related frame elements present on the same sheet. This is illustrated by the following example: On March 24, NRK published an article with the headline: “NIPH is making an app to track people in the fight against the Coronavirus” (Skille, 2020a). The article was mainly about the NIPH's development of “Smittestopp” which is why the headline was noted as problem definition. The causal interpretation related with this problem definition was that the app was to collect sensitive data about people which posed privacy challenges. The actors who were held responsible for the risks and benefits were the NIPH and the state-owned company Simula. The risk assessment was that the app was a threat to users' privacy since it is difficult to anonymize large amounts of location data. One benefit evaluation was that the app would automate infection tracking and make it faster and more accurate, which would help to stop the epidemic. Another benefit evaluation was that the app would be within the regulations by taking privacy and data security into account. There were not any treatment recommendations related to the problem definition. Since the article did not contain any alternative problem definitions, only one codesheet was filled in for this article.

We specified that to identify a frame in a text, a problem definition as well as at least two other frame elements had to be coded. Therewith, we aimed to identify typical combinations of frame elements that we interpreted as separate frames. While several articles contained multiple problem definitions, we also found texts lacking a problem definition. For example, a press release by the DPA (24 June) only announced that they received a response from the NIPH about the temporary ban on the processing of personal data. Such texts were excluded from the analysis, which lead to a final sample of 58 texts—eight press releases (NIPH: 5; DPA: 3) and 50 news articles (Aftenposten: 22; VG: 16; NRK: 12).

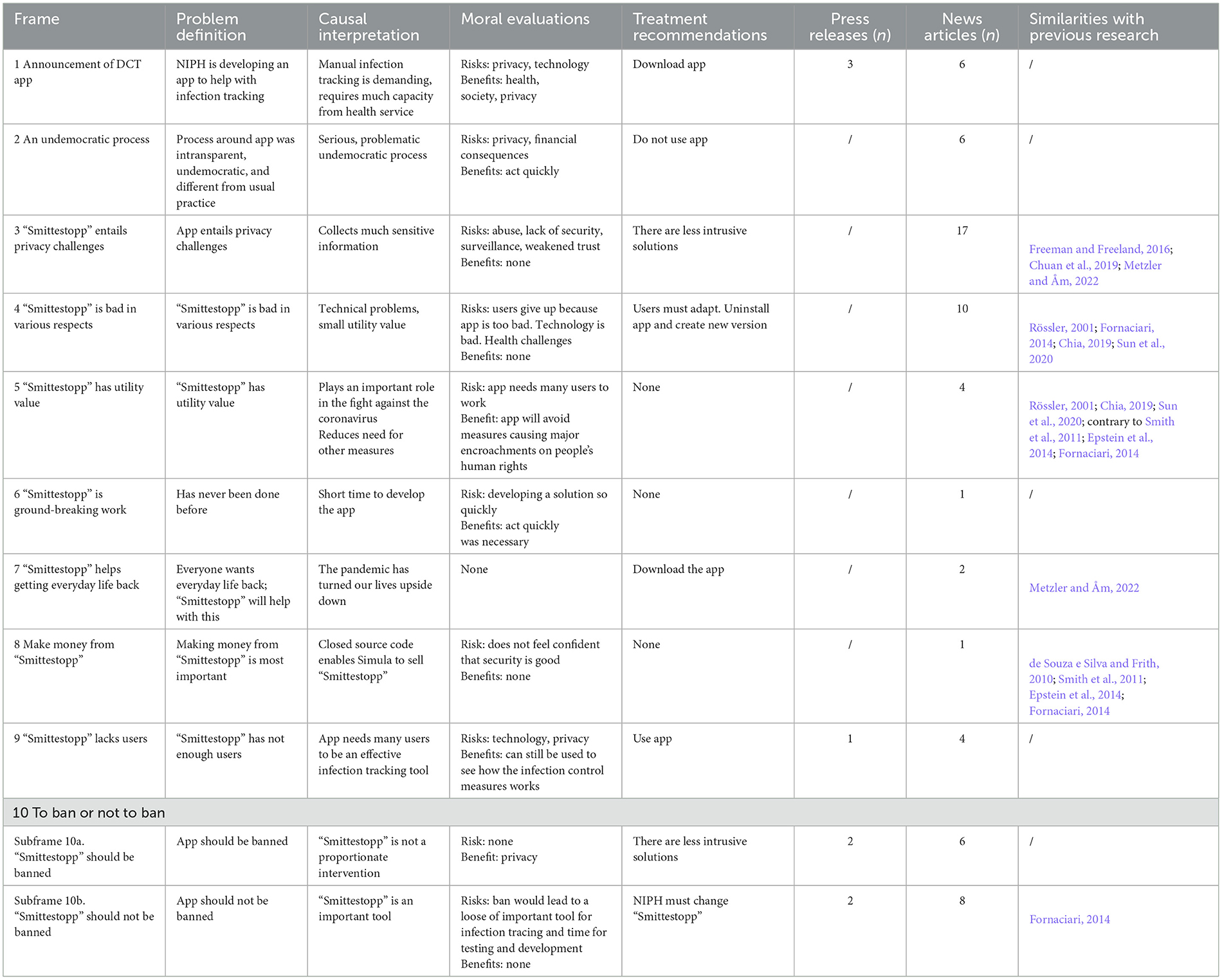

After having identified the frame elements that way, the coder inductively summarized and classified them in order to create more specific categories (Mayring, 2019). She had identified overall 72 problem definitions, combined with diverse other frame elements which appeared relatively unique at first glance. She went through the codings in several rounds and grouped all similar problem definitions into the same overarching categories to reduce overlap and redundancy (step 4). Each overarching frame had to include a unique problem definition not covered by any other frame. While the problem definition is unique to each frame, moral evaluations, causal interpretations, and treatment recommendations could be assigned to several frames at the same time. It is the specific combination of frame elements that makes a frame. Besides, many frames comprised several moral evaluations, causal interpretations, and/or treatment recommendations. We deliberately chose to include all these in the frame rather than just the most frequently used ones, aiming at a more inclusive representation of what the frames consisted of and in order to keep the final number of frames manageable. How often a frame appeared in the materials did not matter for defining it as a frame. This aggregation process resulted in 11 final frames, understood as typical combinations of the frame elements coded, which were named after the problem definition as the frames' most central element (step 5). After having identified the final frames, the coder went through all texts again and adjusted the codings to the final categories to ensure that all texts had been coded consistently (Mayring, 2019).

Taking frame 1 “Announcement of DCT app” as an example, we illustrate the process of identifying the final frames. Nine coded texts included different variants of the same problem definition, for example “App that tracks Corona infection,” “NIPH creates app for infection detection,” and “NIPH creates tracking app to prevent Corona infection.” Since these problem definitions had in common that an app was to be created to easily track the infection, we grouped them into one frame. The problem definitions were related to very similar causal interpretations which could easily be summarized: manual infection detection is demanding but digital infection detection will bring along privacy challenges. There were various moral evaluations related to this problem definition (Table 2; chapter 4.1) which we all kept in line with our general decision described above. The only treatment recommendation coded in this frame was the encouragement to download the app.

While a certain degree of subjectivity is unavoidable in qualitative studies due to the close relationship between researcher and method (Stenbacka, 2001), we wanted to avoid a too high degree of subjectivity in the codings. Thus, the coder coded five randomly selected articles another time, and an external coder coded a selection of five randomly selected articles. A comparison showed that these additional codings were highly similar to the original codings. However, this was not an intercoder reliability test as common in quantitative research (see Stenbacka, 2001) but rather a check for the quality of our qualitative research.

4 Findings

Table 2 gives an overview of the 11 frames we identified. Due to space restrictions, we cannot present detailed analyses of all frames. Thus, we have decided to focus on five frames which both illustrate the variety of the frames, represent strongly contradictory positions and thus reflect the breadth of the discourse, and illustrate interesting patterns of the presence and absence of references to uncertainties about “Smittestopp” as a technology. All quotes from the materials are own translations from Norwegian to English.

4.1 Frame 1: announcement of DCT app

The first frame focuses on the NIPH's plans to create an app for infection tracking. It was found in three press releases (two from the NIPH, one from the DPA) and six news articles at the beginning of the investigation period. The news articles mainly mirror the information from the NIPH when using this frame, which points to that the news media in this early phase of the pandemic as a situation of strong uncertainty orientated toward the authorities. We did not find a match for this frame in previous framing studies which indicates that it is case-specific. The common denominator of texts including this frame is introductory information on what DCT apps are and how they work. When it comes to the causal interpretation, this frame starts from the demands and fragility of manual infection detection, which is only based on people's memory. The frame highlights how laborious and error-prone the previous methods are “with yellow notes, pen and paper in the municipalities and the Public Health Service” (Johansen, 2020). In the digital age in a highly digitized country like Norway, these procedures must seem completely old-fashioned. Framing DCT that way can give the reader the impression that DCT will make them superfluous. From this vantage point, DCT may appear as a significant progress that could make people more open to accept privacy challenges resulting from the large amount of sensitive data collected.

Comprehensive information about a new technology that the authorities want as many people as possible to use should also take a more critical look at the uncertainties related with it and its potential (negative) consequences. However, this perspective is widely missing from this frame. In the moral evaluations, the benefit evaluations outweigh the risk assessments by far. One of the benefits mentioned is that “Smittestopp” will enable faster infection detection, help to reduce infections, save lives, and that the collected data can be used for research on the effectiveness of infection control measures and the spread of the epidemic (Johansen, 2020). Responsibility thereof is assigned to those who enabled the app: the NIPH, Simula, the Directorate of e-health, and the Research Council of Norway. Another benefit for which the government, the NIPH, and Simula are assigned responsibility (and with it honor) is that “Smittestopp” can contribute to the downsizing of other infection control measures and the reopening of society, which must have appeared as an extremely tempting scenario to most people in the midst of the lockdown. In the words of prime minister Erna Solberg: “We can perhaps take some of the strictest measures down if we get to this tracking app that we are now working on” (Larsen, 2020). The fact that the popular prime minister is in favor of using the app should also increase its credibility and importance among the population. Both benefits will, furthermore, contribute to financial benefits since DTC can save the NIPH and the municipalities many resources and “help to reverse the negative development in the Norwegian economy” (Stoltenberg et al., 2020) by reopening society, as phrased by leading representatives of the NIPH, the Norwegian Research Council, the Directorate of e-health, and Simula in in an urgent appeal to the population in the tabloid VG. This newspaper offers a stage for this appeal of highly trusted actors and supports therewith the authorities. Again, both the NIPH and Simula are assigned responsibility and honor. The uncertainty if the technology really will have these beneficial effects is neglected.

The few risk assessments mentioned in this frame focus on privacy, which already hints at—but downplays—the central conflict around “Smittestopp.” It is common to use experts in the field as references in this context. Here, at least, there are allusions to the uncertainties about the technology. For example, a researcher on privacy and health law states in NRK: “It is unclear to me how to anonymize the geolocation data, and whether these data can be anonymized at all in accordance with the strict requirements for anonymization that follow from the privacy rules” (Skille, 2020b). Responsibility for these privacy issues is assigned to the NIPH, Simula and the authorities. However, in Aftenposten, a representative of the NIPH contradicts the privacy concerns and thus downplays the uncertainties about the technology. She says that the app's design safeguards users' privacy, stays within the regulations, and has clear guidelines for how to collect, store, and delete the data. She mentions that those responsible—the NIPH, Simula, and the DPA—will ensure to carry out the collection of sensitive personal data with restraint (Larsen, 2020).

Moreover, the NIPH tries to refute horror scenarios from other countries which had been discussed in the news media and could prevent people from using “Smittestopp”: “Some of the tracking functionality in solutions used abroad is irrelevant in Norway, such as showing where infected people are on a map” (Larsen, 2020). Another risk assessment is that the app needs many users to be effective, implicitly addressing the uncertainty how the general public will respond to the app. This assigns the responsibility for this risk implicitly to every single citizen who will not use the app. In the same vein, the frame contains only one treatment recommendation: people are encouraged to download the app. An example thereof is, again, the commentary by the representatives of the NIPH, the Norwegian Research Council, the Directorate of e-health, and Simula: “We are now in a completely extraordinary situation, and each of us can, as part of the national charity, help to reduce infection faster by choosing to use the app” (Stoltenberg et al., 2020). However, since the app was not available yet at the time when most of these texts were published, this seems rather a matter of preparing people for and getting them to commit to the measure.

To sum up, this frame portrays the app predominantly as safe and absolutely necessary, therewith putting it in a positive light. Probably the NIPH intended to create trust in the app by downplaying scientific uncertainties and privacy concerns. However, the NIPH was obviously well-aware from the beginning that there was a conflict between health and privacy, which was to become central only a short time later, and it tried to allay the concerns—if not in its press releases then in interviews with and commentaries in the news media. Strategically, they made their prioritization clear from the beginning: in their weighing of two goods, both of which are central to the Norwegian society, health weighs more heavily than privacy in this specific case.

4.2 Frame 2: an undemocratic process

The problem defined in frame 2 takes a completely different, predominantly negative perspective on “Smittestopp.” It focuses on the decision process around the app which is described as intransparent, not in line with usual practice, and thus undemocratic. Also this frame seems to be specific to “Smittestopp,” at least it is not similar to any of the frames we identified in previous studies. A central problem discussed in this frame is that the app was not put out to tender which violates the Norwegian competition rules. VG quotes a lawyer stating: “The NIPH can not just award a contract of 45 million kroner to whomever they want without running a competition” (NTB, 2020). In Aftenposten, a causal interpretation is given for why this is considered problematic: the authorities did not follow common democratic practices, laws and rules, and a “month ago, such digital mass tracking would have been unthinkable in Norway, and possibly illegal” (Johansen, 2020). These concerns must be seen against the background of Norway being one of the most democratic countries in the world in which the right to privacy and other human rights enjoy a high status. They reflect, moreover, a more common concern in the discussion about the pandemic which was raised in several countries: that the health protection measures massively restricted and might permanently have weakened human rights. The fight for the interpretative authority of the app had thus flared up, and the media let the public know.

The moral evaluations following therefrom clearly relate to democratic standards such as the diversity of the public discourse and the transparency of the democratic process (Schudson, 2008). An important line of argument which relates implicitly to uncertainties about the technology is that the lack of transparency could make the app unnecessarily intrusive and surveillant because critical voices were not heard. This shows the close connection of this frame with frame 3 which focuses on privacy issues. The lack of a bidding process could lead to negative financial consequences since using the state-owned company Simula for reasons of time pressure was prioritized over stimulating the market. Consequentially, the only benefit mentioned is that the NIPH could act quickly in an exceptional situation (responsible: NIPH, Simula), which, however, plays only a subordinate role in this frame. The consequences of undemocratic processes are thus portrayed as risks almost without benefits, which let appear using the app extremely problematic, especially in a country where democratic values are highly valued. The responsibility for these risks is assigned to the NIPH who made the decisions around the app and the government who approved the underlying regulations. The only treatment recommendation is not to use the app. A software developer writes in a commentary in Aftenposten that a “national contribution to critical thinking [is needed]. I want you to know that if you follow the advice on social distancing and to keep a small log of who you associate with, then you can delete the Smittestopp app with a clear conscience” (Haukås, 2020).

This frame was found in six news articles but not in any press releases. The DPA does not appear to have used these arguments, and the NIPH does not seem to have reacted to them, at least not in their press releases. It is positive that the media brought up this frame, fulfilling their function of criticism and control. However, it seems problematic that the solution (the treatment recommendation) of a structural problem which was caused by political decisions is being passed on to the individual citizens who at the same time are being exposed to massive appeals from the NIPH and the government to use the app. This can throw citizens into conflicts. For a better contextualization, the media should also draw attention to the need for action at the political level. Uncertainties about the app play a marginal role at most in this frame.

4.3 Frame 3: “Smittestopp” entails privacy challenges

While other frames discuss privacy issues as a risk, frame 3 makes the privacy challenges entailed by “Smittestopp” and the related uncertainties of the technology and its consequences the focus of its problem definition. This frame is similar to the findings of other studies (Freeman and Freeland, 2016; Chuan et al., 2019; Metzler and Åm, 2022). It was addressed in the media almost from the very beginning. The causal interpretation is that “Smittestopp” collects a lot of sensitive information about the users and stores them centrally. This differs from the solution in many other European countries whose DCT apps store data locally on individuals' mobile phones. A common statement used by several media in the first days after the ban (e.g., VG, Breivik et al., 2020; Aftenposten, Lund, 2020) originates from Amnesty International which compared “Smittestopp” to DCT apps in autocratic states such as Bahrain and Kuwait and called it one of “the most invasive in the world.” This example shows that it is not only the NIPH and the DPA who fought for interpretational sovereignty.

Accordingly, the moral evaluations in this frame purely focus on the risks entailed with the potential misuse of the data collected, a lack of security (which can cause data going astray), and surveillance. Uncertainties about the technology, how it could be misused and by whom, lie thus at the core of this frame. A software developer reports in VG that he found that the app could be used to track users and warned against abuse by commercial actors “who will be able to find out if the person who came into the shop has installed the app” (Høydal and Hansen, 2020). A researcher from the field, again in VG, assigns the responsibility thereof to the NIPH and Simula who produced the app, the government who allowed this type of data collection, and the DPA for having “done a bad job” (Hansen and Simensen, 2020). Even the DPA is accused here, which was actually supposed to protect data security—and also fulfilled this task in the further process. Interestingly, another form of uncertainty around the technology is by far less explicitly discussed—the question how probable it is that the dangers addressed will become true. This illustrates the one-sidedness of this frame.

Even the app's ban on June 15 did not end the struggle for sovereignity. It continued for example in an article in VG on June 18 when the NIPH had already voluntarily stopped its data collection and the app was no longer available for download. In this article, Bent Høie (then minister of health) asked the population to deactivate but keep the app. The goal was to be able to reactivate it as soon as the privacy issues had been solved, especially since the authorities already had first ideas how to fix these. In the same article, however, an oppositional health politician is quoted as saying that the “government's and NIPH's unprincipled attitude to privacy during the development of the infection app has undermined the population's trust in the entire app project” (Breivik et al., 2020), for which the NIPH, Simula and Høie were held responsible.

As treatment recommendations, the frame suggests to find better solutions for collecting data that take care of privacy, to follow the GDPR, and thus to reduce uncertainties about the technology. A cryptologist recommends the Google Apple Exposure Notification and guesses a new version of the app solving some of these challenges would be available soon (Skille and Gundersen, 2020)—which actually happened in the second version. Some articles keep on warning against using the app, illustrated by the examples of a politician refusing to download it and Amnesty International's comparison described above. With 17 articles, this frame was the most prevalent one in the news while it was not found in any press release. Not only the frequency but also the unambigousness with which the app was condemned makes this frame a very dominant one. One can only speculate as to what the public discussion really contributed to the later failure of “Smittestopp.” However, this massive criticism, centering around uncertainties about negative consequences, raises doubts as to whether it even had a realistic chance after the DPA had intervened.

4.4 Frame 4: “Smittestopp” is bad in various respects

The next two frames are mutually related; frame 5 arose as a direct response to frame 4. Both present different perspectives on the app's pitfalls and benefits. Frame 4 developed almost immediately after the app's launch when people discovered various technical errors and flaws, probably resulting from the short development time. The frame is, thus, not about uncertainties but rather about certainties after the first user experiences with the new technology. The frame reflects the app's shortcomings and portrays it consequentially as a bad tool for infection tracking, which is similar to two frames found in other studies: “realistic view” (Rössler, 2001; Chia, 2019; Sun et al., 2020) and “users' responsibility” (Fornaciari, 2014). It is the second most frequent frame in the news media (10 news articles) but not present in any press releases. The problem definition is related with two causal interpretations why the app is considered bad: First due to technical problems such as draining phone batteries, lack of universal design, imprecise technological solutions for tracking infection, and too many steps to put the app into use (Aalen, 2020). Second since its low utility value raised doubts about “what the goal of the app really is” (Breivik et al., 2020), as phrased by an oppositional health politician in VG, bringing new uncertainties about the technology into play. The bad user experiences presumably decreased both people's willingness to use the app and their trust in it.

Concerning moral evaluations, this frame refers to three risks but no benefits and can thus, as frame 3, be considered purely negative toward the app. First, many users will not download the app, stop using or uninstall it (responsible: NIPH, Simula). Second, the technology is too bad to replace manual infection tracking (responsible: NIPH, Simula, health minister). Third, technological flaws can cause challenges for healthcare if false positives cause unnecessary testing (responsible: NIPH, health minister, prime minister). Unlike the more abstract privacy issues that are difficult for the individual user to observe (and many people do not care about privacy issues when using services such as Google or Facebook), this frame addressed problems that many users experienced themselves. It seems plausible that negative user experiences and the resulting media coverage further contributed to the low use of the app, maybe even more than the privacy issues.

Frame 4 comprises three treatment recommendations. They originate from different actors who assign responsibility to others, which clearly brings their strategic interests to the forefront. (1) The health authorities assigned responsibility for solving the problem to the users who should adapt to the shortcomings. An article on NRK quotes a leading representative of the Norwegian Directorate for Health and Social Affairs who recommends people to ask others for help, to try again, or to “charge your mobile phone an extra time in the course of a day, [which is a small price to pay] when it contributes so much to stop the spread of infection. Rather bring a charger to work, or wherever you are, so that you always have enough power” (Krüger et al., 2020). For the authorities, individualizing responsibility was certainly the easiest solution in that situation. (2) This is countered by a commentary in Aftenposten who also asks the users to solve the problem, but in the opposite way: “What is certain is that you can disable the app right away—with a clear conscience” (Lund, 2020). This is an example of the news media clearly criticizing the authorities. (3) Finally, aiming at a societal rather than an individual solution, other actors called the NIPH to take action and develop a new version of “Smittestopp” which avoids the problems. One of them is the aforementioned oppositional health politican (Breivik et al., 2020) for whom this was a good opportunity to criticize the government via the NIPH.

4.5 Frame 5: “Smittestopp” has utility value

In direct response to frame 4, frame 5 puts the app into a more positive light by highlighting its utility value. It is similar to the frame “pragmatic” found by Rössler (2001), Chia (2019), and Sun et al. (2020) and contrary to “privacy as a right” found by Smith et al. (2011), Epstein et al. (2014), and Fornaciari (2014). As frame 4, it was only found in news articles (four in number) but not any press releases. Even though this frame supports the health authorities' goals, it is another indication of the news media bringing original arguments and voices into the debate rather than just echoing the authorities. In Aftenposten, two researchers—one into artificial intelligence, the other one into cancer research—pay tribute to the work of Simula and NIPH: “Collecting and sharing data for our common health is important, in immediate crises such as COVID-19 and against societal challenges such as cancer” (Goodwin and Widerberg, 2020). Such statements sound as if there was no uncertainty that the Norwegian society definitely would benefit from the technology.

The dominant causal interpretation (included in three out of four articles) is that “Smittestopp” has utility value since it can play an important role in the fight against COVID-19 and reduce the need for other measures that would involve greater human rights violations. The only article which provides another causal interpretation originates from two experts into human rights who write in Aftenposten that they think “Smittestopp” stays well within human rights because its use is voluntary (Mestad and Skre, 2020). Although frame 5 developed in direct reaction to frame 4, the causal interpretation is not primarily about the problems with the app's utility value. Rather, it focuses on the privacy issues and related possible violations of human rights addressed in frame 3 which, however, are considered justified when weighted against the benefits.

When it comes to moral evaluations, this frame entails one risk assessment and one benefit evaluation. The risk assessment originates from Simula researchers who were involved in the app's development and do presumably not only believe in the quality of their own work but also have a strategic interest in the continued use of the app. In a commentary, they mention as a main problem that as many people as possible must use the app in order for it to be effective, assigning responsibility to the users (Lysne et al., 2020). However, also the benefit evaluation relates to the appeal to use the app. Two human rights experts who call “Smittestopp” a middle ground between plague and cholera write: “Quarantine, cabin bans, travel bans, and isolation provisions are encroachments on the right to privacy, freedom of movement, and property rights. (...) It is more difficult to protect against violence and abuse when so much time is spent behind the four walls of homes” (Mestad and Skre, 2020). The responsibility for this benefit is assigned to the government who decided on the development of the app. This frame does not contain any explicit treatment recommendations. However, particularly the risk assessment implicitly suggests that the population should use the app, which again assigns a significant (share of) responsibility to the individual citizens.

In combination, frames 4 and 5 indicate that the news media let different voices have their say in the public debate about “Smittestopp” and provided a forum for the controversial discussion, albeit with a predominance of critical voices, at least when taking into account the frequencies of both frames. A discussion about uncertainties related to the technology, however, is widely absent in both frames.

4.6 The framing of “Smittestopp” by public authorities and news media

After having defined 11 frames around “Smittestopp” in the public discussion, we will now compare how far these were used by authorities (NIPH, DPA) and news media (Aftenposten, NRK, VG). Since we coded the entire data material using the same coding scheme, our qualitative data allow for some descriptive statistics (Mayring, 2019). Table 3 shows who used which frames how often. Since the numbers are quite small, however, the findings below must be interpreted with care.

Concerning the public authorities, both the NIPH and the DPA used only a limited spectrum of frames in their press releases. Unsurprisingly, they focused on different frames—the NIPH advocating for, the DPA against the app. The press releases by the NIPH did not contain any negative views on the apps besides one mention of “‘Smittestopp' lacks users” which was presumambly used strategically to encourage more people to use the app. This can be interpreted as an almost complete ignorance of any uncertainties about the technology which was portrayed as completely safe and recommendable by the NIPH. The DPA noticeably did not utilize the frame “privacy challenges” in its press releases but rather emphasized information about measures, bans, and the process forward. Maybe they did not want to publicly comment on the privacy challenges and the uncertainties about the technology while still reviewing the app or they used other channels (e.g., interviews with news media) for communicating their concerns. First after completing their review, they used the sub-frame “‘Smittestopp' should be banned.”

Even though both authorities portrayed “Smittestopp” in a one-sided way, this pattern is not very strong. Most press releases did not contain any of the 11 frames. Many press releases provided only basic facts, e.g., on processes such as testing (NIPH) or controlling (DPA) the app. Neither the NIPH nor the DPA were thus strongly concerned with frame building in their press releases, and none of them took the chance to discuss the uncertainties entailed by “Smittestopp.”

The news outlets' strong focus on the “privacy challenges” frame—which is contained in every fourth news article—is striking. The outlets provided a significantly larger diversity of frames than the press releases, indicating that the media fulfilled their task to provide diverse information (Schudson, 2008). However, the news outlets differed in this respect: the quality paper Aftenposten used all 11 frames while the tabloid VG neglected two and the public service broadcaster NRK even five. Still, all three strongly addressed the privacy challenges. In Aftenposten and NRK, frames with a focus on the risks of the app overweigh those with a focus on the benefits. Aftenposten's most used frames are “privacy challences,” “undemocratic process” and “‘Smittestopp' is bad.” NRK's top 3 are “privacy challenges,” “‘Smittestopp' is bad” and “‘Smittestopp' should be banned.” Obviously, Aftenposten and NRK considered it pivotal to inform the public about the app's risks and uncertainties but at the expense of addressing its benefits, which might have contributed to the populations' skepticism toward using the app.

VG focused more strongly on the benefits with “‘Smittestopp' should not be banned” and “utility value” ranking second respectively third after “privacy challenges.” Somewhat surprisingly, the coverage of the tabloid was thus most balanced. However, it must be noted that the reporting style of VG is rather moderate compared to many other (particularly Anglo-American) tabloids.

5 Discussion

5.1 Understanding of findings

The introduction of the newly developed DCT app “Smittestopp” in Norway was accompanied by strong scientific uncertainties about the technology, its benefits and risks. Our qualitative content analysis investigated how these uncertainties were communicated in public. It shows that the public debate about the app can be broken down to the overarching conflict between health benefits (represented mainly by the NIPH but also the government) vs. privacy and data security (represented by the DPA) (see also Metzler and Åm, 2022). We investigated how the first version of the app was framed by two public authorities and three leading Norwegian news outlets from the first announcements of the app to its replacement by the second version (March–September 2020). The perspectives represented in the public debate had the potential to influence the citizens' opinion toward and willingness to use the app which makes our framing analysis highly relevant. How different actors dealt with uncertainties about the app might have played a central role in this process.

Altogether, we identified 11 frames. Uncertainties about the new technology were mainly present in frames taking a negative view on the app but rather absent in frames taking a more positive view. It seems like uncertainties fit better into skeptical narratives. Six frames are case-specific for “Smittestopp”: “announcement of DCT app,” “undemocratic process,” “groundbreaking work,” “get everyday life back” [also identified as central argument in the case study on “Smittestopp” by Metzler and Åm (2022)], “lack of users,” and “the app should be banned.” Their case-relatedness may explain their unrelatedness with frames identified in framing studies from related fields. However, the five more general frames we identified are quite similar to what previous framing studies on new technologies and epidemics found (see Table 2), which supports the credibility of our results: “privacy challenges,” “make money from ‘Smittestopp',” “‘Smittestopp' is bad,” “utility value,” and “‘Smittestopp' should not be banned.” Therefrom follows an implication for theory building in framing research: generic frames (Semetko and Valkenburg, 2000) are often criticized for being too unspecific while thematic frames (de Vreese, 2005) are accused of being too topic-specific and often not going beyond the individual case they have been developed for. However, the clear similarities we found between the thematic frames we identified and the thematic frames identified in various other studies even across three different research fields—framing of (new) technologies, of health issues, pandemics, and epidemics, and of privacy issues—indicate that there might be something in between, more overarching than thematic frames but more specific than generic frames. It would be worth looking into this more closely.

The broad diversity of 11 frames that we found in a relatively small selection of press releases and news articles indicates a diverse public debate in which different voices were heard. It is, however, surprising that both the NIPH and the DPA sent out only few press releases on “Smittestopp” which hardly referred to any of the frames we identified. Even though both institutions had strategic interests in framing the app in certain ways (driven by the uncertainties about how the general public would respond to the app), they do not seem to have strongly tried to use their press releases for frame building. However, this cannot necessarily be interpreted as a lack of frame building efforts. Among other communication channels they could and did use were press conferences, guest contributions and interviews in news media, and social media content. For example, our materials show that diverse representatives of the NIPH and other health authorities were often quoted in the media. Nevertheless, the failure of “Smittestopp” seems to have been also a communication problem. The focus of the discussion obviously turned quickly to the negative sides, which may have affected its acceptance among the population—even though it was in case of both potential negative and positive consequences uncertain how likely these were to actually occur. This is all the more important as the news media, functioning as a forum for public discourse as they should, also gave other frame sponsors the opportunity to raise voice.

Compared to the press releases, the news articles provided a much richer spectrum of frames, in line with Lee and Basnyat (2013) who showed that journalists do not use the news frames from the press releases to public health institutions slavishly. It was thus not at first instance the NIPH and the DPA who determined the news framing except from the very first phase when the app was announced. Obviously, the news media took their social responsibility seriously and informed the public diversely and critically (Schudson, 2008), even in an extraordinary situation such as a pandemic. They critically discussed uncertainties related to the app, however with a focus on negative aspects. They rather neglected that uncertainties are uncertainties, and it is unclear if the concerns would prove right. However, the app could also have had a positive outcome, and the concerns could have dissolved into nothingness.

Compared to the quality paper Aftenposten and the tabloid VG, the diversity of frames was lower in NRK, despite its social responsibility as a public broadcaster to present a broad range of perspectives. However, it must be taken into account that NRK published least articles on the app, so there was less room for different frames than in the other outlets. Finally, even though the news media clearly focused on challenges of the app, they did not recommend banning it. Striking is the relatively strong focus on privacy challenges which was particularly pronounced in VG. We cannot analyze the effects of the news coverage. However, “Smittestopp” was a brand new technology that people lacked experience with, which brought along uncertainties. The assumption is thus not far that critical news coverage might have contributed to so few people wanting to use the app.

5.2 Implications of findings for practice and policy

The COVID-19 pandemic is probably not the last pandemic we will experience, and hopefully DCT apps can be used as a more effective measure in future cases. All actors involved in the processes around “Smittestopp” should carefully analyze its failure as well as their own decisions and communication strategies, in order to learn therefrom and achieve a better outcome next time.

Our findings can help communication practitioners to improve communication strategies and general processes when introducing DCT apps and other new technologies that affect privacy issues, particularly in the healthcare sector, and bring along uncertainties. Avoiding a proactive discussion on risks of and uncertainties about “Smittestopp” might have contributed to its downfall. It is understandable that the NIPH wanted to provide the app as quick as possible in a dramatic, unforeseeable hazard situation. However, the example of “Smittestopp” shows in retrospect that it might have been better to take a little more time, to carefully weigh up various technical options and risks before launching the app, and to discuss also central uncertainties about the app more critically, signalizing that concerns were taken serious by the authorities. Such an open communication might increase trust in technological innovations such as DCT apps. The quick end of the first version of “Smittestopp” may have undermined public trust in the second version, which ultimately did not become an effective part of the pandemic response either because way too few people used it.

An implication of our findings for journalism practice is that they remind journalists how important it is to be aware of the shaping power of their coverage, specifically for the public perception of new technologies and the uncertainties about them. It is a pivotal part of their professional standards to present different perspectives on these technologies and discuss them critically, without leaning too hard to one side—at least as long as there are no reliable findings that clearly speak for that.

5.3 Study limitations

Naturally, this study has some limitations. As a case study of a limited number of sources in Norway in a certain situation, its findings cannot necessarily be transferred to other contexts. However, the similarities of the 11 frames we found with the findings of other studies (Table 2) indicate a certain degree of transferability to other contexts, particularly when it comes to the more overarching frames. Another limitation is that our study only analyses the communication by two public authorities and three of the most important news media in Norway. Even though these taken together contained a broad variety of frames, it is conceivable that we did not identify the full range of perspectives on “Smittestopp” in Norway. For example, legacy media tend to focus on political actors and authorities and neglect the perspectives of ordinary citizens (Magin et al., 2023).

5.4 Suggestions for future research

From these limitations follow several suggestions for future research. First, our study is a valuable starting point for comparative studies on the framing of DCT apps. For example, a comparison of the framing of the first and the second version of “Smittestopp” would allow for examining how far also the more case-specific frames are transferrable to other contexts. Qualitative content analyses that compare the discussions in Norway with those in other countries which introduced DCT apps could uncover the existence of further, maybe culture-dependent frames that were not present in the Norwegian discussion. Such comparisons can explore the transferability of our findings and are particularly important: even though we documented our procedures accurately, aiming at quality and transparency of our research, our way of identifying frames qualitatively necessarily entailed some subjectivities both in the coding process and the interpretation of the data, as typical in qualitative research (Stenbacka, 2001). Such comparisons would also help to understand how far different legal frameworks and cultural norms (e.g., concerning health and privacy) shape public debates and contribute to the success or failure of different DCT apps.

Second, comparing our findings with frames present in user comments on social media might help figure out if the legacy media overlooked certain frames. Even though social media comments are not representative (Magin, 2022) for how the Norwegian population considered the app, they might broaden the spectrum of frames on it.

Third, in order to comprehensively understand (strategic) communication processes during crises, future research into crisis communication should collect data from different sources and of various kinds (e.g., news coverage, press releases from diverse institutions/actors, interviews with central actors, surveys, social media data) and analyze them jointly.

Fourth, a methodological implication of our study for the discipline is that it suggests how insightful and beneficial a systematic combination of qualitative and quantitative content analysis can be. Both can mutually complement each other with their strengths and compensate for their weaknesses. In our case, we systematically identified a broad (potentially even the full range) of frame elements and frames around the DCT app “Smittestopp.” Our findings could now, for example, feed into the codebook of for a quantitative content analysis on DCT apps in different countries. Such a quantitative study could reveal how widespread the frames we identified were in the news about “Smittestopp” and other DCT apps, in Norway and beyond, checking for the transferrability of our findings. Furthermore, our study can also inform research on communication on new technologies, health issues, and privacy more generally. Thus, we make a general appeal to the discipline to choose more mixed methods approaches.

6 Conclusions

Altogether, our study provides evidence of how the news media fulfilled their role in a situation of scientific uncertaintly when experts were at odds and people lacked personal experience with a new technology. Citizens had to strongly rely on the media to make up their minds on “Smittestopp.” By means of analyzing content, it is not possible to decide conclusively why so many Norwegians decided not to use the app. However, in view of our findings, it seems reasonable to assume that the people's uncertainties and privacy concerns were too large and the one-sided communication of the NIPH further fuelled distrust in the app. By providing diverse perspectives on the app, the news media we investigated provided the citizens with good opportunities for well-informed decision-making. If the negative sides of the app had been brought to the public only later after great damage would have already happened, this might have led to a loss of trust in the authorities and the news media. Thus, even though the first version of “Smittestopp” was a failure for the NIPH, it was a good example of how well-functioning democracies work, to the best for people—even in situations when different parties disagree on what the best for people is.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

A-MK developed the conception and design of this study within the framework of her master thesis and wrote the first full draft of the article. MM supervised the conceptualization and conduct of the study, fundamentally revised the entire draft, and wrote additional sections of the manuscript. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

Acknowledgments

The study presented in this article is based on the master thesis of the first author which is published here: Karlberg, A.-M. (2021). Nybrottsarbeid, personvernutfordringer og forbud: En kvalitativ casestudie av framing av Smittestopp-appen. Master thesis. Norwegian University of Science and Technology.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Aalen, I. (2020). Korona kan ikke bekjempes gjennom ukritisk teknologioptimisme. Aftenposten. Available online at: www.aftenposten.no/meninger/debatt/i/K3mxry/korona-kan-ikke-bekjempes-gjennom-ukritisk-teknologioptimisme-ida-aadebatt/i/K3mxry/korona-kan-ikke-bekjempes-gjennom-ukritisk-teknologioptimisme-ida-aa (accessed November 20, 2023).

Barrat, A., Cattuto, C., Kivelä, M., Lehmann, S., and Saramäki, J. (2020). Effect of manual and digital contact tracing on COVID-19 outbreaks: a study on empirical contact data. medRxiv. doi: 10.1101/2020.07.24.20159947

Breivik, E. M., Bratås, B., and Solheim, P. (2020). Høie ber nordmenn beholde Smittestopp-appen. VG. Available online at: https://www.vg.no/nyheter/i/0n52G6/hoeie-ber-nordmenn-beholde-smittestopp-appen (accessed November 20, 2023).

Chia, S. C. (2019). Crowd-sourcing justice: tracking a decade's news coverage of cyber vigilantism throughout the Greater China region. Inf. Commun. Soc. 22, 2045–2062. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2018.1476573

Chigona, W., Mavela, P., Moyanga, R., Mulaji, S., Mutetwa, S., Ndoro, H., et al. (2021). “Critical discourse analysis on media coverage of COVID-19. Contract tracing applications: case of South Africa,” in CandT'21: Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Communities and Technologies – Wicked Problems in the Age of Tech June 2021, 15–24 (New York, NY: ACM). doi: 10.1145/3461564.3461580

Chuan, C.-H., Tsai, W.-H. S., and Cho, S. Y. (2019). “Framing artificial intelligence in American newspapers,” in Proceedings of the 2019 AAAI/ACM Conference on AI, Ethics, and Society, Honolulu, USA (New York, NY: ACM). doi: 10.1145/3306618.3314285

Datatilsynet (2020). Personvernundersøkelsen 2019/2020. Om Befolkningens Holdninger til Personvern og Kjennskap til det nye Personvernregelverket. Oslo. Available online at: https://www.datatilsynet.no/regelverk-og-verktoy/rapporter-og-utredninger/personvernundersokelser/personvernundersokelsen-20192020/ (accessed November 20, 2023).

de Souza e Silva, A., and Frith, J. (2010). Locational privacy in public spaces: media discourses on location-aware mobile technologies. Commun. Cult. Crit. 3, 503–525. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-9137.2010.01083.x

de Vreese, C. H. (2005). News framing: theory and typology. Inf. Des. J. 13, 51–62. doi: 10.1075/idjdd.13.1.06vre

Donk, A., Metag, J., Kohring, M., and Marcinkowski, F. (2012). Framing emerging technologies: risk perceptions of nanotechnology in the German press. Sci. Commun. 34, 5–29. doi: 10.1177/1075547011417892

DPA (2020). Midlertidig stans av Appen Smittestopp. Available online at: www.datatilsynet.no/aktuelt/aktuelle-nyheter-2020/midlertidig-stans-av-appen-smittestopp/ (accessed November 20, 2023).

Entman, R. M. (1993). Framing: Toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. J. Commun. 43, 51–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.1993.tb01304.x

Epstein, D., Roth, M. C., and Baumer, E. P. (2014). It's the definition, stupid! Framing of online privacy in the internet governance forum debates. J. Inf. Policy. 4, 144–172. doi: 10.5325/jinfopoli.4.2014.0144

Fornaciari, F. (2014). “Mapping the territories of privacy: textual analysis of privacy frames in American mainstream news,” in 2014 47th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (Waikoloa, HI: IEEE). doi: 10.1109/HICSS.2014.230

Freeman, P. K., and Freeland, R. S. (2016). Media framing the reception of unmanned aerial vehicles in the United States of America. Technol. Soc. 44, 23–29. doi: 10.1016/j.techsoc.2015.11.006

Goodwin, M., and Widerberg, K. (2020). Hva er viktigst, hytta eller helsen? Aftenposten. Available online at: https://www.aftenposten.no/meninger/debatt/i/wPwOzn/kort-sagt-~torsdag-25-juni (accessed November 20, 2023).

Hannink, R., Kuhr, R., and Morris, T. (2008). “Public acceptance of HTGR technology,” in Fourth International Topical Meeting on High Temperature Reactor Technology. September 28–October 1, 2008 (Washington, DC). doi: 10.1115/HTR2008-58218

Hansen, J. S., and Simensen, H. M. (2020). Lektor sendte e-post til høyskoleelever: Omtalte Smittestopp-appen som ≪farligere≫ enn coronaviruset. VG. Available online at: www.vg.no/nyheter/innenriks/i/GGLEw9/lektor-sendte-e-post-til-hoeyskoleelever-omtalte-smittestopp-appen-som-farligere-enn-coronaviruset (accessed November 20, 2023).

Haukås, N. N. (2020). Smittestopp-appen kan bli god butikk. Aftenposten. Available online at: https://www.aftenposten.no/meninger/debatt/i/y3dWpe/smittestopp-appen-kan-~bli-god-butikk-nils-norman-haukaas (accessed November 20, 2023).

Høydal, H. F., and Hansen, J. S. (2020). Har funnet sikkerhetsrisiko i Smittestopp- appen – kan brukes til å spore andre. VG. Available online at: www.vg.no/nyheter/innenriks/i/y3dwae/har-funnet-sikkerhetsrisiko-i-smittestopp-appen-kan-brukes-til-aa-spore-andre (accessed November 20, 2023).

Humble, N., and Mozelius, P. (2022). “Content analysis or thematic analysis: similarities, differences and applications in qualitative research,” in Proceedings of the 21st European Conference on Research Methodology for Business and Management Studies ECRM 2022: A Conference Hosted By University of Aveiro Portugal 2–3 June 2022, ed M. Au-Yong-Oliveira (Academic Conferences and Publishing International Limited: Reading), 76–81.

Johansen, P. A. (2020). Slik skal mobilovervåking stoppe epidemien. Ny app sporer alle du møter en måned tilbake i tid. Aftenposten. Available online at: https://www.aftenposten.no/norge/i/70A974/slik-skal-mobilovervaaking-stoppe-epidemien-ny-app-sporer-alle-du-moete (accessed November 20, 2023).

Kee, C. P., Ibrahim, F., and Mustaffa, N. (2010). Framing a pandemic: analysis of Malaysian mainstream newspapers in the H1N1 coverage. J. Media Inf. Warf. 3, 105–122. Available online at: https://ir.uitm.edu.my/id/eprint/10948 (accessed November 20, 2023).

Kleven, Ø. (2016). Nordmenn på tillitstoppen i Europa. SSB, Samfunnsspeilet, 2016, 13–18. Available online at: https://statbank.ssb.no/kultur-og-fritid/artikler-og-publikasjoner/_attachment/269579?_ts=1555305a1f0 (accessed November 20, 2023).

Krüger, L., Wernersen, C., and Vigsnæs, M. K. (2020). Nesten en million har lastet ned smitteapp. NRK. Available online at: www.nrk.no/norge/nesten-en-million-har-lastet-ned-smitteapp-1.14985000 (accessed November 20, 2023).

Lapolla, P., and Lee, R. (2020). Privacy versus safety in contact-tracing apps for coronavirus disease 2019. Digit. Health 6. doi: 10.1177/2055207620941673

Larsen, M. H. (2020). FHIs korona-app kommer like over påske. Aftenposten. Available online at: https://www.aftenposten.no/norge/i/Vb8evr/fhis-korona-app-kommer-like-over-~paaske (accessed November 20, 2023).

Lee, S. T., and Basnyat, I. (2013). From press release to news: mapping the framing of the 2009 H1N1 A influenza pandemic. Health Commun. 28, 119–132. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2012.658550

Lund, J. (2020). ≪Smittestopp er et viktig verktøy≫, sa Høie. Sannheten er at det er verdiløst. Aftenposten. Available online at: http://www.aftenposten.no/meninger/kommentar/i/8mny5r/smittestopp-er-et-viktig-verktoey-sa-hoeie-sannheten-er-at-det-er-ve (accessed November 20, 2023).

Lysne, O., Tveito, A., and Lekve, K. (2020). Simula: – Smittesttopp virker. VG. Available online at: https://www.vg.no/nyheter/meninger/i/b5xzll/simula-smittestopp-virker (accessed November 20, 2023).

Magin, M. (2022). “(Non-)representativeness of social media data,” in Encyclopedia of Technology and Politics, ed. A. Ceron (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing), 239–244. doi: 10.4337/9781800374263.nonrepresentativeness

Magin, M., Stark, B., Jandura, O., Udris, L., Riedl, A., Steiner, M., et al. (2023). Seeing the whole picture. Towards a multi-perspective approach to news content diversity based on liberal and deliberative models of democracy. Journal. Stud. 24, 669–696. doi: 10.1080/1461670X.2023.2178248

Matt, C. (2021). Campaigning for the greater good? How persuasive messages affect the evaluation of contact tracing apps. J. Decis. Syst. 31, 189–206. doi: 10.1080/12460125.2021.1873493

Matthes, J. (2009). What's in a frame? A content analysis of media framing studies in the world's leading communication journals, 1990-2005. Journal. Mass Commun. Q. 86, 349–367. doi: 10.1177/107769900908600206

Matthes, J., and Kohring, M. (2008). The content analysis of media frames: Toward improving reliability and validity. J. Commun. 58, 258–279. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.2008.00384.x

Maurer, M., and Oschatz, C. (2016). “The influence of online media on political knowledge,” in Political Communication in the Online World. Theoretical Approaches and Research Designs, eds G. Vowe, and P. Henn (London: Routledge), 73–86. doi: 10.4324/9781315707495-6

Mayring, P. (2019). Qualitative content analysis: demarcation, varieties, developments. Forum Qual. Soc. Res. 20, 16. doi: 10.17169/fqs-20.3.3343

Mestad, A., and Skre, A. B. (2020). Vi må velge mellom pest og kolera. Appen Smittestopp kan være en middelvei. Aftenposten. Available online at: www.aftenposten.no/meninger/kronikk/i/GGLLVm/vi-maa-velge-mellom-pest-og-kolera-appen-smittestopp-kan-vaere-en-midde (accessed November 20, 2023).

Metzler, I., and Åm, H. (2022). How the governance of and through digital contact tracing technologies shapes geographies of power. Policy Polit. 50, 181–198. doi: 10.1332/030557321X16420096592965

Moe, H. (2022). “Norway,” in Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2022, eds N. Newman, R. Fletcher, C. T. Robertson, K. Eddy, and R. K. Nielsen (Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism), 92–93. Available online at: https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2022-06/Digital_News-Report_2022.pdf (accessed November 20, 2023).

Morley, J., Cowls, J., Taddeo, M., and Floridi, L. (2020). Ethical guidelines for COVID-19 tracing apps. Nature 582, 29–31. doi: 10.1038/d41586-020-01578-0

NTB (2020). FHIs smitteapp klages inn for brudd på konkurranseregler. VG. Available online at: www.vg.no/nyheter/innenriks/i/awQVzA/fhis-smitteapp-klages-inn-for-brudd-paa-konkurranseregler (accessed November 20, 2023).

Nurgalieva, L., Ryan, S., and Doherty, G. (2023). Attitudes towards COVID-19 contact tracing apps: a cross-national survey. IEEE Access. 11, 16509–16525. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3136649