- ICD Business School, Head of Quality Assurance, Dublin, Ireland

The focus of this study is to holistically analyse the influence of social media influencers' content on young people's lives in Ireland. To address this main objective, this study aimed to answer the following research question: Who are the five preferred influencers that this young sample follows and what are their motives for following them? To answer this research question, this study analyzed two free-answer questions that were part of a longer questionnaire via thematic analysis using NVivo. This study's sample population comprised 81 participants between 16 and 26 years old, part of the Generation Z cohort and living in Ireland. The results of the analysis indicated five main motives that make this young sample follow their preferred social media influencers. Furthermore, the findings in this study confirm that the sample is susceptible to being influenced by SMIs in different contexts. In this regard, three drivers play a crucial role consist of parasocial relationship, trust, and relatability. Finally, the insights discovered in this research can provide essential information to marketers to support the development of more effective marketing communication strategies.

1. Introduction

Influencer marketing is becoming a popular, trending topic, particularly when contrasted to endorsement marketing, which uses product recommendations from influencers to drive sales (Kim and Kim, 2021). Social media influencers (SMIs) are online opinion personalities with many followers, are experts in certain areas and tend to promote products, services or ideas to generate engagement and shape consumer attitudes toward a brand (Double Click, 2006; Nafees et al., 2021; Klucarova, 2022). Nonetheless, their main objectives include broader outcomes, such as creating content to gain the attention of potential customers, simply being famous, increasing brand awareness, trying to intensify online word-of-mouth effects and creating customer engagement with a product or a brand (Kim and Kim, 2021).

SMIs possess a strong power to promote brands, products and services to generate brand awareness within a specific target audience (Ryan, 2014; Chaffey, 2021; Sánchez-Fernández and Jiménez-Castillo, 2021). A given brand usually contracts SMIs to promote their products, increase sales, raise brand awareness and expand word-of-mouth (Ryan, 2014; Chaffey, 2021; Sánchez-Fernández and Jiménez-Castillo, 2021). In marketing communications in particular, SMIs have become an increasingly valuable community of stakeholders who influence discourse and action and are the opinion leaders of this modern society (Giachanou and Crestani, 2016; Ballestar et al., 2022). This has a vital role in influencing young people in various ways due to their popularity amongst this specific age group (Abidin, 2015; Nafees et al., 2021; Colmekcioglu et al., 2022).

Although social media influencers target all age groups, this article focuses on young people from 16 to 26 years old within the Generation Z cohort living in Ireland. Generation Z is a young people cohort born between 1997 and 2012 that tends to socialize through social media channels, a habit that has considerably modified their time use patterns and social interactions in all spheres (Wood et al., 2021; Borau-Boira et al., 2022; Fan et al., 2023). This generation responds rapidly and has a necessity for immediacy and permanent interaction, even related to social media, where they consider themselves competent users and make use of these channels as their main source of information (Borau-Boira et al., 2022). Borau-Boira et al. (2022) found that Generation Z make more intensive use of Instagram (96%), YouTube (71.4%) and Spotify (49.3%) than other generations. Concerning their approach to SMIs, Gen Zers expect influencers to be interactive, communicative, enthusiastic, credible and inspiring (Borau-Boira et al., 2022). This cohort is therefore an ideal sample group for this research, as they are actively online and tend to follow and interact with SMIs. Ireland was chosen as an accessible location for data collection and research.

The 2021 Sign of the Times survey by the Behavior and Attitudes (B&A) Research and Insight (N = 1.000) reported that during the COVID-19 pandemic Generation Z (classified as aged 16–24 in this survey) have been spending more time on TikTok and Instagram (82%) as an escape (Behaviour Attitudes Research Insight, 2021; Reaper, 2021). This rise might relate to the rise of mental health issues during the pandemic; 70% of this generation feel that COVID has worsened their mental health, and 65% (compared with 43% of the total sample) feel tired all the time (Behaviour Attitudes Research Insight, 2021; Reaper, 2021). Furthermore, the time spent on streaming services as entertainment are also high, with 93% consuming content from at least one online entertainment source (Behaviour Attitudes Research Insight, 2021; Reaper, 2021).

Additionally, the Digital News Report Ireland 2020, a study for the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism at Oxford University, found that Gen Z in Ireland is also increasingly using social media as their primary source for news consumption, growing by 3% points over 5 years (Kirk et al., 2020) with smartphones being used by 71% of Gen Zers as their primary device for accessing news, an increase of 18% points over 5 years (Kirk et al., 2020).

The literature available about SMIs and their impact on young people is limited, even more so regarding the influence of SMIs on Generation Z in Ireland. Borau-Boira et al. (2022) state that SMI is a relatively new topic of academic research; there are still few studies exploring how followers perceive the figure of the influencer, which is crucial to design marketing strategies.

The purpose of the present study is to holistically analyse the influence of social media influencer content on young peoples' lives. This objective can be summarized as the following question: Who are the five preferred influencers that this young sample follows and what are their motives for following them? This article highlights responses to this question through a thematic analysis. This research was conducted in Ireland with participants living in Ireland, and they pertain to the Generation Z cohort aged 16 to 26.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

The sample population was recruited via two educational institutions in Ireland: a secondary school and a private higher education institution. All participants were volunteers, and no incentives were offered to participate in this study. The sample was selected purposively utilizing a homogeneous sampling scheme. The sample size was set according to the purposeful sampling theory that “is based on the premise that seeking out the best cases for the study produces the best data, and research results are a direct result of the cases sampled” (Leavy, 2017, p. 79). First, two educational institutions were contacted, which agreed to participate in this study. Next, written consent was obtained from subjects over 18 years old and from subjects and their parents or legal guardians when under 18 years old.

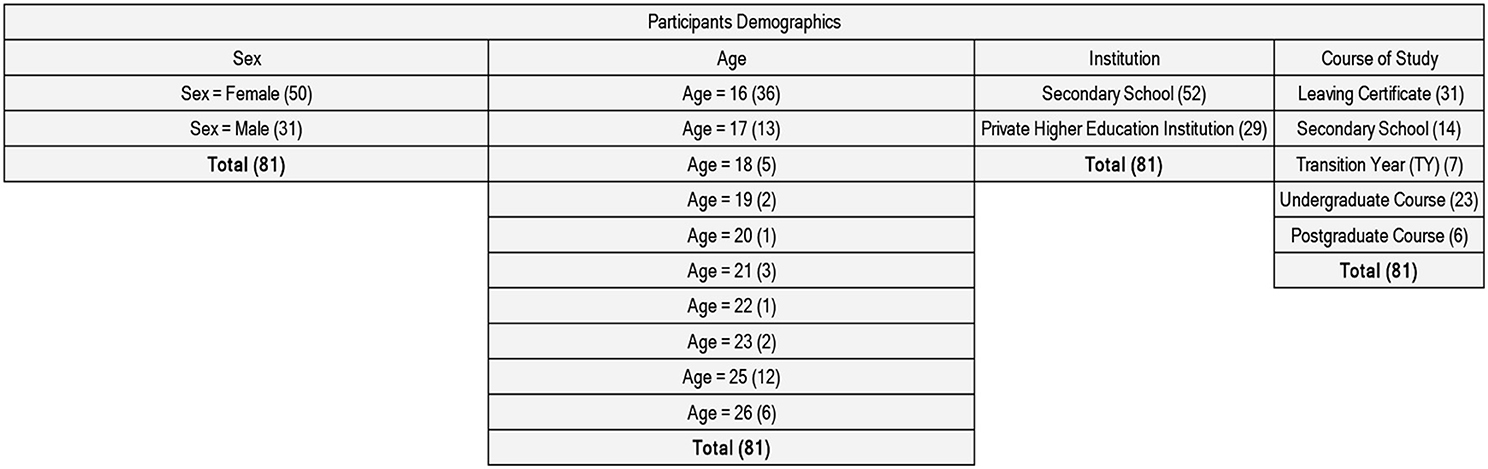

Sample demographics (Figure 1) of the total population (N = 81) are as follows: N = 50 female, N = 31 male; N = 56 ages from 16 to 19 years old, N = 25 ages from 20 to 26 years old; N = 52 are enrolled in a secondary school and N = 29 are enrolled in a private higher education institution (Jackson and Bazeley, 2019; NVivo, 2022). All participants lived in Ireland at the time of study and pertained to the Generation Z cohort.

2.2. Design and apparatus

This article is part of the qualitative strand of the research project “An investigation of the personality traits that could identify young people who will be susceptible to influence by social media influencers (SMIs): the case of Gen Zers in Ireland.” This qualitative strand, utilizing deductive thematic analysis, analyses two free-answer questions part of a longer questionnaire called “Susceptibility to be Influenced by SMIs (SUSIS Questionnaire).” SUSIS Questionnaire is attached as Supplementary material. This method was chosen for accessibility, reliability, and flexibility (Braun and Clarke, 2006).

Two free-answer questions of the SUSIS questionnaire were designed to get as much insights as possible from the participants' responses. These questions are: Q5-Please indicate your five most favorite influencers and in which social media channel you follow them; and Q6-Please indicate five main motives that make you follow your favorite influencers. The responses to these questions directly correlate to the research question of the present study: Who are the five preferred influencers that this young sample follows, and what are their motives for following them?

2.3. Data collection

Data was collected in 2022 at two educational institutions in Ireland: a secondary school and a private higher education institution, in-person, via paper questionnaire. The questionnaire informed the participants about the topic studied, their right to withdraw from the study at any time, that their participation was volunteered, the researcher's contact information and that participants must be living in Ireland and use social media to participate. Then, participants were asked for consent to complete the first section of the questionnaire. All names were replaced by Participant 1, Participant 2, 3, 4, 5, etc., in numerical order.

The participants' views were clear in their answers, writing between one to three lines of text. All text was transcribed from the paper-based questionnaire outlining the 5 favorite influencers that this young sample follows, the channels where they follow them and the motives to be following them. Not all participants filled all blanks or linked the influencers to the specific motives. All Word files were converted to PDF and stored in NVivo.

3. Procedure, material and results

Thematic analysis (TA) is a foundational technique for qualitative analysis because this method offers core skills that are valuable for conducting various types of qualitative analyses (Braun and Clarke, 2006). Thematic analysis (TA) is very commonly used in, but not limited to, psychology and has been previously demonstrated to enable reliable analyses in pragmatic research projects (Penders et al., 2019). This method seeks themes or patterns through a dataset (Saunders et al., 2019). In addition, it is not tied to a specific research philosophy, providing flexibility and straightforward use (Saunders et al., 2019). The TA was designed to be transparent around the process and practice of the method to ensure reliability (Braun and Clarke, 2006).

In this study, a six-phase process proposed by Braun and Clarke (2006) was used to conduct the TA, designed to support the researcher in recognizing and attending to the important elements of a TA, and is a flexible process (Xu and Zammit, 2020). The six phases are as follows: (1) familiarizing yourself with your data; (2) generating initial codes; (3) searching for themes; (4) reviewing themes; (5) defining and naming themes; and (6) producing the report. For pragmatic orientation, a deductive assumption was employed to interpret the data to ensure that the codes could contribute to generating themes that were relevant to answer the research question, as well as to make sure that the emphasized participant/data-based meanings were relevant (Byrne, 2022).

Data were transcribed from the paper-based questionnaires, organized with NVivo 12 Pro and Excel, and then stored (NVivo, 2022). NVivo was then used to sort the qualitative data into codes and nodes, organizing themes and patterns for deep analysis and giving further insights into this research. Influencers, channels and motives were analyzed in different codes. All answers to question 5 in which participants had to indicate their favorite influencers and channels, were researched during transcription for better familiarization with the data and confirmation that the influencers exist and produce online content on the channel listed. Notes about the data were taken (Box 1) due to the importance of documenting the data analysis for transparency (Byrne, 2022).

Box 1. Example of preliminary notes taken during phase 1, elaborated by the author (2022).

“Students have been using the word “relatable” very often”.

“There is a great diversity of influencers, and it might be difficult to find a pattern”.

“Participants always refer to celebrities and singers as influencers”.

“Participants were not assigning the influencers to the motives (Q5 to Q6), they were generalising the motives”.

“Participants tend to be motivated and inspired by their influencers”.

Next, initial codes were generated to categorize data with similar meanings (Saunders et al., 2019). Coding involves labeling each unit of data within a data item with a code that summarizes the excerpt's meaning (Jackson and Bazeley, 2019). This is a process in which researchers are encouraged to examine the entire dataset systematically, treat each data element with equal consideration and identify facets of the data item that may help develop themes (Braun and Clarke, 2006; Byrne, 2022). A code can be a single word or a short expression; a unit of data is a number of words and sentences (Saunders et al., 2019).

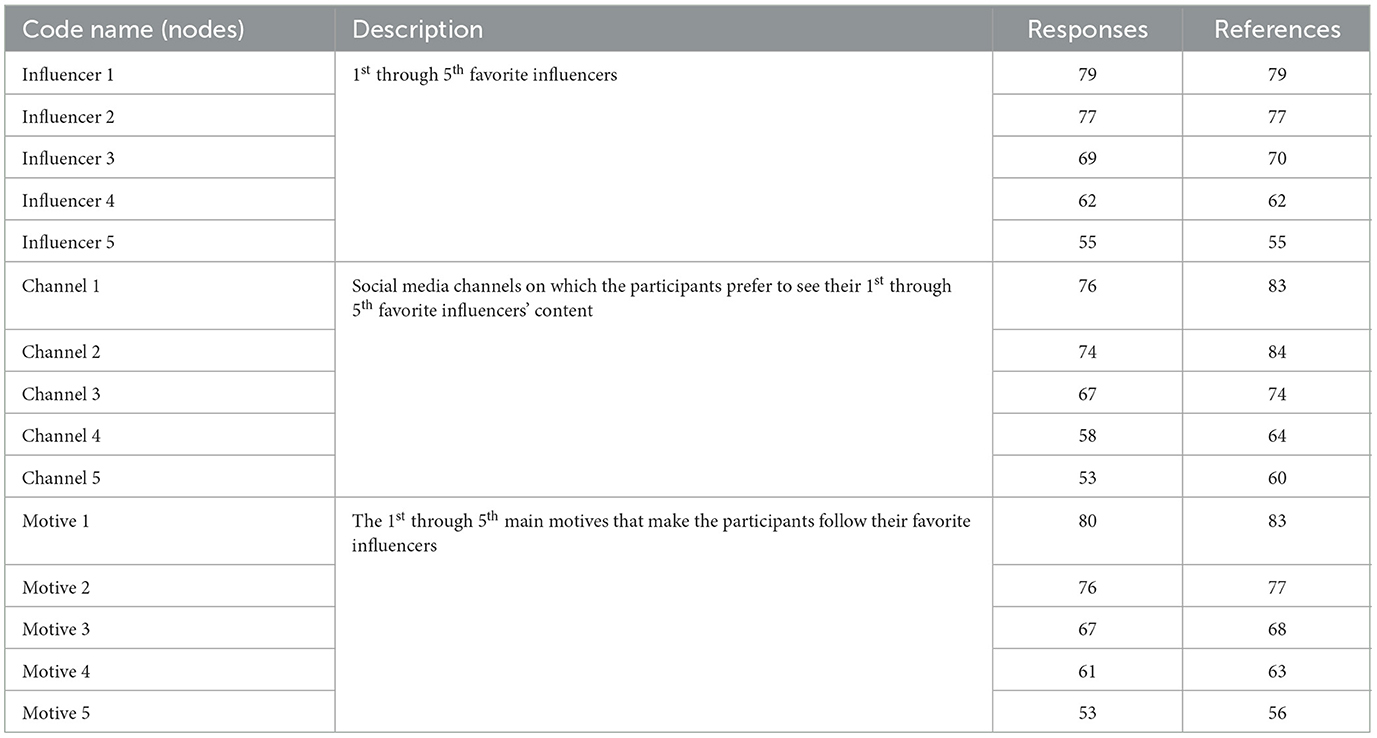

In this coding process, all data that could be useful in answering the research question and contribute to the research question (RQ) were coded to help identify and interpret themes (Braun and Clarke, 2006; Byrne, 2022). A codebook was generated by NVivo, as seen below in Table 1, including code names, descriptions, the number of respondents and the number of references per node, a count of the number of selections within a source coded into a node (Jackson and Bazeley, 2019). As some participants did not fill in all blanks, according to their interests and preferences, the response column varies. Some participants might not have five favorite influencers or five main motives to follow these influencers. The coding process was flexible, thinking mainly about answering the RQ and contribute to the research purpose with influencers, channels and motives receiving their own sets of nodes from 1 to 5.

Table 1. Code book for the influencers, channels and motives, indicating descriptions and numbers of responses and references.

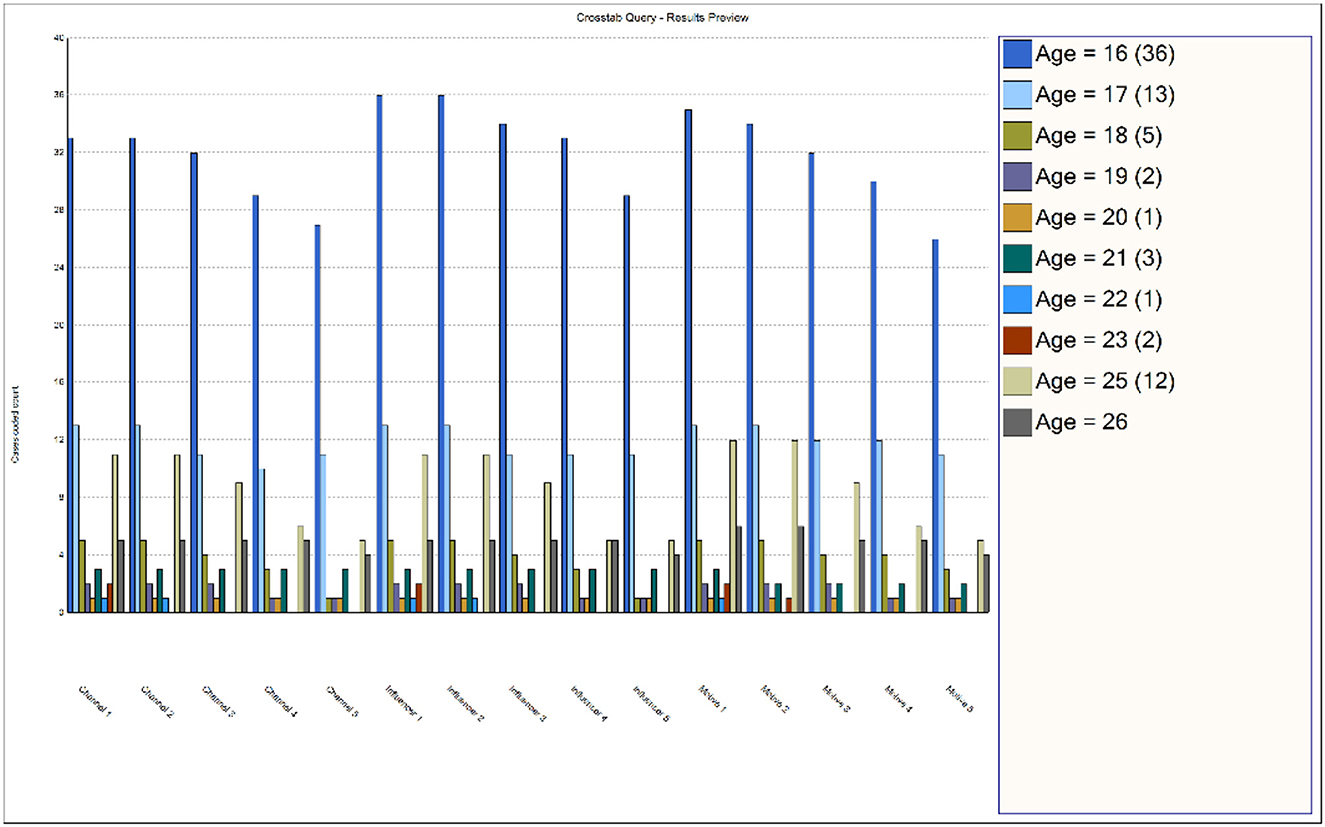

NVivo was used to generate graphs for comparison and interpretation of the coding process, such as the number of cases coded by age (Graph 1) or by sex (Graph 2). Cases represent units of analysis (Jackson and Bazeley, 2019).

Graph 1. Codes by age, elaborated by the author using NVivo (2022).

Graph 2. Codes by sex, elaborated by the author using NVivo (2022).

The highest cases coded were counted in the ages 16 to 17, which composed most of the population, followed by the group 25 to 26 (N = 18). The most cases coded appear in the influencer and motive nodes as these spaces in the questionnaire required more effort compared to channels, which required one or two words (e.g., YouTube, Instagram or both).

After all relevant data was coded, patterns and relationships were identified and a list of themes related to the RQ and research objective was created. A theme is a broader category containing multiple codes that appear to be related to each other and indicate ideas that are generally important to the research question (Saunders et al., 2019).

Delving into the data and codes, judgements were made to create relationships among codes until themes evolved. Six aspects were taken into consideration prior to and during the establishment of themes: (1) the fundamental concepts in the codes; (2) evident patterns; (3) important elements; (4) trends; (5) codes that appear to relate to one another; and (6) reasons as to why and how codes are seemingly related (Bryman, 2004; Braun and Clarke, 2006; Saunders et al., 2019).

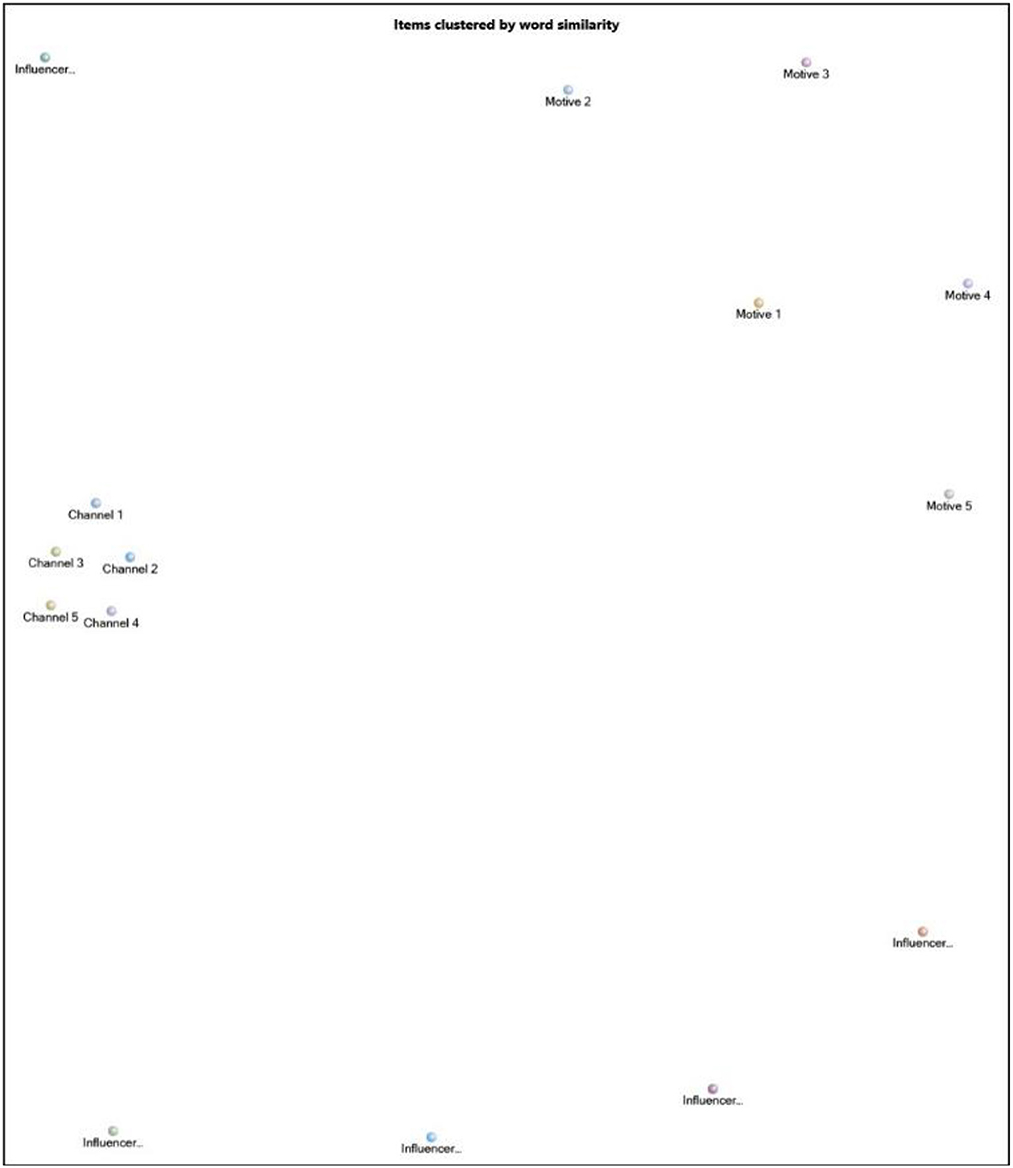

Word similarity was also analyzed using NVivo at a code level and visualized by clustering (Graph 3). The “Channels” element has more word similarities, indicating more patterns. The “Motives” element can generate patterns; however, the similarity is medium to low. Finally, the “Influencers” nodes show a diversity of words, with similarity among only four, indicating that generating patterns in this regard will be difficult.

Graph 3. Items Clustered by Word Similarity, elaborated by the author using NVivo (2022).

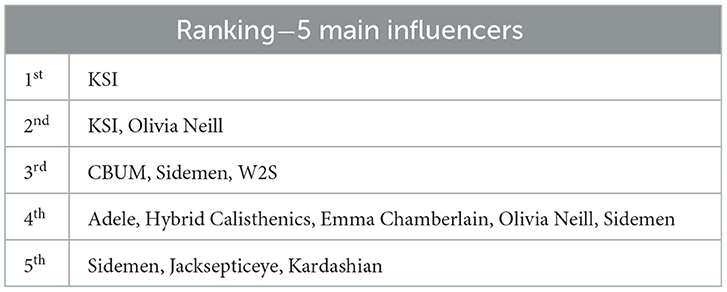

The influencer and channel codes were analyzed first to identify patterns and relationships. As the RQ involves five preferred influencers for this young sample population, patterns were created with a ranking scale from 1 to 5, indicating the first to fifth most preferred influencers. The most cited influencers, channels and created themes were then selected based on this ranking scale. Nodes were then created in NVivo using the theme names for storage.

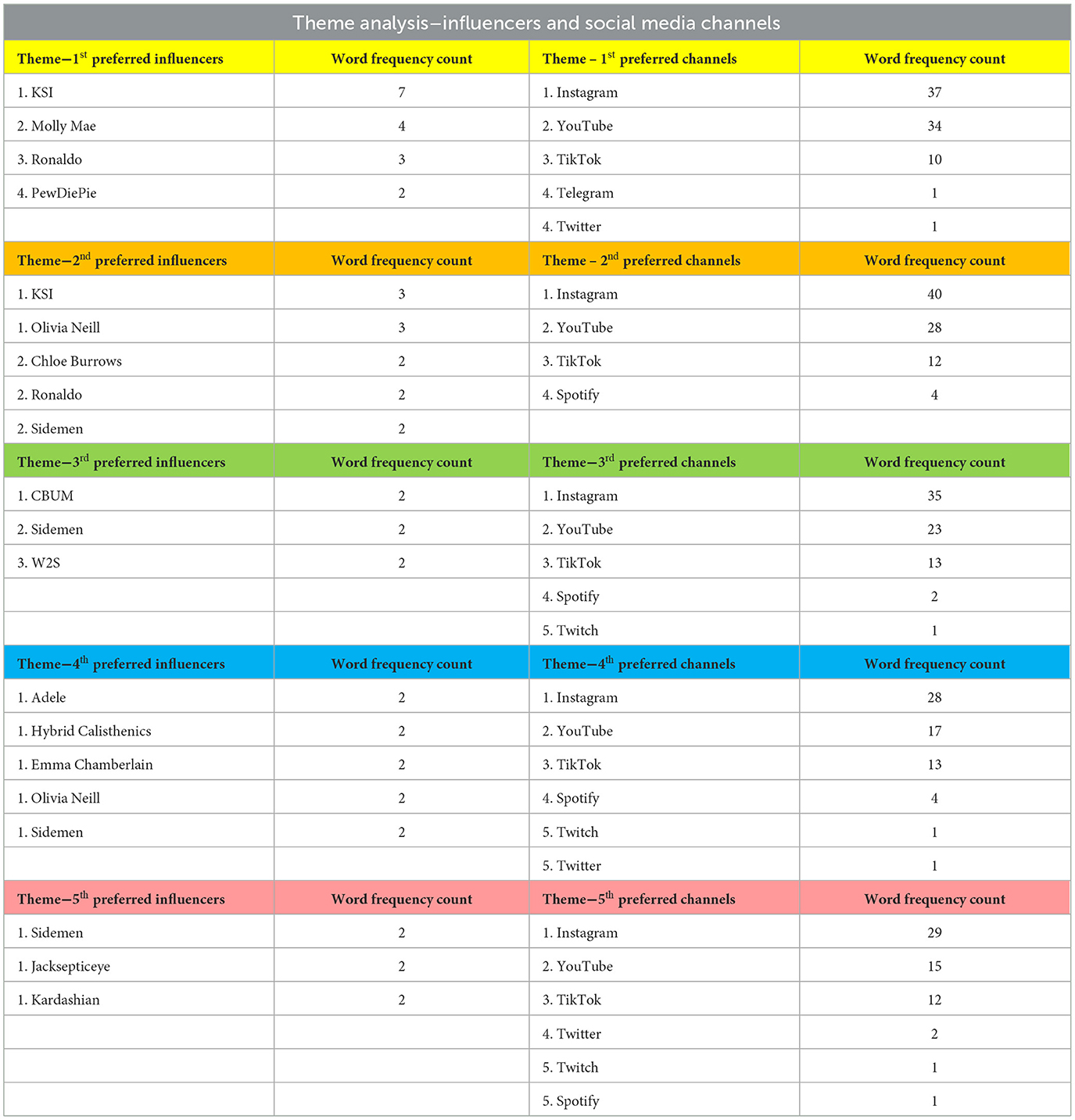

Upon organizing the data, a word frequency analysis was carried out for each node, identifying the most cited influencers and channels (Table 2). To ensure that the entire sample population was considered, all preferred influencers and channels were included in this analysis, not just the most cited examples. This is because, in qualitative analysis, it is essential to explore the participants' views and gather as many insights as possible (Morse, 1994).

Table 2. Word frequency analysis by themes/nodes, elaborated by the author using NVivo (2022).

This word count ranking confirms the clustering data from Graph 3, due to the spread of the data, often ranging from 2 to 7 duplicate citations. This is contrasted with channels, in which frequency counts were much higher for Instagram, followed by YouTube and TikTok.

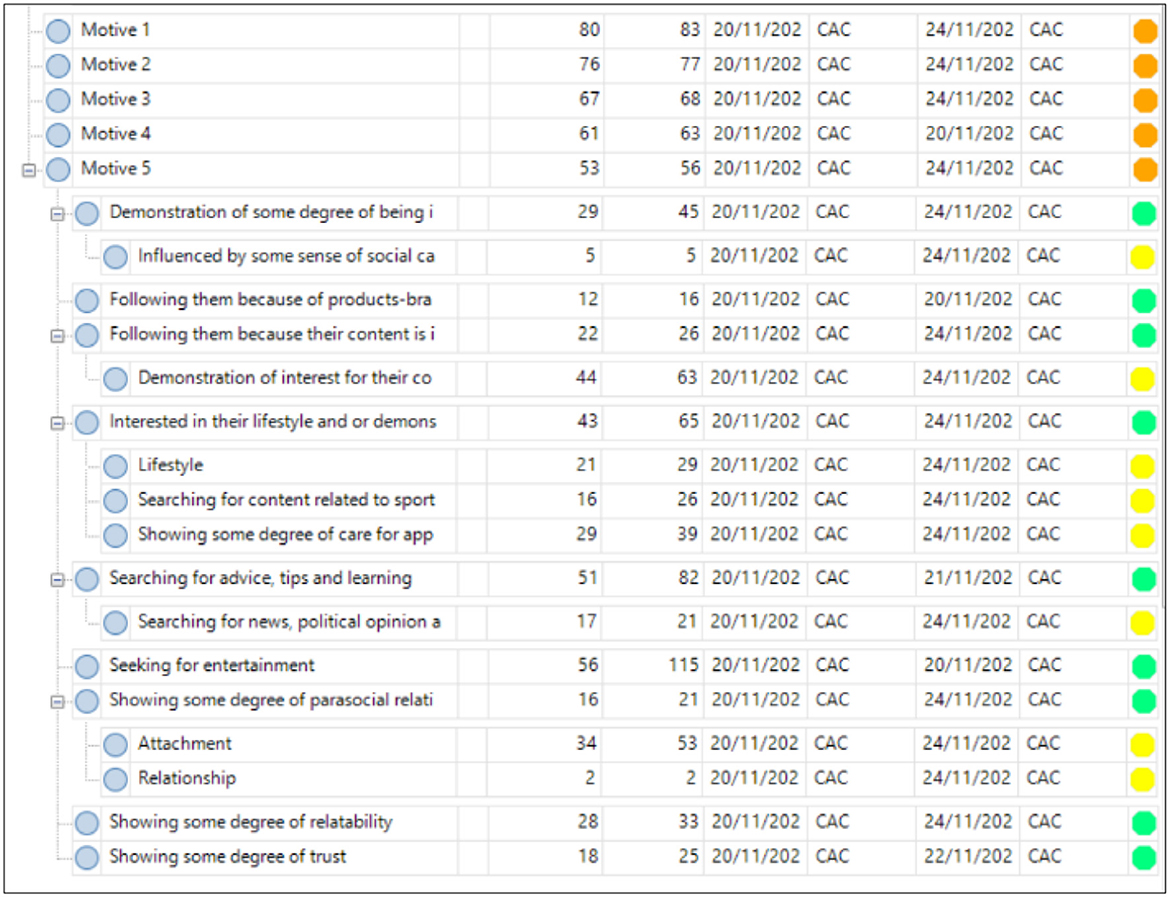

Motive codes were then analyzed, storing the patterns and relationships into new theme nodes using NVivo. Themes were created based on participant responses and experimenter interpretation of these data, taking the RQ into consideration to identify patterns and relationships. Figure 2 below shows an example of theme nodes in NVivo and their connection to codes. This analytical step goes beyond outlining the motives, additionally contrasting and correlating participant responses with theoretical interpretation.

Figure 2. Codes and Themes for Motives, elaborated by the author via NVivo (2022). Orange circles represent codes, green circles represent themes and yellow circles represent sub-themes.

In my analysis of motives, I engaged in a comprehensive process that began with an examination of motive codes, focusing on identifying patterns and relationships to create new thematic nodes within NVivo. The analysis, depicted visually with colored circles for codes, themes, and sub-themes, went beyond merely outlining motives and involved a careful interpretation of participant responses and alignment with the theory. Themes were generated during a third phase, followed by an exhaustive fourth phase where I performed a recursive review of candidate topics, considering factors such as theme quality, boundaries, meaning, and coherence. This meticulous review led to the elimination of themes that did not fit my analysis and culminated in the creation of a final thematic map that significantly contributed to answering the research question and achieving the objectives of the study.

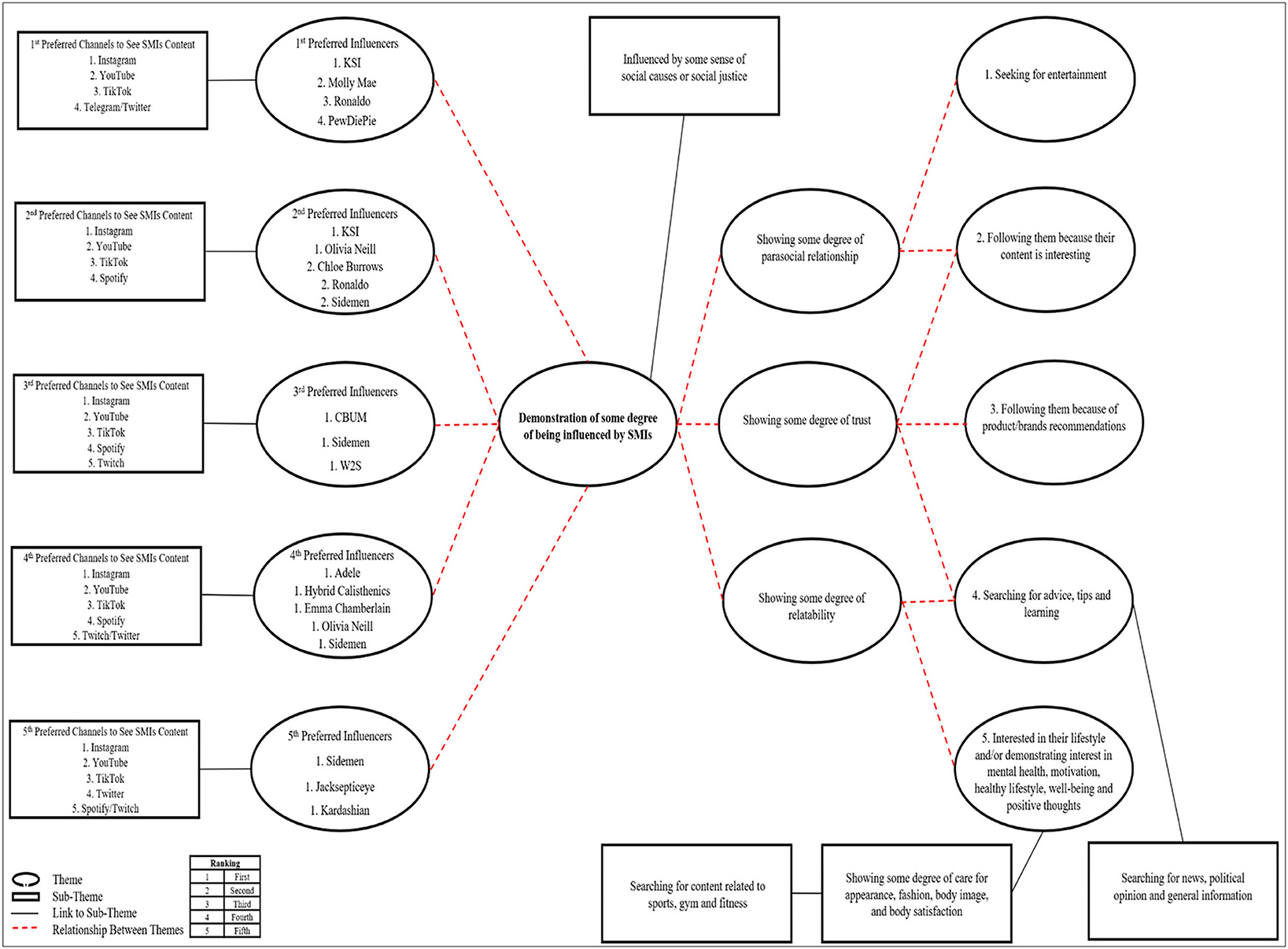

The central theme identified based on the analysis is the “demonstration of some degree of being influenced by SMIs,” since many quotes demonstrate a degree of influence in various ways, including entertainment, motivation, inspiration or some sense of familiarity. Other behavioral themes were generated based on an analysis of the participants' responses and related to the theory covered in this research. These themes are “showing some degree of parasocial relationship,” “showing some degree of trust” and “showing some degree of relatability.” Identifying themes related to these theories provides an insightful answer to the RQ, making comparisons and synthesis possible.

Finally, the last themes created were the main motives to be influenced by SMIs since the influence was evident through their responses. In this analysis, each quote and its power, clarity, linkage to the theory and connection among themes were considered rather than ranking by frequency of a code. Such themes concerning motives are: “seeking for entertainment,” “following them because their content is interesting,” “following them because of product/brand recommendations,” “searching for advice, tips and learning” and “interested in their lifestyle and/or demonstrating interest in mental health, motivation, healthy lifestyle, wellbeing and positive thoughts.” Sub-themes were identified based on occurrences linked to the main themes: “influenced by some sense of social causes or social justice,” “searching for news, political opinion and general information,” “showing some degree of care for appearance, fashion, body image and body satisfaction” and “searching for content related to sports, gym and fitness.” These sub-themes are motives by individuals to make them following influencers.

Next, a recursive review of candidate topics was carried out in relation to the coded data elements and the dataset as a whole (Braun and Clarke, 2006; Byrne, 2022). Some refinement requisites were as follows, (1) if they are themes; (2) the quality of these themes; (3) the boundaries of these themes; (4) if they are meaningful; and (5) if there is coherence in the generation of themes (Braun and Clarke, 2006; Byrne, 2022). A review of the relationships among the data items and codes that inform each theme and sub-theme was then conducted, followed by a revision of the candidate themes in relation to the data set (Braun and Clarke, 2006; Byrne, 2022). After rigorous analysis, 4 themes and 2 sub-themes did not fit into the RQ and were removed. These negative cases should be seen as positive for the research, as the analysis will help refine explanations and interpretations (Saunders et al., 2019).

Once the data were coded and organized, the thematic structure was analyzed and presented to name and define themes that express the RQ and research objective (Braun and Clarke, 2006; Byrne, 2022). The themes were brought together to create a clear and informative narrative that matches the content of the dataset and is relevant to RQ (Figure 3) and research objectives as recommended by the main theorists (Braun and Clarke, 2006; Byrne, 2022). During a final revision, some themes were consolidated without the need to remove or modify any themes.

Multiple excerpts from the data collected were chosen to support the analysis of the RQ in a clear and persuasive way while maintaining the diversity of the participants' viewpoints and the coherence and cohesion of the analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2006; Byrne, 2022). These excerpts were deeply analyzed and interpreted according to its constitutive theme, considering the broader context of the research and the linkage among themes and sub-themes (Braun and Clarke, 2006; Byrne, 2022). This was done by illustratively covering a surface-level analysis of what subjects wrote in the SUSIS questionnaire (Braun and Clarke, 2006; Byrne, 2022).

The themes and sub-themes, outlining the main excerpts from the data in a quotation format, were documented with an illustrative analysis for each theme and sub-theme (Appendix 1). Themes and sub-themes related to channels and influencers were quantitatively ranked and fully and deeply analyzed in the above sections and are therefore not included in this Appendix. The data excerpt table links themes and sub-themes, additionally including an interpretation of participants' views and an explanation as to the ranking of the motives.

4. Summary of findings and discussion

The purpose of the present study was to holistically analyse the influence of social media influencer (SMI) content on young people's lives. To address this objective, this study focuses on the following research question: Who are the five preferred influencers that this young sample follows and what are their motives for following them? This is since understanding motives for following SMIs also led to a better understanding of the influence of SMI content in their lives.

The data and its analysis showed that this young sample population exhibits at least some degree of susceptibility to be influenced by SMIs from different perspectives. The parasocial relationship that is usually attributed to celebrity culture can also be identified in the field of SMIs, and this research supported this link from the relatability, attachment and high level of knowledge about SMIs and their content that participants expressed, as if they were a friend (Horton and Wohl, 1956; Aw et al., 2023). This illusory relationship occurs when influencers show their day-to-day routine, lifestyle and part of their intimate and private life through their posts, therefore establishing an illusory personal bond with their followers (Borau-Boira et al., 2022). Yuan and Lou (2020) outline that influencers are social agents that contribute to the audience's parasocial experience with them, such as through social mediation. Borau-Boira et al. (2022) confirmed that the main defining factors of an influencer's strength for Generation Z are communicative skills (54.5%), dynamism of posts (57.9%) and interaction with audiences (61.7%). Linking these factors with the research data, a parasocial relationship could be inferred between the sample population and their listed influencers. Some degree of intimacy from different perspectives, such as interactive, marketing and disclosive, could be observed.

From a marketing perspective, parasocial relationships can lead to trust, thereby leading to increased levels of purchase intentions and brand evaluations, mainly when the SMI content contains advertising disclosures (Breves et al., 2021). As seen from the data, there is a certain degree of trust related to participant interaction with SMI content. The sample trust their influencers when searching for products and brand recommendations, which can be explained through a high level of parasocial relationship. Additionally, the sample shows some sense of relatability to their SMIs, sharing common characteristics and personality traits. This might be another factor that strengthens the relationship between followers and SMIs, as they perceive their own characteristics and personality in their influencers.

These three main themes–parasocial relationship, trust, and relatability–are the main factors that make this sample susceptible to being influenced by SMIs. Therefore, this influence is the central theme in the present thematic analysis. As such, the answer to the research question is evident in the thematic map (Figure 3), mainly because this map was generated with the research purpose and research question in mind. The main influencers that this young sample follows, sorted by participant ranking, are seen in Table 3.

These influencers can be inferred to influence this sample more than other SMIs as they were cited more frequently. These influencers, a brief description and the type of content they post, their preferred social media platform and number of followers/subscribers can be found in Appendix 2. These data can be useful to improve marketing research as well as to enhance the quality of marketing communication.

The main channels for the influencers are also the most cited social media channels in this study. Instagram is the most cited channel for all five ranking places, followed by YouTube and TikTok. This data is linked to SMI main channels (Appendix 2). This is in line with the understanding that Gen Zers are more present on Instagram and YouTube (Borau-Boira et al., 2022). Channels are important to create more effective digital marketing and integrated marketing communications strategies (Ryan, 2014; Chen et al., 2022).

The various motives in this study are directly connected to the susceptibility of this young sample to being influenced by SMIs since the reasons given are the catalysts that explain their attachment to influencers' content. Many motives exist for the consumption of influencer content, including interest, escapism, community, subjective norms related to the influencer, relatability, influencer authenticity, influencer-related perceived behavior control, attitudes toward the influencer, personal relevance, trust, inspiration and perceived risk (Coco and Eckert, 2020; Chopra et al., 2021; Croes and Bartels, 2021; Klucarova, 2022). In this population of youth in Ireland, five main motives and some sub-themes were documented.

The first motive that makes this young sample follow their influencers was “Seeking for entertainment,” which the sample demonstrated through many quotes, outlined in Appendix 2. This motive has already been referenced in the literature, in which it is related to parasocial relationships and the entertainment value of content to make that content more engaging and attractive. This is especially true after the COVID-19 outbreak, upon which influencer marketing grew and people increasingly turned to social media for entertainment and online social experiences (Kim and Kim, 2021; Rohde and Mau, 2021). This theme is connected to parasocial relationships and the next main motive.

After entertainment, the second main motive was “Following them because their content is interesting,” as indicated by responses that clearly outlined interest in SMI content. While interest in SMI content can make a given person search for and follow the influencer, this varies and depends on each person's interests and needs. This theme is linked to the theme of trust, since the factors that cause participants to show interest are what might lead them to trust the influencers and their content.

Trust is also directly linked to the third main motive, “Following them because of products/brands recommendations.” This is evident from responses that indicated that the participants receive and search for content related to product/brand recommendations, additionally trusting these recommendations. SMIs are well-known to be important in marketing communications to build trust and loyalty (Ryan, 2014; Coates et al., 2019; Hughes et al., 2019; Ki et al., 2020; Kim and Kim, 2021; Rohde and Mau, 2021; Sánchez-Fernández and Jiménez-Castillo, 2021; Zhou et al., 2021; Dinh and Lee, 2022; Masuda et al., 2022). This study shows that SMIs indeed hold an important role in influencing young people to follow brands and buy products and are therefore key players in marketing strategies and should be taken into consideration to enhance the effectiveness of strategies, particularly in terms of digital marketing and social media marketing.

The next motive “Searching for advice, tips and learning” also demonstrates some degree of trust, as they are relying on SMIs to provide advice and be a source for learning. This is in addition to using SMIs as a source for “news, political opinions and general information,” one of the sub-themes. This is in line with the results from the Digital News Report Ireland 2020, which showed that Gen Z in Ireland is increasingly using social media as their primary source for news consumption (Kirk et al., 2020). This is also congruent with the results from a study involving in-depth interviews of small, female sample (N = 18) aged 18–30 years old, in which the participants were more likely to follow the advice of influencers than celebrities, deeming them more credible (Djafarova and Rushworth, 2017).

Finally, the last motive was built based on participant response patterns (Appendix 1): “Interested in their lifestyle and/or demonstrating interest in mental health, motivation, healthy lifestyle, wellbeing and positive thoughts.” This theme is linked to the theme of relatability and two sub-themes: “Showing some degree of care for appearance, fashion, body image and body satisfaction” and “searching for content related to sports, gym and fitness.” This theme and the two sub-themes align with much of the principal content of the five main influencers, including CBUM, Hybrid Calisthenics, and Olivia Neill. This demonstrates interest in the lifestyle of SMIs, as well as different ways of living, such as a healthy lifestyle, digital nomad lifestyle and veganism. In addition, this theme encompasses care for appearance and seeking advice in this regard.

A final sub-theme, “influenced by some sense of social cause or social justice,” is linked to the core theme. This sub-theme might leverage the degree of influence, since some participants show specific interest in influencers that have content related to women's rights, environment/climate change and injustices. Indeed, green influencers who are engaged in climate change and social causes are known to be impactful and engaging among their followers (Pittman and Abell, 2021; Yildirim, 2021).

Additionally, through this holistic analysis the sample population in this study was found to be susceptible to being influenced by SMIs in several different contexts. The main drivers that generated this influence were parasocial relationship, trust and relatability. Different results can stem from such influence, mostly related to entertainment, interest in the content produced by SMIs and product/brand recommendations. From a marketing perspective and the participant responses, it is evident that SMIs have an important and influential role in marketing communication strategies, specifically regarding product and brand recommendations.

Finally, the data analysis of a young sample population reveals a complex relationship between social media influencers (SMIs) and their followers. The susceptibility of these young individuals to be influenced by SMIs is intricately linked to three main themes: parasocial relationship, trust, and relatability. These participants seem to view their favorite influencers as friends, demonstrating relatability, attachment, and extensive knowledge about SMIs and their content. This illusory relationship, fostered through intimate insights into influencers' lives, lays a foundation of trust that impacts participants' purchase intentions and brand evaluations. This trust is further emphasized when the SMIs' content contains advertising disclosures. Influencers like KSI, Olivia Neill, and Sidemen were frequently cited, with their effectiveness in engaging the audience hinging on their communicative skills, dynamism of posts, and interaction with audiences. Thus, the influence of SMIs becomes a central theme, underpinned by the interaction of parasocial relationships, trust, and relatability, shaping marketing strategies and enhancing the understanding of Generation Z's digital engagement.

5. Implications for managers, academics and society

For managers, especially those in marketing and branding roles, the study's findings are crucial. The importance of social media influencers (SMIs) in shaping consumer behavior, particularly among Generation Z, cannot be overstated (Närvänen et al., 2020). Given the strong influence of parasocial relationships, trust, and relatability, managers should focus on these dimensions when choosing SMIs to represent their brands (Närvänen et al., 2020). In particular, managers could use the findings to fine-tune their influencer marketing strategies, choosing influencers who have strong communicative skills, post dynamically, and most importantly, have the ability to interact effectively with their audiences (Sijabat et al., 2022). Given that this study found Instagram, YouTube, and TikTok to be the primary platforms for engagement, focusing marketing strategies on these platforms could yield significant dividends.

For academics, this study adds to the growing body of literature on the influence of social media influencers. The findings illuminate the multi-faceted relationship between influencers and their followers, dominated by the dynamics of trust, relatability, and parasocial relationships (Närvänen et al., 2020). Academics could expand upon this research by examining larger and more diverse sample sizes, diving deeper into the nuanced psychological and social aspects of these relationships. The thematic map and outlined motives can serve as a template for developing more complex models or hypotheses (Kaurav et al., 2020). As a recommendation, future research could also explore the ethical implications of such influence, especially in the context of susceptibility to misinformation.

Societally, the implications are more mixed. On the one hand, the power of influencers to build trust and engagement can be harnessed for positive societal outcomes, such as promoting healthy behaviors or social justice causes (Smit et al., 2022). On the other hand, the study found that some influencers disseminate aggressive gaming content and possibly unreliable information, which could have negative implications (Michaelsen et al., 2022). For policymakers, there is an urgent need to establish a regulatory framework that ensures the responsible use of influencer marketing, especially given its enormous impact on younger populations (Michaelsen et al., 2022). This might include regulations on the disclosure of paid partnerships and the vetting of information for accuracy when SMIs discuss topics like news or health.

In conclusion, this study holds meaningful implications across various sectors. Managers can use the insights to refine their marketing strategies, academics can build upon the foundation laid by this research, and society at large needs to consider the regulatory and ethical frameworks that can harness this influencer power for the greater good.

6. Conclusion

The research objective of this paper was attained, which aimed to provide insights into the factors that lead Generation Z to be influenced by social media influencers (SMIs). The thematic analysis brought a holistic overview of this matter using participant responses and outlined the main influencers, their main channels and the motives for following them. The thematic map from the analysis can be used for, and studied more deeply in, further research studies.

This research offers specific evidence for the influence of SMIs on young people's lives and is in line with previously published findings in the area, expanding it by providing a more focused point of view, given the sampled population. Since motives to follow influencers can differ by age, sex, region and culture, this provides specific insights into Generation Z youth in Ireland. Previous studies as well as the current manuscript show important elements related to being influenced by SMIs in different age groups.

The findings from this study can be useful for marketers to understand the importance of SMIs within marketing communication strategies, as well as to studies from the field of social sciences that aim to explore the influence of SMIs from both positive and negative perspectives. This research does not show direct evidence of harmful content promoted by SMIs, with the possible exception that a few influencers cited by participants might have some degree of aggressive gaming content related to war scenes and/or weapons. In addition, the intent of participants to seek information related to news and political opinion may also be a concern, as the information provided may not always be accurate, intentionally or unintentionally, thereby drastically increasing the spread of fake news as these influencers can reach millions of subscribers. Similarly, the attachment to other information provided by SMIs, such as political opinions, is also concerning.

Acknowledging the limitations of this study is essential to guide future research and ensure a more comprehensive understanding of the issues under investigation. The primary limitations encountered in this research pertain to the sample size and access to the sample population, both of which may have an impact on the breadth and depth of the findings.

The sample size in this study was relatively limited, which may curtail the generalizability of our findings. Given that larger sample sizes have the potential to uncover a wider range of themes and subthemes, the current study's conclusions may not fully capture the richness and complexity of the phenomena under investigation. It is thus recommended that future research in this area consider using a more substantial sample size. A larger sample would allow for a more comprehensive exploration of the themes and subthemes pertinent to this area of study, and provide a deeper qualitative analysis, thereby providing more robust and reliable data.

Access to the sample population was also a significant constraint in this study. The utilization of a paper-based questionnaire distributed face-to-face inherently restricted the population that could be reached, limiting the diversity and range of participants. This might have induced a bias, as those who are more accessible or willing to participate may not be representative of the broader population of interest. It is suggested that future studies could adopt more inclusive and wide-reaching data collection methods. Leveraging digital platforms for data collection, for instance, could facilitate wider access to potential respondents, minimize geographical constraints, and allow for more diverse responses. This would ultimately enhance the representativeness and validity of the findings.

In future studies, an online questionnaire may more easily provide results from a larger sample size. Further analyses should also more deeply investigate the motives that make young people follow their influencers from a cross-cultural perspective, making the results applicable to different counties and cultures. Also, further study can investigate and define different types of influence and content, such as contrasting positive and negative content. Although the findings provide important insights, it is crucial to reflect critically on some aspects of the research, such as explicitly investigating the effect of marketing advertisements promoted by SMIs on young people's lives.

This research clearly highlighted five main factors influencing young people in Ireland to follow their influencers. In addition, this study shows evidence that their favorite SMIs hold influence over this sample in different contexts. Some degree of parasocial relationship and trust are identified through the analysis as drivers of this influence. In marketing communications, marketers can encourage the presence of the factors discovered here to enhance the online presence of SMIs within marketing communication strategies focused on specific target audiences, such as the Generation Z cohort studied here. Marketers might also use this study as a foundation for designing new frameworks and strategies they wish to impose on customers who follow influencers to increase the leverage of a marketing communication strategy by better understanding target audiences and the macroenvironment.

In summary, this manuscript makes a noteworthy contribution to the field by providing a comprehensive analysis of the influence exerted by social media influencers (SMIs) on the lives of Generation Z in Ireland. The research delves into the preferences and motives of this demographic in following specific influencers, thereby illuminating the contributing factors to this influence. The findings underscore parasocial relationships, trust, and relatability as the principal drivers of SMI influence on this young population.

The identified susceptibility to influencer impact is widespread, spanning multiple contexts, including entertainment, content interest, and product or brand recommendations. In the field of marketing, these insights have immense relevance. The research elucidates the paramount role of SMIs in marketing communication strategies, especially in the domain of product and brand endorsements. The insights garnered can be leveraged to bolster the effectiveness of these marketing approaches, thus enhancing their ability to resonate with and influence Generation Z. Additionally, this study contributes to the understanding of how young people communicates with their influencers and the potential impact behind this phenomenon.

Moreover, this study strengthens the existing body of literature by augmenting it with a more refined perspective on the studied population. Despite the limitations concerning sample size and population access, the findings proffer a deeper comprehension of the sway of SMIs over young people's lives. The findings act as a stepping stone for future research, paving the way for explorations into cross-cultural perspectives, varying types of influence, and the impact of SMI-promoted marketing advertisements.

Furthermore, this study goes beyond answering its central research question about the identity and appeal of five preferred influencers for a young sample. It embarks on a thematic analysis to illuminate the underlying motives that make these young individuals follow their chosen social media influencers. With the inclusion of 81 Generation Z participants residing in Ireland, the study findings confirm that these young people are susceptible to the influence of SMIs across various contexts.

Finally, this research offers valuable insights that inform marketing strategy and contribute to the academic discourse on the influence of social media influencers on the youth. It provides a crucial starting point for additional investigations and serves as a vital reference for further scholarly inquiries and marketing practices alike.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by TU Dublin Blanchardstown Campus Ethics Committee. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants' legal guardians/next of kin.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, project administration, resources, software, validation, visualization, writing—review and editing, and roles and writing—original draft: CA.

Funding

This research was partially funded by: Technological University Dublin (2020/21), Irish Research Council (2021/22), ICD Business School Dublin (2022/24).

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank gratefully the guidance of TU Dublin's faculty in the collection of data.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcomm.2023.1217684/full#supplementary-material

References

Abidin, C. (2015). Communicative? intimacies: influencers and perceived interconnectedness. Ada J. Gender New Media Technol. 1, 1–16. doi: 10.7264/N3MW2FFG

Aw, E. C. -X., Tan, G. W. -H., Chuah, S. H. -W., Ooi, K. -B., and Hajli, N. (2023), Be my friend! Cultivating parasocial relationships with social media influencers: findings from PLS-SEM fsQCA. Inf. Technol. People 36, 66–94. doi: 10.1108/ITP-07-2021-0548

Ballestar, M. T., Martín-Llaguno, M., and Sainz, J. (2022). An artificial intelligence analysis of climate-change influencers' marketing on Twitter. Psychol. Mark. 39, 2273–2283. doi: 10.1002/mar.21735

Barry, R. (2022). Who is TikTok star Olivia Neill and how did she become famous? Heat World Blog. Available online at: https://heatworld.com/celebrity/news/olivia-neill-youtube-tiktok/ (accessed August 14, 2023).

Beatty, J. (2021). Marketing Strategies Behind Adele's Success. Embryo Blog. Available online at: https://embryo.com/blog/marketing-strategies-behind-adeles-success/ (accessed August 14, 2023).

Behaviour and Attitudes Research and Insight (2021). The 2021 Sign of the Times Survey. Dublin. Available online at: https://banda.ie/wp-content/uploads/J.202460-SOTT-2021-Online-version.pdf (accessed August 14, 2023).

Borau-Boira, E., Pérez-Escoda, A., and Ruiz-Poveda Vera, C. (2022). Challenges of digital advertising from the study of the influencers' phenomenon in social networks. Corp. Commun. 28, 325–339. doi: 10.1108/CCIJ-03-2022-0023

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Breves, P., Amrehn, A., Liebers, N., and Schramm, H. (2021). Blind trust? the importance and interplay of parasocial relationships and advertising disclosures in explaining influencers' persuasive effects on their followers. Int. J. Advert. 40, 1209–1229. doi: 10.1080/02650487.2021.1881237

Bryman, A. (2004). Quantity and Quality in Social Research (Contemporary Social Research). New York, NY: Taylor and Francis Group-Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780203410028

Byrne, D. (2022). A worked example of Braun and Clarke's approach to reflexive thematic analysis. Qual. Quant. 56, 1391–1412. doi: 10.1007/s11135-021-01182-y

Chaffey, D. (2021). Global Social Media Research Summary 2021, Global Social Media Research Summary 2021 - Smart Insights. Smart Insights Blog. Available online at: https://www.smartinsights.com/social-media-marketing/social-media-strategy/new-global-social-media-research/ (accessed August 14, 2023).

Chen, L., Yan, Y., and Smith, A. N. (2022). What drives digital engagement with sponsored videos? an investigation of video influencers' authenticity management strategies. J. Acad. Market. Sci. 51, 198–221. doi: 10.1007/s11747-022-00887-2

Chopra, A., Avhad, V., and Jaju, S. (2021). Influencer marketing: an exploratory study to identify antecedents of consumer behavior of millennial. Bus. Perspect. Res. 9, 77–91. doi: 10.1177/2278533720923486

Coates, A. E., Hardman, C. A., Halford, J. C. G., Christiansen, P., and Boyland, E. J. (2019). Social media influencer marketing and children's food intake: a randomized trial. Pediatrics 143, 2018–2554. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-2554

Coco, S. L., and Eckert, S. (2020). Sponsored: consumer insights on social media influencer marketing. Public Relat. Inq. 9, 177–194. doi: 10.1177/2046147X20920816

Colmekcioglu, N., Dedeoglu, B. B., and Okumus, F. (2022). Resolving the complexity in Gen Z's envy occurrence: a cross-cultural perspective. Psychol. Market. 40, 48–72. doi: 10.1002/mar.21745

Croes, E., and Bartels, J. (2021). Young adults' motivations for following social influencers and their relationship to identification and buying behavior. Comput. Hum. Behav. 124, 106–910. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2021.106910

Dinh, T. C. T., and Lee, Y. (2022). “I want to be as trendy as influencers” – how “fear of missing out” leads to buying intention for products endorsed by social media influencers. J. Res. Interact. Market. 16, 346–364. doi: 10.1108/JRIM-04-2021-0127

Djafarova, E., and Rushworth, C. (2017). Exploring the credibility of online celebrities' Instagram profiles in influencing the purchase decisions of young female users. Comput. Hum. Behav. 68, 1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2016.11.009

Double Click (2006). Influencing the Influencers: How Online Advertising and Media Impact Word of Mouth. New York, NY: Double Click. Available online at: http://www.digitaltrainingacademy.com/research/2007/08/understanding_social_spaces_ne.php (accessed August 14, 2023).

Excel (2023). Excel Software. Excel. Available online at: https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/microsoft-365/excel (accessed August 14, 2023).

Fan, A., Shin, H. W., Shi, J., and Wu, L. (2023). Young people share, but do so differently: an empirical comparison of peer-to-peer accommodation consumption between millennials and generation Z. Cornell Hospit. Quart. 64, 322–337. doi: 10.1177/19389655221119463

Giachanou, A., and Crestani, F. (2016). Like it or not. ACM Comput. Surv. 49, 1–41. doi: 10.1145/2938640

Horton, D., and Wohl, R. (1956). Mass communication and para-social interaction. Psychiatry 19, 215–229. doi: 10.1080/00332747.1956.11023049

Hughes, C., Swaminathan, V., and Brooks, G. (2019). Driving brand engagement through online social influencers: an empirical investigation of sponsored blogging campaigns. J. Market. 83, 78–96. doi: 10.1177/0022242919854374

Hybrid Calisthenics (2022). Hybrid Calisthenics Website. Available online at: https://www.hybridcalisthenics.com/ (accessed August 14, 2023).

Jacksepticeye Wikidata (2022). Jacksepticeye Wikidata. Wikidata. Available online at: https://www.wikidata.org/wiki/Q20089050 (accessed August 14, 2023).

Jackson, K., and Bazeley, P. (2019). Qualitative Data Analysis With NVivo, 3rd Edn. London: Sage Publications.

Kaurav, R. P. S., Suresh, K. G., Narula, S., and Baber, R. (2020). New education policy: qualitative (contents) analysis and Twitter mining (sentiment analysis). J. Content Community Commun. 12, 4–13. doi: 10.31620/JCCC.12.20/02

Ki, C. -W., Cuevas, L. M., Chong, S. M., and Lim, H. (2020). Influencer marketing: Social media influencers as human brands attaching to followers and yielding positive marketing results by fulfilling needs. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 55, 102–133. doi: 10.1016/j.jretconser.2020.102133

Kim, D. Y., and Kim, H. -Y. (2021). Trust me, trust me not: a nuanced view of influencer marketing on social media. J. Bus. Res. 134, 223–232. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.05.024

Kirk, N., Park, K., Robbins, D., Culloty, E., Casey, E., and Suiter, J. (2020). Digital News Report Ireland 2020. Dublin. Available online at: https://www.bai.ie/en/media/sites/2/dlm_uploads/2020/06/DNR-2020-Report-Web-version_DMB.pdf (accessed August 14, 2023).

Klucarova, S. (2022). Do masks matter? consumer perceptions of social media influencers who wear face masks amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Appl. Psychol. 71, 695–709. doi: 10.1111/apps.12345

Leavy, P. (2017). Research Design: Quantitative, Qualitative, Mixed Methods, Arts-Based, and Community-Based Participatory Research Approaches, 1st Edn. New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

Magnante, M. (2022). Chris Bumstead (CBum) – Complete Profile: Training, Diet, Height, Weight, Biography. Fitness Volt Blog. Available online at: https://fitnessvolt.com/chris-bumstead-profile/ (accessed August 14, 2023).

Masuda, H., Han, S. H., and Lee, J. (2022). Impacts of influencer attributes on purchase intentions in social media influencer marketing: Mediating roles of characterizations. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change, 174, 121–246. doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2021.121246

Michaelsen, F., Collini, L., Jacob, C., Goanta, C., Kettner, S. E., Bishop, S., et al. (2022). The impact of influencers on advertising and consumer protection in the Single Market. Policy Department for Economic, Scientific and Quality of Life Policies, Directorate-General for Internal Policies, European Parliament. PE 703.350. Available online at: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2022/703350/IPOL_STU(2022)703350_EN.pdf [accessed August 29, 2023).

Morse, J. M. (1994). Designing Funded Qualitative Research. Handbook of Qualitative Inquiry, Sage Publications Ltd. Available online at: https://www.scirp.org/(S(351jmbntvnsjt1aadkposzje))/reference/ReferencesPapers.aspx?ReferenceID=928823 (accessed August 14, 2023).

Nafees, L., Cook, C. M., Nikolov, A. N., and Stoddard, E. J. (2021). Can social media influencer (SMI) power influence consumer brand attitudes? the mediating role of perceived SMI credibility. Digit. Bus. 1, 100008. doi: 10.1016/j.digbus.2021.100008

Närvänen, E., Kirvesmies, T., and Kahri, E. (2020). Parasocial relationships of Generation Z consumers with social media influencers in Influencer Marketing, 1st Edn. Oxfordshire: Routledge, 18. doi: 10.4324/9780429322501-10

Neill, O. (2022). Olivia Neill TikTok Page. TikTok Page. Available online at: https://www.tiktok.com/@olivianeill (accessed August 14, 2023).

Nozari, A. (2022). Keeping Up With the Instafam: Kim Kardashian, Kendall Jenner and the rest of their family have amassed more than 1.2BILLION Instagram followers… but who has the most? Available online at: https://www.dailymail.co.uk/tvshowbiz/article-10433771/Kim-Kardashian-famous-family-amassed-1-2BILLION-Instagram-followers.html (accessed August 14, 2023).

NVivo (2022). NVivo Software. Lumivero. Available online at: https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home (accessed August 14, 2023).

Penders, K. A. P., van Zadelhoff, E., Rossi, G., Duimel-Peeters, I. G. P., van Alphen, S. P. J., and Metsemakers, J. F. M. (2019). Feasibility and acceptability of the gerontological personality disorders scale (gps) in general practice: a mixed methods study. J. Pers. Assess. 101, 534–543. doi: 10.1080/00223891.2018.1441152

Pittman, M., and Abell, A. (2021). More trust in fewer followers: diverging effects of popularity metrics and green orientation social media influencers. J. Interact. Market. 56, 70–82. doi: 10.1016/j.intmar.2021.05.002

Reaper, L. (2021). Ireland's Generation Z: The Kids Are Alright, Or Are They? Available online at: https://www.irishtimes.com/life-and-style/ireland-s-generation-z-the-kids-are-alright-or-are-they-1.4520073 (accessed August 14, 2023).

Rohde, P., and Mau, G. (2021). “It's selling like hotcakes”: deconstructing social media influencer marketing in long-form video content on youtube via social influence heuristics. Eur. J. Market. 55, 2700–2734. doi: 10.1108/EJM-06-2019-0530

Ryan, D. (2014). Understanding Digital Marketing: Marketing Strategies for Engaging the Digital Generation. London: Kogan Page Limited.

Sánchez-Fernández, R., and Jiménez-Castillo, D. (2021). How social media influencers affect behavioural intentions towards recommended brands: the role of emotional attachment and information value. J. Market. Manag. 37, 1123–1147. doi: 10.1080/0267257X.2020.1866648

Saunders, M., Lewis, P., and Thornhill, A. (2019). Research Methods for Business Students. 8th Edn. Harlow: Pearson Education Limited.

Sidemen Wikidata (2022). Sidemen Wikidata. Wikidata Subscriber Statistics. Available online at: https://www.wikidata.org/wiki/Q81339539 (accessed August 14, 2023).

Sidemen YouTube Channel (2022). Sidemen YouTube Channel. YouTube. Available online at: https://www.youtube.com/@Sidemen (accessed August 14, 2023).

Sijabat, L., Rantung, D. I., and Mandagi, D. W. (2022). The role of social media influencers in shaping customer brand engagement and brand perception. J. Market. Bus. 9, 1–15. doi: 10.33096/jmb.v9i2.459

Smit, C. R., Bevelander, K. E., de Leeuw, R. N. H., and Buijzen, M. (2022). Motivating social influencers to engage in health behavior interventions. Front. Psychol. 13:885688. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.885688

Wielki, J. (2020). Analysis of the role of digital influencers and their impact on the functioning of the contemporary on-line promotional system and its sustainable development. Sustainability 12, 7138. doi: 10.3390/su12177138

Wood, A. D., Borja, K., and Hoke, L. (2021). Narcissism for fun and profit: an empirical examination of narcissism and its determinants in a sample of generation Z business college students. J. Manag. Educ. 45, 916–952. doi: 10.1177/1052562920965626

Xu, W., and Zammit, K. (2020). Applying thematic analysis to education: a hybrid approach to interpreting data in practitioner research. Int. J. Qual. Method. 19, 1–9. doi: 10.1177/1609406920918810

Yildirim, S. (2021). Do green women influencers spur sustainable consumption patterns? Descriptive evidences from social media influencers. Ecofeminim Clim. Change, 2, 198–210. doi: 10.1108/EFCC-02-2021-0003

Yuan, S., and Lou, C. (2020). How social media influencers foster relationships with followers: the roles of source credibility and fairness in parasocial relationship and product interest. J. Interact. Advert. 20, 133–147. doi: 10.1080/15252019.2020.1769514

Zhou, S., Blazquez, M., McCormick, H., and Barnes, L. (2021). How social media influencers' narrative strategies benefit cultivating influencer marketing: Tackling issues of cultural barriers, commercialised content, and sponsorship disclosure. J. Bus. Res. 134, 122–142. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.05.011

Keywords: social media influencers, Generation Z, Ireland, digital environment, thematic analysis, NVivo, marketing communications

Citation: Alves de Castro C (2023) Thematic analysis in social media influencers: who are they following and why? Front. Commun. 8:1217684. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2023.1217684

Received: 05 May 2023; Accepted: 29 August 2023;

Published: 15 September 2023.

Edited by:

Rahul Pratap Singh Kaurav, Fortune Institute of International Business, IndiaReviewed by:

Nur Aliah Mansor, Tunku Abdul Rahman University, MalaysiaAndrian Haro, Jakarta State University, Indonesia

Copyright © 2023 Alves de Castro. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Charles Alves de Castro, Y2hhcmxlc0BpY2QuaWU=

Charles Alves de Castro

Charles Alves de Castro