- Information-Communication Department, Gériico, University of Lille, Lille, France

This article focuses on the role that algorithms play as a communicative infrastructure that contributes to poorer occupational health in the gig economy by interviewing 50 Uber drivers based on the life-story methodological approach. Specifically, the paper draws attention to Uber structure's managerial algorithmic communication and its effects on drivers' occupational health by engaging with Giddens's theoretical framework of structure-agency and Weick's theory of sensemaking. Furthermore, the study also explores the different factors contributing to the construction of individual and collective resistance of drivers to Uber's monopoly. The findings reveal that Uber's structure imprisons the users' freedom of negotiation and action, which creates a stressful work environment as managerial algorithmic communication only functions effectively in ideal working conditions, while abnormality is very frequent in a profession like transportation. Driver agency consists of organizing individual and collective resistance to change Uber's work decisions and weaken them. On an outside platform, resistance strategies are deployed by drivers to pressure Uber, with the goal of protecting their occupational health.

Introduction

Since its launch in 2009, Uber, a platform that instantly and directly connects drivers with clients, has become an international phenomenon, shifting the way people use and experience transportation (Watanabe et al., 2016). In France, Uber was launched in 2011, but in only a few years, it became a leader in the passenger transport sector. This success is more of a hegemony as Uber resorted to an aggressive development strategy leading to enormous conflicts (Rosell Llorens, 2015), union mobilization (Abdelnour and Bernard, 2020), and legal attempts at regulation (Azaïs et al., 2017; Martini, 2017). Uber's advanced technology is one of the several factors explaining its monopoly of the transport sector, such as “aggressive management”1 (Matherne and O'Toole, 2017), lobbying (Collier et al., 2018; Brugière and Nicot, 2019), sales promotions (Suriyamongkol, 2016), and strategic marketing. For instance, in 2016, Uber launched the “70 000 entrepreneurs” campaign in partnership with the public French administrative institution responsible for employment, “Pôle Emploi”, to target several popular municipalities in Île-de-France, where a population of immigrants and unemployed people is concentrated (Abdelnour and Bernard, 2019). This campaign aimed to facilitate the creation of a VTC company (transport vehicle with driver)2, where Uber drivers often opt for “self-employed” status, forcing them to take control of their economic lives despite their lack of entrepreneurial skills and social security (Ashta and Raimbault, 2009). This meant, for the state of France, a way of absorbing massive unemployment by “recruiting” untrained unemployed people, as stated by the French president, Emmanuel Macron3. In fact, the Uber files4 revealed the implication of Emmanuel Macron in the development of Uber as he contributed to the deregulation of the VTC.

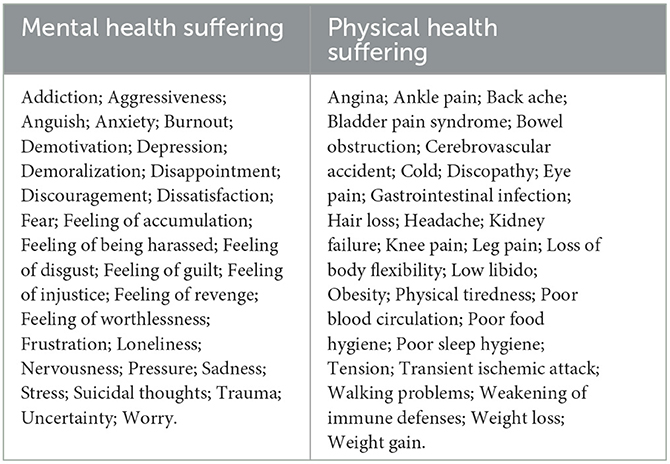

Previous studies have mostly examined the legal status of gig workers and the regulation of digital platforms. For instance, Cherry (2022) explored the “essential worker paradox”, showing how the labor of gig workers was recognized as important during the pandemic but was still treated by the law as outside the bounds of employment protection. Stewart and McCrystal (2019) studied the possibility of a new category of “independent worker” in the gig economy that could be risky as it participates in losing rights and protections for workers. Furthermore, Koutsimpogiorgos et al. (2020) suggested four dimensions to conceptualize the gig economy: online intermediation, independent contractors, paid tasks, and personal services. The authors concluded that these dimensions help to resolve the regulatory issues of digital platforms that depend on political choices as well as national and sectoral contexts. The extant literature highlights the legal and regulatory pressure facing digital platforms (Adams-Prassl et al., 2021), as well as the challenges of labor law (Bargain, 2018), whereas the gig economy generates a significant regression of social protection conquered throughout centuries of social battles5. This downward movement is a backtrack to the exploitation of workers, which puts drivers in precarious positions and endangers their health, as shown in the scarce but growing literature on occupational health in the gig economy. For instance, the study of MacEachen et al. (2018) covered the precarious economic situation of Uber drivers, leading them to engage in unsafe working conditions. Other studies explored the nature of occupational risks and the potential disruptiveness of the health and safety regulatory regime (Cefaliello and Inversi, 2022), particularly during the pandemic, where mental health adversity could be related to financial precarity (Apouey et al., 2020). However, little is known about the ways in which algorithmic communication generates occupational hazards, such as anxiety, depression, stress, frustration, and physical illness, like bladder pain syndrome, obesity, intestinal obstruction, back pain, etc., as well as individual and collective strategic resistance among Uber drivers. Therefore, this study focuses on VTC drivers' narratives about the managerial algorithmic communication of the Uber structure, as well as their sensemaking, which results in agencies organizing an alternative structure.

Based on Giddens's (1984) and Weick's (1995) theoretical frameworks, this study examines the impact of the Uber structure's managerial algorithmic communication on occupational health through the drivers' sensemaking and the agency it results in. There is no theoretical definition of “managerial algorithmic communication”, nor have there been studies on how this concept is related to public health. Management and Communication studies focus on studying “managerial communication” defined, for example, as “communication by management to get something done and accomplish a set of goals through good communication” (Bell and Martin, 2008, p. 127). This “good communication” refers to a set of successful criteria regarding how human managers “assume the downward, horizontal, and upward exchange of information and transmission of meaning through informal or formal channels that enable goal achievement (Bell and Martin, 2014). Drawing on Bell and Martin's definitions of “managerial communication”, this article considers “managerial algorithmic communication” as a form of management that limits the role of human managers by programming algorithms to direct, evaluate, and discipline the workplace (Wood, 2021). This organizational model structures asymmetric corporate relationships to labor (Rosenblat and Stark, 2016), making the drivers subordinates (Amorim and Moda, 2020). Agency refers to individual and collective acts of resistance, such as assemblies at the airport, protests, and strikes, to reshape the dominant structure of Uber and forge an alternative future (Wells et al., 2021). Thus, this study explores the ways in which the Uber structure's managerial algorithmic communication limits action and participation and impacts occupational health and the ways in which agency is expressed by employing various resistance strategies to negotiate, pressure, and change Uber's balance of power.

Structure and agency framework

The asymmetric balance of power between digital platforms and gig workers is structured through asymmetric information translated as “having better or earlier information than others” (Calo and Rosenblat, 2017, p. 1650) and unstable terms and conditions to which the provider must subscribe (Stark and Pais, 2020). When decision-makers monopolize information and impose non-negotiable labor rules on other agents, conflicts take place in organizations, leading to material and symbolic violence (Tirapani and Willmott, 2022). In this context, social inequalities are reinforced as the power structure of digital platforms relies on transferring labor risks to providers, which increases the casualization of work, especially among those with less social and cultural capital (Ravenelle, 2019). For instance, the power structure in the gig economy prevents health benefits to the workers, such as insurance coverage, which increases health risks related to psychological distress, especially in countries without public health systems (Bajwa et al., 2018). Thus, to maintain this power structure, digital platforms resort to motivational techniques, such as gamification, defined as “those features of an interactive system that aim to motivate and engage end-users through the use of game elements and mechanics” (Seaborn and Fels, 2015, p. 14), leading to addictive behaviors (Vasudevan and Chan, 2022). In this article, the structure of digital platforms is examined under the prism of Uber structure's managerial algorithmic communication, which includes the different aspects of asymmetric information and several communication techniques to maintain work involvement despite the absence of effective human interlocutors.

The structural limitations determined by digital platforms also lead to collective and individual agency (Anwar and Graham, 2019; Cant, 2019). Hays (1994) highlighted that “agency is made possible by the enabling features of social structures at the same time as it is limited within the bounds of structural constraint” (p. 62). The agency-structure relationship is, therefore, interconnected as agents and structures influence each other, which allows for the interpretation of agents' actions and behaviors and transcends the agency-structure problem between structuralists and individualists (Dowding, 2008). In the context of the gig economy, Wells et al. (2021) noted that Uber's “just-in-place” management strategy, which aims to decrease time and space in service demand (“Drivers not only appear just-in-time for a customer but also in the [sic] exactly the right place”) (p. 320), isolates and disempowers drivers but also leads to collective worker agency. The example of D.C. airport shows how a spatial strategy for the drivers to resist the platform's power is also a space where Uber continues to deploy labor power. Although this study highlights the importance of collective agency in unbalancing Uber's power, agency in the gig economy can also be driven by purely individual interests, as suggested by Barratt et al. (2020) through the concept of “entrepreneurial agency”. The authors demonstrate how gig workers who accept “the discourse of micro-entrepreneurship” express “‘entrepreneurial' forms of agency, aligning their personal interests, as labor, with capital in market competition and in opposition to the interests of other workers” (p. 1655). Therefore, agency can be both an expression of individual and collective interests (Schwinn, 2007).

Sensemaking framework

Sensemaking is a process of organizing in which people understand retrospectively ongoing circumstances and turn them into words and salient categories to be materialized into identity and action (Weick et al., 2005). This communicative mechanism participates in forming agency, and, thus, organizing which includes material objects and tools, as well as people (Taylor and Robichaud, 2004). For Helms Mills (2003), sensemaking occurs as a result of a crisis or shock6, making it ubiquitous in the context of organizational change. In this article, we focus on six sensemaking properties underscored by Weick (1995): identity construction, retrospection, focused cues that exclude other elements of an event, plausibility rather than accuracy, enactive environment, and social.

The identity construction of gig workers refers to their objective cues that instruct them about appropriate role behavior and their physical, temporal, and administrative affective connection to platforms (Karriker et al., 2021, p. 148). In other words, the identities of gig workers are influenced by their relationship with their “amorphous” organizational working environment, which leads to less emotional engagement (Ibid.). In the gig economy, the variety of individuals, in terms of backgrounds, experiences, and skillsets, provides rich data for researchers because interviewees reflect on their past circumstances differently to explain their current situation (Broughton et al., 2018). This retrospection is selective of cues that the workers choose to support their beliefs when asked, for example, about their intentions to work on platforms despite uncertainty around jobs and salary (Gandhi et al., 2018). Platform workers' attempts to validate a hunch associated with a particular algorithmic action through “data.” It is only available while workers are active on the job (Möhlmann et al., 2023, p.43). The work environment contributes to this process of sensemaking on two levels: algorithmic instructions of the app (validation, surveillance, assessment, etc.), and physical context (road, vehicle, desk, office, etc.). This work environment is enactive because “constraints are partly of one's own making and not simply objects to which one reacts” (Weick et al., 2005, p. 419). Therefore, the social interactions of gig workers are mediated by algorithms that extend the concept of sensemaking to “human-AI interactions” (Möhlmann et al., 2023). Furthermore, the sudden changes in the platform's policy constantly redistribute the level of importance of properties in the sensemaking process.

Although Weick (1995) claimed that each of these properties is equally important to the process of sensemaking, the case of gig workers illustrates the opposite. Algorithm opaqueness favors certain properties over others, as shown in the example of algorithms' technical errors, leading workers to not follow the instructions: “Drivers find glitches by comparing algorithmic instructions or suggestions against real-time road conditions” (Möhlmann et al., 2023, p. 27). Further, Weick's analysis does not approach the structural factors influencing sensemaking. To fill this theoretical gap and show the complementary relationship between the structure-agency framework and the sensemaking framework on which this article is constructed, it was decided that Helms Mills' concept of “critical sensemaking” (2003) would be used. Critical sensemaking focuses on “how organizational power and dominant assumptions privilege some identities over others and create them as meaningful for individuals” (Helms Mills et al., 2010, p. 188).

Drawing on the structure agency and sensemaking frameworks, this study explores the ways in which Uber drivers' sensemaking is influenced by the structural limitations of the platform's managerial algorithmic communication and what communicative mechanisms form agency among these workers. Through 50 semi-structured life story interviews with Uber drivers, this study aims to explore the relationship between the Uber structure's managerial algorithmic communication and agency in the context of precarious working conditions that impact occupational health. In particular, the study aims to explore the ways in which managerial algorithmic communication has shaped sensemaking about occupational health, and in turn, the ways in which the drivers engage in communicative strategies to navigate these limitations. Thus, the study asks the following research questions:

RQ1: How does Uber structure's managerial algorithmic communication with drivers influence their sensemaking?

RQ2: What agentic strategies of resistance were employed by drivers to address the occupational hazards they faced?

Method

At the start of this study, the methodological approach was inductive. To structure the research question, it was necessary to observe the VTC's activity and Uber's operation in the media for a matter of months, as well as to exchange with professionals in the passenger transport sector. Deductive reasoning was employed once the three hypotheses were formulated7, data were collected, and the obtained results were tested to refute or support the hypotheses.

The semi-directive interview of the life story type is the methodological tool employed in this study. The life story, also called the narrative interview, can be defined as “the entire history of a person. It would begin with the birth or even with the history of the parents, their environment, in short [sic] with the social origins. It would cover the entire life history of the subject” (Bertaux, 2010, p. 35). However, the last diploma obtained, and the first work experiences of the interviewees serve as the starting point for this study. Work is the main theme of this research, which justifies this choice. Nevertheless, not all the questions were focused on work experiences, which would have prevented the use of the life story approach. The respondents' answers always included elements related to their personal life or other topics.

Life story methodology enables the collection of abundant data, but it restricts the scientific approach to research. Bourdieu was highly critical of this methodology as he pointed out that individuals' lives are a coherent and oriented story that follows a chronological order, and therefore a logical order (Bourdieu, 1986). The purpose of choosing semi-structured life story interviews in this study was to gather various data that can be categorized using a previously defined interview guide. Combined with the tool of life story that takes an interest in the psychic and subjective life of individuals who express themselves without a structured direction, semi-structured interviews permit the collection of rich and homogeneous content to identify correlations and categorizations that must guarantee the scientific nature of the research.

Participants

A total of 50 Uber drivers were interviewed, ranging in age from 25 to 66 years. Of them, 26 drivers were aged between 25 and 39 years old, 20 were aged between 40 and 53 years old, and 4 were aged between 55 and 66 years old. In total, 39 of these drivers were men and 11 were women. The sample includes participants from different geographical areas to obtain a better understanding of how Uber structure's managerial algorithmic communication may vary depending on external factors, such as clients' demands, public transport accessibility, tourist offers, and legal context. At the time of the interview, 41 were living in Île-de-France (Parisian Region), 6 were living in Hauts-de-France (Lille region), and 3 were living in South Provence-Alpes-Côte-d'Azur region (Marseille region).

Of the 30 participants, 29 had had a college education, 5 had attended high school, 15 had attended junior high school, and 1 had attended primary school. Among them, 22 of the participants belonged to drivers' unions, and 28 did not. Among the 50 participants, 12 were single, 32 were in a relationship or married, 5 were divorced, and the remaining 1 was a widow.

Recruitment

Recruiting Uber drivers took place at the drivers' union premises, outside the Uber premises, in online forums, and via social media. The first contact obtained was with the general secretary of a private drivers' union in France. The meeting with this professional worker allowed other contacts from Uber drivers to be subsequently obtained, with whom interviews were conducted. However, it was necessary to diversify the means of getting in touch with this study population to obtain a wide variety of perspectives and stories. Therefore, it was decided that other drivers' unions, Uber premises, online forums, and social media groups, such as on Facebook and X (then Twitter), would be targeted. This strategy functioned despite the innumerable difficulties encountered in convincing the drivers to participate in the sample. Such an obstacle is justified by their work flexibility, but also the mistrust and the fear they express when it comes to speaking about their work experience on Uber, despite the assurance of anonymity. One of the tools that helped to gain their trust is an investigation blog that was created for this study and was animated by several articles and testimonials from Uber drivers. This blog has also helped to obtain approximately 10 new contacts as some Uber drivers voluntarily asked to participate in this study and suggested it to other drivers. In fact, this blog pointed out and gave credibility to this study in the online VTC community because several drivers were afraid to testify lest they be suspended by Uber. After the first COVID-19 lockdown, the rest of the interviews were carried out via Zoom, WhatsApp, and Messenger.

Data collection

Semi-structured life story interviews were organized to explore Uber drivers' experiences and sensemaking about managerial algorithmic communication of the platform and its impact on occupational health as well as communication strategies they employed to resist. For instance, examples of the interview questions include “How do you describe your relationship with the platform Uber?”; “When you disconnect from the app during your timeout, do you feel like you are missing opportunities...?”; “What forms of exhaustion or physical illnesses have you developed since working on Uber?”; and “Do you think you need to be part of a drivers union to improve the platform's communication model?”. The interviews were conducted in French between November 2019 and October 2020. Interviews lasted between 35 and 110 min. Interviews were transcribed verbatim in French, resulting in 308 pages of 1.5-line spacing text, in font size 9. Pseudonyms are used for confidentiality. Verbatims that were identified as coherent for use in this article were translated from French to English.

Data analysis

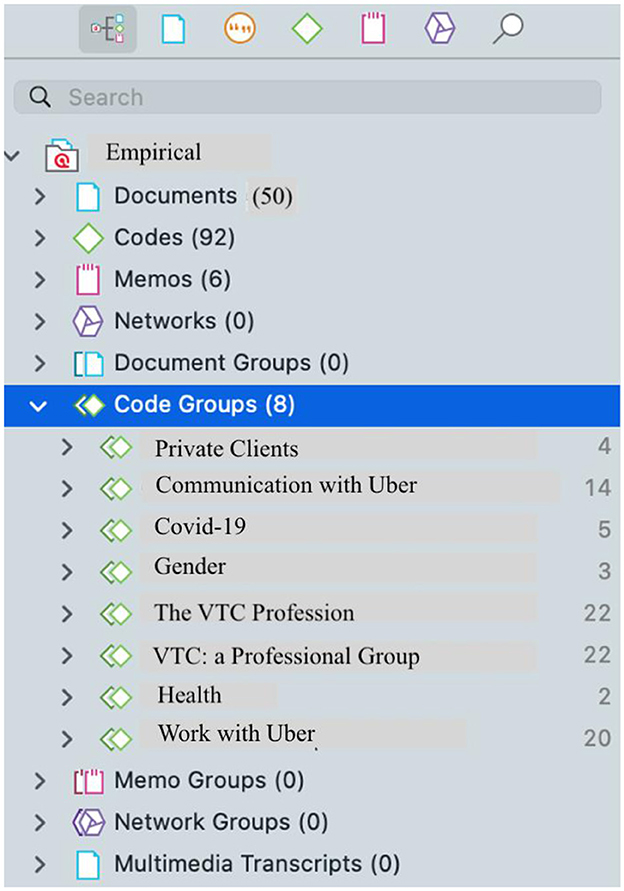

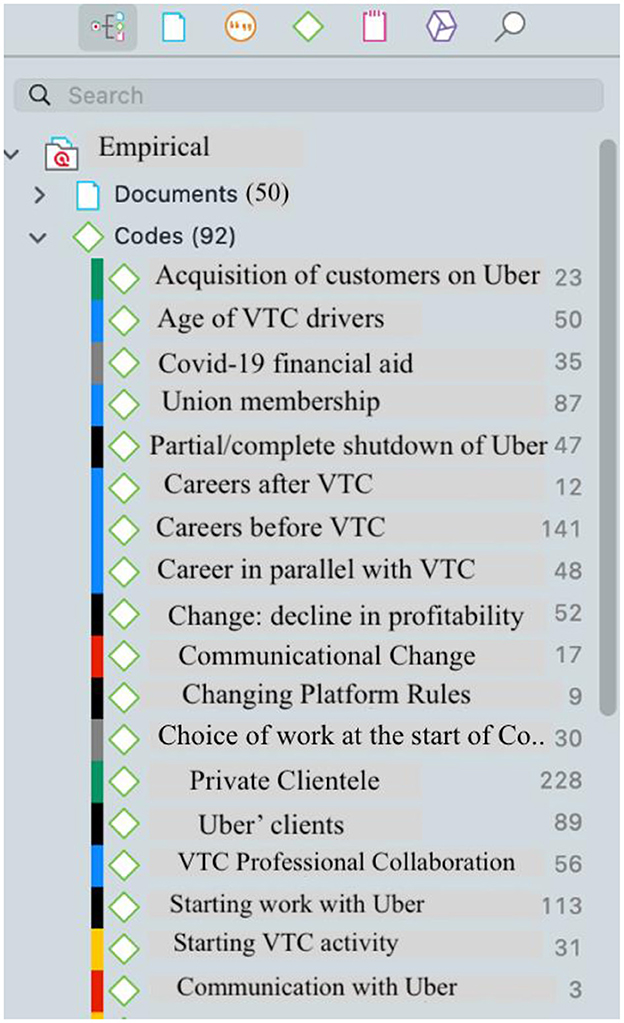

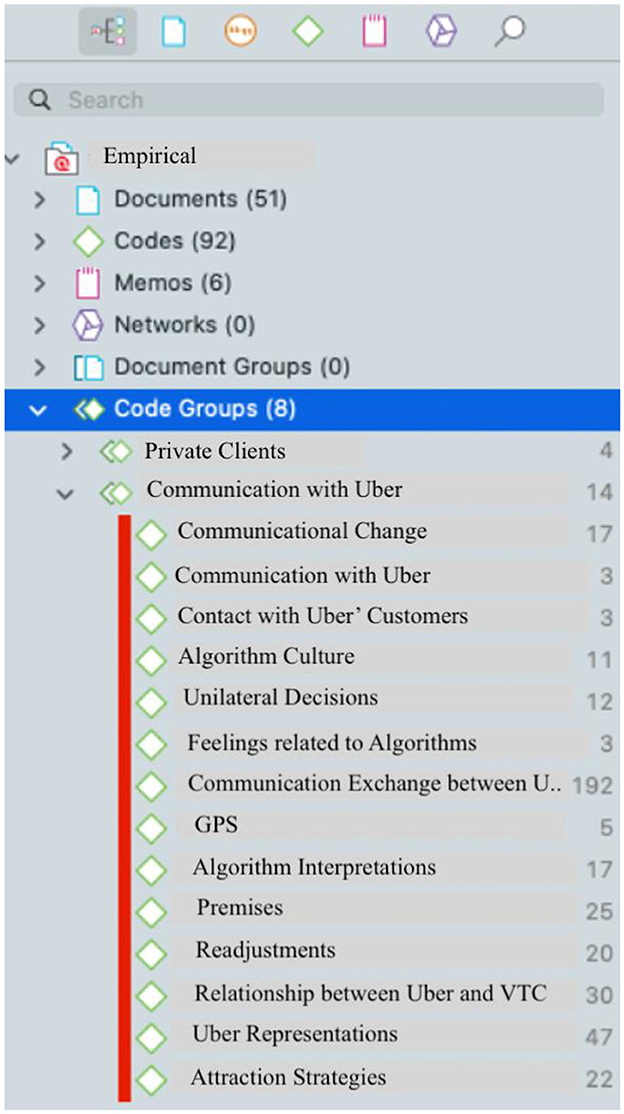

The transcripts were analyzed using the qualitative processing software ATLAS.ti, resulting in the creation of a project named “Empirical”. The 50 transcribed interviews were inserted into Empirical. Then, 92 codes were created and distributed in eight groups of codes based on their belonging to the themes of these groups (Figures 1–38). If a single verbatim addresses multiple ideas related to the defined themes, multiple codes can be assigned to it. When used outside of its original context, the coding must be sufficient to be meaningful.

The use of ATLAS.ti can take several logics. In this study, the use of this software is justified by the large amount of data that the survey represents. The goal was to use the software's different functionalities for presenting the results and easily access the 3,380 coded quotations. In other words, features of ATLAS.ti such as Code Co-occurrence Explorer, Code Co-occurrence Table, Code-Document Table, and Query Tool were used to access the nested codes identified to test each hypothesis, to gain a preliminary understanding of the correlations between the codes and to determine the codes that were frequently tackled in each interview. Therefore, this article uses manual analysis of data that was facilitated by ATLAS.ti for access and organization.

The codes were relevant to the theoretical constructs for Uber's structure and its managerial algorithmic communication, agency, and sensemaking, as well as codes that brought out the profession of private drivers. For example, some of the defined code groups were algorithmic communication with the platform; private clients; professional groups of drivers, occupational health, and working with the platform. To answer the research questions, three themes were defined by selective coding: Uber structure's managerial algorithmic communication, sensemaking of the working experience, and resistance as agency.

The structure-agency and sensemaking frameworks helped to structure data analysis. This study focuses on codes relevant to Uber drivers' perception and sensemaking of managerial algorithmic communication and their sense of agency to resist these structural limitations and create an alternative organization of work. Codes concerning the profession of the private driver were also identified and informed by literature review concepts, such as social visibility, symbolic legitimacy, and deprofessionalization, within the sociology of professional groups (Demazière and Gadea, 2009; Vezinat, 2016).

Findings

Uber's structure is based on asymmetric information that transforms communication, that is, negotiation, collaboration, and dialog with drivers, to mechanical interaction between the driver and the app.

Furthermore, Uber's structure is organized using algorithmic management techniques that reduce the complexity of the driver's work to simple prediction situations, as they can be modeled. The findings also reveal Uber drivers' sensemaking of the working experience and agency they have deployed to resist a structure that is impacting their occupational health.

Uber structure's managerial algorithmic communication

Uber's structure is organized through a set of informational features requiring constant mechanical interaction between the driver and the app. For instance, the driver must press “GO” on the app to start receiving orders. Then, the driver is led either to accept the requests or to cancel them as long as the cancellation rate is not exceeded. When taking the ride, the driver must follow the route dictated by the app and drop off the client at the requested destination. Furthermore, Uber provides the driver with a feature to rate the client. The driver selects a comment from a series of available suggestions (good client, sociable client, alcoholic client, etc.). Participants noted that Uber's platform is structured through a set of norms and rules limiting their actions and transforming their profession to repetitive mechanical tasks. Amine noted that this organization disregards the drivers by imposing an unfair algorithmic functioning in terms of hourly rate, approach time, and all the other operating rules:

If we are “partners” as Uber always says, we have to be so in the truest sense of the word. However, we can't negotiate the prices, the customers… We have all the disadvantages of being independent contractors and of being fictitious employees because we have a relationship of subordination.

Amine highlights that Uber is a paradoxical structure requiring drivers to work long hours in an environment with no effective interlocutor. Uber delegates management and decision-making mostly to algorithms incapable of understanding the sensitive reality of the VTC activity. For instance, when a client reports critical information about the driver, generally, the latter is automatically threatened to be suspended or suspended from the platform. Helene said:

To my great surprise, Uber suspended me because there was a customer who complained about the seat belts, he said that they weren't there when they were just a little behind. Instead of asking me first, they suspended me. When I arrived at the airport, they told me “You can't connect”, I called, they answered, “You don't have seat belts”, I said “Of course I do”, they said “Send us pictures”, and I did. I was reconnected 4 hours later.

Helene experienced a lack of stability as she realized how her work can be threatened by just a client's comment in the app and how it is important to not rely entirely on Uber for income. Such dependency is, however, constantly reinforced by the platform to maintain its structure and, therefore, its monopoly of the VTC sector through different information techniques to influence driver behavior. For instance, Halim shared:

This job is like a video game… It consists of chasing after the mark-up because the basic pricing is not interesting, it's a lost… It must be illegal, but no one is complaining because people do not necessarily know their rights or do not necessarily know how to structure themselves.

Halim's statement illustrates how work in the app can be triggered by an addiction mechanism. This addiction exceeds the professional sphere and becomes an obsession, chasing drivers even during rest days. The practice transforms into habit, troubling the mind and making it hard to disconnect from a job that is carried everywhere by a digital device. Mamadou shared:

It happens to me when I'm not working, at certain times, for example on Saturdays at 11 p.m. or midnight I look at the phone and check if the price has increased… These are reflexes that we always do… I still have it even though there is not as much markup as there was then. I know that on weekends, I look at the phone to check if the price has increased and at what part on the map…

Uber structure's managerial algorithmic communication is also explained by how the design elements of the app affect the working experience. The drivers recognize that one of the main reasons why Uber succeeds in attracting an important number of new drivers is because of its design, which stimulates addiction and deprives work of any sort of intellectual and creative effort. Bassim explained:

In the app, everything is simplified, you don't need to go any further. You just go to a circle there and you're going to click, it's intuitive, that's all, and after you have navigated at the bottom, you immediately have another window in parallel in the application, either Google Maps or Waze, which opens and you are just going to drop the client from point A to point B. After you finish your ride, it's repetitive, you go on, you do the same thing again, you go on, you do the same thing.

This lack of work complexity makes the VTC experience meaningless and does not foster building social relationships with clients. The duration of transportation is often short, and the quantity of rides is important, which fortifies the loneliness of drivers and deteriorates the VTC profession. Matthew said:

You meet a lot of people, people from all over the world, from all places, from all walks of life, and you have a feeling of loneliness, real loneliness. You don't sympathize, and even if you do, the ride lasts on average 20 min or half an hour, and during this time, we will have a conversation, but that does not mean that you create a relationship… People are often on the phone or lost in their thoughts… So, there's a real loneliness of being the driver.

Both Bassim and Matthew highlight the ways in which Uber structure's managerial algorithmic communication is depriving their working experience of meaning. This communication system reinforces an asymmetric balance of power between Uber and drivers and cultivates addictive practices at work that are likely to impact occupational health. Moreover, Uber drivers complain about a lack of profitability. Reda shared:

It is stressful, especially when you're given a ride command far away. Sometimes I'm in Porte d'Auteuil and I'm given a command to go pick up someone in Versailles… And when I see the mileage of that, it's not worth the cost because Uber only starts counting the price from the moment you pick up the client (…) So not only it is not profitable, but you must have an elephant's health because it's too demanding driving people when you're not used to driving 8 h a day.

This experience highlights that the Uber platform is an algorithmic managerial communication system carefully structured in such a way as to create and reinforce worker dependency. Uber's algorithms are incapable of comprehending the complexity of VTC work as they are programmed to repeat a certain logical interaction, regardless of the different situations. The gap between the reality of work and algorithmic modeling is usually manifested in conflicting situations, where drivers are suspended or are threatened with suspension because of a bad client assessment or an elevated rate of ride cancellation. The drivers try then to communicate with the “human” part of the Uber platform, which is reduced to reception staff and usually telephone advisers from call centers abroad. Both forms of “human communication” are inefficient because the stuff has little knowledge of VTC work and no decision-making power. Therefore, communication remains standardized as the real decision-makers are inaccessible and unknown, which drives Uber drivers toward internalizing their feelings. The risk of experiencing suffering at work intensifies to different degrees according to each driver's sensemaking of the working experience.

Sensemaking of the working experience

The professional group of VTC drivers is heterogeneous. Their organizational practices, like work schedules, traffic areas, customer relations, car model, professional equipment, and driving style vary and differ according to a multitude of factors ranging from past experiences, educational background, religious beliefs, and family situation to structural constraints that were reviewed previously by presenting Uber structure's managerial algorithmic communication. The drivers' sensemaking is a complex process that is constantly renewed, on the one hand due to personal factors, and on the other hand because of the evolution of the VTC sector, the changes in the Uber structure, and the ways it is managed by algorithmic communication. For instance, Mahfoud, who in the past worked in the luxury hotel industry and in the Grande Remise9, mentioned that he prefers driving in “upscale neighborhoods” but must also adapt to the standards of the app, which ultimately changes his professional practices. He said:

I've been working with Uber since the beginning and there was a period when I had the impression that I was devalued, that my job had deteriorated. Before, when I was a Grande Remise driver, whenever I went to a cafe in Paris, people had respect for me because they saw the Mercedes; they asked “For whom do you work?”, I was well dressed, suit and tie, I used to have a lot of tips, so I used to invest in a nice watch, nice shoes… Now I feel like I've gone down a level.

Mahfoud's story shows how past experiences influence current representations of work and play a role in the organization of professional practices despite structural constraints. In the same way, having had a difficult job in the past and just starting work in the Uber platform alters one's perception. For instance, Bilel recounted how working previously in a hectic environment in the automotive industry and switching career paths several times facilitated his adaptation to the Uber platform. He shared:

I started working as a driver a couple of months ago and I think it's the first time in my life that I'm doing a job by choice. I don't know if it's going to be the best or the worst, I'll draw conclusions in the future but, for the moment, it is an available job with which people have been able to cover their expenses, especially when you go through a rather delicate situation [referring to COVID-19].

The different perception of work between Bilel and Mahfoud highlights how sensemaking is mostly oriented by past experiences and requires time to construct a new narrative about the current working condition. Religious beliefs are also a key element in putting into perspective work events. The case of Youssef illustrates how the Uber structure's managerial algorithmic communication triggers a permanent feeling of injustice that generates frustration and stress and how religious practice helps to accept the situation and surrender without feeling defeated. He noted: “My faith in God is growing. I stop worrying about petty things. This money comes and goes. I don't care anymore.” Religious beliefs are also a source of hope and strength, as Issam believes. He shared:

As a Muslim, we don't see things the same way. We say to ourselves that we will not have more than what we should receive, we are missing out on a lot of things, we make do with the essentials. I have a child with a disability; when he was born, the doctors told us that he would only live until the age of 4 years and then suddenly he is 13 today.

Issam's account highlights how religious beliefs serve to interpret personal events through which sensemaking about work experience is constructed. At the time of the interview, Issam shared that he no longer depends on Uber and had managed to build his own private customer base. In this case, several factors combine to allow a driver to break away from Uber's grip, in particular, work area, capital, and entrepreneurial skills. Soufiane, who is a trade unionist, explains that Uber takes advantage of the educational and professional weaknesses of the drivers it seeks in poor areas. He noted:

The real entrepreneur is the one who will get contracts, which is a difficult thing to do. It's not easy for everyone. These drivers [Uber drivers] are lost people. There are taken advantage of them because they have no diploma, no future, they live in the suburbs, they have origins, etc. The true entrepreneur will seek embassies, markets in the United States, markets for travel agencies...

Soufiane's statement about “real entrepreneurs” mainly refers to former Grande Remise drivers, who, since the arrival of Uber, have become VTCs. Thus, Uber's hegemony in the VTC market complicates the process of acquiring and retaining clients. It is the case of several drivers who lost their private clients after the arrival of Uber. Therefore, the VTC drivers' professional group is heterogeneous because of its social identity deconstruction and the appearance of new hybrid logic that defines it. For instance, the great media coverage of this sector and the significant sharing of work information on social media allow people who want to switch to this profession on platforms to be better prepared. Yasser shared:

I did my research and I realized that it was not all rosy, especially the psychological pressure. For example, if you take a loan to buy a car, it's risky because Uber can suspend you at any time, so it puts pressure on you. As I was warned about this fact, I came in with my own funds, I paid for my mid-range vehicle to precisely have this freedom to be able to work as I want, with the risk of suspension but with less pressure.

Yasser's account demonstrates a strategic plan to live off an insecure and unstable job, but it doesn't avoid the “psychological pressure” Uber puts on drivers. Similar strategies were noted among other participants who felt even more secure when they came from a stable social environment. Solene shared:

I'm married, my husband works, so that makes the two of us. If I were alone, I would have thought twice before working for Uber, especially in this period [referring to COVID-19]. So, the fact that I have my husband who works means we have two incomes. Otherwise, with what I do as an Uber driver, if I was alone, no, I don't think I would get by.

Both Solene and Yasser's sensemaking of work highlights a social reality where workers have to deal with instability and insecurity to make a living. There is a legal and political context, which has certainly been changing in recent years, but since the installation of Uber in France, has tolerated this platform to destabilize the driver's activity. Uber drivers experience different sensemaking processes regarding the platform's managerial algorithmic communication but agree that no matter how they've been strategic, optimistic, and adaptative, they've all experienced both mental and physical health issues at work (Table 1), especially during periods when they had to depend entirely on the platform. For some drivers who defend their profession by organizing themselves in trade unions, the response to Uber's structure is through individual and collective resistance.

Resistance as agency

Resistance to Uber structure's managerial algorithmic communication is an important form of agency enacted by VTC drivers through different communication strategies, both on and outside the platform. On-platform strategies are few and include insistence by email or telephone to request a change of work decision, and disconnections from the app to protect one's health and quality of life. Outside platform strategies include the use of online driver forums, messaging apps, and social media to exchange work information to counteract Uber's structural machine and human decisions. Physical encounters, such as union meetings, protests, media releases, blockades of Uber premises, and the development of a cooperative platform, are also part of these strategies and aim to put pressure on Uber and regain control of driver's jobs.

On platform strategies

Human assistants to the Uber structure's managerial algorithmic communication are solicited in the event of an unmanageable problem. The effectiveness of these agents is contested by the participants insofar as they do not give decisive answers to requests. Their access is only possible after several incentive attempts, as Soufiane pointed out: “It's only a system: “Hello we'll get back to you”, It's only the algorithms unless you insist…”. The drivers find themselves alone in front of a “wall” platform without an interlocutor capable of solving their problems. Nathan said:

We always deal with intermediaries between us and the decision-makers, even when we meet certain people whose role is precisely to establish communication between drivers and the head office, we are told “I have no decision-making power. I'm going to pass this on to headquarters”. And there are even people representing the platform in France who have been responding for months: “It's not us who decide, it's decided at the headquarters in California”. Unfortunately, it's always very complicated.

Nathan's account highlights the communication challenges with Uber, even when there are meetings between his association and Uber representatives through the mediation of political figures. The decision-makers are invisible and unknown, which reinforces the drivers' feeling of isolation. Thus, to avoid going through this ineffective process, some drivers learned to quickly report information on the app in the event of a problem with a client to avoid automatic suspensions or unfavorable human decisions. Youssef shared:

It is very frustrating when the people who answer you don't understand your work. Usually, they're people from the Maghreb, they only send you a message without fixing the problem. But if the problem becomes dangerous, I start sending messages repeatedly saying that I'll file a complaint because I was threatened by a racist client. The thing is that Uber penalizes us, so you have to always do more than the client to protect yourself.

Youssef, who has been working for Uber for years, resists a work environment where communication requires multiple efforts from drivers, who sometimes dramatize the situation to attract the attention of the platform. The latter also requires proof in the event of an appeal to its decisions, which are often favorable to the clients according to the participants. Soumaya noted:

At the beginning, I used to wait until the end of the day to send my request. Plus, I wasn't taking screenshots, in fact, I was not protecting myself, so in general, it was rather a negative decision. Then, I understood that I had to react immediately and at the limit, take photos, screenshots, it's the same… And I had to stop taking rides until my problem was solved with Uber.

Both Youssef and Soumaya recount a working relationship based on a lack of trust, which complicates their working conditions and adds to their workload as they are required to constantly collect proof in case of accusation. By understanding the managerial workings of the Uber platform and how it affects their occupational health, some drivers develop disconnection strategies deployed to resist tempting offers such as mark-up bonuses or reduced commission rates. Hicham said:

I'm for the law of the weekend! I like to be with my friends, my family. It is priceless. I can lose turnover, but my health is priceless. I really discovered that I was losing because of the simple things I did not have like having a good weekend with my friends, time with my family. This is something that was not possible for me two years ago. Now it's out of the question to work on weekends.

Hicham highlights the incompatibility between working for Uber and protecting his occupational health. Disconnection, especially during the weekend, is a form of resistance to the grip of the platform. This strategy is little observed among participants like the collective disconnection strategy, which consists of choosing key hours to disconnect in order to exert pressure on Uber. The heterogeneity of the professional group of VTC drivers makes it difficult for them to unite and agree on these strategies, especially since Uber is increasing its bonus offers in these periods to encourage work. Therefore, most of the resistance strategies are observed outside the platform, on the one hand because they're more visible, and on the other hand because several categories of drivers and actors of society participate in it.

Outside platform strategies

There are many online forums and social media groups that drivers use to get information or seek advice in the event of difficulty or disagreement with Uber. The use of these digital spaces is daily and extends to discussions that concern the entire profession. Coralie explains how she ceased her apoliticism when she started following the activities of a trade unionist on social media whose work has been about resisting the hegemony of Uber through political actions and lobbying. She shared:

I heard of Bassim [a trade unionist] on Facebook. I followed all his lives, so I decided to join his union, although I don't agree with all his ideas. But he is a great person, he has done a lot for us already, he makes things happen, unlike other unions. His union was the first to be received by the Ministry of Finance. So Bassim is not our savior but almost because he believes in us.

Like Coralie, some participants choose to be part of this union that attracts attention through its actions, which are constantly communicated on social media. Participating in these conversations and extending discussions also takes an asynchronous form through the sharing of thoughts on online forums, for example. Yasser noted:

What interests me in this forum is how to bring back reflections. I try, for example, to post about a topic and to end my text with a question mark to push people to think and to react. I know that Bassim is not on the forum, but he reads it because he would usually pick up topics we discussed and develop them in his videos. For example, I posted a text about Uber this morning and he took it and posted it on his Facebook page.

Yasser highlights the complementarity between the different online forms of informative or intellectual communication about the profession of drivers and resistance to its uberization10. However, the use of social media is not always the right solution to gain access to information or debate due to the large number of users and trolls. Some participants even evoke the negative atmosphere that characterizes these spaces, as Mohamed mentioned:

On the Facebook group, I see many people complaining, it's tiring, it's becoming a depressing group. I'm anti-depressed, it makes me angry feeling depressed. I'm going to get out of these groups soon. People are polluting it. I prefer to be with colleagues of mine whom I've known for a long time. We talk, we laugh, we have a coffee, we see each other outside of the context of work, it feels good, we discuss real topics.

Mohamed, like some other participants, targets specific people to talk about his work outside the workplace and online spaces for work communication, which requires a certain knowledge of whom to contact in the case of the need for information or just to express oneself. Nonetheless, the work of Uber drivers is characterized by urgency and variety of situations, making it impossible to wait for physical meetings to solve issues. Messaging apps, especially closed groups, are therefore considered safer and more credible for sharing information. For instance, Youssef recalled using a communication group on WhatsApp where he discusses his labor court case against Uber:

We have a WhatsApp group where we only talk about our Labor Court files. This is how we follow our procedures because the union takes care of our files and puts us in touch with the law firm that defends us against Uber.

By attacking Uber through Labor Court cases, Youssef and other participants take a major step in resisting this platform through legal means. In fact, several interviewees mention the word “fight” when recounting their relationship with Uber. Resistive strategies do not stop there, especially since the legal procedures in France take several years. Uber drivers who are organized through unions take part in protests to publicize their cases. Badr described his experience:

It was the first time that I protested, that I went to gatherings, and I saw that it allowed me to meet other professional drivers in the same situation, to see that I was not an isolated case, that there were others who think like me.

Badr highlights the importance of collectively and publicly defending the driving profession and how this commitment generates a feeling of solidarity. Unionized Uber drivers also discuss key dates to block the platform's premises, as explained by the trade unionist Kadir:

We had a hard time having negotiations with Uber for years, there were never official appointments. We were given appointments in offices they had rented for a day, but it was never official. Now they are opening their doors to negotiations because they are under pressure. There are drivers who are blocking their premises, so that is putting pressure on them. They are also under pressure because we go through other channels and legal procedures. It weakens them. You can see in the press that they are singled out everywhere.

Kadir underscores a set of factors likely to change the balance of power between Uber and drivers. However, it is difficult to achieve such a goal as long as the platform remains an opaque object structured by an algorithmic communication responsible for managing users. A group of unionized drivers understood this reality and chose to invest in a more strategic resistive project. The development of a cooperative platform named “Maze” illustrates a long process of transforming occupational suffering into alternative change by designing an organizational model structured by democratic and participatory communication. Bassim, who is the president and founder of “Maze” explained:

The goal of the cooperative is that we are shareholders of our platform and that if tomorrow we generate a turnover more profitable, we are ourselves investors in our future. We could not depend on Tesla and other companies. We could even buy autonomous cars and develop our own company which would be a transport company. I would like to redistribute this wealth…

Overall, Uber drivers took diverse counteracting and creative strategies from online forum discussions and debates to start legal proceedings against Uber, and win them, to create their own cooperative platform. However, the fight is far from being won as long as Uber's structure is still operating without effective constraints, stemming in particular from public policies. The discussion of the results will expand on the analysis of how the Uber structure's managerial algorithmic communication continues to resist the resistive communication strategies of the drivers.

Discussion

Asymmetric information and algorithmic governance have been identified as key elements defining Uber's structure and causing occupational risks and a lack of social protection for drivers (MacEachen et al., 2018; Cefaliello and Inversi, 2022; Cherry, 2022). Further, Koutsimpogiorgos et al. (2020) argued that the future of online platforms such as Uber will be determined by political choices that are under constant pressure from Uber's lobbying (Collier et al., 2018; Brugière and Nicot, 2019). Previous studies have explored the asymmetric balance of power in gig platforms (Calo and Rosenblat, 2017; Stark and Pais, 2020); however, research linking Uber's algorithmic control through managerial communication and the occupational health of drivers remains missing. Building on the narratives of Uber drivers, this article analyzes Uber structure's managerial algorithmic communication through daily experience of work and the counteracting communicative strategies enacted to resist these limitations that are impacting the health of workers. A lack of algorithmic regulation and the French government's support of Uber legitimatize algorithmic management enacted through asymmetric information and communication techniques, like cancellation rate, client assessment, price increase, etc., which encourage hyperconnection and lead to occupational hazards.

Studies on gig workers' occupational health have increased in the past few years (Apouey et al., 2020; Cefaliello and Inversi, 2022) as questions around the legal status of workers (Azaïs et al., 2017) have achieved positive results, in particular, the recognition of platforms' drivers and deliverers as employees, and not independent contractors (Le Goff, 2023). However, gig workers are still prevented from health benefits (Bajwa et al., 2018), and debates over the presumption of employment are becoming politicized. For instance, on 30th November 2022, the administrative court of Paris canceled the decision of the labor inspectorate refusing, at the request of a trade unionist of Uber drivers to control if there was dysfunctions in terms of hygiene and security (Pasquier, 2023). The labor inspectorate justified its decision by the independent status of Uber drivers, while the administrative court of Paris justified its decision by relying on a decision of the court of cassation, which dates back to 2020 and which recognizes the employment contract between Uber and a driver. Pending the resolution of these contradictory legal reasonings, the work of Uber drivers remains under the control of managerial communication delegated to algorithms and constantly spreading to other sectors of activity, which legitimizes the operation of structures similar to Uber. The agency of Uber drivers is, thus, structurally limited on the platform, compared to agency outside the platform. In both cases, driver resistance cannot change Uber's structural limitations managed by algorithmic communication as long as the algorithms are considered an object of intellectual property protected by law.

Findings revealing on-platform counteracting strategies enacted by Uber drivers highlight the autonomous learning process of users in their alienated relationship with the app resulting in resistive responses weighing on occupational health, but also seeking protection from the grip of an algorithmic structure. Despite Uber's attempts to control the political sphere and social media, the drivers' outside-platform agency is less limited as it is deployed through a multitude of channels and creative forms of resistance ranging from exchanging information on messaging apps to protesting and blocking Uber premises. The sensemaking of collective resistance strengthens the solidarity of the professional group of VTC drivers eroded by the arrival of Uber, as shown by the development of a cooperative platform named “Maze”.

Implications for health communication

Our findings highlight the impact of Uber structure's managerial algorithmic communication on drivers' occupational health. When addressing the health of gig workers in the French context, it is necessary to take into consideration the social protection system of independent contractors, which depends on their family, financial, and individual situations. Sensemaking and critical sensemaking play a key role in the structural-agency duality. Retrospective comprehension of ongoing working experience and the ability to express it in words and salient categories (Weick et al., 2005) guide the interpretation of the interaction with the app which privileges some identifies over others (Helms Mills, 2003) through its algorithmic organization. In the case of Uber drivers, participants who accept all platform orders, invest in a nice car, and offer great customer service are privileged, meaning that they're well-evaluated and sometimes given bonuses. But even when doing so, Uber drivers are always at risk of suspension because no one can escape conflicts and tensions, no matter how obedient they are and how great their performance and productivity are. By automating suspension decisions following negative feedback from clients, Uber extends the social injustice experienced by a large population of VTC drivers sought in poor areas, where many immigrants are concentrated. Thus, the social context that defines the critical sensemaking of Uber drivers' occupational health should be noted in health communication research.

Furthermore, Uber's discourse on entrepreneurship to promote the “benefits” of its structure both socially and economically has been supported by the French government of Macron, especially in this period, which is characterized by a significant movement of requalification in employment contract platform workers. For instance, the creation of the Employment Platforms Social Relations Authority (ARPE11) in 2021 to encourage “social dialog” between gig platforms and workers imposes the rule to keep the independent status for workers and to negotiate, instead, the minimum income per ride and other elements that do not constitute risks for the disappearance of gig platforms. Moreover, ARPE poses a problem of conflict of interest given that its president is a former consultant of Uber. Thus, Uber drivers face structural limitations both from the platform and the government, making their agency a fight of resistance under permanent threat. Health communication research should note that government intervention in the Uber-VTC drivers affair is biased in France and cannot easily result in protective occupational health laws for gig workers. These structural limitations push VTC drivers and other social actors (lawyers, politicians, journalists, researchers, etc.) to join cooperative projects such as “Maze” to curb the phenomenon of uberization, which risks affecting more professions and sectors of activity.

In the French context, the social protection system has been managed since the 1970s by political leaders who favor controlling or even reducing social spending (Barbier et al., 2021). French politics of the 1970s were also broadly part of an international neoliberal movement giving rise to discourses promoting individual ownership and entrepreneurship (AucoutuRier, 1996). The financial crisis of 2008 constituted a favorable context for the return of these policies illustrated, for example, by the creation of the auto-entrepreneur scheme to deal with the rise in unemployment (Abdelnour, 2014). Gig platforms such as Uber provide, according to these politicians, rapid responses to problems of unemployment, integration, and social exclusion regardless of the hard-working conditions and the lack of health protection. Thus, it is not insignificant to observe similar occupational hazards between gig workers in several northern and southern countries, nor it is random to remark an international unionization movement of gig workers (Freyssinet, 2019). Some studies even compare the agency of gig workers and Taylorian factory workers' resistance in the 19th and 20th centuries by adopting a Marxist approach to the study of gig platforms (Abdelnour, 2018).

This article highlights VTC drivers' strategic agency in and outside the Uber structure, motivated by the critical sensemaking of working conditions affecting occupational health, and strengthened by a legal fight carried out by these workers and by other social actors. The connection between Weick's sensemaking and Giddens's structuration theory is demonstrated in this article through the study of a digital structure called a “platform”, and a professional group overwhelmed psychologically and physically by the technological and political transformations caused by these types of companies. Sensemaking and structure-agency theoretical frameworks complement each other in this study because structure and agency cannot exist without sensemaking and critical sensemaking. This process involves the subject adopting practices, imagining scenarios, and thinking of solutions to adapt to their relationship with algorithms, which constitutes a source of occupational suffering and resistance for these workers. As demonstrated in the findings section, resistance is also about establishing “cooperative platforms” and collaborative communication in the age of algorithmic management. Health communication research should pay attention to the possibilities within alternative platforms such as “Maze” and the structural limitations of French policies to hinder this movement.

Limitations and conclusion

There are two major methodological limitations to this study. Firstly, the lack of narratives from Uber representatives does not allow an overview of structural limitations constitutive of the platform's managerial algorithmic communication. The attempts to contact these people were doomed to failure like going twice to the premises of Uber at the Montparnasse Tower in Paris, where a very brief reception was given by an employee who assured that they would call but didn't, and in Aubervilliers, where the security agents forbid the entry of “walk-ins” and “uninvited” people. Regarding attempts to contact Uber on social media, such as LinkedIn, the requests to add some of its representatives to networks were accepted, but the messages remained unanswered. These reactions were expected because Uber is reluctant to communicate with journalists and researchers. Uber's rare media releases are well-targeted and are part of a very strategic visibility objective. The platform only chooses media that are known and consistent with its vision.

The narrative of Uber will never reveal the real algorithmic logic by which the app structures the work organization because the code of algorithms is an intellectual property protected by law. Therefore, the second limitation of this study is that it can only take an interpretive approach to the results using one qualitative method. It is important to point out that the heterogeneity of VTC drivers and their permanent flexibility made it challenging to use other qualitative methods, such as focus groups and participant and non-participant observation. However, the combination of semi-structured interviews using the life story method and a quantitative method could have brought new elements to the results, which could be a recommendation for future studies.

Uber structure's managerial algorithmic communication is an important research subject to understand the recent social transformations in France linked to the gig economy and its participation in the weakening of the French social protection system, more specifically, occupational health. The majority of VTC drivers come from socially and economically excluded backgrounds, making them a target of aggressive political and economic change. Uber's structure initiated and democratized a new work system that lacks human communication and delegates organization to algorithms. This study refers to this phenomenon of work organization as “Managerial Algorithmic Communication” and considers it responsible for the appearance of various forms of mental and physical exhaustion among VTC drivers. Throughout this article, structural limitations imposed by Uber through managerial algorithmic communication, such as automatic responses and suspension by the app, standardized information treatment by Uber's human assistants, the priority given to customer feedback, etc., create a stressful work environment likely to generate occupational suffering. Uber's structural limitations also generate resistance from the workers who make sense of the structure and deploy strategic agency to counteract it. Future studies may focus on the countermovement to uberization, such as the development of cooperative platforms defined by Scholz (2016) as democratic governance structures that integrate all or part of the organization's stakeholders (users-consumers, workers, local authorities, associations, local communities). Weick's sensemaking and Giddens's structure-agency are pertinent theoretical frameworks in the study of top-down structures, but how they can be approached in the case of “democratic” structures remains to be identified. By studying the communicative logic of participative governance and the “denumerized” spaces of deliberation in cooperative platforms, occupational health can be approached through the prism of quality of life at work instead of occupational hazards.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Conservatoire National des Arts et des Métiers. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

SE: study conception, data collection, analysis and interpretation of results, and draft manuscript preparation.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Dicen-IdF laboratory for providing the materials required for collecting and processing data. I also would like to express my gratitude to the 50 VTC drivers interviewed in this study and to Dr. Satveer Kaur-Gill for editing this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^Uber's growth during the era of its co-founder and ex-CEO Travis Kalanick was usually described as chaotic and aggressive, leading to a toxic workplace where harassment took place.

2. ^Transport vehicle with driver [Véhicule de transport avec chauffeur] is a legal status promulgated in France in 2009 under the law n°2009-888 of the development and modernization of tourist services.

3. ^In an interview granted to the French investigate online media “Mediapart” in 2016, Macron, then minister of Economy Industry and Digital, argued that Uber “recruits” in neighborhoods where the state of France has nothing to offer. He insisted that although these workers work for 60 or 70 hours per week for minimum wage, they come in with dignity because they work. Source. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OPNx6sPqkkE [Consulted on the 18/04/2023].

4. ^The Uber files: 124,000 confidential documents spanning the period between 2013 and 2017 on the intensive lobbying of Uber, made public by American and European media on 10th July 2022.

5. ^In France, the end of the XIX century marks significant progress in terms of labor law and, specifically, the occupational health of workers. The establishment of labor inspection in 1874, the regulations of hygiene standards in 1893, the foundation of liability risk in 1898, and other framework laws constituted a stable Wage Society (Castel, 1997) that articulates work and social protection. The end of the 1960s was also a key period of labor law progress. The events of May 1968, an important social movement of protests and strikes, resulted in a 35% increase in the minimum wage and other decisions in favor of workers and students called the Grenelle agreements.

6. ^In her review of Weick's book “Sensemaking in Organizations”, Czarniawska (1997) used the term “sense-breaking” to describe the break in routine, shocks, and interruptions that change the dynamics of sensemaking.

7. ^This article is an excerpt from a thesis research that is based on three hypotheses: VTC drivers' addiction at work in the app is triggered by algorithmic mechanisms structured by Uber (1); the delegation of VTC work organization to algorithms creates communication issues with the platform (2); the severity of Uber drivers' work exhaustion is influenced by a variety of sociological, individual and psychological factors (3). In this article, the main focus is on the following questions: How does Uber structure's managerial algorithmic communication with drivers influence their sensemaking? What agentic strategies of resistance were employed by drivers to address the occupational hazards they faced?

8. ^The translation from French to English resulted in modifications to these figures.

9. ^The Grande Remise meant luxury tourist car transport domain. It was replaced by the VTC status that includes all categories of professional drivers.

10. ^Uberization means an upheaval of a sector of activity by the arrival of a digital platform. In recent years, the use of this term has been associated with a process of aggressive job insecurity.

11. ^Autorité des relations sociales des plateformes d'emploi.

References

Abdelnour, S. (2014). L'auto-entrepreneur: une utopie libérale dans la société salariale. Lien social et politique. 71, 151–165. doi: 10.7202/1027211ar

Abdelnour, S., and Bernard, S. (2019). Communauté professionnelle et destin commun. Les ressorts contrastés de la mobilisation collective des chauffeurs de VTC. Terrains and Travaux. 34, 91–114. doi: 10.3917/tt.034.0091

Abdelnour, S., and Bernard, S. (2020). Faire grève hors du salariat et à distance Les pratiques protestataires des chauffeurs de VTC. Mouvements. 103, 50–61.

Adams-Prassl, A., Adams-Prassl, J., and Coyle, D. (2021). “Uber and Beyond: Policy Implications for the UK,” in The Productivity Institute Productivity Insight Paper. Available online at: https://www.productivity.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Uber-and-Beyond-with-cover-sheet-PDF.pdf (accessed April 19, 2023).

Amorim, H., and Moda, F. (2020). Work by app: algorithmic management and working conditions of Uber drivers in Brazil. Work Organ. Labour Globalisat. 14, 101–118. doi: 10.13169/workorgalaboglob.14.1.0101

Anwar, M. A., and Graham, M. (2019). Hidden transcripts of the gig economy: labour agency and the new art of resistance among African gig workers. Environm. Plann A: Econ. Space. 52, 1269–1291. doi: 10.1177/0308518X19894584

Apouey, B., Roulet, A., Solal, I., and Stabile, M. (2020). Gig workers during the COVID-19 crisis in France: financial precarity and mental wellbeing. J. Urban Health. 97, 776–795. doi: 10.1007/s11524-020-00480-4

Ashta, A., and Raimbault, S. (2009). Business perceptions of the new french regime on auto-entrepreneurship: a risk-taking step back from socialism. Cahier du CEREN. 29, 46–61.

AucoutuRier, A.-L. (1996). La construction des objectifs d'une mesure de politique d'emploi: l'histoire de l'aide aux chômeurs créateurs d'entreprise. Paris: Centre de recherche pour l'étude et l'observation des conditions de vie.

Azaïs, C., Dieuaide, P., and Kesselman, D. (2017). Employment grey zone, employer power and public space: an illustration from uber case. Indust. Relat. 72, 409-610. doi: 10.7202/1041092ar

Bajwa, U., Gastaldo, D., Di Ruggiero, E., and Knorr, L. (2018). The health of workers in the global gig economy. Global Health. 14, 1–4. doi: 10.1186/s12992-018-0444-8

Barbier, J.-C., Zemmour, M., and Théret, B. (2021). Le système français de protection sociale. Paris: La Découverte.

Bargain, G. (2018). Quel droit du travail à l'ère des plateformes numériques Lien Social et Politiques. 81, 21–40. doi: 10.7202/1056302ar

Barratt, T., Goods, C., and Veen, A. (2020). ‘I'm my own boss...': Active intermediation and ‘entrepreneurial' worker agency in the Australian gig-economy. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space. 52, 1643–1661. doi: 10.1177/0308518X20914346

Bell, R. L., and Martin, J. (2008). The promise of managerial communication as a field of research. Int. J. Busin. Public Administrat. 5, 125–142.

Bell, R. L., and Martin, J. (2014). Managerial Communication for Organizational Development. New York: Business Expert Press.

Bourdieu, P. (1986). L'illusion biographique. Actes de la recherche en sciences sociales. 62–63, 69–72. doi: 10.3406/arss.1986.2317

Broughton, A., Gloster, R., Marvell, R., Green, M., and Martin, A. (2018). The Experiences of Individuals in the Gig Economy. United Kingdom: Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (United Kingdom). Available online at: https://apo.org.au/node/220126 (accessed January 31, 2023).

Brugière, A., and Nicot, A.-M. (2019). À la recherche de nouvelles régulations sociales, entre conflits, mobilisations, lobbying et réglementation. Chronique Internationale de l'IRES. 168, 139–154. doi: 10.3917/chii.168.0139

Calo, R., and Rosenblat, A. (2017). The taking economy: uber, information, and power. Columbia Law Rev. 117, 1623–1690. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.2929643

Cefaliello, A., and Inversi, C. (2022). “Chapter 3: The Impact of the Gig-Economy on Occupational Health and Safety: Just an Occupation hazard?,” in A Research Agenda for the Gig Economy and Society, eds. Y. De Stefano, I. Durri, C. Stylogiannis, and M. Wouters. Massachusetts: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Cherry, M. A. (2022). “Employment Status for “Essential Workers”: The Case for Gig Worker Parity,” in Loyola of Los Angeles Law Review. Available online at: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4006595 (accessed April 19, 2023).

Collier, R.-B., Dubal, V., and Carter, C. (2018). Disrupting regulation, regulating disruption: the politics of uber in the United States. Perspect. Polit. 19, 919–937. doi: 10.1017/S1537592718001093

Czarniawska, B. (1997). Sensemaking in organizations by Karl E. Scand. J. Manage. 13, 113–116. doi: 10.1016/S0956-5221(97)86666-3

Demazière, D., and Gadea, C. (2009). Sociologie des groupes professionnels. Paris: La Découverte. doi: 10.3917/dec.demaz.2010.01

Dowding, K. (2008). Agency and structure: interpreting power relationships. J. Power. 1, 21–36. doi: 10.1080/17540290801943380

Freyssinet, J. (2019). Les syndicats et les plateformes. Chronique Internationale de l'IRES. 165, 34–46. doi: 10.3917/chii.165.0034

Gandhi, A., Hidayanto, A. N., Sucahyo, Y. G., and Ruldeviyani, Y. (2018). “Exploring people's intention to become platform-based gig workers: an empirical qualitative study,” in International Conference on Information Technology Systems and Innovation. Bandung – Indonesia, p. 266–271.

Giddens, A. (1984). The Constitution of Society: Outline of the Theory of Structuration. Oakland, CA: University of California Press.

Hays, S. (1994). Structure and agency and the sticky problem of culture. Sociol. Theory. 12, 57–72. doi: 10.2307/202035

Helms Mills, J., Thurlow, A., and Mills, A. J. (2010). Making sense of sensemaking: the critical sensemaking approach. Qual. Res. Organizat. 5, 182–195. doi: 10.1108/17465641011068857

Karriker, J. H., Hartman, N. S., Cavazotte, F., and Grubb, I. I. I. W. L. (2021). Identity in the gig economy: affect and agency. J. Organizat. Psychol. 21, 146–159. doi: 10.33423/jop.v21i2.4200

Koutsimpogiorgos, N., Slageren, J., Herrmann, A., and Frenken, K. (2020). Conceptualizing the gig economy and its regulatory problems. Policy Int12, 525–545. doi: 10.1002/poi3.237

MacEachen, E., Reid Musson, E., Bartel, E., Carriere, J., Meyer, S. B., Varatharajan, S., et al. (2018). The sharing economy: hazards of being an uber driver. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 75, A494.3–A495. doi: 10.1136/oemed-2018-ICOHabstracts.1407

Martini, J.-D. (2017). International regulatory entrepreneurship: Uber's battle with regulators in France. San Diego Int. Law J. 19, 127–160.

Matherne, B.-P., and O'Toole, J. (2017). Uber: aggressive management for growth. Case J. 13, 561–586. doi: 10.1108/TCJ-10-2015-0062

Möhlmann, M., Alves de Lima Salge, C., and Marabelli, M. (2023). Algorithm sensemaking: how platform workers make sense of algorithmic management. J. Assoc. Inform. Syst. 24, 35–64. doi: 10.17705/1jais.00774

Pasquier, T. (2023). Travailleurs des plateformes: l'inspection du travail est compétente pour mettre en œuvre son contrôle. Bulletin Joly Travail. 2, 30–35.

Ravenelle, A. J. (2019). Hustle and Gig: Struggling and Surviving in the Sharing Economy. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Rosell Llorens, M. (2015). “De-mediation processes and their impact on legal ordering – lessons learned from uber conflict,” in Regulating Smart Cities, Barcelona: Huygens Editorial, eds J. Balcells, A. M. Delgado, M. Fiori, C. Marsan, I. Peña-López, M. J. Pifarré, and M. Vilasau (Barcelona: Universitat Oberta de Catalunya).

Rosenblat, A., and Stark, L. (2016). Algorithmic labor and information asymmetries: a case study of Uber's drivers. Int. J. Communi. 10, 3758–3784. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.2686227

Scholz, T. (2016). Platform Cooperativism: Challenging the corporate economy. New York: Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung. Available online at: https://rosalux.nyc/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/RLS-NYC_platformcoop.pdf (accessed August 23, 2023).

Schwinn, T. (2007). “Individual and collective agency,” in The Sage Handbook of Social Science Methodology, eds. W. Outhwaite, and S. Turner. London: Sage Publications, 302–315.

Seaborn, K., and Fels, D. (2015). Gamification in theory and action: a survey. Int. J. Human-Comp. Stud. 74, 14–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhcs.2014.09.006

Stark, D., and Pais, I. (2020). Algorithmic management in the platform economy. Sociologia. 14, 47–72. doi: 10.6092/issn.1971-8853/12221

Stewart, A., and McCrystal, S. (2019). Labour regulation and the great divide: does the gig economy require a new category of worker? Austral. J. Labour Law. 32, 4–22.

Suriyamongkol, C. (2016). The Influence of Sales Promotion on Thai Customer Purchase Decision for Transportation Service Application: A Case Study of Grab and Uber in Thailand. Bangkok: Thammasat University.

Taylor, J. R., and Robichaud, D. (2004). Finding the organization in the communication: discourse as action and sensemaking. Organization 11, 395–413. doi: 10.1177/1350508404041999