- 1Department of Business Communication, Vienna University of Business and Economics, Vienna, Austria

- 2School of Communication and Arts, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, QLD, Australia

While in the not-too-distant past, tattoos were often perceived as representing non-conformity or even deviance, tattoos now increasingly transcend class, gender, and age boundaries and are more acceptable than ever. Tattoos are created by artists and are an interpretation of a story that the client wants to tell, re-created in interpersonal communication situations—before, during, and after the actual tattooing. The project at hand conceptualizes and critically examines the ways in which tattoos alter people's sense of being not only in a semiotic way but also in a conversational way. Our guiding research question is how (much) tattooed images, ornaments, and symbols of nature (re)create the eco-cultural identity of the person wearing it and what role storytelling plays in restoring human–nature relationships. The insights were gained with a series of explorative interviews with (N =) 12 tattoo artists in Oceania (Australia and New Zealand) and Europe (Germany, Austria, and France), analyzed with an inductive categorization supported by QCAmap. The findings show that tattoos are both a device and signifier and a storytelling method. Bodies are described as landscapes where individual stories are carved out through a process of tattooing and ritual interactions and conversations tattooed bodies have with others. Tattoos have the potential to re-story the body and shape it in ways that create meaning for the tattooer, the wearer, and the society, and to create eco-cultural identities, thus regenerating or restoring human–nature relationships. This project opens a new field for communication research that helps to strengthen a conversational understanding of communication beyond the ritual perspective. The conceptualization of tattooing as a conversational process where meaning is created, common beliefs are (re)produced, new norms are cultivated, and meaningful human–nature relationships are forged stimulates further research studying other rituals and their potential to communicatively re-create a more sustainable society.

Theoretical background

Tattoos in literature: reclaiming the self

The existing literature on tattoos in the context of communication, messaging, and identity construction (see Krtalić et al., 2021) has a strong focus on the meaning and interpretations of tattoos which is studied from a visual communication perspective (Wymann, 2010; Alter-Muri, 2020), for example, as impression management or performance, or a sociological perspective asking for the perception of bodies in the society (Fenske, 2007; Doss and Ebesu Hubbard, 2009; Walzer and Sanjurjo, 2016; Dann and Callaghan, 2019). Specifically, tattoo literature has analyzed deviance (Kosut, 2006), motivations (Lane, 2014), reclaiming the self (Reid-de Jong and Bruce, 2020), gender (Mifflin, 2013; Nash, 2018; Dann and Callaghan, 2019), and the commodification of the body (Craighead, 2011).

From a psychological perspective, studies and theoretical conceptualizations look at identity construction with or through tattoos. This body of research is sectioned into the literature on personal identity building on the one hand (i.e., Kosut, 2000) and group identity, culture, and trends on the other hand (DeMello, 1993; Mensah et al., 2018). This is a starting point for our question of how human care for nature is expressed in tattoos and what role tattoos and the process of tattooing play in eco-cultural identity building—if we look at it from a communication perspective.

Most of the tattoo-related literature around identity building focuses on self-presentation, the creation of self-identity, or questions around impressions that the wearer of a tattoo—strategically—wants to create. Goffman (1976) offered a useful theoretical concept not only to understand people's impression management—but also to better understand rituals (practices, procedures for interaction, and practices following/modifying rules) embedding individuals in society. This second aspect goes hand in hand with critical and conversational approaches in communication studies, where communication is less understood as a transfer of information or a certain message, but more so as an organizing principle in conversations and constructivist sense—and meaning-making process in conversations (Weick, 1988, 1995; Honneth and Joas, 1991; Weder and Milstein, 2021). While Goffman speaks of two different stages, the front stage and the backstage, from our communication perspective, the most interesting aspect here is that both stages are embedded within and “created” or “reproduced” by social and thus communicative interactions and conversations.

Goffman's theoretical approach has been applied within tattoo literature, mostly based on his work Stigma which is used to understand tattoos as socially symbolic through moral careers (Goffman, 1976; Phelan and Hunt, 1998). But again, the tattooed body is here described as not just situated within a vacuum of individual choice, but as ritualized and constructed through social conventions and interactions on both the front and the backstage. Bodies are thus an “alterable prop that can be shaped backstage to enable the successful management of impressions on the frontstage”. These bodies are then a site of social inscription, presenting a social billboard (Young and Atkinson, 2001). However, these billboards and the meanings conveyed are constructed through social interaction, rather than direct information and communication processes (Goffman, 1959). Within the dramaturgical approach, the communicative value of tattoos therefore lies beyond the rather static visual representation. It rather exists within the narratives and in the interactions and conversations surrounding them.

Tattooing as a ritual, tattoos as communication

Limited studies have been done from a communication perspective focusing on tattoos as a narrative device (Patterson, 2017), in which the tattoo is situated within a larger storytelling process. The communicative role of tattoos is only just starting to be understood and there is limited understanding of the meaning-making process (Krtalić et al., 2021), unless looked at from an individual's perspective (Doss and Ebesu Hubbard, 2009).

With the explorative study at hand, we expand on these notions specifically from an environmental and sustainability communication perspective. The environmental and sustainability communication theoretical backdrop for our research considers sustainability as a normative principle, the principle of regeneration guiding individual action (Weder, 2022). Therefore, we are concerned with how tattoos as a form of communication, and the storytelling and meaning-making which occurs in relation to them, might express a particular personal relationship with nature and the environment. In particular, we consider the notion of communicating care for the environment (sustainability) as a key indicator of a nature-centric human–nature relationship and eco-cultural identity (Milstein, 2008). In the context of environmental tourism, Milstein considered that the expression of care is often mediated by the placement of natural beings within humanized framing (Milstein, 2008, p. 177). Moreover, we consider the notion of place as a means of centering attention in relation to the environment (Carbaugh and Cerulli, 2013). Carbaugh and Cerulli (2013) suggest that our culturally and personally specific experiences of various places inform the ways we communicate about our environment. Simultaneously, communication itself may be formative in shaping an individual sense of place. Thus, we need a better understanding of tattoos and tattooing as a ritual and the communication processes that are part of this ritual.

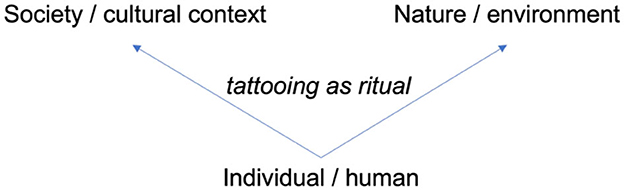

Therefore, existing literature on the role of tattoos in identity building has been linked with a critical, social-constructivist approach to communication. Here, communication is understood as all processes of sense- and meaning-making, as an action that organizes meaning (Taylor and Robichaud, 2004), as a search for understanding and relevance, and as a way of establishing common ground, as well as a means of connecting with another's experience (Arnoldi, 2010); this is further explored in everyday or workplace-related conversations (i.e., Sandberg and Tsoukas, 2020) or in visual and art-related communication situations, where the communication between artworks and viewers are conceptualized as conversation (Grice, 1975; Dolese et al., 2014; Dolese and Kozbelt, 2020). With these communication approaches in mind, we first conceptualize tattooing as a communication process or ritual (Cheal, 1992; Rothenbuhler, 2006; Carey, 2007) that is “realized” or emphasized by conversations—here: around the tattoo. This ritual may embed individuals not only in society or a specific cultural context (Carey, 1989, 1997; or related to tattoos: Kosut, 2000) but also embeds individuals in nature or links individuals to nature and the non-human world (see Figure 1).

If tattooing itself is a conversational ritual, then linking experiences before, during, and after the tattooing is also a conversational ritual that bridges time, space, cultural, and social contexts.

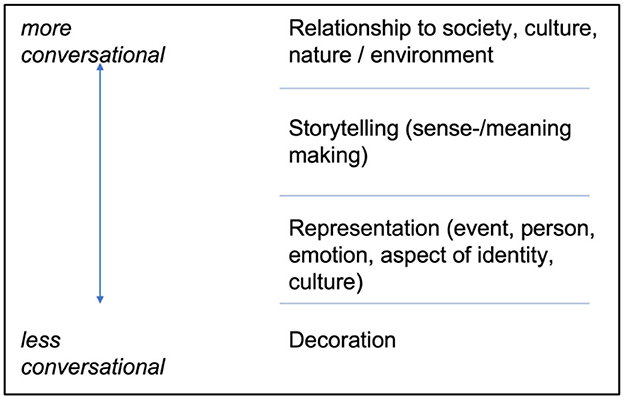

Second, with this approach to tattooing as a conversational ritual, tattoos can be understood as a form of communication as much as wearing the tattoo is also a communication and therefore a sense- and meaning-making process itself. From an analytical point of view, this approach allows us to explore not only how much human–nature relationships are expressed in a tattoo (symbol, ornament, and image) but how much they are expressed in the stories that are told around a specific tattoo. For the project at hand, we do not focus on tattoos themselves and categorize them as nature-related or not; instead, we look at the conversational ritual and therefore communicative character of tattoos and the stories that are told related to a specific tattoo. Complementing the literature on tattoos and their role in interactions and cultures and a social-constructivist understanding of communication as sense- and meaning-making through storytelling (see above), we developed the following framework to differentiate the various “conversational levels” or different degrees of the “communicative character” of tattoos (see Figure 2).

These levels are further described in the following paragraphs:

1. In the very first stage, with a limited conversational character, tattoos can be decorative elements. These tattoos have less communication potential and less potential to embed the wearer in nature through tattoo-related conversations due to their abstract nature. An example would be the following tattoo, which belongs to the identity of the wearer similar to being muscular or belonging to a specific group.

Source: private.

2. In the second stage, a flower such as a rose can be a representation of love and a lion can stand for strength or a certain aspect of identity, such as masculinity or power. The common symbolic common sense at least in a specific cultural context gives stability and validation from other people for whom the lion also stands for stability. On this level, the tattoo has foremost a representative character and still less potential to initiate conversations where eco-cultural identity and a nature-centered human–nature relationship are enforced. An example would be the following:

Source: A11 (private).

3. In the third stage, active storytelling comes into play; at this stage, the creation of a narrative around or related to the tattoo includes the potential re-creation of a specific meaning in a conversation. While Dervin (1999) or Klein et al. (2006) look at sensemaking processes in an individual model (framing), often applied to an external context or activity (nature or how nature is represented in the media, for example), Weick focuses on collective organization and sensemaking processes (Weick et al., 2005).

Narratives are a way that humans make sense of the world around them, thus with stories around or related to the tattoos, the wearer of the tattoo(s) can potentially reinvent themselves (Mitchell, 2006; Weder and Milstein, 2021: men as storytelling animal). In contrast to the second stage, looking at the stories related to a tattoo rather than the tattoo itself, the representative character loses its stability; instead, there is an openness for collaborative meaning- and sensemaking in every conversation and in every story that is told in a potentially different way depending on whom the wearer of the tattoo is talking to. An example would be the kangaroo which not only stands for a connection to Australia but also for being embedded in nature and the flow of life, because a kangaroo is one of the few animals that cannot walk backward.

Source: private.

4. In the fourth stage, tattoos become part of nature, that is, imitating nature. While with a decorative or representative tattoo, people rather want to demarcate themselves from animals or the “normal”, bodies are individualized, and it is a medium of communication and expression, and in this fourth stage, tattoos are something different. They create what we conceptualize as an eco-cultural identity at the beginning of the theory section. This includes the “idea of being tattooed” and an artistic way of being part of nature.

One example would be a flower that replaces a woman's breast after a mastectomy which creates the relation to “mother nature” in a different, not only “representative”, way. Compared to the third stage, there is no specific meaning that is negotiated in conversations, nor any identity that is (socially) constructed. This dimension goes beyond the idea of identity creation into nature consciousness and the individual relationship to nature, the connection. The tattoo then expresses eco-centrism and is restorative itself , and it is an expression of our care for nature or elements of the non-human world.

Source: A12, private.

To summarize: while most tattoo-related literature analyses discuss tattoos as decoration or representation (i.e., of a specific event, emotion, aspect of identity or culture; stages 1 and 2), we bring in a specifically environmental communication perspective on eco-cultural identity creation in conversations around a tattoo and in the process of tattooing as a conversational ritual (stages 3 and 4). With an explorative series of interviews presented in the following sections of this study, we explore how individual relationships to nature and non-human environments are (re)produced in these conversations.

Project/methodology

Existing studies on tattoos, visual representations, identity, or tattoo culture mostly work with semiotic or hermeneutic techniques to decode the symbols, and semiotics of a specific image, symbol, or ornament. Ethnographic techniques go one step further and enable the researcher to include semantics and the meaning of a specific image, symbol, or ornament, while every “symbol” includes a specific meaning for the wearer.

To explore tattoos and human–nature relationships created in and through tattooing, the project was conceptualized around a series of explorative, in-depth interviews with tattoo artists with various cultural backgrounds in Australia, New Zealand, and selected artists in Europe (Germany, Austria, and France). The series of interviews was part of a larger project researching new, emerging communicator roles in the area of environment, climate change, and sustainability communication.1 The tattoo artists were selected through personal contacts of the research team. From the first set of five interviewees, snowballing was applied to generate a larger sample. The selected participants were interviewed face-to-face between December 2022 and February 2023. The interview guideline addressed the following dimensions to capture the whole process of tattooing as ritual and meaning-making processes before, during, and after the tattooing: (1) What are defining moments for the tattoo artists to tattoo in the way they do—and with the tools and equipment they use; (2) what are the most common nature-related images, symbols, and ornaments that are chosen by their clients; (3) when is meaning created: before, during, or after the tattooing; (4) what are the stories that are told related to a specific tattoo, what of these stories was especially meaningful for the artist and why; and (5) what influences the meaning-making and the story that is told. On purpose, we did not specifically ask the interviewees for their definition of nature or sustainability; instead, we focused on how the interviewees narrated their individual tattooing and the motives they tattooed.

The conceptualization of sensemaking further described in the section above has worked as a guidepost for our empirical research. Sensemaking includes all “ways that people make sense of things” but focuses on different units of analysis from a methodological point of view, from individual to collective actors, and internal or external representations of meaning. While Weick's focus has been rather organizational (collective) activity, Dervin (1992, 1999), for example, has an individual, hermeneutic approach not only on an individual's situation but also on their internalized subjective experience of this situation. We follow his qualitative and, therefore, explorative approach in the following way: Next to individual notes taken by the interviewer, the interviews were recorded and literally transcribed (Mayring and Fenzl, 2014). The researchers used an innovative form of qualitative content analysis (two-step categorization) to explore the data (Mayring, 2014; Mayring and Fenzl, 2019). Based on the semi-structured character of the interviews and the conversational approach in the interview situations, it was appropriate to use a content analytical technique of inductive category formation to answer the research questions. In this procedure of analysis, we developed categories inductively based on the textual material along the selection criteria that have been determined by concepts and theoretical grounds described in the theory section above; here, we worked with a low level of abstraction when phrasing the categories (Mayring, 2014). We defined word sequences and phrases as the smallest component in the so-called “context unit” (single interview) that was coded as a clear-meaning component (seme) in the text. The text analysis was performed (with multiple coding) in the online tool, www.QCAmap.org (Fenzl and Mayring, 2017), which enables, structures, and organizes the inductive development of categories. Regarding the communicative or conversational level of the tattoos (see Figure 2 again), we used deductive categorization and used the four identified levels as meta-categories. It is important to mention that the frequencies of certain categories (for example, the mentioning of flowers as the most common tattooed symbol of nature) do not reflect a ranking of what was important to each interviewee. Instead, the frequencies were understood as an indicator of the weighting across all cases.

Findings

The findings of the five guiding questions posed in the explorative interviews conducted with tattoo artists are presented in the following.

Defining moments for the ritual of tattooing

We were first concerned with ascertaining the crucial moments that led the artists to the development of their specific style. Seven categories were identified as influences to differing degrees in the responses. Interestingly, in all but two of the interviews, some reference was made to an element of opportunity or coincidence that drove their decision to tattoo, be their style largely focused on nature-related subject matter or otherwise. For instance, interviewee 6 suggested that her pathway into tattooing occurred largely because “it was just better than anything else”, and her style developed over time because she had merely “been in one place long enough” that she became “known for it” and sought out for it.

With an acknowledgment of the fact that tattooing is an art form, individuals' artistic talent and passion for art were also featured heavily in conversations as a crucial influence for decisions to tattoo. Interviewees 1, 5, and 7 explicitly discussed that their pathway from studies or careers in visual art and illustration directly translated to their tattoo style, be that illustrative, realistic, or otherwise.

Interestingly, half of the interviewees also expressed a specific passion for nature as a guiding point of influence for the development of their tattoo style. While interviewee 1 expressed she “love, love, love[s] birds”, interviewee 7 described nature as something she has “always been close to”. Interviewee 11 described her journey in the following way:

“I grew up in the middle of nature. A beautiful old farmhouse in the north of Germany. Exactly were the kingfisher breeds in the shire. My love to nature was there from the beginning. And I always wanted to tattoo – and I wanted to tattoo exactly where I am, in the middle of nature, on the farm, in the middle of nature”.

It can be said that for many of the artists spoken with, some intrinsic level of care for the environment, or closeness with nature, is formative to decision-making surrounding stylistic choices in their practice. Other themes such as the desire to share art with others, the increased social acceptance of tattooing, and passion for tattooing more generally featured less frequently in the responses, suggesting they were overall less influential to the sample of artists. Overall, however, the interview subjects typically expressed similar moments and influences as being significant to the development of their personal artistic style, despite the vast differences in their personal practices.

Common nature-related symbols and ornaments

We then turn to the question of which nature-related symbols and ornaments feature most commonly in the images tattooed by the interviewed artists. Although a range of symbols were identified by the interviewees, over half noted that botanicals such as flowers, plants, and leaves were the nature-related subject matter they most frequently tattooed. Both interviewees 7 and 9 described “botanicals” as a significant part of their practice. More specifically, and likely informed by the Australian context in which most of the interviews took place, interviewee 7 explained that native Australian plants and flowers such as “gum nut flowers” make up a significant proportion of her practice in the same way that an artist from Germany pointed to typical birds or even blades of grass and herbs that grow specifically in the north of Germany. Overwhelmingly, flowers were described as a common ornament, with six interviewees noting them as the most frequent nature-related symbols tattooed by them. Interestingly, interviewee 5 suggested that place-based flowers were often requested by clients, with many wanting flowers “connected to home”, other memories or people, or serving as a reminder of a location where they have spent time. In this way, it can be said that the floral tattoos acted as a symbolic anchor for individuals to a particular lived experience.

The interviewees also identified animals such as birds, wolves, and foxes as the most common nature-related icons they tattooed. Snakes, insects, other wild cats, and smaller mammals all were mentioned by individual interviewees as common nature-related icons in their tattooing practice. Again, interviewee 1 specifically described native Australian birds such as “black cockatoos” and “kookaburras” as a large part of her tattoo practice, similar to smaller birds such as robins which people relate to their childhood in Austria or the “pirol” (oriole or lark) in France.

“The kookaburra is probably one of the most representative birds for Australia. It is an icon – much more as the cockatoo or other, much more beautiful, parrots. I'm often asked to ‘iconize' the bird even more, adding some features to make it more representative” (interviewee 11).

It is thus apparent that the geographical location where the interviewees got tattoos was important to the choices made by their clientele; clients wishing to receive a tattoo of an icon of the Australian environment naturally express a particular experience of place in making this decision (see the kangaroo example in the theory section).

Fluidity of sense- and meaning-making

Interviewees were then questioned on the point at which meaning-making typically occurs; be that before, during, or after the tattooing occurs. Most respondents suggested that some degree of meaning-making occurs in the interactions between the artist and client during the process of collaboratively designing a tattoo piece. Interviewee 5 noted that she often includes additional elements in her designs to enhance meaning “without [clients] even realizing” based on the stories told by them. Furthermore, interviewee 9 explained that given tattoo appointments place artist and client “together for a long time”, it is natural for storytelling surrounding the meaning of a piece to occur during the tattoo process. However, interviewees 5 and 9 acknowledged that the now typically online process of booking a tattoo for some artists, and consequent lack of consultation, in some way restricts the capacity for artistic collaboration and dynamic meaning-making to occur in the designing of the tattoo itself. More unusually, interviewee 2 noted that he often deliberately avoids enquiring about a tattoo's potential meaning to a client to avoid triggering emotion which may disrupt the tattoo process.

The tattoo artists also noted that some clients come into the tattoo process with the meaning fully constructed as opposed to meaning-making occurring during conversations. Most interviewees agreed that clients at least come in with a symbol that “reminds them of a certain moment”; interviewee 11 describes this in the following way:

“The animals that I'm asked to tattoo are mostly related to the childhood of the clients – or at least a certain experience in the childhood. Birds are often chosen with a more specific meaning, for example, one of my clients lost her child and the ‘flying bird' that we chose for the tattoo reminds her of her dead child. Often animals are chosen for lost family members.”

In this way, the tattoo may act as an anchor to a fixed idea for the client. Over half of the interviewees observed that for some clients, some degree of meaning-making occurs after the ink is in the skin. Two interviewees noted that it is in storytelling and conversations with others after having been tattooed that meanings may reveal themselves. For instance, interviewee 5 suggested that the meaning of a tattoo can “change with you”, and “unlike a canvas when you paint on it…it's done…when it's on a living human…it will always change”. This is evidence of social character inherently adopted by a tattoo as an icon visible to others; both internal changes and external influences become crucial to how tattooed individuals speak about their tattoos, and how others speak of them.

However, in having a look at the frequency of each of these responses from the tattoo artists being interviewed, it is interesting to note that almost all agreed that the meaning-making process is fluid to some extent; it is not necessarily time-constrained and often has several influences. In fact, several interviewees expressed their experience as a combination of all three stages in their professional practice, with interviewee 6 stating simply, “all of the above”, when asked whether meaning develops before, during, or after tattooing. Despite the random sample of tattoo artists interviewed, it can thus be surmised that there are multiple ways in which the meaning of a tattoo may develop for the wearer, and it is rarely a static process. Tattoos may continually serve as an anchor for particular meanings, and a connection point to various experiential, place-based, cultural, and interpersonal experiences over time.

The self, memories, and connections to place as the main influences

The researchers then explored the question of influences on meaning-making concerning tattoos and three main categories emerged. The interviewees felt that meaning is influenced by connection, memories, and the self. These categories are fluid and coexist, with all becoming present across the meaning-making process. Connection was dominant across all interviews and was inclusive of connection to culture, natural spaces, society, and the past. This form of connection is not static and exists and evolves spatially and temporally. The desire to (re)connect influenced much of the meaning within the interviewees. Tattoos signified a way of solidifying a connection to culture, nature, people, and place with interviewee 5 acknowledging that people are “honouring the spirit of that plant or that animal that they feel they have a connection to”.

However, modern society erases this connection, with the urbanization of landscapes depriving people of natural spaces, culture, and connection. Through tattooing, people sought out ways to embed themselves back into something that was bigger than themselves and create meaningful connections. Interviewee 3 summarizes it as

“…in modern society, we don't have the relationship with nature that we're supposed to have, especially in a country like Australia, where the relationship to land and country has been essentially obliterated, and anywhere else in the world where everything is so … urbanized and there is so much urban sprawl, urban growth everything is grey. Everything is concrete. There's a lot of beauty in that as well. But that's not how humans came up. That's not how humans came about. And I think for people who choose to decorate and adorn and modify our bodies, maybe natural elements seem more attractive because it's not something that we get a lot of in our life, even things like the 40-hour workweek five-day working week. It's very rare unless you have a career where you get to interact with and be amongst nature. It is very rare that, you're not amongst four walls, or creating four walls. So maybe being able to look down at your arm and see a butterfly is a reminder that we're…people”.

Memories were equally important in these meaning-making processes. Tattoos were a way to anchor memories of the past to both the present and the future. The permanency of tattoos crystallized these memories into stories that do not fade and could be retold and reframed with meaning. These memories were not only of people but also of places, feelings, and stories. Multiple interviewees acknowledged the role those specific emotions played within the meaning-making process. These stories had both significance for the wearer and the tattoo artist, and it was

“…the part that I love the most about tattooing, but especially the ones where it's like, grandma's favourite flower and tell me stories about the fairy one. Actually comes up a lot with grandparents. Because apparently, everyone's grandparents have a little story of fairies and that kind of thing” (interviewee 4).

Overall, memories and tattoos were connected via positive associations. Although the stories may have been sad (a loved one passing), people chose beautiful, childlike, and whimsical tattoos to tie these memories to the present. Natural elements were often used because of their perceived beauty and the association with positive emotions, which is acknowledged by interviewee 4.

“So when you're a kid playing in feels really fun. Because it's so sensory. And I think that's why a lot of those memories that we really hold on to as kids are like nature related is because outside of those so many senses are activated when you're a kid playing”.

Through these memories and connections, the embodied self was critically important in the meaning of tattoos. Bodies are fluid and so were the stories told—a constant evolution of the self. The body was an outward reflection of the self, and the skin was a blank canvas for storytelling of connections and memories. These stories were interwoven both through conversation and the visual landscape of the skin, as a “memory timeline” outlined by one of the interviewees (8).

The tattooed self-story was not only a journey through life but also a reclamation of the body from outside forces. Tattoos could be a form of trauma healing, renewal, and redefinition of oneself, with some getting tattooed to “get these large-scale abstract pieces for trauma healing for body reclamation, for you know, I guess, even covering up tattoos that have negative meaning and that kind of stuff” (Interviewee 7). While these deeper meanings were important, so too was the redefinition of beauty standards through tattooing. Tattoos facilitated the reshaping of how people felt about their bodies. The process of getting a tattoo gave agency to create their meanings around beauty, with interviewee 4 sharing a story of a client that “want[ed] to feel myself like a piece of art” and interviewee 6 sharing that their client “wanted[ed] to love my arms again and decorating them is like the best shot I've got”.

Ritualization of tattoos: strong nature relationships

Our final question aimed to explore the conversational level of the tattoo. We specifically wanted to explore the ritualization and storytelling around tattoos. We have conceptualized this through four levels, namely decoration, representation, storytelling, and relationships with society, nature, and culture. The most prevalent conversational levels were storytelling and relationships with society, nature, and culture. These levels appeared in all interviews, except one. The interviewees thus expressed that tattooing was a process of deeper meaning-making both through storytelling and relationships. Although most interviews were situated within these categories, the meaning within them was diverse. The actual stories that were told about tattoos were dependent on connection, memories, and the self.

Tattoos were both a storytelling method and a device. Bodies were landscapes where the individuals' stories were carved out through both the process of tattooing and the ritual interactions tattooed bodies had with others. Tattoos could re-story the body and shape it in ways that created meaning for the tattooer, wearer, and society “like male clients who've gotten abstract work from me inspired by a botanical but they want them to look tough and spiky because it's more of a masculine kind of strong thing. So they might go like I'm getting this plant and one of my clients, he wanted a plant that reminded him of family holidays he took as a kid, but he even said to me, or they're very soft rounded plants…. Can you make them a little bit tougher, so they're on the other end of the experience” (interviewee 7).

More broadly, tattoos could communicate the humanity of an experience and the stories people tell about their tattoos to themselves. However, interestingly, the emotional responses tattoos evoked were not always seen as deeply meaningful, but as surface level, as acknowledged by interviewee 7, who states that “wanting to remember a certain moment or you have a certain feeling that even if it's not from your childhood, even if it's just gum nut flower that you see every day and you just like and you want to have it on you because it makes you feel happy? Like it doesn't have any deeper meaning it just makes you happy”. This shows again, similar to the findings above, that meaning-making is diverse, fluid, and socially constructed through storytelling.

Discussion and outlook

Tattoos were not only a communicative storytelling device for both the wearer and the tattooer but also a vessel for relationships to their physical and non-physical world. The body was the foundation of relationship-making, with stories told through cycles. The landscape of the body, or in Goffman's sense the body as a social billboard with a physical and a non-physical side (1976), created the metaphorical walkthrough of the relationship to nature, with each person experiencing this relationship differently. However, nature was overwhelmingly viewed as something people were a part of, with humans trying to get back to a connection with the environment; “people naturally want to feel part of something. They want to feel a reciprocal connection to something that moves them, you know, be another person be a place here. plant or an animal, you know, like they want to consolidate and honour relationship and connectivity” (interviewee 5). This is an expression of the care and connection people had to nature through an embodied experience of being tattooed, in which tattooing is “for some people like a really primal need, like it's an old friend of humanity” (Interviewee 5).

This need to demarcate oneself and practice acts that redefine the self in connection to nature through tattooing should be further explored. The sample size is not representative and is place-based, relying on largely Western perspectives of tattooing. However, this small sample size showcases that people who get nature-related tattoos do care for nature and create meaning through ritual interactionism with both their natural environment and other people. Referring to Milstein's (2008) concept of “humanising natural elements”, people use, for example, botanicals to represent their memories or place-based experiences because they are beautiful. The findings show that there seems to be a need to reconnect with nature; tattoos are one way for Western industrialized society to reclaim what has been rendered invisible or inaccessible.

There are certain limitations of this study that have to be mentioned: First, the intention of the sample of international tattoo artists was to avoid a limitation to the view of Western, educated, industrialized, rich, and democratic societies (Henrich et al., 2010)—which was not met. Therefore, consecutive projects are invited to broaden the sample of tattoo artists and explore various non-Western cultures in less industrialized, “white” social, and cultural contexts. Second, there was also a certain selection bias within our sample as mostly tattoo artists known by the researchers were included, who were also interested in participating. Thus, the sample characteristic did not consider specific cultural backgrounds, gender, or professional backgrounds. Generalizing from the present sample to other groups of tattoo artists or even tattooed people would be inappropriate; the set of explorative interviews was intended to provide initial empirical insights into the role of communication in tattooing and tattooing as a ritual where eco-cultural identities and thus a nature-centric human–nature relationship can be created, reproduced, or manifested. Despite the small sample size, the findings are very fruitful for future applications of the model developed in the theory section.

Thus, the project at hand is the starting point for a larger international research collaboration on eco-cultural identities represented in tattoos. The interviews with tattoo artists helped us to learn about the potential and the scope of researching human–nature relationships in tattoos. The next step will be to capture stories of people wearing tattoos and learn more about conversations in which eco-cultural identities are created. Future research questions could focus on vegan tattoo artists, breast cancer-related tattoos, colonialism, and white-centric tattoo culture (i.e., in Australia).

Other than Goffman, there is little engagement with psychological literature on identity. Therefore, the project points to a need to help strengthen and bring together issues of nature and tattoos in identity. Overall, this project also opens a new field for communication research that helps to strengthen a conversational understanding of communication beyond the ritual perspective. The innovative research approach also includes a re-coupling process; with the conversational approach, the interviews stimulated reflection processes and changed tattooing practices toward creating awareness about environmental protection and conservation. The potential of the tattoo artists in this communicator role needs to be further explored. More generally, the conceptualization of tattooing as a conversational process where meaning is created, common beliefs are (re)produced, new norms are cultivated, and meaningful human–nature relationships are forged stimulates further research studying other rituals and their potential to communicatively re-create a more sustainable society.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by UQ Human Ethics Research Office. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^This research was conducted according to the ethical clearance for a long-term interview series on emerging communicator roles; the clearance was obtained at The University of Queensland in 2020/Human Research Ethics.

References

Alter-Muri, S. (2020). The body as canvas: motivations, meanings, and therapeutic implications of tattoos. Art Therapy 37, 139–146. doi: 10.1080/07421656.2019.1679545

Arnoldi, J. (2010). Sense making as communication. Soziale Syst. 16, 28–48. doi: 10.1515/sosys-2010-0103

Carbaugh, D., and Cerulli, T. (2013). Cultural discourses of dwelling: investigating environmental communication as a place-based practice. Environ. Commun. 7, 4–23. doi: 10.1080/17524032.2012.749296

Carey, J. (1997). “Afterward: the culture in question,” in James Carey: A Critical Reader, eds E. Munson and C. Warren (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press), 308–339.

Carey, J. W. (2007). A Cultural Approach to Communication. Theorizing Communication. Readings Across Traditions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 37–50.

Craighead, C. (2011). (Monstrous) Beauty (Myths): the commodification of women's bodies and the potential for tattooed subversions. Agenda 25, 42–49. doi: 10.1080/10130950.2011.630530

Dann, C., and Callaghan, J. (2019). Meaning-making in women's tattooed bodies. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 13, e12438. doi: 10.1111/spc3.12438

DeMello, M. (1993). The convict body: tattooing among male American prisoners. Anthropol. Today 9, 10–13. doi: 10.2307/2783218

Dervin, B. (1992). From the mind's eye of the user: the sense-making qualitative-quantitative methodology. Qual. Res. Inf. Manag. 9, 61–84.

Dervin, B. (1999). Chaos, order and sense-making: a proposed theory for information design. Inf. Des. 35–57.

Dolese, M., Kozbelt, A., and Hardin, C. (2014). Art as communication: employing Gricean principles of communication as a model for art appreciation. Int. J. Image 4, 63–70. doi: 10.18848/2154-8560/CGP/v04i03/44133

Dolese, M.J., and Kozbelt, A (2020). Communication and meaning-making are central to understanding aesthetic response in any context. Front. Psychol. 11, 473. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00473

Doss, K., and Ebesu Hubbard, A. S. (2009). The communicative value of tattoos: The role of public self-consciousness on tattoo visibility. Commun. Res. Rep. 26, 62–74. doi: 10.1080/08824090802637072

Fenske, M. (2007). Movement and resistance:(tattooed) bodies and performance. Commun. Crit. Cult. Stud. 4, 51–73. doi: 10.1080/14791420601138302

Fenzl, T., and Mayring, P. (2017). QCAmap: eine interaktive webapplikation für qualitative inhaltsanalyse. Zeitschrift Soziologie Erziehung Sozialisation 37, 333–340.

Goffman, E. (1976). Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identities. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Grice, H. P. (1975). “Logic and conversation,” in Syntax and Semantics, Vol. 3, eds P. Cole and J. Morgan (New York, NY: Academic Press), 41–58.

Henrich, J., Heine, S., and Norenzayan, A. (2010). The weirdest people in the world? Behav. Brain Sci. 33, 61–83. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X0999152X

Honneth, A., and Joas, H., (eds). (1991). Communicative Action: Essays on Jürgen Habermas's The Theory of Communicative Action. New York, NY: MIT Press.

Klein, G., Moon, B., and Hoffman, R. R. (2006). Making sense of sensemaking 2: a macrocognitive model. Intell. Syst. IEEE 21, 88–92. doi: 10.1109/MIS.2006.100

Kosut, M. (2000). Tattoo Narratives: the intersection of the body, self-identity and society. Vis. Stud. 15, 79–100. doi: 10.1080/14725860008583817

Kosut, M. (2006). Mad artists and tattooed perverts: deviant discourse and the social construction of cultural categories. Deviant Behav. 27, 73–95. doi: 10.1080/016396290950677

Krtalić, M., Campbell-Meier, J., and Bell, R. (2021). Tattoos and information: mapping the landscape of tattoo research. Proc. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 58, 477–483. doi: 10.1002/pra2.482

Lane, D. C. (2014). Tat's all folks: an analysis of tattoo literature. Sociol. Compass 8, 398–410. doi: 10.1111/soc4.12142

Mayring, P. (2014). Qualitative Content Analysis: Theoretical Foundation, Basic Procedures and Software Solution. Available online at: https://www.ssoar.info/ssoar/handle/document/39517 (accessed October 3, 2019).

Mayring, P., and Fenzl, T. (2014). QCAmap. A Software for Qualitative Content Analysis. Available at: https://www.qcamap.org (accessed October 3, 2019).

Mayring, P., and Fenzl, T. (2019). “Qualitative inhaltsanalyse,” in Handbuch Methoden der empirischen Sozialforschung, eds N. Baur and J. Blasius (Wiesbaden: Springer VS Verlag), 633–648.

Mensah, E., Inyabri, I., and Mensah, E. (2018). The discourse of tattoo consumption among female youth in Nigeria. Communication 44, 56–73. doi: 10.1080/02500167.2018.1556222

Mifflin, M. (2013). Bodies of Subversion: A Secret History of Women and Tattoo, 3rd Edn. New York, NY: PowerHouse Books.

Milstein, T. (2008). When whales “speak for themselves”: communication as a mediating force in wildlife tourism. Environ. Commun. 2, 173–192. doi: 10.1080/17524030802141745

Nash, M. (2018). From “tramp stamps” to traditional sleeves: a feminist autobiographical account of tattoos. Aust Femin Stud. 33, 362–383. doi: 10.1080/08164649.2018.1542591

Patterson, M. (2017). Tattoo: marketplace icon. Consump. Markets Cult. 21, 582–289. doi: 10.1080/10253866.2017.1334280

Phelan, M. P., and Hunt, S. A. (1998). Prison gang members' tattoos as identity work: the visual communication of moral careers. Symb. Interact. 21, 277–298. doi: 10.1525/si.1998.21.3.277

Reid-de Jong, V., and Bruce, A. (2020). Mastectomy tattoos: an emerging alternative for reclaiming self. Nurs. Forum 55, 695–702. doi: 10.1111/nuf.12486

Rothenbuhler, E. W. (2006). Communication as ritual. Communication as...: Perspectives on Theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 13–22.

Sandberg, J., and Tsoukas, H. (2020). Sensemaking reconsidered: towards a broader understanding through phenomenology. Org. Theory 1, 2631787719879937. doi: 10.1177/2631787719879937

Taylor, J. R., and Robichaud, D. (2004). Finding the organization in the communication: discourse as action and sensemaking. Organization 11, 395–413. doi: 10.1177/1350508404041999

Walzer, A., and Sanjurjo, P. (2016). Media and contemporary tattoo. Commun. Soc. 29. doi: 10.15581/003.29.1.69-81

Weder, F. (2022). Nachhaltigkeit kultivieren. Öffentliche Kommunikation über Umwelt, Klima, nachhaltige Entwicklung und Transformation. Communicatio Socialis 55, 146–159. doi: 10.5771/0010-3497-2022-2-146

Weder, F., and Milstein, T., (eds) (2021). “Revolutionaries needed! Environmental communication as a transformative discipline,” in The Handbook of International Trends in Environmental Communication (London: Routledge), 407–419.

Weick, K. (1988). Enacted sensemaking in crisis situation. J. Manag. Stud. 25, 305–317. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6486.1988.tb00039.x

Weick, K. E., Sutcliffe, K. M., and Obstfeld, D. (2005). Organizing and the process of sensemaking. Org. Sci. 16, 409–421. doi: 10.1287/orsc.1050.0133

Wymann, C. (2010). Tattoo: a multifaceted medium of communication. Medien Kultur. 26, 41–54. doi: 10.7146/mediekultur.v26i49.2529

Keywords: tattoo, sensemaking, communication, conversation, sustainability

Citation: Weder F, Burdon J and Kearney C (2023) Eco-cultural identity building through tattoos: a conversational approach. Front. Commun. 8:1197843. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2023.1197843

Received: 03 April 2023; Accepted: 02 October 2023;

Published: 22 November 2023.

Edited by:

Douglas Ashwell, Massey University Business School, New ZealandReviewed by:

Eyo Mensah, University of Calabar, NigeriaCharlotte Dann, University of Northampton, United Kingdom

Jennifer Campbell-Meier, Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand

Copyright © 2023 Weder, Burdon and Kearney. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Franzisca Weder, RnJhbnppc2NhLldlZGVyQGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

Franzisca Weder

Franzisca Weder Jasmine Burdon

Jasmine Burdon Caitlin Kearney2

Caitlin Kearney2