94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Commun., 22 August 2023

Sec. Culture and Communication

Volume 8 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomm.2023.1190190

With the rapid development of China's economy, entrepreneurship plays an important role in advancing social and economic development. Along with the wave of global entrepreneurship, female entrepreneurs and entrepreneurial activities in China have thrived. Further more, cultural orientation can shape entrepreneurs' entrepreneurial motivation, thereby creating different types of enterprises. Based on the self-construction theory, this paper is devoted to the analysis of the influence of cultural orientation, cultural integration on female returnee entrepreneurs' entrepreneurial motivation. A total of 488 Chinese female returnee entrepreneurs participated in the survey. The structural equation modeling (SEM) and multi-group analysis were used to evaluate the relationship between the model structures. It provides a new perspective on the relationship between female returnee entrepreneurs' cultural orientation, entrepreneurial motivation, and the role of cultural integration. The results show that due to the influence of globalization and diversified cultural background, the cultural orientation of Chinese female returnee entrepreneurs tends to be more feminine rather than traditional masculine, and they pay more attention to meeting the entrepreneurial motivation of opportunity, such as interests, self-value expression and market opportunities, rather than simple survival. Cultural orientation has a significant influence on the entrepreneurial motivation of Chinese female entrepreneurs, and cultural integration plays a moderating role in this influence. The last part of the paper summarizes the theoretical and practical significance.

With the rapid development of China's economy, entrepreneurship plays an important role in advancing social and economic development (Zhao et al., 2020; Yu and Liu, 2021). Support by government policies for entrepreneurial behaviors has resulted in the continuous expansion of entrepreneur community in China (Huang et al., 2021). According to the 2019/2020 Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM), the female entrepreneurship rate increased by 6.6% when comparing the same set of 50 countries that participated in the survey in 2018 and 2019; in comparison, the male rate increased by 0.7% (Bosma et al., 2020). Along with the wave of global entrepreneurship, female entrepreneurs and entrepreneurial activities in China have thrived (Franzke et al., 2022). Female entrepreneurs have become a considerable part of the entrepreneurial behaviors. Academic research on female entrepreneurship has become increasingly abundant. The uniqueness of female entrepreneurs has received more attention from the business community and the academia (Li et al., 2019).

Duan and Sandhu (2022) pointed out that cultural orientation can shape entrepreneurs' entrepreneurial motivation, thereby creating different types of enterprises. In addition, their studies found that entrepreneurs from the Group of Seven (G7) and Pacific Rim countries meet significant cross-cultural differences in entrepreneurial motivation and ability cognition (Duan and Sandhu, 2022). Mustafa and Treanor (2022) found that male and female of different races differ widely in interest in entrepreneurial types. In fact, men and women bear different social responsibilities in social roles and division of labor in different countries due to cultural influences (Kang et al., 2021). In Chinese culture, men do farm work and women engage in spinning and weaving; men work outside and women stay home (Tan et al., 2022). According to Hofstede's well-known Cultural Dimensions Theory, the masculine/feminine society dimension indicates the degree to which gender determines the role of men and women in society (Adamovic, 2023). Masculinity refers to the society that has completely different social gender roles, men are expected to be confident, strong, focus on career, status and material achievements, while women are expected to be moderate, tender and concerned with the quality of life. Whereas, femininity refers to the society where gender roles overlap and where both men and women are expected to be moderate, tender and concerned with the quality of life (Hofstede, 1991).

A review of the research on female entrepreneurship in China suggests that unlike most Western countries that pursue gender equality, female entrepreneurs in China usually start their own businesses in order to make a living when their families are poor or when there is not a better career choice (Franzke et al., 2022). Necessity-driven entrepreneurship dominates the entrepreneurial motivations of Chinese female entrepreneurs while the rate of opportunity-driven entrepreneurship is low (Wang Y. et al., 2020; Franzke et al., 2022). Necessity-driven entrepreneurship represents a lower-level type of entrepreneurship as it has major disadvantages in terms of job creation, industrial upgrade, innovative products, market expansion, and better economic and social competitiveness (von Bloh et al., 2020; Hou et al., 2023). Scholars believe that women have weaker physical strength, risk tolerance, human capital and social capital (Fang et al., 2020; Simarasl et al., 2022). In major steps of entrepreneurial process, almost all women face gender discrimination, to some extent (Ramadani et al., 2022). This will further widen the gender gap in entrepreneurship and exacerbate the inequality of economic and social status between men and women (Xie and Wu, 2021).

However, entrepreneurship among the new generation of Chinese women has gathered momentum as globalization picks up speed and feminism emerge (Fu et al., 2022). In addition, besides the influence of traditional Chinese culture, the infiltration and integration of Western culture in China greatly impacts all steps of entrepreneurship among Chinese women (Xu et al., 2022). A large number of Chinese women with Western education and living backgrounds have been exposed to and understand Western culture (Jin and Wang, 2022). Under this premise, Chinese female returnee entrepreneurs with multicultural backgrounds continue to expand. In 2023, 68 female entrepreneurs in the Hurun World Richest Women are from China, counting about two-thirds of the whole world (Hurun.net., 2023). These data show that Chinese female entrepreneurs make magnificent contribution to economic growth and social development. Meanwhile, as they are increasingly exposed to Western culture, the entrepreneurial motivation of female returnee entrepreneurs may also change the pursuit from necessity to opportunity (Cooke and Xiao, 2021).

Female entrepreneurship in China has attracted a great deal of attention (Fu et al., 2022). However, existing studies related to cultural concepts are mainly theoretically national, few studies have been focused on individual level and examined the changes in female entrepreneurial motivation from the perspectives of native individual cultural orientation, multicultural background, cultural integration, and gender differences (Cooke and Xiao, 2021; Shi and Wang, 2021; Franzke et al., 2022). An understanding of how cultural differences and integration affect female's entrepreneurial motivation can help explain the gender gap in entrepreneurship and sharply reduce entrepreneurship problems due to cultural and gender differences. Therefore, based on the self-construction theory and discussion above, this paper aims to examine how Chinese female returnee entrepreneurs' individual cultural orientation (femininity/masculinity) affects entrepreneurial motivation (necessary/opportunity); further discuss and analyze the moderate impact on the relationship between cultural orientation and entrepreneurial motivation. By doing so, this study devoted to help female entrepreneurs thriving and their entrepreneurial types upgrading. This is of great significance for women's employment, social value and for China's economic development and social harmony.

Self-construction originates from the study of cultural psychology and is the basis of interactions between humans and society, as well as the central conception of how individuals view themselves, others, and social relations as a whole, and its far-reaching impact on human psychology, motivation and behavior (behavioral decision-making, preference construction, social cognition, etc.) (Xie, 2023). Self-construction theory refers to a process of building self-knowledge and awakening that reflects both the essential changes in the individual's socio-cultural experience and the individual differences in constructing the self (Sedikides, 2021). Individuals are influenced by different environments, which in turn produce different processes of self-construction and ultimately differences in motivation and behavior (Xie, 2023). Culture, as an important external environment, provides the background color for the individual's self-construction. In the process of rapid globalization, individuals' values, motivations, and behaviors are influenced by multiple cultural orientations, which result in different self-construction outcomes (Zhang et al., 2021). Most scholars currently focus on the processes and types of self-construction (Maunz and Glaser, 2023). Individuals with different cultural backgrounds perceive different external stimuli and develop different behavioral motivations and self-images in the process of self-construction (Zuo, 2022).

Focusing on the field of entrepreneurship, scholars consider entrepreneurship as an economic act, but in the new era, entrepreneurship has taken on more significance and is an important manifestation of self-construction for entrepreneurs (Sun et al., 2022). Under the influence of different cultural orientations, there are differences in the self-construction process of entrepreneurs, which in turn affects the motivation of entrepreneurship (Wikantiyoso et al., 2021). The entrepreneur's motivation is not only to maintain survival and solve employment, but also to pursue self-worth and contribute to society (Kusa et al., 2021). Therefore, this study will take self-construction theory as the basic theory to explore the process of self-construction and the mechanism of change of entrepreneurial motivation of entrepreneurs under the influence of different cultural environments.

In recent years, an increasing number of scholars have begun to study how cultural backgrounds affect female entrepreneurial activities, these studies focus on how social norms, gender discrimination, and views on failure influence female entrepreneurs (Ojong et al., 2021; Franzke et al., 2022). In addition, cultural studies related to gender dimensions, scholars indicated that masculine/feminine cultural orientation is usually seen in society, this cultural phenomenon indicates the degree to which gender determines the role of men and women in society (Liñán et al., 2020; VanderLaan et al., 2022).

A country with masculine culture is imbued with a strong sense of social competition and clear gender roles. Success is measured by wealth, fame, and social encouragement (Wang and He, 2022). Its culture emphasizes competition, accomplishment and work performance. People “live to work”. Male members of society focus on self-development, ambition, work performance, power, self-confidence and material achievement while female members are considered to be always more modest, gentler and more concerned about the quality of life (Chen et al., 2022). Therefore, gender discrimination is seen in masculine society, for example, women are expected to devote their energy to family and improve the quality of spiritual wellbeing rather than leaving the family to seek employment or start a business. Male cultural orientation has a negative impact on female entrepreneurial choices (Aley and Thomas, 2021).

Society with feminine cultural orientation focuses on the progress of mutual relations and their gender roles overlap. For example, men and women are considered to be modest, gentle and concerned about the quality of life (Gilal et al., 2018; Amatulli et al., 2021). People tend to reconcile and negotiate to resolve conflicts in an organization and their culture emphasizes equality and unity, it is believed that the most important thing in life is not possession of materials but spiritual communication (Amatulli et al., 2021). They believe that “life is short and should be enjoyed slowly and carefully,” and “work is for life,” therefore, countries with feminine cultural orientation encourage women to start a business and realize their own value in order to improve their quality of life, nourish their minds, and develop hobbies (Hamadneh et al., 2021). Countries dominated by masculine cultural orientation include the Saudi Arab, Austria, Germany, Italy, Japan, Mexico, and China; countries with a dominant feminine cultural orientation are Chile, Costa Rica, Denmark, East Africa, Finland, the Netherlands, Portugal, and Sweden (Hofstede, 1991; Ciziceno and Pizzuto, 2022).

Summarize above, existing studies related to cultural concepts are mainly focusing on national level, and Hofstede's cultural scale have been widely used in related research topics (Hofstede, 1991; Ciziceno and Pizzuto, 2022). Few studies have been focused on individual level and examined the changes in female entrepreneurial motivation from the perspectives of native individual cultural orientation, multicultural background, cultural integration, and gender differences (Luksyte et al., 2022). However, due to the complexity and different cultural levels, the study of individual culture issue has become more significant to scholars. In order to solve this problem, Dorfman and Howell firstly investigate cultural dimensions from an individual psychological perspective instead of from the area of national culture and developed new scales to measure culture (Clugston et al., 2000; Wang et al., 2021). The new scales not only resolved the limitation of Hofstede's cultural model which is only adaptive for national culture measurement, but also created and refined the individual-level instruments to measure culture (Wang et al., 2021). Dorfman and Howell's cultural model has been used widely to measure cross cultural studies and made a huge contribution to measure culture at an individual level by assessing all of the four original Hofstede's dimensions which are collectivism/individualism, masculinity/femininity, power distance and uncertainty avoidance (Wang et al., 2021). Therefore, Dorfman and Howell's cultural model and scale are chosen for this study.

Entrepreneurial motivation drives entrepreneurial behaviors and it is the motivational factor that encourages entrepreneurs to seek and seize opportunities and strive to achieve entrepreneurial success (Murnieks et al., 2020; Williams et al., 2023). Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) divides entrepreneurial motivations into two types: opportunity-driven and necessity-driven (Cervelló-Royo et al., 2020). Opportunity-driven entrepreneurship is theoretically based on the Pull Factor Theory (Barcena-Martin et al., 2021). According to Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs Theory, when an individual's basic physiological needs are met, their needs will approach self-esteem and self-actualization, individuals choose to start a business because entrepreneurship can realize their self-esteem and self-actualization (Coffman and Sunny, 2021). Necessity-driven entrepreneurship is theoretically driven by the Push Factor Theory, which believes that people choose to start a business because of the current bad or unpromising jobs, such as low income, unemployment, unsatisfactory working conditions, and absence of flexible working hours to balance work and family (Zhang and Zhou, 2019; Barcena-Martin et al., 2021).

With the acceleration of immigration, overseas study, travel, and globalization, a large number of Chinese women with Western education and living backgrounds have been exposed to and understand Western culture (Li et al., 2022). The infiltration and integration of Western culture greatly impacts entrepreneurship among Chinese women in all respects (Wang Y. et al., 2020). Bierwiaczonek and Kunst (2021) believe that acculturation is one of the results of cultural adaptation. Individuals exposed to a new cultural environment learn the motivations, needs, behaviors, values and attitudes in the new culture and combine them with the original ethnic culture, it is a two-way process when individuals are able to maintain the original culture and choose to integrate into a new culture (Bierwiaczonek and Kunst, 2021). Previous research explained acculturation orientation categories—separation, integration, assimilation, and marginalization (Bierwiaczonek and Kunst, 2021; Schmitz and Schmitz, 2022). Separation occurs when individuals choose not to adapt to the new cultures but only to maintain their own culture; integration is when individuals maintain part of their original cultures and are able to adapt to the new cultures to some extent; assimilation occurs wherein the original culture is wholly abandoned and the new culture is adopted in its place and marginalization occurs when an individual is not a part of his original culture, nor is he a part of the new culture, it is the rarest in acculturation (Bierwiaczonek and Kunst, 2021; Schmitz and Schmitz, 2022). Studies show that most people are more willing to coordinate and blend their cultural identities, rather than simply assimilate or transform into host culture, occasionally, in acculturation individuals may completely assimilate with the host culture or choose to maintain the original culture (Richter et al., 2021). Many scholars also claim that most consumers are not willing to be marginalized or follow the only culture, they would rather choose to integrate different cultures (Ward, 2020; Richter et al., 2021). Therefore, the integration of various cultures affects individuals' cultural identity.

Under this premise, Chinese female returnee entrepreneurs with multicultural backgrounds continue to expand. Multicultural experience refers to all direct and indirect experiences gained by individuals when they communicate or connect with members or elements of other cultures (Hemmert et al., 2022). The acculturation phenomena due to multicultural experience has become a hot topic in the field of cross-cultural studies (Richter et al., 2021). Wang Y. et al. (2020) pointed out that studies of entrepreneurs' multicultural experience are also emerging. A growing number of researchers are beginning to investigate how individuals with more than two cultural experiences in the context of globalization use their multicultural background advantages in entrepreneurship, including research on international entrepreneurship and born global enterprises, and research on immigrant entrepreneurs and overseas returnees (Wang Y. et al., 2020; Gupta et al., 2021; Zahra, 2021). Although studies have examined the impact of entrepreneurs' overseas experience on corporate innovation behavior, network resources, and business know-how, very few studies have analyzed the influence of entrepreneurs, especially female ones, on entrepreneurial motivation from the cultural perspective, it does not involve the measurement of multicultural integration and its impact (Gupta et al., 2021; Zahra, 2021).

As the literature review mentioned above, studies related to the entrepreneurial motivation of female entrepreneurs, different scholars have reached diversified conclusions on the entrepreneurial motivation (Wang Y. et al., 2020). The results illustrate that in countries with feminine cultural orientation, female entrepreneurs are mostly driven by hobbies, pursuit of accomplishment and self-actualization, and the autonomy of seeking employment through business opportunities (Wang Y. et al., 2020). These are all opportunity-driven entrepreneurship.

In countries dominated by masculine cultural orientation, female's entrepreneurial motivations are mostly necessity-driven (Jafari-Sadeghi, 2020). The common reasons why they choose to start a business include dissatisfaction with their previous jobs, the desire to help their family get rid of poverty, and failure to find other jobs due to unemployment, desire to balance work and family, and frustration or bottleneck in their previous jobs (Solesvik et al., 2019; Jafari-Sadeghi, 2020). In addition, Chen and Shi (2020) found that if women start a business for a better balance between work and family life (necessity-driven), they are less likely to achieve entrepreneurial success; if they are motivated by risks (opportunity-driven), it is easier to succeed.

In summary, this article makes the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1: Masculine cultural orientation has a positive impact on the necessity-driven entrepreneurial motivation of Chinese female returnee entrepreneurs.

Hypothesis 2: Feminine cultural orientation has a negative impact on the necessity-driven entrepreneurial motivation of Chinese female returnee entrepreneurs.

Hypothesis 3: Masculine cultural orientation has a negative impact on the opportunity-driven entrepreneurial motivation of Chinese female returnee entrepreneurs.

Hypothesis 4: Feminine cultural orientation has a positive impact on the opportunity-driven entrepreneurial motivation of Chinese female returnee entrepreneurs.

In addition, according to the discussion in the literature, Cultural integration refers to when individuals exposed to a new cultural environment, their original motivations, needs, behaviors, values and attitudes will be affected by the different level of culture integration, and combine them with the original ethnic culture (Bierwiaczonek and Kunst, 2021). The hypothesizes of this study mentioned that masculine cultural orientation has a positive effect on the necessary-driven entrepreneurial motivation, and a negative effect on the opportunity-driven entrepreneurial motivation. When female entrepreneurs live and work in Western countries for a period of time, they will be affected by cultural integration to varying degrees (Xie and Wu, 2021). Since Western culture is more inclined to feminine cultural orientation, female entrepreneurs who have been exposed to this cultural orientation will more or less weaken the influence of the original masculine cultural orientation on the necessary-driven entrepreneurial motivation due to the adjustment of the new cultural orientation (Dana et al., 2021). On the other hand, the opportunity-driven motivation of entrepreneurship will be strengthened due to the negative moderating effect of feminine cultural orientation (Dana et al., 2021). Therefore, the following hypotheses are formulated:

Hypothesis 5: Cultural integration has a negative moderating effect on the relationship between masculine cultural orientation and necessity-driven entrepreneurial motivation of female returnee entrepreneurs.

Hypothesis 7: Cultural integration has a negative moderating effect on the relationship between masculine cultural orientation and opportunity-driven entrepreneurial motivation of female returnee entrepreneurs.

On the other hand, female entrepreneurs with the original feminine cultural orientation, when they integrate to the western culture, the negative influence of the original cultural orientation on the necessary-driven entrepreneurial motivation is further weakened, while the positive influence on the opportunity-driven entrepreneurial motivation is strengthened. Therefore, the following hypotheses are formulated:

Hypothesis 6: Cultural integration has a positive moderating effect on the relationship between feminine cultural orientation and necessity-driven entrepreneurial motivation of female returnee entrepreneurs.

Hypothesis 8: Cultural integration has a positive moderating effect on the relationship between feminine cultural orientation and opportunity-driven entrepreneurial motivation of female returnee entrepreneurs.

On the basis of self-construction theory, the above literature and discussion, a conceptual model was built (see Figure 1). This study is committed to establishing a basic model to study the impact of cultural orientation on female returnee entrepreneurs' motivation. With the process of cultural integration as a moderating variable, this study explores whether cultural integration has a moderating effect between the relationship between dependent and independent variables.

A structured questionnaire was completed to measure several variables by Chinese female returnee entrepreneurs, which including female entrepreneurs' background information, cultural orientation, cultural integration process and entrepreneurial motivation. All scales are based on the verification and moderate revision of mature ones compiled by previous scholars. The questionnaire is composed of three parts. The first part is about personal information, including age, occupation before starting a business, type and industry of the business started, and education level. The second part involves the measurement of variables in this study, including the cultural orientation and entrepreneurial motivation of female entrepreneurs. The third part is the measurement of the degree of cultural integration by female entrepreneurs with multicultural backgrounds.

A strict standard was set for the qualifications of the respondents for the questionnaire. First, the respondents must be female entrepreneurs. Secondly, the target respondents are divided into two groups: without diversified backgrounds (Group 1) and that with diversified backgrounds (Group 2) according to whether the survey respondents have worked and lived abroad. Respondents who do not have diversified backgrounds do not need to answer the questions related to acculturation in the last part of this questionnaire. Online and offline questionnaires are used at the same time for the study. The samples are distributed all over China with the majority from Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou and Shenzhen. This survey follows the principle of anonymity in order to attract respondents and protect their rights and privacy. The identity of the interviewees involved in the survey and the information about their affiliations will not be mentioned in this article except that the author knows it.

In the formal testing phase, a total of 565 questionnaires were issued and 504 questionnaires, or 89.2%, were returned. After we sorted out and screened the data, 96.8% or 488 questionnaires were valid, with 251 from Group 1 and 237 from Group 2. Among the 488 respondents, the 25–30 age group and the 30–35 age group combined accounted for more than 60% of the samples, which was followed by the 35–40 age group, at 19.5%. The three age groups accounted for over 80% in total. A total of 63% of respondents hold bachelor's or master's degrees and the remaining 37% have a degree below undergraduate or above the master. This shows that the Chinese female entrepreneurs have received a relatively high education level. In order to test whether there is a reaction bias in the survey sample, an independent sample T-test was conducted on the personal information scale of the sample, and the result showed that t > 0.05. Indicates that covariates (age, occupation before starting a business, type and industry of the business started and education level) showed no significant difference, indicating that there was no response bias in the questionnaire samples (see in Table 1).

In order to ensure the reliability and validity of the questionnaire, this study adopted mature scales in existing literature, then combined with the context of this study, and made appropriate amendments to the scale after discussion with three scholars in this field. This study has chosen the scale of Dorfman and Howell to measure the masculine/feminine cultural orientation of the target respondents. This methodology is highly reliable and widely used in the academia. This scale contains 4 femininity and 4 masculinity items. The second part of the scale was adapted to Liñán et al.'s (2020) research, the scale includes 5 necessity-driven and 5 opportunity-driven items. The above variables are measured using 7-level Likert measurement method, where 1 means “completely disagree” and 7 means “completely agree”. The descriptive statistical results, reliability and validity analysis of the constructs are shown in Table 1.

The third part of the scale adopts the Cultural Life Style Inventory (CLSI) to measure the process of acculturation. Based on theory and a reliable cultural adaptation model, the CLSI indicator aims to measure the comprehensive model of cultural adaptation, not just the degree of assimilation (Torres and Rollock, 2004). So far, researchers have resolved the failure of cultural adaptation by applying CLSI to individuals' cultural adaptation, and ensured high reliability and effectiveness. CLSI indicators include various items based on five orthogonal cultural adaptation elements: (1) family language; (2) foreign language; (3) social connections and social activities; (4) cultural transformation and cultural activities; and (5) cultural identity and cultural pride. The CLSI indicators include 21 questions about behaviors and 8 questions about attitude. Therefore, it represents the process behavior and attitude dimension of acculturation. It also excludes social and demographic factors and becomes one of the most useful measures of acculturation.

The analysis of variance indicated that among the female entrepreneurs involved in this survey, age does not have a significant influence on the cultural orientation and acculturation. In the two dimensions of entrepreneurial motivation, age has a significant impact on necessity-driven entrepreneurship. But age does not remarkable affect opportunity-driven entrepreneurship. Educational level significantly impacts the cultural orientation of female entrepreneurs. The respondents with a high educational level have a high feminine cultural orientation. Education level does not exert significant influence on acculturation. Educational level has a significant impact on necessity-driven entrepreneurship and opportunity-driven entrepreneurship among female entrepreneurs. Respondents with an associate degree and below enjoys a high rate of necessity-driven motivation while those with a bachelor's degree, master's degree and above have a high rate of opportunity-driven motivation. In the cultural orientation analysis part, mean of femininity is higher than that of masculinity. In addition, the results of entrepreneurial motivation indicated that the mean score of opportunity-driven motivation is higher than that of necessity-driven motivation (see Table 1).

In terms of data analysis, this study adopts a two-step method: confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) for the measurement model, structural equation modeling (SEM) for the structural model and multi-group analysis to test the moderator (Hair et al., 2017). Considering the reliability of the measurement, Cronbach's alpha was 0.918 for femininity, 0.924 for masculinity, 0.947 for necessity-driven and 0.921 for opportunity-driven, which exceeds the threshold value of 0.70. All items of cultural orientation construct were ≥0.50 and remain in the following analysis step. In contrast, item 2 of Necessity-driven and item 1 of opportunity-driven motivation have been excluded.

AMOS17.0 was used to test the discriminative validity and cohesion validity of model variables. Confirmatory factor analysis was performed for 4 variables in the model, and the discriminative validity of each variable was tested by comparing the degree of fit indicators of the hypothesis model and the competition model. The analysis results are shown in Table 2, the solutions are CMIN = 396.21, CMIN/DF = 4.40, P = 0.00, Goodness of Fit Index (GFI) = 0.90, Adjusted Goodness of Fit Index (AGFI) = 0.87, Normed Fit Index (NFI) = 0.94, Comparative Fit Index (CFI) = 0.95, Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) = 0.94, Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) = 0.08.

The calculation results show that the model fitting effect is good, and all fitting indicators are better than the acceptable level (Hair et al., 2017). Moreover, the squared multiple correlation (SMC) value is higher than the acceptable level (R2-value is between 0.66 and 0.89), which also shows the reliability of the variable. The reliability of the structure can be evaluated and confirmed on the basis of the factor loading and the average variance extracted (AVE). The factor loading ranges from 0.81 to 0.94, which is higher than the acceptable level of 0.5. The critical ratio (CR) is much higher than 1.96 at P < 0.05 (Hair et al., 2017). AVE is greater than the acceptable level of 0.50 (Hair et al., 2017). In addition, if the square root of the AVE is greater than the correlation between a structure and any other structure, the validity of this structure can be confirmed (see Tables 3, 4).

For Hypothesis 1, masculinity has a significant positive impact on necessity-driven entrepreneurship (β = 0.29, CR = 6.51, p = 0.00). Therefore, Hypothesis 1 is supported.

For Hypothesis 2, femininity has a significant negative impact on necessity-driven entrepreneurship (β = −0.28, CR = −6.15, p = 0.00). Therefore, Hypothesis 2 is supported.

For Hypothesis 3, masculinity has a significant negative impact on opportunity-driven entrepreneurship (β = −0.30, CR = −6.39, p = 0.00). Therefore, Hypothesis 3 is supported.

For Hypothesis 4, femininity has a significant positive impact on opportunity-driven entrepreneurship (β = 0.18, CR = 3.29, p = 0.00). Therefore, Hypothesis 4 is supported (see Figure 2).

In adjusting variable analysis, 28 CLSI-related questions help divide the interviewees into three acculturation groups. (A) Only mother language, (B) Most mother language, (C) Most foreign language, (D) Only foreign language, and (E) Foreign language and mother language (cultural integration category). A syntactic data has been built in SPSS statistical software to score individuals and divide them into different acculturation groups based on the largest figure in a particular answer group. Eight respondents with fairly high scores in the two acculturation categories were omitted in the data. Finally, a total of 229 respondents participated in the acculturation part of the questionnaire. The 151 participants classified into the integration category of the acculturation dimension are the target samples of this study (see Table 5).

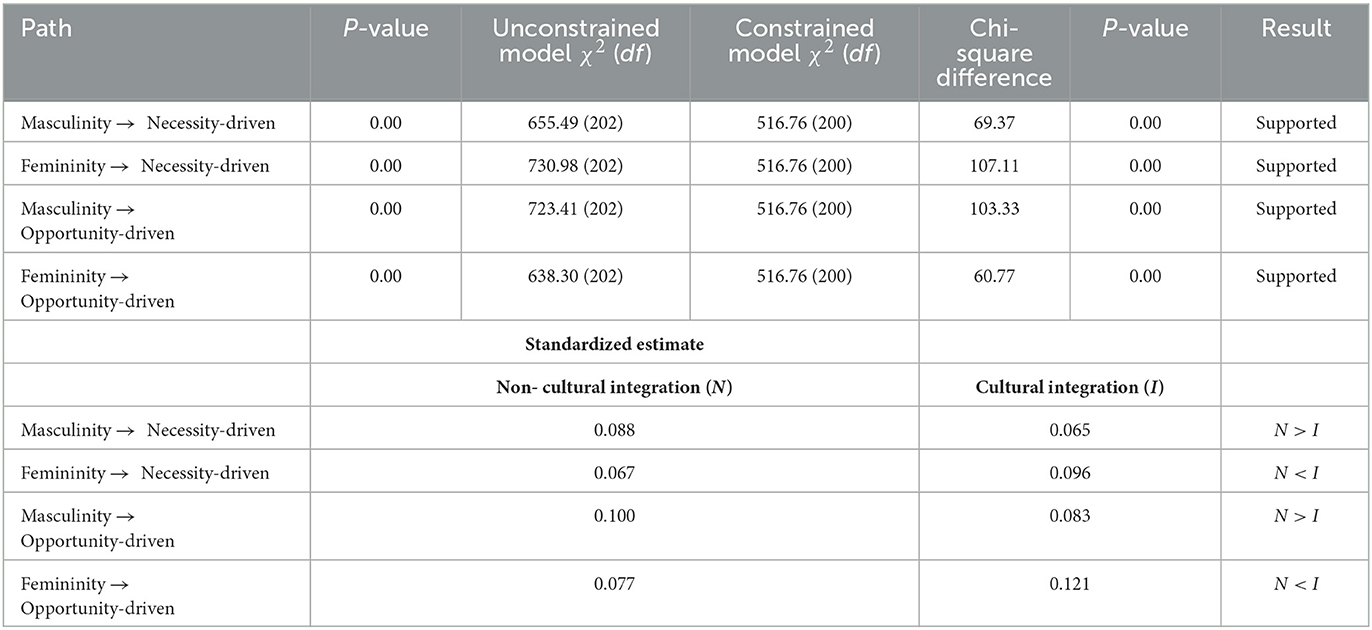

The moderating effect of causality in the model is tested with the multi-group analysis approach. The effective interviewees are classified into two groups (non-cultural integration group and cultural integration group) to compare the constrained model and the unconstrained model, test the chi-square difference, and examine how cultural integration adjusts the relations between cultural orientation (masculinity/femininity) and the entrepreneurial motivation (necessity-driven and opportunity-driven) of female entrepreneurs.

In detail, if the chi-square difference of the unconstrained model and the constrained model divided by the degree of freedom change is >3.84, then a moderate change has occurred in the relative relationship (Hair et al., 2017). Form 5 shows the results of multiple comparison tests between the non-cultural integration group and the cultural integration group.

The multi-group model shows a good fitting model with all indicators above the acceptable level. Fitting indicators: CMIN/DF = 3.76, p = 0.00, GFI = 0.89, AGFI = 0.85, RMSEA = 0.08, CFI = 0.95, NFI = 0.93, TLI = 0.93.

For Hypothesis 5, the masculinity → necessity-driven entrepreneurship paths in the unconstrained model and the constrained model differ widely. This finding indicates that cultural integration can significantly adjust this path and the moderating effect supports Hypothesis 5. The influence of masculinity in the non-acculturation group (S.E. = 0.09, p = 0.00) on necessity-driven entrepreneurship was larger than that in the cultural integration group (S.E. = 0.07, p = 0.00). This indicates that the relationship between masculinity and necessity-driven entrepreneurship has a greater impact on non-cultural integration Chinese consumers than on cultural integration ones (see Table 6).

Table 6. Multiple group tests between the non-cultural integration group and the cultural integration group.

For Hypothesis 6, the femininity → necessity-driven entrepreneurship paths in the unconstrained model and the constrained model differ widely. This finding indicates that cultural integration can significantly adjust this path and the moderating effect supports Hypothesis 6. The influence of femininity in the non-cultural integration group (S.E. = 0.07, p = 0.00) on necessity-driven entrepreneurship was lower than that in the cultural integration group (S.E. = 0.09, p = 0.00). This indicates that the relationship between femininity and necessity-driven entrepreneurship has a smaller impact on non-cultural integration Chinese consumers than on cultural integration ones (see Table 6).

For Hypothesis 7, the masculinity → opportunity-driven entrepreneurship paths in the unconstrained model and the constrained model differ widely. This finding indicates that cultural integration can significantly adjust this path and the moderating effect supports Hypothesis 7. The influence of masculinity in the non-cultural integration group (S.E. = 0.10, p = 0.00) on opportunity-driven entrepreneurship was larger than that in the cultural integration group (S.E. = 0.08, p = 0.00). This indicates that the relationship between masculinity and opportunity-driven entrepreneurship has a greater impact on non-cultural integration Chinese consumers than on cultural integration ones (see Table 6).

For Hypothesis 8, the femininity → opportunity-driven entrepreneurship paths in the unconstrained model and the constrained model differ widely. This finding indicates that cultural integration can significantly adjust this path and the moderating effect supports Hypothesis 8. The influence of femininity in the non-cultural integration group (S.E. = 0.08, p = 0.00) on opportunity-driven entrepreneurship was lower than that in the cultural integration group (S.E. = 0.12, p = 0.00). This indicates that the relationship between femininity and opportunity-driven entrepreneurship has a smaller impact on non-cultural integration Chinese consumers than on cultural integration ones (see Table 6).

The new generation of female entrepreneurs in China and the stereotyped Chinese women in traditional culture differ widely, they are completely different individuals (Wang Z. et al., 2020). This phenomenon has been confirmed by the academic circles and the business community (Ojong et al., 2021; Franzke et al., 2022). As China accelerates its economy, society, and globalization and women's self-consciousness awakens, women's values, education levels and personal experiences have undergone tremendous changes (Wang Y. et al., 2020). Women entrepreneurs have changed their views on entrepreneurship and entrepreneurial ways, and more and more women have become entrepreneurs (Amatulli et al., 2021). Female entrepreneurship has become an important way to help women get rid of poverty, improve their status, relieve employment pressure, and achieve economic development and social progress (Amatulli et al., 2021). This article aims to examine the cultural orientation structure (masculinity and femininity), explain the current entrepreneurial motivations (opportunity-driven and necessity-driven) of Chinese female entrepreneurs, and how cultural integration affects the relationship between them. As this study expected, the eight hypotheses proposed based on the literature review were established and evaluated according to the relationship between independent variables. The analysis results showed that all eight hypotheses were accepted.

The rapid rise of Chinese female entrepreneurs as a special group epitomizes Chinese women's participation in economic and social development to mark the development of Chinese women (Franzke et al., 2022). The research findings show that it is improper to classify Chinese female entrepreneurs as masculinity category based on the cultural integration in traditional views. Specifically, the results of hypotheses one and three indicated that, masculinity cultural orientation has a positive impact on necessity-driven entrepreneurial motivation, but a negative impact on opportunity-driven entrepreneurial motivation. Female returnee entrepreneurs with a masculinity cultural orientation are more willing to choose comfortable and leisure jobs, and most of the reasons for starting a business revolve around: they are not satisfied with their previous jobs and it is difficult to find a more enjoyable job (Wang Y. et al., 2020). In addition, partly because they seek to balance work and family care, they are more willing to spend more time and energy on maintaining family happiness and taking care of the elderly and children (Jafari-Sadeghi, 2020). On the contrary, because opportunity-driven motivation requires entrepreneurs to invest an amount of time and energy, it is likely that the entrepreneurial environment will not be very comfortable, and the entrepreneurial process will be very tough (Coffman and Sunny, 2021). Inevitably, entrepreneurs will not be able to balance work and family well, which is contrary to the masculinity cultural orientation (VanderLaan et al., 2022). Therefore, masculinity cultural orientation will have a negative impact on opportunity-driven entrepreneurial motivation.

Moreover, hypotheses two and four showed that femininity cultural orientation has a negative impact on necessity-driven entrepreneurial motivation, but a positive impact on opportunity-driven entrepreneurial motivation. The results show that under femininity cultural orientation, women's social status is rising and an increasing number of women begin to pursue independence and self-improvement. Taking care of children, washing and cooking is no longer the exclusive job of women. Most of the entrepreneurial motivations of female entrepreneurs are to achieve self-value, which is specifically manifested as doing what they want to do, contributing to the society, making their interests and ideas practical, pursuing a sense of accomplishment, getting more respect, obtaining work autonomy and profit through entrepreneurial activities.

Hypotheses five to eight indicated that cultural integration has a moderating effect on the relationship between cultural orientation and entrepreneurial motivation. As this study mentioned above, integration refers to individuals keep their original cultural orientation and adapt to new cultural orientation at same time (Bierwiaczonek and Kunst, 2021). When the original cultural orientation of female returnees is masculinity culture, the higher the degree of Western cultural integration, the more they will be affected by Western cultural integration, the more obvious their pursuit of female independence, gender equality, self-worth realization and social responsibility, and the lower the degree of necessity-driven entrepreneurial motivation (Hemmert et al., 2022). Therefore, cultural integration has a negative moderating effect on the relationship between masculine cultural orientation and necessity-driven entrepreneurial motivation and the relationship between masculine cultural orientation and opportunity-driven entrepreneurial motivation of female returnee entrepreneurs. On the other hand, when the original cultural orientation of female returnee entrepreneurs is feminine culture, as this study mentioned before, their original entrepreneurial motivation is more opportunistic (Xie and Wu, 2021). The integration of western culture will weaken the influence of female entrepreneurs on necessary-driven entrepreneurial motivation, and strengthen the influence of opportunity-driven entrepreneurial motivation (Dana et al., 2021). Therefore, cultural integration has a negative moderating effect on the relationship between feminine cultural orientation and necessity-driven entrepreneurial motivation and the relationship between feminine cultural orientation and opportunity-driven entrepreneurial motivation of female returnee entrepreneurs.

The first contribution of this research aims to achieve theory development, this study constructs a new model combines cultural orientation, cultural integration and female returnee entrepreneurs in order to analyze the influence of cultural factors on entrepreneurial motivations for the first time. This study reviewed and evaluated various theories when studying entrepreneurial motivations and culture and further assimilated previous researches to develop an improved and coherent picture.

Secondly, this study enriches existing research on female entrepreneurs. The previous research related to cultural orientation and entrepreneurial motivation is comparative. Scholars normally selected respondents from two or more countries with different cultural orientation to analyze the cross-cultural issue. This study is one of few studies focusing on one culture and investigates how cultural integration process impacts the entrepreneurial motivation, especially for female entrepreneurs. The results reveal the causal relationship of cultural orientation, cultural integration process and entrepreneurial motivation of returnee female entrepreneurs.

Finally, this study empirically confirmed that the majority of the conceptual model and hypotheses presented have been assessed and validated. The survey measured various constructs, for example (1) cultural orientation factors which looked at individual cultural background and self-identification; (2) entrepreneurial motivation in both necessary-driven and opportunity-driven; (3) the cultural integration process which indicated participants' cultural transformation; and (4) the relationships amongst those constructs and how they impact each other. The result of this quantitative analysis clearly indicated how cultural orientation and integration factors impact entrepreneurial motivations of Chinese returnee female entrepreneurs.

This article gives the following suggestions from the perspectives of self-evaluation mechanism, policy support, resource integration, and service training for female entrepreneurs based on the characteristics of female entrepreneurship in China and government policies.

First, female entrepreneurs should evaluate themselves in a comprehensive and reasonable manner, such as age, cultural background, education level, family role, entrepreneurial advantages and entrepreneurial motivation and make a targeted entrepreneurial plan. Earliest female entrepreneurs were mostly necessity-driven and they usually started small businesses related to retail and service. With the continuous improvement of the personal qualities of female entrepreneurs, their entrepreneurship has involved more industries. Driven by opportunities, female entrepreneurs have become able to display their competence and charm on a wider platform. As such, female entrepreneurs are also expected to have better personal qualities and the ability to balance work and family.

Second, globally the scale of businesses started by female entrepreneurs is smaller than that by males. Female entrepreneurship suffers a yawning capital gap of US$300 million. Approximately 70% of female entrepreneurs in developing countries have no or insufficient support from financial institutions. With the continuous improvement of the entrepreneurial environment, the increase in human capital and private capital of women entrepreneurs, and the diminishing of gender discrimination, the financing by female entrepreneurs will become less difficult and the financing channels will gradually become wider. On this basis, the government support policies should take gender differences into consideration and ease the financing pressure of female entrepreneurs in order to encourage and support female entrepreneurship. In terms of financial support, the government can provide female entrepreneurs with more preferential policies such as financial subsidies, loan interest cuts, and tax reduction and exemption.

Third, in terms of resource integration, it has become a trend for entrepreneurs to build an alliance. By forming alliances with other entrepreneurs, enterprises can reduce risks and gain opportunities for sustainability. The government can take the lead in building a platform for female entrepreneurship to expand entrepreneurial service channels and forge synergy for women to start a business. Following the principle of “gathering peers, complementing each other's advantages and promoting excellence”, the government tries to create conditions for accelerated construction of female entrepreneurship bases, such as entrepreneurship demonstration zones and streets. This way aims to provide women with a low-rental entrepreneurial environment with one-stop services, thus forming a benign atmosphere for entrepreneurship and employment. The government and governing authorities must support female entrepreneurship in an all-round way, and open green channels for female entrepreneurs to apply for a project, expand the space, and raise fund. In addition, government departments must accelerate the building of an IT-based information platform. A bridge is built between market supply and demand so that women can better acquire the market information they need to think over and make decisions before starting a business. They will consider the information in entrepreneurship.

Fourth, the government must fully grasp the characteristics of female entrepreneurs to establish a female entrepreneurship education system, strengthen skills training, and improve female entrepreneurship capabilities. It is necessary for the government to gain a better understanding of female entrepreneurs, and establish an effective channel to inform women with a plan to start a business in a timely manner. Secondly, the government, enterprises, schools, and other social organizations work together to establish an entrepreneurship training mechanism and institutions to gradually turn them into incubators and accelerators for female entrepreneurship and provide all-round and multi-level entrepreneurship training and services. Female entrepreneurs continuously gain entrepreneurial knowledge to improve market analysis ability, sense of competition in market, organization and management ability, and build entrepreneurial self-confidence. Targeted training and entrepreneurial consulting services can help these female entrepreneurs understand China's economic laws and regulations, acquire knowledge in industry and commerce, taxation, finance, technology, management and labor. This can help them choose the right business industry and make investment less blind to increase the success rate of entrepreneurship and promote the healthy economic development of China.

Although this study has done sufficient work, several limitations still need to considered in this paper. Firstly, the sample size is limited in this study. A total of 488 participants were recruited in this study. In the future, the sample size can be expanded to improve the representativeness of the sample. In addition, future research can also use both quantitative and qualitative methods, such as in-depth interviews or focus groups to strengthen the data.

Secondly, the target respondents of this study are Chinese female returnee entrepreneurs, however, due to the multicultural background, different level of economic development and globalization, the cultural orientation and cultural integration process of female returnee entrepreneurs may be diverse and the universality of the study may be affected. Therefore, the future research can be adapted in different countries and different business areas.

Finally, this paper analyzes the relevant factors that affect the degree of cultural integration of female returnees, such as age, education background and length of living abroad, as control variables. From another perspective, these variables can also be constructed into a latent variable using the principal component method to measure the potential influencing factors of female returnees' cultural integration. Although no relevant hypothesis has been proposed, the regulatory mechanism of potential factors still needs further rigorous and detailed analysis.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Adamovic, M. (2023). Unlocking the cultural mosaic: a comparison of hofstede and modern cultural value frameworks. Cross-cult. Bus. Manag. Perspect. Pract. 181.

Aley, M., and Thomas, B. (2021). An examination of differences in product types and gender stereotypes depicted in advertisements targeting masculine, feminine, and LGBTQ audiences. Commun. Res. Rep. 38, 132–141. doi: 10.1080/08824096.2021.1899908

Amatulli, C., De Angelis, M., Pino, G., and Jain, S. (2021). Consumer reactions to unsustainable luxury: a cross-country analysis. Int. Mark. Rev. 38, 412–452. doi: 10.1108/IMR-05-2019-0126

Barcena-Martin, E., Medina-Claros, S., and Perez-Moreno, S. (2021). Economic regulation, opportunity-driven entrepreneurship and gender gap: emerging versus high-income economies. Int. J. Entrepren. Behav. Res. 27, 1311–1328. doi: 10.1108/IJEBR-05-2020-0321

Bierwiaczonek, K., and Kunst, J. R. (2021). Revisiting the integration hypothesis: correlational and longitudinal meta-analyses demonstrate the limited role of acculturation for cross-cultural adaptation. Psychol. Sci. 32, 1476–1493. doi: 10.1177/09567976211006432

Bosma, N. S. A. D. J., Hill, S., Ionescu-Somers, A., Kelley, D., Levie, J., and Tarnawa, A. (2020). Global Entrepreneurship Monitor 2019/2020 Global Report. Global Entrepreneurship Research Association, London Business School.

Cervelló-Royo, R., Moya-Clemente, I., Perelló-Marín, M. R., and Ribes-Giner, G. (2020). Sustainable development, economic and financial factors, that influence the opportunity-driven entrepreneurship. An fsQCA approach. J. Bus. Res. 115, 393–402. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.10.031

Chen, G., and Shi, J. (2020). The impact of subjective norms on entrepreneurial motivation. Sci. Res. Manag. 41, 269–278.

Chen, G., Tang, Y., Shen, W., Jiang, Q., and Zhang, R. (2022). Effect of women entrepreneurs' gender-role orientation on new venture performance in China: the role of organizational legitimacy and obtaining investments. Asia Pacific Bus. Rev. 1–27. doi: 10.1080/13602381.2022.2040835

Ciziceno, M., and Pizzuto, P. (2022). Life satisfaction and tax morale: the role of trust in government and cultural orientation. J. Behav. Exp. Econ. 97, 101824. doi: 10.1016/j.socec.2021.101824

Clugston, M., Howell, J. P., and Dorfman, P. W. (2000). Does cultural socialization predict multiple bases and foci of commitment? J. Manag. 26, 5–30. doi: 10.1177/014920630002600106

Coffman, C. D., and Sunny, S. A. (2021). Reconceptualizing necessity and opportunity entrepreneurship: a needs-based view of entrepreneurial motivation. Acad. Manag. Rev. 46, 823–825. doi: 10.5465/amr.2019.0361

Cooke, F. L., and Xiao, M. (2021). Women entrepreneurship in China: where are we now and where are we heading. Hum. Resour. Dev. Int. 24, 104–121. doi: 10.1080/13678868.2020.1842983

Dana, L. P., Tajpour, M., Salamzadeh, A., Hosseini, E., and Zolfaghari, M. (2021). The impact of entrepreneurial education on technology-based enterprises development: the mediating role of motivation. Admin. Sci. 11, 105. doi: 10.3390/admsci11040105

Duan, C., and Sandhu, K. (2022). Immigrant entrepreneurship motivation–scientific production, field development, thematic antecedents, measurement elements and research agenda. J. Enterp. Commun. People Places Global Econ. 16, 722–755. doi: 10.1108/JEC-11-2020-0191

Fang, H., Chrisman, J. J., Memili, E., and Wang, M. (2020). Foreign venture presence and domestic entrepreneurship: a macro level study. J. Int. Finan. Mark. Institut. Money 68, 101240. doi: 10.1016/j.intfin.2020.101240

Franzke, S., Wu, J., Froese, F. J., and Chan, Z. X. (2022). Female entrepreneurship in Asia: a critical review and future directions. Asian Bus. Manag. 21, 343–372. doi: 10.1057/s41291-022-00186-2

Fu, X., Ran, Y., Xu, Q., and Chu, T. (2022). Longitudinal research on the dynamics and internal mechanism of female entrepreneurs' passion. Front. Psychol. 13, 1037974. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1037974

Gilal, F. G., Zhang, J., Gilal, N. G., and Gilal, R. G. (2018). Integrating self-determined needs into the relationship among product design, willingness-to-pay a premium, and word-of-mouth: a cross-cultural gender-specific study. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 11, 227. doi: 10.2147/PRBM.S161269

Gupta, R., Pandey, R., and Sebastian, V. J. (2021). International entrepreneurial orientation (IEO): a bibliometric overview of scholarly research. J. Bus. Res. 125, 74–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.12.005

Hair, J. F. Jr, Matthews, L. M., Matthews, R. L., and Sarstedt, M. (2017). PLS-SEM or CB-SEM: updated guidelines on which method to use. Int. J. Multiv. Data Anal. 1, 107–123. doi: 10.1504/IJMDA.2017.087624

Hamadneh, S., Hassan, J., Alshurideh, M., Al Kurdi, B., and Aburayya, A. (2021). The effect of brand personality on consumer self-identity: the moderation effect of cultural orientations among British and Chinese consumers. J. Legal Ethical Regul. Isses 24, 1.

Hemmert, M., Cross, A. R., Cheng, Y., Kim, J. J., Kotosaka, M., Waldenberger, F., et al. (2022). New venture entrepreneurship and context in East Asia: a systematic literature review. Asian Bus. Manag. 21, 831–865. doi: 10.1057/s41291-021-00163-1

Hou, B., Zhang, Y., Hong, J., Shi, X., and Yang, Y. (2023). New knowledge and regional entrepreneurship: the role of intellectual property protection in China. Knowl. Manag. Res. Pract. 21, 471–485. doi: 10.1080/14778238.2021.1997655

Huang, Y., An, L., Wang, J., Chen, Y., Wang, S., and Wang, P. (2021). The role of entrepreneurship policy in college students' entrepreneurial intention: the intermediary role of entrepreneurial practice and entrepreneurial spirit. Front. Psychol. 12, 585698. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.585698

Hurun.net. (2023). Hurun Global Rich List. Available online at: https://www.hurun.net/zh-CN/Rank/HsRankDetails?pagetype=global (accessed March 3, 2023).

Jafari-Sadeghi, V. (2020). The motivational factors of business venturing: opportunity versus necessity? A gendered perspective on European countries. J. Bus. Res. 113, 279–289. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.09.058

Jin, R., and Wang, X. (2022). “Somewhere I belong?” A study on transnational identity shifts caused by “double stigmatization” among Chinese international student returnees during COVID-19 through the lens of mindsponge mechanism. Front. Psychol. 13, 1018843. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1018843

Kang, C., Zhang, Z., and Xu, Z. (2021). Intergenerational support, female labor supply and gender wage Gap Convergence in China: a gender division perspective. Res. Finance Econ. 4, 124–138.

Kusa, R., Duda, J., and Suder, M. (2021). Explaining SME performance with fsQCA: the role of entrepreneurial orientation, entrepreneur motivation, and opportunity perception. J. Innov. Knowl. 6, 234–245. doi: 10.1016/j.jik.2021.06.001

Li, B., Guo, T., and Wu, Z. (2019). A study on consumers' willingness to participate in recycling idle goods from the perspective of self-construction. J. Manag. 5, 736–746.

Li, X., Liang, X., Yu, T., Ruan, S., and Fan, R. (2022). Research on the integration of cultural tourism industry driven by digital economy in the context of COVID-19—based on the data of 31 Chinese Provinces. Front. Public Health 10, 780476. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.780476

Liñán, F., Jaén, I., and Martin, D. (2020). Does entrepreneurship fit her? Women entrepreneurs, gender-role orientation, and entrepreneurial culture. Small Bus. Econ. 1–21. doi: 10.1007/s11187-020-00433-w

Luksyte, A., Bauer, T. N., Debus, M. E., Erdogan, B., and Wu, C. H. (2022). Perceived overqualification and collectivism orientation: implications for work and nonwork outcomes. J. Manag. 48, 319–349. doi: 10.1177/0149206320948602

Maunz, L. A., and Glaser, J. (2023). Does being authentic promote self-actualization at work? Examining the links between work-related resources, authenticity at work, and occupational self-actualization. J. Bus. Psychol. 38, 347–367. doi: 10.1007/s10869-022-09815-1

Murnieks, C. Y., Klotz, A. C., and Shepherd, D. A. (2020). Entrepreneurial motivation: a review of the literature and an agenda for future research. J. Org. Behav. 41, 115–143. doi: 10.1002/job.2374

Mustafa, M., and Treanor, L. (2022). Gender and entrepreneurship in the New Era: new perspectives on the role of gender and entrepreneurial activity. Entrep. Res. J. 12, 213–226. doi: 10.1515/erj-2022-0228

Ojong, N., Simba, A., and Dana, L. P. (2021). Female entrepreneurship in Africa: a review, trends, and future research directions. J. Bus. Res. 132, 233–248. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.04.032

Ramadani, V., Rahman, M. M., Salamzadeh, A., Rahaman, M. S., and Abazi-Alili, H. (2022). Entrepreneurship education and graduates' entrepreneurial intentions: does gender matter? A multi-group analysis using AMOS. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 180, 121693. doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2022.121693

Richter, N. F., Martin, J., Hansen, S. V., Taras, V., and Alon, I. (2021). Motivational configurations of cultural intelligence, social integration, and performance in global virtual teams. J. Bus. Res. 129, 351–367. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.03.012

Schmitz, P. G., and Schmitz, F. (2022). Correlates of acculturation strategies: personality, coping, and outcome. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 53, 875–916. doi: 10.1177/002230221221109939

Sedikides, C. (2021). Self-construction, self-protection, and self-enhancement: a homeostatic model of identity protection. Psychol. Inquiry 32, 197–221. doi: 10.1080/1047840X.2021.2004812

Shi, B., and Wang, T. (2021). Analysis of entrepreneurial motivation on entrepreneurial psychology in the context of transition economy. Front. Psychol. 12, 680296. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.680296

Simarasl, N., Tabesh, P., Munyon, T. P., and Marzban, Z. (2022). Unveiled confidence: exploring how institutional support enhances the entrepreneurial self-efficacy and performance of female entrepreneurs in constrained contexts. Eur. Manag. J. doi: 10.1016/j.emj.2022.07.003

Solesvik, M., Iakovleva, T., and Trifilova, A. (2019). Motivation of female entrepreneurs: a cross-national study. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 23, 27–32. doi: 10.1108/JSBED-10-2018-0306

Sun, X., He, J., Zhang, Y., and Ma, H. (2022). The formation and growth mechanism of entrepreneur cognition in international entrepreneurship. Sci. Res. Manag. 12, 144–153.

Tan, C. K., Liu, T., and Kong, X. (2022). The emergent masculinities and gendered frustrations of male live-streamers in China. J. Broadcast. Electr. Media 66, 257–277. doi: 10.1080/08838151.2022.2057501

Torres, L., and Rollock, D. (2004). Acculturative distress among Hispanics: the role of acculturation, coping, and intercultural competence. J. Multicult. Counsel. Dev. 32, 155–167. doi: 10.1002/j.2161-1912.2004.tb00368.x

VanderLaan, D. P., Skorska, M. N., Peragine, D. E., Coome, L. A., Moskowitz, D. A., Swift-Gallant, A., et al. (2022). “Carving the biodevelopment of same-sex sexual orientation at its joints,” in Gender and Sexuality Development: Contemporary Theory and Research (Cham: Springer International Publishing),491–537.

von Bloh, J., Mandakovic, V., Apablaza, M., Amorós, J. E., and Sternberg, R. (2020). Transnational entrepreneurs: opportunity or necessity driven? Empirical evidence from two dynamic economies from Latin America and Europe. J. Ethnic Migr. Stud. 46, 2008–2026. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2018.1559996

Wang, X., and He, Z. (2022). Male child-rearing participation, Family traditional cultural concepts and female labor supply. J. Central Univ. Finan. Econ. 9, 88–103.

Wang, Y., Liang, G., Li, A., and Wang, H. (2020). Research on the entrepreneurial learning process of family business successors: a multi-case study based on cultural framework transformation. Manag. World 36, 120–142.

Wang, Z., Gao, M., and Panaccio, A. (2021). A self-determination approach to understanding individual values as an interaction condition on employees' innovative work behavior in the high-tech industry. J. Creat. Behav. 55, 183–198. doi: 10.1002/jocb.444

Wang, Z., Lei, D., and Tang, M. (2020). Research on the relationship between entrepreneurial motivation, social patchwork and anti-poverty innovation performance of female social entrepreneurs. Finan. Theory Pract. 41,94–102.

Ward, C. (2020). “Models and measurements of acculturation,” in Merging Past, Present, and Future in Cross-Cultural Psychology (Garland Science),221–230.

Wikantiyoso, B., Riyanti, B. P. D., and Suryani, A. O. (2021). A construction of entrepreneurial personality tests: testing archetype personality inventory in entrepreneurship. Int. J. Appl. Bus. Int. Manag. 6, 1–13. doi: 10.32535/ijabim.v6i1.1085

Williams, N., Plakoyiannaki, E., and Krasniqi, B. A. (2023). When forced migrants go home: the journey of returnee entrepreneurs in the post-conflict economies of Bosnia and Herzegovina and Kosovo. Entrep. Theory Pract. 47, 430–460. doi: 10.1177/10422587221082678

Xie, X., and Wu, Y. (2021). Doing well and doing good: How responsible entrepreneurship shapes female entrepreneurial success. J. Bus. Ethics 1–26. doi: 10.1007/s10551-021-04799-z

Xie, Y. (2023). The impact of environmental advertising demands on residents' green consumption from the perspective of self-construction theory. Bus. Econ. Res. 5, 100–103.

Xu, X., Xu, Z., Lin, C., and Hu, Y. (2022). Confucian culture, gender stereotype and female entrepreneur: evidence from China. Appl. Econ. Lett. 1–11. doi: 10.1080/13504851.2022.2099796

Yu, X., and Liu, M. (2021). Relationship between human capital and technological innovation growth of regional economy and psychology of new entrepreneurs in Northeast China. Front. Psychol. 12, 1664–1078. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.731284

Zahra, S. A. (2021). International entrepreneurship in the post Covid world. J. World Bus. 56, 101143. doi: 10.1016/j.jwb.2020.101143

Zhang, J., and Zhou, N. (2019). The impact of work-family relationships on women's entrepreneurship: a theoretical framework. Econ. Manag. Rev. 35, 49–60.

Zhang, L., Rimsha, K., Mohsin, R., Noppadol, C., and Rehana, P. (2021). The impact of psychological factors on women entrepreneurial inclination: mediating role of self-leadership. Front. Psychol. 10, 796272. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.796272

Zhao, T., Zhang, Z., and Liang, S. (2020). Digital economy, entrepreneurial activity and quality development: empirical evidence from Chinese cities. Manag. Word. 10, 65–76.

Keywords: cultural orientation, cultural integration, female, returnee entrepreneurs, entrepreneurial motivation

Citation: Zhang Y (2023) The influence of cultural orientation on the entrepreneurial motivation of Chinese female returnee entrepreneurs—From the perspective of cultural integration. Front. Commun. 8:1190190. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2023.1190190

Received: 20 March 2023; Accepted: 25 July 2023;

Published: 22 August 2023.

Edited by:

Abdul Waheed Siyal, Nanjing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics, ChinaReviewed by:

Fahri Özsungur, Mersin University, TürkiyeCopyright © 2023 Zhang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yaqiong Zhang, enlxcWlhbnFpYW5AaG90bWFpbC5jb20=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.