- 1Department of Media & Communication, Erasmus University Rotterdam, Rotterdam, Netherlands

- 2Department of Community Psychology, FernUniversität in Hagen, Hagen, Germany

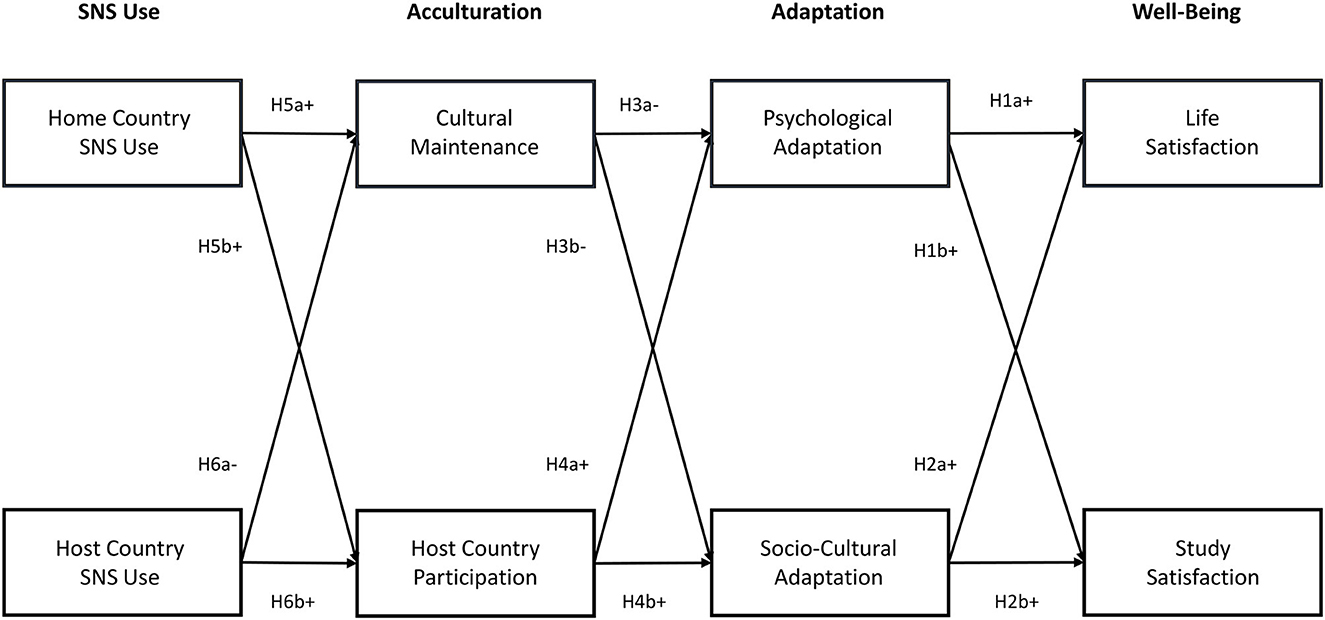

Introduction: A growing body of literature focuses on the impact of social media on well-being of international students. What remains understudied, is how these effects may be explained through acculturation and adaptation processes. This paper examines the mediating roles of acculturation dimensions (cultural maintenance and host country participation) and (psychological and sociocultural) adaptation, on the relationship between host and home Social Network Site (SNS) use and well-being, among two populations.

Methods: Hypotheses were tested using surveys distributed among a diverse group of international students in the Netherlands (n = 147) and a sample of Chinese students in Germany (n = 102).

Results and discussion: The results of both studies show that international students use SNS to initiate contact with the host society, which relates positively to adaptation. However, using SNS to stay in contact with the home culture appears to inhibit the adaptation process, which relates to lower well-being. Our work suggests that these processes are similar across different contexts.

1. Introduction

Over the past decades, higher education has globalized at a rapid pace (OECD, 2018; de Wit and Altbach, 2021). International mobility has been shown to enhance students' competence development (Netz, 2021; Hofhuis et al., 2023), employability (Nilsson and Ripmeester, 2016), and may contribute to the social and cultural development of society at large (Jones et al., 2021). However, there may also be drawbacks to studying abroad. On the dark side of what is typically considered an exciting and memorable life phase, international students may be exposed to stressors such as the loss of social support, difficulties adjusting financially as well as academically, language and cultural barriers, discrimination, and prejudice (Gautam et al., 2016). This has led to the finding that feelings such as loneliness and alienation are pervasive among this population (Sherry et al., 2010; Hendrickson et al., 2011). One of the factors that may protect international students from such negative outcomes is social support (Kuo, 2014; Bender et al., 2019).

The development and popularization of Social Network Sites (SNS) have greatly increased the opportunities that international students have to stay in contact with relations in the home country, as well as to initiate contact with individuals in the host society. A growing body of research focuses on how SNS contribute to the mobility experience (e.g., Hendrickson and Rosen, 2017; Pang, 2018; Gaitán-Aguilar et al., 2022). However, the question whether SNS are beneficial or detrimental for international students' wellbeing remains difficult to answer; social media use has been linked to positive outcomes such as social support and increased social capital (Billedo et al., 2020), as well as negative outcomes such as increased psychological alienation and loneliness (Hendrickson et al., 2011; Serrano-Sánchez et al., 2021).

To explain the divergent relationships between international students' SNS use and wellbeing, some prior studies examined the role of acculturation, focusing on how students relate to the home and host cultures (e.g., Hofhuis et al., 2019; Yu et al., 2019). Others focus on the way SNSs help international students adapt to living in a new cultural environment (e.g., Billedo et al., 2019; Gaitán-Aguilar et al., 2022). Acculturation and adaptation are related, but have been shown to be conceptually independent processes, which may together influence the wellbeing of international sojourners (see Bierwiaczonek and Kunst, 2021 for an overview). The first research question that is addressed in this study, therefore, is how acculturation and adaptation together may explain the relationship between SNS use and wellbeing.

Furthermore, literature reviews on sojourner wellbeing reveal that most study designs focus on a single group, or one specific context (Bierwiaczonek and Waldzus, 2016). The second research question that is addressed in this paper is whether the reported relationships between social media use, acculturation, adaptation, and wellbeing are generalizable across different populations. To answer this question we will test our hypotheses in two independent studies, among two different samples of students in higher education: (1) a culturally heterogeneous sample of international students in the Netherlands, and (2) a more culturally homogeneous sample of Chinese students in Germany. By doing so, we may provide insight into the robustness of the reported effects.

2. Theoretical background

2.1. International student wellbeing

International student wellbeing is a complex construct, that may include many different facets, often categorized into affective and academic wellbeing. Affective wellbeing can be broadly defined as “optimal psychological experience and functioning”, (Ryan and Deci, 2001, p. 142) or as the absence of negative constructs such as stress, loneliness, depression, or anxiety (Gong et al., 2010; Weinstein, 2018; Karsay et al., 2022). For the purpose of this study, we are interested in how different aspects of living abroad, and (digital) communication with important others during the sojourn, may relate to the overall wellbeing of international students. In line with previous work (Demes and Geeraert, 2015), we therefore operationalize affective wellbeing through the broad concept of life satisfaction, meaning an general state of feeling well in one's life (Lazarowitz et al., 1994; Diener et al., 2010).

Academic wellbeing refers specifically to the academic life domain, and can include constructs such as academic adjustment (Anderson et al., 2016; Forbush and Foucault-Welles, 2016) or variables related to performance or academic achievement (Rienties et al., 2012; Karpinski et al., 2013; Samad et al., 2019). In the context of the present study, we focus on the overall affective outcomes that international students experience while studying, and how this relates to their personal experiences in the academic context. As such, academic wellbeing is broadly operationalized as study satisfaction, defined as having positive overall perceptions of the academic environment (Lizzio et al., 2002).

2.2. Adaptation and outcomes

One of the most commonly reported predictors of international students' wellbeing is their level of adaptation to the new cultural environment (Bierwiaczonek and Waldzus, 2016). The consensus among scholars is that cross-cultural adaptation has two dynamic dimensions that develop over time: psychological and socio-cultural adaptation (Searle and Ward, 1990; Ward and Kennedy, 2001). Psychological adaptation refers to the individual's ability to cope with the psychological pressures of being abroad, and is usually examined from a stress and coping perspective. For example, international students may need to learn to deal with language barriers, perceived discrimination, and unfamiliar social norms (Ward and Kennedy, 2001; Smith and Khawaja, 2011; Szabó et al., 2020). Socio-cultural adaptation, often studied from a cultural learning perspective, refers to international students' ability to manage everyday tasks in the new social context. By identifying and internalizing the specific norms, values, and behaviors of the environment, students develop practical skills to navigate social interactions (Ward and Kennedy, 2001; Wilson et al., 2013; Szabó et al., 2020).

There is a myriad of empirical studies that show how both psychological and socio-cultural adaptation positively contribute to international students' affective wellbeing (see Brunsting et al., 2018 for an overview). Being able to speak, understand and communicate with locals in an appropriate manner, adapting fully to one's new environment, and successfully coping with the transition into the host society are variables that may lead to higher life satisfaction, lower stress levels, and higher overall happiness (Demes and Geeraert, 2015; Campos et al., 2022). Furthermore, although not as commonly studied, socio-cultural and psychological adaptation have also been related to positive academic outcomes of international students (Rienties et al., 2012; Anderson et al., 2016; Forbush and Foucault-Welles, 2016). We therefore hypothesize positive effects of both types of adaptation on affective as well as academic wellbeing.

H1. Psychological adaptation is positively related to (a) life satisfaction and (b) study satisfaction.

H2. Socio-cultural adaptation is positively related to (a) life satisfaction and (b) study satisfaction.

2.3. Acculturation and adaptation

Adaptation processes, as described above, may be better understood by also taking into account the students' acculturation process. In his guiding framework, Berry (2005) defines two acculturation dimensions that individuals have to navigate while abroad: Cultural maintenance reflects the extent to which one seeks to maintain one's heritage culture and identity, while Host country participation reflects the degree to which one seeks to become involved in the host country society, its people and customs (see also Berry, 1997; Berry and Sam, 1997). It is important to mention here that host country participation reflects migrants' intent to engage with home and host societies, which is conceptually different from the adaptation constructs mentioned above, which reflect one's ability to do so. Through a literature review, Smith and Khawaja (2011) confirm that both acculturation dimensions play an important role in international student adaptation.

Previous studies that examine the interplay between cultural maintenance and adaptation reveal both positive and negative effects. One the one hand, cultural maintenance is associated with increased interactions with similar others during the sojourn, which increases opportunities for receiving social support, thus enhancing higher psychological adaptation (Sullivan and Kashubeck-West, 2015; Bender et al., 2019). However, a growing number of studies shows that cultural maintenance may also lead international students to close themselves off to new intercultural experiences, thus inhibiting adaptation (e.g., Hofhuis et al., 2019; Serrano-Sánchez et al., 2021).

Host country participation has been shown to be a predictor of intercultural contact and identification with the culture of the host country (Li and Tsai, 2015), which in turn enhances adaptation (Demes and Geeraert, 2015). For example, among Swiss exchange students in the U.S. and New Zealand, positive contact with the host family predicted intentions to meet other host community members (Rohmann et al., 2014), and among Mainland Chinese university students in Hong Kong, a positive relationship is reported between home county participation and both socio-cultural and psychological adaptation (Ng et al., 2017).

In sum, we predict that cultural maintenance may inhibit psychological and socio-cultural adaptation, because it may reduce motivation and opportunities for intercultural contact. Conversely, we predict that the intent to participate in the host society is more helpful for the adaptation process of this particular group, by providing a motivation to engage in meaningful interactions with locals, and seek out new social contacts.

H3. Cultural maintenance is negatively related to (a) psychological and (b) socio-cultural adaptation.

H4. Host country participation is positively related to (a) psychological and (b) socio-cultural adaptation.

2.4. Social network sites and acculturation

Prior studies show that mediated intercultural contact may enhance participation in new social groups (Ferguson et al., 2016). SNS, in particular, appear to encourage contact among people and different cultures, which influences acculturation processes (Ju et al., 2021). For example, Forbush and Foucault-Welles (2016) show that Chinese students who used SNS often during their study abroad preparation had larger, more diverse social networks than students who used SNS less often. Yu et al. (2019) found that Chinese students use social media to seek advice from peer groups, which helps to ease their “culture shock” as well as find the best way to live in the new host environment.

However, we also see negative effects. Hofhuis et al. (2019) report that international sojourners in the Netherlands who use home country SNS are more likely to feel psychologically alienated, which in turn enhances cultural maintenance. Similarly, Allison and Emmers-Sommer (2011) report that ethnic communication on social media can distance immigrants from the host culture.

Based on previous findings, we hypothesize that use of home country SNS may enhance international student's cultural maintenance, while simultaneously providing a support network that may enhance their host country participation. Use of host country SNS is expected to negatively contribute to cultural maintenance, and directly enhance host country participation.

H5: Home Country SNS use is (a) positively related to Cultural Maintenance and (b) positively relate to Host Country Participation.

H6: Host Country SNS use is (a) negatively related to Cultural Maintenance and (b) positively related to Host Country Participation.

2.5. Social network sites and wellbeing—mediation effects

The aim of the present study is to integrate the different streams of research presented above, and examine whether the relationship between SNS use and wellbeing among international students may be explained through acculturation and adaptation processes.

Previous work has investigated the overall effects of SNS use on student wellbeing, providing mixed results (for a comprehensive review, see Oh et al., 2014; Erfani and Abedin, 2018; Weinstein, 2018). In the specific context of international student mobility, positive effects are reported, for example by Park et al. (2014), who found that Chinese and Korean international students in the US who used local SNS (i.e., Facebook) exhibited lower stress levels. Other studies show that Chinese international students who use SNS to create culturally diverse networks exhibited higher levels of academic wellbeing than students with less diverse networks (Forbush and Foucault-Welles, 2016; Pang, 2019), and that international students use the opportunities provided by SNS in the host country to achieve higher psychological wellbeing and life satisfaction (Pang, 2018).

In contrast, the abovementioned study by Park et al. (2014) also reports that co-ethnic social media use among Korean and Chinese international students is associated with higher levels of stress. Similarly, a study in the Netherlands suggests that increased contact with friends and family in the home country, through SNS, is related to feelings of loneliness and alienation, which may reduce wellbeing (Hofhuis et al., 2019).

To better understand these divergent findings, the present research examines whether direct relationships can be identified between home/host country SNS use and wellbeing, and whether these relationships are mediated through acculturation and adaptation processes that are described above.

2.6. Present research

Two studies will be presented, which test the conceptual path model that follows from our hypotheses (see Figure 1), among two different samples of international students: study 1 focuses on a diverse group of international students in the Netherlands, whereas study 2 focuses on Chinese students in Germany. Testing our hypotheses in these distinct contexts provides us with a unique opportunity to examine the same effects among two different populations, providing insights into the robustness and generalizability of the reported findings, over and above studies that focus on just one of populations.

3. Study 1

3.1. Methods

3.1.1. Procedure and sample

Study 1 tests our hypotheses among a sample of international students from different cultural backgrounds, enrolled in bachelor's or master's degree programs at institutes of higher education in the Netherlands. Students at both research universities (Universiteiten) and universities of applied science (Hogescholen) were included. At the time of research, 11.5% of students enrolled in Dutch universities originated from abroad, most commonly from Germany, Italy, China, Belgium and the UK (Nuffic, 2019). For a more comprehensive description of internationalization in the Dutch higher education context, please consult work by Condette and De Wit (2023). English is the default language of instruction for international students at Dutch universities, and before being allowed to enroll, proof of proficiency must be provided. Therefore, we assumed that respondents would be comfortable answering our questions in English.

An invitation to complete a digital survey was distributed through Facebook groups for international students in the Netherlands, and through academic networks of the researchers. In total, 147 respondents participated (61% female; Mage = 24.1; Range = 18–40; SD = 3.48; Average length of stay: 24.9 months). In total, 36 countries of origin were represented in the dataset. Most respondents came from Europe, with Germany (34.7%), France (4.7%), and Spain (4.7%) being the most represented. In total, 16.3% of students came from non-European countries, of which Indonesia (2.0%), Vietnam (1.3%), Brazil (1.3%), and South-Africa (1.3%) were most represented.

All respondents provided informed consent. The study meets all the criteria formulated by the Ethics Review Board of the first author's institution.

3.1.2. Measures

At the time of the study, Facebook was the most commonly used social network among this population (Hofhuis et al., 2019). As such, it was decided to operationalize SNS use through use of Facebook, measured using 10 items adapted from the scale by Junco (2012). Respondents reported how frequently they communicate with host country, as well as home country contacts on Facebook, through activities such as posting status updates, sharing links, sending private messages, etc., on a scale of 1 (never) to 7 (very often).

Acculturation dimensions were measured using two four-item subscales (Demes and Geeraert, 2014). On a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree), respondents reported their intended Cultural Maintenance (e.g., “I find it important to take part in the events and traditions of my home culture”) and Host Country Participation (e.g., “I find it important to take part in the events and traditions of the Netherlands”).

Psychological Adaptation was measured using a 7-item scale (Demes and Geeraert, 2014), asking adaptation experiences (e.g., “In the last two weeks, how often have you felt homesick when you think of your home country?”) on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never) to 7 (always).

Socio-Cultural Adaptation was measured using the Socio-Cultural Adaptation Scale (SCAS-R; Wilson et al., 2017). Respondents reported on their competence (1 = not at all competent; 7 = extremely competent) on 21 items, such as “Interacting at social events” and “Finding my way around”.

Life Satisfaction was measured with the Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS; Diener et al., 1985), consisting of five items (e.g., “I am satisfied with my life”) to be answered on a scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree).

Study Satisfaction was measured using three items adapted from the Michigan Organizational Assessment Questionnaire Job Satisfaction Subscale (MOAQ-JSS, as used by Bowling and Hammond, 2008), which were reformulated to measure respondents' contentment with academic life (e.g., “In general, I like studying here”) on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree).

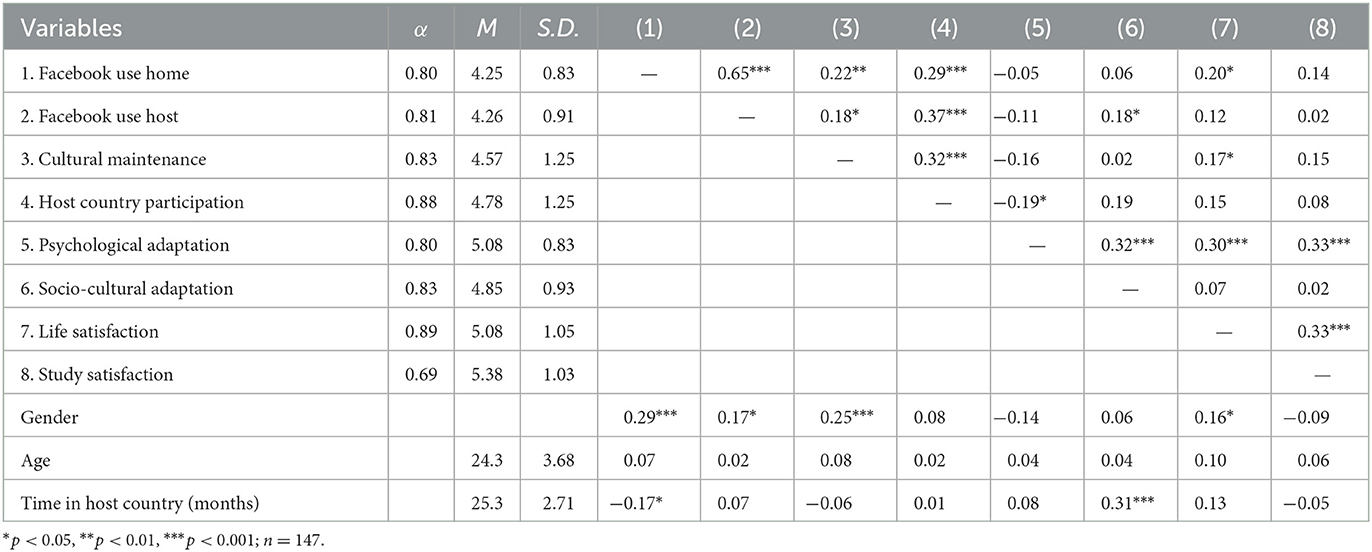

Covariates: Gender, age, and time in the host country were included as control variables. Reliability, descriptive statistics, and correlations for all study variables are shown in Table 1.

3.2. Results

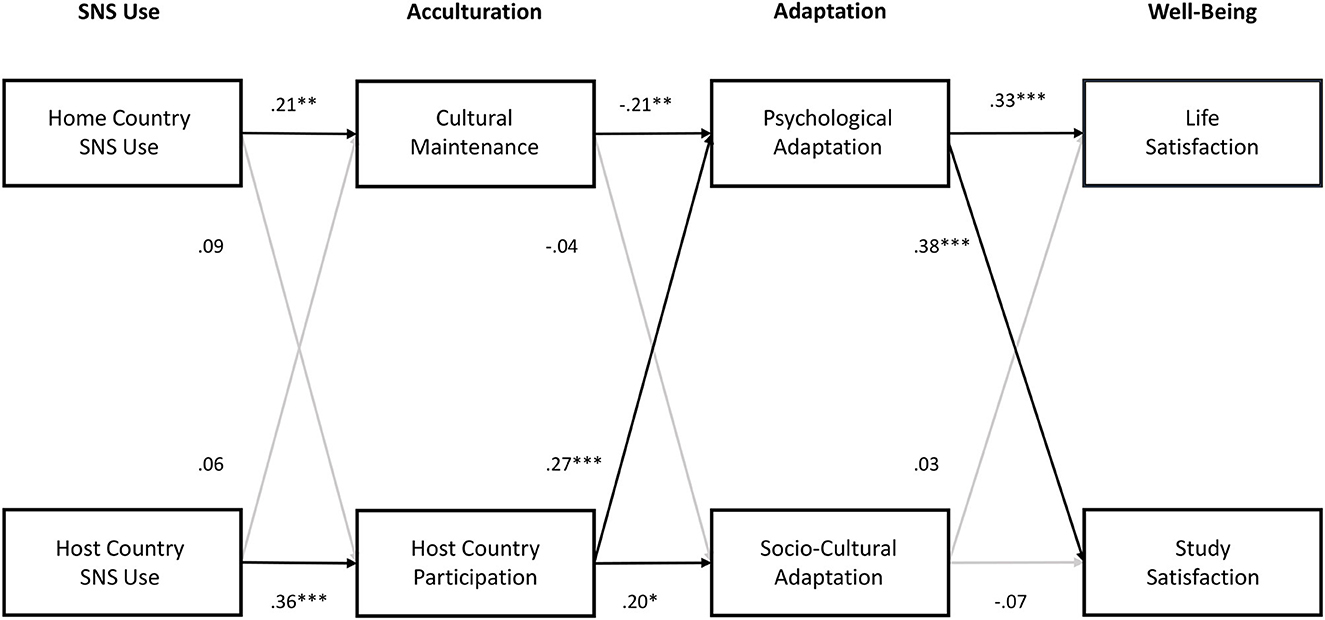

We constructed a model in MPlus 7 (Muthén and Muthén, 2015) based on the hypotheses outlined above. Ideally, all latent constructs would be estimated based on the individual items in the survey. However, because of the limited sample size, it was decided to reduce model complexity by entering mean scores of each construct as manifest variables. Control variables were included as predictors of the outcome variables. We used Full Information Maximum Likelihood (FIML) to account for missing data. The model exhibited a good fit with the data [X2(27) = 29.981; p = 0.32; CFI = 0.953; TLI = 0.955; RMSEA = 0.068]. Figure 2 displays the standardized estimates for the relationships between variables in the model.

Figure 2. Standardized estimates of relationships between SNS use, acculturation, adaptation and life/study satisfaction among international students in the Netherlands (n = 147). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

3.2.1. Adaptation and wellbeing

Our results confirm that psychological adaptation is positively related to both life satisfaction (b* = 0.33; p = 0.001) and study satisfaction (b* = 0.38; p = 0.001), confirming Hypotheses 1a and 1b. Socio-cultural adaptation was unrelated to both outcomes, prompting us to reject Hypotheses 2a and 2b.

3.2.2. Acculturation and adaptation

Cultural maintenance displayed a negative relationship with psychological adaptation (b* = −0.21; p = 0.010), confirming Hypothesis 3a. No relationship was found with socio-cultural adaptation, so Hypothesis 3b was rejected. The relationships between host country participation and both psychological (b* = 0.20; p = 0.012) and socio-cultural adaptation (b* = 0.36; p = 0.001) were found to be positive, confirming Hypotheses 4a and 4b.

3.2.3. SNS use and acculturation

Home country SNS use was positively related to cultural maintenance (b* = 0.21; p = 0.010), confirming hypothesis 5a. However, it did not have a significant relationship with host country participation, failing to confirm Hypothesis 5b. For host country SNS use, the opposite pattern emerged: no significant relationship was found with cultural maintenance, failing to confirm Hypothesis 6a, but a significant positive relationship was found with host country participation (b* = 0.36; p = 0.001), confirming Hypothesis 6b.

3.2.4. Mediations

We examined the direct effects of SNS use on wellbeing, and indirect effects through acculturation and adaptation, using bootstrapping (5,000 iterations; 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals).

For home country SNS use, we found a small yet significant negative indirect effect on life satisfaction, through cultural maintenance and psychological adaptation [b* = −0.02; p = 0.016; 95% CI (−0.06, −0.004)]. No direct effect was found, which means the relationship is fully mediated. No direct or indirect relationship was found between home country Facebook use and study satisfaction.

Host country SNS use displayed a small positive indirect effect on life satisfaction [b* = 0.04; p = 0.003; 95% CI (0.01, 0.08)], mediated through host country participation and psychological adaptation. Lastly, host country Facebook use also displayed a small positive indirect effect on study satisfaction [b* = 0.03; p = 0.012; 95% CI (0.01, 0.07)], again through host country participation and psychological adaptation.

The results described above will be interpreted below, in relation to the results obtained from study 2, in the general discussion section.

4. Study 2

4.1. Methods

4.1.1. Procedure and participants

Study 2 tested our hypotheses among a sample of Chinese international students enrolled in bachelor's or master's degree programs at German institutes of tertiary higher education. As in study 1, students of both research universities (Universitäten) and universities of applied science (Hochschulen) were included. At the time of data collection, 14.5% of students in German higher education were of foreign origin, of which Chinese students form the largest group (Statista, 2021). For a comprehensive description of internalization in German higher education, please consult earlier work by Gürtler and Kronewald (2015). Although the higher education system in Germany is structured in a similar way as in the Netherlands, some significant differences exist. Most importantly, in Germany, learning the local language is seen as an important aspect of being an international student, and many programs are only offered in German (Gürtler and Kronewald, 2015). Therefore, in study 2, extra care was taken to accommodate language differences and language fluency. Respondents were contacted through Chinese student associations in Germany, Chinese SNS chat groups (e.g., on WeChat), and referrals from lecturers. All respondents provided informed consent. The study meets the criteria set forth by the Ethics Review Board of the first author's institution. A total of 104 respondents participated in the study. Two respondents were removed from the sample, because they were not currently enrolled in an institute of higher education. As such, the final sample consisted of 102 respondents (54.9% Female; Mage = 23.78; Range = 20–46; Average length of stay: 24.1 months).

4.1.2. Measures

All measures were presented in simplified Chinese, German, and English. We chose to use scales for which validated English and German versions were available. When a Chinese version of a measure was not available, a back-translation method with committee resolution of discrepancies was used to prepare the translation (Sireci et al., 2006).

SNS Use: Since many international social network sites, such as Facebook, are not available to residents of China, we expected Chinese international students to make use of different platforms to stay in contact with the home country relations. As such, the variables for SNS use were operationalized differently to study 1. Chinese international students' use of Home (Chinese) and Host (German) SNS were measured with modified versions of the Facebook Intensity Scale (FIS; Ellison et al., 2007), adapted to measure overall use home or host country SNS platforms. It consisted of five items each (e.g., “Chinese/German SNS has become part of my daily routine”, “I feel out of touch when I haven't logged on to Chinese/German SNS for a while”). Participants responded on five-point scales ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

Acculturation was assessed using six items by Rohmann et al. (2006), including subscales for cultural maintenance (e.g., “I believe it is important that we Chinese keep up our way of life in Germany”) and host country participation (e.g., “I believe it is important that we Chinese have German friends in Germany”), rated on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree).

Psychological Adaptation was measured using the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS; Gong et al., 2010), consisting of 21 items (e.g., “I found it hard to wind down”), answered on a 4-point scale ranging from 1 (does not apply to me at all) to 4 (applies to me very much, or most of the time). Items were reversed to indicate psychological adaptation.

Socio-Cultural Adaptation was measured using the Socio-Cultural Adaptation Scale (SCAS-R; Wilson et al., 2017). Respondents reported on their competence (1 = not at all competent; 7 = extremely competent) on 21 items, such as “Interacting at social events” and “Finding my way around”.

Life satisfaction was measured using the Flourishing Scale (FS; Diener et al., 2010) consisting of eight items which ask respondents to rate their success in important life areas such as relationships, self-esteem, purpose, and optimism on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree).

Study Satisfaction was measured using nine items from the Academic Adjustment Scale (AAS; Anderson et al., 2016), such as “I expect to successfully complete my degree in the usual allocated timeframe”, on a scale ranging from 1 (never applies to me) to 5 (always applies to me).

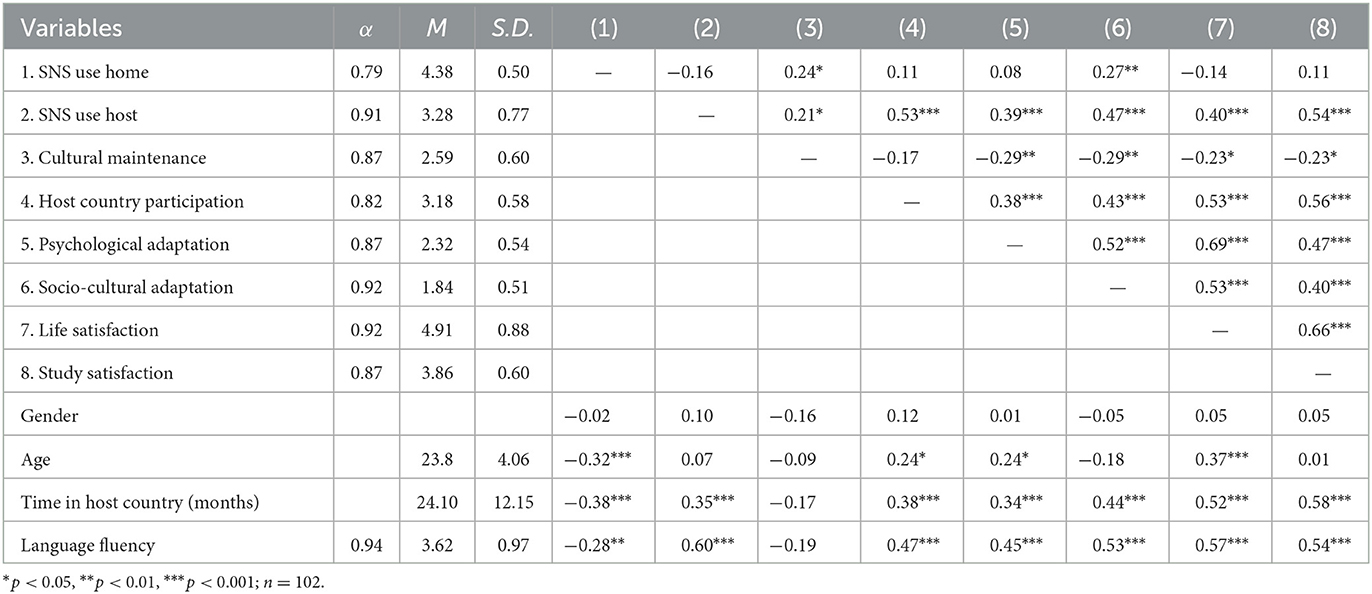

Covariates: As in Study 1, gender, age and time in the host country were included as control variables. Following Noels et al.'s (1996) suggestion that language self-confidence is a stronger predictor of acculturative outcomes than actual linguistic ability, German language efficacy was included as an additional control variable, measured using a 12-item scale by Clement and Baker (2001) in which respondents indicated language confidence (e.g., “I believe that I am capable of listening and understanding German very well”), rated on a five-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Descriptive statistics, reliabilities and correlations for all study variables and covariates are shown in Table 2.

4.2. Results

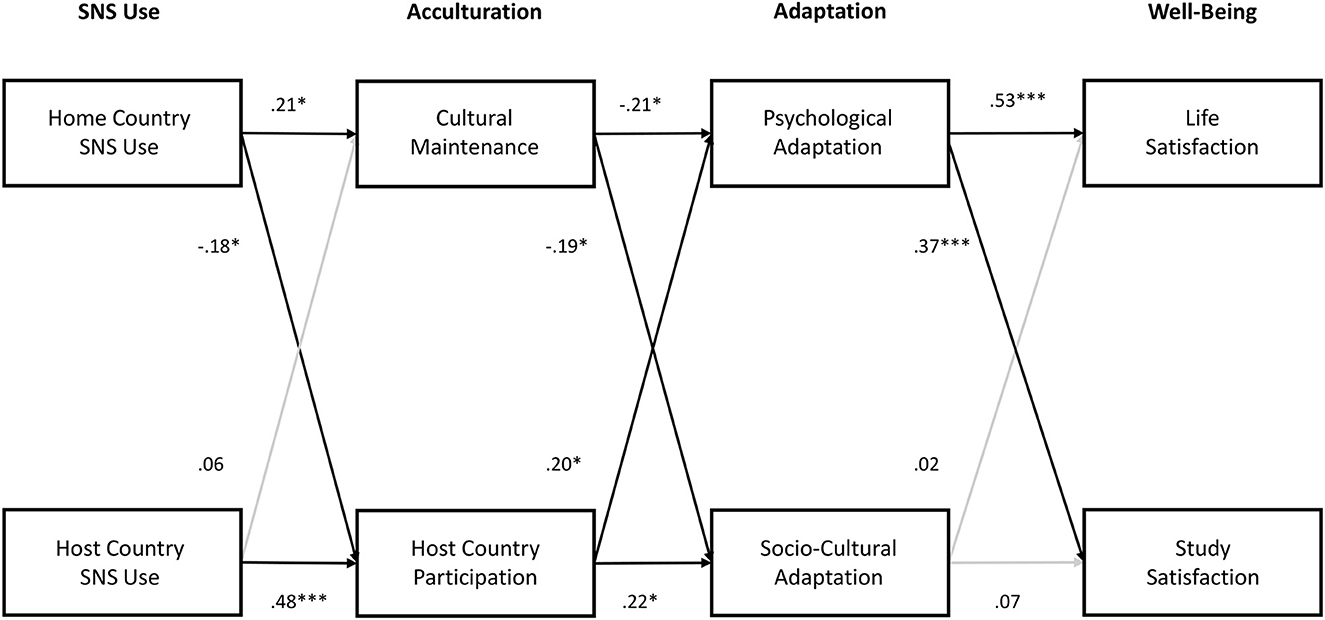

A model was constructed using the same procedure as in study 1, exhibiting adequate fit with the data [X2(32) = 26.817; p = 0.73; CFI = 0.963; TLI = 0.945; RMSEA = 0.083]. Figure 3 displays the standardized estimates of the relationships between the study variables in this model.

Figure 3. Standardized estimates of relationships between SNS use, acculturation, adaptation and life/study satisfaction among Chinese students in Germany (n = 102). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

4.2.1. Adaptation and wellbeing

Our results confirm that psychological adaptation is positively related to both life satisfaction (b* = 0.53; p < 0.001) and study satisfaction (b* = 0.37; p = 0.001), confirming Hypotheses 1a and 1b. Socio-cultural adaptation again seems unrelated to both outcomes, prompting us to reject Hypotheses 2a and 2b.

4.2.2. Acculturation and adaptation

Cultural maintenance exhibited a negative relationship with psychological adaptation (b* = −0.21; p = 0.014), again confirming Hypothesis 3a. A negative relationship was also found with socio-cultural adaptation (b* = −0.19; p = 0.031), confirming Hypothesis 3b. The relationships between host country participation and both psychological (b* = 0.20; p = 0.033) and socio-cultural adaptation (b* = 0.22; p = 0.016) were found to be positive, confirming Hypotheses 4a and 4b.

4.2.3. Host country SNS use and acculturation

As predicted in Hypothesis 5a, home country SNS use was positively related to cultural maintenance (b* = 0.21; p = 0.029). Contrary to expectations, a negative relationship was found with host country participation (b* = −0.18; p = 0.048), leading us to reject Hypothesis 5b. For host country SNS use, a significant positive relationship was found with host country participation (b* = 0.48; p < 0.001), confirming Hypothesis 6a. No significant relationship was found with cultural maintenance, thus we reject Hypothesis 6b.

4.2.4. Mediations

Finally, we examined whether home and host country SNS use are directly related to life and study satisfaction, and whether these relationships are mediated by acculturation and adaptation, using bootstrapping (5,000 iterations; 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals). No significant direct or indirect relationships were found for home country SNS use. However, we found a significant indirect relationship between host country SNS use and life satisfaction [b* = 0.09; p = 0.027; 95% CI (0.01, 0.19)], through host country participation and psychological adaptation. No direct effect was found, so the relationship is fully mediated. No direct or indirect effects were found on study satisfaction.

5. Discussion

5.1. Summary of findings

We examined the relationships of Social Network Sites (SNS) use with acculturation, adaptation, and wellbeing of two groups of international students, a culturally heterogeneous group of foreign students in the Netherlands, and a more culturally homogenous group of Chines students in Germany. In both samples, we found that host country SNS use is positively associated with life satisfaction, as predicted. Our data confirm that SNS contact with host country individuals increases participation in the host society, which in turn enhances psychological adaptation, in line with previous research (Forbush and Foucault-Welles, 2016; Pang, 2019, 2021). It also mimics findings reported for offline social networks (Geeraert et al., 2014), and other types of media (e.g., Allison and Emmers-Sommer, 2011; Sommier et al., 2019; Zerebecki et al., 2021), where similar effects are found.

In contrast, home country SNS use seems to have primarily negative effects. It predicts higher cultural maintenance, which in turn is associated with lower levels of psychological as well as socio-cultural adaptation. Moreover, among international students in the Netherlands, the more time spent on home country social media, the lower one's life satisfaction. These findings contradict earlier suggestions that international students may use SNS to gain social support from similar others (e.g., Billedo et al., 2019), and confirm negative effects reported in other empirical work (Hendrickson et al., 2011; Hofhuis et al., 2019), which suggests possible detrimental effects of SNS on international student wellbeing, if used primarily to maintain contact with home country relations.

An interesting finding that emerged in both models is that socio-cultural adaptation does not seem to contribute directly to wellbeing. For the Chinese sample, one explanation for this lack of a relationship could be that this variable does not explain variance over and above language fluency. Since language fluency could be interpreted as a necessary pre-condition for socio-cultural adaptation, it could be argued that language fluency is a more fundamental skill. For the sample of international students in the Netherlands, a possible explanation could be that many international students sojourn to the Netherlands primarily with the intention of obtaining a degree; socio-cultural adaptation may be less of a priority. However, for both samples, it is also possible that the influence of socio-cultural adaptation on wellbeing is mediated through the length of the sojourn. As time passes, international students may display increased adaptation, and enjoy higher satisfaction. As such, by controlling for this variable, the effects of socio-cultural adaptation may have become obscured. Further research is needed to better understand which of these possible explanations may account for these findings.

5.2. Theoretical implications

The obtained pattern of results holds implications for scholars interested in digital media use in the context of international student mobility. Our findings shed new light on the relationship between SNS use and wellbeing of international students, by showing that previously inconsistent findings (see Oh et al., 2014) may be contingent on the different type of contacts (home vs. host) that individuals interact with on SNS, and may be explained in part by how these online interactions affect acculturation and adaptation processes in different ways. As such, we recommend that future scholars take into account different contact groups when studying these phenomena (for examples, see Gaitán-Aguilar et al., 2022; Hofhuis et al., 2023).

Secondly, our findings across both studies speak to the overall generalizability of the reported effects of SNS use on wellbeing across different groups of students. Although previous scholars have suggested that adaptation process may be dependent on the cultural distance between home and host country (e.g., Geeraert et al., 2019), or that the different online platforms that are in use in different societies may have a differential impact (Pang, 2021; Vauclair et al., 2023), our work shows that the psychological processes that underlie the effects are in fact quite similar across different populations, and platforms. The congruence in the observed pattern of relationships among variables is remarkable, especially considering differences in operationalizations between the two studies, and provides a conceptual replication of the results across contexts. Of course, future research aiming to explore the similarities and generalizability of a general model of SNS use and wellbeing would benefit from including more diverse samples, in different educational contexts.

5.3. Limitations and future research directions

Although we tested our model with two samples, we were not able to provide a direct statistical comparison between estimated effects, due to differences in operationalization. To further strengthen the argument for generalizability, we encourage future scholars to conduct fully identical studies in different contexts, and conduct multiple group analyses (Van de Vijver and Leung, 1997). Furthermore, the samples of both studies were relatively small. We were able to reduce the complexity of the structural equation models by including the mean scores on each scale as manifest variables, which allowed us to reliably estimate the relationships between constructs. However, to capture the nuances contained within the individual items in the scales, we recommend replicating our results with larger samples.

Another limitation of the studies presented in this paper is their reliance on cross-sectional data. Although our mediation analyses assume a direction along the hypothesized paths, it is not unlikely that the relationships between the constructs in our model are reciprocal (Billedo et al., 2020; Gaitán-Aguilar et al., 2022). Future studies should seek to replicate our findings using a longitudinal design in order to better understand the direction of these effects.

Furthermore, the main outcome variables included in this work are relatively general constructs of wellbeing, including life and study satisfaction. The advantage of using such broad constructs, is that we were able to capture the overall effects of our predictors on international students' life experiences. However, this approach does not allow for a more fine-grained analysis of how these constructs affects different aspects of the life domain, such as mental health, social interactions, or academic performance. We hope future scholars may be able to include such variables in their work, to further tease out the nuances of relationships that are reported in this paper.

The goal of our research was to understand the impact of online contact, through social media, on acculturation, adaptation and wellbeing of international students. However, a large body of previous literature has shown that face-to-face contact may have a stronger impact on these variables than online contact. To further investigate the degree to which online contact plays a role over and above face-to-face, we recommend that scholars conduct more studies that compare the two (e.g., Billedo et al., 2019).

Finally, as mentioned above, an important variable in studying international student experiences is the degree of perceived cultural distance between the student and the host society. Even though our findings confirm that the processes involved are similar across different samples and contexts, future studies would benefit from more direct statistical approach to confirm these findings, or perhaps control for cultural variations in the data. Previous work (e.g., Bell et al., 2009; Geeraert et al., 2019) has made use of existing aggregated scores on cultural dimensions on the level of nations or regions to estimate cultural distance. However, we believe that this may obscure individual variance among respondents, and may not account for the notion that international students may not be a representative subsample of their home country (see also Yakunina et al., 2012). Instead, we recommend including an individual-level measure of perceived cultural distance in future studies, to be able to control for or examine its effects on international student adaptation and wellbeing.

5.4. Conclusions and practical implications

Our findings speak to potential that host country social media hold for easing the transition process for international students. We believe that it would be beneficial for both host and home institutions to offer services that enable students to make use of host social media while preparing for their exchange as well as during their time abroad. Not only could institutions set up their own social media accounts, they could also offer links to online applications and services that facilitate contact between local and foreign students. Next to introductory activities aimed at welcoming international students, they could provide links to online groups of international students or expats in the host city, that can offer informational social support if needed. Simultaneously, it would help for students to be made aware of the risks of relying solely on home country relations for social support or social capital, and instead open up to initiating new contacts in the host society. Our findings suggest that such activities may be effective in increasing wellbeing of international students, across different educational contexts.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because they contain data that may allow third parties to identify some of the participants. The data will only be made available for the purpose of verification. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to Erasmus University Rotterdam, ESHCC Ethics Review Board, ZXRoaWNzcmV2aWV3QGVzaGNjLmV1ci5ubA==.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

JH contributed to the design of study 1, data analysis of study 1 and 2, and drafting the manuscript. ME contributed to the design of study 2 and drafting the manuscript. FL contributed to design and data collection of study 1. KR contributed to design and data collection of study 2. AR contributed to the design of the study 2 and reviewed previous drafts of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Allison, M.-L., and Emmers-Sommer, T. M. (2011). Beyond individualism-collectivism and conflict style: Considering acculturation and media use. J. Intercult. Commun. Res. 40, 135–152. doi: 10.1080/17475759.2011.581033

Anderson, J. R., Guan, Y., and Koc, Y. (2016). The academic adjustment scale: measuring the adjustment of permanent resident or sojourner students. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 54, 68–76. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2016.07.006

Bell, A. V., Richerson, P. J., and McElreath, R. (2009). Culture rather than genes provides greater scope for the evolution of large-scale human prosociality. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106, 17671–17674. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903232106

Bender, M., van Osch, Y., Sleegers, W., and Ye, M. (2019). Social support benefits psychological adjustment of international students: evidence from a meta-analysis. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 50, 827–847. doi: 10.1177/0022022119861151

Berry, J. W. (1997). Immigration, acculturation, and adaptation. Appl. Psychol. Needham Heights: Allyn & Bacon. 46, 5–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-0597.1997.tb01087.x

Berry, J. W. (2005). Acculturation: living successfully in two cultures. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 29, 697–712. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2005.07.013

Berry, J. W., and Sam, D. L. (1997). “Acculturation and adaptation,” in Handbook of Cross-cultural Psychology: Social Behavior and Applications, eds J. W. Berry, Y. H. Poortinga, J. Pandey, M. H. Segall, and Ç. Kâgitçibaşi (Needham Heights: Allyn & Bacon), 291–326.

Bierwiaczonek, K., and Kunst, J. R. (2021). Revisiting the integration hypothesis: correlational and longitudinal meta-analyses demonstrate the limited role of acculturation for cross-cultural adaptation. Psychol. Sci. 32, 1476–1493. doi: 10.1177/09567976211006432

Bierwiaczonek, K., and Waldzus, S. (2016). Socio-cultural factors as antecedents of cross-cultural adaptation in expatriates, international students, and migrants: a review. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 47, 767–817. doi: 10.1177/0022022116644526

Billedo, C. J., Kerkhof, P., and Finkenauer, C. (2020). More facebook, less homesick? Investigating the short-term and long-term reciprocal relations of interactions, homesickness, and adjustment among international students. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 75, 118–131. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2020.01.004

Billedo, C. J., Kerkhof, P., Finkenauer, C., and Ganzeboom, H. (2019). Facebook and face-to-face: examining the short- and long-term reciprocal effects of interactions, perceived social support, and depression among international students. J. Comp. Mediat. Commun. 24, 73–89. doi: 10.1093/jcmc/zmy025

Bowling, N. A., and Hammond, G. D. (2008). A meta-analytic examination of the construct validity of the Michigan Organizational Assessment Questionnaire Job Satisfaction Subscale. J. Vocat. Behav. 73, 63–77. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2008.01.004

Brunsting, N. C., Zachry, C., and Takeuchi, R. (2018). Predictors of undergraduate international student psychosocial adjustment to US universities: a systematic review from 2009-2018. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 66, 22–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2018.06.002

Campos, J., Pinto, L. H., and Hippler, T. (2022). The domains of cross-cultural adjustment: an empirical study with international students. J. Int. Students 12, 422–443. doi: 10.32674/jis.v12i2.2512

Clement, R., and Baker, S. C. (2001). Measuring Social Aspects of L2 Acquisition and Use: Scale Characteristics and Administration. Ottawa: University of Ottawa.

Condette, M., and De Wit, H. (2023). “Shifting models and rationales of higher education internationalisation: the case of the Netherlands,” in Internationalisation in Higher Education: Responding to New Opportunities and Challenges. Ten years of research by the Centre for Higher Education Internationalisation (CHEI), F. Hunter, R. Ammigan, H. De Wit, J. Gregersen-Hermans, E. Jones, and A. C. Murphy (Milan: EDUCatt), 389–406.

de Wit, H., and Altbach, P. G. (2021). Internationalization in higher education: global trends and recommendations for its future. Policy Rev. High. Educ. 5, 28–46. doi: 10.1080/23322969.2020.1820898

Demes, K. A., and Geeraert, N. (2014). Measures matter: scales for adaptation, cultural distance, and acculturation orientation revisited. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 45, 91–109. doi: 10.1177/0022022113487590

Demes, K. A., and Geeraert, N. (2015). The highs and lows of a cultural transition: a longitudinal analysis of sojourner stress and adaptation across 50 countries. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 109, 316–337. doi: 10.1037/pspp0000046

Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., and Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. J. Pers. Assess. 49, 71–75. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13

Diener, E., Wirtz, D., Tov, W., Kim-Prieto, C., Choi, D., Oishi, S., et al. (2010). New well-being measures: short scales to assess flourishing and positive and negative feelings. Soc. Indic. Res. 97, 143–156. doi: 10.1007/s11205-009-9493-y

Ellison, N. B., Steinfield, C., and Lampe, C. (2007). The benefits of Facebook “friends:” social capital and college students' use of online social network sites. J. Comp. Mediat. Commun. 12, 1143–1168. doi: 10.1111/j.1083-6101.2007.00367.x

Erfani, S. S., and Abedin, B. (2018). Impacts of the use of social network sites on users' psychological well-being: a systematic review. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 69, 900–912. doi: 10.1002/asi.24015

Ferguson, G. M., Costigan, C. L., Clarke, C. V., and Ge, J. S. (2016). Introducing remote enculturation: learning your heritage culture from afar. Child Dev. Perspect. 10, 166–171. doi: 10.1111/cdep.12181

Forbush, E., and Foucault-Welles, B. (2016). Social media use and adaptation among Chinese students beginning to study in the United States. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 50, 1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2015.10.007

Gaitán-Aguilar, L., Hofhuis, J., Bierwiaczonek, K., and Carmona, C. (2022). Social media use, social identification and cross-cultural adaptation of international students: a longitudinal examination. Front. Psychol. 13, 1013375. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1013375

Gautam, C., Lowery, C. L., Mays, C., and Durant, D. (2016). Challenges for global learners: a qualitative study of the concerns and difficulties of international students. J. Int. Stud. 6, 501–526. doi: 10.32674/jis.v6i2.368

Geeraert, N., Demoulin, S., and Demes, K. A. (2014). Choose your (international) contacts wisely: a multilevel analysis on the impact of intergroup contact while living abroad. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 38, 86–96. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2013.08.001

Geeraert, N., Li, R., Ward, C., Gelfand, M., and Demes, K. A. (2019). A tight spot: how personality moderates the impact of social norms on sojourner adaptation. Psychol. Sci. 30, 333–342. doi: 10.1177/0956797618815488

Gong, X., Xie, X., Xu, R., and Luo, Y. (2010). Psychometric properties of the Chinese versions of DASS-21 in Chinese college students. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 18, 443–446.

Gürtler, K., and Kronewald, E. (2015). “Internationalization and English-medium instruction in German higher education,” in English-Medium Instruction in European Higher Education, eds S. Dimova, A. K. Hultgren, and K. Jensen (Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton).

Hendrickson, B., and Rosen, D. (2017). Insights into new media use by international students: implications for cross-cultural adaptation theory. Soc. Netw. 06, 81–106. doi: 10.4236/sn.2017.62006

Hendrickson, B., Rosen, D., and Aune, R. K. (2011). An analysis of friendship networks, social connectedness, homesickness, and satisfaction levels of international students. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 35, 281–295. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2010.08.001

Hofhuis, J., Hanke, K., and Rutten, T. (2019). Social network sites and acculturation of international sojourners in the Netherlands: the mediating role of psychological alienation and online social support. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 69, 120–130. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2019.02.002

Hofhuis, J., Jongerling, J., and Jansz, J. (2023). Who benefits from the international classroom? A longitudinal examination of multicultural personality development during one year of international higher education. High. Educ. doi: 10.1007/s10734-023-01052-6. [Epub ahead of print].

Jones, E., Leask, B., Brandenburg, U., and De Wit, H. (2021). Global social responsibility and the internationalisation of higher education for society. J. Stud. Int. Educ. 25, 330–347. doi: 10.1177/10283153211031679

Ju, R., Hamilton, L., and Mclarnon, M. (2021). The medium is the message: Wechat, youtube, and facebook usage and acculturation outcomes. Int. J. Commun. 15, 4011–4033.

Junco, R. (2012). The relationship between frequency of Facebook use, participation in Facebook activities, and student engagement. Comp. Educ. 58, 162–171. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2011.08.004

Karpinski, A. C., Kirschner, P. A., Ozer, I., Mellott, J. A., and Ochwo, P. (2013). An exploration of social networking site use, multitasking, and academic performance among United States and European university students. Comput. Human Behav. 29, 1182–1192. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2012.10.011

Karsay, K., Matthes, J., Schmuck, D., and Ecklebe, S. (2022). Messaging, posting, and browsing: a mobile experience sampling study investigating youth's social media use, affective well-being, and loneliness. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 41, 1493–1513 doi: 10.1177/08944393211058308

Kuo, B. C. H. (2014). Coping, acculturation, and psychological adaptation among migrants: a theoretical and empirical review and synthesis of the literature. Health Psychol. Behav. Med. 2, 16–33. doi: 10.1080/21642850.2013.843459

Lazarowitz, R., Hertz-Lazarowitz, R., and Baird, J. H. (1994). Learning science in a cooperative setting: academic achievement and affective outcomes. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 31, 1121–1131. doi: 10.1002/tea.3660311006

Li, C., and Tsai, W.-H. S. (2015). Social media usage and acculturation: a test with Hispanics in the U.S. Comput. Human Behav. 45, 204–212. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2014.12.018

Lizzio, A., Wilson, K., and Simons, R. (2002). University students' perceptions of the learning environment and academic outcomes: implications for theory and practice. Stud. High. Educ. 27, 27–52. doi: 10.1080/03075070120099359

Muthén, L. K., and Muthén, B. O. (2015). Mplus User's Guide. 7th ed. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén and Muthén.

Netz, N. (2021). Who benefits most from studying abroad? A conceptual and empirical overview. High. Educ. 82, 1049–1069. doi: 10.1007/s10734-021-00760-1

Ng, T. K., Wang, K. W. C., and Chan, W. (2017). Acculturation and cross-cultural adaptation: the moderating role of social support. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 59, 19–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2017.04.012

Nilsson, P. A., and Ripmeester, N. (2016). International student expectations: career opportunities and employability. J. Int. Stud. 6, 614–631. doi: 10.32674/jis.v6i2.373

Noels, K. A., Pon, G., and Clement, R. (1996). Language, identity, and adjustment: the role of linguistic self-confidence in the acculturation process. J. Lang. Soc. Psychol. 15, 246–264. doi: 10.1177/0261927X960153003

Nuffic (2019). Dutch Organization for Internationalization in Education. Available online at: www.nuffic.nl (accessed September 01, 2019).

OECD (2018). How is the tertiary-educated population evolving? Educ. Indicat. Focus Paris, 61. doi: 10.1787/a17e95dc-en

Oh, H. J., Ozkaya, E., and LaRose, R. (2014). How does online social networking enhance life satisfaction? The relationships among online supportive interaction, affect, perceived social support, sense of community, and life satisfaction. Comp. Hum. Behav. 30, 69–78. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2013.07.053

Pang, H. (2018). Exploring the beneficial effects of social networking site use on Chinese students' perceptions of social capital and psychological well-being in Germany. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 67, 1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2018.08.002

Pang, H. (2019). How can WeChat contribute to psychosocial benefits? Unpacking mechanisms underlying network size, social capital and life satisfaction among sojourners. Online Inf. Rev. 43, 1362–1378. doi: 10.1108/OIR-05-2018-0168

Pang, H. (2021). Unraveling the influence of passive and active WeChat interactions on upward social comparison and negative psychological consequences among university students. Telemat. Informat. 57, 101510. doi: 10.1016/j.tele.2020.101510

Park, N., Song, H., and Lee, K. M. (2014). Social networking sites and other media use, acculturation stress, and psychological well-being among East Asian college students in the United States. Comput. Human Behav. 36, 138–146. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2014.03.037

Rienties, B., Beausaert, S., Grohnert, T., Niemantsverdriet, S., and Kommers, P. (2012). Understanding academic performance of international students: The role of ethnicity, academic and social integration. High. Educ. 63, 6. doi: 10.1007/s10734-011-9468-1

Rohmann, A., Florack, A., and Piontkowski, U. (2006). The role of discordant acculturation attitudes in perceived threat: an analysis of host and immigrant attitudes in Germany. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 30, 683–702. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2006.06.006

Rohmann, A., Florack, A., Samochowiec, J., and Simonett, N. (2014). “I'm not sure how she will react”: predictability moderates the influence of positive contact experiences on intentions to interact with a host community member. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 39, 103–109. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2013.10.002

Ryan, R. M., and Deci, E. L. (2001). On happiness and human potentials: a review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 52, 141–166. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.141

Samad, S., Nilashi, M., and Ibrahim, O. (2019). The impact of social networking sites on students' social wellbeing and academic performance. Educ. Inf. Technol. 24, 2081–2094. doi: 10.1007/s10639-019-09867-6

Searle, W., and Ward, C. (1990). The prediction of psychological and sociocultural adjustment during cross-cultural transitions. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 14, 449–464. doi: 10.1016/0147-1767(90)90030-Z

Serrano-Sánchez, J., Zimmermann, J., and Jonkmann, K. (2021). Thrilling travel or lonesome long haul? Loneliness and acculturation behavior of adolescents studying abroad. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 83, 1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2021.03.014

Sherry, M., Thomas, P., and Chui, W. H. (2010). International students: a vulnerable student population. High. Educ. 60, 33–46. doi: 10.1007/s10734-009-9284-z

Sireci, S. G., Yang, Y., Harter, J., and Ehrlich, E. J. (2006). Evaluating guidelines for test adaptations: a methodological analysis of translation quality. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 37, 557–567. doi: 10.1177/0022022106290478

Smith, R. A., and Khawaja, N. G. (2011). A review of the acculturation experiences of international students. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 35, 699–713. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2011.08.004

Sommier, M., Van Sterkenburg, J., and Hofhuis, J. (2019). “Color-blind ideology in traditional and online media: towards a future research agenda,” in Mediated Intercultural Communication in a Digital Age, eds A. Atay, and M. U. D'Silva (Milton Park: Routledge), 1–15.

Statista (2021). Anzahl der ausländischen Studierenden an Hochschulen in Deutschland. Available online at: https://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/301225/umfrage/auslaendische-studierende-in-deutschland-nach-herkunftslaendern/ (accessed September 01, 2021).

Sullivan, C., and Kashubeck-West, S. (2015). The interplay of international students' acculturative stress, social support, and acculturation modes. J. Int. Stud. 5, 1–11. doi: 10.32674/jis.v5i1.438

Szabó, Á. Z, Papp, Z., and Nguyen Luu, L. A. (2020). Social contact configurations of international students at school and outside of school: implications for acculturation orientations and psychological adjustment. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 77, 69–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2020.05.001

Van de Vijver, F., and Leung, K. (1997). Methods and Data Analysis of Comparative Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Vauclair, C.-M., Rudnev, M., Hofhuis, J., and Liu, J. H. (2023). Instant messaging and relationship satisfaction across different ages and cultures. Cyberpsychology 17. doi: 10.5817/CP2023-3-8

Ward, C., and Kennedy, A. (2001). Coping with cross-cultural transition. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 32, 636–642. doi: 10.1177/0022022101032005007

Weinstein, E. (2018). The social media see-saw: positive and negative influences on adolescents' affective well-being. New Media Soc. 20, 3597–3623. doi: 10.1177/1461444818755634

Wilson, J., Ward, C., Fetvadjiev, V. H., and Bethel, A. (2017). Measuring cultural competencies: the development and validation of a revised measure of sociocultural adaptation. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 48, 1475–1506. doi: 10.1177/0022022117732721

Wilson, J., Ward, C., and Fischer, R. (2013). Beyond culture learning theory: what can personality tell us about cultural competence? J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 44, 900–927. doi: 10.1177/0022022113492889

Yakunina, E. S., Weigold, I. K., Weigold, A., Hercegovac, S., and Elsayed, N. (2012). The multicultural personality: does it predict international students' openness to diversity and adjustment? Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 36, 533–540. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2011.12.008

Yu, Q., Foroudi, P., and Gupta, S. (2019). Far apart yet close by: social media and acculturation among international students in the UK. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 145, 493–502. doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2018.09.026

Keywords: social network sites, social media, international students, acculturation, adaptation, wellbeing

Citation: Hofhuis J, van Egmond MC, Lutz FE, von Reventlow K and Rohmann A (2023) The effect of social network sites on international students' acculturation, adaptation, and wellbeing. Front. Commun. 8:1186527. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2023.1186527

Received: 14 March 2023; Accepted: 14 July 2023;

Published: 07 August 2023.

Edited by:

Jeneen Naji, Maynooth University, IrelandReviewed by:

Adriana Zait, Alexandru Ioan Cuza University, RomaniaFrancesca Giovanna Maria Gastaldi, University of Turin, Italy

Shu-Sha Angie Guan, California State University, Northridge, United States

Copyright © 2023 Hofhuis, van Egmond, Lutz, von Reventlow and Rohmann. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Joep Hofhuis, ai5ob2ZodWlzQGVzaGNjLmV1ci5ubA==

Joep Hofhuis

Joep Hofhuis Marieke C. van Egmond2

Marieke C. van Egmond2