94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Commun. , 01 September 2023

Sec. Visual Communication

Volume 8 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomm.2023.1172115

This article is part of the Research Topic The Power of Images: How They Act and How We Act with Them View all 6 articles

Introduction: As a relatively new and innovative form of digital communication and visual image, emojis, emoticons, and stickers are appreciated, yet criticised. Young people on social media have lost the traditional social etiquette and interpersonal networking skills, which is a challenge in itself. This study provides a better understanding of how young people engage and behave in diverse interpersonal contexts while utilising digital visual language.

Methods: This study contributes to digital anthography and social media studies, by conducting this study through interviews with 10 Generation Z young people from urban China and a 2-month-long participatory observation of three WeChat group chats.

Results: By examining how young people use WeChat visual language in relationships with their elders or superiors, equivalent peers and intimate lovers or friends, this study found that emoticons and stickers become virtual gifts, aesthetic identities and the affection language of Generation Z.

Discussion: This study contends that digital visual languages and new media do not alter human nature or ethical standards but rather provide new avenues for expression and empower human affective communication. Although the core of traditional etiquette is still being passed on and absorbed, its form has changed.

Li, a 23-year-old Chinese university student, told me, “Basically, whenever I use WeChat to communicate with people now, I use graphicons, and I feel that text alone cannot accurately convey my emotions.” Of the global online population, 92% use emojis (CMO, 2016), out of which 86% of users on Twitter alone are under 24 years of age (World Emoji Day, 2017). As a relatively new and innovative form of digital communication and digital visual image, graphicons carry Internet memes and user aesthetic preferences. Graphicons, which include emoticons, emojis and stickers (Herring and Dainas, 2017), are viewed as fun and light-hearted, adding colour to messages and are used randomly without much thought (Shah and Tewari, 2021). However, as they are increasingly used in “serious” situations, such as work and intergenerational relationships, the features of graphicons, such as childishness, unseriousness and vulgarity, are being criticised (Li, 2017; Luo, 2019). Graphicons users, especially young people who are more adapted to the digital era, are exploring ways to face and resolve this critique by discovering how to properly use social media visual languages in their daily experiences.

The meanings of digital visual languages are culturally specific (Seargeant, 2019), and users must adapt their use to different cultural contexts to achieve the best interpersonal communication and self-expression. China has a lengthy history and a culture of appreciating etiquette, and it has always been referred to as the “land of ceremonial and decorum” (Yang and Fan, 2021). However, Generation Z has strong individualism and is thought to have moved away from conventional social etiquette and rites (Zhai, 2001). According to the China Youth Daily poll (2010), only 16.1% of young people still observe traditional manners, and in a survey of 1,000 young people worldwide conducted by the UK market research firm OnePoll (2013), 77% of respondents felt that their social interaction skills had drastically declined due to their over-reliance on mobile phones and online communication, leading them to become rude. It was even pointed out that “young people are becoming socially inept as a result of their addiction to mobile devices” (Oriental daily, 2015). However, it is questionable whether young people have lost social rules and manners because they are overly dependent on online communication and new media.

This study conducted interviews with 10 young people from urban China and a 2-month participatory observation of three WeChat group chats. By examining how young people use WeChat graphicons, this study attempts to better understand how they engage and behave in diverse interpersonal contexts when utilising digital visual language. Following ethnography and interviews, this study discovered that young Chinese people utilise different grahicons to cope with various interpersonal situations while ensuring appropriateness and politeness. In almost all situations in which graphicons are used, they become a “virtual gift” to exchange and build connexions. When interacting with elders or superiors, to build an ideal personal image, young Chinese people are more reserved and formal and prioritise others' feelings over self-expression. When engaged in equivalent relations, they tend to seek more emotional empathy and self-expression to build their aesthetic identity. In intimate relationships, self-made stickers with lovers and friends are created to build shared and private memories. Graphicons and the cyberspace etiquette differ from traditional ritual forms, in that they are more invisible and unnoticeable, but they still follow the same core as traditional rituals. This study proposes that new media does not change human nature and ethical standards but provides new ways of expressing and empowering human affective communication. The findings of this study complement qualitative research and fieldwork in communication and digital anthropology regarding the impact of new media on interpersonal relationships among young people. In addition, they provide new perspectives for understanding Generation Z Chinese youth.

This study focuses on social media visual language and interpersonal relationships with the goal of conversing with or contributing to the research areas of digital anthropology and media communication studies (Miller and Wang, 2021). The advent of the digital age has led to the realisation that online behaviour is an important way of presenting and reflecting on the offline world and that the two spaces interact and transform with each other (Garcia et al., 2009). Digital anthropology applies ethnographic methods to the study of social media. “Our tradition of long-term ethnographic studies is vital because it gives time to build trust to be accepted within the private spaces where we can directly observe people using social media” (Miller and Wang, 2021); thus, scholars in this field have conducted comparative studies in different regions of the world and on various social media platforms to investigate the use and consequences of digital technologies. Projects such as “Why We Post” (Miller et al., 2016), research in Chinese factories (Wang, 2016), and rural towns (McDonald, 2016) have observed and analysed people's behaviour in using Chinese social media QQ and WeChat, exploring the relational networks and social culture of Chinese rural and township society.

As an important theory in social media anthropology, Daniel Miller and Jolynna Susanna's “theory of attainment” in Webcam provides the framework and guidance for this study: it means that “we view a new technology in terms of it facilitating our ability to attain something, rather than disrupting some prior holistic being” (Miller and Sinanan, 2014, p. 3). It can help this study on how digital visual language as a social media technique influence interpersonal relationships as Webcam focuses on close relationships, kinship and best friends (Miller and Sinanan, 2014). According to this theory, humans are not becoming more mediated but rather have had their latent potential realised with the advent of new media. This is in line with what is proposed in this study, graphicons are not a complete medium for weakening the manners and relationships of Chinese Generation Z but rather for promoting the extension of humanity and culture. First, the “theory of attainment” analyses people's new media practise through self-consciousness as Goffman (1975) coined the concept of facework to describe the sense of security and assurance that an individual feels during public social interaction with others. This provides the theoretical basis for the self-presentation approach of WeChat users in this study of graphicons; the second part of the “theory of attainment” is about intimacy, analysing how new media culturally create the conditions of feeling “natural and close” (Miller and Sinanan, 2014, p. 5). This viewpoint adds a cultural perspective to this analytical study on how online visual language can help online communication create intimacy. The third part of the theory concerns the sense of place and argues that instead of considering media as connecting separate locations, new media can be considered as places within which people live. This is inspiring to view graphicons not only as iconic symbols with different meanings but also as digital images that do things by their agency (Gell, 1998) and become a “virtual presence.” This is particularly helpful in section 3, which analyses self-made photographic stickers.

Generation Z includes individuals born from the mid-1990s to the late 2000s (Gentina and Parry, 2020), accounting for 30% of the global population and approximately 20% of the population in China (Bo, 2019). Such a large percentage of the population means that Generation Z has become an important part of the current society as China's young population continues to grow. This generation has distinctive behavioural trajectories, values and subcultures (Gentina and Parry, 2020).

These unique characteristics are related to their growth background, which includes four major aspects (Yang et al., 2020). First, Generation Z youth live in a more affluent environment (National Bureau of Statistics of China, 2001); second, they grew up in a period when social class mobility slowed down. Those at the bottom of the economic ladder found it more difficult to advance, whereas those at the top were more likely to stay there (Chen and Cowell, 2015). This means that it is difficult for Generation Z to change the class of their family of origin by their education or career development compared to their parents' generation. Third, they grew up with digital devices (Zhang, 2018), which makes Generation Z proficient in the use of digital products, assessing information on the Internet and expressing themselves personally and socially. Fourth, they mostly grew up in small families. The One-Child Policy from 1982 to 2015 was a half-century programme that included a minimum age for marriage and childbearing, a limit of two children for couples and minimum time intervals between births (Hvistendahl, 2017). As Generation Z members in China have mostly been raised in families with 3–4 people, they have greater attestation and voice at home (Zhang et al., 2017).

These contexts have naturally shaped the unique characteristics of Chinese Generation Z, who are accustomed to competition, keen on self-depreciation and available to express themselves. First, in the contexts of class entrenchment and material base abundance, parents in small Chinese families place more emphasis on their children's education to provide them with better education and careers. As this generation enters the workforce, the labour market becomes saturated, making it difficult for highly educated graduates to find well-paying jobs. Simultaneously, under the one-child policy, Generation Z shoulders the responsibilities and hopes of six adults, including their father, mother and four grandparents (Yang and Laroche, 2011). Under all these pressures, a subculture of irony and self-deprecation, also known as “sang(丧) culture,” has emerged among young people (Luo, 2019), which will be further analysed in section 5.1. However, while “sang(丧) culture” ostensibly presents a negative image of young people as unmotivated, in reality, China's Generation Z is also more outspoken in self-expression and seeking equal social relations. In the workplace, Generation Z youth care about work-life balance (Yang et al., 2020, p. 30), and in families, many Generation Z youth often talk to their parents about their innermost thoughts and feelings—an increase of 5.5% compared to Generation Y (Zhang et al., 2017).

Emotional and ethical relationships in China form a unique social etiquette. In ancient China, the five cardinal relationships (五伦) were those between father and son, husband and wife, brothers and sisters, ruler and subject, and friends. More detailed depictions of Chinese relationships can be found in the book Guanxixue (Yang, 2016). The relationship bases in urban society may be subsumed into the following categories: family and kinship, neighbours and native place ties, non-kinship relations of equivalent status and non-kinship, superior-subordinate relations. Family and kinship ties are obligation relationships based on a “giving and sharing” approach; relatives and “hometown acquaintance同乡” are closer and become a social resource for each other when they move to a city; non-relative peer relationships, such as classmates and friends, pose no personal political security risks because they do not work together or share common interests; thus, relationships are more relaxed and open. Finally, non-kinship superior-subordinate relations such as teacher-student, master-apprentice and leader-subordinate, which are not only “emotional affection” but also “political relationships” involving lesser degrees of affection.

WeChat, a smartphone-based social networking platform launched by the Chinese company Tencent in 2011, has powerful features such as instant, video, and language messaging, as well as a wide range of features to meet social needs, and virtual wallets (Wang, 2016, p. 35). As the most popular social media platform for the urban Chinese, WeChat has been used in a variety of life situations, such as work, family, romantic relationships, and friendship. According to the 2019 WeChat Annual Report (Beijing Daily, 2020), WeChat has more than 1.1 billion monthly active accounts.

According to the access method, digital visual languages on WeChat can be generally divided into four types (De Seta, 2018): (1) typographical emoticons, which are seldom used in recent years, such as the original “:)” (Gettinger and Koeszegi, 2015); (2) emojis, which come with mobile phone systems and employ the most accentuated symbols that are not platform-specific; (3) standard stickers preinstalled on the WeChat system, which can be used without additional downloads; and (4) custom sticker sets uploaded by designers through the WeChat emoji open platform; sets of stickers that can be downloaded by users according to their preferences; stickers sent by others and added by users; and stickers—as well as custom stickers—created and uploaded by the users themselves (Figure 1). With the technics development and diversification of that online visual language, recent communication, sociological and psychological research has disclosed how social media visual languages including emoticons, emojis and stickers satisfied users' different communication needs and their influence on users' interpersonal relationships.

Firstly, research on graphicons and intergenerational relationships shows that the use of graphicons can help older Chinese people bring intergenerational relationships closer and open a window on youth culture (Wang, 2016, p. 108). In addition, the semantic sticker design approach allows seniors to comprehend the emotions represented by stickers without the need for written descriptions, which helps them to efficiently engage with their friends, family, children, and grandchildren (Chen, 2020). Wang and Haapio-Kirk (2021) conducted comparative fieldwork in China and Japan and found that emojis are a form of etiquette that conforms to local social norms and can express difficult emotions; moreover, they observed an elderly person using three stickers to express a modest attitude of gratitude after receiving a compliment. Cui (2022) conducted experiments to study the different interpretations of ironic Internet graphicons between young and old Chinese individuals and found that younger and older persons' interpretations of ambiguous remarks based on emojis differed depending on the sender's age and the sender-receiver relationship.

Second, many scholars have examined the role of emotions in romantic relationships. The experiments conducted by Rodrigues et al. (2017) and Gesselman et al. (2019) suggest that computer-mediated communication can facilitate expressions of affection in romantic partners, convey important emotional messages to potential partners, and be associated with more successful intimate connexions. Subsequently, the use of emojis plays a significant role in sending and receiving sexually suggestive messages, and extraversion and casual partners use sexually suggestive emojis more frequently (Thomson et al., 2018).

Third, in a study on the relationship between graphicons and working and friendship, Stark and Crawford (2015) use Hochschild (1979) term “emotional labor” to suggest that the use of expressions not only provides humans with a more endearing and humane way of socialising, but it is also informational capital seeking to standardise emotions. Further, Rodrigues et al. (2022) found that emojis play a crucial role in online interpersonal communications between strangers and potentially shape the initiation of new relationships. In addition to the abovementioned studies discussing emojis and interpersonal relationships, research on the use of online emojis and young people's self-expression and interpersonal relationships shows that online visual language has high significance for young people in many regions of the world (Zhang, 2016; Ask and Abidin, 2018; Shah and Tewari, 2021; Smith and Linker, 2021).

Although various studies have discussed the role of graphicons in different relationships, longitudinal studies concentrating on the same subject group and examining multiple scenarios and reasons for the use of graphicons are lacking. These studies could generate a better understanding of the social logic behind the graphicons used. Although Wang and Haapio-Kirk (2021) refer to how Chinese and Japanese social etiquettes affect the use of graphicons by Japanese and Chinese elders, most studies have not based their analyses on regional or national social norms or cultural values. However, as discourse and communication styles are socialised by individuals and formed under the influence of various factors, such as class, culture and economy, the practice of graphicons can be used to understand a group's cultural and moral values, which can be further analysed in future studies on visual language. Besides, in previous research on graphicons, there are less articles talking about the custom stickers which including selfie stickers and stickers made from pictures took by users. By analysing those self-made visual languages in this research, we could better understand how personal images could help with the interpersonal communication.

This study used a combination of online and offline ethnographic methods, focusing on the qualitative research methods of participant observation and semi-structured interviews. Cyber-ethnographic fieldwork was conducted in two parts on WeChat (Kozinets, 1998 cited in Chen, 2019): (1) private one-on-one chats, and (2) public WeChat groups. In this research, the qualitative data included 10 participants' one-on-one online in-depth conversion, 142 WeChat emoticons, emojis and stickers, 7 private chat history, and 2 groups chat history.

For detailed interviews, 10 participants were recruited according to the target group of the study; they were all from a metropolis of China such as Shanghai, Shenzhen, and Beijing. These cities were chosen because they are economically and educationally developed areas of China, with a high penetration of electronic mobile devices and social media usage; thus, their inhabitants have a basic knowledge of graphicons and WeChat and comparatively high digital literacy. The average age of the participants was 23 years, with the oldest being 50 years and the youngest being 19 years. Their occupations included undergraduate and postgraduate students, employees of Internet companies, state-owned enterprises, university professor and self-publishers. The different types of employment organisations contribute to this study's understanding of young people's interpersonal behaviours in different work relationships. The 10 participants included a couple, a pair of friends and a mother and daughter, which effectively helped to understand and analyse the characteristics and role of the use of graphicons in different relationships. Additionally, even though the focus group was Chinese young adults, to obtain a multi-perspective view of the research group and to test the validity of the young participants' narratives, a post-70s Chinese university teacher was recruited for comparative analysis. Based on the above-mentioned literature review of the five cardinal social relationships among Chinese people, the interview questions were designed according to three main categories of interpersonal relationships in China: (1) blood relations and unrelated relationships with superiors; (2) distant relationships with peers (Internet friends, classmates etc.); and (3) intimate relationships with peers (lovers, best friends etc.). The questions asked participants about their strategies and considerations for using WeChat graphicons in three different relationships. The interview requires participants give examples of using and custom graphicons and provide corresponding images and chat transcripts for investigation.

For the participant observation, two WeChat groups of young Chinese people and one WeChat group of mostly post-70s people were combined to observe their graphicons usage behaviours for 2 months from June to August 2022. The three-group chats were a thesis support group of 22 master's graduates, a personal group of friends with 7 people, and a work group composed of 20 post-70s university teachers as a comparative group. In these public chat groups, the communication topics were broad and included academic studies, job applications, workplace relationships, romantic relationships and daily chores. At the start of data collection, the participants were asked for screenshots of their usual graphicons for content analysis. All materials used in this study were collected and analysed with the participants' consent.

Chinese kinship bonds are maintained by acts of giving and sharing (Yang, 2016, p. 112). And in the traditional ritual system, the treatment of kinship relationships between elders and children has more of the same behavioural logic as relationships between superiors and subordinates in working life, and this is closely related to ancient Chinese ethical philosophy. The patriarchal system is constructed on the basis of blood relations, taking the Confucian ethical framework of the Three Cardinal Guides and Five Constant Virtues (三纲五常) as an example: “king guides people, father guides son” (Li, 2001). In modern life, the Chinese uphold the same logic of etiquette, such as letting elders eat first and respecting their superiors at work, and these methods are also reflected in online communications. However, the use of graphicons in evident in more equal relationships between elders and children or between superiors and subordinates, reflecting a tendency to shift from serious relationships to relaxed friendships.

Graphicons, as a “virtual gift,” serve a similar purpose to the traditional exchange of material gifts to maintain a relationship and are used to achieve a more intimate relationship. Mauss (1967) argued that gifts can substitute or stand in for persons and thus can influence a person's reach, which is extended beyond their physical boundaries. Mauss (1967, p. 10–11) believed that ritual gift practise is based on three inseparable obligations: to give, accept, and reciprocate gifts.

The prerequisite for gift exchange is the shared recognition of a gift's value by recipients and senders. For both sides of the online chat, a unified aesthetic and cultural understanding of emoticon images becomes the recognition of the value of this “virtual gift” (Panoff, 1970). For example, in the chat between Wang and her aunt, who has kinship relation and is much older than her, as in Chinese family, older members are superior to younger members, Wang said she would infer her aunt's aesthetic tastes to use graphicons that are more in line with the aunt's preferences and thus be able to convey her emotions more accurately and show her respect: “My aunt is particularly fond of stickers with big flowers, which women of their age love, so I deliberately found some of these and sent them to her—she should feel very happy” (Figure 2).

Choosing graphicons that the other person is familiar with and prefers could reduce the necessity to decode differences and prevents misunderstandings from arising (Lu and Wang, 2018). “Older people are less familiar with online emojis than young people, and we should be more considerate of their feelings and show respect for them as well” (Miao, 23 years old).

Additionally, the exchange and circulation of stickers have helped break down the seriousness of the traditional hierarchy and have become a tool to facilitate barrier bridging. Li, a 23-year-old Chinese international student in the UK, relied more on online or video chats to communicate with her family. She is the only child in her family, and a small family of three allows her parents to have closer and more equal relationships. When they communicate online, her parents save many of the stickers Li sends them: “My parents also save my stickers and use them. I think it's good, I feel that they are quite young at heart. Just as if I were chatting with my friends” (Figure 3).

As discussed by Miller (2017), with the use of social media, traditional family relationships are beginning to shift from being dependent to being subsumed by family relationships, with friendship and affection becoming homogenised. Kinship itself is realigned to reflect what people in China and many others in the world now see as modern values of authenticity, informality, and sentiment as part of a liberal ethic of choice, which they believe is better expressed through the ostensibly voluntary nature of friendships (Miller, 2017). “Although sometimes they still send stickers that don't really fit my aesthetic or are ambiguous (smiley face/big red flower), I also explain to them what our young people understand by these graphicons and also show them how to save them” (Wang, 24 years old). This shows a shift to a prefigurative culture driven by the digital revolution, in which cultural transmission is predominantly from youth to the elderly (Mead, 1970).

During my observations, I found a specific category of graphicons that is used only in working scenarios to build self-image. Qiu is a 22-year-old who is preparing to join a state-owned enterprise in 2022. His usual stickers have a series of brand visual identity images designed by his enterprise, such as a small, orange lion; Qiu explained, “These are the stickers I searched for and purposely downloaded” (Figure 4).

Utilitarian downloads and the use of corporate intellectual property (IP) stickers are forms of emotional labour. Qiu added, “I would appear to have a greater sense of belonging and loyalty when using these stickers.” He also mentioned that these stickers are not used with people outside his company or who do not know his job, instead they are more of a presentation act to people within the organisation or to customers. Just like the forced greetings from fast-food workers, casual banter with Uber drivers, a flight attendant's fixed smile or the nurse patting a patient's arm before the needle goes in, these affective impulses lead to forms of “emotional competence,” as Illouz (2007) points out—another form of work that employment gives beyond substantive action.

In addition to company intellectual property stickers, the use of “belief stickers” also helps to create an ideal personal image in an organisation. Zhou, a 24-year-old who works in the Party branch at the university, mentioned that he often uses stickers of the Chinese Communist Youth League, which are linked to his own beliefs. He is a member of the Communist Party of China (CPC) and believes that the Party's goal is to serve the people, and he also wants to establish himself as a helper in the minds of others. In this case, IP stickers could be associated with it. “I think using the Communist stickers really helps me to show my qualities of helpfulness and integrity” Zhou said, “Using these stickers will give me a good image of my classmates and teachers and I think it will help me with my studies and work” (Figure 5).

As Goffman (1975) dramaturgy theory suggests, people behave differently in different situations in their daily lives based on cultural values, social etiquette and expectations of each other, similar to theatrical performances. In this case, people display their ideal image when using a particular graphicon based on the recipient's knowledge of the graphicon's content, which illustrates young people's identity politics in the digital age.

The relationships between managers and workers, leaders, and work-unit members are more prominent than kinship, which is always motivated by instrumental and politicised considerations (Yang, 2016, p. 119). Compared to the random use of stickers, utilitarian, deliberately downloaded stickers are less functional in terms of communication but more about self-imaging in terms of demonstrating desirable personal characteristics. As Mestrovic (1997) argued, in a “post-emotional society,” emotions exist as a resource to be manipulated in the effort of self-presentation, and the accumulation of this personal image is influenced by wider political beliefs and socio-economic relations. In these two cases, when participants use stickers, they do not bring themselves into the graphicon image but become the collective image of the organisation, and users are the actors in the collective image and will.

Among young people, graphicons have become a social currency—a way of expressing taste, giving emotional value and carrying social traces. Unlike communication in a hierarchical relationship, which is more concerned with others' propriety and feelings, equal friendships have no political security risks (Yang, 2016, p. 116). Communication with peers is more open and relaxed, focusing on the expression of individuality and the search for emotional resonance. In such an egalitarian homogenous communication environment, people's opinions and cultural awareness can be displayed without concealment, which helps to observe the values, aesthetic identities and even the solidified prejudices of youth groups with graphicons.

Graphicons as a social currency have become a means for young people to create a sense of community (Ask and Abidin, 2018) and gain empathy and a sense of assemblage from their peers. Many Chinese scholars have argued that graphicons have become tools for embodying and disseminating youth subcultures; taking “Sang(丧) Culture” as an example, the word “sang(丧),” in Chinese is a multi-sense word, which can be used for matters related to the deceased and funerals and also means “loss, bad luck, and depression” (Min and Zhi, 2019). It was popular in the post-90s and some of the post-80s and has become an online expression of young people's flirtation with the work and life environment under high societal pressure (Luo, 2019). Rather than being an outlet for negative emotions, “sang” culture is more likely a self-deprecation to create phatic communication (Miller, 2008). Among the 10 participants who were recruited, the “sang” stickers appeared very frequently, and participants said that these graphicons are particularly useful in different chat situations (Figure 6), except with elders or superiors.

However, a significant difference exists between the content of graphicons and the actual behaviour of users. When a WeChat group of 22 UCL master's students studying for their dissertations was observed, they posted their study plans and outcomes daily. One phenomenon that was noticed was the high-frequency use of self-deprecating graphicons in the WeChat group; as stated by one group member, “Sending some ‘sang' graphicons is sometimes just to lighten the mood and to make everyone relax a bit” (Figure 7).

Joining a WeChat group for thesis improvement is a positive, enterprising act in itself, but group members often use “negative” visual language; this contrast between online representation and reality reflects the daily challenges that go beyond online representations of suffering (Dobson, 2016, p. 179), and the making and sharing of memes is a way to make and negotiate collective identities through shared norms and values (Gal et al., 2015, cited in Ask and Abidin, 2018).

China's younger generation has experienced unprecedented pressure for further education and employment (Yang et al., 2020, p. 30). The “sang” culture of self-deprecation has become a window for them to dissipate their anxiety and confront the dominant culture, isolating their daily lives from brutal social competition as well as from their peers (Szablewicz, 2014, p. 259). The use of suicide/death graphicons is a humorous critique of reality for the Millennial generation, which weakens the psychological trauma of the actual problem. Suicide modalities exemplify the inauthentic relationship between everyday life and death, and Heidegger (2008) refers to using the allusion to suicide/death in emojis to demonstrate the inauthenticity of death in everyday expressions. Memes and graphicons have become a reconciliation of reality (Smith and Linker, 2021) and have also created emotional empathy among peers (Xie, 2017).

Based on the above cases, although most Chinese scholars view “sang” culture in young people's online expressions as a sub-cultural element that leads to depression in youth and has a negative impact, I find that “sang” culture and other online memes shared by youth, which are humourous and less connected to how they act, to be virtual social strategies. However, this weakens sensitive topics in communication. Students use humour to express, share, and empathise with everyday struggles, emphasising the use of specific dialects through visual discourse and humour, where issues related to gender, race, orientation, class, and ability are set aside (Ask and Abidin, 2018); this makes them show a less aggressive image to their peers. To some extent, this has a positive effect on building friendships. For young people, real, competitive, and studious behaviour is a need to integrate into mainstream society and face challenges, whereas the virtual expression of memes and graphicons is a means of confronting mainstream culture and integrating with their peers.

In addition to the subculture that influences the use of graphicons among youth, the graphicon user's gender influences the aesthetics and preference for graphicons (Shah and Tewari, 2021). Additionally, as people use stickers according to their gender, this process re-instantiates gender roles. Accordingly, the gender norm in online visual language practise influences the relationships between sender and recipient, and people use the pictorial properties of online visual language to make predictions about the user's personalities, online habits and interpersonal networks, thus having different interpersonal interactions. In the fieldwork of this study, it was found that females preferred to use cute stickers, such as animals and cartoons, with their friends, but males preferred humorous, spoof and network-popular memes (Figure 8).

Excluding the personal factors of personality and aesthetic preferences, this phenomenon is also related to masculinity and femininity in social norms. In line with the gender norm in conventional culture, for young females, such a preferred style shows the “feminine” identity and encourages them to build their image as caregivers or supporters of their friends (Chen, 2019). In the Chinese tradition, women are expected to be caregivers, and tenderness and empathy are considered their best qualities (Chen, 2019); thus, they are influenced by these traditional beliefs and use visual languages with cute, emotional stickers to present the ideal “caregiver” image.

In contrast, young men use fun and fast-style memes to gain better positions in friendships (especially with men). In China, the “ethic of brother” always refers to the tight bonds of mutual aid, trust, and loyalty that exist between male friendships. “Brothers” share both good times and personal tragedies because they have the desire and obligation to help one another in times of need (Yang, 1994, p. 120). Relationships based on shared pleasures and hobbies make young men inclined to display humor, playfulness, and straightforwardness when communicating (Chen, 2016, p. 6). Such behaviours and attitudes profoundly reproduce masculine ideologies in their WeChat friendship interactions.

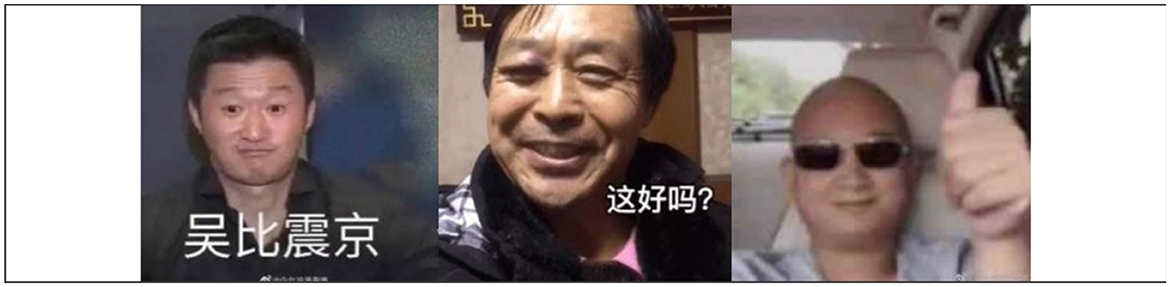

The masculine and feminine graphicons aesthetic described above reflect socially conscious approaches to online communication, which is also a reinforcement of gender stereotypes. For example, in an interview, outgoing and humorous 21-year-old Li mentioned that she likes to surf the Internet and use fun stickers, such as pictures of popular male comedians (Figure 9).

Figure 9. Jing Wu, Baoguo Ma and Brother Giao memes. They are three popular comedians and internet celebrities among young Chinese people.

“When I used stickers of Giao or Wu Jing (Figure 8), I was called ‘funny girl' by boys. Although I don't find it offensive, guys do not seem to be called ‘funny men' when they use these graphicons” Li expressed with a puzzled face. When women use comical, playful, or sexually suggestive stickers, they are seen as “undesirable women” from the male perspective. Thus, the use of stickers and jokes on the Internet has become a male prerogative, while women are excluded. This bias, in turn, cements gender norms and influences the value judgements and behaviours of men and women. The aesthetic of graphicons use among peers has gender-specific attributes shaped by social norms that influence people's interactions. People participate in personal packaging for online communication using graphicons that correspond to idealised gender identities. However, stickers also re-instantiate gender stereotypes. Even though Generation Z is less influenced by conventional gender definitions, they still live in this indurated social cognition system and must follow this habitus. This indicates that graphicons are becoming a conservative social tool by which people present the ideal gender identities and further reinforce gender norms.

Self-made stickers, which are a series of stickers created by creators or users, are notable. The function of creating users' own stickers make WeChat's visual language even more customised and facilitates unique personal communication (Hong, 2018). As a way of image reproduction, people always use their own or close friends' pictures to engage in phatic communication (Miller, 2008).

By sending an image of oneself rather than a photo or cartoon downloaded from the Internet, the capability to convey an emotional attachment is enhanced. Selfie stickers carry more personal biometrics than text and regular stickers, which makes the recipient feel more intimate and real and saves more time than Facebook and voice messages. In addition, the process of making self-made stickers by recording a video or capturing a picture of someone and reproducing them is more procedural and rewarding than sending regular stickers, and it shows more emotional attention.

Liu (female, 23 years old) and Qiu (male, 23 years old) fell in love at university and had been together for over 4 years. In 2022, they went to the UK and Singapore to study for their master's degrees. With busy school schedules and reluctance to rely on each other too much, they rarely used Facetime or made phone calls. As WeChat instant messages were most frequently used between Liu and Qiu, stickers played an important role in their affective communication. In this case, Liu created selfie stickers from her video clips and sent them to Qiu (Figure 10): “By making stickers with my own image and sending them to my date, I feel it better reflects my yearning for him, and it adds to the romance between us.”

Self-made stickers are another genre of selfies (Miller, 2015), but this kind of photography ranges from memorialisation to communication. The WeChat technique supports the reproduction of these stickers, and in 2018, WeChat added a new selfie graphicons option in the latest version 6.7.3 to support the re-creation of stickers for images (Wang, 2018). WeChat has added a function which allows users to record short videos or manually upload photos as graphicons, which can then be saved in their graphicons libraries for later use. Taking selfies with a smartphone and importing them into apps to create stickers is entwined with social media skills and knowledge (Latour, 1990). As many approaches to visual image in anthropology consider the relationships between the image as a form of representation and the people who have produced it (Miller et al., 2016, p. 157), the selfie-sticker creation process can help to open the black box of technology and investigate action motivation and implicit claims (Coupaye, 2022, p. 4). The steps to make selfie-stickers are generally five (Figure 11).

Through Liu's description of the various steps of making self-stickers and the revelation of their psychological factors, a personal representation based on social norms and the recipient's predictions of the graphicons is embodied. First, the choice of photo effect in step 2 to be more “girly and lovely” is in line with the reference to graphicons as a conservative social tool for gender identity in section 2.2 of this paper. In addition, self-stickers become “works of art” with a sense of personhood. Art objects are indices of the artist's or model's agency (Layton, 2003); thus, photography, philtres and effects are indices of people's agency and can be seen as a form of “distributed personhood” (Gell, 1998). As Schacter (2008) analysis about icon clash suggests, wherever the artist has been or imprinted themselves upon, they accordingly leave an element of their self. Selfie stickers can also be seen as agents for people, greeting and caring for their partners. The graphicon becomes an index of the user—a type of digital presence—when the creator sends their selfie stickers to another person. This artistic reproduction deepens the sense of participation and presence in online communication and reduces the sense of inauthenticity and distance associated with virtual chats.

In addition to using selfies as stickers, young people are keen to use photographs of their close friends as stickers, which are mostly funny and embarrassing pictures. Zhou is a 24-year-old product manager in Shanghai. He is outgoing and loves making friends, often taking photos of them (most of which are “ugly”) and making stickers with funny text to send to them. “I feel like it is a way of documenting life, I guess. Recording happy moments with friends” Zhou stated. He showed me a couple of stickers he had made for his friend Qiu, a college classmate with whom he eventually formed a business and became very good friends. One of the stickers had Qiu smoking a cigarette by the side of the road while looking quite worn out, with the text “So bored.” Zhou and Qiu snapped this picture while taking a break from a work project and thought that the expression reflected their mood at the time. When he sent it to Qiu as a sticker, Qiu did not get angry or offended.

“The people I dare do this (using ugly photos as stickers) with must be those with whom I feel really close and who do not mind me mocking their pictures” (Zhou, male, 24 years old). First, this rapport is based on popular self-deprecating humour among young people. “Joking” has become an important measure of affection in peer friendships; when a person is allowed to tease another person, it means that they are accepted as a closer friend (Yang, 2016). How teasing is received depends on the relationship between the people. When individuals already have an established friendship, teasing is more likely to be perceived as fun because there is time to develop an understanding of each other's humour and personality (Haugh, 2011). The graphicon humour between friends visualises this teasing and becomes a tangible test mark of affection. Second, stickers presume privacy as they are only seen by the recipients (Miller, 2015). People would not send these stickers to anyone other than close friends without their permission, so as to not damage the reputation and impression of the person photographed. Based on the agreement of deprecating humour and privacy conventions, the friend-made sticker becomes a recognition and honouring gift for young people.

Sending and checking out stickers in WeChat can be compared to the opening gifts ritual in traditional gift exchange ceremonies. Henaff and Doran (2013, p. 18) argues that “ceremonial gift-giving is primarily a procedure of public and reciprocal recognition among groups within traditional societies.” It is believed that gift-giving has the same sense of recognition as social network graphicons in modern society. Posting and using friend-stickers goes through the process of “identifying, accepting, and honouring,” which proves that the sticker maker has permission to “joke” with his friends. This demonstrates the creators' identity and serves as evidence of their friendship. Compared to the material-based gift exchange rituals of traditional societies, digital emoji exchange rituals are simpler and less visible, with both givers and receivers recognising each other's actions by default. Reciprocating occurs when the owner of the friend-stickers takes the initiative to use them or creates more playful stickers for their friend, going through the giver's preconceptions, judgments, and expectations of the friendship relations from the photoshoot to the edit and to the accompanying text. This unsophisticated, invisible process reveals the subtle, stress-free ways in which young people today communicate affectionately, using humour to reduce the pressure and coercion that come with close relationships.

This study faced limitations of a small sample size, low sample diversity and limited observation time; therefore, the data collected, and conclusions drawn were limited. The online fieldwork for this study was conducted over a period of 2 months through the observation of three WeChat groups joined mainly by young people, who were introduced to the group by close acquaintances, and therefore lacked in representativeness of those observed. This study also used semi-structured interviews to understand the motivations and social factors behind the use of graphicons by young people in China; however, the interview format was limited by the fact that the analysis was conducted only through the material provided by the interviewees and their oral experiences. Therefore, the information obtained was rather flat and did not fully reflect the phenomenon of graphicon use that the study intended to explore, which can be remedied by designing participatory experiments in future research to observe participants' emoji use in the field. Finally, although the participants were selected from as many different categories as possible (work, gender, living area etc.), they were mostly recruited from their own social network or by snowball sampling to find people recommended by the participants, who, therefore, had more overlapping social experiences, educational experiences and living environments. Therefore, the diversity of the sample observed in this study is limited and could be increased in the future by recruiting participants from a wider social group.

Although this is an ethnographic and interview-based study focusing on Generation Z in China, it does not exclude the possibility that other age groups in China share the same graphicons practices and motivations, such as older but more trendy people. As Bourdieu (1977) proposes that social groups with similar socio-cultural capital share “habitues,” this paper prefers to attribute the graphicon norm and “netiquette” (Scheuermann and Taylor, 1997) to the class identity, upbringing and educational and cultural background of the study group, rather than being limited to people's biological age.

The usage of graphicons by young people is driven by social variables, as I indicated in this study, but it is also a social media activity that is strongly influenced by personalities and cannot be attributed only to external factors such as social norms and subculture. In the interviews, many participants mentioned that graphicon usage habits are strongly linked to personal factors and are changeable; therefore, personal agency plays an important role in digital visual language usage. Social structures have power over people, such as cultural meaning and historical economic base; however, people also have agency as intentions and desires that must be balanced in theory. In this case, a subjective understanding of the actions of individuals is required (Weber, 1922, p. 15).

Most of the findings in this study, refer to graphicons as a tool to enhance relationship connexions; however, it is undeniable that the overuse and misuse of graphicons have some negative aspects. First, the repetition of the same popular graphicon in multiple social scenarios has lost its unique emotionality (Gao, 2021). Participant Wang, a 49 years old university teacher, mentions that when there were no WeChat and graphicons, “many of my students would write me ‘thank you' letters upon graduation; nowadays, they send a ‘thank you' sticker, which is also sent to others. I cannot feel as deep a teacher-student bond as before.” Second, young people today are less able to use text, and graphicons have become a simpler and more brutal way of expressing their affection. Zhou, 24 years old, said, “You just click on it, you don't have to edit the text. It's actually a very lazy process for the sender, to put it bluntly.” Third, as mentioned in Section 2.1, stickers exacerbate social identity perceptions and prejudice. People make identity judgments based on graphicons used by another person in the chat, and stickers have become a conservative social tool.

The internet and electronic devices have changed the behaviour of young people in the Generation Z era, and communication on social media has become ubiquitous. The diversity of formats, not limited by time and space, allows applications such as WeChat, WhatsApp, Instagram, and many other instant messaging software (IMS) to support online social interaction (Lee and Lin, 2019). Emoticons, emojis, and stickers can be saved, sent, and circulated on social media platforms, indicating social trends. As McLuhan (1964) puts that each new medium changes people's thinking and behavioural habits and accepts and expands human functioning; thus, the intervention of a new medium—visual language—has led to many communication and sociological studies identifying the role of visual language in human communication, social relations, and personal expression.

This study suggests that graphicons are viewed as virtual gifts to achieve a form of netiquette. They have become tools for the maintenance, recognition, and enhancement of the social relationships of Chinese Generation Z youth. The scenarios for graphcion use are broad and this study presents three types of relationships according to the Chinese interpersonal network: kinship and non-kinship superior-subordinate relations, equivalent relations and intimate relations. In the first section on superior-subordinate relations, such as kinship and workplace subordination, the absence, exchange, and utilitarian deliberate download of graphicons can strengthen intergenerational and workplace relationships while maintaining power distance and hierarchical relationships. In the second section on equivalent relations, based on young people's social norm expression habits and gender perceptions, self-deprecating visual languages, such as “sang” graphicons, are used as tools to demonstrate empathy and emotional resonance. Young people use different types of stickers to identify the user's gender and their digital trace. In the third section on intimate relations the use of self-made stickers for couples, best friends, and pet photography are analysed, where the creation of stickers becomes a private language representing recognition between the sender and the recipient. This study summarises graphicon use strategies and preferences by categorising Chinese young people's interpersonal relationships. The characteristic of Chinese Gen Z, such as high digital literacy, being born into a small family, highly competitive study and work and being bolder to express emotions are also reflected in the use of digital language. Furthermore, subdivided studies focusing on a particular network of relationships can be introduced in future research, such as an ethnographic study of the use of emojis for young people's intimate relationships, and cross-cultural comparative studies, such as a comparative study of young people's online expressions in China and the UK.

According to Horst and Miller (2020), “Digital Anthropology is insightful to the degree that it reveals the mediated and framed nature of the non-digital world.” A question for consideration in this study is how one perceives visual language when they cannot ignore its presence in communication and the extent to which one reshapes their perceptions of ritual, identity, gender and so on. Has the Internet completely erased traditionally perceived rituals from the lives of young people? The discussion in this study and the ethnography show that the core of traditional Chinese social etiquette and social norm are still being passed on and followed, but the forms have changed and are now more difficult to observe. It is not that individuals have necessarily “lost” their morals, instead these morals have simply undergone a change (McDonald, 2016, p. 117). In line with the key theory of attainment of Miller and Sinanan (2014), new media do not change the nature of being human. When faced with the intervention of new technologies, digital visual language cannot simply be seen as beneficial or harmful, just like the Internet or social media; the focus is on human initiative and agency, which refer to how people choose to use these digital tools in their lives and see the offline world from those graphicons interactions.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

The studies involving humans were approved by UCL Departmental Ethics Committee. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

This article was conducted by sole author. RL is in charge of all works of this article from study design to submission.

I sincerely thank everyone who supported me during the research. I wish to express my gratitude to Dr. Schacter Rafael, for his advice and help in selecting the subject, research methods, and theoretical components and for motivating me to continue and improve the writing of this article. I would also like to thank everyone who participated in this study. This investigation would not have been feasible without the accounts and material you provided me.

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Ask, K., and Abidin, C. (2018). My life is a mess: Self-deprecating relatability and collective identities in the memification of student issues. Inf. Commun. Soc. 21, 834–850. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2018.1437204

Beijing Daily (2020). 2019 WeChat data report released! The most popular sticker is ta. Available online at: https://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1655239864263192784andwfr=spiderandfor=pc (accessed September 20, 2022).

Bo, X. (2019). China's generation Z outshines global peers in boosting consumption: Report. Available online at: http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2019-01/30/c_137787306.htm (accessed July 22, 2022).

Bourdieu, P. (1977). Outline of a Theory of Practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 78–79. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511812507

Chen, C. P. (2016). Playing with digital gender identity and cultural value. Gender Place Cult. 23, 521–536. doi: 10.1080/0966369X.2015.1013455

Chen, C. P. (2019). Friendships through the style choice of virtual stickers: Young adults manage aesthetic identity and emotion on a social messaging line app. Int. J. Market Res. 63, 236–250. doi: 10.1177/1470785319844153

Chen, C. Y. (2020). “Research on Sticker Cognition for Elderly People Using Instant Messaging,” in Cross-Cultural Design. User Experience of Products, Services, and Intelligent Environments, eds. P. L., Rau (Cham: Springer). doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-49788-0_2

Chen, Y., and Cowell, F. A. (2015). Mobility in China. Rev. Income Wealth 63, 203–218. doi: 10.1111/roiw.12214

CMO (2016). Infographics: 92% of world's population use emojis. Available online at: https://www.cmo.com/features/articles/2016/11/21/report-emoji-used-by-92-of-worlds-online-population.html#gs.QbVpuubO (accessed September 20, 2022).

Coupaye, L. (2022). “Making Technology Visible: Technical Activities and the Chaîne Opératoire: Technique,” in The Palgrave Handbook of the Anthropology of Technology (Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore) 37–60. doi: 10.1007/978-981-16-7084-8_2

Cui, J. (2022). Respecting the old and loving the young: Emoji-based sarcasm interpretation between younger and older adults. Front. Psychol. 13, 897153. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.897153

De Seta, G. (2018). Biaoqing: The circulation of emoticons, emoji, stickers, and custom images on Chinese digital media platforms. First Monday. 23, 9391. doi: 10.5210/fm.v23i9.9391

Dobson, A. S. (2016). “Girls'‘Pain Memes” on YouTube: The Production of Pain and Femininity on a Digital Network,” in Youth Cultures and Subcultures (London: Routledge) 173–182. doi: 10.4324/9781315545998-16

Gal, N., Shifman, L., and Kampf, Z. (2015). ‘It gets better': Internet memes and the construction of collective identity. New Media Soc. 18, 1698–1714. doi: 10.1177/1461444814568784

Garcia, A. C., Standlee, A. I., Bechkoff, J., and Cui, Y. (2009). Ethnographic approaches to the internet and computer-mediated communication. J. Contemp. Ethnogr. 38, 52–84. doi: 10.1177/0891241607310839

Gentina, E., and Parry, E. (2020). “Generation Z in Asia: a research agenda,” in The New Generation Z in Asia: Dynamics, Differences, Digitalization (United Kingdom: Emerald Publishing). doi: 10.1108/9781800432208

Gesselman, A. N., Ta, V. P., and Garcia, J. R. (2019). Worth a thousand interpersonal words: Emoji as affective signals for relationship-oriented digital communication. PLoS ONE 14, e0221297. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0221297

Gettinger, J., and Koeszegi, S. T. (2015). “More than words: The effect of emoticons in electronic negotiations,” in International Conference on Group Decision and Negotiation 289–305. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-19515-5_23

Haugh, M. (2011). “Humour, face and im/politeness in getting acquainted,” in Situated Politeness 165–184. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511977886.009

Heidegger, M. (2008). “Being and Time,” in HarperPerennial/Modern Thought, eds. J. Macquarrie and E. Robinson 236–260.

Henaff, M., and Doran, R. (2013). Living with Others: Reciprocity and Alterity in Lévi-Strauss. Yale French Stud. 123, 63–82.

Herring, S. C., and Dainas, A. (2017). “Nice picture comment! Graphicons in Facebook comment threads,” in Proceedings of the Fiftieth Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (Los Alamitos, CA: IEEE Press) 2185–2194. doi: 10.24251/HICSS.2017.264

Hochschild, A. R. (1979). Emotion work, feeling rules, and social structure. Am. J. Sociol. 85, 551–575.

Hong, T. (2018). Wechat can take selfie emoticons! See which updates you can use. Available online at: http://life.cyol.com/content/2018-09/28/content_17637023.htm (accessed July 22, 2022).

Horst, H. A., and Miller, D. (2020). Digital Anthropology. Abingdon, Oxon, UK: Routledge, Taylor and Francis Group. doi: 10.4324/9781003085201

Hvistendahl, M. (2017). Analysis of China's one-child policy sparks uproar. Science 358, 283–284. doi: 10.1126/science.358.6361.283

Kozinets, R. V. (1998). “On netnography: Initial reflections on consumer research investigations of cyberculture,” in Advances in consumer research, eds. A. W., Joseph, W. J., Hutchinson (Ann Arbor, MI: Association for Consumer Research) 366–371.

Latour, B. (1990). Technology is society made durable. Sociol. Rev. 38, 103–131. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-954X.1990.tb03350.x

Layton, R. (2003). Art and agency: a reassessment. J. R. Anthropol. Inst. 9, 447–464. doi: 10.1111/1467-9655.00158

Lee, W., and Lin, Y. (2019). Online communication of visual information. Online Inf. Rev. 44, 43–61. doi: 10.1108/OIR-08-2018-0235

Li, N. (2017). Emoji: Happy for you, worry for you ——A study on the use of emoji among teenagers. J. Shandong Youth Univ. Polit. Sci. 6, 54–61. doi: 10.16320/j.cnki.sdqnzzxyxb.2017.06.010

Li, X. (2001). The Three Cardinal Guides and the Five Constant Virtues and Chinese Traditional Politics. Beijing: Shehui Kexue Ban. 25–31.

Lu, Y., and Wang, S. (2018). A study on the influence of the use of human emojis on the perception of intergenerational communication. Southeast Commun. 2, 69–71. doi: 10.13556/j.cnki.dncb.cn35-1274/j.2018.02.023

Luo, H. Z. (2019). Memes: the participatory expression of “memes” – take the incident of “Di Ba Chu zheng” as an example. Media Forum 23, 173–175.

Mauss, M. (1967). The gift: Forms and functions of exchange in archaic societies, transation Ian Cunnison. Norton 22, 55.

McDonald, T. (2016). Social Media in Rural China: Social Networks and Moral Frameworks. UCL Press. p. 234.

Mestrovic, S. G. (1997). Postemotional Society. London: SAGE Publications Ltd. doi: 10.4135/9781446250211

Miller, D. (2017). The ideology of friendship in the era of Facebook. J. Ethnogr. Theory. 7, 377–395. doi: 10.14318/hau7.1.025

Miller, D., Costa, E., and Haynes, N. (2016). How the World Changed Social Media. London, UK: UCL Press. doi: 10.2307/j.ctt1g69z35

Miller, D., and Wang, X. (2021). Introduction: Smartphone-based visual normativity: Approaches from digital anthropology and communication studies. Global Media China 6, 251–258. doi: 10.1177/20594364211036337

Miller, V. (2008). New media, networking and phatic culture. Convergence 14, 387–400. doi: 10.1177/1354856508094659

Min, L., and Zhi, T. (2019). Discourse creation and emotional realization of youth's “Sang” culture. Contemp. Youth Res. 4, 57–63.

National Bureau of Statistics of China (2001). China Statistical Yearbook. Beijing, China: China Statistics Press.

OnePoll (2013). Smartphones and social media are making young people rude. Available online at: https://wenku.baidu.com/view/c94a120f0912a2161479295a.html?_wkts_=1692602368562andbdQuery= (accessed September 20, 2022).

Oriental daily (2015). Young people become phubbers who are not good at communication and ignore etiquette. Available online at: https://www.orientaldaily.com.my/news/central/2015/12/16/118142 (accessed September 20, 2022).

Rodrigues, D., Lopes, D., Prada, M., et al. (2017). A frown emoji can be worth a thousand words: Perceptions of emoji use in text messages exchanged between romantic partners. Telem. Inf. 34, 1532–1543. doi: 10.1016/j.tele.2017.07.001

Rodrigues, D. L., Cavalheiro, B. P., and Prada, M. (2022). Emoji as icebreakers? Emoji can signal distinct intentions in first time online interactions. Telem. Inf. 69, 101783. doi: 10.1016/j.tele.2022.101783

Schacter, R. (2008). An Ethnography of Iconoclash: An Investigation into the Production, Consumption and Destruction of Street-art in London. J. Mater. Cult. 13, 35–61. doi: 10.1177/1359183507086217

Scheuermann, L., and Taylor, G. (1997). Netiquette. Internet Res. 7, 269–273. doi: 10.1108/10662249710187268

Seargeant, P. (2019). “People, politics and interpersonal relationships,” in The Emoji Revolution: How Technology is Shaping the Future of Communication (Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press) 116–135. doi: 10.1017/9781108677387.006

Shah, R., and Tewari, R. (2021). Mapping emoji usage among youth. J. Creat. Commun. 16, 113–125. doi: 10.1177/0973258620982541

Smith, N., and Linker, S. (2021). Suicide-memes as exemplars of the everyday inauthentic relationship with death. Mortality 26, 408–423. doi: 10.1080/13576275.2021.1987668

Stark, L., and Crawford, K. (2015). The conservatism of emoji: Work, affect, and communication. Soc. Media 1, 205630511560485. doi: 10.1177/2056305115604853

Szablewicz, M. (2014). The “losers” of China's Internet: Memes as structures of feeling'for disillusioned young netizens. China Inf. 28, 259–275. doi: 10.1177/0920203X14531538

Thomson, S., Kluftinger, E., and Wentland, J. (2018). Are you fluent in sexual emoji? Exploring the use of emoji in romantic and sexual contexts. Canadian J. Hum. Sexual. 27, 226–234. doi: 10.3138/cjhs.2018-0020

Wang, L. (2018). IOS WeChat version 6.7.3 Update: Chat Stickers have big changes. Retrieved from Available online at: https://www.cnmo.com/news/644852.html (accessed September 20, 2022).

Wang, X. (2016). Social Media in Industrial China (1st ed., Vol. 6). London: UCL Press. doi: 10.2307/j.ctt1g69xtj

Wang, X., and Haapio-Kirk, L. (2021). Emotion work via digital visual communication: A comparative study between China and Japan. Global Media China 6, 325–344. doi: 10.1177/20594364211008044

World Emoji Day (2017). Emoji statistics. Available online at: https://worldemojiday.com/statistics/ (accessed September 20, 2022).

Xie, L. (2017). The marked flip of youth subculture in the new media era ——Taking emoji as an example. J. Chongqing Radio Telev. Univ. 29, 27–33.

Yang, H., and Fan, Y. F. (2021). “Ceremonial State”: Concept, history and mechanism. Int. Confuc. 3, 5–18.

Yang, M. M. (1994). “The “Art” in Guanxixue: Ethics, Tactics, and Etiquette,” in Gifts, favors, and banquets: The art of social relationships in China (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press) 109–145.

Yang, M. M. (2016). Gifts, Favors, and Banquets: The Art of Social Relationships in China. Ithaca, NY, UK: Cornell University Press. doi: 10.7591/9781501713057

Yang, Z., and Laroche, M. (2011). Parental responsiveness and adolescent susceptibility to peer influence: A cross-cultural investigation. J. Bus. Res. 64, 979–987. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2010.11.021

Yang, Z., Wang, Y., and Hwang, J. (2020). “Generation Z in China: Implications for global brands,” in The new generation Z in Asia: Dynamics, differences, digitalisation (New York: Emerald Publishing Limited) 23–37. doi: 10.1108/978-1-80043-220-820201005

Zhang, N. (2016). Dissolution as resistance: an analysis of the youth subculture of the “Emoji Wars”. Mod. Commun. 9, 126–131.

Zhang, X., Sun, H., and Zhao, X. (2017). From “post-90s” to “post-00s”: A survey report on the development of children and adolescents in China. Res. Chinese Youth 2, 98–107.

Keywords: visual language, Chinese young people, social media, etiquette, WeChat

Citation: Liu R (2023) WeChat online visual language among Chinese Gen Z: virtual gift, aesthetic identity, and affection language. Front. Commun. 8:1172115. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2023.1172115

Received: 23 February 2023; Accepted: 15 August 2023;

Published: 01 September 2023.

Edited by:

Sabine Tan, Independent Researcher, Singapore, SingaporeReviewed by:

Shuhan Chen, University of the Arts London, United KingdomCopyright © 2023 Liu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ruoxi Liu, emN6bHIxM0B1Y2wuYWMudWs=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.