94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Commun., 16 August 2023

Sec. Health Communication

Volume 8 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomm.2023.1153679

This article is part of the Research TopicCentering Women, Health, and Health Equity in Health CommunicationView all 9 articles

Background: Throughout the twentieth century, public health agencies and expert healthcare professionals have recognized breastfeeding as the most nutritious and appropriate option for feeding infants. The Ecuadorian government, in line with international guidelines, has therefore developed laws and initiatives to improve the initiation and maintenance of breastfeeding, especially among working mothers. However, breastfeeding rates in Ecuador are low.

Methods: A qualitative methodology following social constructionist approaches was applied to explore the breastfeeding experiences of Ecuadorian women who are both mothers and healthcare professionals. Using snowball sampling, 60 healthcare professionals who breastfed their babies: 20 nurses, 20 physicians, and 20 nutritionists, took part in research interviews lasting between 30 and 92 minutes. All participants are currently offering telehealth or face-to-face consultation to their patients in Ecuador. Since Ecuador is a multicultural country, efforts were made to include participants from different regions of the country. Data gathering employed virtual semi-structured interviews including Photovoice. The interviews were carried out in Spanish, following a semi-structured topic guide. The data analysis employed constant comparative methods.

Results: The analysis produced three overarching themes: Integrating breastfeeding in life and work; Establishing space for breastfeeding at work; Negotiations and tensions. The first theme: Integrating breastfeeding in life and work addresses participants' corporeal and emotional experiences when breastfeeding. This theme also includes the participants' experiences of how they integrated their maternal identity and adapted their breastfeeding bodies to their daily routines. The second theme: Establishing space for breastfeeding at work includes the challenges that some women encounter when incorporating and seeking to combine breastfeeding in their professional identities. The third theme: Negotiations and tensions covers how this group of female healthcare professionals had to negotiate the time and space to continue breastfeeding their children while working.

Since 1990, when the Innocenti Declaration was established, and then its later revision in 2005, there have been guidelines to promote and support breastfeeding worldwide. The main aims of the Innocenti Declaration are the creation of supportive breastfeeding environments, including hospitals and the workplace, and the provision of support and guidance for exclusive and extended breastfeeding practices to all women (WHO, 1990; UNICEF, 2005). The institutionalization of breastfeeding is a public health worldwide goal to encourage governments and institutions to protect and support lactation to ensure the wellbeing of mothers and children (UNICEF and WHO, 2017).

The Innocenti Declaration called for women to be able to breastfeed at work, but working mothers often experience challenges in meeting this call. UNICEF (2005) suggested increasing the weeks of maternity leave worldwide and that governments protect and facilitate exclusive breastfeeding for working mothers. Navarro-Rosenblatt and Garmendia (2018) argue that maternity leave would allow women to achieve exclusive breastfeeding from 3 to 6 months. Exclusive feeding has not yet been achieved (Freire et al., 2014), 32.3% of infants under 6 months in the Americas region are exclusively breastfed (PAHO, 2022). The prevalence of exclusive lactation among children younger than 6 months of age varies by country in the Americas, ranging from 3.5% in Saint Lucia in 2012 to 65.3% in Peru in 2019 (PAHO, 2022). In Ecuador in particular, fewer than 43.8 % new mothers breastfeed exclusively (Freire et al., 2014). Also, workplaces would be able to provide working mothers with nursing rooms and facilities to store breastmilk, as well as breaks for pumping and the support of supervisors and colleagues, allow extended breastfeeding to continue (Steurer, 2017). The facilities, however, are not fully implemented in most contexts and, in Ecuador, fewer than 10% of workplaces have designated space for breastfeeding breaks (Ministry of Public Health of Ecuador, 2011).

As such, the workplace is a significant setting in which women feel either supported or discouraged to breastfeed their babies. It is in the workplace that issues related to the balance between being a good mother and a good worker while breastfeeding are raised (Cripe, 2017). For instance, within the mother-worker identity, ideological tensions arise due to social constructs that a woman cannot be both a good mother and a good worker (Gatrell, 2017). In fact, the sensemaking of a good mother-worker identity can be easily altered due to the sense of not fulfilling each of her roles (Buzzanell et al., 2005). Cripe argues that some mothers decided to stop working to continue breastfeeding their babies, whilst others decided to stop breastfeeding their baby to continue working. However, both scenarios brought suffering to women due to the loss of one important part of their lives. The mother who breastfeeds and works has the considerable added burden of combining being a good mother who breastfeeds her baby and at the same time a good worker who accomplishes the teamwork goals (Turner and Norwood, 2013). Similarly, the main barrier to breastfeeding is returning to work after maternity leave, especially if workplaces do not have facilities for breastmilk pumping (Dearden et al., 2002; Mirkovic et al., 2014). Finally, in the workplace environment there is substantial stigma toward breastfeeding mothers, especially from coworkers that label mothers as selfish and unprofessional for taking pumping breaks (Zhuang et al., 2018). Managing the breastfeeding mother-worker identity is determined by being in control of time and space (Lee, 2018). Moreover, women ought to accommodate the breastfeeding body to comply with the workplace bodily norms (Gatrell, 2017) through negotiating with colleagues and bosses to manage schedules and access to a private place in the work for pumping or breastfeeding (Johnson and Salpini, 2017).

These tensions may become even more acute around the experiences of healthcare professionals who are also breastfeeding mothers. In the healthcare field professionals may often set aside their other identities to embrace completely their role as healthcare personnel who are devoted and centered on their patients (Monrouxe, 2016). As such, in the workplace, healthcare professionals who are mothers face opposing demands at work to avoid transgressing conventional conceptions of embodiment, regulating their bodies and nursing practices to balance the competing requirements of their identities (Burns et al., 2022). Although, due to their knowledge of the benefits of breastfeeding, healthcare providers initiate breastfeeding sooner after birth than the general population, the extended breastfeeding rates amongst this group are lower than for the general population (Riggins et al., 2012). Women in the healthcare field face several constraints when returning to work and aiming to continue breastfeeding, such as a lack of support from the working environment (Sattari et al., 2010), a demanding and competitive working environment (Melnitchouk et al., 2018), indifference toward the bodily necessity to express breast milk (Danziger, 2019), and employers failing to comply with the law requiring breaks for breastmilk expression and reduced working hours (Sattari et al., 2013). Indeed, in Ecuador, fewer than 28% of nursing mothers who are also healthcare workers breastfeed exclusively (Freire et al., 2014), and healthcare facilities are less likely than other professional workplaces to have breastfeeding rooms or break times (Ministry of Public Health of Ecuador, 2011).

Breastfeeding mothers who are also healthcare providers may thus experience the tensions and contradictions of worker-mother identities more sharply than other working mothers, even as they also are (ironically) trained in promoting the benefits of breastfeeding to working mothers. This group of women may therefore provide particular insight into the experiences of working mothers, in general, and with specific relevance to healthcare professionals. This study therefore sought to address the following research question:

What is the breastfeeding experience of Ecuadorian women who are both mothers and healthcare professionals?

Ecuadorian women who are both mothers and healthcare professionals do not simply decide whether to breastfeed on their own. Rather, multiple structural, institutional, and individual determinants have an impact on whether or not women breastfeed (Rollins et al., 2016). Although public health experts argue that breastfeeding is the ideal and natural way of feeding infants, in developed countries there is still a prominent stigma about breastfeeding in public spaces due to the sexual connotation of women's breasts (Wolf, 2008). Acker (2009) notes that in developed countries such as the U.S. breasts are hypersexualized, and breastfeeding in public is sanctioned due to cultural beliefs and gender stereotypes. On the other hand, in developing countries such as Ecuador or Samoa, breastfeeding in public spaces is encouraged by public health policies and it is perceived as a natural act, accepted and expected as a social norm, especially in rural areas (Wolf, 2008; Freire et al., 2020).

At an institutional level, health systems, workplaces, and public health institutions can facilitate or diminish breastfeeding practices among women. Regarding public health and the health system, one of the main strategies is the Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative. This initiative is a global program supported by WHO and UNICEF to recognize hospitals and birthing centers offering an optimal lactation environment such as skin to skin contact, breastfeeding during the first hour of birth, rooming-in and rejections of baby formula and pacifiers (UNICEF and WHO, 2017). Also, there are lay initiatives for breastfeeding support such as La Leche League International (LLLI), founded in the US in 1956. LLLI is a movement that provides peer support to mothers who want to breastfeed their babies through one to one and group counseling for mothers and their family (La Leche League International, 2020). Similarly, the World Alliance for Breastfeeding Action (WABA), founded in 1991, is a breastfeeding coalition of organizations and individuals that support and promote breastfeeding (World Alliance for Breastfeeding Action, 2020).

In addition, healthcare systems should train their healthcare professionals in breastfeeding education skills, so as to better support mothers and families, and ensure adequate breastfeeding education for mothers (UNICEF, 2005). Labbok et al. (2008) argue that including breastfeeding education and counseling in the healthcare professions' undergraduate curricula will ensure adequate communication regarding breastfeeding practices in the health encounter between the health provider and the mother. However, healthcare providers, physicians, dieticians, and nurses do not always have enough knowledge and skills to educate new mothers adequately or to communicate the benefits and best practices of breastfeeding (Leviniene et al., 2009). Similarly, some healthcare providers have negative attitudes toward breastfeeding that discourage mothers from exclusive breastfeeding (Palmér et al., 2012). Moreover, bottle-fed formula milk is sometimes offered in the first hours after delivery, especially when the baby was delivered by cesarean and the interaction between the mother and the baby is delayed, often resulting in a lack of lactation (Prior et al., 2012).

Individual determinants such as women's agency, self-efficacy, and confidence are also essential for breastfeeding initiation and duration (Rollins et al., 2016). Perceived barriers such as a baby's temperament influence the woman's decision to breastfeed (Mosquera et al., 2019). For instance, a mother is less likely to breastfeed her child when the infant is irritable because of colic, and she might even decide to stop breastfeeding (Howard et al., 2006). Mothers' confidence is also a behavioral determinant that influences exclusive breastfeeding. According to Avery et al. (2009) mothers who are more confident are more likely to breastfeed their child for 6 months and report the desire to continue breastfeeding. Hence, mothers with a high sense of self-efficacy feel confident enough to exclusively breastfeed their infants whilst mothers who have a perceived lack of milk or have insufficient milk production usually stop lactation (McCann and Bender, 2005; Odom et al., 2013). Finally, the perceived health and emotional benefits of exclusive breastfeeding have an impact on its practice. Daly et al. (2014) state that mothers who receive breastfeeding information prior to giving birth, on topics such as the advantages of chemical-free milk, and the increased bonding between mother and child, are more likely to breastfeed exclusively.

The communication scholar Allen (2011) argues that “identity refers to an individual and/or a collective aspect of being” (p.11). As such, people develop several identities during their life due to their roles in society and how they interact with others as a part of multiple social groups (Burke and Stets, 2009; Brekhus, 2020). The maternal identity is socially constructed and, thus, it is not constant. The way that motherhood is understood and lived is rooted in the cultural and social context of each society (O'Reilly, 2014). Likewise, the healthcare professional identity is interwoven in the social structure and occurs at the same time at individual and collective levels through socialization with mentors, peers, and patients in clinical and community practices (Cruess and Cruess, 2016).

Patriarchy, female bodies, and identity are interconnected elements that profoundly shape the experiences and perceptions of women in society (Allen, 2011). Patriarchy, as a social system, perpetuates male dominance and control over various aspects of life, including societal norms, power structures, gender roles, women's bodily autonomy, reproductive rights, and agency (Allen, 2011). Within this context, female bodies often become subject to objectification, scrutiny, and control (Lupton, 2011). This profoundly impacts on women's identities and their roles in society (Allen, 2011). Moreover, the intersection of patriarchy with race, social class, and gender, adds further complexity to the experiences of women, as the impact of these oppressive systems can be amplified or compounded (Dubriwny, 2013).

In the same vein, in Western societies women's bodies have been the subject of medical surveillance from menstruation, fertility, pregnancy, partum, postpartum, lactation to menopause (Lupton, 2011). This medical surveillance over female bodies leads to medicalization of women's health (Eden, 2012). Social and cultural constructs within society have led to the institutionalization of motherhood. That institutionalization has brought a series of restrictions, surveillance, as well as rules regarding pregnancy, birth, and breastfeeding (Rich, 1995).

This study employed qualitative methods to understand and explore the experience of breastfeeding of Ecuadorian women who are both mothers and healthcare professionals. Our interviews took a social constructionist approach to understanding and exploring the experiences of a group of these women. Social constructionism understands that people create a social reality through collective interactions in a particular society, culture, and period of time (Charmaz, 2014) and that the categories and concepts we employ are historically and culturally determined (Burr, 2015). We, drawing on Lupton (2012a), do not question the reality of lactation (or inability to lactate) and bodily experiences of breastfeeding; on the contrary, we seek to explore the way in which people make sense of these states and experiences, and construct and interpret them through social interaction (Babrow and Mattson, 2002, 2011; Conrad and Barker, 2010). Social constructionism acknowledges that exposing the social foundations of healthcare and illness states makes these phenomena susceptible to change, negotiation, and resistance (Babrow and Mattson, 2011). Because interpretations and meanings are varied and multiple (Creswell and Poth, 2018), a social constructionist approach requires us to look for the complexity of the phenomena under investigation.

We collected data via online semi-structured interviews, including Photovoice. Data collection for this study lasted 10 weeks, from the second week of September 2021 until the last week of November 2021. The online semi-structured interviews followed a topic guide. The first part of the topic guide asked general demographic questions about the participants' professions, years of practice, age, and the number of children. The second part of the topic guide enquired about participants' experiences of breastfeeding as mothers and healthcare professionals. Lastly, the third section aimed to understand their breastfeeding experiences through Photovoice.

Semi-structured interviews are often used to generate accounts of participants' worlds. According to Tracy (2019), the open-ended nature of the questions gives the participants the freedom to share their ideas, beliefs, and accounts of the issues that are important to them and enables participants to offer their own constructions and interpretations of their experience. Likewise, in virtual interviews, the interaction and sharing of experiences is framed by the online presence of both the researcher and the participant. Photovoice has been traditionally used to foster social change, but it also allows individual empowerment and representation (Baker and Wang, 2006; Catalani and Minkler, 2010). Photovoice participants take photos of how they perceive a specific issue of their life (Novak, 2010). These photos then become part of a guided discussion so that researchers can understand how the participants make meaning out of those photographs, and thereby increase understanding of the specific issue (Wang and Burris, 1997).

Participants fulfilled the following inclusion criteria: (a) a woman who was born in Ecuador, (b) a nutritionist, physician, or nurse with their practice in Ecuador, (c) have experience in breastfeeding education, (d) have breastfed their children, or currently breastfeed them, and (e) provide their consent to participate in the study. The study followed a snowball sampling method. We initially identified several healthcare professionals who fulfilled the inclusion criteria. We asked them to circulate the announcement of the study among other colleagues and/or suggest other potential participants that might meet the study's inclusion criteria (Tracy, 2019). Physicians, nutritionists, and nurses interested in participating in the research contacted the first author directly via email or phone messages. Once potential participants contacted the first author, she sent them the link to the consent form of the study. When the women agreed to participate in the study, the first author contacted them via email asking if they had questions about the study and asking them to share their availability (the date and time) for the interview. Once the future participant set a time and the date for the interview, they received a Zoom link for the online interview and a reminder to bring their photograph or photographs to the interview.

The interviews took place through the online platform Zoom and were audio-recorded. Because the participants speak Spanish, and the first author is a native Spanish speaker, the interviews were carried out in Spanish. The interviews were transcribed verbatim with a denaturalized approach. The denaturalized approach was chosen because it allows the researcher to embody the meaning and perceptions of narratives in the interviews rather than the particulars of the language (Oliver et al., 2005). We followed a modified version of Wang and Burris's (1997) Photovoice, which consists of three stages: selecting, contextualizing, and codifying. In the selecting phase, each participant presented their photos or the photo that accurately reflected her breastfeeding experiences. On the day of the interview, after finishing the first two sections of the topic guide, the first author asked the participant to share the photographs via email, WhatsApp message, or through Zoom, and the first author projected the photo in the computer to make visible the photo for the participant and herself. In the second phase, contextualizing or storytelling, the photos are linked to a story. Each participant narrated her story about the selected photos. In this phase, the voice in Photovoice becomes essential. In the contextualizing phase, the meaning of the photographs took place in the interview. An audio or video recording of the interview prioritizes the participants' voices, giving them the power to interpret their photos based on their embodied experiences rather than giving the authority for the interpretation of the researcher (Ellingson and Sotirin, 2020). At the heart of verbalizing participatory photographs, in the interview, each participant was invited to talk and discuss how they created a representation of their experience of breastfeeding. During this phase, the participants expanded and complemented the stories narrated during the first part of the interview through their photos.

Regarding the data analysis, following Tracy's (2019) recommendations for processing qualitative data, the initial coding applied in vivo coding, that is, line-by-line coding of what the participants said during the interviews. This approach is also suitable for answering research questions about personal meanings expressed in the data (Saldaña, 2021). The initial coding allowed the first author to define and understand what was happening with the collected data. The first cycle of initial coding resulted in 198 codes. We followed a constant comparative method to revisit the data and organize the codes into clustered codes for further analysis by comparing interview segments in the same interview as well as making comparisons between different interviews (Charmaz, 2014). After initial coding, the second cycle of coding began with the identification of patterns in the codes that emerged from the data through focused coding. Focused coding allowed us to develop major sub-categories for analysis. We concluded the focused coding with 50 sub-categories. After focused coding, we started axial coding to reassemble the data that was split during the two rounds of initial coding and focused coding. We concluded the axial coding with 25 categories. The final cycle of coding was theoretical coding. As such, we wanted to understand possible relationships between categories to draw a storyline to theorize about the breastfeeding experiences of Ecuadorian women who have identities as both mothers and healthcare professionals.

Regarding translation, the first author followed the approach of Lincoln et al. (2016) and Gonzalez and Lincoln (2022) for cross-cultural and cross-linguistic research. The recorded interviews, transcripts, the initial coding, and the focused coding were developed in Spanish. The axial and theoretical coding were developed in English. Some analytic memos were developed in English and some in Spanish. Lincoln et al. (2016) mention that “interviewing in one's own language gives the researcher grammatical liberty, access to colloquialisms, and idiomatic freedom, so that deeper meanings in Spanish and other languages may be exposed when you read the original data” (p.536). Moreover, the initial coding cycles were developed in the original language of the participants in order to guarantee the continuity of their narratives, whilst final coding, themes, and the storyline were in English. In order to organize the data and emerging codes during the first cycle of coding, we used ATLAS.ti 9, but used manual coding in the subsequent rounds of coding, from the second cycle of in vivo coding until the theoretical coding.

The protocol was approved at the Ohio University Institutional Review Board and the Ethical Research Committee at the Pontifical Catholic University of Ecuador. All necessary measures were considered to protect confidentiality, present the information anonymously, as well as the use of photographs, narratives and meanings. Likewise, respect for the autonomy of the participants, voluntariness, and the subjects' freedom to discontinue the study if they so desired prevailed.

Sixty healthcare professionals were included in the research: 20 nurses, 20 physicians, and 20 nutritionists. Each interview lasted between 30 and 92 minutes. All participants are currently offering telehealth or face-to-face consultation to their patients in Ecuador. Since Ecuador is a multicultural country, efforts were made to include participants from different regions of the country. We discuss the themes and sub-themes that emerged from the analysis, seeking to bring alive these women's narratives related to their experience with breastfeeding as healthcare professionals and mothers. We report the participants' narratives using the pseudonym that they chose for the interview, and we label each with their profession. As previously mentioned, the interviews were carried out in Spanish, and as a result, there are some tensions in the transcripts between English grammatical structures and keeping the interview excerpts as true to the Spanish data as possible, since some Spanish words cannot be easily translated into English. The data analysis resulted in three overarching themes: Integrating breastfeeding in life and work; Establishing space for breastfeeding at work; Negotiations and tensions.

The theme “integrating breastfeeding” focuses on sharing the participants' corporeal and emotional experiences when breastfeeding. This theme also includes the participants' experiences of how they integrated their maternal identity and adapted their breastfeeding bodies to their daily routines.

All the participants in the study mentioned that becoming a breastfeeding woman was a life-changing experience, due to the bodily adaptation and sentiments brought with breastfeeding. As Ani, a family doctor put it: “Breastfeeding carried several feelings of ambivalence: the joy of having my baby next to me, I like to feed him from my body, but he also invades my body and hurts it”. Ani's sentiment was echoed by other participants. Emilia, a lactation physician, photographed herself breastfeeding her baby and said (Figure 1A):

Breastfeeding hurt me, but it was also a moment of a unique connection with my daughter. I took this selfie while feeding my baby because I felt peace with breastfeeding when it did not hurt. Here I enjoyed breastfeeding because the first months were periods of great pain. When I see this photo, as a breastfeeding consultant, I see my bad position and latch, which I did not know at the time. But above all as a mother, when I see this photo, I see that I am enjoying my breastfeeding and my baby. It was the moment of reconciliation with my breastfeeding.

The representations about breastfeeding changed and evolved when the participants integrated their maternal identity into their identity as health professionals. For the participants, breastfeeding became a bodily experience that is more than the act of feeding. Mariquita's story about her bodily experience of breastfeeding was made in light of Figure 1B, an image that she shared based on her breastfeeding experience as a nutritionist-mother:

In this photo, I'm with my daughter. This photo represents the love you can give through breastfeeding and the connection with your baby. When I was pregnant, I felt that I was giving life to my daughter because she was growing inside me, but when my baby was born, breastfeeding was that bond which continued giving her life because my body generated the milk to feed her. My body also gives my baby security when it comes to breastfeeding; she touches my face or chest, holds my hand, and feels that I am there for her. My photo represents the connection I made with breastfeeding that goes beyond the act of feeding her.

The participants on the whole demonstrated that expressing their milk was a priority that they established as a daily routine as a way to guarantee breast milk for their children when they were working, and thus maintain breastfeeding without relegating their other identity as healthcare professionals. Laura, a nutritionist, took a photo in which she expressed how it was the incorporation of her identity as a nursing mother in her life (see Figure 1C):

This photo represents how I combine the aspects of being a professional woman and a mother at the same time while breastfeeding. So first, I put the shoes there because wearing heels is something that I have always loved. Wearing heels is part of my essence. Now in my bag, there were no longer just the office things, the breast pump was also inside my bag, but there was no longer space for my personal items such as make-up because the breast pump had to fit in wherever I went. It was my company, in my office, in my car all the time. I had to combine both being a working woman and a mother because both are important to me. Sometimes, there was not time to separate those two areas of my life. They just had to be together because I was still on the computer while expressing my milk. So, you keep doing the two things at the same time. It governs your day to day, being a health professional and being a mother. I am thrilled because I managed to combine my profession and breastfeeding. In the beginning, I was scared of maybe not achieving it, but finally, it is something that became my routine, and I managed to combine the two roles well.

This theme highlights the challenges that some women in the study said that they had encountered when seeking to incorporate and combine breastfeeding with their professional identities. A number of participants felt that their demanding job, time constraints while working, and lack of adequate space to pump were impediments to regularly expressing milk.

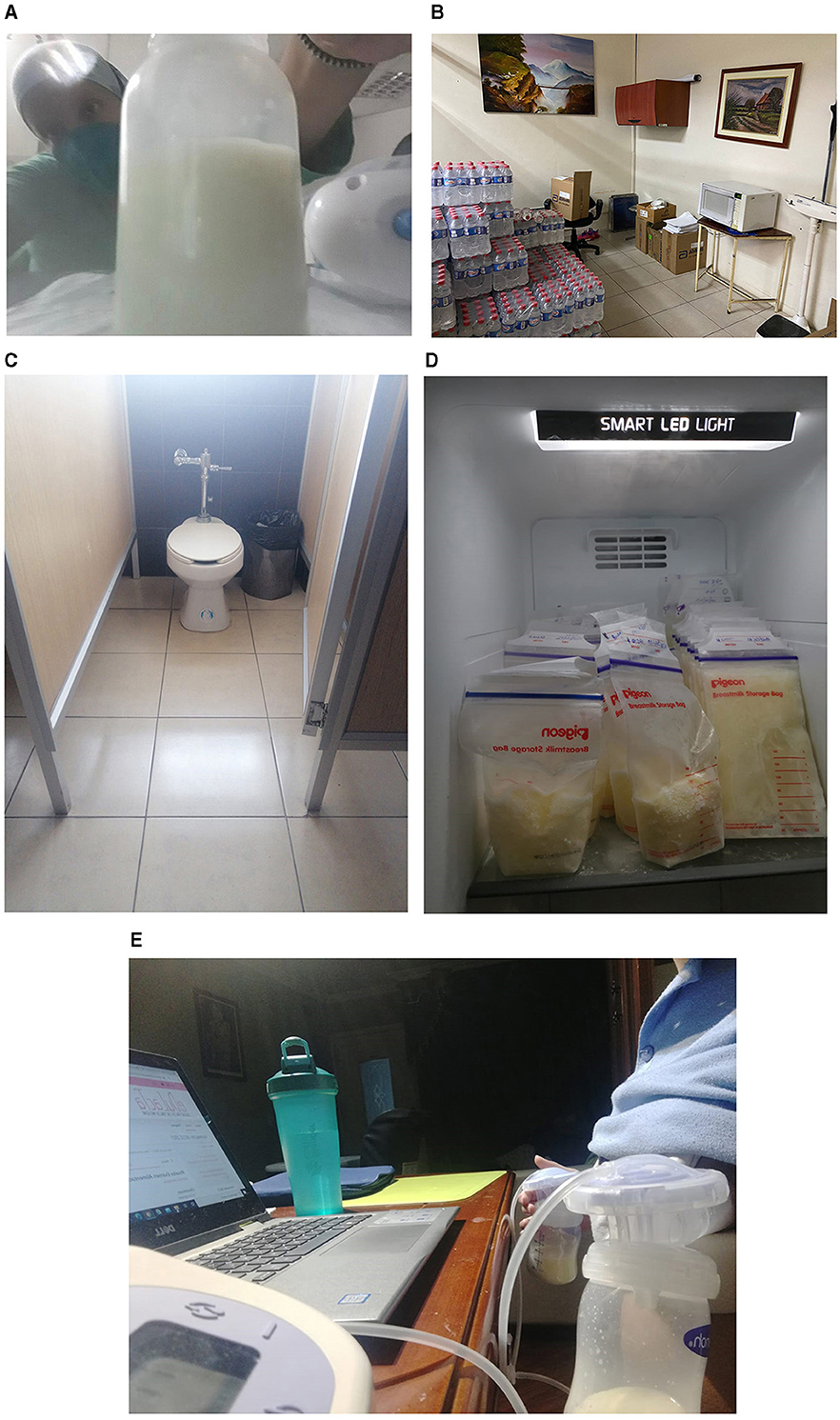

These participants mentioned that expressing their breast milk at the workplace was a challenge due to the lack of an appropriate space to do it. Lia, a nutritionist, shared a picture of herself in the lactation room of the outpatient clinic where she works (Figure 2A). In her narrative of the photo, she mentioned several issues regarding finding adequate time to express her milk:

I took this photo in the breastfeeding room of the outpatient clinic where I work during the pandemic. I'm still in a protective suit, pumping my milk. I was worried because I already had patients waiting for me, and I had to express my milk quickly to go back to work. This was really a challenge for me to negotiate how many times I could access the breastfeeding room with my boss. Although we had adequate space to express our milk, it was a challenge to do it.

Figure 2. Establishing space. Images from Lia (A), Claudia (B), Alexandra (C), Carla (D), and Lali (E).

Very few women in the study had access to a lactation room in their workplace; in some cases, because the hospitals or health centers did not have one and in other scenarios, because that space was designated to the patients but not the workers. As Nita said, “they told me that this space [the lactation room] was only for mothers who deliver in the hospital, and it was an exclusive area for patients, not for health personnel”. Consequently, the participants had to find other spaces to express their milk in their workplace. Claudia, a nutritionist, took a picture of one such space: the hospital storeroom, a place where she went to express her milk because the hospital where she works does not have a lactation room (Figure 2B):

My photo is inspired by the issue of milk expression at work because it was a challenge for me. The hospital where I work as a nutritionist does not have a breastfeeding room for the staff, and I expressed my milk in this storeroom. This is the storeroom that we have in the nutrition office, here we store different supplies from our area. To express my milk, I cleaned the upper part of the microwave very well because I put the milk that I expressed there before storing it, and I cleaned it so well that my milk did not get contaminated. Next to the microwave, there is a socket where I plugged in my electric breast pump, and I sat in that black chair for milk expression. That was my breastfeeding room. That space generated a lot of frustration because I did not have a safe, clean and comfortable place to express my milk. I did not have adequate time to do it. I only needed 15 to 20 minutes for pumping, which was already causing discomfort in my work. I was frustrated and always thinking why do I have to express my milk here, why don't I have a proper place?

In the same vein, other participants shared similar photos and stories like Claudia about inadequate places for milk expression, spaces that generated negative feelings. Alexandra, a pediatrician, shared a photo of the hospital toilet, a place that she often went for expressing her breastmilk (Figure 2C). Alexandra said:

This is the bathroom of the hospital where I work as a pediatrician. This photo causes me a lot of sadness and frustration because public and private hospitals in Ecuador only generate excellent strategies for breastfeeding and pregnant patients. Still, unfortunately for their health personnel, those strategies to support lactation fade or just don't exist. I used to express my milk in that bathroom because we didn't have a suitable place to do it. I used to sit in the toilet lid concerned about the germs and dirt and all the contamination. The bathroom was the only option I had. To prevent contamination of my milk, I disinfected the entire bathroom, especially the toilet lid where I used to sit. Also, I disinfected my hands and my uniform. I was very afraid of contaminating the milk for my baby, but the bathroom was the only option I had. I turned on the electric pump, sat in the bathroom, and quickly collected my milk. The truth is I would do it again, but I think it is not fair, and it is not worthy that health professionals are not supported, we are also humans and mothers, and that we must resort to bathrooms or offices to express our milk is not fair.

The majority of participants agreed that maintaining breastfeeding and guaranteeing breast milk production was their main aim when they returned to work after their maternity leave. Consequently, expressing their milk and storing it in what they called “breast milk bank at home” was the main strategy to continue feeding their babies with their milk. All my participants who stored their milk at home mentioned that they developed a breastmilk bank. The unconscious meaning of storing their milk in the fridge as a bank refers to milk as a resource to guarantee the food supply to their children. Carla a nurse took a photo of her breast milk bank at home (Figure 2D) and explained what it meant for her:

This is my milk bank. This is my refrigerator, and my mother and husband helped me organize it. We separated a whole shelf to store milk for my baby, and we separated breast milk from other foods so that it always stayed clean. In the beginning, I was putting together my milk bank in the bottles, but when I acquired the first breast milk storage bags to collect my milk, it was such a great emotion because I was already going to have one serving of my milk, and I was able to write the date and time to organize my milk better. With this, I felt that not a drop of my breast milk would go to waste. The milk bank is trustworthy because I trust that my baby will have enough food when I store my milk, and I would not worry about his feeding while I went to work. The milk bank gives me peace of mind.

Other participants echoed Carla's remark, commenting that their breast milk bank at home was the only option to enable them to continue breastfeeding their babies while working. Like Carla, other participants organized the breast milk storage bags in their fridge by date in order to provide optimal food to their children, relegating family foods to other spaces in the fridge in order to keep the breast milk clean. The breastmilk bank is the source of food for these participants' children during their absences.

In all cases, the participants reported that the creation of a breast milk bank at home—expressing milk, storing the milk, organizing it by date, and cleaning the breast pump—requires effort, discipline, and support. Lali, a pediatric gastroenterologist, took a photo of herself expressing her milk and narrated all the processes that incorporate the breast milk bank into her daily routine as a healthcare professional involves (Figure 2E):

This photo represents my day today, and I took it thinking about this interview because it reflects how breastfeeding is part of every moment of my life. And it reflects what I do every day to create and maintain my milk bank, which is my daughter's means of feeding, but the milk bank is not created alone; it needs dedication, perseverance, and effort. I took this photo at night; I was studying breastfeeding training while my baby was asleep, and it was the moment that I had to express my milk. In the photo, you can see my bottle of water because breastfeeding makes your body ask you for water, there is my computer, and I am with the mechanical breast pump. With this photo, I want to say that I, as a mother and a doctor, must occupy those moments while I study, eat or work to express the milk to maintain the milk bank that is now super important to me. And of course, this would not be possible without the constant support of my family.

Lali's reflection about “planning to take this photo for the interview” illustrates how interviewees actively participated in the representations of their breastfeeding experiences constructed in our interaction. Moreover, these remarks from Lali and Carla clearly illustrate that they found expressing their milk and store it in the breastmilk bank was just as important and demanding as breastfeeding.

This theme addresses the sentiments and experiences that the participants shared during the interviews with regards to how being a breastfeeding working mother becomes a negotiation rather than a right. The majority of participants shared that they faced challenges when they wanted to fulfill their identities as mothers and healthcare professionals while breastfeeding. Nita, a 36-year-old pediatrician, shared her photograph (Figure 3A) and experience:

In this photograph, I wanted to represent what happened to me on many occasions that I was always in a hurry, against the clock. As a pediatrician, I work with hospitalized children and newborns in the intensive care unit; my work is demanding, and when you have a severely ill patient, you cannot leave them. When I was breastfeeding, I spent many hours without expressing my milk with a lot of pain, with engorged breasts, feeling that the milk collectors I was putting on were no longer enough. Even my uniform and my coat were stained with breast milk. I had to run to the bathroom of the hospital where I worked at that time to express my milk very quickly and continue with my work. That quick milk expression was not for my baby; it was to calm the pain I felt in my breasts. Discarding my milk down the sink in the hospital bathroom caused me a lot of pain and sadness. There came a time when I could no longer continue, so I went to the human resources office to ask them if they could modify my schedules to include an extraction time, and they were unable to help me. Sadly, I was forced to resign from that hospital. I really liked my work there. I enjoyed working as an intensive care pediatrician very much, but the support was nil from my hospital.

Other women also shared Nita's sentiment regarding their demanding job. The negotiation to pump their milk was not only with the institution that they work in, but also with their patients. Majo, a 34-year-old nutritionist said:

When my baby was 4 months old, I went back to work and spent long hours away from home. I worked in the pediatric oncology area in a hospital, both in hospitalization and in the outpatient clinic. When patients are scheduled for an outpatient appointment, you don't have time to rest, and expressing my milk was very difficult or almost impossible some days. If a patient came in and I was in my office expressing my milk, they would knock on the door or get annoyed if I was late. The patients cannot wait for 10 or 20 minutes. So, I often decided not to pump and just went quickly to the bathroom for hand expressing to avoid pain, and I continued working.

In this study, another aspect to consider regarding the possibility of continuing breastfeeding while at work was the woman's working team. Although their narratives were diverse, some of the women in the study had support from their team, while others did not. In both cases, they emphasized the crucial role of their colleagues in their lactation. Pam, a pediatrician said (Figure 3B):

When I returned to work, the pediatric patients affected by COVID were minimal. So, in the context of the pandemic, there was not such a high influx of patients in the outpatient clinic. I had patients who had complications, but we did not have the flow of patients that we usually have. The outpatient clinic was not saturated. Therefore, I had moments where my working team, doctors, and nurses supported me a lot with my breastfeeding due to these conditions. They told me, “Doctor, go to the office to pump, we will help you here with the patients and do things until you return”. So that is something that I am very grateful for. I think there was a lot of understanding and support in my work. My boss, a woman, organized my schedule with reduced hours and even tried not to expose me to cases that they saw would be complicated.

Pam's story show that she felt appreciated and understood during the time that she needed to pump, but the most noticeable aspect is that both team leaders were women. Although she did not specify if her boss was herself a mother, the fact that they were both women made Pam feel supported.

While the working environment was supportive for some of the women in the study, for others this was not the case. M.T., a 42-year-old gynecologist, said:

At that time, I was already working in the obstetric emergency area and had 24-hour shifts. The head of my department, when I returned to my work, told me that unfortunately, I could not take my breastfeeding hours because in the area that I worked, as it was a critical area, I must be always present. Then he told me ‘I'm sorry, I can't change your hours'. When I returned to work, my breastfeeding did not last for long, maybe two or three more months, as I did not have the stimulus of my baby's suckling. Little by little, I stopped producing milk.

Other participants also faced the same dilemma mentioned by MT. For example, Valentina, a 35-year-old nurse, explained the lack of support from her colleagues (Figure 3C):

I didn't have much support from my peers. Hospitals usually have a shortage of personnel in the nursing area, and there is also a lot of competition. When I was expressing my milk, I began to hear comments about my breaks to pump. They counted how many minutes I was away, and they said that I did not give enough care to the patients, in summary, that I was not doing my job. But the worst day was when I had a problem with my uniform. It was stained with breast milk, the collection cups were full, and I was so busy that I did not have time to go to the bathroom. My [male] colleague told me, ‘Change your uniform and do something so that it doesn't happen again. You are a nurse, and you should always have a clean uniform'. That day was horrible for me.

The themes illustrate the participants' experiences regarding the incorporation of breastfeeding in their daily lives. They initiated breastfeeding in the hospital, and maintained it until they came back to work after their maternity leave. The women illustrated the challenges that they had to face to maintain their breastfeeding, paying special attention when they came back to work.

The breastfeeding realities which the different participants narrated show a wide range of possibilities and experiences. Overall, negotiation of breastfeeding runs through all the women's narratives, especially when they came back to work, when they needed to find and negotiate adequate places and times to express their milk, including negotiating breaks for this with their colleagues, bosses, and patients.

Health promotion programs and public health interventions emphasize the importance of supporting the lactating working mother. These programs encourage actions such as reduced hours, access to lactation rooms, breaks for breastmilk expression, and colleagues' support (UNICEF, 2020). A smaller group of participants in this study had sufficient support from colleagues, bosses, and their institutions for them to have breaks for milk expression and adequate spaces to pump and store their milk. Moreover, they had reduced working hours to continue breastfeeding at home. However, despite this evident support from their workplace, these participants still had to manage their time and routines to incorporate breastfeeding into their daily life. Some mentioned that they had had to get used to carrying bottles, containers, and breast pumps everywhere. They also had to deemphasize their previous routines and roles to continue breastfeeding. These women, who were mostly not working in hospitals or clinics, were able to interrelate their identities as mothers and healthcare professionals to continue breastfeeding due to material and structural support from their working environment.

On the other hand, most participants, especially those who worked in hospitals and clinical settings, mentioned that the reality they experienced was not like the romanticized portrayal of breastfeeding support in the working environment. The female body has been seen as the “other” and invisible in the medical realm (Lupton, 2012a). When leaking, breastfeeding bodies are “othered” in the workplace, breastfeeding mothers experience isolation and intolerance for anything other than a generic-worker body (Young, 2020). The “ideal” professional is envisioned as “the abstract bodiless worker, who occupies the abstract, gender-neutral job, has no sexuality, no emotions, and does not procreate” (Acker, 1990, p.151). In the same vein, our participants' comments illustrate their perceptions that hospital healthcare workers are generally seen as agents who leave their self-identity as laypeople to one side and completely turn to their professional role, which centers on patient care and health improvement. Ironically enough, despite their knowledge, gained in part through their experience in breastfeeding education, participants found it difficult to have any impact on customary practices and perceptions in their own workspaces. Participants sought to incorporate their maternal identity in their professional role, and aimed to continue breastfeeding, but their breastfeeding bodies were invisible at work. This invisibility resulted in a lack of support in their work as breastfeeding mothers. As Lupton (2012b) argues, there is a constant tension between the recognition of the uniqueness of women's embodied experience (i.e., menstruation, childbearing, and breastfeeding) and the way patriarchy has defined such phenomena as the basis for women's inferiority and exclusion from public and economic spheres. In our study, when participants had the bodily necessity to express their milk, tensions arose in their work team regarding productivity and commitment, and also around finding the right place and time to express their milk.

A considerable body of research developed in the Global North about breastfeeding practices among physicians suggests that the main impediment to physicians continuing to breastfeed their children is their demanding job (Riggins et al., 2012; Juengst et al., 2019; Ersen et al., 2020). In our study, although the main reason for the participants to wean their babies was the lack of support from their working environment, the majority of healthcare professionals sustained breastfeeding while working until they decided to wean. However, to maintain their breastfeeding while at work without neglecting their professional roles required a high level of commitment, dedication, perseverance, and effort on their part.

A study developed among US pediatric residents suggested that the majority of breastfeeding residents were affected by challenges such as not having enough time or a proper space to pump (Ames and Burrows, 2019). Likewise, in our study, the female healthcare professionals expressed that they had to negotiate the pumping breaks not only with their colleagues but also with their patients. Moreover, another problem was finding a suitable space to express their milk. In the same vein, a study developed with nurses who breastfeed in Pakistan suggests that pumping pauses created difficulty for nurses who were trying to satisfy their employment demands while still fulfilling their maternal role (Riaz and Condon, 2019). Riaz and Condon suggest that the nurses' coworkers and managers believed that breaks for breastfeeding or pumping resulted in neglected patients. Our study accords with Riaz and Condon's findings; drawing on our participants' experiences there is an unequal balance of power, not only between the healthcare provider-mothers and their team leader, but also between them and their coworkers. Their coworkers appeared to interpret their pumping breaks as unprofessionalism and inefficiency.

Regarding the breastfeeding space at work, the lactation room is the safest, private space for breastfeeding working women to express their milk (UNICEF, 2020). Consequently, the Ministry of Public Health of Ecuador (2019) suggests that private and public businesses should create permanent or temporary lactation rooms that are adequate and consistent with the number of women who breastfeed simultaneously, guaranteeing comfort, and intimacy. Rooms should have adequate ventilation and lighting, and they should be cheerful and simply decorated with warm colors and without decorative material referring to breastfeeding bottles, pacifiers, or milk formulas. It should be a quiet environment that provides privacy and allows mothers to express their milk in a relaxed way, without external interference. The lactation room should be independent of the bathroom, guaranteeing hygiene and preventing contamination. It should offer comfortable chairs, a refrigerator, and a sink. The government of Ecuador encourages the creation of such lactation rooms in public and private working environments, but in the majority of private and public hospitals and outpatient clinics where these study participants work, that space did not exist, or access was only for patients, not for the workers. Our study participants had to resort to toilets, storage rooms, and offices to express their milk, making the pumping breaks moments of tension, frustration, and sadness due to the lack of support and imbalance of power from their working environment. An Australian study (Burns et al., 2022) similarly found that female healthcare providers in Australia had to use toilets, balconies, patients' breastfeeding rooms, offices, and lunchrooms due to the lack of lactation rooms for pumping breaks.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Ohio University Institutional Review Board (#21-D-109) and Ethical Research Committee at the Pontifical Catholic University of Ecuador (#EO-15-2021). The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

MM-G: conceptualization, validation, initial analysis, investigation, data curation, and writing—original draft preparation. MM-G, BB, and BV: methodology, further analysis, and writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

BV's post is funded by Marie Curie, grant number MCCC-FCH-18-U.

The authors thank the healthcare providers who were part of the study for their valuable narratives.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acker, J. (1990). Hierarchies, jobs, bodies: a theory of gendered organizations. Gender Soc. 4, 139–158.

Acker, M. (2009). Breast is best…but not everywhere: ambivalent sexism and attitudes toward private and public breastfeeding. Sex Roles 61, 476–490. doi: 10.1007/s11199-009-9655-z

Allen, B. (2011). Difference Matters Communicating Social Identity, 2nd Edn. Long Grove, IL: Waveland Press.

Ames, E. G., and Burrows, H. L. (2019). Differing experiences with breastfeeding in residency between mothers and coresidents. Breastfeed. Med. 14, 575–579. doi: 10.1089/bfm.2019.0001

Avery, A., Zimmermann, K., Underwood, P. W., and Magnus, J. H. (2009). Confident commitment is a key factor for sustained breastfeeding. Birth 36, 141–148. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-536x.2009.00312.x

Babrow, A., and Mattson, M. (2011). “Building health communication theories in the 21st century,” in The Routledge Handbook of Health Communication, eds T. L. Thompson, R. Parrott, and J. F. Nussbaum (London: Routledge), 18–35.

Babrow, A. S., and Mattson, M. (2002). “Theorizing about health communication,” in Handbook of Health Communication, eds T. L. Thompson, A. M. Dorsey, K. I. Miller, and R. Parrott (Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates), 35–61.

Baker, T. A., and Wang, C. C. (2006). Photovoice: use of a participatory action research method to explore the chronic pain experience in older adults. Qual. Health Res. 16, 1405–1413. doi: 10.1177/1049732306294118

Brekhus, W. H. (2020). The Sociology of Identity: Authenticity, Multidimensionality, and Mobility. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Burns, E., Gannon, S., Pierce, H., and Hugman, S. (2022). Corporeal generosity: breastfeeding bodies and female-dominated workplaces. Gender Work Organ. 29, 778–799. doi: 10.1111/gwao.12821

Buzzanell, P. M., Meisenbach, R., Remke, R., Liu, M., Bowers, V., and Conn, C. (2005). The good working mother: managerial women's sensemaking and feelings about work–family issues. Commun. Stud. 56, 261–285. doi: 10.1080/10510970500181389

Catalani, C., and Minkler, M. (2010). Photovoice: a review of the literature in health and public health. Health Educ. Behav. 37, 424–451.doi: 10.1177/1090198109342084

Conrad, P., and Barker, K. K. (2010). The social construction of illness: key insights and policy implications. J. Health Soc. Behav. 51, S67–S79. doi: 10.1177/0022146510383495

Creswell, J. W., and Poth, C. N. (2018). Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches, 4th Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Cripe, E. T. (2017). “You can't bring your cat to work”: challenges mothers face combining breastfeeding and working. Qual. Res. Rep. Commun. 18, 36–44. doi: 10.1080/17459435.2017.1294615

Cruess, R. L., and Cruess, S. R. (2016). “Professionalism and professional identity formation: the cognitive base,” in Teaching Medical Professionalism: Supporting the Development of Professional Identity, 2nd Edn., eds R. Cruess, S. Cruess, and Y. Steinert (Cambridge University Press), 5–25.

Daly, A., Pollard, C. M., Phillips, M., and Binns, C. W. (2014). Bennefits, barriers and enhablers of reastfeeding: factor analysis of population perceptions in Western Australia. PLoS ONE 9, e88204. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0088204

Danziger, P. (2019). Breastfeeding in medicine: time to practice what we preach. Pediatrics 144, e20191279. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-1279

Dearden, K. A., Quan, L. N., Do, M., Marsh, D. R., Pachón, H., Schroeder, D. G., et al. (2002). Wo outside the home is the primary barrier to exclusive breastfeeding in rural Vietnam: insights from mothers who exclusively breastfed and worked. Food Nutr. Bull. 23, 99–106. doi: 10.1177/15648265020234s114

Dubriwny, T. N. (2013). The Vulnerable Empowered Women: Feminist, Postfeminist, and Women's Health. London: Rutgers University Press.

Eden, A. R. (2012). “New professions and old practices: lactation consulting and the medicalization of breastfeeding,” in Beyond Health Beyond Choice: Breastfeeding Constraints and Realities, eds P. H. Smith, B. L. Hausman, and M. Labbok (London: Rutgers University Press), 98–109.

Ellingson, L., and Sotirin, P. (2020). Making Data in Qualitative Research: Engagements, Ethics, and Entanglements. New York, NY: Routledge.

Ersen, G., Kasim, I., Agadayi, E., Demir Alsancak, A., Sengezer, T., and Ozkara, A. (2020). Factors affecting the behavior and duration of breastfeeding among physician mothers. J. Hum. Lact. 36, 471–477. doi: 10.1177/0890334419892257

Freire, W. B., Waters, W. F., Román, D., Belmont, P., Wilkinson-Salamea, E., Diaz, A., et al. (2020). Breastfeeding practices and complementary feeding in Ecuador: implications for localized policy applications and promotion of breastfeeding: a pooled analysis. Int. Breastfeed. J. 15, 75. doi: 10.1186/s13006-020-00321-9

Freire,W. B Ramirez-Luzuriaga, M. J., Belmont, P., Mendieta, M. J., Silva-Jaramillo, K. M., Romero, N., et al (2014). Encuesta Nacional de Salud y Nutricion ENSANUT-ECU [National Health and Nutrition Survey ENSANUT-ECU]. Available online at: https://www.salud.gob.ec/encuesta-nacional-de-salud-y-nutricion-ensanut/

Gatrell, C. J. (2017). Boundary creatures? Employed, breastfeeding mothers and abjection as practice. Organ. Stud. 40, 421–442. doi: 10.1177/0170840617736932

Gonzalez, E. M., and Lincoln, Y. (2022). “Analyzing and coding interviews and focus groups considering cross-cultural and cross-language data,” in Analyzing and Interpreting Qualitative Research: After the Interview, eds C. H. Vanover, P. Mihas, and J. Saldaña (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage), 207–222.

Howard, C. R., Lanphear, N., Lanphear, B. P., Eberly, S., and Lawrence, R. A. (2006). Parental responses to infant crying and colic: the effect on breastfeeding duration. Breastfeed. Med. 1, 146–155. doi: 10.1089/bfm.2006.1.146

Johnson, K. M., and Salpini, C. (2017). Working and nursing: navigating job and breastfeeding demands at work. Commun. Work Family 20, 479–496. doi: 10.1080/13668803.2017.1303449

Juengst, S. B., Royston, A., Huang, I., and Wright, B. (2019). Family leave and return-to-work experiences of physician mothers. JAMA Netw. Open, 2, 1–15. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.13054

La Leche League International (2020). A Brief History of La Leche League International. Available online at: https://www.llli.org/about/history/ (accessed March 30, 2021).

Labbok, M. H., Smith, P. H., and Taylor, E. C. (2008). Breastfeeding and feminism: a focus on reproductive health, rights and justice. Int. Breastfeed. J. 3, 8. doi: 10.1186/1746-4358-3-8

Lee, R. (2018). Breastfeeding bodies: intimacies at work. Gender Work Organ. 25, 77–90. doi: 10.1111/gwao.12170

Leviniene, G., Petrauskiene, A., Tamulevičiene, E., Kudzyte, J., and Labanauskas, L. (2009). The evaluation of knowledge and activities of primary health care professionals in promoting breast-feeding. Medicina 45, 238. doi: 10.3390/medicina45030031

Lincoln, Y. S., González, E. M., and Aroztegui Massera, C. (2016). Spanish is a loving tongue...: performing qualitative research across languages and cultures. Qual. Inq. 22, 531–540. doi: 10.1177/1077800416636148

Lupton, D. (2012a). Medicine as Culture: Illness, Disease and the Body in Western societies. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Lupton, D. (2012b). Infant embodiment and interembodiment: a review of sociocultural perspectives. Childhood 20, 37–50. doi: 10.1177/0907568212447244

Lupton, D. A. (2011). “The best thing for the baby”: mothers' concepts and experiences related to promoting their infants' health and development. Health Risk Soc. 13, 637–651. doi: 10.1080/13698575.2011.624179

McCann, M. F., and Bender, D. E. (2005). Perceived insufficient milk as a barrier to optimal infant feeding: examples from Bolivia. J. Biosoc. Sci. 38, 1–24. doi: 10.1017/s0021932005007170

Melnitchouk, N., Scully, R. E., and Davids, J. S. (2018). Barriers to breastfeeding for US physicians who are mothers. JAMA Internal Med. 178, E1–E3. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.0320

Ministry of Public Health of Ecuador (2011). Normas para la implementación y funcionamiento de lactarios institucionales en los sectores público y privado en el Ecuador [Standards for the implementation of institutional lactation rooms in Ecuador]. Available online at: https://www.todaunavida.gob.ec/wp-content/uploads/downloads/2013/08/LACTARIOS-INSTITUCIONALES.pdf

Ministry of Public Health of Ecuador (2019). Adecuación y uso de las salas de apoyo a la lactancia materna en las empresas del sector privado [Adequacy and use of lactation romos for breastfeeding support in the private sector companies]. Available online at: https://www.salud.gob.ec/wp-content/uploads/downloads/2019/08/instructivo_adecuacion_salas_lmaterna_sprivado.pdf (accessed March 30, 2021).

Mirkovic, K. R., Perrine, C. G., Scanlon, K. S., and Grummer-Strawn, L. M. (2014). In the United States, a mother's plans for infant feeding are associated with her plans for employment. J. Hum. Lact. 30, 292–297. doi: 10.1177/0890334414535665

Monrouxe, L. V. (2016). “Theoretical insights into the nature and nurture of professional identities,” in Teaching Medical Professionalism: Supporting the Development of Professional Identity, 2nd Edn., eds R. Cruess, S. Cruess, and Y. Steinert (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press), 37–53.

Mosquera, P. S., Lourenço, B. H., Gimeno, S. G. A., Malta, M. B., Castro, M. C., Cardoso, M. A., et al. (2019). Factors affecting exclusive breastfeeding in the first month of life among Amazonian children. PLoS ONE 14, e0219801. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0219801

Navarro-Rosenblatt, D., and Garmendia, M. L. (2018). Maternity leave and its impact on breastfeeding: a review of the literature. Breastfeed. Med. 13, 589–597. doi: 10.1089/bfm.2018.0132

Novak, D. R. (2010). Democratizing qualitative research: photovoice and the study of human communication. Commun. Methods Meas. 4, 291–310. doi: 10.1080/19312458.2010.527870

Odom, E. C., Li, R., Scanlon, K. S., Perrine, C. G., and Grummer-Strawn, L. (2013). Reasons for earlier than desired cessation of breastfeeding. Pediatrics 131, e726–e732. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-1295

Oliver, D. G., Seovich, J. M., and Mason, T. L. (2005). Constraints and opportunities with interview transcription: towards reflection in qualitative research. Soc. Forces 84, 1273–1289. doi: 10.1353/sof.2006.0023

O'Reilly, A. (2014). “Feminist mothering,” in Mothers, Motherhood and Mothering Across Cultural Differences, ed A. O'Reilly (Bradford: Demeter Press), 183–206.

PAHO (2022). Infant Exclusive Breastfeeding in the Region of the Americas: Results From National Population-Based Surveys. Available online at: https://www.paho.org/en/enlace/exclusive-breastfeeding-infant-under-six-months-age

Palmér, L., Carlsson, G., Mollberg, M., and Nyström, M. (2012). Severe breastfeeding difficulties: existential lostness as a mother—women's lived experiences of initiating breastfeeding under severe difficulties. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Wellbeing 7, 1–11. doi: 10.3402/qhw.v7i0.10846

Prior, E., Santhakumaran, S., Gale, C., Philipps, L. H., Modi, N., and Hyde, M. J. (2012). Breastfeeding after cesarean delivery: a systematic review and meta-analysis of world literature. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 95, 1113–1135. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.111.030254

Riaz, S., and Condon, L. (2019). The experiences of breastfeeding mothers returning to work as hospital nurses in Pakistan: a qualitative study. Women Birth 32, e252–e258. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2018.06.019

Rich, A. (1995). Of Women Born: Motherhood as an Experience and Institution. New York, NY: W.W. Norton and Company.

Riggins, C., Rosenman, M. B., and Szucs, K. A. (2012). Breastfeeding experiences among physicians. Breastfeed. Med. 7, 151–154. doi: 10.1089/bfm.2011.0045

Rollins, N. C., Bhandari, N., Hajeebhoy, N., Horton, S., Lutter, C. K., Martines, J. C., et al. (2016). Why invest, and what it will take to improve breastfeeding practices? Lancet 387, 491–504. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(15)01044-2

Saldaña, J. (2021). The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers, 4th Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Sattari, M., Levine, D., Bertram, A., and Serwint, J. R. (2010). Breastfeeding intentions of female physicians. Breastfeed. Med. 5, 297–302. doi: 10.1089/bfm.2009.0090

Sattari, M., Levine, D., Neal, D., and Serwint, J. R. (2013). Personal breastfeeding behavior of physician mothers is associated with their clinical breastfeeding advocacy. Breastfeed. Med. 8, 31–37. doi: 10.1089/bfm.2011.0148

Steurer, L. M. (2017). Maternity leave length and workplace policies' impact on the sustainment of breastfeeding: global perspectives. Public Health Nurs. 34, 286–294. doi: 10.1111/phn.12321

Tracy, S. J. (2019). Qualitative Research Methods: Collecting Evidence, Crafting Analysis, Communicating Impact, 2nd Edn. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Turner, P. K., and Norwood, K. (2013). Unbounded motherhood: embodying a good working mother identity. Manage. Commun. Q. 27, 396–424. doi: 10.1177/0893318913491461

UNICEF (2005). Innocenti Declaration 2005: On Infant and Young Child Feeding. Available online at: https://www.unicef.org/nutrition/files/innocenti2005m_FINAL_ARTWORK_3_MAR.pdf (accessed March 30, 2021).

UNICEF (2020). Breastfeeding Support in the Workplace. Available online at: https://www.unicef.org/media/73206/file/Breastfeeding-room-guide.pdf (accessed March 30, 2021).

UNICEF and WHO (2017). Compendium of Case Studies of the Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative. Available online at: https://www.unicef.org/nutrition/files/BFHI_Case_Studies_FINAL.pdf (accessed March 30, 2021).

Wang, C., and Burris, M. A. (1997). Photovoice: concept, methodology, and use for participatory needs assessment. Health Educ. Behav. 24, 369–387. doi: 10.1177/109019819702400309

WHO (1990). Innocenti Declaration on the Protection, Promotion and Support of Breastfeeding. Available online at: https://healthydocuments.org/children/healthydocuments-doc33.pdf (accessed March 30, 2021).

World Alliance for Breastfeeding Action (2020). Our History. Available online at: https://waba.org.my/ourhistory/ (accessed March 30, 2021).

Young, C. (2020). Theorizing “deviant” embodiment and the act of breastfeeding. J. Gender Stud. 29, 685–693. doi: 10.1080/09589236.2020.1771291

Keywords: breastfeeding, health personnel, health communication, motherhood, identity

Citation: Mendoza-Gordillo MJ, Bates BR and Vivat B (2023) The (im)possibility of being a breastfeeding working mother: experiences of Ecuadorian healthcare providers. Front. Commun. 8:1153679. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2023.1153679

Received: 29 January 2023; Accepted: 24 July 2023;

Published: 16 August 2023.

Edited by:

Rebecca T. de Souza, San Diego State University, United StatesReviewed by:

Charee Mooney Thompson, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, United StatesCopyright © 2023 Mendoza-Gordillo, Bates and Vivat. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Maria J. Mendoza-Gordillo, bWptZW5kb3phQHB1Y2UuZWR1LmVj

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.