- 1Department of Journalism and Media Studies, Jackson State University, Jackson, MS, United States

- 2College of Communication & Information Sciences, University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa, AL, United States

A national survey of 314 Americans was employed to determine whether core forms of group identification (sport, political, and religious) predict one's likelihood to forgive a leader within that group for an intentional/preventable transgression. Three forms of transgressions (assault and battery, sex with a minor, stealing money) were presented as possible scenarios for leaders of sport, political, and religious groups. Sports leaders were more likely to be forgiven overall, with each of the three scenarios shifting levels of forgiveness; sex with a minor was more likely to be forgiven for sports figures, while stealing money was less likely to be forgiven for religious leaders. Unaffiliated individuals were less likely to forgive transgressions, with no differences between identified groups.

Introduction

Many forms of in-group allegiances shape public opinion. High on the list of potential influences includes perceived sport, political, and religious kinships. Within sport, Settimi (2020) reports on loyalties so great that Green Bay Packers fans are “willing to marry, divorce, remarry—even abandon their mothers—for a shot at tickets” (para. 5), while New England Patriots fans once used a GoFundMe campaign to pay for a million dollar fine after the Deflategate cheating scandal. Within politics, Graham and Svolik (2020) found that loyalty to one's party was more powerful than loyalty to democracy, as just 3.5% of American voters would cast a ballot against their parties' nominee if they supported efforts to disenfranchise other voters or supported other undemocratic policies. Meanwhile, religious tests are still so commonplace that no unabashed atheists have been elected to Congress, with six states still having laws barring nonbelievers from even running for office (Wing, 2017). Loyalties can even merge across the gaps of these three main forms of allegiance; in Alabama, Head Football Coach Nick Saban regularly places in the top 10 in voting for U.S. Presidential and Senate elections (Berkowitz, 2017) while former Auburn Head Football Coach Tommy Tuberville holds a U.S. Senate seat.

Such loyalties tinge virtually every part of society, particularly when social media makes group identification more prevalent than ever. Gil de Zuniga et al. (2017, p. 44) use the term “social media social capital” to contend for new resources (or lack thereof) arising from tie to societal resources. Moreover, loyalty to one's preferred identity group can result in perceived hypocrisy, as something can be considered abhorrent when an out-group member does it, yet somehow both acceptable and justifiable when the in-group does the same action (see Hing et al., 2002). This study seeks to determine the degree that allegiance to one's preferred sports, political, or religious group has to the willingness to forgive various forms of individual transgressions. Using Coombs (2007) typology of crisis responsibility and a national sample of 314 American respondents, three forms of transgressions are tested across these three types of loyalty: sport, political, and religious. The primary objective of the study is to answer the question of which transgressions are most forgivable or malleable depending on the identity affiliation of the transgressor.

Related literature

While disposition and, more specifically, exemplification, have been used to explain cognitive formulation of moral judgments (Matthews, 2019), moral disengagement theory (Bandura, 1999) explains processes in which people convince themselves that previous ethical standards either do not apply or must be amended within current value judgments. A variety of mechanisms are advanced to explain such forms of disengagement with advantageous comparison seemingly at the fore for judgments one could make regarding in-group and out-group principles of social identity (see Tajfel and Turner, 1985). Advantageous comparisons often are used to justify unjust actions, largely by justifying that another entity or group was worse or could provide a worse outcome.

In the conception of sport, political, and religious affiliations, moral disengagement could potentially explain how the unforgivable becomes pardonable. Egalitarianism comes to the fore in such a conception (Bandura's, 2002), allowing for the argument that an egregious act is morally justified either because of past wrongs (“Our quarterback was arrested for public intoxication, but the other team's is an alleged rapist”), because of comparative perceived harm (“The opposing political parties' policies are so damaging that voter suppression is justified”), or because one is inherently more noble or virtuous due to an in-group affiliation (“God will be the ultimate judge of my actions”). Familiarity with the content in which a person is committing the morally questionable act can reduce perceived guilt and negative affect (Hartmann and Vorderer, 2010), with social media now holding the potential to reinforce behaviors via shared identities (Kaakinen et al., 2020). Consequently, partly because of the ubiquity of both social media and conversations about the in-groups in question (sports, politics, and religion), the potential to morally disengage appears particularly high in modern times specifically when considering transgressions within the topics at hand.

Transgressions and crisis responsibility types

Of course, not all transgressions are created equal. Coombs's (2007) advances situational crisis communication theory (SCCT) largely based on this notion that each crisis presents a particular set of responsibilities for the transgressor and perceived optimal outcomes as judged by the general public. Part of this differentiation lies within the SCCT crisis typology, which includes (a) victim crises (perceived to be of minimal responsibility), (b) accident crises (perceived to be of low crisis responsibility), and (c) intentional/preventable crises (perceived to be of strong crisis responsibility).

Sometimes substantiation of a claim is all it takes to move from one pole of the typology to another; for instance, an unverified rumor of child abuse might be classified as a victim crisis, yet evidence-based rumors of the same child abuse would move to the preventable crisis status. Disposition subsequently becomes a key element within the activation of moral disengagement, as one presumably would be less inclined to believe a crisis-oriented transgression from one's favored sports team, political party, or religious membership than from one outside of these insulated affiliation factions.

Moral disengagement via sports fan identification

Group identity and perceived group membership are often reinforced as one ascribes belonging and social meaning from relationships within groups (Hogg, 2001; Hornsey, 2008). Sports fan identity works similarly as identified sports fans feel a psychological connection to sports teams and athletes that rarely wavers over time (Wann, 2006). Sports fandom may have important benefits for psychological health experienced through “the strong ties fans often feel for their chosen sports team” (Wann et al., 2003, p. 289). In-group affinities for team members, team officials, and the identified fanbase amplify as fan identity increases and coincides with an increased sense of communal purpose (van Driel et al., 2019). While fan identity can improve psychological well-being, these benefits are moderated by threats to identity, which can occur when athletes commit transgressions during or away from competition (Wann, 2006).

Fans are forced to process and reconcile negative behaviors that contradict their positive perceptions of athletes on their favorite teams (Dietz-Uhler et al., 2002). In some instances, fans morally disengage by rationalizing the behavior and attributing it to outside forces beyond the athlete's control (Sanderson and Emmons, 2014). After sprinter Ben Johnson was disqualified from the 1988 Summer Olympics for taking performance-enhancing drugs, Ungar and Sev'er (1989) found that individuals were more likely to attribute his transgressions to situational factors (e.g., unknowingly taking steroids) than assign culpability to the sprinter himself. A related study determined that baseball fans on a Texas Rangers discussion forum were highly likely to forgive outfielder Josh Hamilton for an alcohol relapse through support, “addiction is hard” narratives, human condition attributions, and justification (Sanderson and Emmons, 2014). Conversely, some fans (predominantly of other our-group teams) withheld forgiveness due to perceptions of Hamilton's character flaws (e.g., alcohol and drug addiction, perceived incongruence in practicing Christianity) and were unwilling to chance recidivism.

Because “athletes serve as idealized role models for sports fans and, in many cases, are held to unrealistic expectations” (Sanderson and Emmons, 2014, p. 38), moral disengagement could most often lead to fan forgiveness when transgressions resonate with a fan's own experiences, making perceptions of similarity paramount and even the core communication choices (see Burgers et al., 2015) heavily predicated on in-group connections. Thus, the present study posits the following hypothesis:

H1: Higher sports fan identification will result in greater willingness to forgive sports leader transgressions.

Additionally, the severity of the transgression is particularly impactful at influencing a forgiveness response (Merolla, 2008). In March 2021, 22 massage therapists filed lawsuits against Houston Texans Quarterback Deshaun Watson alleging inappropriate conduct and sexual assault (Barshop, 2021). While he contends that these encounters were consensual, the seriousness of the allegations has caused him to lose sponsorships and suspend relationships with companies such as Nike, Reliant Energy, and Beats by Dre (Florio, 2021). It stands to reason that the nature of these transgressions is too severe for even the most diehard football fans to forgive. Thus, the following research question was developed to better understand the impact of transgression type on fan forgiveness:

RQ1: To what degree does the ability to forgive a sports figure's transgressions differ by type of preventable crisis?

Moral disengagement via political identification

Political identification, along with partisanship, refers to the degree in which an individual identifies with a given political entity and their beliefs (Bankert et al., 2017). To measure the levels of political identification and partisanship that an individual has with a given political party, the Partisan Identity Scale (PIS; Bankert et al., 2017) uses eight elements of identification to establish a level of connectedness that an individual feels with their party. When examining identification with forgiveness, political forgiveness is unique in a sense that the process demands accountability (Wabanhu, 2008). The public seeks retribution for political transgressions, rather than reparation and forgiveness, leaving public forgiveness hard to obtain. Wabanhu (2008) suggests that “on the socio-political level intentional and sustained efforts should always be made to painstakingly work for healing, reparation, forgiveness and for reconciliation rather than for letting retributive justice take its course” (p. 298), alluding to the difficult process for forgiveness to occur in socio-political situations.

Although forgiveness may be hard to come by in the socio-political sphere, the 2020 U.S. presidential election illustrated that most transgressions made by in-group candidates could be opportunities to morally disengage to the point that major flaws could be reduced to foibles. For example, during the 2020 presidential debate, former President Donald Trump stated, in reference to a white-supremacy group, “Proud Boys—stand back and stand by” (Subramanian and Culver, 2020, para. 55). During the same timeframe, President Joe Biden told African American host Charlamagne, “If you have a problem figuring out whether you're for me or Trump, then you ain't black” (Bradner et al., 2020, para. 6) while being interviewed on The Breakfast Club. Each of these presidential candidates made borderline or overtly offensive and derogatory comments over the lifetime of their political careers, yet over 81 million Americans still voted for Joe Biden, and over 74 million Americans still voted for Donald Trump in the 2020 U.S. presidential election (DeSilver, 2020). Likely, the egalitarianism prong of moral disengagement (Bandura's, 2002) provided a justification because the moral transgressions made by a political leader can be pardoned because the individual that identifies with that political leader views the moral transgressions of the other political leader to be more severe. Even more so, it would be logical to assume that the more an individual identifies with a given political leader, the more likely the individual would be to forgive their political leader of their transgressions. Thus, the following hypothesis is posited:

H2: Higher political identification will result in greater willingness to forgive political leader transgressions.

Considering that there are numerous transgressions that can be made by political leaders (from slanderous language to criminal offenses), the level of forgiveness that an individual may give their political leader may differ based on the severity of the transgression. Thus, the following question is asked to determine if forgiveness levels differ by transgression type:

RQ2: To what degree does the ability to forgive a political figure's transgressions differ by type of preventable crisis?

Moral disengagement via religious identification

In terms of social identity, religion provides individuals with a group for belonging and a common set of values that characterize membership (Ysseldyk et al., 2010), where religious identification refers to an individual's self-identification with a religion (Hayes, 1995). To measure the strength of religious identification, the Centrality of Religiosity Scale (CRS; Huber and Huber, 2012) uses the five theoretical elements of religion to predict its salience in individual personality. In regard to moral disengagement, religious identification affects attitudes toward radicalization and violent extremism (Aly et al., 2014) and is used to justify unethical behavior in shifting the responsibility of the behavior (Hinrichs et al., 2012). In terms of transgressions, religiosity also affects individuals' willingness to forgive transgressions (Fox and Thomas, 2008; Sheldon, 2014). Loyalty in parasocial relationships may lead individuals to forgive transgressions, (e.g., celebrities; Finsterwalder et al., 2017). For religious communities, individuals tend to judge members of the out-group greater than those of the in-group for minor transgressions (Bettache et al., 2019). Taking these findings into account, this study predicts that religious identification will predict transgression forgiveness of religious leaders:

H3: Higher religious identification will result in greater willingness to forgive religious leader transgressions.

While religious ideals have been used to justify conduct (Cartledge et al., 2015), if the offense violates religious beliefs or values, it is more difficult for individuals to forgive transgressions (Grubbs et al., 2015). The severity of the offense also affects forgiveness (Cohen et al., 2006). In times of crisis, religiosity often serves as a coping mechanism for individuals (Lim et al., 2019). Additionally, church leaders may play a role in influencing attitudes toward a crisis among their congregation through communication (Khosrovani et al., 2008; Campbell and Wallace, 2015). However, when a religious institution is at fault for a crisis, such as the Catholic Church's handling of the sex abuse scandal, it questions the role of faith and tradition in both the Church's handling and response toward a crisis (Faggioli, 2019). The American public, especially members of the Catholic Faith, were horrified and angered by the actions of authority figures with the Church (Steinfels, 2004), indicating that religious identification may offer little weight in forgiving religious organizations at fault for major crises. Therefore, the present study postulates:

RQ3: To what degree does the ability to forgive a religious figure's transgressions differ by type of preventable crisis?

In considering the influence of identification of religion, politics, and sports, the present study also asks:

RQ4: Which type of identification (sports, political, religious) is more likely to result in forgiving transgressions?

RQ5: Are there certain types of identification within each grouping (sports, political, religious) that are more likely to forgive transgressions?

Methods

Participants

To answer the three hypotheses and five research questions, an IRB-approved 3 (leader) by 3 (transgression) between-subjects experiment was administered to 314 U.S. adults in spring 2021. The sample included 314 participants aged 18 to 92 (M = 51.694, SD = 15.960). A total of 188 (59.873%) participants identified as female, 122 (38.854%) participants identified as male, 2 (0.637%) participants identified as non-binary/third gendered, and 2 (0.637%) participants did not disclose their gender. The sample included 255 (81.210%) White, 32 (10.191%) Black or African American, 13 (4.140%) Asian, 4 (1.274%) Native American, 1 (0.318%) Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, and 9 (2.866%) other/mixed raced participants. The highest educational level completed varied, as 10 (3.185%) indicated that they had less than a high school degree, 80 (25.478%) had a high school degree or equivalency, 90 (28.662%) had some college, 26 (8.280%) had a 2-year degree, 65 (20.701%) had a 4-year degree, 34 (10.828%) had a professional degree (M.A., M.S., J.D., or M.D.), and 9 (2.866%) had a doctoral degree.

Procedures

The experiment was embedded into an online survey administered through Qualtrics Panels. Each participant was randomly assigned to one of three different groups, where participants responded with levels of forgiveness to hypothetical preventable transgressions made by their preferred sports leader, preferred political leader, and preferred religious leader. The three preventable transgressions were assault and battery, engaging in sex with a minor, and stealing money from their organization. The first group of participants (n = 105) responded to their preferred sports leader accused of assault and battery, their preferred political leader accused of engaging in sex with a minor, and their preferred religious leader accused of stealing money from their identified religious organization. The second group of participants (n = 103) responded to their preferred sports leader accused of engaging in sex with a minor, their preferred political leader stealing money from their identified political organization, and their preferred religious leader accused of assault and battery. The third group of participants (n = 106) responded to their preferred sports leader accused of stealing money from their identified sports organization, their preferred political leader accused of assault and battery, and their preferred religious leader accused of engaging in sex with a minor.

After reading and agreeing to the details outlined in the informed consent, participants completed a survey with questions about their sports identity, political identity and affiliation, religious identity and affiliation, as well as other questions related to violent extremism and violent radicalization. Participants were compensated in the form of points (roughly $3US in value) that could be reimbursed through the Qualtrics Panels website (Baird, 2021).

Measures

Identification

One primary independent variable was identification level across the three affiliation types. All measures can be found within the Appendix.

Sport identification

Sport identification was measured using Wann and Branscombe's (1993) Sport Spectator Identification scale (Cronbach's α = 0.956), utilizing a seven-item, seven-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The higher the score, the more an individual identifies with their preferred sports team (M = 3.783, SD = 1.814).

Political identification

Political identification was operationalized as the level of identification that a participant has with their preferred political party. Before political identification was measured, participants were asked to identify their preferred political party. After data collection, the political party that individuals identified with were categorized into three groups, Republicans (n = 91, 28.981%), Democrats (n = 124, 39.490%), and third parties including independents (n = 99, 31.529%). Bankert et al.'s (2017) eight-item, seven-point Likert Political Partisanship Scale (Cronbach's α = 0.894) ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) was used to measure political identification. Higher scores indicated the more identification a participant had with their preferred political party (M = 4.178, SD = 1.170).

Religious identification

Religious identification was operationalized as the level of identification that a participant has with their preferred religious organization. Before religious identification was measured, participants were asked to identify the religious organization with which they most align. After data collection, religious organizations were categorized into three groups, Christians (n = 189, 60.191%), non-Christians (n = 39, 12.420%), and no religious affiliation (n = 86, 27.389%). An adapted six-item, seven-point Likert Centrality of Religiosity Scale (Huber and Huber, 2012; Cronbach's α = 0.9063) ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) was used to measure religious identification. Higher scores indicated more identification a participant had with their preferred religious organization (M = 4.740, SD = 1.635). All independent variables were measured using an averaged scale.

Transgression level

The other independent variable was preventable transgression type (assault and battery, sex with a minor, and stealing money). Preventable transgressions are defined by Coombs and Holladay (2002) as actions where a person or entity is presumed to be of high crisis responsibility, specifically in situations of human error accidents/product harm and for personal or organizational misdeeds. As a result, three scenarios matching these parameters were selected for the study: (a) assault and battery, (b) sex with a minor, and (c) stealing money.

Forgiveness

Forgiveness was operationalized as the degree to which an individual maintains identification toward their preferred organization even when informed they were responsible for a high responsibility transgression. Forgiveness was measured using a four-item, seven-point Likert scale developed by the authors administered for each type of leader (sports leader, M = 4.084, SD =1.367, α = 0.787; political leader, M = 3.943, SD = 1.386, α = 0.785; religious leader, M = 3.810, SD = 1.550, α = 0.844). An overall forgiveness level was determined by averaging the three forgiveness levels for each leader (M = 3.946, SD = 1.240). Initially, the scale contained five-items; however, one item was dropped to achieve an acceptable reliability alpha. George and Mallery (2003) explain that Cronbach's alpha scores that range from 0.7 to 0.79 are acceptable, 0.8–0.89 are good, and above 0.9 are excellent. All dependent variables used an averaged scale.

Results

In order to study the relationship between sport fan forgiveness and willingness to forgive sports leader transgressions, a regression analysis was performed. Higher levels of sports fans identification resulted in a greater willingness to forgive sports leader transgressions, b = 0.344, t (312) = 9.080, p < 0.001. Higher identification scores indicate more identification with their preferred sports team. Hypothesis 1 was supported.

Hypothesis 2 predicted that higher political identification will result in greater willingness to forgive political leader transgressions. To answer this question, a regression analysis was performed. Higher levels of political identification resulted in a greater willingness to forgive political leader transgressions, b = 0.531, t (312) = 8.86, p < 0.001. Higher identification scores indicate more identification with their preferred political party. Hypothesis 2 was supported.

Hypothesis 3 posited that higher religious identification will result in greater willingness to forgive religious leader transgressions. To answer this question, a regression analysis was performed. Higher levels of religious identification resulted in a greater willingness to forgive religious leader transgressions, b = 0.376, t (312) = 7.64, p < 0.001. Higher identification scores indicate more identification with their preferred religious organization. Hypothesis 3 was supported.

The first three research questions pertained to potential differences in willingness to forgive for each of the three high crisis responsibility scenarios. Results pertaining to each of these scenarios by sport (RQ1), political (RQ2), and religious (RQ3) leader are outlined in Table 1.

Research Question 1 queried whether the ability to forgive sports figure transgressions differs by type of preventable crisis. To answer this question, an ANOVA was performed. Transgressions of assault and battery (M = 4.017), sex with a minor (M = 4.010), and stealing money from their organization (M = 4.222) did not differ in levels of forgiveness, F(2, 311) = 0.816, η2 = 0.005, p = 0.443. This indicates that the type of transgression did not influence levels of forgiveness for sports leaders.

Research Question 2 queried whether the ability to forgive political figure transgressions differs by type of preventable crisis. To answer this question, an ANOVA was performed. The transgression of engaging in sex with a minor (M = 3.660) resulted in significantly lower levels of forgiveness than the transgressions of assault and battery (M = 4.068) and stealing money from their organization (M = 4.104), F(2, 311) = 3.376, η2 = 0.021, p = 0.035. This indicates that individuals are less likely to forgive a political leader for engaging in sex with a minor when compared to assault and battery or stealing money from their organization.

Research Question 3 asked whether the ability to forgive religious figure transgressions differs by type of preventable crisis. To answer this question, an ANOVA was performed. The transgressions of assault and battery (M = 4.024), engaging in sex with a minor (M = 3.623), and stealing money from their organization (M = 3.788) did not differ in levels of forgiveness, F(2, 311) = 1.778, η2 = 0.011, p = 0.171. This indicates that the type of transgressions did not influence levels of forgiveness for religious leaders.

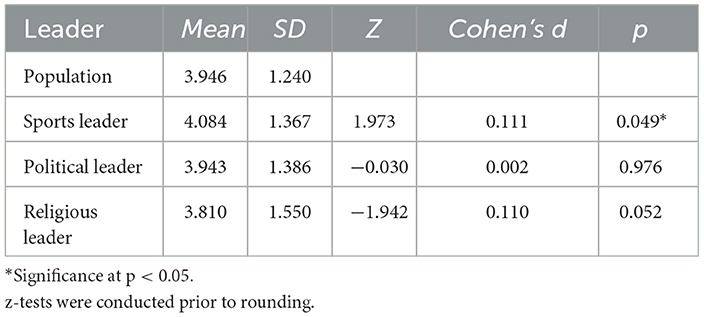

Research Question 4 asked which type of identification (sports, political, religious) is more likely to result in forgiving transgressions. To answer this question, z-tests were performed. The population mean average for forgiveness (M = 3.946, SD = 1.240) was tested against the mean average of each leader's forgiveness to determine if one leader was more likely to be forgiven for all transgressions compared to the overall population average of forgiveness. Table 2 highlights differences from population mean for each of these three identification groups.

As Table 2 highlights, sports leaders (M = 4.084, SD =1.367) were significantly more likely to be forgiven for transgressions when compared to the population mean, z = 1.973, p = 0.049. Political leaders (M = 3.943, SD = 1.386) did not differ on levels of forgiveness when compared to the population mean, z = −0.030, p = 0.976. Religious leaders (M = 3.810, SD = 1.550) did not differ on levels of forgiveness when compared to the population mean, z = −1.942, p = 0.052. Thus, sports leaders represented the identification that remained most stable in light of transgressions.

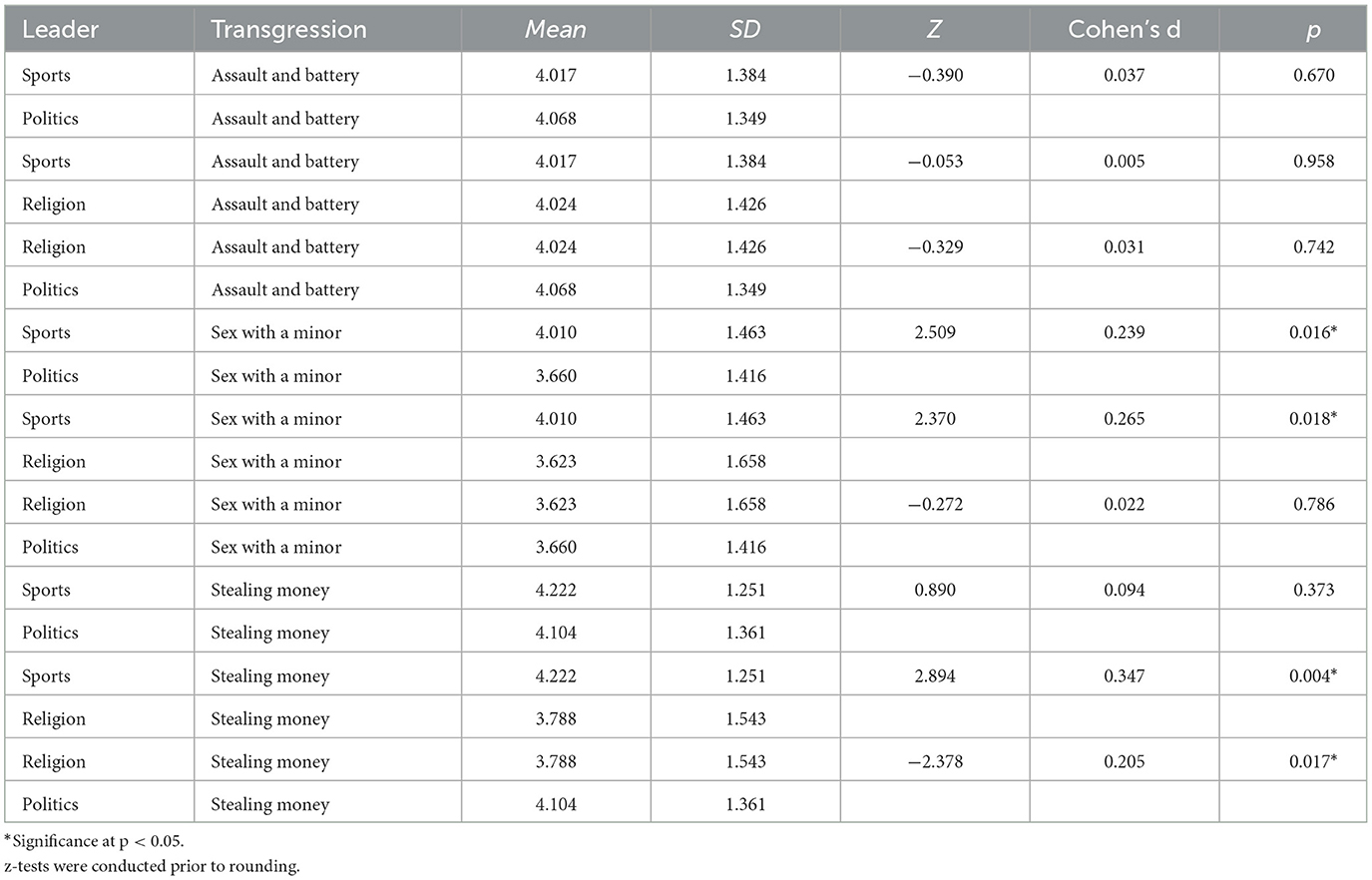

Relating to whether specific transgressions were significantly different by identification type, Table 3 outlines these results.

Table 3. Two-tailed z-test table of leaders' transgression forgiveness levels compared to one another.

As Table 3 reveals, multiple z-tests were performed. When considering forgiveness of assault and battery, sports leaders (M = 4.017) and political leaders (M = 4.068) did not differ (z = −0.390, p = 0.670); sports leaders (M = 4.017) and religious leaders (M = 4.024) did not differ (z = −0.053, p = 0.958); religious leaders (M = 4.024) and political leaders (M = 4.068) did not differ (z = −0.329, p = 0.742).

When considering engaging in sex with a minor, participants were more likely to forgive sports leaders (M = 4.010) than political leaders (M = 3.660; z = 2.509, p = 0.016), and participants were more likely to forgive sports leaders (M = 4.010) than religious leaders (z = 3.623, p = 0.018). Religious leaders (M = 3.623) and political leaders (M = 3.660) did not differ in forgiveness scores when presented with the engaging in sex with a minor scenario (z = −0.272, p = 0.786).

When considering stealing money from their organization, there was no difference between sports leaders (M = 4.222) and political leaders (M = 4.104; z = 0.890, p = 0.373). Participants were less likely to forgive religious leaders (M = 3.788) than sports leaders (M = 4.222; z = 2.894, p = 0.004) and were less likely to forgive religious leaders (M = 3.788) than political leaders (M = 4.104) for stealing money from their organization (z = −2.378, p = 0.017).

Research Question 5 queried whether there are certain types of identification within each grouping (sports, political, religious) that are more likely to forgive transgressions. To answer this question, multiple ANOVAs were performed.

Those who are highly-identified sports fans (M = 4.524) are more likely to forgive transgressions than moderately-identified sports fans (M = 3.870), which are more likely to forgive transgressions than lowly-identified fans (M = 3.557), F(2, 311) = 16.594, η2 = 0.096, p < 0.001.

Those who identify with a political third-party (M = 3.600) are less likely to forgive transgressions than Republicans (M = 4.148) or Democrats (M = 4.073); Republicans and Democrats did not differ from one another, F (2, 311) = 5.890, η2 = 0.036, p < 0.001.

Those who do not identify with a religion (M = 3.474) are less likely to forgive transgressions than Christians (M = 4.110) or non-Christians (M = 4.188); Christians and non-Christians did not differ from one another, F(2, 311) = 9.086, η2 = 0.055, p < 0.001.

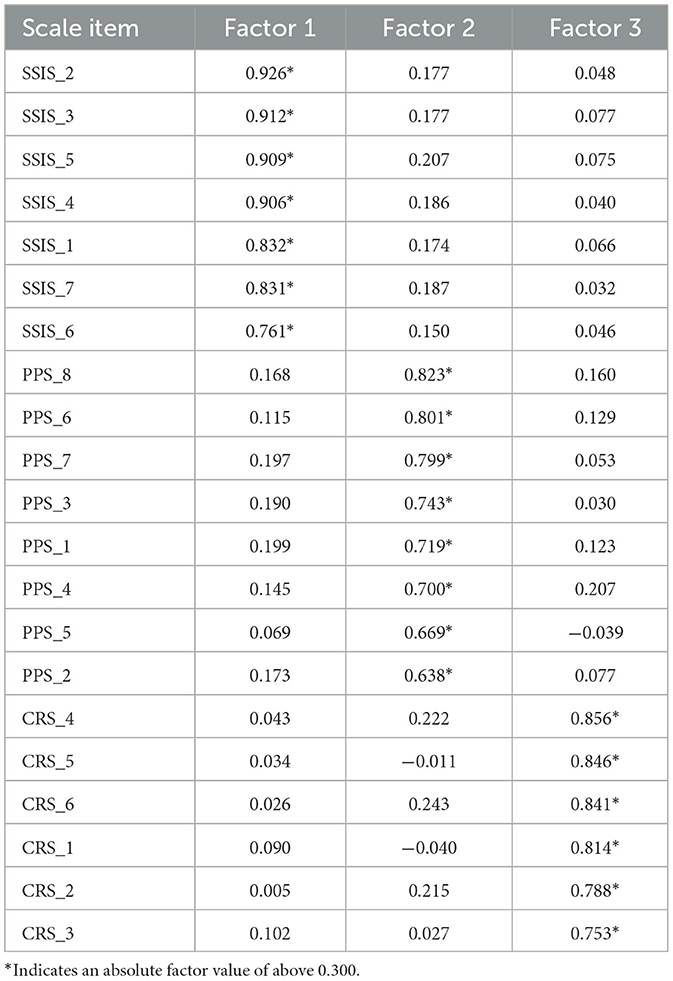

As a post hoc analysis, a CFA was conducted to confirm that the three types of identification (sports, politics, and religion) were empirically different. The results are presented in Table 4.

As Table 4 shows, results indicated that each factor loaded properly into their respective measurements, thus, identifying them as three separate identities.

Discussion

The core relationship between identification and subsequent willingness to forgive transgressions was revealed within all three identity groups, but the manner in which the forgiveness unfolded differed in intriguing and informative ways. Loyalty was conditional depending on identification with a given sport, political, or religious leader, yet sports leaders were the most likely to be forgiven when compared to either of the other two cases. This likely could be because of the presumed needed moral component to the other two types of leaders. Tamborini et al. (2018) advanced that fictional narrative writers may wish to employ external factors to signify justifications for a character's harmful acts. Here, we find that internal factors—namely group identification—function similarly in hypothetical nonfiction realms. Nearly three decades after basketball star Charles Barkley famously used a Nike commercial to proclaim, “I am not a role model” (Eisenberg, 2019), it appears such lessened expectations manifest in a lower expectation for leading sports figures than for political and religious figures.

Since the study exclusively employed preventable crises from the Coombs's (2007) typology, strong crisis responsibility was presumed in each of the three tested cases. Each of the cases revealed fissures between the three types of identification. Sex with a minor was significantly more likely to be forgiven for sports figures; stealing money was least likely to be forgiven for religious leaders. Meanwhile, no differences were detected in the overall likelihood of forgiving assault and battery, an interesting outcome given that the bar fight seems to be a staple baked into the expectations of an athlete (see Rae et al., 2017), and presumably would be less expected of a politician or religious leader.

For all three types of potential identification, the less identified one was with the dominant strain of identification, the less forgiving of the transgression the participant was likely to be. Within politics, this meant independents and identification with third parties made one less forgiving; within religion, the forgiveness exhibited by Christians did not differ from other affiliated denominations but was significantly higher than for those with no religious identification.

Adopting a theoretical perspective, moral disengagement (Bandura, 1999) appears to be strongly related to one's group status, whether that means in-group or out-group distinctions. Moreover, it appears that even the act of identification represents the strongest predictor of transgression forgiveness. This study highlights how forgiveness was not predicated on whether the person was a Democrat or Republican but was predicated on whether one's political leanings resided within one of these major in-groups or not. Similarly, affiliating with a religious denomination made one more likely to forgive a transgression, but the actual religious denomination—at least when comparing Protestant Christians to a combination of all other denominations—mattered little. Hartmann and Vorderer (2010) found evidence of moral disengagement within violent video games, concluding that violent actions could be justified because of the environment in which they unfold. This study takes such findings a step further, highlighting that it appears the social identity one brings into such equations seemingly matters as well. In sum, it is not just the environment one occupies that facilitates moral disengagement; it is also the core in-groups they bring embody within such environments that matter.

Bandura (2002) inclusion of egalitarianism informs this study as well, showing that in-group identification seemingly fosters forgiveness, presumably at least in part because a sports/political/religious leader represents their “team.” Future research should employ Benoit (2000) concept of differentiation to determine whether one's rivals/out-groups are judged more harshly and, if so, whether these judgments unfold differently across varying preventable crisis scenarios.

In terms of practical implications, relationships with image repair strategies from Benoit's (2000) can be implemented for each of these forms of identity groups. For instance, a sports figure could use these results to determine whether a fanbase is likely to be open to a particular form of crisis response, opting for mortification over corrective action depending on the type of preventable transgression as well as the level of loyalty within a fan base. The same would be the case in political and religious realms. Moreover, ramifications could also be utilized when identifying spokespersons when seeking to attain unity in times of crisis. The results here show that a political or religious figure is less likely to receive forgiveness than a sports figure, potentially making the sports figure a more optimal choice for sponsorship and public messaging seeking to assuage schisms within society.

Turning more formally to directions for subsequent study, the present study utilized only preventable crises because of their inherent high level of crisis responsibility ascribed to the actor. However, future work should examine other parts of the Coombs's (2007) typology, including victim and accident crises, to understand how lower levels of responsibility interplay with identified in-groups.

Additionally, future work should endeavor to uncouple constructs that appear closely related to this form of identification-based crisis scholarship, yet likely do not operationalize as synonymous terms. Thus, identification relates to loyalty, yet is demonstrably not the same construct. Similarly, loyalty to an actor/object makes one more likely to forgive transgressions, but likely is not the same as identification to that actor/object. Future scholarship could delineate these differences.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by University of Alabama IRB. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Aly, A., Taylor, E., and Karnovsky, S. (2014). Moral disengagement and building resilience to violent extremism: an education intervention. Stud. Conflict Terror. 37, 369–385. doi: 10.1080/1057610X.2014.879379

Bandura, A. (1999). Moral disengagement in the perpetration of inhumanities. Person. Soc. Psychol. 3, 193–209. doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr0303_3

Bandura, A. (2002). Selective moral disengagement in the exercise of moral agency. J. Moral Educ. 31, 101–119. doi: 10.1080/0305724022014322

Bankert, A., Huddy, L., and Rosema, M. (2017). Measuring partisanship as a social identity in multi-party systems. Pol. Behav. 39, 103–132. doi: 10.1007/s11109-016-9349-5

Barshop, S. (2021). Rusty Hardin: Deshaun Watson never engaged in acts with plaintiffs that weren't ‘mutually desired.' ESPN. Available online at: https://www.espn.com/nfl/story/_/id/31224333/rusty-hardin-deshaun-watson-never-engaged-acts-plaintiffs-mutually-desired (accessed July 31, 2023).

Benoit, W. (2000). Another visit to the theory of image restoration strategies. Commun. Q. 48, 40–43. doi: 10.1080/01463370009385578

Berkowitz, S. (2017). Nick Saban Received at Least 421 Write-in Votes in Alabama Senate Election. USA Today. Available online at: https://www.usatoday.com/story/sports/ncaaf/2017/12/29/nick-saban-received-least-421-write-votes-alabama-senate-election/991272001/ (accessed July 31, 2023).

Bettache, K., Hamamura, T., Amrani Idrissi, J., Amenyogbo, R. G. J., and Chiu, C. (2019). Monitoring moral virtue: when the moral transgressions of in-group members are judged more severely. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 50, 268–284. doi: 10.1177/0022022118814687

Bradner, E., Mucha, S., and Saenz, A. (2020). Biden: 'if You Have a Problem Figuring Out Whether You're for Me or Trump, then You Ain't Black'. CNN. Available online at: https://www.cnn.com/2020/05/22/politics/biden-charlamagne-tha-god-you-aint-black/index.html (accessed July 31, 2023).

Burgers, C., Beukeboom, C. J., Kelder, M., and Peeters, M. M. E. (2015). How sports fans forge intergroup competition through language: the case of verbal irony. Hum. Commun. Res. 41, 435–457. doi: 10.1111/hcre.12052

Campbell, A. D., and Wallace, G. (2015). Black megachurch websites: An assessment of health content for congregations and communities. Health Commun. 30, 557–565. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2013.872964

Cartledge, S. M., Bowman-Grieve, L., and Palasinski, M. (2015). The mechanisms of moral disengagement in George W. Bush's “war on terror” rhetoric. Qual. Rep. 20, 1905–1921. doi: 10.46743/2160-3715/2015.2401

Cohen, A. B., Malka, A., Rozin, P., and Cherfas, L. (2006). Religion and unforgivable offenses. J. Person. 74, 85–118. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2005.00370.x

Coombs, W. (2007). Ongoing Crisis Communication: Planning, Managing and Responding. 2nd ed. Newcastle upon Tyne: Sage.

Coombs, W. T., and Holladay, S. J. (2002). Helping crisis managers protect reputational assets: initial tests of the situational crisis communication theory. Manag. Commun. Q. 16, 165–186. doi: 10.1177/089331802237233

DeSilver, D. (2020). Biden's Victory Another Example of How Electoral College Wins are Bigger Than Popular Vote Ones. Pew Research Center. Available online at: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/12/11/bidens-victory-another-example-of-how-electoral-college-wins-are-bigger-than-popular-vote-ones/ (accessed July 31, 2023).

Dietz-Uhler, B., End, C., Demakakos, N., Dickirson, A., and Grantz, A. (2002). Fans' reactions to law-breaking athletes. Int. J. Sport Psychol. 6, 160–170.

Eisenberg, J. (2019). Iconic Sports Commercials: Charles Barkley's 'I am not a role model'. Yahoo! Sports. Available online at: https://www.yahoo.com/lifestyle/iconic-sports-commercials-charles-barkleys-i-am-not-a-role-model-055726035.html (accessed July 31, 2023).

Faggioli, M. (2019). The Catholic sexual abuse crisis as a theological crisis: emerging issues. Theol. Stud. 80, 572–589. doi: 10.1177/0040563919856610

Finsterwalder, J., Yee, T., and Tombs, A. (2017). Would you forgive Kristen Stewart or tiger woods or maybe lance armstrong? Exploring consumers' forgiveness of celebrities' transgressions. J. Mark. Manag. 33, 1204–1229. doi: 10.1080/0267257X.2017.1382553

Florio, M. (2021). More Sponsors Part Ways With Deshaun Watson. NBC Sports. Available online at: https://profootballtalk.nbcsports.com/2021/04/07/more-sponsors-part-ways-with-deshaun-watson/ (accessed July 31, 2023).

Fox, A., and Thomas, T. (2008). Impact of religious affiliation and religiosity on forgiveness. Aust. Psychol. 43, 175–185. doi: 10.1080/00050060701687710

George, D., and Mallery, P. (2003). SPSS for Windows Step by Step: A Simple Guide and Reference. 11.0 Update. 4th ed. Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon.

Gil de Zuniga, H., Barnidge, M., and Scherman, A. (2017). Social media social capital, offline social capital, and citizenship: exploring asymmetrical social capital effects. Pol. Commun. 34, 44–68. doi: 10.1080/10584609.2016.1227000

Graham, M. H., and Svolik, M. W. (2020). Democracy in America?: Partisanship, polarization, and the robustness of support for democracy in the United States. Am. Pol. Sci. Rev. 114, 392–409. doi: 10.1017/S0003055420000052

Grubbs, J. B., Exline, J. J., Pargament, K. I., Hook, J. N., and Carlisle, R. D. (2015). Transgression as addiction: religiosity and moral disapproval as predictors of perceived addiction to pornography. Arch. Sex. Behav. 44, 125–136. doi: 10.1007/s10508-013-0257-z

Hartmann, T., and Vorderer, P. (2010). It's okay to shoot a character: moral disengagement in violent video games. J. Commun. 60, 94–119. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.2009.01459.x

Hayes, B. C. (1995). The impact of religious identification on political attitudes: an international comparison. Soc. Rel. 56, 177–194. doi: 10.2307/3711762

Hing, L. S. S., Li, W., and Zanna, M. P. (2002). Inducing hypocrisy to reduce prejudicial responses among aversive racists. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 38, 71–78. doi: 10.1006/jesp.2001.1484

Hinrichs, K. T., Wang, L., Hinrichs, A. T., and Romero, E. J. (2012). Moral disengagement through displacement of responsibility: the role of leadership beliefs. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 42, 62–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.2011.00869.x

Hogg, M. A. (2001). A social identity theory of leadership. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 5, 184–200. doi: 10.1207/S15327957PSPR0503_1

Hornsey, M. J. (2008). Social identity theory and self-categorization theory: a historical review. Soc. Person. Psychol. Comp. 2, 204–222. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2007.00066.x

Huber, S., and Huber, O. W. (2012). The centrality of religiosity scale (CRS). Religions 3, 710–724. doi: 10.3390/rel3030710

Kaakinen, M., Sirola, A., Savolainen, I., and Oksanen, A. (2020). Shared identity and shared information in social media: development and validation of the identity bubble reinforcement scale. Media Psychol. 23, 25–51. doi: 10.1080/15213269.2018.1544910

Khosrovani, M., Poudeh, R., and Parks-Yancy, R. (2008). How African-American ministers communicate HIV/AIDS-related health information to their congregants: a survey of selected black churches in Houston, TX. Ment. Health Rel. Cult. 11, 661–670. doi: 10.1080/13674670801936798

Lim, J. R., Liu, B. F., Egnoto, M., and Roberts, H. A. (2019). Individuals' religiosity and emotional coping in response to disasters. J. Conting. Crisis Manag. 27, 331–345. doi: 10.1111/1468-5973.12263

Matthews, N. L. (2019). Detecting the boundaries of disposition bias on moral judgments of media characters' behaviors using social judgment theory. J. Commun. 69, 418–441. doi: 10.1093/joc/jqz021

Merolla, A. J. (2008). Communicating forgiveness in friendships and dating relationships. Commun. Stud. 59, 114–141. doi: 10.1080/10510970802062428

Rae, C., Billings, A. C., and Brown, K. A. (2017). On-field perceptions of off-field deviance: exploring social and economic capital within sport-related transgressions. In: Billings, A. C., and Brown, K. A., editors. Evolution of the Modern Sports Fan: Communicative Approaches. Blue Ridge Summit, PA: Lexington Press. p. 147–166

Sanderson, J., and Emmons, B. (2014). Extending and withholding forgiveness to Josh Hamilton: exploring forgiveness within parasocial interaction. Commun. Sport 2, 24–47. doi: 10.1177/2167479513482306

Settimi, C. (2020). America's Most Passionate Sports Fans. Forbes. Available online at: https://www.forbes.com/sites/christinasettimi/2020/05/06/americas-most-passionate-sports-fans-2020/?sh=79b666f32365 (accessed July 31, 2023).

Sheldon, P. (2014). Religiosity as a predictor of forgiveness, revenge, and avoidance among married and dating adults. J. Commun. Rel. 37, 20–29.

Steinfels, P. (2004). A People Adrift: The Crisis of the Roman Catholic Church in America. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster.

Subramanian, C., and Culver, J. (2020). Donald Trump Sidesteps Call to Condemn White Supremacists - and the PROUD Boys Were 'extremely excited' About It. Available online at: https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/politics/elections/2020/09/29/trump-debate-white-supremacists-stand-back-stand-by/3583339001/ (accessed July 31, 2023).

Tajfel, H., and Turner, J. C. (1985). The Social Identity Theory of Intergroup Behavior. In: Worchel, S. and Austin, W. G., editors. Psychology of Intergroup Relations. 2nd ed. Binfield: Nelson-Hall. p. 7–24.

Tamborini, R., Grall, C., Prabhu, S., Hofer, M., Novotny, E., Hahn, L., et al. (2018). Using attribution theory to explain the affective dispositions of tireless moral monitors toward narrative characters. J. Commun. 68, 842–871. doi: 10.1093/joc/jqy049

Ungar, S., and Sev'er, A. (1989). “Say it ain't so, Ben”: attributions for a fallen hero. Soc. Psychol. Q. 52, 207–212. doi: 10.2307/2786715

van Driel, I. I., Gantz, W., and Lewis, N. (2019). Unpacking what it means to be—or not be—a fan. Commun. Sport 7, 611–629. doi: 10.1177/2167479518800659

Wabanhu, E. (2008). Forgiveness and reconciliation: personal, interpersonal and socio-political perspectives. AFER 50, 284–301.

Wann, D. L. (2006). Understanding the positive social psychological benefits of sport team identification: the team identification–social psychological health model. Group Dynam. Theory Res. Pract. 10, 272–296. doi: 10.1037/1089-2699.10.4.272

Wann, D. L., and Branscombe, N. R. (1993). Sports fans: Measuring degree of identification with their team. Int. J. Sport Psychol. 24, 1–17.

Wann, D. L., Dimmock, J., and Grove, J. R. (2003). Generalizing the team identification–psychological health model to a different sport and culture: the case of Australian rules football. Group Dynam. Theory Res. Pract. 7, 289–296. doi: 10.1037/1089-2699.7.4.289

Wing, N. (2017). 11 Things Atheists Couldn't do Because They Didn't Believe in God. Huffington Post. Available online at: https://www.huffpost.com/entry/atheists-discrimination_n_4413593 (accessed July 31, 2023).

Ysseldyk, R., Matheson, K., and Anisman, H. (2010). Religiosity as identity: toward an understanding of religion from a social identity perspective. Person. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 14, 60–71. doi: 10.1177/1088868309349693

Appendix

SPORTS

Sports Spectator Identification Scale (Wann and Branscombe's, 1993); 7-point, Semantic Differential (Not at all/Very much so)

1. How important to YOU is it that your favorite sports team wins?

2. How strongly do YOU see YOURSELF as a fan of your favorite sports team?

3. How strongly do your FRIENDS see YOU as a fan of your favorite sports team?

4. During the season, how closely do you follow your favorite sports team via media?

5. How important is being a fan of your favorite sports team to YOU?

6. How much do YOU dislike your favorite sports team's greatest rivals?

7. How often do YOU display your favorite sports team's name or insignia at your place of work, where you live, or on your clothing?

POLITICS

Political partisanship scale (Bankert et al., 2017); 7-point Likert

1. When I speak about this party, I usually say “we” instead of “they.”

2. I am interested in what other people think about this party.

3. When people criticize this party, it feels like a personal insult.

4. I have a lot in common with other supporters of this party.

5. If this party does badly in opinion polls, my day is ruined.

6. When I meet someone who supports this party, I feel connected with this person.

7. When I speak about this party, I refer to them as “my party.”

8. When people praise this party, it makes me feel good.

RELIGION

Centrality of Religiosity Scale (Huber and Huber, 2012); 7-point Likert

1. I believe that God or something divine exists.

2. I regularly take part in religious services.

3. I believe in an afterlife—e.g., immortality of the soul, resurrection of the dead or reincarnation.

4. It is important to take part in religious services.

5. It is probable that a higher power exists.

6. It is important that I be connected to a religious community.

STIMULUS

Picture whoever you view as the leader of your preferred [sports team/political party/religious organization]. They have been found to be guilty of [assault and battery/sex with a minor/stealing money from your preferred organization]. Now indicate your agreement with the following statements; 7-point Likert

1. I would stay loyal to my preferred [sports team/political party/religious organization].

2. *My positive feelings about my preferred [sports team/political party/religious organization] would lessen.*

3. I would still recommend my preferred [sports team/political party/religious organization] as good for others to support.

4. In time, I could forgive the leader of my preferred [sports team/political party/religious organization].

5. I would be more likely to forgive the leader of my preferred [sports team/political party/religious organization] than an average person.

*dropped for reliability.

Keywords: loyalty, sports, politics, religion, transgressions

Citation: Towery NA, Billings AC, Zengaro EC and Sadri SR (2023) Loyalty as permission to forgive: sport, political, and religious identification as predictors of transgression diminishment. Front. Commun. 8:1152519. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2023.1152519

Received: 27 January 2023; Accepted: 25 July 2023;

Published: 10 August 2023.

Edited by:

Joseph Faina, Los Angeles Valley College, United StatesReviewed by:

Kinga Kaleta, Jan Kochanowski University, PolandCole FRanklin, Louisiana State University of Alexandria, United States

Copyright © 2023 Towery, Billings, Zengaro and Sadri. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Andrew C. Billings, YWNiaWxsaW5nc0B1YS5lZHU=

Nathan A. Towery1

Nathan A. Towery1 Andrew C. Billings

Andrew C. Billings Elisabetta C. Zengaro

Elisabetta C. Zengaro