- 1School of Multimedia Technology and Communication, Universiti Utara Malaysia, Sintok, Kedah, Malaysia

- 2Othman Yeop Abdullah Graduate School of Business (OYAGSB), Universiti Utara Malaysia, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

- 3Department of Mass Communication, National University of Sciences and Technology (NUST), Islamabad, Pakistan

- 4Faculty of Applied and Human Sciences, Universiti Malaysia Perlis (UniMAP), Kangar, Perlis, Malaysia

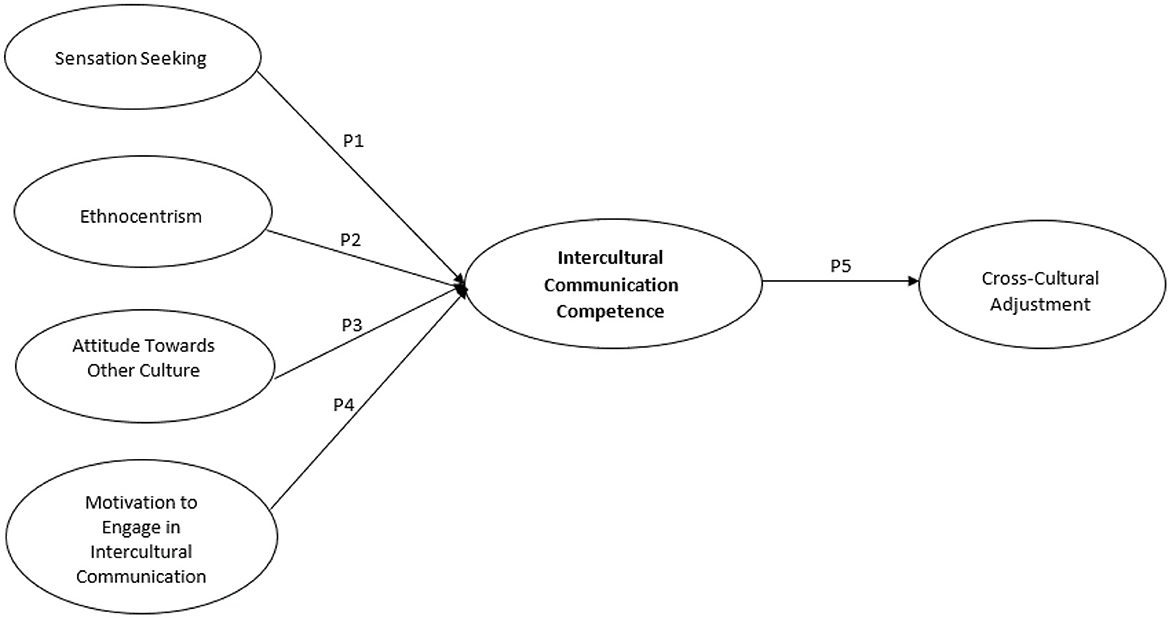

Intercultural communication competence (ICC) has been identified as an important area of study, given today's increasing diversity in many societies. While it is acknowledged that there are already ICC studies and models available in the literature, most, if not all, address the ICC of expatriates or sojourners. Studies, as well as models that specifically address the ICC of migrant workers, are scanty. Hence, this study intends to highlight the crucial need for a better understanding of the issues related to ICC by providing a comprehensive and critical review of studies on ICC. This enables the proposition of a conceptual framework for ICC that is specific to migrant workers working in Malaysia due to their crucial importance to the country's economy. The proposed conceptual framework considers include sensation seeking, ethnocentrism, attitude toward other cultures, and motivation to engage in intercultural communication as the antecedents of ICC. Meanwhile, cross-cultural adjustment is proposed as a consequence of ICC. The proposed conceptual model would be useful in bridging the budding literature of ICC by highlighting the skills needed by migrant workers, which will, consequently, facilitate their adjustment and enable them to perform their work successfully in Malaysian culture.

1. Introduction

The rise of migrating populations, workplace diversity, and economic dependencies has created an urgent need for a networked society. Nowhere is this need felt more keenly than in today's unprecedented times of a global pandemic, which has prompted people to seek new ways to “live together” and a sense of interconnectedness (Deardorff, 2015, 2020). This realization has brought to the forefront the heightened necessity to understand what it means to communicate effectively between and across cultures. On the individual level, a rising number of people have their identities and beliefs molded through their interactions with various people. At the societal level, global mobility has created an environment where people must seek an understanding of “good” communication with those who do not share similar beliefs and values. As such, cultivating a sense of “oneness” is vital, in which people must learn to have positive relations with those who speak different languages and possess distinct values. This is a clear reminder that developing effective cross-cultural relationships requires intercultural competency, which is no longer a choice. In a review of her 10-year scholarship in intercultural competence, Arasaratnam (2015) remarked that “competence” needs to be the subject of continual study.

Considering this, it is necessary that further investigation be conducted to understand ICC and issues related to it among migrant workers, especially in Malaysia, where the culture at large comprises various ethnic and racial components (Bakar et al., 2016; Raza et al., 2018). A literature review suggests three main concerns related to migrant workers' ICC in Malaysia. First, the issue of mismatching expectations from people of the host culture toward migrant workers. For example, while migrant workers are useful for Malaysia to enhance its economic growth, their presence in a culture that is different from others can present various societal challenges. According to World Bank data from Malaysia, for instance, a 10% net increase in manual or “low-skilled” migrant workers may increase Malaysia's GDP by up to 1.1% (World Bank, 2015). Since migrant workers bring their own cultural values, norms, and beliefs to Malaysian society, creating their own unique community, their existence has triggered unease among Malaysians (Lasimbang et al., 2016; Aziz et al., 2017; Merall, 2018; Mohamad et al., 2018). Lustig and Koester (2010) have pointed out that the tensions inherent in creating intercultural communities are clear, as it is difficult for culturally different groups to live, work, play, and communicate harmoniously. The consequences of failing to create societal harmony among culturally diverse people can be disastrous for the nation. As such, there arises the need for “the other” (i.e., migrant workers) to learn to coexist harmoniously with fellow nationals.

Moreover, according to data from the Malaysian government, there are at least two million migrant workers, mostly from Indonesia and Bangladesh, making up 15% of the total employed population (Ministry of Home Affairs, 2019; Department of Statistics Malaysia Official Portal, 2020). This figure includes both low-skilled and high-skilled workers from various countries who have legally entered Malaysia to work. The increase in the number of migrant workers contributes to a number of problems, such as inappropriate behaviors in local society (Sakolnakorn, 2019), poor language and communication skills (Lasimbang et al., 2016), and negative societal perceptions (Merall, 2018). In light of this, it is essential to evaluate ICC from the viewpoint of migrants to help them reduce cultural differences and engage meaningfully in society. Migrants would inevitably carry their own cultural values, norms, and beliefs, leading to their own sub-community within culturally diverse cultures. Despite such societal issues, the number of migrant workers in the country is continuously rising in a variety of industries, including oil and gas, manufacturing, and engineering. This is evident as the Economic Outlook Report by the Malaysian Ministry of Finance (2021) indicated that Malaysia hosted ~1.9–2 million migrant workers from 2016 to 2019. Hence, the incoming migrant workers seem to be not only desirable but pertinent to the long-term economic goals of the country. Increased immigration and diversity can be important social assets for a nation. Successful immigrant communities have the potential to develop new types of social harmony over the medium to long term and dampen the negative consequences of diversity. Therefore, migrant workers must mitigate differences to coexist harmoniously with the local culture and participate meaningfully in the host's larger society. This pertinence thus requires a conceptual framework for ICC in the migrant worker context.

Finally, given its economic development necessity, the International Organization for Migration (International Organization for Migration-Malaysia, 2021) reported that the Malaysian government has officially estimated that the country is home to ~1.4–2 million documented migrants, with unofficial estimates suggesting an additional 1.2 to 3.5 million migrants (as reported by the World Bank). As a result, Malaysia stands as one of the largest migrant-receiving countries in Southeast Asia. Given that Malaysia has 16.07 million people employed overall as of July 2021, a 15% cap would, over time, keep the number of foreign employees to a maximum of 2.4 million. By the end of 2020, there were 1.48 million registered foreign employees in Malaysia, or 9.9% of the entire workforce (Ministry of Economic Affair, 2019).

Based on the three main concerns, it is evident that the presence of migrant workers has had consequences for Malaysian culture. Nevertheless, not much has been known about this group due to the lack of ICC research that specifically targets migrant workers in Malaysia. Past studies have provided descriptions of skills, traits, and behaviors that contribute to our understanding of ICC. However, much of the existing literature is largely based on examining ICC among expatriates (mainly business people and diplomats) or sojourners (mainly international students/academic migrants) (Spitzberg, 2000, 2012; Lustig and Koester, 2010; Deardorff, 2011). As such, there is an urgent need for researchers to examine the ICC of migrant workers, particularly in Malaysia.

Liu et al. (2019) defined migrant workers as people who migrate from one country to another to be employed, and in the host country, they are normally known as foreign workers. The arrival of migrant workers in a host cultural environment changes its cultural makeup. It is nearly inconceivable to imagine how a host society would not change once migrants have been integrated. There are a number of push-and-pull variables that contribute to the entry of migrant workers into a host nation. Push factors compel migrants to leave their home countries and reside in a new country, such as low productivity, high unemployment, poor economic conditions, migrants' motivation to earn more money, and better economic opportunities. Moreover, pull factors are elements that attract immigrants to a nation, such as chances for better employment, greater salaries, and better working conditions (Navamukundan, 2002; Djafar and Hisyam, 2012). While it is acknowledged that push and pull factors are the nature of economic migrants, we must study the impact of this migration on the host society.

Deriving from the above arguments, this study will critically review the existing literature on ICC for the future research agenda and propose a conceptual framework for a better understanding of ICC among migrant workers in Malaysia. In doing so, the article is organized into various sections, beginning with defining the ICC and reconciling the concept. This is followed by discussions of the antecedents of ICC and proposed relationships between variables. Finally, this article presents a conceptual model that explains the relationships between the antecedents and consequences of ICC (see Figure 1).

1.1. Defining intercultural communication competence

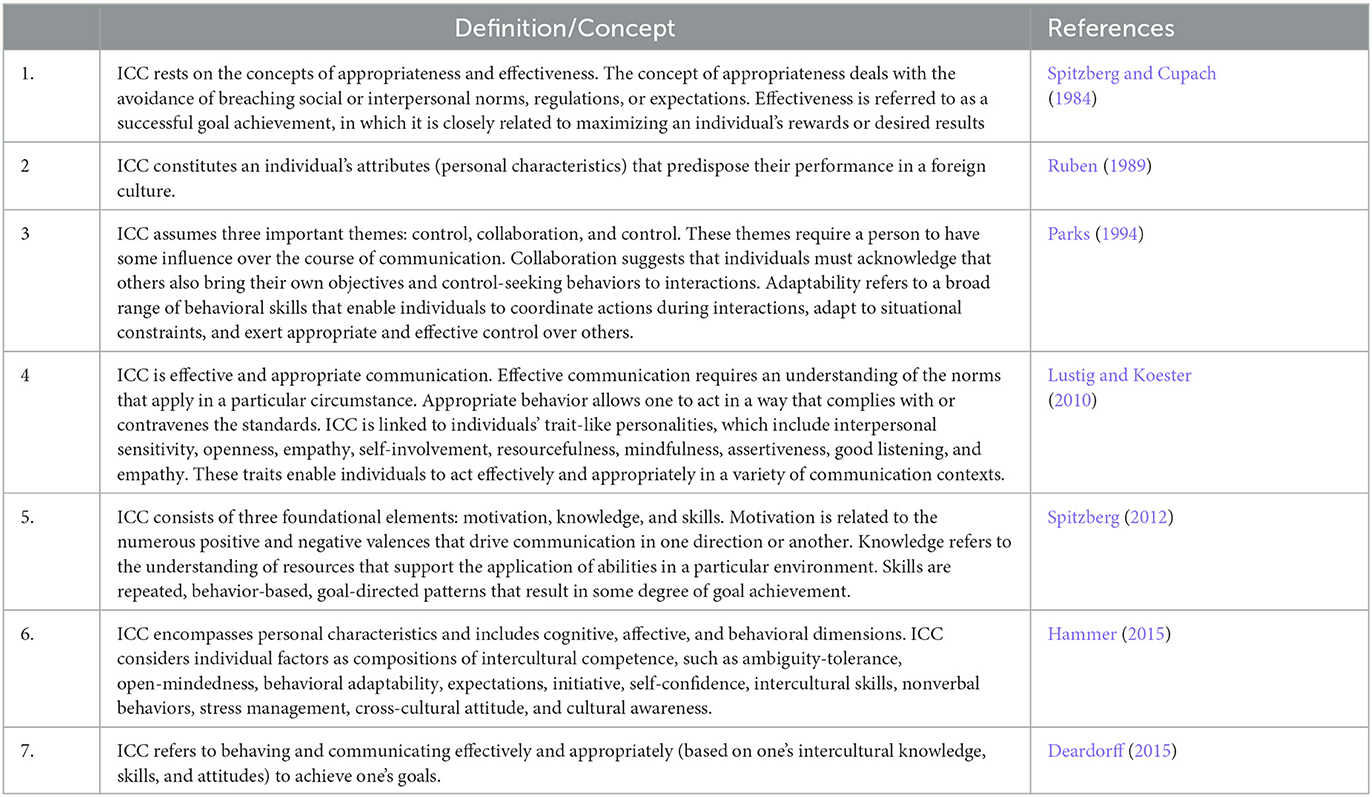

The term “intercultural communication competence” has diverse definitions and nomenclatures (see Bennett, 2009). The core conception of ICC rests on the concepts of appropriateness and effectiveness. The concept of appropriateness deals with the avoidance of breaching social or interpersonal norms, regulations, or expectations, and effectiveness is strongly tied to the satisfaction of achieving desired results (Spitzberg and Cupach, 1984, 1989). According to Lustig and Koester (2010), effective communication requires an understanding of the norms that apply in a particular circumstance. Knowing what behavior is appropriate in a given situation and what is inappropriate allows one to act in a way that complies with or contravenes the standards.

In addition to the concepts of appropriateness and effectiveness, Spitzberg and Changnon's (2009) analysis of more than 20 intercultural competence models found that motivation, knowledge, and skills that make up intercultural competence are the most frequently used elements. However, scholars do not always label their models precisely with these terms. According to Spitzberg (2012), motivation is related to the numerous positive and negative valences that drive communication in one direction or another. Knowledge refers to the understanding of resources that support the application of abilities in a particular environment. This includes the capacity to gather information, whether through inquiries, observations, cognitive modeling, or imaginative introspection. Skills are repeated, behavior-based, goal-directed patterns that result in some degree of goal achievement. Given the key elements of intercultural competence, it is hypothesized that the greater one's knowledge, motivation, and skillful behavior, the more likely one is to be considered competent in intercultural communication (Deardorff, 2006; Byram and Golubeva, 2020).

Early attempts to measure ICC were mostly based on an individual's attributes (personal characteristics) that predispose their performance in a foreign culture (Ruben, 1989). Such attention can be attributed to the early history of the intercultural communication field. Moon (1996) remarked that after World War II, the United States attempted to invest and engage in foreign nations, and many people were dispatched abroad to carry out international missions. However, due to their inability to adapt to cultural differences, expatriates failed to complete their tasks and returned. Sojourners also struggle with issues including cross-cultural effectiveness, personal adjustment, and culture shock. Scientific interest in the concept of ICC was sparked by the necessity to prepare people to work effectively in a foreign environment. Ruben (1989) observed that early intercultural communication studies needed the views of ICC to achieve three objectives: to explain failures and anticipate success abroad, to establish methods for staff selection, and to evaluate sojourner training and preparation methodologies.

According to Spitzberg and Changnon (2009), competency is still heavily reliant on personality traits in the literature today and is virtually always measured as such. The trait-like approach, according to Lustig and Koester (2010), assumes that communicators can act appropriately in various communication contexts. To explain competence, trait orientation uses personality-based theory. Individuals that exhibit interpersonal sensitivity, openness, empathy, self-involvement, resourcefulness, and mindfulness are among the personality traits that are linked to competence. According to their trait orientation, people are competent because they are assertive, good listeners, and empathic. In the following years, research on the topic proliferated, focused on a variety of contexts (language education, study abroad, international student roommates, overseas development projects, business, and so on) from a variety of theoretical foundations, and employing various methodologies, with a range of nomenclature, which includes, among others, competence, effectiveness, and appropriateness (Martin and Nakayama, 2013).

In terms of approach to intercultural competence, Hammer's (2015) review of intercultural competence research indicated that most, if not all, researchers focused their attention on personal characteristics. Such an approach has been used to define and theorize about intercultural competence. Accordingly, researchers examined various personal characteristics using the CAB (cognitive, affective, and behavioral) dimensions, which are essentially compositional. Given such a compositional approach, previous research was conducted to identify these behavioral dimensions of intercultural competence. This approach emphasizes individual factors as components of intercultural competence, including ambiguity-tolerance, open-mindedness, and behavioral adaptability. Citing further on his own study, Hammer offers several characteristics of intercultural competence, including expectations, initiative, self-confidence, intercultural skills, nonverbal behaviors, stress management, cross-cultural attitude, and cultural awareness. While this approach is widely used and is dominant, taking Spitzberg and Changnon's (2009) meta-analysis on components of intercultural competence, Hammer questioned the overlap and long list of factors for intercultural competence and proposed a developmental paradigm as an alternative approach. For example, Bennett's (1986) Developmental Model of Intercultural Sensitivity draws attention to how individuals experience cultural differences. This approach investigates how individuals progress from a low to a high degree of intercultural competence. In this regard, it visualizes how individuals move from a simple to a more complex understanding of intercultural competence.

The above definitions are certainly helpful for our understanding of intercultural competence. However, there is a caveat that many of the existing definitions of intercultural competence were mostly derived from Western cultural contexts (primarily US and European) (Deardorff, 2009). The definitions of intercultural competence tend to highlight the achievement of effective and appropriate interaction by an individual in intercultural situations and the knowledge, motivation, and skills required for the individual to be more competent (Deardorff, 2015). It is worth elucidating the source that shapes such a standpoint. Woelfel (1987) claimed that most Western communication theories' roots lie in Aristotle's philosophy. Aristotle assumed that there are a set of behaviors from which an individual person may choose in any situation, and choices are made based on the individual's beliefs and attitudes. As such, the primary goal of communication in the West is to provide self-realization and to achieve personal control (Cushman and Kincaid, 1987).

Additionally, Parks (1994) noted that control, collaboration, and adaptability are the themes inherent in the Western assumption of competency. The idea of control requires a person to have some influence over the course of communication. Collaboration suggests that individuals must acknowledge that others also bring their own objectives and control-seeking behaviors to interactions. Thus, competence takes place when people support one another in achieving personal and satisfying objectives. The term “adaptability” refers to behavioral flexibility, which calls for an individual to have a wide range of behavioral skills that allow them to coordinate actions during an interaction. As such, a person must be able to adjust their communication techniques to adapt to situational constraints and exert suitable and effective control over others. Please refer to Table 1 for a summary of multiple ICC-related concepts.

The literature contains a wide range of approaches, theoretical assumptions, and individual-level variables that may influence ICC directly or indirectly (see, Arasaratnam, 2007, 2016b). At this stage, it is critical to draw attention to the most common approaches used by researchers to address ICC. First, the culture-specific approach contains some culture-specific and biased variables in its development that limit its universal testing or application (Arasaratnam, 2007). Second, the general culture approach identified several variables that can directly or indirectly influence the ICC of people from various cultures.

The general cultural approach to ICC has emerged tremendously in the field of ICC, given its universal application. A notable contribution to the field can be observed in the study conducted by Arasaratnam and Doerfel (2005), where they identified and examined five key variables (empathy, attitude, motivation, listening, and experience) that have the potential to influence ICC. These variables were empirically validated in their subsequent work, leading to the development of the Integrated Model of Intercultural Communication Competence (IMICC) (Arasaratnam, 2006). This pioneering culture-general model established a cause-and-effect relationship among the identified variables and improved our understanding of ICC. Subsequently, several attempts have been made to refine and retest the IMICC model in various cultural contexts (Arasaratnam et al., 2010a; Arasaratnam and Banerjee, 2011). The most recent version contains four antecedents of ICC, such as sensation seeking, ethnocentrism, attitude toward other cultures (ATOCs), and motivation to engage in intercultural communication (MTEIIC) (Nadeem et al., 2020b). This current study has considered these variables as noteworthy antecedents of ICC, and they can be applied to any cultural setting due to their general cultural nature.

2. Antecedents of intercultural communication competence

Drawing from the IMICC model (Arasaratnam, 2006), this section discusses the empirically tested four antecedents of intercultural communication competence in previous research: sensation seeking, ethnocentrism, attitude toward other cultures, and motivation to interact with other cultures.

2.1. Sensation seeking

Sensation seeking is a personality attribute associated with a desire for adventure or thrills, a thirst for novelty, and risky health habits (Arasaratnam and Banerjee, 2011). Sensation seeking is a personality variable whose foundations are deeply rooted in health- or risk-related behaviors. Typically, sensation seekers are observed pursuing it in social settings, such as attempting to interact with people from varied ethnic backgrounds (Morgan and Arasaratnam, 2003). Another study by Arasaratnam et al. (2010b) discovered a connection between sensation seeking and ICC. The concept of sensation seeking was incorporated into the IMCC, which provided important insights (Arasaratnam and Banerjee, 2011). The research found that sensation seekers indeed exhibit such pro-cultural attitudes and behaviors. A study further investigated this goal and discovered that sensation-seeking could negatively affect one's ICC. Based on existing literature on the relationship between sensation-seeking and intercultural competence, the following proposition is proposed:

Proposition 1: Sensation-seeking is associated with intercultural communication competence.

2.2. Ethnocentrism

Ethnocentrism is regularly observed as an important factor that may deter or enhance an individual's ICC. However, this factor is a variable that debilitates ICC (Arasaratnam, 2016a,b). Gudykunst and Kim (2003) noted that ethnocentrism leads us to judge any cultural practices outside our own as improper. Studies have demonstrated that it has a negative link with ICC and that the relationships between the other factors that affect ICC are also poor (Arasaratnam, 2016a; Kumari and Nirban, 2017). With this in mind, it can be understood that ethnocentrism is a major factor that limits a person's ability to interact with or develop friendships with people from multiple cultural backgrounds (Nadeem et al., 2020b). The perception of superiority of culture, tradition, etc., strongly influences the individual and results in a reverse or negative impact on the ICC of individuals (Arasaratnam and Banerjee, 2011). Recent studies have also supported a negative relationship between these two variables (Campbell, 2016; Nameni, 2020). The addition of ethnocentrism to the IMICC created an adverse impact on other variables that were having a positive impact on the ICC (Arasaratnam and Banerjee, 2011). Taking this into account, the above discussion proposes the following proposition.

Proposition 2: Ethnocentrism is negatively associated with intercultural communication competence.

2.3. Attitude toward other cultures

In the initial stage of Arasaratnam's model of ICC, ATOC is a variable that describes a person's openness to encountering different cultures in addition to worldviews (Arasaratnam and Doerfel, 2005). ATOC is defined by Arasaratnam (2006) as “good attitudes toward individuals from other cultures that are not ethnocentric” (p. 5). Later, this phrase is modified to refer to a welcoming attitude toward other cultures (ATOC). ATOC is described as “a pleasant, non-ethnocentric attitude toward persons who are culturally different from oneself” by Arasaratnam et al. (2010a, p. 108). Manathunga (2009) asserted that intercultural competence and abilities are essential for working effectively with people from other cultures. More importantly, having a good ATOC will improve communication between parties. According to Arasaratnam (2006), these characteristics were positively correlated with ICC. Another study by Arasaratnam et al. (2010b) discovered that ATOC was both a predictor of ICC and had a direct relationship with it. In a similar vein, Arasaratnam and Banerjee (2011) examined the connection between various predictors that affect ICC. The study's findings demonstrated a significant association between ATOC and ICC. In the new comprehensive model of ICC, Arasaratnam et al. (2010a) proposed a new path that showed ATOC and ICC also have a clear connection.

Additionally, they connected positive ATOC to having good listening skills. Another study by Arasaratnam et al. (2010b), in the context of other studies about the improvement of IMICC, discovered that ATOC could directly affect an individual's ICC. Similarly, Arasaratnam and Banerjee (2011) examined the relationship between several factors that relate to ICC. The study's findings demonstrated a close connection between ATOC and ICC. This leads to the following proposition:

Proposition 3: Attitude toward other cultures is positively associated with intercultural communication competence.

2.4. Motivation to engage in intercultural communication

MTEIIC refers to the desire to engage in intercultural communication to learn about and comprehend various cultures (Arasaratnam, 2004a,b). Kim (1991) referred to MTEIIC as the affective component of competence that conveys readiness to deal with cross-cultural difficulties (p. 269). MTEIIC is a collection of emotions, motivations, needs, and drives that are connected to anticipating or engaging in cross-cultural communication (Deardorff, 2004). It can serve as the foundation for cross-cultural contact (Martin and Nakayama, 2010). Arasaratnam (2006) suggests MTEIIC is the urge to mingle across cultures to comprehend and learn about others' cultures. The testing of a culture-general model of ICC in a study by Arasaratnam (2006) revealed a substantial correlation between MTEIIC and ICC. Arasaratnam (2009) created a new ICC instrument and discovered a beneficial connection between ICC and MTEIIC. In her later study, when she established the IMICC, it was discovered that a person's MTEIIC positively affects ICC (see Arasaratnam et al., 2010a). Further investigating the relationship between MTEIIC and ICC, Arasaratnam and Banerjee (2011) discovered a substantial positive relationship between both variables. However, Nadeem et al. (2020a) most recent study did not discover a connection between these two characteristics. They demonstrated that Malaysian international students are not sufficiently driven to strike up a conversation with people from different cultures for a variety of reasons, including, among others, a limited incentive to interact due to limited language ability (Nadeem et al., 2020a). However, a study on migrant workers showed the crucial relevance of foreign language skills in enhancing their quality and intercultural competency (Indrayani et al., 2015; Dewi and Sudagung, 2017). In view of such findings, this study proposes a relationship between the variables.

Proposition 4. Motivation to engage in intercultural communication is positively associated with intercultural communication competence.

3. Consequences of intercultural communication competence

The following section discusses the relationship between ICC and cross-cultural adjustment.

3.1. Cross-cultural adjustment

Black et al. (1992) contend that culture is not just about artifacts or a person's values and beliefs. Rather, it is a “commonly held set of presumptions that consistently influence objects, especially behavior.” According to Black et al. (1991), cross-cultural adjustment is the extent to which migrants or sojourners feel psychologically at ease and are conversant with the many aspects of a foreign culture. As a result of the adjustment process, sojourners or migrants become more at ease with the new culture and adapt to their surroundings and the environment itself by reducing uncertainties and changes. Studies on expatriation have confirmed how the new cultural context impacts the adjustment, attitudes, and behaviors of sojourners, especially expatriates (Yavas and Bodur, 1999; see, for example, Selmer, 2001). According to early research by Church (1982), culturally acclimated sojourners are more responsive to the new setting, are able to change their behavior and norms accordingly and incorporate the new behaviors learned from foreign cultures.

Research on cross-cultural adjustment has identified various variables that affect adjustment to a new cultural environment. For instance, Halim et al.'s (2018) study found that while openness is linked to personal adjustment among expatriates, it is not significantly associated with their cross-cultural adjustments. Social initiative and cultural empathy are unrelated to any aspect of adjustment, including personal and professional adjustment. This is also in line with the assertion that sojourners who can adapt to a new cultural setting are found to be more receptive to it and are able to successfully modify their behavior, norms, and regulations in the new setting (Church, 1982; Halim et al., 2018). According to the SLT (Bandura, 1977), people learn by observation and imitation of the behaviors of others, which are influenced by external or internal incentives like self-worth, satisfaction, and success. Halim et al. (2018) study indicated that the expatriates in this study experiences may have influenced their expectations and helped them better understand Malaysian culture. Additionally, the multiracial culture of Malaysia in general and its distinctive offerings may have helped the sojourners adjust.

According to Black et al. (1992), the degree of discomfort that sojourners experience when interacting with members of the host culture is a key factor in cross-cultural adjustment. Sojourners with strong relational and interpersonal communication abilities will have less trouble interacting with citizens of the host country (Mendenhall and Oddou, 1985).

Another study indicates the relationship between intercultural competence and adjustment. For example, Kural (2020) studied the long-term contribution of ICC development to adjustment for study abroad students. Gita (2018) studied college students' intercultural competence and found that their ICC has increased their level of adjustment in their study abroad program. Jurásek and Wawrosz (2021) indicate that intercultural competence enhances the adjustment of a foreigner. They further posit that foreigners who have spent time abroad, know the host country's language, have language skills, and have frequent contact with the host member will adjust more easily to the new country. Given the discussions above, we propose that:

Proposition 5: Cross-cultural adjustment is positively associated with intercultural communication competence.

Given our proposed conceptual model of ICC, several research areas can be considered for further study. Future researchers are recommended to conduct empirical research that investigates the relationship between sensation seeking, ethnocentrism, attitude toward other cultures, motivation to engage in intercultural communication, ICC, and the relationship between ICC and cross-cultural adjustment among migrant workers. Such findings would be useful to validate the proposed conceptual model of ICC. Additionally, future researchers can delve into a more comprehensive understanding of ICC through qualitative research. For instance, it would be intriguing to explore how both migrant workers and locals perceive language and cultural experiences when navigating their interactions. Such an inquiry can provide valuable insights into the characteristics of intercultural competence, including behaviors related to cultural sensitivity, effective and appropriate communication, and the use of polite language.

4. Conclusion

The conceptual model presented above is proposed based on a review of the existing literature on ICC, migration, international human resource management, and cultural adjustment. As discussed in the literature, ICC and cultural adjustment are crucial in the processes of migration, expatriation, and sojournment. The approach taken in the study is slightly different than previous studies on migration and ICC as it discusses the comprehensive review of ICC and its antecedents and leads to the development of a conceptual model that explains the relationships between the variables, namely sensation seeking, ethnocentrism, attitude toward other cultures, and motivation to engage in intercultural communication. Moreover, the study also discusses the role of the ICC during the migration process. As ICC is not well researched in the Malaysian context, this research aims to draw the attention of relevant authorities that deal with migrant workers. The challenge for further research lies in the determination of ICC on two fundamental levels: First, as an academic discipline that integrates different fields of knowledge and is constrained by theoretical and methodological concerns. Second, as a community of practice where people and groups from a particular culture share common objectives and passions related to ICC and cross-cultural adaptation.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Funding

This research was supported by the Ministry of Higher Education (MoHE) of Malaysia through the Fundamental Research Grant Scheme (FRGS/1/2020/SS0/UUM/02/2).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcomm.2023.1147707/full#supplementary-material

References

Arasaratnam, L. A. (2004a). Intercultural Communication Competence: Development and Empirical Validation of a New Model. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the International Communication Association, New Orleans Sheraton, New Orleans, LA.

Arasaratnam, L. A. (2004b). Sensation seeking as a predictor of social initiative in intercultural interactions. J. Intercult. Commun. Res. 33, 215–222.

Arasaratnam, L. A. (2006). Further testing of a new model of intercultural communication competence. Commun. Res. Rep. 23, 93–99. doi: 10.1080/08824090600668923

Arasaratnam, L. A. (2007). Empirical research in intercultural communication competence: A review and recommendation. Austral. J. Commun. 34, 105–117.

Arasaratnam, L. A. (2009). The development of a new instrument of intercultural communication competence. J. Intercult. Commun. 20, 2–22.

Arasaratnam, L. A. (2015). Intercultural competence: Looking back and looking ahead. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 48, 12–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2015.03.004

Arasaratnam, L. A. (2016a). An exploration of the relationship between intercultural communication competence and bilingualism. Commun. Res. Rep. 33, 231–238. doi: 10.1080/08824096.2016.1186628

Arasaratnam, L. A. (2016b). “Intercultural competence,” in Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Communication (USA: Oxford University Press), pp. 01–23.

Arasaratnam, L. A., and Banerjee, S. C. (2011). Sensation seeking and intercultural communication competence: a model test. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 35, 226–233. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2010.07.003

Arasaratnam, L. A., Banerjee, S. C., and Dembek, K. (2010a). The integrated model of intercultural communication competence (IMICC): Model test. Austral. J. Commun. 37, 103–116. doi: 10.3316/ielapa.201102747

Arasaratnam, L. A., Banerjee, S. C., and Dembek, K. (2010b). Sensation seeking and the integrated model of intercultural communication competence. J. Intercult. Commun. Res. 39, 69–79. doi: 10.1080/17475759.2010.526312

Arasaratnam, L. A., and Doerfel, M. L. (2005). Intercultural communication competence: identifying key components from multicultural perspectives. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 29, 137–163. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2004.04.001

Aziz, M. A., Ayob, N. H., and Abdulsomad, K. (2017). Restructuring foreign worker policy and community transformation in Malaysia. Historic. Soc. Res. 42, 348–368. doi: 10.12759/hsr.42.2017.3.348-368

Bakar, H. A., Halim, H., Mustaffa, C. S., and Mohamad, B. (2016). Relationships differentiation: Cross-ethnic comparisons in the Malaysian workplace. J. Intercult. Commun. Res.45, 71–90. doi: 10.1080/17475759.2016.1140672

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychologic. Rev. 84, 191–215. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191

Bennett, J. M. (1986). “Towards ethnorelativism: a developmental model of intercultural sensitivity,” in Cross-Cultural Orientation: New Conceptualizations and Applications, ed R. M. Paige (New York: University Press of America), 27–70.

Bennett, J. M. (2009). “Cultivating intercultural competence.” in The SAGE Handbook of Intercultural Competence, ed D. K. Deardorff (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage).

Black, J. S., Gregersen, H. B., and Mendenhall, M. E. (1992). Global Assignments: Successfully Expatriating and Repatriating International Managers. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Black, J. S., Mendenhall, M. E., and Oddou, G. (1991). Toward a comprehensive model of international adjustment: an integration of multiple theoretical perspectives. Acad. Manage. Rev. 16, 291–317. doi: 10.2307/258863

Byram, M., and Golubeva, I. (2020). “Conceptualising intercultural (communicative) competence and intercultural citizenship,” in Routledge Handbook of Language and Intercultural Communication. (London: Routledge). 70–85.

Campbell, N. (2016). Ethnocentrism and intercultural willingness to communicate: a study of New Zealand management students. J. Intercult. Commun. 40, 1–16.

Church, R. D. (1982). Sojourner adjustment. Psychologic. Bull. 91, 540–572. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.91.3.540

Cushman, D. P., and Kincaid, D. L. (1987). “Introduction and initial insights,” in Communication Theory: Eastern and Western Perspectives, ed D. L. Kincaid (Albany, NY: State University of New York), 1–10.

Deardorff, D. K. (2004). The identification and assessment of intercultural competence as a student outcome of international education at institutions of higher education in the United States [Doctoral dissertation, NC State University]. NC State University Libraries. Available online at: http://repository.lib.ncsu.edu/ir/bitstre (accessed May 26, 2023).

Deardorff, D. K. (2006). Identification and assessment of intercultural competence as a student outcome of internationalization. J. Stud. Int. Educ. 10, 241–266. doi: 10.1177/1028315306287002

Deardorff, D. K. (2009). “Synthesizing conceptualizations of intercultural competence,” in The SAGE Handbook of Intercultural Competence, ed D. K. Deardorff (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage), 264–269.

Deardorff, D. K. (2011). Assessing intercultural competence. New Direct. Inst. Res. 149, 65–79. doi: 10.1002/ir.381

Deardorff, D. K. (2015). Intercultural competence: mapping the future research agenda. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 48, 3–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2015.03.002

Deardorff, D. K. (2020). (Re)learning to live together in 2020. J. Int. Stud. 10, 15–18 doi: 10.32674/jis.v10i4.3169

Department of Statistics Malaysia Official Portal (2020). Labour Force Survey Report 2019. Putrajaya: Department of Statistics Malaysia.

Dewi, A. U., and Sudagung, A. D. (2017). Indonesia's migrant domestic workers within Asean community framework: a societal and economic security approach. Intermestic. J. Int. Stud. 2, 20–35. doi: 10.24198/intermestic.v2n1.3

Djafar, F., and Hisyam, H. (2012). Dynamics of push and pull factors of migrant workers in developing countries: the case of Indonesian workers in Malaysia. J. Econo. Behav. Stud. 4, 703–711. doi: 10.22610/jebs.v4i12.370

Gita, M. (2018). The impact of study abroad on college students' intercultural competence and personal development. Int. Res. Rev. 7, 18–41.

Gudykunst, W. B., and Kim, Y. Y. (2003). Communicating With Strangers: An Approach to Intercultural Communication (4th ed.). New York, NY: McGraw Hill.

Halim, H., Abu Bakar, H., and Mohamad, B. (2018). Measuring multicultural effectiveness among self-initiated academic expatriates in Malaysia. Malays. J. Commun. 34, 1–17. doi: 10.17576/JKMJC-2018-3402-01

Hammer, M. (2015). The developmental paradigm for intercultural competence research. Int. J. Intercult. 48, 12–15.

Indrayani, L. M., Dewi, A. U., and Qobulsyah, M. A. (2015). “Foreign language proficiency as intercultural competence enhancer for Indonesian migrant's worker: Study learned from the Phillipines,” in Intercutural Horizon, Intercultural Competence: Key to the New Multicultural Societies of the Globalized World, eds E. J. Nash, N. C. Brown, and L. Bracci (Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing).

International Organization for Migration-Malaysia. (2021). Infosheet 2021. Available online at: https://www.iom.int/sites/g/files/tmzbdl486/files/inline-files/infosheet-march-2022.pdf (accessed May 26, 2023).

Jurásek, M., and Wawrosz, P. (2021). Cultural intelligence and adjustment in the cultural diverse contexts: the role of satisfaction with life and intercultural competence. Econ. Sociol. 14, 204–227. doi: 10.14254/2071-789X.2021/14-4/12

Kim, Y. Y. (1991). “Intercultural communication competence: a systems theoretic view,” in Cross-Cultural Interpersonal Communication, eds S. Ting-Toomey, and F. Korzenny (Newbury Park, CA: Sage), 259–275.

Kumari, P., and Nirban, V. S. (2017). “Identifying dimensions and competencies for intercultural communication: a literature review. evidence based management,” in 2nd International Conference on Evidence Based Management 2017 (ICEBM'2017), 173–177.

Kural, F. (2020). Long term effects of intercultural competence development training for study-abroad adjustment and global communication. J. Lang. Linguistic Stud. 16, 948–958. doi: 10.17263/jlls.759348

Lasimbang, H. B., Tong, W. T., and Low, W. Y. (2016). Migrant workers in Sabah, East Malaysia: The importance of legislation and policy to uphold equity on sexual and reproductive health and rights. Best Pract. Res. Clinic. Obstetr. Gynaecol. 100, 113–123. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2015.08.015

Liu, S., Volcic, Z., and Gallois, C. (2019). Introducing Intercultural Communication: Global Cultures and Contexts (3rd ed.). London: SAGE.

Lustig, M. W., and Koester, J. (2010). Intercultural Competence: Interpersonal Communication Across Cultures (6th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson.

Manathunga, C. (2009). Research as an intercultural “contact zone.” Discour. Stud. Cult. Politic. Educ. 30, 165–177. doi: 10.1080/01596300902809161

Martin, J. N., and Nakayama, T. K. (2010). ≪Intercultural communication and dialectics revisited,” in The Handbook of Critical Intercultural Communication, eds R.T., Halualani and T. K. Nakayama (UK: Wiley-Blackwell), 59–83.

Martin, J. N., and Nakayama, T. K. (2013). Intercultural Communication in Contexts (6th ed.). Avenue of the Americas, NY: McGraw Hill.

Mendenhall, M., and Oddou, G. (1985). The dimensions of expatriate acculturation: a review. Acad. Manag. Rev. 10, 39–47. doi: 10.5465/amr.1985.4277340

Merall, E. T. (2018). Immigration policy recommendations for the Malaysian government: improving the treatment of migrant workers. Malays. J. Soc. Sci. Hum. 3, 1–5.

Ministry of Economic Affair (2019). Twelfth Malaysia Plan, 2021-2025 (12MP). A prosperous, inclusive, sustainable Malaysia. Available online at: https://rmke12.epu.gov.my/en (accessed May 26, 2023).

Ministry of Home Affairs (2019). Statistik pekerja asing mengikut warganegara dan sector sehingga 30 Jun 2019. Putrajaya: Ministry of Home Affairs

Mohamad, B., Nguyen, B., Melewar, T. C., and Gambetti, R. (2018). Antecedents and consequences of corporate communication management (CCM): an agenda for future research. Bottom Line 31, 56–75. doi: 10.1108/BL-09-2017-0028

Moon, D. G. (1996). “Concepts of “culture”: Implications for intercultural communication research,” in The Global Intercultural Communication Reader, eds M. K. Asante, Y. Miike and J. Yin (New York, NY: Routledge), 11–26.

Morgan, S., and Arasaratnam, L. (2003). Intercultural friendships as social excitation: sensation seeking as a predictor of intercultural friendship seeking behavior. J. Intercult. Commun. Res. 32, 175–186

Nadeem, M. U., Mohammed, R., and Dalib, S. (2020a). Influence of sensation seeking on intercultural communication competence of international students in a Malaysian university: attitude as a mediator. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 74, 30–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2019.10.006

Nadeem, M. U., Mohammed, R., and Dalib, S. (2020b). Retesting integrated model of intercultural communication competence (IMICC) on international students from the Asian context of Malaysia. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 74, 17–29. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2019.10.005

Nameni, A. (2020). Research into ethnocentrism and intercultural willingness to communicate of Iraqi and Iranian medical students in Iran. J. Intercult. Commun. Res. 49, 61–85. doi: 10.1080/17475759.2019.1708430

Navamukundan, A. (2002). Labour Migration in Malaysia-trade union views. Migrant Work. Labour Educ. 4, 110–115.

Parks, M. R. (1994). “Communication competence and interpersonal control,” in Handbook of Interpersonal Communication, eds M. L. Knapp and G. R. Miller (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage), 589–618.

Raza, S. H., Bakar, H. A., and Mohamad, B. (2018). Advertising appeals and Malaysian culture norms. J. Asian Pacific Commun. 28, 61–82. doi: 10.1075/japc.00004.raz

Ruben, B. D. (1989). The study of cross-cultural competence: traditions and contemporary issues. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 13, 229–240. doi: 10.1016/0147-1767(89)90011-4

Sakolnakorn, T. P. N. (2019). Problems, obstacles, challenges, and government policy guidelines for Thai migrant workers in Singapore and Malaysia. Kasetsart J. Soc. Sci. 40, 98–104. doi: 10.34044/j.kjss.2019.40.1.07

Selmer, J. (2001). Adjustment of Western European vs. North American expatriate managers in China. Personn. Rev. 30, 6–21. doi: 10.1108/00483480110380118

Spitzberg, B. H. (2000). “A model of intercultural communication competence,” in Intercultural Communication: A Reader, eds L. A. Samovar and R. E. Porter (Belmont, CA: Wadsworth), 375–387.

Spitzberg, B. H. (2012). “Axioms for a theory of ICC,” in Intercultural Communication: A Reader, eds E. R. McDaniel, R. E. Porter and L. A. Samovar (Boston, MA: Wadsworth), 424–435.

Spitzberg, B. H., and Changnon, G. (2009). “Conceptualizing intercultural competence,” in The SAGE Handbook of Intercultural Competence, eds D. K. Deardorff (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage), 2–52.

Spitzberg, B. H., and Cupach, W. R. (1984). Interpersonal Communication Competence. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Spitzberg, B. H., and Cupach, W. R. (1989). Handbook of Interpersonal Competence Research. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag.

Woelfel, J. (1987). “Development of the western model: toward a reconciliation of Eastern and Western perspectives,” in Communication Theory: Eastern and Western Perspectives, ed D. L. Kincaid (Albany, NY: State University of New York).

Keywords: communication, intercultural communication competence, cross-cultural adjustment, sensation seeking, ethnocentrism attitude towards other culture, motivation to engage in intercultural communication, migrant workers

Citation: Dalib S, Mohamad B, Nadeem MU, Halim H and Ramlan SN (2023) Intercultural communication competence among migrant workers in Malaysia: a critical review and an agenda for future research. Front. Commun. 8:1147707. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2023.1147707

Received: 19 January 2023; Accepted: 12 June 2023;

Published: 06 July 2023.

Edited by:

Fauziah Sh. Ahmad, University of Technology Malaysia, MalaysiaReviewed by:

Basrowi Basrowi, Bina Bangsa University, IndonesiaMazuwin Haja Maideen, University of Technology Malaysia, Malaysia

Farah Akmar Anor Salim, University of Technology Malaysia, Malaysia

Copyright © 2023 Dalib, Mohamad, Nadeem, Halim and Ramlan. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Bahtiar Mohamad, bWJhaHRpYXJAdXVtLmVkdS5teQ==

Syarizan Dalib

Syarizan Dalib Bahtiar Mohamad

Bahtiar Mohamad Muhammad Umar Nadeem

Muhammad Umar Nadeem Haslina Halim

Haslina Halim Sayang Nurshahrizleen Ramlan4

Sayang Nurshahrizleen Ramlan4