- 1Department of Biological Sciences, Missouri University of Science and Technology, Rolla, MO, United States

- 2United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service, Rolla, MO, United States

- 3United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service, Halfway, OR, United States

As climates change, natural resource professionals are often working on the frontlines of intensifying environmental disasters, acting in both scientific and emergency response roles. One subset of this group, wildland firefighters often engage in multifaceted careers that incorporate elements of resource planning, conservation management, community disaster relief, and operational management. Despite these STEM roles and nearly half (48%) of them having earned at least a bachelor's degree, usually in a STEM field, wildland firefighters are almost exclusively lumped with emergency responders in the scientific literature. We surveyed 708 wildland firefighters with 9 open response questions as part of a larger survey asking about experiences and attitudes in the United States federal workplace. From their responses and voluntarily provided demographic data, we extracted information about response length, use of hedges, tag questions and imperatives, use of personal language, use of expletives and derogatory language, use of apologetic language, and the types of responses provided. We then analyzed whether certain demographic and socioeconomic factors were statistical predictors of language use in wildland firefighter survey responses with the goal of ultimately providing a framework for differentiating and identifying factors that may influence employee retention, attitudes, morale, and experiences among wildland firefighter sub-demographics. We found that different demographic groups varied in their responses to questions: Minority groups used fewer words and were more likely to relate personal experiences than majority groups.

Introduction

Natural resources managers are STEM professionals who work at the intersection of conservation science and environmental planning. In a rapidly changing world, environmental planning now must consider intensifying and more frequent natural disasters such as wildfires, floods, and hurricanes (Wotton et al., 2017). Wildland firefighting activities often draw from a wide pool of STEM-based disciplines, including fire ecology, fuels management, fire planning, and forestry to meet the suppression needs that are incurred annually, particularly in the western United States. These professionals are often not considered in studies of STEM populations due to the interdisciplinary and multifaceted nature of their work, despite being academically trained in environmental, biological, geology, natural resources, and other STEM disciplines; historically, wildland firefighters have been exclusively considered in emergency management literature, neglecting to account for the important scientific cultural, occupational, and interpersonal components that may influence the career environment.

Working environment, workplace stress, and workplace homogeneity has the potential to marginalize the voices and needs of minority groups, such as women, BIPOC (Black Indigenous and persons of color), and members of the LGBTQ+ community. Diversity in this context may influence the experiences of these individuals through a variety of mechanisms including prejudice, stereotyping, outgroup derogation, workplace harassment, marginalization, and others. Very limited research exists that contextualizes wildland firefighters but work on female firefighters in Canada shows that “othering” through discrimination and hostility played a key role in women's experiences in the career (Gouliquer et al., 2020). Likewise, few studies directly examine the ways in which these stressors may differentially impact minority and marginalized wildland firefighters. Those that do report trends in experience rather than context: A quantitative survey of wildland firefighter experiences observed significantly higher rates of reported injury in BIPOC wildland firefighters than white wildland firefighters (Wildland Fire Survey, 2022). Similarly, Loomis and Richardson (1998) found occupational fatality of Black workers was 1.3–1.5 times higher than that of white workers, and Pratt et al. (1992) found that Black women were more likely to be injured than white women while working in agriculture settings.

In other sectors of the workforce with similar workplace characteristics, researchers have found marginalization to be a key factor influencing minority experiences. A recent study at NASA found that stochastic team-based work environments (in contrast to stable unit-based work environments) resulted in increased marginalization of LGBTQ professionals: They report less inclusive and respectful attitudes from colleagues in these environments, and decreased opportunities for community-building (McDermott, 2019; Cech and Waidzunas, 2022). Many wildland firefighters currently work in teams that assemble seasonally and often need to rapidly restructure and reorganize during a wildfire based on complex and rapidly evolving conditions, thus creating an analogous situation to the NASA team-based environment. A non-fire study of Black women found that workplace marginalization resulted in increased stress-related illness, less interest in high quality performance, job attrition, and overall decreased job performance (McGee, 1999), and these effects are likely widespread across the workforce. Given the ways in which the workplace environment for wildland firefighters can marginalize its minority populations, finding methods to report their summative experiences and needs is important for retention, recruitment, and workplace safety.

Wildland firefighting is a natural resources career field that lacks diverse representation (Riley et al., 2020). Approximately 83.6% of wildland firefighters are white, 78.7% are male, and 93.5% identify as straight (Wildland Fire Survey, 2022). In the United States, the USDA Forest Service is the agency tasked with wildfire response and employs the highest number of wildland firefighters, generally divided among three job status types: permanent full-time, permanent seasonal, and temporary seasonal. Among permanent employees, retirement status is either “primary fire” or “secondary fire,” meaning the amount of additional government benefits you will receive based on your job description is either one of two levels (primary = highest, requires entry into the wildland fire workforce prior to age 37).

Wildland firefighters assemble into teams based on geography and qualifications and are self-led (based on a combination of training and experience. They often work extended hours (16-h days, 14 days in a row with a 2-day break) for extended periods (4–8 continuous months), then experience periods of no work during similar durations. The teams often both live and work together due to the remote nature of the work, thus forming close social bonds like those reported by military personnel during combat (Siebold, 2007). A recent study found that married wildland firefighters and those with families experience significant familial stress and strain related to their careers (Grassroots Wildland Firefighters, 2021). Recent studies of wildland firefighter mental health have documented that 20–55% of wildland firefighters are at elevated suicide risk (Stanley et al., 2018; O'Brien and Campbell, 2021). Further, hiring issues and stress-related injuries have already been observed in federal wildland firefighters: In 2022, the federal wildland firefighter workforce hiring campaign failed to fill over 1,000 positions in California, reducing the anticipated seasonal workforce by ~30% (Sacks, 2022).

Quantitative responses from a recent survey of wildland firefighters (Wildland Fire Survey, 2022) revealed very few gendered or other demographically divided experiences. However, previous studies have shown that female wildland firefighters have unique health risks (Jung et al., 2021), fitness scores (Sharkey, 2016), coping strategies (Eriksen, 2019), and workplace stressors (Mitchell, 2019). Further, recent publications have highlighted the need for inclusivity and increased diversity in the profession (Riley et al., 2020), and national news outlets have communicated the stories of women facing sexual assault, harassment, and subsequent retaliation as federal wildland firefighters (Baldwin and Carpeaux, 2018). In similarly isolated and extreme environments, McDermott et al. (2022) characterized the experiences of female STEM professionals who experienced hypermasculinity, sexual assault and harassment, and an inequitable and unsafe working environment, all factors contributing to increased attrition from the profession.

We hypothesized that open response questions may provide additional details that differentiate gendered and other demographically unique experiences that were missed in multiple choice or scalar questions. The specific objectives of this project were to analyze open responses for demographic differences that were unelucidated by quantitative analyses (Wildland Fire Survey, 2022) to help develop future surveys that are linguistically tailored to the demographics to which they are administered. Ultimately, this may allow us to form a better framework for assessing factors that differentially influence employee retention, attitudes, morale, and experience among wildland firefighters.

Materials and methods

In January 2022, a member of our team administered an extensive survey to federal wildland firefighters. The survey contained 123 questions with a range of response types, primarily Likert scales, yes/no choices, multiple choice, 2 short-answer, and 9 qualitative open-response long form questions. Questions addressed attitudes, experiences, and perceptions about recruitment, retention, training, infrastructure, leadership, safety, mental health, pay and benefits, morale and culture, and work-life balance. Participants could omit questions as they wished. The questionnaire was reviewed by three senior wildland firefighters prior to its distribution for clarity, ease of response, and breadth of coverage.

All respondents self-administered the survey questions voluntarily with no incentives after reading a brief statement about the purpose of the survey. No identifying information was provided. The survey was available on an anonymous Google form from 1 January through 1 March 2022. Survey participants were recruited via professional networks, internet outlets, social media, and e-mail. This survey was not sponsored by a university or organization at the time of its distribution and the University of Missouri System's Institutional Research Board deemed approval for analysis of previously collected data unnecessary. Full quantitative survey results are in review elsewhere and can also be found at www.wildlandfiresurvey.com.

Criteria for inclusion in the survey results were employment as a current or former federal wildland firefighter and completion of at least 70% of questions. For our study, we defined a wildland firefighter as a federal employee who is tasked with preventing, actively suppressing, or supporting the active suppression of fires occurring in natural or naturalized vegetation. Broadly, this includes operational wildland firefighters (e.g., engine crews, hand crews, hotshot crews, smokejumpers, rappelers), fire prevention, fuels management specialists, fire ecologists, fire planners, wildland fire dispatchers, fire cache managers, fire equipment operators, and fire aviation. Approximately 48% of our sample population had earned a bachelor's degree, 5.4% had earned a graduate degree, and 76.3% had some education post-high school (e.g., associate degree, technical school, some college). The majority of our respondents (73.8%) were USDA Forest Service employees at the time of the survey and listed under the job title “Forestry Technician” or “Senior Forestry Technician,” which made it impossible to distinguish among other identifying attributes of their jobs.

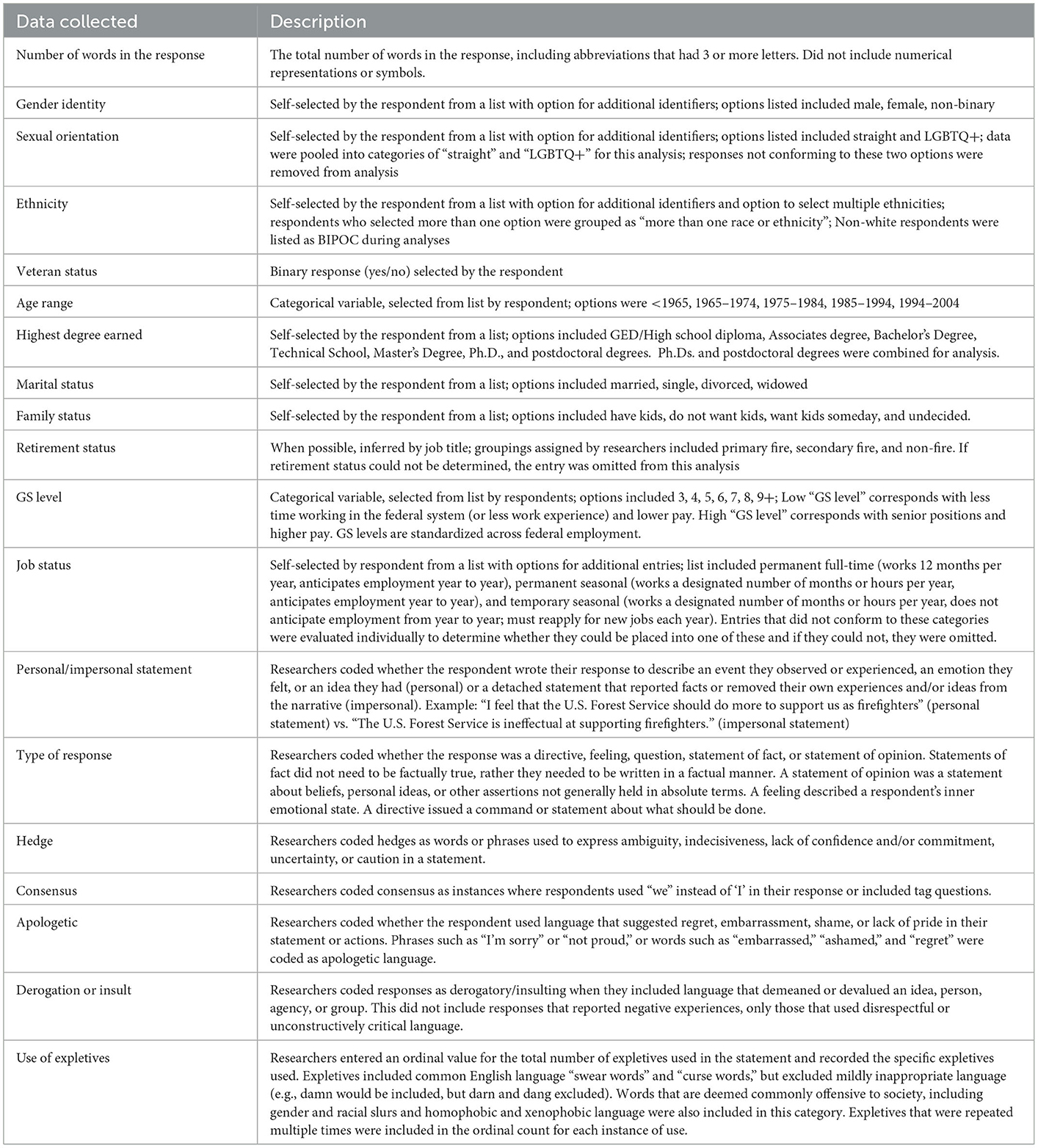

We extracted the 9 qualitative questions (Table 1) and their associated demographic data from the survey and used them to complete this analysis. For each response, we extracted the associated question; respondent gender identity, sexual orientation, ethnicity, veteran status, age range, highest degree earned, marital status, family status, retirement status, GS level, job status, and highest wildland firefighting training level attained (Table 2). We then manually analyzed the number of words in the response; whether the response was a personal or impersonal statement; the type of response; whether the respondent hedged (Fraser, 2010); whether consensus building, tag imperatives, or tag questions were employed (Arbini, 1969; Bradley, 2009); whether the respondent was apologetic (Holmes, 1989; Sugimoto, 1998; Schumann and Ross, 2010); whether the response contained a derogation or insult; and whether expletives were utilized (Staley, 1978; Hughes, 1992; De Klerk, 2009; Jacobi, 2014, Table 2). We selected these categories of analysis based on a search of literature that analyzed differences in speech and writing patterns among men and women. We then excluded categories that could only be detected vocally (e.g., fry and intonation). Table 2 summarizes the codebook used by the 4 coders to analyze responses. Intercoder reliability was assessed by a random quality assessment by senior author Verble at a rate of 10%. Responses that did not answer questions or responded with “I don't know” or “n/a” were excluded from further analysis. We used nested analyses of variance to examine relationships between demographic variables (nested within individual respondent) and response word count (alpha = 0.15). Student's t-tests were used to compare differences among means. We used Chi-square analyses to compare categorical variables with p < 0.15. Data were analyzed in Excel and JMP 16.0 (SAS, 2022).

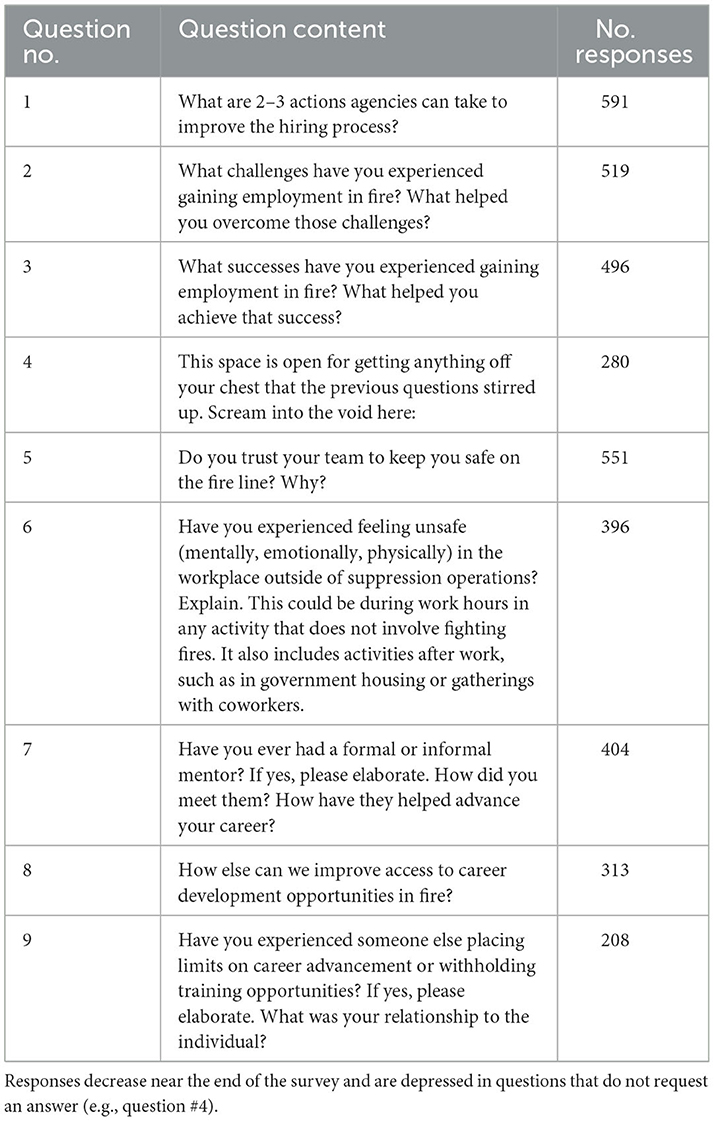

Table 1. Questions posed during the survey in the sequential order in which they were presented and the total number of individuals responding to each question.

Table 2. Comment attributes analyzed in this study and descriptions of how the attribute was defined by the researchers.

Results

We analyzed a total of 91,200 words across 3,758 responses from 708 individuals. On average, respondents completed 5.35 of the 9 questions asked, skewed toward the questions that were asked at the beginning of the survey (Table 1). The demography of our respondent class was similar to previously documented demographics of wildland firefighter populations in Canada (Grahame Gordon Wildfire Management Services, 2014).

Response length

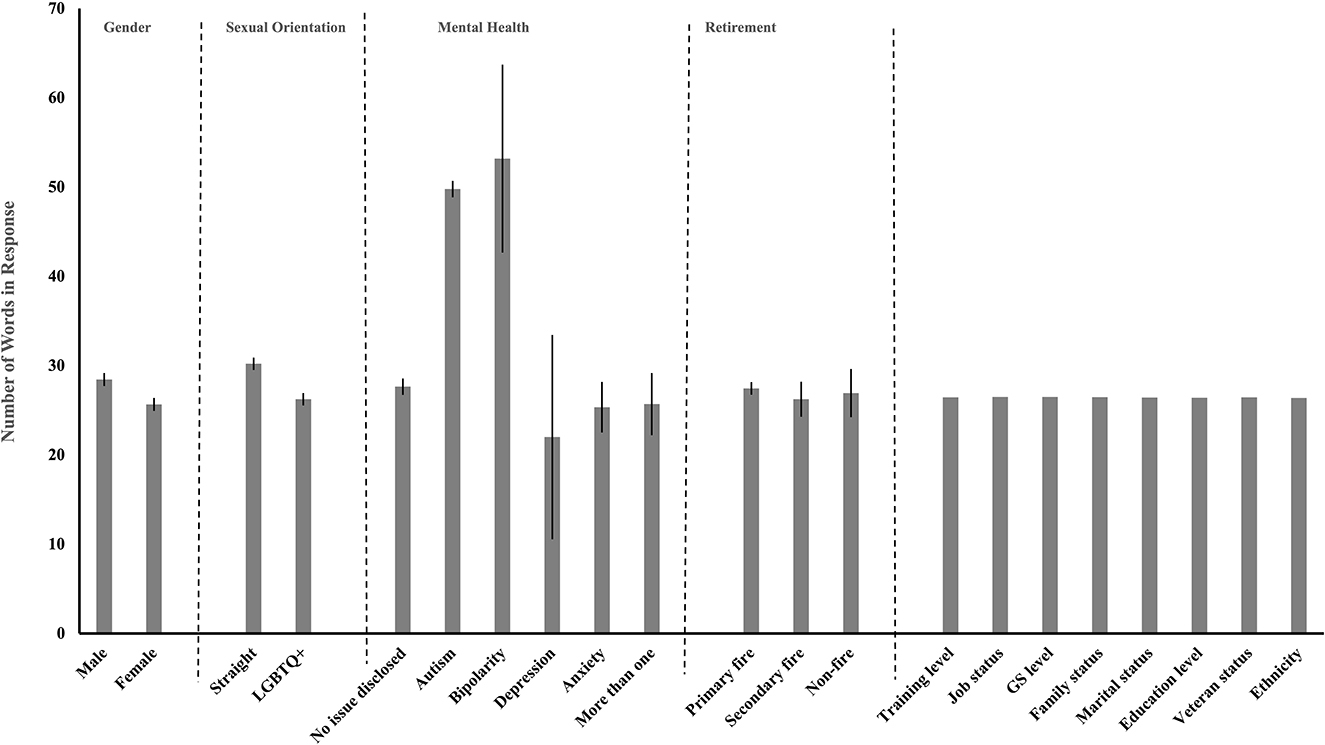

Across all questions, male responses were longer than female responses. Responses from straight respondents were longer responses than LGBTQ+ respondents. Respondents who reported being neurodivergent or having mental health issues wrote shorter responses than those who did not. Those individuals who had primary fire retirement also wrote longer responses than those who were either in secondary fire or had exited the field. We found no effect of training level, job status, GS level, family status, marital status, education level, ethnicity, or veteran status on the length of response (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Response length is significantly different between minority and majority groups within demographics. Mean = mean number of words written in a response. Alpha = 0.15. Gender P = 0.0005. Sexual Orientation P = 0.1444. Mental Health Status P = 0.0381. Retirement Status P = 0.0001. Bars represent standard error. Error bars are not presented for non-significant terms.

Personality and statement type

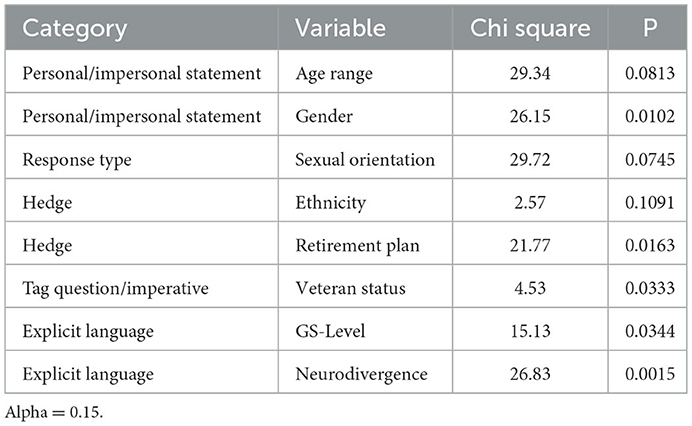

Survey respondents were more likely to write in a personal vs. impersonal style (54.85% personal). Age, gender, and sexual orientation significantly influenced whether a respondent wrote in a personal or impersonal manner. Younger respondents were more likely to write in a personal style than older respondents (Table 3). Female and non-binary respondents were more likely to write in a personal style than male respondents. LGBTQ + respondents were more likely to write in a personal style than straight respondents. We found no effect of neurodivergence, ethnicity, veteran status, family status, education level, marital status, retirement type, job status, or training level on whether a respondent wrote in a personal or impersonal manner.

Table 3. Demographic and socioeconomic variables (column 2) that are significantly correlated to language use categories (column 1) using a Chi-square analysis.

Overall, respondents framed their responses as facts (55.03%), opinions (24.55%) or directives (17.76%). Straight respondents were significantly more likely to use directives (18.05 vs. 13.55%), than LGBTQ+ respondents. LGBTQ+ respondents were significantly more likely to frame their response as an opinion than straight respondents (29.44 vs. 24.23%). We found no effect of age, gender, neurodivergence, ethnicity, veteran status, education level, marital status, family status, retirement type, or training level on the type of statement a respondent used when answering a question (Table 3).

Use of hedges, tag imperatives/questions, and apologetics

Overall, hedges occurred in 11.34% of responses. Individuals in primary retirement plans hedged less than individuals in secondary retirement or non-fire retirement plans. Respondents in primary fire retirement plans hedged on 11.24% of their responses. Secondary fire retirement plan respondents hedged on 13.14% of their responses, and individuals who had non-fire retirements hedged on 25.00% of their responses. BIPOC respondents hedged more frequently than white respondents (19.40% of responses vs. 9.18% of responses; Table 3).

Tag questions and tag imperatives (Table 1) were employed in 3.46% of responses. The only significant differences observed in tag question and tag imperative use was between veteran and non-veteran respondents. Veteran respondents used tags significantly more than non-veteran respondents (5.32% of responses vs. 3.20% of responses). Most respondents wrote in unapologetic language (98.38%), and we observed no demographic differences in the use of apologies among respondents.

Derogatory and explicit language

No significant differences were observed among demographic groups in the use of derogatory language. A total of 97.50% of responses contained no derogatory language. Explicit language was found in 2.75% of responses. Use of explicit language was significantly more common in respondents with less work experience and in individuals who identified as bipolar. Individuals who were GS-6 (middle experience level) used significantly less expletives than all other GS-levels. The most used expletives were shit (N = 50 occurrences) and fuck (N = 30 occurrences).

Discussion

We found significant differences in how different demographics responded to open response questions: Individuals who were part of underrepresented groups used fewer words and used personal language more often than the majority groups. BIPOC respondents and those in secondary retirement plans were more likely to frame their responses as opinions or hedge. Veterans were more likely to use tag questions/imperatives. Expletive and derogatory language use were rare among respondents: Respondents who identified as bipolar and respondents with less work experience were more likely to use expletives in their responses.

Previous studies have found depressed response rates among ethnic minorities in postal surveys (Sheldon et al., 2007) and women in web vs. paper surveys (Sax et al., 2003). Authors of these studies attribute these lower response rates to literacy, technological accessibility, and range of survey distribution. None of these studies measured response length. Our response rates matched the anticipated population demographics of our study population, suggesting we did not under sample minority wildland firefighters; however, minority respondents wrote shorter responses, which is not “non-response,” but does decrease the amount of information provided by the minority respondent. Decreased response length is not likely attributed to literacy, access, or limited survey distribution in our study, because our population is relatively educationally homogenous and all short responses were provided by preexisting participants (i.e., they were already responding to the survey, so distribution or access weren't limiting factors); therefore, social or cultural factors are the likely explanations for these findings (Wildland Fire Survey, 2022). Regarding women's short responses, Jones and Myhill (2007) write that the extensive use of language by women has been culturally observed as superficial or shallow, while in males it is observed as a mark of intellectual superiority: Female respondents may be (unconsciously) aware of this stereotype and may tailor their language accordingly to be perceived as serious and intelligent in their responses. We encourage future work on this topic to examine whether other minority groups may experience similar negative stereotypes.

Our results supported previous research that found that men were more likely to write about impersonal topics than women (Newman et al., 2008). We also found that younger, non-binary and LGBTQ+ respondents were more likely to write about personal topics than men. These differences were likely observable due to the open-ended nature of the prompts (Table 1; Newman et al., 2008). Hedges were employed by respondents in secondary retirement plans more often than those in primary retirement plans; secondary retirement plans are associated with those individuals that are secondarily involved in wildland fire work (e.g., may spend more of their time indirectly working in wildland fire), thus they may be less confident in their responses due to less time spent working in the field. BIPOC respondents were also significantly more likely to hedge than white respondents, possibly due to perceived power imbalances and the potential risks associated with direct negative comments about their experiences (Olvet et al., 2021). Granberg et al. (in review) found that BIPOC wildland firefighters were more likely to experience workplace injuries, difficulty in acquiring resources to resolve these injuries, and endure unwanted comments and jokes in the workplace at higher rates than their white co-workers. Women were no more likely to hedge than men, despite historical associations with women's speech (Meyerhoff, 1992). Likewise, tag questions and tag imperatives have also traditionally been associated with women's speech (Arbini, 1969; Dubois and Crouch, 2008; Bradley, 2009); however, there was no association between gender and the use of tag questions or imperatives in our data. We found an association between veteran status and the use of tag questions and imperatives. We can find no previous documentation of this association, and this topic warrants further investigation.

Practical implications

These results provide a window into the communication styles of specific demographics of the wildland fire workforce and provide an opportunity to understand how incident reporting, complaint filings, and other written mechanisms of documentation may be shaped by demography, including gender, ethnicity, sexual orientation, worker status, experience level, veteran status, and health status. Importantly, this knowledge can help build inclusive systems that allow all members of the wildland firefighting community to access their resources and communicate their needs in an effective and equitable manner.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

RG and SP did not complete any of this work on behalf of the United States Forest Service nor did they complete it during their work hours. It was completed independently and without federal resources. RV conducted statistical analysis, coded data, binned, and wrote the manuscript. RG conducted the survey. SP binned and provided subject matter expertise. MRa and JH coded, data verified, and edited the manuscript. MRi coded and data verified. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Acknowledgments

Foremost, over 700 wildland firefighters took this survey, and we are indebted to them for their frankness and time. Dylan Johnson and Greta Adams assisted in coding. Student support has been provided by the Missouri S&T College of Arts, Science and Education. The Missouri S&T Biological Sciences Write Club encouraged the production of this manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Arbini, R. (1969). Tag-questions and tag-imperatives in English. J. Linguist. 5, 205–214. doi: 10.1017/S0022226700002243

Baldwin, L., and Carpeaux, E. (2018). Rape, Harassment and Retaliation in the U.S. Forest Service: Women Firefighters Tell Their Stories. PBS News Hour. Available online at: https://www.pbs.org/newshour/show/rape-harassment-and-retaliation-in-the-u-s-forest-service-women-firefighters-tell-their-stories (accessed August 15, 2022).

Bradley, P. H. (2009). The folk-linguistics of women's speech: an empirical examination. Commun. Monogr. 48, 73–90. doi: 10.1080/03637758109376048

Cech, E. A., and Waidzunas, T. (2022). LGBTQ@NASA and beyond: work structure and workplace inequality among LGBTQ STEM professionals. Work Occup. 49, 187–228. doi: 10.1177/07308884221080938

De Klerk, V. (2009). Expletives: men only? Commun. Monogr. 58, 156–169. doi: 10.1080/03637759109376220

Dubois, B. L., and Crouch, I. (2008). The question of tag questions in women's speech: they don't really use more of them, do they? Lang. Soc. 4, 289–294. doi: 10.1017/S0047404500006680

Eriksen, C. (2019). Negotiating adversity with humour: a case study of wildland firefighter women. Polit. Geogr. 68, 139–145. doi: 10.1016/j.polgeo.2018.08.001

Fraser, B. (2010). “Hedging in political discourse: the Bush 2007 press conferences,” in Perspectives in Politics and Discourse, eds U. Okulska and P. Cap (Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing).

Gouliquer, L., Poulin, C., and McWilliams, J. (2020). Othering of full-time and volunteer women firefighters in the Canadian fire services. Qual. Soc. Rev. 16, 48–69. doi: 10.18778/1733-8077.16.3.04

Grahame Gordon Wildfire Management Services (2014). Workforce Demographic Issues in Canada's Wildland Fire Management Agencies. Available online at: https://www.ccmf.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/Workforce-Demographic-Issues-in-Canada's-Wildland-Fire-Management-Agencies.pdf (accessed August 15, 2022).

Granberg, R., Pearson, S., and Verble, R. In review. Attitudes, work experiences, morale & working conditions among federal wildland firefighters. Int. J. Wildl. Fire.

Grassroots Wildland Firefighters (2021). Impacts of the Profession as Recognized by Spouses and Partners. Available online at: https://www.grassrootswildlandfirefighters.com/partnerspouse-survey (accessed August 15, 2022)

Holmes, J. (1989). Sex differences and apologies: one aspect of communicative competence. Appl. Ling. 10, 194–213. doi: 10.1093/applin/10.2.194

Hughes, S. E. (1992). Expletives of lower working-class women. Lang. Soc. 21, 291–303. doi: 10.1017/S004740450001530X

Jacobi, L. L. (2014). Perceptions of profanity: how race, gender, and expletive choice affect perceived offensiveness. N. Am. J. Psychol. 16, 261–276. doi: 10.1037/e603132013-001

Jones, S., and Myhill, D. (2007). Discourse of difference? Examining gender differences in linguistic characteristics of writing. Can. J. Educ. 30, 456–482. doi: 10.2307/20466646

Jung, A. M., Jahnke, S. A., Dennis, L. K., Bell, M. L., Burgess, J. L., Jitnarin, N., et al. (2021). Occupational factors and miscarriages in the US fire service: a cross-sectional analysis of women firefighters. Environ. Health 20, 116. doi: 10.1186/s12940-021-00800-4

Loomis, D., and Richardson, D. (1998). Race and the risk of fatal injury at work. Am. J. Public Health 88, 40–44. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.88.1.40

McDermott, V. (2019). ‘It's a Magnifying Glass': The Communication of Power in a Remote Field Station (Thesis). University of Alaska Fairbanks, Fairbanks, AK.

McDermott, V., Gee, M., and May, A. (2022). Women of the Wild: Challenging Gender Disparities in Field Stations and Marine Laboratories. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

McGee, M. M. (1999). The effects of workplace marginalization on individual African American women: a collective case study (Ph.D. Dissertation). The Fielding Institute, Santa Barbara, CA.

Meyerhoff, M. (1992). “A sort of something: hedging strategies on ouns,” in Working Papers on Language, Gender and Sexism. AILA Commission on Language and Gender, 59–72.

Mitchell, K. M. (2019). Sisters in the brotherhood: experiences and strategies of women wildland firefighters (M.S. thesis). University of Reno Nevada, Reno, NV.

Newman, M. L., Groom, C. J., Handelman, L. D., and Pennebaker, J. W. (2008). Gender differences in language use: an analysis of 14,000 text samples. Dis. Process. 45, 211–236. doi: 10.1080/01638530802073712

O'Brien, P., and Campbell, D. (2021). “Wildland firefighter psychological and behavioral health: preliminary data from a national sample of current and former wildland firefighters in the United States,” in International Association of Wildland Fire 6th Annual Human Dimensions Conference (virtual conference).

Olvet, D. M., Willey, J. M., Bird, J. B., Rabin, J. M., Pearlman, R. E., and Brenner, J. (2021). Third year medical students impersonalize and hedge when providing negative upward feedback to clinical faculty. Med. Teach. 43, 700–708. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2021.1892619

Pratt, D. S., Marval, L. H., Darrow, D., Stallones, L., May, J. J., and Jenkins, P. (1992). The dangers of dairy farming: the injury experience of 600 workers followed for two years. Am. J. Ind. Med. 21, 637–650. doi: 10.1002/ajim.4700210504

Riley, K. L., Steelman, T., Sallcrup, D. R. P., and Brown, S. (2020). “On the need for inclusivity and diversity in the wildland fire professions,” in Proceedings of the Fire Consortium-Preparing for the Future of Wildland Fire, eds S. M. Hood, S. Drury, T. Steelman, and R. Steffens (Missoula, MT; Fort Collins, CO. U.S. Department of Agriculture. Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station), 2–7.

Sacks, B. (2022). Leaked data shows California is short more than a thousand wildland firefighters. Buzzfeed News. Available online at: https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/briannasacks/california-firefighter-staffing-forest-service

Sax, L. J., Gilmartin, S. K., and Bryant, A. N. (2003). Assessing response rates and nonresponse bias in web and paper surveys. Res. High. Educ. 44, 409–432. doi: 10.1023/A:1024232915870

Schumann, K., and Ross, M. (2010). Why women apologize more than men: gender difference in perceiving offensive behavior. Psychol. Sci. 21, 1649–1655. doi: 10.1177/0956797610384150

Sharkey, B. J. (2016). Fitness for wildland fire fighters. Phys. Sports Med. 9, 92–102. doi: 10.1080/00913847.1981.11711059

Sheldon, H., Rasul, F., and Graham, C. (2007). Increasing Response Rates Amongst Black and Minority Ethnic and Seldom Heard Groups. Report by the Acute Coordinate Center for the NHS Patient Survey Programme of the Picker Institute Europe. National Health Institute, Oxford, 75.

Siebold, G. L. (2007). The essence of military cohesion. Armed Forces Soc. 33, 286–295. doi: 10.1177/0095327X06294173

Staley, C. M. (1978). Male-female use of expletives: a heck of a difference in expectations. Anthropol. Ling. 20, 367–380.

Stanley, I. H., Hom, M. A., Gai, A. R., and Joiner, T. E. (2018). Wildland firefighters and suicide risk: examining the role of social disconnectedness. Psychiatry Res. 266, 269–274. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.03.017

Sugimoto, N. (1998). “Sorry we apologize so much”: linguistic factors affecting Japanese and U.S. American styles of apology. Intercultural Communication Studies VIII: 1998–1999.

Wildland Fire Survey (2022). Available online at: www.wildlandfiresurvey.com (accessed January 17, 2023).

Keywords: wildfire, workplace behavior, natural resources, mental health–related quality of life, qualitative survey data, work-life balance, language use and attitudes, environmental health

Citation: Ragland M, Harrell J, Ripper M, Pearson S, Granberg R and Verble R (2023) Gender, sexual orientation, ethnicity and socioeconomic factors influence how wildland firefighters communicate their work experiences. Front. Commun. 8:1021914. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2023.1021914

Received: 17 August 2022; Accepted: 23 January 2023;

Published: 07 February 2023.

Edited by:

Amy May, University of Alaska Fairbanks, United StatesReviewed by:

Breeanne Jackson, University of California, Merced, United StatesJennifer M. Gee, University of California, Riverside, United States

Copyright © 2023 Ragland, Harrell, Ripper, Pearson, Granberg and Verble. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Robin Verble,  dmVyYmxlckBtc3QuZWR1

dmVyYmxlckBtc3QuZWR1

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

‡These authors have contributed equally to this work and share senior authorship

Miranda Ragland1†

Miranda Ragland1† Robin Verble

Robin Verble