- 1Center for Culture-centered Approach to Research and Evaluation (CARE), Massey University, Wellington, New Zealand

- 2Center for Culture-centered Approach to Research and Evaluation (CARE), Palmerston North, New Zealand

In this work, we explore the role of land in Indigenous theorizing about health, embodied in a land occupation that resisted a climate-adaptive development project imposed on the community from the top down by the local government. The proposed development project of building a stop bank on the Oroua River sought to alienate Māori from the remnants of the land. Embedded in and emerging from a culture-centered academic-community-activist partnership, an advisory group of Māori community members om the “margins of the margins” came together to participate in the occupation of the land to claim it as the basis for securing their health. This study describes the occupation and the role of our academic-activist intervention in it, theorizing land occupation as the root of decolonizing health emerging from Indigenous struggles for sovereignty (Tino rangatiratanga). The community advisory group members brought together in a culture-centered intervention, collaborated in partnership with the academic team, generated video narratives that resisted and dismantled the communicative inversions produced by the settler colonial state to perpetuate its extractive interests and produced communicative resources that supported the land occupation led by the broader Whānau. This study concludes by arguing that the culture-centered approach offers a meta-theory for decolonizing health communication by building voice infrastructures that support Indigenous land struggles.

Introduction

You have no[sic] existence without land. Your health diminishes without your land. I didn't know about the health thing. Now we end up growing food, getting political, and bringing in the Human Rights Commission! (laughter). Well, there you go, it stands to say in itself: health is a main, big issue. They desecrated the land and this is the reason why we protested, we protested for that—four weeks, yeah. (Marama,1 Community advisory group member, land occupation).

According to Marama, a community advisory group member participating in the culture-centered process of co-creating voice infrastructures in Feilding, Aotearoa New Zealand, the community-led health intervention took the form of a land occupation that resisted a settler colonial development project positioned as climate adaptation, based on the Indigenous theory that land anchors everyday meanings of health (Dutta, 2004a; Moewaka Barnes and McCreanor, 2019; Thom and Grimes, 2022). A substantive body of scholarship and activist articulation on Indigenous health centers on the interlinkages between land and health for Indigenous people (Awatere, 1984; Walker, 1984; Nepe, 1991; Pihama, 1993, 2012; Taki, 1996; Waitangi Tribunal, 1996, 1999b, 2011, 2021; Smith, 1997, 2017; Rennie et al., 2000; Pihama et al., 2002; Dutta, 2004b; King et al., 2009; McCormack, 2011; Mikaere, 2011; Smith et al., 2012; Ryks et al., 2014; Lowry and Simon-Kumar, 2017; Mutu, 2017; Ruru, 2018; Bargh and Van Wagner, 2019; CARE Massey, 2019a,b; Hond et al., 2019; Jones, 2019; Moewaka Barnes and McCreanor, 2019; O'Bryan, 2019; Reid et al., 2019; Bargh, 2020; Bargh and Jones, 2020; Thom and Grimes, 2022). The connection to land forms the basis for Indigenous voicing on health, shaping the very definitions of health, everyday meanings of health, experiences of mental health and wellbeing, exposure to toxins, exposure to violence, lack of access to prevention resources, experiences of trauma, and access to basic prevention and health care resources (Awatere, 1984; Dutta, 2004b; Pihama, 2012; Moewaka Barnes and McCreanor, 2019; Bargh, 2020; Bargh and Jones, 2020).

Drawing on Māori theories of health, Thom and Grimes (2022) outline the ways in which land loss has shaped Māori experiences of health in settler colonial Aotearoa New Zealand. Across spaces of disenfranchisement in the Southern hemisphere and places of marginality within the settler colonial North, struggles over land brought on by the interpenetrating forces of colonialism and capitalism shape the struggles for health (Awatere, 1984; Royal, 1988, 2012; Irwin, 1994; Roberts et al., 1995; Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment, 1998; Hayward, 1999; Harmsworth et al., 2002; Cheyne and Tawhai, 2008; Coates, 2009; Local Government New Zealand, 2011, 2017; Durie, 2012; Roberts, 2013; Forster, 2014; Cheyne, 2015; Ruckstuhl et al., 2015; Brown et al., 2016; Jacobson et al., 2016; Bell, 2018; Bishop, 2020; Resource Management Review Panel, 2020; Ellis, 2021; LGNZ, 2021). In this study, based on an ethnographic account of culture-centered organizing in the form of Māori-led land occupations to secure health and wellbeing in resistance to the racist settler colonial structures in Aotearoa New Zealand, we map the processes of communicative erasure and resistance to this erasure through articulations made on voice infrastructures co-created through culture-centered processes and respond to the questions: How do settler-colonial erasures of voice affect the health of Indigenous communities? What does solidarity look like as a method of health communication amid Indigenous struggles to secure access to health through land reclamation and resistance to land loss?

Drawing on the culture-centered approach (CCA), which outlines the interplay between communicative inequality, inequality in the distribution of information and voice resources, and health inequality (Dutta, 2008, 2011, 2012, 2014, 2016, 2018a; Dutta and Elers, 2020), we argue that the settler colonial erasure of Indigenous voice drives the health inequalities experienced by Indigenous communities, which are materialized in the dispossession of Indigenous people and communities from land and health-sustaining resources (Dutta, 2004a,b; Moewaka Barnes and McCreanor, 2019; Thom and Grimes, 2022). The CCA, we claim, offers a decolonizing framework for health communication by centering voice infrastructures that support embodied struggles for health through Indigenous land occupations and resistance to land loss. In voicing our embodied academic-activist solidarities situated amid land struggles, we foreground the necessary relationship between activism and critical health communication as embodied practices of the struggle to secure health by building voice infrastructures. Our intervention as voice infrastructures, developed by the community advisory group participating in the culture-centered process, complicates the concept of the Global South, by making the South visible as a marker of settler colonial dispossession within the ambit of the Global North (Dutta and Pal, 2020). In other words, we conceptualize the South as spaces of land occupation, extraction, exploitation, and dispossession within the settler colonial state that is otherwise categorized as the Global North, which are linked to spaces of dispossession in the geographical South that are the targets of oppressions carried out by Western/neoliberal hegemony.

We suggest that solidarity as a health communication method emerges from within community struggles takes the form of community leadership developed in advisory groups co-created through the culture-centered approach, and is sustained through ongoing collaborations between academics, activists, community advisory group members, and the broader community. Solidarity as a concept thus offers a radical turn by inverting the concept of a health intervention, defining an intervention as communication strategies co-created by Indigenous communities that negotiate ongoing marginalization perpetuated by the settler colonial state. The concept of intervention thus disrupts and re-imagines the organizing registers of health, communication, and community put forth within the architectures of settler colonial academia, and presents the concept of voice infrastructures in Indigenous communities within the settler colonial state that challenge the ongoing processes of erasure from discursive registers. We suggest that the turn to land in this sense serves as an anchor for decolonizing health communication through the concept of voice infrastructures, keeping academics in place, situating us in the struggles for land to secure health, locating our bodies in struggles, and holding our bodies accountable. That securing health is centered on returning Indigenous lands and resisting land theft builds a radical register for health communication that links decolonization to the necessary risks of embodied activism in community-led land occupations. For decolonizing health communication, activism through sustained relationships based on whakapapa (whakapapa is a fundamental Māori concept that connects the individual to ancestors, the atua (gods), ancestral land, and tribal groupings) is the necessary and critical first step rooted in the struggle to maintain land sovereignty (Tino rangatiratanga).

Land and Indigenous health

Across the Global South and North, Indigenous communities see land as the fundamental source of their health and wellbeing (Dutta, 2004a,b; Moewaka Barnes and McCreanor, 2019; Thom and Grimes, 2022). The dispossession of colonized peoples from land and resources on one hand fueled the industrial revolution and fed the capitalist project, and on the other hand, unleashed cycles of perpetual violence (military, police, carceral, and extractive) against colonized peoples. The alienation of the colonized from the land, the ongoing processes of displacement, and the incorporation of the expelled margins of the colony into the capitalist processes of exploitation are fundamental threats to the health and wellbeing of Indigenous communities in settler colonies worldwide. Many Indigenous peoples around the world have experienced massive land loss brought about by settler colonial forces (Behrendt, 2010). For Indigenous communities, alienation from land underlies the layers of trauma that fundamentally shape the risks to health and wellbeing. Indigenous groups in Mexico face toxic contamination from extractive mining practices (Goldtooth, 2010). In North America, Indigenous communities lack access to potable water and face increased exposure to heat (Norton-Smith et al., 2016). In contexts such as Palestine, land dispossession is linked to acts of military violence, which directly impacts health (Asi et al., 2022).

The land is a core determinant of Māori health and wellbeing (Hond et al., 2019; Jones, 2019; Moewaka Barnes and McCreanor, 2019). The ongoing settler colonial process in Aotearoa, New Zealand has resulted in large-scale land loss for Māori, deeply harming the health and wellbeing of their communities (Durie, 2013). Moewaka Barnes and McCreanor (2019) analyze studies that delineate markers of population change in Aotearoa, margins of life expectancy with rates and figures of land dispossession, and the impact of racism on health. The study maps out the onset of colonization as the basis for the disparate health outcomes experienced by Māori. The violence of colonialism is experienced in the vastly disproportionate burden of poor health borne by the Māori. According to the Ministry of Health (2015), the ischemic heart disease (IHD) mortality rate among Māori was 2.14 times higher than non-Māori. The total cancer mortality rate for Māori adults was 1.79 times higher than that for non-Māori adults. Māori women had a lung cancer registration rate 4.26 times higher than non-Māori women. The lung cancer mortality rate among Māori women was also more than four times that of non-Māori women. Māori suicide rates were nearly double that of non-Māori. The rate was higher for Māori women, who were 2.22 times more likely to commit suicide than non-Māori women. The mortality rate for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease among Māori aged 45 and over was 2.94 times higher than non-Māori in the same age group. In 2013–2014, Māori type 2 diabetes rates were ~50% higher or 1.49 times higher than non-Māori. The rate of kidney failure as a complication of diabetes for Māori aged 15 years and over was 5.55 times that of non-Māori. Lower limb amputations as a result of diabetes amounted to 1.7 times that of non-Māori. In 2010–2012, Māori stroke mortality was 1.56 times that of non-Māori.

Colonial land occupation in Aotearoa

In Aotearoa, New Zealand, a collection of ~22 legislative acts provided the framework for the statutory confiscation of Māori land by the colonial government, erasing Māori titles to their ancestral lands (Boast, 2010b). The colonial legal infrastructure was designed to confiscate Māori land (see Boast, 2010a, p. 263–266), with the colonial government taking possession of Māori land to then sell to settlers at a higher price (Gilling, 2020), which in turn financed the colonial warfare against Māori. The cycle of land occupation was marked by colonial warfare as the deployment of violence that was designed to forcibly remove Māori from their ancestral lands for the benefit of the settler colony (Wynyard, 2017). The legal infrastructure of dispossession, embodied in the New Zealand Settlements Act (1863) and its many amendments enacted in (1864), (1965), and (1866), legitimized and catalyzed the legal onslaught on Māori and their ancestral lands.

The Waitangi Tribunal noted in 1996 that the framing of the New Zealand Settlements Act (1863) as an instrument to achieve law and order and keep the peace obscured the land confiscation that formed its underlying infrastructure. Although the act did not contain the word “confiscation”, its outcome was precisely the appropriation of Māori land. The manipulation built into the application of this Act meant that Māori were often deemed to be acting contrary to the purpose of the Act itself. They were marked as deviant and therefore targets of land confiscation violence if they did not swear allegiance to the Queen of England, or if they resisted the intrusion of colonial military posts on their land. It is worth noting here the communicative reversal of the whiteness of the Crown that turned the colonial violence of land confiscation into an instrument for achieving law and order (see Dutta, 2018b; Dutta and Hau, 2020). In the eyes of the colonial government, Māori living their daily lives on the land and not allowing colonial intrusions, which was their right, was enough to trigger the use of the penal provisions of the New Zealand Settlements Act 1863 against them (Jackson, 1993; Waitangi Tribunal, 1996, 1999a; Gilling, 2020).

This colonial Parent Act catalyzed the large-scale land confiscation in several districts in Aotearoa (see Hancock et al., 2020), rendering Māori landless, alienating them from the land, and forcing them into exile. The settler colonial processes of land occupation and extraction formed the basis for the ongoing displacements experienced by Māori in Aotearoa, who were targeted by the twin forces of colonialism and capitalism (Awatere, 1984; Royal, 1988, 2012; Irwin, 1994; Roberts et al., 1995; Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment, 1998; Hayward, 1999; Harmsworth et al., 2002; Basu, 2008; Cheyne and Tawhai, 2008; Coates, 2009; Local Government New Zealand, 2011, 2017; Durie, 2012; Roberts, 2013; Forster, 2014; Cheyne, 2015; Ruckstuhl et al., 2015; Brown et al., 2016; Jacobson et al., 2016; Bell, 2018; Bishop, 2020; Resource Management Review Panel, 2020; Ellis, 2021; LGNZ, 2021). The New Zealand Settlements Act was complemented by the Suppression of Rebellion Act (1863), which gave extensive powers to the colonial military to invade, terrorize, and kill Māori—men, women, children, and the elderly (Coromandel-Wander, 2013). Here, the deployment of large-scale violence by the settler colonial state that directly adversely impacted the health of Māori should be noted. Simultaneously, the New Zealand Loans Act (1863) was designed to obtain a loan from England to enact land confiscation; to be repaid from the anticipated sale of confiscated Māori land (Boast, 2010b; Gilling, 2020). These laws, which enabled the killing of Māori, are nothing less of pre-meditated terrorism and genocide enacted by the colonial government against Māori (Anthony, 2021).

In addition, numerous additional laws and policies designed to systematically dispossess Māori of their ancestral lands were quickly enacted (Boast, 2010b) as reinforcements to prop up the New Zealand Settlements Act (1863) and open up land for settlement. Wynyard (2017) highlights that even the use of the word “settlement” belies the actual reality that took place in many districts, which was the forced colonial imposition and theft of Māori land.

Since the enactment of the colonial government's strategy to relentlessly pursue the acquisition of Māori land, at all costs (lives and finances), the Māori land holdings that remain today equate to ~5% of the total land area of Aotearoa, New Zealand (Wynyard, 2019). Communal land retention has been inextricably intertwined with Māori wellbeing. The effects of such extensive land loss have reverberated across generations (Jackson, 1993; Walker, 2004).

Colonization of the Oroua River

The Oroua River is ~140 km long and flows south from the headwaters of the Ruahine Ranges, to the Feilding township, and out to the Manawatu River, south of Palmerston North, Aotearoa, New Zealand. Both the Oroua River and the Ruahine Ranges are important landmarks for Whānau, Hapu, and Iwi. Ngāti Kauwhata is one Iwi that has a long-standing relationship with the Oroua River. Ongoing processes of development and industrialization have threatened the relationship of Whānau, Hapu, and Iwi with the river, erasing the relationship of Māori with the river. Aroha, a Māori community member living by the river stated that:

…the glue that held us together [referring to the land] is no longer there and that has created an unwellness and I think that was strategic and the council and governments are, purposefully trying to get more of a stronghold over this land because it is so fertile. And, um, and we are, our rivers are unwell and if we go back to the spiritual being of who we are, they are our veins. So…if our veins are unwell, we are unwell. If our land is, our whenua is unwell, we are unwell. So, we are unwell and then marginalized to access to health care, we cannot even do that because of the price that it costs for us to go… So, regardless of whether you have money or not in this town, we have been cut off from who we are, um, and we have to find a way to get back to that and this is the only way I think we are going to get well [sic].

In the narration by Aroha, the intertwined relationship between land and health should be noted, with health being framed in the wider ecosystem. Land, rivers, connection to ancestors, connection with the wider Whānau, and connection to the spiritual being constitute the everyday meanings of health. Ongoing settler colonial expansion threatens Māori health through further alienation from the land.

In January 2020, the Horizons Regional Council (“Horizons”) took possession of one of the last few remaining acres of ancestral land, located close to Kauwhata marae, sparking a land occupation by the Feilding Advisory Group and their Whānau to protest the modern-day confiscation of their land (see Ganesh et al., 2021; Mika et al., 2022). Horizons took the land to build a stop bank to prevent flooding in the area, allegedly caused by the 1-in-100-years flood that occurs in the district.

The purpose of the stop bank proposal, according to the Council, is to protect the adjacent rural area from the one 100-year flood that last struck the region in 2004. Among the rural land blocks affected by the stop bank proposal are around 12 blocks of ancestral Māori land, a few houses, and an ancestral marae where Iwi members gather to participate in events and meetings according to Iwi custom. Farmland and a proposed new lifestyle housing development are also in the area. In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, a Māori papa kāinga (village) existed in this location up until the government's urbanization drive pushed Māori to the nearby urban town of Feilding and the city of Palmerston North following World War II (Durie, 2013). The stop bank is estimated to be ~3.3 Km in length and is being erected along the south bank of the Oroua River. The Council proposed to confiscate ancestral Māori land within the Ngāti Kauwhata Iwi [tribal] area as a site for the stop bank.

Land occupation as resistance

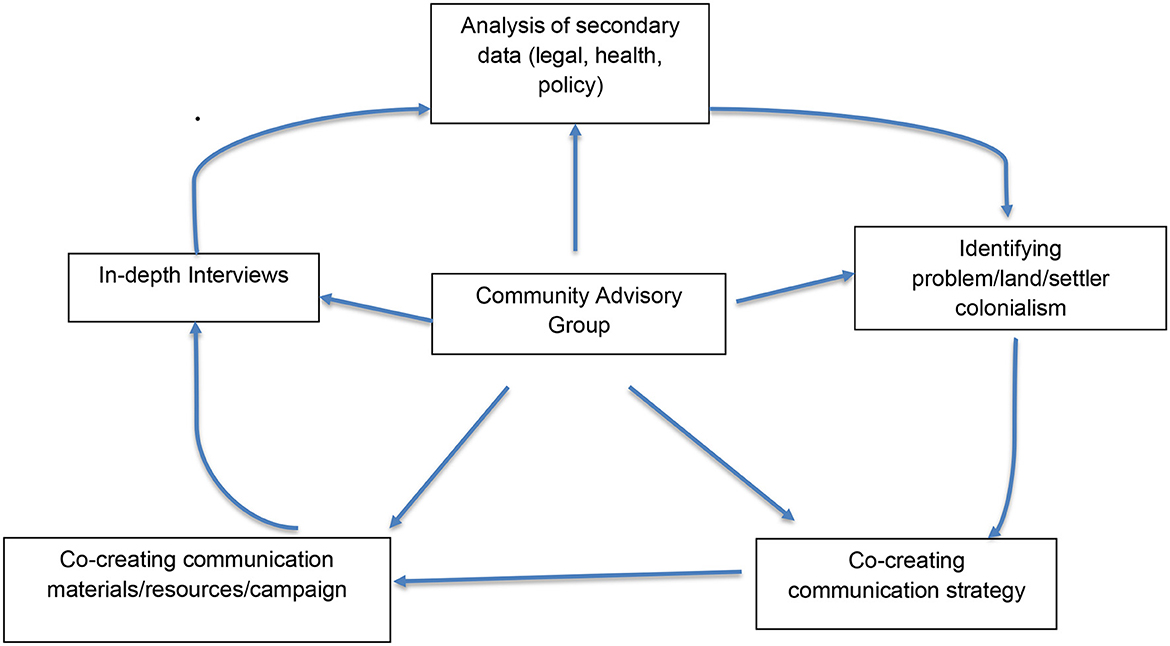

Our culture-centered process included building a community advisory group, co-designing in-depth interview protocols in the advisory group and conducting in-depth interviews, co-analyzing data emergent from the in-depth interviews, identifying the problem/issue to be addressed, and developing communication strategies and tactical materials (Dutta, 2004a,b; Figure 1). Members of the community advisory group had identified land theft and pollution of the river as two key drivers of poor health in the community. When the council started building the stop bank on the river, community members noted the racist decision-making process that erased Māori voices to carry out the land confiscation. This is the opinion of Kahurangi:

So, when the land… When Horizons pretty much, I want to say… Invaded the land, um, without the consent of the legal owners or the beneficiaries of the land, when they dug it all up... That was racist, certainly, in my view, that was racist. A lot of us thought it was racist and it was racist because I guess they assumed, you know, that they had this legal backing to be able to do it, and regardless of what the people said at their consultation hui, those people that did attend… Even though they said they did not want it, regardless of all of that, they still went ahead and did it anyway and that is racist, just because it was Māori land. Even though there were alternatives on non-Māori land to put the stop bank there, they chose and we know, um, that was one of the ways in which our ancestors were dispossessed of land when the government purposely chose Māori land to put roads on, you know. Like, there is a road that goes to Feilding from Palmerston North and there are bends in it and that's because it went on Māori land. To save European land, it will cut through Māori land, and we know, we have always known, that that is one of the ways in which we have been dispossessed of land. So when this happened, we were just like “this must be the 1800s”. This is what they're still doing [sic].

For Kahurangi and members of the advisory group, the communicative erasure of community agency in the decision-making process reflected the racism of the settler colonial government. Participants in the advisory group meetings saw land confiscation under the guise of climate-adaptive development as a feature of climate colonialism, continuing to perpetuate the disenfranchisement of Māori. They pointed out how the building of the dam on Māori land, while not pursuing other alternative land options to build the stop bank, was reflective of the ongoing processes of settler colonialism that alienate Māori from the rest of the land.

To resist the colonial occupation of the river, Whānau occupied their ancestral land. The Whānau members of the community advisory group co-created a storyboard in partnership with our production team and built a video campaign to speak back to the Horizons Council, while also preparing submissions outlining the effects of further land dispossession on Whānau health and wellbeing. Our academic team supported the submission with research into legal and policy documents, with Christine Elers using her legal training to closely examine the communicative processes of decision-making.

Through their Indigenous knowledge rooted in their relationship with the river, Whānau also advised Horizons on how to strengthen the riverbanks to allow the river to flow freely without overflowing onto adjacent lands. By centering the voices of the Indigenous people who have lived beside the river for over 150 years, solutions are found in Indigenous knowledge of the ebb and flow of their ancestral river. The river, understood in relation to the Indigenous people who have lived beside it, is interpreted in a decolonizing framework as a source of health and wellbeing. The occupation of the ancestral land creates a register for dismantling the Eurocentric discourse of development and decolonizing the Eurocentric approach to building the embankment by representing the violence that is embedded into the development decision-making.

Moreover, the participation of the “margins of the margins” of the Whānau in democratic resistance creates openings for a voice democracy rooted in Indigeneity. The articulations of the Whānau voiced through the land occupation make visible Indigenous sovereignty that is erased from the dominant communicative spaces of the settler colonial state. The rationality of the mainstream discourse on development is debunked and constructed as both erroneous and illegal, making visible the lack of reason for the confiscation of ancestral lands. Instead, authentic notions of development lie with the Whānau and their strategies to look after the river and surrounding land. During the land occupation and after two meetings between the Whānau and Horizons, Horizons apologized for taking the land and returned it to the Whānau in March 2020.

The role of the CCA in land occupation

The Feilding Advisory Group had been co-created by our academic team, housed under the umbrella of the Center for Culture-centered Approach to Research and Evaluation (CARE), as part of the culture-centered process of building voice infrastructures on the “margins of the margins.” One of us, Christine (Nga Hau), who is part of the Whānau, has been working since 2019 to build a community advisory group, drawing on the “margins of the margins2” within the community of Feilding. To do this, she has drawn on the CCA to reflexively explore the spaces of erasure within the community. At the same time, she has relied on Whakapapa to bring a relational approach to the work of building the community advisory group. The other author, Mohan, who is a migrant to Aotearoa from Bengal, a former British colony that was one of the earliest global sites of colonization by the British East India Company, engaged with Christine on the framework of the CCA, the concepts of voice infrastructure and marginalization, and decolonizing methodologies for building the advisory group based on the concept of “margins of the margins”. In addition, Mohan attended community advisory group meetings and facilitated discussions alongside Christine, co-facilitating the analysis of problems and the development of potential solutions. Attending to the idea that communicative inequalities within community spaces reflect the distribution of voice infrastructures, we worked to invite Whānau members who reflected the experiences of marginalization. This process of building the voice infrastructure on the “margins of the margins” addressed the inequalities within community spaces in Feilding by asking, “What voices are not represented here?” “How do we invite those voices in?” Christine engaged in ongoing dialogue with Whānau members, with Mohan, and critically reflected on issues of power in community spaces to build and sustain the Community Advisory Group. The group comprised core members who offered leadership and while dynamically inviting in new members, continually attending to the concept of erasure.

In the first phase of building the voice infrastructures in the community, we co-designed interview protocols in the community advisory groups, followed by carrying out 30 in-depth interviews with Māori participants with lived experiences of socioeconomic challenges and communicative inequalities. The relationship between the formation of the advisory group and the in-depth interviews was iterative, with additional participants from the interviews being brought into the advisory groups and meetings held to make sense of the interviews, flesh out some of the research themes, and identify the problems and the corresponding solutions. Based on their understanding of the themes emerging from the interviews, the advisory group chose the issue to collectivize on, plan, and implement an intervention that included an anti-racism campaign, a land occupation, underscored by the #OurWhānauVoicesMatter campaign, a hui (meeting) with the anti-racist activist Andrew Judd around Māori wards, participation in the Māori wards protest in Feilding, and the planning and implementation of a strategy to connect with ancestral land to grow a māra kai called Kaiiwi, which means “feed the people”. Moreover, after carrying out the land occupation and māra kai initiatives, we conducted post-campaign in-depth interviews with 16 advisory group members. The interview questions were discussed and reworked at an advisory group meeting with the participants prior to the interviews. We carried out the interviews in-person and over the phone. All interviews were transcribed by Christine Elers, supported by two members of the community advisory group, resulting in 446 pages of single-spaced transcript in phase 1 and 189 pages of single-spaced transcript in the post-campaign phase. In addition, we kept journal notes reflecting on the advisory group meetings, resulting in 23 single-spaced pages of notes. Finally, to support the land occupation in opposition to the community development project carried out by the council, we analyzed 103 pages of legislation and 77 pages of council notes and maps. This analysis shaped the land occupation strategy, including engagement with the Crown.

The advisory group had been meeting one to two times a month for ~9 months when the Horizons development project started in the community. In the first phase of the research, the advisory group identified the erasure of their voices as the primary driver of the health inequities they experienced. Earlier in the advisory group meetings, members had foregrounded their organizing to lay claim to voice, scripting together a slogan, “What we say matters”. Under this motto, they had been putting together scripts and storyboards that foregrounded their voices, laid claims to their voices, and articulated their sovereignty through their voices. They were involved in co-producing a video with the production team at CARE around the concept of voice sovereignty. Throughout the multiple iterations of advisory group meetings, they articulated the connection of health to the land and the river. In co-creating the in-depth interview protocol and in making sense of the in-depth interviews, they kept returning to the river as a source of health and wellbeing. During these conversations in the advisory group, the Horizons development project started being rolled out by the council and the advisory group members saw this as another instance of land grabbing as climate colonialism.

To make sense of the development project, advisory group members turned to an analysis that saw the project as another step in the Crown's land grab. The group worked together with Whānau in occupying the land, strategically planning the form of the occupation, the communication framework around the land occupation in the form of a communication campaign supporting the occupation, and the forms of engagement with the representatives of the Crown. The advisory group meetings as voice infrastructures owned by the “margins of the margins” of the Whānau emerged as spaces for articulating Tino rangatiratanga, situating Indigenous sovereignty as land claims in the context of negotiations over health and wellbeing. As the advisory group members planned their participation in the land occupation, including how resources would be mobilized to support and sustain the occupation, our academic and production teams worked with them to co-create the communication strategy, facilitate the development of communication tactics (posters, art installations, t-shirts, banners, videos, and a social media page), and co-create the communication tactics. Christine analyzed the policy documents, the legal framework, and the paperwork that was used by the council. This critical analysis of the engagement process was at the heart of the procedural challenge to the council, documenting the violation of the engagement processes mandated by the policy. Here is a conversation between Christine and Teremoana, documenting the illegal nature of the consultation process:

Christine: When we found out that they had sent that notice that had the wrong date, they sent that to Veronica, the notice to say that they were going to take over the land, legal possession of the land, and when we found that out and we realized that that the notice said if you did not reply within 28 days, then that means you had given your consent. When you found that out, what did you think?

Teremoana: Well, we had not received any letters from Horizons at all and yet we pay our fees, we own a home, I am talking about myself, we own a home, we pay fees, so Horizons would have my name and my address to send a letter. So, yeah, I received nothing from them.

Christine: So how[sic] did they just send it to one person which was Veronica. Should they have sent [sic] to everybody?

Teremoana: Oh yeah. Yeah. Even in saying that, they said they sent it to Anne, well, she is [sic]secretary and is not a trustee of Te Ara o Rehua Ahu Trust, so it should have gone to the trustees of Te Ara o Rehua Ahu Trust.

Christine: And that information is easy to obtain. You just have to go online to [sic]Māori Land and all the names come up, who are trustees and who are not.

Teremoana: Yes. So, they did not do anything? No, you could see they did not do any homework concerning that, they just went in, and set that stop bank up, thinking they did it legally, but they were not. It was illegal.

The fact that the notice was sent with the wrong date and that the proper consultation process was not followed became the basis of the tangata whenua's challenge to the council's land takeover.

Christine, along with her Whānau, also placed her body on the land occupation, and at the same time organized and coordinated resources to support the occupation. Mohan placed his body on the occupation, joined by his partner, Debalina, and tauiwi members of the CARE team. Together, we spent a total of 517 h on the land occupation, preparing media materials, filming and editing them, building the social media site, studying land policies and engagement processes, developing media relations training, and engaging with the media. These embodied solidarities formed the infrastructure of the academic-community-activist relationship that resisted the settler-colonial state's top-down climate adaptation strategy carried out through land dispossession.

Voice infrastructure as a communication campaign

The advisory group discussions noted that the Crown's communication strategies circulated through settler colonial media upheld narratives that legitimized dispossession. It was therefore critical to disrupt this narrative. Here is Ngaire's view:

When Stuff, a reporter for Stuff…so he wrote an article that was slanted toward, well, it was not supporting us, put it that way[sic], made us out to be selfish for not giving up our land. And so, um, we talked about a way that we could try to well, intervene, hopefully, and change people's minds. But, at the very least, intervene, and put another narrative out there.

Here, Ngaire reflects on the culture-centered process of co-creating voice infrastructures that we had been working on in the advisory group to critically analyze the role of the settler colonial narratives in carrying out land theft. Noting that the mainstream settler colonial media would portray Māori occupying the land and resisting the stop bank as selfish, she expressed the importance of crafting an alternative narrative that foregrounds land theft. For the advisory group members, the role of the alternative narrative would be to highlight the communicative inversions, the turning of materiality on its head, carried out by the Crown by erasing legitimate Māori claims to land. The communicative inversion carried out through the trope of selfishness, which serves as the rhetorical device that legitimizes land grab framed under the rhetoric of climate adaptation, should be noted here. Also of note is the simultaneous erasure of Māori solutions to the flooding of the river.

The advisory group started re-working the script of the “What we say matters” videos they had been developing to document the erasure of voice that formed the basis of the land occupation. The stop bank as an example of climate colonialism offered an example and a context within which the advisory group could craft the message #WhatWeSayMatters. Their daily reflections on the erasure of voice that shaped their understanding of Māori struggles with health and wellbeing were reflected in the stop bank development project. Advisory group members noted how the project epitomized the violence of colonial development now being framed as climate adaptation and worked to erase Māori claims to land through a wide array of manipulative strategies. The advisory group, therefore, sought to enact and assert their voices as the basis for dismantling the erasure perpetuated by the colonial state. They started working on co-creating the script that narrated the process of land capture by the colonial state under the language of development, noted the ways in which the erasure of Māori voices formed the basis of the colonial development imaginary, and resisted the erasure through the voicing of Māori knowledge, rooted in relationship with the Oroua River. They developed the storyboard for the video narratives that formed the core infrastructure of the campaign and designed t-shirts to wear both in the land occupation and the videos (see Figure 2 for the t-shirt design). Both of us, Christine and Mohan, worked alongside CARE's creative team and technical producer to support the script that was being crafted by the advisory group, weaving together the videos and sounds into a narrative of resistance. The “What we say matters” campaign was released alongside the land occupation to give voice to Whānau and disrupt the narrative being perpetuated by the council. In solidarity with the occupation, Mohan worked with Christine on a culture-centered media relations training for Whānau, rooted in centering Whānau voices in making sense of and resisting colonial land occupation and narrating the breakdown of the consultation processes in the top-down intervention carried out by the council through arguments rooted in Indigenous voices.

Figure 2. T-shirts designed by the Feilding advisory group. Designed by the Feilding advisory group, 2019–2020. Center for Culture-centered Approach to Research and Evaluation (CARE).

Disrupting communicative erasures and communicative inversions

The settler colonial state deploys a wide array of communicative techniques for erasing Māori voices. It strategically uses communicative inversion, turning materiality on its head through communication, to erase the claims made by tangata whenua (a reference to Māori, the original inhabitants of Aotearoa New Zealand) to Indigenous land (Dutta and Hau, 2020; Mika et al., 2022). These communicative inversions and communicative erasures emerged as the sites of resistance, articulated to document the council's violations of consultation processes and the law. Christine, with her legal training, critically and closely read the documents used by the council to perpetuate land colonization. Her close reading of the documents revealed the erasures in the consultation process, the violations in the consultation processes, and the ways in which these violations perpetuated the erasure of Māori voices. These erasures became the basis for the whānau to challenge the decision made by the council, pointing to the failures in the Crown's consultation processes. These articulations shaped the communicative infrastructure of resistance that held up and supported the material occupation of the land and the co-creation of the communication resources in the form of the #WhatWeSayMatters campaign in support of the land occupation.

Here is Jason describing the role of the video as a voice infrastructure in articulating the narrative of the community:

I believe having our videos there, even though [sic] the media wanted to come in, I know Māori News went down there, but they had no permission. They were meant to wait. But anyway, they [referring to mainstream media] went down there past the land and spoke about the land on Te Kārere. But Chris [referring to the CARE video artist], he was really helpful in that matter of videoing us going on the land and also how the land looked in [sic]. Also, the feedback, different whanau speaking about their hurt and mamae [referring to pain], everything about Horizons taking over our land without permission.

Working with the CARE video artist and producer to narrate the pain felt over the violation of the land and the erasure of the consultation process enabled the community to control the narrative about the land occupation. This narrative control was critical to resisting the mainstream media narrative that deploys the trope of “selfishness” to legitimize neocolonial development projects that further perpetuate land alienation. Resisting the racist settler colonial framing of the community as a barrier to the public good, articulating the violation of the consultation processes and the erasure of community voices foregrounded the violence that continues to be carried out by the settler colonial state, reinterpreting the public good from the framework of indigeneity (The video campaign is here: https://www.facebook.com/whatwesaymatters?mibextid=LQQJ4d).

The videos, titled “Our whanau voices matter” brought whānau members together to document the Horizons project in continuity with the ongoing theft of Indigenous land. The voices of whānau members narrated the mamae and the trauma of loss, with video images depicting whanau members coming together peacefully to protest the development by occupation. The videos ended with whanau members standing by the marae, wearing the t-shirts they had designed, and saying “What we say matters.” The narrative showed how the development, framed as climate adaptation, continued the colonial processes of climate colonialism, dispossessing Indigenous communities of their land under the guise of climate-adaptive development. The video narratives constructed by the advisory group were incorporated into the mainstream media story (see https://www.stuff.co.nz/national/118928077/officials-halt-stopbank-construction-as-mori-land-owners-occupy-land), thus building a discursive register for previously silenced Māori voices on the “margins of the margins”.

Locating ourselves, centering the “margins of the margins”

Using the concept of communicative inequality outlined in the culture-centered approach (Dutta, 2008), we addressed the inequalities in the distribution of decision-making and voice resources within communities, decentering the concept of community in community participation. In the second author's earlier work on the CCA, the concept of community participation is problematized, depicting the ways in which the community becomes a monolithic category to be incorporated into top-down health interventions. The CCA notes that attention to the concept of communicative inequality lies at the center of conceptualizing communities as spaces for organizing structural change (Dutta, 2007). The concept of “margins of the margins”, which emerged from the CCA, offers a theoretical register for organizing culture as a site for radical organizing that challenges hegemonic structures that threaten human health and wellbeing (Dutta and Zapata, 2018; Dutta, 2020). Based on the theorizing of the “margins of the margins”, the CCA methodological framework turns to the key questions, “What voices are not present in this discursive space?” “How are these voices being erased?” and “How can we invite these voices in?” Dutta et al. (2019) describe the concept of “body on the line” as a communicative anchor for building practices of solidarity that work through sustained relationships with communities at the margins to advance structural transformation. They observe:

The process of cultural centering, therefore, is one of co-creating communicating infrastructures through solidarities with the subaltern margins. The three key methodological tools of the CCA, voice, reflexivity, and structural transformation (Dutta and Basu, 2008; Dutta, 2018b) are embedded in an embodiment, the physical placing of the academic body amid subaltern struggles for voice. Voice, and more specifically subaltern voice, emerges within this struggle as the site of articulation and structural transformation (Dutta, 2004a,b). While the interrogation of the politics embodied in hegemonic texts can offer an entry point into struggles for counter-hegemonic formations (Lupton, 1994; Dutta, 2005), we argue that such textual analysis of hegemony is only (can only be) a starting point for culture-centered interventions into health communication (Zoller and Dutta, 2009), with the actual work of structural transformation realized through questions of what it takes to co-create infrastructures for subaltern voices. Beyond the works of pedagogy in the classroom and the publication of findings in largely inaccessible journal articles or books, cultural centering is an invitation to place the body of the academic in solidarity with subaltern struggles in the public arena.

This study builds on the article by Dutta et al. (2019) to demonstrate the communicative process underlying the practice of solidarity in the CCA, which mobilizes alongside communities for structural transformation.

The concept of embodiment is materialized in the sustained presence of the academic, creative, and production team within the community, sustained by long-term relationships in the community. Community in this sense is not a monolithic category to be engaged in top-down participatory processes dictated by the settler-colonial structure; instead, it is a space for the struggle for voice, with the role of the health communication academic being to co-create voice infrastructures that sustain organizing for structural transformation. In the realm of indigeneity, the labor of co-creating infrastructures for subaltern voices exists in relation to land and struggles for land, a situating voice in relation to the land. The placing of the body of the academic in solidarity with Indigenous struggles in the CCA takes the form of generating resources for the voice through which Indigenous communities on the “margins of the margins” make claims and organize based on those to resist the settler-colonial land theft.

Communicative inequality and voice

The co-creation of the community advisory groups in the CCA is guided by theoretically-based critical reflections on the ongoing erasures within discursive spaces, turning to the co-creation of communicative resources and resources for culture-centered pedagogies of democratic participation among communities at the “margins of the margins” that have been erased from discursive spaces. Indigenous pedagogies of everyday democracy rooted in Tikanga (Māori cultural practices), as presented in this intervention, disrupt the whiteness of settler colonial democracy that works through the ongoing manipulation of participatory processes, through colonial techniques of divide and rule, and the erasure of Indigenous voices at the “margins of the margins.” These communities, themselves unequal and shaped by inequalities in the distribution of power, serve as the basis for culture-centered organizing at the racialized, classed, gendered “margins of the margins” within community spaces, taking the form of co-creating voice infrastructures.

In this instance, the voice infrastructures take the form of community advisory groups for communication within the community, and plural communicative materials, such as posters, placards, space design, video campaigns, social media pages, and media relations toolkits for interactions with different stakeholders. The community advisory groups as decision-making spaces and as spaces for articulation within the community, thus challenging communicative inequalities within communities and between communities, placing communicative resources in the hands of community members who negotiate everyday marginalization. The co-creation of voice infrastructures thus resists elite capture within the community and anchors the transformative agendas of social change among those within the community who are systematically erased through the exercise of power and control by the settler colonial state (Táíwò, 2022, wrote on the concept of elite capture). Referring to the videos as voice infrastructures, Vincent shared the following:

It [video] was really helpful in pushing it through. Then it made Horizons come to the forefront. If the cameraman [referring to the CARE video artist/media producer] had not been there all the whānau at the protest, they would not have done anything. They would have stayed there and kept digging and put up the big stop bank.

Thus, the videos are seen as working alongside the land occupation as a protest to stop the building of the stop bank. In line with earlier culture-centered scholarships on communicative sovereignty (Dutta and Thaker, 2019), we noted the critical role of community control over the communicative infrastructure in narrating the story of the community, in putting forth Indigenous frames for interpreting the land occupation that challenges the hegemonic point of view imposed by the whiteness of settler colonial media. The work of culture-centered interventions in building voice infrastructures on the “margins of the margins” addresses communicative inequality through the generation and circulation of a community-led frame that directly resists the settler colonial framing of the land occupation. The community-led frame is critical to shaping media and public discourses and sustaining public support for Indigenous movements. In this case, the community-led framing of the land occupation depicts the stop bank development as climate colonialism, disrupts the public good narrative, and demonstrates the erasure of Indigenous solutions that exist to flood prevention based on Indigenous knowledge. Moreover, the community-led frame articulated on the voice infrastructure depicts the nature of violence as land occupation and the simultaneous violation of the principles of Te Tiriti.

The land occupation as an intervention shows the agentic capacities of the “margins of the margins” in co-creating movements for structural transformation, working through the generation of knowledge, the intergenerational co-construction of Indigenous knowledge as a basis for solutions, and the role of legal knowledge in upholding the land occupation. In addition, the land occupation illustrates the organizing role of the CCA in mobilizing the “margins of the margins” to participate in resistance to colonial occupation through the co-creation of voice infrastructures within the community that shares the narrative constructed by the community in public discursive registers such as digital and traditional media. Through the land occupation, this study addresses the necessity of critical reading in settler colonial and postcolonial spaces, complicating the analysis of flows of power and control, and turning to the role of a culture-centered communicative pedagogy that strengthens the voices of communities at the intersectional margins.

Land occupation, decolonization, and health

Indigenous knowledge attends to the rootedness of health in the land (Dutta, 2004b; King et al., 2009; CARE Massey, 2019a,b; Hond et al., 2019; Jones, 2019; Moewaka Barnes and McCreanor, 2019; Thom and Grimes, 2022). The voices of advisory group members on the “margins of the margins” of the whānau center health in the land, powerfully articulating that the decolonizing struggle to secure Indigenous health has to begin and end with securing Indigenous land rights. Health is thus removed and dismantled from the colonial structures of whiteness that situate it amid parochial, micro-level individual behaviors, marked as targets for change through interventions. Instead, it is situated in relation to land, water, food, ecosystems, and climate change, offering registers for organizing against the twin forces of capitalism and colonialism. The question that often dictates the hegemonic health communication literature, including that circulated in its various performative forms in critical health communication scholarship, “How is this health?” and “How is this communication?” is disrupted by the turn to the question of land as an organizing feature of health.

This study contributes to the literature on health communication and structural determinants of health by conceptualizing health activism as participation in Indigenous communities' struggles for land reparations and in resistance to ongoing land theft. We suggest that addressing the structural determinants of health necessitates facing the structures and publicly opposing them. We build on the powerful call by Tuck and Yang (2012) that situates decolonization work within Indigenous struggles to take back land from the settler-colonial structure. We note here that as the frontiers of capitalism are shaped by aggressive and extensive extractive practices targeting and colonizing Indigenous lands, increasingly under the umbrella of climate colonialism (Mahony and Endfield, 2018), decolonization turns to the actual work of building voice infrastructures that support land struggles, participating in land struggles, and standing in solidarity with Indigenous struggles for land sovereignty, while simultaneously turning to Indigenous knowledge as the basis for building climate change solutions. As per Gayle's point of view, “We Māori have always known how to safeguard the climate, how to adapt to it, and how to sustain it. The Crown needs to learn how to listen to Māori in leading these solutions based on our knowledge that has been passed down through generations.”

The CCA, as depicted in this work, brings out the organizing role of academic-community solidarities in resisting settler-colonial land grabs through the labor of co-creating voice infrastructures in the form of community advisory groups. These solidarities, structures in the form of advisory group meetings, move beyond the usual forms of active academic research or academic activism, such as participating in a protest march or spending a few days in a movement, to the sustained and committed work of ongoing engagement in communities over an extended period of time, co-creating voice infrastructures and co-creating communicative interventions (such as the #WhatWeSayMatters campaign) through long-term partnerships. In this instance, the partnership with the community is in its fifth year and has grown since the land occupation to take the form of building community-owned food gardens, participating with the food in the local market, participating in the movement and protest march for the creation of Māori wards, developing community-led strategies to address violence and co-creating anti-racist interventions that challenge institutional and Crown racism. The co-creation of voice infrastructures on the Indigenous “margins of the margins” as the basis for communicative equality is at the heart of decolonization as a struggle for sovereignty, supporting and upholding material interventions such as land occupation to resist further land theft under the umbrella of climate colonialism. The community advisory group as a voice infrastructure serves as the basis for co-creating additional voice infrastructures (such as posters, videos, and social media pages) to build the communicative frames to narrate the land struggles and to build the discursive frames to resist the settler-colonial narrative of climate adaptation.

Body on the line: solidarity

Although existing analyses of culture-centered interventions often discuss structural transformation (Sastry et al., 2021), the processes of mobilization for structural transformation within culture-centered interventions have not been theorized and remain largely a black box. To address this gap, recent writings on the CCA that have emerged from the academic activist interventions carried out under the umbrella of CARE point to the role of putting the “body on the line” as the basis for mobilizing advocacy and activism for structural transformation (Dutta et al., 2019). This study responds to this gap in the literature on culture-centered interventions as activism that mobilizes for structural transformation by writing from within an intervention that emerged from a culture-centered process embedded in Indigenous-led land occupation. This process of embodied writing challenges the whiteness of hegemonic health communication writing that privileges data-based, outcome-based reports of behavior change interventions and erases the theorization of processes of organizing in communities for structural transformation. Moreover, the definitional parameters of what constitutes a health intervention are disrupted, noting that in the area of health disparities interventions, moving beyond the culturally sensitive behavior change framework (Dutta, 2007) calls for co-creating interventions that agitate against colonial-capitalist structures.

Constituted in the context of Indigenous struggles for land and communicative sovereignty, this study depicts the nature of academic organizing in solidarity with land struggles and shows what this solidarity looks like in the form of the work of building the voice infrastructures through embodied labor. The call for structural transformation which is a key theme in culture-centered scholarship is materialized through the embodied practice of activism. In this sense, through our ethnographic account of the land occupation and building on Dutta et al.'s (2019) article on “body on the line”, we depict what placing the “body on the line” looks like in the context of communication scholarship that calls for structural transformation, arguing that placing the body on the line for academic work to achieve structural transformation is a necessary and critical component. To place the body on the line is to be present with one's body amid the struggle, participating in solidarity with communities on the “margins of the margins” in the co-creation of communicative infrastructures for voice. Placing the identity of the center (CARE) in the land occupation and the co-creation of the communicative materials publicly confronts and challenges the settler colonial structure of the Crown. Both the body of the academic and the body of the academic space (in this case, the center, CARE) are placed in a position of confronting the structure and its power, talking back to it, embodying the risks connected to it, and speaking through these risks to build a decolonizing register. In this sense, health communication as decolonization is a materially embodied politics of resistance against the settler-colonial state.

Thus, the notion of academic-activism is conceptualized as resistance to the colonial-capitalist structures, challenging the performance of academic-activism as an institutionalizing framework (for instance, Morris and Hjort, 2012). We reject the notion of academic activism as a resource for institutionalizing disciplinary formations within academia, arguing that these forms of institutionalization are mechanisms for serving and perpetuating settler colonial power and control under the guise of activism while advancing the careers of individual academics within these structures. In other words, such co-optation, we note, serves the parochial, self-serving career goals of academics, posturing activism, and the radical performance of activism through shallow culturalist claims to further career interests. When understood from the relational needs of solidarity work with communities on the “margins of the margins”, the meaning of activism within academia turns to the essential work of organizing in resistance to the colonial-capitalist structure. The process of turning to culture as a site of organizing foregrounds the transformative capacity of culture to challenge the exploitative and extractive forces of colonialism-capitalism. The decolonizing register of academic-activism rewrites the accountability of academics by turning to communities on the “margins of the margins” as the spaces to which an academic is held accountable and to which they must turn to sustain communication for social change.

Conclusions

This study contributes to the current theorizing on CCA by empirically attending to the actual work of organizing against the settler colonial state, unpacking the black box of community organizing to map the role of voice infrastructures in the organizing process. Although culture-centered interventions organized under the umbrella of CARE (see Dutta et al., 2019) have challenged state-capitalist power as a basis for mobilizing for health at the margins, this is the first study to describe the process of building voice infrastructures from the context of an Indigenous land struggle in Aotearoa, New Zealand. We add to the article by Dutta et al. (2019) by showing the process of building voice infrastructures in communities on the “margins of the margins” of the settler- colonial state, demonstrating the role of community advisory groups and community-led communication materials such as posters, videos, and social media pages. We demonstrate how these voice infrastructures resist and disrupt the narrative frames constructed by the settler colonial state, and instead foreground Indigenous voices and knowledge.

This study thus contributes to both the CCA and health disparities literature by demonstrating what community organizing to co-create voice infrastructures looks like, and the role of voice as a basis for organizing in challenging the overarching structures of colonialism and capitalism that threaten human health and wellbeing in settler colonies. The nature of academic activism is written as solidarity, responding to the health needs of communities on the “margins of the margins”. Centering the voices on the “margins of the margins” anchors the organizing of the communication process for social change, conceptually framing the form of academic work as centered in land occupation and guided by the decision-making of communities on the “margins of the margins”. The sovereignty of Indigenous communities (Tino rangatiratanga) is enacted through communicative sovereignty, the ownership of communicative resources for voice by community members at the “margins of the margins”. Culture-centered scholarship that takes the form of academic-activism places itself in resistance to the extractive and exploitative forces of capitalism and colonialism. Future culture-centered scholarship should provide additional examples of the communicative processes of organizing communities on the “margins of the margins”.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Massey University. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The handling editor SK-G declared a past supervisee relationship with one of the authors MD.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^The names of the participants in this culture-cantered intervention have been changed to protect their identities.

2. ^The concept of “margins of the margins” addresses the intersectional forms of erasure within discursive spaces. In the context of indigeneity, it attends to the gendered, racialized, and classed contexts of colonization, noting that settler colonialism is experienced differently within communities, with community members at the racialized, classed margins bearing disproportionate greater burdens of dispossession.

References

Anthony, J. (2021). RMA Alternative ‘Revolutionary' But Risks Adding Complexity and Inefficiencies to Development. Stuff. Available online at:https://www.stuff.co.nz/business/industries/125596920/rma-alternative-revolutionary-but-risks-adding-complexity-and-inefficiencies-to-development (accessed May 12, 2023).

Asi, Y., Hammoudeh, W., Mills, D., Tanous, O., and Wispelwey, B. (2022). Reassembling the Pieces. Health Human Rights 24, 229–236.

Bargh, M. (2020). “Diverse Indigenous environmental identities: Māori resource management innovations,” in Routledge Handbook of Critical Indigenous Studies, eds B. Hokowhitu, A. Moreton-Robinson, L. Tuhiwai-Smith, C. Andersen, and S. Larkin (Routledge), 420–430.

Bargh, M., and Jones, C. (2020). “Māori interests and rights: Four sites at the frontier,” in Public Policy and Governance Frontiers in New Zealand, eds E. Berman and G. Karacoglu (Bingley: Emerald Publishing Limited), 71–89.

Bargh, M., and Van Wagner, E. (2019). Participation as exclusion: Māori engagement with the Crown Minerals Act 1991 block offer process. J. Hum. Rights Environ. 10, 118–139. doi: 10.4337/jhre.2019.01.06

Basu, A. (2008). “Subalternity and sex work: Re (scripting) contours of health communication in the realm of HIV/AIDS,” (doctoral dissertation). West Lafayette, IN: Purdue University.

Behrendt, L. (2010). Discovering Indigenous Lands: The Doctrine of Discovery in the English Colonies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bell, A. (2018). “A flawed Treaty partner: The New Zealand state, local government and the politics of recognition,” in The Neoliberal State, Recognition and Indigenous Rights: New Paternalism to New Imaginings, eds D. Howard-Wagner, M. Bargh, and I. Altamirano-Jiménez (Canberra: Australian National University Press), 77–92.

Bishop, J. (2020). Questionable Moves to Reform the Resource Management Act. Stuff. Available online at: https://www.stuff.co.nz/national/politics/opinion/122932829/questionable-moves-to-reform-the-resource-management-act (accessed May 12, 2023).

Boast, R. (2010a). “Appendix: Confiscation legislation in New Zealand,” in The Confiscation of Māori Land, eds R. Boast and R. S. Hill (Wellington: Victoria University Press), 263–266.

Boast, R. (2010b). “‘An expensive mistake': Law, courts and confiscation on the New Zealand colonial frontier,” in Raupatu: The Confiscation of Maori Land, eds R. Boast and R. S. Hill (Wellington: Victoria University Press), 145–168.

Brown, M. A., Peart, R., and Wright, M. (2016). Evaluating the Environmental Outcomes of the RMA. Environmental Defence Society.

CARE Massey (2019a). Public Talk with Dr Leonie Pihama: Decolonizing the Academe Through Activism tha t Dismantles Racism. [Video]. Facebook. Available online at: https://www.facebook.com/CAREMassey/videos/2294766290778815 (accessed May 12, 2023).

CARE Massey (2019b). Public Talk with Tāme Iti: Decolonising Ourselves, Indigenizing the University. [Video]. Facebook. Available online at: https://www.facebook.com/CAREMassey/videos/565881243898378/ (accessed May 12, 2023).

Cheyne, C. (2015). Changing urban governance in New Zealand: Public participation and democratic legitimacy in local authority planning and decision-making 1989–2014. Urban Policy Res. 33, 416–432. doi: 10.1080/08111146.2014.994740

Cheyne, C. M., and Tawhai, V. M. (2008). He wharemoa te rakau, ka mahue. Māori Engagement With Local Government: Knowledge, Experiences and Recommendations. Palmerston North: School of People Environment and Planning Massey University.

Coates, N. (2009). Joint-management agreements in New Zealand: Simply empty promises? J. South Pacific Law 13, 32–39.

Coromandel-Wander, H. (2013). “Koorero tuku iho: waahine Maaori: Voices from the embers of Rangiaowhia” (masters thesis). Palmerston North: Massey University.

Durie, E. T. (2012). “Ancestral laws of Māori: Continuities of land, people and history,” in Huia histories of Māori, eds D. Keenan (Huia Publishers),2–11.

Dutta, M., Pandi, A. R., Zapata, D., Mahtani, R., Falnikar, A., Tan, N., et al. (2019). Critical health communication method as embodied practice of resistance: Culturally centering structural transformation through struggle for voice. Front. Commun. 67, e00067. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2019.00067

Dutta, M. J. (2004a). The unheard voices of Santalis: Communicating about health from the margins of India. Commun. Theory 14, 237–263. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2885.2004.tb00313.x

Dutta, M. J. (2004b). Poverty, structural barriers, and health: a Santali narrative of health communication. Qual. Health Res. 14, 1107–1122. doi: 10.1177/1049732304267763

Dutta, M. J. (2005). Theory and practice in health communication campaigns: a critical interrogation. Health Commun. 18, 103–122. doi: 10.1207/s15327027hc1802_1

Dutta, M. J. (2007). Communicating about culture and health: Theorizing culture-centered and cultural sensitivity approaches. Commun. Theory 17, 304–328. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2885.2007.00297.x

Dutta, M. J. (2011). Communicating Social Change: Structure, Culture, and Agency. New York, NY: Routledge.

Dutta, M. J. (2012). Voices of Resistance: Communication and Social Change. West Lafayette, IN: Purdue University Press.

Dutta, M. J. (2014). A culture-centered approach to listening: voices of social change. Int. J. Listen. 28, 67–81. doi: 10.1080/10904018.2014.876266

Dutta, M. J. (2016). Cultural context, structural determinants, and global health inequities: the role of communication. Front. Commun. 1, e00005. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2016.00005

Dutta, M. J. (2018a). Culture-centered approach in addressing health disparities: Communication infrastructures for subaltern voices. Commun. Methods Meas. 12, 239–259. doi: 10.1080/19312458.2018.1453057

Dutta, M. J. (2018b). Culturally centering social change communication: subaltern critiques of, resistance to, and re-imagination of development. J. Multicult. Discour. 13, 87–104. doi: 10.1080/17447143.2018.1446440

Dutta, M. J. (2020). Communication, Culture and Social Change: Meaning, Co-option and Resistance. Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan.

Dutta, M. J., and Basu, A. (2008). Meanings of health: Interrogating structure and culture. Health Commun. 23, 560–572. doi: 10.1080/10410230802465266

Dutta, M. J., and Elers, S. (2020). Public relations, indigeneity and colonization: indigenous resistance as dialogic anchor. Public Relat. Rev. 46, 101852. doi: 10.1016/j.pubrev.2019.101852

Dutta, M. J., and Hau, N. (2020). “Voice infrastructures and alternative imaginaries: Indigenous social movements against neocolonial extraction,” in The Rhetoric of Social Movements, ed N. Crick (New York, NY: Routledge), 254–268.

Dutta, M. J., and Pal, M. (2020). Theorizing from the global south: Dismantling, resisting, and transforming communication theory. Commun. Theory 30, 349–369. doi: 10.1093/ct/qtaa010

Dutta, M. J., and Thaker, J. (2019). ‘Communication sovereignty' as resistance: strategies adopted by women farmers amid the agrarian crisis in India. J. Appl. Commun. Res. 47, 24–46. doi: 10.1080/00909882.2018.1547917

Dutta, M. J., and Zapata, D. B. (eds.), (2018). Communicating for Social Change: Meaning, Power, and Resistance. Singapore: Springer.

Ellis, M. (2021). RMA and Water Reforms: ‘Crunch Time' for Māori for Critical Reforms. Stuff. Available online at: https://www.stuff.co.nz/national/300309369/rma-and-water-reforms-crunch-time-for-mori-for-critical-reforms (accessed May 12, 2023).

Forster, M. (2014). Indigeneity and trends in recognizing Māori environmental interests in Aotearoa New Zealand. National. Ethnic Polit. 20, 63–78. doi: 10.1080/13537113.2014.879765

Ganesh, S., Dutta, M. J., and Ngā, H. (2021). “Building communities,” in Handbook of Management Communication, eds F. Cooren and P. Stucheli-Herlach (Boston: De Gruyter Mouton), 427–442.

Gilling, B. D. (2020). “Raupatu: The punitive confiscation of Māori land in the 1860s,” in Land and Freedom: Law, Property Rights and the British Diaspora, eds A. Buck, J. McLaren, and N. Wright (New York, NY: Taylor and Francis), 117–134.

Goldtooth, T. B., and (Awanyankapi, M.) (2010). The state of Indigenous America series: Earth Mother, pinons, and apple pie. Wicazo Sa Review 25, 11–28. doi: 10.1353/wic.2010.0006

Hancock, F., Lee-Morgan, J., Newton, P., and McCreanor, T. (2020). The case of Ihumātao: Interrogating competing corporate and Indigenous visions of the future. New Zealand Sociol. 35, 15–46.

Harmsworth, G., Barclay-Kerr, K., and Reedy, T. M. (2002). Maori sustainable development in the 21st century: The importance of Maori values, strategic planning and information systems. He Puna Korero J. Maori Pac. Dev. 3, 40–68.

Hayward, J. (1999). Local government and Maori: talking treaty? Polit. Sci. 50, 182−194. doi: 10.1177/003231879905000204

Hond, R., Ratima, M., and Edwards, W. (2019). The role of Māori community gardens in health promotion: a land-based community development response by Tangata Whenua, people of their land. Global Health Promot. 26, 44–53. doi: 10.1177/1757975919831603

Irwin, K. (1994). Māori research methods and processes: an exploration. J. South Pacific Cult. Stud. 28, 25–43.

Jackson, M. (1993). “Land loss and the treaty of Waitangi,” in Te ao mārama: Regaining Aotearoa. Māori Writers Speak Out, eds W. Ihimaera, H. Williams, R. Ramsden, and D. Long (Reed Books), 70–78.

Jacobson, C., Matunga, H., Ross, H., and Carter, R. (2016). Mainstreaming Indigenous perspectives: 25 years of New Zealand's resource management act. Austral. J. Environ. Manag. 23, 1259201. doi: 10.1080/14486563.2016.1259201

Jones, R. (2019). Climate change and Indigenous health promotion. Global Health Promot. 26, 73–81. doi: 10.1177/1757975919829713

King, M., Smith, A., and Gracey, M. (2009). Indigenous health part 2: the underlying causes of the health gap. Lancet 374, 76–85. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60827-8

LGNZ (2021). Local Government in NZ. Available online at: https://www.lgnz.co.nz/local-government-in-nz/ (accessed September 25, 2021).

Local Government New Zealand (2011). Local Authorities and Māori: Case Studies of Local Arrangements. Available online at: https://www.lgnz.co.nz/assets/Uploads/ea0b5e6be8/Local-Authorities-and-Maori.pdf (accessed May 12, 2023).

Local Government New Zealand (2017). Council-Māori Participation Arrangements: Information for Councils and Māori When Considering Their Arrangements to Engage and Work With Each Other. Available online at: https://www.lgnz.co.nz/assets/Uploads/ea0b5e6be8/Local-Authorities-and-Maori.pdf (accessed May 12, 2023).

Lowry, A., and Simon-Kumar, R. (2017). The paradoxes of Māori-state inclusion: the case study of the Ohiwa Harbour Strategy. Polit. Sci. 69, 195–213. doi: 10.1080/00323187.2017.1383855

Lupton, D. (1994). Toward the development of critical health communication praxis. Health Commun. 6, 55–67. doi: 10.1207/s15327027hc0601_4

Mahony, M., and Endfield, G. (2018). Climate and colonialism. Wiley Interdiscipl. Rev. Clim. Change 9, e510. doi: 10.1002/wcc.510

McCormack, F. (2011). Levels of indigeneity: the Maori and neoliberalism. J. Royal Anthropol. Inst. 17, 281–300. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9655.2011.01680.x

Mika, J. P., Dell, K., Elers, C., Dutta, M., and Tong, Q. (2022). Indigenous environmental defenders in Aotearoa New Zealand: Ihumātao and Oroua River. AlterNative Int. J. Indig. Peoples 18, 277–289. doi: 10.1177/11771801221083164

Mikaere, A. (2011). Colonising Myths Māori Realities: He rukuruku whakaaro. Wellington: Huia Publishers.

Ministry of Health (2015). Tatau kahukura: Māori Health Chart Book 2015, 3rd Edn. Ministry of Health.

Moewaka Barnes, H., and McCreanor, T. (2019). Colonisation, hauora and whenua in Aotearoa. J. Royal Soc. New Zeal. 49, 19–33. doi: 10.1080/03036758.2019.1668439

Morris, M., and Hjort, M. (eds.), (2012). Creativity and Academic Activism: Instituting Cultural Studies (Vol. 1). Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

Mutu, M. (2017). “Māori of New Zealand,” in Native Nations: The Survival of Fourth World Peoples. 2nd Edn, eds S. Neely (JCharlton Publishing), 87–113.

Nepe, T. M. (1991). “Te Toi Huarewa Tipuna: Kaupapa Māori, an educational intervention system,” (MA Education). Auckland: University of Auckland.

Norton-Smith, K., Lynn, K., Chief, K., Cozzetto, K., Donatuto, J., Redsteer, M. H., et al. (2016). Climate Change and Indigenous Peoples: A Synthesis of Current Impacts and Experiences. United States Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station.

O'Bryan, K. (2019). Indigenous Rights and Water Resource Management: Not Just Another Stakeholder. New York, NY: Routledge, Taylor and Francis Group.

Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment (1998). Kaitiakitanga and Local Government: Tangata Whenua Participation in Environmental Management. Available online at: https://www.pce.parliament.nz/media/pdfs/kai.pdf (accessed May 12, 2023).

Pihama, L. (1993). “Tungia te ururua, kia tupu whakaritorito te tupu o te harakeke: A critical analysis of parents as first teachers,” (MA). University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand

Pihama, L., Cram, F., and Walker, S. (2002). Creating methodological space: a literature review of Kaupapa Maori research. Can. J. Native Educ. 26, 30–43.

Reid, P., Cormack, D., and Paine, S. J. (2019). Colonial histories, racism and health—The experience of Māori and Indigenous peoples. Public Health 172, 119–124. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2019.03.027

Rennie, H., Thomson, J., and Tutua-Nathan, T. (2000). Factors Facilitating and Inhibiting Section 33 Transfers to Iwi. Department of Geography, University of Waikato and Eclectic Energy.