- 1Mercatorum University, Rome, Italy

- 2Department of Computer, Control and Management Engineering, Sapienza University of Rome, Rome, Italy

Introduction: The purpose of this paper is to investigate how the culture of a nation influences online corporate communication, focusing on the assessment of the culturability of business websites. Although the Internet constitutes a global phenomenon, cultural filters influence its use at the local level, ultimately determining a more or less favorable attitude toward a given website. Understanding and analysing the cultural adaptation of online communication is crucial as it has the potential to greatly influence how customers perceive and respond to the graphic and content elements.

Methods: Building upon Hofestede's and Hall's theories, a content analysis technique was used to code the cultural markers and new indicators have been created to allow the association of the graphic elements and the contents of the websites with the cultural characteristics. The countries chosen as case studies are India and Australia, which present significant cultural differences and allow highlighting of the practical implications deriving from the cultural adaptation of the website design.

Results: The results of this paper show that the company websites analyzed are designed to incorporate the cultural nuances of the target country. In particular, on the Australian websites, there is a greater frequency of cultural markers referring to individualism, masculinity, and uncertainty avoidance compared to Indian ones. On the contrary, Indian websites show more cultural markers referring to power distance, high context, and polychronic characteristics than Australian ones. This paper overcomes the qualitative approaches of the previous literature, developing new indicators for website analysis and providing a quantitative comparison with Hofstede and Hall frameworks.

Discussion: This work provides a guideline for companies, analysts, and the different professionals involved in online communication and web design. More specifically, they have to be aware of the cultural challenges when they operate outside the national boundaries, by designing a culturally usable website in one of the countries chosen for this study.

1. Introduction

The culture of a nation conditions the cognitive capacity of individuals: to be correctly interpreted a message must respect the cultural canons of its receiver. Although the Internet constitutes a global phenomenon, cultural filters influence its use at the local level, ultimately determining a more or less favorable attitude toward a given website (Moura et al., 2016).

At the dawn of internet usage, website design was simple because first-generation sites, being primarily text-based, needed a mere translation to be intercultural.

However, the development of Flash and the implementation of multimedia content (audio and videos) created new potentialities for the web and caused new standards for efficient and effective web communication within a cross-cultural context. Nowadays, a website is not a mere collection of texts but a collection of images, multimedia, interactive functions, animated graphics, and sounds.

To improve usability and user experience, a multinational company must be aware that the website should not be a mere linguistic translation but must be designed to reflect the cultural characteristics of the target country. In fact, as well as in paper and television advertising, now outclassed by that on the internet, the cultural adaptation of online communication can influence customer perceptions and preferences (Okazaki, 2004; Rhoads, 2019; Capece and Di Pillo, 2021).

Therefore, companies must develop a corporate web design that matches the values and behaviors of the cultures to which they are directed.

To address a specific market, designers need to know about its preferences, likes, and dislikes, so they can provide cultural metaphors, and real world representation of the user interface objects, and also eliminates any culturally offensive material (Al-Badi and Mayhew, 2010).

In this paper, the findings of anthropologists Hofstede (1980, 2001) and Hall (1989) on cultures provide the basis for the analysis of websites. Their findings include a set of categories into which the cultures are systematized.

The goal of our study is to investigate how the culture of a nation influences web corporate communication, by analyzing the relationships between country culture (systematized by Hofstede and Hall theories) and the website characteristics of companies belonging to that country. Building upon Hofstede's and Hall's frameworks, a content analysis technique was used to code the cultural markers and new indicators have been created to allow the association of the graphic and content elements of the websites with the cultural characteristics. The calculation of new indicators allowed a discussion based on measurable parameters instead of qualitative assessment, largely used in the previous literature (Barber and Badre, 1998; Marcus and Gould, 2000; Würtz, 2005). The countries chosen as case studies are India and Australia, which present significant cultural differences and allow highlighting of the practical implications deriving from the cultural adaptation of the website design.

India and Australia, despite being at two opposite cultural poles, have long-standing commercial relationships, dating back to the eighteenth century when India played a central role in the supply of colonies. Currently, scholars and policy makers assert that India and Australia are “natural allies” (Sharma, 2016); the Indian Prime Minister, Narendra Modi, on his recent visit to Australia claimed that: “there is a natural partnership arising from shared interests and strategic maritime location” society. At the same time, the culture and the set of values of the two countries are opposed; their colonial experiences have been very different and this has led to the development of two liberal countries with distinct traditions, interests, and values (Chacko and Davis, 2017).

The first phase of our research provides a content analysis of a sample of 500 corporate websites of Indian listed companies and as many Australian listed companies. The objective is to investigate the design and content elements of the websites mirroring the presence of cultural markers.

The second phase of the research is pursued through the creation of seven new cultural indicators for the website analysis, starting from the Hofstede and Hall frameworks. Compared to the main literature on the subject, the current work develops a quantitative approach to adapt Hofstede's cultural dimensions to the features and content of website design. Moreover, the study provides a quantification of Hall's cultural framework to the context of web communication.

2. Theoretical background and hypotheses

2.1. Hofstede's framework

According to Hofstede: “culture works as the mental software for humans, playing a significant role in forming their ways of thinking, feeling, and acting.” Determining the influence of culture on behavior is not simple, as culture is a complex construct that is difficult to accurately measure. To simplify its operationalization and to allow at least some aspects of culture to be more easily applied, researchers have suggested using cultural indices, among which the most important and used are those of Hofstede (Ng et al., 2007). Hofstede's cultural model was developed from a large-scale comparison of national cultures, and it allows us to determine the similarities and differences based on some cultural factors, by reducing the complexity of culture through its split into significant dimensions. Although this model has some criticisms, such as the methodological assumptions (the hypothesis that the national population is a homogeneous whole) and the sample and time-dependent implications, it is generally considered the most comprehensive framework of national cultures and is still one of the most used in cross-cultural communication research (Gevorgyan and Manucharova, 2009).

The Hofstede model includes five dimensions through which to measure national cultures, as described in the following. These dimensions can be measured through five indicators, ranging from 0 to 100.

2.1.1. Power distance

This dimension expresses the degree to which there are social inequalities among people. According to Hofstede's theory: “People in societies exhibiting with a large degree of power distance to the hierarchical order in which everybody has a place and which needs no further justification. In societies with low power distance, people strive to equalize the distribution of power and demand.”

From a managerial point of view, in a culture with a high PDI, hierarchical bureaucracies, strong leaders, and great respect for authority are preferred. The subordinates tend to execute the instructions assigned to them without objections.

India has a PDI equal to 77, among the highest in the world (global average equal to 56.5). This value indicates a great level of acceptance of inequalities regarding power and social wellbeing (Kulkarni et al., 2012). In fact, 33% of the total wealth of the country is owned by 10% of the population. In Indian society, equality and opportunities for all are hard-to-reach goals, probably because of the ancient caste system. It must also be highlighted the importance of religion and ancient scriptures in modern-day management in India.

For Australia, the PDI is particularly lower than that of India, with a value of 36; therefore, it is possible to find greater social equality and greater intellectual independence.

These values of PDI should also be reflected in corporate web communication. Therefore, the following hypothesis is formulated.

H. 1: Indian websites will show a greater frequency of cultural markers related to PDI than Australian ones.

2.1.2. Individualism

Hofstede defines individualism as “a preference for a loosely-knit social framework in which individuals are expected to take care of only themselves and their immediate families [...] Its opposite, collectivism, represents a preference for a tightly-knit framework in society in which individuals can expect their relatives or members of a particular in-group to look after them in exchange for unquestioning loyalty.”

India has a value of 48 and, therefore, is a collectivist country. In Indian society, the family plays an important role and is traditionally formed by numerous relatives who live under one roof (Kulkarni et al., 2012). Furthermore, even in the business world, top manager positions are reserved for members of the family who own the company.

Australia has an index of 90, the second highest in the world after the US. As a consequence, in Australian society individual interest prevails over that of the group, interpersonal bonds are weak and everyone takes care of himself and his closest family members.

In the field of web marketing, it is expected that on Indian websites there will be a greater presence of characteristics related to collectivism than on Australian ones. For this reason, the following hypothesis is formulated.

H. 2: Indian websites will present a greater frequency of cultural markers related to collectivism than Australian ones.

2.1.3. Masculinity

According to Hofstede's theory: “the masculinity side of this dimension represents a preference in society for achievement, heroism, assertiveness, and material rewards for success. Society is more competitive. Its opposite, femininity, stands for a preference for cooperation, modesty, caring for the weak, and quality of life. Society at large is more consensus-oriented.”

In the managerial field, male culture emphasizes status, while feminine culture emphasizes human relationships and quality of life.

India has a value of MAS equal to 56, which indicates a tendency toward greater masculinity. The female position within Indian society has deteriorated considerably since the Middle Ages, due to the rituals such as Sati, Jauhar, Purdah, and Devadasi. Furthermore, the tradition of child brides, outlawed since 1860 by the British, is still an effective practice and in certain regions commonly used.

As for masculinity, Australia has a high index (61). This implies that individuals act based on male stereotypical traits (success, aggressiveness, result, and dominance) and that, in the workplace, they are oriented toward success, earnings, and career advancement.

As this index is higher for Australia, we expect to identify more masculinity-related elements on Australian websites than on Indian ones. Consequently, we intend to verify the following hypothesis.

H. 3: Indian websites will exhibit lesser cultural markers related to male gender characteristics than Australian ones.

2.1.4. Uncertainty avoidance

Hofstede states that: “the uncertainty avoidance dimension expresses the degree to which the members of a society feel uncomfortable with uncertainty and ambiguity […] Countries exhibiting strong UAI maintain rigid codes of belief and behavior, and are intolerant of unorthodox behavior and ideas. Weak UAI societies maintain a more relaxed attitude in which practice counts more than principles.”

From a managerial point of view, in countries with high risk aversion, the standardization and safety of the workplace are emphasized.

India has a low index of UAI (40). This means that India is a tolerant country and is inclined toward change and innovation.

The Australian culture has a UAI index equal to 51. Despite this value being slightly above average, Australia is categorized, like most Western countries, as risk-averse. People belonging to this culture do not like risky or unclear situations.

From the web communication point of view, it is assumed that on Indian websites there are fewer elements regarding risk aversion compared to Australian ones. Consequently, the following hypothesis is formulated.

H. 4: Indian websites will have a lower frequency of cultural markers related to risk aversion than Australian ones.

2.1.5. Long term orientation

Hofstede affirms that: “Every society has to maintain some links with its own past while dealing with the challenges of the present and the future. Societies prioritize these two existential goals differently. Societies that score low on this dimension, for example, prefer to maintain time-honored traditions and norms while viewing societal change with suspicion. Those with a culture which scores high, on the other hand, take a more pragmatic approach: they encourage thrift and efforts in modern education as a way to prepare for the future.” This dimension shows a cultural trend focusing on the future by persisting in thriftiness (Jiacheng et al., 2010).

With a score of 61, against the global average of 48, India is a country with a slightly high LTO. This value turns out to be appropriate to a persevering and thrifty culture, within which religion and ancient scriptures are important in modern-day management (Laleman et al., 2015; Pereira and Malik, 2015).

The LTO dimension in Australia has a low value (31), which represents a strong respect for the traditions and the fulfillment of social obligations.

Within web marketing, Indian websites are supposed to have a greater presence of cultural markers related to LTO than Australian ones, as described in the following hypothesis.

H. 5: Indian websites will show a greater frequency of cultural markers related to long-term orientation compared to the Australian ones.

2.2. Hall's framework

Hall, in his research, has explored above all the micro-cultural, and often hidden, dimensions of communicative acts. According to Hall, behavior is unconsciously conditioned by informal rules concerning the perception of time and space, or the communication context, thus bringing to light non-verbal communication. Even Hall's theory is not free from criticism, as considered a merely qualitative study, showing limitations in the contextual model (Cardon, 2008).

Hall develops the concepts of high and low context cultures. In low context cultures, the message is communicated almost entirely by words and therefore needs to be explicit. Written instructions, contracts, and documents have more value in negotiations. In high context cultures, communication is largely implicit, meaning that context and relationships are more important than the actual words, and therefore, very few words are necessary.

In Western countries, there is usually a low-context communication style, in which the messages are short and clear, giving greater importance to the content and the spoken words. In this manner, communication is more direct, complete, and well defined. On the contrary, in Asian countries, there is a high-context communication style, in which non-verbal forms are as important as the use of metaphors, silences, and gestures.

Hall proposes a further classification of cultures based on their conception of time. In this way, he identifies two models of relationship with time very different from each other, often in conflict among them: monochronic time (typical of low context cultures) and polychronic time (typical of high context cultures). Monochronic time characterizes Western and Northern European cultures that tend to focus on one activity at a time, attaching great importance to the development of plans and their execution. Those who have this approach consider time as a resource, which can therefore be spared, organized, and spent. Polychronic time, instead, represents the typical approach of Middle Eastern and Latin cultures. Punctuality is less important, and flexibility and distractions from the objective characterize this type of culture. Moreover, program changes are frequent and several activities are often carried out at the same time.

Indian culture is defined as strongly high context, in fact, the use of long sentences and ambiguous expressions with more meanings often leads to misunderstandings between Indians and people coming from low context western cultures.

For Indians, the purpose of communication is to maintain harmony and forge interpersonal relationships, not that of exchanging accurate information (Lewis, 2010).

In a high-context culture, like the Indian one, the meaning of the message is not in the content of words, but in everything around it. Furthermore, a polychronic perception of time is attributed to high-context culture. In this culture, people never plan work but tend to start more operations at a time at the expense of efficiency.

Unlike India, Australia is considered a country with a low-context culture, in which the meaning of the message depends on the content and the words utilized, not on the context. The concept of time in this type of culture is called monochronic, so there will be a certain propensity to optimize time and to carry out personal tasks one at a time.

Hall's theory should also be reflected in the marketing strategies of companies that should adapt their websites concerning the cultural characteristics of the target country. It will thus be conceivable that on Indian websites there will be a greater presence of characteristics inherent to the high context culture and a polychronic conception of time compared to the Australian ones. Therefore, the following hypotheses are formulated.

H. 6: Indian websites will show a greater frequency of cultural markers related to high-context communication compared to the Australian ones.

H. 7: Indian websites will show a greater frequency of cultural markers related to a polychronic conception of time compared to the Australian ones.

3. Cultural influences on website design

Cultural differences have been well addressed in several web communication areas, such as e-commerce (Luo et al., 2014; Hallikainen and Laukkanen, 2018), social networks (Gong et al., 2014; Prakash and Majumdar, 2021), online reviews (Lamb et al., 2020), and also in the adoption of web 2.0 technologies (Ribiere et al., 2010; Barron and Schneckenberg, 2012). As regards the influence of culture in the design of a website, many authors agree on the principle: “Think globally, act locally,” suggesting that website designers and developers accommodate cultural preferences in websites (Alexander et al., 2017; Wasowicz-Zaborek, 2018). According to Gommans et al. (2001): “website has to be designed for a targeted customer segment […] Local adaptation should be based on a complete understanding of a customer group's culture.” The web needs user interface features fitting for culturally diverse audiences (Marcus and Gould, 2000; Luna et al., 2002; Burgmann et al., 2006; Cyr et al., 2010; Robbins and Stylianou, 2010; Shobeiri et al., 2018). Ackerman (2002) underlines the importance of the development of user interfaces and information design tools based on cultural differences. Barber and Badre (1998) refer to the merging of culture and usability as “culturability” when cultural characteristics are taken into consideration in website design because they influence how a user interacts with the site. In the field of web communication, the elements representing the culture of a country are defined as cultural markers (Barber and Badre, 1998). They can be expressed through the design of a website, adequately choosing all the elements composing it. For instance, the collectivism dimension is expressed through the depiction of community relations, chat rooms, newsletters, family themes, pictures and symbols of national identity, and loyalty programs. These characteristics highlight how collectivist societies consider the community-based social order (Hofstede, 1980), group wellbeing and the preservation of the welfare of others (Gudykunst, 2004) are prominent factors. In collectivist societies, the emotional dependence by individuals on organizations and society (Hofstede, 1980) is predominant concerning other factors; as a consequence people need forums, chats, and other similar tools to share their concerns, points of view, and emotions. In collectivist cultures, the self-in-relation-to-others and the continuous search for group consensus play an important role. These cultures are characterized by the nurturance attitude in which members of a group provide each other with support and empathy (Pollay, 1983), and by a deep bond with the “we theme” and family ties (Trompenaars and Hampden-Turner, 2011).

As regards the uncertainty avoidance index, this dimension is expressed through customer service support, customer testimonials, guided navigation, traditional symbols, local lexicon, free trials and downloads, and toll-free numbers. These websites' characteristics are based on the evidence that in uncertainty avoidance cultures individuals need to feel at ease and, as a consequence, they avoid ambiguous situations and search for advice, security, and guidance (Gudykunst, 2004). High uncertainty avoidance societies are also “tight societies” in which conservatism and traditional beliefs are taken into great consideration (Hofstede, 1980). Consequently, past customs and conventions are severely respected, and long-term traditions are venerated (Pollay, 1983).

As regards the masculinity index, this dimension is expressed through games, quizzes, and other fun entertainments on the websites. Another important characteristic that distinguishes masculine from feminine cultures is the extensive use of superlatives words in sentences such as “we are the number one,” “the top company,” “the leader,” just to give some examples. In masculine cultures the different roles of genders are underlined: women are depicted as wives and mothers, with more modest and humble work positions, while for men the strength, the powerful personality, the manual or prestigious works and the depiction as “machos” are emphasized.

The power distance dimension is represented within the website design through the presence of information on corporate hierarchy (for instance the ranks of company people and the organizational chart) and on titles of the important people in the company. Moreover, this dimension is revealed through the vision statement and pictures of the CEO and company executives. The mention of the prestige and fame of the company also expresses the power distance, as well as the quality information and the mentions of awards won (Singh and Baack, 2004).

In countries characterized by short-term orientation, web indicators include the use of a site map, index page, and the availability of a search engine. These factors help to save time and achieve results. The presence of a FAQ section and the possibility to communicate online with company experts in real-time also reveals a short-term orientation. Vice versa, the presence of a vision statement on the corporate website is an indication of a long-term orientation. Indeed, the vision statement by definition expresses the long-term orientation of the company (Robbins and Stylianou, 2010).

The high context culture uses non-textual forms of communication, privileging the use of images and symbolisms. Within a website design, this type of culture is formalized using multimedia effects, animations, and other non-textual supports. On the contrary, websites of low-context cultures are characterized by rich text content with fewer occurrences of animations, heavy images, and other effects, to ensure that these websites are practical and direct sources of information (Würtz, 2005).

As for polychronic culture, to the best of our knowledge, no study in the literature has considered this aspect of website design. In this article, we assume that polychronism within the website design is operationalized by the presence of animations and complex menus. Navigation is more parallel than linear and there is no site map. Vice versa, monochronic cultures emphasize linear navigation with few sidebars and constant opening in the same browser window.

4. Materials and methods

4.1. Content analysis

In the context of communication research, the classic definition by Berelson (1952) is the following: “a quantitative, systematic, and objective technique for describing the manifest content of communications.” Thanks to this technique it is possible to measure a concept (for example the dimension of Hofstede's individualism) through the variables that operationalize that concept (e.g., the number of occurrences of the CEO image). Therefore, this broadly used and reputable research tool is very suitable for analyzing graphic and content elements of a corporate website (Weare and Lin, 2000; Herring, 2009; Sjøvaag and Stavelin, 2012). Moreover, content analysis allows for studying cultures, values, and behavioral attitudes underlying communication contents (Cheng and Schweitzer, 1996; Engelen and Brettel, 2011; Adnan et al., 2018). Thus, it allows for comparisons across national borders and can provide scientific rigor to the empirical analysis (Kassarjian, 1977; Singh and Matsuo, 2004; Neuendorf, 2017).

The companies chosen for this work have been selected from those listed on the National Stock Exchange of India for the Indian sample and those listed on the National Stock Exchange of Australia for the Australian one. A total of 1,000 corporate websites (500 Indian companies and as many Australian ones) were analyzed. All the websites were coded by two native English speakers, who do not know each other. The coders were thoroughly trained by reading and discussing the coding scheme with the researchers. Further reliability checks were performed by a third coder, a native English with experience of the Indian culture. Comparing the categorization carried out by each coder, an average correspondence of 74% was found. When differences were found between the coders, the cultural markers were reviewed according to the majority rule (Tinsley and Weiss, 1975).

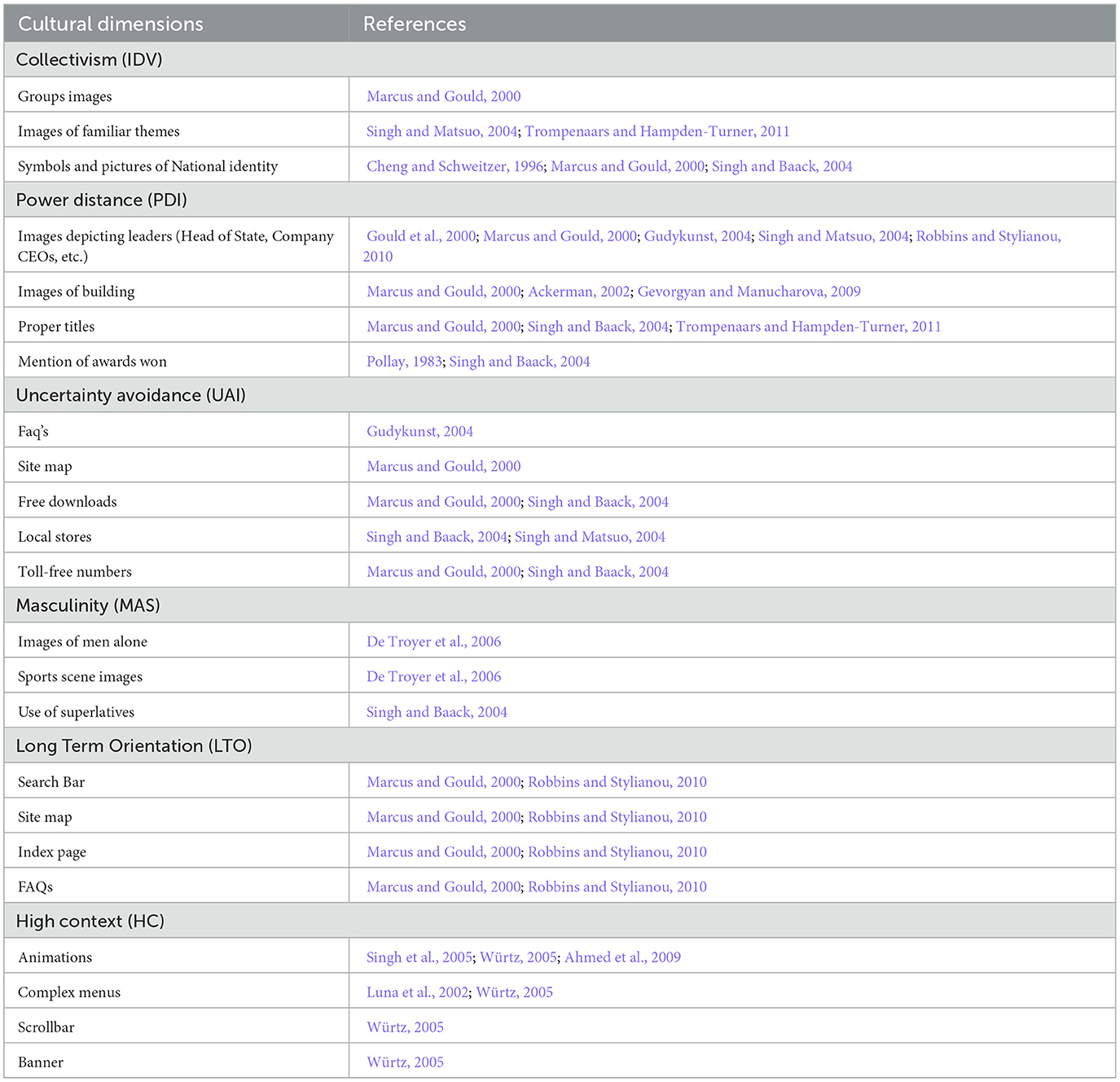

The coders assessed, according to their judgments and for each web page, the frequency of occurrence of the cultural markers listed in Table 1. The validity of coding has been tested by means of inter-coder reliability by using the ReCal3® tool, through the Krippendorff's α (Krippendorff, 2004, 2018), which is the most suitable index for measuring the reliability of coding. In our study, the overall inter-coder reliability is 81% which is acceptable based on the main literature (Lombard et al., 2002; Krippendorff, 2018).

The overall inter-coder reliability of IDV cultural makers is 91% (Indian websites) and 89% (Australian websites); the overall reliability of UAI cultural makers is 87% percent (Indian websites) and 93% (Australian websites); the overall reliability of PD cultural makers is 85% (Indian websites) and 83% (Australian websites); the inter-coder reliability of MAS cultural makers is 88% (Indian websites) and 90% (Australian websites). Finally, the overall reliability of HC cultural makers is 86% (Indian websites) and 84% (Australian websites); the inter-coder reliability of POL cultural makers is 87% (Indian websites) and 83% (Australian websites).

4.2. Cultural indicators for website analysis

According to the main literature, we have selected the most representative elements of the websites regarding the cultural characteristics of Hofstede and Hall (see Table 1). Subsequently, new indicators have been created to allow the association of the graphic elements and the contents of the websites with the cultural characteristics considered by Hofstede and Hall. The functions used to calculate the indicators are shown below.

4.2.1. Power distance index

Where: L = Leaders (% of sites that represent CEOs and top management); MB = Monumental Building (% of sites that represent Monumental Building); TP = Titles and Prizes (% of sites that present titles and prizes).

4.2.2. Individualism

Where: II = Individual Images (calculated as the ratio of individual images to the total of images depicting people). For this indicator, we considered only one element because it is the most representative of the cultural marker of individualism.

4.2.3. Masculinity

Where: MI = Men Images (calculated as the ratio of images of men compared to the total images of people). Also for this indicator, we considered only one element because it is the most representative of the cultural marker of masculinity.

4.2.4. Uncertainty avoidance index

Where: H = help in customer experience (the sum of the percentage of the sites that show the contacts of the local dealers, the toll-free number, and the FAQs); SM = Site Map (% of sites that have the site map); FD = Free Downloads (% of sites that give the possibility to carry out free downloads).

4.2.5. Long-term orientation

Where: SM = Site Map (% of sites that have the site map); SB = Search Bar (% of sites that have the search bar); IP = Index page (% of sites that have the index page); FAQ = FAQs (% of sites that have the FAQs).

4.2.6. High context

Where: CM = Complex Menus (% of sites that have complex menus); A = Animations (% of sites that have animations regarding sounds, videos, texts, and images); B = Banner (% of sites that have one or more banners); S = Scrollbar (% of sites that have scrollbars).

4.2.7. Policronism

Where: A = Animations (% of sites that have animations regarding sounds, videos, texts, and images); NSM = Absence of Site Map (% of sites that do not have site map).

5. Results

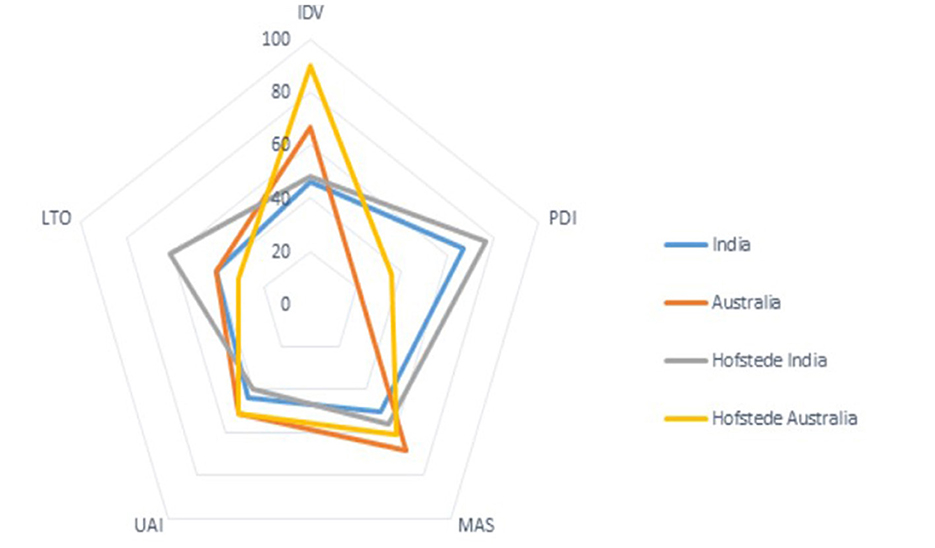

Based on our model (described in section Cultural indicators for website analysis), we calculate the new Hofstede values for India and Australia, and we compare them with the original ones (see Figure 1). The values are almost the same for the IDV of India, the UAI, and the MAS of both countries. Although for the other values there is not a strict correspondence with the values of Hofstede, all the hypotheses of this work are confirmed, except for that concerning the LTO.

Figure 1. Comparison between the values of Hofstede's indicators and the same ones deriving from our model for India and Australia.

In particular, as regards the PDI, India has a much higher value than Australia (H. 1 verified). The analyzed Indian websites show images depicting buildings, important people with their titles (for example photos of top managers and buildings of company headquarters), and references to honors and awards won by the company. These images reflect Indian culture characterized by high respect for rules and hierarchies.

Observing the values of the IDV, we can highlight how Indian websites present a greater frequency of images representing groups of people than Australian ones, where people are mainly represented individually (a lower IDV value of India, H. 2 verified).

Regarding the MAS indicator, Indian websites have a lower frequency of images of only men than Australian ones (H. 3 verified).

Analyzing the UAI values, Indian websites have a lower frequency of cultural markers related to risk aversion than Australian ones. Marcus and Gould (2000) affirm that cultures with a low value of this dimension, showing a lower aversion to uncertain and unknown situations, tend to a more explorative approach to the web. On the contrary, cultures with a high value favor help systems that focus on reducing user errors (FAQs, customer service) and navigation systems intended to reassure the user during the navigation (navigation path and site map). This consideration is confirmed by the analysis of Australian websites, the majority of which present help systems in customer experience, site maps and free downloads (H. 4 verified).

As regards the LTO index, the following critical issues are highlighted: the values of our model differ from the original ones of Hofstede, and hypothesis five is not verified, since the values of India and Australia are equal. In fact, Indian websites do not show a greater frequency of cultural markers, such as the search bar, the index page, and the FAQs page.

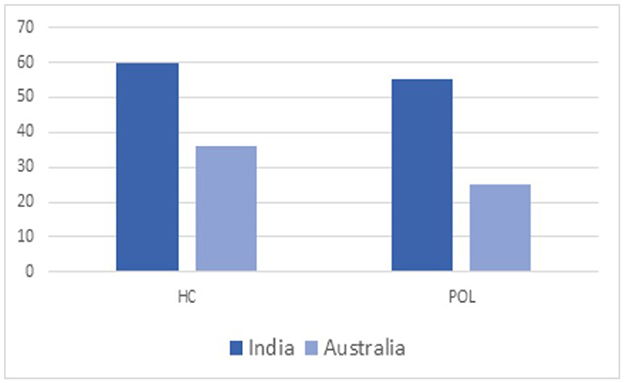

Figure 2 shows the Hall values calculated according to our model. Hall did not develop a model for the calculation of the indicators, offering theoretical reference numbers that could serve for comparison in the present study; however, he did evaluate Indian culture as high context and polychronic and Australian one as low context and monochronic (Hall, 1989). These evaluations are confirmed by our analysis: India shows higher HC and POL indexes than Australia (H. 6 and H.7 verified). In fact, from the analysis of web design of Indian websites, we observe a wide use of images and animations that accompany the text or sometimes put it in the background. Navigation is not very transparent because of a limited amount of text and often requires that the user must research the information through the exploration of the site.

The quantity and variety of contents make navigation less schematic and more explorative.

6. Discussion

Within the field of cultural studies, cross-cultural comparisons are at the center of the debate on the intersection of cultures and organizations (Lyan, 2021). This paper carries out the cross-cultural comparison to evaluate the fitting of corporate communication to the national culture, focusing on web communication, which, in general, should be able to provide information in meaningful and effective ways (Brown, 2021).

The main literature underlines how web communication should be designed through “culturally usable” websites, rather than the approach “one-size-fits-all” (Nantel and Glaser, 2008; Zaharias, 2008; Al-Badi and Mayhew, 2010; Hamid, 2017; Pratap and Kumar, 2019). A single international version does not allow to stimulate interest, acceptability, and “e-loyalty” among users: on the contrary, a corporate website should be a mirror of the country's culture.

The main aim of this paper is to understand how cultures are represented on the web and which role play cultural differences. To that aim, we extend the existing frameworks on website “culturability,” based on the theories of Hofstede and Hall. We take into account two different countries, India and Australia, which are at opposite cultural poles, but at the same time have long-standing business relationships.

By analyzing the relationship between cultural characteristics and company websites, many previous studies have been limited to observing the layout and images, taking only a qualitative approach. The current work develops a quantitative model that adapts Hofstede's cultural dimensions to the features and content of website design. Moreover, the study also provides a quantification of Hall's cultural framework to the context of web communication.

This new quantitative model is applied to a sample of 1,000 companies, 500 quoted on the National Stock Exchange of India and 500 quoted on the National Stock Exchange of Australia.

We use the main literature references as a guide to select the website elements best representing cultural dimensions. The corporate websites are content analyzed in terms of these relevant elements, and the observations are used for the calculation of the cultural indicators. Therefore, we calculate the new values of the indicators to evaluate the conformity of the website design with Hofstede's and Hall's cultural dimensions and the dissimilarity between the websites of the two countries so much culturally different.

The observed values of the IDV for India, the UAI, and MAS for both countries are very close to Hofstede's indicators. Hall's model of cultural characteristics did not provide for a quantitative approach, making it impossible to offer a numeric comparison with the observed measures. However, the results demonstrate high context and polychronic characteristics for Indian websites, whereas low context and monochronic approach for Australian ones, by corresponding to Hall's observations on these cultures. The high context and polychronic cultural characteristics are expressed in particular in the heavy use of website banners, scrollbars, animations, and complex menus, which offer the user a multitude of clickable content.

The empirical analysis of websites demonstrates higher Australian values for MAS, UAI, and IDV than the Indian ones. These dimensions are measured through observation of specific design and content elements such as men and individual images, help tools in customer experience, and in customer navigation. According to Hofstede's theory, the results of our analysis show that Australia is a country characterized by a higher index of individualism, masculinity, and uncertainty avoidance compared to India. On the contrary, India has a higher index of PDI than Australian one: in Indian websites, there is a greater presence of cultural markers, such as images of leaders, national emblems, monumental buildings, and references to titles and prizes. According to Hofstede's theory, the value of this index shows that the Indian culture accepts power and hierarchy as an integral part of the society.

The only result in disagreement with Hofstede's theory is that regarding the long-term orientation index. From our analysis, the values of LTO are the same for Indian and Australian websites, while Hofstede classifies Indian culture with a high long-term orientation and, vice versa, the short-term Australian one.

Except for the long-term orientation, the theoretical implications of this work highlight a correspondence between website content and design and the cultural dimensions of Hofstede and Hall. In the broad scientific debate in the field of online communication between standardization vs. adaptation, this paper supports the theory that national culture matters. Despite the global connection enabled by the internet and the consequent “one size fits all” approach in web design, the findings of this work support the assumption that online communication reflects the culture and that culturally oriented corporate websites are well grounded.

The previous literature has provided empirical evidence that web design should be culturally customized (Ahmed et al., 2009; Gevorgyan and Manucharova, 2009; Alexander et al., 2017). The originality of this paper is the development of ad hoc indicators aimed at measuring the dimensions of Hofstede and Hall in two countries (India and Australia), never compared until now, to the best of our knowledge. Furthermore, for the first time, a quantification of Hall's framework is provided in the context of web communication. The calculation of cultural dimensions allows a discussion based on measurable parameters instead of qualitative assessment. This could be useful for communication and culture scholars within online communication.

As concerns the practical implications, this work can be the basis for a guideline helpful for communication experts, companies, marketers, and advertisers, who want to enter the market of India or Australia. In particular, this guideline is suitable for the different professionals involved in website design; our findings might help them to decide regarding the choice of website content and design.

Communication experts and marketers can use the results of our work to adapt the website content and design according to the national culture of the target country. For example, in India, where Hall's high context and polychronic dimensions are significant, it will be necessary to design website communication by inserting more images and icons than text, and multiple animations that make navigation more intuitive. In Australia, where there is a certain risk aversion index, it will be advisable to design schematic and calm navigation, making the customer experience more user-friendly, with detailed menus and online help systems.

Although the results offer valuable implications, they are subject to twofold limitations. Firstly, the study was done on a quite small sample and, secondly, the focus is only on some elements of design and content of websites. Future research should be on a larger scale, considering further elements of content and web design. Furthermore, the model has been tested considering two countries but can be generalized and applied to any country. Despite these limitations, this paper tries to overcome the qualitative approaches provided by much of the previous literature, developing a quantitative model of analysis of cross-cultural communication useful to improve the usability and user experience.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to ZnJhbmNlc2NhLmRpcGlsbG9AdW5pcm9tYTEuaXQ=.

Author contributions

Both authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the raters who evaluated the websites.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Ackerman, S. (2002). “Mapping user interface design to culture dimensions,” in International Workshop on Internationalization of Products and Systems (IWIPS'02) (Austin, TX).

Adnan, S. M., Hay, D., and van Staden, C. J. (2018). The influence of culture and corporate governance on corporate social responsibility disclosure: a cross country analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 198, 820–832. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.07.057

Ahmed, T., Mouratidis, H., and Preston, D. (2009). Website design guidelines: high power distance and high-context culture. Int. J. Cyber Soc. Educ. 2, 47–60.

Al-Badi, A. H., and Mayhew, P. J. (2010). A framework for designing usable localised business websites. Commun. IBIMA 1–24. doi: 10.5171/2010.184405

Alexander, R., Thompson, N., and Murray, D. (2017). Towards cultural translation of websites: a large-scale study of Australian, Chinese, and Saudi Arabian design preferences. Behav. Inf. Technol. 36, 351–363. doi: 10.1080/0144929X.2016.1234646

Barber, W., and Badre, A. (1998). “Culturability: The merging of culture and usability,” in Proceedings of the 4th Conference on Human Factors and the Web in Basking Ridge. (United States), 1–10.

Barron, A., and Schneckenberg, D. (2012). A theoretical framework for exploring the influence of national culture on Web 2.0 adoption in corporate contexts. Electron. J. Inf. Syst. Eval. 15, 176–186.

Brown, E. E. (2021). Assessing the Quality and Reliability of COVID-19 Information on Patient Organization Websites. Front. Commun. 162:716683. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2021.716683

Burgmann, I., Kitchen, P. J., and Williams, R. (2006). Does culture matter on the web? Mark. Intell. Plan. 24, 62–76. doi: 10.1108/02634500610641561

Capece, G., and Di Pillo, F. (2021). Chinese website design: communication as a mirror of culture. J. Mark. Commun. 27, 137–159. doi: 10.1080/13527266.2019.1636120

Cardon, P. W. (2008). A critique of Hall's contexting model: a meta-analysis of literature on intercultural business and technical communication. J. Bus. Tech. Commun. 22, 399–428. doi: 10.1177/1050651908320361

Chacko, P., and Davis, A. E. (2017). The natural/neglected relationship: liberalism, identity and India-Australia relations. Pac. Rev. 30, 26–50. doi: 10.1080/09512748.2015.1100665

Cheng, H., and Schweitzer, J. C. (1996). Cultural values reflected in Chinese and US television commercials. J. Advert. Res. 36, 27–46.

Cyr, D., Head, M., and Larios, H. (2010). Colour appeal in website design within and across cultures: a multi-method evaluation. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 68, 1–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhcs.2009.08.005

De Troyer, O., Mushtaha, A., Stengers, H., Baetens, M., Boers, F., Casteleyn, S., et al. (2006). On cultural differences in local web interfaces. J. Web Eng. 5, 246–264.

Engelen, A., and Brettel, M. (2011). Assessing cross-cultural marketing theory and research. J. Bus. Res. 64, 516–523. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2010.04.008

Gevorgyan, G., and Manucharova, N. (2009). Does culturally adapted online communication work? a study of American and Chinese internet users' attitudes and preferences toward culturally customized web design elements. J. Comput. Mediat. Commun. 14, 393–413. doi: 10.1111/j.1083-6101.2009.01446.x

Gommans, M., Krishman, K. S., and Scheffold, K. B. (2001). From brand loyalty to e-loyalty: a conceptual framework. J. Econ. Soc. Res. 3, 43–58.

Gong, W., Stump, R. L., and Li, Z. G. (2014). Global use and access of social networking websites: a national culture perspective. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 8, 37–55. doi: 10.1108/JRIM-09-2013-0064

Gould, E. W., Zalcaria, N., and Yusof, S. A. M. (2000). “Applying culture to website design: a comparison of Malaysian and US websites”, in Proceedings of the 18th Annual ACM International Conference on Computer Documentation: Technology and Teamwork, IEEE.

Gudykunst, W. B. (2004). Bridging Differences: Effective Intergroup Communication. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. doi: 10.4135/9781452229706

Hallikainen, H., and Laukkanen, T. (2018). National culture and consumer trust in e-commerce. Int. J. Inf. Manage. 38, 97–106. doi: 10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2017.07.002

Hamid, M. A. (2017). Analysis of visual presentation of cultural dimensions: Culture demonstrated by pictures on homepages of universities in Pakistan. J. Market. Commun. 23, 592–613. doi: 10.1080/13527266.2016.1147486

Herring, S. C. (2009). Web Content Analysis: Expanding the Paradigm. In International handbook of Internet Research. Springer, Dordrecht, p. 233–249. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4020-9789-8_14

Hofstede, G. (1980). Culture and organizations. Int. Stud. Manag. Organ. 10, 15–41. doi: 10.1080/00208825.1980.11656300

Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture's Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions and Organizations Across Nations, Sage.

Jiacheng, W., Lu, L., and Francesco, C. A. (2010). A cognitive model of intra-organizational knowledge-sharing motivations in the view of cross-culture. Int. J. Inf. Manage. 30, 220–230. doi: 10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2009.08.007

Kassarjian, H. H. (1977). Content analysis in consumer research. J. ConsuM. Res. 4, 8–18. doi: 10.1086/208674

Krippendorff, K. (2004). Measuring the reliability of qualitative text analysis data. Qual. Quant. 38, 787–800. doi: 10.1007/s11135-004-8107-7

Krippendorff, K. (2018). Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. doi: 10.4135/9781071878781

Kulkarni, R. B., Rajeshwarkar, P. R., and Dixit, S. K. (2012). Cultural analysis of Indian websites. Int. J. Comput. Appl. 38, 15–21. doi: 10.5120/4627-6870

Laleman, F., Pereira, V., and Malik, A. (2015). Understanding cultural singularities of ‘Indianness' in an intercultural business setting. Cult. Organ. 21, 427–447. doi: 10.1080/14759551.2015.1060232

Lamb, Y., Cai, W., and McKenna, B. (2020). Exploring the complexity of the individualistic culture through social exchange in online reviews. Int. J. Inf. Manage. 54, 102198. doi: 10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2020.102198

Lombard, M., Snyder-Duch, J., and Bracken, C. C. (2002). Content analysis in mass communication: assessment and reporting of intercoder reliability. Hum. Commun. Res. 28, 587–604. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2958.2002.tb00826.x

Luna, D., Peracchio, L. A., and de Juan, M. D. (2002). Cross-cultural and cognitive aspects of web site navigation. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 30, 397–410. doi: 10.1177/009207002236913

Luo, C., Wu, J., Shi, Y., and Xu, Y. (2014). The effects of individualism–collectivism cultural orientation on eWOM information. Int. J. Inf. Manage. 34, 446–456. doi: 10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2014.04.001

Lyan, I. (2021). ‘Koreans are the Israelis of the East': a postcolonial reading of cultural similarities in cross-cultural management. Cult. Organ. 27, 1–19. doi: 10.1080/14759551.2021.1955254

Marcus, A., and Gould, E. W. (2000). Crosscurrents: cultural dimensions and global Web user-interface design. Interactions 7, 32–46. doi: 10.1145/345190.345238

Moura, F. T., Singh, N., and Chun, W. (2016). The influence of culture in website design and users' perceptions: three systematic reviews. J. Electron. Commer. Res. 17, 312–339.

Nantel, J., and Glaser, E. (2008). The impact of language and culture on perceived website usability. J. Eng. Technol. Manag. 25, 112–122. doi: 10.1016/j.jengtecman.2008.01.005

Neuendorf, K. A. (2017). The Content Analysis Guidebook. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. doi: 10.4135/9781071802878

Ng, S. I., Lee, J. A., and Soutar, G. N. (2007). Are Hofstede's and Schwartz's value frameworks congruent? Int. Mark. Rev. 24, 164–180. doi: 10.1108/02651330710741802

Okazaki, S. (2004). Do multinationals standardise or localise? the cross-cultural dimensionality of product-based web sites. Int. Res. 14, 81–94. doi: 10.1108/10662240410516336

Pereira, V., and Malik, A. (2015). Making sense and identifying aspects of Indian culture (s) in organisations: Demystifying through empirical evidence. Cult. Organ. 21, 355–365. doi: 10.1080/14759551.2015.1082265

Pollay, R. W. (1983). Measuring the cultural values manifest in advertising. Curr. Issues Res. Advertising 6, 71–92.

Prakash, C. D., and Majumdar, A. (2021). Analyzing the role of national culture on content creation and user engagement on Twitter: the case of Indian premier league cricket franchises. Int. J. Inf. Manage. 57, 102268. doi: 10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2020.102268

Pratap, S., and Kumar, J. (2019). A Dimensional Analysis Across India to Study How National Cultural Diversity Affects Website Designs. In Research into Design for a Connected World. Springer, Singapore, (653–664). doi: 10.1007/978-981-13-5977-4_55

Rhoads, J. (2019). The influence of national culture on the construction of new media content. Hermathena 208, 1–5.

Ribiere, V. M., Haddad, M., and Wiele, P. V. (2010). The impact of national culture traits on the usage of web 2.0 technologies. Vine. 40, 334–361. doi: 10.1108/03055721011071458

Robbins, S. S., and Stylianou, A. C. (2010). A longitudinal study of cultural differences in global corporate web sites. J. Int. Bus. Cult. Studies 3, 1–17.

Sharma, A. (2016). Australia-India relations: trends and the prospects for a comprehensive economic relationship, Record series 02/2016, Australia South Asia Research Centre.

Shobeiri, S., Mazaheri, E., and Laroche, M. (2018). Creating the right customer experience online: the influence of culture. J. Mark. Commun. 24, 270–290. doi: 10.1080/13527266.2015.1054859

Singh, N., and Baack, D. W. (2004). Web site adaptation: A cross-cultural comparison of US and Mexican web sites. J. Comput.-Mediat. Commun. 9. doi: 10.1111/j.1083-6101.2004.tb00298.x

Singh, N., and Matsuo, H. (2004). Measuring cultural adaptation on the Web: a content analytic study of US and Japanese Web sites. J. Bus. Res. 57, 864–872. doi: 10.1016/S0148-2963(02)00482-4

Singh, N., Zhao, H., and Hu, X. (2005). Analyzing the cultural content of web sites: a cross-national comparision of China, India, Japan, and US. Int. Mark. Rev. 22, 129–146. doi: 10.1108/02651330510593241

Sjøvaag, H., and Stavelin, E. (2012). Web media and the quantitative content analysis: methodological challenges in measuring online news content. Convergence 18, 215–229. doi: 10.1177/1354856511429641

Tinsley, H. E., and Weiss, D. J. (1975). Interrater reliability and agreement of subjective judgments. J. Couns. Psychol. 22, 358. doi: 10.1037/h0076640

Trompenaars, F., and Hampden-Turner, C. (2011). Riding the Waves of Culture: Understanding Diversity in Global Business, Nicholas Brealey International.

Wasowicz-Zaborek, E. (2018). Influence of national culture on website characteristics in international business. Int. Entrepreneurship Rev. 4, 421.

Weare, C., and Lin, W. Y. (2000). Content analysis of the World Wide Web: opportunities and challenges. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 18, 272–292. doi: 10.1177/089443930001800304

Würtz, E. (2005). Intercultural Communication on Web sites: a Cross-Cultural Analysis of Web sites from High-Context Cultures and Low-Context Cultures. J. Comput. Mediat. Commun. 11, 274–299. doi: 10.1111/j.1083-6101.2006.tb00313.x

Keywords: corporate communication, cultural usability, web design, cultural indicators, national culture, content analysis

Citation: Capece G and Di Pillo F (2023) Online corporate communication: Should national culture matter? Front. Commun. 8:1005903. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2023.1005903

Received: 28 July 2022; Accepted: 27 February 2023;

Published: 16 March 2023.

Edited by:

Tamara Menichini, University of Rome “Niccolò Cusano”, ItalyReviewed by:

Rita Gill Singh, Hong Kong Baptist University, Hong Kong SAR, ChinaMichele Grimaldi, University of Cassino, Italy

Armando Calabrese, University of Rome Tor Vergata, Italy

Copyright © 2023 Capece and Di Pillo. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Francesca Di Pillo, ZnJhbmNlc2NhLmRpcGlsbG9AdW5pcm9tYTEuaXQ=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Guendalina Capece

Guendalina Capece Francesca Di Pillo

Francesca Di Pillo