Introduction

Queer intercultural communication offers the great promise to advance communication—academically, culturally, and politically—not only for sexual and gender minority communities across the globe but for all communities as they grapple with questions of identity and difference in an increasingly neoliberal and global social world (Yep et al., 2019, p. 2).

In the introduction of the Journal of International and Intercultural Communication's special issue, “Out of Bounds? Queer Intercultural Communication,” the editor, Chávez (2013), acknowledged that there had been a dearth of communication studies exploring “the intersections and interplays between the queer and the intercultural” (p. 84). Heteronormative studies that examined the lives and experiences of cisgender people marginalizing other gender identities, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender people, queer, intersex, and asexual (LGBTQIA+) have dominated the field (Eguchi and Asante, 2016). Although there have been studies on queer theory and other queer themes in and outside the communication field, these studies have mainly been conducted in the Global North, where White/Western ideologies of homonormativity remained the source and standard for queerness (Chávez, 2013; Eguchi and Asante, 2016). Ulla and Pernia (2022) affirmed that the “lack of studies that reflect the lives of the LGBTQIA+ people, especially those LGBTQIA+ people of color and from the Global South, limits our understanding of culture and communication” (p. 3)

While queer theory studies may concentrate only on the constitutive discourses of identity, sexuality, politics, and the lives and experiences of LGBTQIA+ people, they may not clearly reference culture and cultural differences, particularly from the Global South. Eguchi (2021) and Huang (2021) noted that most of the queer research centered only on the United States and other Global North countries, producing. theories that are only relevant for queer1 and trans people there. Such an emphasis on the Global North as the key source of knowledge for queer studies not only limits queer scholarship from multiple perspectives but also goes against the very aim of queer theory's antinormativity from the global perspective (Gambino, 2020).

Furthermore, studies on intercultural communication may have only focused on culture and cultural differences without directly focusing on LGBTQIA+ people's lived experiences and stories (Ulla and Pernia, 2022). Eguchi and Asante (2016) maintained that “the body of literature considered as the ‘mainstream' intercultural communication scholarship has not adequately articulated the fluidity and complexity of sexuality, sex/gender, and body” (p. 172). They emphasized that sexuality, sex/gender, and body, which are influenced by social, cultural, political, and historical contexts, are crucial to building overall identities.

Chávez (2013) argued that intercultural communication studies about sexuality, culture, and communication should be explored and valued to theorize and advance the area of queer intercultural communication. Yep (2013) noted:

Queer and transgender studies provide communication scholars and practitioners with powerful theoretical and political tools for examining the production and constitution of modes of differences-particularly those related to gender and sexuality, and, to a somewhat lesser extent, race, class, ability, nation, and culture-in our communicative and rhetorical practices, mediated representations, and cultural discourses (p. 119).

A marriage of two disciplines, queer intercultural communication recognizes the experiences, perspectives, and importance of LGBTQIA+ people in studying and understanding culture and communication. It connects the gap between queer studies and intercultural communication studies, forming a discipline and a theory that advances the intersectionality of race, gender, culture, and identity. In addition, queer intercultural communication challenges the production of knowledge and practices accepted and recognized only by the heteronormative society by unmasking the conditions of inequality and injustices. Thus, it tries to seek the transformation of such conditions to empower and liberate marginalized groups.

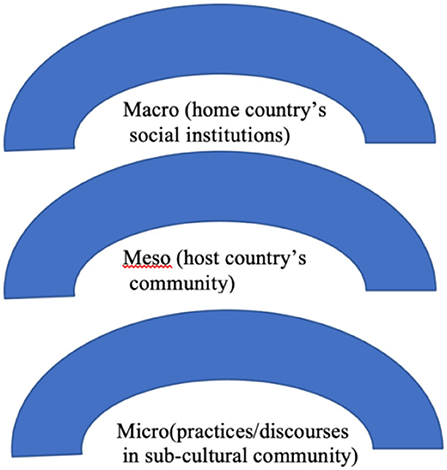

Using Yep et al. (2019) integrative view of queer intercultural communication through examining the significant contexts—macro, meso, and micro levels of social conditions that shaped and formed the identity and sexuality among gay men migrants, this article follows the discussion thread on theorizing queer intercultural communication by previous scholars (see Chávez, 2013; Eguchi and Asante, 2016; Yep et al., 2019). It also expounds on previous work, situating queer intercultural communication study in Filipino gay men's migration within the Global South-South context (Ulla and Pernia, 2022), I argued that there is a need for queer intercultural communication scholars to think across macro, meso, and micro contexts, especially within Global South-South contexts, to gain a deeper understanding of the multiple sites and directions of oppression that minoritized LGBTQIA+ people and their experiences in society.

I begin with the discussion on queer migration in the Global South, particularly referencing queer migration studies in Southeast Asia, followed by the presentation and discussion on examining and doing queer intercultural communication with the Queer Emancipatory Migration Framework of Communication. Centering my discussion on the macro, meso, and micro contexts of queer migration, I conclude with a note on the importance of examining queer people's experiences to push forward queer intercultural communication within the Global South context.

Global south, queer, and migration

Contemporary migration has been aided by globalization, where the movement of goods and services also supports the movement of people (Ulla and Pernia, 2022). Such mobility can be explained by the push and pull theory of migration that demonstrates the economic, political, personal, and social factors. These factors can either push or pull people to leave their home country (Reza et al., 2019). For instance, people who experienced poverty, political crisis, and job inequality may likely leave and seek better lives in another country. Likewise, a country that offers better work wages, job security, and welfare will mostly attract international migrants (Babar et al., 2019). Given the common reasons why people migrate, gay men's decision to relocate may also be influenced by globalization, where the desire to improve one's life and experience a preferred lifestyle is one of the deciding factors for their migration.

In most of the countries in the ASEAN2 region, where poverty and economic opportunities may be limited (Harkins and Lindgren, 2017), gay men may look for better and high-paying jobs outside of their country to support their families (Ulla and Pernia, 2022). They may work illegally or legally in low-skilled or highly skilled jobs within the region. In some cases, they may become victims of sex trafficking and sexual exploitation, which is underreported due to the stigma associated with being gay (Martinez and Kelle, 2013; Barron and Frost, 2018). Thus, in their efforts to improve their quality of life, gay men may encounter difficulties in the migration process, especially as most countries in the region may not accept or tolerate gay men and other gender identities. Gay men may want to express their sexual identity in their home country but know that it may cause a problem for themselves and their families. For example, in a study conducted by Manalastas et al. (2017) on people's attitudes, feelings, and behaviors toward lesbians and gay men in the countries of Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam, they found that people had negative attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors toward lesbians and gay men.

Moreover, people from Indonesia and Malaysia held the most negative attitude toward lesbians and gay men because of their religion. Such a negative attitude not only hinders gay men from communicating their identities and expressing their sexuality but may also become a venue for workplace discrimination. For instance, in a study conducted by Oosterhoff and Hoang (2018) on entrepreneurialism, workplace and employment experiences among transgenders in Vietnam, the researchers reported that transgenders experienced severe and apparent discrimination in the workplace, preventing them from getting promotions, benefits, and equal pay. Transgender people also found it difficult to get bank loans as they were required to show an identity card, which did not show their current gender identity.

It should be noted that gay men in the ASEAN region may prefer to move from their home country to come out, express their sexuality and identity, and work where they feel safe (Ulla and Pernia, 2022). However, many gay men may choose not to come out for fear of discrimination or only prefer to come out to people who can understand them. They may find it easier to come out to their mother than to their father, who may invoke authority and power over them (Tamagawa, 2018). In some instances, gay men and other members of the LGBTQIA+ community may never come out to their families “for fear of religious and social prosecutions” (Maulod, 2021, p. 1111). For example, Cheah and Singaravelu (2017) revealed that LGBTQIA+ people in Malaysia chose to come out to their friends because they knew that their friends would understand them, support them, and give them a sense of belongingness as compared to their parents. Cheah and Singaravelu (2017) mentioned that the parents might have biases and misconceptions “due to the negative portrayal of LGBTQIA+ people in the Malaysian media” (p. 417) and due to their lack of a deeper understanding of the identities. As a result, some gay men move to other countries or big cities where they may feel safe and free to come out and express themselves. Langarita Adiego (2020) mentioned that LGBTQIA+ people migrate to big cities as these cities provide a safe space for them where they can recreate themselves and their subjectivities, become anonymous, explore their sexuality, and experience freedom.

Doing queer intercultural communication research in migration

Yep et al. (2019) maintained that queer intercultural communication could be understood by examining the “interactions, symbolic representations, and cultural discourses through careful attention to three simultaneous contexts: macro (larger political, cultural, and historical forces), meso (attitudes and relationships between social and cultural groups), and micro (interactions between individuals in various communities)” (p. 2). However, while Yep et al.'s (2019) macro, meso, and micro contexts defined an integrative view of queer intercultural communication, they are broadly presented and thus showed an apparent decrease in level (institution, community, and individual). They do not precisely represent the specific social institutions and conditions that shape and form the identity and sexuality among queer people in the context of migration.

In this paper, I propose a more specific discussion on the social conditions that influence the macro, meso, and micro contexts regarding gay men's identity and sexuality by pushing forward the “Queer Emancipatory Migration Framework of Communication.” Looking at these three specific simultaneous contexts provides a clear understanding of the gay men's migration journey within the Global South from incarceration in their home country to emancipation in their host country. Furthermore, the framework allows us to uncover and highlight the issues of identity and belonging from the communication experiences and practices of gay men. The framework also sheds a new perspective on the nuances of sexuality, migration, and communication and contributes to the theorization of queer intercultural communication.

It should be noted that from the lens of migration, I defined the “macro” level as the home country's social institutions, “meso” as the host country's community, and “micro” as the individual practices, discourses, and behaviors of gay men within the sub-cultural community of the host country. The following Figure 1 illustrates this framework.

Figure 1. The macro, meso, and micro levels of social conditions that shape and form queer people's identity and sexuality.

In the following section, I will provide an example of the value of this framework using a previous study I published along with E. E. Pernia.

The macro level (home country's social institutions)

To understand the migration decisions among Filipino gay men, it is of utmost importance to consider the economic reasons and the cultural context in which they have lived. In the Philippines, labor migration has become an important practice among Filipinos who want to better their lives economically due to the lack of employment opportunities and low-salary rates (Ulla and Pernia, 2022). In fact, Bailey and Mulder (2017) recognized that the Philippines is one of the largest sources of highly skilled labor migrants in the OECD3 areas, along with India and China. In 2015, the estimated number of Filipinos living and working overseas was 7,979,716, of which about four million were based in the Americas (Department of Foreign Affairs (DFA), 2019).

In the study by Ulla and Pernia (2022), highly skilled Filipino gay men moved to Bangkok, Thailand, primarily for economic reasons. We found that in integrating themselves into the new cultural environment, highly skilled Filipino gay men came to explore and understand their sexuality. However, in this study, we did not discuss the macro factors regarding why highly-skilled Filipino gay men were restricted from expressing their sexuality in their home country. As reported by our participants, these macro factors were social institutions, like the church (religion), family, employment companies, and schools, which could influence perspectives toward LGBTQIA+ people.

For example, although the Philippines is considered a gay-friendly country (Rodriguez, 1996; Tang and Poudel, 2018) and is ranked number one in Asia in closing the gender gap (World Economic Forum, 2021), some efforts to recognize the rights of queer people have been frequently opposed and rejected by the Catholic Church (Human Rights Watch, 2017).

Efforts to advance LGBTQIA+ rights [that] have met with resistance from the Catholic Church, which has been an influential political force on matters of sex and sexuality. While the Catholic Bishops Conference of the Philippines (CBCP) rejects discrimination against LGBTQIA+ people in principle, it has frequently opposed efforts to prohibit that discrimination in practice (Human Rights Watch, 2017, p. 10).

Although not a sin, being gay in the Philippines is treated by the catholic church as “objective disorder” (Cornelio and Dagle, 2022). Consequently, massive discrimination and bullying among gay men are still evident. In fact, Filipino men who are effeminate are often labeled as “bakla,” “bading,” or “bayot” (Ulla and Pernia, 2022). The terms “bakla” and “bading” may be widely used in Manila, the capital, and other provinces in Luzon Island. Likewise, the term “bayot” is commonly used in the Visayas and Mindanao islands. These terms are perceived to be derogatory since they are mostly used to bully, discriminate, and identify gay men. Instead of calling a person by his real name, he is often called “bakla,” “bading,” or “bayot.” In another situation for example, when a man failed to do something or simply made a mistake, he is often blamed because of being effeminate by saying “bakla/bading kasi” (because he is gay) (Ulla and Pernia, 2022).

Furthermore, despite the call to become a safe space for everyone, instances of discrimination, physical assault, bullying, and harassment in school not only among gay men but also other members of the LGBTQIA+ community have also been identified. For instance, the study carried out by the Human Rights Watch (2017) noted that physical bullying, which includes punching, hitting, shoving, sexual assault and harassment, verbal harassment, and cyberbullying were experienced by LGBTQIA+ students in 10 cities of Luzon and Visayas islands in the Philippines. Similarly, the study conducted by Tang and Poudel (2018) reported that one of the challenges faced by LGBTQIA+ students in Philippine schools is the inability of the teachers to recognize the gender identity of their students. The misuse of gender pronouns is reported to be evident in the classroom as teachers still use the pronoun “he” to refer to a transgender woman. Tang and Poudel also mentioned that the refusal of other schools especially Catholic schools to admit LGBTQIA+ students is also a discriminatory school practice.

Ulla and Pernia (2022) also affirmed that being gay was a challenge for highly skilled Filipino gay men in the Philippines since their work places required them to identify within the gender binary spectrum. Gay people experienced workplace discrimination and were also prevented from getting promotions. In De Guzman's (2020) study, she mentioned that workplace discrimination can be “manifested through subtle forms, and mostly included under sided remarks or inappropriate comments and questions” (p. 10). Thus, men had to disidentify as gay men because they did not want to be shamed, bullied, or disrespected. These discriminatory practices and discourses impacted gay men's work relationships.

Gay men's judgments regarding who they were and how they should express themselves were associated with how the dominant members of society acted and behaved. Since the heteronormative workplace culture did not allow them to communicate their authentic identity, they remained in the closet to participate in the activities and discourses within their cultural context without repercussions. Such self-disidentifications can limit freedom of self-expression. It may be assumed that when gay men disidentify themselves as gay men in their workplaces, they would have the freedom to participate in heteronormative practices while discreetly engaging in various queer discourses and practices without injustice and discrimination.

The family also plays a crucial role in gay men's sexuality and identity expressions. Most often, some religious and conservative families may not accept and tolerate children who are gay. Thus, gay men are afraid to come out for fear of disownment. However, others may accept and tolerate gay members of the family as long as these gay family members have financial contributions and that they perform “androgynous tasks for the family or traditional feminine roles like cleaning, decorating, and taking care of children” (Presto, 2020, p. 140). Presto (2020), in her study on the experiences of young poor gay men in rural areas in the Philippines, argued that financial contribution to the family “is not identified as a prerequisite for acceptance, but a validation of worth vis-à-vis their marginality and exercise of resistance vis-à-vis their experience of discrimination—even at a young age.” (p. 140).

However, given the home country's social institutions' influence on identity and sexuality expressions among gay men in the Philippines, it should be noted that at the macro level, the framework only considers the home country's institutional discourses relevant. Since it stems from the individual's experience, the framework can only be understood and used in a home country whose social institutions impose discriminatory discourses and practices toward gay men or other members of the LGBTQIA+ community. Hence, the framework is temporal and spatial.

The meso level (host country's community)

Although gay men's migration motive is primarily linked to economic opportunities, it can be argued that gay men consider a more open society when moving out of their home country. They may prefer a country where they may find support in claiming a space, acknowledging, and recognizing their identity and sexuality. In other words, homonegative social institutions may also push LGBTQIA+ people to leave their home countries and settle in places where they are acknowledged. For example, Wimark (2016) explored the migration motives among gay men in Malmö, Sweden, the host city, and affirmed that younger gay men left their homes to seek support and belonging. Similarly, Okada (2022), who also studied the migration motives and experiences of Filipino transgender entertainers in Japan, concluded that Filipino transgender entertainers found “Japan as a land of promise and a safe space, where they can blend in and express their gender identity” (p. 33).

Wimark' (2016) and Okada's (2022) findings suggest that members of the LGBTQIA+ community migrate to a new cultural environment where they not only find economic opportunities but also support and belonging. Thus, a more open society and a cultural community became the target destination among gay men migrants. Since these institutions may allow them to express their identity and sexuality freely, gay men migrants may feel emancipation from the repercussions of the heteronormative discourses and practices like the ones they had back in their home country.

Furthermore, as gay men migrants settle into a new cultural community with a positive and accepting attitude toward them, they begin to interact and develop relationships with people between their social and cultural groups. On a meso level, such interaction and integration into the new cultural community are important among gay men to gain visibility and empowerment. They may begin to develop a sense of themselves, change or modify their cultural belief regarding their identity and sexuality, and be recognized.

In Thailand, for example, as reported in the study by Ulla and Pernia (2022), highly-skilled Filipino gay men found equality and recognition in Bangkok's society. Particularly at their workplaces, since there are also no laws that criminalize homosexuals, same-sex practices, and cross-dressing in Thailand (Sanders, 2019), highly-skilled Filipino gay men were appreciated, acknowledged, and treated equally regardless of race and gender. They felt they were free to express their identity and sexuality since people in Thailand, especially at their workplaces, allowed them to be who they were. Such a finding was also supported by Hur (2020). Hur (2020), who examined the impact of inclusive work environment practices among members of the LGBTQIA+, maintained that “inclusive work environments have a positive effect on LGBTQIA+ employee job satisfaction and affective commitment” (p. 433).

Ulla and Pernia (2022) opined that such tolerance and acceptance toward homosexuality in Thailand are believed to be influenced by Buddhism, the religion of most Thai people. In fact, Jackson (1995) confirmed such influence:

The scriptures describe the Buddha as demonstrating a compassionate attitude towards people who began to show cross-gender characteristics after ordination and who, while attracted to members of the same sex, were regarded as being physiologically and behaviorally true to the prevailing cultural notions of masculinity (p. 144).

Besides inclusive work environments, another essential factor that supports the emancipation of gay men in their host country at the meso level is the presence of gay safe spaces like gay clubs, gay massage parlors, and surgery clinics for gay men. For gay men, these safe spaces symbolize their recognition and acknowledgment, which may be hidden from them in their home countries. They may also begin to engage and participate in queer discourses and practices without fear of being bullied and discriminated against.

For instance, Thailand has become a favorite destination and is considered a gay paradise among gay men because it promotes queer tourism (Shrestha et al., 2020) through the presence of various gay spaces all over the country's major cities. These spaces are vital since gay men feel included, are not harassed, and are treated equally in their new environment. Likewise, the presence of gay spaces provide gay men the venue to understand themselves and explore their sexuality. Thus, it can be argued that within the meso level of social conditions, it is important to note that equality, inclusion, and belonging in the new society are essential factors for queer people to recreate themselves. Since these factors amplify their voices and increase their social presence, gay men may feel freedom from the hegemonic masculinity that suppresses their rights to express themselves. Their daily interactions with the new community that allows them to be who they are, encourages positive perspectives about themselves. In addition, gay men are no longer invisible as they get to assert their identities and be included in their new society.

Indeed, a society that welcomes, acknowledges, and recognizes queer people play a vital role in the emancipation of the members of the LGBTQIA+ community. When LGBTQIA+ people are given the space and recognition in society, they may engage in communicative practices that would change their perspectives of who they are, as influenced by their home country's culture. They would learn to adapt to the new cultural community's practices in order to gain a sense of belonging (Ulla and Pernia, 2022). Such practices would also enable them to interact with the people in society, allowing them to reconstruct or maintain their identities.

The micro level (the host country's gay community)

The host country's gay community (also referred to as the sexual minority community) is crucial in understanding queer intercultural communication from the lens of migration. It is assumed that aside from gay men's attitudes and relationships between the dominant heteronormative social and cultural groups in their host countries, they also interact with the individuals in their host countries' sexual minority community. Such interaction with the gay community allows gay men to establish and confirm their identity through self-reidentification. They begin to reidentify themselves and validate their identity in a community that acknowledges and recognizes various queer discourses and practices. However, gay men have to integrate and associate themselves with the culture of the subgroup or the gay community to get a sense of belonging. Their practices, discourses, and behaviors within the sub-cultural community of the host country formed the micro level of social conditions that shape and develop their identity and sexuality.

Gay men's communicative practices of reidentification within the sexual minority community can be viewed as an emancipation from the hegemonic ideologies they experienced in their home countries. The consumption of sex spaces, engagement in sexual activities, and participation in various queer discourses marked their reidentification of themselves. In other words, these various queer practices enabled gay men to recognize, identify, and acknowledge their identity (Ulla and Pernia, 2022). In addition, within the sexual minority community, gay men may find support and acceptance from people who are also members of the gay community. Therefore, integrating themselves into the gay community in their host countries may liberate them, allowing them to get to know themselves and practice queer discourses.

However, it is also important to consider that although gay men may reidentify themselves and acknowledge their “queerness,” they may have to display and follow what the gay community implicitly requires them to be. In other words, they may also struggle to blend with the culture of the gay community in their host countries. For example, they may be required to be discreet, fit, and muscled to attract other gay men within the community for sexual activities. Ulla and Pernia (2022) noted

Being discreet or straight-acting among gay men is a term that is used to describe how gay men behave and present themselves in public or to other groups of gay men. As there are a number of gay men who prefer to date and or have sex with gay men who are discreet or straight-acting, such a behavior or gay self-presentation is commonly prescribed by other gay men, especially if meeting them the first time (p. 10).

Although the gay community in the host country may welcome and support gay men migrants, it is important to note that since they are migrants, they may have to adapt to the culture and embrace the practices to feel a sense of community and belonging. Such culture may become a guiding factor in the “creation, affirmation, reaffirmation, negotiation, and transformation” (Yep et al., 2019, p. 3) of their identity and sexuality in their host countries' sexual minority community. In Ulla and Pernia's (2022) study, highly-skilled Filipino gay men acknowledged that it was only within Bangkok's gay community that they could engage in sexual activities, understand their sexuality, and, most importantly, validate their identity. As a result, they could also recognize and understand their own alter personalities, like being wild, adventurous, dominant, and submissive in sexual activities.

However, it is also important to note that gaining a sense of community and belonging within the gay community does not mean that gay men may have to hide their identity again, as discussed at the macro level. Instead, their “memberships can positively impact well-being through providing a sense of belonging, comfort, meaning, and purpose” (Mitha et al., 2021, p. 750). Unlike on the macro level, where gay men are invisible because of the social institutions that reinforce such invisibility, on the micro level, gay men are acknowledged and recognized. However, they may only have to adapt to the gay community's culture and practices, especially if they want to engage in sexual practices and validate their identity and sexuality within the community. For instance, when one goes to the gay club and engages in queer discourses and practices, everyone knows and is aware within that community that one is gay. Thus, they may have to project the image of an attractive gay man by being fit, muscled, and discreet so they can easily find someone who may find them interesting. As mentioned earlier, since they are gay men-migrants trying to find belonging within the sexual minority community of their host country, they may have to abide by the community's discursive practices.

Given the already present homonegativity, bigotry, and stigma, gay-positive locations play an important role in the life of gay men. These spaces are thought to offer a venue where gay men do express not only their identity but also satisfy their sexual desires, create a community and relax and enjoy with no fear of discrimination.

Generally, gay men's participation and engagement in their host country's gay community can also be viewed as a way to validate their identity. This can be attributed to the fact that they are surrounded by people who may have the same interests and experiences. Gay men may consume some of the commodified gay spaces within the sexual minority community not only to conform to the new cultural environment but also to confirm their identity. It can be argued that such identity validation comes after gay men reidentified themselves at the meso level. Since they are deprived of spaces in their home country that allow them to explore their sexuality, coming to and working in their host country provides them the means to reidentify themselves, validate their identity, and explore their sexuality. By participating in various queer practices within the gay community, gay men can confirm, explore, and understand their sexuality. They are also able “to navigate smoothly [their] queer transitional borderland in-between and in-betwixt” (Eguchi and Asante, 2016, p. 177).

Conclusion

Drawing upon the theoretical frame of queer intercultural communication, this article shows how labor migration becomes an essential means of addressing gay men's financial and personal needs and exploring their sexuality. It also highlights that although a number of studies in the literature have placed interest on culture and cultural differences with a limited focus on LGBTQIA+ people's lived experiences and stories, queer intercultural communication can be examined and understood through the lens of migration by examining the macro, meso, micro levels of social conditions. In this paper, I have proposed the “Queer Emancipatory Migration Framework of Communication” by examining the specific levels of social conditions to provide a deeper understanding of the nuances of queer people's identity and sexuality. I argue that the framework is unique and can be used to advance in theorizing queer intercultural communication. Since the framework examines these three specific simultaneous contexts (macro, meso, micro), it provides a clear understanding of the gay men's migration journey within the Global South, especially from countries whose social institutions incarcerate gay men from emancipation.

At both macro and meso levels, social institutions play an important role in shaping the identity and sexuality of queer people. Most often, the social institutions in queer people's home countries, which include the church, family, schools, and workplaces, may negatively perceive them. These homonegative social institutions limit queer people from participating in various queer practices and discourses, restricting them from identifying their authentic identity and sexuality. Hence, queer people migrate to other places or leave their home countries and seek to belong in other countries, where they can express their sexuality without discrimination. It is assumed that social institutions in gay men's host countries may acknowledge their presence and give them the freedom to explore and understand their identity and sexuality. In addition, these social institutions are vital in emancipating and empowering gay men, which were denied to them in their home countries. Although queer people may have to disidentify and project a dominant social identity, these social institutions can play a crucial role in emancipating marginalized groups of people since they have the power to change the perspectives of the dominant society. At a macro level, the social institutions (church, family, industries) limit queer people from expressing themselves. However, the power of the same and other social institutions (government, media, industries, education) can also unmask and address these prejudices against queer people.

On the micro level, gay men undergo adaptation, assimilation, and integration into their host countries' dominant heteronormative culture, as well as adapt to and practice the culture of the sexual minority community. Not only do they adapt, assimilate, and integrate themselves into their host country's dominant society, but they also do the same to a particular subgroup, the gay community. Integrating themselves into the sexual minority community allows them to explore and understand their sexuality and identity.

Therefore, in pushing forward queer intercultural communication as a theoretical construct, particularly in migration, consideration must be placed on queer people's experiences. Their experiences may have been influenced by the social institutions in their home and host countries. Likewise, their perspectives of who and what they are may also change as they get validation from their engagement in the sexual minority community. Thus, queer intercultural communication from the lens of migration can be done by examining the macro, meso, and micro levels of social conditions and queer people's adaptation and integration into the new cultural environment, uncovering the various social, historical, and structural conditions of inequality, prejudices, and biases against them. These three levels of examining queer intercultural communication provide an in-depth understanding of the migration decision, ways of integration, and emancipation among gay men. Looking only at one aspect of queer intercultural communication would result in an incomplete understanding of the theory and blurs the chance for queer people to become visible in society. Thus, queer intercultural communication studies must highlight the experiences of oppression, emancipation, and empowerment among the marginalized LGBTQIA+ community in various social institutions.

Author contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Acknowledgments

I wish to acknowledge and thank Celeste C. Wells for helping me improve the paper.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^Although the term “queer” is used to refer inclusively to all LGBTQIA+ people whose rich and colorful lives, experiences, and stories are grounds for knowledge production in theorizing queer intercultural communication, I used the term ‘queer' to refer specifically to gay men in this article.

2. ^Association of Southeast Asian Nations (Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam).

3. ^Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development.

References

Babar, Z., Ewers, M., and Khattab, N. (2019). Im/mobile highly skilled migrants in Qatar. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 45, 1553–1570. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2018.1492372

Bailey, A., and Mulder, C. H. (2017). Highly skilled migration between the Global North and South: gender, life courses and institutions. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 43, 2689–2703. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2017.1314594

Barron, I. M., and Frost, C. (2018). “Men, boys, and LGBTQ: invisible victims of human trafficking,” in Handbook of Sex Trafficking, eds L. Walker, G. Gaviria, and K. Gopal (Cham: Springer), p. 73–84. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-73621-1_8

Chávez, K. R. (2013). Pushing boundaries: queer intercultural communication. J. Int. Intercult. Commun. 6, 83–95. doi: 10.1080/17513057.2013.777506

Cheah, W. H., and Singaravelu, H. (2017). The coming-out process of gay and lesbian individuals from Islamic Malaysia: communication strategies and motivations. J. Intercult. Commun. Res. 46, 401–423. doi: 10.1080/17475759.2017.1362460

Cornelio, J., and Dagle, R. (2022). Contesting unfreedom: to be queer and christian in the Philippines. Rev. Faith Int. Aff. 20, 27–39. doi: 10.1080/15570274.2022.2065804

De Guzman, M. T. (2020). The L Words - Lesbian and Labor: Physical and Social Health Impacts of Call Center Work on Lesbian Women in Quezon City, Philippines. Philipp. J. Soc. Dev. 13, 1.

Department of Foreign Affairs (DFA). (2019). Distribution on Filipinos overseas. Philippines: DFA. Available online at: https://dfa.gov.ph/distribution-of-filipinos-overseas (accessed March 16, 2022).

Eguchi, S. (2021). On the horizon: desiring global queer and trans* studies in international and intercultural communication. J. Int. Intercult. Commun. 14, 275–283. doi: 10.1080/17513057.2021.1967684

Eguchi, S., and Asante, G. (2016). Disidentifications revisited: queer(y)ing intercultural communication theory. Commun. Theory 26, 171–189. doi: 10.1111/comt.12086

Gambino, E. (2020). “A more thorough resistance”? Coalition, critique, and the intersectional promise of queer theory. Polit. Theory 48, 218–244. doi: 10.1177/0090591719853642

Harkins, B., and Lindgren, D. (2017). “Labour migration in the ASEAN region: assessing the social and economic outcomes for migrant workers,” in Presented at the Migrating out of Poverty: from Evidence to Policy Conference' in London.

Huang, S. (2021). Why does communication need transnational queer studies? Commun. Crit. Cult. Stud. 18, 204–211. doi: 10.1080/14791420.2021.1907850

Human Rights Watch. (2017). “Just let us be” discrimination against LGBT students in the Philippines. Available online at: https://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/report_pdf/philippineslgbt0617_web.pdf (accessed March 16, 2022).

Hur, H. (2020). The role of inclusive work environment practices in promoting LGBT employee job satisfaction and commitment. Public Money Manag. 40, 426–436. doi: 10.1080/09540962.2019.1681640

Jackson, P. A. (1995). Thai Buddhist accounts of male homosexuality and AIDS in the 1980s. Aust. J. Anthropol. 6, 140–153. doi: 10.1111/j.1835-9310.1995.tb00133.x

Langarita Adiego, J. A. (2020). Sexual and gender diversity in small cities: LGBT experiences in Girona, Spain. Gender Place Cult. 27, 1348–1365. doi: 10.1080/0966369X.2019.1710473

Manalastas, E. J., Ojanen, T. T., Ratanashevorn, R., Hong, B. C. C., Kumaresan, V., Veeramuthu, V., et al. (2017). Homonegativity in Southeast Asia: attitudes toward lesbians and gay men in Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam. Asia-Pac. Soc. Sci. Rev. 17, 25−33.

Martinez, O., and Kelle, G. (2013). Sex trafficking of LGBT individuals: a call for service provision, research, and action. Int. Law News 42,1−6.

Maulod, A. (2021). Coming home to one's self: Butch Muslim masculinities and negotiations of piety, sex, and parenthood in Singapore. J. Homosex. 68, 1106–1143. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2021.1888584

Mitha, K., Ali, S., and Koc, Y. (2021). Challenges to identity integration amongst sexual minority British Muslim South Asian men. J. Community Appl. Soc. Psychol. 31, 749–767. doi: 10.1002/casp.2527

Okada, T. (2022). Gender performance and migration experience of Filipino transgender women entertainers in Japan. Int. J. Transgend. Health 23,24–35. doi: 10.1080/26895269.2020.1838390

Oosterhoff, P., and Hoang, T. A. (2018). Transgender employment and entrepreneurialism in Vietnam. Gend. Dev. 26, 33–51. doi: 10.1080/13552074.2018.1429102

Presto, A. (2020). Revisiting intersectional identities: voices of poor bakla youth in rural Philippines. Rev. Womens Stud. 29, 113–146.

Reza, M., Subramaniam, T., and Islam, M. R. (2019). Economic and social well-being of Asian labour migrants: a literature review. Soc. Indic. Res. 141, 1245–1264. doi: 10.1007/s11205-018-1876-5

Rodriguez, F. I. (1996). Understanding filipino male homosexuality. J. Gay Lesb. Soc. Serv. 5, 93–114. doi: 10.1300/J041v05n02_05

Sanders, D. (2019). Thailand and “diverse sexualities”. Aust. J. Asian Law 20, 1–21. doi: 10.3316/informit.067184826793387

Shrestha, M., Boonmongkon, P., Peerawaranun, P., Samoh, N., Kanchawee, K., Guadamuz, T. E., et al. (2020). Revisiting the “Thai gay paradise”: negative attitudes toward same-sex relations despite sexuality education among Thai LGBT students. Glob. Public Health 15, 414–423. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2019.1684541

Tamagawa, M. (2018). Coming out to parents in Japan: a sociocultural analysis of lived experiences. Sex. Cult. 22, 497–520. doi: 10.1007/s12119-017-9481-3

Tang, X., and Poudel, A. N. (2018). Exploring challenges and problems faced by LGBT students in Philippines: a qualitative study. J. Public Health Policy Plann. 2, 9−17.

Ulla, M. B., and Pernia, E. E. (2022). Queering the labor migration: highly-skilled Filipino gay men as labor migrants in Bangkok, Thailand. Cogent Soc. Sci. 8, 2051816. doi: 10.1080/23311886.2022.2051816

Wimark, T. (2016). Migration motives of gay men in the new acceptance era: a cohort study from Malmö, Sweden. Soc. Cult. Geogr. 17, 605–622. doi: 10.1080/14649365.2015.1112026

World Economic Forum. (2021). Global Gender Gap Report 2021. Available online at: https://www.weforum.org/reports/global-gender-gap-report-2021 (accessed March 16, 2022)

Yep, G. A. (2013). Queering/quaring/kauering/crippin'/transing “other bodies” in intercultural communication. J. Int. Intercult. Commun. 6, 118–126. doi: 10.1080/17513057.2013.777087

Keywords: global south, identity, queer intercultural communication, queer migration, sexuality

Citation: Ulla MB (2022) Queer intercultural communication in migration: Perspectives and future directions. Front. Commun. 7:994605. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2022.994605

Received: 15 July 2022; Accepted: 12 September 2022;

Published: 04 October 2022.

Edited by:

Diyako Rahmani, Massey University, New ZealandReviewed by:

Celeste C. Wells, Boston College, United StatesCopyright © 2022 Ulla. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mark B. Ulla, bWFyay51bEBtYWlsLnd1LmFjLnRo

Mark B. Ulla

Mark B. Ulla