- 1Dakota State University, Madison, SD, United States

- 2Independent Scholar, San Francisco Art Institute, San Francisco, CA, United States

This article expands on previous scholarship on the choreographic practice of marking by studying two disparate communities—community-based dance makers and arborists—who collaborate to create a large-scale, public dance performance. With the dance company's goal being to bring public awareness to the embodied skillfulness of the city's urban forestry department and the impacts these city workers have on the community green spaces they service, the dancers for the performance are the foresters themselves who enact dancerly versions of their professional movements. We analyzed 21 h of videotaped data of dance rehearsals, proffering up an interaction-based approach to the study of marking, analyzing the moment-to-moment way, both groups mark out dance phrases for a sub-section of the final performance: the brush truck routine. In doing so, we develop the term marking together to denote how dance ideas are built, transformed, and enacted through group idea formation and revision. Ultimately, we provide insights into how to study dance marking in its full, interactional complexity.

Introduction

The dance creation process is a creative, co-constructed endeavor between the choreographer(s) and dancers that requires a great deal of bodily semiosis. Although dance creation, depending on the genre of dance, the studio/company, and the individuals involved, may shape the idiosyncrasies during the process, the choreographer-dancer interaction is typically one of mutually shared intelligibility of dance vocabulary. There, however, are instances where dance practitioners partner with communities in a collaborative form of dancemaking, often involving people from the respective community they work with who do not necessarily identify as dancers. One instance of this, known more broadly as community-based art, is a form of collaborative artmaking (see Cohen-Cruz, 2005 for history and varieties) that seeks to feature personal stories and lived experiences that are intertwined with the said community; the community knowledge, skills, and competencies are invaluable and unique sources of site-specific meaning-making that are often addressing local concerns. When choreographers create a large-scale performance involving community members who are not trained in dance vocabulary, the artistic vision is necessarily driven and shaped by the confines of their locality and community knowledge. This has immediate consequences for dancemaking: shared intelligibility regarding crafting and interpreting the dance being created requires creative communication and negotiation to reach an understanding and appreciation without any shared referential history.

In this article, we looked at just that: the dance creation process and practices between two disparate groups, the dance company Forklift Danceworks focused on community-based artmaking and arborists of Austin's Urban Forestry Division. The two groups, together with the neighborhood and community partners, created a story tethered to the local community (the Govalle-Johnston Terrace neighborhood in Austin, Texas) within a public park setting involving and recognizing the importance of municipal park maintenance, titled (Forklift Danceworks, 2015). They simultaneously fulfilled a symbolic and functional role by incorporating the arborists as the dancers (or worker-actors) to perform regular work tasks in organized dance form.

The arborists, being skilled workers who specialize in aspects of environmental science, horticulture, and urban forestry, make dance creation possible; they bring their entrained and enacted professionalized vision (Goodwin, 1994, 2017) and bodily intuition (Harper, 1992) to bear on whether the dance creation process adheres to safety and logistical concerns, reaching creative compromises with the choreographers. Through ethnographic methods, the choreographers learn about the day-to-day tasks of preserving urban green spaces and the technical knowledge needed to maintain such standards. Shadowing the workdays of the arborists enables the choreographers to start thinking about their movements, competencies, and environments in artistic ways, such as their utility in dance phrase creation that holds a fair amount of creative potential and logistic stability. Over time, featuring deeply engrained professionalized knowledge, skills, and intuition and fitting these forms of expertise to artistic needs requires the arborists and choreographers to develop makeshift terminology within and through communication, talk, and gesture playing a vital role.

In working with the choreographers and their artistic vision, the arborists become partially socialized into dancerly ways of thinking and organizing their bodies and tools. On the flip side, the artists partially become socialized into the professional habits and ways of seeing the world as an arborist. The back-and-forth between these two communities helps them progress in the shared goal of creating an informative and aesthetically pleasing performance for their community audience. However, the different form of knowledge and experience means that the two communities need to establish a choreographic arena that lends itself to the dance creation process and encourages the shaping of artistic ideas while circumventing some limitations they face. How do the choreographers and arborists navigate such contingencies?

In studying the choreographer-arborist interactions, we observed that, for these two groups, an appropriate place and time to manage many of these contingencies is during rehearsal session interactions. These face-to-face meetings allow the choreographers and arborists to develop a workable conceptual space for enacting, visualizing, and experiencing routines (as the choreographers generated these routines from past actions of the arborists) and modifying, subtracting, or adding to a dance phrase in its entirety. Talk and gesture are rich depictive communication resources (Clark, 2016, 2019) for helping foster a workable or shareable image, bridging the divide between a subjective and, perhaps, specialized vision to objective and perceivable public image. To make a dance idea tangible enough to both parties, it needs to be publicly augmentable (we mean this both in the sense of one's mental simulation and the physical material surrounding in sight) despite having differing relations and knowledge of what arborists do and how it affects urban green spaces. To create movement phrases (rhythmic, spatialized oriented, and timed choreographic structures)–especially when it involves machine and tool use of the arborists (chainsaws, brush trucks, and pole saws) and intimate knowledge of plant ecologies–they need to resolve emergent choreographic problems. Problems, such as whether two brush trucks can actually work together in a coordinated manner (synchronization) or how much time felling a tree in real-time would take vs. its choreographed rendition, raise coordination, feasibility, and cohesion concerns. The rehearsals go through many iterations. The choreographers pare down a dance phrase and the routine into what is essential and most expressive, not only for their own sake but also clearly understandable for onlookers. Eventually, the problems become more manageable while simultaneously tightening or solidifying the routine. Rehearsals become more fluid, and the two groups are quick to fix all these issues and move on to committing things to memory with repetition and practice with the actual forestry equipment and machinery.

This choreographic situation draws our scholarly attention because it is where dance creation and gesturing-for-dance are made perceivable in situ. When the choreographers and arborists work together to solve and foresee problems, further pre-existing dance routines, or create new suggestions entirely, they do so via a specific mode of depictive communication that art practitioners and scholars refer to as marking (see Kirsh, 2011). “When dancers mark,” Kirsh writes from a cognitive ethnographic account of dance, “they execute a dance phrase in a simplified, schematic or abstracted form… When marking, dancers use their body-in-motion to represent some aspect of the full-out phrase they are thinking about. Their stated reason for marking is that it saves energy and avoids strenuous movement, such as jumps. Sometimes, it facilitates the review of specific aspects of a phrase, such as tempo, movement sequence, or intention, all without the mental and physical complexity involved in creating a phrase full-out. It facilitates real-time reflection” (p. 179). Across several studies, (Kirsh et al., 2009; Kirsh, 2010a,b, 2011, 2012) demonstrate that the act of abbreviating already established dance movements is for efficiency, to reserve energy, and summarize or altogether bypass specific steps (usually inconsequential to the point trying to convey and therefore more easily mastered) until reaching a point where more complex marking needs to be slowed down to emphasize organizational issues.

Likewise, dance scholar Warburton (2011, 2014, 2017), Warburton et al. (2013) has advocated exploring the many cognitive and kinesthetic benefits of marking as dance enaction. Warburton (2011) writes, “The activity of dance marking not only allows for subjectivity to be accessible through the perceptual appearance of physical body ‘movement reductions,' but it also can account for the workings of both on-line and off-line cognitive (and emotional) processes simultaneously. The marking dancer is moving and thinking explicitly in real time, at the same time using small hand gestures and her implicit memory to prime in correct sequence a 'turning' motor program by taking it off-line. But ultimately, marking is 'for' expression, not faster information processing” (p. 77). For Warburton (2014), marking is a form of notation-in-action: dancers make these scaffolded notations publicly available and transform them in real-time (also see Warburton et al., 2013; Warburton, 2017).

It is evident in dance-oriented scholarship that marking is not unidimensional. First, marking is a form of gesturing-for-dance where dance phrase movements are externalized and brought into the realm of public semiosis; either one marks solo or in groups (Kirsh, 2011; Warburton, 2017). Second, the heterogenous marking practices are carried out to accomplish various socio-cognitive aims, serving as a mode of recalling, reflecting, remembering, theorizing, showing, spatializing, emulating, and coordinating dance phrases (see Muntanyola-Saura and Kirsh, 2010). Third, mark-making is, to borrow Clark and Gerrig's (1990) notion regarding demonstrations, a selective depiction that illustrates varying dimensional qualities and their interactions in a dance phrase, such as duration, emphasis, tempo, time, rhythm, synchronicity, and sequentiality. Finally, marking involves varying degrees of semiotic complexity (Bressem et al., 2018), ranging from using only hand gestures to fully embodied: choreographers and dancers in our data, for instance, can use their hands, head, and body to emulate distinct movements or actions of the arborists, including felling a tree with a chainsaw or picking up brush with trucks.

Our focus, then, is on a relatively overlooked type of mark-making, what Kirsh (2011) refers to as “When marking is used as a tool for communication” (p. 180) that involves clearly depictive gesturing. We elaborate on this idea by seeing marking communication that involves multiple actors, multiple bodies, and elaborate scaffolded ideas with accompanying visual and kinesthetic imagery: marking together. In group choreography, the purpose of marking is to mark with dancers. It is a performative action not in conjunction with a group but proposed for the group to provide an “abstracted structure” (Kirsh, 2011, p. 190) or generalized example of a particular movement or demonstration of a problem that needs refinement. The abstracted structure makes it possible to imprint some speculative projection (an externalized image or version) that becomes, as Kirsh (2010a,b, 2011) argues, augmented reality for shared imagery. With these scholars' ideas in mind, we will demonstrate how marking for timing, spatial orientation, synchronization, and audience visualization, among other qualities, is a form of co-speech gesturing-for-dance creation.

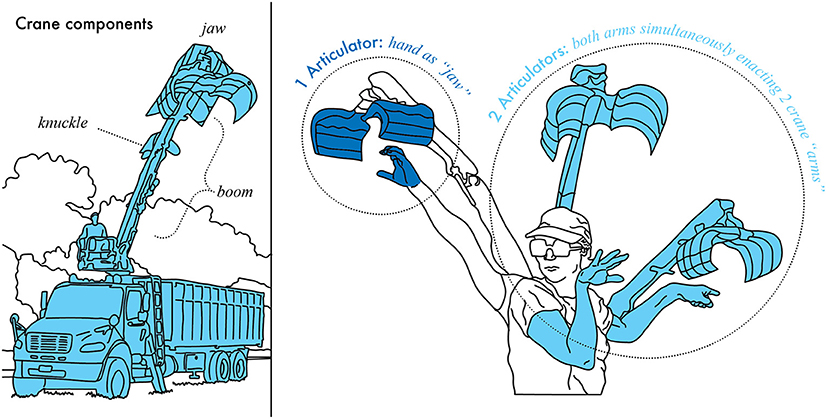

Taking up a micro-interactional approach (see Materials and Methods) to the marking practice of mark-making, we explore the moment-to-moment analysis of marking as it unfolds, not in one gesture but a series of multisensory acts across interactional sequences and collaborative moments of dance co-creation made perceptible in gesturing-for-dance. Specifically, we trace examples of marking together across one routine: a dance using brush trucks. The marking moments we analyze in this article involve the choreographers and arborists physically emulating the movement qualities of the brush trucks (or grapple trucks): movements of the mechanical jaw/claw, positioning of the truck body and dump box, and extensions of the knuckle boom crane (see Figure 1). Central to this complex interaction is the ability to imagine [borrowing Murphy (2004, 2005) notion of imagination made visible in public discourse] a routine in the here-and-now discourse moment, even if that routine is not being practiced with the actual machines or tools that will be included later but not at that moment; instead, the two groups' bodies serve as an abstracted, mediated channel of communication for makeshift augmentation in a virtual space (a space created for art symbolization and perception) artistically rendered (Langer, 1953; Kirsh, 2011). In our analysis, we will use the term brush truck to reflect the term used by the choreographers and foresters.

Cognition-centered accounts are apt at attending to why choreographers and dancers mark, explaining how cognitive operations such as projection, imagination, and perception (See Kirsh, 2010a,b, 2011) are intertwined. We, however, want to expand those works by illustrating what an interaction-based account can add to the scholarship, especially when we look at a markedly different context: two groups, choreographers and arborist-dancers, trying to bridge cultural and expertise gaps in embodied knowledge. It is also a context where, as we plan to show, marking takes on an interactional role that is highly collaborative and essential to any progress in the dance creation process. And in the process of our analysis, we will weave together notions of gestural depiction, publicly available imagination, and multisensory semiosis as they are relevant via mark-making during dance rehearsal sessions. Our article, therefore, unfolds in the following way:

1. First, we provide a detailed narrative that describes our data, methods, and materials. In this section, we carefully trace our inductive, interaction-based methods for studying marking and the iterative stages in the research process.

2. Second, analyze several interactional snippets (shown in detailed multimodal transcripts) involving the community-based dancers and the arborists marking out aspects of one routine involving the brush trucks. Our analyses in this section detail an account of the various ways marking-making can be used to communicate knowledge between these groups. In turn, we develop a notion called marking together.

3. Finally, we address how this inductive analysis of videotaped data, as informed by microethnography (detailed in the section below), expands contemporary scholarship on marking and the analytic purchase of our notion of marking together as it creates new trajectories for research.

Materials and methods

Data

For this micro-ethnographic project, the principal investigator (one author of this article) recorded and participated in interactions between two groups: a dance company, Forklift Danceworks, and Austin, Texas' Urban Forestry employees. The culmination of the collaboration between the two groups resulted in a large-scale performance piece: (Forklift Danceworks, 2015).

Community-based dancemakers, Allison Orr, the Founder and Director of Forklift Danceworks, and Krissie Marty, Associate Artistic Director and Community Collaborations Director, in conjunction with other team members, shadowed the arborists in their day-to-day work, solicited personal stories, interviewed members of the Urban Forestry Division, and derived artistic potentialities from the movement vocabularies made evident in these ethnographic, iterative steps. The premise of the performance using previously untrained dancers on park grounds and operating workday machines is to maintain the authenticity of their professional skill sets and knowledge while telling a narrative about how these workers affect their community's green areas. Alternatively, those artistic concepts examine the customary societal valuation of art and municipal work present in the arborist dances to propose an alternative viewpoint for the unification of understanding of how these cultivated spaces affect the city's citizens. The dance phrases for the performance exemplify several skills and actions of the foresters and their specialized knowledge of using different machines for maintenance. They are crafted only through back-and-forth collaboration and learning from one another. While formulating the order of the performance, the choreographers investigated commonly used forestry equipment and tools. For this article, we focus only on the brush truck routine.

Video recordings for this dataset occurred over a year and a half and comprised 21 hours of footage. The dataset includes videos of:

• the choreographers recorded as they observed the everyday work activities of the foresters.

• the choreographers scouting out actions and practicing dance phrases.

• the principal investigator attending the rehearsal and practice sessions across the entire dance performance videos. This also includes videos of the choreographers working with other organizations and their music, stage, and safety/logistics team.

• the public performances.

• post-performance interviews.

The principal investigator recorded video and audio using the following equipment: Canon XF105 HD Professional Camcorder, Zoom Q8 Handy Video Recorder, two Sennheiser EW G3 Wireless Lavalier microphones, a Sennheiser MKE 400 camera-mount shotgun microphone, and a monopod. Recordings occur in various settings, including urban parks, a music studio, the dance company headquarters, and the urban forestry division workspaces. The choreographers and foresters all attended an introductory session detailing the principal investigator's role as a researcher and the data to be collected. The principal investigator provided consent forms to participants, and only those who consented were recorded. For this study, participants were allowed to anonymize their names to protect their identities. We requested and were given permission to openly reference Forklift Danceworks and include the actual names of the choreographers. However, as stipulated in my consent forms, we kept the city workers-performers names anonymized, as their relation to public life differs from that of the publicly available dance company. You can learn more about Forklift Danceworks, the Urban Forestry Department, and their co-partnerships at (Forklift Danceworks, 2015). The Institutional Review Board approved the study at the University of Texas at Austin, IRB Number: 2014-09-0120.

Microethnographic analysis of marking

Interactional approaches to the study of social life go by various related names, modes of analysis (microanalysis, conversation analysis, microethnography, among others), and interconnected traditions that share a common aim to study social interaction as it is documented in recordings. Though these, often qualitative, approaches may differ in the scale and level of detail in how moment-to-moment interactions are analyzed, for our purposes, we will refer to our approach as a microethnographic investigation (See Streeck and Mehus, 2004): the systematic study of talk and bodily action in their consequential structures and patterned trajectories as informed by ethnographic interactions with the communities involved. The work of applied linguist heavily inspires our project, Goodwin (2017), who spent his lustrous career integrating micro-interactional perspectives with ethnographic methods to understand how communities develop and enact profession-specific knowledge in interpreting social contexts and use of communicative resources. In our analysis, we will use Goodwin's (2013, 2017) notions of co-operative action and semiosis to refer to the ways action is accumulatively built and transformed in interaction.

In this vein, our study takes a microscopic, interaction-based approach to the study of dance rehearsal sessions, focusing on the dance practice of marking. The way we collected, organized, analyzed, and displayed our information was drawn from several qualitative, social interaction research guides on conversation analysis, interactional linguistics, and video-based studies (Bavelas, 1987; Heath et al., 2010; Reed, 2010; Hepburn and Potter, 2021). Below, we sketch out our research trajectory and processes, breaking these iterative phases into stages:

Preparation

Engaging with the choreographers and arborists, the data collection involved gathering as much videotaped data as possible and shadowing the groups working together. This led to recordings revolving around rehearsal sessions with various specialized forestry equipment: brush trucks, water trucks, chainsaws, pole saws, loader trucks, and other maintenance tools. Video recordings were time-stamped for dates, times, and locations and then organized by the type of rehearsal activity, whether it involved chainsaws, brush trucks, or combinations. Initial viewings of the recordings led to observations that the choreographers and arborists needed to establish a shared understanding and intelligibility to create a production out of the arborists' professional movement vocabulary, machine use, and community maintenance.

Discovery

Together, we watched the entire dataset, noting observable patterns across the different rehearsal sessions; the differences varied between the size of participants, types of machinery, locales, and the goals they hoped to achieve in each session. Of these patterns, one theme emerged consistently; the choreographers lacked specialized knowledge of the foresters, and the foresters, who lacked technical knowledge of choreographic or artistic practice, needed to collaborate to learn from one another. The process involved generating choreography derived from the local movement vocabularies of the arborists and transforming them–somewhat improvisationally–into verb-like actions that can be easily shared between parties (see Orr, 1998 for the earlier articulation of her typical choreographic process). This had to be negotiated collaboratively to solve potential problems or emerging contingencies. As we watched and re-watched these rehearsal interactions, we noticed the choreographers resorted to bodily marking in the early stages of dance routine creation (Kirsh, 2011). Marking is a choreography practice that involves abstracting qualities or characteristics of dance phases and formulating them through the body in a particular, abbreviated form. In the earliest stages of dance rehearsals, we established a baseline intuition that marking is necessary when first launching the dance routines within the confines of mechanistic capability. We also had an inclination that this was a communicative tool for translating experience and understanding between the two groups.

Classify

Establishing that marking appeared to be a widespread phenomenon for problem-solving between the two groups, we created a collection of “marking moments” across the entire dataset. We observed similar uses of hand marking across routines; however, what was abstracted and the degree of the abstraction with the hands depended on the type of machinery or actions being done. Whereas the choreographers could easily abstract the handsaws, there was little potential or necessity to schematize more detailed hand movements as the routine became streamlined or required more minute changes. Zeroing in on one routine, in this case, the brush trucks, was helpful in our analysis for several reasons:

• The routine involved substantive problem-solving between the two groups.

• There is a good deal of semiotic complexity (Bressem et al., 2018) and mechanical elaborateness (the arm and human body can easily be imagined as if they were parts of the truck).

• And in the recordings, we could observe the gamut of changes to the dance routine and the spectrum of dance creation to the actual practicing of the performance.

Analyze

After creating and analyzing our collection of “marking moments,” we transcribed selected segments of these instances to engage in a deeper analysis. Although transcription methods vary, we adopted standard conversation analytic conventions for talk (Jefferson, 2004; Reed, 2010) and bodily action (Goodwin, 1990) to understand collaborative marking practices' sequentiality, positioning, and unfolding nature. In conversation-analytic scholarship, a good deal of consistency in transcription conventions for talk, the temporal and spatial coordination of gestural actions can be represented in various manners to fit the analytic concerns and the contextual details.

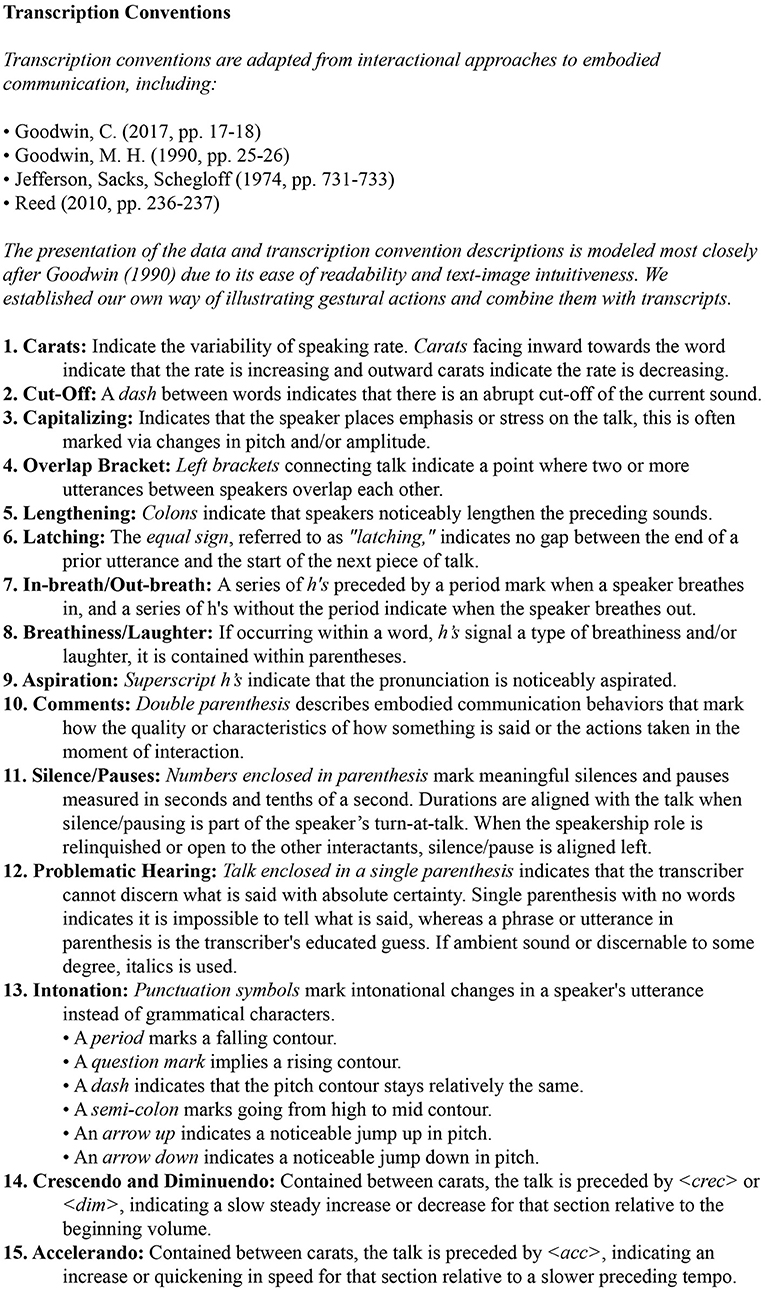

To grasp how we transcribed the segments analyzed in this paper, we provide an illustrated guide to our transcription conventions and explain each symbol alongside its purpose (see Figure 2).

The empirical analysis process in interaction-based studies requires testing and confirming the investigator's analyses of these snapshots of social life. Therefore, throughout the entire process, we tested our interpretations with formal and informal data sessions (see Hepburn and Potter, 2021, p. 19; Heath et al., 2010, pp. 102–103 and 156–157 for resources and tips on data sessions) conferences to confirm, expand, and solidify those hypotheses with others who study spontaneous social interactions (fields such as embodied communication, interactional linguistics, linguistic anthropology, and gesture studies).

Results

In this section, we lay out several interactional snippets in chronological order because it exemplifies the cumulative stages of dance creation (see Kirsh et al., 2009 on novel dance creation) to the performance. Reviewing examples across time in the development of dance phrases draws out the accumulative, co-operative power of human action (cf. Goodwin, 2013, 2017); the choreographers and arborists establish a rich form of semiosis, that is, a form of gesturing-for-dancing and a movement vocabulary that helps them conceptualize dance phrases and rework them in conversation. Dance phrases for the final public performance required the two groups to bridge gaps in knowledge and overcome certain contingencies.

• The choreographers wanted the arborists to enact their own embodied knowledge, intuition, and skilled repertoires as foresters. Still, there were expressive limitations since the arborists are learning to think in a dancerly mindset, and the machines are being repurposed for artistic expression. The arborists learn in-situ how to think in a choreographic fashion, consider new ways of organizing their machines and their bodily skill sets, and even anticipate and suggest artistic potential.

• The arborists faced limitations and constraints in several capacities regarding their participation. Their availability was particularly limited because they worked early morning hours and had to be onsite; therefore, there was a substantial amount of day-to-day, week-to-week negotiation with the urban forestry department. The choreographers worked carefully with the Urban Forestry Department to secure approval and follow machine operation protocol and safety guidelines.

• The dance company's goal is to highlight the value of this municipal work as it is embedded in an urban community; hence, limitations in time or ability to get specialized certifications by the choreographers were left to the arborists to fulfill. The choreographic process and ultimate product, the public performance, required the choreographers to be highly mindful of the dance routine timing, ensure proper alignment of routines to music, and follow regulatory guidelines for safe audience engagement. They could do so through ethnographic observations and participation with the arborists. These processes demonstrate how contingencies and epistemic gaps shape dance phrase creation, maintenance, or alteration. One primary way these groups interacted and accomplished establishing dance phrases for their routines is through the one joint space that was easy to create: the abstracted, interactive, and imaginative spaces made possible with their bodily gestures and talk. Marking together, a term we develop in the interaction examples below, provides insight into how two seemingly disparate professional communities can co-construct, revise, and enact dance ideas (Yasui, 2013) in real-time with and through bodily thinking and collaborative imagining (cf. Murphy, 2004, 2005).

Marking together as a form of professionally informed artistic idea creation

The dance routine, at this stage, is relatively new. The dance company's Founder and Artistic Director, Allison, worked with the arborists by herself to establish the routine. In our first set of examples (Transcripts 1.1–1.3), the Associate Artistic Director, Krissie, works with two arborists, Antonio and Roy, to refine a previously rehearsed routine. In this segment, we observe an earlier stage of the routine-creation process: the choreographers and arborists develop a catalog of movement and coordinated dance possibilities. Brush truck mechanical jaw and crane motions are posited from a choreographic viewpoint to be accepted and added to a list of options or adjusted based upon arborists' logistical set of limiting parameters.

During this stage of the dance phrase creation process, the choreographers and arborists exchange professionally informed ideas to negotiate a routine's efficacy and artistry. They must establish a curated set of embodied vocabulary, where the arborists edit the proposed ideas from the choreographers before enacting legitimized ideas. This context differs significantly from a typical choreographer-dancer interaction; the two groups use their own bodies in place of the brush truck components to negotiate these dance phrases and intermittently practice with the actual machinery. They mark dance phrases by acting as symbolic stand-ins for the brush trucks. When marking, the two groups have a different kinesthetic relation, and appreciation for how the actual moves gestured through the body will translate to full-out practice with the machines. The brush truck booms, knuckle, and jaw are likened to the human arm, elbow, and hand. Mimetic enactments, as many scholars who have studied it concerning the gesturing body (see Calbris, 1990, 2011; Donald, 1991, 2001; Streeck, 2008, 2009; Müller, 2014) have found, involve our ability to imaginatively (re)-produce actions or model our perceptional experiences in an objectified form that is imaginable and perceivable to others.

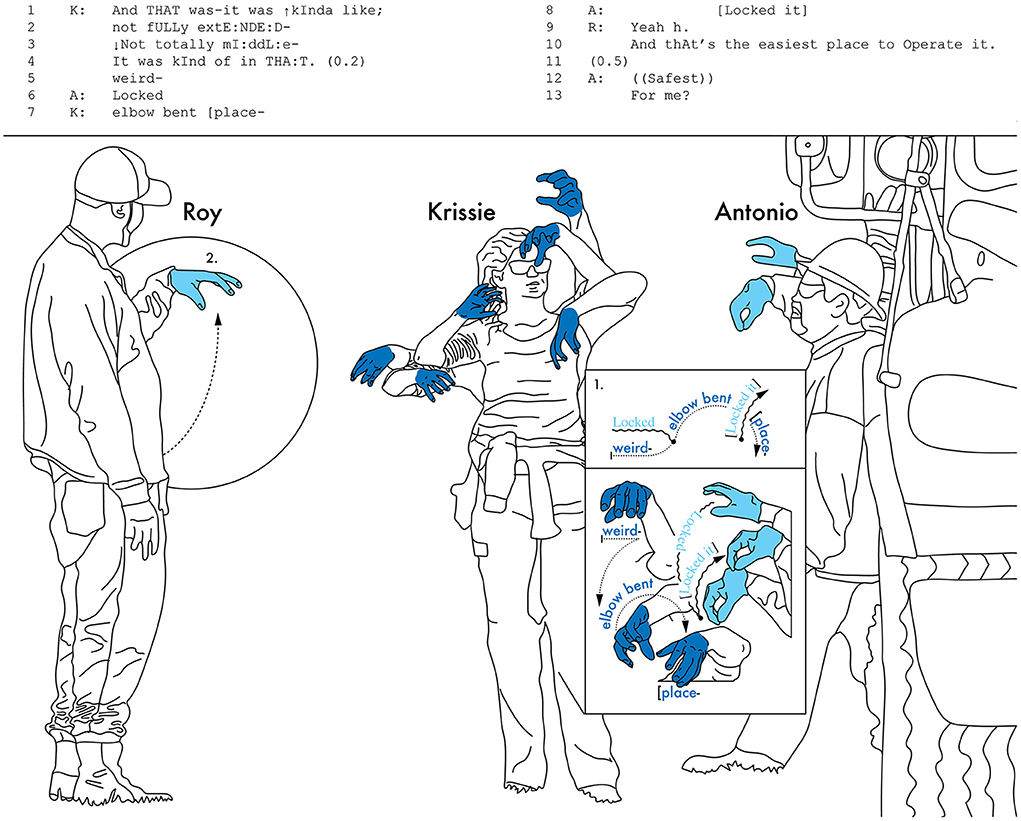

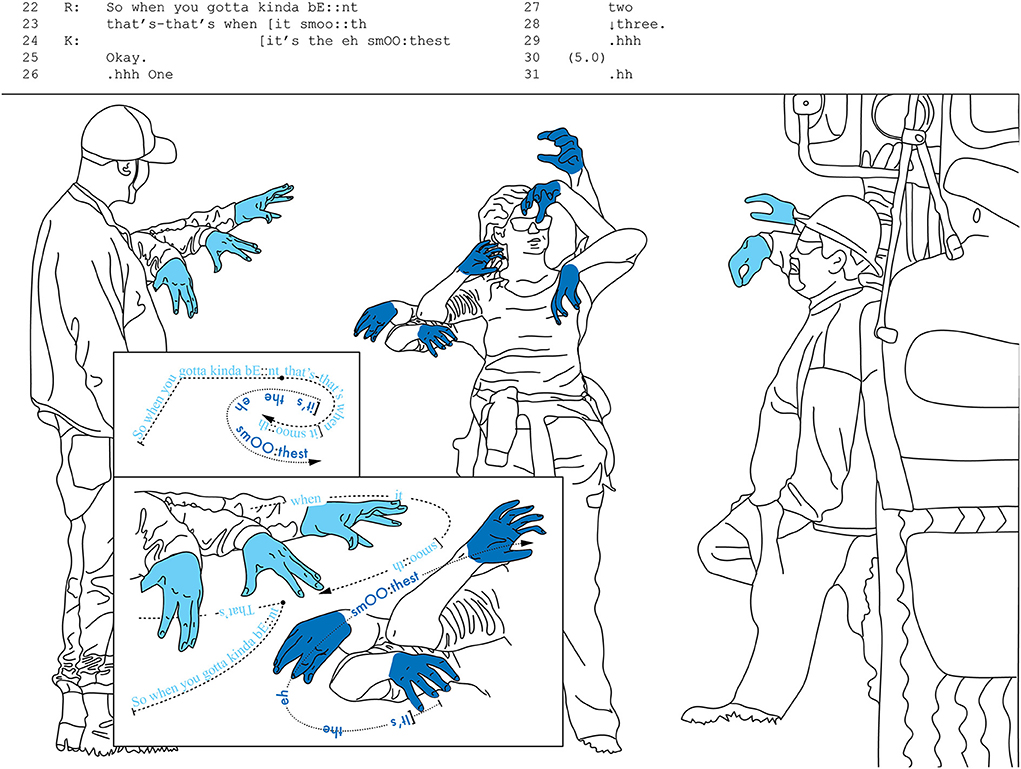

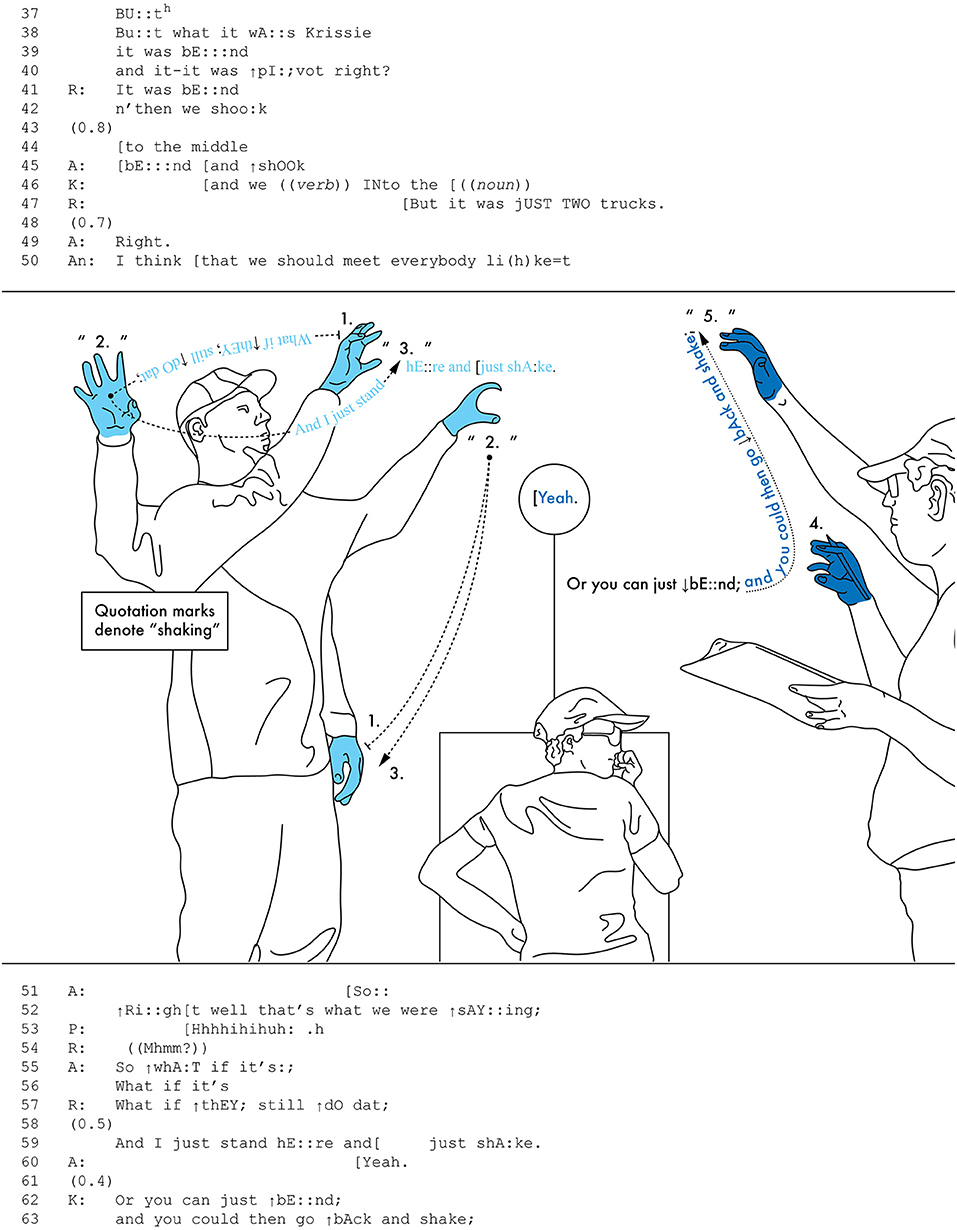

Days prior, Allison (not in this interaction) established some basis for a brush truck routine with the arborist. In Transcript 1.1, the brush truck routine is at a point of being a work-in-progress; the arborists alternate between operating the actual brush trucks and negotiating possible changes to the dance version of their work with their bodies and the choreographer. Krissie, who was not present, has access to a video of the rehearsal and notes; therefore, she runs through the routine with the arborists to fully grasp the elements of dance phrases. As she's talking through each step of the dance phrase, she tries to describe and illustrate by marking a specific positioning of the boom and the claw. The marking activity in this interaction is very much a confirmation-seeking one for Krissie; it serves as a embodied reminder of the artistic ideas being developed (see Figure 3).

In Transcript 1.1, Krissie discerns a particular position of the crane boom; however, she is not generating fitting terminology, so she turns to the arborists for elaboration. Krissie uses three distinct arm/boom extensions pitched to the arborists so that they can co-articulate the specific actions she's trying to name. Her differentiating gestures–gestures that show the height of the crane extended and claw position–and co-occurring level pitch intonations work synchronously to contextualize the goal of the activity to secure feedback and confirmation from the arborists. One of those insights immediately gleaned from this part of the exchange is that there is a more technical vocabulary for describing the position Krissie is trying to articulate, one that, Antonio reminds her, is a “locked” position (Lns. 6 and 8). Reminiscence of a word-search activity (Goodwin and Goodwin, 1986), Krissie brings forward a three-part contrast seeking feedback: “And that was-it was kind like not fully-extended, not fully-middle,” or a “weird locked elbow-bent place” (Lns. 1–7). As she is enacting this three-part illustration, Krissie carefully looks between Roy and Antonio for elaboration and definition of her suggestion. Antonio takes his turn as Krissie's role as arena-maker is relinquished to her satisfaction. When Krissie says “weird [locked] elbow-bent place” (Lns. 4–5 and 7), Antonio nods, looks at Roy, back to Krissie, and then presents his understanding in the form of a verbalized concept of the truck locked and then pivoting his arm/boom from the center to the right. What is first a somewhat generalized projection of the brush truck's orientation is given further movement specificity as Antonio co-operatively elaborates on her gestures. Antonio directs the “locked it” motion to Roy as he gazes in his direction, seeking confirmation. Roy nods during Antonio's gesturing and confirms with “yeah” and a simplified, static locked jaw gesture. In doing so, Roy informs Krissie that “that's the easiest place to operate it,” further characterized by Antonio as the “safest (Lns. 9–10 and 12).”

As we will demonstrate throughout these transcribed interactions, marking is gesturing-for-dance. The notating of specific actions of the crane boom and jaw are given specificity and meaning in interaction, as Krissie observes how the arborists discuss the mechanics and movements. Through their talk and gestures, the arborists proffer their intuitive and kinesthetic knowledge (their professional vision as arborists to reference Goodwin, 1994) of how the crane operates, its optimal performance, and its mechanical limits. The co-operative semiosis that takes place here–the continuation and re-specificity of Krissie's original gestures as the crane–is insightful and necessary for her ability to transform their work into artistic ideas and is done so accumulatively. According to conventional crane operation, Krissie is taught–albeit on a micro-scale the arborists in this virtual space to “think” and “see” the work from their vantage point. With the establishment of this common understanding, Krissie can now integrate more artistic boundaries into the conventional boundaries (see Figure 4).

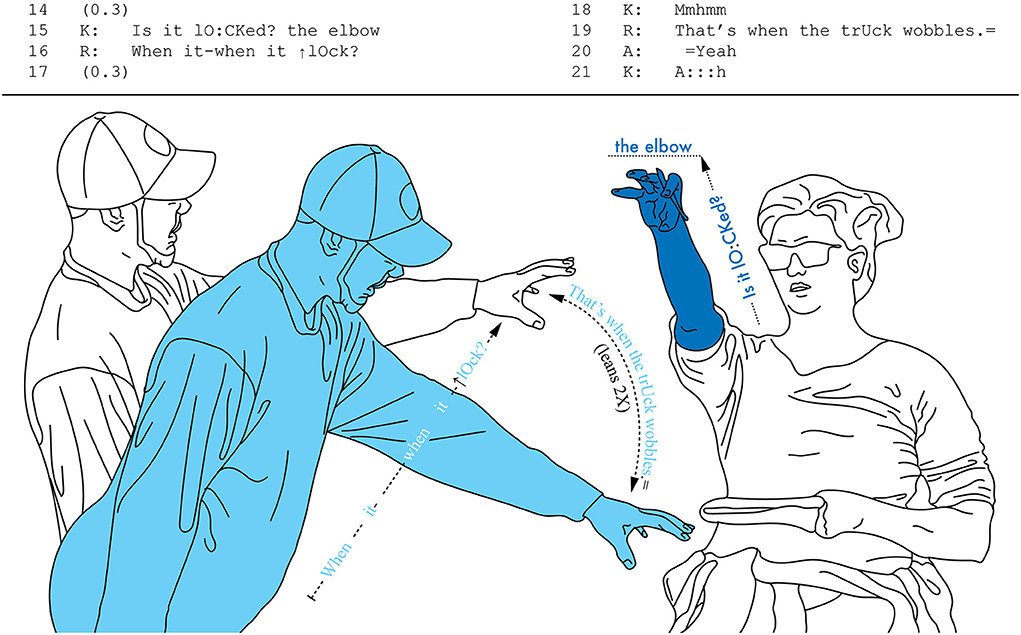

With Krissie's newly informed understanding of the dance routine and phrase(s) in mind, Antonio and Roy adapt the proposed vision of the brush truck routine in real-time. In Transcript 1.1, Antonio and Roy relay safety concerns and best practices when operating the brush truck crane in a locked position (referring to the knuckle of the crane bent) vs. having the crane fully-extended. With these concerns voiced, Krissie has to determine the implications of the truck's limitations on the artistic idea they've been crafting, asking, “Is it locked, the elbow?” (Ln. 15) as she completely extends her arm and forms a semi-opened claw hand shape. With Krissie's gesture, she takes the orginal meaning of "locked" that the arborists used to describe the knuckle of the crane's boom bent to now refer to the boom being fully-extented. She turns to Antonio when presenting the marking gesture, harkening back to his original “locked” term he attributed to her “weird elbow bent place.”

While the choreographers have an artistic vision of how to have the arborists act using their unique embodied movements, knowledge, and machinery, they have to do so by unpacking the arborists' intuition to bridge the expertise that is not shared between the two groups. This emergent vocabulary (mostly verbalized actions) speaks to the truck being talked about in uncertain terms because it was not designed for dance. Marking what the truck does requires a particular type of mimetic translation: the crane is couched in everyday language, and analogical links are made between the arm and elbow of the human body to the crane base, booms, and jaw. This is not all too surprising move since the boom on this knuckle boom truck is not entirely straight; it has a main and outer boom that enables it to bend, and many manuals on these trucks liken it to the human fingers' ability to bend at the knuckle. However, the ability to use hands as abstract analogical links (comparing the parts of the human arm and hands to the crane parts; Calbris, 1990, 2011) makes for smooth translations when the two groups converse and devise dance phrases.

Roy points out a safety concern regarding the brush truck that emerges when the crane boom is extended out fully: “that's when the truck wobbles” (Ln. 19). The utterance is multimodally packaged, a co-occurring ensemble of talk, bodily enactment, and the dance phrase being adjusted to conjure up a depictive scene. Roy, acting as the crane, extends his arm and tilts his body forward to illustrate the truck losing balance, and his intonation falls; therefore, mutually intertwined semiosis is achieved to demonstrate the feeling of falling or tilting downward and the undesirability of this outcome during the routine. The felt appearance of the body/truck tilting, coming off a stable axis, is made visible in the interaction. Krissie's marking gesture is elaborated upon; the crane booms and claw extended become problematized in the context of the added weight of the crane and base when Roy enacts beginning to “wobble” (Lns. 16 and 19). The marking together takes place in this context, not so much concerning marking for time, duration, intensity, or synchronization; they are marking out what potential pitfalls may occur, emulating the problem to guide Krissie to a more refined and functional alternative. Roy, in part, takes up the supervisory role while making a point for Krissie before proceeding to the next movement. He emphasizes the problem by repeating the wobbling motion twice and bobbing his head as the arm/crane “hits” its lowest point with a jerk. Krissie's understanding of the crane's limitations when locked is clarified, as evident by her “Ahhh” vocalization. To add to this understanding, Roy elaborates on the safety and feasibility of this maneuver (see Figure 5).

The “bent position” has implications for the synchronization and timing of the brush trucks, and Roy helps make this apparent, noting that “So when you gotta kinda bent, that's-that's when it smooth” (Lns. 22–23). There is overlap between the two, as Roy slightly marks the smooth movement quality of the crane in “bend position,” and Krissie overlaps with a partial repeat of his talk and gesture. The mutual elaboration of one another's gestures and talk illustrates that marking together depends upon co-operation and collaboration; they reconstitute each other's marked actions to transform them into new pathways for dance phrase creation and, in turn, establish a shared understanding. Learning from the arborists' expertise engender Krissie to revise the dance phrase in her notepad (Lns. 26–31), and this illustrates the transformative project at hand:

• The arborists' expertise informs and drives the dance creation process.

• The dance practitioners re-envision the practices and skills in an artistic light.

• The dialogue between the two ensures these artistic possibilities come to fruition by navigating the contingencies imposed on the process.

The artistic idea creation process and brainstorming described above are referenced in other studies of creative imagining. For instance, Murphy (2004, 2005) reminds us, in studies of architects brainstorming building plans, that the act of imagining, or at least one type of imagining made publicly visible, can be observed in social life via the talk, gestural actions, and ways people maneuver their material surrounds. Likewise, in Yasui (2013), studying students brainstorming a short film project, she observed how the repetition of gestures across different speakers and their respective turns-at-talk demonstrates how ideas (or particular aspects of them) can be accepted and rejected, modified, and even contested in interaction.

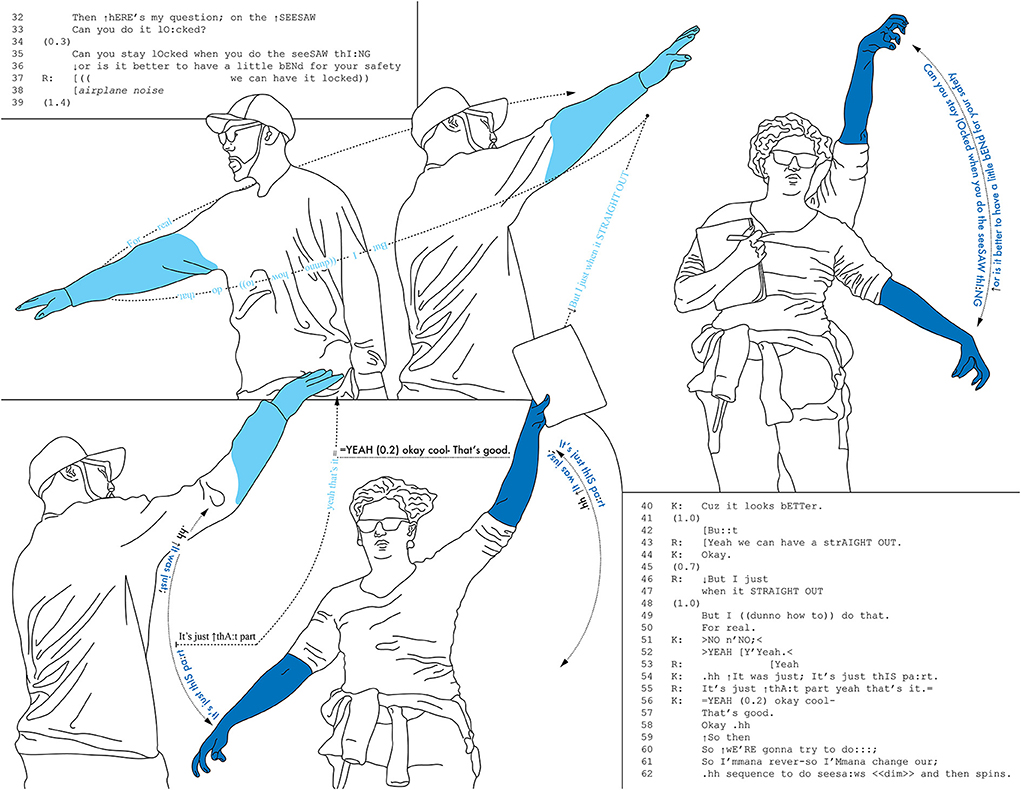

Marking together is a means of communicating depictively, enabling these two communities to build a shared vocabulary, imagery, and ways of making expertise publicly accessible. For Krissie, at least, from social interaction and ethnographic observations, the spirit of the dance company's work involves different levels of completion and interactivity. The dance practitioners must imagine cohesive dance phrases that are keenly aware of symbolic artistry. The interaction between artistic potential and logistical possibilities creates new forms of thinking about the dance phrases as they are under negotiation. In Transcript 1.3, the final transcript in this sub-section, Krissie explores the application of the “locked” position to another part of the dance phrase: the seesaw (see Figure 6).

The work of the brush truck is being reconceptualized from its day-to-day utilitarian use to fit more artistic endeavors. When Allison originally envisioned a dance for the brush trucks a few days earlier, the two trucks alternated, bringing the hydraulic arms to their highest peak with the jaw open. Synchronization emerges as a problem as the trucks move at varying speeds, depending on the machine's age and wear. With the newfound understanding of the implications of the crane boom being “locked,” Krissie must consider the safety concerns as the brush trucks up against artistic potentiality and aesthetics. “There's just one question. On the seesaws, can you do it locked?” Krissie asks in lines 32–33. Whereas locked in the previous excerpt refers to the crane jaw being positioned almost ninety degrees (the main boom extended with the outer boom bent) with a bend, Krissie uses “locked” again to refer to the crane arm (jaw included) fully-extended out (Ln. 15). She follows up with a reformulated question, “Can you stay locked when you do the seesaw thing or is it better to have a little bend for your safety?” (Lns. 35–36). In this second question reformulation, Krissie marks two potentials: a crane fully-extended (in a locked position) and a crane bent at the knuckle. Although a loud plane flies overhead, Krissie's confirmation-seeking activity is met with an affirmative nod from Antonio. Both then look to Roy, who assures Krissie they “can do it locked” (Ln. 37). Working between the demand of artistic thinking and practical logistics, Krissie provides the arborists with an account of why one of the two marked potentials is valued over the others: “Cuz it looks better” (Ln. 40) aesthetically to have the booms extended and alternating in tandem.

Krissie does not immediately secure uptake, though; when she turns to Antonio, he nods; she then looks to Roy, where he too nods, remarking, “Yeah, we can have it straight out” (Ln. 43). Also, Krissie begins to document the changes in her notepad. The surrounding noise (an airplane flying above) makes it challenging to discern what Roy says in line 49, though, it is clear that he projects a possible disagreement or anticipation of an issue when he utters, “But I.” In succession, the crane booms are straight out, and the arborists rotate the cranes diagonally full circle. Having the main and outer booms and the crane claw fully-extended while moving in a diagonal motion proves challenging, as it is an atypical maneuver. It is safer and easier to manage when the outer boom is bent at the “knuckle.” In lines 47–50, Roy motions with his hands, rotating his body around once in a circle stating, “But I just, when it's straight out, but I (dunno how to) do that” (Lns. 46–50). A discrepancy emerges between what is desirable for artistic production and what is logistically feasible or comfortably tenable for the truck operators. The imaginative work needed to envision and rework the routine is appreciated through gestures and talk. Krissie looks up from her notetaking as Roy marks out the next part of the phrase and immediately clarifies that she is not referring to the crane being fully-extended when they enact the circular motion; instead, she only would like to see the crane extended fully during the seesaw portion (Lns. 51–54).

What emerges is a prime example of what Goodwin (2017) discusses as the layering of co-operative action. Therefore, to clarify the moment she's thinking, she marks out the alternating movements of the two trucks in “seesaw” positions and looks at each of the arborists respectively with the gestures. Roy recycles parts of Krissie's talk and gesture, and the dialogic parallels and resonance (Du Bois, 2014) between their utterances and marking gestures convey subtle nuances in the now agreed-upon idea. When Roy marks out his version of extending and lowering the crane arm fully-extended, he only does so with one arm; he articulates his vantage point as a worker-actor, and his kinesthetic relationship as a skilled machine operator is fundamentally different from that of Krissie's. And vice versa, Krissie never presents herself as an operator, knowing more than what could be gleaned from the expertise of the arborists. Therefore, Roy repeating Krissie's marking gestures is not only a gestural repetition (Yasui, 2013) of the general trajectory and pacing of the crane; his actions and experience are layered onto her actions and understanding. To borrow Goodwin (2017) terms, the semiotic layering of these co-operatively assessed actions results in a shared agreement on how the dance phrase should progress. The collaboration between Krissie and Roy leads to a modification in the sequencing of the routine. In lines 58–62, she reverses the order of the “spins” with the “seesaws” to address the very problems Roy and Antonio propose from the logistical standpoint.

Marking together to communicate, as we've seen is a form of distributed physical thinking (Kirsh, 2011). We can add to this, noting that it is a method of gesturing-for-dance or dance notation of choreographed ideas (Warburton, 2014). Transcripts 1.1–1.3 illustrate how marking together with the hands can be as simple as an upward motion or as complex as taking on several features of an object or activity: the crane booms, the upper and lower jaw, and the truck base simultaneously. In due time, however, such semiotic complexity increases as dance phrases near completion, actors become accustomed to the rehearsal format, and the language of navigating these dance phrases and vocabulary becomes more accessible and integrated.

Dance phrases take on new meanings and change the co-constructed collaboration and co-operative transformation. This imaginative playground for the two groups helps them address expertise, logistics, and feasibility issues. Marking together is not a product of one person's innovative capacities; it is the depictive ensemble where the interactants involved re-create the appearances of dancerly actions. As fleeting as these appearances may seem in space to spectators, they are interactionally lasting and salient in the embodied conceptual remainders manifested in the subsequent actions and reactions to others' talk and gestures. Marking together creates a gestural flow of (virtual) actions of the brush trucks in which one person's bodily marking is contingent upon and only made possible by the immediately preceding gestures; they become part of the same flow for the more considerable dance creation activity. Repetition of gestural actions, albeit enacting the same dance moves, (re-)enacts an established movement within a marking practice (rehearsal) that enables the arborists to habituate the dance phrases with their own bodies, (re-)experience the phrases, and create space for nuanced revisions. There is, of course, a translation of sorts in this case since the arborists must then translate that to operating the brush truck controls after practicing it through their own bodies. With each repetition of a marked action, the repeated abstractive actions afforded by hands and arms (Streeck, 2009) open up new possibilities, stylizations, and alterations with new interpretability (Noland, 2009) and artistic rendering.

Marking together as idea scaffolding toward routine realization

In Transcripts 1.1–1.3, we illustrated how artistic ideas for the dance phrases are negotiated amongst the participants to bridge epistemic gaps and overcome potential disconnects between the artistic intent and logistical futility. In Transcripts 2.1–2.4–all part of the same videotaped moment and sequence–we break down the complex idea scaffolding as complex cognitive mappings occur and externalizations are pitched to different audiences. The transcript segments below appear after previously discussed to illustrate how marking together attends to various contingencies as the routine progresses. At this stage, the brush truck routine has advanced significantly and now involves a third operator and truck.

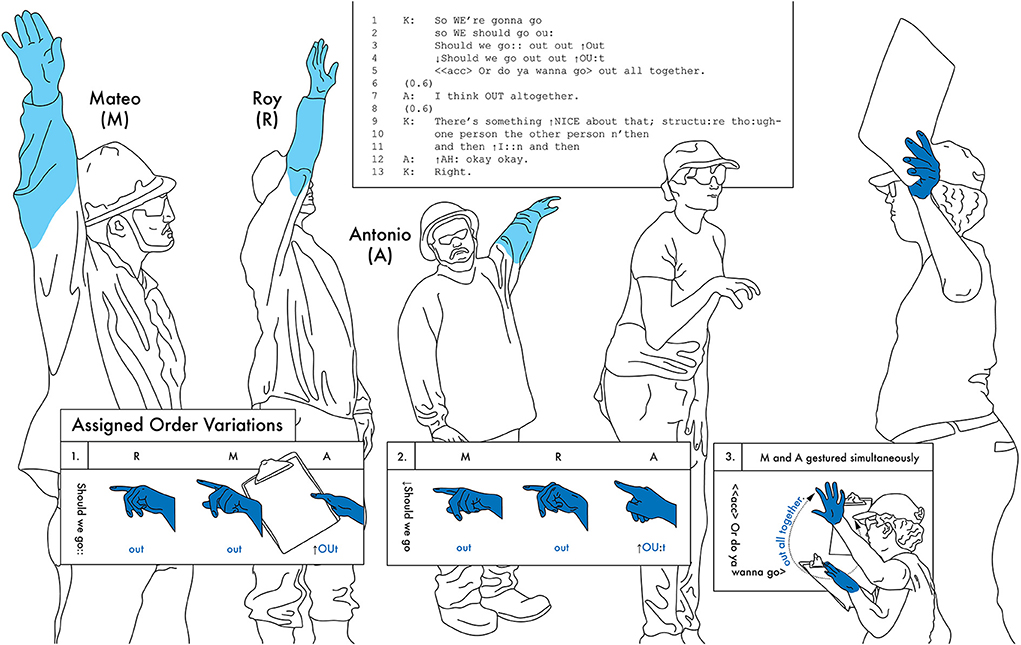

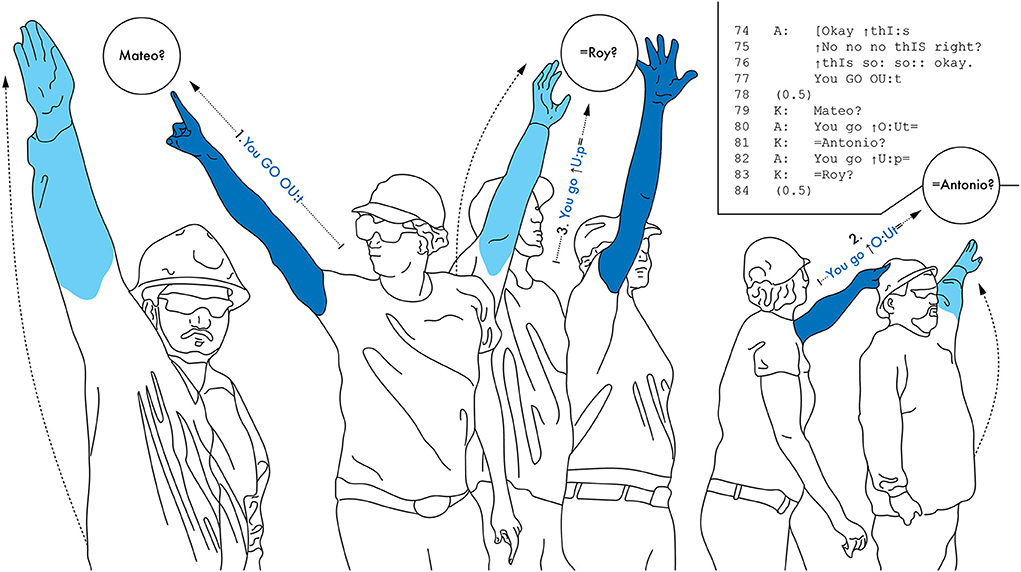

Transcript 2.1, which starts the series, involves a situation where the Artistic Director, Allison, and the Associate Artistic Director, Krissie, whom we discussed previously, walk through several dance phrases with the three brush truck operators: Antonio, Mateo, and Roy. As Allison runs through the brush truck routine with the arborists, Krissie checks and assesses the brush truck performance for accuracy and artistry. The back-and-forth, understanding checks, suggestions, and proposed revisions, become markedly visible. Allison can adjust and maneuver the arborists' positionality and ask them to enact parts of the dance phrase alongside her. This is possible because Allison, Krissie, Antonio, and Roy have previously taken part in the brush truck routine creation and rehearsal processes during an improvisational session. In contrast, Mateo is a relatively recent addition to this dance section. Also, in Transcript 1, a moment that took place days earlier, the routine only included two brush trucks; in this scene, they are preparing for a performance that entails three brush trucks and hence, three operators (see Figure 7).

With the addition of the third truck into the brush truck routine, Allison and Krissie face new choreographic tasks related to the sequencing and timing of the trucks. Transcripts 1.1–1.3 show that the dance phrase involves the brush truck cranes extending out in patterned sequences. Although the movements are established, there are variations upon the assigned order that can create different aesthetic effects. Rehearsal sessions, especially in the later development of a routine, involve careful mutual monitoring (Goodwin and Goodwin, 1980) of the movements (whether marked out or actually performed). The choreographers solicit advice from each other, and the arborists as needed. And in this interaction, they align themselves in rows: Krissie is in the front-facing, Allison, who is in the middle facing Krissie, and the arborists, in the furthest back row, face Allison and Krissie. As we will see, this formation becomes significant for the conceptual work accomplished in marking together.

As they've been incrementally working through the brush truck routine, Krissie foreshadows a marking out of the phrase concerning the extension of the crane arms. While, at first, in lines 1–2, Krissie projects a specific ordered sequence of the crane movements she has in mind; however, she quickly switches from a definitive statement to the modal, advice-giving should: “So we're gonna go, so we should go.” As she articulates the routine, Allison becomes a placeholder, assuming a general crane position by leaning her body forward with her right hand and articulating the knuckle bend crane with a claw hand shape. We can speculate several reasons for her assuming this position. For example, she may take on the general crane position predicting her participation will be requested. It is equally likely that Allison's crane position simply is a reminder of the blueprint and routine created thus far.

Krissie simulates three-movement possibilities the dance phrase can take, uttering “out, out, out.” Each “out” utterance is timed, emphasized, and aligned with a pointing vector (See Assigned Order Variations within Figure 7). For this reason, Krissie can use Allison's held crane position to accomplish some conceptual work.

1. Krissie points with her left hand to Roy and Antonio and then her right hand with the clipboard to Mateo (Ln. 3).

2. Krissie points with her left hand to Mateo, Roy, and Antonio (Ln. 4).

3. Krissie emulates all three trucks, stating, “Or do ya wanna go out altogether,” as she puts her arms upward fully on both sides of her body (Ln. 5).

The semiotic landscape in the here-and-now discourse is transformed. Through pointing, Krissie externalizes a complex set of timed sequences and movement patterns that will require precise coordination in the performance's full realization. When Krissie proposes the last combination of all the trucks moving synchronously (referred to as “out altogether” in Ln. 5), her speaking rate increases gradually. As she points “out” the options, she is, as Kirsh (2011) distinguishes, mentally simulating via imagining the movement order of the routine. However, we take imagination in our context to not refer to localized or simply individualized internalized imagery; in fact, aspects of imagining can be laid bare in interaction through collaborative imagining (Murphy, 2004, 2005) or collaborative idea construction (Yasui, 2013). The arborists act as the trucks and therefore are conceptual surrogates (Liddell, 2000), this is useful for Krissie who can simply point to the arborists to conjure up or simulate a movement order. Only in the last part of the enactment, when she acts as all three trucks, does she truly mark the actions.

We encounter, here, “perceiving in the hypothetical mode” (cf. Murphy, 2004, pp. 269–270): the negotiation sets out a course of imagined possibilities as they see the marked phrases imagined as-if they were the actual trucks moving, thus, seeing what potential the routine could take. The goal is for Krissie to secure quick confirmation from Allison on which of the interpretations would be most aesthetically appropriate. The back-and-forth is a means of identifying what needs improvement and the best way to carry out the routine with the most straightforward and concise artistic message. In the end, Krissie marks the sequence only in the final iteration, when she needs to conjure up the image of all three trucks moving in arrangement, which does not lend itself to the embodied resource of pointing, since she'd have to not only index all three trucks but also, move them up at the same time.

Allison, in line 7, proposes they stick to “out altogether.” However, Allison's suggestion is not quite the preferred option for Krissie, who responds after a pause: “there's something nice about that structure, though” (Ln 9–11). To aid Allison in seeing the aesthetic import of the structure, Krissie marks out the staggered, alternating crane extensions of the trucks. As she utters, “one person, then the other person, n' then” (Ln. 10), Krissie extends her right arm and then her left arm. As she finishes that utterance, Roy contributes to her marking, lifting his right hand as a stand-in for the third truck Krissie cannot illustrate due to the gestural affordances of her two arms/hands. Krissie and Roy's actions, taken together, form the three-truck-formation marked together. Allison, at this moment, though facing Krissie, pivots to see Roy, positioned slightly to her right. Although Krissie is marking for Allison, she is also enacting it with her own body. It is possible that marking, at this moment, is done for mutual assuredness (marking-for-self and marking-for-others, a distinction Kirsh, 2010a, 2011 makes): Krissie can appreciate the alternating, rhythmic patterning within her own body while illustrating it for Allison.

The three iterations are enacted in quick succession, enabling all parties to compare and contrast the dance phrase possibilities, the final of the three being marked by Krissie with Roy's accompaniment. The focus of this activity concerns not feasibility but artistic potential; therefore, the pointed variation and marked movements are directed from Krissie to Allison regarding the arborists behind them. Although the arborists in this segment do not contribute verbally, they play a significant role in meaning-making. Mateo, Roy, and Antonio are aligned in their assigned positions as the brush truck operators in the furthest back row. Allison, meanwhile, is holding a brush truck crane pose. The contextual configuration (Goodwin, 2017) encourages certain types of communicative potential: Krissie can map Allison's brush truck pose onto the arborists behind her who serve as stand-ins for the trucks, as they are the machine operators. These conceptual layers involve deictic points, talk, and marking to envision what could hold more aesthetic potential in quick succession. Although communication from the arborists is welcomed at this stage, it is unnecessary unless it will affect how the choreographers realize the dance phrases in the performance. Marking is only resorted to at the end of this sequence to show Allison why she prefers to have the brush trucks moving in a staggered manner vs. one joint action synchronously: “There's something nice about that structure though” (Ln. 9). Nearing the end of Transcript 2.1, Krissie marks out the “preferred” structure so Allison can evaluate the artistic form. In line 12, Allison confirms her appreciation of the preferred format of the phrase: “Ah, okay, okay” and, in a continuation of the segment in Transcription 2.2, marks out the phrase for Krissie. The conceptual groundwork established between the two choreographers will now be implemented. Krissie marked out the actions so Allison could experience the artistic value of the cranes extending one by one; now, Allison turns to the arborists to mark together the sequence more elaborately (see Figure 8).

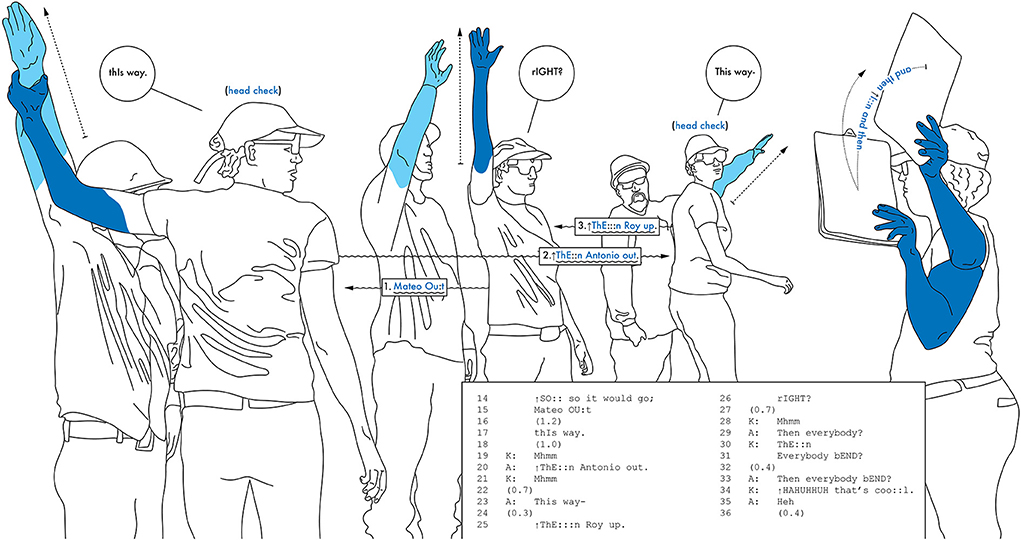

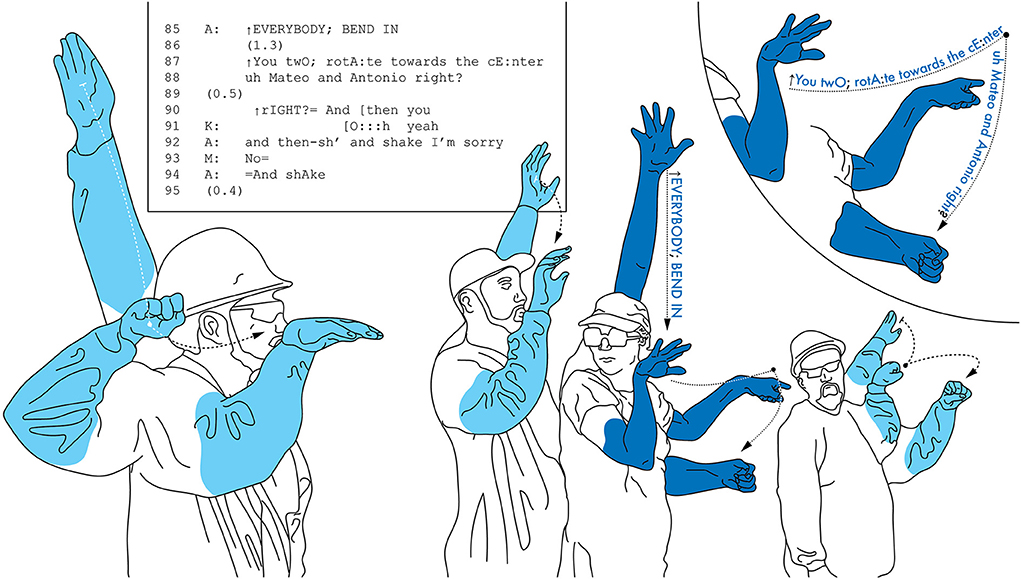

At the start of Transcript 2.2, Allison models Krissie's proposal we analyzed in Transcript 2.1: having the brush truck cranes move in an alternating sequential order as they raise up. Using the quotative “go,” she utters, “So, so it would go” (Ln. 14) and projects a forthcoming demonstration (cf. Clark, 1996, 2016, 2019) of how the cranes proceed:

1. First, Allison walks toward Mateo and utters, “Mateo out (1.2) this way,” and he extends his arm slightly toward the center of his body (Lns. 15–17). Allison grasps Mateo's wrist and curves it to his right side. Krissie confirms that adjustment with “Mhmm” (Ln. 19).

2. Second, Allison walks past Roy in the middle (he accidentally raises his arm) and utters, “Then Antonio out (1.2),” taps Antonio's arm, and extends it out (Ln. 20); Krissie again confirms the phrase with “Mhmm” (Ln. 21). And Allison taps his arm.

3. Third, Allison, moving to the middle in front of Roy, utters, “Then Roy up, right?” (Ln. 25) as she extends her right arm. Roy, shortly afterward, follows suit, raising his right arm as well. Krissie, once again, confirms the ordering and the marked version with an “Mmhm” token (Ln. 28).

4. Finally, as Krissie vocalizes her appreciation with consecutive “mhmm's, “Allison tries to remember the next part, “Then everybody?” (Ln. 29). Krissie, consulting her notes, steps in and provides the next movement. As she does so, she co-opts Allison's language, stating, “Then everybody bend” (Ln. 31). Allison repeats Krissie's words, “Then everybody bend,” (Ln. 33) and, as she does this, bends her elbow and the arm back (the crane knuckle between the booms and the jaw/claw joint). All three arborists do the same movements in tandem.

Much like the previous examples, this moment starts with one person confirming the choreographic idea pitched briefly before and guides that idea step-by-step as it progresses through cumulative stages. Allison marks so Krissie perceives the idea she proposed in visuo-kinesthetic form; she does this by marking out the movements with her own hands while enabling Krissie to see a larger-scale version via the arborists who simultaneously enact the brush truck movements behind them. The elaborate marking together is done with both talk and gesture complimenting each other at each stage. As she states the verbal actions aloud, she also starts each utterance (an act for each truck to accomplish) by raising intonation, and she extends her arms and the arborists.' The semiotic layering of hand gestures, talk, intonation, and movement (Mendoza-Denton and Jannedy, 2011) conjures a vivid model of the dance phrase that Krissie can examine as a spectator/reviewer. After Allison and the arborists model the dance phrase, it results in an “aha moment.” Krissie says, “HAHUHHUH, that's cool” (Ln. 34), with a noticeable pitch step-up and roaring laughter, and Allison also laughs (Ln. 35).

Transcript 2.1 begins with Krissie (mentally) simulating with pointing gestures and then partially marking the brush truck crane formation. Allison maneuvers her body to each of the arborists in the order in which the crane arms should extend and co-augments them to mark and maintain the alternating extensions. She guides the arborists through grasps, touch, and instructions, all of which work together to produce a marked ensemble that is now made perceivable to Krissie.

Marking together takes on a new set of relational dimensions, whereby multiple actors jointly mark in real-time for Krissie to see the phrase played out. Allison serves as an orchestrator, cueing the arborists when to mark by following or anticipating her example. A rhythm is established with each marked action, as the cranes all extend in relative time and meet their spatial designations, reaching the phrase's end and symbolic potential at the height of its artistic symbolization (Langer, 1953): the choreographers see the coordination play out, with actions presented and what they will accomplish when the arborists make the trucks dance for an audience.

Now that the brush trucks have undergone several iterations, the choreographers can clarify the dance phrases and corresponding culmination of movements, leading to a remembering session. In Transcript 2.3, each person who has been present in the different iterations of the routine can contribute to completing and refining the vision. Each participant, having differing epistemic access and embodied relations to the performance (because of their availability and addition to the dance routine), contributes to the small-scale, scaffolded modeling of the phrase (see Figure 9).

Although Krissie and Allison agree with the phrase they just mapped out, they forgot about the “shaking” and “pivoting” of the crane jaw; hence, they jointly remember the phrase sequencing. Allison looks to Roy to confirm if her memory is correct because he had been present at all the rehearsals: “But, but what it was Krissie, it was bend and it-it was pivot, right?” (Lns. 37–40). Roy promptly, as directed, corrects the proposal, noting that the sequence was that they bent the crane arms and then shook them (Lns. 41–44). Even this correction is very much a marking together activity. Roy emulates jaw shaking while pivoting the crane (Ln. 41–43). Since part of Roy's utterance “It was bend, and then we shook” (Ln. 41–42) is met with a pause, a possible point to transition between speakers, and Allison, thus, overlaps with Roy. She repeats Roy's action verbs “bend and shook” while reusing his marking of the shaking jaw and rotating crane (Ln. 45). Her repetition of Roy's hand marking amplifies his production, and she proffers it to Krissie. Krissie overlaps with Allison, making slight movements with her hands and showing certain actions of the crane (Ln. 46). The audio overlap makes it impossible to discern what she says accurately.

Roy points out a problem with the previous rendition: it involves one fewer truck than required (Ln. 47). After a slight pause, Allison recognizes Roy's concern (Lns. 49–50); the additional truck adds a layer of complexity. Eventually, Roy proposes a solution to retain an aesthetic consistency of appeal, synchronization, and balance. Before that impetus, his proposition is initiated by Antonio breaking the silence, “I think that we should meet everybody like” (Ln. 50). As he says this, Antonio laughs and marks the truck moving to the center (not illustrated in the transcript), his arm/the crane. The arborists still maintain their respective positions as worker-actors/operators. His short injection ends with a fist-bump gesture into Roy's shoulder (Lns. 50–54). Allison engages with a sweeping proposal because it articulates something they are trying to work toward: all the brush trucks (fully-extended) bringing their jaws together. Right after Antonio taps Roy on the shoulder, Allison and Roy raise their arms, marking out (if we consider Antonio's arm) the three cranes acting in unison and coming together with the jaws touching at the peak (Ln. 52–53). There is a continuity of the dance phrase idea, as each arborist holds their hands/the crane extended, enabling Allison and Roy to try and revise the phrase in real-time. They've arrived at a shared point where revisions are necessary, and ideas are encouraged. Marking together, in the way it is enacted here, involves a scaffolding of complex movement ideas as they are fitted to emerging contingencies.

The addition of the third truck raises several questions: What direction does each crane face? When do the cranes shake or bend? How does the movement pattern integrate with a third truck? Allison attempts to articulate one of those possibilities as she's thinking it through, though she struggles to do so, uttering “What if it-it's, what if it's” it's (Ln. 55–56) and motions to her right with the raised arm. Roy co-operatively builds on and finishes what Allison starts by stepping in where she leaves off, “What if they still do that and I just stand here and just shake” (Lns. 57–59). As he utters this, his two hands mark (the left crane and the right crane jaws, respectively) shaking, and then he drops his left hand to centralize his right hand, illustrating the third/middle truck, “And I just stand here and just shake.” Allison shows enthusiasm for Roy's modification, uttering, “yeah,” as she torques her body, offering a momentary involvement (Schegloff, 1998) with Krissie to seek her confirmation (Ln. 60).

A complication arises in whether the cranes are to meet or touch, when they are extended and what the middle truck (Roy in this case) should do before the trucks on the side turn to the middle. Krissie proposes a slight alteration to when Roy/the truck shakes, which occurs only after extending, instead of him staying fixed in one position: “Or you can just bend, and you could then go back and shake” (Lns. 62–63). This leads to a back-and-forth negotiation of the phrase (see Figure 10).

Krissie attempts to secure confirmation of whether her alteration changes the ideas Roy proposes or simply modifies it: “Yeah? That's-is that the same thing?” (Ln. 64). As Krissie is asking Roy this question, Allison points to Roy and her point transitions to a marked-out proposal (see Figure 10). Roy indicates that the two ideas differ, and to help Krissie comprehend the implications of these two variations: he re-marks the movement sequence. In the first iteration, Roy is presented as marking for time, shaking in the center. In the second iteration, his readiness transitions into the next part of the dance phrase as all trucks converge while shaking (Ln. 65).

Roy completes his multimodal action with a gesture, in what linguists Hsu et al. (2021) refer to as a moment where the gesture “takes over.” Roy marks (and thus depicts) the action of the two cranes rotating and facing each other instead of verbalizing this part of the dance phrase. Roy is marking out the movements of the left and right brush trucks, while Allison has her right hand extended fully, held in position, and shaking, marking the time of the third, middle truck.

The marked actions–the ideas being verbalized and depicted focus on different selective aspects of the cranes (timing, position, and movement)–integrate conceptually into one clear image. Allison tries to unify all of these ideas to feature the most productive potential for the dance phrase. “And then you both, you kinda all three go like that together,” she utters, extending her arm slowly, clapping, and then pointing to Roy with an emphatic “Yeah” (Lns. 69–71). It remains clear that all of these ideas marked out need to be playout out in full, as Roy expresses that there are still potential issues with their modeled phrase: “But they gon' be already be extended like that” (Ln. 73).

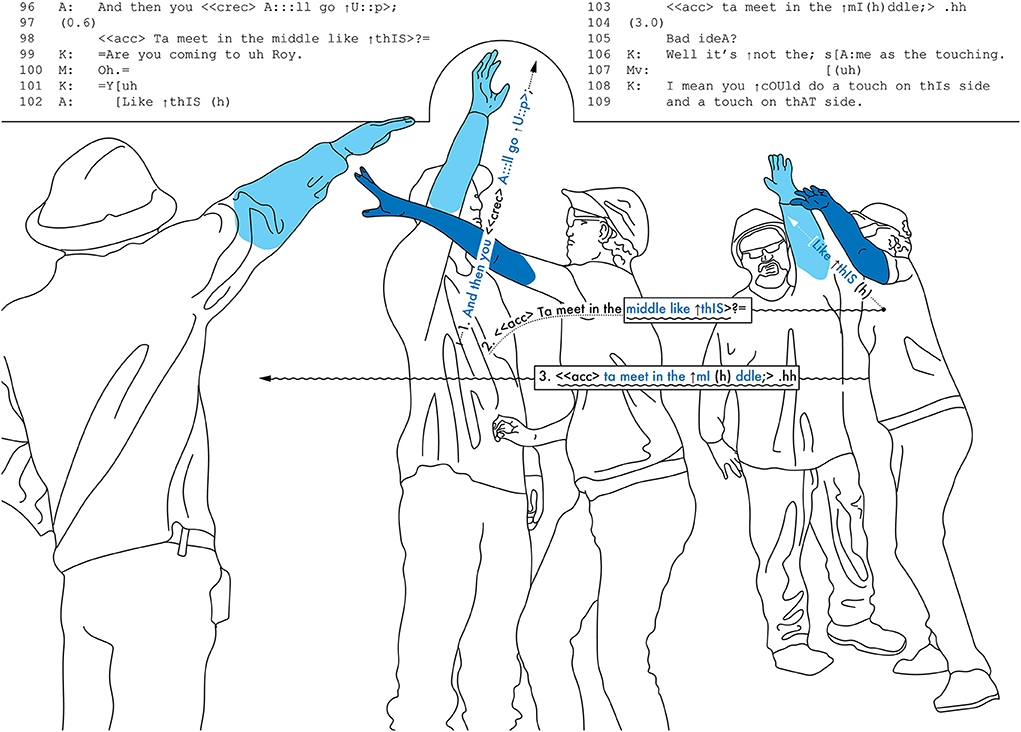

As we will see in our last segment, hypothetical imagining of a routine involving the third truck leads to various considerations when the arborists try to think practically and logistically. Allison is now prepared to present a summary of these ideas. As small-scale, layered marking actions are laminated onto one another, the dance phrase, and the interactant's abilities to keep these temporary products in mind, become increasingly challenging. To find out the point of disagreement and clarify what the choreographers have in mind regarding Roy's suggestion and understanding, Allison resorts to a more elaborate form of marking together that we observed earlier where she serves, functioning as the artistic director and orchestrator, augments the bodies of the arborists standing in for the trucks. Ultimately, one iteration must be taken up and enacted.

Gearing up for practice, she prepares all parties: “Okay this. No, no, no this right? This, so, so, okay” (Lns. 74–76). There is intertextuality between Krissie's original simulation of three movement possibilities in Transcript 2.1, which uses points and verbalizes “out[s]” to map a conceptual framework, and Allison's three-part re-iteration (see Figures 11–13):

Transcript 2.4a

1. In lines 77–79, Allison utters, “You go out,” demonstrating while pointing with her right arm for Mateo to extend his arm (the crane). Krissie then notes Mateo's name.

2. In lines 80–81, Allison utters, “You go out,” a second time, demonstrating while pointing with her left arm. Krissie then notes Antonio's name.

3. In lines 82–84, Allison utters, “You go up,” in the last iteration of the three-part series, demonstrating while pointing and looking over her shoulder at Roy. Roy extends his right arm up in front of his torso; it parallels Allison's arm. Krissie, once again, notes Roy's name.

Transcript 2.4b

4. In lines 85–86, Allison utters: “Everybody bend in.” Everyone follows Allison in bending their respective arms.

5. In lines 87–91, Allison looks to Antonio and then to Mateo for their attention, then makes a curved pointing gesture with her left hand at Antonio to illustrate the rotation. The pointing, eye contact, and naming mutually reinforce one another. Allison maintains her position as the third and middle crane, holding her left hand extended while her point indexes the need for the cranes to rotate; her head movements and visual command to each respective part guide the directionality of action as both Antonio and Roy need to turn toward the center: “You two rotate toward the center, eh Mateo and Antonio, right? Right, and then you.” Krissie confirms the movement sequence up to that point at the rotations: “Oh yeah,” (Lns. 87–91).

6. In lines 92–95, Allison has slight difficulty recalling the next part of the dance phrase, “And then sh-shake, I am sorry.” For instance, in line 93, Mateo looks at Allison, has his right arm/crane extended forward, resets his crane/arm, and then rotates from his right to the center. At this moment, the arborists adjust accordingly, attempting to watch Allison and maintain their positions.

Transcript 2.4c

7. In lines 96–98, Allison directs: “And then you all go up to meet in the middle like this,” marking out the synchronization and coordination of the trucks; her voice crescendos to emphasize the up descriptor and gestures, mutually reinforcing the multimodal image. In one motion, Krissie reminds the group that Antonio and Mateo will rotate toward Roy: “Are you coming toward Roy.” She then points and instructs Mateo. Based upon the accelerated reaction by Allison to correct first Antonio, then Mateo, to turn toward the center, two interpretations come to mind: Allison, when she directed the arborists, was expecting them to do what Krissie noted by rotating toward the center truck. Or, Allison was staggering these movement phrases and waiting until everyone was at the same understanding and coordination. Either way, Allison instructs all parties in a multisensory way: she positions Antonio to the center, verbalizing the instructions and touching and rotating his extended arm “to meet in the middle” (Lns. 100–104).

As we've argued, the conceptual work illustrated in Transcript 2.1–2.4 takes shape in a complex series of stages continuously refined in scope. As the segment begins, the choreographers, working amongst themselves, attempt to lay bare a brief schematic of the dance routine to the present moment. This starts with Krissie, simulating the sequential order of the brush truck crane extensions (pointing to arborists who are aligned and serving as placeholders for the trucks). As they develop the routine, a much more refined physical form of thinking and visualizing is needed. Marking together becomes a moment-to-moment negotiation in an imagined space (Murphy, 2004, 2005); they move from larger-scale marking moments that include the choreographers guiding the bodies of the arborists to a highly fine-grained analysis of how one movement of the crane is to be performed and its artistic accomplishment(s) valued within the sequence's broader context.

As with the goal of community-based artmaking, marking is a gesturing-for-dance crafted from insight gleaned from both parties' knowledge contributions and negotiations. The layering of marked action through these diverse embodied enactments contributes to an accumulated understanding of the potentialities. To work through contingencies, such as how to involve a third truck or whether a crane should bend and shake, is so much easier in the virtual space where modification is efficient when tied to the body and not the truck it represents. When they arrive at the conclusion of the sequence, it is mainly made salient that although many parties were involved, it is challenging to attribute ownership to any part of the resulting dance phrase. Marking together is just that, a production in which the contributions of all parties, in the form of layered, incremental actions, test those potentialities and arrive at the most artistically, prudent, and feasible idea.

Discussion

In this article, we laid out an interactional approach to the empirical study of marking practices as they unfolded in rehearsal interaction between community-based dance practitioners and city arborists. When the dancerly materials for artmaking are derived from the stories, techniques, pieces of knowledge, and lived experiences of a local community as forged through the interaction between two disparate communities (trained dancers and performers who do not identify as dancers), a mode of communication must be constructed to bridge gaps in knowledge, as the dancers learn to think like arborists and the arborists learn to think like a dancer. The choreographers needed to observe and, to a point, participate in the arborists' day-to-day work. The arborists must participate and become receptive to the dancemaking process, which entails thinking about their professionalized skills and tools in new ways. The choreographic process can become challenging, for instance, when actual chainsaws, brush trucks, and pole saws are being operated in the performance. As we've shown, marking is critical for establishing mutually intelligible and relatively consistent communication between these two groups.

Most cognitive ethnography or psychology of dance scholarship on marking devices (Kirsh, 2010a,b, 2011, 2012; Muntanyola-Saura and Kirsh, 2010; Warburton, 2011, 2014, 2017; Kirsh et al., 2012; Warburton et al., 2013), turn their readers' attention to the visuo-kinesthetic forms of (distributed) cognition. A micro-interactional approach to studying marking practices reinforces these ideas; however, it, in addition, sheds more light on how mark-making is used to communicate through contingencies, lead to complex semiotic transformations, and perhaps, most importantly, when something is marked-for-dance in these community-based artmaking contexts, at least, it is hardly ever the product of one individual. Hence, we put forth the notion of marking together, or perhaps more aptly put together-marking, because the togetherness captures the interactional reality that takes shape in its multiplicity of meanings.