- Pragmatics Department, Leibniz-Institute for the German Language, Mannheim, Germany

In theater as a bodily-spatial art form, much emphasis is placed on the way actors perform movements in space as an important multimodal resource for creating meaning. In theater rehearsals, movements are created in series of directors' instructions and actors' implementations. Directors' instructions on how to conduct a movement often draw on embodied demonstrations in contrast to verbal descriptions. For instance, to instruct an actress to act like a school girl a director can use depictive (he demonstrates the expected behavior) instead of descriptive (“can you act like a school girl”) means. Drawing on a corpus of 400 h video recordings of rehearsal interactions in three German professional theater productions, from which we selected 265 cases, we examine ways to instruct movement-based actions in theater rehearsals. Using a multimodally extended ethnomethodological-conversation analytical approach, we focus on the multimodal details that constitute demonstrations as complex action types. For the present article, we have chosen nine instances, through which we aim to illuminate (1) The difference in using embodied demonstrations versus verbal descriptions to instruct; (2) typical ways directors combine verbal descriptions with embodied demonstrations in their instructions. First, we ask what constitutes a demonstration and what it achieves in comparison to verbal descriptions. Using a typical case, we illustrate four characteristics of demonstrations that all of the cases we studied share. Demonstrations (1) are embedded in instructional activities; (2) show and do not tell; (3) are responded to by emulating what was shown; (4) are rhetorically shaped to convey the instruction's focus. However, none of the 265 demonstrations we investigated were produced without verbal descriptions. In a second step we therefore ask in which typical ways verbal descriptions accompany embodied demonstrations when directors instruct actors how to play a scene. We distinguish four basic types. Verbal descriptions can be used (1) to build the demonstration itself; (2) to delineate a demonstration verbally within an instruction; (3) to indicate positive (what should be done) and negative (what should be avoided) versions of demonstrations; (4) as an independent means to describe the instruction's focus in addition to the demonstration. Our study contributes to research on how embodied resources are used to create meaning and how they combine with and depend on verbal resources.

1. Introduction

Movements in theater plays are rehearsed compositions, emerging over a course of rehearsals that last for several weeks or months. Depending on the form of theater, they are constrained by a script and/or the director's aesthetic concept,1 which are to be embodied in the actors' play. Movements are the results of agreements of a temporary community of practice (the ensemble) concerning how to perform play actions on stage for an audience. Being workplace interactions, theater rehearsals follow an institutional routine. In the three productions we studied, scenes are developed by directors giving actors open instructions on how to play (aspects of) a scene. The director in turn builds on the actors' performances to give more refined and concrete instructions. Unlike movements in everyday life, which are usually unscripted and uninstructed, many movements in theater rehearsals are instructed, evaluated, and corrected (by reference to prior instructions), and possibly further negotiated. In this way, scenes adopt their shape over series of sequences of directors' (mainly) verbal instructions and actors' embodied implementations.

In this paper, we analyze directors' use of demonstrations in instructions in terms of how they are constructed, what actions they perform, and how they relate to verbal instructions.2 Our study does not have longitudinal claims, which would require a different collection design (Wagner et al., 2018) and present a different kind of research question, namely how ideas are collectively developed over time (for this, see Murphy, 2005; Yasui, 2013; Hsu et al., 2021a; Norrthon and Schmidt, in press; Schmidt and Deppermann, in press). When directors instruct a certain idea, e.g., “acting like a school girl,” they can use verbal descriptions of various levels of detail (e.g., “act like a school girl” or “speak in soft sweet voice” etc.), or they can show what they expect an actor to do by demonstrating the behavior in question. In this sense, directors' instructions always have a conceptual (“school girl”) and a procedural (“how to act as a school girl”) aspect (s. Szczepek Reed, 2021).

Our study will address the following research questions:

• How are demonstrations designed and what are their main features?

• What do demonstrations achieve in comparison to verbal descriptions?

• Which role do linguistic resources typically play in instructions including demonstrations?

• How are demonstrations combined with verbal descriptions to convey directors' ideas in their instructions?

In what follows, we first distinguish between descriptions and depictions as two fundamentally different modes of meaning making (2.1) and discuss their differences in the context of instructional activities (2.2). In this context, depictions can be realized by illustrations (e.g., moving up the hands to illustrate a higher voice) or demonstrations (e.g., enacting a higher voice). While the former are not meant to be imitated, the latter are.

After an introduction to our data and approach (3), we show on a typical case how demonstrations that are to be imitated are constructed (4). In a second analytical part, we focus on how language figures in instructions using demonstrations (5). Language can be part of the demonstration itself, as when lines from the script text are quoted (5.1); it can delineate, introduce and embed demonstrations within the instruction (5.2); it can clarify the status of demonstrations as a quote of previous mistakes or as a model of desired behavior (5.4); or, most frequently, it can describe an idea verbally (5.4).

2. State of the art

We first address studies on descriptions and depictions as two different methods of meaning making in general (2.1), and then turn to instructional contexts in particular (2.2).

2.1. Descriptions versus depictions

The difference between depicting or showing, and describing or telling as basic modes of communication can be traced back to ancient Greek philosophy. Plato distinguished between mimesis and diegesis as two fundamentally different methods of representation in art and literature (Klauk and Köppe, 2014, p. 3; see also Halliwell, 2013). Mimesis, typically realized in fine arts, imitates the world, while diegesis, typically accomplished in literature, describes the world.

“In the showing mode, the narrative evokes in readers the impression that they are shown the events of the story or that they somehow witness them, while in the telling mode, the narrative evokes in readers the impression that they are told about the events” (ibid.: 1).

Clark and Gerrig (1990), Wade and Clark (1993), and Clark (1996, 2016, 2019), following Peirce (1994, 1931–1958), distinguish three basic modes of communication, which use different principles: Indexing (such as pointing), resting on physical connectedness, refers to events by locating them; describing refers to events with signs based on conventions (typically language); depicting shows events and rests on resemblance. Depictions “are physical scenes that people stage for others to use in imagining the scenes they depict” (Clark, 2016, p. 325). In this way, depictions create “physical analogs” (ibid.: 327) which do not rest on concepts (as e.g., words do) but on percepts. Not all aspects of instances of depictions serve a depictive function. Clark and Gerrig (1990) distinguish between (1) depictive aspects (serve to depict), (2) annotative aspects (comment on the depiction), (3) supportive aspects (makes the depiction possible), and (4) incidental aspects (no specific function). In order to identify what is being depicted (the “demonstration proper,” Clark and Gerrig, 1990, p. 769), recipients must recognize which aspects are meant to be depictive and which are not.

Clark and Gerrig (1990) understand demonstrations in a similar way to quotations, since demonstrations, as quotations, cite one's own or others' behavior, e.g., demonstrating how a friend eats spaghetti means quoting his behavior. In later publications, Clark (2016, 2019) uses “depiction” as an umbrella term, covering all means of meaning-making that use iconic methods and rest on principles of perceptual resemblance (s. Clark, 2019, p. 236). His focus is on “performed depictions” (Clark, 2016, p. 324) as opposed to “exhibited depictions” (ibid.) (e.g., a painting). In contrast to the latter, performed depictions “are created and displayed by a single person, (…), at a single place and time in a single set of actions with a single set of goals. It is performed depictions that are integral to language use” (s. Clark, 2019, p. 236).

Clark (2016, p. 326 et seq.) differentiates five forms of depicting studied in different traditions: In addition to illustrative/iconic gestures (cf. e.g., McNeill, 1992; Kendon, 2004, p. 84–107), facial gestures (cf. e.g., Ekman and Friesen, 1969), spoken quotations (cf. e.g., Wade and Clark, 1993; Günthner, 1999), and make-believe play (cf. e.g., Goffman, 1974; Sawyer, 1993), he lists “full-scale-demonstrations” (ibid.: 327; e.g., showing how to play a piece on the piano) as a subcategory of depictions. Clark (2016, p. 325 et seq.) distinguishes “adjunct,” “indexed,” “embedded,” and “independent” depictions; the former is “concurrent” (Clark and Gerrig, 1990, p. 766), the three latter are “component” (ibid.) parts of surrounding discourse (see Hsu et al., 2021a for a critique). Depiction as iconic gestures usually accompany talk, adding meaning to simultaneously produced parts of talk (“lexical affiliates,” Schegloff, 1984, p. 276; Kendon, 2004, p. 127–157; Streeck, 2009, ch. 6). As components parts, depictions can be indexed by talk (e.g., by demonstratives such as “like this,” Streeck, 2002; Stukenbrock, 2014) or embedded in talk (replacing linguistic projected units such as NPs or adjectives) building “syntactic-bodily gestalts” (Keevallik, 2010, p. 309). Finally, depictions can be independent parts of the discourse serving as actions or turns in their own right. Demonstrations are often indexed by, embedded in, or independent of verbal descriptions, while illustrative/iconic gestures are often concurrent parts of composite utterances (Enfield, 2009), depicting what is talked about.

Demonstrations use specific methods to represent what they depict. Kendon (2004, p. 160) distinguishes three representational methods (common to what he takes as iconic gestures) which are (a) modeling (using body parts to stand in for an object), (b) enactment (similar to pantomime), and (c) depiction (similar to tracing/painting an object in the air). Streeck elaborates depiction methods further, distinguishing “mimetic gesturing” (Streeck, 2009, p. 144) and “depicting action” (ibid.). Streeck (2009, p. 146) explicitly stresses the latter's proximity to theater: “ordinary conversational re-enactments bear the seed of performance art, of stagecraft,” which can “also be elaborated into pantomime and caricature” (ibid.). In this paper we use Clark's (2016, 2019) notion of “depiction” as an umbrella term for iconic modes of meaning making. The demonstrations we are studying (see below) are “enactments,” as “body parts engage in a pattern of action that has features in common with some actual pattern of action that is being referred to” (Kendon, 2004, p. 160), mimicking them for instructional or “modeling” (Szczepek Reed, 2021, p. 3) purposes. They do not quote or “replay” (Goffman, 1974, p. 506) past behavior (except for showing actors' previous mistakes), but “pre-play” (Stukenbrock, 2017, p. 238) future behavior as a candidate solution for actors' performance.

Depictions are multimodally laminated phenomena (Cantarutti, 2020, ch. 2.3; Löfgren and Hofstetter, 2021, p. 7–10). In theater, they include a great variety of resources, e.g., gesture, verbal quotes from the script and choreographic elements, props, music, costumes, a certain use of space, and inventing “subtext” (s. ex. 5, 6, and 7 below). When directors instruct by demonstrating, all resources are organized in ways that help actors to understand the instructions and, most importantly, to identify which parts should be imitated and which should not (s. Section 4 for a step-by-step analysis of the construction of instructive demonstrations).

Demonstrations are not carried out for their own sake but for other purposes, e.g., demonstrating how a friend eats spaghetti to make fun of him (Goffman, 1974). Such footing shifts (Goffman, 1981) of embedding a figure within one's own speech (Goffman, 1974) are usually indicated by changes in perspective and deixis (Auer, 1988; Streeck, 2002; Ehmer, 2011; Stukenbrock, 2015). Demonstrations serve to make recipients recognize the demonstrator's intention to stage a scene (Clark, 2016).

2.2. Two kinds of depictions: Demonstrations versus illustrations

Many studies on demonstrating one's own or others behavior deal with referring to real events in the past. While studies on reported speech and direct quotes (Günthner, 1999; Holt and Clift, 2007) focus on verbal-vocal means, studies on reenactments include other multimodal resources, such as gestures, gaze, and body postures (Sidnell, 2006; Ehmer, 2011; Tutt and Hindmarsh, 2011; Thompson and Suzuki, 2014; Pfeiffer and Weiss, 2022).

In contrast to reenactments, demonstrations in instructional contexts show how certain behaviors are to be executed in the future. This is even true for “body quotes” (Keevallik, 2010), which can be used for exposing flaws in an instructee's previous performance they should avoid in the future. Thus, demonstrations are deployed here as a method of conveying embodied knowledge (Ehmer and Brône, 2021). In contrast to verbal descriptions, demonstrations convey a vivid picture of bodily movements, because most embodied knowledge is ineffable and can only partially be translated into conceptual categories (Ryle, 1949; Polanyi, 1966; Ehmer and Brône, 2021).

The use of demonstrations for instructional purposes has been investigated in a variety of different settings in which teaching, learning and developing bodily skills are in focus, e.g., in music and singing (Weeks, 1985, 1996; Haviland, 2007; Szczepek Reed et al., 2013; Tolins, 2013; Reed and Szczepek Reed, 2014; Emerson et al., 2017, 2019; Szczepek Reed, 2021), dance (Keevallik, 2013, 2015; Broth and Keevallik, 2014; Albert, 2015; Ehmer, 2021), theater and opera (Hazel, 2015, 2018; Lefebvre, 2018; Schmidt, 2018; Norrthon, 2019, 2021; Löfgren and Hofstetter, 2021), sports (Evans and Reynolds, 2016; Råman and Haddington, 2018; Råman, 2019; Evans and Lindwall, 2020), cooking (Mondada, 2014a), handy craft (Ekström and Lindwall, 2012, 2014), driving/flying lessons (Melander and Sahlström, 2009; De Stefani and Gazin, 2012; Deppermann, 2018) as well as medical training and surgery (Hindmarsh et al., 2011; Mondada, 2011a, 2014b; Zemel and Koschmann, 2014; Heath and Luff, 2021). In instructional activities, knowledge is not just conveyed monologically (as in manuals or lectures, for example), but developed dialogically in pairs of instructions and instructed actions (Arnold, 2012; Mondada, 2014b; Stukenbrock, 2014). In particular, when embodied skills are instructed, instructees display their understanding in situ when they implement the instructions, which allows instructors to correct directly if necessary (Hindmarsh et al., 2011; Mondada, 2011b; Zemel and Koschmann, 2014).

Szczepek Reed (2021) distinguishes “body-focused demonstrations” (p. 4), which are expected to be imitated (e.g., adopting a straighter body posture while singing), from “concept-focused depictions” (p. 6), which are not expected to be imitated but rather to be interpreted as illustrations of verbal descriptions to make the instruction more comprehensible (e.g., showing deeper breathing by using both hands to depict the movement of the chest while breathing). Combining Clark (2016, 2019) and Szczepek Reed (2021), we distinguish between demonstrative depictions, which convey how something should (not) be done and are expected to be imitated, and illustrative depictions, which convey how something should be interpreted and which are not expected to be imitated.

3. Data and method

Our study rests on 400 h of video recordings from three different professional theater productions in Germany in the years 2013–2019. Participants mainly speak German, although in one production they occasionally use English. The first production, “Der mündliche Verrat” (MV, “The Oral Betrayal”) written by Kagel (1983), is an absurd music theater play, in which sentences about the devil from different historical periods are spoken by three performers, accompanied by an orchestra generating experimental music and sounds. Although the play has a libretto, the lines of text are not structured as dialogue; yet they are performed on stage in distributed roles. The second production, “Nothing twice,” (NT), is a devised theater play (Perry, 2010), based on dance and graffiti. The performance features two professionals and four teenage amateurs. The third production is Tennessee Williams' (1947) drama “a Streetcar named Desire” (“Endstation Sehnsucht,” ES), which involves a staff of thirty members and was performed on the main stage of a major theater (“National Theater Mannheim”). Although the three productions are very different in terms of directing style, dramatic basis, size and prestige of production, degree of professionalism, genre of play, and degree of reliance on a script, the demonstrations we found are comparable in important respects.

We selected 265 instances in which directors use depictive means to instruct. In all instances, the depictive means are embedded in a director's instruction, which includes descriptive and depictive parts and which is sooner or later implemented by the actors.

We excluded cases in which demonstrations are not used to instruct but for other purposes, such as when

• actors use demonstrations to convey how they understood directors' instructions or how they would implement their instructions;

• directors use demonstrations to argue with actors but not to instruct them3;

• demonstrations are used to locate to which part of the script an instruction refers, e.g., singing a part of the score to identify a location in the play (see Ivaldi et al., 2021, p. 10 on “location cues,” Löfgren and Hofstetter, 2021, p. 8 on “location indexing depiction”).

In our collection, we first distinguished instructions in which depictive means were used only to illustrate what was said (e.g., instructing actors to accelerate their turn-taking, accompanied by a cyclic hand gesture illustrating “accelerating;” see 5.4.2, ex. 9) from instructions in which depictive means were also used to demonstrate what actors should do or modify to improve their performance (e.g., when an actress is shown how to swing a hammer; see 4, ex. 1).

Using the method of multimodal Conversation Analysis (Deppermann, 2013; Mondada, 2013), we produced detailed multimodal transcripts (Mondada, 2019a) to study how embodied demonstrations of directors are (a) sequentially incorporated in instructional activities, (b) how verbal and embodied means are coordinated temporally and (c) how they are responded to by actors. Multimodal transcripts are indispensable for showing the temporal progression of demonstrations concerning their onset, climax, and withdrawal (see Kendon, 2004, p. 108–127 on gestural phases). The form and meaning of demonstrations are furthermore described in detail in the corresponding analysis. We use still images to give an impression of the apex of demonstrations (see Stukenbrock, 2009 on the use of still images).

In most of our cases, a variety of meaning making means is combined to build instructions. N = 105/265 instances are merely or overwhelmingly illustrative.4 The remaining almost two thirds (160 cases) are instructions which rely essentially on demonstrations to instruct. We selected one case to show basic features common to all 160 demonstrations in our sample (4). On the basis of eight further cases, we show typical ways in which directors combine descriptive and demonstrative means when instructing actors (5).

4. Analysis part I: Basic features of demonstrations in theater rehearsals

What action is accomplished by some behavior can only be inferred when taking the context in which it is performed into account. This holds in particular for embodied actions that are only recognizable as demonstrations within their sequential context (Keevallik, 2010, p. 424). The sequential environment in which they are produced plays an important role. Both previous actions they respond to and subsequent actions are interpretative resources for participants and analysts alike to identify what actions were performed (Schegloff, 2007).

In theater rehearsals, participants develop a performance together, usually based on written sources (e.g., a dramatic script). The core of the rehearsals is the alternation between director's instructions and actors' implementations of these instructions on stage. In their instructions, directors usually instruct actors in how they may improve previous parts of their performance in subsequent repetitions. To this end, director's instructions often include demonstrations of how certain parts of the performance could be improved, which are expected to be taken up subsequently. The following extract (1) (Figure 1) epitomizes this core structure. After the actress (AS) finishes her performance (line 1), the director (D) provides a demonstration (lines 4–8), followed by a brief description (lines 9/10) of how she should improve her performance, which she immediately implements (lines 11–13).5

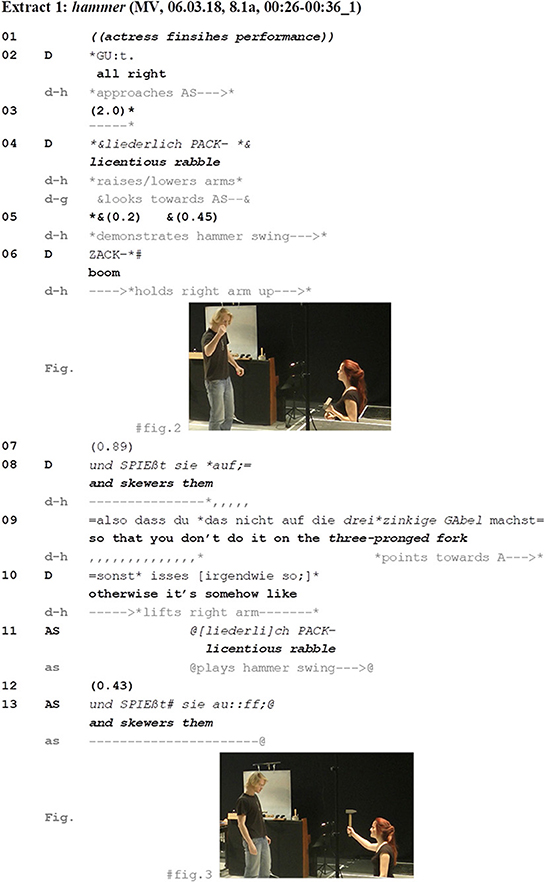

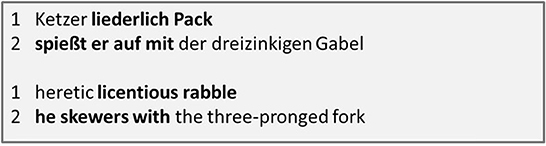

When AS reaches the end of her performance (line 1), D approaches her and marks the end of the play phase and the transition to a discussion phase with a generic evaluation term (“all right” in line 2, see Reed, 2019).6 In discussion phases, directors give feedback to actors based on what the actors have just shown on stage in the play phase (see 4.1 for a more comprehensive account of play and discussion phases in rehearsals). In extract 1, D begins his feedback with a demonstration. He repeats part of the actress's performance (her performance is not part of ex. 1), a hammer swing (Figure 2) together with the script text (lines 4–8). He adds a description (line 9: “so that you don't do it on the three-pronged fork”), which clarifies the focus of his instruction: he expects from the actress a more precise coordination of her embodied behavior (a hammer swing, Figure 3) and the spoken lines. The hammer swing is to occur in a pause between two lines7 at a fast tempo.

In D's instruction, embodied demonstration and verbal description are neatly coordinated. The description, realized as a complement clause, begins with so dass, “that” (line 9) and articulates a negative consequence that would be avoided if the actress follows his demonstration. In the description, he uses a pronoun (“it”) to refer to the hammer swing that was part of both her performance and his demonstration. In this way, embodied demonstration and verbal description amount to the instruction “do the performance in a way (=demonstration) that you don't do the hammer swing on the next text line.”

Before we have a closer look at D's demonstration itself and its features, we take a look at how it is embedded sequentially.

4.1. Sequential environment

In theater rehearsals, demonstrations are embedded in instructional activities, which are the primary means for developing a performance. The structure of instructional sequences is crucial for understanding D's movements as a demonstration. In the case discussed above, three similar movement patterns are produced in fast succession by different participants—the hammer swing and corresponding script text occurred first in the actress' performance (not part of ex. 1), subsequently in D's demonstration (line 4–8) and finally in AS's implementation (line 11–13). By virtue of their sequential placement, these similar movements accomplish different actions. Produced in the performance, they are part of the rehearsed play; as a part of D's corrective instruction, they are a demonstration; and in the actress's modified repetition, they are an implementation.

The three movements belong to a three-part sequence, which is constitutive of instructional activities: A part of the rehearsed performance (1) is retrospectively made relevant by D's corrective instruction (including a demonstration), (2) which is treated by AS as a directive to implement the corrected version (3).8

The demonstrations we focus on below are understood as instructions to improve yet-to-be-produced performance parts in the future, based on performance parts presented in the past. Therefore, our demonstrations must be interpreted in the context of the instructions in which they are embedded, and the instructions in turn must be interpreted in the sequential environment of an instructional activity aimed at developing a performance. Only in this context are certain movements and behaviors of directors understandable as demonstrations.

We now have a closer look at the demonstration itself.

4.2. Demonstrations instruct by showing not telling

The demonstration itself (lines 4–8) is a body movement designed to be recognizable as part of the performance. This is achieved by quoting lines from the script (lines 4/8) and by reproducing a choreographed movement (the hammer swing; Figure 2). Both are part of the participants' common ground concerning this particular production (see Deppermann and Schmidt, 2021). The director's demonstration integrates several multimodal resources into a gestalt (Ehmer and Brône, 2021; Stukenbrock, 2021), which exhibits a particular procedural structure (first a certain text line, then the hammer swing, then the next line), projecting and constraining certain next features within the gestalt (Deppermann and Günthner, 2015; Mondada, 2019b).

In contrast to the verbal description in lines 9/10, by his demonstration, he does not tell the actress, but shows her what to change. In contrast to verbal descriptions, which use “strings of arbitrary symbols to denote categories” (Clark, 2016, p. 342), demonstrations rest on iconic relations drawing on resemblance (Stoeckl, 2004; Clark, 2016, 2019).9 They depict and do not describe. To which part of the scene he is referring and what he expects AS to do does not rest on a detailed description but on reproducing some of its features. He swings his arm in a similar fashion and animates the corresponding script text. Since his instructional purpose concerns the precise temporal coordination between swinging the hammer and the speaking of the lines, the timing of embodied and verbal means is crucial.

Since demonstrations present scenes audio-visually, they rely on being watched by recipients. Demonstrators, therefore, often try to secure their co-participants attention and position themselves in space in a way that their demonstrations can be easily observed (Keevallik, 2010). In extract 1, in order to make his demonstration salient, the director approaches AS (line 2) until he reaches a facing formation and looks directly at her. Only then does he begin his demonstration, which AS follows closely, gazing at him throughout.

4.3. Demonstrations are expected to be imitated

The use of depictive means to refer to events and objects can be done in different ways. Typical and widely described means in the literature are iconic (also illustrative, imagistic, depictive or imitative) gestures [s. Kendon (2004, p. 84–107) for a review of gesture classification; see also McNeill, 1992; Streeck, 2009, ch. 6; Müller, 2010; Clark, 2016, p. 327; Urbanik and Svennevig, 2021] and direct reported speech (e.g., Clark and Gerrig, 1990; Keevallik, 2010) or reenactments (Sidnell, 2006; Pfeiffer and Weiss, 2022). However, unlike iconic gestures and unlike quotations or reenactments (e.g., in narratives), demonstrations in instructional environments are directive rather than assertive actions. They do not represent a past, anticipated or hypothetical event (see Niemelä, 2010; Cantarutti, 2020, ch. 2.2), but attempt to control a future event. Demonstrations are designed to be taken over (Szczepek Reed, 2021). When the director demonstrates the hammer swing, he shows a behavior which he expects the actress to do in the future.

That D's behavior in lines 4–8 is expected to be taken over (in part) is clear from his own subsequent description (line 9), which re-frames his performance as something that should (not) be done by the actress: “that you don't do ….” The actress immediately reproduces (lines 11–13; Figure 3) what the director has shown before (lines 5–8; Figure 2) and thus treats his behavior as a demonstration that is to be reproduced by her. However, a closer look reveals that not all parts of the demonstration are meant to be taken over. Rather, the demonstration is rhetorically shaped to convey how it is to be interpreted in order to understand what the director is focusing on in his instruction.

4.4. Rhetorical shape of demonstrations

Demonstrations include features that have rhetorical rather than depictive functions in order to make them understandable and to adapt them to the demonstrator's current purposes (see Clark and Gerrig, 1990; Clark, 2016 and Section 2 above). These features should not be seen “as something that the recipients have to discard in order to recognize only the depictive aspects (…), they should be seen as constitutive of the action” (Keevallik, 2010, p. 419). Demonstrations in theater are used by directors to convey something specific in the context of an instruction. Directors select certain aspects of a to-be-represented behavior and add others used as rhetorical techniques. Clark and Gerrig (1990) call them “annotative aspects” (see Section 2.1). These emphasize the focus of the demonstrations, often a corrective purpose (Weeks, 1990; Messner, 2020; Wessel, 2020; Stoeckl and Messner, 2021).

In extract 1, D adds aspects in his demonstration that are not to be taken over to clarify the focus of his instruction. He accompanies the hammer swing with the conventionalized sound quotation (cf. Clark and Gerrig, 1990, p. 788 et. seq.) “boom” (line 6) to emphasize both the focus of his instruction, namely the timing of the hammer swing, and one of its qualities, the suddenness and fast pace at which he expects it to be executed (see Keevallik, 2021 on the use of vocalizations to comment on simultaneous body movements in teaching dance). Although the expression “boom” itself draws on depictive means to generate meaning, it is not meant to be taken over in the actress's subsequent performance. Rather, in his demonstration, “boom” serves as a rhetorical technique or an “annotative aspect” (Clark and Gerrig, 1990, p. 768). In contrast, other aspects of the expected performance are left out, e.g., D does not kneel as AS does and he does not have a hammer (compare Figures 2, 3). By performing his demonstration without the prop (the hammer), D can execute it directly after AS has finished her performance without having to organize a prop exchange beforehand. In Clark and Gerrig (1990, p. 768) terminology, this serves as a “supportive aspect” of the immediacy of his demonstration. Other aspects of his demonstration are just “incidental” (ibid.; s.a. Section 2.1), e.g., his pose while standing.

This example nicely illustrates the two principles Clark and Gerrig (1990) and Clark (2016, 2019) formulated for all depictions including demonstrations: the partiality principle, according to which only parts of demonstrations are depictive and the selectivity principle, according to which demonstrations depict only selected aspects. Only the selected depictive aspects build the “demonstration proper” (Clark and Gerrig, 1990, p. 769), i.e., the intended referent of the depiction. Demonstrations can be more or less accurate or stylized (Wessel, 2020; see also Gullberg, 1998 on transitions between gestures and pantomime). The rhetorical shape of a demonstration results from what is selected, what is left out, and what is added. The “depictive aspects” that form the “demonstration proper” are not determined by semiotic criteria alone—action-related criteria must also be taken into account, i.e., as Clark and Gerrig (1990, p. 769) put it, what “the point of the demo” is. If the focus is on demonstrations (as opposed to illustrations), the “demonstration proper” includes the aspects that are meant to be taken over. As the case above shows, depictive and descriptive resources of meaning-making can be part of both the “demonstration proper” (e.g.: depictive: hammer swing; descriptive: imitated script text) and the annotative aspects (e.g.: depictive: “boom;” descriptive: conventionalized lexical meaning of “boom”).10

It is clear from AS's reaction that she is immediately able to make these distinctions. She neither reproduces D's posture (she remains kneeling and does not adopt a standing posture like D) nor his verbal comment (“boom”). Yet, she executes her re-performance with the hammer. The ways in which she implements the instruction indexes common ground stemming from different resources. “Boom,” for instance, is not part of the script. Concerning the hammer, D does not necessarily need the same equipment (here the hammer prop) to instruct by demonstrating, unless the prop itself would be in focus.

Following Clark (2016, p. 327–328), depictions (and also demonstrations) are characterized by two further principles—they are not what they depict (“pas une pipe principle”) and they have two realities, its raw execution (“base”) and its appearance, i.e., what is intended to be depictive (“double-reality principle”). Therefore, every demonstration consists of a “base scene” (its raw, observable execution), a “proximal scene” (its appearance or intended depiction) and a “distal scene” (what is depicted in a there-and-then). In the case above, the director combines a variety of perceivable multimodal resources (in Clark's terminology the “base scene”) to enact a scene to be imagined (the “proximal scene”) as a model for a future implementation by the actress (the “distal scene”).11

Since every “base scene” is construed according to an “interpretive framework” (Clark, 2016, p. 328), “there is no such thing as a depiction simpliciter” (ibid.), i.e., “one cannot know what a base scene depicts without knowing or inferring what its creator intended it to depict” (ibid.). What a demonstration demonstrates has to be inferred. In the case above, the director's interpretative framework is indicated by annotative elements (“boom,” for instance, highlights the place where the hammer swing should take place) and his following verbal description (“do not do X”). Instead of showing the actress exactly how to perform the part in question, the director embodies in his demonstration primarily what his instruction focuses on.12 This is in line with Streeck (2008, p. 286) who claims “(…) that the gesture that depicts an object or process of any kind offers a construal or analysis of the signified, an ‘active' organization.”

None of the 160 cases we studied, in which the director uses demonstrations to instruct, is produced without verbal means. Thus, the combination of descriptive (telling) and demonstrative (showing) means in directors' instructions in rehearsals is the only practice in our data. In the following section, we provide an overview of different ways in which language figures in demonstrations and we show how language is coordinated with demonstrative means in directors' instructions.

5. Analysis part II: Verbal and demonstrative means in instructions in theater rehearsals

As in extract 1, all demonstrations in theater rehearsals in our data are embedded in instructions that draw on descriptive means, typically language. In the following we take a closer look at how and for what purposes directors combine descriptive and demonstrative means in their instructions. We ask: What are the contributions by the descriptive and by the demonstrating parts and what is achieved by combining them in certain ways? A closer look reveals that language in instructions including demonstrations can have very different statuses. It can be used to

• build the demonstration itself (5.1),

• delineate the demonstration and integrate it in the overall instruction (5.2),

• distinguish positive (how to do something) and negative (how not to do something) versions of demonstrations (5.3),

• provide verbal descriptions of the instructional purpose of demonstrations (5.4).

5.1. Language as part of the demonstration itself

Since drama involves speech, language use can be the focus of the demonstration proper. Then language is used in a quotation function (Clark and Gerrig, 1990) as is typical for reported speech (Holt and Clift, 2007). Alternatively, language can be used to frame, comment on or explain a demonstration. Then it is not part of the demonstration. Consider extract 1 again (here reproduced as ex. 2, Figure 5):

D here uses language to build his demonstration. In line 4 (“licentious rabble”) and line 8 (“and skewers them”), he quotes text from the script (see Figure 4), contextualized as part of the demonstration by theatrical standard pronunciation (significantly louder and more articulate). Similar to singing (Stevanovic and Frick, 2014), the animation of scripted text draws on “a composition, which has been created by someone else” (p. 4), clearly indicating a shift in authorship. Language taken from the script together with certain parts of D's embodied behavior is integrated into a multimodal gestalt understood by AS as a demonstration of how the shown part should be played instead.

Although D also cites the noun phrase “three-pronged fork” (line 9), which is part of the script as well (Figure 4), it is not understood as part of his demonstration. In her subsequent implementation (lines 11–13), AS repeats exactly the lines that D has used in his previous demonstration (lines 11/13 repeat lines 4/8), stopping after “auf ” (line 13) and before “with the three-pronged fork,” which would be the next words in the script (Figure 4). Quoting from the script here serves different purposes. On the one hand it feeds into a demonstration showing how to coordinate body movements and speaking the script, which is meant to be imitated; on the other hand it is used to refer metonymically to a certain line of the script (saying “on the three-pronged fork” quotes the noun phrase “three-pronged fork” to indicate “on” which text line she is not to perform the hammer swing), which is not understood as a demonstration to be imitated.

5.2. Language as verbally delineating and embedding demonstrations

When language is not an integral part of the actual demonstration, it is often used to identify parts of the instruction as a demonstration. A basic interactional task when using demonstrations is to make clear which parts of an instruction are to be understood as demonstrating and which are not. In addition to recognizably reproducing parts of the performance or using lines from the script, certain segments of behavior are often verbally framed as demonstration (Keevallik, 2010, 2015; Cantarutti, 2020, p. 134–167).

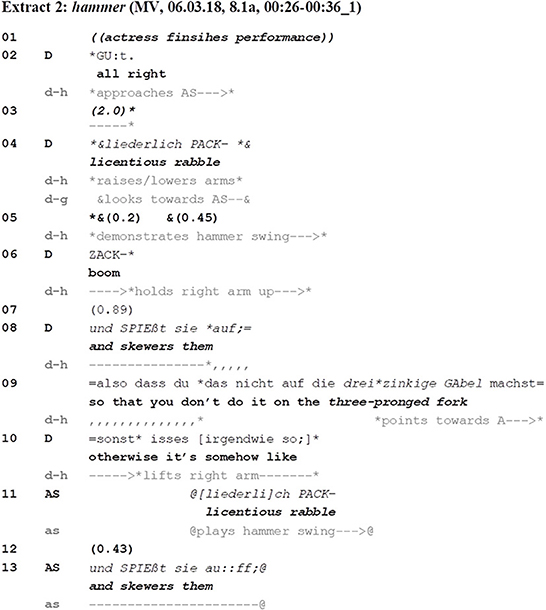

In extract 3 (Figure 6), a director (D) and an actor (A) discuss a scene in which the actor combines dance moves with reciting a poem. At several points, the actor should stop and adopt a thinking posture. They are discussing how to make these postures. So far, the actor has adopted the pose only in one way (sitting). D now demonstrates that A could also do the pose lying down. The transcript starts with D suggesting verbally that A could vary the shape of the pose (line 1: “but it can also be another shape”).

D introduces his following demonstration not by describing the posture in detail. Saying “but it can also be another shape (…) that just…that… just like that” (lines 1–6), he prospectively frames it generically as something additional (“another shape”). When he twice starts a complement clause (line 3: “that just,” line 4: “that”), which he finally abandons, he projects something to follow (a verbal specification of “another shape”). At the same time, his self-repairs delay his verbal conduct, which allows him to prepare his following demonstration, getting up from his chair and sitting on the floor, which is the starting position of the actor's thinking pose and his demonstration (Figure 7).13 Immediately after saying the second time “that” (line 4), he begins to change his position from sitting to lying down on the floor. The process of adopting the pose is accompanied by another referential verbal framing (“just like that,” line 6). By the delays, he adapts his unfolding verbal description to the embodied affordances of producing the projected posture (see Mondada, 2009). In regards to dance instruction, Keevallik (2015) has referred to this as “scrolling” (321), i.e., matching temporalities afforded by language to those afforded by embodied demonstrations. The posture itself and its demonstrated possible shape is referred to by pronominal (prospectively in line 1: “it”) and demonstrative means (overlappingly in line 6: “that”), whereby D assumes common ground of what is salient (the thinking posture).

Following Clark (2016, p. 325), quotes, depictions and demonstrations can be embedded or indexed by language. In this extract both methods are recognizable. First, D provides a demonstration to continue a complement clause (lines 1–4: “but it can also be another shape, that just...” X is done = “demonstrating the pose”). With this he embeds his demonstration in a syntactic frame. Keevallik (2015) calls such constructions “syntactic-bodily gestalts” (309): a verbal fragment (in this case “that just”) is complemented by embodied conduct (the demonstration of the pose) to form an intelligible action. Secondly, D uses the modal deictic “so” (“just like that,” line 6; Stukenbrock, 2014, 2021) to point to his pose. The deictic phrase draws A's attention to the pose D is demonstrating. While the provision of a generic category (l1: “another shape”) describes what his demonstration represents, the use of a “syntactic-bodily gestalt” including a modal deictic item indexes his demonstration. The latter specifically requires the recipient to attend to the visual modality—only if one sees the demonstration is the deictic expression comprehensible (Stukenbrock, 2014). In addition, D stretches “so” while he is lying on the floor, making the process of adopting the pose more salient.

In extract 3, language is used to foreshadow (“another shape”), embed (demonstration complements sentence), bracket (verbal introduction at the beginning and referring to the demonstration in parallel at the end), and index (“like that”) those parts of his composite action which are to be understood as a demonstration (see also Cantarutti, 2020, p. 134–167). As in reenactments, usually left brackets, the onsets of a depiction, are marked more explicitly by verbal introduction (as in this case: “another shape that just…just like that”), whereas the right brackets, marking where a depiction ends, are often left more fuzzy, usually only signaled by a reorientation of speakers' gaze to their addressees (Sidnell, 2006). Similarly, in extract 3, D holds the pose for half a second (line 7), until A displays understanding (line 8: “yes….”); only then does he return to a sitting position and redirects his gaze to A.

5.3. Contrast pairs: Verbally signifying what to do and what to avoid

While verbal brackets do not contribute substantively to the content of an instruction, a verbal framing can also clarify whether the focus of an instruction is not primarily or exclusively on showing what actors should do, but what they should not do. In such cases, directors often use contrast pairs (Weeks, 1990; Keevallik, 2010; Messner, 2020; Wessel, 2020): demonstrations of what not to do (negative version) are contrasted with demonstration of what to do instead (positive version). In contrast pairs, verbal means are crucial to distinguish between the positive and the negative status of a demonstration.

In extract 4 (Figure 8), a scene is rehearsed in which the actors perform with flashlights on a totally darkened stage. The director (D) instructs two actors (A1, A2) on how to use their flashlights:

D introduces his first demonstration of how to use the flashlights by a verbal introduction, which uses deictic reference as in extract 3 (line 2: “what isn't working is this”). By prefacing negative pseudo cleft clauses (line 1 “what is disturbing,” line 2 “what isn't working,” see, e.g., Hopper, 2004; Günthner and Hopper, 2010; De Stefani et al., 2022), the following indexed (line 2: “this”) demonstration (line 2–5 waving around with a flashlight) is characterized as something that should be avoided. In his following second demonstration (line 6), he shows what the actors should do instead (producing a resting flashlight cone). It is accompanied by a contrastive formulation from which the positive version is inferable (line 6: “actually it should be the goal that you don't seek but that you find”).

Without verbal means, it would not only be difficult to identify which of the flashlight movements are to be understood as demonstrations; it would be completely impossible to distinguish which movements are to be avoided (negative versions) and which ones should be produced (positive versions). While language has the capacity to express coherence relations, such as “either—or,” “if—then,” and abstract meanings, this is hardly possible by analogous means of communication, such as embodied demonstrations. In particular, they lack “a simple negation, i.e., an expression for ‘not”' (Watzlawick et al., 1969, p. 66; English translation by authors).14

The verbal means on which we focused in the cases in 5.1–5.3 above do not provide an independent description of the instructed behavior, but serve as means to build (5.1), bracket and embed (5.2), or assign positive or negative value to a demonstration (5.3). We now turn to cases in which language contributes more substantially to co-construct the instructional content.

5.4. Relations between descriptions and demonstrations: Show and tell

In all our cases, directors use descriptive and depictive means to instruct how certain parts of a scene should be played. They show and tell. In the pursuit of accomplishing the instructional purpose, semiotically different means are systematically combined [for similar observations in music instructional settings see Weeks (1996) and Stevanovic and Frick (2014)].

In the rehearsals we have analyzed, the relationship between demonstrations and descriptions depends on the focus of the instruction. Sometimes, instructions focus on content-related entities of the fictional world created on stage (5.4.1), i.e., actions (e.g., “limping”), behaviors or states (e.g., “hyper-attentive”), or social categories (e.g., “school girl”). In other cases, instructions focus on formal aspects (5.4.2), e.g., temporal relations between turns, or between spoken text and embodied actions. Depending on the focus of the instruction, the relationship between demonstrations and descriptions is different.

5.4.1. Instructions focusing on content-related entities

One of the most important properties of language is its ability to categorize. In instructions, verbal descriptions are often used to categorize what the demonstration is to represent. Demonstrations, in turn, deliver a concrete and vivid sample of the category; they instruct by exemplifying what is described verbally.15 In his classification system of quotative content, Terraschke (2013, p. 66) considers to “exemplify a concept or idea” to be a typical use of quotations. The use of both—a verbal categorization and a related embodied demonstration—leads to a disambiguation of meaning.

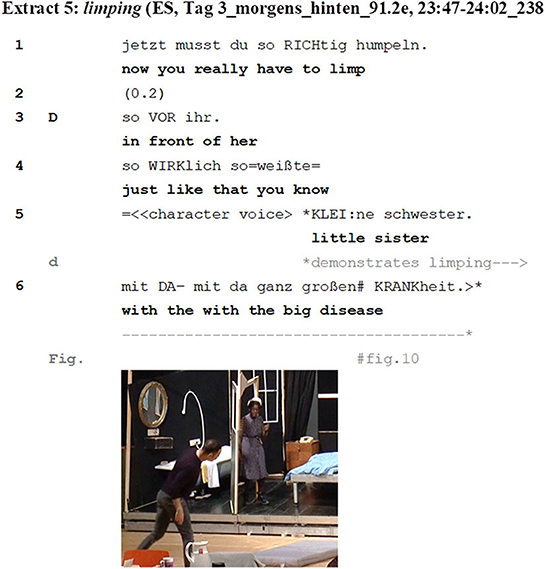

As with all depictive gestures, demonstrations enacting things known from the real world (e.g., “a school girl,” “being hyper-attentive,” or “limping”) “are formed by incorporating bodily knowledge of the social world” (Hall et al., 2016, p. 83) in a selective way. This is most obvious when directors use action verbs to categorize demonstrations, as in Extract 5 (Figure 9) when the director (D) instructs AS to exaggerate her limping (line 3):

The aim of his instruction is first described (line 1: “now you really have to limp”) and subsequently demonstrated (lines 5/6; Figure 10). D first provides a verbal category (“limping”), which then is exemplified by demonstration. Simultaneously with his demonstration, he delivers a description animated in character voice (lines 5/6: “little sister with the very big disease...”).16 Since this is not part of the script, it can be heard as a commentary describing the character's strategy in limping so exaggeratedly in order to arouse her sister's pity (indicated in line 3: “in front of her,” referring to the sister).

However, the verbal description does not only categorize what the demonstration is to represent (“limping”). At the same time, it introduces a gradation (line 1: “now you really have to limp”) that makes the demonstration readable as an exaggerated display, which could hardly be expressed by the demonstration alone. Moreover, the accompanying subtext17 (lines 5/6: “little sister…”) does not only explicate the figure's strategic aims, but also accounts for his suggestion—if she wants to arouse pity, she has to limp harder.

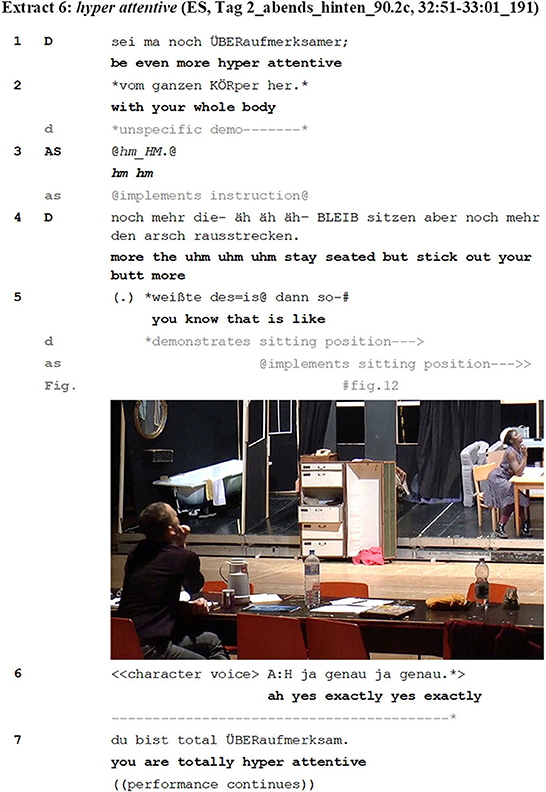

Demonstrations can also be categorized in terms of the type of social behavior. In Extract 6 (Figure 11), D instructs AS to be “hyper attentive” (line 1) and demonstrates possible behaviors for how to implement it:

In the first part of his instruction (lines 1/2), the director provides a verbal category “hyper attentive” (line 1) and specifies the resources to be used (line 2: “with your whole body”), accompanied by an unspecific demonstration rapidly moving his body forth, while gesticulating with both arms (line 2). AS follows his instruction by an embodied “proposal” (Löfgren and Hofstetter, 2021, p. 1), leaning forward and lifting her body slightly from the chair (line 3). In the second part (lines 4–6), the director corrects AS's previous implementation with a more detailed description (line 4: “stay seated but stick out your butt more”) and a more specific demonstration, which shows partly what he describes. He leans forward, stretches out his butt, puts his hand under his chin and produces a subtext in character voice readable as hyper-attentiveness (line 6: “ah yes exactly yes exactly”). AS implements D's instruction, while D is still demonstrating (line 5), adopting a posture very similar to his (Figure 12). Finally, D re-categorizes the developed form (“you are totally hyper-attentive,” line 7), which at the same time confirms and reinforces AS's performance and his instruction.

Across the two parts, the verbal descriptions become more concrete (from the mood adjective “hyper-attentive” to the behavioral description “stick out your butt more”), as do the accompanying demonstrations (from a very unspecific gesticulation in line 2 to a specific pose in line 5). This is obviously due to AS's implementation in line 3, which offers a specific sitting posture (“leaning forward”). Her posture is picked up by the director, who verbally corrects a detail (line 4: “stay seated, stick out your butt more”) and at the same time demonstrates a concrete posture that she immediately adopts (Figure 12).

Extract 6 nicely shows how verbal descriptions and embodied demonstrations elaborate each other. The instructional sequence begins with a verbal category (line 1: “hyper-attentive”), which is elaborated in its behavioral details in two consecutive sequences of instructions and implementations (lines 1–3 and 4–6). Finally, it is (re-)confirmed by D applying the same category he used initially (line 7: “hyper-attentive”).

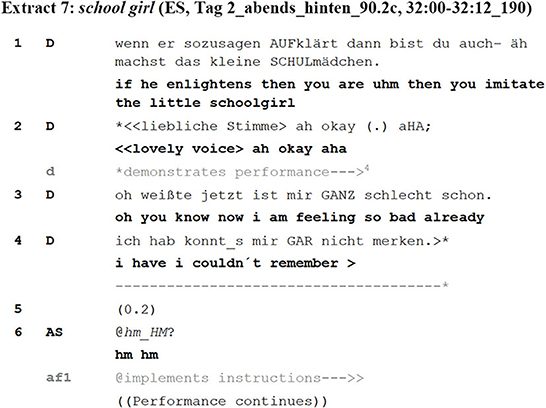

In other cases, social categories are used as descriptions for demonstrations. In extract 7 (Figure 13), D instructs A to act as a “school girl” (line 1). He demonstrates her behavior:

D's instruction starts with a description in which he implicitly relates two social categories (line 1: “he enlightens” vs. “you are/imitate the little school girl”) by an “if-then” construction (“if he does this, you do that”), which embodies a relationship of epistemic asymmetry [“knowing husband, (apparently) ignorant wife”]. In the following demonstration, he embodies the category “school girl” he expects her to play. His demonstration is a full-fledged enactment (s. Keevallik, 2010, p. 421 et. seqq.; see also Löfgren and Hofstetter, 2021), similar to staging scenes in make-believe plays (Clark, 2016, p. 329–330), combining movements with (sub-)text animated with the voice of the enacted character (lines 2–4: “ah okay aha, oh, you know, now I am feeling so bad already, I have, I couldn't remember”). D's demonstration is understandable as a category-bound activity of the membership category (Sacks, 1972) “school girl.” His demonstration is not meant to be taken over as such. It portrays a stereotype which he expects AS to adopt by creating own ways to enact it. In her subsequent performance, she implements D's instruction by producing excessive backchannel behavior (starting in line 6: “hm hm”) and talking in a sweet high voice. Both are variations of the behavior D had demonstrated.

In extract 7, D does not depict a concrete action, but a broader type (Clark and Gerrig, 1990, p. 767), which tends toward a cliché, in part because AS is instructed to pretend (line 1: “you imitate the little school girl”). Using enactments for crafting caricatures is common (Günthner, 1999; Streeck, 2009; Goodwin and Alim, 2010; Hall et al., 2016).

5.4.2. Instructions focusing on formal aspects

In the cases discussed in Section 5.4.1, verbal means are used to describe the core of the instructed behavior. Yet, the focus of instruction can be more aspectualized and formalized. Descriptions can be used to explain how demonstrations are to be interpreted, and demonstrations can be more stylized to deal with formal aspects of the performance. Extract 8 (Figure 14) is a case in point.

D explains A how the text should be spoken. The script prescribes a “loud scream” followed by the text line “flown away is gedenke mein.” D first explains that there is no separate scream, but the text line is to be animated screamingly (lines 1–3). To support his reading of this passage of the script, D demonstrates it (lines 5–6).

First, he quotes the part of the script that he thinks should not be realized (spoken in a soft voice in line 5: “a loud scream”), followed by a full-fledged demonstration of the part that he thinks should be spoken screamingly (line 6: “flown away is gedenke mein”). He shouts to represent the scream and raises both arms, a gesture that is also used when this line of text is performed on stage. A treats D's reading of the script as new information by producing a “change-of-state token” (Heritage, 1984) (“aha” in line 8). After a short negotiation, A accepts D's interpretation (not part of the transcript) and reproduces D's demonstration in his later re-performance of this part of the scene.

The main purpose of D's demonstration is not to show A how he should play the passage, but to explain (and convince him) how the script is to be understood—which is a precondition to play it properly. The demonstration in this case is primarily used to make his interpretation intelligible. Correspondingly, the actor's first response is not an implementation, but an expression displaying his altered knowledge (line 8: “aha”). Nevertheless, D's instruction includes a depiction that does not only illustrate an idea, but also demonstrates the way in which A should adopt it (speaking the text with a screaming voice), what A does in his next implementation.

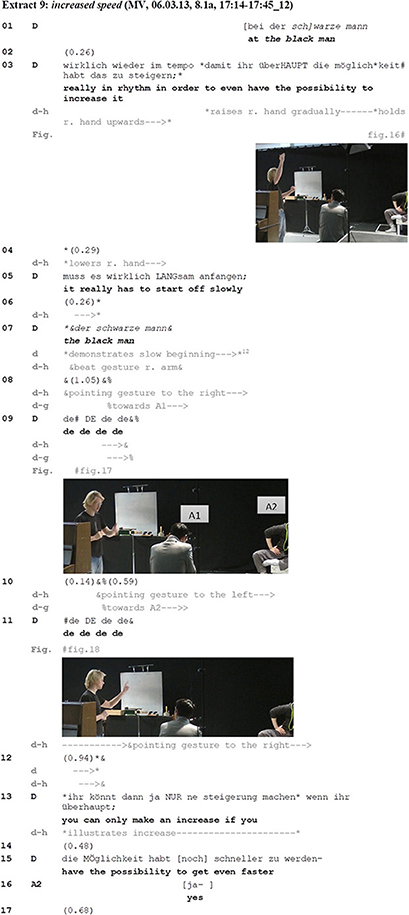

Demonstrations can be highly stylized to clarify the underlying idea, as in extract 9 (Figure 15). The director (D) focuses on the speed of the actors' (A1 and A2) turn-taking:

D instructs the actors to accelerate their turn-taking. To make this possible, the actors have to begin in a slow pace. First, D verbally describes his idea, supported by gestures illustrating accelerating (lines 1–5, Figure 16), followed by a demonstration (lines 7–12, Figures 17, 18).

His demonstration is highly stylized, focusing on the aspect of starting in a slow pace in order to be able to accelerate the turn-taking. He uses non-lexical vocalizations (Tolins, 2013; Keevallik and Ogden, 2020) (lines 9 and 11: “de de de de”) to symbolize spoken lines, abstracting from concrete wording and its possible pronunciation (see Clark and Gerrig, 1990, p. 780 on “quotations without propositional content”). He also alternately turns his body to gaze at each actor as he demonstrates the accelerated turn taking and points at the actor in turn who is to speak the respective dummy lines (Figures 17, 18). He terminates his demonstration by repeating his claim (lines 13–15: “you can only make an increase if you have the possibility to get even faster”), what is confirmed by A2 (line 16: “yes”).

The embodied temporality of turn-taking together with gaze and pointing shifts serve to underscore the instructional focus of the demonstration—starting at a slow pace to be able to accelerate turn-taking. The demonstration is highly stylized, it is not meant to be implemented as such: The actors are not expected to turn their bodies, point and gaze at each other, and, of course, should not produce dummy syllables. The proportion of “depictive elements,” i.e., elements that D expects the actors to reproduce the way they were shown, is low. One reason is that the demonstration does not refer to the behavior of one person, but to a relationship between two people. Evans and Lindwall (2020) show concerning teaching basketball, in “multiparty demonstrations” (p. 1), which “involve the contributions of multiple interacting parties” (p. 2), “the coach must (…) recruit codemonstrators and direct their actions” (p. 5) to achieve a realistic demonstration. This is exactly what the director in extract 9 does not do. The main purpose of his demonstration is not to show behaviors that the actors should imitate, but to highlight properties that should inform the actors' performance. Nevertheless, parts of his demonstration, especially the accelerated tempo of turn-taking, should be adopted in the actors' play.

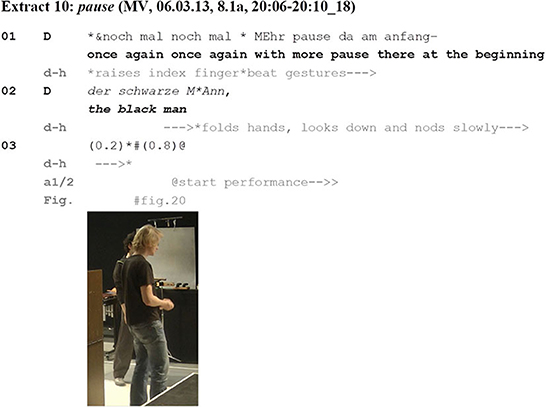

Extract 10 (Figure 19) is an example of the instructional focus being on something that is difficult to demonstrate, in this case a pause:

D instructs the actors to play the scene again (line 1: “once again”) with a modification, which he first describes (“with more pause there at the beginning” in line 1). In his ensuing demonstration, he quotes a line from the script (line 2: “the black man”) followed by a pause (line 3). The demonstrated pausing is only recognizable as such by producing surrounding auditory phenomena. Both his verbal description and the accompanying beat gestures (line 1) direct the focus to temporal-rhythmic properties. Reciting a line from the script (“the black man,” line 2) marks his behavior as a demonstration and provides the left bracket of the pause. D emphasizes the duration of the following pause by adding annotative aspects—slow rhythmic nodding of the head (reminiscent of a clock or a metronome counting time units) and a posture symbolizing “waiting” by looking down with folded hands (lines 2/3; Figure 20). The behavior shown in the demonstration should not be taken over identically. The demonstration embodies the duration of the pause, which would remain unclear by verbal description alone (how long is “more pause”? see Stevanovic and Frick (2014, p. 8) for a similar argument in the case of singing). Still, the depiction again is not limited to illustrating an idea. Parts of his demonstration, namely the spoken text and the length of the pause in-between, should be and are reproduced when both actors restart the performance (after the extract).

6. Conclusion

This paper has analyzed how directors use demonstrations to instruct actors in theater rehearsals. We have shown

1. What embodied demonstrations achieve compared to verbal descriptions, and how they are embedded in surrounding activities,

2. How language features in embodied demonstrations, and

3. How verbal descriptions and embodied demonstrations are combined in instructions.

6.1. Demonstrations

When studying demonstrations, two seemingly contradictory properties strike us: They use depictive means to communicate; at the same time, they use rhetorical means, which are not meant to be depictive. In Clark's (2016) staging theory, depictions are seen as physical analogs of the referents they depict, adapted to the actual situation by merging selected depictive aspects and added non-depictive aspects into a gestalt intended to convey a proximal scene for a current interactional purpose. Depictions are therefore never exact copies of the “distal scenes” in a “there-and-then.” Rather, they are selective and come with annotative aspects that, taken together, provide an interpretive framework rhetorically shaping the to-be-inferred “demonstration proper.”

Demonstrations are only intelligible in their sequential context. In our cases, they are embedded in instructions of directors aimed at developing a performance together. Instructions of directors usually seek to improve actors' previous performances by instructing future actions. Therefore, demonstrations are not sufficiently characterized by classifying them as using a depictive semiotic mode.18 By virtue of being embedded in instruction sequences, they obtain representational qualities that distinguish them from depictions in general. These qualities arise from their action-related function concerning contextually grounded expectations about what is to be imitated in the actual practical context and what is not (Szczepek Reed, 2021).

Demonstrations are similar to reenactments, quotations and direct reported speech in being realized as separate components of a larger instructional action, marked and framed by vocal or embodied resources or combinations thereof (s. Cantarutti, 2020, p. 134–167) as representations of a displaced action. When language is used concurrently with the demonstration, it is treated as a part of the demonstration (as quoting a script) or as an annotative aspect commenting on it, but not, as is usual for depictions and illustrative gestures, for contextualizing talk.

In contrast to quotes and reenactments used in stories, demonstrations model future events. They are produced as instructions to implement parts of the shown behavior. This is due not only to the ways in which demonstrations are constructed (Sections 4.2 and 4.4) and their sequential placement (4.1), but also because they are embedded in directive framings.

6.2. How language features in embodied demonstrations

All of the demonstrations we investigated come with verbal utterances. Language fulfills a variety of functions to make demonstrations intelligible. Since demonstrations are realized as component (not concurrent) parts of instructions, they are typically bracketed by introductory verbal framings of their beginning (as in ex. 4/line 2: “what isn't working is this”) and often followed by descriptions or accounts marking their endings. The demonstration itself can be additionally made salient by practices of emphasizing, e.g., using a theatrical voice or making the body noticeable by adopting a visible position and/or exaggeration (see also Ivaldi et al., 2021, p. 8 et. seq.; Keevallik, 2010). In these respects, demonstrations are again similar to quotes and reenactments.

However, verbal material can also be used concurrently to build the demonstration. Language can either be part of the “demonstration proper” (as with script texts) or comment on the demonstration in parallel. In separating depictive from non-depictive parts that are to be imitated, actors rely on different sources. In addition to instructional framings provided locally, common ground (concerning occupational practices, the script text, etc.) and the interactional history concerning previous agreements about the performance play a crucial role (on iterativity in rehearsals see Hazel, 2018; Hsu et al., 2021b; Löfgren and Hofstetter, 2021; on the emergence of common ground over interactional histories in rehearsals see Deppermann and Schmidt, 2021; Schmidt and Deppermann, in press).

All instructions we analyzed contain verbal materials that indicate how a demonstration is to be interpreted. Directors treat demonstrations as being in need of additional descriptions that clarify what they are supposed to represent in order to be comprehensible for the actors, thus providing clues as to what should and should not be adopted by the actors and in which way. Verbal description clarifies the status of demonstrations (e.g., by gradation, negation, contrast formats, or by establishing an “if-then”-relationship). Such clarifications cannot be accomplished by demonstrations alone. More elaborate descriptions accompanying the demonstrations provide an instructional focus making demonstrations intelligible.

6.3. How more elaborate verbal descriptions and embodied demonstrations of the same instructional focus are combined

There is a division of labor between telling and showing: Directors' descriptions provide an interpretative framework for how to interpret demonstrations, whereas demonstrations make parts of to-be-imitated physical movements tangible. In particular, demonstrations make behavior that is difficult to describe or partly ineffable more accessible for recipients. “Ineffability is a strong reason for quoting instead of describing” (Ryle, 1949; Clark and Gerrig, 1990, p. 793; Hsu et al., 2021a,b).19 Both verbal descriptions and embodied demonstrations are indispensable parts of directors' instructions and mutually elaborate each other (Goodwin, 2018, ch. 8).

Verbal descriptions and embodied demonstrations stand in a reflexive relationship to each other: verbal means categorize what a demonstration is to represent; demonstrations show how what is specified by verbal means is to be realized. This reflects the two aspects that instructions in theater always orient to, namely a concept (or idea), which has to be bodily implemented. Szczepek Reed (2021) argues that conceptual meaning and their embodiment are two sides of a coin in instructions—sometimes being more “body-focused,” sometimes being rather “concept-focused.” Directors not only introduce a concept, but they often also show—at least in part—how this concept could be played.

It has to be noted that verbal descriptions can be more or less detailed, ranging from just providing a category to elaborate descriptions and accounts, and embodied demonstrations can be more or less accurate and holistic vs. highly stylized (Section 5). Less detailed descriptions are often accompanied by more elaborated demonstrations, whereas elaborate descriptions accompany rather stylized demonstrations. These variations depend on whether instructions focus more on content-related entities such as actions, ways of behaving or social categories (Section 5.4.1) or on more formal aspects, as, e.g., the coordination of temporal relationships (Section 5.4.2).20 Demonstrations focused on formal aspects tend to be stylized and in need of more elaborate descriptions and occasionally accounts to make clear what the demonstration aims for. If demonstrations focus on content-related entities, in contrast, it is often sufficient to provide verbal categories (as “limping,” “hyper attentive,” “school girl”) to make the idea that informs the instruction clear. These categories are accompanied by full-fledged demonstrations of the director. In our data, demonstrations tied to enacting categories of behavior or persons do not show concrete behaviors that are meant to be imitated exactly, but they perform types metonymically that provide a basis for the actors to develop their own ways of suitable realization.21 This is supported by the director enacting a social category but using subtext which in some cases is not even animated in a character voice. Nevertheless, the demonstration contains aspects which are to be taken over. Demonstrating types comes close to illustration, yet without being only an illustration. Further research is needed on the relation of illustrations and demonstrations and how it relates to whether depictions or demonstrations represent concrete behaviors as opposed to types. This is particularly relevant for theater, as instructing types seems to be a creative practice by directors to elicit actors' own ideas for performing a scene, on which directors can subsequently build.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study are from a private corpus, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

Both authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Funding

This study was funded by the Open Access Fund of the Leibniz Association and by the Leibniz-Institut für Deutsche Sprache.

Acknowledgments

We thank the National theater Mannheim and all those involved in the productions in which we participated as researchers for their consent to be filmed. We also thank Matthew Bruce Ingram, Marjo Savijärvi, and Agnes Löfgren, who conducted the reviews and helped improve our article with their comments and suggestions, and the editor Bettina Bläsing for carefully coordinating the review and publication process. Thanks also to Barabra Fox, who helped us improve our English, and to Christiana Bader, who prepared the transcripts and did the editing.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^Aesthetic concepts are frameworks (often developed and communicated in advance) to which the entire production is oriented (e.g., a “comic” or “dark” mood of the play, which can manifest itself in dimensions as diverse as the acting, the lighting design, or the costumes). See Deppermann and Schmidt (2021) on the development of an unknown aesthetic concept during rehearsals.

2. ^We use the terms “verbal means/descriptions” and “language” synonymously to emphasize the dependence of descriptions on a code system whose specific properties (arbitrariness, based on discrete categories, conventionality etc.) categorically distinguishes its use from the use of non-linguistic means of meaning production, typically generated by body movements. Of course, speech can be used depictively, i.e., iconically, as in ideophones (Dingemanse, 2013; Clark, 2019) and the body can be used descriptively, i.e., symbolically, as in sign language or by using gestural emblems (Ekman and Friesen, 1969). In addition, language can be (part of) a demonstration (e.g., in the form of quotations) and embodied depictive means can be used in verbal descriptions (e.g., as in accompanying iconic gestures).

3. ^Demonstrations used for argumentation purposes show what a behavior would look like if it were performed. The main purpose here is to convince actors that choosing the demonstrated behavior is useful. These demonstrations are usually not responded to by imitations, but by agreement, disagreement, or counter-proposals.

4. ^Directors often combine illustrative and demonstrative means in their instructions. We counted cases as “overwhelmingly illustrative” in which the focus of the instructions is on explaining and illustrating concepts rather than demonstrating how to perform them.

5. ^Verbal conduct is transcribed according to GAT2 (Selting et al., 2011), embodied conduct according to Mondada (2019a). If necessary, embodied conduct is separated in gaze (abbreviated with “g”) and gestures/hand movement (abbreviated with “h”). Lines from the script are rendered in italics.

6. ^Quotations from the script are indicated by single quotation marks and italics and are in English. The German wording can be taken from the transcript. Transcript lines are referred to with “line + number.”

7. ^Figure 4 shows the script text, quoted parts are marked in boldface.

8. ^Such sequences share features with initiative-response-evaluation sequences in learning settings (McHoul, 1978; Mehan, 1979). However, see Schmidt and Deppermann (2021) on how instructional sequences in creative settings, such as theater, differ from them.

9. ^The notion of resemblance has been prominently criticized by Goodman (1968; see also Streeck, 2008, 2009). He argues that an apparently iconic representation (e.g., a painted bird) does not refer to a represented object (e.g., a bird) on the basis of resemblance, but on the basis of convention. Proponents counter that the relationship is not completely arbitrary (as with symbols), but is based at least on some similarities (e.g., the color or shape of the bird is emulated). Furthermore, the referents of most depictions are only recognizable if the referent is already known (Goodwin, 2011). The current paper shares this view, as certain features of the performance are recognizably imitated in demonstrations (drawing on resemblance) and not just described (drawing on convention). In all cases, to what the directors' depictions refer is clear either from its reference to the play/script and/or his descriptions.

10. ^Quotations for instance, treated as a canonical case of demonstration (Clark and Gerrig, 1990), are considered as “depictions of descriptive speech” (Hsu et al., 2021a, p. 11).

11. ^Representations in rehearsals are always representations of representations (e.g., the hammer swing in the rehearsal demonstrates a depicted hammer swing in a performance on stage), which can be viewed either from “inside” (e.g., used in rehearsals for instructions) or from “outside” (e.g., created to evoke certain effects in an audience). Löfgren and Hofstetter (2021) speak of “introversive” and “extroversive semiosis” (2). Since we focus exclusively on “introversive semiosis” in our analysis (i.e., how demonstrations are used in the practical context of rehearsals to build instructions), we consider the “distal scene” as a model for future implementations by actors rather than as a representation on stage “externally referencing to prototypes of mundane behavior” (ibid.: 2).

12. ^Another detail supporting this point is that the director does not quote the script exactly—instead of saying “he skewers with” (see script/Figure 4, line 2), he says “and skewers them” (ex. 1, line 8). Interestingly, in line 13, the actress, does not quote the correct line, either, but repeats the director's words (“and skewers them”). The focus here is not on the reproduction or animation of the script, but on the temporal refinement of the hammer swing in relation to speaking the lines.

13. ^The preparation phase of movements is indicated by dots (“…”), the duration of the demonstration by hyphens (“—”), and the retraction phase by commas (“„„”) (s. Kendon, 2004, 108–127; Mondada, 2019a).

14. ^One possible practice is to exaggerate or caricature negative versions (Keevallik, 2010), but compared with the binary logic of language, this remains rather ambiguous.

15. ^“Exemplifying” here means to deliver a typical example of a label possessing core features of it and referring to it (e.g., when a patch of green paint is used to exemplify and refer to the label “green”)—which is roughly in line with Goodman's (1968) usage of the term.

16. ^Interestingly, his descriptions of the motive for exaggerating the limp with the character's voice make it readable as a tentative representation of the character's thoughts.

17. ^“Subtext” is a technical term in theater. It refers to the subliminal meanings of a text that are not part of the script. Explicating subtext in rehearsals—e.g., saying what characters think, might say, or what drives them—can serve to deepen the understanding of a character and thus its portrayal on stage (Stanislawski, 1986; Schorlemmer, 2009). In terms of the demonstrations, subtext functions as an annotative aspect that clarifies the meaning of the demonstrations, but is not meant to be imitated.

18. ^Since actual behavior in most cases is based on a mixture of meaning-making methods, “a prototypical depiction is really a communicative signal whose depictive property is more salient than its indicative and descriptive properties” (Hsu et al., 2021a, p. 3).

19. ^“…‘embodied knowledge' (…) needs to be enacted by the lived body in order to be accessible in the interaction (be it in dance, instrument playing, singing, sports, or any other type) and in this sense defies its separation from that same body as its original habitat. In other words, it is a form of knowledge that is non-representational in the sense that it can only be partly ‘represented' at the conceptual level” (Ehmer and Brône, 2021, p. 3).

20. ^As Norrthon (2019) has shown, often a script provides a rough framework for what to play (e.g., a quarrel), whereas the “howness” (p. 183) has to be developed in the rehearsals. In developing how to play a scene, however, both the “what” (e.g., playing a “school girl”) and the “how” (e.g., talking in a very high voice) can be aspects of how to play a scene, with the former being delivered as a verbal category and the latter as a behavioral description, often accompanied by a demonstration.