94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Commun., 18 August 2022

Sec. Health Communication

Volume 7 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomm.2022.946501

This article is part of the Research TopicExistential Narratives: Increasing Psychological Wellbeing through StoryView all 12 articles

Controversial media content has mainly been dealt with in relation to concerns about how the media we consume might be detrimental to its viewers as individuals and society at large. Nevertheless, researchers have started to take a different approach to these types of content, namely that these might lead to processes of reflective appropriation, meaning-making, and moral rumination. Via qualitative in-depth interviews with young adults (N = 45, age 18–24), we sought to gain deeper insights into the experiences of and reflective thoughts (i.e., moral rumination) about controversial media content. To map when and what forms of moral rumination are incited in viewers, we chose a popular example of a morally conflicted and highly controversial type of media content, namely the Netflix series 13 Reasons Why. The results reveal that moral rumination can exist in at least two forms, morally conclusive (i.e., rumination that ends in a moral judgment) and morally inconclusive (i.e., rumination that does not formulate a moral judgment but remains morally in doubt) rumination. The grounds for the ruminations are mostly text-based or based on the interaction of text and viewer characteristics, and are mostly focused on the show's central themes, such as suicide, guilt and responsibility, sexually transgressive behaviors, and themes tied to identity formation. Overall, the tendency of morally complex entertainment to promote moral rumination suggests that such material should be examined as a type of eudaimonic entertainment, which argues that viewers reflect on how the meaning of the content relates to their own lives.

In 2017, Netflix released the first season of 13 Reasons Why, based on the similarly titled bestseller by Jay Asher. The wildly popular high school drama enumerates the events that led high school student Hannah Baker to take her own life. The show garnered unprecedented levels of social media engagement, quickly becoming the most tweeted-about show, it received both popular and critical acclaim and quickly rose to Netflix's most popular list (Min, 2017). However, the show's success was also followed by an overwhelming backlash to the show's tone and message from varied parties like high schools, parents, and medical associations. The show was seen by these parties as controversial, and their concerns are particularly focused on the potential for social contagion and copycat suicides, because (initially, the scene is now removed) the show portrays the act of suicide in such specific detail (Uhls et al., 2021). And while these concerns have received some empirical support for young-at-risk-viewers (Hong et al., 2019), research has also revealed the potential the show has for fostering empathetic behaviors by youngsters, openness about mental health needs, and reported a better understanding of difficult topics such as depression, suicide, bullying, and sexual assault (Wartella, 2020). As such it seems that the show, which focuses on topics that are societally perceived as controversial, provides viewers a platform, to engage in moral (self-)reflection, or rumination if you will, on complex themes.

Controversial media content, like 13 Reasons Why, has been at the core of the discipline of communication science since its inception. This type of content, often tied to depictions of graphic violence, sex, or a combination, has mainly been dealt with—in both societal debate and scholarly work—in relation to concerns about how the media we consume might be detrimental to its viewers as individuals as well as society at large (Eden et al., 2011, 2017; Raney et al., 2020). The debate has been rather consistent over time. On the one hand, the debate focuses on a cluster of adverse effects on the individual level, such as an increase in (potential for) aggressive behavior and a decrease in empathy and prosociality. On the other hand, it discusses concerns on the societal level, particularly the decay of public morality and social norms (Bartsch et al., 2016; Eden et al., 2017).

Quite recently, researchers have started to take a different approach to controversial media content, showing that it might lead to processes of reflective appropriation, meaning-making, and moral rumination (Bartsch et al., 2016; Eden et al., 2017). Beginning from the assumption that the consumption of (some of the) controversial media content could be based on more than mindless thrill-seeking, violent fantasies, and escapism, and might even be tied to personal wellbeing and growth (cf. Dill-Shackleford et al., 2016). Studies by for example Bartsch et al. (2016) and Scherr et al. (2017) have outlined that controversial media content might be attractive to viewers because it offers the potential for meaning-making.

Furthermore, a study by Eden et al. (2017) explored if controversial and conflicted content—specifically a controversial narrative from The Sopranos that depicted an act of unpunished and graphic rape—could lead to moral rumination in viewers. In that study, moral rumination was defined as “the capacity and process by which a person evaluates several perspectives on a moral issue, through which it becomes clear which moral value is the most important in a specific situation and what the preferred moral action is going to be” (Eden et al., 2017, p. 143). The authors tied moral rumination to the potential for moral growth and moral maturity. They found that moral rumination was predicted by transportation into the narrative world and was related to increased appreciation of the shown episode. In the literature, appreciation—rather than enjoyment—is seen as a eudaimonic gratification, and is typed as “an experiential state that is characterized by the perception of deeper meaning, the feeling of being moved, and the motivation to elaborate on thoughts and feelings inspired by the experience” (Oliver and Bartsch, 2010, p. 76).

The studies by Bartsch and Mares (2014), Bartsch et al. (2016), Eden et al. (2017), and Scherr et al. (2017) outlined that reflective thoughts—such as moral rumination—could be sparked by conflicted and controversial media content. However, it remains unclear what the ground or starting point for this reflection or rumination exactly is. In this study, we aim to provide insight into moral rumination as a concept, by exploring what the antecedents of this concept are. We opted for a qualitative approach, conducting in-depth interviews since this methodological approach offers deep insights into the experiences of and reflective thoughts about controversial media content.

To map possible antecedents of moral rumination, we chose a popular example of a morally conflicted and highly controversial type of media content, namely the Netflix series 13 Reasons Why. As previously outlined, the show has sparked worldwide concerns regarding the possible negative effects that the (graphic and unpunished) depiction of controversial content—such as suicide, rape, (cyber)bullying, and slut-shaming—might have on (young, at-risk) viewers (e.g., Jacobson, 2017; Tolentino, 2017; Arendt et al., 2019; Hong et al., 2019; Niederkrotenthaler et al., 2019; Bridge et al., 2020). While recent meta-analytical research has argued that there is no evidence to support the belief that fictional media with suicide themes lead to a suicide contagion among viewers (Ferguson, 2019), the concerns regarding the potential for suicide contagion effects remain (Stafford, 2017; Arendt et al., 2019; Scalvini, 2020). Nevertheless, critics also suggest that the show's unflinching portrayals might lead to thoughtful reflections and conversations among peers and parents about the prevalence of bullying, depression, and gendered violence in our culture (e.g., Ryan, 2017a,b; Lauricella et al., 2018). This line of reasoning has also received empirical support (for non-at-risk youths) (Lauricella et al., 2018; Arendt et al., 2019; Carter et al., 2020; Chesin et al., 2020; Cingel et al., 2021). For example, in a study by Lauricella et al. (2018), the authors found that the show resonated with teens and young adults, and they felt it was beneficial for them and people their age to watch. Additionally, the survey revealed that the show prompted conversations between parents and adolescents about complex issues and led adolescents to exhibit greater empathic and helping behavior toward others.

These results provide initial support for the idea that 13 Reasons Why might prompt moral rumination in viewers. Still, it remains unclear when it is prompted (e.g., before, during, or after viewing) and what the moral rumination is about (e.g., specific characters, topics, or storylines). The current study aims to explore and map if and how moral rumination can be sparked in viewers who watched the Netflix series 13 Reasons Why.

Research that has analyzed moral evaluations of televised narratives in studying moral rumination forms an important theoretical starting point. Moral rumination can be seen as a complex form of morally evaluating various perspectives present in the narrative to come to a moral judgment (Eden et al., 2017). Previous research focusing on moral evaluations, i.e., the process through which moral judgments are formed, builds heavily on Affective Disposition Theory (ADT, Zillmann, 2000) as well as Raney (2004) extension of this theory (EADT). ADT assumes that viewers judge every character's action according to their own moral make-up (Zillmann, 2000; Raney, 2004), and the eventual moral judgment is based on a possible fit or misfit between characters' actions and the moral standards of the viewer. EADT provides a base for arguing that this lens of moral scrutiny for characters might work differently for characters we like, and or characters who do not fit nicely into a hero/villain mold (Raney, 2004; Shafer and Raney, 2012). Previous research on moral evaluation revealed that these moral evaluations can be based on (at least) three grounds or routes: primarily driven by the text, both text and viewer characteristics, and primarily driven by viewer characteristics (van Ommen et al., 2014, 2016). We assume these grounds or routes might also be at play in moral rumination (cf. Eden et al., 2017).

When considering the role that the text (in this study 13 Reasons Why as a media narrative) might play in prompting moral rumination, previous empirical work and several theoretical concepts should be considered. First, when the moral structure of 13 Reasons Why as a media narrative is considered, the complexity of this narrative (with single episode storylines as well as season-long arcs), the lack of moral closure, and the morally ambiguous nature of the majority of the main characters should be taken into consideration. Additionally, building on the study by Eden et al. (2017), we know that the specific content of a narrative can play an important role in prompting moral rumination. They concluded that a narrative featuring graphic, unjustified, and unpunished violence with no moral resolution led to a conflicted state in viewers, prompting moral rumination. Since there are a variety of controversial situations of unjustified and unpunished violence in 13 Reasons Why (e.g., the rapes of Hannah and Jessica), the question is if these also spark moral rumination.

From research on the moral evaluation of complex narratives, we know that mediated closeness plays an important role in the moral evaluations and (subsequent) enjoyment of characters (van Ommen et al., 2014, 2016, 2017). Mediated closeness points to our transportation into the narrative world and the closeness people can feel to characters and their plight (Bilandzic, 2006). However, considering this for 13 Reasons Why, we know that with each new tape (or episode) new, morally complex information regarding controversial topics (i.e., suicide, sexual harassment, bullying, rape) will come to light. This might complicate the feelings of closeness viewers have toward characters, and in guarding these feelings, viewers might potentially enter into internal ruminations about the closeness they (want to continue to) feel toward favored characters.

Building on attribution theory, Tamborini et al. (2018) argued that viewers might continue to like imperfect characters who commit distasteful acts, through the active mental attribution of the reprehensive behavior to external causes portrayed in the media content. For example, in season 1, the protagonist Hannah is a victim of bullying, shaming, and rape, but also a bystander of rape and reckless behavior (which indirectly causes another character, Jeff, to die). These complex storylines might complicate feelings of closeness viewers feel, which could lead to a process of attribution to external causes through the process of moral rumination.

Second, aside from moral rumination potentially arising from (conflicting) cues in the narrative, it might also be the case that moral rumination occurs because of the interplay of narrative and viewer characteristics. This interplay, made up of the experiences and characteristics of the viewer and the power of the narrative to transport viewers in the narrative, will culminate in a specific reading of the narrative (Fiske, 1987; Michelle, 2007; van Ommen et al., 2016). When focusing on the interaction between the text and the viewer, schemas that viewers have from previous media experiences might also play a role in their responses to the show and the possible presence of moral rumination. When someone watches a television show, such as 13 Reasons Why, various schemas are used to (immediately) assess whether a character is good or bad (Fiske and Taylor, 1991). A schema can be described as an efficient map of prior information about characters, events, or situations in clusters of related facts (Keen et al., 2012). As such, schemas consist of a predictable pattern that viewers can use when encountering media characters. However, if the chosen schema does not fit and reclassification (i.e., inconsistency resolution, Sanders, 2010) is in order, this process might spark moral rumination in viewers. For example, the character of Justin is initially introduced as a stereotypical “bad boy” and a teenage heartthrob, priming viewers with schemas they have about these types of characters (Gopaldas and Molander, 2020). However, this is later complicated by Justin's family backstory of neglect and drug abuse, as well as his unwavering love for Jessica. This shift in the characterization of Justin could lead viewers to a process of recategorization of the character, which (if complex) might spark moral rumination.

Another way in which the narrative and viewer characteristics might interact and potentially lead to moral rumination is via “indirect” experiential closeness (van Ommen et al., 2014). This form of closeness describes the state where viewers mentally put themselves in a protagonist's position and explore internal questions, such as: What would I do if I were in the protagonist's shoes, or what if I were confronted with this type of problem or dilemma? This mental process of going back and forth between what a character has done (in relation to the characters) and how a viewer feels about these actions and taking on various perspectives, as presented in 13 Reasons Why might lead to moral rumination.

Additionally, moral rumination might also be sparked by the temporary expansion of the self-concept (i.e., TEBOTS, Slater et al., 2014) through engagement with 13 Reasons Why as a narrative. TEBOTS argues that the desire for release from the confines of the self leads viewers to the vicarious experience of characters and fictional lives that are (in)comparable to our own. As such, people expand their sense of self through (briefly) living vicariously through characters and transcending their limitations by temporarily being a different self (Slater et al., 2014; Johnson et al., 2015). However, due to the morally complex buildup of the episodes and the narrative arcs in 13 Reasons Why—and the possibility of binge viewing and immersion into the story world—this might complicate identification and character loyalties and various ways in which the viewer can expand the boundaries of the self. Thus, potentially also forming ground for moral rumination.

Finally, moral evaluations, and thereby possibly also moral rumination, might be created through a reading of the narrative in which viewer characteristics are the most dominant. As Hall's (1993) model of encoding and decoding describes, viewers are not passive recipients of a narrative. Instead, viewers give meaning to mediated narratives based on personal history and frameworks of knowledge and meaning, which then leads to the possibility of a large array of interpretations of the same narrative (Livingstone, 1990; Chisholm, 1991). Furthermore, viewers may have a specific moral make-up that relates to (or conflicts with) the experiences, behavior, and moral framework of the characters featured in 13 Reasons Why. The moral rumination can then be guided by the moral makeup and viewers' past experiences with the topic and themes discussed in 13 Reasons Why.

More specifically, research has outlined that when making moral evaluations, a connection between the content of the narrative and personal experiences and expertise can through perceived realism lead to more enjoyment of the narrative and guide the outcome of the moral evaluation toward specific judgments (Bilandzic, 2006; van Ommen et al., 2016, 2017). In the case of such experiential closeness, the media content activates relevant structures the viewer has and cues moral evaluations based on a comparison of one's own beliefs and norms and the belief structure in the text. Previous research has outlined that a mismatch between portrayed events in the narrative and viewers' personal experiences and values resulted in a distance toward the narrative coupled with counter-argumentation in the moral evaluation (Bilandzic, 2006; van Ommen et al., 2016). This extensive counter-argumentation in moral evaluation could be a form of moral rumination. This has been previously conceptualized as a complex form of moral evaluation in which the viewer considers multiple perspectives (Eden et al., 2017). Therefore, we believe that viewers with explicit experience with particular narrative themes in 13 Reasons Why (i.e., high school experience, identity formation, bullying) and vivid memories of this (high school) period, in general, might be more prone to morally ruminate about the issues presented in the narrative.

Taken together, this study will explore young adults (18 years and older) viewing experiences and potential moral rumination as a result of 13 Reasons Why. Young adults will likely have a vivid recall of the high school experience, but also have a greater potential for (self)reflection of the period since they are no longer in high school (King and Kitchener, 1994). Our research aims to increase the understanding of moral rumination sparked by conflicted media content that depicts controversial topics. Building on previous work that has mapped the grounds of moral evaluation, for complex media content, we, therefore, believe that cues in the text, the interaction between viewer and text, and viewer characteristics might function as antecedents (or grounds) in prompting moral rumination (van Ommen et al., 2014, 2016, 2017). Furthermore, we extend the work of Bartsch et al. (2016) and Eden et al. (2017), in our ambition to present knowledge that moral rumination can be sparked by controversial content (in this study: the widely debated 13 Reasons Why). Therefore, this study aims to answer the following question:

RQ1: How do young adult viewers come to morally ruminate about the content of 13 Reasons Why, and what are the grounds for this moral rumination?

To explore the possible antecedents of and variations in moral rumination, as well as map which specific content leads to moral rumination, we conducted qualitative in-depth interviews with a sample of 45 participants. Qualitative research was used in this study because it was concerned with exploring how moral rumination was sparked by the interaction of viewers with 13 Reasons Why (specifically the first season, which was broadcast a few months before the interviews) as a morally complex narrative. Qualitative research aims to produce a well-rounded and contextual insight into and understanding of how certain aspects of the social world are experienced, interpreted, or produced based on rich, descriptive, and in-depth data (Braun and Clarke, 2013).

Following the principles of theoretical sampling (Patton, 2002), participants were selected based on criteria derived from theoretical research and ethical considerations. As outlined before, young adults were sampled based on the idea that they might reflect on the representation of teenage life in 13 Reasons Why because it might correspond with events that they had encountered as teenagers in high school (i.e., direct experiential closeness; Bilandzic, 2006; van Ommen et al., 2016). Furthermore, due to the controversial content, all participants were recruited with the explicit condition that they had seen all episodes (of the first season) of the show to ensure that they were aware of the explicit depictions of controversial content such as rape and suicide. This procedure was approved by the ethics committee of the host university at (university blinded; code blinded). The interviews were conducted between October 2017 and December 2017 in The Netherlands. Participants were recruited through personal contact with the researchers and their students, although the interviewer in each separate interview did not intimately know the interviewee. The group of forty-five participants consisted of 14 males and 31 females, and their ages ranged between 18 and 24 years old.

The interviews lasted about 80 min (range: 56–105 min) and took place in respondents' familiar surroundings (i.e., in their home, in a quiet place at their university). Participants were first informed about the procedure, including recording, transcription, anonymity, and confidentiality, and subsequently asked to fill out the informed consent form. After the interview, they were given a debriefing about the aim of the study and why they were selected, as well as information for post-interview psychological care if needed. The post-interview psychological care was arranged with Korrelatie (2015), a Dutch non-profit foundation that specializes in anonymous psychological help.

This study used a semi-structured interview guide consisting of three open-ended initial questions paired with potential probing and follow-up questions. The interview guide and the order of the questions were not rigidly enforced to facilitate the natural flow of conversation and not limit the interviewees' flow and elaboration. With each initial question, probing questions were used to get participants to elaborate on their questions and choices.

The interview started with a question that asked the participants what their most prominent memory was from watching 13 Reasons Why. Next, our initial question asked participants which of the characters they felt was the most responsible or to blame for Hannah Baker's suicide. They were told to use small photo cards that showed headshots of all the main characters to rank the characters' blameworthiness. They were asked to elaborate on their answer, for example by asking them to make lists from least to most blameworthy, and were probed to elaborate on the moral intricacies of their answers. Thirdly, based on their previous answers, participants were shown clips from the episodes, which showed that different characters held different/conflicting moral outlooks on events that happened throughout the show. Participants were asked to respond to the clips and whether these scenes changed their perspective on that character or that event. We used the clips to either elicit further elaboration on previous answers (also as a validity check) or to probe the participant for possible nuances or moments of reflection by showing them video clips that would “challenge” earlier held views on characters or situations. As such, the selection of scenes was tailored to each participant's answer pattern and was used to further elaborate or deepen our understanding of their position. This was done by, for example, choosing to watch and discuss a scene that represented an opposed position taken by the respondent or showing the perspective of other characters on a specific conflict in the series. Finally, the participants were asked about their demographic characteristics and viewing behavior connected to 13 Reasons Why.

A selection of fifty-three video clips from the first season of show1, a photo-overview sheet that captured all the main characters of the show, as well as cards with an individual headshot of all the main characters, and if the occasion arose, the episodes themselves were used as visual stimuli in the interviews to help the interviewees recall the characters and storylines, help order their attribution of guilt in Hannah's suicide and to generally get the interview started (Collier, 1967; Pauwels, 1996; van Ommen et al., 2016).

In this study, several techniques were used to secure the (internal) validity and reliability of the study. To test the interview guide, the primary researchers conducted the first fifteen interviews, and students conducted the other thirty interviews in the study. The students were trained as part of a research seminar in qualitative interviewing on moral rumination. The research seminar explored the literature on moral rumination and television drama. The interviewers received several interview training sessions, in which they familiarized themselves with the moral predicaments in the series 13 Reasons Why, the interview guide, and practiced conducting in-depth interviews on potentially sensitive topics (such as depression, suicide, and slut shaming).

In this context, the internal validity and the study's reliability were secured by constant discussion among the interviewers, enabling peer debriefing (Braun and Clarke, 2013) and the consistent creation of memos to list externalized thought processes throughout the process of analysis. The setup of this study also enabled researcher triangulation, which meant that the use of several interviewers canceled out individual biases, and several researchers' involvement in the data analysis compensated for potential single-researcher biases (Denzin, 1989). The internal validity was also secured by member checking, which entailed that the interviewers reported back to the participants during and after the interviews so that they could comment on the researcher's descriptions and summaries of the responses (Patton, 2002).

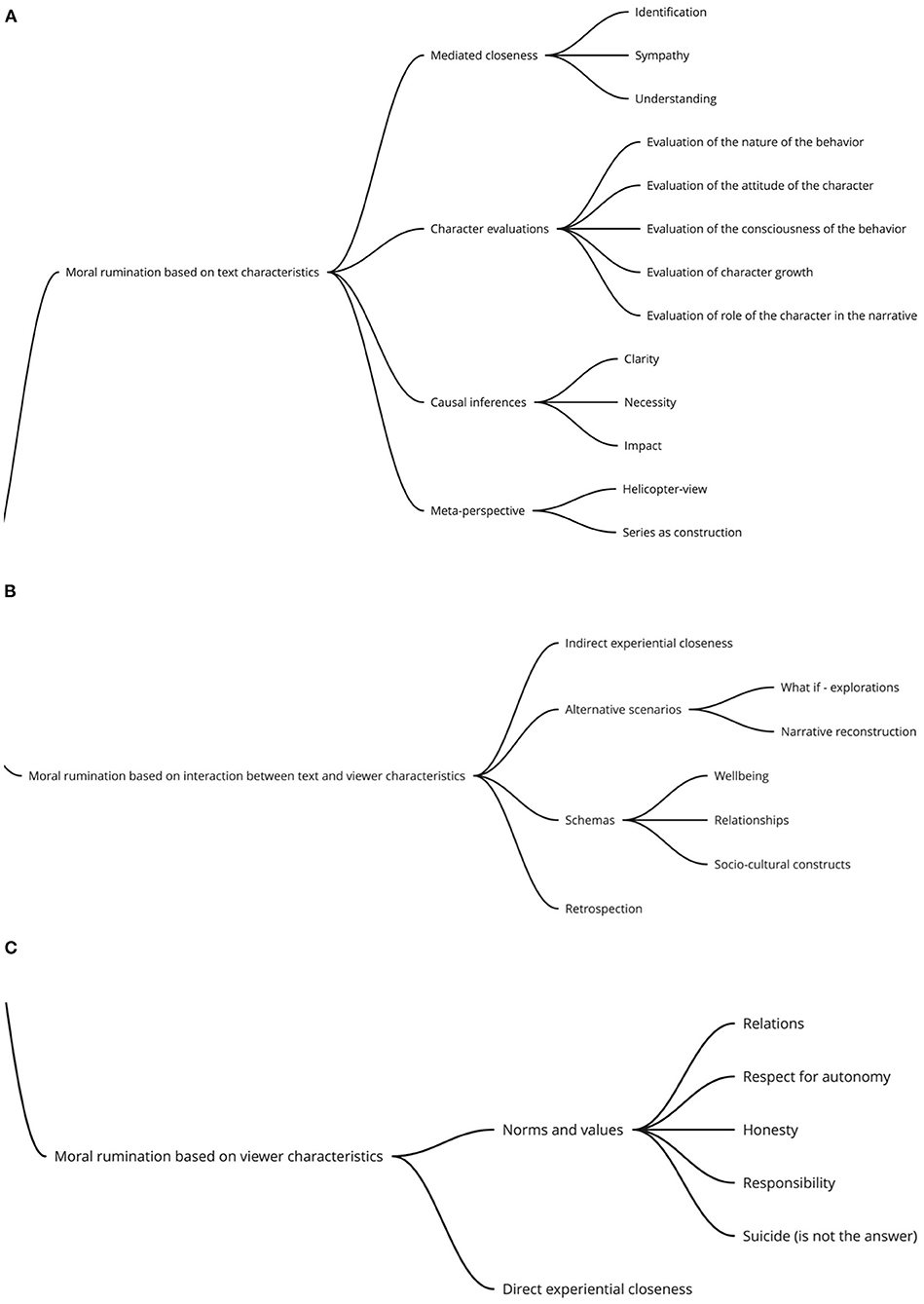

In-depth interviews were held in Dutch, audio-taped and transcribed verbatim, and subsequently analyzed using the qualitative data analysis program MaxQDA2. The analysis was grounded in three distinct phases of grounded theory research (Strauss and Corbin, 1998; Boeije, 2002; Patton, 2002). In the exploration phase, the researchers formulated as many codes that could be relevant given the research questions focused on (1) grounds for moral rumination and (2) topics of moral rumination. In the subsequent specification phase, axial coding was used to specify further the concepts and categories concerning the central questions and related (theoretical) topics. In the reduction phase, selective coding was used to establish the relationships between the core theme of moral rumination and the developed categories and codes. Finally, this phase resulted in an ordering of the core theme, categories, and codes in a way that would describe the aspects relevant to the research questions (Patton, 2002). This phase resulted in one model (which for compactness is split up in Figures 2A–C), which integrates the variation in antecdents for moral rumination and the topics the viewer ruminated about.

Based on the analysis of the interviews, the first empirical distinction that was found was a variation in the nature of moral rumination, between (1) conclusive moral rumination and (2) inconclusive moral rumination. The distinction between the two categories was constructed in the analysis when it became clear that participants who engaged in moral rumination had two “endpoints.” One in which at the end of their ruminations, of comparing the weight of several moral arguments, taking the perspectives of several characters, or using narrative cues to nuance their position, they came to a final moral judgment or conclusion (i.e., conclusive moral rumination). The other option, was when participants remained stuck in this process of rumination, and even though they tried continuously, they were unable to decide on a definitive moral judgment (i.e., inconclusive moral rumination). They simply did not know their definitive moral outlook, and continued to go back and forth and nuance their moral evaluations. In other words, inconclusive moral rumination was constructed as a category in analyses when it became clear that the viewer experienced doubt, and ruminated but was continuously unable to formulate a final moral judgment or their conclusion is still filled with duality or doubt.

As seen in Figure 1, these two types of moral rumination in 13 Reasons Why were prompted by text characteristics, by the interaction between the text and viewer, and purely based on viewer characteristics. Additionally, it is important to stress that overall, the participants only ruminated about complex (i.e., offering multiple perspectives, showcasing changes over time) and morally ambiguous storylines (i.e., unclear who is to blame, who is immoral). Finally, respondents felt that the storylines in 13RW were realistic, valid, and truthful representations of reality, and this seemed to be a prerequisite for rumination. Sparingly, there were some scenes or character behaviors where they felt that it was unrealistic (i.e., arguments like it does not happen that way, no way that would happen in real life, and they just put this in there for the drama) and this hindered them in ruminating on the topics at hand.

The results showcase that the greatest variety in antecedents for moral rumination is based on text characteristics (Figure 2A), specifically, it can be prompted by mediated closeness, character evaluations, causal inferences, and taking on a meta-perspective. These grounds and their variations will be discussed consecutively.

Figure 2. Moral rumination prompted by text characteristics (A), the interaction between text and viewer characteristics (B), and viewer characteristics (C).

Mediated closeness, the degree to which viewers do or do not feel a degree of closeness to various characters, often forms a starting point for ruminations about the content. The most profound form of mediated closeness that participants described resulted from identification with various characters and their fates. Conversely, a complete lack of identification and, therefore, closeness—as seen in the example below, can result in a profound sense of distance toward a character.

R: No, no, no. I really don't know. I don't think I would have made the tapes… but well…I think that if you feel that way, I don't know if you really have specific reasons that everyone, that thirteen people have hurt you so much. Well I don't know, I have difficulty imagining myself doing that, I really do not know why you would do that and, well kill yourself . (Interview 26, female, 19 years, inconclusive moral rumination)

On this constructed continuum of mediated closeness, identification is followed in intensity by a viewer (not) feeling sympathy for various characters. This sympathy participants feel for characters results in empathetic concern for characters and a resounding disavowal of certain characters' behaviors when viewers try but ultimately fail to sympathize with characters. Finally, the last variation of mediated closeness (or distance) can result from a level of (non) understanding of the behaviors of various characters. As the participant below shows, she struggles with understanding the viewpoints of various characters (specifically Zach and Hannah) in the series.

R: And with the fact that he mentions the list3 again, I understand why she reacts that way. But she is immediately defensive, when he says that one thing about “I wanted you to be my Valentine.” She is unable to see that he is for real I think, but on the other hand … well I can understand why, but on the other hand well I don't believe everyone is that way.

I: And his conclusion, is that part of what happens to her [Hannah] is due to her own behavior. Is that a valid point?

R: Ehm, well that that is difficult to say but I think I understand maybe in this instance, he gets really angry with her but well she is also not really nice. But in any other circumstance I really don't agree with him, so yeah maybe half true? I really find it hard to say really. (Interview 7, female, 19 years, inconclusive moral rumination)

If there is a fundamental cognitive lack of understanding of why characters behave in a certain manner, this rumination will also result in a profoundly felt disconnect or distance toward the characters.

Viewers also came to morally ruminate about characters and how they evaluated them and their behavior in a variety of ways. Viewers weighed the nature of the behavior by considering the characters' motives and their intent. For example, a respondent differentiated between Justin and Marcus via the intentionality of their behavior. “Well maybe… partially so. I think the main difference is that Justin did not have ulterior motives, and in the case of Marcus his intent was to get in, it was really bad” (Interview 5, male, 20 years, conclusive moral rumination).

The participants also evaluated the attitude a character held (and possible changes therein throughout the series), based on valued character traits and behavior related to topics like loyalty, authenticity, miscommunication, and the degree to which they were active participants or instigators of morally reprehensible behavior. For example, one respondent ruminates about how she feels about the last interaction between the counselor and Hannah, and how his intent and start to that interaction were good and Hannah's expectations might have been skewed, but in the end, she feels the counselor failed Hannah.

R: and ehm … it is unrealistic what she expects there, but I do get her because something truly awful happened to her. And his initial response is good, I have to say, telling her he will do everything to make her safe. But then he also stresses the fact that she needs to press charges, and he does not ask her how she feels about that or what can I do for you. It is very much you HAVE to press charges, and that is the only possibility. (Interview 10, female, 19 years, conclusive moral rumination)

Participants also ruminated on the consciousness of behavior characters enacted. Herein, participants use the narrative as a basis to assess and judge if they believed that a character was fully present, willing and able, and an active participant in the acts that they felt were morally reprehensible or that the character was only circumstantially involved and therefore not as blameworthy or responsible. They pondered the degree to which they felt a character showed growth throughout the show. This growth was often assessed through the weight viewers attributed to the degree to which they saw a character feel and take responsibility for their actions, the acknowledgment of guilt, and the perceived (and justified) suffering a character endured.

R: Well yes, you get a clearer vision of him [Alex]. He truly has remorse for his actions, and that is maybe also why later in the end he tries to commit suicide. That he just cannot deal with it anymore, in this scene you truly get to know him, he is truly sorry and he didn't mean to do it.

I: Does that make him less guilty?

R: No, he made the list so he is responsible […] I understand what he did on the one hand, but also … if you love someone then you shouldn't do that, just because she will not sleep with you. (Interview 42, male, 19 years, conclusive moral rumination)

Finally, they evaluated the role of the character in the show, and they zoomed in on the function characters had in relation to the protagonist (who are they to Hannah), their prominence over the narrative (i.e., are they important enough to have their own tape or episode) as well as their function as characters who create plot points that drive the story within the narrative. Viewers, for example, consider the relationships characters have toward one another (e.g., Marcus' reprehensible behavior is less crucial than Alex's since he was not Hannah's friend) and the role they fulfill in the narrative (e.g., feelings about Alex as the catalyst for truth-telling surrounding Jessica's rape).

A third way viewers come to morally ruminate about the show, based on text characteristics, is through causal inferences. When participants engaged in causal inferences, they take all the factors that played a role in a situation into consideration and try to analyze if there is truly a clear cause-and-effect relation present for a specific problem or a certain situation. Viewers ruminate about the perceived clarity of a problem for all involved, for example, a respondent pondered if Clay could have done more for Hannah, but also feels that Hannah did not communicate her needs well enough. They ponder thereby ponder if Clay's behavior was actually to blame (i.e., a cause), for Hannah's suicide.

R: Yes, she had the feeling that she was not in it alone. That someone would help slay her demons. Because these thoughts are real, I think she may be needed a little push to share that with someone. But […] Well maybe he could have done more … He should have done more, but on the other hand he really couldn't have done more. He tried talking to her. He engaged with her, but if she really wanted someone to be there for her, she should have said so and not cursed him out and told him to leave. So yeah, I do believe he could have made the difference, but I also believe that the reason he didn't stay is due to her own behavior. (Interview 31, female, 21 years, inconclusive moral rumination)

Viewers also ruminate about the perceived necessity or logic of certain behaviors, for example, viewers discuss their understanding but also confusion about the lengths to which Courtney goes to keep her lesbian sexuality hidden and protect her gay fathers. Lastly, viewers also discuss the negative impact certain behaviors have on (innocent) others as grounds for rumination. With the previous example of Courtney in mind, viewers feel conflicted since they have some understanding of why she would want to protect her identity, but also think that she causes undue harm to Hannah, who is an innocent bystander in this.

The final way text characteristics are the grounds for moral rumination, is when viewers take on a meta-perspective in their evaluation of the characters, their behavior, and the show as a whole. On the one hand, this meta-perspective manifests itself in viewers, using information from the series' narratives and taking on a helicopter perspective through this. This perspective leads viewers to, for example, ponder the behaviors of characters side-by-side, or compare the weight of the “reasons” for Hannah's suicide side by side, thereby combining information from several episodes.

R: Well, I think he [Zach] just goes in the flow of the other boys, because they all actually do worse stuff. But I, well … I don't think he can be blamed, same as with Clay, that if only this one thing happened and not all the other things it would not have had an impact. This may be true for a lot of things though, but comparatively, Zach is actually really inconsequential. (Interview 1, female, 19 years, conclusive moral rumination)

The other way this meta-perspective manifests itself is when viewers ponder the series as a construction. One respondent, for example, considers the use of the tapes as a mechanism in the show and how it creates a certain perspective for viewers and characters.

R: Yes, well that is what I constantly wonder about because there are all these reasons why she committed suicide, so I do not think he was the one factor who could have saved her, but on the other hand it is so hard to look inside someone's head even though the tapes do provide us some input on what she thought and felt in many cases. (Interview 17, female, 20 years, inconclusive moral rumination)

Viewers can also come to ruminate because characteristics of the text intersect with their own characteristics, via indirect experiential closeness, pondering of alternative scenarios, the use of schemas, and retrospective assessment of the series (see Figure 2B).

In the case of indirect experiential closeness, viewers showcase a willingness to place themselves in a character, or characters' shoes, and ponder how they would have behaved or what they would have done in a specific instance.

R: Yes … I would not worry about that, I feel like fine that is how I am and get over it. But maybe when you are a teenager and your boyfriend puts you at the bottom of a list, then I would probably also get really angry … well in that situation at that age …

I: You would be mad at her?

R: Yes, … I think so. Because you might see her as competition in a certain way. And then wonder, why does he pick her, maybe something happened between them. And then she might overthink it, in the sense who knows what else Alex thinks about her. So yes, I would get angry. Then, as a teen, … now I would not care. […] The anger is not justified … but I do understand … (Interview 10, female, 19 years, conclusive moral rumination)

Viewers also engage in moral rumination when they actively engage with the narrative and ponder, what if explorations and also engage in forms of narrative reconstruction. In their ruminations, viewers often contemplate how storylines would have turned out differently if some events did not happen or if characters would have behaved differently.

R: Yes, well even though it sounds logical that he says to Hannah that it might have worked out differently, so then well it is logical that he feels this way. And that makes it so sad because it probably would have worked out for the best for both of them, it could have helped her … but on the other hand, we also understand that if she yells at him that he then leaves. I think most people would have left if someone acts that way. (Interview 9, female, 19 years, conclusive moral rumination)

Additionally, but very closely related to what-if scenarios, through a form of narrative reconstruction, participants also explore what they believe should have happened in some events and how this would have then unfolded. They then also reflect on why this scenario probably did not develop the way they believed it should have.

R: No that is probably true, but I also believe that when she is hiding in the closet and sees what Bryce is doing and she knows it's rape, and even though she might want to do something, she should do something, what can she do? To truly stop it she should have come out of the closet and said something or ripped the boy off her or whatever … But still Bryce is a big guy I think, and she might also think that she would not succeed […] So I also think she was really frightened, about what could also happen to her. […] it is the moment that she is stuck in the closet, she has two options, either go out and say something with the possibility that something might happen or stay put in the closet. And what truly the best choice is I find hard to say … (Interview 5, male, 20 years, inconclusive moral rumination)

Viewers also engaged in moral rumination via the use of schemas. Schemas are efficient mental clusters of prior knowledge participants hold based on experiences and information the participants have gathered in real life or through media experiences. The schemas that led to rumination in the current study clustered around general ideas about wellbeing (e.g., mental health, emotions), general ideas about how one behaves in certain relationships (e.g., how one should behave as a parent, as a romantic partner, as a friend) as well as scripts that dealt with a variety of socio-cultural constructs (e.g., gender schema's, puberty, coming-out). Viewers use these schemas (clusters of knowledge surrounding specific topics) to make sense of storylines or assess a certain character's behavior, which sometimes leads to inner conflict.

R: Well, I get that he might think that she was under the influence, which you should never assume. Because if you don't know, or did not feel it, or whatever, it did not happen. And generally speaking, you know that people who are raped are scarred for life by this trauma. So I get that he means well, but I also get Jessica being really mad because it is her body and … On the one hand, I think why should you bring someone who doesn't remember all this mental stress by telling her, and on the other hand, you have a right to know because it is your body.… (Interview 36, female, 19 years, conclusive moral rumination)

Finally, moral rumination via the intersection of text and viewer characteristics also came to the fore in a retrospective view that some participants applied. This was most prevalent for participants who had seen the show a while ago and had now re-entered this narrative world again. This made them reevaluate specific ideas they believed they had and reassess their stance.

R: Well if you have seen it a while ago, I think you start to distort things in your head a little. Because you sort of forget little things and think Clay did not have a tape. He was perfect. But actually, in rewatching it this sort of clashes with the little things that you are confronted with, and then realize oh but wait there was stuff going on. You sort of need to reassess what you thought you thought, and you realize that you may have painted a prettier picture in your head, of Clay being nice and kind and perfect, while maybe he wasn't all the time? (Interview 14, female, 20 years, conclusive moral rumination)

Less prominent in this sample than rumination prompted by text characteristics or the interaction between text and viewer characteristics is moral rumination prompted by viewer characteristics (Figure 2C). If rumination arose via this path, it was either via norms and values that were prominent for the viewer or via direct experiential closeness.

In their ruminations about characters and storylines, viewers also relied on their own moral framework in which explicated rules in the form of norms and ideals they hold regarding life in the form of values play a role. The norms and values were used as a reference point or touchstone, which they used as a tool to assess how they felt about specific behaviors. These often centered around ideals and expectations they had surrounding relations (e.g., romantic, friendship, parental and professional), the values of honesty, autonomy, and responsibility. Additionally and unsurprisingly, the idea that suicide is not the solution to someone's problems is also present in the rumination by viewers.

R: Honesty. Trust I think. Well, I don't know, I think that is really important that you, even though it sucks at the moment but still it is better when you are honest about what happened, and the blow is though at that moment but if you don't say anything the blow will be that much harder later on.

I: Do you understand why he said nothing?

R: Yes, in some way I do understand because it is easier said than done being truthful. But also that he wants to protect her, I get that too. But the truth will always get out … so …. I don't know … (Interview 32, female, 19 years, inconclusive moral rumination)

The participants also sometimes ruminated about the content based on their personal experiences and knowledge about topics that were prominent in the show, such as struggles with mental health, sexuality, bullying, and sexually transgressive behavior. One respondent even alluded to the fact that because of similar experiences, the show helped him find emotional closure due to watching it.

R: Uhm … well it obviously differs per person, how much you are able to take. But on the other hand, she (Hannah) really had a lot of shit happen to her throughout the series. And in the end she had no one left … well suicide is difficult in any case … but she had issues.

I: Yes, is that a difficult subject?

R: Yes, it is difficult for me. Because, I was in a similar situation, so I identified with the situation … I understood that if this would have happened to me in high school, I get why this is her conclusion […] as a result I didn't find it hard to watch, it helped me […] it gave me the idea this could have been me … this is difficult to explain, but maybe sort of closure? (Interview 27, male, 20 years, conclusive moral rumination)

These experiences and knowledge led to recognition and an experiential form of closeness with characters and storylines. At the same time, sometimes, it also led to a more critical evaluation of the character, when the representation did not match their realities.

The current study aimed to extend the knowledge around moral rumination as a concept and to explore a more positive, growth-oriented perspective on the meaning-making of morally conflicted television content. As such, our study focused on answering how young adult viewers come to morally ruminate about the content of 13 Reasons Why, and what the grounds for their moral rumination are.

Based on an analysis of forty-five interviews with young adults, we can conclude that these viewers engaged with the series 13 Reasons Why function as moral monitors (Zillmann, 2000), and the series prompted moral rumination in viewers. Interestingly, and similar to the study by Bartsch et al. (2016, p. 758), the presence of rumination by participants was contingent first and foremost upon them regarding the show, storylines, and characters as a serious and valid representation of social reality. When the content was seen as over-the-top, unrelatable, or not real, then moral evaluations would be simple, and rumination would not arise.

Based on the current work, we formulated two new dimensions for the concept of moral rumination (as formulated by Eden et al., 2017), namely that morally conclusive and morally inconclusive rumination, which adds to the body of knowledge about this concept and provides a more refined way of conceptualizing moral rumination. Within each form of rumination there were a wide variety of rationale that prompted ruminative reflection. Still, both forms of rumination were distinguishable from one another. In the former, the participant eventually formulated a moral conclusion or judgment to finalize their ruminations; in the latter case, participants were unable to reach such a conclusion or final state of judgment. Inconclusive moral ruminators remained stuck in a state of moral uncertainty, unable to convince themselves that one argument or sense of closeness was more morally sound or convincing than another. When considering these results from the theoretical perspective of moral growth or moral maturity sparked by interaction and simulation within narratives (Winston, 1999; Carroll, 2000; Mar and Oatley, 2008), one is left to wonder which of the two types of moral rumination is more beneficial for the viewer? Is it the struggle part of morally conclusive moral rumination culminating in a final judgment, or the prolonged state of uncertainty coupled with inconclusive moral rumination? Future work should focus on establishing the effects of these different types of moral rumination on the wellbeing and moral growth outcomes of viewers.

We can conclude that moral rumination—in both forms—mainly was prompted by text characteristics and the interaction of text and viewer characteristics and to a lesser extent by purely viewer characteristics. Text characteristics, in a variety of four forms (i.e., mediated closeness, character evaluation, causal inference, and a meta-perspective), all formed grounds from which participants engaged in moral rumination. In the case of mediated closeness, as an antecedent, it consisted of variations in a continuum of empathy to cognition prompting closeness ranging from identification with characters and situations to sympathy for characters and an understanding of characters and situations. All these variations existed in both the positive form, i.e., identification, sympathy, and understanding resulting in closeness felt with character, but also conversely a lack of identification, and failing to sympathize with or understand characters. While the positive forms of closeness often resulted in ruminations ending in consensus with characters, or storylines, in the case of mediated distance rumination often ended with a fiercely critical disavowal of characters or situations. These ruminations also were consistently prompted by the storylines that were ambivalent or lacked moral closure. In the case of storylines where there was no moral ambivalence, for example, Bryce's rape of Hannah, participants only formulated straightforward moral condemnation.

Interestingly, our results tied to causal inferences as a text characteristic based on the clarity of issues the characters faced, the necessity of actions taken, and the weighing of the impact of behavior as well as a certain element of character evaluations (i.e., nature, attitude, and consciousness), are in line with the results by Tamborini et al. (2018) relating to attribution theory. The degree to which external factors (i.e., stimulus or circumstances) in the storylines of 13RW caused characters to behave immorally created a greater sense of leniency in the process of moral rumination and formulating a moral judgment than when the characters themselves were seen as the cause.

Furthermore, almost all the characters, who are central to a tape in the series, showcase that they are morally complex through, for example, the explication of circumstances for their behavior in a tape (i.e., Courtney, who wants to protect her dads, Justin, who has a terrible home situation and has been dependent on Bryce). Further, they also demonstrate character growth (i.e., both Alex and Justin owned up to their terrible behavior and wanted to make amends). If seen from this vantage point, the rumination prompted by the evaluation of the role of the character and the evaluation of the growth of the character is in line with earlier work by Kleemans et al. (2017) and Daalmans et al. (2018) on audience responses to character development in morally complex characters. These studies already proposed that the evaluation of characters—as they grow throughout a film narrative—is crucial in how we respond to characters. In the present study, we add to the body of knowledge that character growth and their role in a series provide a basis for viewer rumination and their subsequent moral judgments. The difference between the films in the mentioned studies by Kleemans et al. (2017) and Daalmans et al. (2018) and the current research is the lack of moral closure in the series (compared to film), an ensemble of main characters (instead of a leading protagonist in the films) and the time spent with the characters (13 h compared to an average of two for a film). We speculate that specific characteristics, by themselves and in combination with one another might heighten viewer rumination to a greater degree.

The final text-driven ground that prompted participants to engage in moral rumination was by taking on a meta-perspective toward the series and particular storylines. Participants used information from the entirety of the series to create judgments, contextualize, understand and ruminate about a character's behavior unfolding in earlier episodes. They also came to ruminate about the series' content when they regarded the show as a creation, a product with certain production characteristics. This mode in which they regarded the series as a construction is similar to the critical decoding in syntactical form, as evidenced in the classical study on the TV show Dallas by Katz and Liebes (1990).

Our results also pointed to the interaction between text and viewer characteristics as grounds for moral rumination. For this interaction, we also found four ways in which this interaction led to moral rumination (i.e., indirect experiential closeness, alternative scenarios, schemas, and retrospection). Similar to studies exploring moral evaluation of television narratives (van Ommen et al., 2014, 2016, 2017), indirect experiential closeness led to moral rumination in viewers because the mental process of putting themselves in a character's shoes led the to debate the “right” choice in that situation among the various options at hand. And while the studies by van Ommen et al. primarily focused on narratives about professionals (in the workplace), the current study empirically validates the presence of indirect experiential closeness for young adults with themes relating to the private sphere.

Furthermore, in the creation of alternative scenarios and ruminating about what the best and most appealing storylines would be for (liked and disliked) characters and why those eventually would not work, participants showcased the variety of meaning-making processes outlined in Hall's central model of encoding and decoding (Hall, 1993) and empirically reveal the “active audience” in processes of meaning-making. Participants then actually engage in forms of “play” (Katz et al., 1992), in which they engage in contrasting what might be, what could be, and what should be scenarios with what happened and why.

The schemas that participants used in their rumination were generally schemas about the “real-world” rather than story schemas. For example, schemas surrounding scripts of gender, sexuality, and how to act in a variety of relationships. So these were less focused on, for example, schemas that were connected with the story world (i.e., archetypes, genre criteria). For example, we believed that schemas tied to character types such as the “bad boy,” might play a role in the moral evaluation and rumination about the show, but this was not the case. It might be the case that instead of using archetypes as schemas, each morally ambiguous character throughout the series became a prototype of themselves (Sanders, 2010).

The final way moral rumination was grounded in the intersection of text and viewer characteristics was through a sort of retrospective mode of evaluation. This was primarily prompted for viewers whose initial viewing of the show was a while ago when the interview took place. They then sometimes engaged in a retrospective evaluation of what they remembered and contrasted that with what they “re-learned” through clips in the interview itself. Rumination then unfolded because what they remembered did not match the facts that were present in the clips they viewed in the interview.

Viewer characteristics were the final and least prominent ground on which moral rumination could be grounded. This could take on the form of the prominence of personal norms and values as well as direct experiential closeness. Compared with earlier studies on moral evaluation, the participants focused less on viewer characteristics as grounds for morally ruminating about the characters, storylines, or the show in general. This distinction might be because the real-life (professional) experiences in previous studies more closely matched the fictional (professional) lives on screen (van Ommen et al., 2014, 2016, 2017), while for this sample, we found that there were relatively few participants who had direct experiences with the topics of the show such as depression, sexual harassment, bullying, and suicide. Interestingly, when the rumination was prompted by similar experiences of participants in real life, the direct experiential closeness led both to ruminate about overlap in personal experiences and the representation in the show as well as a counter-argumentation due to a mismatch between personal experiences and the representation in the show. In some exceptional cases, the rumination even led to forms of reflection and feelings of emotional closure on traumatic life events the participants had encountered. This leads us to believe that this form of conflicted and popular media content dealing with controversial themes can serve as a (potential) tool to promote inner reflections, moral growth, and psychological wellbeing. The current study thereby adds to a wealth of previous research on eudaimonic entertainment which has consistently found that viewers reflected not only on the deeper meaning of the content but also on the meaning of autobiographical events, including negative experiences (Oliver and Hartmann, 2010; Knobloch-Westerwick et al., 2013; Bartsch and Mares, 2014; Bartsch et al., 2014).

Finally, we can conclude that regardless of the antecedents the moral rumination was anchored in, all moral ruminations were tied to the main premise of the show, and dealt with either the portrayal of mental health issues (i.e., suicide, depression, victimhood, and bullying), the attributions of feelings of guilt and responsibility, and discussions of (healthy and consensual vs. non-consensual) sexual relations and identity. Furthermore, as mentioned before, both conclusive and inconclusive moral rumination were grounded in the greatest variety in textual characteristics, followed by the interaction between text and viewers, and in the least variety in viewer characteristics. These results seem to strengthen conclusions by Eden et al.(2017, p. 150), who stated that “… moral rumination may be tied specifically to the conflict presented in the storyline, the specific act featured, or the ambiguity of moral resolution provided by the narrative,” maybe even more so than viewer characteristics.

As with all studies, this study also had its limitations which provide interesting avenues for future research. By focusing on 13 Reasons Why as a series, the topics of moral rumination are inherently tied to themes of guilt and responsibility, issues with mental health, and sexually transgressive behaviors, whereas other morally controversial shows like, for example, the controversial Euphoria (2019, created and written by Sam Levinson) might introduce other topics for viewers to ruminate about. Additionally, one might wonder if encountering similar themes in a different genre might impact the extent to which moral rumination arises. Sex Education (2019, created by Laurie Nunn) deals with similar topics of, for example, sexual consent, responsibility, and harassment in a layered and complex way, but is presented as a dramedy rather than a drama series. Will the genre impact the possibility for moral rumination, or might the complex presentation of the themes be enough for the viewer to come to ruminate on these themes? To assess if the current findings are also transferable to other fictional content focusing on other (controversial) topics, future qualitative and quantitative research is needed to establish this.

Additionally, the age of the sample of participants should be diversified in future research to assess if older participants might be more capable of and willing to reflect on experiences they had in their teen years or if these ruminations might be most prevalent for teenagers themselves. Viewer characteristics connoting individual differences such as explication of experiences similar to the content need for closure, and levels of moral maturity could also be explicated as sampling strategies in future research.

Finally, since the development of moral rumination as a concept—even with the newly articulated variations of morally conclusive and morally inconclusive rumination—is still very much under development, new research is also needed to more clearly delineate what moral rumination is and how it might impact moral growth, moral maturity, and aspects of psychological wellbeing. Future research should therefore build on the current study and endeavor to take the variations of morally conclusive and morally inconclusive rumination into consideration as well.

In conclusion, the current study more fully explored moral rumination as a result of morally complex television content and thereby extends the study by Eden et al. (2017) on moral rumination. Our findings suggest that this type of popular, morally complex media content promotes moral rumination from a great variety of antecedents, causes reflection and meaningful thought in viewers, and, as such, might add to the psychological wellbeing of viewers. In line with the study conducted by Lauricella et al. (2018), the participants in this study found the content of the show very meaningful, used it for reflection on a difficult subject, and sometimes even reached a sense of closure on a complex part of their life story. Where in communication science, in general, controversial media is often seen as a gateway to negative effects, this study sheds a more positive, constructive, and contemplative outlook on this type of morally complex content, thereby adding to the growing body of literature which can be seen as positive media psychology or positive communication science (Raney et al., 2019, 2020).

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the dataset is not available online. Due to the ethically sensitive nature of the interview (topics) the informed consent guaranteed full confidentiality of the interview transcripts for all participants. The researchers are available to answer specific questions regarding the data. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to c2VyZW5hLmRhYWxtYW5zQHJ1Lm5s.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Ethics Committee Faculty of Social Sciences (ECSW2017-2306-525), Radboud University. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

SD, AW, and MK contributed to conception and design of the study. SD and AW collected the data. SD and CV conducted the analyses. SD wrote the first draft of the manuscript. AW and MK provided feedback on the manuscript and rewrote sections. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. ^A short summary for all the episodes of the first season can be found here: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt1837492/episodes?season=1.

2. ^The dataset is not available online. Due to the ethically sensitive nature of the interview(topics) the informed consent guaranteed full confidentiality of the interview transcripts for all participants. The researchers are available to answer specific questions regarding the data.

3. ^The list refers to Season 1, Episode three (“Tape 2, Side A”: https://tvtropes.org/pmwiki/pmwiki.php/Recap/ThirteenReasonsWhyS01E03Tape2SideA:) When Alex and Jessica broke up, he created a “Hot List,” where he awards Hannah with “Best Ass” and Jessica with “Worst Ass.” The unfortunate side-effect of all the boys – and particularly Bryce - assume the list means Alex has had sex with Hannah. This rumor solidifies Hannah's promiscuous reputation and ruins her friendship with Jessica, who blames her breakup on Hannah.

Arendt, F., Scherr, S., Pasek, J., Jamieson, P. E., and Romer, D. (2019). Investigating harmful and helpful effects of watching season 2 of 13 reasons why: results of a two-wave US panel survey. Soc. Sci. Med. 232, 489–498. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.04.007

Bartsch, A., Kalch, A., and Oliver, M. B. (2014). Moved to think: the role of emotional media experiences in stimulating reflective thoughts. J. Media Psychol. 26, 125–140. doi: 10.1027/1864-1105/a000118

Bartsch, A., and Mares, M. L. (2014). Making sense of violence: Perceived meaningfulness as a predictor of audience interest in violent media content. J. Commun. 64, 956–976. doi: 10.1111/jcom.12112

Bartsch, A., Mares, M. L., Scherr, S., Kloß, A., Keppeler, J., and Posthumus, L. (2016). More than shoot-em-up and torture porn: reflective appropriation and meaning-making of violent media content. J. Commun. 66, 741–765. doi: 10.1111/jcom.12248

Bilandzic, H. (2006). The perception of distance in the cultivation process: A theoretical consideration of the relationship between television content, processing experience, and perceived distance. Commun. Theor. 16, 333–355. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2885.2006.00273.x

Boeije, H. (2002). A purposeful approach to the constant comparative method in the analysis of qualitative interviews. Qual. Quant. 36, 391–409. doi: 10.1023/A:1020909529486

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2013). Successful Qualitative Research: A Practical Guide for Beginners. London: Sage.

Bridge, J. A., Greenhouse, J. B., Ruch, D., Stevens, J., Ackerman, J., Sheftall, A. H., et al. (2020). Association between the release of Netflix's 13 reasons why and suicide rates in the United States: an interrupted time series analysis. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 59, 236–243. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2019.04.020

Carroll, N. (2000). Art and ethical criticism: an overview of recent directions of research. Ethics 110, 350–387. doi: 10.1086/233273

Carter, M. C., Cingel, D. P., Lauricella, A. R., and Wartella, E. (2020). 13 reasons why, perceived norms, and reports of mental health-related behavior change among adolescent and young adult viewers in four global regions. Commun. Res. 48, 1110–1132. doi: 10.1177/0093650220930462

Chesin, M., Cascardi, M., Rosselli, M., Tsang, W., and Jeglic, E. L. (2020). Knowledge of suicide risk factors, but not suicide ideation severity, is greater among college students who viewed 13 reasons why. J. Am. College Health 68, 644–649. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2019.1586713

Chisholm, B. (1991). Difficult viewing: the pleasures of complex screen narratives. Crit. Stud. Mass Commun. 8, 389–403. doi: 10.1080/15295039109366805

Cingel, D. P., Lauricella, A. R., Mann, S., Carter, M. C., and Wartella, E. (2021). Parent sensitive topic understanding, communication comfort, and parent-adolescent conversation following exposure to 13 reasons why: a comparison of parents from four countries. J. Child Family Stud. 30, 1–12. doi: 10.1007/s10826-021-01984-6

Collier, J. (1967). Visual Anthropology: Photography as a Research Method. New York, NY: Holt; Rhinehart and Winston.

Daalmans, S., Kleemans, M., Eden, A., and Weijers, A. (2018). “Exploring characters development as a central mechanism in viewer responses to morally ambiguous characters,” in Presented at the Annual Conference of the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication (Washington, DC: AEJMC).

Dill-Shackleford, K. E., Vinney, C., and Hopper-Losenicky, K. (2016). Connecting the dots between fantasy and reality: the social psychology of our engagement with fictional narrative and its functional value. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 10, 634–646. doi: 10.1111/spc3.12274

Eden, A., Daalmans, S., Van Ommen, M., and Weijers, A. (2017). Melfi's choice: morally conflicted content leads to moral rumination in viewers. J. Media Ethics 32, 142–153. doi: 10.1080/23736992.2017.1329019

Eden, A., Grizzard, M., and Lewis, R. (2011). Disposition development in drama: the role of moral, immoral and ambiguously moral characters. Int. J. Arts Technol. 1, 33–47. doi: 10.1504/IJART.2011.037768

Ferguson, C. J. (2019). 13 Reasons why not: a methodological and meta-analytic review of evidence regarding suicide contagion by fictional media. Suicide Life-Threat. Behav. 49, 1178–1186. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12517

Gopaldas, A., and Molander, S. (2020). The bad boy archetype as a morally ambiguous complex of juvenile masculinities: the conceptual anatomy of a marketplace icon. Consumpt. Mark. Cult. 23, 81–93. doi: 10.1080/10253866.2019.1568998

Hall, S. (1993). “Encoding, decoding,” in The Cultural Studies Reader, ed S. During (New York, NY: Routledge), 90–103.

Hong, V., Ewell Foster, C. J., Magness, C. S., McGuire, T. C., Smith, P. K., and King, C. A. (2019). 13 reasons why: viewing patterns and perceived impact among youths at risk of suicide. Psychiat. Serv. 70, 107–114. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201800384

Jacobson, S. L. (2017). Thirteen reasons to be concerned about 13 reasons why. Brown Univ. Child Adolesc. Behav. Lett. 33, 8–8. doi: 10.1002/cbl.30220

Johnson, B. K., Ewoldsen, D. R., and Slater, M. D. (2015). Self-control depletion and narrative: testing a prediction of the TEBOTS model. Media Psychol. 18, 196–220. doi: 10.1080/15213269.2014.978872

Katz, E., and Liebes, T. (1990). Interacting with dallas: cross-cultural readings of American TV'. Can. J. Commun. 15, 45–65.

Katz, E., Liebes, T., and Berko, L. (1992). On commuting between television fiction and real life. Quart. Rev. Film Video 14, 157–178.

Keen, R., McCoy, M. L., and Powell, E. (2012). Rooting for the bad guy: psychological perspectives. Stud. Popular Cult. 34, 129–148. Available online at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/23416402

King, P. M., and Kitchener, K. S. (1994). Developing Reflective Judgment: Understanding and Promoting Intellectual Growth and Critical Thinking in Adolescents and Adults (San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass).

Kleemans, M., Eden, A., Daalmans, S., van Ommen, M., and Weijers, A. (2017). Explaining the role of character development in the evaluation of morally ambiguous characters in entertainment media. Poetics 60, 16–28. doi: 10.1016/j.poetic.2016.10.003

Knobloch-Westerwick, S., Gong, Y., Hagner, H., and Kerbeykian, L. (2013). Tragedy viewers count their blessings: feeling low on fiction leads to feeling high on life. Commun. Res. 40, 747–766. doi: 10.1177/0093650212437758

Korrelatie. (2015). Over MIND Korrelatie. Available online at: https://mindkorrelatie.nl/over-korrelatie/over-mind-korrelatie

Lauricella, A. R., Cingel, D. P., and Wartella, E. (2018). Exploring How Teens, Young Adults, and Parents Responded to 13 Reasons Why. Evanston, IL: Center on Media and Human Development, Northwestern University.

Livingstone, S. M. (1990). Interpreting a television narrative: how different viewers see a story. J. Commun. 40, 72–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.1990.tb02252.x

Mar, R. A., and Oatley, K. (2008). The function of fiction is the abstraction and simulation of social experience. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 3, 173–192. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6924.2008.00073.x

Michelle, C. (2007). Modes of reception: A consolidated analytical framework. Commun. Rev. 10, 181–222. doi: 10.1080/10714420701528057

Min, L. (2017). '13 Reasons Why' Is Netflix's Most Popular Show on Social Media. TeenVogue. Consulted via. Available online at: https://www.teenvogue.com/story/13-reasons-why-netflix-most-popular-show-social-media (accessed July 20, 2022).

Niederkrotenthaler, T., Stack, S., Till, B., Sinyor, M., Pirkis, J., Garcia, D., et al. (2019). Association of increased youth suicides in the United States with the release of 13 reasons why. JAMA Psychiatry 76, 933–940. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.0922

Oliver, M. B., and Bartsch, A. (2010). Appreciation as audience response: exploring entertainment gratifications beyond hedonism. Hum. Commun. Res. 36, 53–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2958.2009.01368.x

Oliver, M. B., and Hartmann, T. (2010). Exploring the role of meaningful experiences in users' appreciation of “good movies”. Projections 4, 128–150. doi: 10.3167/proj.2010.040208

Patton, M. Q. (2002). Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods: Integrating Theory and Practice. London: Sage publications.

Pauwels, L. (1996). De verbeelde samenleving: Camera, kennisverwerving en communicatie [The imagined society: Camera, knowledge- acquisition and communication]. Leuven: Garant.

Raney, A. A. (2004). Expanding disposition theory: Reconsidering character liking, moral evaluations, and enjoyment. Commun. Theor. 14, 348–369. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2885.2004.tb00319.x

Raney, A. A., Janicke-Bowles, S. H., Oliver, M. B., and Dale, K. R. (2020). Introduction to Positive Media Psychology. New York, NY: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780429353482

Raney, A. A., Oliver, M. B., and Bartsch, A. (2019). “Eudaimonia as media effect,” in Media Effects: Advances in Theory and Research: Fourth Edition (New York, NY: Routledge), 258–274. doi: 10.4324/9780429491146-17

Ryan, M. (2017a). ‘13 Reasons Why' Avoids TV's Routine Exploitation of Dead Women by Forcing Us to Care. Available online at: https://variety.com/2017/voices/columns/netflix-13-reasons-why-1202022770/

Ryan, M. (2017b). TV Review: ‘13 Reasons Why' on Netflix. Available online at: https://variety.com/2017/tv/uncategorized/13-reasons-why-review-netflix-selena-gomez-dylan-minnette-katherine-langford-1202013547/

Sanders, M. S. (2010). Making a good (bad) impression: examining the cognitive processes of disposition theory to form a synthesized model of media character impression formation. Commun. Theory 20, 147–168. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2885.2010.01358.x

Scalvini, M. (2020). 13 reasons why: can a TV show about suicide be ‘dangerous'? What are the moral obligations of a producer? Media Cult. Soc. 42, 1564–1574. doi: 10.1177/0163443720932502

Scherr, S., Bartsch, A., Mares, M.L., and Oliver, M. (2017). “Measurement invariance and validation of a new scale of reflective thoughts about media violence across countries and media genres,” in Paper Presented at the Annual Meeting of the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication (AEJMC) (Chicago, IL, United States).

Shafer, D. M., and Raney, A. A. (2012). Exploring how we enjoy antihero narratives. J. Commun. 62, 1028–1046. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.2012.01682.x