- 1Doctoral Program in Design, College of Design, National Taipei University of Technology, Taipei, Taiwan

- 2Department of Interaction Design, College of Design, National Taipei University of Technology, Taipei, Taiwan

Idol-nurturing reality shows that aim to produce idol groups by audience-chosen have become a hotbed for nurturing celebrities. The unique concepts and designs of idol-nurturing reality shows have attracted a group of committed female fans. As a result, the idol-nurturing reality show has become an essential genre of reality shows in the Asian market and an essential part of idol culture. This study concerned the unique concepts and designs of idol-nurturing reality shows and the psychology and behavior of the fans throughout the shows. Results of structural equation modeling based on survey data with 3,352 young Chinese respondents revealed a significant relationship between prompts, motives, online fan engagement, celebrity worship, and program commitment. The data from this study show that the prompts ability, personality, and facial attractiveness positively impacted online fan engagement and that viewing motives social interaction, voyeurism, and suspense positively impacted online fan engagement. In addition, this study found that online fan engagement exerted a significant and positive effect on celebrity worship and program commitment; celebrity worship positively impacted program commitment. This study also provides suggestions on enhancing the fan stickiness of shows and idols.

Introduction

The beginning of the twenty-first century has seen an explosion in the growth of reality shows (Hill, 2005). As a result, numerous ordinary people rose to fame through reality shows. The unique path to fame of reality stars has become an essential part of celebrity studies. Today, reality shows are widely enjoyed worldwide, and many subgenres have emerged, such as the idol-nurturing reality show discussed in this paper. The idol-nurturing reality show was derived from the Korean pop culture trend “Hallyu.” The Produce 101 series produced by Korean television production teams is undoubtedly one of the most successful idol-nurturing reality shows. Catering to more local audiences, production teams of Chinese shows are also actively learning from Korean models and incorporating Chinese audiences' preferences to create idol-nurturing reality shows that audiences will like. After several years of development, idol-nurturing reality show, which not only combines characteristics of talent shows and reality shows but also focuses on nurturing idol stars and recruiting fans, has become an Asian-class phenomenon in idol culture, garnered numerous committed young audiences, and exerted a significant impact on the viewing behavior of audiences. Many ordinary young people have become household names through idol-nurturing reality shows. For instance, Cai Xukun won the competition in the Chinese idol-nurturing reality show Idol Producer and became a well-known celebrity through the show. To send Cai Xukun to the winning spot on that show, his fans cast 47.64 million votes for him in only 12 days (Jing, 2018), and raised a total of RMB 3.13 million during the show.

Several studies indicate that young Chinese people favor consumption-type idols more (He, 2006; Zhao, 2019), who usually are celebrities and meet people's entertainment and recreational needs. In a study on the celebrity worship of young Chinese people, He (2006) discovered that stars, including pop song stars and film stars, were often the celebrities most popular among young people. These findings explain why idol-nurturing reality shows are popular with young Chinese audiences. With the advantages that come with the era of Web 3.0, new digital media technologies gather highly active, involved, and engaging fans together, which also makes it easier to prompt idol-targeting online fan engagement. Due to these social settings, idol-nurturing reality shows have achieved impressive results in the Chinese market.

Research points out that TV broadcasters have begun building and maintaining the relationship between viewers and programs through increasing viewer engagement behaviors. Most existing studies on idol-nurturing reality shows were conducted from a show-centric perspective; however, few studies have been conducted from an audience-centric viewpoint. Therefore, this study aims to investigate the motives of viewers to watch idol-nurturing reality shows through the modern uses and gratifications theory. Furthermore, drawing on insights from the Fogg Behavior Model (2009, 2019) and investment model (Rusbult et al., 2011), this study allows for a systematic link between designs of the idol-nurturing reality show, motives, and fan engagement behaviors. From an audience-centered perspective, we conducted structural equation modeling to analyze the associations between program design, viewing motive, online fan engagement, and the impact of various forms of online fan engagement on celebrity worship and program commitment. And the study intended to investigate the following three questions through questionnaire data provided by 3,352 young Chinese viewers of idol-nurturing reality shows.

RQ1: Is there an association between different types of prompts and online fan engagement among the respondents?

RQ2: Is there an association between different viewing motives and engagement among the respondents?

RQ3: Is there an association between online fan engagement, celebrity worship, and program commitment among the respondents?

Theoretical background

Idol-nurturing reality shows in Asia

The idol star system (also known as the trainee system) originated in Japan and developed into a unique model under the unique music market and market digitization transition in South Korea (Fuhr, 2015; Yoon, 2018). The entertainment companies provided professional environments to groom trainees in the trainee system. In return, they profited from the various activities (such as music sales, performances, and advertisements) following their debut (Fuhr, 2015). The comprehensive trainee systems of the major entertainment companies provide the primary conditions for producing idol-nurturing reality shows (Xia, 2018). For this reason, the earliest idol-nurturing reality shows were produced by the major entertainment companies themselves.

What made idol-nurturing reality shows run into the general audience's vision is the Produce 101 series, produced by Korean television channel Mnet since 2016. Produce 101 series received high ratings for viewership, Produce 101 peaked at 4.4%, and Produce 101 Season 2 peaked at 6.4%. Aside from these shows themselves, temporary idol groups selected by audience members of the shows, such as I.O.I, Wanna One, and IZ*ONE, have also performed well in the Asian music market. For instance, Wanna One became the first temporary idol group whose debut album sold over a million copies. The Produce 101 series has supplied a significant number of young stars for Asia (Park, 2019) and has contributed to the overall development of the idol industry. Due to Korea's attention and huge profits, the program model has also been successfully promoted to the reality show industry in China and Japan. Chinese production teams adapted the Produce 101 series model and created shows including Idol Producer and Produce 101 China, which have been popular in the domestic Chinese and overseas markets (Xia, 2018). As of the third quarter of 2020, Produce 101 China, for example, had accumulated over six billion online views on Tencent Video as well as over 100 million discussions and 16 billion views on the social platform Sina Weibo. In 2019, the annual sales on QQ Music involving Rocket Girls 101, a temporary idol group selected by Produce 101 China, reached RMB 19,083,466.

Specifically, the model adopted by the Produce 101 series mainly has the following characteristics: (1) Produce 101 series aims to produce an idol group by audience voting. (2) Produce 101 series uses a variety forms of prompts to display the professional abilities of the trainees, as well as the personalities and life details of the trainees. (3) Produce 101 series officially designs various interactive activities for the audience to engage with the shows and the trainees online. The concept of audience-driven develops a deep emotional connection between the fans and the trainees in the shows, making fans more willing to express their favor by participating in online fan engagement activities. The 11 aforementioned idol-nurturing reality shows, including Produce 101, Produce 101 Season 2, Produce 48, Produce X 101, Produce 101 Japan, Idol Producer, Produce 101 China, Youth With You 1, CHUANG 2019, Youth With You 2, and CHUANG 2020, served as the primary research targets of this study.

The designs of idol-nurturing reality shows, motives, and online fan engagement

Online fan engagement

The commercial market in the twenty-first century has adequately demonstrated and stressed the importance of fan study. The influence of fans is disrupting the status of mainstream media to a point in which anyone has the potential to become a dedicated fan with enormous influence. In fact, “celebrity” covers a broader range of categories (He, 2006; Lowenthal, 2017; Zhuang, 2019). Each type of celebrity has its unique development model and fan characteristics, whereby generalizing them is challenging and unsuitable. With the unique context of idol-nurturing reality shows, we define celebrities as the trainees competing in the idol-nurturing reality shows and acquiring new fans through the shows. Based on the objectives and background of this study, we defined online fan engagement as the fan behaviors displayed by fans online in the context of idol-nurturing reality shows. Online fan engagement aims to benefit the trainees whom the fans like, increase the online influence of trainees (Zhang and Negus, 2020), help trainees go from obscure to celebrity and build as well as enrich the emotional relationships between fans and the trainees.

American media scholar Henry Jenkins (2012) was the first to mention the concept of participatory culture. He advocated that emotions such as infatuation, admiration, or worship are not enough to encompass all of the characteristics of fans. Fans are not just people who regularly view a show; their viewing behavior may extend and evolve to other activities, such as sharing their feelings with friends, joining fan communities, participating in discussions, or even creating fan fiction. Fiske (2010) also noted that fans generally display active, participatory, and fanatical behavior to express their enthusiasm. The degree of enthusiasm that fans have for idols has not changed with time; even today, with the help of technology, fan engagement behavior has become increasingly diverse and easier to exhibit. One could say that the internet has completely removed the final barriers created by time, place, and money (Fraade-Blanar and Glazer, 2017; Hou, 2018). In the broad context of the internet era, Jenkins et al. (2015) continued to stress the crucial social meaning of fan engagement; he maintained a positive and optimistic attitude toward the participatory culture in the internet era and expressed approval for the energy, activity, and initiative displayed by fans. Online platforms have become an essential condition for swift and steady progress in the idol industry. For this reason, this study focused on online fan engagement rather than offline fan activities.

Prompts designed by the idol-nurturing reality shows

Fogg Behavior Model states that promoting the target behavior requires adequate motive, sufficient ability, and an appropriate prompt (Fogg, 2019). Prompts come in various forms, such as text, sound, image, or video. Fogg divided prompts into three categories based on their function: sparks, facilitators, and signals. A spark is a prompt that can provide a motive, a facilitator is a prompt that makes it easier to exhibit a target behavior, and a signal serves as a reminder (Fogg, 2019).

The literature review reveals how prompt influences human's watching behavior in the context of the idol-nurturing reality show. Yu and Nam (2018) indicated that the idol-nurturing reality show, Produce 101, designed a series of activities that interacted with the show through a mix of social media to break the deadlock caused by the rise of mobile devices and the diminishment of the television industry. New media lowered the threshold for user behavior achievement and brought greater convenience (Xu, 2017). Therefore, besides traditional TV broadcast channels, idol-nurturing reality shows are also broadcast through streaming platforms. For example, Idol Producer and Produce 101 China were broadcast through streaming platforms. In addition, the broadcasters designed a series of online ads to recommend the shows to potential subscribers and successfully promoted their viewing behaviors.

Unlike ordinary singing competition shows, idol-nurturing reality shows pay much attention to the presentation of the character and life details of the trainees. During semi-structured interviews, many of the interviewees indicated that the most critical factors prompting them to watch the shows were video materials that showcase the trainees' strengths and stage performance abilities, followed by the attractiveness of the competing trainees about whom they cared. Charisma, contrasting personality traits, and the growth of the trainees were also relevant factors. Some interviewees also indicated that they began watching the shows because their friends watched. Viral videos on social media also prompted them to watch the shows. In conclusion, this study found that the Produce 101 series designed a series of prompts that showcase the trainees' ability, personality, and facial attractiveness, as well as improved the social impact of the shows and the trainees to prompt viewing behaviors and fan engagement. Based on the discussion above, we present the following hypotheses:

H1–H4: The prompts ability (AB), personality (PE), facial attractiveness (FA), and social impact (SCI) are positively correlated with online fan engagement (OFE).

Uses and gratifications theory of idol-nurturing reality shows

Research on the television-viewing motives of audiences from the perspective of uses and gratifications theory has been ongoing. In the 1980s, Rubin (1984) confirmed two general types of television viewing: ritualistic and instrumental. Ritualistic viewers frequently watch television out of habit. Such viewers care more about television as a form of media than about the content of television programs. Their television use is typically non-selective, uninvolved, and less active, and their primary motives for watching television are habit, passing time, relaxation, escape, and convenience (Rubin, 1984; Rubin and Perse, 1987). In contrast, instrumental viewers are more likely to purposefully select specific programs to watch and be more active and involved in viewing activities (Rubin, 1984). Their viewing motives include pursuing information, entertainment, and behavior guidance (Rubin, 1984). Researchers have proposed other television-viewing motives, such as pursuing parasocial interactions when watching news programs (Palmgreen et al., 1980). Some types of programs meet viewers' surveillance and voyeurism needs (Bantz, 1982). Papacharissi and Mendelson (2007) constructed a reality TV motives scale. They identified six motives that prompt people to watch reality shows: reality entertainment, relaxation, habitual passing time, companionship, social interaction, and voyeurism.

The Chinese market has the largest television audience in the world. However, research on the Chinese television industry from the uses and gratifications theory perspective still lags behind industry development. For over a decade, Chinese researchers (Zhao, 2014; Xu and Guo, 2018) have begun investigating the reasons behind the popularity of singing competition reality shows in the Chinese market and the needs that audiences seek to fulfill. The researchers (Zhao, 2014; Xu and Guo, 2018) identified the needs that Chinese audiences watching singing competition reality shows such as The Voice of China wanted to satisfy, which included entertainment, relaxation, habitual passing time, surveillance, vicarious participation, voyeurism, perceived reality, social interaction, companionship, ambition, social interaction, high production quality, and suspense. Xu and Guo (2018) also found that social interaction and high production quality were more strongly correlated with Chinese audiences' viewing and post-viewing activities.

In addition to the traditional media, the use of gratification theory is still widely applied in the new media today. For example, Lin and Chu (2021) noted in their study that the gratifications including entertainment, network extension, recognition, and emotional support provided by Facebook could induce intimate relationships between the users and Facebook. The researchers have also studied users' behavioral motives for using Instagram through the uses and gratifications theory. They pointed out that the needs for self-enhancement, entertainment, and deal-seeking behavior have a significant effect on users' intention to follow brands on Instagram, and social media usage indirectly affects consumption decisions (Madan and Kapoor, 2022). Menon (2022) identified eight motives for using over-the-top video streaming platforms in his study, using data provided by 576 Indian users, including convenient navigability, binge watching, entertainment, relaxation, social interaction, companionship, voyeurism, and information seeking.

Idol-nurturing reality shows have the traits of both reality television shows and singing competition shows. Thus, studies investigating the viewing motives of audiences with regard to reality shows and singing competition reality shows from the uses and gratifications theory perspective can provide us with reliable references for this study. It is important to note that idol-nurturing reality shows in Korea and Japan are broadcast on traditional television, while in China they are broadcast on video streaming platforms. Therefore, the findings of Menon (2022) are also informative. Research has shown that viewing reality shows is associated with certain motives (Ebersole and Woods, 2007). Based on results from existing studies, we can assume that people watch certain shows more frequently as well as display greater engagement and activity participation when they have stronger viewing motives. Based on the discussion above, we present the following research question and hypotheses:

H5–H9: Relaxation (RE), social interaction (SI), voyeurism (VO), high production quality (HPQ), and suspense (SU) are positively correlated with online fan engagement (OFE).

Celebrity worship and program commitment

Celebrity worship most commonly refers to a social psychological phenomenon that mainly occurs during adolescence, which is closely related to adolescents' emotions, thinking, and self-awareness (He, 2006; Zhao, 2019). Enthusiasm toward a celebrity is a continuum ranging from healthy appreciation to pathological worship (Zsila et al., 2018). In this study, celebrity worship is defined as excessive enthusiasm and obsession with a famous person, with a strong psychological identification and devout emotional attachment at its core. Fans with celebrity worship cognitively and emotionally adore their favored celebrities and make their relationship with their favored celebrities the primary focus of their life. Celebrity worship is characterized by loyalty and willingness to invest time and money in their favored celebrities and even imitate their image, behavior, and way of thinking (Brown, 2015; Yue et al., 2018).

Western research has been quantifying celebrity worship for a long time and is more systematic and enriched. The results published by McCutcheon et al. (2002) have the most advanced logic as well as the richest facts and details (Singh and Banerjee, 2019). Based on the celebrity attitude scale, they proposed that the three crucial dimensions of celebrity worship can be further explained using the absorption-addiction model, which describes that fans seek satisfaction in celebrity worship and, in turn, stimulates them to focus their personal attention on the celebrity whom they like, generate dynamic and enthusiastic behavior or emotional investment, and identify with that celebrity. Like physiological addiction, fans must be even more engaged to derive satisfaction. Based on this model, researchers indicated that celebrity worship comprises three dimensions, which from a low to a high level of involvement are the entertainment-social dimension, the intense-personal dimension, and the borderline-pathological dimension (McCutcheon et al., 2016). Celebrity worship with low involvement remains on the entertainment and social aspects. Most fans with this level of celebrity worship discuss celebrities and their daily lives with their friends for social and entertainment value. Fans with an intermediate level of celebrity worship begin to form strong personal and emotional attachments and often feel that their idols are their soul mate. Highly involved celebrity worship brings about borderline-pathological, which reflects an individual's social-pathological attitudes and behaviors (Maltby et al., 2006). Such fans may even display illegal actions because of excessive obsessions with their idols (McCutcheon et al., 2002; Peng et al., 2010).

Past research indicated that entertainment-social celebrity worship tends to be the most common, followed by intense-personal celebrity worship, while borderline-pathological celebrity worship is uncommon (Brooks, 2021). Fans with non-pathological celebrity worship are thoughtful and willing to help others, and they are usually the ones who can build fan clubs (Stever, 1995). However, pathological celebrity worship is generally associated with unhealthy psychological conditions. It is accompanied by very intense and pathological celebrity worship behaviors such as erotomania, stalking, improper coherence with celebrities, obsessive thoughts, suicide attempts, and difficulty maintaining intimate relationships (Singh and Banerjee, 2019; McCutcheon and Aruguete, 2021).

In view of the fact that celebrity worship may have different meanings under the social backgrounds of different countries, it is also of upmost importance to examine the scales of attitudes toward celebrities in different cultural backgrounds. Peng et al. (2010) investigated whether the celebrity attitude scale applies to the social environment in China, developed a Chinese version, and demonstrated that the celebrity attitude scale and the underlying absorption-addiction model are effective instruments for measuring celebrity worship among adolescents. The absorption-addiction model also provides a valuable reference for the relationship between online fan engagement and celebrity worship; therefore, we formulated the following hypothesis:

H10: Online fan engagement (OFE) is positively correlated with celebrity worship (CW).

In social psychology, commitment refers to an individual's long-term attitudes and tendencies toward a relationship, including psychological attachment and persistence (Rusbult, 1983). Anderson and Weitz (1992) defined commitment as the desire to develop a steady relationship, the willingness to make short-term sacrifices to maintain a said relationship, and the confidence in the relationship's stability. In this study, we define program commitment as audiences' long-term attitudes and tendencies toward idol-nurturing reality shows such as the Produce 101 series, their desire to develop steady relationships with the shows, their willingness to maintain the relationships, and their confidence in the stability of the relationships. Commitment plays a crucial role in a continued relationship; therefore, we aimed to further understand online fan engagement and celebrity worship through program commitment. According to the investment model, investment size is a crucial predictor of program commitment. Investment size refers to the magnitude and importance of the intrinsic and extrinsic resources invested in a relationship. In the context of idol-nurturing reality shows, intrinsic investment relates to time, emotions, and self-expression; and extrinsic investment refers to fans' interpersonal relationships, money, etc. (Rusbult and Buunk, 1993). A strong commitment is more likely to induce audiences to maintain their relationship with a show (Rusbult, 1983) and make them more willing to invest in a close relationship (Van Lange et al., 1997). In a study on television audiences, Lin et al. (2016, 2018) found that audiences can enhance their television-viewing experience by engaging in social television activities and interacting with other viewers via the show. Cooperation between shows and relevant social media services can also increase the engagement of target audiences in social television events. In turn, this generates a higher level of program commitment toward the show. Based on the research achievements above, we formulated the following hypothesis:

H11: The online fan engagement (OFE) level is positively correlated with program commitment (PC).

McCutcheon and Aruguete (2021) found that the proportion of celebrity worshipers increased dramatically from 2001 to 2021, as did the psychological and behavioral problems associated with celebrity worship. Previous research showed that celebrity worship is often accompanied by a lack of social skills and addictive behaviors, such as problematic internet use and compulsive buying (Reeves et al., 2012; Zsila et al., 2021). However, celebrity worship not only comes with problems; the research also suggested that celebrity worship positively affects fan consumers' perceptions of brands. For example, Parmar and Mann (2020) demonstrated that celebrity worship directly and positively affects brand equity. And consumer self-brand connection plays a mediating role in the effect of celebrity worship on brand equity. In another aspect, research has found that celebrity worship is also directly and positively related to advertising attitude and purchase intention (Singh and Banerjee, 2019). This result verifies the argument Kamins et al. (1989) presented: celebrities make advertisements more attractive to consumers and improve consumer assessments of ads. In their study, Chen et al. (2022) noted that cooperating with celebrities has become an important marketing strategy many companies use to attract fan consumers, whose brand loyalty is positively influenced by celebrity worship. This is because fans with celebrity worship have a strong emotional attachment to their favorite celebrities. This unique relationship leads consumers to imitate celebrities to enhance themselves (Mukherjee, 2009). The latest celebrity worship study also found that the emotional engagement between fans and digital celebrities also improves their purchase intentions for the goods recommended by the digital celebrities (My-Trinh and Huong-Linh, 2021).

It is important to note that in some situations, incongruence between the celebrity and the endorsed product and consumers perceiving the celebrity to have far more significant influence than the brand can prevent consumers from associating brands with the celebrity (Singh and Banerjee, 2019). In the context of idol-nurturing reality shows, however, the idols competing in the shows are closely tied to the shows. Therefore, the relationship is one of mutual influence. In the semi-structured in-depth interviews of this study, the interviewees mentioned on their own accord that whether the trainees whom they supported were eliminated affected whether they continued watching the show. In other words, idols help audiences form attitudes toward the show; if fans invest more emotions in a trainee, their emotions are more likely to spread to the entire show. Based on the discussion above, we put forward the following hypothesis:

H12: Celebrity worship (CW) is positively correlated with program commitment (PC).

Method

This study completed the data collection through an online questionnaire in May 2020. Prior to this, the study interviewed 10 veteran idol-nurturing reality show viewers through semi-structured in-depth interviews. All respondents to the semi-structured in-depth interviews were young viewers under the age of 30, had seen at least six different idol-nurturing reality shows, and had joined a fan club or had spent more than RMB 1,000 for a contestant during the course of the show. Our interviews with the interviewees focused on four aspects: (a) interviewees' basic information and viewing habits about idol-nurturing reality shows; (b) interviewees' basic information and viewing habits about idol-nurturing reality shows; (c) what prompt drives interviewees' viewing behaviors; (d) the types of online fan engagement that fans engage in while watching the Produce 101 series.

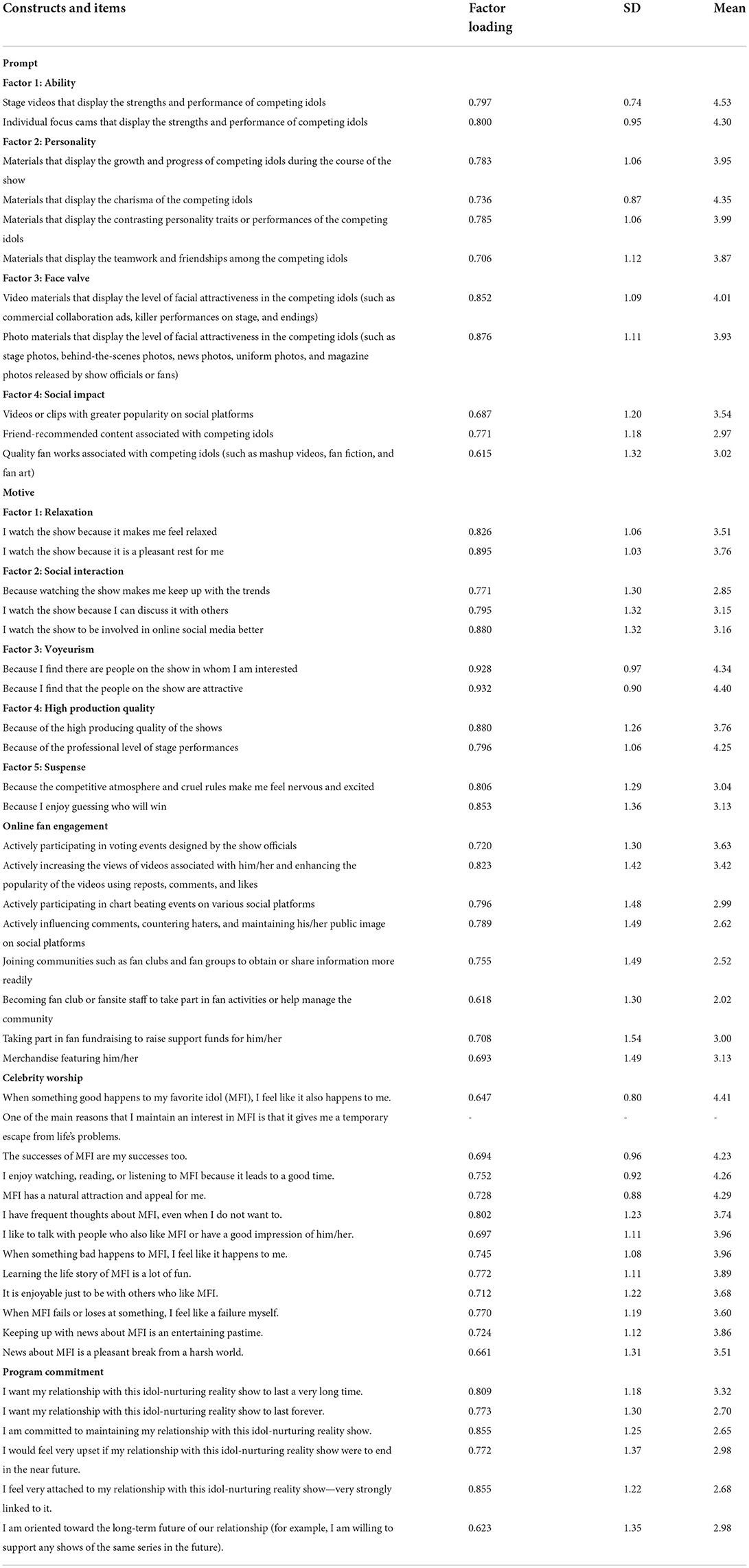

After analyzing the senior viewers' perspectives, this study defined 11 items about prompts. First, some of the interviewees care a lot about the abilities of idols on stage. They usually began watching the shows because they saw trainees performing well in the promotional videos. Secondly, personality prompts also play an essential role. One of our interviewees managed the entire run of CHUANG 2019. Her favorite part of the show was seeing the trainees' interactions, real personalities, and everyday details through the behind-the-scenes videos. A loyal fangirl of the Korean Produce 101 series mentioned that facial attractiveness is the bottom line standard for her. And other interviewees provided similar views. And professional fangirls believe that quality fan works also prompt viewing behavior, and producing popular content on social media is vital to the shows. Based on the above, we divided the items of prompts into four dimensions: ability, personality, facial attractiveness, and social impact. The online behavior of fangirls was the focus of this study. With the help of our interviewees, we compiled the various forms of Online fan engagement that appear in the context of idol-nurturing reality shows. As shown in Table 1, the final measurement scale for online fan engagement contained eight items.

Measurement items for motive, celebrity worship, and program commitment were adapted from the scales used in previous studies. There were five types of motives: reality entertainment, social interaction, voyeurism, high production quality, and suspense (Papacharissi and Mendelson, 2007; Xu and Guo, 2018). Celebrity worship was gauged using the celebrity attitude scale (McCutcheon et al., 2002). To measure program commitment, we adopted the scale that Lin et al. (2016) derived through their revision of the scales developed by Rusbult (1983) and Sung and Choi (2010). A pre-study of 322 respondents was conducted with minor modifications to the study questionnaire before the formal questionnaire was administered. The results of the exploratory factor analysis of the pre-study showed that the factor loadings of the borderline-pathological items and some of the intense-personal items in the celebrity attitude scale did not reach 0.5. We removed these items with too low factor loadings, and the final measurement of celebrity worship contained 13 items.

Based on our literature review, the main group of people in China who admire idols and create a series of fan engagement activities are adolescents (He, 2006; Zhao, 2019). Therefore, the study questionnaire was mainly placed on popular social media sites in China, and young users under the age of 30 were invited to respond. Respondents were initially screened with the question, “Have you ever watched any idol-nurturing reality shows such as the Produce 101 series?”. Then, respondents were asked to pre-select an idol-nurturing reality show as the subject of their responses and to answer a series of questions about viewing motives, prompts designed in the shows, online fan engagement, celebrity worship, and program commitment.

This study obtained a large amount of data due to the large audience of idol-nurturing reality shows in the Chinese market. During the questionnaire return period, a large number of respondents helped us share the study questionnaire with private fan groups. Relying on the dissemination power of fan groups, a total of 3,493 respondents completed the online questionnaire, and after eliminating those unusual cases, we obtained a total of 3,352 valid questionnaires. The demographic analysis results in this study revealed that 96.7% (N = 3,242) of the 3,352 valid samples were from females. In addition, those under the age of 20 accounted for 52.6% (N = 1,764) of the respondents, and those between the age of 21 and 30 accounted for 46.0% (N = 1,543) of the respondents. Most of the respondents watched the idol-nurturing reality shows were Youth With You two and Produce 101 China, which had been respectively, seen by 67.4% (N = 2,259) and 59.2% (N = 1,985) of the respondents.

Results

Measurement model testing

Before testing our hypotheses, we performed reliability and validity analysis on all of the items to ensure the reasonableness of the measurement model. We first employed SPSS 26.0 to conduct exploratory factor analysis (EFA), and a total of 12 factors were extracted. According to Kaiser (1974) suggestion, all factor loadings reached 0.6. Next, we used Cronbach's alpha to assess the reliability of the measured variables. As suggested by Hair et al. (1998), the Cronbach's alpha values of all factors were greater than the suggested minimum 0.70 (ability = 0.769, personality = 0.827, facial attractiveness = 0.855, social impact = 0.727, relaxation = 0.850, social interaction = 0.856, voyeurism = 0.926, high production quality = 0.816, suspense = 0.814, online fan engagement = 0.928, celebrity worship = 0.932, and program commitment = 0.906).

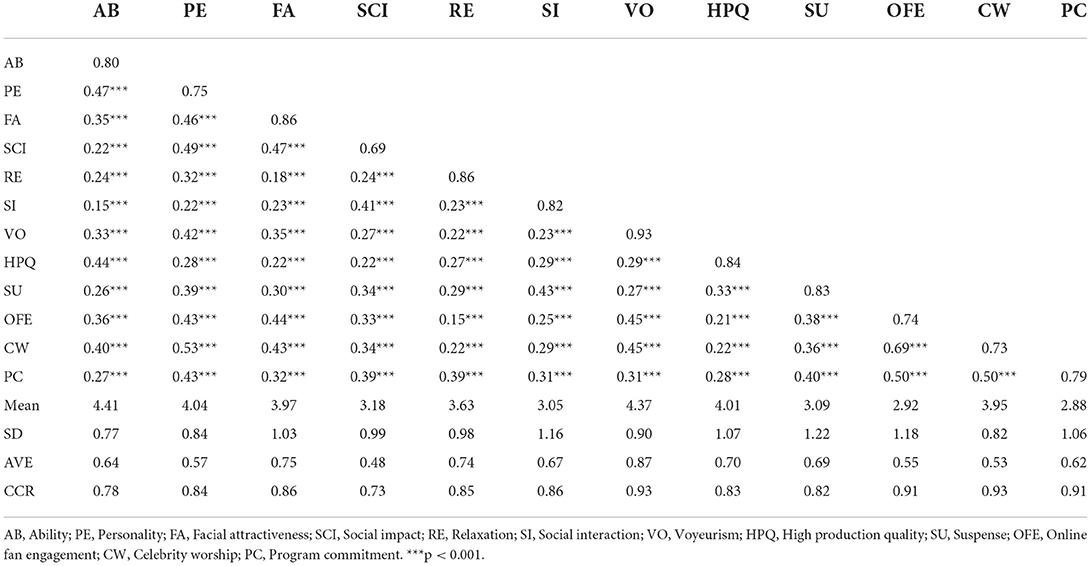

To verify the validity of the measured items, we performed confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) using SPSS AMOS 25.0. Table 1 shows the specific values of all dimensions and measurement items. Based on the suggestions made by Conway and Huffcutt (2003) and Hooper et al. (2008), the model adopted in this study has good fit indices (χ2 = 3341.643, d.f. = 967, χ2/d.f. = 3.456, p < 0.001, RMSEA = 0.027, GFI = 0.959, AGFI = 0.950, NFI = 0.967, RFI = 0.961, IFI = 0.976, TLI = 0.972, and CFI = 0.976). Hair et al. (1998) suggested that ideally, the standardized factor loadings >0.60 are acceptable. We eliminated the item “one of the main reasons that I maintain an interest in MFI is that it gives me a temporary escape from life's problems” from the measured variable celebrity worship during the CFA because its standardized factor loading did not meet the criterion. The standardized factor loadings of the remaining items were all >0.60 and significant (p < 0.001). As shown in Table 2, we examined the average of variance extracted (AVE) of the factors, among which the AVE of social impact was 0.482 and within the acceptable range (0.36<AVE<0.50). The other constructs all reached the ideal value of 0.50, thereby determining that the model had good convergent validity (Fornell and Larcker, 1981). The statistical results further indicated that the square root of the AVE of the constructs was greater than the coefficients of their correlation with the other constructs, thereby demonstrating that the model has good discriminant validity.

Research hypothesis testing

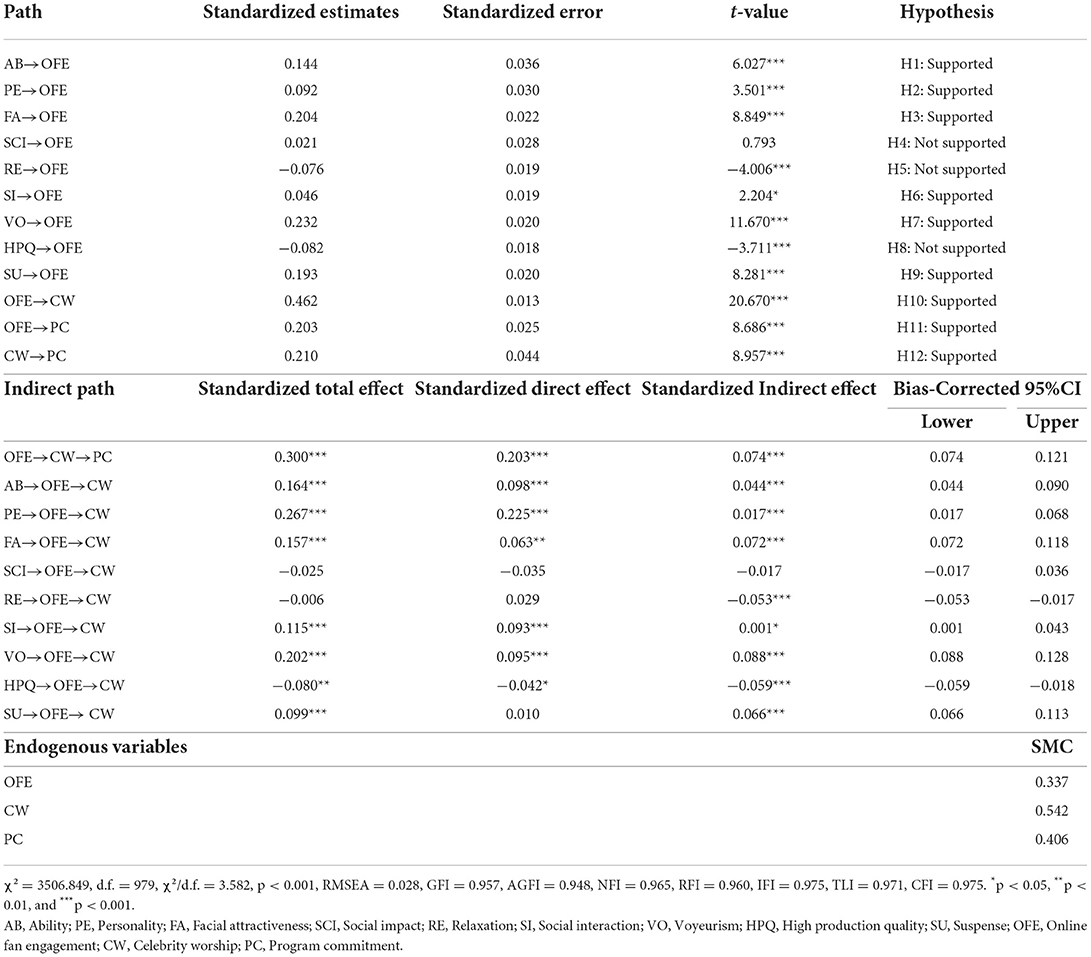

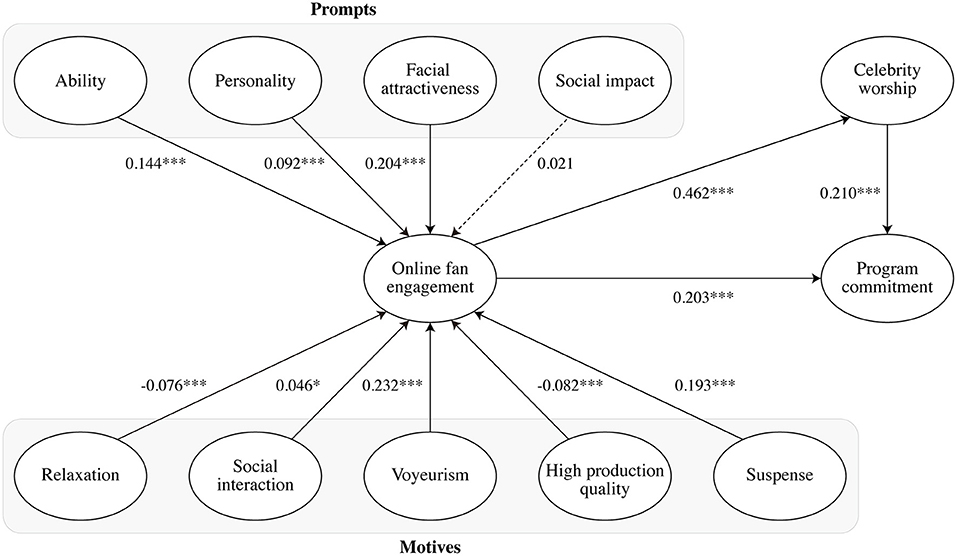

We tested our research hypotheses by using SPSS AMOS 25.0 to perform structural equation modeling. Table 3 and Figure 1 present the fit indices of the statistical model and the study results. Data analysis showed that the statistical model had good fit indices: χ2 = 3506.849, d.f. = 979, χ2/d.f. = 3.582, p < 0.001, RMSEA = 0.028, GFI = 0.957, AGFI = 0.948, NFI = 0.965, RFI = 0.960, IFI = 0.975, TLI = 0.971, CFI = 0.975. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Figure 1. Estimates of structural model. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001. Solid line: significant path; dotted line: insignificant path.

This study first examined the standardized regression coefficient between the multiple factors. Hypotheses H1–H4 predicted that prompts are positively correlated with online fan engagement. The data analysis results revealed that ability (β = 0.144, t-value = 6.027, p < 0.001), personality (β = 0.092, t-value = 3.501, p < 0.001), and facial attractiveness (β = 0.204, t-value = 8.849, p < 0.001) had a significant effect on online fan engagement and the correlations were positive. In contrast, social impact (p = 0.428) did not show any significant correlation with online fan engagement. The data analysis results support H1–H3, but the correlations between ability, personality, and online fan engagement are extremely weak.

Hypotheses H5–H9 predicted that motives are positively correlated with online fan engagement. The data analysis results revealed that relaxation (β = −0.076, t-value = −4.006, p < 0.001), social interaction (β = 0.046, t-value = 2.204, p < 0.05), voyeurism (β = 0.232, t-value = 11.670, p < 0.001), high production quality (β = −0.082, t-value = −3.711, p < 0.001), and suspense (β = 0.193, t-value = 8.281, p < 0.001) all exerted a significant effect on online fan engagement. Social interaction, voyeurism, and suspense were positively correlated with online fan engagement, whereas relaxation and high production quality were negatively correlated with online fan engagement. The data analysis results only support H6–H8. And a special note is needed that the correlations between relaxation, social interaction, high production quality, suspense, and online fan engagement are extremely poor.

Hypotheses H10–H12 predicted the correlations between online fan engagement, celebrity worship, and program commitment. The results indicated that online fan engagement exerted a significant impact on celebrity worship (β = 0.462, t-value = 20.670, p < 0.001) and program commitment (β = 0.203, t-value = 8.686, p < 0.001) and that celebrity worship also had a significant impact on program commitment (β = 0.210, t-value = 8.957, p < 0.001); all of these correlations were positive. The data analysis results support H10–H12.

Aside from answering the research questions and testing our hypotheses, we also followed the mediation analysis procedure proposed by Zhao et al. (2010) and the bootstrapping method proposed by Preacher and Hayes (2004) to analyze mediating effects. As shown in Table 3, the mediation effect was tested by analyzing the indirect effect of online fan engagement on program commitment via celebrity worship, as well as ability, personality, facial attractiveness, social impact, relaxation, social interaction, voyeurism, high production quality, and suspense on celebrity worship via online fan engagement. With a sample size of 10,000 and a 95% confidence interval, the effect of ability (β = 0.044, p < 0.001), personality (β = 0.017, p < 0.01), facial attractiveness (β = 0.072, p < 0.001), relaxation (β = −0.053, p < 0.001), social interaction (β = 0.001, p < 0.05), voyeurism (β = 0.088, p < 0.001), high production quality (β = −0.059, p < 0.001), and suspense (β = 0.0.066, p < 0.001) on celebrity worship was mediated by online fan engagement. The effect of online fan engagement (β = 0.074, p < 0.001) on program commitment was mediated by celebrity worship. But all indirect effects are extremely weak. In addition to the indirect effects, Table 3 also presents data on the direct effects and total effects.

This study conducted independent sample t-test to examine whether there were significant differences in online fan engagement and celebrity worship among respondents of different ages and genders. The results showed that gender did not have a significant effect on online fan engagement (t = 0.839, p = 0.401) and celebrity worship (t = 1.237, p = 0.216). While age had a significant effect on both online fan engagement (t = 13.926, p < 0.001) and celebrity worship (t = 10.754, p < 0.001). And the respondents under the age of 20 (MeanOFE = 3.172, MeanCW = 4.090) displayed significantly more online fan engagement and celebrity worship than the respondents between the age of 21 and 30 (MeanOFE = 2.618, MeanCW = 3.786).

Discussion and conclusions

The objective of this study was to identify a systematic link between designs of the idol-nurturing reality show, motives, and fan engagement behaviors, as well as, to examine the relationships among prompt, motive, online fan engagement, celebrity worship, and program commitment. Following data analysis, we found that the prompts ability, personality, and facial attractiveness positively correlate with online fan engagement. Although the correlation between the factors is quite weak, it still means the respondents are more likely to display online fan engagement behavior toward an idol when stimulated by the prompts ability, personality, and facial attractiveness. In contrast, no significant relationship exists between social impact and online fan engagement. This result supports the argument presented in the behavior model developed by Fogg (2009). We determined that ability, personality, and facial attractiveness are all spark-type prompts based on the Fogg Behavior Model. According to Fogg (2019), this prompt type can motivate target users to a certain extent when they lack motive and can promote the target behavior. In contrast, social impact is a signal-type prompt, which is only effective when the ability and motive of the target users reach a certain level. Signals merely serve as a reminder and cannot induce people to exhibit the target behavior. As mentioned previously, various types of fan works, recommendations among friends, popular information on social platforms, and various forms of online and offline advertisements are all signals. Fogg (2009) specifically mentioned that the effects of prompts are becoming increasingly important with today's social background. Future idol-nurturing reality shows might consider increasing the number of prompts that can display the ability, personality, and facial attractiveness of trainees, which might be beneficial in motivating viewers' online fan engagement.

Literature indicates that a considerable difference exists between ritualistic and instrumental viewing behavior (Rubin, 1984). Audiences who watch shows because of ritualistic motives are less engaged in the shows and less active in their viewing activities (Rubin, 1984). Instrumental motives imply selectivity, intentionality, and involvement in media consumers, which induce more purposeful and goal-oriented behavior, whereas ritualistic usage focuses on the media rather than the content. Ritualistic viewers believe that the form of the media is much more critical (Conway and Rubin, 1991). Relaxation and high production quality are ritualistic motives, while social interaction, voyeurism, and suspense are instrumental motives. After further analyzing the relationship between motives and online fan engagement, we found that social interaction, voyeurism, and suspense were significantly and positively correlated with online fan engagement and that relaxation and high production quality were significantly and negatively correlated with online fan engagement, which supports the viewpoint proposed by Rubin (1984).

Lin et al. (2016) found that the more social television activities audiences engage in, the greater their satisfaction and involvement in the show are (Lin et al., 2016). Similarly, our research data indicate that online fan engagement and celebrity worship are significantly and positively correlated with program commitment. This implies that audiences participating in more online fan engagement activities may present higher levels of celebrity worship and commitment to the show. Furthermore, our data show that online fan engagement mediates the relationships between motives and celebrity worship and between prompts and celebrity worship. In the context of idol-nurturing reality shows, online fan engagement exerts a positive impact on the attitudes that audiences form toward the show and the trainees.

Our data show that celebrity worship significantly and positively correlates with program commitment and mediates the relationship between online fan engagement and program commitment. The results may mean that in the context of idol-nurturing reality shows, trainees may also contribute to affecting the success of the shows. Singh and Banerjee (2019) demonstrated that celebrity worshipers hold positive attitudes toward advertisements containing their celebrities and that this further influences their purchase intention. Chen et al. (2022) expressed in the article that cooperating with celebrities is a suitable marketing method. Research in the field of brand endorsement suggested that fans are likely to transfer their emotional attachment to the celebrities to the brands, and celebrity worship helps build consumer loyalty to the brand. Attachment to celebrities also tends to provoke impulsive buying behavior among fans (Chen et al., 2021), which is very common in idol-nurturing reality shows. These results build on the alignment of celebrity and brand personality (Pradhan et al., 2016). It just so happens that there is a symbiotic relationship between the shows and idols in idol-nurturing reality shows. On the other hand celebrity attractiveness has the greatest effect on human brand attachment (Huang et al., 2015) and consumer relatedness need satisfaction (Gilal et al., 2020). This means that the more attractive the trainees in an idol-nurturing reality show, the more likely viewers will become committed to the show. As suggested by Zhuang (2019), the idol-nurturing reality shows must help idols continuously improve their attractiveness and take fan suggestions seriously in order to build a good impression of the show among viewers.

Today, non-pathological celebrity worship is common among fans, and a greater variety and forms of fan engagement exist, which brings up issues related to psychology and behavior (Zhang and Negus, 2020; McCutcheon and Aruguete, 2021). Data fandom is a form of fan engagement that has developed alongside digital technology and social media (Zhang and Negus, 2020). However, a common criticism by many people is that data fandom also brings problems. For instance, the shows and the cooperating brands have formulated the rules of the shows, requiring fans to purchase designated beverages in exchange for votes. Under the control of the idol stars' companies and fan groups' managers, the fans pay more money, time, and emotion to help idols gain more votes, which causes wasteful behavior. Chen (2021) mentioned a similar concern: consumption-oriented celebrity worship in China leads to wasteful behavior. This study found that respondents under the age of 20 showed higher online fan engagement and celebrity worship, which is particularly important for these young fans' psychological and behavioral guidance. For the shows, idols, and fan organizations, increasing active online fan engagement may increase program commitment and celebrity worship; however, it is more important to guide fans so that online fan engagement is undertaken correctly.

This study is not without limitations. First, this study was cross-sectional with a sample size of 3,352, and our respondents were young Chinese idol-nurturing reality show viewers. Therefore, the results of this study cannot be generalized to the entire audience of idol-nurturing reality shows. The results of this study were somewhat limited and not representative of a wide range of audiences. Second, although a random sample was used to obtain the data, the results show that the distribution of respondents in this study was uneven in terms of gender, with a tiny sample size of males. In 2018, the Celebrity Consumption Impact Report (CBNData, 2018) showed that females accounted for 72.3% of the audience of Idol Producer, which aimed to produce a male idol group, and that females also occupied 65.7% of the audience of Produce 101 China, which aimed to produce a female idol group. It seemed that the audiences of the idol-nurturing reality shows tended to be female. It was more difficult to obtain samples from male fans, leading to a vast difference in gender distribution and making it difficult to investigate the influence of gender differences in future research. The vast majority of the subjects in this study were female, but the psychology and behavior of male viewers in idol-nurturing reality shows is also a topic of interest. Therefore, we suggest that future studies consider males as the subject of the study to understand their fan engagement behaviors and celebrity worship phenomenon. Regarding the research subjects, we selected 11 idol-nurturing reality shows in China, Japan, and South Korea. Despite their concepts and competition systems being similar to those of Produce 101 released by Korean television channel Mnet, differences still exist among the designs of the shows. Furthermore, our questionnaire recovery period coincided with the run of Youth With You 2, so the responses of the respondents might have differed if the questionnaire had been conducted at a different time. During the process of this study, we found that a cultural divide led to some Chinese viewers preferring idol-nurturing reality shows produced in their home country. From our data, we also found that nearly 1/3 of the respondents had never exhibited idol engagement before watching idol-nurturing reality shows; therefore, further comparisons could be made between audiences who were already fans and those who were getting involved in the idol industry for the first time.

With the increase of the fan base, the influence of Chinese idols and their fans is expanding to other popular media industries, such as mobile games. Owing to the apparent intention that game designers showed to attract idol fans to become new users, studying the online engagement behaviors of idol fans makes a profound impact on the traditional television industry and provides essential advice on other sectors. As mentioned before, the rules formulated by the show have caused excessive fan engagement behaviors and many social problems. For researchers, discovering the hidden dangers caused by fan engagement behaviors and finding a balance between commercial interests and correct social values may also be an essential research point.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Research Ethics Committee, National Taiwan University. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants' legal guardian/next of kin.

Author contributions

Y-TH and A-DG conceptualized and designed the study. A-DG collected and analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. Y-TH provided guidance and revised the paper. Both authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research project was supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology of Taiwan (grant number: MOST 110-2410-H-027-021-SSS).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the two reviewers for their valuable comments, as well as all the participants in this study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors, and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcomm.2022.931185/full#supplementary-material

References

Anderson, E., and Weitz, B. (1992). The use of pledges to build and sustain commitment in distribution channels. J. Market. Res. 29, 18–34. doi: 10.1177/002224379202900103

Bantz, C. R. (1982). Exploring uses and gratifications: a comparison of reported uses of television and reported uses of favorite program type. Communic. Res. 9, 352–379. doi: 10.1177/009365082009003002

Brooks, S. K. (2021). FANatics: systematic literature review of factors associated with celebrity worship, and suggested directions for future research. Curr. Psychol. 40, 864–886. doi: 10.1007/s12144-018-9978-4

Brown, W. J. (2015). Examining four processes of audience involvement with media personae: transportation, parasocial interaction, identification, and worship. Commun. Theory 25, 259–283. doi: 10.1111/comt.12053

CBNData (2018). Celebrity Consumption Impact Report [Online]. Available online at: https://cbndata.com/home (accessed February, 2019).

Chen, L., Chen, G., Ma, S., and Wang, S. (2022). Idol worship: how does it influence fan consumers' brand loyalty? Front. Psychol. 13:850670. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.850670

Chen, T. Y., Yeh, T. L., and Lee, F. Y. (2021). The impact of Internet celebrity characteristics on followers' impulse purchase behavior: the mediation of attachment and parasocial interaction. J. Res. Interact. Market. 15, 483–501. doi: 10.1108/JRIM-09-2020-0183

Chen, X. (2021). “Consumption oriented idol worship in China”, in 2021 4th International Conference on Humanities Education and Social Sciences (ICHESS 2021). Atlantis Press, 1012–1016. doi: 10.2991/assehr.k.211220.173

Conway, J. C., and Rubin, A. M. (1991). Psychological predictors of television viewing motivation. Communic. Res. 18, 443–463. doi: 10.1177/009365091018004001

Conway, J. M., and Huffcutt, A. I. (2003). A review and evaluation of exploratory factor analysis practices in organizational research. Organ. Res. Methods 6, 147–168. doi: 10.1177/1094428103251541

Ebersole, S., and Woods, R. (2007). Motivations for viewing reality television: a uses and gratifications analysis. Southwest. Mass Commun. J. 23, 23–42.

Fogg, B. (2009). “A behavior model for persuasive design,” in Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Persuasive Technology. Claremont, CA: Association for Computing Machinery. doi: 10.1145/1541948.1541999

Fogg, B. (2019). Tiny Habits: The Small Changes That Change Everything. New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Fornell, C., and Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Market. Res. 18, 39–50. doi: 10.1177/002224378101800104

Fraade-Blanar, Z., and Glazer, A. (2017). Superfandom: How Our Obsessions are Changing What We Buy and Who We Are. New York, NY: W. W. Norton Company.

Fuhr, M. (2015). Globalization and Popular Music in South Korea: Sounding Out K-Pop. NewYork, NY: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781315733081

Gilal, F. G., Paul, J., Gilal, N. G., and Gilal, R. G. (2020). Celebrity endorsement and brand passion among air travelers: theory and evidence. Int. J. Hosp. Manage. 85:102347. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2019.102347

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., Anderson, R. E., and Tatham, R. L. (1998). Multivariate Data Analysis. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

He, X. (2006). Survey report on idol worship among children and young people. Chin. Educ. Soc. 39, 84–103. doi: 10.2753/CED1061-1932390107

Hill, A. (2005). Reality TV: Audiences and Popular Factual Television, 1st Edn. London: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780203337158

Hooper, D., Coughlan, J., and Mullen, M. (2008). Structural equation modelling: guidelines for determining model fit. Electron. J. Bus. Res. Methods 6, 53–60. doi: 10.21427/D7CF7R

Hou, M. (2018). Social media celebrity and the institutionalization of YouTube. Convergence 25, 534–553. doi: 10.1177/1354856517750368

Huang, Y.-A., Lin, C., and Phau, I. (2015). Idol attachment and human brand loyalty. Eur. J. Mark. 49, 1234–1255. doi: 10.1108/EJM-07-2012-0416

Jenkins, H. (2012). Textual Poachers: Television Fans and Participatory Culture. New York, NY: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780203114339

Jenkins, H., Ito, M., and boyd, d. (2015). Participatory Culture in a Networked Era: A Conversation on Youth, Learning, Commerce, and Politics. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Jing, C. (2018). Produce 101 Begins a Wave of Interest in Chinese Idol Groups [Online]. Available online at: https://pandaily.com/produce-101-begins-a-wave-of-interest-in-chinese-idol-groups/ (accessed July, 2018).

Kaiser, H. F. (1974). An index of factorial simplicity. Psychometrika 39, 31–36. doi: 10.1007/BF02291575

Kamins, M. A., Brand, M. J., Hoeke, S. A., and Moe, J. C. (1989). Two-Sided versus one-sided celebrity endorsements: the impact on advertising effectiveness and credibility. J. Advert. 18, 4–10. doi: 10.1080/00913367.1989.10673146

Lin, J.-S., Chen, K.-J., and Sung, Y. (2018). Understanding the nature, uses, and gratifications of social television: implications for developing viewer engagement and network loyalty. J. Broadcast. Electron. Media 62, 1–20. doi: 10.1080/08838151.2017.1402904

Lin, J.-S., Sung, Y., and Chen, K.-J. (2016). Social television: examining the antecedents and consequences of connected TV viewing. Comput. Human Behav. 58, 171–178. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2015.12.025

Lin, Y.-H., and Chu, M. G. (2021). Online communication self-disclosure and intimacy development on Facebook: the perspective of uses and gratifications theory. Online Info. Rev. 45, 1167–1187. doi: 10.1108/OIR-08-2020-0329

Lowenthal, L. (2017). “e Triumph of mass idols,” in Literature and Mass Culture. NewYork, NY: Routledge, 225–260. doi: 10.4324/9780203787083

Madan, S. K., and Kapoor, P. S. (2022). “Study of consumer brand following intention on Instagram: applying the uses and gratification theory,” in Research Anthology on Social Media Advertising and Building Consumer Relationships. Hershey, PA: IGI Global, 1964–1986. doi: 10.4018/978-1-6684-6287-4.ch104

Maltby, J., Day, L., McCutcheon, L. E., Houran, J., and Ashe, D. (2006). Extreme celebrity worship, fantasy proneness and dissociation: developing the measurement and understanding of celebrity worship within a clinical personality context. Pers. Individ. Dif. 40, 273–283. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2005.07.004

McCutcheon, L., Aruguete, M. S., Jenkins, W., McCarley, N., and Yockey, R. (2016). An Investigation of demographic correlates of the celebrity attitude scale. Interperson. Int. J. Pers. Relat. 10, 161–170. doi: 10.5964/ijpr.v10i2.218

McCutcheon, L. E., and Aruguete, M. S. (2021). Is celebrity worship increasing over time? J. Stud. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 7, 66–75.

McCutcheon, L. E., Lange, R., and Houran, J. (2002). Conceptualization and measurement of celebrity worship. Br. J. Psychol. 93, 67–87. doi: 10.1348/000712602162454

Menon, D. (2022). Purchase and continuation intentions of over -the -top (OTT) video streaming platform subscriptions: a uses and gratification theory perspective. Telemat. Inform. Rep. 5:100006. doi: 10.1016/j.teler.2022.100006

Mukherjee, D. (2009). Impact of celebrity endorsements on brand image. Indian J. Mark. 42. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.1444814

My-Trinh, B., and Huong-Linh, L. (2021). “Loyalty to digital celebrity: roles of emotional engagement, cosmopolitanism, and self esteem,” in International Conference on Emerging Challenges: Business Transformation and Circular Economy (ICECH 2021). Atlantis Press, 415–423.

Palmgreen, P., Wenner, L. A., and Rayburn, J. D. (1980). Relations between gratifications sought and obtained: a study of television news. Commun. Res. 7, 161–192. doi: 10.1177/009365028000700202

Papacharissi, Z., and Mendelson, A. L. (2007). An exploratory study of reality appeal: uses and gratifications of reality TV shows. J. Broadcast. Electron. Media 51, 355–370. doi: 10.1080/08838150701307152

Park, B. (2019). ‘Produce' Idol Audition Program Emerges As Most Promising Platform For Debuts Today Yonhap News Agency [Online]. Available online at: https://en.yna.co.kr/view/AEN20190605009100315 (accessed June 5, 2019).

Parmar, Y., and Mann, B. J. S. (2020). Exploring the relationship between celebrity worship and brand equity: the mediating role of self-brand connection. J. Creat. Commun. 16, 61–80. doi: 10.1177/0973258620968963

Peng, W.-b., Qui, X.-t., Liu, D.-z., and Wang, P. (2010). Revision of the scale of celebrity worship. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 26, 543–548.

Pradhan, D., Duraipandian, I., and Sethi, D. (2016). Celebrity endorsement: how celebrity–brand–user personality congruence affects brand attitude and purchase intention. J. Market. Commun. 22, 456–473. doi: 10.1080/13527266.2014.914561

Preacher, K. J., and Hayes, A. F. (2004). SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behav. Res. Meth. Instrum. Comput. 36, 717–731. doi: 10.3758/BF03206553

Reeves, R. A., Baker, G. A., and Truluck, C. S. (2012). Celebrity worship, materialism, compulsive buying, and the empty self. Psychol. Market. 29, 674–679. doi: 10.1002/mar.20553

Rubin, A. M. (1984). Ritualized and instrumental television viewing. J. Commun. 34, 67–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.1984.tb02174.x

Rubin, A. M., and Perse, E. M. (1987). Audience activity and soap opera involvement a uses and effects investigation. Hum. Commun. Res. 14, 246–268. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2958.1987.tb00129.x

Rusbult, C. E. (1983). A longitudinal test of the investment model: the development (and deterioration) of satisfaction and commitment in heterosexual involvements. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 45, 101–117. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.45.1.101

Rusbult, C. E., Agnew, C., and Arriaga, X. (2011). The Investment Model of Commitment Processes. Department of Psychological Sciences Faculty Publications. Paper 26. Available online at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/psychpubs/26

Rusbult, C. E., and Buunk, B. P. (1993). Commitment processes in close relationships: an interdependence analysis. J. Soc. Pers. Relat. 10, 175–204. doi: 10.1177/026540759301000202

Singh, R. P., and Banerjee, N. (2019). Exploring the influence of celebrity worship on brand attitude, advertisement attitude, and purchase intention. J. Promot. Manage. 25, 225–251. doi: 10.1080/10496491.2018.1443311

Sung, Y., and Choi, S. M. (2010). “I won't leave you although you disappoint me”: the interplay between satisfaction, investment, and alternatives in determining consumer–brand relationship commitment. Psychol. Market. 27, 1050–1073. doi: 10.1002/mar.20373

Van Lange, P. A., Rusbult, C. E., Drigotas, S. M., Arriaga, X. B., Witcher, B. S., and Cox, C. L. (1997). Willingness to sacrifice in close relationships. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 72:1373. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.72.6.1373

Xia, F. (2018). Exploring the features and development direction of the idol-nurturing reality show model with the Korean show produce 101 series as an example. Radio TV J. 11, 23–24. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1674-246X.2018.11.010

Xu, D., and Guo, L. (2018). Use and gratifications of singing competition reality shows: linking narcissism and gratifications sought with the multimedia viewing of Chinese audiences. Mass Commun. Soc. 21, 198–224. doi: 10.1080/15205436.2017.1404616

Xu, X. (2017). Contemplating the Industry Model of Idol-nurturing Reality Shows with the Korean Show Produce 101 as an Example. Available online at: http://media.people.com.cn/n1/2017/0831/c414067-29507052.html (accessed August, 2017).

Yoon, K. (2018). Global imagination of K-Pop: pop music fans' lived experiences of cultural hybridity. Popular Music and Society 41, 373–389. doi: 10.1080/03007766.2017.1292819

Yu, L., and Nam, Y. (2018). Narrative analysis of < Produce 101> season2: based on the competition and training. J. Korea Contents Assoc. 18, 503–518. doi: 10.5392/JKCA.2018.18.07.503

Yue, X., and Cheung, C.-K. (2018). Idol Worship in Chinese Society: A Psychological Approach. London: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781315223124

Zhang, Q., and Negus, K. (2020). East Asian pop music idol production and the emergence of data fandom in China. Int. J. Cult. Stud. 23, 493–511. doi: 10.1177/1367877920904064

Zhao, C. (2019). A study on the idolatry of contemporary youth. J. Chin. Youth Soc. Sci. 6, 117–122.

Zhao, X. (2014). Gratifications About Reality Television “The Voice of China” among Chinese Audience. Unpublished Master's Thesis, Bangkok University, Bangkok, Thailand.

Zhao, X., Lynch, J. G. Jr, and Chen, Q. (2010). Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: myths and truths about mediation analysis. J. Consum. Res. 37, 197–206. doi: 10.1086/651257

Zhuang, L. (2019). “The influences of idol effect on the purchasing decisions of their fans,” in 2018 International Symposium on Social Science and Management Innovation (SSMI 2018) (Atlantis Press), 164–171.

Zsila, Á., McCutcheon, L. E., and Demetrovics, Z. (2018). The association of celebrity worship with problematic Internet use, maladaptive daydreaming, and desire for fame. J. Behav. Addict. 7, 654–664. doi: 10.1556/2006.7.2018.76

Keywords: idol-nurturing reality show, celebrity worship, online fan engagement, program commitment, uses and gratifications theory

Citation: Gong A-D and Huang Y-T (2022) When young female fans were producing celebrities: The influential factors related to online fan engagement, celebrity worship, and program commitment in idol-nurturing reality shows. Front. Commun. 7:931185. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2022.931185

Received: 28 April 2022; Accepted: 25 August 2022;

Published: 20 September 2022.

Edited by:

Juana Du, Royal Roads University, CanadaReviewed by:

Ágnes Zsila, Pázmány Péter Catholic University, HungaryYongning Wu, China National Center for Food Safety Risk Assessment, China

Copyright © 2022 Gong and Huang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yi-Ting Huang, eXRodWFuZ0BtYWlsLm50dXQuZWR1LnR3

An-Di Gong

An-Di Gong Yi-Ting Huang

Yi-Ting Huang