- Faculty of Economics and Administrative Sciences, Cyprus International University, Lefkosa, Turkey

A good deal of evidence indicates that servant leadership play a critical role in employees' job outcomes. However, research studies on the variables that could mediate the effect of servant leadership in determining this relationship are relatively few. Utilizing the framework of leader-member exchange and social exchange theories, this study examines the mediating effect of “trust in coworkers” in the effect of “servant leadership” on employee job outcomes. Survey data were sourced from 315 bank employees and managers in Northern Cyprus. Partial least square structural equation modeling was utilized with the aid of WarpPLS (7.0) to test the study hypotheses. Servant leadership was found to have a direct and indirect relationship with employees' career satisfaction, service recovery performance, and innovative work behavior. In contrast, the servant leadership relationship with job satisfaction was indirect. In addition, trust in coworkers was found to be a mediator in the relationship between servant leadership and employees' job outcomes. The theoretical and practical implications of this study were highlighted.

Introduction

For over two decades, the attention of both academics and professionals has been on the sustainability of organizational performance. This is partly due to the increasingly dynamic and competitive global market. To this aim, organizations seek multiple ways to gain a sustainable advantage (Wikström, 2010) and search for innovative ways to stimulate positive employee outcomes (De Jong and Den Hartog, 2010). This requires a leadership style to develop a conducive working environment where employees can develop their skills and knowledge (Edgar et al., 2017), feel comfortable (Karatepe and Aga, 2016), and build trust among themselves (Lau and Liden, 2008). To this aim, Servant Leadership (SL) which is a shift from the conventional “transformational leadership model,” is directed to the shared and relational views so that the relations exchange between leader and followers are the focus (Avolio et al., 2009). SL focuses on humbleness, legitimacy, and social acceptance, none of which are specific elements of transformational leadership (van Dierendonck, 2011). SL, as an emerging type of leadership, affects the job outcomes in service firms such as banks (Karatepe et al., 2019), airlines (Ilkhanizadeh and Karatepe, 2018), and the hospitality industry (Babakus et al., 2011). Given the importance of leadership, the current study aims to investigate the process through which SL influences employee job outcomes. In addition, it is essential to underscore the mediating role that connects SL to employee job outcomes, specifically to job satisfaction (JS), career satisfaction (CS), service recovery performance (SRP), and innovative work behavior (IWB). The other question is the potential mediating variables between SL and job outcomes. The current study aims to see if trust in coworkers (TCW) could have a mediating role.

The need for trust in the workplace is a crucial building element of any organization which can create or break a company's culture. Trust could be defined in the relationship between leadership and employees, employees and superiors, and among coworkers. SL is a significant antecedent of “trust” (Eva et al., 2019), and Aas the servant leader focuses on strengthening the relationship with the employees, such a style could provoke higher TCW. Trust resulting from SL produces an emotional response in stronger emotional connections and feelings of obligation (Miao et al., 2014). In turn, the employee tries to respond by demonstrating positive attitudes and TCW. Therefore, SL as a product of leader and organizational trust could build trust relationships at the “Bottom of the Pyramid” among coworkers (Greenleaf, 2014). In addition, the interdependent nature of job tasks and the prevalence of teamwork require employees to trust each other (Lau and Liden, 2008). However, studies on SL and trust mainly investigate the trust in a leader with scant literature on TCW (Ferres et al., 2004; Parker et al., 2006; Lau and Liden, 2008).

The current study contributes to the body of knowledge by employing the “Leader-Member Exchange theory” (LMX) (Liden and Maslyn, 1998) to investigate the effect of SL on employee job outcomes. In addition, Social Exchange Theory (SET) (Blau, 1964) is employed to examine perceived TCW as a possible mediator through which SL affects job outcomes.

Literature Review and Hypotheses

Theoretical Focus

The LMX theory is believed to be distinct among leadership theories, owing to its focus on the dyadic relationships between leaders and followers (Liden and Maslyn, 1998). LMX argues that leaders develop different exchange relationships with their followers. However, it is silent concerning the proposition of individual healing, the followers' development, and the motivation of leaders' service to society (Chinomona et al., 2013). Similarly, SL attitudes influence the development and sustenance of significant interpersonal nexus between leaders and followers. However, SL assists the workers in attaining their fullest potential and becoming self-motivated (Chinomona et al., 2013). Leaders are fostering these critical behaviors by developing a social exchange nexus with their followers instead of relying solely on the economic benefits from the employment agreement or the authority entrusted to them. Some studies suggest that positive organizational and individual job outcomes are the primary outcomes of effective LMX relationships (Graen, 2004). These outcomes are high-performance rating, improved organizational performance, job satisfaction, better objective performance, organizational commitment, decreased turnover intentions, and organizational citizenship behavior (Schriesheim et al., 1999). Therefore, this study contends that SL with a strong interpersonal relationship with their employees will be committed to organizational performance and positive outcomes.

SET is a theory to describe the social exchange nexus among groups in the setting of human interaction (Ji and Jan, 2020). This theory is often used to interpret the social exchange link between employer and employee. According to Emerson (1976), the interaction of employer and employee produces obligations in the context of social exchange and interdependence on the action of the counterparts (Blau, 1964). Cropanzano and Mitchell (2005) state that a social exchange happens when management treats workers well. In turn, the employee reciprocates the gesture with a positive work attitude and behaviors, but unfavorable outcomes are likely to occur if it is the other way round. For instance, since trust is one of the requirements for social exchange to reciprocate, the challenge is for the workers to prove their trustworthiness. This indicates that trust is a significant factor in establishing social exchange (Chen et al., 2005). According to Colquitt et al. (2014), it determines a social exchange relationship. In addition, according to Mayer et al. (1995), trust reflects a person's confidence in the form of consistency, objectivity, promise fulfillment, and reliability. Thus, there will be trusting and loyal relations between both parties and among the coworkers owing to the significance of trust in the process of social exchange. In other words, the workers' favorable disposition to trust in the organization and TCW contributes to effective management in an organization (Nedkovski et al., 2017). This position validates the Colquitt et al. (2014) view that “employees who gain from the acts of their manager feel obligated to reciprocate in the form of positive outcomes”. Because of these, we contend that TCW will mediate the relationship between SL and positive employee job outcomes.

SL and Job Outcomes

According to Greenleaf (2002), SL is the genuine feeling that an individual is willing to help others. It pursues to improve those who fulfill others' needs and advocates a group-oriented attitude to decision-making to improve organizations and society. Since the introduction of the term, several studies have demonstrated its influence on employees' performance and commitment (Sokol, 2014; Khattak and O'Connor, 2020) and organizational citizenship behavior (OCB) (Ozyilmaz and Cicek, 2015; Newman et al., 2017). According to Liden et al. (2014), SL is expected to positively impact the task performance of their employees and OCBs because it models such traits to their employees and, consequently, fosters a “servant culture”. About LMX theory, leadership is expected to promote followers' development and assist them in exhibiting their full potential (Chinomona et al., 2013). It can influence their psychological states (e.g., JS). In addition, theory suggests that managers who focus on employees' personal growth can enhance the possibility of the employee having a meaningful work experience (Chiniara and Bentein, 2016). In line with this, Barbuto and Wheeler (2006) demonstrate a relationship between SL and “in-role performance” and “organizational commitment”, even when another style of leadership was controlled for (Bass, 2000).

A recent meta-analysis study by Hoch et al. (2018) investigates the impact of three positive leadership styles (authentic, servant, and ethical leadership) in comparison to “transformational leadership” and found that about 9 and 15% explanation variations in OCB and organizational commitment, respectively, to be by servant leadership. Consequently, the study concluded that SL exhibits conceptual and empirical uniqueness from TL. This finding was confirmed by Lee et al. (2020), who revealed that SL influences several individuals and “team-level” outcomes such as “creativity,” “task performance”, OCB, “counterproductive performance”, and “voice”. Moreover, “trust” is established as a mediator in the nexus between SL and OCB on the one hand and organizational commitment on the other hand. JS is believed to affect the job situation (Bhal and Ansari, 2007). It is in line with the findings of Graen (2004) that employees with a servant leader receive not just rewards of better performance rating and career advancement. They also have more satisfaction in terms of sovereignty and complex tasks.

Liden et al. (2014) suggest that a leader must encourage followers' autonomy, motivate them to think autonomously, and take responsibility for their progress in the future. Hence, SL assists their followers in developing and succeeding. Moreover, SL emphasizes a valid concern for the employees' “career growth and improvement” by giving essential resources, mentoring, and chances. This is consistent with the LMX theory that suggests an effective relationship between the leaders and subordinates will foster self-motivation for the employee and result in career progression (Chinomona et al., 2013).

Moreover, the followers are empowered by motivating and facilitating their capability to handle duties, accept challenges, and decide when and in what way to ensure job tasks (Liden et al., 2008). Notably, Ehrhart (2004) observed that servant leaders would like their followers to develop and view subordinates' progress as an end, not simply a way to achieve the leader's or organization's objectives. Thus, subordinates who get resources and support from their leaders are more careful about their development and accrue more skills (Eby et al., 2003). This implies that they are value-added to the company, more competitive, and maybe more satisfied with achieving their career goals. A recent study by Wang et al. (2019) found servant leaders' positive and significant influence on CS. The current study argues that SL may result in high opportunities for success and a high level of career satisfaction.

SRP is a significant outcome of frontline service jobs (Wirtz and Jerger, 2016). According to Karatepe et al. (2019), the employees' creativity often contacts customers, and their service recovery performances require “extra-role behavior,” which contributes significantly to organizational performance. This is in line with Ashill et al. (2008). They observed that an organization's approach to service recovery is one of several significant issues in effective customer and employee satisfaction through service quality. SRP, accordingly, is described by Ruyter and Wetzels (2000) as “doing things very right the second time”, and according to Lewis and Spyrakopoulos (2001) as “the actions that a service provider takes to respond to service failures”. The SRP is when the service provider does not wait for the complaint to be lodged before rectifying the error once it is identified. It is highly unavoidable in a service-providing industry for a service failure not to occur (Daskin and Yilmaz, 2015). Since service failure is inevitable in a service industry, the performance of employees at the frontline in dealing with service failure is believed to be a critical strategic matter in the banking management literature (Karatepe et al., 2019). Podsakoff et al. (1996) established a connection between transformational leadership and “improved team performance”. Echunha et al. (2009) demonstrate that leadership style significantly influences SRP and concluded that prompt and decisive action is required. A similar result was found by Lin (2011), where it was established that transformational leadership positively impacts the SRP procedure. This finding was corroborated by Punjaisri et al. (2013), who found a similar result. Moreover, in a recent study by Daskin (2016), transformational leadership significantly influenced service recovery performance in the hospitality industry.

Moreover, IWB is believed to be a multi-stage process that involves production, promotion, and realization of the new stage, with every stage demanding unique actions and individuals' behavior (Shalley and Zhou, 2008). Some extant literature demonstrates the connection between SL and employee IWB. For instance, the study of Panaccio et al. (2015) contend that owing to the focus of servant leaders on their employees' need instead of their selfish interest, their behavior increases their followers' psychological contract fulfillment and thus motivate innovation. Opoku et al. (2019) stressed that such leaders connect with their workers beyond the economic exchange. As a result of SL's excellent intentions, the workers are often reciprocated by putting more effort needed for realizing new ideas (Yoshida et al., 2014). This is similar to White and Lean (2008), who suggest that a good leader creates a positive working environment that would make followers feel psychologically safe. Malik et al. (2015) state that such a conducive working environment inspires employees to find innovative means of accomplishing a task, which drives creativity. This position was demonstrated in the study of Peng and Wei (2018), who found that the leader's integrity has a trickle-down impact on employees' creative ability, and corroborated by Opoku et al. (2019), who empirically confirmed SL as a determinant of employee IWB.

SL and Trust in Coworkers

Most studies have often used SET to explain the positive influence of SL on followers' behavior (Eva et al., 2019; Khattak and O'Connor, 2020). Owing to followers' interests placed above their selfish interests by servant leaders, there is a possibility of developing a strong relationship between leaders, subordinates, and coworkers. Blau (1964) observed that in the case of robust social exchange relationships, both parties expect and trust that their positive behavior will be returned. Moreover, according to Whitener et al. (1998), the leaders who are more concerned about the workers tend to provide opportunities to the workers to express their concerns, which assists the followers in developing trust in their leaders and among themselves. It is believed that servant leaders exert influence on the practical development of “trust climate,” which, according to Ling et al. (2017), has been demonstrated as a factor that influences the quality of exchange relations and stimulates positive outcomes at the workplace.

By avoiding adverse interpersonal disputes and cultivating a sense of community, the SL style focuses on the well-being of employees (Schaubroeck et al., 2011). Because the SL's primary goal is to deepen the link with employees, this leadership style generates higher levels of trust among coworkers (Saleem et al., 2020). Behaviors associated with SL, including emotional support, increasing problem-solving abilities, task expertise, empowering others, putting others first, and acting ethically, are widely regarded as critical under challenging situations (Bechky and Okhuysen, 2011). As a result, these behaviors within the team are likely to affect trust in a coworker. Saleem et al. (2020) suggest that SL generates trust in coworkers more effectively. They conclude that trust mediates the relationship between SL and organizational citizenship behaviors and subordinate performance.

It is believed that a leader can form employees' perceptions about ethics (McCann and Holt, 2009). As followers reciprocate their leaders' actions, servant leaders' values of integrity are passed to employees and possibly alter how they eventually cooperate with others (Lytle and Timmerman, 2006). Likewise, leadership behaviors predict coworkers' interpersonal trust (Jung and Avolio, 2000).

From another aspect, the outcomes of SL, such as perceptions of integrity (Jaramillo et al., 2009) or benevolence (Mujeeb et al., 2021), could foresee the trust in coworkers. In other words, perceiving that a coworker has high integrity or benevolence might indicate trustworthiness (Dirks and Skarlicki, 2009). Wintrobe and Breton (1986) state a potential correlation between trust among the manager and personnel and trust in coworkers. They claim that when employees do not trust their management, they band together for collective action. Nevertheless, we understand that the opposite may similarly be correct. Once employees recognize the leadership to be reliable, they trust their colleagues. Therefore, SL may affect the relationship between coworkers.

Russell (2001) claimed that the values of servant leaders generate obvious attributes and play a crucial role in creating trust in coworkers and in an organization that holds servant-led organizations together. SL builds trust between the manager and employee and between coworkers (Spears, 2004) and possibly will cause new levels of shared trust and interdependency in organizations (McGee-Cooper, 1998). In addition, the impact of SL on corporate culture is validated (Giampetro-Meyer et al., 1998). Finally, Chatbury et al. (2011) indicate a relationship between SL and trust in coworkers and point out that SL could improve trust between them. Hence, we hypothesize that SL will positively influence TCW.

TCW as a Mediator

The study of Dirks and Ferrin (2001) highlights two types of trust: performance outcomes and workplace behaviors, workplace attitudes, and cognitive constructs. Davis et al. (2000) and Culbert and McDonough (1986) explain the performance outcome and workplace behavior, including sharing information and communication, OCBs, negotiation behavior, individual workers' performance, and unit performance. An example of workplace attitude and cognitive constructs, according to McAllister (1995), is JS and low turnover intentions (Davis et al., 2000). In addition, some studies have investigated trust as an antecedent of employee performance within the theoretical framework of SET (Ellickson, 2002); satisfaction (Harrison et al., 2006); employee turnover intention, absenteeism (Karatepe et al., 2019), and commitment (Cho and Park, 2011).

Edmondson (1999) claimed that it is advantageous to workers' performance if there is trust. The study stressed further that the openness in their communication would be directly affected if there is trust. This is because if members are confident of trust, the willingness to share skills and experience will be improved. Especially in enhancing workflow, the inadequacies of individuals will not be exposed until they feel it is safe to do so. If not, the worry that a team member's weakness could negatively affect their career in the future can overwhelm them (McAllister, 1995). Extant literature on knowledge management also validates that TCW is valuable to knowledge sharing and voluntary coordination, improving employees' working efficiency and quality. In addition, Ning et al. (2007) empirically found TCW to positively influence employees' work performance and satisfaction. Given these, we focus on TCW as an antecedent of job outcomes such as JS, CS, SRP, and IWB. Thus, we propose the following hypotheses.

This study explicitly focuses on TCW as a possible mediating factor and seeks to explain where SL's positive influence through TCW is prominent on job outcomes. As argued previously in the literature, the process of social exchange underlies trust in employees, which directly impacts the positive outcome of employees' reciprocal behavior with servant leaders. The reciprocation of employees' behaviors has been conceptualized in terms of job outcomes, especially those that exceed their job requirements. Moreover, some studies found trust a predictor (Colquitt et al., 2007), while Lee et al. (2020) established it as a mediator in the relationship between SL and performance. In addition, the mediating effect of TCW in the relationship between SL and organizational commitment was demonstrated in the literature (Goh and Low, 2014), while Schaubroeck et al. (2011) found trust as a mediator in the relationship between SL and team performance. This is an indication that trust induces the employee to exhibit positive outcomes. In view of this, we hypothesize that servant leaders positively influence job outcomes (JS, CS, SRP, and IWB) through TCW.

Aim

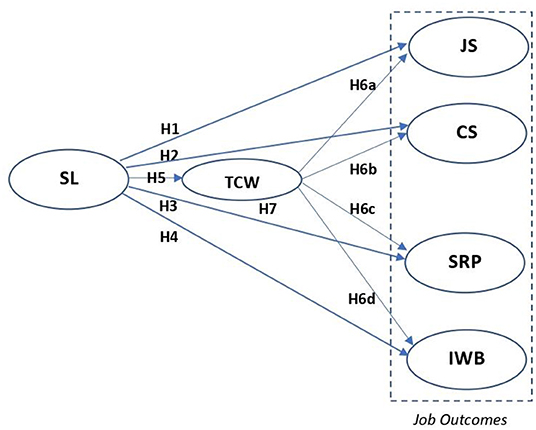

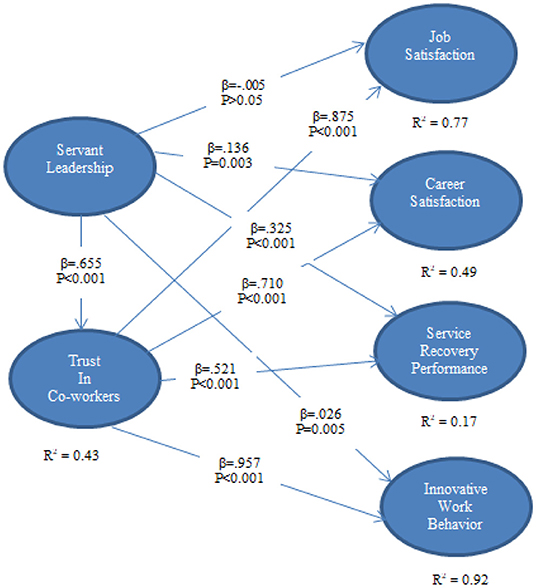

Along with the theoretical literature arguments and to fill the research gap, the present study aims to examine the influence of servant leadership on job outcomes and the mediating role of TCW in those relationships. In addition, the direct effect of TCW on job outcomes is investigated. Hence, the following hypotheses are shown in Figure 1.

H1: SL exerts a positive effect on employee JS.

H2: SL exerts a positive influence on CS.

H3: SL exerts a positive influence on SRP.

H4: SL exerts a positive influence on employees' IWB.

H5: SL will positively influence TCW.

H6: TCW has a positive influence on (a) JS, (b) CS, (c) SRP, (d) IWB.

H7: TCW mediates the relationship between a servant leader and (a) JS, (b) CS, (c) SRP, (d) IWB.

Methods

The research framework of this study is depicted in Figure 1, which indicates the nexus among variables. A nexus among the SL, TCW, and job outcomes (JS, CS, SRP, and IWB) is proposed in this framework, evaluating the mediating role of TCW. This study contends that SL will positively influence JS, CS, SRP, IWB, and TCW. In addition, we hypothesize that TCW will partially mediate the relationship between SL and job outcomes. In order words, SL will, directly and indirectly, influence employee JS, CS, SRP, and IWB.

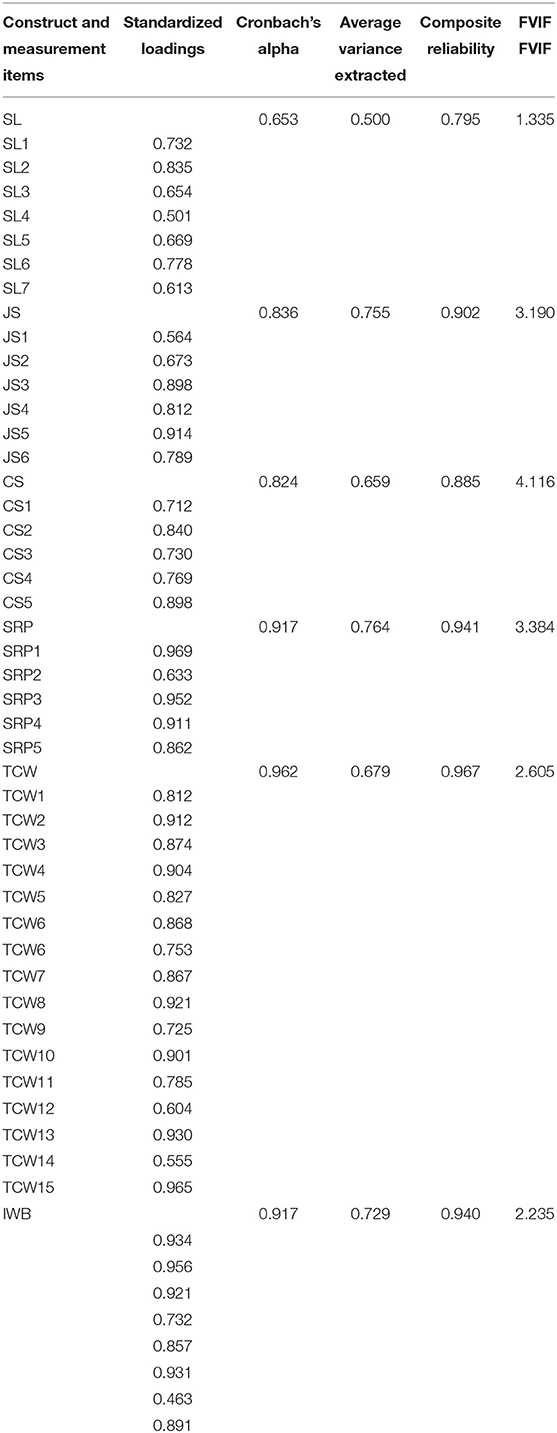

Model Measurement

The constructs measured in this study include SL, TCW, JS, CS, SRP, IWB (see Appendix for the items). The SL was measured with seven items adapted and modified from Barbuto and Wheeler (2006). The items are measured on a 7-point Liker scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Six items were adopted and modified from Greenhaus et al. (1990) for measuring JS, and the items were measured on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). As for the CS, five items were adapted and modified from previous studies (Wang et al., 2019). SRP was measured with five items adapted from Karatepe et al. (2019), arranged on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from never (1) to always (5). TCW was measured with 15 items sourced from Ferres (2002). Finally, IWB was measured with eight items adapted from Opoku et al. (2019) and arranged on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

Data Collection

The sample of this study consisted of full-time bank employees in the banks (public/private) of North Cyprus, which the authors observed to be an underrepresented country in the extant service research (Brown et al., 2018). The authors contacted the management of each bank in three major cities in North Cyprus (Lefkosa, Magusa, and Girne) through an official letter describing the study objectives and requested their permission for data collection. The bank management obliged our request, and subsequently, the banks were visited to meet with the employees to explain the details of the questionnaire. The participant understood that it was voluntary but encouraged to participate, and the management has endorsed the participation. Four employees and one manager were invited from each bank. The questionnaires were given to return the questionnaire in a sealed envelope. In all, 252 employee questionnaires were obtained from the employees. Moreover, to assess the employee's innovative work behavior and service recovery performance, one manager from each of the banks contacted, totalling 63, was invited to participate in the study. The managers' IWB and SRP questionnaires were matched with the employee questionnaire using an identification code. The demographic characteristic of the respondents reveals that 42.9% of the banks sampled are public banks, while 57.1% are private banks. In addition, 25.4% (64) of the respondents were male, while 74.6% (188) were female. The age of respondents was between 18 and 27 years (38.1%), 28 and 37 years (31.4%), 38 and 47 years (14.3%), 48 and 57 years (8.7%), and above 58 years old (7.5%). The participants' educational background showed that 35.3% have a Two-year college degree, 58.3% four-year college degree, and 6.4% were graduate degree holders. Moreover, the tenure of the respondents at the bank shows that 20.3% (51) have spent less than a year, 41.3% (104) have spent between 1 and 5 years, 20.6% (52) have spent between 6-10 years, 5.6% (14) have spent between 11 and 15 years, while 2.8% (7) and 9.5% (24) have spent between 16 and 20 years and above 20 years respectively.

Data Analysis

The model structure was tested using the WarpPLS 7.0 version. WarpPLS is a Partial Least Square regression that simultaneously analyses linear and non-linear relationships (Ferres, 2002). According to Pavlou and Fygenson (2006), Partial Least Square Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) effectively tests large and complex models, including mediating or moderating effects. This implies that modeling causal relationships between constructs and testing the predictions of the results that reflect the complexity of real-life is possible. PLS-SEM is also efficient when dealing with small samples, owing to its non-dependence on the normality of the data, and can also be employed for modeling reflective and formative constructs (Urbach and Ahlemann, 2010).

Results

Model Measures Assessment

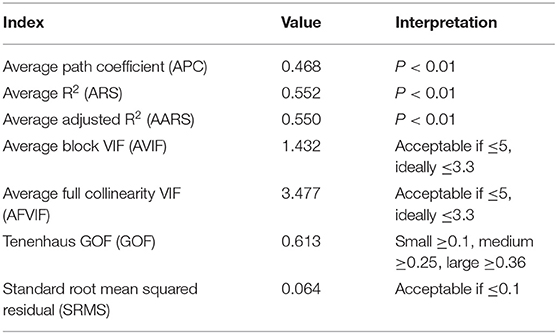

As presented in Table 1, the measurement model assessment results show that all items have acceptable loadings (>0.50). The Cronbach's alpha (>0.70), composite reliability (>0.70), and average variance extracted (>0.50) of all the constructs are above the minimum threshold, which is an indication of acceptable internal consistency. In addition, the average Full Variance Inflation (FVIF) for each variable is within acceptable levels, indicating the absence of collinearity between the constructs.

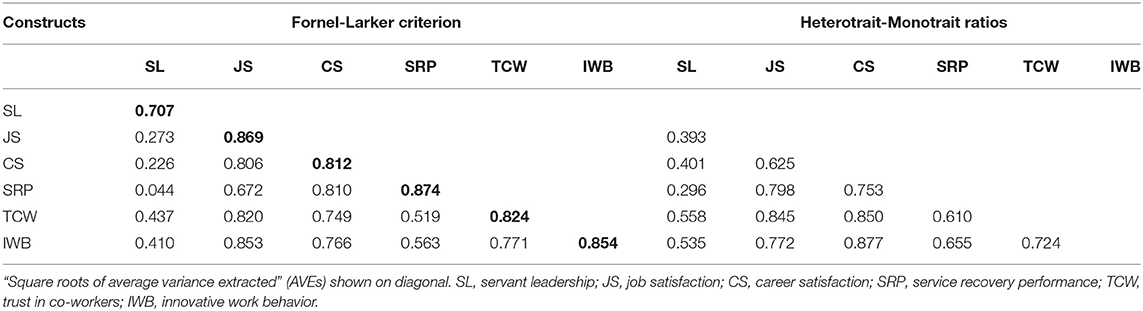

As presented in Table 2, the discriminant validity assessment results conform with Fornell and Larcker (1981) proposition that the square root of average variance extracted in diagonal of each construct must be greater than the correlations between that constructs and other constructs. Meanwhile, a new criterion (Heterotrait-Monotrait ratio) for assessing discriminant validity (Henseler et al., 2015) complemented the Fornell-Larcker criterion. The HTMT ratio shows an acceptable value (<0.9) which confirms the discriminant validity of the constructs.

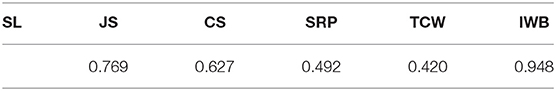

Moreover, regarding the common method bias, according to Kock (2015a), the coefficients of “full collinearity VIF” are specifically sensitive to “pathological common variations” across the constructs in methodological contexts that are the same as the one found in this study. This means that the sensitivity allows common method bias to be detected in a model which still passes the evaluation of convergent and discriminant validity criteria based on a “confirmatory factor analysis” (CFA), as we have in this study. Several findings suggested a threshold value of 5 acceptable and <3.3 to be the best for full collinearity VIF coefficients (Kock and Lynn, 2012; Kock, 2015a). Thus, with the full VIF presented in Table 1, none of the full VIF coefficients if greater than the acceptable threshold (≤5). In addition, according to Kock (2015a), “Stone-Geisser Q2 coefficients” (Geisser, 1974) are used for the assessment of “predictive validity”. The coefficient is only available endogenous latent variables. Kock (2015a,b) argued that a measurement model is considered acceptable “predictive validity” if the Q2 coefficients for the endogenous variables are >0. Thus, the Q2 results for job satisfaction, career satisfaction, service recovery performance, innovative work behavior, and trust in coworkers, as presented in Table 3, shows that our measurement model meets this criterion.

Structural Model Assessment

To assess the quality of the structural model, the model fit indicators were analyzed and described in Table 4. All indicators were either statistically significant or consistent with the respective thresholds, indicating the quality of the structural model (Kock, 2020).

Discussion

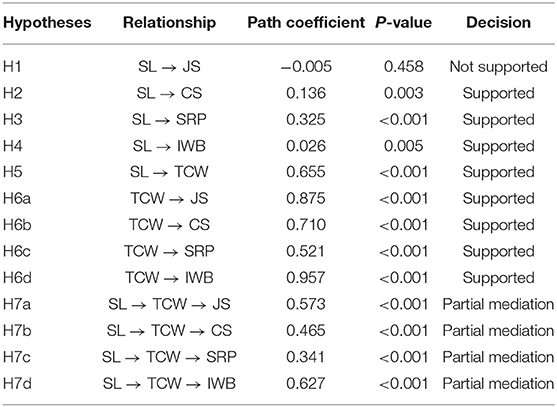

As shown in Table 5 and Figure 2, the hypothesized SL and JS relationship shows no significance (β = −0.005, p = 0.458). Therefore, it failed to support the hypothesis that SL positively influences employee JS. Meanwhile, the positive influence of SL on the other job outcomes i.e., CS (β = 0.026, p = 0.005), SRP (β = 0.325, p < 0.001), IWB (β = 0.136, p = 0.003), and TCW (β = 0.655, p < 0.001) as proposed in hypotheses 2, 3, 4, and 5 were found to be statistically significant. This implies that holding other variables constant, a change in the SL to be more effective will improve the employees' CS, SRP, their IWB, and TCW. In addition, the influence of TCW on job outcomes was hypothesized in H6 (a-d). The result as presented in Table 5 and depicted in Figure 2 shows that TCW exerts a positive influence on JS (β = 0.8755, p < 0.001), CS (β = 0.710, p < 0.001), SRP (β = 0.521, p < 0.001), and IWB (β = 0.957, p < 0.001). Owing to the significance of the path coefficients, we conclude that employee TCW positively influences JS, CS, SRP, and IWB.

From the result presented in Table 5, we found that TCW partially mediates the relationship between SL and JS (β = 0.573, p < 0.001), SL and CS (β = 0.465, p < 0.001), SL and SRP (β = 0.341, p < 0.001), and SL and IWB (β = 0.627, p < 0.001). Thus, we conclude that employee TCW partially mediates the relationship between SL and job outcomes (JS, CS, SRP, and IWB). Another interesting finding from our study is the explanation variations of the exogenous variable (SL) and the TCW (both exogenous and endogenous) on the endogenous variables (JS, CS, SRP, and IWK). As depicted in Figure 2, the results indicate that SL can provide about 43% of explanation variations in TCW. In comparison, 77, 49, 17, and 92% explanation variations in JS, CS, SRP, and IWB, respectively, can be provided by both SL and TCW.

This finding implies that employees will be more creative and satisfied if the SL is efficient and creates a working environment that will enable them to have confidence and trust in each other, improving organizational performance.

As the LMX theory contends, SL influences employees' job outcomes, which also serve as a solution to the dissatisfaction experienced by some employees. Dissatisfaction could be associated with employees' non-participation in decision-making and limited opportunities for voicing their opinion (Ilkhanizadeh and Karatepe, 2018). The positive influence of SL on job outcomes is consistent with the literature (Hoch et al., 2018; Lee et al., 2020). Our findings of the significant effect of SL on CS are consistent with some studies (Eby et al., 2003; Liden et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2019). This confirms the argument that leaders should encourage their followers' autonomy and inspire them to have individual thinking and bear responsibility for their career growth and development through the provision of mentoring and resources. Similarly, our finding on the positive influence of SL on SRP is compatible with studies of Echunha et al. (2009), Punjaisri et al. (2013), Daskin (2016). Finally, the significant positive impact of SL on employee IWB is in line with Yoshida et al. (2014), Panaccio et al. (2015), Peng and Wei (2018), Opoku et al. (2019), Lee et al. (2020) that demonstrate similar findings.

Conclusion

SL contributes to several significant outcomes for both individuals and groups. However, understanding the nexus between SL and the following job outcomes has not been exhaustively investigated. This study investigates the direct influence of SL and TCW on employees' job outcomes (JS, CS, SRP, and IWB). In addition, the mediating effect of TCW in the relationship between SL and job outcomes was investigated. The findings suggest that job outcomes are affected directly by SL, except for JS, which is only affected indirectly. In addition, TCW was found to significantly impact job outcomes and also mediate the relationship between SL and job outcomes.

From our findings, SL also affects JS, CS, SRP, and IWB indirectly through TCW. This finding is in line with the proposition of SET, which highlights trust as one of the requirements for social exchange. It is clear from this finding that TCW plays a significant role in the effect of SL on employees' job outcomes. The significance of the partial mediating effect of TCW found in this study could address the concerns that some variables mediate the relationship between SL and positive job outcomes, which are yet to be empirically examined (Ehrhart, 2004; Newman et al., 2017; Lee et al., 2020).

There are several implications from our study for managers and organizations. Managers need to ensure employee engagement at the individual level and to have a first-hand understanding of their abilities and capabilities which would promote their possible job outcomes. The present business climate characterized by “globalization” and “competitive advantage” requires firms to inspire their employees' positive outcomes. By confirming the significance of SL in a firm, this study argues that firms need to employ leaders who display SL tendencies like authenticity, humility, and stewardship. Moreover, the implementation of SL should be the priority of every manager because if this is not honestly pursued, any efforts about SL are bound to fail. Thus, managers should be interested in supporting high-quality exchange relationships among members. This could be achieved by recruiting employees characterized by openness to extroversion and experience. It is worthy to note that companies should develop a team-oriented atmosphere through events and other activities that could encourage job and non-job-specific interaction among the workers to nurture trust among the employees. The exercises could be specifically at training sessions or the first stages of the team development, although they might be constituted as part of the team's work schedule. In addition, training programs would be beneficial. Specifically, the bank employees should be trained about the SL practice in an organization. This training would provide an avenue to get effective feedback and thoughts that could assist the organization in better implementation. Consequently, employees with favorable views of servant leaders' practices will develop trust, which is essential in a social exchange relationship.

Future studies can utilize TCW as a moderating variable and trust in the organization, trust in a leader, and TCW concurrently as the mediating factors in the SL and employees' job outcomes relationship to enhance the understanding of the SL. Potential studies can also consider other leadership styles to explain positive job outcomes better. Finally, future studies can conduct a cross-sectional study with employees from different service industries. As a limitation of the current study, future research should explore the multilevel approach to testing the relationships between SL and the job outcomes under study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, project administration, and supervision: SI. Data curation: AR. Formal analysis, investigation, methodology, validation, visualization, writing—original draft, and writing—review and editing: AR and SI. Both authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcomm.2022.928066/full#supplementary-material

References

Ashill, N. J., Rod, M., and Carruthers, J. (2008). The effect of management commitment to service quality on frontline employees' job attitudes, turnover intentions and service recovery performance in a new public management context. J. Strat. Market. 16, 437–462. doi: 10.1080/09652540802480944

Avolio, B. J., Walumbwa, F. O., and Weber, T. J. (2009). Leadership: current theories, research, and future directions. Ann. Rev. Psychol. 60, 421–449. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163621

Babakus, E., Yavas, U., and Ashill, N. J. (2011). Service worker burnout and turnover intentions: Roles of person-job fit, servant leadership, and customer orientation. Serv. Market. Q. 32, 17–31. doi: 10.1080/15332969.2011.533091

Barbuto, J. E., and Wheeler, D. W. (2006). Scale development and construct clarification of servant leadership. Group Organ. Manage. 31, 300–326. doi: 10.1177/1059601106287091

Bass, B. M. (2000). The future of leadership in learning organizations. J. Leader. Stud. 7, 18–40. doi: 10.1177/107179190000700302

Bechky, B. A., and Okhuysen, G. A. (2011). Expecting the unexpected? How SWAT officers and film crews handle surprises. Acad. Manage. J. 54, 239–261. doi: 10.5465/amj.2011.60263060

Bhal, K. T., and Ansari, M. A. (2007). Leader-member exchange-subordinate outcomes relationship: role of voice and justice. Leader. Organ. Dev. J. 28, 20–35. doi: 10.1108/01437730710718227

Brown, S., Demetriou, D., and Theodossiou, P. (2018). Banking crisis in Cyprus: Causes, consequences and recent developments. Multinational Fin. J. 22:1–2, 63–118.

Chatbury, A., Beaty, D., and Kriek, H. S. (2011). Servant leadership, trust and implications for the“ base-of-the-pyramid” segment in South Africa. S. Afr. J. Bus. Manage. 42, 57–61. doi: 10.4102/sajbm.v42i4.505

Chen, Z. X., Aryee, S., and Lee, C. (2005). Test of a mediation model of perceived organizational support. J. Vocat. Behav. 66, 457–470. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2004.01.001

Chiniara, M., and Bentein, K. (2016). Linking servant leadership to individual performance: Differentiating the mediating role of autonomy, competence and relatedness need satisfaction. Leader. Q. 27, 124–141. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2015.08.004

Chinomona, R., Mashiloane, M., and Pooe, D. (2013). The influence of servant leadership on employee trust in a leader and commitment to the organization. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 4, 405–405. doi: 10.5901/mjss.2013.v4n14p405

Cho, Y. J., and Park, H. (2011). Exploring the relationships among trust, employee satisfaction, and organizational commitment. Public Manage. Review, 13, 551–573. doi: 10.1080/14719037.2010.525033

Colquitt, J. A., Baer, M. D., Long, D. M., and Halvorsen-Ganepola, M. D. (2014). Scale indicators of social exchange relationships: a comparison of relative content validity. J. Appl. Psychol. 99, 599. doi: 10.1037/a0036374

Colquitt, J. A., Scott, B. A., and LePine, J.A. (2007) ‘Trust, trustworthiness, and trust propensity: a metaanalytic test of their unique relationships with risk taking job performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 92, 909–927. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.92.4.909

Cropanzano, R., and Mitchell, M. S. (2005). Social exchange theory: an interdisciplinary review. J. Manage., 31, 874–900. doi: 10.1177/0149206305279602

Culbert, S. A., and McDonough, J. J. (1986). The politics of trust and organizational empowerment. Public Adm. Q. 10, 171–188.

Daskin, M. (2016). The role of leadership style on frontline employees' perceived ethical climate, polychronicity and service recovery performance: an evaluation from customer service development perspective. Girişimcilik ve Inovasyon Yönetimi Dergisi 5, 125–158.

Daskin, M., and Yilmaz, O. D. (2015). Critical antecedents to service recovery performance: some evidences and implications for service industry. Int. J. Manage. Pract. 8, 70–97. doi: 10.1504/IJMP.2015.068317

Davis, J. H., Schoorman, F. D., Mayer, R. C., and Tan, H. H. (2000). The trusted general manager and business unit performance: Empirical evidence of a competitive advantage. Strategic Manage. J. 21, 563-576. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0266(200005)21:5<563::AID-SMJ99>3.0.CO;2-0

De Jong, J., and Den Hartog, D. (2010) ‘Measuring innovative work behaviour. Creat. Innov. Manage. 19, 23–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8691.2010.00547.x

Dirks, K. T., and Ferrin, D. L. (2001). The role of trust in organizational settings. Organ. Sci. 12, 450–467. doi: 10.1287/orsc.12.4.450.10640

Dirks, K. T., and Skarlicki, D. P. (2009). The relationship between being perceived as trustworthy by coworkers and individual performance. J. Manage. 35, 136–157. doi: 10.1177/0149206308321545

Eby, L. T., Butts, M., and Lockwood, A. (2003). Predictors of success in the era of the boundaryless career. J. Organ. Behav. 24, 689–708. doi: 10.1002/job.214

Echunha, M. P., Rego, A., and Kamoche, K. (2009). Improvisation in service recovery. Manag. Serv. Quality 19, 657–669. doi: 10.1108/09604520911005053

Edgar, F., Geare, A., Saunders, D., Beacker, M., and Faanunu, I. (2017). A transformative service research agenda: a study of workers' well-being. Serv. Indus. J. 37, 84–104. doi: 10.1080/02642069.2017.1290797

Edmondson, A. (1999). Psychological safety and learning behavior in work Teams. Adminis. Sci. Q. 44, 350–83. doi: 10.2307/2666999

Ehrhart, M. G. (2004). Leadership and procedural justice climate as antecedents of unit-level organizational citizenship behavior. Pers. Psychol. 57, 61–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6570.2004.tb02484.x

Ellickson, M. C. (2002). Determinants of job aatisfaction of municipal government employees. Public Personnel Manage. 31, 343–358. doi: 10.1177/009102600203100307

Emerson, R. M. (1976). Social exchange theory. Ann. Rev. Sociol. 2, 335–362. doi: 10.1146/annurev.so.02.080176.002003

Eva, N., Robin, M., Sendjaya, S., Van Dierendonck, D., and Liden, R. C. (2019). Servant leadership: A systematic review and call for future research. Leader. Q. 30, 111–132. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2018.07.004

Ferres, N. (2002). Development of the workplace trust questionnaire (Unpublished masters thesis), University of Newcastle, Callaghan.

Ferres, N., Connell, J., and Travaglione, A. (2004). Co-worker trust as a social catalyst for constructive employee attitudes. J. Managerial Psychol. 19, 608–622. doi: 10.1108/02683940410551516

Fornell, C., and Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Market. Res. 18, 39–50. doi: 10.1177/002224378101800104

Geisser, S. (1974). A predictive approach to the random effect model. Biometrika 61, 101–107. doi: 10.1093/biomet/61.1.101

Giampetro-Meyer, A., Timothy Brown, S. J., Browne, M. N., and Kubasek, N. (1998). Do we really want more leaders in business?. J. Bus. Ethics 17, 1727–1736. doi: 10.1023/A:1006092107644

Goh, S. K., and Low, B. Z. (2014). The influence of servant leadership towards organizational commitment: the mediating role of trust in leaders”. Int. J. Bus. Manage. 9, 17–25. doi: 10.5539/ijbm.v9n1p17

Graen, G. B. (ed.) (2004). New Frontiers of Leadership (LMX Leadership Series). Greenwich, Conn: Information Age Pub.

Greenhaus, J. H., Parasuraman, S., and Wormley, W. M. (1990). Effects of race on organizational experiences, job performance evaluations, and career outcomes. Acad. Manage. J. 33, 64–86. doi: 10.5465/256352

Greenleaf, R. K. (2002). Servant Leadership: A Journey into the Nature of Legitimate Power and Greatness. New York. USA: Paulist Press.

Harrison, D. A., Newman, D. A., and Roth, P. L. (2006). How important are job attitudes? Meta-analytic comparisons of integrative behavioral outcomes and time sequences. Acad. Manage. J. 49, 305–325. doi: 10.5465/amj.2006.20786077

Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., and Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Market. Sci. 43, 115–135. doi: 10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8

Hoch, J. E., Bommer, W. H., Dulebohn, J. H., and Wu, D. (2018). Do ethical, authentic, and servant leadership explain variance above and beyond transformational leadership? A Meta-Anal. J. Manage. 44, 501-529. doi: 10.1177/0149206316665461

Ilkhanizadeh, S., and Karatepe, O. M. (2018). Does trust in organization mediate the influence of servant leadership on satisfaction outcomes among flight attendants?. Int. J. Contemp. Hospitality Manage. 30, 3555–3573. doi: 10.1108/IJCHM-09-2017-0586

Jaramillo, F., Grisaffe, D. B., Chonko, L. B., and Roberts, J. A. (2009). Examining the impact of servant leadership on salesperson's turnover intention. J. Personal Selling Sales Manage. 29, 351-365. doi: 10.2753/PSS0885-3134290404

Ji, S., and Jan, I. U. (2020). Antecedents and consequences of frontline employee's Trust-in-Supervisor and Trust-in-Coworker. Sustainability 12, 716. doi: 10.3390/su12020716

Jung, D. I., and Avolio, B. J. (2000). Opening the black box: An experimental investigation of the mediating effects of trust and value congruence on transformational and transactional leadership. J. Organ. Behav. 21, 949–964. doi: 10.1002/1099-1379(200012)21:8<949::AID-JOB64>3.0.CO;2-F

Karatepe, O. M., and Aga, M. (2016). The effects of organization mission fulfilment and perceived organizational support on job performance. Int. J. Bank Market. 34, 368–387. doi: 10.1108/IJBM-12-2014-0171

Karatepe, O. M., Ozturk, A., and Kim, T. T. (2019). Servant leadership, organizational trust, and bank employee outcomes. Serv. Indus. J. 39, 86–108. doi: 10.1080/02642069.2018.1464559

Khattak, M. N., and O'Connor, P. (2020). The interplay between servant leadership and organizational politics. Pers. Rev. 50, 985–1002. doi: 10.1108/PR-03-2020-0131

Kock, N. (2015a). Common method bias in PLS-SEM: a full collinearity assessment approach. Int. J. e-Collaboration 11, 1–10. doi: 10.4018/ijec.2015100101

Kock, N. (2020). Full latent growth and its use in PLS-SEM: Testing moderating relationships. Data Anal. Perspect. J. 1, 1–5.

Kock, N., and Lynn, G. (2012). Lateral collinearity and misleading results in variance-based SEM: An illustration and recommendations. J. the Association for Information Systems, 13, 546–580. doi: 10.17705/1jais.00302

Lau, D. C., and Liden, R. C. (2008). Antecedents of coworker trust: Leaders' blessings. J. Appl. Psychol. 93, 1130. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.93.5.1130

Lee, A., Lyubovnikova, J., Tian, A. W., and Knight, C. (2020). Servant leadership: A meta-analytic examination of incremental contribution, moderation, and mediation. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 93, 1–44. doi: 10.1111/joop.12265

Lewis, B. R., and Spyrakopoulos, S. (2001). Service failures and recovery in retail banking: the customers' perspective. Int. J. Bank Market. 19, 37–48. doi: 10.1108/02652320110366481

Liden, R. C., and Maslyn, J. M. (1998). Multidimensionality of leader-member exchange: an empirical assessment through scale development. J. Manage. 24, 43–72. doi: 10.1016/S0149-2063(99)80053-1

Liden, R. C., Wayne, S. J., Liao, C., and Meuser, J. D. (2014). Servant leadership and serving culture: Influence on individual and unit performance. Acad. Manage. J. 57, 1434–1452. doi: 10.5465/amj.2013.0034

Liden, R. C., Wayne, S. J., Zhao, H., and Henderson, D. (2008). Servant leadership: development of a multidimensional measure and multi-level assessment. Leader. Q. 19, 161–177. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2008.01.006

Lin, W. B. (2011). Factors affecting the effects of service recovery from an integrated point of view. Total Q. Manage. 22, 443–459. doi: 10.1080/14783363.2010.545553

Ling, Q., Liu, F., and Wu, X. (2017). Servant versus authentic leadership: assessing effectiveness in China's hospitality industry. Cornell Hospitality Q. 58, 53–68. doi: 10.1177/1938965516641515

Lytle, R. S., and Timmerman, J. E. (2006). Service orientation and performance: an organizational perspective. J. Serv. Market. 20, 136–147. doi: 10.1108/08876040610657066

Malik, M. A. R., Butt, A. N., and Choi, J. N. (2015). Rewards and employee creative performance: Moderating effects of creative self-efficacy, reward importance, and locus of control. J. Organ. Behav. 36, 59–74. doi: 10.1002/job.1943

Mayer, R. C., Davis, J. H., and Schoorman, F. D. (1995). An integrative model of organizational trust. Acad. Manage. Rev. 20, 709–734. doi: 10.2307/258792

McAllister, D. (1995). Affect-based and cognition-based trust as foundations for interpersonal cooperation in organizations. Acad. Manage. J. 38, 24–59. doi: 10.5465/256727

McCann, J., and Holt, R. (2009). Ethical leadership and organizations: an analysis of leadership in the manufacturing industry based on the perceived leadership integrity scale. J. Bus. Ethics. 87, 211–220. doi: 10.1007/s10551-008-9880-3

McGee-Cooper, A. (1998). Accountability as covenant: the taproot of servant-leadership. in Insights on Leadership: Service, Stewardship, Spirit, and Servant-leadership, ed. L. C. Spears (New York: John Wiley and Sons),77–84.

Miao, Q., Newman, A., Schwarz, G., and Xu, L. (2014). Servant leadership, trust, and the organizational commitment of public sector employees in China. Public Adminis. 92, 727–743. doi: 10.1111/padm.12091

Mujeeb, T., Khan, N. U., Obaid, A., Yue, G., Bazkiaei, H. A., Samsudin, N. A., et al. (2021). Do servant leadership self-efficacy and benevolence values predict employee performance within the banking industry in the post-covid-19 era: using a serial mediation approach. Adminis. Sci. 11, 114. doi: 10.3390/admsci11040114

Nedkovski, V., Guerci, M., De Battisti, F., and Siletti, E. (2017). Organizational ethical climates and employee's trust in colleagues, the supervisor, and the organization. J. Bus. Res. 71, 19–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.11.004

Newman, A., Schwarz, G., Cooper, B., and Sendjaya, S. (2017). How servant leadership influences organizational citizenship behavior: the roles of LMX, empowerment, and proactive personality. J. Bus. Ethics, 145, 49–62. doi: 10.1007/s10551-015-2827-6

Ning, L. I., Jin, Y. A. N., and Mingxuan, J. I. N. (2007). How does organizational trust benefit work performance?. Front. Bus. Res. China 1, 622–637. doi: 10.1007/s11782-007-0035-7

Opoku, M. A., Choi, S. B., and Kang, S. W. (2019). Servant leadership and innovative behaviour: an empirical analysis of Ghana's manufacturing sector. Sustainability 11, 6273. doi: 10.3390/su11226273

Ozyilmaz, A., and Cicek, S. S. (2015). How does servant leadership affect employee attitudes, behaviors, and psychological climates in a for-profit organizational context?. J. Manage. Organ. 21, 263–290. doi: 10.1017/jmo.2014.80

Panaccio, A., Henderson, D. J., Liden, R. C., Wayne, S. J., and Cao, X. (2015). Toward an understanding of when and why servant leadership accounts for employee extra-role behaviors. J. Bus. Psychol. 30, 657-675. doi: 10.1007/s10869-014-9388-z

Parker, S. K., Williams, H. M., and Turner, N. (2006). Modeling the antecedents of proactive behavior at work. J. Appl. Psychol. 91, 636–652. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.91.3.636

Pavlou, P. A., and Fygenson, M. (2006) ‘Understanding predicting electronic commerce adoption: An extension of the theory of planned behavior. MIS Q. 30, 115. doi: 10.2307/25148720

Peng, H., and Wei, F. (2018). Trickle-down effects of perceived leader integrity on employee creativity: a moderated mediation model. J. Bus. Ethics 150, 837–851. doi: 10.1007/s10551-016-3226-3

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., and Bommer, W. H. (1996). Transformational leader behaviors and substitutes for leadership as determinants of employee satisfaction, commitment, trust, and organizational citizenship behaviors. J. Manage. 22, 259–298. doi: 10.1177/014920639602200204

Punjaisri, K., Evanschitzky, H., and Rudd, J. (2013). Aligning employee service recovery performance with brand values: The role of brand-specific leadership. J. Market. Manage. 29, 981–1006. doi: 10.1080/0267257X.2013.803144

Russell, R. F. (2001). The role of values in servant leadership. Leader. Organ. Dev. J. 22, 76–84. doi: 10.1108/01437730110382631

Ruyter, K., and Wetzels, M. (2000). Customer equity considerations in service recovery: a cross industry perspective. Int. J. Serv. Indus. Manage. 11, 91–108. doi: 10.1108/09564230010310303

Saleem, F., Zhang, Y. Z., Gopinath, C., and Adeel, A. (2020). Impact of servant leadership on performance: The mediating role of affective and cognitive trust. Sage Open, 10, 2158244019900562. doi: 10.1177/2158244019900562

Schaubroeck, J., Lam, S. S. K., and Peng, A. C. (2011). Cognition-based and affect-based trust as mediators of leader behavior influences on team performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 96, 863–871. doi: 10.1037/a0022625

Schriesheim, C. A., Castro, S. L., and Cogliser, C. C. (1999). Leader-Member Exchange (LMX) research: a comprehensive review of theory, measurement, and data-analytic practices. Leader. Q. 10, 63–113. doi: 10.1016/S1048-9843(99)80009-5

Shalley, C. E., and Zhou, J. (2008). Organizational creativity research: a historical overview. In: Handbook of Organizational Creativity. New York, USA: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Sokol, S. (2014). Servant leadership and employee commitment to a supervisor. Int. J. Leader. Stud. 8, 89–104.

Urbach, N., and Ahlemann, F. (2010). Structural equation modeling in information systems research using partial least squares. J. Inf. Technol. Theor. Appl. 11, 5–40.

van Dierendonck, D. (2011). Servant leadership: a review and synthesis. J. Manage. 37, 1228–1261. doi: 10.1177/0149206310380462

Wang, Z., Yu, K., Xi, R., and Zhang, X. (2019). Servant leadership and career success: The effects of career skills and proactive personality. Career Dev. Int. 24, 717–730. doi: 10.1108/CDI-03-2019-0088

White, D. W., and Lean, E. (2008). The impact of perceived leader integrity on subordinates in a work team environment. J. Bus. Ethics 81, 765–778. doi: 10.1007/s10551-007-9546-6

Whitener, E. M., Brodt, S. E., Korsgaard, M. A., and Werner, J. M. (1998). Managers as initiators of trust: An exchange relationship framework for understanding managerial trustworthy behavior. Acad. Manage. Rev. 23, 513–530. doi: 10.5465/amr.1998.926624

Wikström, P. A. (2010). Sustainability and organizational activities–three approaches. Sustain. Dev. 18, 99–107. doi: 10.1002/sd.449

Wintrobe, R., and Breton, A. (1986). Organizational structure and productivity. Am. Econ. Rev. 76, 530–538.

Wirtz, J., and Jerger, C. (2016). Managing service employees: Literature review, expert opinions, and research directions. Serv. Indus. J. 36, 757–788. doi: 10.1080/02642069.2016.1278432

Keywords: servant leadership, career satisfaction, trust in coworkers, job satisfaction, service recovery performance, innovative work behavior

Citation: Rashid AMM and Ilkhanizadeh S (2022) The Effect of Servant Leadership on Job Outcomes: The Mediating Role of Trust in Coworkers. Front. Commun. 7:928066. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2022.928066

Received: 28 April 2022; Accepted: 15 June 2022;

Published: 18 July 2022.

Edited by:

Diyako Rahmani, Massey University, New ZealandReviewed by:

Debalina Dutta, Massey University Business School, New ZealandGalina Berjozkina, City Unity College Nicosia, Cyprus

Copyright © 2022 Rashid and Ilkhanizadeh. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Shiva Ilkhanizadeh, c2lsa2hhbml6YWRlaEBjaXUuZWR1LnRy

Adnan Mahmod M. Rashid

Adnan Mahmod M. Rashid Shiva Ilkhanizadeh

Shiva Ilkhanizadeh