- Department of English, Faculty of Humanities, University of Geneva, Geneva, Switzerland

Embodied cognition, kinaesthetic knowledge, and kinesic imagination are central not only to acts of creation but also to the reception of artworks. This article substantiates this claim by focusing on sensorimotricity in art and literature, presenting two sets of analytical distinctions that pertain to dynamics in gesture and movement. The first set of distinctions—kinesis, kinaesthesia, kinetics, and kinematics—and the second set—timing, tempo, and momentum—are used to analyse literary descriptions and visual depictions of movements. The first set of distinctions is discussed in the first part of the article in relation to medieval drawings and literary excerpts from different historical periods (in works by Ovid, Shakespeare, and Proust). The second part focuses on visual arts and leads to an analysis of Bruegel's Fall of the Rebel Angels, while the third part presents a kinesic analysis of the Apollo and Daphne episode in Ovid's Metamorphoses. A heightened attention to the cognitive processing of kinesic features in acts of reception enhances the role and responsibility of readers and viewers in the ways in which they grasp the movement-based meanings formalized by artists of various cultures and historical periods.

1. Introduction

Movement-based communication is grounded in the cognitive activation of perceptual simulations. Within the theoretical field of embodied cognition, the phrase perceptual simulation (also embodied simulation) refers to the dynamic activation of sensorimotor aspects in the pre-reflective cognitive processing of multimodal events1. Perceptual simulations are central to any act of artistic practice and/or reception, whether the artwork is a performance (e.g., dance, drama, music, martial arts) or the formalized configuration of gestures and actions in verbal or visual works (e.g., a poem or a drawing). The method of kinesic analysis, applied in this article, focuses on the specific ways in which a verbal or visual artwork creates movement-based meanings by eliciting in readers and viewers perceptual simulations of sensorimotor events. An important aspect of kinesic analysis consists in paying close attention to the outputs of pre-reflective perceptual simulations, bringing them to the reflective level—not to stabilize them into mental representations, but to account for their dynamic and sensorimotor readerly effects2.

The article focuses on two sets of distinctions which are applied in kinesic analysis. The first set, called the 4Ks, distinguishes between kinetics (laws of physics relative to movement in general, e.g., gravity), kinaesthesia (the sensations of movement in one's body), kinesis (the perception of movements), and kinematics (physiological configurations and biomechanical constraints, e.g., joint orientation). While the 4Ks are generally correlated in actual movements, the precision of a movement analysis is increased by distinguishing between such aspects.

The second set of distinctions is relative to time and distinguishes between tempo (or rhythm of beats), timing, and momentum. Momentum in physics refers to the quantity of motion in a moving body, expressed as the product of its mass and velocity. It has to do with the impetus gained by movement, and with the force or energy exhibited by the moving body. Figuratively, it refers to the driving force or advancing strength of a development or course of events. Momentum is often correlated with tempo through the repetition of a specific movement, and with timing in the exact succession in which events are unfolding. For example, the momentum of runners may vary according to the tempo of their steps, which has an impact on the timing of such an event as a fall. Depending on the momentum in the action of running, the fall may be more or less sudden and more or less hurtful.

The two sets of distinctions are applied in this article to human movements and their verbal description in literature and visual depiction in art. Such distinctions constitute analytical tools that are instrumental to the possibility of accounting for movement-based meaning-making practices in various historical periods. Particular attention is paid in Section 2 to the role played by kinaesthetic knowledge, and in Section 3 to kinesic imagination in literature and visual arts. Owing to shared kinaesthetic knowledge, the way a movement feels may be inferred from penned lines on a medieval parchment despite historical and cultural differences. Even when an artwork is centuries old, core aspects of kinaesthetic features are inferred by viewers, inflecting the dynamics of their perceptual simulations in acts of reception. This fact is illustrated in Section 2 with visual examples taken from medieval illuminated manuscripts and with literary examples from works written by Ovid (43 BC-17/18 AD), William Shakespeare (1564–1616), and Marcel Proust (1871–1922). These drawings and texts are expressive in as much as they trigger prompt and flexible sensorimotor simulations in viewers and readers. Their meaningful effects are in their inferred sensorial and perceptual dynamics.

Kinesic imagination is central to the ability to foster novel relations with our sensorimotor and interpersonal reality. Literature and art are often the fields where sensorimotor experimentation and innovation take place. Through centuries, artists and authors have found ways of activating viewers' and readers' kinaesthetic knowledge and kinesic imagination, prompting the retrieval of complex sensorial and perceptual information3. Section 3 focuses on the iconographic tradition representing the fall of the rebel angels. The Fall of mankind as it is narrated in Genesis elicited a desire to imagine a prequel to the events leading to Adam and Eve's transgression. This prequel is the fall of rebel angels. The three temporal distinctions of tempo, timing, and momentum are discussed in this section in relation to Pieter Bruegel's pictorial response to Hieronymus Bosch's paintings of the fall of the rebel angels and the Fall of mankind.

After illustrating the presence of kinesic, kinaesthetic, kinetic, and kinematic features in connection with tempo, timing, and momentum in art and literature of different historical periods, the article focuses in Section 4 on the Apollo and Daphne episode in Ovid's Metamorphoses. The two sets of distinctions discussed in Sections 2 and 3 are applied in Section 4 to literary analysis, offering a kinesic perspective on this much debated narrative. In the introduction to their 2020 collective volume, Sharrock et al. (2020, p. 4) call Ovid's Metamorphoses “one of the best known and popular works of classical literature, and, with the possible exception of Virgil's Aeneid, perhaps the most influential of all on later European literature and culture”. Embodiment and movement-based meanings call for attention in both Virgil's Aeneid and Ovid's Metamorphoses. I show elsewhere that the complexity of embodiment in the Aeneid can only be addressed through a careful analysis of narrated movements (Bolens, 2003). In the present article, I argue that a greater focus on sensorimotricity in Ovid's work suggests that movement-based meaning-making pervades the Metamorphoses and grounds the ways in which Ovid transformed his sources of inspiration into an artifact that influenced Western art and literature for centuries.

2. Kinaesthetic Knowledge in Drawings and Tropes

All arts and sports are grounded in an interconnection between the kinaesthetic ability to feel movements, indispensable for autonomous motricity, and the ability to see, hear, taste, smell, and touch. This interconnection between motricity and the senses is called sensorimotricity. In the arts, dance activates a minima kinaesthesia and haptics (the term haptic refers to the connection between touch and kinaesthesia). Haptics in dance includes the contact between feet and ground. In musical performance, hearing and haptics via contact with the instruments are cardinal. Kinaesthetic knowledge is manifest in the dexterity which artists develop in their practice, whether their skills involve an ability to swing their body or to pinch the strings of a musical artifact. Such skills entail a type of knowledge that expands through sensorial practice4. A person sensorially learns by practice and henceforth knows how a movement feels (Sheets-Johnstone, 2003, 2017). This knowledge is kinaesthetic, and it may be activated either when the person iteratively induces targeted sensations5, or when they see a movement that triggers in them the cognitive inferencing of such sensations.

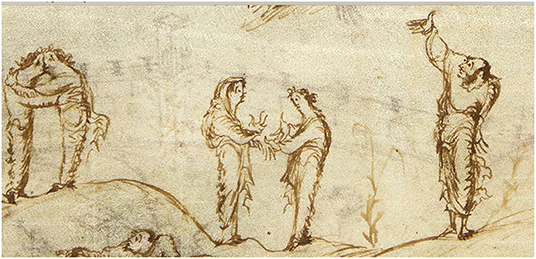

The acts of writing and drawing also involve movements, generally movements of the hands. As in dance and music reception, the actions of reading a poem or examining a drawing do not necessarily entail performing actual movements, whether the latter are correlated to the movements narrated or depicted in the artworks, or whether they are inferred from, say, the energetic qualities of a sketched line. However, in the same way as watching a dance triggers a cognitive processing that taps directly into the motor and premotor areas of the brain and the mirror system, literary and visual reception also activates cognitive faculties that are grounded in sensorimotricity (Noë, 2004; Gibbs, 2005; Jeannerod, 2007; Bolens, 2012; Cave, 2016; Coello and Fischer, 2016). The pen drawing in Figure 1 is an occasion to observe how static data, here in the shape of lines, can lead to dynamic inferences6. The hands of the couple at the center of the drawing suggest rapid movements of the fingers and the kind of dynamic gestures interlocutors tend to perform when engaged in a conversation. A few sketchy lines are enough to prompt viewers to infer open palms and lithe, jiggly fingers. Because of the visual context, i.e., two humans face to face at speaking distance, viewers read those lines dynamically, supplementing the communicative function gestures generally have in a conversation (Breckinridge Church et al., 2017; Morgenstern and Goldin-Meadow, 2022). The dynamics of gesture is central to the reception of this drawing, and it is inferred whether or not viewers reflect on the cognitive process that leads to the way they make sense of the drawing. In kinesic analysis, the pre-reflective inferential output of motor cognition is brought to the reflective level and acknowledged as sensorimotor and dynamic.

Figure 1. The Utrecht Psalter (Utrecht, Universiteitsbibliotheek, MS 32), fol. 49v, Psalm 84, detail, https://psalter.library.uu.nl/page/106.

The drawing in Figure 1 is part of the deservedly famous Utrecht Psalter, which was made in the early ninth century near Reims (Horst et al., 1996). The drawing illustrates line 11 of Psalm 84: Misericordia et veritas obviaverunt sibi; justitia et pax osculatæ sunt (Vulgate, Ps 84:11) [Mercy and truth have met each other: justice and peace have kissed] [Douay-Rheims Bible (1609/1955/1963), Ps 84:11]. The human figures are allegories, which explains why we find in a medieval psalter the unusual and endearing representation of two people kissing on the mouth. On the left of the drawing, Justice and Peace are indeed tightly kissing with full facial contact. On the right, the Psalmist is addressing the Lord with his whole right arm raised and his hand open upward. At the center, Mercy and Truth are interacting with animation. More than ten centuries later, viewers easily recognize in a few energetic lines a fundamental type of interaction—speaking and gesturing—, which to this day remains familiar at the level of perception, sensation, and intersubjective experience. Although the historical, sociocultural, and idiosyncratic ways in which people speak and gesture vary, basic sensorimotor features, involved in such actions, remain accessible across the centuries7.

The drawings of the Utrecht Psalter are remarkably expressive because the artists who penned them were able to communicate about dynamics in movement. The intensity of their art comes from their ability to prompt perceptual simulations of kinaesthetic sensations in viewers. In the action of drawing, the physical dynamic of the artists' hands successfully translated into lines that express dynamics in the gestures of represented hands. Figure 2 shows angels with equally animated hands, postures, and facial expressions. The angels are represented with human bodies simply endowed with wings, their invisible feet sharply planted in clouds, and their expressive gestures and neck postures prompting nuanced kinaesthetic inferences read as human feelings and mental states. Viewers' kinaesthetic knowledge is manifest in the activation of motor cognition in the visual processing of such a drawing. In the left hand of the angel on the right of Figure 2, a few curved lines are enough to convey a sense of intense tonicity in outstretched angelic fingers. The processing of these sketchy lines taps into our kinaesthetic knowledge of how it feels in the hand to open it as widely as possible. In such an instance, a perceptual simulation of this accessible sensation is not the representation of an abstracted object of knowledge, but the responsive activation of sensorial experiential knowledge.

Figure 2. The Utrecht Psalter (Utrecht, Universiteitsbibliotheek, MS 32), fol. 51r, Psalm 87, detail, https://psalter.library.uu.nl/page/109.

An ability to understand gestures and movements does not entail an ability to describe them verbally or depict them visually. There is no continuum between the ability to perform a movement and that of accounting for it verbally or pictorially. To now focus on language, sensorimotor concepts and verbal concepts must be distinguished, and the translation of the former into the latter (or vice versa) cannot be taken for granted8. A person may be able to perform a complex gesture consciously, repeatedly, and skilfully without knowing how to describe it verbally. The reverse is also true: to know how to identify a movement and what to call it (e.g., summersault) does not entail an ability to perform it. In certain domains and arts, such as dance, a coded terminology may exist that helps communicate verbally about movements (e.g., Labanotation and Benesh notation)9. Yet, even when a coding system is available, the exact manner of a gesture remains challenging to convey. In this respect, literature is a valuable source of information, as authors through centuries have found ways of using language to express complex sensorial and perceptual information.

A writer who was clearly interested in the sense of movement is Ovid. I will consider three short passages of the Metamorphoses (two here and one in Section 4), before turning to the Apollo and Daphne episode. In the first passage, Actaeon in the woods sees Diana naked, and she transforms him into a stag.

[…] nec plura minata

dat sparso capiti uiuacis cornua cerui,

dat spatium collo summasque cacuminat aures

cum pedibusque manus, cum longis bracchia mutat

cruribus et uelat maculoso uellere corpus;

additus et pauor est. fugit Autonoeius heros

et se tam celerem cursu miratur in ipso. (Met. 3.193-199—Ovid, 2015, Metamorphoses, hereafter Met.)

[Without more threats, she gave the horns of a mature stag to the head she had sprinkled (with water), lengthening his neck, making his ear-tips pointed, changing feet for hands, long legs for arms, and covering his body with a dappled hide. And then she added fear. Autonoë's brave son (Actaeon) flies off, marveling at such swift speed, within himself (trans. Kline, 2000)].

The line et se tam celerem cursu miratur in ipso, “marveling at such swift speed within himself” (Met. 3.199) refers to Actaeon's kinaesthetic sensations and the way he feels within himself, in ipso, while the momentum of his flight uncannily increases. Ovid foregrounds Actaeon's surprise at experiencing a transformation at the level of such sensations, as Actaeon is not yet aware of the transformation of his shape into that of a running stag.

A similar emphasis on the experience of a kinaesthetic shift can be found in the story of Picus turned into a bird by Circe (Met. 14.320-396). Like Actaeon, Picus becomes aware of his metamorphosis because of his kinaesthetic sensations and after he has become aware of them: ille fugit, sed se solito uelocius ipse / currere miratur; pennas in corpore uidit (Met. 14.388-389), “He ran, but was surprised to find himself running faster than before: he saw wings appear on his body” (trans. Kline, 2000). The transformation is first experienced in relation to kinaesthesia and the motoric sensations Picus is surprised to feel when moving. Because of this change in sensations, Picus looks at his body and sees feathers. Visual information comes in a second time and as a confirmation of kinaesthetic sensations. Interestingly, Ovid's phrasing creates a split between kinaesthetic sensations and visual perception. To express Picus's surprise, Ovid writes: sed se solito uelocius ipse / currere miratur, “but he was surprised that himself (ipse) was running faster than he himself (se) was used to.” The reflexive self is doubled and then split by the experience of its transformation. Picus's self becomes other, first sensorially and then perceptually as well.

While kinaesthetic sensations are internal, their manifestation is often perceptible externally. The specific quality of a gesture or movement is relative to kinaesthetic sensations within the moving person, but it can be perceived kinesically by an onlooker. I use the adjective kinesic to refer to the perception of movements and gestures. The perception of a gesture is distinct from its sensation. But kinesic perception often involves inferences that we draw from our empirical knowledge of kinaesthetic sensations. When we know what a gesture feels like, we infer its kinaesthetic quality by means of such knowledge. It is generally the case that we understand the meaning of a gesture because of such pre-reflective inferences, which connect kinesic perception with kinaesthetic sensations. In the following example, Marcel Proust conveys the specific kinesic quality of a gesture by means of tropes (or figures of speech, e.g., similes) that trigger sensorimotor simulations of kinaesthetic sensations, whereby the interactional meaning of the gesture is communicated.

In À la recherche du temps perdu, Proust narrates the interactions of his narrator Marcel, who is also his main intradiegetic protagonist, with a wide range of characters, including members of the French aristocracy. One of the latter is the Duchess of Guermantes. Proust often provides detailed information regarding the kinesic styles of his characters and the variable relational implications of their gestures (Bolens, 2017). For instance, the gesture of bowing to greet an interlocutor is a recurrent focus of attention. In the quotation below, the Duchess of Guermantes greets Marcel because he is in company of her nephew Saint-Loup.

Elle laissa pleuvoir sur moi la lumière de son regard bleu, hésita un instant, déplia et tendit la tige de son bras, pencha en avant son corps qui se redressa rapidement en arrière comme un arbuste qu'on a couché et qui, laissé libre, revient à sa position naturelle. [Proust (1988, p. 245), Le Côté de Guermantes I, 1920–1921].

[She let the light of her blue gaze rain upon me, hesitated for a moment, unfolded and stretched out the stem of her arm, leant forward her body which sprang back rapidly like a small tree that has been flattened and which, once released, returns to its natural position].

Social power games are often at the core of narrated scenes in La Recherche, and Proust regularly injects irony in his account of them. The passage quoted above (involving the natural setting of rain, flower, and tree) is relatively neutral in comparison to others. I selected it because its readerly activation typically taps into kinaesthetic knowledge. The metaphorical notion of an arm unfolding like the stem of a flower develops into a simile that shows the duchess's body bowing with the dynamics of a supple tree. The narrator's point of view is that of Marcel, the description pertaining to the kinesic perception of the act of bowing. However, the metaphor and simile, while being perceptual, elicit a translation of perception into sensation: the way the slim trunk of a small, supple tree (arbuste) springs back into its original position is liable to trigger cognitive simulations of how such dynamics may feel kinaesthetically. The analogy specifically targets the dynamic of the described movement, since human flesh, flower stems, and wooden trees entirely differ in terms of their materiality and autonomous motricity. Proust refers to tige (stem) and arbuste (small tree) not to prompt a formal representation but to convey the specific interactional and dynamic qualities of a character's gesture and bowing movement. It is by cognitively enacting this passage that its meaning becomes accessible.

Kinaesthetic knowledge can be activated via a kinesic trope that sheds light on the specific manner of a gesture. Such tropes may also convey information about an emotional state and the sensations it involves. In Shakespeare's Macbeth, after ordering the murder of Banquo and his son Fleance, Macbeth learns from the assassins that Banquo's throat has been cut, but that Fleance escaped, becoming a surviving witness of his culpability and ferocity. To express Macbeth's emotional experience of the situation, Shakespeare chooses powerful similes (Lyne, 2011; Crane, 2018).

Then comes my fit again; I had else been perfect,

Whole as the marble, founded as the rock,

As broad and general as the casing air,

But now I am cabined, cribbed, confined, bound in

To saucy doubts and fears (Shakespeare, 1986/2005, Macbeth, 3. 4. 20–24).

When he believes that the double murder has been completed, Macbeth's sense of relief and satisfaction is conveyed by mineral similes that prompt a cognitive activation of kinaesthetic sensations. Macbeth's feeling of security is akin to the fullness of marble and the solidity of a rock firmly entrenched in the ground. In the same way as Proust activates readers' sensorimotor knowledge of the movement of a supple tree springing back to its natural position to convey the exact manner of a bowing gesture, Shakespeare prompts perceptual simulations of wholeness based on the density of marble and the stability of grounded rocks. In his speech, Macbeth conveys with such similes the emotional and sensorial state he was experiencing the moment preceding the cognitive shock caused by the news he received: his tyrannical order to kill has created a new form of danger. This abrupt cognitive reversal takes him from a sense a perfect limitlessness, similar to the air that encompasses everything, to its radical opposite: confinement in a minimal, cribbing space, a constraining cabin where he lies shackled to his own paranoid and impudent self-delusions. The tropes that build the expression of Macbeth's emotional fracture involve the translation of physical data (associated with marble, rock, air, and a confined space) into kinaesthetic sensorial simulations.

Thus, kinaesthetic knowledge can be activated in literature by a kinesic trope that sheds light on the specific manner of a gesture (as in Proust) or an emotional feeling (as in Shakespeare). It may be at the core of visual representations that base their expressiveness on kinaesthetic inferences (as in the Utrecht Psalter) or also on kinematics, as can now be seen in folio 3 of MS Junius 11 (Figure 3). In the latter, rebel angels are hurled away from heaven, in the primordial fall that takes them down to hell. This drawing was made around 1000 in England by skilful artists who knew how to represent the kinematics of human bodies.

Figure 3. Bodleian Library MS. Junius 11, fol. 3r, 1000, Oxford, Bodleian Library, detail, https://digital.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/objects/d5e3a9fc-abaa-4649-ae48-be207ce8da15/surfaces/82365036-24f3-4c43-95fe-0a4a4d94d90a/. Terms of use: CC-BY-NC 4.0. Copyright holder Photo: © Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford.

It may be claimed that these artists decided to use kinematics as an expressive mean, because they do not depict a knee (or any other joint) bent backward anywhere else in the manuscript. In Figure 3, the upper left figure is represented with arms stretched over his head and with legs entangled into impossible kinematic directions. This deliberate pictorial decision mobilizes viewers' knowledge of the kinematics of human joints, prompting kinaesthetic inferences of what such a movement would feel like. A sense of contortion is induced, which powerfully expresses a distressing loss of orientation caused by the violent speed of the fall. The expressiveness of this group of falling angels is relative to viewers' kinaesthetic inferences based on their kinematic knowledge. In MS Junius 11 as in the Utrecht Psalter, viewers can make sense of depicted movements, while everything else has historically changed.

Among the technological changes that have transformed perception in the 20th century, cinema is first and foremost. The moving pictures made it technically possible to see a fall in slow motion. Given the speed of the event, the various stages of a fall, before the advent of cinema, had to be imagined. The falling angels of MS Junius 11 evince an effort to conceive of such intermediary stages. In the body at the top of Figure 3, disorientation is conveyed by a downward posture, by the distorted direction of the wings, and by the awkward positioning of the legs and right foot, the latter being twisted backward. The artists used viewers' kinematic knowledge and thwarted perceptual expectations to convey a sense of catastrophic fall.

The event of falling is based on gravity and a myriad of kinesic possibilities. The fall of the rebel angels has been repeatedly represented in Western visual arts, providing an opportunity to observe how artists used kinesic, kinaesthetic, kinematic, and kinetic features to communicate about movement-based meanings, and produce effects of tempo, timing, and momentum in static images.

3. Kinesic Imagination and Falling Angels

Few laws of physics are more permanently impactful than that of gravity. It is so central to human existence and experience that it has shaped one of the most pervading conceptual metaphors in Western cultures, that of the Fall. This conceptual metaphor is the name given to a plot in which the main protagonists, Adam and Eve, do not actually fall on the ground. It is the metaphorical meaning of falling that justifies such a name, in analogy with the spatialisation of an expulsion from heaven into the world, from up to down (Gibbs, 2017). Embodied cognition has been systematically at work in the development and amplification of this narrative, supplying for instance the episode of an actual fall, that of the rebel angels, leading to revenge and the Fall of mankind. The fall of the rebel angels is an apocryphal narrative, providing a rationale for the evil intention that led to the Fall of Adam and Eve (Silver, 2009).

Visually, the fall of the rebel angels has been typically translated into a flood of downcast bodies. In Figure 4, the right row of seats in heaven (on God's left hand) has been vacated by rebellious angels who, in the lower section of the image, are chased down and hurled toward a globe representing a ground containing hell. The expelled angels have been metamorphosed into entirely dark, dehumanized bodies, painted as silhouettes. The intensity and speed of their fall is conveyed by their disoriented flow, forcing them to crash into the globe at the bottom of the image. The force of the impact is suggested by the fact that they partially disappear into the ground. Even though the background is monochrome for being gilded, a sense of perspective is produced by the differing sizes of the bodies, the smaller ones suggesting greater distance.

Figure 4. Master of rebel angels, Sienne ca. 1340–1345, The Fall of the Rebel Angels, Paris, Musée du Louvre. Sous license Creative Commons CC BY-NC-SA 2.0. https://art.rmngp.fr/fr/library/artworks/maitre-des-anges-rebelles_la-chute-des-anges-rebelles_fond-d-or?force-download=1284658 and https://www.flickr.com/photos/79505738@N03/30682612335.

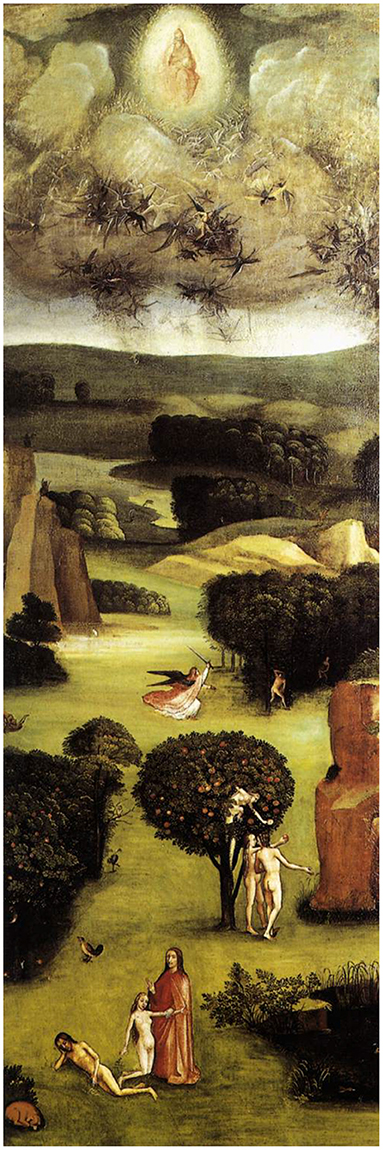

The interplay between flow and distance was developed by Hieronymus Bosch in two representations that combine in one painting the fall of the rebel angels and the Fall of Adam and Eve. In his Last Judgment Triptych now in Vienna (Figure 5), the left wing of the triptych shows a landscape, where the land is the stage of the Fall of mankind, and the sky that of the fall of the rebel angels. The Fall of Adam and Eve is visually narrated in three stages (Eve's creation, the forbidden-fruit transgression, and the expulsion from Eden), which unfold on two thirds of the painting, while the upper third of the panel represents the sky, where God in Majesty, surrounded by a mandorla of bright light, sits in the far distance.

Figure 5. Hieronymus Bosch (1450–1516), Last Judgment Triptych, inner left wing (Paradise), 1504–1508, oil on panel, 163.7 x 60 cm, Vienna, Akademie der bildenden Künste. Public Domain: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:BoschTheLastJudgementTriptychLeftInnerWing.jpg.

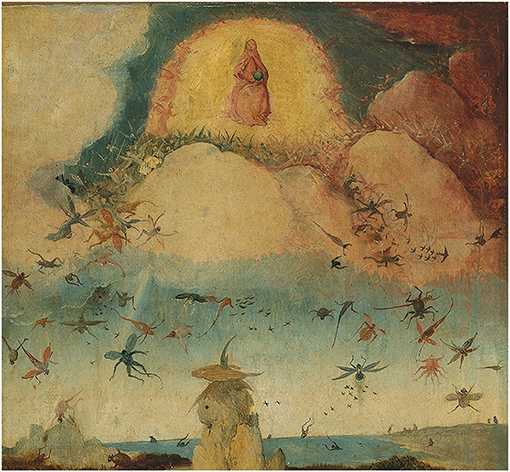

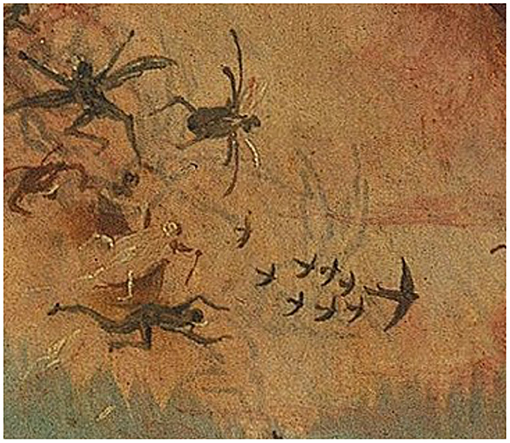

Beneath God, under heavy clouds, swarms of insect-like figures represent the falling rebels, pouring down like a far-away storm. In the Haywain Triptych now in Madrid (Figure 6), Bosch repeated the same striking iconography. However, this time the rebels are more distinct in their animalistic appearance. Some fall into the sea below, but others fly like hybrid insects amidst actual birds such as a swallow followed by its brood (Figure 7).

Figure 6. Hieronymus Bosch, The Haywain Triptych, 1512–1515, inner left wing, 147 x 66 cm, oil and tempera on oak panel, Madrid, Museo del Prado, detail. https://www.museodelprado.es/en/the-collection/art-work/the-haywain-triptych/7673843a-d2b6-497a-ac80-16242b36c3ce?searchMeta=rebel%20angels. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bosch_-_Haywain_Triptych.jpg.

Figure 7. Hieronymus Bosch, The Haywain Triptych, 1512–1515, inner left wing, 147 x 66 cm, oil and tempera on oak panel, Madrid, Museo del Prado, detail.

In the Haywain Triptych, the light that surrounds God in Majesty does not have the traditional shape of a mandorla anymore. Bordered by seraphim, it is rounded and suggests the shape of the sun, partially hidden by clouds. This iconography is further developed by Pieter Bruegel the Elder in his stunning representation of the fall of the rebel angels (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Pieter Bruegel the Elder (1527/30-1569), The Fall of the Rebel Angels, 1562, huile sur chêne (117 × 162 cm), Bruxelles, Musées royaux des beaux-arts de Belgique. Public domain, sous license CC BY-SA 2.0. https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fichier:Pieter_Bruegel_the_Elder_-_The_Fall_of_the_Rebel_Angels_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg.

Deeply inspired by Bosch, Bruegel turned the divine light surrounding God into an enormous sun, situated in the upper section of his painting. From this vast, luminous, and empty space, a crowded flow of hybrid creatures rushes toward the viewer (Figure 9).

It seems that Bruegel imagined zooming in on the swarms that pour from the clouds in his predecessor's paintings. Narrowing down on these buzzing bodies, Bruegel places the viewer in the path of this fast flow, creating a tornado of multimodal inferences. Working on the relation between distance and dynamic inferencing, his painting depicts a mobile chaos of embodiment that emerges from the sun and storms in our direction at maximal speed, ominously propelled by the unstoppable momentum of a chaotic flood of bodies.

The mass of visual information is so vast in this painting that viewers are led to temporally experience the perceptual process of their successive discoveries. Within the general momentum of the flow, the painting contains multiple scenes that have their own implied timing and tempo. For instance, tempo is suggested by the gestures of the archangel Michael and his warring companions, who repeatedly slash with their swords at the magma of creatures surrounding them. The tempo of striking and the timing of each wounding impact add to the momentum of Michael's surfing in the flow of creatures, his feet planted on the back of the beast of the Apocalypse hurled headlong. The beast's enormous body is gradually discovered behind multiple alien forms, its seven heads being connected to its diving belly (Meganck, 2014)10.

Among the myriad of details worth focusing on in Bruegel's masterpiece, two are particularly useful for an illustration of timing and momentum in relation to the 4Ks. The first is the falling duck-like bird situated in the upper left corner of the painting (Figure 10).

Beyond its humorous quality, this plummeting, chubby fowl keenly embodies a connection between gravity and the 4Ks. Unlike Bosch's swallows, and despite the fact that ducks and their likes can fly, this bird is not flying: it is free-falling, on its back, its feet up, and its bent wings enhancing a sense of helplessness. This body is not human and yet everything about it is understandable from the viewpoint of human kinematics linked to kinaesthesia and kinetics. Viewers can infer the type of sensations one would feel if their arms, neck, body, and legs were free-falling in that very position, anticipating the timing of a final impact caused by the crescendo momentum of such a long fall amidst angels and monsters. In this painting, Bruegel seems to have experimented with hybridity in several different ways. In the case of the duck, hybridity lies not so much in the shape of the animal as in our human cognitive understanding of this bird's uncanny experience of gravity. Its shape is not hybrid, but its inferred experience is. This duck falls in the way a human possibly would.

The other falling angels combine natural features (e.g., butterfly wings) with non-natural associations, such as a musical instrument with a lobster head and limbs in Figure 11, which is the second detail I wish focus on.

The feeling of uncanniness produced by Bruegel's painting is due to an impression of chaos, in which a sense of incongruity is paradoxically built on common denominators and sameness. One such common denominator is the exacerbated supine posture that dramatically exposes several nightmarish underbellies and gaping mouths. Another is the shape of limbs. In Figure 11, the trumpeter's arms have the same rod-like shape and angular elbows as the lobster crawling above him or her. Crossing over the lobster's left limb, the arm of an artichoke-like piece of vegetable is covered in a suit of armor exactly similar to that of the archangel Michael. Meanwhile, under the artichoke's arm, yet another armed limb is part of a full suit of armor, covering a body that lost its kinematic coherence, engulfed as it is in the mass of bodies. The similarity between these different rod-like arms increases a sense of understandable incongruity, as viewers' efforts at organizing their perception are both satisfied (identification takes place) and defeated (the identified elements belong to incoherent entities).

Multiple arms share the same rod-like shape, producing effects based on kinematic recognition even though the rest of the bodies seem unpredictably oneiric. Framing this growing mass of sliding and mutating bodies, temporality seems both frozen and rapid, made of repetition (hence tempo), catastrophic clashes (hence timing), all of it in the general momentum of a never-ending fall, prompting multimodal inferences of deafening sounds, horrendous smells, and suffocating haptic contacts. By invading his viewers with this crowded flow, Bruegel plays with effects of distance (or lack thereof), inferred movements, and the experience of time. The efficacy with which Bruegel translates momentum visually, before the invention of the motion pictures, is noteworthy. In literature, Ovid is equally notable for his ability to convey temporality by means of a static medium—written language—, evincing a focused attention to momentum, tempo, and timing in his narration of physical movements and transformations.

4. Ovid's Metamorphoses and The Rape of Daphne

Time in the Metamorphoses is an embodied phenomenon, rather than an “autonomous, abstract conceptual domain” (Sinha et al., 2011, p. 140). In Book 15, Ovid has Pythagoras declare that Time is motion, ipsa quoque adsiduo labuntur tempora motu, / non secus ut flumen (Met. 15.179-180), “the times themselves also glide in continual motion, not unlike a river.” The word time is in the plural form tempora, and it is subject of the action verb labor, labi, lapsus sum, to glide. The verb labor is an action verb which suggests that times actively move. Times step, lapse, slip, flow. Times take shape through moving forms, such as that of a river and its waves, but also through moving bodies and, one step further, through bodies transfigured as they move. Because Ovid's text is very much about such cinematic transfigurations, it is important to pay close attention to all possible temporal aspects in the Metamorphoses, such as the timing and dynamics of movements and gestures.

A straightforward example of the way in which Ovid combines the three aspects of momentum, tempo and timing is the metamorphosis of Lichas. Hercules is dying, burnt inside and out by the shirt of Nessus. As he is wandering alone, agonizing, he sees the servant Lichas, who delivered the fatal gift. Terrified, Lichas is cowering in a hollow of the cliff. Hercules sees in him the agent of his death and decides to murder him. He “seized him, and, swinging him round three or four times, hurled him, more violently than a catapult bolt, into the Euboean waters”: corripit Alcides et terque quaterque rotatum / mittit in Euboicas tormento fortius undas (Met. 9.217-218). The tempo of this threefold or fourfold revolving movement is followed by the hurling gesture, which is so powerful that the momentum thus gained transfigures Lichas into flint.

ille per aerias pendens induruit auras,

utque ferunt imbres gelidis concrescere uentis,

inde niues fieri, niuibus quoque molle rotatis

adstringi et spissa glomerari grandine corpus,

sic illum ualidis iactum per inane lacertis

exsanguemque metu nec quicquam umoris habentem

in rigidos uersum silices prior edidit aetas (Met. 9.219-225).

[Hanging in the air, he (Lichas) hardened with the wind. As rain freezes in the icy blasts and becomes snow; whirling snowflakes bind together in a soft mass; and they, in turn, accumulate as a body of solid hailstones: so he, the ancient tradition says, flung by strong arms through the void, bloodless with fright, and devoid of moisture, turned to hard flint (trans. Kline, 2000)].

The hard and fast tempo of Hercules's swinging gesture explains the speed and force of the hurling movement, so extreme that the victim's body dries out entirely and turns into flint (silex), in the same way as coalescing snowflakes turn into hailstones. In this context of violence, the metamorphosis emphasizes the importance of momentum. It is because of the speed and cumulative force of the hurled mass that the transformation takes place. In kinetic terms, the quantity of Lichas's motion is the product of its mass and velocity. The very continuance of motion is the effect of the impetus gained by the initial movement and ensuing inertia, thereby causing Lichas's mineral metamorphosis. Tempo and momentum play a key role in the transformation, leading to the timing of a fall into the sea, where Lichas forms a rock, says the text, carefully avoided by sailors who suspect that this motionless human shape might sense their presence. Because Ovid provides detailed sensorimotor explanations of the events he narrates, the processing of his text is liable to activate readers' sensorial and motor cognition.

Momentum in Ovid's Metamorphoses is associated with haptics, for example when a prey is hunted, and a predator is striving to seize his victim. Haptics plays out in the way one wants to touch and the other tries to escape from that grasp. Ovid tends to inject intense emotions into pre-existing legendary material. In the same way as Lichas is said to feel terror when he is hurled away and his body turns mineral, Daphne's extreme distress is emphasized when Phoebus chases her to rape her. The story of Phoebus Apollo and Daphne is a story of sexual predation, assault, and rape, where the victim is literally dehumanized and turned into a plant, the laurel, which is then used as trophy to crown winners of games and victors of imperial domination.

Classicists call this episode of the Metamorphoses “the first amatory episode of Ovid's poem” (Hardie, 2002, p. 71), “the first erotic tale of the poem” (Sharrock et al., 2020, p. 3; Spentzou, 2009, p. 389), a “love story” (Wheeler, 2000, p. 8), and even “a passionate love story” (Barkan, 1986, p. 226). By contrast, in his 1978 article “Rape and rape victims in the Metamorphoses,” Leo Curran stresses the fact that this tale is a story of rape. It is about sexual violence, and Ovid's insights into the plight of rape victims is “almost unique in ancient literature” (Curran, 1978, p 237). Curran substantiates this claim with detailed attention to Ovid's text, and remarks that

The commentators' arabesques of euphemism are the verbal manifestation of certain underlying prejudices and habits of mind. In the commentaries, as in society, it has not been the practice of men lightly to accuse another male of rape even if, as it turns out, the rapist is a figure in a myth thousands of years old. Classical scholars apparently require the same stringent proof of rape as do our least enlightened rape laws, police, and courts. When such proof is lacking, the reaction is disbelief or amusement (Curran, 1978, p. 215).

Amusement seems to be in order for Peter Knox in his 1990 article “In pursuit of Daphne”:

Few, for example, have failed to notice or smile at some of the less conventional aspects of Apollo's courtship of Daphne. The incongruous portrayal of the god in hot pursuit of the maiden, producing a long speech of courtship in mid-career, is perhaps the most curious feature of Ovid's presentation—at the very least we must admire Apollo's endurance and conditioning. The incongruities of this situation alone with its humorous undertones, however, do not seem sufficient to explain Ovid's purpose here. For that, it is necessary to pursue Daphne more vigorously ourselves […] (Knox, 1990, p. 185).

At the end of his article, Knox concludes:

Ovid chooses to forgo Apollo's song of courtship, and instead incorporates the themes appropriate to such a song into the speech delivered by Apollo on the run; the metaphor of the chase is thus expanded to become the principal subject of the narrative in a setting of thwarted passion and unmotivated aggression. A small point, perhaps; but some aspects both of Virgil's Sixth Eclogue and of the Metamorphoses may seem clearer if we have indeed caught up to Daphne (Knox, 1990, p. 202).

Scholars' witticisms, offering to “pursue Daphne more vigorously ourselves,” may sometimes be a sign of interpretive shortcoming, no matter how erudite their contexts. This is not to say that humor is absent from the Metamorphoses11, but rather that careful textual analyses should be carried out before academics declare that fun ought to be read in a story of rape. In 2009, Martin Helzle writes that “One minute one sees Apollo's pursuit of Daphne through the young woman's eyes as rape, the next moment it is seen through the god's eyes as just plain fun” (Helzle, 2009, p. 188). In short, for Helzle, it is all about readers' gendered point of view, and Ovid's text is amenable to all sorts of opinions about sexual violence. Yet, a kinesic analysis of the text suggests otherwise. My claim is not that there is only one correct way of reading Ovid's narrative, but that the perception of fun in the Phoebus and Daphne episode says more about the reader's ethical maturity than about the text itself. For the text is remarkably detailed about the sensorimotor and emotional reality of predation, involving terror, paralysis, and muteness in the victim. Ovid's attention to sensorimotricity and his ability to communicate it verbally is so central to the Metamorphoses that it can indeed be seen as one defining feature of his work's coherence, providing a possible answer to the oft-debated question of whether the Metamorphoses have any coherence at all (Wheeler, 2000).

A reason for scholars to call Phoebus and Daphne's tale “amorous” or “erotic” is that it involves the god Cupid. The text explains that Phoebus Apollo's “first love,” primus amor (Met. 1.452), is caused by the “raging wrath of Cupid,” saeua Cupidinis ira (Met. 1.453). Amor in Latin can denote the feeling of love as well as sexual intercourse. Apollo's first amor is immediately qualified as being caused by the raging/fierce/furious anger of Cupid, who creates the worst-case scenario of what can still be denoted by the word amor in Latin: sexual aggression and non-consensual intercourse. To decide that the episode is a love story because the word amor is used in it is at best simplistic. Ferocity and degradation drive the action.

Cupid is enraged because Apollo belittled him and his bow, claiming for himself the privilege of this weapon. Cupid retaliates by shooting him and Daphne with incompatible arrows: one arrow triggers sexual craving, the other precludes it (Met. 1.469). The interaction between Apollo and Daphne embodies this extreme tension, which interlinks in its narrative manifestation the two sets of distinctions discussed in this article. I begin by focusing on the connection between momentum and kinaesthesia. Daphne's speed and lightness is emphasized in a simile that compares her flight to wind, fugit ocior aura (Met. 1.502), she flees faster than the air. Phoebus pursues her, trying to convince her to slow down. This is the moment of his so-called courtship. The god is longwinded indeed, accumulating similes of animal predators and preys (wolf and lamb, lion and deer, eagle and dove), claiming that they do not apply to the present situation since he is not her enemy. He explains that the cause of his pursuit is amor (amor est mihi causa / sequendi, Met. 1.507) and tries to convince her by listing in detail his divine credentials. But the nymph, keen to emulate Diana and protect her own virginity, keeps running.

The fact that, given the action of running, Apollo's speech may feel awkward and verbose produces an important kinesic effect. The god strives to decrease Daphne's pace by means of his prolonged speech, promising to slow down if she does too: moderatius, oro, / curre fugamque inhibe; moderatius insequar ipse (Met. 1.510-511), “Slow down, I ask you, check your flight, and I too will slow” (trans. Kline, 2000). But Daphne wants to escape from his lust. Therefore, suddenly, the god's pace fires to extreme speed. The text highlights the intensity of this shift in momentum, adding that Daphne's flight further enhances her beauty as the wind reveals her body and flings her hair behind her. The timing of this turning point emphasizes the contrast between the two types of interactive and interdependent momentum.

The description of Phoebus' impetus is described by means of a hunting simile, further highlighting the abrupt shift in momentum. The interaction between Apollo and Daphne suddenly rockets into a high-speed chase, prompting kinaesthetic inferences of an extremely strained effort. Momentum and kinaesthesia interconnect both when Apollo tries to pull Daphne back by means of his speech, and when he decides to catch her regardless of her refusal. Kinaesthetic inferences concern the interconnection between the movements of both predator and prey.

ut canis in uacuo leporem cum Gallicus aruo

uidit, et hic praedam pedibus petit, ille salutem,

alter inhaesuro similis iam iamque tenere

sperat et extento stringit uestigia rostro,

alter in ambiguo est an sit comprensus et ipsis

morsibus eripitur tangentiaque ora relinquit;

sic deus et uirgo est, hic spe celer, illa timore (Met. 1.533-539).

[Like a hound of Gaul starting a hare in an empty field, that heads for its prey, she for safety: he, seeming about to clutch her, thinks now, or now, he has her fast, grazing her heels with his outstretched jaws, while she uncertain whether she is already caught, escaping his bite, spurts from the muzzle touching her. So the virgin and the god: he driven by desire, she by fear (trans. Kline, 2000)].

The muzzle of the hound is extended, outstretched (extento rostro) and about to bite, constraining the victim's every step. The latter, not knowing whether she has already been caught or not, escapes in extremis from the bites (morsibus) of this mouth that is already touching her (tangentiaque ora). The sentence tangentiaque ora relinquit shows the prey leaving behing (relinquere) the touching mouths (tangentia ora), where mouth is an accusative plural. The act of predation multiplies the organ of capture in a temporality where the tempo and speed of the aggression are vividly enhanced. Such an emphasis on the predator's wounding jaws in the extensive simile that describes the chase must be kept in mind. For the god will indeed enforce his mouth onto Daphne after her metamorphosis.

Daphne's strength is soon exhausted, and she begs her father, the river-god Peneus, to rescue her from Phoebus by ridding her of the figure that pleased the god too well, qua nimium placui, mutando perde figuram (Met. 1.547). The immediate impact of her prayer is her metamorphosis, whereby she is deprived not so much of her attractiveness as of her mobility.

uix prece finita torpor grauis occupat artus;

mollia cinguntur tenui praecordia libro;

in frondem crines, in ramos bracchia crescunt;

pes modo tam uelox pigris radicibus haeret;

ora cacumen habet; remanet nitor unus in illa (Met. 1.548–552).

[Her prayer was scarcely done when a heavy numbness seized her limbs, thin bark closed over her breast, her hair turned into leaves, her arms into branches, her feet so swift a moment ago stuck fast in slow-growing roots, her face was lost in the canopy. Only her shining beauty was left (trans. Kline, 2000)].

After a first shift in momentum during the race, a second one occurs when Daphne is abruptly transformed into a laurel tree. The speed of the metamorphosis is meant to defeat the speed of the god's haptic greed, separating the exact timing of transformation from the timing of contact. While Daphne desperately tries to escape from the sexual predator's clutch, his avid breath hanging over her neck and scattered hair (et crinem sparsum ceruicibus adflat, Met. 1.542), her call for help results in an immediate and utter loss of autonomous motricity. She is suddenly paralyzed and trapped within the bark and wood of a tree, her rooted feet planted within the ground, her arms growing (crescunt) into lifted branches, leaving her trunk exposed to the god's grasp and mouth. In terms of kinaesthetic sensations, this metamorphosis is catastrophic. It evokes the trauma experienced by victims of rape who find themselves paralyzed with terror.

When Phoebus reaches Daphne, her hardened envelope supposedly protects her from penetration. This is the reason why Daphne is generally seen as saved from rape. The idea that she is not raped because bark precludes penetration is in and of itself a sensorimotor inference elicited by a perceptual simulation. But, while rape is anyway not limited to vaginal penetration, an explicit reference to penetration is absent from other scenes of rape in Ovid's Metamorphoses. Here, Phoebus touches Daphne, and she recoils from within her bark. This is a horrifying moment, which interconnects kinesis, kinaesthesia, and haptics: the sexual predator touches his victim's body despite her reluctance and her hardened wooden envelope, and he enforces upon her a constrained contact that she is prevented from warding off. It is noteworthy that, in the first line of the following quotation, the use of the word amare denotes the predator's sexual actions.

hanc quoque Phoebus amat, positaque in stipite dextra

sentit adhuc trepidare nouo sub cortice pectus,

complexusque suis ramos, ut membra, lacertis

oscula dat ligno; refugit tamen oscula lignum.

cui deus “at quoniam coniunx mea non potes esse,

arbor eris certe” dixit “mea.” (Met. 1.553-558).

[Even like this Phoebus loved her and, placing his hand against the trunk, he felt her heart still quivering under the new bark. He clasped the branches as if they were parts of human arms, and kissed the wood. But even the wood shrank from his kisses, and the god said “Since you cannot be my bride, you must be my tree!” (trans. Kline, 2000)].

“The wood shrank (refugit) from his kisses.” The Latin verb refugit, from refugere “to flee back, to run away, to escape,” is formed on fugere “to flee” and the prefix re- which suggest a backward movement and/or iteration, thus intensifying the meaning of the verb and the idea of a strenuous and repeated attempt at escaping from a threat in order to find refuge elsewhere—and elsewhere for Daphne means farther within her trapped, embodied self. The wood (lignum) still (tamen) fled back from (refugit) the kisses (oscula). To fully understand this line, we need to actively use our kinesic imagination and kinaesthetic knowledge. Trapped in her flesh which has become wood, deprived of all autonomous motricity, Daphne is still desperately trying to escape from the coercive mouth of her aggressor. The deeply embodied impossibility of her flight makes her powerless effort even more sensorially vivid and horrifying.

The extreme violence of the aggression is conveyed by the timing of the two sudden shifts in momentum, leading to a sense of utter repulsion in haptic constraint, highlighting the suffocating horror of rape. Wood recoiling as flesh would is strikingly expressive of the extreme act of violence which Ovid narrates in this story of rape. To bypass this key aspect and turn this narrative into a “love story” in which “fun” is palpable is to miss a crucial point, adding more violence to the violence of rape.

Sensorimotricity is the register in which metamorphoses take place in Ovid's work, inducing the possibility of a felt understanding in readers. Readers of any century and of any gender are a priori cognitively equipped to perceptually simulate and experience the temporal qualities of an increasing momentum abruptly halted by a radical loss of motricity, triggering specific kinaesthetic sensations. The latter may potentially convey the haptic horror of an unwanted contact that paralyzes the victim. Ovid's narrative style provides an augmented access to kinaesthetic sensations inflected temporally via shifts in tempo (in the act of running), timing (in the moments of transformation and contact), and momentum (in the chase). Time as flowing motion is an experience conveyed by his style and narrative art, which elicit the possible awareness in readers of a deeply embodied and traumatic metamorphosis.

However, the rape of Daphne has been recycled into cultural capital and institutional domination. In his translation, A. S. Kline chose for lines 553 to 567 the heading “Phoebus honors Daphne.” Daphne, a victim of rape, is “honored” when her rapist touches and kisses her by force even though he can feel that her flesh-turned-wood still tries to escape, recoiling from his hands and mouth despite her paralysis. She has literally been reduced to the silence of plants by the intervention of her own father. Apollo can now decide that she belongs to him once and for all: “arbor eris certe” dixit “mea” (Met. 1.558), “you will be, he said, my tree!” The syntactic position of mea, separated from the rest of the sentence by dixit, puts an emphasis on the fact that the predator declares that he owns his victim.

Daphne turned laurel becomes another attribute of the god, beside his lyre and quiver. Apollo announces that her leaves will crown his forehead and serve as trophy for victorious Roman generals, acclaimed in processions through Rome after returning from their imperial conquests. She will also have to stand outside Augustus's doorposts, decorating the entrance to the emperor's palace. To read this after the violence of her transfiguring rape and decide that all is well, her supposed honor compensating for her loss of self and agency, is highly problematic.

Ovid's final line is striking: factis modo laurea ramis / adnuit utque caput uisa est agitasse cacumen (Met. 1.566-567), “the laurel bowed her newly made branches and seemed to shake her leafy crown like a head giving consent” (trans. Kline, 2000). J. D. Reed (2018, p. 408) rightly points out that “The ambivalence in that ‘seemed' with which the episode concludes is endemic to this poem's representation of identity and change”. Daphne has been silenced and deprived of autonomous movements. She can be read as anyone may wish to read her, deciding what the plant is bound to mean in submissive approbation. A person turned into a thing can only comply. In kinesic terms, she has been reduced to kinetics, the laws of physics whereby some breeze can make her branches move and supposedly approve, she who was able to run as fast as the wind. Her body turned into wood is now limited by new kinematic constraints, her feet rooted deep and her arms perpetually lifted. Once her terrified heart has recoiled within her new wooden flesh, her kinaesthetic sensations are blocked out and become impossible to infer. Her voice is irremediably silenced, as her face and mouth are lost in the canopy, precluding kinesic communication and intersubjective interactions. She is now just a symbol, a token of Apollo's power, and her ability to make meaning is forever torn away from her self-agency. She is left approving in the way a tree bows in the wind. Her kinesis and power to interact have been reduced to kinematic mechanisms prompted by the action of external forces (e.g., the wind) and the will of others (e.g., that of her “owner”). Her kinesic agency has been reduced to kinetic laws and reified kinematics.

Ovid's attention to sensorimotricity conveys the sense of trauma caused by the act of torture which rape is, transposing into the realm of deities (a bold move in itself) what could not be said of human authorities. For J. D. Reed, the Metamorphoses

is a study in the exercise of power, and rape (in Latin, such violations could have fallen under the legal category of stuprum) is one version of power over a person. The gods largely behave as absolutely…powerful humans might be expected to behave, without moral constraint, to satisfy their desires (remember that this poem offers no clear account of where these gods came from and why they deserve their power). Implicit in these personal interactions are questions of coercion and consent; episodes such as that of Daphne pose these questions in the realm of sex and gender (Reed, 2018, p. 407).

It is noteworthy that Ovid refers to Augustus as a reaching point in the Phoebus and Daphne episode. Putnam (2004, p. 71) suggests that “Ovid offers on several level at once an intense critique of contemporary Rome”. Referring to the laurel as a symbol of victory, he writes,

Between the simile [the laurel meaning victory] and Augustan reality lies, of course, the metamorphosis of Daphne, the raison d'être for the episode itself. Daphne's prayer for, and moment of, mutation both break up the epic continuum from Apollo as hunter-hound to Augustus in glory, and serve as extraordinary commentary upon it. […] In terms of hierarchies of power, Daphne is not only the “enemy” that Apollo is drawn to pursue but his, and Rome's, victim as well. She is the defeated without whom victory cannot take place, the loser who puts into relief the winner's celebration (Putnam, 2004, p. 81–82).

Daphne turned into the laurel tree is a “symbol of Apollo's public image and of Rome's pretensions to imperial power” (Putnam, 2004, p. 84). What is more, Octavian, once become Augustus, is known to have gradually taken on “the role of protégé of Apollo” (Zanker, 1988/1990, p. 48). His residence was emphatically close to Apollo's temple on the Palatine (Zanker, 1988/1990, p. 51), and the emperor's intense propaganda “reached the stage of blending his own image with that of the god” (Zanker, 1988/1990, p. 55). It is thus conceivable that Ovid's representation of Apollo as a rapist and compared to a drooling dog in Book 1 of the Metamorphoses is symptomatic of the reasons why the emperor decided to exile the poet. The exact reason of Ovid's exile is to this day unclear, but his Metamorphoses convey a representation of power that does not flatter authorities smoothly enough. The refinement of his style should not blind readers to the fact that, in Enterline's (2004, p. 1) words, “at the center of Ovid's Metamorphoses lie violated bodies”. In his work, gods acting like humans—suggesting humans acting as if they were gods—have a strong and systematic tendency to abuse their power. To grasp this dimension of Ovid's masterpiece, it matters that we pay attention to his poetics of sensorimotricity and activate our kinesic imagination and kinaesthetic knowledge consistently and reflectively. One immediate benefit would be to have Classicists and academics in general reconsider calling Apollo's rape of Daphne an “erotic” and “passionate” “love story”.

5. Conclusion

Kinesic imagination and kinaesthetic knowledge are fundamental cognitive and sensorial faculties shared by humans of any culture and historical period. They are manifest in artifacts such as literary texts and visual representations, which activate these faculties in acts of reception. The second section of the article illustrates this fact with visual examples taken from medieval illuminated manuscripts and with literary examples borrowed from authors of various periods (Antiquity, the Renaissance, and Modernity), using different languages (Latin, English, and French). The analysis of the selected drawings and quotations applies the 4K distinctions with a focus on kinaesthesia.

The 4Ks are associated with the second set of distinctions (momentum, tempo, and timing) in Sections 3 and 4. In Section 3, the focus is on visual artworks and the kinesic intelligence with which such artists as Bosch and Bruegel communicated visually about dynamic movement-based meanings relative to gravity and the myth-related action of falling. In Section 4, the focus is on literature and Ovid's masterpiece, in which time and movement constitute a conceptual unit. A kinesic analysis of the Apollo and Daphne episode in the Metamorphoses suggests that readers' kinesic imagination and kinaesthetic knowledge are instrumental to an understanding of the text. Kinesic intelligence in literature implies paying full attention to the ways in which another human created movement-based meanings, wherever and whenever this human lived. The added value of the two sets of distinctions discussed in the article is that they provide complementary means not only to describe movements but also, and most fundamentally, to perceive them at all. It is often the case that movement-based meanings are overlooked, even by specialists of a given field of research, when this type of analytical tools is missing, precluding the level of attention needed to consider such aspects fully.

This being the case, the two sets of distinctions discussed in the article are tools, no more no less. They afford the possibility of more focused acts of perception, thus allowing for more detailed analyses and descriptions. It must be stressed that they do not correspond to interpretive grids. To better perceive movements is the opposite of imposing preestablished meanings onto them. In Proust, the simile that compares the Duchess of Guermantes to a tree does not imply a loss of agency and intersubjectivity, whereas in Ovid, Daphne's transformation into a tree involves such a radical loss.

The ethical responsibility of artists and writers needs to be met by that of readers and viewers, thanks to their shared kinaesthetic ability to imagine how a gesture may potentially feel. While a movement-based meaning must unquestionably be situated in its historical and cultural context, kinesic imagination and kinaesthetic knowledge may not only help us delve deeper into an artwork, but also find in it the source of novel and more discerning relations with our own sensorimotor and interpersonal reality. For instance, they may possibly shed light on the difference between a story of rape and an erotic love story.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^For a discussion of perceptual simulations and the theoretical background relative to this notion, see the introductions in Bolens, 2012, 2021.

2. ^For a discussion of the ways in which the output of pre-reflective perceptual simulations can become the focus of reflective attention, see Bolens, 2018b, 2021. In Bolens, 2021, each chapter illustrates this possibility and its relevance to the fields of literary analysis and embodied cognition.

3. ^Instances of sensorimotor experimentation in medieval drawings are discussed in Bolens, 2022b.

4. ^On embodied intelligence in skilled performance, see Sutton, 2007; Sutton et al., 2011; McIlwain and Sutton, 2014; Toner et al., 2016; Bicknell, 2021.

5. ^For example, singers learn to produce, feel, and recognize sensations in their soft palate, jaws, throat, and chest that lead to desired sound effects.

6. ^I discuss the inferencing of dynamics in Bolens, 2018a,b, 2021.

7. ^For a detailed discussion of this claim, see Bolens, 2022a.

8. ^An attention to this issue is central to kinesic analysis. I discuss it in Kinesic Humor, 2021: 13-18 and analyse concrete instances of it throughout the book.

9. ^For a thorough discussion of such issues, see Maiorani, 2021, chap. 1: “How to Capture Dance Discourse?” 4-25.

10. ^Cf. https://artsandculture.google.com/story/9gXx-oPTgMeLKg

11. ^See Bolens, 2021, chap. 3: “Ovid and Chrétien de Troyes: Pyramus, Thisbe, and Yvain's hypersensitive lion,” 106-131, doi: 10.1093/oso/9780190930066.003.0007.

References

Barkan, L.. (1986). The Gods made Flesh: Metamorphosis and the Pursuit of Paganism. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

Bicknell, K.. (2021). Embodied intelligence and self-regulation in skilled performance: or, two anxious moments on the static trapeze. Rev. Philos. Psychol. 12, 595-614. doi: 10.1007/s13164-021-00528-7

Bolens, G.. (2003). “Le corps de la guerrière: Camille dans l'Énéide de Virgile,” in Körperkonzepte / Concepts du Corps: Contributions aux Études Genre Interdisciplinaires, eds Frei Gerlach, F., Kreis-Schinck, A., Opitz, C., and Ziegler, B. (Münster; New York, NY; Munchen; Berlin: Waxmann), 47–56. Available online at: https://archive-ouverte.unige.ch/unige:4852

Bolens, G.. (2012). The Style of Gestures: Embodiment and Cognition in Literary Narrative. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Bolens, G.. (2017). “‘Une prunelle énamourée dans un visage de glace': Marcel Proust et la reconnaissance des visages,” in Visages: Histoire, Représentations, Créations, eds L. Guido, M. Hennard Dutheil de la Rochère, B. Maire, F. Panese, and N. Roelens. Préface de Jean-Jacques Courtine (Lausanne: BHMS), 155–167. Available online at: https://archive-ouverte.unige.ch/unige:96243

Bolens, G.. (2018a). “Relevance theory and kinesic analysis in Don Quixote and Madame Bovary,” in Reading Beyond the Code: Literature and Relevance Theory, eds T. Cave and D. Wilson (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 55–70. Available online at: https://archive-ouverte.unige.ch/unige:153709

Bolens, G.. (2018b). “Kinesis in literature and the cognitive dynamic of gestures in Chaucer, Shakespeare, and Cervantes,” in Narrative and the Biocultural Turn, eds Wojciehowski, H. C., and Gallese, V., 81–103. Available online at: https://archive-ouverte.unige.ch/unige:104917

Bolens, G.. (2021). Kinesic Humor: Literature, Embodied Cognition, and the Dynamics of Gesture. New York: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/oso/9780190930066.001.0001

Bolens, G.. (2022a). Kinesic intelligence, medieval illuminated psalters, and the poetics of the psalms. Studia Neophilologica. doi: 10.1080/00393274.2022.2051733

Bolens, G.. (2022b). Inventive embodiment and sensorial imagination in medieval drawings: the marginalia of the Walters Book of Hours MS W.102. Cogent Arts & Humanities 9:1. doi: 10.1080/23311983.2022.2065763

Breckinridge Church, R., Alibali, M. W., and Kelly, S. D. (2017). Why Gesture? How the Hands Function in Speaking, Thinking and Communicating. Amsterdam; Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company. doi: 10.1075/gs.7

Cave, T.. (2016). Thinking with Literature: Towards a Cognitive Criticism. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198749417.001.0001

Coello, Y., and Fischer, M. H. (2016). Foundations of Embodied Cognition. Vol. 1: Perceptual and Emotional Embodiment. Vol. 2: Conceptual and Interactive Embodiment. London and New York: Routledge.

Crane, M. T.. (2018). “‘Cabin'd, Cribb'ed, Confin'd': images of thwarted motion in Macbeth,” in Movement in Renaissance Literature: Exploring Kinesic Intelligence, eds K. Banks and T. Chesters (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan), 171–188. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-69200-5_9

Curran, L. C.. (1978). Rape and rape victims in the Metamorphoses. Arethusa 11, 213–241. Available online at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/26308161

Enterline, L.. (2004). The Rhetoric of the Body from Ovid to Shakespeare. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gibbs, R. W. Jr.. (2017). Metaphor Wars: Conceptual Metaphors in Human Life. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Helzle, M.. (2009). “Ibis,” in A Companion to Ovid, ed. P. E. Knox (Malden and Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell), 184–193.

Horst, K., Noel, W., and Wüstefeld, W. (1996). The Utrecht Psalter in Medieval Art: Picturing the Psalms of David. Utrecht: HES Publishers.

Jeannerod, M.. (2007). Motor Cognition: What Actions Tell the Self. 2006. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198569657.001.0001

Kline, A. S.. (2000). Ovid [Publius Ovidius Naso], Metamorphoses. Available online at: https://ovid.lib.virginia.edu/trans/Ovhome.htm#askline

Knox, P. E.. (1990). In pursuit of Daphne. Trans. Am. Philol. Assoc. 120, 183–202+385–386. doi: 10.2307/283985

Maiorani, A.. (2021). Kinesemiotics. Modelling How Choreographed Movement Means in Space. New York and London: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780429297946

McIlwain, D., and Sutton, J. (2014). Yoga from the mat up: how words alight on bodies. Edu. Philos. Theory 46, 655–673. doi: 10.1080/00131857.2013.779216

Meganck, T. L.. (2014). Pieter Bruegel the Elder. Fall of the Rebel Angels: Art, Knowledge and Politics on the Eve of the Dutch Revolt. Milano: Silvana Editoriale, and the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium.

Morgenstern, A., and Goldin-Meadow, S. (2022). Gesture in Language: Development Across the Lifespan. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, and Washington: American Psychological Association. doi: 10.1037/0000269-000

Ovid (2015). Ovid [Publius Ovidius Naso], Metamorphoses (AD 5-8), ed. R. J. Tarrant. Oxford: Oxford University Press; Oxford Classical Texts. doi: 10.1093/actrade/9780198146667.book.1

Proust, M.. (1988). Le Côté de Guermantes I (1920-1921), in À la recherche du temps perdu, eds T. Laget and B. G. Rogers (Paris: Gallimard).

Putnam, M. C. J.. (2004). Daphne's roots: In memoriam Charles Segal. Hermathena 177/178, 71–89. Available online at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/23041541

Reed, J. D.. (2018). Annotations in Ovid, Metamorphoses. The New Annotated Edition. Translation by R. Humphries. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Shakespeare, W.. (1986/2005). Macbeth (prob. 1606, first folio 1623) in The Complete Edition, 2nd Edn, eds S. Wells and G. Taylor (Oxford: Clarendon Press).

Sharrock, A., Möller, D., and Malm, M. (2020). “Introduction: Unity in transformation,” in Metamorphic Readings: Transformation, Language, and Gender in the Interpretation of Ovid's Metamorphoses, eds A. Sharrock, D. Möller, and M. Malm (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 1–30.

Sheets-Johnstone, M.. (2003). Kinesthetic memory. Theoria et Historia Scientiarum 7, 69–92. doi: 10.12775/ths.2003.005

Sheets-Johnstone, M.. (2017). Agency: phenomenological insights and dynamic complementarities. Humanistic Psychol. 45, 1–22. doi: 10.1037/hum0000058

Silver, L.. (2009). Jheronimus Bosch and the issue of origins. J Aesthetics Art Criticism 1, 1–21. doi: 10.5092/jhna.2009.1.1.5

Sinha, C., Da Silva Sinha, V., Zinken, J., and Sampaio, W. (2011). When time is not space: the social and linguistic construction of time intervals and temporal event relations in an Amazonian culture. Lang. Cognit. 3:1, 137–169. doi: 10.1515/langcog.2011.006

Spentzou, E.. (2009). “Theorizing Ovid,” in A Companion to Ovid, ed P. E. Knox (Malden and Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell), 381–393. doi: 10.1002/9781444310627.ch27

Sutton, J.. (2007). Batting, habit and memory: the embodied mind and the nature of skill. Sport Soc. 10, 763–786. doi: 10.1080/17430430701442462

Sutton, J., McIlwain, D., Christensen, W., and Geeves, A. (2011). Applying intelligence to the reflexes: embodied skills and habits between Dreyfus and Descartes. J. Br. Soc. Phenomenol. 42, 78–103. doi: 10.1080/00071773.2011.11006732

Toner, J., Montero, B. G., and Moran, A. (2016). Reflective and prereflective bodily awareness in skilled action. Psychol. Conscious.: Theory Res. Pract. 3, 303–315. doi: 10.1037/cns0000090

Vulgate: Biblia Sacra juxta Vulgatam Clementinam. Clementine Vulgate Project. Available online at: http://vulsearch.sourceforge.net/gettext.html

Keywords: kinesis, gesture, sensorimotricity, cognition, Ovid, Daphne, Bruegel, Bosch

Citation: Bolens G (2022) Embodied Cognition, Kinaesthetic Knowledge, and Kinesic Imagination in Literature and Visual Arts. Front. Commun. 7:926232. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2022.926232

Received: 22 April 2022; Accepted: 08 June 2022;

Published: 22 July 2022.

Edited by:

Arianna Maiorani, Loughborough University, United KingdomReviewed by:

John Sutton, Macquarie University, AustraliaRaphael Lyne, University of Cambridge, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2022 Bolens. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Guillemette Bolens, Z3VpbGxlbWV0dGUuYm9sZW5zQHVuaWdlLmNo

Guillemette Bolens

Guillemette Bolens