- 1Faculty of Arts and Philosophy, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Milan, Italy

- 2Independent Researcher, Seattle, WA, United States

- 3Applied Technology for Neuro-Psychology Lab, IRCCS Istituto Auxologico Italiano, Milan, Italy

- 4Research Center in Communication Psychology, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Milan, Italy

In a society where advances and innovations occur on a daily basis, outreach and meaningful engagement with the general public become more challenging. The amount of information produced and repackaged surpasses existing systems in place to ensure truthful and factual engagement with the public, especially with complex matters regarding health science. This perspective paper discusses the value of contextualization and optimization for creating transparent and engaging content. We reflect on the innovative Transformative Storytelling Technique as a new category creating hybrid content to guide the experience of audiences, starting with the case of informal caregivers helping individuals living with neurological conditions. Moreover, we share our perspective on the important considerations for current and future development of highly targeted content using this technique. We include reflexions around the risks and ethical principles needed in the utilization and dissemination of “guided” content for the general public.

Introduction

Narrative and storytelling have long been noted as key aspects of human communication, and in recent years colleagues in the field of communication explored the use and the effect of storytelling in delivering prosocial messages (Weber and Wirth, 2014; Shen et al., 2015; Walter et al., 2018). It has been well-documented that specific narratives have an evident impact on the emotions, attitudes, and thoughts of the audience (Busselle and Cutietta, 2019; Slater and Rouner, 2002; Grall et al., 2021). In fact, narratives were shown to engage the audience in qualitatively deeper ways than other forms of messages (Grall et al., 2021).

This perspective paper reflects on the utilization of the recently developed Transformative Storytelling Technique (Petrovic and Gaggioli, 2021; Petrovic et al., 2022) for structuring and optimizing empowering narratives to deliver prosocial and health stories. We developed the Transformative Storytelling Technique (TST) as a hybrid method for merging fictional structure and real-life accounts to guide the audiences' experience and provide support for the often solitary and exposed role of informal caregivers caring for spouses, relatives, and friends. Scaled up, the TST model can potentially serve as an important tool in efficient support and education.

First, we will address the theoretical and empirical background of storytelling used for health support. Then we will reflect on the role of storytelling in large-scale support, education, and healing, leading the discussion toward specific implications of TST. In particular, we will draw attention to relevant considerations of the technique that have the potential to facilitate productive public engagement with health and science. Finally, we will discuss ethical requirements in utilizing TST and alternatives to contextualize, optimize, and provide transparency for this new form of content.

Theoretical and empirical background of storytelling

Stories are immediate and intuitive ways to convey information to an audience. The audiences' subjective experience of the story, however, has long been considered an outcome or effect of the story (Grall et al., 2021). We divide storytelling mechanisms into two interrelated categories: the function of the listener/viewer and the function of the story.

The function of a listener/viewer

Within the function of a listener/viewer we address the human-related aspects which theoretically support the effectiveness of storytelling. Following Bruner's work (Bruner, 2003) it can be suggested that individuals make sense of the experiences and events by imposing a narrative framework across the information given through the story. This process of narrative thinking to form an understanding of events and information is considered universal and a natural human inclination noted even at the early age when toddlers make sense of their new experiences (Nelson, 2006; Costabile, 2016).

Another related notion is the inner or scripted knowledge of the self that appears as an outcome of the sense-making of outside events that are either perceived through nuclear episodes (McAdams, 1988), memorable events (Pillemer, 1998), self-defining memories (Singer, 1995), or autobiographical memory narratives (Habermas and Bluck, 2000). Interestingly these are nicely synthesized by Singer (2004) with “narrative processing”, described as: “storied accounts of past events that range from brief anecdotes to fully developed autobiographies” (Singer, 2004, p. 442).

The aforementioned could also be understood through McAdams's proposal (McAdams, 1987) that “identity is a life story”, which consists of lived past, perceived present and imagined future (McAdams, 2011). In other words, lived experiences are turned into inner stories that shape individuals and help them develop meaning and a sense of self. Narrative identity is an all-encompassing term that places the individual meaningfully in a culture, provides cohesion between past, present, and anticipated future, and supports the merging of ongoing narratives into the story of self (McAdams, 2011). Therefore, the ability to establish a linear chronological story sequence of events and experiences builds one's identity (Habermas and Bluck, 2000).

On the other hand, fragmented self-stories or misapplied coherence (e.g., If I were taller, they would like me better) can lead to a series of psychological disorders such as trauma or addiction (Singer, 1996; Habermas and Bluck, 2000). In fact, failure to take a step back and constructively assign meaning to experiences will ultimately result in obsessive thoughts or behaviors (Singer and Conway, 2011).

Furthermore, the attribution theory has an important role in storytelling research. The value of causal attribution in storytelling can be argued at the level of identification and engagement with the story. The process of causal attribution is well summarized in three consecutive steps (1) An individual recognizes the behavior observed, (2) Makes dispositional attribution to the behavior, (3) Observes the distinct or unique characteristics of the behavior and adjusts his/her attribution more closely to the actuality of circumstances–i.e., observes the story more openly rather than creating attribution based on internal pre-set knowledge and experience (Walter et al., 2018).

However, bearing in mind that the third step (see above step 3) demands significant cognitive resources to be used, following through requires a certain type of motivation which is in essence closely related to the second category that we named the function of the story. Concretely, in a meta-analysis (Burger, 1981) on causal attribution for accidents, the observers tended to attribute less responsibility to the perpetrator when they were situationally or personally similar to him/her. This implies that the similarity motivated the observer to engage more complex cognitive processes mentioned in the step three of the causal attribution, to further understand and even justify the perpetrator.

In this manner, the identification is closely supported by the story engagement, which is the function of the story rather than individual function. In fact, it is the structure of a story that determines the engagement of the audience, and it is the identification with the protagonist that maintains it. In this paper, we consistently refer to the engagement defined in communication sciences as a type of selective attention toward messages conveyed in the story (Schmälzle et al., 2015), but will also reflect here on the engagement as defined in neuroscientific terms with neurocognitive processing (i.e., post-perceptual brain processes where content prompts sustained processing of the messages).

The function of the story

Narrative engagement is best explained as story involvement, while identification is more closely related to the involvement with a specific character and is also influenced by the existing empathy of the individual (Cohen, 2001; Walter et al., 2018). Narrative engagement has been recognized as the main mediator between exposure and acceptance of story-consistent beliefs (Busselle and Bilandzic, 2008) suggesting that highly engaging narratives need to lead the audience into considering external factors of the portrayed events to surpass the causal attribution (Walter et al., 2018). Therefore, the story must portray characters that are not socially distant or controversial to the audience (Ritterfeld and Jin, 2006; Slater et al., 2006; Walter et al., 2018).

The power that stories hold in changing recipients' worldviews or attitudes has been attributed to the situational state of being “transported” into the story world (Schreiner et al., 2018). The transportation theory of narrative persuasion poses absorption into a story as a key mechanism of narrative impact (Golding, 2011). However, determinants that might enable “transportation” are still hypothesized.

A neuroimaging finding demonstrated that narrative messages are processed in a hierarchical structure, starting from the auditory sensory processes analyzing the property of the sound, to linguistic processes that separate words from the sentence and assign the meaning (Grall et al., 2021). In fact, non-narrative messages such as short radio commercials are processed in this way. However, more complex engaging narratives which follow the concrete structure and depict emotional events or relate closely to the life circumstances of the listeners require higher-order cognitive and emotional responses to enable comprehension and social-cognitive inferences (Grall et al., 2021).

Similar to the engagement, which is the function of the story, studies suggest that “transportation” is a function of the story itself but also a stable recipients' disposition (Green and Brock, 2000; Dal Cin et al., 2004; Green, 2004; Schreiner et al., 2018). In this aspect, the action of being “transported into the story world” requires the co-activation of attention, imagery, and emotion (Green, 2004), meaning that the story must be set in such a manner to evoke this activation.

Finally, Slater et al. (2006) argue that when identifying with the main character of a story (i.e., being transported into the story world), cognitive responses become more positive since the absorption and identification are incompatible with counterarguin–i.e., sharing the opposite beliefs about the events, reactions, or feelings portrayed in the story (Slater and Rouner, 2002; Slater et al., 2006). Therefore, mastering the craftsmanship of engaging narratives and their interrelated functions (i.e., viewer/listener and story function) is still an ongoing process.

Storytelling for a large-scale support

We use the term narrative to describe the underlying structure of a story that creates sequenced tension between events or positions while we define storytelling as a tool for sharing the main narrative following a specific story plot. Storytelling has been used across studies to improve attitudes, behavior, and to provide support and education for many different audiences. Numerous papers have already designed and delivered unique storytelling for distinct populations, and in doing so achieved promising results.

For instance, Walter et al. (2018) investigated the persuasive power of storytelling in attitude shifts toward the transgender population, undocumented immigrants, as well as countering islamophobia. Similarly, Iversen (2019) reflected on the utilization of fiction in storytelling for social issues through two NGO campaigns delivered as video stories about the refugee children and their struggle to survive the war and consequences of the war. While the first study explored the persuasive power of stories, the second one engaged a narrative through a mix of fiction and non-fiction to raise awareness of the needs refugee children have who live in disadvantaged positions.

Carragher et al. (2021) used storytelling as a therapeutic approach for individuals living with aphasia and demonstrated an additional role of storytelling in improving aspects of language and communication. Similarly, the authors of this paper (Petrovic et al., 2022) demonstrated the application of storytelling on a sample of informal caregivers. Moreover, in a large-scale digital project exploring the role of storytelling in formal education, storytelling also showed excellent results in supporting the knowledge acquisition in a sample of over 17.000 students, as well as in media literacy, and improvement in attitudes and behaviors of the students (Blas and Paolini, 2013).

In a study by Filoteo et al. (2018) storytelling has also been used via therapeutic software for Alzheimer's and other related dementia patients. The patients who used software to create storytelling reported significant improvement in anxiety, depression, and overall emotional distress post-storytelling exposure. Considering the limited capacity of the current pharmaceutical treatments for dementia, such large-scale support for individuals living with dementia can be noted as an excellent addition to current tools.

The power of storytelling is also recognized and further expanded in the book Video and Filmmaking (Cohen et al., 2015) where authors demonstrate numerous digital storytelling intervention tools for mental health. In addition, Spierling and Szilas (2008) synthesize the existing interactive storytelling approaches as part of digital narrative practices and expand on successful prototypes used both for health and art practice.

Considering the existing examples demonstrated through the aforementioned studies, we inevitably wonder what the limits of storytelling in large-scale support might be and how we might fine-tune the storytelling to deliver accessible help across the world. For instance, each day millions of users join to listen to podcasts which are delivered in such a way that personal stories are turned into universally applicable lessons for the audiences. Therefore, could the combination of proper technique and a form of podcast be a useful mental health support to serve large audiences across media and device-types? We argue that TST could be one such practical application.

Transformative Storytelling Technique

We developed the TST in our effort to address the support needs of informal caregivers. However, throughout the process of developing the guided approach for designing stories for caregivers, we also noted the potential power of TST in large-scale support. The technique itself is developed in such a manner that it requires a target population. In essence, the building blocks of the technique cannot be achieved without the target population. However, the repetitive application of the TST across groups has the potential to enable access to large-scale support for different individuals across the world.

Informal caregivers are family members or close others who provide long-term care for a loved one in need, with no financial benefit. After exploring the existing digital solutions for informal caregivers (Petrovic and Gaggioli, 2020) and reflecting on how these solutions are used in the caregiving context, we noted a gap in the existing tools for supporting and facilitating the shift into the caregiving role and understanding personal and care related needs throughout the role (Petrovic et al., 2022).

To empower informal caregivers and provide meaning-making regarding the relationship shift (e.g., from a family member into a caregiver) and practical role-related skills, we turned to digital storytelling techniques. However, no existing mental health digital storytelling technique for guiding and designing group and target population support was discovered. Therefore, we developed the Transformative Storytelling Technique (Petrovic and Gaggioli, 2021; Petrovic et al., 2022) that can be adapted to both audio and video formats and is applicable to large populations or target groups.

The technique relies on narrative principles in therapy, the theory of narrative identity (McAdams and McLean, 2013), Freytag's pyramid for dramatic story plots (1863), and past empirical work on the mechanisms of storytelling. With TST, we approach the problematic or traumatic experience as an issue within the narrative identity of the self and apply narrative principles in therapy to re-author the story by using Freytag's pyramid as a story arc for digital stories. The TST story portrays the life story of a fictional character who goes through different points of the story plot: the beginning, rising action, climax point, resolution, and denouement.

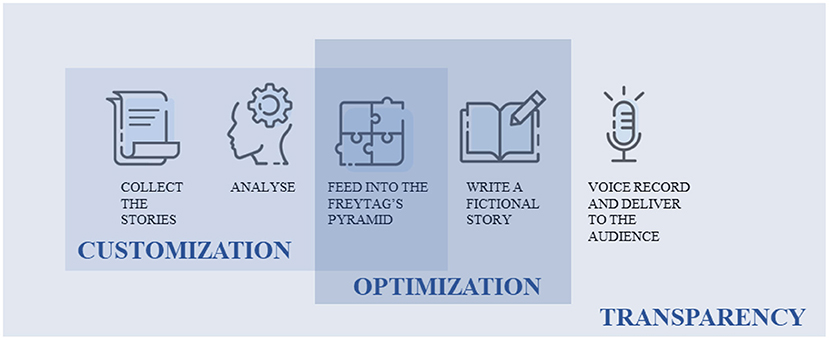

Practically, the technique is implemented by collecting structured interview data, analyzing the collected corpus to form clusters of narrative sub-themes (i.e., target group needs throughout different points in the story) and feeding the themes into the Freytag pyramid (Freytag, 1894) (i.e., the beginning, rising action, climax, etc.) to form a story (see Petrovic et al., 2022). The optimized thematic sequencing provides a model for how to capture–and share–highly personal accounts of the often lonely and unsupported work of caring for others in a domestic setting to a wider population belonging to the same target group (Figure 1).

The TST audio stories were first created for informal caregivers and are currently being pilot-tested. The testing includes pre-post audio exposure assessment of stress levels, meaning in life, sense of coherence, caregiver burden, cognitive emotion regulation, as well as facial emotion expression reading during the audio exposure which is then compared with the baseline neutral facial expression. Besides these measures, diary notes are continuously kept, noting the observed and reported caregiver experience during and after the audio exposure.

Considering the initial application of TST (Petrovic et al., 2022) and the collected diary observations and feedback from the informal caregivers, as well as included literature on digital narratives and narrative mechanisms, we note three important considerations for the application of our technique. Subordinating all our considerations under the fundamental “Primum non-nocere” (i.e., “first, do no harm”) of medical ethics we argue that the TST narratives must be created by considering Contextualization, Optimization, and Transparency (Figure 2).

Contextualization and optimization

In terms of TST contextualization and optimization, the ultimate goal is to shorten the length of narrative exposure while still achieving identification with the protagonist inevitably inducing narrative persuasion which in this sense can be used productively to trigger optimal health behaviors or teach required coping strategies.

With contextualization, we refer to fine-tuning the narrative to the situational circumstances of the target population (e.g., informal care, alcohol abuse etc.) that require improvement. Personal narratives, when compared to non-narratives, trigger stronger inter-subject correlation in regions of the brain associated with motivated, semantic, and social-cognitive processes within the audience (Grall et al., 2021). Therefore, contextualization aims to create a bridge to rapid identification with the protagonist and their narrative arc. This includes built-in narrative themes that serve as cues for empathy and merging, which is a crucial aspect of narrative impact.

The protagonist of a TST story, as a social agent, is the focal point of the story while he/she moves through the sequence of emotional and dramatic events, hopefully capturing and sustaining the attention, hence enabling engagement and identification (Zillmann, 2000; Mar and Oatley, 2008; Grall et al., 2021). Here, identifying with the character is noted as a mechanism “through which audience members experience reception and interpretation of the text from the inside, as if the events were happening to them” (Cohen, 2001, p. 245; Igartua, 2010).

The TST optimization creates a combination of both fiction and non-fiction to make the storytelling efficient and effective. Such combination has been mentioned in literature as a rhetorical anomaly that can occur by coincidence or design, allowing an artifact to be read both as fictional and non-fictional text (Nielsen, 2010; Jacobsen, 2015; Iversen, 2019). This concept has been explored by Iversen (2019) who referred to metanoic reflexivity in textual narratives. However, in terms of TST, the merge of non-fiction and fiction in audio narratives is set by design where non-fiction comes through the themes built in the story (see Petrovic et al., 2022) while fiction comes through the narrative itself. In this sense, the fictionality heightens the reflexivity (Walsh, 2007; Chouliaraki, 2011; Iversen, 2019) while the non-fiction grounds the listener into the proximity of the protagonist to consistently support identification and engagement. Similarly to Iversen's concept of metanoic reflexivity, the crucial effect of TST also lies in the audience's limited interest if something is fictional or not once the narration begins.

Transparency

In our currently ongoing pilot testing of the TST, the participants are not specifically informed whether the story they are listening to is fictional or based on real-life events. And yet, once the narration is over, the participants seem to be more concerned with the protagonists' experiences and feelings expressed in the story than the degree of reality. Interestingly, as noted by Iversen (2019), distinguishing fictional and non-fictional narratives is rarely a conscious activity. In fact, even when the researcher noted that the story just played was fictional, and told of how the story was created, the participants chose to disregard this and simply continued to compare their own experiences as caregivers and compassionately comment on the potential future of the fictional protagonist—this suggests a potent sign of identification.

It can be suggested that the optimization, which was guided by context, potentially led to a disregard for the relative reality of the story. As similarly noted by Walsh (2007) and Iversen (2019) once the audience does not strive to determine the factuality of the content, it experiences fictionalized content as a “form of self-consciousness”. The merging of fiction and reality in the TST caregiver story seems to trigger self-reflection in the participants after the exposure to the audio story. In fact, in our ongoing collection of caregiver diaries based on observations and participants' feedback about the TST audio story, participants consistently make an effort to relate by drawing parallels with their personal lives.

In the TST hierarchy, transparency encompasses contextualization which ultimately determines optimization that in turn dictates the story structure (see Figure 2). More importantly, ensuring that TST carefully and deliberately offers transparency about the methods of context and optimization, is a duty we have toward the audience that is often targeted because of their vulnerability and need for support. Transparency of methodology should also be considered crucial in building a healthy platform for future applications of TST and its potent ability to create identification and attitude change, and thus opportunity to be misused.

Ethical principles for digital storytelling

Our initial observations from the currently ongoing TST pilot trial, as well as included empirical studies and the existing literature, suggest that the potential influence of narratives can be finely tuned to target the emotions and perceptions of the participants through careful contextualization and optimization. We suggest that such a structured delivery of digital storytelling for public engagement has an important place in future communication of health and science-related services.

However, when applying such approaches, we must consider ethical applications and systems in place to overview and track the transparency. Of course, commercial, social, and political interests have always fine-tuned their rhetoric to support specific goals. In our case, however, the content is not an established category, nor can we assume that the audience exposed to stories can have much prior awareness of our method. Fine-tuning user emotions through carefully crafted storytelling techniques could potentially bypass the cognitive system in place to counter-argue or keep distance from a story told. Again, we should note that the audience for TST so far has been selected precisely because they are vulnerable and in need of support.

Therefore, transparency must be noted as a crucial consideration when any type of methodological micro-manipulations is performed in content disseminated. Such transparency can come in the form of a simple label, as seen in product placement (i.e., PP) or a brief announcement in audio content stating that “This content has been adjusted for target populations”. The aim is to ensure that the audience's expectations match that of the content reality.

In this way, we ensure that TST creators take responsibility for the content disseminated, and that distinctive influential techniques for delivering information are properly disclosed. Such initial ethical considerations for digital narratives are just a preparatory step for the future. Following new developments and trends in interactive digital storytelling, we must note that training and utilization of machine learning in the application of such techniques could open new doors to effective and productive public engagement with science. Concurrently, large-scale automation also introduces risks of extensive manipulation using the very same methods developed to help and support those in need.

We must be prepared to anticipate and intercept the abuse of digital mental health techniques that utilize micro-manipulations or have demonstrated effectiveness in influencing the users/viewer's behaviors, for commercial purposes. Furthermore, vast data-privacy breaches, cybersecurity incidents, and common personal data leaks, also mean that influential digital storytelling techniques can be successfully utilized and delivered without directly involving users which would technically constitute the “beyond influence” use. Such use would define deliberate abuse of potent narrative techniques for financial benefit, guiding public opinion or opinion of an individual according to the subjective goals of groups, organizations, or other individuals. In fact, all abuse of narrative techniques that in some way can cause potential damage to the end user should be considered as “beyond influence”. A transdisciplinary approach to ethical guidelines and rules is truly required considering the future use of guided digital storytelling techniques, their transparency, labeling and safety.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary materials, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Funding

This project receives funding from the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No 814072.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Blas, N. D., and Paolini, P. (2013). “Digital storytelling and educational benefits: Evidences from a large-scale project,” in: Transactions on Edutainment X. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer. p. 83–101. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-37919-2_5

Bruner, J. S. (2003). Making Stories: Law, Literature, Life. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Burger, J. M. (1981). Motivational biases in the attribution of responsibility for an accident: a meta-analysis of the defensive-attribution hypothesis. Psychol. Bulletin. 90, 496. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.90.3.496

Busselle, R., and Bilandzic, H. (2008). Fictionality and perceived realism in experiencing stories: A model of narrative comprehension and engagement. Commun. Theor. 18, 255–280. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2885.2008.00322.x

Busselle, R., and Cutietta, N. (2019). “Narrative engagement,” in Communication: Oxford Bibliographies, ed P. Moy (Oxford: Oxford University Press). doi: 10.1093/obo/9780199756841-0223

Carragher, M., Steel, G., Talbot, R., Devane, N., Rose, M. L., and Marshall, J. (2021). Adapting therapy for a new world: storytelling therapy in EVA Park. Aphasiology. 35, 704–729. doi: 10.1080/02687038.2020.1812249

Chouliaraki, L. (2011). ‘Improper distance’: towards a critical account of solidarity as irony. Int J Cult. Stud. 14, 363–381. doi: 10.1177/1367877911403247

Cohen, J. (2001). Defining identification: a theoretical look at the identification of audiences with media characters. Mass Commun. Soc. 4, 245–264. doi: 10.1207/S15327825MCS0403_01

Cohen, J. L., Johnson, J. L., and Orr, P. P. (2015). Video and Filmmaking as Psychotherapy. Abingdon-on-Thames: Taylor and Francis. doi: 10.4324/9781315769851

Costabile, K. A. (2016). Narrative construction, social perceptions, and the situation model. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 42, 589–602. doi: 10.1177/0146167216636627

Dal Cin, S., Zanna, M. P., and Fong, G. T. (2004). Narrative persuasion and overcoming resistance. Resistance Persuas. 2, 4. doi: 10.1037/e633872013-232

Filoteo, J. V., Cox, E. M., Split, M., Gross, M., Culjat, M., and Keene, D. (2018). “July. Evaluation of ReminX as a behavioral intervention for mild to moderate dementia,” in 2018 40th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC). IEEE. p. 3314–3317. doi: 10.1109/EMBC.2018.8513049

Golding, L. (2011). Narrative Impact of Health and Occupational Safety Messages: A Comparison Across Voice, Medium, and Topic (Doctoral dissertation). Athens, GA: University of Georgia.

Grall, C., Tamborini, R., Weber, R., and Schmälzle, R. (2021). Stories collectively engage listeners' brains: Enhanced intersubject correlations during reception of personal narratives. J. Commun. 71, 332–355. doi: 10.1093/joc/jqab004

Green, M. C. (2004). Transportation into narrative worlds: the role of prior knowledge and perceived realism. Discourse Process. 38, 247–266. doi: 10.1207/s15326950dp3802_5

Green, M. C., and Brock, T. C. (2000). The role of transportation in the persuasiveness of public narratives. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 79, 701. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.79.5.701

Habermas, T., and Bluck, S. (2000). Getting a life: the emergence of the life story in adolescence. Psychol. Bull. 126, 748. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.5.748

Igartua, J. J. (2010). Identification With Characters and Narrative Persuasion Through Fictional Feature Films. Berin: Walter de Gruyter. doi: 10.1515/comm.2010.019

Iversen, S. (2019). ‘Just because it isn’t happening here, doesn't mean it isn't happening': narrative, fictionality and reflexivity in humanitarian rhetoric. Eur. J. Engl. Stud. 23, 190–205. doi: 10.1080/13825577.2019.1640432

Jacobsen, L. B. (2015). Vitafiction as a mode of self-fashioning: the Case of Michael J. Fox in “Curb Your Enthusiasm”. Narrative. 23, 252–270. doi: 10.1353/nar.2015.0016

Mar, R. A., and Oatley, K. (2008). The function of fiction is the abstraction and simulation of social experience. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 3, 173–192. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6924.2008.00073.x

McAdams, D. P. (1987). “A life-story model of identity,” in Perspectives in personality. Stamford, CT: JAI Press. p. 15–50.

McAdams, D. P. (1988). Power, Intimacy, and the Life Story: Personological Inquiries into Identity. New York, NY: Guilford press.

McAdams, D. P. (2011). “Narrative identity,” in Handbook of Identity Theory and Research. New York, NY: Springer. p. 99–115. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-7988-9_5

McAdams, D. P., and McLean, K. C. (2013). ‘Narrative identity’, current directions. Psychol. Sci. 22, 233–238. doi: 10.1177/0963721413475622

Nielsen, H. S. (2010). “Natural authors, unnatural narration,” in Postclassical Narratology: Approaches and Analyses. p. 275–301.

Petrovic, M., Bonanno, S., Landoni, M., Ionio, C., Hagedoorn, M., and Gaggioli, A. (2022). Using the transformative storytelling technique to generate empowering narratives for informal caregivers: semistructured interviews, thematic analysis, and method demonstration. JMIR Format. Res. 6, e36405. doi: 10.2196/36405

Petrovic, M., and Gaggioli, A. (2020). Digital mental health tools for caregivers of older adults—a scoping review. Public Health Front. 8, 128. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00128

Petrovic, M., and Gaggioli, A. (2021). The potential of transformative video design for improving caregiver's wellbeing. Health Psychol. Open. 8, p.20551029211009098. doi: 10.1177/20551029211009098

Pillemer, D. B. (1998). Momentous Events, Vivid Memories. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. doi: 10.4159/9780674042155

Ritterfeld, U., and Jin, S. A. (2006). Addressing media stigma for people experiencing mental illness using an entertainment-education strategy. J. Health Psychol. 11, 247–267. doi: 10.1177/1359105306061185

Schmälzle, R., Häcker, F. E., Honey, C. J., and Hasson, U. (2015). Engaged listeners: shared neural processing of powerful political speeches. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 10, 1137–1143. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsu168

Schreiner, C., Appel, M., Isberner, M. B., and Richter, T. (2018). Argument strength and the persuasiveness of stories. Discourse Proc. 55, 371–386. doi: 10.1080/0163853X.2016.1257406

Shen, F., Sheer, V. C., Li, R., and Shen, F. (2015). Impact of narratives on persuasion in health communication: a meta-analysis. J. Advert. 2, 105–113. doi: 10.1080/00913367.2015.1018467

Singer, J. A. (1995). Seeing one's self: locating narrative memory in a framework of personality. J. Pers. 63, 429–457. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1995.tb00502.x

Singer, J. A. (1996). “The story of your life: A process perspective on narrative and emotion in adult development,” in Handbook of Emotion, Adult Development, and Aging. Cambridge, MA: Academic Press. p. 443–463. doi: 10.1016/B978-012464995-8/50025-X

Singer, J. A. (2004). Narrative identity and meaning making across the adult lifespan: an introduction. J. Pers. 72, 437–460. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-3506.2004.00268.x

Singer, J. A., and Conway, M. A. (2011). Reconsidering therapeutic action: loewald, cognitive neuroscience and the integration of memory's duality. Int. J. Psychoanalysis. 92, 1183–1207. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-8315.2011.00415.x

Slater, M. D., and Rouner, D. (2002). Entertainment—education and elaboration likelihood: understanding the processing of narrative persuasion. Commun. Theory. 12, 173–191. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2885.2002.tb00265.x

Slater, M. D., Rouner, D., and Long, M. (2006). Television dramas and support for controversial public policies: effects and mechanisms. J. Commun. 56, 235–252. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.2006.00017.x

Spierling, U., and Szilas, N. (2008). Interactive Storytelling: First Joint International Conference on Interactive Digital Storytelling, ICIDS 2008. Erfurt, Germany: Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-89454-4

Walsh, R. (2007). The Rhetoric of Fictionality: Narrative Theory and the Idea of Fiction. Columbus, OH: The Ohio State University Press.

Walter, N. T., Murphy, S., and Gillig, T.K. (2018). To walk a mile in someone else's shoes: how narratives can change causal attribution through story exploration and character customization. Hum. Commun. Res. 44, 31–57. doi: 10.1093/hcre.12112

Keywords: storytelling, digital narratives, contextualization, optimization, ethics

Citation: Petrovic M, Liedgren J and Gaggioli A (2022) Beyond influence: Contextualization and optimization for new narrative techniques and story-formats. Perspective paper. Front. Commun. 7:915308. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2022.915308

Received: 07 April 2022; Accepted: 17 October 2022;

Published: 04 November 2022.

Edited by:

R. Lyle Skains, Bournemouth University, United KingdomReviewed by:

Andrew Perkis, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, NorwayCopyright © 2022 Petrovic, Liedgren and Gaggioli. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Milica Petrovic, bWlsaWNhLnBldHJvdmljQHVuaWNhdHQuaXQ=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Milica Petrovic

Milica Petrovic Johan Liedgren2†

Johan Liedgren2†