94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Commun., 09 June 2022

Sec. Science and Environmental Communication

Volume 7 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomm.2022.883278

This article is part of the Research TopicLanguage Research on Sustainability, Ecology, and Pro-environmental BehaviorView all 8 articles

Drawing on recent scholarship in environmental communication and rhetoric, this essay examines the role of visual circulation in digital environmental discourse. We argue that while environmental image circulation is often viewed as an ambivalent, or even performative, practice for environmental citizenship, it is also an important space for cultivating participatory culture online. Adapting a version of Laurie Gries' “Iconographic Tracking” method, we offer three case studies that demonstrate how the digital circulation of environmental memes and iconic images offers important tactics for engaging digital publics that can be deployed by public communication practitioners. Subsequently, we argue for a more nuanced view of image circulation as both a performative and a participatory strategy for environmental communication.

On March 23rd, 2021, a container ship called the Ever Given ran aground in the Suez Canal, causing a total obstruction that would completely halt all traffic for 6 days and affect shipping worldwide. The event epitomized the overlapping crises that characterized 2020—including climate change, social justice, and the COVID-19 pandemic—as it represented ways that, as Farhana Sultana puts it, “climate change amplifies, compounds, and creates new forms of injustices and stresses, all of which are interlinked and interconnected” (Sultana, 2021, p. 447). Global manufacturing shortages and supply chain breakdown, issues already exacerbated by the impacts of the pandemic, were compounded by the disaster. Soon after the news broke, images of the Ever Given began to circulate across social media sites, rapidly becoming a series of memes depicting various and intersecting breakdowns in global circulation. Out of the many different memes which circulated, the image of a lone backhoe attempting to dig out the massive container ship (Figure 1) emerged as one of the most popular and iconic, being used to represent everything from shortages of goods and energy, to systemic inequality, to the struggles of maintaining mental health in quarantine.

Figure 1. A meme portraying a container ship called the Ever Given, which ran aground in the Suez Canal. The image was posted to Twitter on March 25, 2021 with the words “I made this. It's for you” (Streckert, 2021).

This meme is a compelling example not only of how images can help communicate complex issues, such as the intersecting socio-ecological concerns presented by the pandemic but also of how digital circulation is an increasingly important tool for networked communication.

Visual media have always played an important role in the emergence and development of the American environmental movement, dating back to the field notes and drawings that would become William Bartram's Travels (Sivils, 2004) and the work of Frederick E. Clements and Henry Cowles which increasingly relied on visual abstraction to replace the physical experience of field work (Walsh and Prelli, 2017). While photographs replaced the experience of “being there,” they also inspired public imagination. From the 1960s through the 1980s, rhetorically compelling photographs of the earth from space, satellite imaging of the surface of the earth, and visualizations of the ozone hole all helped catalyze a public environmental imagination (Jones, 2019). In Seeing Green: The Use and Abuse of American Environmental Images, Finis Dunaway traces the visual history of American environmentalism, establishing the myriad ways that environmental images from photographs to complex visualizations have been used not only to make scientific information “visible” to the public but also to obscure responsibility for our environmental crisis (Dunaway, 2015). For the American environmental movement, images have long been both a dynamic and a dubious means of communication, mediation, and engagement with the public. For instance, DeLuca and Demo (2000) discuss the significant role that the landscape photography of Carleton Watkins played in the early formation of environmental protection. Through their study they demonstrate how “images [are] integral to politics” as both “political rhetoric and popular culture” and in “constituting the context within which a politics takes place” (241–242). Specifically, they demonstrate how “the pristine image of Yosemite Valley quickly became iconic of an American vision of nature itself” (241–242), and in communicating a pristine vision of sublime nature, these images participated in “creating a reality” for American environmental discourse (242). That is, visual representations of natural environments directly participate in the construction of the cultural image of nature.

In more recent years, scholars have begun to investigate impacts of the myriad ways that visualizations portray, influence, and mediate large-scale environmental problems like climate change (O'Neill and Nicholson-Cole, 2009) and discuss how certain visual tropes have come to dominate environmental discourse (O'Neill and Smith, 2014). Along similar lines, Dobrin and Morey's (2009) collection Ecosee discuss the ways that visual tropes participate in the rhetoric of environmental icons. Morey (2014) defines “econs” or “ecotypes” as “environmental images that become iconic across mass audiences and symbolic of environmental issues and situations beyond any econ's individual species concerns” (1). Memes are powerful tools for indexing, or “pointing and naming,” different topoi through the circulation and transformation of tropes (Milstein, 2011). These tropes help to spread environmental perspectives across a wide range of audiences, but these popular tropes can also make it difficult to see the situation clearly. For example, Born (2019) has recently investigated how polar bears became contemporary “icons of climate change” by participating “within a visual discourse embedded in a particular cultural and political context” (650). Born demonstrates how the iconic image of a polar bear on a melting sheet of ice is both a powerful emotional and visual trope, but that its power can also obscure “social and political complexities” which “makes imagining fundamental systemic changes that much harder” (660). In other words, images can help to carry environmental messages to a large number of people, but they also risk flattening those messages as they traverse those wider communication networks. Building from these scholars, this study examines how visual media offers new ways to make ecological issues visible in social networks by examining iconic environmental images and memes as they circulate online.

Over the last few decades, rhetoric and writing studies have broadly seen overlapping turns toward understanding distributed models of communication (Edbauer, 2005). This shift has brought renewed interest in the rhetorical canon of delivery (Trimbur, 2000) and in the affective dimensions of information flow (Lotier, 2018) coalescing under the banner of circulation studies (such as Hawk, 2007; Brooke, 2009; Ridolfo and DeVoss, 2009; Eyman, 2015; Gries, 2015, 2016, 2017). At the same time, scholars interested in the rhetoric of science, technology, and medicine (RSTM) have begun to outline the importance of interdisciplinary environmental communication research (Cagle and Tillery, 2015), trace the rhetorical dimensions of visualizations (Olman and DeVasto, 2020) and the use of other digital media in science and environmental communication (Cagle, 2021). At the same time, scholars have begun to investigate the connections between scholarship in memetics and digital rhetoric with “everyday digital users” (Sparby, 2022). Rather than defining memes solely as image macros, Sparby deploys the term “memetic screen” to describe “the ways in which users and their experiences cause them to see and create the world in specific ways through the memes they encounter, create, circulate, and recirculate” (6). These screens better account for the multimodal dimensions of images and text as they circulate online. Memetics offer a more dynamic range of engagements with the ways that images participate in larger cultural discourses as they transform and circulate.

Because of the complex and convoluted history of visuals in American environmentalism, sharing memes and images online is sometimes dismissed as an empty or “performative” gesture (Woods and Hahner, 2019). Yet, numerous scholars of rhetoric, communication, and new media demonstrate that image circulation plays a more complex, if not ambivalent, part in digital discourse. In Gestures of Concern, Chris Ingraham (re)defines rhetorical gestures as “efforts people make to join in public affairs in ways that feel participatory and beneficial, though their measurable impact remains imperceptible” (Ingraham, 2020, 1). Ingraham goes beyond these relentlessly negative views to define gestures as “an expression into form of an affective relation,” and “an expressive concern that acts as both a means and as an end because their most instrumental effects are exhausted in their expressivity” (1). These rhetorical moves, he argues, contain the possibility of social transformation. In other words, these gestures offer important ways to perform and participate in social and political change in meaningful ways, even when they risk performativity. As such, gestures are a necessary part of sustaining a participatory culture and mobilizing networked publics in a digital age (Papacharissi, 2015).

Along these lines, we understand the rhetorical work of image circulation, such as with environmental memes, as a form of “strategic gesture,” which Peter Bsumek and his co-authors define as “a rhetorical assemblage of movements, actions, and performances that are intended to generate effects larger than a sum of individual or particular acts in systems of power” (5, emphasis removed). They argue that, as opposed to “empty gestures,” they are “a discursive innovation that is oriented not toward deliberation, but toward articulation and mobilization of loosely networked local publics” and are a “productive mode for enabling networked publics and generating counterpublicity” (11). The circulation of environmental memes offers important participatory strategies for engaging digital publics and counterpublics in environmental communication. In a recent study, Hautea et al. (2021) discuss how TikTok videos “contribute to and reify global climate messaging” (1). Building from Papacharissi's (2015) conception of “affective publics,” they discuss memetic power as “sustained by the structures in which they are situated” (5). As such, they demonstrate how TikTok allows “non-expert users [to] visibly intervene in a discussion that generally takes place among expert-level scientists and journalists: the question of how serious a problem climate change is and what to do about it” (12). As social media continues to play a pivotal role in the changing environments through which the public communicates, memes are an increasingly important element of public advocacy and communication. In recent years, a growing number of scholars have begun to examine the important ways that memes mediate environmental discourse. Ross and Rivers (2019) argue that through “the use of common meme templates combined with the typical humorous or ironic message they convey, Internet memes represent a potentially powerful form of socio-political participation in the online community” (975). Along these same lines, one recent study suggests a connection between exposure to climate change memes and participation in online activism (Zhang and Pinto, 2021), while one examines how memes can participate in environmental culture jamming (Davis et al., 2015), and another suggests that “visual style” played an essential role in the 2009 Climategate controversy and in shaping public understanding of climate change (Greenwalt and Hallsby, 2021). Visuals have also been shown to increase the efficacy of environmental messaging (Meijers et al., 2019). Other studies suggest that memes serve an important role as “memory actants” which “influence not only the content of public memory but also the attitudes with which we remember that content” (Silvestri, 2018).

While taken together, these studies demonstrate the significance of environmental memes in cultivating participatory online discourse, fewer studies acknowledge the critical role that circulation plays in making environmental memes matter. In the following sections, we discuss our investigation of the visual circulation of environmental memes through three case studies based on an adaptation of Gries' iconographic tracking method. We build from this growing area of interest to report findings from an image tracking project that focuses on how environmental memes circulate and shape environmental communication. Through three case studies based on an assignment in an interdisciplinary graduate course on visual rhetoric and environmental communication, we share insights about how image circulation affects digital environmental communication. The course broadly approached environmental communication and public advocacy through theories and methods proffered by scholars of visual/digital rhetoric and environmental communication. Following a more traditional rhetorical analysis of a piece of visual media, students were tasked with using a variation of Laurie Gries' iconographic tracking method to study the circulation of an iconic image or viral meme related to scientific or environmental communication and to discuss findings in a scientific research report. We would like to note that these studies have a focus on American environmental discourse, but we see significant research potential in similar studies expanding this focus outside US and American culture. Our case studies summarize individual reports and discuss examples of how image circulation mediates environmental discourse across social networks. We conclude by discussing the implications of our study for science and environmental communication scholarship at the nexus of visual rhetoric and digital circulation studies.

As images circulate, they participate in the complex ecologies of public rhetoric (Edbauer, 2005; Rivers and Weber, 2011). In this project, we tracked iconic images as they circulated online using Gries's (2013) iconographic tracking methods to collect and analyze environmental images and memes. Iconographic tracking allows circulation studies researchers to account for the changes in use and sharing of images as they are shared across social media and websites—also known as “rhetorical velocity” (Ridolfo and DeVoss, 2009). Across several essays and a monograph (2013, 2015, 2016, 2017), Gries presents a decade of research on the circulation of a single iconic digital artifact, the “Obama Hope” image. By tracing the “Hope” image's circulation and transformations, Gries's (2013) framework for visual tracking understands the circulation of images as “non-linear, divergent, and unpredictable flows” (344). Gries focuses primarily on developing methodologies for understanding rhetorical velocity in visual rhetoric more broadly, and other scholars have applied this framework to study how image circulation shapes public understanding of global environmental problems, from the relationship between local media coverage of sinkholes and public understanding of global environmental disasters (Greene, 2015) to an online selfie campaign as a form of environmental risk communication (Pflugfelder, 2019).

Each of the case studies explored in this paper deploys methods proposed by Gries in order to understand the ways that environmental images are transformed and circulated in networked discourse. Through iconographic tracking, we assessed a variety of revisions and transformations for the images as they circulated, and then saved and categorized those images for later analysis. We tracked different kinds of visuals, from memes to popular photographs to iconic symbols. Researchers collected data primarily by using various search engines in concert with Zotero, a data management platform, as well as Google Trends, TinEye, and Google Image Search, and social media sites such as Instagram, TikTok, Facebook, Twitter, Reddit, and Pinterest. In Zotero, we organized images into folders based on topologies of circulation (such as media, marketing, humor, activism, etc.) and categorized them with tags based on relevant themes. After compiling the folders, topoi were analyzed to identify trends within findings. Using Google Trends, we examined the spatial and temporal patterns in each individual image's circulation and explored related search terms. We also contextualized “spikes” in search activity from Google Trends by cross-referencing these search hits with current events and social media. Iconographic tracking thus allowed us to reference the dynamic unfolding and contributions the images have made as they participate in public environmental discourse.

In addition to utilizing Gries' iconographic tracking methods, we also utilize rhetorical analysis in “reading” the images for subtle changes to how they may be perceived by the audience, and for considering the many potential valences afforded by the various remixes produced by the internet populace and social media communities. Analogous to close reading methods, we see this as serving a similar function to the genre-related work that Gries conducts when categorizing images related to particular icons. However, since we only focus on a single genre in this article—environmental iconography—we found rhetorical analysis to be an effective replacement for considering quasi-categorical changes to the icons that compromise the cases of interest for this article. While we have augmented Gries methods to fit a uniform genre analysis, any strong delineations between rhetorical analysis and genre analysis would be difficult to defend. As such, we see significant future potential in augmenting Gries' methods with other research methodologies.

Since the publication of Dr. Seuss's The Lorax in 1971, the book's titular character has become an icon and has been remixed over time, across genres, and been interpreted through numerous lenses. Many of Dr. Seuss's characters remain culturally relevant, but none more than the Lorax, who plays a prominent role in environmentalist subculture. The Lorax is an environmental icon for its ability to stand alone and be recognized as an environmental message. Since its initial publication, there have been more than 200 million copies sold, the illustration has circulated through numerous media, including protest signs, t-shirts, and a 2012 Universal Pictures animated movie (Dailey, 2012). The original illustration and meme renditions remain dominant in many subcultures today.

Written one year after the first Earth Day in 1970 and at the beginning of the environmental movement, The Lorax provided several takeaway messages for a budding environmentalism. Dr. Seuss painted the fictional world of Thneedville with words and images of fertile land with thriving ecosystems and smiling animals that starkly contrasts the antagonists, the Once-ler's, desire for profit that eventually leaves the land dark and barren. Warnings of a post-apocalyptic world, messages on environmental degradation, a nod toward the dangers of capitalism, and an individual character with determination to save trees are interwoven through the book. Environmentalists identify with the Lorax's representation of being an environmental crusader. The Lorax is met with resistance and stubbornness from the Once-ler just as today's environmentalists are met with resistance from corporations and capitalism. The Lorax, representing today's activist fighting against corporations, is captured perfectly in the political image of the Lorax wearing a t-shirt of Exxon, Pepsico, and Doritos, common corporations that environmentalists identify as the antagonist.

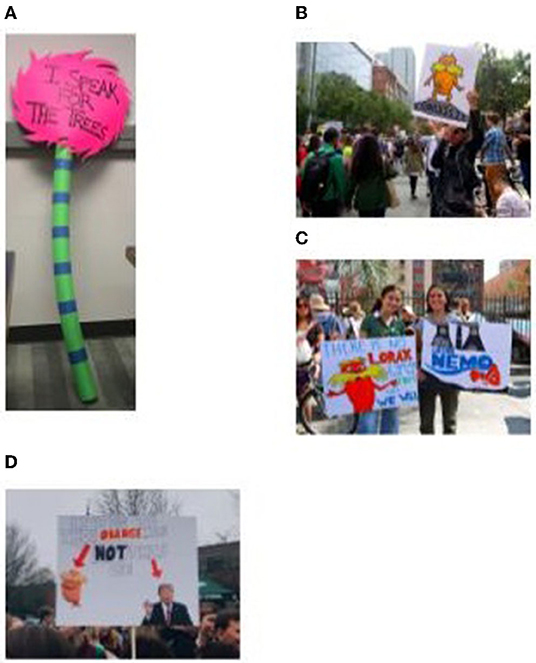

Environmentalists have taken to the streets with force with the Lorax held high above their heads on protest signs. A sign in the shape of a single truffula tree (Figure 2A) points to the famous line from The Lorax and shows how a mere few words can make a potent statement. Similarly, a protester holds up a hand-drawn sign with an image of the Lorax with the word “UNLESS.” The simplicity of this sign invites us to recall another famous line “Unless someone like you cares a whole awful lot, nothing is going to get better. It's not” (Figure 2B). Another protest sign says “There is no Lorax 2 speak for the trees so… We Will” (Figure 2C). These signs show how well-understood and widely known the Lorax is as he delivers a message with little context. Across all of the signs, whether hand-drawn or clipped from the animation, the Lorax's orange color stands strong. In one sign, the Lorax is compared to Donald Trump (Figure 2D). This sign refers to Donald Trump's orange coloration from his excessive use of self-tanner and suggests that we listen to the Lorax, another orange figure, instead of Trump. This political sign appeals to environmental politics while criticizing Trump for his use of cosmetics by indexing the two through ethos, ultimately claiming that a fictional character is more trustworthy than the president.

Figure 2. The Lorax protests and posters. (A) Truffula Tree Sign (Schuenemann, n.d.). (B) FUnless sign (Daretoeatapeach, 2017). (C) Lorax and Nemo Poster (Salinas, 2019). (D) Trump Poster (Funny Video Memes, Funny Memes, Good Jokes, n.d.).

Images and quotes from The Lorax have been transformed into t-shirts (Figure 3A), buttons (Figure 3B), and even tattoos. These paraphernalia and permanent body markings show that Lorax is here to be heard on many more occasions than just at a rally. Wearing the Lorax also shows the significance of the character and its message to the environmentalist as they are willing to let it be portrayed on their physical identity as clothing temporarily, or as a tattoo forever. The performative nature of the Lorax does not seem to have bounds.

Figure 3. The Lorax paraphernalia. (A) T-shirt design with the Lorax (https://newgraphictees.com/product/i-am-the-lorax-i-speak-for-the-trees-t-shirt/)1. (B) I speak for the trees button (https://www.hakes.com/Auction/ItemDetail/79599/DR-SEUSS-DESIGNED-RARE-I-SPEAK-FOR-THE-TREES-ECOLOGY-THEMED-BUTTON-FEATURING-THE-LORAX)2.

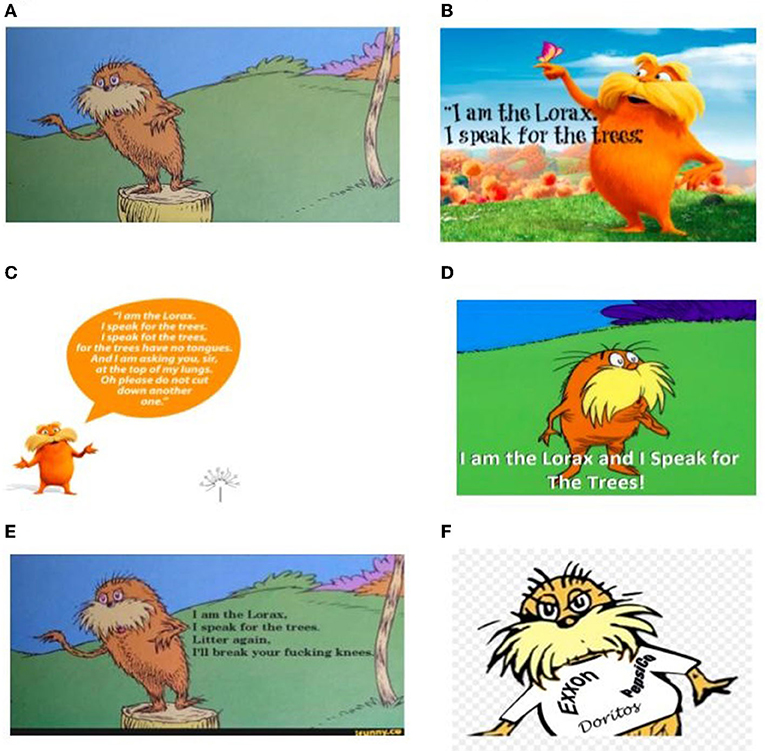

The original illustration (Figure 4A) was published in the book. The 2012 animation (Figure 4B) and the Lorax television show (Figure 4C) characters have been modified with advanced illustration technology. Across all versions there is room for interpretation of what the Lorax could be saying, and it is often remixed with words placed in the background behind him to connect his presence with a thought or speech bubble. The original illustration appears remixed more frequently in memes, signs, and other paraphernalia than the 2012 animation and the television character.

Figure 4. Lorax characters. (A) Original illustration (Kimmel, 2019). (B) 2012 animation (Morye, 2020). (C) Animation with quote (https://www.pinterest.com/pin/428053139554374889/)3. (D) TV Cartoon Lorax (https://imgur.com/gallery/9pvVx1w)4. (E) Original illustration with text (https://www.pinterest.co.kr/pin/627055948099310315/?amp_client_id=CLIENT_ID(_)&mweb_unauth_id=&from_amp_pin_page=true)5. (F) Lorax wearing t-shirt (https://www.pinclipart.com/pindetail/ibTTbih_the-lorax-youtube-clip-art-lorax-dr-seuss/)6.

Some popular memes took advantage of overlaying text on the screen to remix what the Lorax was saying with a more vulgar rendition. One of the most popular memes uses the same rhyme structure that Dr. Seuss is famous for and changes the second line from “for the trees have no tongues. And I am asking you, sir, at the top of my lungs. Oh please do not cut down another one.” to “Litter again, I'll break your fucking knees” (Figure 4E). Political caricature renditions of the Lorax have been made that exaggerate the Lorax beyond his original environmental iconography. The remixes that make the Lorax political also enable the Lorax to be a very popular sign among protestors. From the quotes “I speak for the trees” and “Unless someone like you cares a whole awful lot, nothing is going to get better. It's not.” to the truffula tree, to a simple Lorax character, to a comparison of the Lorax to Donald Trump (Figure 2D), there is a plethora of the Lorax being used to be a call to action. The Lorax has also been used for a variety of paraphernalia including t-shirts (Figure 3A), buttons (Figure 3B), and tattoos. Most of this paraphernalia includes a near approximation of the original Lorax and his sayings rather than a remixed or meme version.

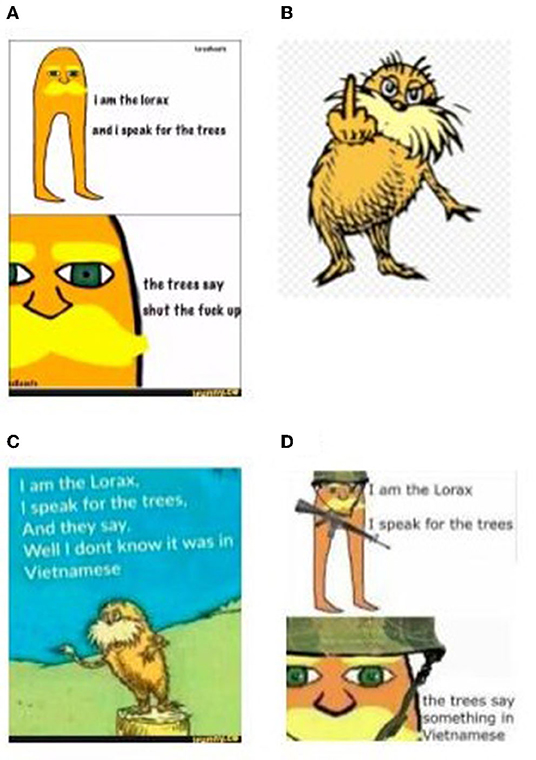

Beyond these popular parodies, other memes include a simple image of the Lorax that is identifiable by his orange color and yellow mustache (Figure 5A). These memes employ the same strategy of adding text next to the character to imply what the Lorax is saying. Another remixed meme of the Lorax shows the Lorax giving a middle finger (Figure 5B). Another popular meme was first developed by substituting text that says “and they say, well I do not know it was in Vietnamese” (Figure 5C). This meme has since been modified to still resemble the Lorax at the most basic level with the orange body and yellow mustache but adding military apparel and guns (Figure 5D). Among the most popular uses of the Lorax, the image associated with the phrase “I speak for the trees” brings up over 200,000 Google search results. The Google Trend search for “I speak for the trees,” “Lorax,” and “truffula” spiked in March of 2012, upon the release of the film, and gained traction steadily from 2015, peaking in the spring of each year around Earth Day.

Figure 5. Other memes. (A) Simplified Meme (https://knowyourmeme.com/photos/1038793-i-am-the-lorax-i-speak-for-the-trees)7. (B) Middle Finger Meme (https://www.pngkin.com/pen/hbmbow/)8. (C) Vietnam book meme (https://www.pinterest.com/pin/640074165772706245/)9. (D) Vietnamese military meme (https://www.pinterest.com/pin/819936675887264406/)10.

The original illustration of the Lorax tends to be the most commonly used in circulation and across remixes, followed by the 2012 animation image. However, since 2012, there has been a growing number of renditions of the animated character over the original. A newer iteration of the Lorax, the most simplified yet, consists of a simple-shape, orange body and minimal feature. It is used most commonly in satirical memes (Figure 5A). This is a common meme strategy-amplify how iconic a character is by stripping it to its most basic features.

This remix became a popular meme on Pinterest and Reddit with the added text “Litter again, I'll break your fucking knees” (Figure 4E). This meme adds a vulgar, threatening rhyme to employ the same call to action. As environmentalists have felt unheard since the start of the movement, this meme captures their anger and the threatening tone they wish was effective to enact political change. Contrary to the message-driven tone in the original book, this meme targets individual acts of littering instead of large corporations.

Another meme that is only suitable for adults remixed the Lorax to give the middle finger (Figure 5B). This “f-you” can be inferred as what the trees may be saying to the Once-ler for cutting them down and can be used today to relay the same message to corporations. A grouping of memes has cut down the Lorax character to a simple body that is only recognizable because it has been crafted with the same orange color and yellow mustache (Figure 5A). These parodies of the Lorax take on a more satirical and vulgar tone as they poke fun at the original saying “I speak for the trees” by adding “the trees say shut the fuck up.” Unlike the middle finger meme, this meme claims that the trees do not care about being spoken for and wish that the Lorax quiets himself.

In a publication for Nature, Emma Marris described the Lorax character as a “parody of a misanthropic ecologist,” meaning that his unsocial and reclusive nature was what led him to be unsuccessful (Marris, 2011). Similarly, the Lorax matches the criticisms of being an alarmist and anti-progress. The Once-ler describes the Lorax as “shortish and oldish and sharpish and bossy” (GradeSaver, 2021). Since environmentalists identify themselves with the Lorax, they can be easily mocked with these same criticisms. Many environmentalists are also criticized for being “woo-woo” or “hippie.” The Lorax comes in and out of a tree and is illustrated and animated with lightning bolts around him as if he has some sort of spiritual authority (GradeSaver, 2021). This plays into commonplace critiques of environmentalism as being rooted in a false spirituality.

Other memes point to unexpected places like war history. The memes that remix the Lorax to be saying “Well I don't know it was in Vietnamese” and “the trees say something in Vietnamese” are references to the Vietnam War, when American soldiers often claimed they could hear the jungle speak Vietnamese as the soldiers were about to attack (u/paradoX1995, 2019; see Figures 5C,D). Visually, this reference to the Vietnam War has been made in the original illustration with the addition of text and the crudely drawn figure of the Lorax with the addition of a helmet and machine gun. These memes merge the two ideas of what the Lorax hears from the trees and how Vietnamese soldiers would hide in the trees before an ambush during the war. The analysis of this meme has gone beyond a war history meme and into ecofascism. Ecofascism is a political ideology where the community advocates to decrease the world's population to avoid environmental disasters (Krzeminski, 2019). Whether or not this was the illustrator's original intention, this meme is successful within the community of ecofascists because it reflects the success of the Vietnamese soldiers by killing Americans and dwindling the population. This meme now brings the Lorax into a dark side of environmentalism subcultures.

Dr. Seuss is facing recent criticisms of racist and insensitive imagery that portrays people in hurtful ways as his work has been under a critical lens for the way he portrays Blacks, Asians, and other minoritized/marginalized communities. With these growing critiques of Dr. Seuss's work, books are being pulled from the shelves of schools and removed from murals (Pratt, 2021). This removal and cancelation of Dr. Seuss's work could lead to an unknown future of the Lorax as an environmental icon. Since the meme exists within the world of environmentalists who often overlap with those of social justice communities, it is unclear if the Lorax visual and memes will still succeed. From our analysis of the Lorax through iconographic tracking thus far we understand how a children's book character can become so prevalent in popular culture today and this same method will enable us to investigate how the Lorax will circulate in the future.

Katsuhika Hokusai's Great Wave off Kanagawa, published sometime between 1829 and 1833, is arguably one of the world's most iconic works of Japanese art (Abeza, 2020; Couldwell, 2021). Owing to its popularity, the woodblock print has been distributed and remixed countless times in seemingly infinite forms. A quick Google search of “Great Wave off Kanagawa,” for instance, yields over three million hits—most of which simply reproduce the Wave into consumer products without modification. And yet, many of these search hits include creative works that re-envision and remix Hokusai's print into new and fascinating contexts, both drawing upon and diverging from the original's form and focus.

Notably, through these remixes Great Wave has become associated with notions of environmental disaster and anthropogenic crisis, while also becoming a call-to-arms to address critical environmental issues. We begin this case study with a brief discussion of the history and composition behind Hokusai's Great Wave—a discussion, we hope, will provide context for understanding how and why the print became so popular. We then explore several intriguing remixes of Great Wave that associate the wave itself with notions of monstrosity, disaster, and, more broadly, environmental crisis.

Great Wave off Kanagawa is a part of Hokusai's larger series of prints, Thirty-six View of Mount Fuji (1832), that depict pastoral Japanese life. These prints—or ukiyo-e (literally, “picture[s] of the floating world”)—used carved wooden blocks to print the design onto silk or paper. Great Wave is arguably the most well-known of Hokusai's Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji (and his works in general). Unlike many conventional ukiyo-e, including Hokusai's own prior works, Great Wave and Thirty-six Views depict Japanese daily life across various social classes—rather than the typical portraits of sex workers and kabuki actors (Abeza, 2020). Great Wave also deviates from contemporary ukiyo-e in its use of Prussian blue, a European pigment (Abeza, 2020; Couldwell, 2021). Though Japan did not formally open its ports to international trade until 1859, Great Wave's use of Prussian blue nonetheless implies foreign trade and influence (Abeza, 2020; Couldwell, 2021). Great Wave, then, evokes ideas of change and uncertainty—in new subjects and media in ukiyo-e and more broadly in Japanese society as it was newly inundated with foreign influence.

But inevitable change, symbolized by the wave and ocean as a “defensive boundary and the medium through which Japan…experience[s] the world” (Abeza, 2020), need not be a story of impending doom and destruction of the Japanese way of life. Instead, reading the print from right to left (as Hokusai perhaps intended), the “disciplined brace” of the fishermen (RisingSunPrints, 2020) suggests the fortitude needed to weather the storm. The appearance of Mount Fuji, another symbol of Japanese identity and strength, in Great Wave and throughout Thirty-six Views serves as another reassuring Japanese presence. Taken within its own contemporary context, Hokusai's Great Wave reflects ongoing artistic and social change, but also resilience in face of uncertainty. It is no wonder, then, that Great Wave would remain a popular image that has circulated globally. As we will see in subsequent sections, these historical themes of change and resilience echo in contemporary remixes of Great Wave.

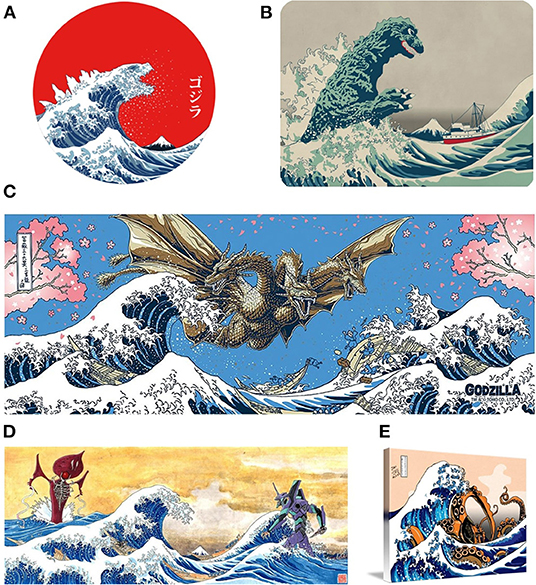

Nestled amid the t-shirts, posters, even a backpack and a mural on an apartment complex—amidst the countless commercial reproductions of Great Wave—monstrous forms rear their scaly heads. In one, the Wave's iconic crest grades into Godzilla's11 equally iconic, gaping, reptilian jaws (Figure 6A; Mottura, 2016). Another remix imagines a more traditional rendition of Godzilla rising out of the sea, seemingly threatening a fishing trawler (Figure 6B; TheDailyRobot, n.d.). In other remixes, monsters do not replace Hokusai's Wave entirely but instead emerge from the roiling waters (Figures 6C–E; Chosetec User Profile, 2010; Mudge, 2014; The Great Wave Off Kanagawa Ghidorah Merchandise From The Godzilla Store, 2019).

Figure 6. The monstrous and fantastical in remixes of Hokusai's Great Wave off Kanagawa. (A) Mottura (2016) t-shirt design featuring a modern version of Godzilla. (B) Pinterest remix (original Etsy listing unavailable) showcasing a more classical version of Godzilla (TheDailyRobot). (C) Godzilla's equally (in)famous rival, Ghidorah, soars over the Great Wave (The Great Wave Off Kanagawa Ghidorah Merchandise From The Godzilla Store, 2019). (D) Neon Genesis Evangelion's EVA-01 battles an Angel amidst Hokusai's Great Wave (Chosetec User Profile, 2010). (E) A kraken's tentacles flail out of the water as Hokusai's Great Wave crashes down (Mudge, 2014).

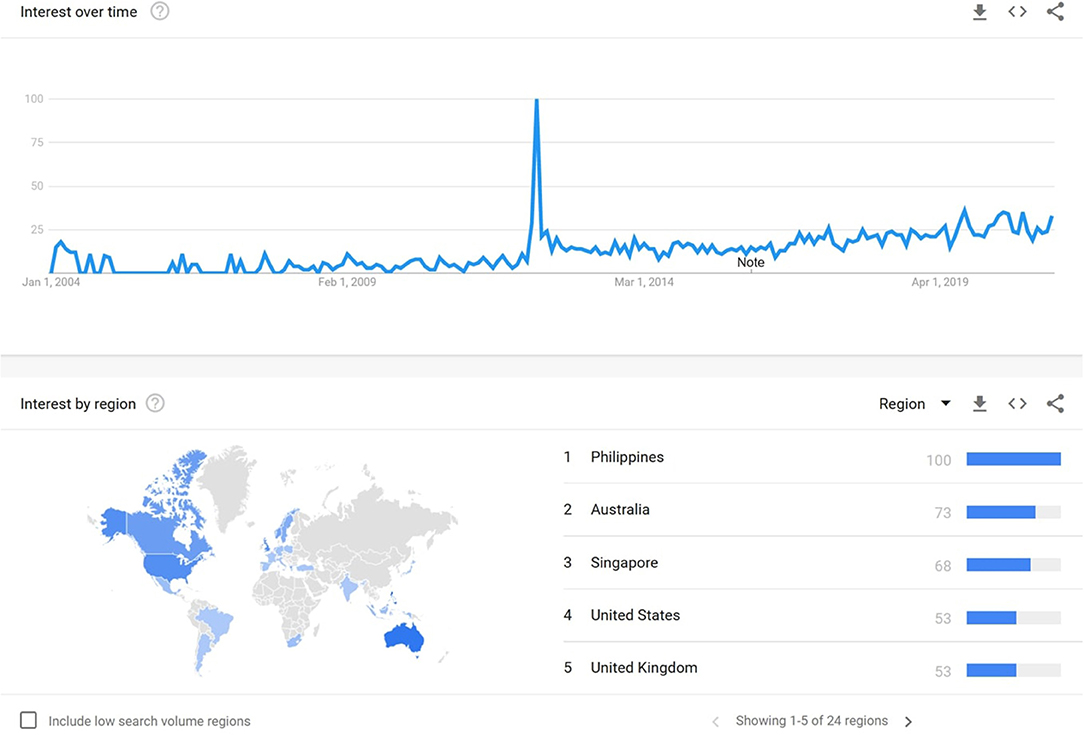

What these remixes (and countless others) share is that they play off the destructive power of water to reimagine Hokusai's Great Wave as something monstrous and catastrophic. Indeed, search activity around the Great Wave has often spiked following major disasters, and the search term, “Great Wave off Kanagawa” is most popular in earthquake- and tsunami-prone areas (Figure 7; Google Trends, 2021). For instance, search activity spiked following a magnitude 9.1–9.3 earthquake in the Indian Ocean that generated 10-m-high tsunami waves (Wikipedia, 2021a). A larger search spike occurred in May 2012, coinciding with several disaster-related events. In April and May 2012, Tropical Depression 17F occurred in Fiji, while in Indonesia there was a magnitude 8.6 earthquake and tsunami warning (Wikipedia, 2018a,b). Though several studies have demonstrated Great Wave is more likely a rogue wave than a tsunami (Cartwright and Nakamura, 2009; Dudley and Dias, 2013), these search results nonetheless suggest that the woodblock print has become associated with natural disasters.

Figure 7. “Great Wave off Kanagawa” search activity since 2004 (Google Trends, 2021).

Two interesting points arise out of this observation. First, while we cannot deny the dual nature of water—at times life-giving, at times destructive—the direction in which we view Hokusai's Great Wave changes how this duality is evoked. Reading from left-to-right, “our eye runs across the crest of the wave down toward the boats with a sense of downward crashing motion” (RisingSunPrints, 2020). In other words, from one direction we feel a sense of impending doom that speaks to the destructive power of water. In that sense, then, it is perhaps no surprise that the Great Wave has become associated with ideas of disaster. And yet, because we can read the image from right-to-left—as Hokusai perhaps intended—we can instead “identify more with the boatmen as our eye rolls down the smaller undulating wave” (RisingSunPrints, 2020). Here, Great Wave evokes a second intriguing duality that complements its association with disaster and with monstrous forms—a duality that might be better posed as a question: Is Great Wave human- or nature-centric? With whom do we “identify” more, the boatmen, as is suggested by a right-to-left reading, or the wave itself (and by extension, the monstrous forms in its remixes)? While these answers are likely subjective and experiential, the dualities presented in Great Wave and its remixes raise broader questions of human-nature relationships. As we will see, the circulation and recirculation of Great Wave seem intimately tied to perceptions of our role in the environment and, broadly, the Anthropocene.

Thus far, we have discussed Great Wave and its monstrous remixes by considering its association with “natural” disasters—i.e., non-human-caused phenomena such as earthquakes and tsunamis. However, we would be remiss in showing Godzilla-themed remixes of Great Wave (Figures 6A,B) without discussing Godzilla's own association with nuclear anxiety in Japan (Napier, 1993)—an anxiety created by a strictly human-caused disaster (i.e., the U.S. atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki). Just as Great Wave blurs the dualities surrounding water and human-nature relations, we will see that many of its remixes blur the distinction between natural and human-caused disasters.

Godzilla is undoubtedly a symbol of Japanese nuclear anxieties and more generally speaks to the dangers of science–or perhaps, runaway scientific progress. Canonically, the dinosaur-like monster was born from American nuclear testing in the Pacific. Though Godzilla “demonizes American nuclear science in an obvious reference to the atomic tragedies of Hiroshima and Nagasaki,” it also resonated with Americans' own nuclear anxieties by presenting them as something monstrous and “alien” (Napier, 1993). Napier, quoting Andrew Tudor, writes that Godzilla belongs to the genre of “secure horror,” wherein the “collectivity” (e.g., society) is threatened by some external entity, but is ultimately saved by a scientific and governmental (i.e., human) intervention (Napier, 1993).

What can these historical and cultural insights from Godzilla reveal to us with regard to Great Wave? First, Godzilla, and its remix into Great Wave (Figures 6A,B), blurs what we would like to be a clear distinction between “natural” and “human-caused” disasters. Earthquakes and tsunamis themselves are caused by physical processes. Conversely, the atomic tragedies that befell Japan were caused by human processes. Yet Godzilla is at once natural and anthropogenic. Though Godzilla supposedly had humble origins as a lizard living on a remote, Pacific island, it was human intervention—American atomic testing and subsequent radiation—that granted its monstrous, destructive form. Paradoxically still, if Godzilla belongs to the genre of “secure horror,” then it is an “alien” that exists outside the “collectivity” (Napier, 1993)—in other words, it is relegated to (or rationalized as) an external, antagonistic entity. What are we to make, then, of a Godzilla that emerges from (Figure 6B) or is literally part of (Figure 1) Hokusai's Great Wave? How do we reconcile this notion of simultaneously “natural” and “human-caused” disaster?

To answer these questions, let us turn to yet another remix of Great Wave—that of French cartoonist, Jean “Plantu” Plantureux, who depicted the Great Wave bearing down on a nuclear reactor (Figure 8; reproduced from RidolfoFigure 4 in Helmreich, 2015)12. Dated March 15, 2011, this remix is an obvious nod to the Fukushima disaster—yet another nuclear tragedy that Japan suffered. The cooling tower of Fukushima Daiichi's Nuclear Power Plant replaces the image of Mount Fuji in Hokusai's original Great Wave and is perhaps an ominous allusion to the loss of Japanese identity and strength (Abeza, 2020). Moreover, Plantu's remix overtly echoes the nuclear anxieties evoked by Godzilla and other monstrous remixes of Great Wave (Figure 6), by depicting a Japan at once threatened by both a tsunami and nuclear meltdown.

Figure 8. Jean “Plantu” Plantureaux's remix of Great Wave in the wake of the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster. © Plantu, dessin paru dans Le Monde du 15 mars 2011 Autorisation à titre gracieux. Reproduced from Helmreich (2015).

Like with Godzilla, though, the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster is neither strictly “natural” nor is it strictly “human-made.” In their respective articles, “The Hidden Face of Disaster” and “Fourfold Disaster,” Oguma (2011) and Takahashi (2011) discuss how, although the earthquake and tsunami were natural phenomena, the historical complexities and contingencies behind the Tohoku and Kanto regions made the disaster much more than strictly “natural.” That is, while the meltdown was triggered by physical processes, human processes led to the reactor's placement in the path of the earthquake and tsunami. Even in the aftermath, natural and human processes intertwined as ocean currents dispersed the high levels of radiation to the various fishing communities south of Fukushima (Takahashi, 2011). Though fisheries were only temporarily closed, perhaps more disastrous was the damage to the region's reputation due to rampant suspicions of radiation-contaminated fish (Takahashi, 2011).

Thus, Plantu's remix of the Great Wave as a representation of the Fukushima tsunami further reinforces how Great Wave has become associated with disaster. But, critically, closer examination of the Godzilla and Fukushima imagery—arguably icons in themselves, by this point—in these remixes complicates our ideas of disaster as strictly natural or anthropogenic. Indeed, we might argue that all environmental disasters and crises occur in this gray area, simply because humans are embedded within ecosystems and ecosystems are influenced by our activities.

In truth, this case study only scratches the surface of an extremely complex and fascinating subject: Katsuhika Hokusai's Great Wave off Kanagawa. In this case study, we examined how the woodblock print has been circulated and recirculated and transformed in the modern, digital era. We discussed how Great Wave itself represented resilience in the face of contemporary artistic and social change. In more recent times, Great Wave has become associated with a different kind of change: the drastic, catastrophic change of environmental disasters and crises. Finally, we focused on how Great Wave and many of its remixes evoke multiple dualities and, more importantly, blur those distinctions.

In that sense, we might take solace in those blurred readings as a form of resilience. That is, environmental disasters and crises are neither inevitable, solely natural phenomena beyond our control nor are they strictly “our fault.” Instead, to borrow Helmreich's (2015) words, as Hokusai's “Great Wave enters into the Anthropocene,” and as we as a “collectivity” (Napier, 1993) enter into uncertain times fraught with environmental crises—we might consider Hokusai's original perspective in Great Wave, one that treats human and non-human subjects in balance. By reminding ourselves of the distinctly human and natural elements that together comprise crisis and disaster, we offer ourselves a more holistic, nuanced approach to environmental uncertainty—uncertainty that is sure to make waves in the coming years.

On Jan. 11, 2021, the disturbing image of a manatee with the letters T-R-U-M-P written on its back circulated on social media. This image surfaced at a time when the country was already in a politically sensitive state, and so the stage was perfectly set for the manatee to go viral. The manatee image appeared online a mere 5 days after the United States Capitol Building was ravaged by a mob of Donald Trump supporters, the 45th president. The mob's goal was to attempt to overturn President Trump's defeat in what they believed was a “rigged” election. The event was no small occurrence; it was the first time the Capitol Building had been breached since the British destroyed the Capitol in 1814 during the War of 1812 (Sherman, 2021). The image of the “Trump manatee” began to circulate at a time when the country had just had its sense of patriotic security violated.

The image in Figure 9 was originally screenshot and cropped from a video shot by a scuba diver in Florida, who came across the manatee and documented the crime on her camera to report to local authorities. Because most of the public only had a screenshot to inform them about the incident, they were empowered to make assumptions and draw inaccurate conclusions from the image. In fact, the first reports about the incident reported that “TRUMP” had been carved into the manatee's back, leaving many people to feel outrage and bewilderment at such horrible treatment of an animal. Soon after, a corrective statement was released, clarifying “…‘Trump’ was not carved into the animal's back, but rather written into its algae” (Dapcevich, 2021). However, the damage had already been done. The combination of the original reports and the image itself led the public to the conclusion that the manatee was severely harmed. This instilled a sense of anger in the public over the desecration of a sacred environmental icon. The provocative “Trump manatee” image led to numerous creative visualizations that stemmed from the original manatee image. It is important to note that while the manatee was not severely harmed, a serious crime was still committed. Touching a manatee is illegal and violates U.S. federal laws, such as the Endangered Species Act and the Marine Mammal Protection Act. For the purposes of our study, we will focus on evaluating the discourse around the images and observe what the internet had to say about Donald Trump and the political ties this image clearly communicates to its audience. Some of the resulting images simply connect manatees to Trump, others condemn Trump and his supporters, and still others speak to the iconic role manatees play in the environmental movement.

The variations of the “Trump manatee” are fascinating and speak to the amount of rhetorical imagination and velocity at play on the internet today. As Gries claims, authors and artists “can never fully control where or how the things they produce will circulate. Things, especially in a digital age, simply, or rather complexly, flow” (2013). There was no shortage of images and other screenshots of the manatee's back, making it easy to find an accurate image from the event. The manatee was a popular news story, and its circulation offered numerous examples of the more credible version of the image were widely available throughout the internet.

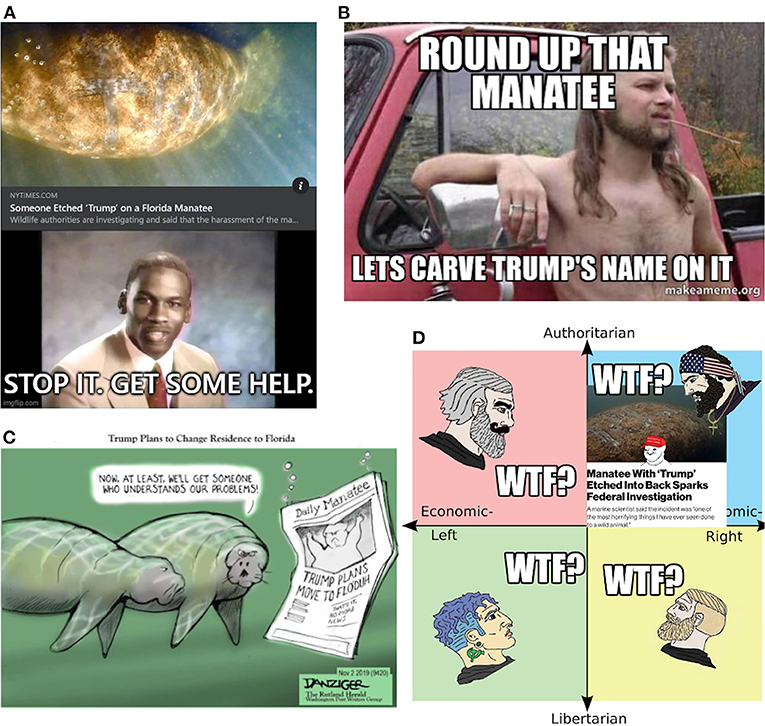

However, other, less accurate, images surfaced too. Some variations included images that were drawn over in harsh, red marker, so the viewer could quickly identify the name “TRUMP” written on the manatee's back, as seen in Figure 10. The incident also inspired memes, which allowed the public to express their disapproval of the event. For example, one meme depicted the manatee's back along the top half of the image, and the bottom half of the image was a still shot of Michael Jordan, where he is quoted saying, “Stop it. Get some help.”

Figure 10. The remixes of the Trump manatee. (A) Michael Jordan meme screen capture from imgflip.com. (B) The Florida Man screen capture from makeameme.org. (C) A political cartoon screen capture from VTDigger.org. (D) A depiction of unity across political parties over the Trump manatee screen capture from the Reddit thread r/PoliticalCompassMemes.

Figure 10A speaks to the general public's vitriol at the image of someone harming a manatee and exemplifies their disapproval of the act. The image of Michael Jordan on the bottom half of the meme is a screenshot from Michael Jordan's anti-drug ad for McDonald's that originally aired on ABC in May 26, 1987. In the ad, during his speech, Michael says, “Stop it. Get some help.” Michael Jordan is an American icon, and to have him denounce the manatee incident sends the message that the moral conclusion is to object to writing on the manatee. Generally, speaking, Americans are reluctant to disagree with a sports hero like Michael Jordan.

Another example goes beyond expressing the public's disapproval of the event by also insulting Trump's supporters (Figure 10B). The meme shows a long-haired, unkempt, and shirtless white man leaning against what appears to be a red pick-up truck with rings on his fingers and a long piece of grass sticking out of his mouth. The meme has block letter captioning splashed across it, reading, “Round up that manatee. Lets carve Trump's name on it.” This image targets a derogatory stereotype of an undereducated, white population that many associate with Trump supporters, or what has become known as a “Florida man.” According to Wikipedia, “Florida Man is an Internet meme, popularized in 2013, in which the phrase ‘Florida Man’ is taken from various unrelated news articles describing people who hail from or live in Florida…The stories call attention to Florida's supposed notoriety for strange and unusual events” (Wikipedia, 2021b). This meme sends a message that someone who would support “carving” Trump's name on a manatee is the same kind of person that could be described as a “Florida Man.” In a way, this meme responds to the criminal who wrote Trump on the manatee, attacking his character with a negative stereotype.

Several images speak to how deeply manatees are embedded in our minds as environmental icons. Some images even pitted manatees against Trump, and they were created before the original image of the manatee's back with “TRUMP” written on it had even been created. One image (Figure 10C) was a political cartoon that appeared in the VTDigger, which depicted two angry manatees discussing a newspaper article that says, “Trump Plans Move to Flo'duh” and one manatee says to another, “Now, at least, we'll get someone that understands our problems!” This image exemplifies the public's misplaced hope that President Trump would represent their best interests, and plays on the fact that he did not fight for the environment during his political career. Lastly, perhaps the most interesting meme of all (Figure 10D) was a meme that depicts a chart of all political beliefs, with cartoon depictions of four political archetypes looking disapprovingly at a news headline about the manatee incident. The face of each political archetype “WTF?” written near their heads like speech bubbles, further clarifying that each political party was at the very least confused by the act of writing “TRUMP” on a manatee.

As an icon of environmental conservation, manatees embody the importance of protecting our planet, especially sea life in Florida, where this crime was committed. By writing “TRUMP” on the manatee, the criminal was sending a message: Trump and his supporters do not care about the environment. Most interestingly, the image placed a divisive, triggering name in opposition to a manatee and thereby emphasized a political gap during a particularly turbulent time in our country. To see an iconic environmental image like a manatee ravaged by the name “TRUMP” a few days after the Capitol Building was ravaged by Trump supporters fanned the political flames, and the public was bound to circulate the image across the internet. The timing of the manatee incident was an important factor in the image's widespread circulation. An “image's propensity for circulation” can perform “an important socio-rhetorical function” for people “by providing the existential orientation required for ‘a public needing to figure out where it stood in relation to what it saw’” (Zelizer, 2010). The manatee allowed the public to process their reactions and feelings toward the Capitol raid through a different event. Each version of the Trump manatee image conveys a different meaning from the next. Some visuals draw a connection from manatees to Trump, others criticize Trump and his supporters for the incident. The image's wide array of digital circulation speaks to the important role that environmental icons play in public discourse.

Surprisingly, there are very few remixes that support the political views of the original image. One might expect to find memes that attempt to satirize the “liberal tears crying over a manatee,” or a visual portraying a weak manatee, or even a cartoon portraying the person who wrote on the manatee's back in a positive light. However, none of these images surfaced. Only images that denounce the act can be found. Even searching with provocative phrases like “fake manatee Trump” and “manatee conspiracy trump” rendered no results. This discovery of lack instills hope, instilling the hope that the desecration of an environmental icon like a manatee could be a universally uniting event, regardless of political beliefs. This event could have had a unifying effect that was fueled by a general hatred for Trump, or a general love for manatees, or both. Regardless, the event seemed to have had some unifying effects on audiences in the United States. Figure 10D demonstrates a chart of all political beliefs condemning the manatee event clearly demonstrates that no matter one's political party, everyone disapproved of writing on the manatee. This finding suggests that, while there is a long way to go for political unity in the United States, environmental icons may help to bridge that political divide.

In this essay, we have intended to make visible the important role of image circulation in digital environmental communication. Through this initial study, we attend to some of the ways that environmental images circulate online. This research demonstrates the wide range of applications and functions that the circulation of images have in environmental discourse. Our study demonstrates the value of visual environmental communication and memes as important topoi for environmental discourse. Further, these case studies elaborate on the increasingly central role that visual and social media play in public advocacy. Image tracking reveals how an image can be transformed and translated to reach a variety of audiences, increasing its effectiveness. For The Lorax, its remixes into cartoons and animations cultivated new audiences and reanimated a classic illustration for new generations. The iconic Lorax image was also remixed into a variety of memes, displaying different messages to other audiences. Image tracking also shows how the iconic graphic needs few words to have such a strong meaning with its use on protest signs and t-shirts. Image circulation suggests the ecological dimensions of rhetorical exchange.

Iconographic tracking also reveals how an image's core, underlying themes and topologies can span multiple social, historical contexts unchanged, even as the image itself is remixed, mutated, and circulated in novel ways over time. To this day, Great Wave off Kanagawa and its remixes echo the woodblock print's original themes: blurred duality of human-nature relations and resilience in the face of (social) change. In the modern era, Great Wave remixes blur the distinction between “natural” and “human-made” disasters, but also suggest resilience in the face of catastrophic environmental crises. In the case of the manatee icon, the circulation of the image unified audiences, crossing political and social boundaries during a tumultuous and politically-charged period in American discourse. Environmental icons can cultivate shared political experiences and foster unity in a fractured media landscape. Images travel rapidly online when they are heavily intertwined with news media.

Among each of our case studies, we find the trend toward more extreme and negative variations of the iconographic images having more staying power over time. While the Trump Manatee image is unique in recent history for appearing to bridge our definitive political divides, it also follows the age-old mantra of “if it bleeds, it leads” due to the fabrication of the “TRUMP” message being supposedly carved into the animal. On some level, the rhetorical velocity of more negative environmental icons tracks with what we have learned about social network algorithms in wake of Facebook whistleblower Frances Haugen's testimony: that Facebook continued to use algorithms with preference for more extreme content because such content was better correlated with the overall growth of the network (Hao, 2021). However, the trend toward darker and more negative icons among our case studies may also correlate with an ever-increasing exigence for governments and corporations to take more seriously the issue of global warming and human-made environmental disasters. Either way, this presents an opportunity to improve the resolution of theories such as rhetorical velocity, and to examine particular types of virality—asking whether there are different forces and correlating events that speed the velocity of particular icons and messages in digital networks.

While the sharing of memes online has often been dismissed as an ambivalent or performative gesture, image circulation is an important element of participation in digital publics. As part of that larger goal, we seek to demonstrate that memes and other forms of image circulation are worthy of greater consideration. Though this study was limited in scope, it suggests room for further research into the ways that the circulation of memes can be an important tool for environmental communicators. The initial findings we present suggest some of the important ways that the circulation of memes and other iconic images circulate within broader, ongoing conversations in environmental communication. As social media and other networked writing environments become increasingly central to the myriad ways the public engages with and in science and environmental communication, there is no doubt that visual and digital media will remain an important area of inquiry with further scope for research.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

MJ conceived, designed, and directed of the study and wrote the first draft of the introduction, methods, and conclusion. JG, AG, and HM performed the iconographic tracking research and drafted the individual case studies. AB worked with MJ to complete the major revisions. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

Funding for this project was generously provided through the Open Access Fund, a subvention grant from the University of Rhode Island established to support researchers who choose to publish in open access journals. Any views, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this project do not necessarily represent those of URI.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

We thank journal editor SG as well as the two reviewers, whose generous feedback helped refine and develop this study. We would also like offer our gratitude to all of the members of the NRS 568: Visualizing Environmental Advocacy graduate class, whose insightful comments and iconographic tracking projects inspired our work, especially Aaron Shaheen and Eva Baker, who offered helpful feedback on an early draft of this essay.

1. ^I am the Lorax I speak for the trees T shirt (2021). https://newgraphictees.com/product/i-am-the-lorax-i-speak-for-the-trees-t-shirt/ (accessed March 30, 2021).

2. ^Hake's Dr. Seuss designed rare “I SPEAK FOR THE TREES” Ecology-themed button featuring The Lorax. (2013). https://www.hakes.com/Auction/ItemDetail/79599/DR-SEUSS-DESIGNED-RARE-I-SPEAK-FOR-THE-TREES-ECOLOGY-THEMED-BUTTON-FEATURING-THE-LORAX (accessed March 30, 2021).

3. ^Misli. (n.d.). https://www.pinterest.com/pin/428053139554374889/ (accessed March 30, 2021).

4. ^I am the Lorax and I Speak for the trees! (n.d.). https://imgur.com/gallery/9pvVx1w (accessed March 30, 2021).

5. ^Picture memes 78vlLnMq6 - iFunny (n.d.). https://www.pinterest.co.kr/pin/627055948099310315/?amp_client_id=CLIENT_ID(_)&mweb_unauth_id=&from_amp_pin_page=true (accessed March 30, 2021).

6. ^The Lorax YouTube Clip Art - Lorax Dr Seuss Characters - Png Download (n.d.). https://www.pinclipart.com/pindetail/ibTTbih_the-lorax-youtube-clip-art-lorax-dr-seuss/ (accessed March 30, 2021).

7. ^I am the Lorax I speak for the trees - I am the Lorax, I., and speak for the trees (2020). https://knowyourmeme.com/photos/1038793-i-am-the-lorax-i-speak-for-the-trees (accessed March 30, 2021).

8. ^Doritos transparent png,animated dr seuss characters. (n.d.). https://www.pngkin.com/pen/hbmbow/ (accessed March 30, 2021).

9. ^I am the Lorax, I speak for the trees, and they say, Well I don't know it was in Vietnamese (n.d.). https://www.pngegg.com/en/png-yiicp (accessed May 23, 2020).

10. ^The trees!: Really funny memes, history jokes, stupid funny memes. (n.d.). https://www.pinterest.com/pin/819936675887264406/ (accessed March 30, 2021).

11. ^ゴジラ (“Gojira”) in Japanese.

12. ^A truly fascinating work that, although it makes no formal mention of Gries or iconographic tracking, offers a much more comprehensive exploration of Great Wave's rhetorical velocity in the modern era than we can offer here. In the interest of minimizing overlap and for space, we direct the reader to Helmreich's work for an extended discussion on Great Wave's association with climate change, pollution, and other environmental issues that characterize the Anthropocene.

Abeza, D. (2020). Why Is the Great Wave Off Kanagawa so Famous? Available online at: https://www.atxfinearts.com/blogs/news/the-great-wave-off-kanagawa-so-famous (accessed March 11, 2021).

Born, D. (2019). Bearing witness? Polar bears as icons for climate change communication in national geographic. Environ. Commun. 13, 649–663. doi: 10.1080/17524032.2018.1435557

Cagle, L. E. (2021). “Doing science digitally: the role of interactive and multimedia representations in scientific rhetoric,” in Routledge Handbook of Scientific Communication, eds C. Hanganu-Bresch, S. Maci, M. Zerbe, and G. Cutrufello (New York, NY: Routledge), 307–323.

Cagle, L. E., and Tillery, D. (2015). Climate change research across disciplines: the value and uses of multidisciplinary research reviews for technical communication. Tech. Commun. Q. 24, 147–163. doi: 10.1080/10572252.2015.1001296

Cartwright, J. H. E., and Nakamura, H. (2009). What kind of a wave is Hokusai's Great Wave off Kanagawa? Notes Rec. R. Soc. Lond. 63, 119–135. doi: 10.1098/rsnr.2007.0039

Chosetec User Profile (2010). A Great EVA off Kanagawa. Available online at: https://www.deviantart.com/chosetec (accessed March 28, 2021).

Couldwell, A. (2021). The Great Wave Off Kanagawa. Available online at: https://clubofthewaves.com/feature/the-great-wave-off-kanagawa/ (accessed March 11, 2021).

Dailey, D. (2012). Five Interpretations of the Lorax. Available online at: https://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-17224775 (accessed March 28, 2021).

Dapcevich, M. (2021). Was 'TRUMP' Carved into a Florida Manatee's Back? Available online at: www.snopes.com/fact-check/trump-carved-manatees-back/ (accessed January 13, 2021).

Daretoeatapeach (2017). The 35 Best Protest Signs From the San Francisco Science March. Available online at: https://futureisfiction.com/35-best-protest-signs-san-francisco-science-march/ (accessed March 30, 2021).

Davis, C. B., Glantz, M., and Novak, D. R. (2015). “You can't run your SUV on cute. Let's go!”: internet memes as delegitimizing discourse. Environ. Commun. 10, 62–83. doi: 10.1080/17524032.2014.991411

DeLuca, K. M., and Demo, T. D. (2000). Imaging nature: Watkins, Yosemite, and the birth of environmentalism. Crit. Stud. Media Commun. 17, 241–260. doi: 10.1080/15295030009388395

Dobrin, S. I., and Morey, S. (eds.). (2009). Ecosee: Image, Rhetoric, Nature. Albany, NY: SUNY Press.

Dudley, J., and Dias, F. (2013). On Hokusai's Great wave off Kanagawa: localization, linearity and a rogue wave in sub-Antarctic waters. Notes Rec. R. Soc. Lond. 67, 159–164. doi: 10.1098/rsnr.2012.0066

Dunaway, F. (2015). Seeing Green: The Use and Abuse of American Environmental Images. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Edbauer, J. (2005). Unframing models of public distribution: from rhetorical situation to rhetorical ecologies. Rhetor. Soc. Q. 35, 5–24. doi: 10.1080/02773940509391320

Eyman, D. (2015). Digital Rhetoric Theory, Method, Practice. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

Funny Video Memes, Funny Memes, Good Jokes (n.d.). Available online at: https://www.pinterest.fr/pin/858991328908257165/ (accessed March 30, 2021).

Google Trends (2021). Great Wave Off Kanagawa. Available online at: https://trends.google.com/trends/explore?date=2004-01-01%202021-03-11&q=great%20wave%20off%20kanagawa (accessed March 11, 2021).

GradeSaver (2021). The Lorax Imagery. Available online at: https://www.gradesaver.com/the-lorax/study-guide/imagery (accessed March 30, 2021).

Greene, J. (2015). Premediating ecological crisis: a visual rhetoric of Florida sinkholes. J. Florida Stud. 1, 25. Available online at: http://www.journaloffloridastudies.org/files/vol0104/04Greene.pdf (accessed May 20, 2021).

Greenwalt, D. A., and Hallsby, A. (2021). Graphed into the conversation: conspiracy, controversy, and climategate's visual style. Rhetor. Soc. Q. 51, 293–308. doi: 10.1080/02773945.2021.1947515

Gries, L. E. (2013). Iconographic tracking: a digital research method for visual rhetoric and circulation studies. Comput. Composit. 30, 332–348. doi: 10.1016/j.compcom.2013.10.006

Gries, L. E. (2015). Still Life With Rhetoric: A New Materialist Approach for Visual Rhetorics. Logan, UT: Utah State University Press.

Gries, L. E. (2016). “On rhetorical becoming,” in Rhetoric, Through Everyday Things, eds S. Barnett and C. Boyle (Tuscaloosa, AL: The University of Alabama Press), 155–170.

Gries, L. E. (2017). Mapping obama hope: a data visualization project for visual rhetorics. Kairos J Rhetoric Technol. Pedagogy 21. Available online at: https://kairos.technorhetoric.net/21.2/topoi/gries/index.html (accessed May 20, 2022).

Hao, K. (2021). The Facebook Whistleblower Says Its Algorithms Are Dangerous. Here's Why. MIT Technology Review. Available online at: https://www.technologyreview.com/2021/10/05/1036519/facebook-whistleblower-frances-haugen-algorithms/ (accessed April 26, 2022).

Hautea, S., Parks, P., Takahashi, B., and Zeng, J. (2021). Showing they care (or don't): affective publics and ambivalent climate activism on TikTok. Soc. Media Society 7, 1–14. doi: 10.1177/20563051211012344

Hawk, B. A. (2007). Counter-History of Composition: Toward Methodologies of Complexity. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press.

Helmreich, S. (2015). Hokusai's great wave enters the anthropocene. Environ. Humanities 7, 203–217. doi: 10.1215/22011919-3616407

Jones, M. (2019). “Replacing the rhetoric of scale ecoliteracy, networked writing, and memorial mapping,” in Mediating Nature the Role of Technology in Ecological Literacy, eds S. Dobrin and S. Morey (London: Routledge), 79–95.

Kimmel, E. (2019). 10 Lessons in Quotes From the Lorax (Dr. Seuss's Classic). Available online at: https://greenglobaltravel.com/lessons-quotes-from-the-lorax/ (accessed March 30, 2021).

Krzeminski, J. (2019). Whose Utopia? American ECOFASCISM Since the 1880. Available online at: https://edgeeffects.net/ecofascism/ (accessed March 30, 2021).

Lotier, K. M. (2018). “What circulation feels like,” in Enculturation: A Journal of Rhetoric, Writing, and Culture. Available online at: https://www.enculturation.net/what-circulation-feels-like (accessed May 20, 2022).

Meijers, M. H. C., Remmelswaal, P., and Wonneberger, A. (2019). Using visual impact metaphors to stimulate environmentally friendly behavior: the roles of response efficacy and evaluative persuasion knowledge. Environ. Commun. 13, 995–1008. doi: 10.1080/17524032.2018.1544160

Milstein, T. (2011). Nature identification: the power of pointing and naming. Environ. Commun. 5, 3–24. doi: 10.1080/17524032.2010.535836

Morey, S. (2014). Florida econography and the ugly cuteness of econs. J. Florida Stud. 1. Available online at: http://www.journaloffloridastudies.org/files/vol0103/03EcoSEAN.pdf (accessed May 20, 2022).

Morye, K. (2020). “I am the Lorax. I Speak for the Trees!” - Amidst the Quarantine, There Is Hope for Climate Action. Available online at: https://medium.com/@kimayamorye/i-am-the-lorax-i-speak-for-the-trees-amidst-the-quarantine-there-is-hope-for-climate-action-c9f0d93bda8a (accessed March 30, 2021).

Mottura, M. (2016). Hokusai Gojira. Available online at: https://dribbble.com/shots/2547802-Hokusai-Gojira (accessed March 28, 2021).

Mudge, J. (2014). The Great Wave Off Kanagawa With a Kraken. Available online at: https://www.imagekind.com/the-great-wave-off-kanagawa-with-a-kraken_art?IMID=3d4d4e27-40cf-4035-a6be-ed8551804ece (accessed March 11, 2021).

Napier, S. J. (1993). Panic sites: the Japanese imagination of disaster from Godzilla to Akira. J. Japanese Stud. 19, 327. doi: 10.2307/132643

Oguma, E. (2011). The hidden face of disaster: 3.11, the historical structure and future of Japan's Northeast. Asia Pacific J. Japan Focus 9, 3583. Available online at: https://apjjf.org/2011/9/31/Oguma-Eiji/3583/article.html (accessed May 20, 2022).

Olman, L., and DeVasto, D. (2020). Hybrid collectivity: hacking environmental risk visualization for the anthropocene. Commun. Design Q. 8, 15–28. doi: 10.1145/3431932.3431934

O'Neill, S., and Nicholson-Cole, S. (2009). “Fear won't do it”: promoting positive engagement with climate change through visual and iconic representations. Sci. Commun. 30, 355–379. doi: 10.1177/1075547008329201

O'Neill, S., and Smith, N. (2014). Climate change and visual imagery. WIREs Clim. Change 5, 73–87. doi: 10.1002/wcc.249

Papacharissi, Z. (2015). Affective publics and structures of storytelling: sentiment, events and mediality. Information Commun. Soc. 19, 307–324. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2015.1109697

Pflugfelder, E. H. (2019). Risk selfies and nonrational environmental communication. Commun. Design Q. 7, 73–84, doi: 10.1145/3331558.3331565

Pratt, M. (2021). 6 Dr. Seuss Books Won't Be Published for Racist Images. Available online at: https://apnews.com/article/dr-seuss-books-racist-images-d8ed18335c03319d72f443594c174513 (accessed March 29, 2021).

Ridolfo, J., and DeVoss, D. N. (2009). Composing for recomposition: rhetorical velocity and delivery. Kairos J. Rhetoric Technol. Pedagogy 13. Available online at: https://kairos.technorhetoric.net/13.2/topoi/ridolfo_devoss/velocity.html (accessed May 20, 2022).

RisingSunPrints (2020). The Great Wave Off Kanagawa-by Hokusai (1830). Available online at: https://risingsunprints.com/blogs/masterpieces-of-japanese-art/the-great-wave-off-kanagawa-by-hokusai-1830 (accessed March 11, 2021).

Rivers, N. A., and Weber, R. P. (2011). Ecological, pedagogical, public rhetoric. Coll. Composit. Commun. 63, 187–218. Available online at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/23131582 (accessed May 20, 2022).

Ross, A. S., and Rivers, D. J. (2019). Internet memes, media frames, and the conflicting logics of climate change discourse. Environ. Commn. 13, 975–994. doi: 10.1080/17524032.2018.1560347

Salinas, I. (2019). Pop Culture for Change. Available online at: https://sundial.csun.edu/154553/arts-entertainment/pop-culture-for-change/ (accessed March 30, 2021).

Schuenemann, K. (n.d.). Lorax Trees. Available online at: https://www.pinterest.com/pin/100205160440752443/ (accessed March 30, 2021).

Sherman, A. (2021). PolitiFact - A History of Breaches and Violence at the US Capitol. Available online at: www.politifact.com/article/2021/jan/07/history-breaches-and-violence-us-capitol/ (accessed March 20, 2021).

Silvestri, L. E. (2018). Memeingful memories and the art of resistance. New Media Soc. 20, 3997–4016. doi: 10.1177/1461444818766092

Sivils, M. W. (2004). William Bartram's travels and the rhetoric of ecological communities. Interdiscipl. Stud. Literature Environ. 11, 57–70. doi: 10.1093/isle/11.1.57

Sparby, E. M. (2022). Memetic Rhetorics Toward a Toolkit for Ethical Meming. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

Streckert, J. (2021). Available online at: https://twitter.com/JoeStreckert/status/1375129180883480578?s=20 (accessed March 25, 2021).

Sultana, F. (2021). Climate change, COVID-19 and the co-production of injustices: a feminist reading of overlapping crises. Soc. Cultural Geogr. 22, 447–460. doi: 10.1080/14649365.2021.1910994

Takahashi, S. (2011). Fourfold disaster: renovation and restoration in post-tsunami coastal Japan. Anthropol. News 52, 5–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1556-3502.2011.52705.x

The Great Wave Off Kanagawa Ghidorah Merchandise From The Godzilla Store (2019). http://www.kaijubattle.net/14/post/2019/10/the-great-wave-off-kanagawa-ghidorah-merchandise-from-the-godzilla-store.html (accessed March 28, 2021).

TheDailyRobot (n.d.). The G-Wave Off Kaijugawa Godzilla. Available online at: https://www.pinterest.com/pin/366128644685017005/ (accessed March 17, 2021).

Trimbur, J. (2000). Composition and the circulation of communication. Coll. Composit. Commun. 52, 188–219. doi: 10.2307/358493

u/paradoX1995. (2019). What Is Up With Vietnamese Speaking Trees? Available online at: https://www.reddit.com/r/OutOfTheLoop/comments/a9dwua/what_is_up_with_vietnamese_speaking_trees/ (accessed March 30, 2021).

Walsh, L., and Prelli, L. J. (2017). “Getting down in the weeds to get a god's-eye view: the synoptic topology of early American ecology,” in Topologies as Techniques for a Post-Critical Rhetoric, eds L. Walsh and C. Boyle (New York, NY: Palgrave MacMillian), 197–218.

Wikipedia (2018a). Portal: Current Events/April 2012. Available online at: https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Portal:Current_events/April_2012&oldid=863658329 (accessed March 29, 2021).

Wikipedia (2018b). Portal: Current Events/May 2012. Available online at: https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Portal:Current_events/May_2012&oldid=863658358 (accessed March 29, 2021).

Wikipedia (2021a). 2004 Indian Ocean Earthquake and Tsunami. Available online at: https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=2004_Indian_Ocean_earthquake_and_tsunami&oldid=1012691297 (accessed March 28, 2021).

Wikipedia (2021b). Florida Man. Available online at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Florida_Man (accessed March 24, 2021).

Woods, H. S., and Hahner, L. A. (2019). Make America Meme Again: The Rhetoric of the Alt-Right. New York, NY: Peter Lang Publishing.

Keywords: environmental rhetoric, visual rhetoric, circulation studies, iconographic tracking, rhetorical ecologies

Citation: Jones M, Beveridge A, Garrison JR, Greene A and MacDonald H (2022) Tracking Memes in the Wild: Visual Rhetoric and Image Circulation in Environmental Communication. Front. Commun. 7:883278. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2022.883278

Received: 24 February 2022; Accepted: 12 May 2022;

Published: 09 June 2022.

Edited by:

Shane Gunster, Simon Fraser University, CanadaReviewed by:

Emma Frances Bloomfield, University of Nevada, Las Vegas, United StatesCopyright © 2022 Jones, Beveridge, Garrison, Greene and MacDonald. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Madison Jones, bWFkaXNvbmpvbmVzQHVyaS5lZHU=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers