- Department of Psychiatry, Jawaharlal Institute of Postgraduate Medical Education and Research (JIPMER), Puducherry, India

The COVID-19 pandemic, with its attendant supply chain disruptions and restrictions on internal movement, has been associated with frequent episodes of panic buying both in its initial phase and in subsequent waves. Empirical evidence suggests that news media content and consumption are important determinants of attitudes and behavior during the pandemic, and existing research both before and during the pandemic suggests that panic buying can be influenced by both exposure to media reports and their specific content. This pilot study was conducted to assess the quality of media reports of panic buying during the second year of the COVID-19 pandemic, using two independent measures of news article quality. Seventy news reports of panic buying across 12 countries, covering the “second wave” of the pandemic from January 1 to December 31, 2021, were collected through an online search of media outlets using the Google News aggregator. These reports were analyzed in terms of the content of their reporting, based on existing research of the factors driving panic buying during the COVID-19 pandemic. Each report was scored for quality using two different systems: one based on an existing WHO guideline, and one based on the work of a research group which has published extensive work related to panic buying during this pandemic. It was observed that a significant number of reports contained elements that were likely to amplify, rather than attenuate, panic buying behavior, and that the quality of news reports was generally poor regardless of pandemic severity, cultural values, or freedom of the press. On the basis of this evidence, suggestions are offered to improve the media reporting of panic buying and minimize the risk of fear contagion and imitation.

Introduction

The term “panic buying” refers to the excessive purchasing of groceries and other essential supplies by a large number of people in response to a threatened or actual disaster (Taylor, 2021). More precisely, panic buying has been defined as “the phenomenon of a sudden increase in buying of one or more essential goods in excess of regular need provoked by adversity, usually a disaster or an outbreak resulting in an imbalance between supply and demand.” (Arafat et al., 2020a). Panic buying is commonly observed following natural disasters and during outbreaks of infectious disease (Campbell et al., 2020). The global COVID-19 pandemic, caused by the respiratory coronavirus SARS-CoV-2, has caused unprecedented social and economic disruption on a global scale, both directly and as a result of the measures instituted by local and national governments for its containment (Chu et al., 2020; Schippers, 2020; Panneer et al., 2022). This has resulted in frequent and world-wide episodes of panic buying, both during the initial phase of the pandemic (Arafat et al., 2020b) and during subsequent “spikes” or “waves” in case numbers (Al Zoubi et al., 2021), generally in the context of stringent containment measures (O'Connell et al., 2021). Though understandable as a response to the threat of scarcity, panic buying tends to exacerbate shortages of food, medication and other essential materials, leading to a worsening of food insecurity and consumer anxiety (Erokhin and Gao, 2020). “Common-sense” methods of curbing this behavior, such as exhortations not to panic from public authorities, appear to be ineffective (Taylor, 2021). Thus, it is important to identify factors that may trigger, exacerbate or maintain panic buying, as these may offer alternative targets for prevention and control strategies (Zhang and Zhou, 2021).

As with any complex learned behavior, panic buying has been studied in terms of biological, psychological and social factors (Rajkumar and Arafat, 2021). Biological explanations include the activation of fear-based responses via the limbic system and autonomic system in response to fear-inducing images, such as visual images of empty shelves (Alchin, 2020) and the activation of evolutionarily preserved behaviors akin to hoarding in response to resource scarcity (Rajkumar, 2021). Psychological explanations include individual variations in threat or risk perception, tolerance of uncertainty, fear of infection and its consequences, self-efficacy and locus of control, as well as a need to control negative emotional states, such as sadness or anxiety (Cooper and Gordon, 2021). Social factors include peer pressure and imitation, cultural values such as individualism and materialism, and broader influences related to media exposure, social media usage and government and retailer policies (Jin et al., 2020; Keane and Neal, 2021). In addition to these, local and regional disease severity and transmission appear to have a direct impact on panic buying during disease outbreaks (Qiu et al., 2018; Keane and Neal, 2021).

Among the broader social factors affecting panic buying, the influence of the media in general, and of social media in particular, have attracted a significant amount of attention from researchers. It has been observed across several studies that the time spent in using social media, the individual's level of trust in the accuracy of social media reports, and the sharing of COVID-related posts on social media are associated with an increased likelihood of panic buying (Arafat et al., 2021a; Islam et al., 2021; Li et al., 2021). However, social media often reports or amplifies news items from more “conventional” mass media sources, such as newspapers or television (Arafat et al., 2021b; Leung et al., 2021), and people in low- or middle-income settings who spend less time online may be likely to rely on these sources for information related to the pandemic (Ng and Tan, 2021). Thus, it is plausible that the content of mass media reports on panic buying can influence the likelihood of this behavior in a given individual.

The influence of the media on human behavior is not always deleterious. Media can shape human attitudes both explicitly and implicitly (Berlin and Malin, 1991; Stryker, 2003) and this can lead to desirable changes in behavior. This has led to the development of media-based interventions for specific, health-related behaviors. Evidence for the efficacy of these interventions has been noted in the case of safe sex (Keller and Brown, 2002), suicide prevention (Niederkrotenthaler et al., 2010), healthy eating practices (Englund et al., 2020) and prevention of tobacco use among youth (Hair et al., 2019). However, a systematic review of mass media interventions for health purposes found that for other behaviors, such as physical exercise and reduction in alcohol use, there was no consistent evidence of efficacy (Stead et al., 2019). In some cases, media advice can have unintended negative consequences. For example, media information on healthy eating or ideal weight can lead to depressed mood or eating disorders in vulnerable individuals (Pearl et al., 2015; Munsch et al., 2021).

A key determinant of the influence of a media report on attitudes and behavior is its specific content. For example, a media message on healthy dietary practices that places undue emphasis on an “ideal” weight or body shape may lead to disordered eating, while one which provides information on healthy food components may not have this effect (Munsch et al., 2021). Similarly, a media report on suicide that sensationalizes the act, or presents it as acceptable, may lead to an increase in suicide attempts, while reports that provide only essential details and encourage those with suicidal ideas to seek help have the opposite effect (Niederkrotenthaler et al., 2010). In a similar way, the content of media reports of panic buying can influence the likelihood of an individual either engaging in panic buying or choosing alternative behaviors. For example, images or video clips of empty shelves, crowding in shops and supermarkets, or disputes between shoppers over scarce resources, when included in a news report, might serve as powerful cues for the amplification of panic buying. Conversely, providing accounts of individuals who did not resort to panic buying, or providing information on how to purchase essentials responsibly to ensure that there is no shortage, might have the opposite effect (Arafat et al., 2020c; Schmidt et al., 2021; Coleman et al., 2022).

Several studies have examined the specific content of media reports related to panic buying during the COVID-19 pandemic, and some have attempted identify specific “negative” components that could contribute to panic buying (Arafat et al., 2020a,b,c; Kolluri and Murthy, 2021; Coleman et al., 2022). However, it is not clear if such “negative” components actually have a significant impact on panic buying, and if so, what the magnitude of this effect is compared to other variables such as individual psychological vulnerability, pandemic severity and social media usage (Huan et al., 2021; Stevens et al., 2021). Nevertheless, the analysis of existing media practice in reports of panic buying – particularly during subsequent waves of the COVID-19 pandemic, when the initial “shock” effect has passed (Stevens et al., 2021) could still be of value on precautionary grounds, as it could aid in the formulation of media guidelines on the responsible reporting of issues related to shortage and scarcity in the context of pandemics and other disasters.

The current study was carried out with the aim of assessing the “positive” and “negative” content of media reports related to panic buying using two independent sets of guidelines: one derived from the widely-used WHO guidelines on the reporting of suicides (World Health Organization, 2008) and one based on research during the COVID-19 pandemic (Arafat et al., 2020d). As a secondary objective, the correlation between the scores obtained using both sets of guidelines was computed to obtain a measure of convergent validity.

Methodology

The aims of the current study were: first, to describe the contents of media reports of panic buying in relation to the COVID-19 pandemic during the year 2021, and second, to analyze the contents of these reports using two independent sets of guidelines as a benchmark.

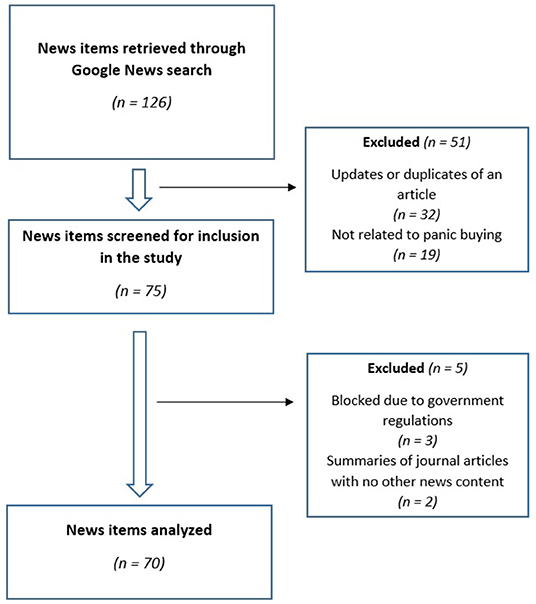

Data sources: News articles containing the terms “panic buying”, “hoarding” or “stockpiling”, alone or in combination with “COVID-19”, “pandemic” or “lockdown”, and published between January 1, 2021 and January 1, 2022, were obtained from the Google News aggregator. This time period was selected as it represented a time when most countries had recovered from the initial “wave” of the COVID-19 pandemic, but several countries experienced second or third “waves (Thakur et al., 2021; El-Shabasy et al., 2022). News reports of panic buying during the first “wave” of COVID-19 have been analyzed extensively in an earlier study by another research group (Arafat et al., 2020c). Only news items pertaining to panic buying in a specific country or region were included in the analysis; editorials and general commentaries, or articles describing panic buying from a global perspective with no reference to specific local circumstances, were excluded. A total of 126 reports were screened for inclusion in the study. After removal of (a) updates or alternate versions of the same report from the same media outlet, and (b) news items not related to panic buying, 75 news articles were screened for inclusion in the study. Of these, 3 were excluded due to restrictions by the researcher's national government, and two were excluded as they were editorials summarizing the results of published research on panic buying in scientific journals. The remaining 70 articles, originating from twelve different countries, were included in the analysis. This process is depicted as a flow diagram in Figure 1.

Extraction of specific contents: All articles were examined to identify specific factors that were mentioned as triggering or maintaining panic buying, using similar methods to the earlier study conducted during the first “wave” of COVID-19 (Arafat et al., 2020c). The classification of content items was based on prior research (Arafat et al., 2020d) and a systematic review of the factors associated with panic buying in individual studies (Rajkumar and Arafat, 2021). Each individual news article was evaluated in its entirety, including the title, content, and any subsequent updates to the article in question. If multiple updates were provided, information was extracted from all of them, but the article was counted as a single item. If articles included images or videos, these were examined to assess if their content could trigger panic buying (Alchin, 2020; Arafat et al., 2020d; Taylor, 2021).

The content extracted from each news article's title and text was classified under the following headings:

1. Pandemic-related factors (increase in case number or new variant, labor shortage due to isolation of infected workers)

2. Individual and family factors (individual psychological variables, “priming” from earlier episodes of panic buying, presence of children in the household and individual economic difficulties)

3. Sociocultural factors (social contagion, concurrent political unrest, distrust of the government by the local community, and cultural values)

4. Government policies (lockdowns or movement restrictions, non-COVID policies such as Brexit in the United Kingdom, poor or ambiguous communication)

5. Retailer policies (increase or decrease in the price of goods, increased advertising of specific goods)

6. Supply-related factors (disruption of existing supply chains, scarcity induced by panic buying, temporary disruption due to environmental factors such as floods)

7. Media-related factors (social media exposure and mainstream media exposure).

Evaluation of Article Quality

After the collection and tabulation of descriptive data, each article was evaluated according to two sets of guidelines.

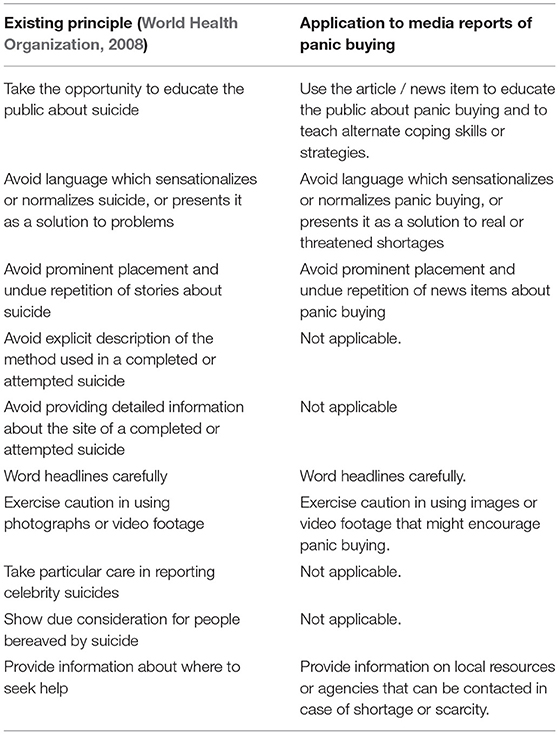

1. The first set of guidelines was derived from the WHO guidelines on the reporting of suicide (World Health Organization, 2008). In their original form, these guidelines consist of ten key principles (Table 1). However, four of these principles are not applicable to panic buying, namely reporting the means of suicide, reporting the site of a suicide, reporting celebrity suicides and showing consideration for the family of the victim(s). A fifth item, pertaining to the placement of stories in a newspaper, could not be assessed as the current study relied on online news reports. The remaining five principles were used to analyze reports omitted when analyzing reports as follows: Does the article title contain terms that sensationalize or dramatize actual or threatened shortages, or which encourage panic buying?

2. Does the article text contain words, sentences or arguments that sensationalizes or normalizes panic buying, or presents it as a solution to real or threatened shortages?

3. Does the article contain images (e.g., empty shelves) or videos (e.g., consumers fighting with retailers) that could trigger panic buying?

4. Does the article attempt to educate individuals about panic buying and how to minimize or avoid it (for example, by teaching coping skills, or discouraging excessive use of social media)?

5. Does the article provide information on local resources or agencies (such as a local government helpline) that can be contacted in case of a shortage of essentials?

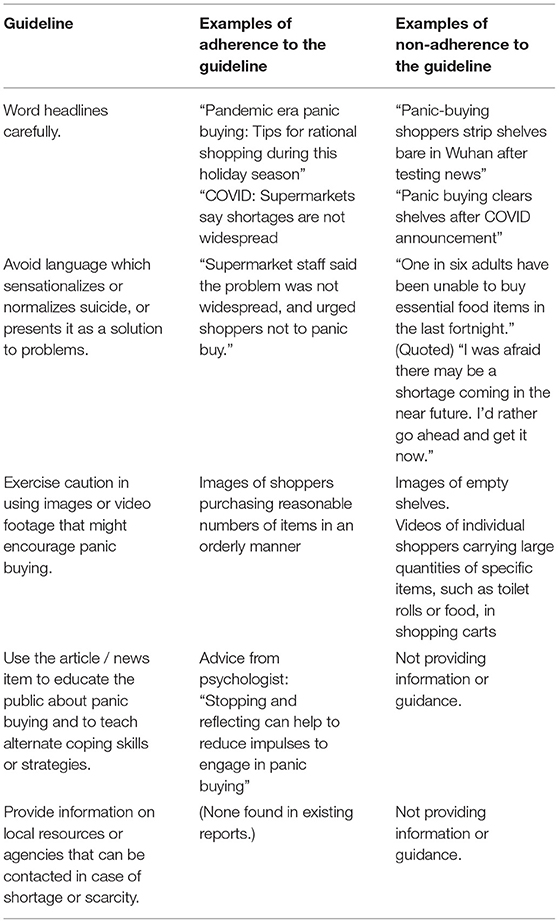

The modified WHO guidelines are summarized in Table 1. An examples of how a given article was evaluated using the guidelines, is provided in Table 2. Articles adhering to a given guideline were given one point for that particular item, while those which were non-adherent were given a score of zero for the concerned item; thus, an individual article's total score (“WHO score”) could range from 0 to 5.

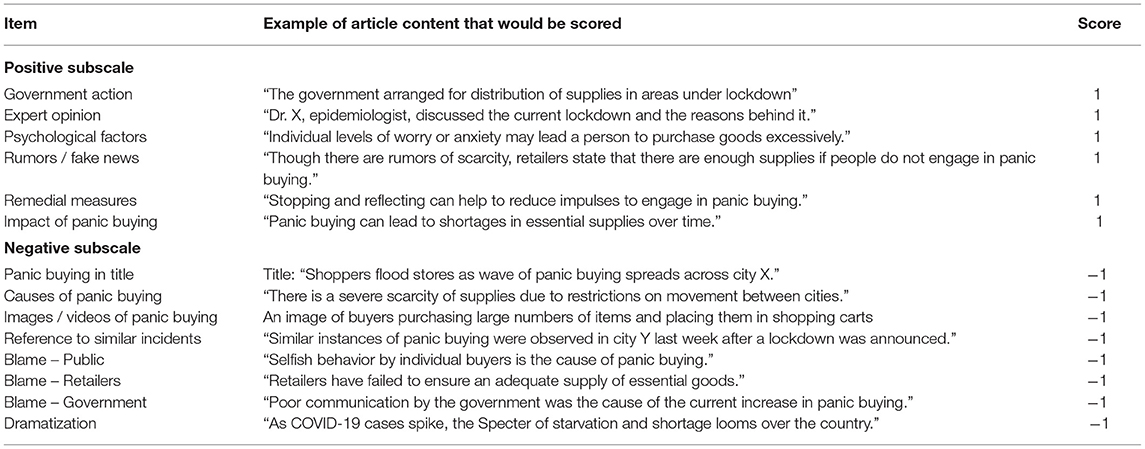

The second set of guidelines was based a publication by a research group with extensive experience in the field of panic buying during the COVID-19 (Arafat et al., 2020c), and are referred to in this paper as the “Arafat et al. guidelines”. This research group divided the content of media reports related to panic buying into six “positive” and eight “negative” items. “Positive” items include discussions of government action, expert opinion, and individual psychology, addressing the issue of rumors, discussion of the impact of panic buying, and suggestions for remedial measures. “Negative” items included mentioning panic buying in the title, mentioning causes of panic buying such as shortage, displaying images or videos of panic buying, referring to past incidents of panic buying, blaming the public, blaming retailers, blaming the government, and dramatization or sensationalization of panic buying. These items were used without any modification. A complete list of the items, and an example of how an individual article was evaluated using these guidelines, is provided in Table 3. Articles were awarded one point for each “positive” item and−1 point for each “negative” item; thus, an individual article's total score (“Arafat score”) could range from +6 to−8. For each article, both the total Arafat score and the sub-scores for positive and negative items were computed.

Assessment of the Influence of External Factors on Media Reports

Earlier research on media reporting during the COVID-19 pandemic has suggested that the content of news articles is crucially influenced by local pandemic severity (Ng and Tan, 2021), the cultural value of collectivism (Ng and Tan, 2021), and the level of freedom accorded to the press in a given country (Roukema, 2021). Thus, in a secondary analysis, this study also examined whether these variables influenced the content and quality of media reports related to panic buying, as measured using both the modified WHO and Arafat et al. guidelines. Pandemic severity was assessed using national prevalence and mortality rates for COVID-19, obtained from the Johns Hopkins University of Medicine's Coronavirus Resource Center (Johns Hopkins University of Medicine, 2022). National levels of collectivism were assessed using the Global Collectivism Index, which is the first truly q19global measure of this cultural value (Pelham et al., 2022), while freedom of the press was assessed using Reporters Without Borders' Press Freedom Index (Reporters Without Borders, 2021), which has been used in the earlier study cited above.

Data analysis: Descriptive statistics (frequencies and percentages) were used to summarize the distribution of individual content items across news reports. To assess the convergent validity between the two measures of news article quality used in this paper, Spearman's correlation coefficient was computed for correlations between the following pairs of parameters: (a) WHO—Arafat total, (b) WHO—Arafat “positive”, (c) WHO—Arafat “negative” and (d) Arafat “positive”—Arafat “negative”. Spearman's coefficient was computed as these variables did not conform to a Gaussian distribution. All these analyses were two-tailed, and a value of p <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 70 news articles were included in this study, originating from the following 12 countries: Australia, Canada, China, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, New Zealand, Singapore, Taiwan, Viet Nam, the United Kingdom and the United States of America. In terms of relative frequency, the highest numbers of reports were from the United Kingdom (19), followed by Australia (16), India (10), the United States of America (6), Canada and China (5 each), New Zealand (3), Viet Nam (2); there was one report each from Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore and Taiwan.

All news articles reported at least one “cause” or “reason” for panic buying. The number of reasons for this behavior reported in individual articles ranged from a minimum of 1 to a maximum of six, with a mean of 2.63 and a standard deviation of 1.05. In contrast, a little over half of the included articles (39/70; 55.71%) discussed methods of minimizing or controlling panic buying.

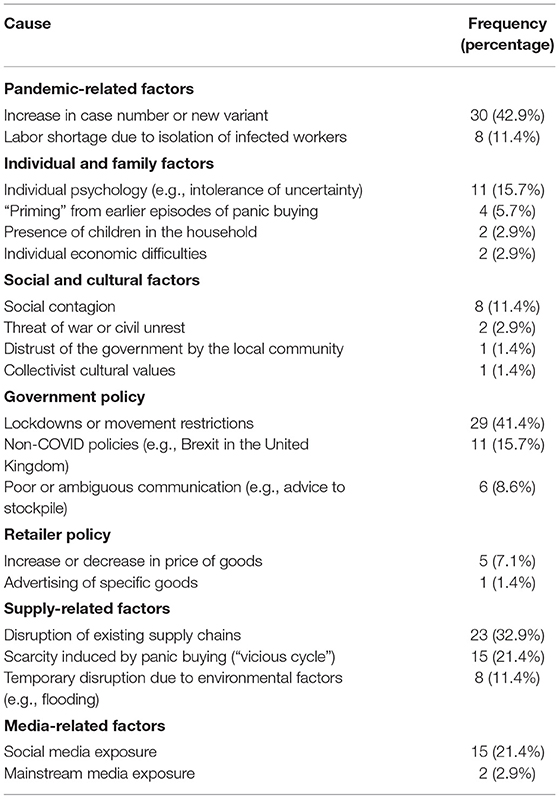

Causes reported for panic buying in the news article are summarized in Table 4. The most frequently cited causes were a local increase in the number of COVID-19 cases (42.9%), actual or announced lockdowns (41.4%) and actual scarcity of specific items (32.9%). Other frequently reported causal factors were the “vicious cycle” of panic buying leading to shortages and further panic buying (21.4%), exposure to panic buying cues via social media (21.4%), governmental policies not related to COVID that caused supply chain disruptions (15.7%), individual psychological factors such as fear of starvation, intolerance of uncertainty and a sense of insecurity (15.7%), “social contagion” through imitation of others (11.4%), labor shortages due to COVID infection (11.4%), and environmental factors such as storms or flooding which damaged roads and delayed the movement of essential supplies (11.4%). Of note, only two reports (2.9%) flagged media coverage in mainstream outlets as a potential driver of panic buying.

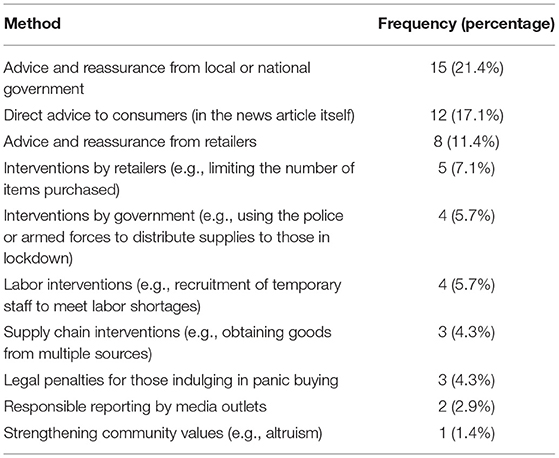

Twelve of the 70 articles studied (17.1%) provided direct advice to readers not to engage in panic buying, and encouraged more rational purchasing practices. Other methods mentioned as being potentially useful in controlling panic buying in these articles included advice or reassurance from the government (21.4%), advice or reassurance from retailer or supermarket staff (11.4%), and changes in retailer policy to improve the availability of essential supplies (7.1%). A complete list is provided in Table 5.

When using the modified WHO scale, individual news articles received scores from 0 to 4 (mean 1.99±1.00) indicating a generally low article quality; no article received the maximum possible score of 5 on this scale. When using the Arafat et al. scale, individual news articles received scores from−6 to +3 (mean−1.89±1.92), again indicating a low article quality. The mean score for the “positive” Arafat et al. subscale was 1.54±1.34, and no article received the maximum score of 6 for “positive” news coverage. The mean score for the “negative” Arafat et al. subscale was 3.43±1.25, indicating that articles scored substantially higher on “negative” than on “positive” items by this measure.

The correlation between the modified WHO and Arafat et al. quality ratings, though significant, was modest (Spearman's ρ = 0.24; p = 0.043), indicating a low degree of convergent validity between these measures. The modified WHO score was more strongly correlated with the Arafat et al. “positive” subscale (ρ = 0.57, p <0.001), indicating a substantial agreement between these measures; however, the correlation between the modified WHO score and the Arafat et al. “negative” subscale was modest but statistically significant (ρ = 0.24, p = 0.048). The Arafat et al. “positive” and “negative” subscales were not significantly correlated with each other (ρ = −0.09, p = 0.442), indicating a lack of overlap between them.

When mean quality scores for each country were examined, it was found that Viet Nam scored the highest (3.00), and China the lowest (1.60) on the modified WHO scale. When the Arafat et al. scoring system was used, the highest and lowest scores were assigned to Canada (1.40) and India (-3.70) respectively. No significant difference was observed between countries classified as “high-income” and “low- and middle-income” in terms of mean modified WHO or Arafat et al. quality scores.

On examining the relationship between news article quality and external factors, the mean modified WHO score for each country did not correlate significantly with COVID-19 prevalence (ρ = 0.49, p = 0.108), COVID-19 mortality (ρ = 0.32, p = 0.306), cultural collectivism (ρ = −0.10, p = 0.753) or the Press Freedom Index (ρ = 0.29, p = 0.358). Similarly, the mean Arafat et al. quality score for each country did not correlate with COVID-19 prevalence (ρ = 0.34, p = 0.275), mortality (ρ = 0.40, p = 0.193), collectivism (ρ = −0.35, p = 0.258) or the Press Freedom Index (ρ = −0.27, p = 0.401). No significant correlation was observed between these variables and either the “positive” or “negative” subscales of the Arafat et al. score.

Discussion

The current analysis of media reports during the second year of the COVID-19 pandemic reveals certain significant facts. First, panic buying is represented in the media as a complex phenomenon, arising from individual, social and disease-related facts, with at least one or two “causes” mentioned in each article. This is in contrast to news items published during the initial part of year 2020, in which 18% of articles did not discuss the causes of panic buying (Arafat et al., 2020a); however, a later study by the same group found that all news articles published toward the later part of 2020 did discuss the causes of panic buying (Arafat et al., 2020c). While many of the individual and social factors mentioned in these reports are similar to those identified by researchers (Bentall et al., 2021; Chua et al., 2021; Di Crosta et al., 2021), a unique aspect of the media reports is their focus on broader governmental and supply chain-related factors that are often not captured in psychological research. In this respect, media reports on panic buying play a useful role, as they highlight systemic factors which should be taken into account when addressing this behavior (Kaur and Malik, 2020). A further observation of interest is that some media reports described consumers as having been “primed” for later panic buying by their earlier experiences of panic buying during the initial phase of the pandemic; this is an interesting hypothesis that could easily be tested in general population samples across countries.

When news reports were analyzed according to two independent sets of criteria–one derived from the WHO media guidelines on suicide and one from prior research on panic buying during the COVID-19 pandemic, it was found the majority of news reports fell short of a desirable standard when covering panic buying: none of the articles included information on local help or resources, 65% included images or videos that could encourage panic buying, 54% had a “sensational” or exaggerated title, 46% presented panic buying as normal or necessary, and 44% did not include information or advice that could potentially reduce panic buying. The reports studied came from recognized and widely read newspapers or news outlets and not from isolated posts on social media, and these figures did not correlate with either pandemic severity, cultural values, or freedom of the press. Article quality scores were comparable between high- and low/middle-income countries, suggesting that concerns about poor reporting of panic buying in the media are a global problem (Arafat et al., 2020a,c, 2021b,c; Lee et al., 2021).

When examining the convergent validity of the modified WHO and Arafat et al. scores, a good degree of agreement was found between the modified WHO and Arafat et al. “positive” scores, but only modest correlations were observed between the modified WHO and the Arafat et al. total and “negative” scores. Moreover, the “positive” and “negative” subscale scores of the Arafat et al. score did not correlate significantly with each other, indicating their independence in statistical terms. These results suggest that the Arafat et al. scoring system may provide a more comprehensive and well-rounded assessment of the quality of news articles related to panic buying, covering both the desirable and undesirable aspects of media coverage of this phenomenon, as opposed to the modified WHO score which mainly assesses “positive” or desirable aspects of news articles.

These results suggest a need for the journalistic profession to adopt certain basic guidelines when reporting on panic buying. Such guidelines should not be simply copied from analogous guidelines on other issues of public importance, but should include the perspectives of all stakeholders involved – not only journalists but civil authorities, healthcare professionals, retailers and members of affected communities. This was confirmed by the results of the current study, which found that a more detailed guideline developed on the basis of empirical research provided a better assessment of article quality than one modified from existing guidelines on a different behavior. The fact that only around 3% of media reports identified news media itself as a perpetuator of panic buying is an example of the well-known psychological phenomenon of the “bias blind spot”, in which individuals or members of a group are aware of the shortcomings of “others”, but not of their own (Pronin et al., 2002). Formulating a general guideline or checklist would help journalists avoid this “blind spot” when reporting on panic buying, and might be useful as a “harm reduction” strategy on precautionary grounds. However, evaluating the true effect of such guidelines would require longitudinal studies of rates of panic buying before and after the adoption of the concerned guideline, in order to ensure that any change observed is genuinely a result of the change in media practice (Logan and Longo, 1999; Stead et al., 2019).

In the light of these findings, the possibility of using the media as a tool not only to minimize panic buying, but to encourage alternative, “positive” attitudes and behaviors during a pandemic or other crisis. This could be done by encouraging media personnel to focus on reporting the “positive” items from the Arafat et al. scoring system (Arafat et al., 2020d), and / or to place a greater emphasis on encouraging alternative methods of coping with this situation, as listed in Table 5. Many of these methods require sustained cooperation between communities, retailers and local or national authorities;

It is important to note that media exposure is only one of many factors that could influence panic buying: the numerous factors listed in Table 1 are probably all relevant, as are the others identified by researchers. Therefore, while modifying media reporting practices may be desirable, it not clear how much of an effect such measures would have vis-à-vis these other factors. It is also apparent from recent research that purchasing patterns in the general population can change over the course of the pandemic, with many “apprehensive” (panic buying) consumers gradually shifting to a “prepared” or “dedicated” behavior pattern characterized by more rational purchasing and safety behaviors (Sheng et al., 2021). If this finding applies in other settings, it is possible that media strategies might have their greatest impact in the initial phase of a pandemic, and that their impact may lessen as individuals develop less anxiety-driven behaviors over time. It should also be noted that a direct inference about the role of the media cannot be made from the data presented in this paper. However, it can be observed from Figure 1 that there were 32 instances of a media report of panic buying being updated by the concerned news agency to reflect further panic buying behavior. It is possible that in at least some of these cases, the initial report may have triggered further panic buying, but this cannot be verified from the available data.

The current study is subject to certain important limitations. First, it is based on a relatively small number of media reports, reflecting the greater severity and public prominence of panic buying in the initial phases of the COVID-19 pandemic (Arafat et al., 2020a; Sheng et al., 2021) and its subsequent attenuation due to gradual improvement in supply chains, reduction in pandemic severity, and a general sense of “COVID news fatigue” both in the media and among the general public (Liu et al., 2021; Xiao et al., 2021). Second, the adoption of modified WHO media guidelines on suicide reporting when analyzing these reports may have limited validity, as panic buying is a significant different behavior from suicide and has a more collective dimension; the guidelines derived from existing research on panic buying may have greater validity. Third, it is possible that other economic or social factors, not analyzed in this study, could have affected the quality of media reports. Fourth, as it was based on a simple content analysis of media reports, this study could not take into consideration the effects of acute vs. repeated exposure to these reports. Though initial exposures to media reports of shortage and scarcity may induce panic buying in those exposed, prolonged or sustained exposure to such reports may lead to a certain degree of “desensitization” and an attenuation in the resultant behavioral responses (Stevens et al., 2021). Fifth, as the study relied on news reports in a single language (English) and obtained from a single news aggregator (Google News), it may have failed to provide a truly global picture of the quality of reports on panic buying, particularly from regions such as Eastern Europe, South-East Asia and Africa. Sixth, as certain news items were blocked due to governmental restrictions, their content could not be analyzed. Seventh, because of the study design, it was not possible to assess whether an initial report of panic buying triggered this behavior, as reflected in subsequent reports from the same region or news agency. Eighth, all studied reports were from national or international media outlets with official websites, and thus might have failed to cover local factors or variables of significance that were published in vernacular media without a significant online presence. Ninth, due to a shortage of manpower at the time this study was conducted, all news articles were evaluated by a single rater; therefore, it was not possible to assess the inter-rater reliability of the content classification and scoring systems used. Finally, some researchers have found that the impact of conventional media coverage on panic buying is minimal (Huan et al., 2021). If this finding is accurate, it suggests that the impact of either “positive” or “negative” media coverage of panic buying on the behavior itself may be negligible.

Nevertheless, this study highlights certain discrepancies and shortcomings in the coverage of panic buying by news outlets during the COVID-19 pandemic. Further research could focus on the following key areas:

(a) validation and refinement of the quality assessment tools outlined in this paper,

(b) qualitative and quantitative research in the general population to assess the influence of such reports on panic buying,

(c) longitudinal studies conducted during different “waves” of the COVID pandemic, to assess if the influence of media increases or decreases over time,

(d) adaptation of the content of these tools into media guidelines for the coverage of panic buying, with the help of stakeholders including the general public, journalists, and public health experts,

(e) implementation of these guidelines during subsequent “waves” of the pandemic or during other disasters likely to lead to panic buying,

(f) assessment of the impact of improved news content on subsequent panic buying.

From the perspective of the general public, improving the quality of news reporting in this domain would have three benefits: an increase in the level of trust in “mainstream” media (Pian et al., 2021), access to accurate information to counteract the “infodemic” of inaccurate or fake news (Kolluri and Murthy, 2021; Pian et al., 2021), and a reduction in psychological distress caused by exposure to unduly negative or sensationalized coverage (Price et al., 2022). Such effects would be more significant in countries with limited access to social media and a greater reliance on conventional news sources. In parallel with efforts to evaluate and improve the quality of media coverage, the general public should be informed about the need for responsible and limited consumption of news stories on topics of this sort, regardless of their source (Price et al., 2022).

Conclusion

Despite certain limitations, the current study highlights two important aspects of news media coverage of panic buying during the COVID-19 pandemic: first, analysis of the causes of panic buying by journalists appears to have become more widespread and nuanced, and second, a significant number of articles on panic buying contain textual or visual elements that might unwittingly act as a trigger or prompt toward panic buying. It is possible that the adoption of media guidelines on reporting incidents of panic buying may help to reduce this, and this study suggests that such guidelines could be derived from existing research on panic buying during the COVID-19 pandemic. Though this possibility still requires empirical validation, it should be given serious consideration as part of readiness or preparedness for any future widespread or long-lasting crisis during which panic buying is likely to occur. If such guidelines are implemented, empirical research in specific populations is required to assess the true magnitude of the effect, if any, of improved media coverage on the likelihood of panic buying at the individual and group level.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author Contributions

The sole author of the paper was responsible for its conceptualization, data collection, data analysis, writing, and editing.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcomm.2022.867511/full#supplementary-material

References

Al Zoubi, S., Gharaibeh, L., Jaber, H. M., and Al-Zoubi, Z. (2021). Household drug stockpiling and panic buying of drugs during the covid-19 pandemic: a study from jordan. Front. Pharmacol. 12, 813405. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.813405

Alchin, D. (2020). Gone with the wind. Australas. Psychiatry 28, 636–638. doi: 10.1177/1039856220936144

Arafat, S., Ahmad, A. R., Murad, H. R., and Kakashekh, H. M. (2021a). Perceived impact of social media on panic buying: an online cross-sectional survey in Iraqi Kurdistan. Front. Public Health 9, 668153. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.668153

Arafat, S., Kar, S. K., Marthoenis, M., Sharma, P., Hoque Apu, E., and Kabir, R. (2020b). Psychological underpinning of panic buying during pandemic (COVID-19). Psychiatry Res. 289, 113061. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113061

Arafat, S., Kar, S. K., Menon, V., Alradie-Mohamed, A., Mukherjee, S., Kaliamoorthy, C., et al. (2020c). Responsible Factors of Panic Buying: An Observation From Online Media Reports. Front. Public Health 8, 603894. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.603894

Arafat, S., Yuen, K. F., Menon, V., Shoib, S., and Ahmad, A. R. (2021c). Panic buying in Bangladesh: an exploration of media reports. Front. Psychiatry. 11, 628393. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.628393

Arafat, S. M. Y., Islam, M. A., and Kar, S. K. (2021b). “Mass media and panic buying,” in Panic Buying. SpringerBriefs in Psychology, Arafat S.Y., Kumar Kar S., Kabir R. (eds). Cham: Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-70726-2

Arafat, S. M. Y., Kar, S. K., Menon, V., Kaliamoorthy, C., Mukherjee, S., Alradie-Mohamed, A., et al. (2020a). Panic buying: an insight from the content analysis of media reports during the COVID-19 pandemic. Neurol. Psychiatr. Brain Res. 37, 100–103. doi: 10.1016/j.npbr.2020.07.002

Arafat, S. M. Y., Kar, S. K., Menon, V., Marthoenis, M., Sharma, P., Alradie-Mohamed, A., et al. (2020d). Media portrayal of panic buying: a content analysis of online news portals. Glob. Psychiatry. 3, 1–6.

Bentall, R. P., Lloyd, A., Bennett, K., McKay, R., Mason, L., Murphy, J., et al. (2021). Pandemic buying: Testing a psychological model of over-purchasing and panic buying using data from the United Kingdom and the Republic of Ireland during the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS ONE. 16, e0246339. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0246339

Berlin, F. S., and Malin, H. M. (1991). Media distortion of the public's perception of recidivism and psychiatric rehabilitation. Am. J. Psychiatry. 148, 1572–1576. doi: 10.1176/ajp.148.11.1572

Campbell, M. C., Inman, J. J., Kirmani, A., and Price, L. L. (2020). In times of trouble: A framework for understanding consumers' responses to threat. J. Consum. Res. 9, 1–16. doi: 10.1093/jcr/ucaa036

Chu, I. Y., Alam, P., Larson, H. J., and Lin, L. (2020). Social consequences of mass quarantine during epidemics: a systematic review with implications for the COVID-19 response. J. Travel Med. 27, taaa192. doi: 10.1093/jtm/taaa192

Chua, G., Yuen, K. F., Wang, X., and Wong, Y. D. (2021). The determinants of panic buying during COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 18, 3247. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18063247

Coleman, P. C., Dhaif, F., and Oyebode, O. (2022). Food shortages, stockpiling and panic buying ahead of Brexit as reported by the British media: a mixed methods content analysis. BMC Public Health. 22, 206. doi: 10.1186/s12889-022-12548-8

Cooper, M. A., and Gordon, J. L. (2021). Understanding panic buying through an integrated psychodynamic lens. Front. Public Health. 9, 666715. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.666715

Di Crosta, A., Ceccato, I., Marchetti, D., La Malva, P., Maiella, R., Cannito, L., et al. (2021). Psychological factors and consumer behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS ONE. 16, e0256095. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0256095

El-Shabasy, R. M., Nayel, M. A., Taher, M. M., Abdelmonem, R., Shoueir, K. R., and Kenawy, E. R. (2022). Three wave changes, new variant strains, and vaccination effect against COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 21, S0141-8130(22)00134-9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2022.01.118

Englund, T. R., Zhou, M., Hedrick, V. E., and Kraak, V. I. (2020). How branded marketing and media campaigns can support a healthy diet and food well-being for Americans: evidence for 13 campaigns in the United States. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 52, 87–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2019.09.018

Erokhin, V., and Gao, T. (2020). Impacts of COVID-19 on trade and economic aspects of food security: evidence from 45 developing countries. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 17, 5775. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17165775

Hair, E. C., Holtgrave, D. R., Romberg, A. R., Bennett, M., Rath, J. M., Diaz, M. C., et al. (2019). Cost-effectiveness of using mass media to prevent tobacco use among youth and young adults: the finishit campaign. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 16, 4312. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16224312

Huan, C., Park, S., and Kang, J. (2021). Panic buying: modeling what drives it and how it deteriorates emotional well-being. Fam. Consum. Sci. Res. J. 50, 150–164. doi: 10.1111/fcsr.12421

Islam, T., Pitafi, A. H., Arya, V., Wang, Y., Akhtar, N., Mubarik, S., et al. (2021). Panic Buying in the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Multi-Country Examination. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 59, 102357. doi: 10.1016/j.jretconser.2020.102357

Jin, X., Li, J., Song, W., and Zhao, T. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 and public health emergencies on consumer purchase of scarce products in China. Front. Public Health. 8, 617166. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.617166

Johns Hopkins University of Medicine (2022). Coronavirus Resource Center. Available online at: https://origin-coronavirus.jhu.edu/ (accessed January 28, 2022).

Kaur, A., and Malik, G. (2020). Understanding the psychology behind panic buying: a grounded theory approach. Glob. Bus. Rev. Dec. 13, 0972150920973504. doi: 10.1177/0972150920973504

Keane, M., and Neal, T. (2021). Consumer panic in the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Econom. 220, 86–105. doi: 10.1016/j.jeconom.2020.07.045

Keller, S. N., and Brown, J. D. (2002). Media interventions to promote responsible sexual behavior. J. Sex. Res. 39, 67–72. doi: 10.1080/00224490209552123

Kolluri, N. L., and Murthy, D. (2021). CoVerifi: A COVID-19 news verification system. Online Soc. Netw. Media. 22, 100123. doi: 10.1016/j.osnem.2021.100123

Lee, Y. C., Wu, W. L., and Lee, C. K. (2021). How COVID-19 triggers our herding behavior? Risk perception, state anxiety, and trust. Front. Public Health. 9, 587439. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.587439

Leung, J., Chung, J., Tisdale, C., Chiu, V., Lim, C., and Chan, G. (2021). Anxiety and panic buying behaviour during COVID-19 pandemic-a qualitative analysis of toilet paper hoarding contents on Twitter. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 18, 1127. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18031127

Li, J. B., Zhang, R., Wang, L. X., and Dou, K. (2021). Chinese public's panic buying at the beginning of COVID-19 outbreak: the contribution of perceived risk, social media use, and connection with close others. Curr. Psychol. Jul 23, 1–10. doi: 10.1007/s12144-021-02072-0

Liu, H., Liu, W., Yoganathan, V., and Osburg, V. S. (2021). COVID-19 information overload and generation Z's social media discontinuance intention during the pandemic lockdown. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change. 166, 120600. doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2021.120600

Logan, R. A., and Longo, D. R. (1999). Rethinking anti-smoking media campaigns: two generations of research and issues for the next. J. Health Care Finance. 25, 77–90.

Munsch, S., Messerli-Bürgy, N., Meyer, A. H., Humbel, N., Schopf, K., Wyssen, A., et al. (2021). Consequences of exposure to the thin ideal in mass media depend on moderators in young women: An experimental study. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 130, 498–511. doi: 10.1037/abn0000676

Ng, R., and Tan, Y. W. (2021). Diversity of COVID-19 news media coverage across 17 countries: the influence of cultural values, government stringency and pandemic severity. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 18, 11768. doi: 10.3390/ijerph182211768

Niederkrotenthaler, T., Voracek, M., Herberth, A., Till, B., Strauss, M., Etzersdorfer, E., et al. (2010). Role of media reports in completed and prevented suicide: Werther v. Papageno effects. Br. J. Psychiatry 197, 234–243. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.109.074633

O'Connell, M., de Paula, Á., and Smith, K. (2021). Preparing for a pandemic: spending dynamics and panic buying during the COVID-19 first wave. Fisc. Stud. 42, 249–264. doi: 10.1111/1475-5890.12271

Panneer, S., Kantamaneni, K., Akkayasamy, V. S., Susairaj, A. X., Panda, P. K., Acharya, S. S., et al. (2022). The great lockdown in the wake of COVID-19 and its implications: lessons for low and middle-income countries. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 19, 610. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19010610

Pearl, R. L., Dovidio, J. F., Puhl, R. M., and Brownell, K. D. (2015). Exposure to weight-stigmatizing media: effects on exercise intentions, motivation, and behavior. J. Health Comm. 20, 1004–1013. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2015.1018601

Pelham, B., Hardin, C., Murray, D., Shimizu, M., and Vandello, J. (2022). A truly global, non-weird examination of collectivism: the global collectivism index. Curr. Res. Ecol. Soc. Psychol. 3, 100030. doi: 10.1016/j.cresp.2021.100030

Pian, W., Chi, J., and Ma, F. (2021). The causes, impacts and countermeasures of COVID-19 “Infodemic”: a systematic review using narrative synthesis. Inf. Process. Manag. 58, 102713. doi: 10.1016/j.ipm.2021.102713

Price, M., Legrand, A. C., Brier, Z., van Stolk-Cooke, K., Peck, K., Dodds, P. S., et al. (2022). Doomscrolling during COVID-19: the negative association between daily social and traditional media consumption and mental health symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol. Trauma. 10.1037/tra0001202. doi: 10.1037/tra0001202

Pronin, E., Lin, D. Y., and Ross, L. (2002). The bias blind spot: perceptions of bias in self versus others. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 28, 369–381. doi: 10.1177/0146167202286008

Qiu, W., Chu, C., Mao, A., and Wu, J. (2018). The impacts on health, society, and economy of SARS and H7N9 outbreaks in china: a case comparison study. J. Environ. Public Health 2018, 2710185. doi: 10.1155/2018/2710185

Rajkumar, R. P. (2021). A biopsychosocial approach to understanding panic buying: integrating neurobiological, attachment-based, and social-anthropological perspectives. Front. Psychiatry 12, 652353. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.652353

Rajkumar, R. P., and Arafat, S. M. Y. (2021). Model driven causal factors of panic buying and their implications for prevention: a systematic review. Psychiatry Int. 2, 325–343. doi: 10.3390/psychiatryint2030025

Reporters Without Borders (2021). World Press Freedom Index: Index Details. Available online at: https://rsf.org/en/ranking_table (accessed January 28, 2022).

Roukema, B. F. (2021). Anti-clustering in the national SARS-CoV-2 daily infection counts. Peer J. 9, e11856. doi: 10.7717/peerj.11856

Schippers, M. C. (2020). For the greater good? the devastating ripple effects of the Covid-19 crisis. Front. Psychol. 11, 577740. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.577740

Schmidt, S., Benke, C., and Pané-Farr,é, C. A. (2021). Purchasing under threat: Changes in shopping patterns during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS ONE. 16, e0253231. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0253231

Sheng, X., Ketron, S. C., and Wan, Y. (2021). Identifying consumer segments based on COVID-19 pandemic perceptions and responses. J. Consum. Aff. Sep. 13, 1–34. doi: 10.1111/joca.12413

Stead, M., Angus, K., Langley, T., Katikireddi, S. V., Hinds, K., Hilton, S., et al. (2019). Mass media to communicate public health messages in six health topic areas: a systematic review and other reviews of the evidence. NIHR J. Library. 7. doi: 10.3310/phr07080

Stevens, H. R., Oh, Y. J., and Taylor, L. D. (2021). Desensitization to fear-inducing COVID-19 health news on twitter: observational study. JMIR Infodemiol. 1, e26876. doi: 10.2196/26876

Stryker, J. E. (2003). Media and marijuana: a longitudinal analysis of news media effects on adolescents' marijuana use and related outcomes, 1977-1999. J. Health Commun. 8, 305–328. doi: 10.1080/10810730305724

Taylor, S. (2021). Understanding and managing pandemic-related panic buying. J. Anxiety Disord. 78, 102364. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2021.102364

Thakur, V., Bhola, S., Thakur, P., Patel, S., Kulshrestha, S., Ratho, R. K., et al. (2021). Waves and variants of SARS-CoV-2: understanding the causes and effect of the COVID-19 catastrophe. Infection Dec. 16, 1–16. doi: 10.1007/s15010-021-01734-2

World Health Organization (2008). Preventing Suicide: A Resource for Media Professionals. Geneva: WHO Press. Available online at: https://www.who.int/mental_health/prevention/suicide/resource_media.pdf (accessed January 12, 2022).

Xiao, H., Zhang, Z., and Zhang, L. (2021). An investigation on information quality, media richness, and social media fatigue during the disruptions of COVID-19 pandemic. Curr. Psychol. Sep. 7, 1–12. doi: 10.1007/s12144-021-02253-x

Keywords: panic buying, COVID-19, media reporting, social contagion, social learning, guidelines, infodemic, fake news

Citation: Rajkumar RP (2022) Do We Need Media Guidelines When Reporting on Panic Buying? An Analysis of the Content of News Reports During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Commun. 7:867511. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2022.867511

Received: 01 February 2022; Accepted: 09 May 2022;

Published: 27 May 2022.

Edited by:

Russell Kabir, Anglia Ruskin University, United KingdomReviewed by:

S. M. Yasir Arafat, Enam Medical College, BangladeshShabbir Syed Abdul, Taipei Medical University, Taiwan

Isyaku Hassan, Sultan Zainal Abidin University, Malaysia

Lusy Asa Akhrani, University of Brawijaya, Indonesia

Copyright © 2022 Rajkumar. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ravi Philip Rajkumar, cmF2aS5wc3ljaEBnbWFpbC5jb20=

Ravi Philip Rajkumar

Ravi Philip Rajkumar