- 1Media Studies Department, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

- 2School of Journalism and Media Studies, Rhodes University, Grahamstown, South Africa

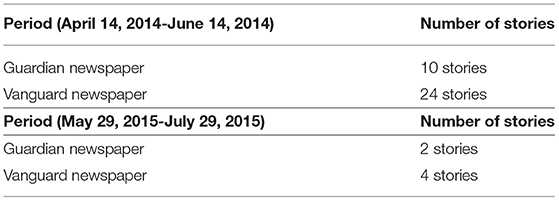

This study examines Nigeria's political leaders' framing during the #BringBackOurGirls movement campaign using two selected national newspapers in Nigeria, i.e., the Guardian and the Vanguard newspapers. Using 46 news stories culled during the periods of April 14, 2014, to June 14, 2014, and May 29, 2015, to July 29, 2015, which represent two significant eras, i.e., when the schoolgirls were abducted, and when there was a change in government, the study argued that four frames of government failure, the desperation of citizens, politicization of government actions and heroism were dominant in both presses reportage. During the first period of study, both presses were critical of President Goodluck Jonathan and his inability to secure the release of the abducted Chibok schoolgirl as they used frames of “liar”, “clueless”, and “failure” amongst others to characterize his government actions and inactions. However, during the second study period, both presses were less critical of President Buhari as they ascribed the “hero” frame to him due to his vast military experience. Nevertheless, the ideological position of both newspapers influenced their reportage as Guardian news stories provided depth analysis, while Vanguard newspaper stories lacked depth.

Introduction

On April 14 2014, a militant group called Boko Haram, which means “Western education is forbidden,” abducted over 270 schoolgirls from Chibok Secondary School, Borno State, Nigeria. The abduction of the Chibok Girls sparked an international outcry and led to the establishment of “#BringBackOurGirls,” movement which later became a global phenomenon due to their pressure on the government to rescue the abducted schoolgirls and advocate for the rights of girls to education.

Much research has been conducted on the #BringBackOurGirls movement since its inception in 2014. Most of these researches have focused on the nature of the movement and citizens' relationship with the state (see Loken, 2014; Khoja-Moolji, 2015; Berents, 2016), others looked at the discourses emanating from the movement, whether gender, politics, and national security (Chiluwa and Ifukor, 2015; Akpojivi, 2018) amongst others. Few or no studies have examined the Nigerian press frame of the political leaders during the abduction, especially since the abduction became a dominant political issue during the administration of two presidents, that is, President Goodluck Jonathan and Muhammadu Buhari. According to Brandes and Engel (2011), the study of African movements, their leaders and how they are represented in the media is most often neglected in the field of social sciences and humanities.

Therefore, the need to understand how the Nigerian press framed the political leadership (their actions/inactions) during the abduction. Campus (2013) argues that media have limited capacity to cover the political class and events in society. However, via their available coverage, they construct realities that shapes public opinion and attract attention to specific issues (Chari, 2013). Consequently, this study seeks to examine how two key national dailies in Nigeria, i.e., “The Guardian Newspaper” and “the Vanguard Newspaper,” represented the political leadership of President Jonathan and President Buhari. Their administrations had to deal with the #BringBackOurGirls movement and their campaign to release the abducted girls. The study seeks to identify ways in which both dailies framed stories surrounding the different governments handling of the girls' abduction and compare such frames. The purpose is to ascertain if there are common patterns, or not, between the reportage despite the different ideological editorial positions of the dailies. In addition, the study seeks to determine the media frames from both presses and if their editorial positions influenced them.

Therefore, the study seeks to address the following research questions:

• How have the Nigerian presses, especially “The Guardian Newspaper” and “Vanguard Newspaper,” framed the political leadership handling of the #BringBackOurGirls abducted girls?

• How did the ideological editorial positions of the “The Guardian Newspaper” and “Vanguard Newspaper” impact on the way both presses framed the political leadership (actions/inactions) during the #BringBackOurGirls sage?

Why The Guardian and Vanguard Newspapers?

The Nigerian press is regarded as the “vanguard of Nigeria's democracy” due to the critical role they have played from pre-independence to the post-independence era. Hence, the assertion amongst scholars that the Nigerian press is the most vocal and well-developed in Africa (Adesoji and Hahn, 2011; Akpojivi, 2018). Nyamnjoh (2005), while attesting to the above, stated that the press in Nigeria could be viewed as the advocate and defender of Nigeria's democracy.

Historically, the press in Nigeria has been privately owned based on its antecedences of the early press being founded and used by individuals to propagate religious and political communications (Bourne, 2018), and this has continued in the post-independence era. Amongst the numerous press organizations in Nigeria, The Guardian and Vanguard newspapers are widely regarded as dominant national dailies with strong credibility (Adaugo and Roper, 2021). According to Adaugo and Roper (2021), the most trusted brand in dailies are Vanguard with 82% and Guardian newspaper with 80% with a wide circulation figure. Although circulation figures of dailies are shredded in secrecy due to advertising reasons, both dailies claimed to have a readership of one million- (Guardian Newspaper, 2019) and 120,000 circulation by Vanguard (Vanguard Newspaper, 2017) with an active online presence (website and social media). Based on these reasons, both dailies were selected for the study.

The Guardian newspaper, located in Lagos, was established in 1983 by Alex Ibru, an entrepreneur. The newspaper is regarded as a liberal newspaper and is the pioneer for introducing very high-quality journalism in Nigeria (Olaniyan, 2014). Therefore, the newspaper is known for its critical reportage and editorial content and has over a million daily readership (Guardian Newspaper, 2018). The newspaper is mostly read by the elite and middle class (Olaniyan, 2014). Consequently, it is considered the most respected newspaper in Nigeria.

On the other hand, the Vanguard newspaper located in Lagos also was established in 1984 by Sam Amuka-Pemu, a veteran journalist. The daily is known for carrying both hard and soft news and is read mostly by the middle-class, hence the nickname of it being a “family newspaper.” Both newspapers are privately owned and can be regarded as free from political control but are subjected to economic control or pressure due to the competitive nature of the print industry in Nigeria (see Akpojivi, 2018). From the above, it can be argued that both newspapers share a similar history, i.e., privately owned and have played significant roles in Nigeria's democracy during the military regime. Therefore, the need to ascertain how both dominant newspapers framed the Nigerian government leadership handling of the #BringBackOurGirls movement and their quest for the release of the abducted girls since they have a wider reach due to their circulation and pedigree of having played an active role in the democratization processes of the country. This study would have benefited greatly by comparing the frames from privately-owned national newspapers against stated-owned national newspapers. However, there are no national newspapers owned by the Federal government, as the press in Nigeria has a tradition of being privately owned right from the precolonial era till date (Omu, 1996). However, the few available newspapers owned by some state governments are not national but limited to the region of the respective states that owned them e.g., “the Observer” owned by the Edo State government, and “the Standard” owned by Plateaus State operate and covers stories about their immediate environment and have no national outlook. Therefore, the decision to compare frames from privately-owned national dailies such as The Guardian and Vanguard only.

Literature Review

There is vast literature around the subject of #BringBackOurGirls. This literature focus on the ideology of the movement and activism of the movement in bringing about social change (see Chiluwa and Ifukor, 2015; Abdullahi and Abdul, 2019; Akpojivi, 2018). However, little research has been done around the representation of the government handling of the movement and how the ideological orientation of the media has influenced such a representation. Therefore, this study will fill this gap in the literature and will use media framing and social construction theories as theoretical frameworks and news production literature in understanding how two privately owned presses represented the government in their handling of the abduction of the girls, and how their ideological background influenced their representation of the movement and government during the abduction of the schoolgirls on April 15, 2014.

News Production

There is no universally acceptable definition of news production as it has been approached differently due to the conceptual issue of when news production starts. According to Wilson, news production starts “as soon as a journalist sees and hears of something newsworthy” (Wilson, 1996, p. 29). On the other hand, Harrison argues that news is produced by “professionals working in a routine day-to-day manner within a news organization” (Harrison, 2006, p. 99). Both definitions place news production as an intricate process carried out by a professional such as journalists, editors etc. However, Hanitzsch and Hoxha (2014) argue that the emergence of the internet is changing and reshaping the concept of journalism and news production as the internet impacts journalism processes and practices and what is considered news. Furthermore, rapid growth and development in information and communication technology have fundamentally changed the very nature of news production and consumption (Lee and Tandoc, 2017). According to Singer et al. (2011), these changes have further strengthened participatory journalism, which ultimately nurtures news production.

Nonetheless, Domingo (cited in Hanitzsch and Hoxha, 2014) argues that irrespective of this, every news production must undergo five stages of access and observation, selection and filtering, processing and editing, distribution, and interpretation. A curious look at these processes/stages of news production shows that framing, i.e., selection and filtering is an integral part of the process, which is at the heart of any news production. Lee and Tandoc (2017) see news selection and framing as the process of determining whether an event or piece of information will be reported. Therefore, the idea that news production is not value-free, as its motive is to attract readers and sell, framing is critical to attracting readership/viewership. Hence, the idea is that news selection is influenced based on the importance of the story and framed in a way that will resonate with the audience.

Paulussen et al. (2017) argue that mainstream media have started integrating content from new media platforms into their production. Such integration is for commercial purposes. Many scholars have focused on the role of new media and issues around news publishing and distribution (see Anderson, 2011; Hermida et al., 2011; Thurnma, 2011). Therefore, Ornebring (2010) and Conboy and Eldridge (2014) argue that news production has always been amplified by technological innovations and content from new platforms. Fosu and Akpojivi (2015), while extending this thought, argue that the media in most postcolonial states have embraced the convergence of content.

On the other hand, commercial pressures influence news production due to the emergence of digital media platforms and the active competition between media organizations in a fragmented media space. Currah (2009), while buttressing the above argument, argues that the digital disruption following the emergence of ICT has transformed journalism and has weakened the economic foundation of news publishing. This means that digital press and online advertisers compete and take funds from mainstream media. According to Kperogi (2012), while drawing from the Nigerian experience, argues mainstream media have witnessed drop in revenue following the establishment of online newspapers as advertisers spend more money on online news organizations and on social media campaigns. Therefore implying stiff competition for revenue to survive; otherwise, their ability to fulfill their normative responsibility will be severally affected (see Onyenankeya and Salawu, 2020).

Consequently, to survive the competitive media environment coupled with the decline of readership, these privately-owned media have to “adopt the logic of selling lucrative audiences to advertisers” (Wasserman, 2010, p. 3) via sensationalism. Wasserman added that sensationalism takes the form of “headline, graphic design or editing techniques, which are used to stimulate the desired responses” (Wasserman, 2010, p. 16) to have a competitive advantage. To this end, media organizations (press and broadcast) could easily fall victim to embracing sensationalism in their reportage, and the abduction of the Chibok girls and the #BringBackOurGirls campaign could become an easy bait to promote sensationalism due to the sensitivity of the issue and its broader implications on Nigeria's socio-cultural, political and economic sphere. Thereby steering the attention of the public to issues the media considered relevant by ignoring others (Fursich, 2010). This act simplifies, objectifies, and commodifies the news process, which Sundar (1998, p. 56) called the ‘bread' and ‘butter' of news stories because they (media) provide and determine relevance and credibility. Consequently, the abduction of the Chibok schoolgirls and the activities of the #BringBackOurGirls movement are veritable news items. The media only need to create awareness about the social issues that the movement was campaigning about and act as a tool for pushing for social change, but also a veritable economic tool due to the ways stories could be framed to attract readership.

As Van Hout and Jacobs (2008, p. 60) argue, “we look at journalists as interpretive agents and newswriting as a form of reproductive writing which transforms news discourses such as press agency copy, press releases and interview notes into a single narrative, framed as an authoritative account of a news event.” This argument takes an approach from Beeman and Peterson (2001, p. 159) concept of interpretive practice, “the ways that routine procedures, cultural categories and social positions come together in particular instances of interpretation.” When applying this concept to news production studies, it “turns our attention from the structures that organize action to the contingency that is always present in media production and the specific momentary, negotiated processes by which agency is employed to challenge, change or reproduce structure” (Peterson, 2003 p.186). Therefore, the need to examine how Guardian and Vanguard newspapers interpret the events of the Chibok schoolgirls' abduction and the activities of the political leaders in securing the release of the abducted girls and their engagement with the #BringBackOurGirls movement. Such an interpretation, according to Mortensen (2018), entails “post-factual” representation and reporting as the need for profit by the media and the integration of content from a fragmented news source such as new media/social media has called for the need to unpack/understand how the media frames and represent a news event and why.

Theoretical Framework

Media framing can be considered one of the vital theories in understanding media effects and public behavior to communication (Druckman, 2001) as media framing influences and shape people's understanding of social reality or events by the way news is produced, i.e., the process of selecting and omitting components making up a news story (Reese and Lewis, 2009). Chari (2013 p. 292) argues that the media can do this through the “amount of exposure or placement given to an issue and the overall accompanying headlines and visual effects, engender certain ways of interpreting reality.” This means that the public understanding of society's events and reality is constructed based on how the media communicate certain information. Entman, while buttressing the above, posited that “to frame is to select aspects of perceived reality and make them more salient in communicating text in such a way as to promote a particular problem definition, causal interpretation, moral education and/or treatment recommendation for the item prescribed” Entman (1993 p. 52).

This implies that the public perception of society is derived from the perspective of the media, the kind of words used, headlines and graphic representation. Thereby establishing the sociological dimension of media framing in understanding media framing. According to Druckman (2001 p. 227), the sociological dimension of framing focuses on journalistic perception and media ideology in shaping and constructing reality through “the words, images, and the presentation style of the information.” Thus, making media framing a value-driven process as a media house's ideological position and orientation will influence the journalists' perception and reportage. As a journalist's perception of reality will shape how s/he constructs reality, journalists perception is often shaped by the ideas of the media (Druckman, 2001).

Therefore, framing theory rooted in sociological perspective is crucial in understanding how media ideologies and journalists perception shapes the (un)bias construction of reality. This idea juxtaposes with the social construction theory that the construction of reality is dependent on the media social representation and construction of reality. As Santos (2015) describes, human understanding and perception of reality is from cultural and social norms. The media are germane to constructing and disseminating these social and cultural norms (see Chari, 2013). Therefore, within the context of this study, these theories will help accentuate how the ideological editorial position of the Guardian and Vanguard newspapers shaped their framing of the political leaders' handling of the abducted Chibok schoolgirls and the #BringBackOurGirls engagement with the state. These frameworks are important in understanding the role of the media in constructing the everyday realities of society and how such a reality is affected by the systemic and cultural context in which the media exist.

Brief Synopsis of #BringBackOurGirls Movement

#BringBackOurGirls movement was established in Nigeria following the abduction of over 276 schoolgirls from Chibok Secondary School, Borno State, on April 14, 2014, by the militant group called Boko Haram, which means “Western education is forbidden” (Akpojivi, 2018). Before the abduction, Nigeria had been battered with issues of terrorism by Boko Haram on both hard and soft targets. For instance, prior to the abduction of the Chibok schoolgirls, Boko Haram killed 59 schoolboys at Federal Government College on February 25, 2014, and bombed the United Nations building in Abuja on Friday, August 26, 2011.

Their nefarious activities coupled with the non-charlatan attitude of then-President Goodluck Johnathan toward these events, led to the formation of the #BringBackOurGirls movement. According to Dr Obiageli Ezekwesili, the co-founder of the #BringBackOurGirls movement held that the movement was established following the nonchalant attitude and salience of the Nigerian state to issues confronting the Nigerian state (BBC HardTalk., 2014). The movement received wide coverage from both international presses like BBC, Aljazeera, CNN and national presses, thus becoming a global phenomenon. Therefore, the need to understand how the dominant presses in Nigeria, i.e., The Guardian and Vanguard newspapers, represented the governments' reaction to the girls' abduction and their engagement with the movement and identify factors that might have contributed to such representation.

Methodology

This study adopted a qualitative content analysis to examine the representation of political leaders during the #BringBackOurGirls campaign between the timeframe of April 14, 2014, to June 14, 2014, and May 29, 2015, to July 29, 2015. According to Krippendorff (2004, p. 21), content analysis provides the researcher with “knowledge…insights and representation of facts and a practical guide to action,” as such knowledge is invaluable in arriving at a valid conclusion from the collected data. Therefore, making it a valuable methodological tool in this study.

This timeframe was purposively selected because they represented the first two months of the #BringBackOurGirls movement existence and their campaign/engagement with the Nigerian government for the release of the girls (April 14, 2014–June 14, 2014), and the first two months of the movement's engagement within the new administration of President Muhammadu Buhari (May 29, 2015-July 29, 2015). The rationale for examining these periods is that according to Della-porta and Tarrow (2005), the media are central to any social movement as they help spread information. Likewise, Campus (2013) argues that media coverage of political leaders and events are invaluable in creating awareness and influencing the public realities. Therefore, the movement and political leaders would have wanted a fair reportage of their activities to reach out to Nigerians to buy into their ideas and activities, thus influencing the public perception of them positively. Chiluwa and Ifukor (2015) argue that the public discourse during this period was that of crisis, and the media might have influenced such discourse. Thus, political leaders (government at the time) would want to change this narrative, as such a narrative is not good for the government's reputation. Akpojivi (2018), while buttressing the above, argued that for the first time in the history of Nigeria, there was a transition from one government to another -opposition- and the events of #BringBackOurGirls might have played a significant role in this change. Hence, the need to examine if the representation of the political leaders differs.

This study did not examine the recent timeframe because a search on the movement between 2017 and 2019 resulted in a very limited result. The movement received little or no coverage, as the available coverage centered on the personalities behind the movement and their current political ambitions. According to Sesay Isha of CNN, while attesting to this, the world has shifted its gaze from the #BringBackOurGirls to other salient issues (CNN, 2015).

The corpus for the study was derived from two leading national dailies in Nigeria, i.e., The Guardian and The Vanguard. During the periods, news stories on #BringBackOurGirls were searched using keywords of # BringBackOurGirls and #BBOG and analyzed. Stories that were culled from international agencies like AFP were excluded because the study is not interested in how these international agencies reported or framed the political leaders and their engagements with the #BringBackOurGirls campaign. Likewise, opinion pieces were also excluded as the study is interested in how both presses represent the political leaders' engagement with the movement, not from the perspective of an opinion piece. A total of 46 stories was collected during the timeframe using the code or search word of #BringBackOurGirls or #BBOG in identifying news stories about the political leaders' engagement with the movement, the movement campaigns and subsequent movement's engagement with the political leaders' (see Table 1 for breakdown).

The collected news stories were analyzed using framing analysis. Kuypers (2009, p. 181) argues that framing analysis is a type of rhetorical analysis that looks at persistent themes that cut across text over time. In addition, he stated that this frame “induces us to filter our perceptions of the world in particular ways, essentially making some aspects of the multi-dimensional reality more noticeable than other aspects.” Consequently, since this study is interested in how the presses in Nigeria represent/framed the political leadership during the abduction of the Chibok schoolgirls and the subsequent #BringBackOurGirls movement, framing analysis becomes the most suitable analytical approach.

Findings

A lucid review of news stories during the study timeframe shows that both national newspapers approached the coverage of the political leaders differently. While Guardian newspaper focused more on the actions and inactions of the government and other stakeholders, Vanguard newspaper, on the other hand, focused more on the activities of the movements and, to some extent, government actions toward the abducted schoolgirls. In addition, there was a significant difference in the style of reportage as Guardian newspaper reportage was more detailed, written in a very formal way while Vanguard most often lacks details but written in a less formal way. These differences speak of the ideological difference between both presses. Guardian newspaper is regarded as the most educative and professional newspaper in Nigeria due to its reputation for 'high-quality journalism' and the belief that it is targeted at the 'educated elite'. In contrast, Vanguard newspaper is widely considered as a family newspaper with the writing style and language more accommodating for all.

Despite these differences, the frames from both presses were similarly. The themes that emerged from the frames during the first period of April 14, 2014, to June 14, 2014, during President Jonathan's regime, were government failures, citizens' desperation, and politicization of government's actions.

Government Failure

Both presses framed the government as failure due to their inability to protect the kidnapped schoolgirls, rescue the schoolgirls from Boko Haram, and failure to determine the number of schoolgirls kidnapped. Words, such as “clueless,” “lies,” “pled,” “slow” and “hopeless” were used to framed the state. For example, the Guardian newspaper carried news stories titled “Only 14 of 129 abducted girls found” on April 18, 2014, and “Search for 99 Abducted School Girls Fruitless” on April 19, 2014. In both stories, the government of President Goodluck Jonathan was portrayed as a failure. This failure is seen in the inability of the government to ascertain the precise number of girls abducted as the number kept increasing. For instance, the stories highlighted the differences in numbers of abducted schoolgirls from the government (federal and state) and school. In addition, the government was considered a failure due to their inability to rescue the abducted schoolgirls. For instance, the students' principal was quoted in the story dated April 18, 2014, that “the girls were forcefully loaded into trucks and Hilux vehicle are yet to be found.” This statement decries the government's failure to protect and secure Nigerians' lives, which is the primary responsibility of government as enshrined in the constitution.

Furthermore, the newspaper represented the government as “liars,” attempting to give false information to the public about the safety of the girls and rescue the abducted schoolgirls. For instance, in a story dated April 18, 2014, the Nigerian government and the military asserted that some girls have been rescued and returned to their parents, and this information was later discovered to be a lie. According to the story, “if it is true that the girls have been freed, we want the military to show them on television, we want to hear their voices…there is nothing in the military statement that is true” (Guardian Newspaper, April 18, 2014). By calling the government and military to show the rescued schoolgirls on television, they called the government a liar. The newspaper, while further supporting this frame, cited community members. For example, while citing the principal of the abducted schoolgirls, “the principal wonder how such a large number of girls would be found and nobody sees them either in Chibok town or with their parents.” In addition, a resident was quoted by saying “it is a shame that Nigerian authorities can go this far in misleading the people and the international community…only God knows the trauma those innocent girls are passing through in the bushes but someone is lying that they are safe,” and the residents/community members demanded an apology from the government for the lies. In another news story dated April 22, 2014 titled “Only 39 of 134 abducted girls have returned, say parent,” this “liar” frame was further expounded, as the parents disputed the figures of the government. According to the story “parents of abducted female students of the Government Girls Secondary School, Chibok in Borno state have said only 39 out of the 134 kidnapped girls escaped….that contrary to government figure of 44 escaped girls, 95 students are still being held by the Boko Haram insurgents.” Furthermore, the story citing a parent added “the truth of the matter is that only 39 out of about 134 students have been rescued and we want to emphasize that we are not happy with this development” (Guardian Newspaper, April 22). The phrases, used in the story such as “truth,” and “emphasize” are to buttress the fact that the government was lying in their claims of rescue. Lastly, the story ended, citing a resident who posited that the girls would have been rescued if the military were in the Sambisa forest, where the girls are allegedly held. Such a statement further represents the government as a liar which claimed that the government and military are working and searching for the abducted schoolgirls.

Similarly, Vanguard newspaper represented the government as a failure using words like “clueless,” “hopeless,” and “insensitive.” In a story dated May 05, 2014, the newspaper expressed the hopelessness of the Nigerian government in rescuing the abducted schoolgirls. According to the story, all hope is lost due to the inability of the government to take immediate action in securing the release, consequently the inability of the government to ascertain the precise location where the girls are being held. It can be argued that the phrases used “clueless, dimmed” and “loss” within the news story emphasizes the failure of President Goodluck Jonathan's government. Furthermore, in a story titled “is #BringBackOurGirls being politicized?” Dated June 04, 2014, not only was President Goodluck Jonathan portrayed as “clueless,” his government was characterized as “incompetent.” The news story attesting to the above stated that “you know what annoys me? We are all talks and no action. If we mean business, why can't we mobilize and march to Sambisa forest and chase those idiots out? We will not try it because we no get liver said Gbenga.”

The use of words such as “talks and no action” “if we mean business” shows the government's incompetency that has resulted in the failure of the government to rescue the abducted schoolgirls and address the Boko Haram Crisis. The sentence ended with a “Pidgin English word “no liver”-broken English lingua franca widely spoken- that the Nigerian state does not have the stamina to withstand Boko Haram.

Citizens' Desperation

This frame highlights the citizens' desperation to secure the release of the abducted schoolgirls without government interventions. This desperation is an offshoot of the government's inability to protect the schoolgirls and secure their release. This citizen's desperation is framed in two ways from the news stories, i.e., protest action and citizens own search and rescue mission. In a story titled “Teachers, students protest over abducted schoolgirls” by the Guardian newspaper, dated May 23, 2014, the story held that the frustration of the teachers all over the country has led to them breaking their silence and demanding “safe and unconditional release” of the schoolgirls. While phrases like “silent wait,” “slow response,” and “innocent children” were used, these phrases speak of desperation by other stakeholders like teachers to secure the release of “innocent” schoolgirls. This frame of protest was evident in Vanguard news stories as a story titled “#BringBackOurGirls: Youths, Students give Johnathan 40 days Ultimatum,” words like “hunger strike,” “nationwide protest,” and “mobilize” were used. According to the story, the government of President Goodluck Johnathan was given 40 days ultimatum by youths and students from Borno State (the state where the students were abducted) to secure the release of the abducted schoolgirls; otherwise, they will embark on a nationwide protest, coupled with a hunger strike. This speaks of desperation on the part of the citizens and disappointment with the state over their failure to act and secure the girls' release.

Similarly, in a story titled “Grief over Chibok girls on Children's Day” dated May 28, 2014, Guardian newspaper reported that instead of the usual school match and parade that characterize children's day celebration, the children's day was a “protest match” for the release of the abducted schoolgirls. In addition, in another story titled “Children's Day: It's all gloom over Chibok girls” dated May 27, the paper reported all over the country were adorned in red in solidarity with the over 200 abducted children. These stories framed the children's day as a day of ‘protest' against government's inaction toward the release of the abducted schoolgirls.

Furthermore, the Guardian newspaper framed the citizens' desperation as led to them instituting their search and rescue mission. In stories titled “Hunters, others rescue 80 abducted school girls” (17/04/2014), “search for 99 abducted schoolgirls fruitless” (19/04/2014) and “only 39 of 134 abducted girls have returned, say parents” (22/04/2014). From these stories, phrases like “member rescue team,” “vigilance group,” “local hunters,” and “parent search” all speak about the desperation of the citizens to embark on their search and rescue mission in order to secure the release of the girls. According to the story dated April 22, while citing the parents of the abducted girls posited that “we were in the bushes of Sambisa with over 200 volunteers who only had cutlasses, bows and arrows and sticks…until we approached a good Samaritan we advised us to return back as we are approaching a death trap set by the insurgent.” The use of words such as cutlass and bows and arrows by parents in search of abducted schoolgirls in the deadly Sambisa forest shows the parent's desperation in rescuing the schoolgirls. The story highlights the inadequacies and failure of the government as instead of the military invading the forest with guns and all kinds of military weaponry; the citizens are invading the forest. The story is laced with phrases such as “cutlass,” “sticks,” and “bows and arrows” to show the failure of the government and the desperation of parents in the search and rescue mission of their daughters.

Politicization of the Government Action

There was evidence of the politicization of government actions and inactions from both newspapers. This frame speaks of the infighting between the government, the movement and other stakeholders “opposition party” concerning the abduction of the schoolgirls. For instance, the following news stories titled “#BringBackOurOurGirls: We don't know location of abducted girls-GEJ” (Vanguard Newspaper, 2014d, 05/05/2014d), “Chibok Girls: Mbu bans #BringBackOurGirls Protests in Abuja” (Vanguard Newspaper, 2014c, 02/06/2014c), “is #BringBackOurGirls being politicized?” (Vanguard Newspaper, 2014d, 04/06/2014d), ‘#BringBackOurGirls: I am not slow-GEJ (Vanguard, 22/05/2014), “#BringBackOurGirls to Jonathan: Arise, tackle our common enemies” (Vanguard, 06/06/2014), “No deal yet with B'Haram over Abducted girls” (Guardian, 27/05/2014) and “Maku, Marwa condemn Nyako's letter to northern governors” (Guardian, 24/04/2014), all these stories highlight the politicization of government actions and inaction. As government response (action) and failure to rescue the girls (inaction) are used for political goals. Phrases such as “criticism,” “incite,” “enemy,” “lack of trust,” “unfair,” “slow reaction,” “resigned,” “politicized” and “infiltrate” amongst others were used. These phrases were used to settle political goals in which the government of President Goodluck Jonathan was labeled “incompetent” and the call for him to resign. In addition, the collective action of the government formed the basis for politicization. For instance, in a story dated June 04, 2014, Vanguard newspaper cited a respondent who stated, “I am getting tired of the whole thing. There is so much politics surrounding the abduction of the girls, said Angel. Please get me right. I did not say they are not missing. I am simply saying that it has been politicized. Politicians are using it to score cheap political points.” This idea of the movement being politicized and used to score cheap political points could be seen in the stories about the decision of the police to ban the #BringBackOurGirls protest in Abuja, as the decision was not only criticized but was capitalized upon by other stakeholders like the opposition party to politicize the abduction and blame the collective action of the government including the police. For instance, in an article dated April 24, 2014, the Guardian newspaper reported that some stakeholders in the northern region of Nigeria feel that “President Goodluck Jonathan was promoting genocide in the north through its fight against the insurgency aimed at depopulating the North.”

Nevertheless, under the second period (May 29, 2015-July 29, 2015) under President Muhammadu Buhari, the Vanguard newspaper's representation of the government changed significantly as President Buhari was portrayed as the “hero” and the person that has the capacity to “rescue” the kidnapped girls which the previous government was incapable of.

In one Guardian article titled “Buhari meets BBOG campaigners, vows to defeat Boko Haram,” phrases such as “promise', “crush,” “glory,” “pedigree,” “seriousness” and “performance” was reoccurring. Similar phrases of “seriousness,” “best, strategy,” were found in the Vanguard newspaper as in a news story titled “BringBackOurGirls: Buhari laments state of Nigeria's military.” According to the Vanguard news story, “I think you will agree that the present government take the issue very seriously…as strategy and tactics have been drawn, as the Federal government will spare no resources in rescuing our 219 Chibok girls as promised by the President.” From both newspapers, the frame was on the new counter-insurgence strategy of President Buhari due to his vast military experience and the belief that this would be useful in securing the release of the girls.

It should be noted that this positive reportage was linked to the president meeting with the #BringBackOurGirls movement, which the former president refused to do. According to a quote from one of the news stories, “luckily, Buhari can be said to be on the same page as the campaigners in view of the warm reception accorded the team last week and the undiluted assurance of the president that his government would face the subject squarely” (Vanguard, July 12, 2015). The above quote, coupled with other news stories, talk about how the military experience positioned the new government as having all it takes to rescue the girls, hence the allure of hope.

Discussion

From the above, it can be argued that both dailies representation of the Nigerian political leaders during the abduction of the Chibok girls and the subsequent #BringBackOurGirls campaign is rooted in the sociological framing as words, phrases and presentation style were used to construct and convey social realities to the public (Druckman, 2001). There were some similarities in their reportage as the dailies criticized the government of President Jonathan in its engagement with the #BringBackOurGirls and in securing the release of the girls, they believed in the abilities of President Buhari to secure the release of the schoolgirls. The similarity in their reportage raises the fundamental question of why a liberal newspaper like the Guardian, known for quality journalism, will have similar frames to a family-oriented newspaper like the Vanguard? While this similarity can easily be attributed to both presses' private and commercial nature, seeking to attract readership by using frames that will appeal to the public. However, I seek to argue that despite the different ideological positions of both presses, both presses framing were influenced by the public opinion at the time. According to Baum and Potter (2008), the press is constantly framing news in response to the competing requirements of the public. This means that public opinion influences the media and their reportage and how they frame a story. Chiluwa and Ifukor (2015) argue that the public opinion following the abduction of the schoolgirls was that of crisis as Nigeria had been confronted with numerous soft and hard targets from Boko Haram (see Akpojivi, 2018). Therefore, the need for the presses to frame stories and events along with public opinion. Okonjo-Iwela (2018), while further buttressing this fact, held that despite the numerous efforts of the government of President Jonathan in tackling Boko Haram and securing the release of the abducted girls, the Nigerian media refused to frame the government in a positive light but instead overlooked such narrative.

However, despite the similarity, their approach differs significantly. The Guardian offered in-depth analysis and coverages and used formal English language in line with their ideological position, unlike the Vanguard, who were quick to characterize government as fragile and clueless without in-depth analysis and sometimes used Pidgin English in maintaining their standard as a family-oriented newspaper. Furthermore, as mentioned earlier, The Guardian newspaper is widely known for quality journalism, unlike the Vanguard newspaper, which is considered light news. Therefore, it can be stated that the ideological position of the dailies influenced both newspapers' approach and reportage.

Also, the patterns of language use in these dailies is significant regarding the reportage of the abducted schoolgirls, as they are prone to convey intense emotions. According to Chari (2013), in framing, words, phrases, and headlines are important in communicating reality, and from the findings above, both dailies used phrases and language to construct a reality. In citing Ellsworth and Scherer (2003, p. 57) argue that “certain ways of interpreting one's environment are inherently emotional, [because] few thoughts are entirely free of feelings, and emotions influence thinking.” This is because every emotional language/phrase, such as “clueless,” “liar,” “hopeless,” “unfair,” and “slow reaction,” amongst others used by both presses, might tend to exaggerate reality and misrepresent facts. In the words of Chiluwa and Ifukor (2015, p. 269–270) “while emotional reactions and attitudes in discourse may reflect genuine general response to social realities, they are also in danger of negatively evaluating people and situations unjustly; discourses produced in a situation of global terror, especially reacting to some perceived “war” of violence on children or a global campaign on security and children's rights to education in Africa such as #BringBackOurGirls, are most likely to ideologically (mis)represent facts, governments or institutions.” Therefore, such a kind of reporting that is embedded with emotional ideologies may achieve practically nothing, leaving the main problems of insecurity unresolved.

Conclusion

This study was undertaken to assess the representation of Nigeria's political leaders during the #BringBackOurGirls movement campaign in two selected dailies—The Guardian and the Vanguard that arguably typify the press in Nigeria. This study discovered that the political leaders, President Jonathan and President Buhari, were framed quite differently in the two newspapers via the language and words used. For example, words such as “clueless,” “hero,” “victims,” and “hooligans” was used to frame the government of President Jonathan and President Buhari handling of the kidnapped schoolgirls. Nevertheless, both dailies' frames were similar despite the significant ideological difference between both dailies. Therefore, there is the need to interrogate the extent to which ideological orientation of the media influences media content and framing, or if economic interests play a significant role in shaping media content and framing than ideological position in a contested and fragmented media space like Nigeria. As Wasserman (2010) and Voltmer (2008) argue, the media in developing countries suffer from a weak economic base and capital. Thus the media has to be innovative by reflecting the voices of the people (Baum and Potter, 2008). For instance, Okonjo-Iwela (2018) argues that frames from the media during the abduction was not positive and reflective of the government actions but based on the general public perception of the government of President Goodluck Jonathan that he was ineffective and such frame as continued till date as he is still widely criticized for the handling of the kidnapped schoolgirls. Likewise, six years into President Buhari's rule, people are beginning to question the ascribed “heroism” frame attributed to him as not only has the schoolgirls have not been released, and there has been an increase in organized crime such as abduction, kidnapping and killing across the country (Abiodun, 2020). This buttress the assertion that the media framing was not based on reality but on public perception and opinion.

Alternatively, the media had to be sensational in their reportage (Wasserman, 2010). The events of the #BringBackOurGirls present an ideal opportunity for the media to be sensational via their word choice, headline and content to attract readership (see Chari, 2013). While ideological belief is central to very media organization and their practices, the similarity of frames in this study calls for a broader examination of the intersection between ideology and economic model in fragmented media space like Nigeria. To what extent are ideologies a reflection of the business model? While some scholars like Omu (1996) might argue that the press in Nigeria has historically been commercially driven, and this has invariably shaped their ideological position. There is the need for further studies to examine if such intersection exists and the forms in which it exists and affects the media production process, i.e., their sociological framing focus -languages, phrases, and presentation style (Druckman, 2001).

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author Contributions

UA conceptualized the idea, collected and analyzed the data, and finalized the manuscript. KA assisted with writing the literature review and the first draft. Both authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This research was funded by the African Humanities Program (AHP), awarded by the American Council of Learned Societies.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abdullahi, M., and Abdul, Q. (2019). Social media in an emergency: use of social media in rescuing abducted school girls in Nigeria. Dhaulagiri J. Sociol. Anthropol. 13, 67–75. doi: 10.3126/dsaj.v13i0.22188

Abiodun, A. (2020). Is Nigeria Still Winning the War on Insecurity? Daily Trust. Available online at: https://dailytrust.com/is-nigeria-still-winning-the-war-on-insecurity (accessed February 20, 2021).

Adaugo, I., and Roper, C. (2021). “Nigeria,” in Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2021 10th edition, eds Newman, R., Fletcher, A., Schulz, S., Andi, C., Robertson, N., and R. Nielsen. (Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism: Oxford).

Adesoji, A., and Hahn, H. (2011). When (Not) to be a proprietor: Nigerian newspapers ownership in a changing polity. Afric. Study Monograph. 32, 177–203. doi: 10.14989/151326

Akpojivi, U. (2018). Media Reforms and Democratization in Emerging Democracies of Sub-Saharan Africa. Palgrave: New York.

Akpojivi, U. (2018). I won't be silent anymore: hashtag activism in Nigeria. Communicatio 45, 19–43. doi: 10.1080/02500167.2019.1700292

Anderson, C. W. (2011). Between creative and quantified audiences. Journalism 12, 550–566. doi: 10.1177/1464884911402451

Baum, M., and Potter, P. (2008). The relationships between mass media, public opinion, and foreign policy: toward a theoretical synthesis. Ann. Rev. Politic. Sci. 11, 39–65. doi: 10.1146/annurev.polisci.11.060406.214132

BBC HardTalk. (2014). Interview with Dr. Obiageli Ezekwesili. Available online at: http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/n3csw9gz (accessed July 25, 2014).

Beeman, W. O., and Peterson, M. A. (2001). Situations and interpretations: explorations in interpretative practice. Anthropol. Q. 74,159–162. doi: 10.1353/anq.2001.0033

Berents, H. (2016). Hashtagging girlhood: #IAmMalala, #bringbackourgirls, and gendering representations of global politics. Int. Femin. J. Politic. 18, 513. doi: 10.1080/14616742.2016.1207463

Bourne, R. (2018). Far from healthy? the state of Nigerian media. Round Table 107, 163–172. doi: 10.1080/00358533.2018.1448338

Chari, T. (2013). “Media Framing of Land Reform in Zimbabwe,” in Land and Agrarian Reform in Zimbabwe: Beyond White-Settle Capitalism. eds S. Moyo and W. Chambati (Dakar: CODESRIA), pp. 291–330

Chiluwa, I., and Ifukor, P. (2015). War against our children: stance and evaluation in #bringbackourgirls campaign discourse on twitter and Facebook. Discour. Soc. 26, 267–296. doi: 10.1177/0957926514564735

CNN (2015). #BringBackOurGirls, One Year on: ‘We Should All Fell Shame'. Available Online at: https://edition.cnn.com/2015/04/14/opinions/sesay-bring-back-our-girls-one-year-on/index.html (accessed April 20, 2021).

Conboy, M., and Eldridge, S. A. (2014). Morbid symptoms. J. Stud. 15, 566–575. doi: 10.1080/1461670X.2014.894375

Currah, A. (2009). What's happening to our news: An Investigation into the Likely Impact of the Digital Revolution on the Economics of News Publishing in the UK. Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism (RISJ). Available online at: https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/our-research/whats-happening-our-news (accessed January 21, 2009).

Della-porta, D., and Tarrow, S., (eds.). (2005). “Transnational processes and social activism: an introduction,” in Transnational Protest and Global Activism. (Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield).

Druckman, J. (2001). The implications of framing effects for citizen competence. Politic. Behav. 23, 225–256. doi: 10.1023/A:1015006907312

Ellsworth, P. C., and Scherer, K. R. (2003). “Appraisal processes in emotion,” in Handbook of Affective Sciences. eds R. Davidson, H. Goldsmith, and K. Scherer. (New York, NY: Oxford University Press).

Entman, R. M. (1993). Framing: towards clarification of a fractured paradigm. J. Commun. 43, 51–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.1993.tb01304.x

Fosu, M., and Akpojivi, U. (2015). Media convergence practices and production in ghana and nigeria: implications for democracy and research in Africa. J. Appl. J. Media Stud. 4 227–292. doi: 10.1386/ajms.4.2.277_1

Fursich, E. (2010). Media and the representations of Others. Int. Soc. Sci. J. 61, 113–130. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2451.2010.01751.x

Guardian Newspaper (2018). http://media.guardian.ng (accessed June 1, 2018).

Guardian Newspaper (2019). https://media.guardian.ng/

Hanitzsch, T., and Hoxha, A. (2014). News Production: Theory and Conceptual Framework. Generic and conflict influences on the news production process. INFOCORE WP1 Working Paper.

Hermida, A., Domingo, D., Heinonem, A., Paulussen, S., Quandt, T., Reich, Z., et al. (2011). The active recipient: participatory journalism through the lens of the Dewey-Lippmann debate. #ISOJ 1, 129–152.

Khoja-Moolji, S. (2015). Becoming an ‘intimate public': exploring the affective intensities of hashtag feminism. Femin. Media Stud. 15, 347–350. doi: 10.1080/14680777.2015.1008747

Kperogi, F. (2012). “The evolution and challenges of online journalism in Nigeria,” in The hand- book of global online journalism, eds S. Eugenia and A. Veglis (West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell).

Kuypers, J. (2009). “Framing Analysis,” in Rhetorical Criticism Perspectives in Action. ed Kuypers, J. (Lanham: Lexington Books).

Lee, E. U., and Tandoc, E. C. (2017). Feedback online affects news production and consumption. Hum. Commun. Res. 43, 436–449. doi: 10.1111/hcre.12123

Loken, M. (2014). #bringbackourgirls and the Invisibility of Imperialism. Feminist Media Stud. 14, 1100–101. doi: 10.1080/14680777.2014.975442

Mortensen, M. (2018). The self-censorship dilemma. J. Stud. 19, 1957–1968. doi: 10.1080/1461670X.2018.1492880

Okonjo-Iwela, N. (2018). Fighting Corruption is Dangerous: The Story Behind the Headlines. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Olaniyan, A. (2014). Social Media And Political Activism In Nigeria: A Marriage Made In Heaven Or Just One-Night Stand? M.A. Dissertation. University of Westminster, London.

Omu, F. (1996). “Journalism In Nigeria: a historical perspective,” in Journalism In Nigeria: Issues and Perspectives Lagos: Nigerian Union of Journalists, eds O, Dare and A, Uyo (Lagos: Lagos State Council), p. 1–17.

Onyenankeya, T., and Salawu, D. (2020). On bended knees: investigative journalism and changing media culture in Nigeria. Media Watch 11, 97–118 doi: 10.15655/mw/2020/v11i1/49758

Ornebring, H. (2010). Technology and journalism-as-labour: historical perspectives. Journalism 11, 57–74. doi: 10.1177/1464884909350644

Paulussen, S., Harder, R., and Johnson, M. (2017). “Facebook and news journalism,” in The Routledge Companion to Digital Journalism Studies, eds B. Franklin and S. Eldridge (Abingdon: Routledge).

Peterson, M. A. (2003). Anthropology and Mass Communication: Media and Myth in the new Millennium. New York, NY: Berghahn Books.

Reese, S. D., and Lewis, S. C. (2009). Framing the way on terror: the internationalization of policy in the U.S press. J. Theory, Pract. Critic. 10, 777–797. doi: 10.1177/1464884909344480

Santos, J. (2015). “Social construction theory,” in The International Encyclopaedia of Human Sexuality, eds A. Bolin and P. Whelehan (London: Wiley-Blackwell)

Singer, J. B., Hermida, A., Domingo, A., Heinonen, A., Paulussen, S., Quandt, T., et al. (2011). Participatory Journalism: Guarding Open Gates as Online Newspapers. New York, NY: Wiley-Blackwell.

Sundar, S. S. (1998). Effect of source attribution on perception of online news stories. J. Mass Commun. Q. 75, 55–68. doi: 10.1177/107769909807500108

Thurnma, N. (2011). Making The Daily Me: Technology, economics and habit in the mainstream assimilation of personalized news. Journalism 12, 395–415. doi: 10.1177/1464884910388228

Van Hout, T., and Jacobs, G. (2008). News production theory and practice: fieldwork notes on power, interaction and agency. Pragmatics. 18, 59–85. doi: 10.1075/prag.18.1.04hou

Vanguard Newspaper (2014b). #BringBackOurGirls: We don't know location of abducted girls – GEJ. Available online at: https://www.vanguardngr.com/2014/05/bringbackourgirls-dont-know-location-abducted-girls-gej/ (accessed November 18, 2018).

Vanguard Newspaper (2014c). Chibok Girls: Mbu bans #BrickBackOurGirls protests in Abuja. Available online at: https://www.vanguardngr.com/2014/06/chibok-girls-mbu-bans-bringbackourgirls-protests-abuja/ (accessed February 06, 2019).

Vanguard Newspaper (2014d). Is #BringBackOurGirls being politicized? Available online at: https://www.vanguardngr.com/2014/06/bringbackourgirls-politicised-2/ (accessed November 28, 2018).

Vanguard Newspaper (2017). Available online at: http://www.vanguardngr.com/about/ (accessed July 01, 2017).

Voltmer, K. (2008). Comparing media systems in new democracies: east meets south meets west. Central Euro. J. Commun. 1, 23–40.

Keywords: framing (representation), mass media, ideology, #BringBackOurGirls (#BBOG) movement, Nigeria, chibok girls, guardian newspaper, vanguard newspaper

Citation: Akpojivi U and Aiseng K (2022) Framing of Political Leaders During the #BringBackOurGirls Campaign by the Nigerian Press: A Comparative Study of Guardian and Vanguard Newspapers. Front. Commun. 7:853673. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2022.853673

Received: 12 January 2022; Accepted: 17 February 2022;

Published: 05 April 2022.

Edited by:

Pradeep Nair, Central University of Himachal Pradesh, IndiaReviewed by:

Samantha A. Majic, John Jay College of Criminal Justice, United StatesIsyaku Hassan, Sultan Zainal Abidin University, Malaysia

Copyright © 2022 Akpojivi and Aiseng. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ufuoma Akpojivi, ZnVvdGVnQHlhaG9vLmNvbQ==

Ufuoma Akpojivi

Ufuoma Akpojivi Kealeboga Aiseng2

Kealeboga Aiseng2