- 1Department of Foreign Languages, Faculty of Arts and Humanities, University of the Western Cape, Cape Town, South Africa

- 2Department of Linguistics, Faculty of Arts and Humanities, University of the Western Cape, Cape Town, South Africa

- 3English for Educational Development (EED), Faculty of Arts and Humanities, University of the Western Cape, Cape Town, South Africa

The present study attempts a political discourse analysis of a spoken Arabic corpus on the death of Nelson Mandela. The corpus mainly consists of the coverage of some Arabic-speaking TV channels that was broadcasted in the aftermath of the announcement of Nelson Mandela's death in 2013. The discourse-historical approach was employed with a view to finding out the various topoi and ideologies deployed in the corpus. For this purpose, the spoken corpus used in this study was first transcribed using EUDICO Linguistic Annotator (ELAN), a transcription tool for multimodal texts. Afterward, the corpus was compiled using Sketch Engine to enable researchers to process the data automatically and hence to use different computational tools that can assist in finding the various topoi. A computational analysis using collocations, wordlists, N-grams, and concordance features can provide a more precise analysis of the various topoi in context and hence to uncover the ideologies of participants/politicians. The findings of the study showed that the corpus abounds in topoi that are not necessarily related to Mandela or his death, but they are rather related to heated political issues in various countries of the Middle East. Politicians have shifted their focus from the main topic which is the death of Nelson Mandela to conflicts and political plights in countries such as Egypt, Syria, Iran, Iraq, Yemen, and Palestine. Politicians have used the media coverage as a platform to express their feelings and to compare Mandela with the Arab leaders in their respective countries. The coverage has sometimes transcended speaking about Mandela to the deployment and projection of certain ideologies of the interviewees. Those ideologies are not only confined to one participant's country, but they are representative of the Arab identity and concerns at large.

Introduction

Nelson Mandela has been hailed as one of the most influential leaders of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. It is not surprising that he is highly respected in many Arab countries, many of which have witnessed some degree of instability and political turmoil. His death in 2013 attracted attention across Arabic media. Al Jazeera, Al Arabia, Sky news, BBC Arabic, CNN Arabic as well as local TV channels in Arab countries devoted considerable coverage to narrating his legacy and broadcasting his funeral. In a similar vein, social media platforms such as Facebook and Twitter mourned Mandela's passing, commemorating him and his legacy for weeks after his death. He is still remembered years after his departure. Biographies and other books about Mandela have been translated into Arabic; some have multiple translations. UNESCO translated several of Mandela's important speeches into Arabic as a part of a widely circulated project named “A Book in a Newspaper.” These translations were published in almost all Arab countries (Mohammed and Banda, 2016).

When the Arab Spring began in 2011, political figures like Javari and Gandhi inspired Arabs to mobilize in the Freedom Squares of their countries and as protests gained momentum, their names echoed in the chants of activists. The status of these figures nevertheless pales in comparison to Mandela. Arab protesters in their activism often referred to a letter they claim was written by him at the height of the Arab spring in 2011. It is a message of advice and wisdom; calling for tolerance, forgiveness, and reconciliation. Hence, while Arab protesters raised pictures of Javari, Gandhi, and other leaders during the Arab Spring, Mandela's image was visible in many Freedom Squares, and his words to the Arab masses circulated widely across social media and in Arab press.

Statement of the Problem

The news of Mandela's death was woefully received by politicians and common people across the Arab world. Interviews with politicians in official media and on social networks demonstrate the level of respect for Mandela, his struggle, and personal history. BBC Arabic, for example, devoted its well-known programme nuqṫat ḍau to documenting the reaction of Arab people to Mandela's death. People from various Arab countries such as Sudan, Tunisia, Morocco, Yemen, Saudi Arabia, Iraq as well as Arabs living in countries like Sweden and the UK responded to the central question of the programme; “What does Mandela mean to you?” This programme and other similar ones aired by Arabic media channels were mainly devoted to the death of Nelson Mandela. However, they also intended to document the attitudes of Arabs toward Mandela, including their reaction to his death. Participants also took the opportunity to express their opinions about various issues in the Middle East. In other words, the focus shifts from commemorating the legacy of Mandela to expressing intrinsic and extrinsic topoi, including conversations about identity, ideologies, and the representation of the Self and the Other. This may have been because Mandela's death came at a time when several Arab countries were experiencing leadership crises and consequent uprisings, with some experiencing harrowing and terrifying civil wars, extremism, violence, and terrorism. Speeches of mobilization in the name of religion, partisanship, and revolution plunged the Arab world into despair, frustration, crisis, and disintegration. Amidst the crises of leadership, Mandela's extraordinary legacy commitment to ending apartheid and bringing peace and reconciliation to South Africa inspired Arabs who were struggling for nations free of injustice, corruption, violence, and discrimination. The death of Mandela has fueled debate in Arab media and lead to a greater diversity of topoi which are often not directly related to his death or even his legacy. It is not an exaggeration to suppose that the death of Mandela received more attention from Arab media than his release from prison in 1990 or his being elected president in 1994. Although Mandela's background, struggle, release from prison, and presidency have always been topics of interests in Arabic media, the discourse on Mandela was typically confined to certain politicians who aligned with the ideology of the channels, and who were carefully chosen by them.

The corpus used in this study does not only represent these views from mainstream media, but also the views of active content creators on digital media platforms. The diverse nature of the corpus can be attributed to the fact that it represents the perspectives of people with a variety of religious and political beliefs, education levels, gender identities, ethnic origins, and geographical backgrounds. Religious and secular, moderate and radical, African-Arabs and Asian-Arabs, men and women, academics and laypeople, all have an equal opportunity to commemorate the death of Mandela, and are likely to be represented somewhere in a corpus. Rapid advances in social media technology have enabled previously inactive mass media consumers to create their own content about Mandela and his legacy. This has led to greater diversity in intrinsic and extrinsic topoi that transcend those introduced by politicians hosted by Arab mainstream media.

Objective and Questions of the Study

The present study is a political discourse analysis of an Arabic corpus comprised of media coverage about the death of Nelson Mandela. It sets out to explore how Arabs reacted to his death by evaluating the language they used to express their attitudes and the topoi and ideologies they explicitly or implicitly embraced. Hence, this study addresses the following questions:

(1) What explicit topoi regarding Mandela, South Africa, and the Arab world feature in the corpus?

(2) What implicit topoi regarding Mandela and Arabs feature in the corpus?

(3) How do Arab politicians identify themselves through their speeches/contributions?

Literature Review

Many theories of critical discourse analysis (CDA) have been used in the analysis of political discourse. This section deals with three of these approaches, namely Norman Fairclough's “discourse as a social practice” (Fairclough, 2001), Teun van Dijk's “social cognition approach” (Van Dijk, 2001), and Theo van Leeuwen's “social actor network” (Van Leeuwen, 2008).

Fairclough's “discourse as a social practice” (Fairclough, 2001) has been used to analyze the political discourse on Islamic Khilafah during the rise of the so-called Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS) in 2014 (Hidayatullah, 2017). The ideological representation of the concept in two well-known Arab media channels, namely Al Jazeera and Al Arabiya was investigated. The approach was also employed in the analysis of the image of Arab immigrants in American and British media, as well as the image of Arabs in American press (Shousha, 2010; Hattab and Fakhir, 2020). In addition, Al Jazeera debates on the Yemeni uprising of 2011 (Al Kharusi, 2017) and articles posted on their English website to mark the third anniversary of the uprising in 2000 of Palestinians against Israeli authorities, known as the al-Aqsa Intifada (Wenden, 2005) were also analyzed using Fairclough's approach. The approach was also employed to explore the identity of Arab women in three Arab newspapers, namely, Midan Al Jazeera, Al-Ittihad, and Mawdoo3 which discussed problems in the social lives of Arab women (Hamid et al., 2021).

Van Dijk's “social cognition approach” found its way into several studies on Arab political issues. It has been used to investigate the ideologization of Arab media discourse with specific reference to the construction of the Gulf crisis in the headlines of Al Arabiya English and Al Jazeera English (Kharbach, 2020). The approach was also used to investigate how politicians participating in the May 2017 Arab-Islamic-American Summit in Riyadh presented themselves and others, and the techniques they employed to send ideological messages to their opponents and allies (Youssef and Albarakati, 2019). This approach was also used to unravel identity reproduction in the national anthems of some Arab countries (Arab Yousofabady, 2019) and to investigate the conceptualization of the term “extremism” and its Arabic equivalent taṭaruf on Twitter (Hamdi, 2022).

Another key framework of CDA is Van Leeuwen's “social actor network” (Van Leeuwen, 2008). This approach has been employed to investigate the representation of Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) in American newspapers such as the (New York Times) (Abdulkareem and Qassim, 2017) as well as in the analysis of the representation of Iran in the Arabic-language newspaper Al-Sharq Al-Awsat (Ghasemi Asl and Niazi, 2020). This newspaper was deliberately chosen because it is associated with Saudi Arabia, where media discourse is often diametrically opposed to other Arab worldviews. This highlights the numerous ways in which ideology is used in the press.

Topoi in political discourse have been investigated in many studies. Topoi used in describing others, such as migrants, were analyzed by J. E. Richardson, who listed topics including humanitarianism, justice, responsibility, finances, reality, numbers, law and rights, history, culture, and abuse, among others (Richardson, 2004, p. 4). Krzyzanowski (2009, p. 103) identified national vs. European topoi in two corpora. Common topoi in national corpus include uniqueness, history, East and West, past and future, modernization, the EU as a national necessity, the EU as a national test, and etcetera. The European corpus, on the other hand, included topoi such as diversity in Europe, European history and heritage, European values, European unity, Europe of various speeds, European and national identity, Europe as a future orientation, modernization, joining the EU at any cost, and preferential treatment. Similarly, the Arabic slogans of the Arab Spring included topoi related to political humor and satire, political evaluation, political threats, Arab nationalism, resentment of current policies, accountability, and standards of living (Al-Sowaidi et al., 2017, p. 627–629). Frequent topoi mentioned by Iranian Presidents Hassan Rouhani and Mahmoud Ahmadinejad at the United Nations (UN) General Assembly were also investigated in a recent study of two speeches (Alemi et al., 2018). According to the researchers Rouhani follows a moderate political ideology, while Ahmadinejad, is more conservative. Among the topoi found in the speech of the former are world fears of war, militarism, violence, globalization of western values, political superiority, and Iranian elections. Topoi such as egoism, distrust, dictatorship, periods of slavery, crusade wars, and the occupation of Palestine dominate the speech of the latter (Alemi et al., 2018, p. 7–8).

This study draws on critical discourse analysis (CDA) to unravel the underlying political ideologies of participants in a spoken corpus associated with Mandela's death. For the purpose of this study, Wodak's discourse-historical approach (DHA) (Wodak, 2001) is used to examine the manipulative nature of political discourse as well as the identity reflected in the corpus under investigation. At the time this study was conducted, there were no known studies that employed this approach in the analysis of Arabic political discourse. However, it has been widely used independently and eclectically in CDA (Johnson et al., 2010; Momani et al., 2010; Buckingham, 2013). The fact remains that political discourses are laden with certain ideologies, concerns, and representations. In other words, each political discourse has its own unique features, or “content-related argument schemes,” which “can be carried out against the background of the list of topoi though incomplete and not always disjunctive” (Wodak, 2001, p. 74). This study mainly focuses on the topoi of Mandela's death as viewed by Arab politicians. Further analysis of linguistic features such as rhetorical topoi, transitivity, and appraisal, is beyond the scope of this study.

Theoretical Framework

As mentioned earlier, this study is a political discourse analysis of a spoken corpus. It draws mainly on the discourse-historical approach (DHA) (Wodak et al., 1990; Wodak, 1994, 2001). What makes the DHA of CDA relevant to this study is that it not only deals with the linguistic aspects of a text/discourse, but it attempts a multifaceted social critique aimed at integrating “a large quantity of available knowledge about the historical sources, the background of the social and political fields in which discourse is embedded, and the context where analyzed discourses take place” (Wodak, 2001, p. 65). The context of discourse in this approach is examined through an analysis of the linguistic context or co-text; the intertextual and interdiscursive relationship between utterances, texts, genres and discourses; the extralinguistic variables and institutional frames of a specific “context of situation” and the broader socio-political and historical context (Wodak, 2001, p. 67).

DHA is mainly concerned with critiques including (Wodak, 2001, p. 65): (1) Text or discourse immanent critique, which aims to discover internal or discourse related structures; (2) socio-diagnostic critique, which attempts to reveal the persuasive or potentially manipulative nature of certain discursive practices; and (3) prognostic critique, main goal of which is to contribute to the improvement of communication. This study aligns with Wodak's view (Wodak, 2001) that it is not a goal of CDA to determine accuracy. Instead, researchers should continuously evaluate each stage of the research process and justify their choices. A CDA approach may also explain why some interpretations of discursive occurrences appear to be more valid than others. Hence, the notion of triangulation is one of the methodological techniques that can be adopted by critical discourse analysts to minimize bias. Ultimately, DHA is more flexible as it allows the use of multi-methodical approaches which can incorporate various empirical data and background information.

A concept within DHA that is relevant to the present analysis is that of topos (plural: topoi). Introduced by Aristotle and used by later rhetorical theoreticians including Cicero, the concept was used in classical argumentation theories (Žagar, 2010). Through topoi, speakers clarify their positions on a variety of concerns. For instance, politicians can illustrate and describe the types of relations they hope to establish with international powers and agencies (Alemi et al., 2018, p. 6). For Wodak, topoi or loci are the premises, either explicit or implicit, of argument. Topoi are connected through “the content- related warrants or conclusion rules which connect the argument or arguments with the conclusion, the claim” (Wodak, 2001, p. 74). Wodak used the term topoi in a narrow and adapted sense and for triangulation purposes. In line with this usage, a critical discourse analyst needs to employ argumentation theory or, more specifically, the theory of topoi with a view to realizing the principle of triangulation. Topoi can be intrinsic (i.e., part of the discourse) or extrinsic aspects that arise during an argument. Several topoi are likely to be evoked by certain lexicons or lexical groups (Bruxelles et al., 1995). Intrinsic topoi can therefore pave the way to more extrinsic ones that were not planned as part of a discourse, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Intrinsic vs. extrinsic topoi (Bruxelles et al., 1995).

Topoi can be dynamic, and might be incorporated in a speech or a text through “a single word or a group of lexical phrases with several other topoi which together form a topical field” (Alemi et al., 2018, p. 4). In line with this view, and the method of triangulation recommended by Wodak, it can be argued that the use of corpora tools can assist in encapsulating various topoi in a political speech more efficiently than a manual analysis and codification would, especially when unpacking and processing a bulk of data, as is the case in this study.

Methodology

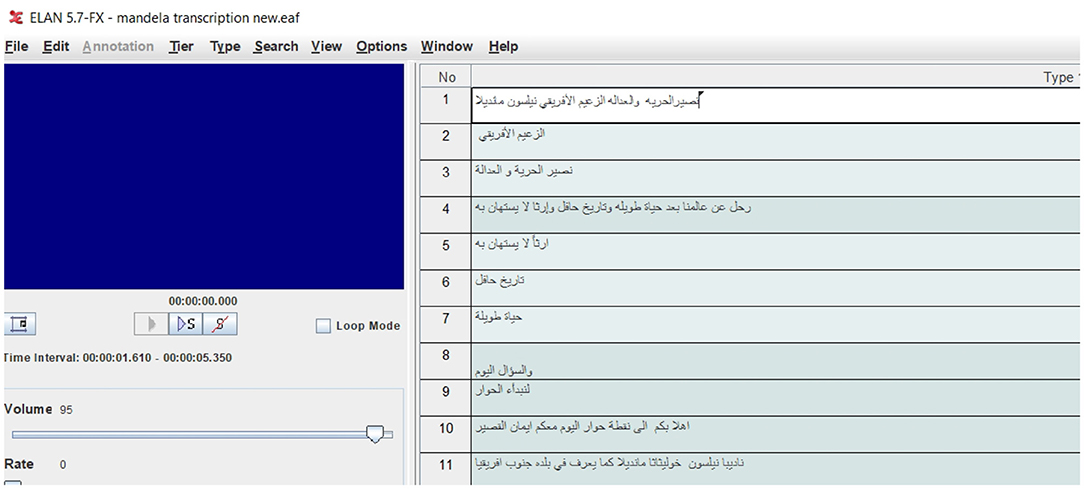

This is a corpus-based study of a selection of Arabic TV programmes broadcasted after the announcement of Mandela's death in 2013. The corpus in this study includes 6,636 words, and was checked against the video and audio versions of the speeches to determine whether they were exact transcriptions. For the transcription of data, a multimedia annotation tool called EUDICO Linguistic Annotator (ELAN) was used. This is a tier-based tool for multimodal data in which annotations can be created in multiple layers, or tiers and thus is beneficial to both qualitative and quantitative multimodal research. The annotation can be a word, a sentence, a translation, a note, or a comment. The transcription for this study was created using ELAN and aligned to the time in the videos and audios, as shown in Figure 2.

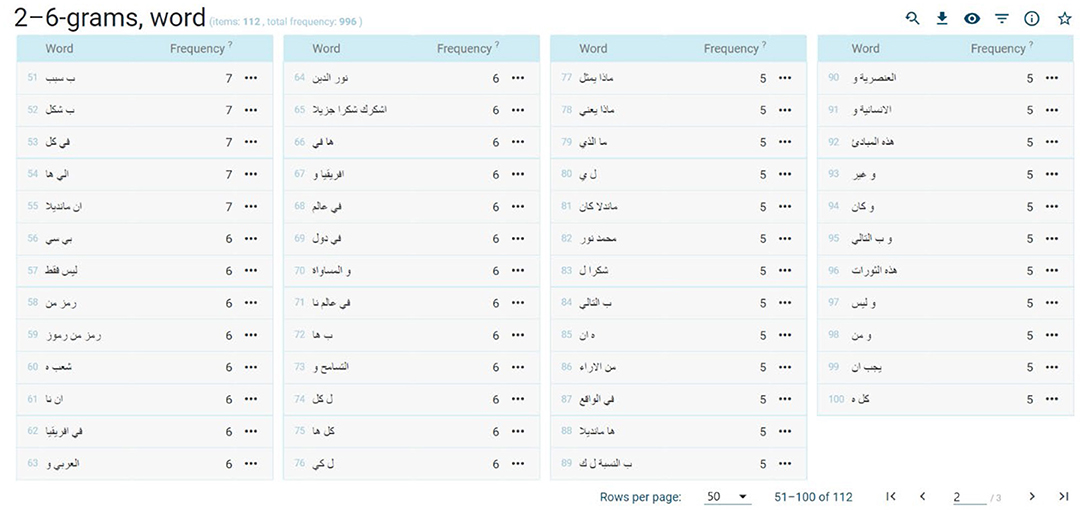

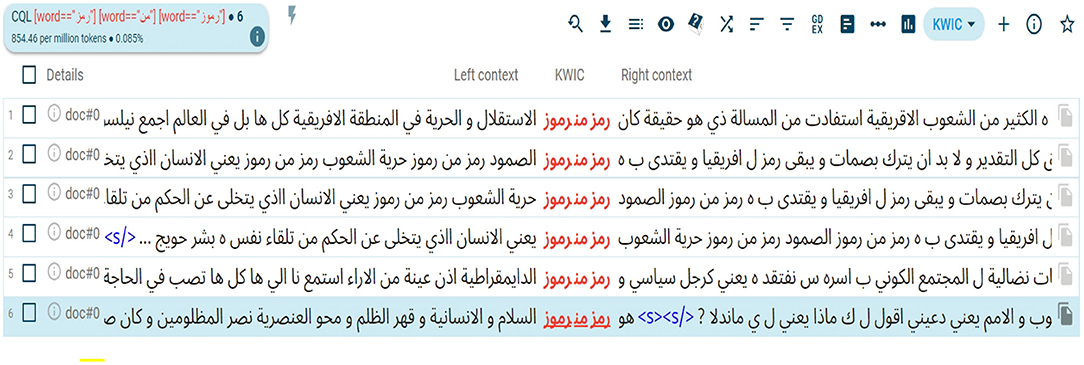

After completion of the transcription in ELAN, the output was processed using a cloud-based corpus tool known as Sketch Engine. This tool can provide a list of useful computational linguistic methods that help locate topoi deployed in a corpus. Collocations, wordlists, concordances, and N-grams are some of these methods. Figure 3 is a snapshot of the wordlist from the corpus used in this study.

Although a wordlist can provide an idea of the topoi in a corpus, it may be more useful to use an N-grams tool to determine not only the most frequently occurring words, but also the most frequently used expressions, as shown in Figure 4.

The corpus also locates key words and expressions in context through the concordance tool, which gives a precise understanding of the co-text, as well as the context of a word or expression. Hence, keywords, N-grams, and concordances can be used to extract intrinsic topoi employed in the corpus under investigation. A concordance, for instance, can provide key words in context (KWIC) allowing researchers to locate certain lexicons in different contexts of a speech, or a text, and thereby provides a more comprehensive picture of the progression of discussion. This can help to identify and extract extrinsic topoi that may have been implicitly argued by the speaker(s).

Discussion

Based on the various corpora analysis tools, the most frequent topoi related to Mandela's death that appear in the corpus are: leadership qualities of Mandela, leadership crisis in the Middle East, the Palestinian cause, the Arab Spring, Mandela's imprisonment, Mandela's death, Mandela's symbolism, racism, and tolerance, among others. These topoi are all intrinsic since all of them are associated with certain lexicons, as shown in the concordances and graphs below.

Leadership Qualities of Mandela

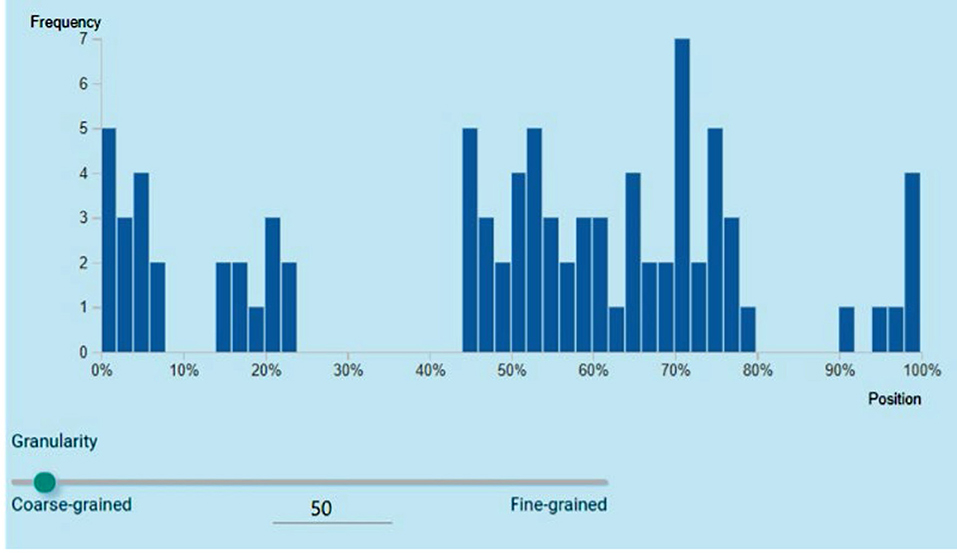

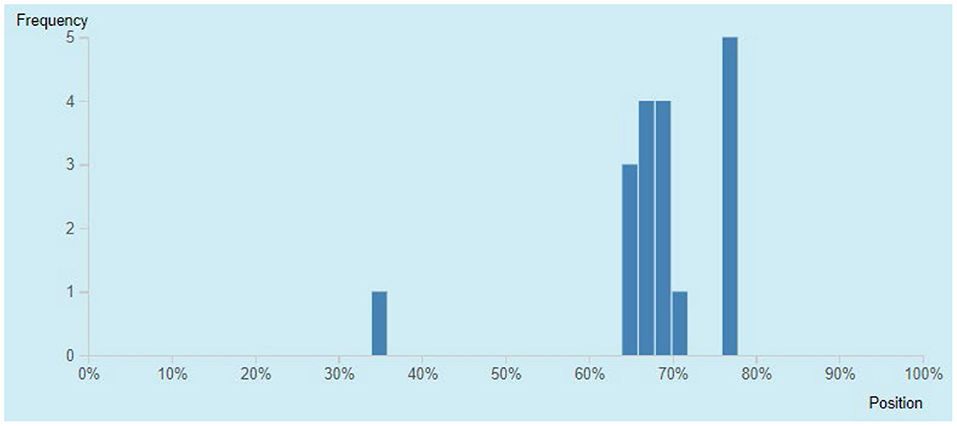

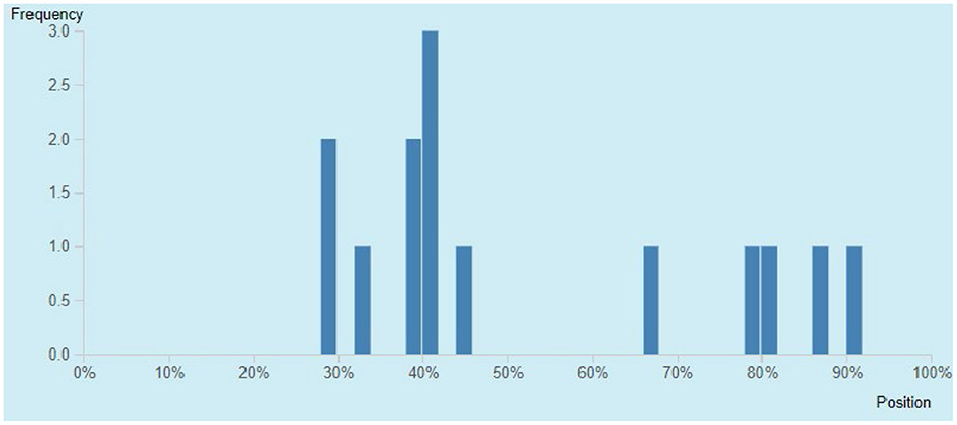

The leadership qualities of Mandela are repeated in various positions throughout the corpus, as Figure 5 shows.

Mandela has been described as a champion of freedom and justice. He was a man of tolerance and selflessness, who left power willingly. Moreover, he was an inspired leader who struggled on behalf of his nation. He is an icon of freedom and independence not only in Africa, but across the world. In addition to being a global symbol of equality, he is also commonly seen as a wise and ascetic individual who had no desire for power. Viewed as an unmatched global leader and as a symbol of humanity's struggle for peace, his legacy is now more urgent than ever amid the turmoil, conflicts, and wars that we see around us. A discernable image of Mandela was revealed in the corpus 124 times, through the combined use of terms including al-rajul (the man) 17 times, the use of the pronoun huwa (he) 54 times, and the use of al-rayis (the president) 3 times.

Leadership Crisis in the Arab World

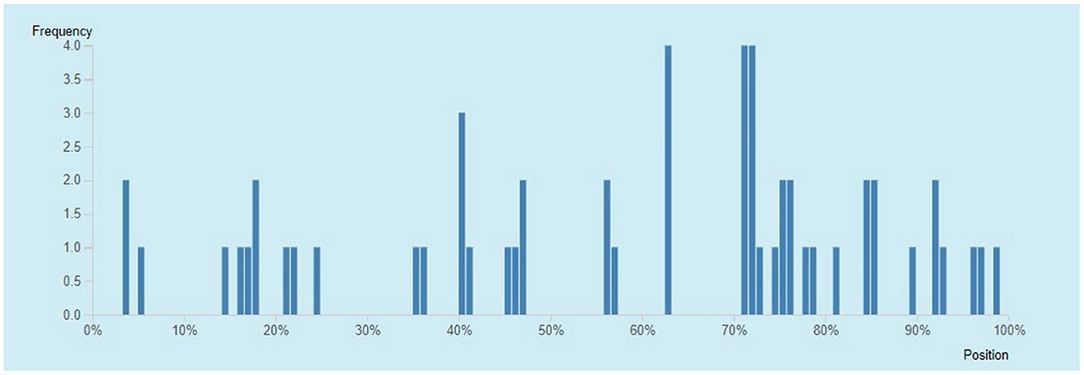

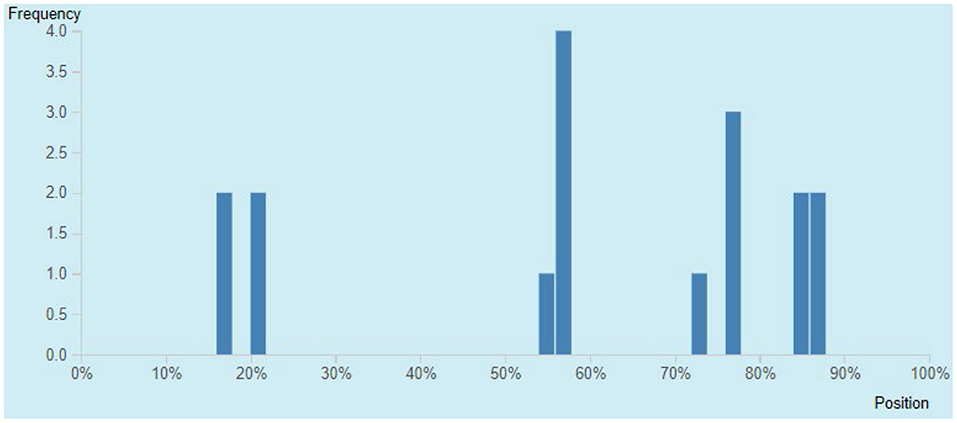

The word Arab and its lemmatized forms are repeated more than 56 times in the corpus, as Figure 6 shows.

Although the theme of the discussion revolves around the death of Nelson Mandela, the discussion noticeably shifts from this main topic to a discussion about political issues in the Arab world and its crises of leadership. The discourse indicates an urgent need for an “Arab Mandela.” Arabs have often drawn comparisons between Mandela and Arab leaders. Some argue that there are many Mandelas in the Arab world, but they lack grassroots support. Others believe that no Arab leader can ever compare to the legacy of Mandela's leadership. In contrast to many Arab leaders, Mandela voluntarily left power when many believed he was in his prime, whereas there are no known cases of Arab leaders having done this. Many would prefer that their children succeed them, if they had not been overthrown by force. While Mandela's public image indicated that he valued the South African nation above all else, some Arab leaders have made the mistake of allowing colonial powers to retain a foothold in their countries. It was sufficient for Mandela when he left office that tears were shed over his departure, but many Arab leaders leave only when blood is shed. Indeed several speakers in the corpus used for this study expressed reservations and skepticism about the possibility of an “Arab Mandela” ever existing.

The Palestinian Cause

Mandela's support for the Palestinian cause appeared in 18 contexts, especially toward the end of the corpus as Figure 7 shows.

Mandela advocated for the freedom of Palestine; he was a sincere friend of the Palestinian people and many South African people have continued this legacy. He adamantly opposed any attempts to marginalize this support. He is well-known for the view that freedom in South Africa would not be complete unless Palestinians' rights were also secured. Mandela, along with the African National Congress (ANC) have been staunch supporters of the Palestinian cause. Mandela planted the seeds of love and friendship for the Palestinian cause in the hearts of the ANC and of many South Africans, as evidenced by widespread, ongoing activism in South Africa in support of Palestinians. Apart from the ANC, there are many South Africa-based organizations that support the Palestinian cause such as the Palestinian Solidarity Forums at South African Universities, the BDS movement in South Africa and its famous members such as Desmond Tutu as well as the Muslim Judicial council. As a result, the Palestinian cause has not been diminished by the death of Mandela. A considerable number of Palestinian prisoners, some of whom have spent more than 25 years in prison, and organizations which advocate on their behalf, have been inspired by the long, revolutionary history, and struggle of Mandela. An organization which is known to have drawn inspiration from Mandela as part of their cause is the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO).

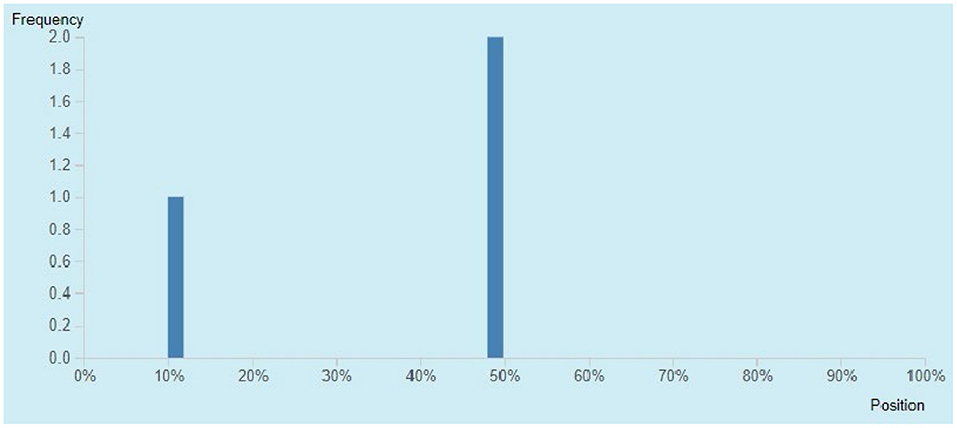

Arab Spring and Uprisings

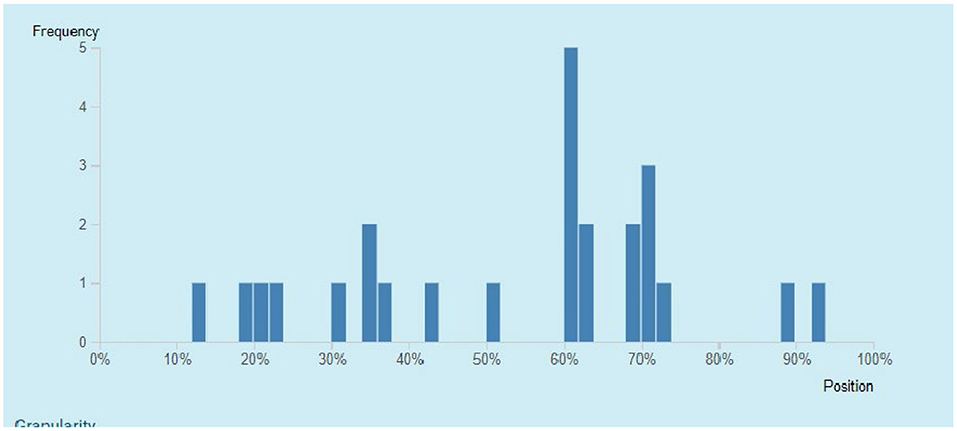

The topos of uprising has been repeated 17 times in various positions of the corpus, as shown in Figure 8.

Only two contexts refer to the uprising of Mandela against apartheid. All other contexts are concerned with the Arab uprisings in Egypt, Syria, Tunisia, Yemen, and the like. Mandela was able to bring about change in South Africa because he had a strong grassroots base, not unlike Ali Khamenei of Iran. Arab leaders, however, do not generally have the same base of support. Mandela's legacy was a source of inspiration (both directly and indirectly) during the Arab uprisings in general, but the uprising in Tunisia in particular. Arabs can benefit from Mandela's legacy to the extent that he demonstrated the possibility of achieving reconciliation and bringing an end to conflict; the same ideas could be applied in the aftermath of Arab uprisings. Sectarianism, tribalism, intolerance, and undermining others exacerbate tensions and result in additional complications and repercussions. As a safeguard for the success of these revolutions, Mandela's message, which appears numerous times throughout the corpus, calls for forgiveness, and tolerance. Mandela's advice proved to be practical and useful for Arab revolutionaries in the wake of the Arab Spring. In Yemen, for example, the then-president signed a transition agreement on 23 November 2011 under which he ceded power to his Vice-President Abdrabbuh Mansour Hadi, while the opposition established a national unity government. Based on this Gulf-brokered transition deal, the opposition and protesters agreed to grant Saleh and his regime immunity from prosecution.

Mandela's Death and Illness

The lemmatized forms of tuwifiya (to die) were repeated 16 times in the corpus, as shown in Figure 9.

The topoi of death and illness examined in the corpus include the reaction of South Africans to news of Mandela's death, the repercussions of his death on financial markets, the concerns of South Africans about violence and disorder in the aftermath of his death, and the reaction of people in countries such as Sweden, Malaysia, Palestinian territories, and many other Arab countries, to his death. The topos of death was also discernible in the corpus via the word raḥı̄l (departure) in various contexts. The word was repeated 9 times in the corpus to explain the repercussions of Mandela's passing for the Palestinian cause; his state memorial; and rituals of mourning, such as lowering of flags and observing moments of silence. The word raḥı̄l was also used in the corpus to describe people's shock upon receiving the news of Mandela's death in Johannesburg and Pretoria, even though his death was expected.

Mandela's Imprisonment

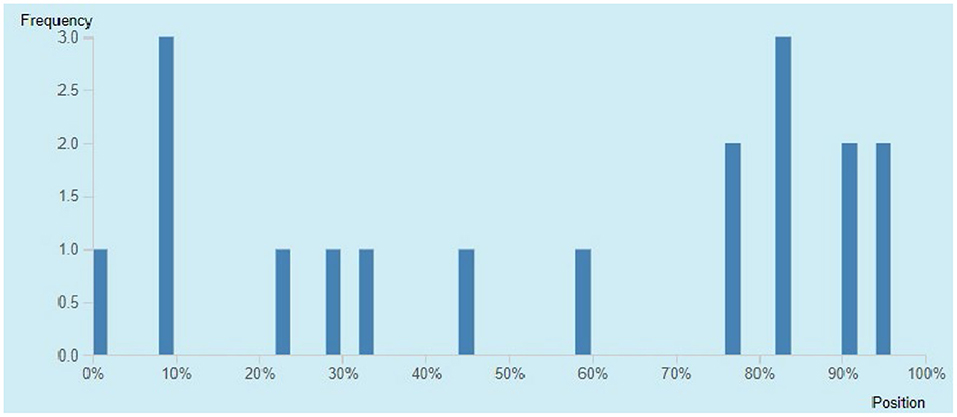

The sijn (imprisonment) of Nelson Mandela was expressed 18 times in the corpus, as Figure 10 shows.

The corpus not only refers to Mandela languishing in prison and his political activism, but also how his legacy has inspired Palestinian prisoners who have spent more than 25 years in Israeli prisons.

Mandela spent 27 years in prison on charges of treason, sabotage, and armed conspiracy. He mentioned many times how he struggled with the miserable conditions in prison. When he was released, he could have retaliated against his captors, but he refrained. Instead, he supported negotiations with the apartheid regime while still incarcerated. When he was released, he spoke to the entire world, advocating peace, forgiveness, and tolerance.

Apartheid/Racism

The main words that were used in the corpus to refer to racism and apartheid are 'unṣurī (racist), 'unṣurīyah (racism), and al-'unṣurī (the apartheid). They occurred 16 times, primarily in the context of Mandela's struggle against racism and the apartheid regime, and 3 times in the context of Arab world, as shown in Figure 11.

The corpus includes claims that racism is common in the Arab world; one politician even went to the extreme of describing Arabs as racist by nature.

Prayers for Mandela

Extremist ideologies are apparent in the corpus. It is represented by a few participants who claimed that Muslims should not pray for Mandela because he died as a disbeliever. A professor of Islamic Jurisprudence at an Arab University, who also appears in the corpus, provides some Prophetic hadiths that support this argument. Kuwaiti Islamic scholar Tariq Al-Soudan refutes this argument, stating that the Prophet Mohammed (Peace be Upon Him) held some disbelievers in high esteem due to their humanitarian outlooks. For example, the Prophet spoke highly of Al-Bukhtari bin Hisham, who was instrumental in ending boycotts against the Banu Hashim, the Prophet's immediate family tribe.

The word raḥmah (mercy) is repeated three times in the corpus, as shown in Figure 12, twice as part of prayers for Mandela, and once to claim that it is not Islamically permissible to pray for him.

Symbolism of Mandela

The symbolism of Mandela is reiterated repeatedly in the corpus, as shown in the concordance in Figure 13.

Throughout Africa and the world, Nelson Mandela serves as a beacon of hope for those striving for freedom and independence. He is a symbol of democracy, resistance, and survival. He is also a symbol of peace and humanity, as well as a conqueror of injustice, an anti-racist, and a supporter of the oppressed. He is also depicted as a symbol of fatherhood, a spiritual leader, and a godfather.

Reality

The topos of reality mainly appeared in the corpus to describe the impact of Mandela's death on the South African people, as illustrated in Figure 14.

Mandela's death came as a shock to South Africans and the world, although it was expected. The news was denied by many at first, but soon the streets and roads of South Africa were empty. Public mourning was declared: flags were flown at half-mast in honor of the deceased, and many public and private institutions were closed until further notice.

Tolerance and Reconciliation

The topoi of tolerance and reconciliation both appear in the corpus through the use of altaṣāluḥ (reconciliation) and altasāmuḥ (tolerance), as Figure 15 shows.

Anyone who was wrongfully imprisoned for 27 years and called for tolerance and reconciliation following their release must be an exemplary person. Mandela's reconciliation is sorely needed today in the Arab world, and in Egypt in particular. The legacy of his tolerance has been a driving force behind South Africa's economic prosperity. Tolerance and reconciliation are two virtues of Islam; Arab leaders should follow the example of Mandela and seek reconciliation with all political adversaries in their countries. Instead of retaliation and destruction, Mandela used tolerance and reconciliation as his weaponry.

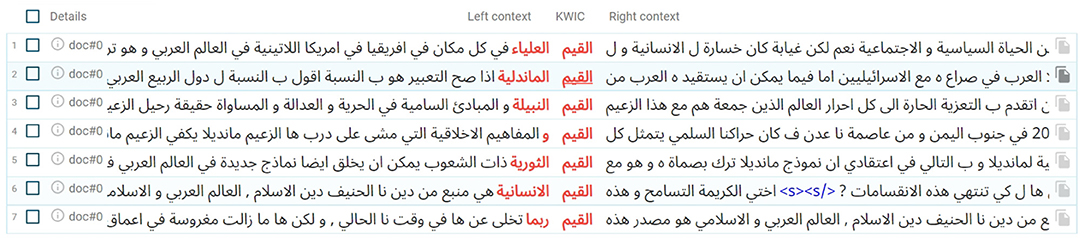

Legacy and Principles

References to Mandela's values and principles found their way into different contexts of the corpus, as shown in Figure 16.

The principles and legacy of Nelson Mandela should be remembered and celebrated occasionally. They should be encouraged and immortalized. At the very least, some of these principles should be implemented in the politics of Arab leaders. The activist prerogative of labeling Mandela as a leader without the application of his principles is not acceptable. Unfortunately, however; the corpus demonstrates that Mandela's principles are for now unenforceable in the Arab world. Mandela struck a delicate balance between ethics and politics. Many Arab leaders, on the other hand, remain unethical. Moreover, the Arabic word al-qiyam (values) is repeated several times in the corpus, as shown in Figure 17.

The various KWICs emphasize that many politicians believe the revolutionary, humane, ethical, and unmatched values of Mandela should be embraced.

Number

A concordance of the Arabic word fatrah (term), referring to Mandela's single presidential term, was repeated six times in the corpus, as Figure 18 shows.

Mandela served as the first black president for one term, refusing to run for a second despite calls from the South African people. In the Arab region where autocratic leaders commonly remain in office for life, the one-term presidency of Mandela is unique. Apart from Mandela's presidency, the topos of number has also been used in the corpus to refer to the imprisonment term of Mandela.

Furthermore, several extrinsic topoi were retrieved using the intrinsic topoi outlined above, and the various analytical lexical tools provided by Sketch Engine. Extrinsic topoi include “Khamenei's grassroots in Iran”; “lack of support for Arab leaders”; “need for national reconciliation in Egypt”; “peaceful struggle in South Yemen”; “Islamic values and principles”; “AIDS”; “fears and pessimism”; “anti-Zionism”; “Syrian conflict”; “tribalism and sectarianism”; and finally; “toxicity,” which, although not directly mentioned in the corpus through lexicons, still exists. The topos of toxicity, for instance, can be implicitly extracted from a myriad of contexts in the corpus. As mentioned, for instance, some Twitter users have tweeted their objection to praying for Nelson Mandela on the pretext that he died a disbeliever. As also noted, this has triggered responses from many scholars who refute this argument. One response in the corpus reads “We have to pray for any human being who calls to goodness and righteousness, regardless of their religion. Mandela did not fight Muslims, nor did he expel them from their land. He showed great respect to Islam and supported the struggle of the Muslim people of Palestine.” Another response described opposition to praying for Mandela as looking for controversy, emphasizing that Mandela's actions were those of one who believes in God. Similarly, the Prophet described Hatim al-Ta'i as a man of high morals and who has all the characteristics of believers. Prophet Muhammad forgave al-Ta'i's daughter and her people in honor of her father. In other contexts, a variety of sweeping statements and generalizations are discernible. For instance, Arab politicians were described by a participant as stupid, because they called the enemies of the Nation to occupy their countries. This statement is vague as it does not specify the identity of these Arab politicians or the identity of the enemies. It does not also show which countries are occupied and who is the occupier. Arab politicians were also described in the corpus as unethical. In another context, Arabs are accused of being inherently racist.

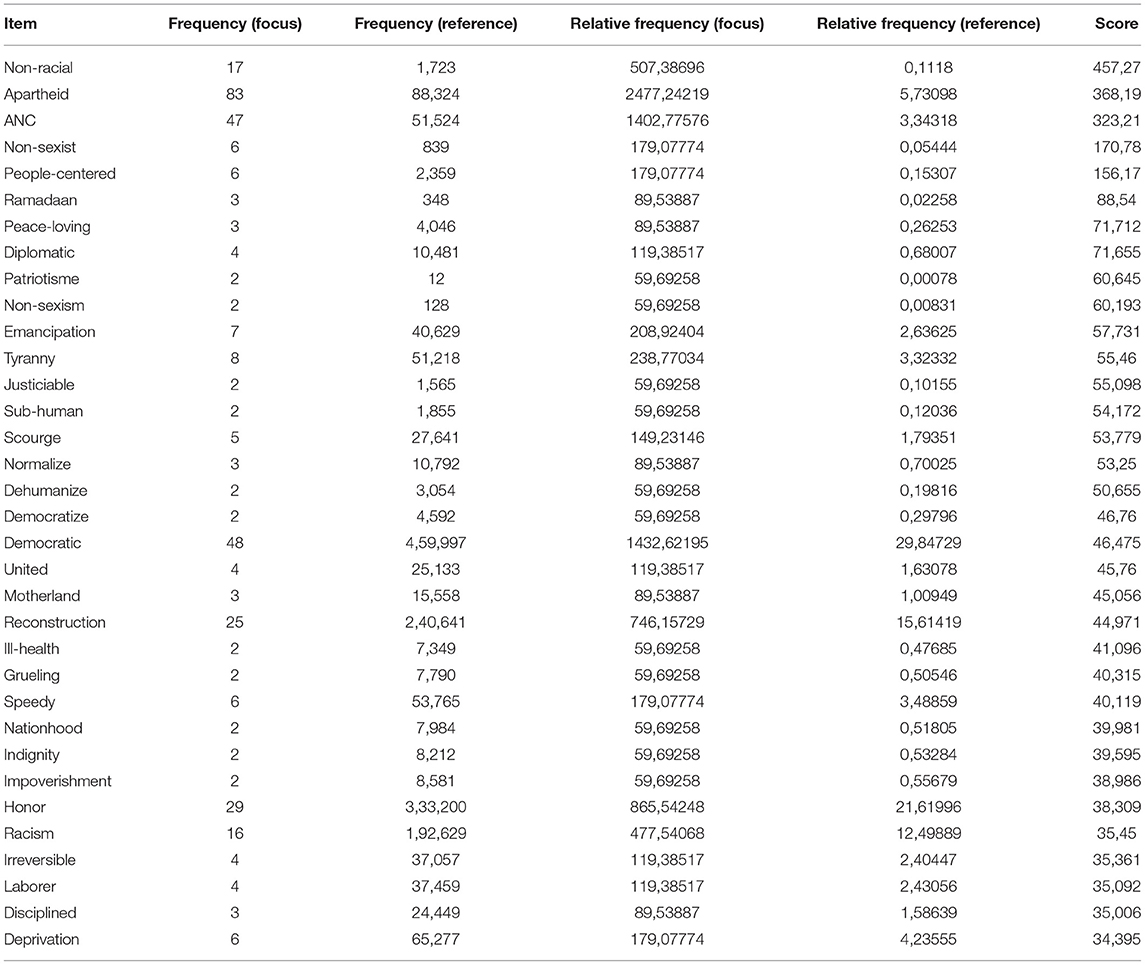

Obviously, the corpus abounds in topoi which are neither relevant to the death of Mandela nor are they of analytical significance for this study. The Muslim Brotherhood and its allies, the Syrian opposition, pro-Iranian organizations, the Southern Separatist Movement in Yemen, as well as Islamic fundamentalists all exploited the media coverage of Mandela's death to explicitly and implicitly express their own unrelated ideological views and address political issues in Arab countries and the Middle East. On the other hand, there are some topoi that were expressed by Mandela himself on more than one occasion, but participating politicians never referred to them. To highlight some of these topoi, a reference corpus that includes 33 of Mandela's speeches was used. The corpus consists of 18,131 tokens. Table 1 shows the frequent topoi in the reference corpus.

It becomes clear that Mandela himself highlighted topoi such as non-racialism and non-racial democracy, non-sexism, people-centered society, peace-loving nation, political emancipation, an entrenched and justiciable bill of rights, normalization of political situation, deracializing and democratizing, reconstruction and development, building a common sense of nationhood, impoverishment of people, indignities and degradation, cynicism and despair, deprivation and ignorance, and etcetera. Although many of the above topics are relevant to the current situation in the Arab world, the analyzed spoken corpus contains none of them.

Concluding Remarks

The purpose of this study was to analyze a spoken Arabic corpus about the death of Nelson Mandela through an investigation of the topoi employed by politicians from various countries in the Middle East to discover how they identified themselves in relation to others. The results of the study showed that the corpus abounds in topoi that are not directly related to Mandela or his death, but to heated political issues in the Arab world. Many politicians have shifted their focus away from the main topic, which was the death of Mandela, to conflicts and political plights in countries such as Egypt, Syria, Iran, Iraq, Yemen, and Palestine. The politicians used the programmes where they appeared as platforms to express their feelings, and to compare Mandela with Arab leaders. As noted, the discussion often digressed to the deployment and projection of the ideologies of participants and their respective countries. In many cases, these ideologies transcend national boundaries and are representative of Arab nationalism and identity in general. Frequent topoi in the corpus include leadership qualities of Mandela, leadership crises in the Arab world, imprisonment of Mandela, Arab Spring, reality, number, Mandela's legacy, tolerance, and reconciliation. The manipulation of discourse is also noticeable in various positions throughout the corpus. Although the corpus in general includes mention of Mandela qualities, some aspects of toxicity are also apparent.

The novelty of this study is in its methodology and approach to the analysis of political communication. At the time this study was recorded, it was the first that investigated the topoi of Mandela's death in Arab media and perhaps globally using such an approach; there are no known studies that employ a discourse historical approach (DHA) in the analysis of Arabic political discourse. Another aspect of novelty is that the analysis of topoi in this study is based on ample data that represent mainstream media as well as alternative digital media. Moreover, the analysis of political discourse would be incomplete should a researcher fail to pay attention to the linguistic features of the text. The corpus-based research methodology adopted in this study provides a list of useful computational linguistic methods that may help in understanding the discourse more objectively and in locating the diversified ideologies and identities involved in the corpus. Collocations, wordlists, concordances, and N-grams have been employed to unpack the political discourse about Mandela's death.

Despite these aspects of novelty, the study has some limitations. The study mainly focused on the topoi deployed in a spoken Arabic corpus. More studies are needed to investigate the topoi in other journalistic and literary contexts. Social media and websites abound with many elegies, articles, posts, and blogs about the legacy of Mandela. Further studies could deal with analysis of linguistic features such as transitivity, appraisals, and modality in discourse related to Mandela's death. More studies could also deal with rhetorical devices used by Mandela and the topoi deployed in his speeches.

Historical discourse analysis in general and the investigation of topoi in particular are promising CDA methods for analyzing political discourse. Topoi often differ from one political context to another, and may give clear glimpses of the ideologies of participants as well as the manipulative strategies employed by them to create an impact on their audience. DHA can be used as a framework of CDA analysis to investigate political discourse in the Middle East and beyond. Owing to its diversity, the Arab world is confronted with a plethora of sociopolitical and religious issues. Examples of these issues include political homogeneity, identity struggle, xenophobia, racism, refugees struggle and rights, extremism and terrorism, anti-Islamic discourse and islamophobia, religious violence and minority rights, to mention just a few. Although sociopolitical issues, political engagement, and religious issues (among others) pertaining to the Arab world are very widely studied across the humanities, the use of contemporary theories of critical discourse analysis in these studies has not been given adequate attention.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abdulkareem, M. A., and Qassim, A. (2017). The representation of ISIS in the American Newspapers in terms of Van Leeuwen's social actor approach: a critical discourse analysis. J. Basra Univers. Basra Coll. Arts 80, 1–37.

Al Kharusi, R. (2017). Ideologies of Arab Media and politics: A critical discourse analysis of Al Jazeera debates on the Yemeni Revolution (PhD thesis). University of Hertfordshire, Hatfield, United Kingdom.

Alemi, M., Tajeddin, Z., and Rajabi Kondlaji, A. (2018). A discourse-historical analysis of two Iranian presidents' speeches at the UN general assembly. Int. J. Soc. Cult. Lang. 6, 1–17.

Al-Sowaidi, B., Banda, F., and Mansour, A. (2017). Doing politics in the recent Arab uprisings: towards a political discourse analysis of the Arab spring slogans. J. Asian Afr. Stud. 52, 621–645. doi: 10.1177/0021909615600462

Arab Yousofabady, A. (2019). Critical discourse analysis of national anthems of Arabic countries located at Levant area based on Van Dijk model. Lesan Mobeen 10, 122–101.

Bruxelles, S., Ducrot, O., and Raccah, P.Y. (1995). Argumentation and the lexical topical fields. J. Pragmat. 24, 99–114. doi: 10.1016/0378-2166(95)94776-5

Buckingham, L. (2013). Mixed messages of solidarity in the Mediterranean: Turkey, the EU and the Spanish Press. Disc. Soc. 24, 186–207. doi: 10.1177/0957926512469393

Fairclough, N. (2001). “Critical discourse analysis as a method in social scientific research,” in Methods of Critical Discourse Analysis, eds R. Wodak and M. Meyer (Los Angeles, CA: SAGE Publications), 121–138. doi: 10.4135/9780857028020.n6

Ghasemi Asl, Z., and Niazi, S. (2020). Critical discourse analysis of representation of Iran in Asharq Al-Awsat based on Van Leeuwen's theories. Arabic Liter. 12, 23–42.

Hamdi, S. A. (2022). Mining ideological discourse on Twitter: the case of extremism in Arabic. Disc. Commun. 16, 76–92. doi: 10.1177/17504813211043706

Hamid, M. A., Basid, A., and Aulia, I. N. (2021). The reconstruction of Arab women role in media: a critical discourse analysis. Soc. Netw. Anal. Mining 11:101. doi: 10.1007/s13278-021-00809-0

Hattab, H. A. A., and Fakhir, R. (2020). The image of Arab immigrants in American and British press: critical discourse analysis. Int. J. Res. Soc. Sci. Hum. 10, 116–132. doi: 10.37648/ijrssh.v10i02.009

Hidayatullah, M. S. (2017). “The Khilafah discourse on Aljazeera and Alarabiya: a valuable lesson for Indonesian online media,” in International Conference on Culture and Language in Southeast Asia (Jakarta), 136–138.

Johnson, K. A., Sonnett, J., Dolan, M. K., Reppen, R., and Johnson, L. (2010). Interjournalistic discourse about African Americans in television news coverage of Hurricane Katrina. Disc. Commun. 4, 243–261. doi: 10.1177/1750481310373214

Kharbach, M. (2020). Understanding the ideological construction of the gulf crisis in Arab Media discourse: a critical discourse analytic study of the headlines of Al Arabiya English and Al Jazeera English. Disc. Commun. 14, 447–465. doi: 10.1177/1750481320917576

Krzyzanowski, M. (2009). “On the ‘Europeanisation’of identity constructions in polish political discourse after 1989,” in Discourse and Transformation in Central and Eastern Europe, eds A. Galasinska and M. Krzyzanowski (London: Palgrave Macmillan), 95–113. doi: 10.1057/9780230594296_6

Mohammed, T. A. S., and Banda, F. (2016). Mandela in the Arabic media: a transitivity analysis of Aljazeera Arabic website. Int. J. Commun. 26,123–154.

Momani, K., Badarneh, M. A., and Migdadi, F. (2010). Intertextual borrowings in ideologically competing discourses: the case of the Middle East. J. Int. Commun. 22. Available online at: http://mail.immi.se/intercultural/nr22/badarneh.htm

Richardson, J. E. (2004). (Mis)representing Islam: The Racism and Rhetoric of British Broadsheet Newspapers, Vol. 9. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing. doi: 10.1075/dapsac.9

Shousha, A. I. (2010). A critical discourse analysis of the image of Arabs in the American Press (PhD thesis). Alexandria University, Alexandria. Available online at: https://awej.org/images/Theseanddissertation/AmalIbrahimShousha/amal%20ibrahim%20shousha%20full%20thesis.pdf (accessed November 20, 2021).

Van Dijk, T. A. (2001). “Multidisciplinary CDA: a plea for diversity,” in Methods of Critical Discourse Analysis, eds R. Wodak and M. Meyer (Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications), 95–120. doi: 10.4135/9780857028020.n5

Van Leeuwen, T. (2008). Discourse and Practice: New Tools for Critical Discourse Analysis. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195323306.001.0001

Wenden, A. L. (2005). The politics of representation: a critical discourse analysis of an Aljazeera special report. Int. J. Peace Stud. 10, 89–112.

Wodak, R. (1994). “The development and forms of racist discourse in Austria since 1989,” in Language in Changing Europe, eds G. Graddol and S. Thomas (Bristol: Multilingual Matters), 1–15.

Wodak, R. (2001). “The discourse-historical approach,” in Methods of Critical Discourse Analysis, eds R. Wodak and M. Meyer (San Diego, CA: Sage Publications), 63–94. doi: 10.4135/9780857028020.n4

Wodak, R., Nowak, P., Pelikan, J., Gruber, H., de Cillia, R., and Mitten, R. (1990). Wir sind alle unschuldige Täter: Diskurshistorische Studien zum Nachkriegsantisemitismus. Berlin: Suhrkamp.

Youssef, S. S., and Albarakati, M. A. (2019). Features of Arabic and English use of self and other-presentation in political discourse. Int. J. Appl. Linguist. Eng. Liter. 8, 85–92.

Keywords: Mandela, Arab world, death, discourse-historical, topoi, corpus, media

Citation: Mohammed TAS, Banda F and Patel M (2022) The Topoi of Mandela's Death in the Arabic Speaking Media: A Corpus-Based Political Discourse Analysis. Front. Commun. 7:849748. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2022.849748

Received: 06 January 2022; Accepted: 07 March 2022;

Published: 25 April 2022.

Edited by:

Gopal Krushna Sahu, Aligarh Muslim University, IndiaReviewed by:

Huma Parveen, Aligarh Muslim University, IndiaValentina Marinescu, University of Bucharest, Romania

Copyright © 2022 Mohammed, Banda and Patel. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Tawffeek A. S. Mohammed, dGF3ZmZlZWtAZ21haWwuY29t

Tawffeek A. S. Mohammed

Tawffeek A. S. Mohammed Felix Banda

Felix Banda Mahmoud Patel

Mahmoud Patel