94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Commun., 12 April 2022

Sec. Science and Environmental Communication

Volume 7 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomm.2022.822471

This article is part of the Research TopicEvidence-Based Science Communication in the COVID-19 EraView all 13 articles

As the COVID-19 pandemic began, health authorities rushed to use social media to communicate information and persuade citizens to follow guidelines. Yet a desire to “come closer to citizens” often came into conflict with the very consequences of doing so—many social media interactions were characterized by complaint, resistance, trolling or misinformation. This paper presents a case study of the Danish Health Authority's (DHA) Facebook page, focusing on the initial phase of the pandemic and on posts about face masks. Face masks were chosen as an exemplar of the many topics where scientific research was being communicated as it unfolded, and where relations between science, policy, and politics were also evolving in public. In other words, topics where what should be communicated and why was unclear and unstable. A qualitative thematic analysis of the DHA Facebook page, grounded in the practice-based knowledge of one of the authors and feedback meetings with DHA staff, unpicks what kinds of engagements between authority and citizens occurred, both explicitly and implicitly. The analysis particularly looks for dialogue—as a mode of communication implicitly promised by social media platforms, and as a well-established ingredient of trust in relationships between experts and citizens. Drawing on Grudin's definition of dialogue as “reciprocal and strange,” we argue that the DHA's Facebook policy limited such encounters, in part by practical necessity, and in part due to professional constraints on the ability to discuss entanglements between health guidelines and politics. But we also identify “strangeness” in the apparent disconnect between individual engagements and collective responses; and “reciprocity” in the sharing of affect and alternative forms of expertise. We also highlight the invisible majority of silent engagements with DHA information on the Facebook page, and ask whether the visibly frustrated dialogue that ran alongside was a price worth paying for this informational exchange. The paper also serves as an example of qualitative research situated within ongoing practice, and as such we argue for the virtue of these more local, processual forms of evidence-based science communication.

As the COVID-19 pandemic unfolded, health authorities worldwide raced to communicate effectively, quickly, and with as wide a reach as possible. But what they needed to communicate to citizens was much less certain and stable than in typical public health scenarios. Research was fast-evolving and uncertain, with the inevitable corrections, caveats and retractions that followed. On top of this, health authorities could not wait for negotiations between science, health strategy, and politics to be completed; these processes were unfolding live on the public stage. Expertise in such scenarios is necessarily multiple; power is dispersed in complex and opaque ways; and many different informational needs unfold in parallel. To make things even more complicated, the proper relation between science and politics was itself at stake, and could not serve as a stable frame for discussing contentious public health measures. So health authorities needed to communicate about science; about science-in-the-making; about the relation between science and public health guidelines; and about the unsettled relations between politics and knowledge (Arjini, 2020). And they had to do so quickly—making it harder to find time to draw on existing communication research or conduct formative research along the way (Frontiers, 2020).

As with all public health messaging in recent years, COVID-19 communication has taken place within an expanded media ecology dominated by the promises and threats of social media platforms such as Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter—“forms of electronic communication … through which users create online communities to share information, ideas, personal messages, and other content” (Merriam-Webster, 2022). Institutions have been both bewitched and bewildered by the idea of coming closer to citizens through social media (Heldman et al., 2013; Korda and Itani, 2013; Teutsch and Fielding, 2013). Health authorities have entered Facebook, Instagram, and other platforms, negotiating new relations as the messiness of peoples' reactions to health information plays out in public (Canel and Luoma-aho, 2019; Lovari and Valentini, 2020; Sesagiri Raamkumar et al., 2020). Citizens have always spread misinformation, torn up leaflets from the doctor, ignored public health posters, or shouted at TV infomercials, but these responses come closer to authorities on social media, and seem to demand a more immediate response. This is a proximity that seems to help overcome barriers of authority whilst simultaneously highlighting the reason those barriers are there: questions about who moderates public speech become a daily challenge, both in terms of what citizens are permitted to post, and in terms of what authorities' employees are permitted to discuss (Andersen et al., 2012; Myers West, 2018; Chadwick et al., 2021; Lovari et al., 2021; Tsao et al., 2021).

The communication situation unfolding around COVID-19 was christened by the WHO and others as an “infodemic;” “an overabundance of information—some accurate and some not—occurring during an epidemic, that […] makes it hard for people to find trustworthy sources and reliable guidance when they need it.” (Tangcharoensathien et al., 2020). Misinformation spread on social media about the virus, the disease, its symptoms, prevention, transmission, and treatment, caused serious difficulties for authorities in implementing guidelines and restrictions—to some degree an unavoidable phenomenon in a novel disease scenario (Allington et al., 2021; Lovari et al., 2021). Calls were made to “treat the infodemic” with fast rollouts of informational inoculation, and researchers used the metaphor as a framing for research (Cinelli et al., 2020; Scales et al., 2021).

But what kind of treatment an infodemic requires is an open question. In addition to providing clear, accurate, and accessible information and managing the production and sharing of misinformation, we need to engage with citizens who hold opposing views or whose structural conditions restrict them from following accurate information and advice they might receive. Research on combating polarization and conspiracy theories on social media emphasizes the importance of recognizing participants' concerns and the community functions of these “bubbles” when addressing their members (e.g., Pariser, 2012; Harambam and Aupers, 2015; Del Vicario et al., 2016; Arceneaux et al., 2021), and recognizing that both those spreading and challenging misinformation can “behave badly” (Johansen, Marjanovic, Kjaer, Baglini and Adler-Nissen, in press).

This complex situation left health authorities with a dilemma. Health authorities increasingly recognized that “top-down” communication by experts needed to be supplemented by more reciprocal dialogue, but could they really provide the latter? What if the questions they were ready to answer were not the ones citizens want to ask? How could authorities balance the need to defend the status of their knowledge, with the need to recognize “unreasonable” concerns amongst resistant publics? How could they enact the transparency essential to building trust without airing too much uncertainty and “dirty laundry?” When is dialogue even appropriate—do people sometimes just want authoritative information, and is censure of dissent sometimes the most responsible strategy?

This dilemma is baked into social media, which were originally structured around notions of sharing, democratizing, and bottom-up community building, but nowadays host many groups whose communicative goals are far less democratic. Facebook contains what would earlier have been websites; constantly duplicates media from mass dissemination channels; and has been used to host helplines, Q&As, adverts and infomercials. As such it can be hard to navigate the relation between what is promised by the form of the platform itself, and what producers are actually willing to deliver. It looks like dialogue—but is it? If people expect dialogue but receive the shutdown of dissent, how will they react? This dilemma is nothing new—it arguably characterizes the history of science communication and its academic critique (Nisbet and Scheufele, 2009; Bucchi, 2017)—but it comes into sharp focus in the current situation and on social media, and its detailed contours need to be understood in order to improve practice (Scheufele, 2014; Jensen and Gerber, 2020).

This paper addresses how health authorities navigated dialogical relations with citizens on social media with respect to a case study: the Danish Health Authority's Facebook posts about face masks during the first phase of the pandemic. The Danish Health Authority (DHA) entered Facebook just before COVID-19 emerged; a baptism of fire that meant practices were fresh and malleable. The DHA Facebook Strategy aims to provide citizens with important health information “at eye level,” and to contribute to a greater knowledge of the DHA among citizens (Liebst, 2020).

Drawing from a unique data set of all the DHA's posts and citizen1 engagements during the first year of the pandemic, we chose to focus on posts about face masks. Face masks were a contentious issue from the start of the pandemic, where scientific evidence was being gathered in parallel with the announcement of health guidelines and political arguments, exemplifying the challenges of communicating when relations between institutions are playing out live. As a Nature news article asked in October 2020; “The science supports that face coverings are saving lives during the coronavirus pandemic, and yet the debate trundles on. How much evidence is enough?” (Peeples, 2020). Face masks directly impact citizens' everyday lives and cultural beliefs, and thus give rise to a multitude of questions, opinions, and critiques (Martinelli et al., 2021; Steiner and Veel, 2021). They are designed to lower risk, but authorities worry that their use might also amplify risky behavior (see Jørgensen et al., 2021). Denmark also offers an interesting case in relation to face masks, as there is a high degree of trust in government and compliance with COVID-19 health measures, but also a history of controversial political resistance to the wearing of face coverings such as the niqab and burqa (Perolini, 2020). Indeed, the requirement to wear face masks in public arrived later in Denmark than in many other countries, and rather suddenly.

We present a qualitative analysis of the case supported by quantitative description of the Facebook engagements, aiming to provide a richer understanding of what happens when health authorities enter purportedly dialogical platforms. We hope that our research provides locally situated knowledge that might help to guide future practice. The case is further used to ground a discussion of more theoretical concerns about what dialogue is and can be in such situations. The paper is thus an example of an interface between research and practice—but not one where the research was commissioned by the practitioners, or where the practice was directly and explicitly guided by the research. Rather, one of the authors (FM) was employed as a moderator on the DHA's Facebook platform at the same time as she was researching the platform for her master's thesis, which then became the present article in collaboration between researchers from three different faculties at the University of Copenhagen, including two (R A-N and NJ) who are involved in a wider research project How Democracies Cope with COVID-19 (HOPE)2.

The research was thus grounded in practice-based knowledge, and questions and observations from the research fed back into the Facebook moderators' discussions, both formally and informally. We presented the findings to the DHA's communication team at several points, and at the end of the project held dialogue meetings with three leaders and three moderators, to ground our analysis in their perspectives on Facebook and the relevance (or not) of our findings. As we will consider further in the Discussion and in relation to Jensen and Gerber's call for evidence-based science communication (Jensen and Gerber, 2020), this is research with practice, more in line with qualitative traditions of participatory and action-based research or auto-ethnographic science studies, than with attempts to gather more rigorous and generalizable quantifiable knowledge about tightly characterized communicative scenarios. In the Analysis section of the paper, we weave together our quantitative characterization of the data, qualitative analysis of the post types and forms of citizen engagement, and comments from the DHA feedback meetings, along with our interpretation of the relationship between intentions and outcomes.

In this last introductory section, we situate the concrete dilemmas outlined above within the science communication literature. Science communication studies have produced many models of the relations between scientific experts and publics. Across diverse terminologies, three fundamental categories emerge: (1) information dissemination from experts to publics (often referred to as the “deficit model”); (2) experts listening to publics; and (3) a more reciprocal or two-way engagement, where the boundaries between expert and public are challenged and it is accepted that the topic under debate cannot be fully captured by any one form of knowledge. This classification was originally introduced as part of an argument for shifting from (1) toward (2) and then (3), fueled by social change as well as sociological studies emphasizing the failures of traditional dissemination for securing public support and for supporting robust, socially appropriate decision making (Wilsdon and Willis, 2004).

Following this important shift around the end of the twentieth century, a variety of more nuanced analyses of what takes place in science communication have unfolded—alongside a subtler critique of the normative dimensions of a desire for dialogue (Broks, 2004; Bucchi and Trench, 2008; Einseidel, 2008; Trench, 2008; Irwin, 2009; Davies and Horst, 2016). Five key conclusions from this field guided us in the present analysis:

• First, that no form of relation is inherently good or bad; dissemination and dialogue can be appropriate in different scenarios.

• Second, that in many communicative situations all three forms of relation occur together and interweave—particularly over an extended period of time.

• Third, that the role of science communication in participants' identity and culture, and the interplay between cognition and emotion, is often crucial to the outcomes.

• Fourth, dialogue is a complex phenomenon and appearances can be deceptive; paying close attention to who says what, and with which affective content and epistemological consequences, is crucial to understanding a particular scenario.

• And fifth, “improper” engagement—where publics do not do what is expected, or fail to play by the rules—often reveals flaws in the producer's understanding of the scenario, and of the social context in which science communication unfolds.

Our analysis of the case study exemplifies all five principles, and the way in which nuance can emerge when they are taken as starting points, rather than starting from a normatively charged assumption that more reciprocal engagement is always good.

A key concept within these science communication models and for our analysis is dialogue, which has received many definitions, across disciplines and over millennia. We do not intend to contribute to the literature on dialogue itself, but instead interrogate the concept within our context. Within science communication practice “dialogue” has been too frequently uninterrogated, and requires deeper critical reflection within science communication scholarship too (see, e.g., Chilvers, 2013; Davies, 2014). It can be an overly flexible way of referring to a huge diversity of forms of interaction, highlighting the instability of the boundaries between the three forms of expert-public relation outlined above. Calls for dialogue can also indicate a desire for equality that is more tokenistic or instrumental than authentic, or which simply cannot be met in practice (Kerr et al., 2007; Einseidel, 2008). To understand an instance of science communication, we therefore follow Davies (2019) and Edwards and Ziegler (2022) in arguing for an STS-inspired approach that examines not just explicit exchanges between scientists and publics, but also “disassembles” the multiple hidden actors involved.

In relation to healthcare settings, Reid (2019) argues that “The characteristics of health dialogue include an equal, symbiotic health relationship between the patient and the healthcare provider, and reciprocal health communication toward reaching an identified health goal via a health message”—which seems like a far-away dream in the COVID-19 scenario. In this paper, when asking whether dialogue occurs, and then asking how this relates to ideas about the relations between experts and publics, we draw on Grudin's (1996) description of dialogue as characterized by reciprocity and strangeness:

By reciprocity, I mean give-and-take between two or more open minds or two or more aspects of the same mind. This give-and-take is open-ended and is not controlled or limited by any single participant. By strangeness, I mean the shock of new information—divergent opinion, unpredictable data, sudden emotion, etc.—on those to whom it is expressed. Reciprocity and strangeness carry dialogue far beyond a mere conversation between two monolithic information sources. Through reciprocity and strangeness, dialogue becomes an evolutionary process in which the parties are changed as they proceed. (Grudin's, 1996, 12)

This is also a high bar, and we do not use this definition in order to suggest that the DHA should be facilitating “strange and reciprocal” dialogue. Rather, we use it to sharpen our attention to what is actually desired, promised, and achieved in purportedly dialogical science communication. As a way of seeing what is missing, as well as what is present—and looking for this not just in the explicit back and forth between the authority('s proxies) and those engaging with Facebook, but also in interactions between citizens, and in invisible “reading” that leaves no trace in the comment threads (see also Davies, 2019; Edwards and Ziegler, 2022). We unfold the multiple forms of engagement present in this single case, and the diverse relations they imply. In the Discussion, we also consider the fragile conditions that supported this ecology of interactions—speculating about features of the face mask debate that allowed for a balance between authority and citizens that was later challenged when the dominant question became vaccination.

We first did an initial quantitative descriptive analysis to explore and characterize the data, and help select material for an in-depth qualitative analysis (Creswell and Plano Clark, 2007; Hollstein, 2014). As described in more detail below, the qualitative thematic analysis was developed through an initial pilot study of a key DHA post, and then developed iteratively on a larger subset of 13 highly commented posts.

The analysis was grounded within FM's work as a moderator on the Facebook platform; her situated knowledge (Haraway, 1988) of how moderators experienced working with citizen engagements inflected the developing research questions and thematic categories. And finally, a more explicit dialogue between research and practice informed our interpretations; the authors presented to the DHA during the study and then conducted interviews at the end with three leaders (“leaders meeting”) and three moderators (“moderators meeting”) in order to enrich and sense-test the analysis; the leaders also read the final manuscript.

This study originated with the unique opportunity to gather all Facebook posts, comments, and replies to comments (collectively “engagements”) from the DHA's Facebook page between February 29th and October 11th, 2020. This was conducted under a data agreement between the Danish Health Authorities and the HOPE project3 at the University of Copenhagen, which includes a commitment to use the data only for scientific purposes, not share it outside of the team and ensure full anonymity.

At the start of our data collection period the Facebook page was relatively new, and the number of followers increased during the period—by the time of the leaders meeting, they reported 175.000. The data included 748 DHA posts, 31,535 comments, and 44,945 replies. This does not include 564 citizen engagements that contained only visual elements, as our analysis was only of written text. Of the combined engagements, the DHA were responsible for 14%, suggesting that they are active in responding to comments as well as producing posts. There was a mean of 2.44 engagements per user, with only seven citizens engaging more than 100 times during the data collection period. Only 4.6% (3,538) of the engagements were hidden by DHA moderators. We delimited the data set by selecting all engagements mentioning “face mask” or common Danish synonyms (“mundbind,” “mundble,” “mb,” “fjæsble,” “maske,” “mundvand,” “mundværn,” “bundbind,” “mundbeskyttelse”), which yielded, 7,895 engagements. This was then used to select key posts for the qualitative analysis (see below).

Figure 1 reconstructs and translates into English a typical Facebook post, consisting of a capitalized title, brief paragraphs of text often including short bullet points, and sometimes further supplemented with infographics, a picture, or a video. Comments are entered below the main post, and replies can be made to comments and to each other. The DHA posts on face masks included recommendations, regulations, how-to guides, or a combination, and the title was typically a question such as “What type of fabric mask can I use?” or “Should you wear a face mask to school?”, or an informative heading such as “This is how you use a face mask” or “Face masks are required on public transportation.” Figure 2 reconstructs an excerpt of a (translated) comment thread, showing several citizens engaging in a back-and-forth exchange with occasional input from a DHA moderator.

Figure 1. Exemplar post about face masks from the Danish Health Authority's Facebook page. Translated into English.

Figure 2. Exemplar comment thread from the Danish Health Authority's Facebook page. Reconstructed and translated into English. Please note, this figure is split across two pages.

An engagement was hidden by the DHA moderators if it could be characterized as dangerous misinformation, if it had a racist attitude or aggression toward other Facebook users. Engagements that only or mainly contained a link or were considered spam were also hidden. In extreme cases the employees could delete engagements—if the content was particularly offensive, insulting, or racist in a way that they considered could not be tolerated. If the engagement included sensitive personal data, the content was also deleted to protect the person [practice as stated in appendix to Liebst (2020), DHA internal document]. As was explained by one of the DHA communication leaders: “We cannot delete misinformation. We can delete if someone is throwing a bunch of middle finger emojis, but if someone is trying to convince with information or links to other pages then we cannot delete it,” (Leaders Meeting, 2021), though as we discussed at the leaders and moderators meetings, there is a grey zone between dangerous or insulting content, and persuasion or misinformation that the DHA might disagree with. Facebook itself also can hide and delete engagements without knowledge from the DHA, so we are not able to provide statistics on this. But despite the challenges of this work, the moderators and leaders also talked of their commitment and excitement at being involved. For example, one moderator said; “It was exciting to get going and see if we could go into dialogue, AND we can! It's so cool when it works … I also think it's fascinating to try and understand how on earth they can be so far from what I think is reality” (Moderators Meeting, 2021).

The face mask engagements were analyzed using Python Programming for Data Science, with two purposes. First, giving a better description of the data set by characterizing the frequency of engagements, by which user, and how this unfolded over time, giving general information about the pattern of posting on the Facebook page. Second, this descriptive quantitative analysis was used to help select posts for the primary qualitative analysis, where we investigate the character of dialogical exchanges between DHA and citizens in more depth.

We carried out a pilot study prior to the qualitative thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2006) using the DHA Facebook post “Frequently asked questions about the use of face masks” from July 23rd, 2020. This post was chosen as it occurred at a key point in the evolution of face mask guidance—shortly before face masks were made mandatory and the DHA updated its guidelines—and also as it generated many engagements (437 in total, 221 of which mentioned face masks at least once). In the pilot study we searched for phrases relating to the guiding interests outlined in the introduction, coupled with an openness to emerging themes. The primary interest was how citizens and the DHA engaged with each other—we looked for when and how citizens provide, seek, contest, or co-create information; for signals of trust or distrust; for dialogical patterns or their absence; and for markers of expertise and (dis)respect for expertise.

The full qualitative analysis was then conducted on 13 key posts relating to face masks, including the pilot study post. In the period February 29th–July 8th, before the DHA explicitly posted about face masks, 7 posts with the highest number of mentions of face masks in the comments and replies were selected. In the remaining period, a subset of 6 of the DHA posts directly relating to face masks were selected by hand, choosing posts with high numbers of engagements but also in order to give good coverage across the period, and capture responses to key changes in the guidelines. We used the pilot study to initiate the recursive development of a thematic coding tree, working through each post and its engagements chronologically and cycling back through the material as the themes evolved and new elements emerged. The tree was structured according to key DHA-citizen engagement patterns, which also structures the Analysis section below.

The coding was conducted in NVivo by FM, and the development of the codes and the coding tree were continuously discussed in relation to excerpts with other authors. The conceptual interpretation of the themes was also developed in dialogue across the author group and refined through discussion with colleagues in the DHA Facebook team. The data material was in Danish, but quoted engagement extracts are translated into English.

This research builds on a unique collaboration between research and health institutions. Author FM was both employed in the HOPE project at the University of Copenhagen and at the DHA. FM's key task at the DHA was to monitor the Facebook platform and she was thus both producer and researcher of the same phenomenon. This situated position requires reflective consideration of its impact on the work, but has had several valuable impacts. FM's dual role brought insider knowledge about how the Facebook platform worked and evolved throughout the research period, and enabled us to refine our analysis through dialogue with and in practice, not just with FM but also with her colleagues.

Throughout the research period, FM and others from the HOPE project shared preliminary findings and open questions with DHA communication staff. At the end of the project we conducted two more formal meetings, which were audio-recorded and transcribed. First, a 1 hour “leaders meeting” with three senior staff members from the DHA communication department. In addition to presenting our findings and asking for feedback on our ideas about DHA-citizen engagement patterns and their perspectives on misinformation, we discussed how the DHA had experienced the communication challenge presented by the pandemic, how their responses evolved, and what future steps were planned or wished for. Second, we carried out a 1.5 hour “moderators meeting” with three DHA student assistants employed to monitor the Facebook page. Specific additions for this conversation were to discuss their experiences monitoring the DHA Facebook page, and their views on the DHA communication, information flows and practical work.

In the Analysis section of the paper, we weave together our quantitative characterization of the data, qualitative analysis of the post types and forms of citizen engagement, and comments from the two DHA feedback meetings, along with our interpretation of the relationship between intentions and outcomes. Quotations are from citizen engagements, unless indicated as from the “leaders meeting” or “moderators meeting,” and all quotes are from 2020, unless otherwise indicated.

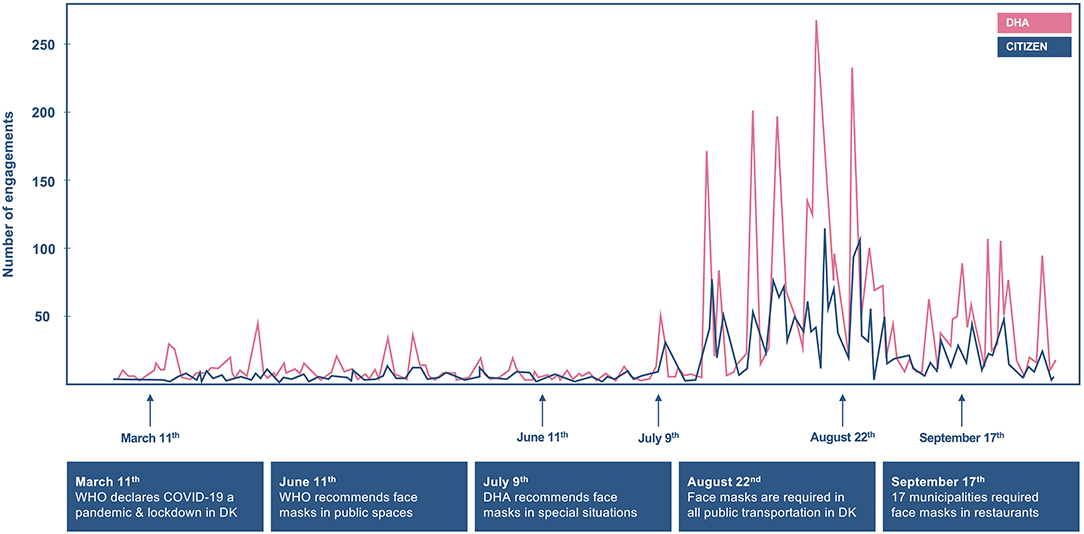

Figure 3 illustrates the incidence of engagements that mention “face masks” over the period, divided by whether engagement was by the DHA or citizens. The vertical lines on Figure 3 indicate key announcements, DHA recommendations or new government regulations (see Table 1 for a summary list). Face masks were mentioned throughout the period, including prior to the first formal face mask mandate on July 9th and the DHA's first post about masks. There was an average of 7.45 engagements per day before the first mask recommendation was posted on July 9th, and an average of 73.36 engagements per day after that date and until October 11th. There is no consistent relation between key announcements and frequency of engagements, but there are noticeable peaks when face masks were made mandatory in new situations. There is clearly some correlation between the peaks of DHA and citizen engagements (Kendall-Tau correlation coefficient 0.599), hinting that back-and-forth communication is occurring.

Figure 3. Number of engagements concerning face masks on the Danish Health Authority's Facebook page, posted by the DHA and by citizens, from March 1st to October 11th 2020.

At the leaders meeting it was explained that the DHA had entered Facebook because there “has been a desire to be much more citizen oriented and much more at eye level” and that “There has been no doubt that the DHA should be represented on Facebook, because it is the biggest social media platform in Denmark and it is where one meets the citizens.” This reflects a general sense that institutions must use social media, and the often rapid way in which they have to launch such platforms. The nascent Facebook platform was then rapidly overtaken by the COVID-19 pandemic, and the DHA's communication role and resources were greatly expanded:

We have never ever had such a prominent role in relation to the entire population. We used to manage it ourselves in connection with efforts or campaigns or something else, where we of course have reached out and entered into dialogue and everything, but we have never been as ‘available' to the population as we have been during this pandemic. (Leaders Meeting, 2021)

The Facebook page was driven by two key imperatives, to “answer questions” and “be present” (Leaders Meeting, 2021), and to do so informed by professional expertise. The DHA thus chose to employ internal moderators, who draw on experts to develop an answer catalog that evolves as questions change, rather than employing an external company to moderate the site. This was only possible due to the unprecedented budgets allocated to COVID-19 communication—and described at the leaders meeting as a luxury, offering citizens an unusually responsive service to citizens.

The DHA see their readiness to answer questions and respond to comments in this relatively direct way as dialogue. Yet despite the huge investment in the platform during COVID-19, capacity was still limited relative to demand. The description on the Facebook page indicates that during busy periods, individual citizens can expect a maximum of one to two responses per week, and that questions on posts more than 4 days old will not be responded to Sundhedsstyrelsen (n.d.). There were also serious limits on what the moderators could enter into dialogue about. In the leaders' meeting they drew a distinction between political decisions that moderators cannot comment on, and professional recommendations and guidelines, which are the appropriate remit of a health authority. Moderators were also instructed to give only general and official guidance, not individual or personalized advice. Here we see a restricted practice of dialogue developing, shaped by the institutional role of the platform as well as by resources—questions concerning certain matters can be responded to in certain ways, and without sustained interaction or personalized contact with individual citizens.

So how did citizens engage with this offer? The overall impression from our analysis and from talking with the DHA staff was one of intense demand, in the context of citizen confusion and frustration around multiple and shifting sources of information. As one user wrote early in the pandemic:

I follow the Danish guidelines because I live here, and I have confidence in the Danish health care system as they are more competent than we are – but I will not hide that I am gradually becoming more and more frustrated by directly opposing orders all around – March 12th

As outlined in the Methods, we selected 13 key posts and responses for the main qualitative analysis. This thematic analysis focused on forms of communicative engagement between the DHA and citizens engaging on Facebook, asking when citizens provide, seek, contest, or co-create information; how expertise and trust are indicated, and whether and how dialogical engagement occurs. We were sensitized by the five principles outlined in the introduction that emerge from critical engagement with traditional science communication models—acknowledging that multiple forms of communication often coexist, that their normative status is contextual, that key actants may not be visible in the explicit exchanges, and that affective responses and unruly “misbehavior” are not just mess but a critical part of what occurs (e.g., Horst and Michael, 2011; Davies and Horst, 2016; Davies, 2019). The three key categories that emerged are outlined below. Each is a more explicit description of the “top layer” of what is going on—but we also discuss the multiple layerings of forms of communicative engagement present within each. We then conclude with a fourth cross-cutting theme looking at the link between strong emotion and dialogical patterns.

Citizen engagements categorized as “seeking information” posed questions or requested clarification or further detail. For instance;

I am wondering if it is true that disposable face masks can be reused if microwaved?—August 5th

Is the use of a face mask required when visiting one's general practitioner?—September 19th

These are typical examples of citizens asking detailed questions, trying to “do the right thing” and follow restrictions and recommendations, as they ask for help on how to navigate in their daily life during the COVID-19 pandemic. Notably though, the questions asked were not always related to the topic of the original post—an indicator that agendas can be shifted by “non-experts” even if they are requesting information from experts.

Not all questions were as clear and precise however, and many engagements appeared as an informational request but where the question posed could be read as rhetorical, sarcastic, or used in order to express an opinion about the perceived inconsistency or irrationality of a particular guideline or regulation. For instance;

Could the Danish Health Authority soon take a stance on their opinion regarding the use of face masks among the Danish population?—July 23rd

Why is one required to wear a face mask in restaurants but not in retail shops  This makes no sense to me

This makes no sense to me  —September 19th

—September 19th

The first example should be read in the context of the DHA taking longer to make a decision on their face mask guidelines than most other European countries, a gap that allowed debate and uncertainty to flourish. These “pseudo-questions” seem to express frustration, but they are also requests for information, and commentary; they offer affective information to the DHA about how citizens feel, as well as requesting facts or actions.

Citizens who seek information behave roughly as the DHA describes in their strategy. They place the DHA as the expert, either implicitly by seeking guidance or explicitly by saying that the DHA should know how to guide citizens. Such engagements were typically easy to answer by the moderators as answers were available on the DHA webpage or answer catalog, falling within the DHA's self-defined area of responsibility. But in another looping between traditional science communication models, this apparently clear example of “expert informs citizen” was also a route by which the DHA learnt from citizens about what they wanted to know. Thus, from the perspective of information on COVID-19, the engagements were classic dissemination, but from the perspective of information on what citizens want to know, the engagements were also an example of experts listening to publics.

This category describes citizens who give feedback on the DHA and their guidelines. Most feedback was negative—as expected on social media, where approval is often expressed as a simple “like” or silence, whilst negative emotions are more likely to result in extended expression. Feedback is characterized by being evaluative rather than information-seeking. For instance;

Thanks to the Danish Health Authority for the great work you are doing—August 5th

Good to know about the optimal use of face masks and how best to store them—September 19th

No thanks  —August 15th

—August 15th

I will not wear that shit—September 19th

A lot of the engagements in this category gave feedback specifically about how the DHA changed its position on face masks. Some citizens defended the work of the DHA, often contextualized with reference to the complex situation, but many were angry and even aggressive. One citizen wrote:

I can't believe it!!!! Since all this started you've said that we should cough and sneeze in our sleeves to avoid infecting others, and now 5 months later you say it might be better to use a face mask, as it probably works better???? A kindergarten teacher would have managed the situation better than you. Unbelievable that you get paid for this unbelievable mess! – July 9th

The DHA replied with:

Hi [name], We still recommend that people cough and sneeze into their sleeves. But in certain situations, one can consider wearing a face mask. For example if you have symptoms or are infected with the novel coronavirus and need to go to hospital, if you are on your way back home from the airport, or if you can't stay distanced from a person who is at high risk.

We still do not recommend that healthy people moving around in public spaces use face masks. – July 9th

The citizen points out inconsistency over time, and interprets it as incompetence, with a sense of being let down by a well-funded institution. The interpretation of changing advice as incompetence was commonly expressed, both by citizens who were pro- and against the use of face masks.

How to manage shifting knowledge is a long-standing challenge for public health authorities, where frequent changes of guidance can reduce trust—for example, as advice around drinking in pregnancy or healthy diet composition changes. This has been used to argue for communicating honestly about the limitations of knowledge—so that when guidelines change, publics will be less likely to lose trust (e.g., Irwin, 2008). In the case of COVID-19, guidelines changed regularly, and uncertainty surrounding the scientific knowledge on which they were based was unusually public. Nonetheless, we still saw emotional reactions to this “shifting ground”—and it is unclear whether more explicit transparency about uncertainty would have helped or hindered peoples' positive feelings toward the DHA (though see Petersen et al., 2021).

The reply from the DHA follows a classic pattern, answering with dissemination of information as if the citizen had asked, “Should I wear a face mask and when should I wear a face mask?”, rather than reacting directly to the feedback and frustration that is clearly expressed. Here we see the severe limitations of dialogical engagement—the moderators are not able to acknowledge the feelings of the citizen nor defend the DHA. Rather, they perform their informational, “non-political” function, addressing the collective “people” rather than the individual citizen, and deliver whatever they best can within the constraints of this role. To return to Grudin's (1996) definition of dialogue as characterized by “reciprocity and strangeness,” this exchange inverts reciprocity—it is controlled and closed down by the expert. However, there is certainly something “strange” about it. Not the “strangeness” that might be generated by the DHA openly (and thus vulnerably) engaging with the citizen's feelings, but there is an “emotional shock” generated by reading and perhaps receiving this exchange. We learn something about what is possible for the parties, even if they do not engage in learning more about each other's opinions.

Until July 2020 the DHA insisted that there was not enough evidence to recommend that face masks be worn in public. They then changed their opinion, stating that new scientific knowledge and experiences from other countries pointed toward face mask use by healthy individuals reducing infection rates. In addition to the more emotional reactions discussed above, there were also many citizens accusing the DHA of being overly influenced by politics in this shifting guidance;

A true shame to witness how you constantly change your opinion in accordance with the desires of politicians in Christiansborg [Danish Parliament] – August 15th

And 5 days after the CEO of the DHA, Søren Brostrøm, was announced as a nominee to a seat at the WHO committee (to which he was appointed a month later), a citizen wrote:

Unbelievable how you have changed your mind regarding the effect of face masks. Funny to see how moving up the ranks can change one's opinion. I am wondering whether you [Søren Brostrøm] sleep well at night? – September 19th

Many of the engagements giving negative feedback about the DHA's political role revealed a lack of knowledge about how the health authorities, the state virological institute, and government differ in their duties and are meant to interrelate—a perception also expressed at the leaders meeting:

Citizens believe that it is the DHA who decides why there should be a Corona passport, assembly limits, and that everyone has to get tested all the time – and it is not. (Leaders Meeting, 2021).

In this engagement, a citizen gestures toward politics as a rather amorphous phenomenon, expressed by the lack of agreement between the different institutions:

One day face masks are not necessary at all and the next day it is absolutely necessary. What happened in 24 hours? Unfortunately, this is a lot of politics. We need answers to a lot of things. And why do the State Serum Institute and the Danish Health Authority not agree with each other, and then the Minister of Health is of a third opinion? – August 15th

The DHA and other authorities thus face the extra challenge of communicating what it is they are meant to do and what they cannot; where their power lies and why scientific and political considerations do not always align. It is tempting to suggest that the “feedback” discussed in this section should not just be read as a comment on the DHA's official actions, but also on the presentation of what the DHA is. Citizens “behaving badly” here show us cracks in the foundations on which a more “proper” dialogue about guidelines could be conducted. Negative feedback is not an explicit invitation to dialogue—but it could be a prompt for Grudin's (1996) “strangeness;” to discussions about how politics and science entangle. Whether social media would be a good place for this is of course a complex question.

The third category of citizen engagements we identified were those where the citizens themselves shared knowledge and information, either positioning themselves or others as having competing expertise. This sometimes overlapped with the previous category of giving feedback, but has a distinct sense of offering content to the DHA and/or other readers, and often with apparently good intent. As one of the DHA employees at the leaders meeting said; “they are convinced that they can help others.” For instance, in this engagement a citizen responds to the post on face mask recommendations, questioning the medical-scientific knowledge of the DHA;

DHA - face masks are not safe because microparticles can enter from the sides. They do not cover 100%. If they were to do so, we would each require custom-made masks… – July 9th

The second excerpt below is addressed to a general “you” rather than to the DHA, and offers a lively description of the user's beliefs about the dangers of face masks:

For a short time, the mask provides protection, but the mask quickly fills with your exhaled air, moisture and your own bacteria and virus – coronavirus, if you are infected. And you inhale all of that deeply into your lungs with each breath. And the breathing is deep due to the greater amount of carbon dioxide and the lack of oxygen. You are actually infecting yourself. At the same time, the now saturated mask is a pure infection bomb, causing you to also infect your surroundings. The masks are a bigger part of the problem than they are of the solution. Everyone is better off without. Of course, changing the mask often could work for you but everyone can certainly not afford so many masks – July 9th

This explanation circulated widely in the early phases of the pandemic, expressed by citizens and some politicians and even medics. It draws on everyday intuition—it sounds sensible—and on situated knowledge about how people use face masks in the context of limited resources or supply. This engagement has a conciliatory yet insistent tone that might make it more palatable than the shouty exclamation marks and capitalized sentences seen elsewhere (see examples in the section “Emotional Off-Loading in Broken Dialogical Chains” below). As such, it is arguably more worrying to the DHA, and exemplifies the huge grey zone of misinformation-in-the-making that unfolded as people combined everyday knowledge with other information sources whilst scientific studies were unfolding.

The writer of the previous engagement acted implicitly as a bearer of knowledge while others were more explicit about their source of expertise and how it related to that of the DHA: coming from personal experience, professional background, or repeating the claims of other public figures or authorities. In the following two excerpts, citizens provided information to the DHA and other readers based on their personal experience;

Have you [The DHA] or the politicians been out in society? In the places I'm moving around in 7 out of 10 people (approx.) use face masks wrongly. No matter how much information you provide. They touch it constantly, put it on and off, e.g., when talking on the phone, etc. – August 15th

Many of us living with anxiety cannot wear anything in front of our face as we, in certain situations, can't breathe in the first place. – August 15th

These citizens either explicitly or implicitly criticized the DHA's ability to understand how their communication is received, or challenged the applicability of DHA recommendations to daily life. These posts often highlight a disconnect between authority and society, a situation that works fundamentally against Grudin's “reciprocity.” It is still clear that the DHA is in control, and the citizens seem to be attempting to better inform the authority rather than requesting more control for themselves.

Other citizens positioned themselves as holding and being closely in contact with relevant professional expertise.

It is not true – a face mask is protective equipment that protects in both directions… I was employed at the epidemic section at ‘Riget' [National Hospital] and have never been infected during my 7 years there  – August 5th

– August 5th

“IS IT HARMFUL TO THE LUNGS TO WEAR A FACE MASK?” “No, there is nothing suggesting that” [text from the DHA post]. Then why are security personnel at my workplace advised not to wear them for more than three consecutive hours, as the body needs to recover beyond that? (…) It is contradictory information and I have more faith in what I am told by the security personnel – July 23rd

These claims to authority were potentially influential and arguably even relevant during this phase of the pandemic. At the time, there was no scientific consensus on how or whether face masks influenced infection rates in different settings, and different national health authorities drew different conclusions about the way to balance potential benefits and risks in relation to supply issues, potential behavioral impacts, and political pressure. However, the competing professional positions presented in these engagements were often unstable, and hard to evaluate. Does a surgeon know about the value of wearing a face mask in public based on the knowledge of wearing a face mask in the operation room? Is that specific information useful to the non-scientific citizen? Does it enlighten citizens to know the details or is it obscuring the message from the DHA to a population it needs to act quickly? These engagements are potential openings to dialogue—they stage a more equal relationship between the authority and the citizen—but they can only be responded to by the DHA in a way that affirms the authority's position and informational role, further restricted by the need for clear action.

A final kind of expert positioning was when citizens referred to or argued with statements from other persons or groups presented as experts—for example, informing the DHA that “some researchers are of the opinion that COVID-19 is airborne and for that reason it might be more infectious than initially anticipated” (August 5th). It was common for posts to link to other media articles, Facebook stories or webpages, either as an isolated engagement or as part of an argument or exchange. More often than not, the links went uncommented, but sometimes citizens react to each other's links, as in this excerpt;

You use Ekstra Bladet [Danish tabloid newspaper] as your source! A medium that consistently distorts the truth to appeal to emotions and trigger outrage. It would be more convincing if you were linking to real peer reviewed research so we can avoid the fake news that is currently flooding social media. – July 9th

Citizens also referred to and/or linked to scientific articles from peer-reviewed journals, often including a significant amount of detail. Whether they were scientifically correct in their argumentation was often unclear, but they were clearly making a claim to expertise and trustworthiness. As above, we might wonder whether this information is useful to other readers, and whether the DHA should censor the “wrong” interpretation of potentially influential scientific claims.

More obviously false information also flourished, with the repetition of common COVID-19 conspiracy theories about, e.g., the pandemic being fake and the vaccine being a vehicle for Bill Gates to inject people with ID chips (Tjekdet.dk., 2020a,b). Yet even these claims were often allowed to sit on the page—the DHA needs to maintain an appearance of openness to dialogue, even if their capacity to engage dialogically is severely limited. There's a wicked problem here—in order to try and maintain the trust so crucial to citizens following health guidelines, the authority feels it has to host information that directly contradicts those guidelines and the knowledge on which they are based. This problem cannot be easily solved with censorship. Citizens claiming expertise and actively attempting to participate in the circulation of knowledge suggests a more reciprocal dialogue, but this is not what we observed. Thus, citizens often appear to be engaged in a fruitless reverse dissemination toward the DHA—though our discussions with DHA staff suggested that these engagements did have impact, if not in the way intended.

Across the three categories outlined above, many engagements had a highly emotional tone—using multiple exclamation marks, capitalization, swearing, and emphatic language;

I cannot believe it!!!!

BUT FOR FUCK'S SAKE, THINK ABOUT THE REST OF US; SOME OF US ARE EVEN IN THE RISK GROUP OF A PRETTY SEVERE COURSE OF DISEASE – THINK ABOUT US

DAMN, how difficult can it BE to understand this.

Negative affect and emphatic statements are fundamental features of social media communication, especially around controversial topics, but are sidelined in the DHA's Facebook strategy. The moderators are trained not to engage with negative affect directly, but instead respond as if the user is making a reasonable request for information—a strange negation with a paternalistic flavor. We should not assume, though, that this is a bad response—or that citizens get nothing positive out of such behavior. Perhaps these explosive contributions are a kind of emotional “off-loading” that does not need a response. An exclamation as much to the self as to the imagined listener. Perhaps they are rather toothless in terms of their ability to persuade other citizens—the slightly misinformed referencing of scientific articles is arguably more dangerous for the DHA's agenda.

Many emotional engagements appeared in isolation, a kind of “hit and run.” As discussed above, the DHA often responded in an incongruent way to highly emotional posts. But citizens also often responded incongruously to what came before, or failed to respond to the answer they were given. This patterning became clear early on, and challenged our expectation that we would be analyzing dialogue—what we found was far more chaotic and fragmented. People seem to pass by, maybe respond, and then leave again. As noted earlier, the average citizen engaged 2.44 times over the course of the 7-month period, supporting the impression that extended and repeated dialogue from individuals was not occurring. Citizens thus seem to be using the engagement function on the platform for either quick informational needs, or for emotional release.

Emotional off-loading can also significantly impact those working for social media platforms—especially when directed personally at them. At the moderators meeting, one of the students said “If I can be completely honest, then I have to say that it was really rough working on the Facebook platform, that there was so much hate, and yeah citizens can be personal and we sign the replies with our name.” Here again we see a tension between wanting to explain and defend one's position—whether as an individual or an institution—and the feeling that it will do little good. A sense of fragmentation and disconnect infused the material we analyzed, but along with a feeling that this was the “price to pay” for the symbolic value of a dialogical platform and the undoubtedly huge reach it offered for what was ultimately rather restricted and traditional dissemination and Q&A formats.

We will begin this Discussion by summarizing key findings, contextualized in our discussions with DHA staff. We will discuss how this relates to classic models of expert-citizen relationships in the science communication literature, and how a more critical perspective on the assumptions behind these models reveals a perspective-dependent understanding of when dialogue occurs and to what purposes. A vignette from the end of our study period—as citizen engagements shifted toward the topic of vaccination—will be used to raise questions about the conditions necessary for dialogue. We conclude by reflecting back on the value of research-in-practice.

In the theme Seeking Information and Justification we saw the most straightforward fulfillment of the DHA's desire to come closer to citizens while still retaining their expert role—citizens asked questions about face masks that the DHA felt were in their remit to answer. In this sense, the Facebook page provided a fast, personalized Q&A—requiring greater resources than a regularly updated FAQ page. However, not all citizen questions were clear in their motive; rhetorical or sarcastic “pseudo-questions” were also common, and layered together requests for information, expressions of frustration, and/or commentary on the DHA. Whether this counts as top-down dissemination or bottom-up citizen engagement depends on what the object of communication is, and which outcome is of interest. From the perspective of communicating information about COVID-19, the engagements were classic dissemination, if often failing to answer more difficult questions. But from the perspective of understanding what citizens want to know, the engagements were a source of learning for the DHA. The answer catalogue was adjusted in the light of popular questions, and the moderators learned about effective replies from observing citizen reactions. As discussed in the Introduction, traditional models of science communication that focus almost exclusively on whether knowledge is transferred can miss these kinds of nuance—seeing communication as also about needs, desires, and identity excavates new perspectives.

The theme Giving feedback and lacking response captured a large group of citizen engagements giving feedback on the DHA's posts—not just asking for information, nor providing their own new content, but evaluating the DHA's actions. In practice these three categories often overlapped—a question can be used to pass judgment, and an evaluation can be used to share new information. The negative evaluations—and we must remember that positive evaluations often go unmarked on social media and thus recede from view—were often focused on the changing nature of advice; the instability of the DHA's expert knowledge base. This was to some degree inevitable in a pandemic, where scientific knowledge was changing fast and where negotiations between research, health institutions and authorities, and government played out live and more “in public” than ever before.

The last decade of science communication scholarship has highlighted the need to communicate science in process; to build trust via transparency and increasing literacy about the way scientific knowledge evolves (Arjini, 2020; Petersen et al., 2021). Our case study emphasizes both the need for transparency (any sense of hidden interests or hiding new knowledge was angrily derided) but also its difficulties. While recent research suggests that playing out the development of guidelines live in Denmark increased public trust on a general level (see Petersen et al., 2021), it led to many critical questions on the DHA Facebook page. One frustration for the DHA moderators was that they were not permitted to comment on “political” questions, but many of citizens' enquiries concerned science-politics-institutional hybrids. Face masks is a case par excellence of this kind of hybridity—no-one could prove quickly enough exactly what effects different masking practices would have in different contexts, yet decisions still had to be made that took into account social, economic, and political factors. Negative citizen feedback was often unfair or misplaced—but the DHA was not always free to explain why this was the case. Thus, “bad behavior” revealed cracks in the foundations that would be necessary for dialogue about the “real” matters at hand. As mentioned in the Introduction, this echoes arguments by other science communication scholars that we should treat bad behavior as a valuable source of information about the structures that shape what purposes communication (can) serve for the various actors involved (e.g., Horst and Michael, 2011; Davies and Horst, 2016; Davies, 2019).

When sarcastic questions were posed, or negative judgments about the political role of the DHA were made, moderators sometimes gave a standard answer to whichever common question best approximated the theme of the citizen's feedback. This reads strangely—a kind of “non-response” that seems to refuse the reciprocity Grudin's (1996) insists is part of dialogue. Yet the very incongruity of these exchanges also generates a kind of “strangeness” that could perhaps be read as an affective dialogue. A shock of emotion followed by the refusal of the DHA to become emotional, which may not transmit any information, but arguably communicates something about what is meaningful and possible for both parties.

In the section Giving Information and Claiming Expertise we enter the more classical territory of reciprocal dialogue—citizens share their own knowledge, and on matters and in modes that challenge the authority of the DHA. They do not just gently “fill in the gaps” in how policy translates into real-world contexts, but challenge the meaning of those contexts for policy itself. Or they intervene with contradictory theories, references, and sources of information about matters of policy such as the wearing of face masks. Citizens position themselves, their friends or colleagues as holding competing expertise, and give links and references to a huge diversity of sources. Conspiracy theories and misinformation are also posted, and often allowed to remain—though we speculate that this is perhaps less concerning in relation to the DHA's goals than the more “reasonable” posts of unverified or decontextualized scientific findings or expert testimony. This section also reminds us that it is as much citizens as authorities who can shut down “strange and reciprocal” dialogue—and both DHA leaders and moderators were very clear about the limitations of social media persuasion with certain groups of citizens. As one of the leaders said when talking about vaccinations, “there is a tiny group, where the reality is that they opt out—they are totally against it,” and another commented that these citizens “are completely convinced that we are all sheep.”

The DHA seeks with its Facebook page to provide an authoritative and trustworthy source of information—as soon as citizens start sharing unvetted scientific articles and other expert sources, the stability of this position is thrown into doubt. But what should the DHA do? The DHA cannot disrespect citizen's positions if they wish to give the appearance of dialogical openness. It would also bring additional practical challenges if moderators had to make more “grey area” judgments—as Facebook has discovered repeatedly in recent years. In discussing this aspect of the findings with DHA leaders and moderators, we were again reminded of the silent majority who do not argue with what is presented, but simply absorb the DHA posts and ignore the noise of other citizen engagements. Indeed, some of their informational posts reached a third of all Danish citizens. Is the anarchic bubbling in the comment thread, then, a reasonable price to pay for the wide reach of the Facebook page, boosted by its appearance of proximity to citizens and offer of a rapid Q&A function?

In the last Analysis section Emotional Off-Loading in Broken Dialogical Chains, we tied some threads together across the different patterns of engagement. Engagements were often highly emotive, as expected on social media and around a controversial topic. As discussed above, the negative engagements visible on the page are a slim slice of the total usage—most people are invisible and simply take what they need. But the negative engagements take up a disproportionate amount of the “public space” of the page and indeed of the time of the communication staff. What we discovered was that—at least during the period we studied—even these negative engagements appeared to be primarily “hit and run.” People burst into a comment thread, off-load, and leave again. Here a dialogue is not unfolding between the individual and the DHA, though weakened, second-hand exchange is arguably occurring as others read the threads and as the DHA constructs future responses influenced by the “improper engagement” of these individuals.

This theme of the individual citizen vs. an implied citizen group is one we would like to draw out in these concluding reflections. The DHA wishes to come closer to citizens in the plural, via an engagement with individuals—not to engage directly in the unique individual concerns of lived experience, which inevitably drag along undisciplined knowledge and context that muddy the waters of generalized guidance. On the Facebook page this was seen when individual “bad behavior” was met by a generic group response—an arguably paternalistic strategy, but not necessarily a bad one. The DHA's Facebook policy is intentionally structured around limiting personal engagement; the page is rather a portal for general information and redirection to individualized services. The strangeness this creates on a supposedly dialogical platform like Facebook is jarring to observe—especially from our perspective as researchers—and was stressful for many of the moderators, but is not necessarily jarring for citizens. We speculate that emotional off-loading may perform an important affective function for the citizen and other readers of their comments. Further research could delve into the ways in which silent users, emotional off-loaders, and other engagers experience such phenomena.

The image we think we are building up here is one of a compromise; a balance between appearance and reality to satisfy underlying motives; and a displacement of dialogue from individually open minds onto representative entities and into a more affective than cognitive register. There is plenty of strangeness here—and plenty of learning by the DHA about the citizens they engage. However, we would argue that in straightforward terms, what is desired is not really dialogue about COVID-19, and the desire to get closer to citizens is a one-way mirror—the DHA is not able or willing to be “known” in the open and vulnerable manner that they hope citizens' interests can be known. We see this analysis as an example of what happens when we attend to science communication not just in terms of explicit exchanges of knowledge, but also attempt to “dissassemble” the multiple actors involved—and how these actors imagine themselves and each other (see Davies, 2019; Edwards and Ziegler, 2022).

In the case of face masks, the balance between opening up for citizen engagement and opening the floodgates to misinformation seemed to hold—a lot of citizens got timely, accurate information; were reassured; were able to make contact and feel seen. The misinformation-in-process unfolding on the Facebook page was judged by the DHA staff to be manageable; “hit and run” engagements likely ignored by most. However, when the dominant issue shifted to vaccination, things changed. This lay outside the period of our empirical analysis, but was a strong theme in our meetings with the DHA at the end of the project. With the advent of vaccination programs, trolls appeared—more determined, more repetitive and persistent, less open to engagement than the earlier emotional citizens. The DHA staff described their appearance of being highly coordinated, of using the Facebook page opportunistically as part of a wider campaign, rather than engaging with it as a specific authority. As one of the moderators noted; “There have been critics on the facebook page the whole time. In the beginning the subject was the reopening of schools, the mothers ‘went' on us, then there were the face masks and now it is the anti vaxxers. The anti vaxxers take a lot of space and are well-organized.” And as another described; “there are no real questions anymore, I feel it's more just… angry, sour people.”

In this challenging situation, the moderators were restricted in their responses, and had to make repeated judgment calls. They could hide links they considered misleading, but could not delete posts unless they were intolerably insulting. These tools are also used sparingly, as users noticing that comments have been deleted or hidden can damage the appearance of transparency. When we discussed with the leaders and moderators what should be done if this continued, opinion was split—some favored just shutting down the comment thread—one moderator said “I think the idea is good, to enter dialogue with the citizens, but not the way it is now.” Whilst others saw the comment thread as essential to the identity of a Facebook page—for example one of the leaders said “I think that social media is about dialogue and I would never recommend turning off a comment option.”

For our purposes, what this anecdote highlights is the crucial importance of context for judging the appropriateness and even the possibility of dialogue for health authorities on social media. It is not just the DHA who is responsible for whether dialogue occurs; citizens can also facilitate or close down reciprocity and strangeness. In the face mask period, both DHA and citizens refused the rules of reciprocal dialogue in various ways, but this still allowed many of the goals of engagement to be met. In the vaccine trolling period, the “refusal” was harder and more disconnected, and the fear was that this would swamp the silent masses' ability to continue to use the page as intended. Our discussions with DHA staff about this again highlighted the difficulty of dealing with political matters—face masks and lockdown were in a period of greater emergency, and decisions were seen by the DHA staff as more evidence led, whilst reopening and vaccination were seen as more politically-inflected. It seems that when institutions are more separated (and sedimented) in their roles, it is easier for them to communicate about controversial topics. But we would argue that even in the calmer period, a key citizen concern was exactly the relation between institutions, and that communicating about these relations is critical to the flourishing of dialogue about the decisions institutions wish to explain and defend.

In the last 2 years there has been intense research focus on all aspects of COVID-19 including its public communication, already resulting in journal special issues such as this one and, e.g., Massarani et al. (2020a,b) and Nan and Thompson (2021) and an edited volume by Lewis et al. (2021). This study aims to contribute to this expanding field by providing an in-depth, qualitative analysis of what actually occurs when health authorities pursue laudable aims of opening up dialogue with citizens who desire it. Our analysis does not deliver advice on which communication strategies to deploy on Facebook, but instead aims to illustrate the importance of asking questions about the complex configurations of purpose, need, constraint, and identity that characterize dialogical communication between citizens and authorities.

This project was an example of a close relation between science communication research and practice, grounded in FM's dual role as DHA moderator and University researcher, and the relationship-building and formative feedback this allowed. Being able to share our evolving findings and questions about how they relate to DHA strategy has grounded our analysis in context, and helped to expand our attention from the nitty gritty of Facebook engagements to the invisible users, other platforms, and wider communicative contexts in which they occur (Davies, 2019). It also heightened our understanding of the dilemmas faced by health authorities in communicating about COVID-19 and in making compromises inevitable when these expert positions enter dialogical, individually-driven social media platforms.

By situating this research/practice relation in a specific DHA project, we saw by contrast the lack of resources usually available for drawing on science communication research. Moderators get minimal training, and are not instructed through academic research; staff of all levels of seniority were interested in research, but did not have working hours to engage with it. Decisions were made based on the expertise of experience, but missteps were made that could perhaps have been diverted within a research-based frame. In emergency situations, it is unclear whether slower, research-based communication design would be more efficient and effective than a more intuitively led process with running correction. But in general, we think our case shows some of the virtues of embedding research processes within the development of new science and health communication projects. The movement for evidence-based science communication (e.g., Jensen and Gerber, 2020) makes important calls for more generalizable, rigorous and experimental knowledge about the impacts of particular communication strategies. Inspired by a more STS-informed approach to science communication, we would like to add to the list of desired outcomes a focus on embedding qualitative research within local, situated case studies.

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the raw data consists of Facebook posts and citizen engagements on the Danish Health Authority's Facebook page, as part of the HOPE project (see manuscript). The current agreement does not allow for general sharing of this data, which is very hard to anonymise and contains sensitive information, but future collaborative agreements may be entered into that involve sharing of the data. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to RA-N, cmFuQGlmcy5rdS5kaw==.

FM conceived the original idea, the authors together developed methods. FM collected the data and carried out the qualitative analysis with input from LW, MA, and RA-N. NJ prepared the data and carried out the quantitative analysis. FM, NJ, MA, and RA-N performed the interview with the Danish Health Authority. FM and NJ performed the interview with the Danish Health Authority's Facebook Moderators. FM drafted the methods and analysis, LW drafted the introduction and discussion and finalized the manuscript. NJ, MA, and RA-N contributed to the editing of the manuscript. FM and NJ constructed figures. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Our research has been specifically supported by the Carlsberg Foundation, Grant Number CF20-0044 (HOPE—How Democracies Cope with Covid-19). LW was also supported by the Novo Nordisk Foundation for Center Basic Metabolic Research (CBMR), an independent research center at the University of Copenhagen partially funded by an unrestricted donation from the Novo Nordisk Foundation (NNF18CC0034900).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

A special thanks to the Danish Health Authority for providing their Facebook data for our research, and for participating in our presentations and interview meetings with generosity and openness despite the extreme pressures on their time, and reading the manuscript prior to submission.

1. ^We use “citizens” to refer to people posting on the DHA's Facebook page—instead of the more typical, consumer-oriented “users.” This is in order to reflect the DHA's language and how the health authority imagines its relations with those they engage on social media. Note it does not imply that all those engaging with the Facebook page are legally Danish citizens.

Allington, D., Duffy, B., Wessely, S., Dhavan, N., and Rubin, J. (2021). Health-protective behaviour, social media usage and conspiracy belief during the COVID-19 public health emergency. Psychol. Med. 51, 1763–1769. doi: 10.1017/S003329172000224X

Andersen, K. N., Medaglia, R., and Henriksen, H. Z. (2012). Social media in public health care: impact domain propositions. Gov. Inf. Q. 29, 462–469. doi: 10.1016/j.giq.2012.07.004

Arceneaux, K., Gravelle, T. B., Osmundsen, M., Petersen, M. B., Reifler, J., and Scotto, T. J. (2021). Some people just want to watch the world burn: the prevalence, psychology and politics of the ‘Need for Chaos'. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 376, 37620200147. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2021.0064

Arjini, N. (2020). Science will not come on a white horse with a solution. Interview with Sheila Jasanoff. The Nation. Available online at: https://www.thenation.com/article/society/sheila-jasanoff-interview-coronavirus/

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Bucchi, M. (2017). Credibility, expertise and the challenges of science communication 2.0. Public Understanding Sci. 26, 890–893. doi: 10.1177/0963662517733368

Bucchi, M., and Trench, B. (2008). “Of deficits, deviations and dialogues,” in Handbook of Public Communication of Science and Technology, eds M. Bucchi and B. Trench (Oxon: Routledge), 57–76.

Canel, M., and Luoma-aho, V. (2019). Public Sector Communication. Closing Gaps Between Citizens and Public Organizations. New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons.

Chadwick, A., Kaiser, J., Vaccari, C., Freeman, D., Lambe, S., Loe, B. S., et al. (2021). Online social endorsement and Covid-19 vaccine hesitancy in the United Kingdom. Soc. Media Soc. 7, 20563051211008817. doi: 10.1177/20563051211008817