- University of Catania, Catania, Italy

In the translation into sign language, where does the ≪sense≫ reside and how can it be constructed in the target language? To what extent does the orality of sign languages, intended as the absence of a writing system, affect the translation process? What role do the characteristics of sign languages, first and foremost iconicity, play? The issues we address in this study are placed at the crossroads between sign language linguistics and translation studies, thanks to the awareness that both disciplines have, respectively matured in recent decades. As regards the linguistics of sign languages, we refer to the semiological model proposed by Cuxac and colleagues. On the subject of translation studies, our main reference is represented by Meschonnic, according to whom the sense is found in the ≪rhythm≫ (understood as form). Analyzing the translation process, and more specifically the poetic translation, allows us to observe the centrality of the body. We take into account the perspective of embodied cognition, based on the link between the language and the sensorimotor system. Therefore, we question the role of the body in the construction of the sense: the body is considered above all in its sensorial dimension, in its being an entity that perceives and enters into a relationship with the world. That makes us hypothesize a synesthetic construction of the sense. In order to follow in practice what is stated theorically, we present one of our translations: the translation into LIS of a poem in Italian, L'Infinito by Giacomo Leopardi. The translation into sign language makes it possible to observe the role of corporeality in the process of re-enunciation of sense.

Introduction

It is commonly said that the title constitutes the most extreme summary of a text. We would therefore like to begin our reflection starting from the title, or rather from the first part of the title: translating poetry in sign language. Taking into account that poetry, or more precisely a well-known Italian poem, is our reference corpus, we would like to focus on “translating” and “sign language.” They both have begun to be perceived as disciplines only in recent decades. As we know, about 60 years have passed since the publication of William Stokoe's Sign Language Structure, the publication which, for the first time in 1960, proposed an analysis of sign language as a real language. As regards the theme of translating, we can say that, although the phenomenon has existed for millennia1, the birth of translation studies as a discipline can be placed between the end of the 70's and the beginning of the 80's (cf. Lavieri, 2016a2). Consequently, the ontological dialogue between these two disciplines is recent.

The encounter between linguistics of sign languages and translation studies was also due to the growing awareness of the existence of literature in sign language. Characteristics of the signed literature (and, more specifically, of the signed poetry) can be found in the best-known international scientific literature on the subject (Miles, 1976; Klima and Bellugi, 1979; Valli, 1993; Mirzoeff, 1995; Ormsby, 1995; Cohn, 1999; Peters, 2000; Sutton-Spence, 2005; Bauman et al., 2006; Sutton-Spence and Kaneko, 2016) and, as much as concerns the Italian context, in the studies concerning LIS (Italian Sign Language) (Russo Cardona et al., 2001; Russo Cardona, 2004; Rizzi, 2009). Works that deal with the poetic translation of sign languages (Celo, 2009; Catteau and Blondel, 2016; Chateauvert, 2016; Fontana, 2016; Pollitt, 2019; Houwenaghel and Risler, 2020; Raniolo, 2021), both theoretically and practically, have quite recently appeared.

One of the aspects that characterizes signed literature is represented by orality: the reason lies in the fact that sign languages are oral languages, that is, they do not have a written form shared by the communities of signers4. The oral nature of sign languages affects above all the process of language standardization: for this reason, sign languages present many diatopic variants (regarding LIS, cf. Volterra et al., 2019). Furthermore, the question of tools must also be taken into account. The dictionary, which is usually an ally for those who work in the field of translation or languages in general, is only partially useful in the context of sign languages. For a translator/interpreter it is rather necessary to start from a pragmatic and social dimension: the primary resource is represented by the users of the language, who are the only custodians of the social fact (Fontana, 2013).

We also specify that the use of the term translator / interpreter is due to the oral nature of sign languages. The choice of talking about a single figure may seem somewhat unusual, since the two professions are commonly distinct. Actually, these professions differ in a number of aspects5, which can be summarized in the fact that the translator works with written texts and has a (relatively) long time available, while the interpreter works with oral texts in real time. It is precisely because of the absence of written form in sign languages that the professional who works with sign language can be defined as a translator / interpreter (cf. Buonomo and Celo, 2010; Celo, 2015): the central point is in fact that “the translation process takes place exclusively on the level of orality” (Fontana, 2013, p. 68, our translation)6. This peculiarity strongly affects the translation process (Fontana, 2013, 2014).

The work of the translator / interpreter, in addition to what has been stated, must take into account another characteristics that, in our opinion, proves to be fundamental. We are talking about the relationship with the public: not only a deaf public, but also a hearing public (not necessarily proficient in sign language), that, even if unable to grasp the nuances of the language, can still enjoy the poetic translation. In fact, one of the features that characterizes the figure of sign language translator / interpreter is its physical presence, a presence that gives life to a performance that is appreciable, as we will see, even by those who do not have specific linguistic skills. For the sake of clarity, we propose a comparison. With regard to vocal languages, in most cases the translators do not show themselves at all (we only see the finished product in its written form), interpreters only give access to their voice. In the case of the sign language translator / interpreter, his physical presence is a sine qua non for the translation process to be fulfilled. Let's consider the case of conference interpreting: the LIS interpreter is “placed in a high position and clearly visible from the whole audience” (Franchi and Maragna, 2013, p. 138, our translation). The reason lies in the fact that sign languages exploit the visual-gestural channel, therefore it is essential that the person who signs is clearly visible. The possibility of being perfectly seen is a fundamental characteristic, which assumes a central role in a reflection on translation such as the one we intend to conduct here.

With the aim of investigating the work of the translator / interpreter, we propose an interdisciplinary study7 that has as its reference frames the linguistics of sign languages, poetics and translation studies, and finally the theme of movement and scene. In the next paragraphs we will therefore present the key points of our reference background; subsequently we will converge toward an embodied approach and present our theoretical proposal associated with the practical translation of one poem.

Subsections Relevant for the Subject

Linguistics of Sign Languages

As regards the study of sign languages, we refer to the modèle sémiologique (semiological model) developed by Christian Cuxac (2000) and perfected over the years by his team. This model is structured taking into account above all the centrality of iconicity in the sign languages: according to this model, the so-called Structures de Grande Iconicité (highly iconic structures) have the potential not only to dire (to say) but also to montrer (to show)8. Through iconicity, these structures allow perceptive experiences, be they real or imagined, to be transposed into linguistic expression. In this process, the central role belongs to the body and to all its components that are involved in linguistic utterance (not only the hands, but also the direction of the gaze, the facial expressions, etc.)9. Sallandre (2010) noted that it is possible to identify a “va-et-vient” (come and go) of iconicity, that is an alternation, often rapid, of highly iconic structures, standard signs and linguistic structures in general. In this context we will not present all the specific characteristics of sign languages in detail, but in relation to the LIS (Italian Sign Language), that is the sign language that we take into consideration here, we suggest consulting Volterra et al. (2019).

Poetics and Translation Studies

With regard to poetics and translation studies, within this work we take as a reference the “poetics of rhythm” proposed by Meschonnic (1982a). The French scholar, starting from Benveniste's reflection (1996), takes up the original notion of rhythm understood as form10. According to Meschonnic, rhythm is the organization of the marks that allow the creation of a specific semantics, defined as signifiance (significance); these marks are located at all linguistic levels (not only lexicon, but also prosody, accentuation, syntax). Rhythm is the characterizing feature of each discours (discourse), it represents the element that gives it unity: consequently, it occupies a central place. It should also be noted that Meschonnic attaches considerable importance to subjectivity, stating that “le rythme est l'organisation du sujet comme discours dans et par son discours” (rhythm is the organization of the subject as discourse in and by his discourse, our translation) (Meschonnic, 1982a, p. 217). We could summarize Meschonnic's thought by saying that, according to the French scholar, sense lives in rhythm: this represents a real revolution in the idea of “sense,”of what makes sense. The author therefore considers how the new form is created in the translation process, how the sense is re-constructed (Meschonnic, 1999).

Closely related to the concept of rhythm is the question of orality. As claimed by Meschonnic (1982a,b), the concept of orality does not coincide with that of spoken, although this idea is widespread. According to him, orality goes beyond simple opposition to writing: even in the presence of writing it is possible to identify an orality, a rhythm, which allows to make sense.

Meschonnic's thought, which we have tried to present briefly here, constitutes the presupposition from which we intend to investigate how sense is constructed, how sense is re-enunciated in another language, in this specific case in a sign language.

Movement and Scene

We have mentioned that a translation can also be seen by people who do not know sign language: actually, the translation not only is accessible to a deaf audience, but also becomes enjoyable by a non-signing hearing audience. In fact, “Living a body that acts in the world becomes an identity paradigm that unites signers and non-signers and which allows a participation that goes beyond the knowledge of sign language” (Fontana, 2016, p. 134, our translation). The key is the body that generates movement, the body that acts on the scene. For this reason, we would like to introduce some considerations concerning these issues, framing them within a reflection on performance. First of all, we can consider poetry in sign language as performance by reason of its orality. Indeed, as the well-known scholar Ruth Finnegan (1977) states, for oral civilizations, the concept of text cannot be separated from that of performance. Furthermore, the use of the body as a primary means of expression in sign languages leads to a comparison with the theater, which once again takes up the idea of performance. Anyone who is involved in translating into a sign language, for pleasure or under professional circumstances, knows well that it is necessary to “go on stage.” Of course, there are cases in which we can speak of a real stage (for instance, interpreting / translating deaf actors during a theatrical performance), but leaving out the artistic contexts proper, the scene is systematically present both in interpreting and in translation, it is an integral part of it: by entering the visual field, it helps to create sense.

Discussion

Toward an Embodied Perspective

Sutton-Spence and de Quadros wrote in 2014 an essay dedicated to the vision that sign language poets have of poetry, with a very eloquent title: “I am the book”11. Becoming what is translated: the translator / interpreter is required to have his own body become the text to be translated. In other words, his role is to “embody” the translated / interpreted content. The body plays a key role in sign language translation, for several reasons. We have already referred to the visual-gestural nature of sign languages: they are produced with the body and grasped through the sense of sight. The very first studies on sign languages have emphasized the importance of the body: even the first ever, Stokoe's (1960), had placed attention on the body within the communicative process in sign language. The studies that have followed over the years have continued to emphasize the importance of the body, in an increasingly conscious way. We could quote Paul Jouison, who speaks of “configurations corporelles” (body configurations, our translation) (Jouison, 1995, p. 146) underlining their iconic value, or even Christian Cuxac, who hypothesizes a “processus d'iconicisation de l'expérience perceptivo-pratique” (process of iconicization of the perceptual-practical experience, our translation) (Cuxac, 2000, p. 27).

Let's start from Cuxac's words concerning perceptual experience to also remember that the body represents the seat of the senses: we would like to focus on this, taking into account the “embodied” perspective.

The perspective of embodied cognition, to which we intend to refer, is centered on the body, on possessing a body that acts in the world. The concept of embodiment presupposes the link between language and the sensorimotor system, the idea that the body entering into interaction with the environment and manipulating it is at the origin of human cognition. It is interesting to consider the potential of embodied simulation (Gallese and Sinigaglia, 2011): thanks to mirror neurons, the activation of neural circuits correlated to actions and perceptions occurs even when these are not experienced personally, but by others.

Starting from an embodied perspective means reflecting on language considering that it is linked to the physical characteristics of the human being: for example, the mind “is conditioned by the physical dimensions of the brain, and, secondly, by the body dimension in general and by the structure and the laws of the surrounding world (for example by the force of gravity)” (Gaeta and Luraghi, 2003, p. 22, our translation). Therefore, language is not an autonomous cognitive capacity, but is part of a network of capacities: it is precisely to the embodied perspective that we owe the idea of continuum between action, gesture, sign and word (Volterra et al., 2019). Although the embodied dimension belongs to both sign languages and vocal languages (Blondel, 2020), embodied cognition is a very suitable approach to describe sign languages, since they are languages centered right on the body. Moreover, this approach takes into consideration the body and its senses, therefore it allows us to focus on the senses with which deaf people perceive the world, an aspect that is naturally reflected in their language.

In our opinion, considering the relationship between sensoriality and corporeality cannot ignore a philosophical perspective. According to philosophy, or to be more specific according to phenomenology, there is a distinction between Körper and Leib: the first is the anatomical body, while the second is the living body. For the purposes of our reflection, we are not interested in the body from an anatomical point of view, but rather we focus on the Leib, on the body that lives in the world and interacts with it, changing the world and changing itself. The embodied perspective seems to have a precursor in Maurice Merleau-Ponty, a French phenomenological philosopher. He recognizes the primacy of perception and affirms that it must be acquired, since it derives from the interaction between the organism and the surrounding environment: thanks to his own senses, the human being comes into contact with the world (Merleau-Ponty, 1945). His thought is particularly interesting because it starts from the assumption that being in the world is not separable from being flesh. The scholar also emphasizes the centrality of synaesthesia, which he believes to be systematically present in the perceptual process.

Given that different senses are involved in the translation process from a vocal language into a sign language and vice versa, we believe that synaesthesia, understood as the association of perceptions deriving from distinct senses, plays a pivotal role. Similarly to Chateauvert (2016), who in the context of sign language translation defines synaesthesia as a series of intertwined moments that aesthetically overlap, we elaborate a theoretical proposal centered precisely on the role of synaesthesia in poetic translation involving a sign language12.

Poetic Translation: A Sensory Experience

The translation process to and from sign language is characterized by a mixture of sensory perceptions: this consideration leads us to the idea that the translation itself can be considered a synaesthetic process, built in close connection with corporeality.

Let us consider the concept of signifiance and the definition that Meschonnic gives to it, previously explained. In the attempt to ask ourselves how signifiance is re-enunciated in the passage from a vocal language to a sign language and vice versa, we notice the influence that the dialogue between the senses has. In our opinion, in this specific context signifiance itself has a synaesthetic nature: the sensory level, although it is not a linguistic level, affects the linguistic process and shapes it. In translation, signifiance is therefore reconstructed within what we can consider as a sensorial encounter: orality is redefined and finds new lymph in a new sensorial form, the senses meet and create sense. The translation thus makes it possible to re-enunciate the rhythm itself within the framework of a different sensorial perception, giving life to what we have defined as synesthetic construction of sense.

Referring once again to Meschonnic (1982a), we can see that the scholar dwells on the relationship between body and language. He reflects on the presence of corporeality in different types of language and affirms that the body lives in language in relation to the role that rhythm plays in it: starting therefore from the identification of a link between bodily involvement and rhythm, he argues that poetic language is the most corporeal. About the specific case of sign languages, we would like to ask ourselves: can poetry be considered more corporeal than other uses of the language? Russo Cardona (2004) identifies a correlation between textual typology and iconicity: he believes that the iconic productive structures, characterized by “dynamic iconicity,” are present mainly in poetry, while they are far less present, for example, in conferences13. This leads him to confirm his hypothesis concerning the presence of a relationship between “iconic stratifications” and different uses of language. Given that the iconic potential of the language is linked to the context of use, we believe that the iconic stratifications, the more or less frequent use of iconicity (related to corporeality, as argued by Jouison and Cuxac), can make it possible to identify greater or lesser bodily involvement. And it is precisely this bodily involvement that, in the manner of Meschonnic, we want to understand as rhythm, as sense.

With this in mind, poetry represents the ideal corpus to elaborate our reflections, since it can be considered a triumph of corporeality and iconicity. We therefore think that, in the case of poetic translation in particular, it appears necessary to give life to a discours constructed largely on iconic-corporeal aspects: these aspects are identifiable in the Structures de Grande Iconicité. Aiming at a full bodily involvement, not only it is possible to obtain a poem close in strategies to the original poetic productions in sign language, but it is also possible to give a central role to the body, which becomes the architect of the form-sense.

We would like to dwell once more on the figure of the translator / interpreter. As previously said, Meschonnic believes that subjectivity has great importance: the elements proper to the sujet (subject) play a key role in the organization of rhythm. In case the subject is a sign language translator / interpreter, his task is to embody the contents and create the sense starting from his own body. To fulfill his task, the translator / interpreter goes on stage, generates what we can consider a real performance. Giving considerable importance to subjectivity, and to the translator / interpreter as a sujet, means giving a place of honor to the translator who enters in his translation, or more generally in the scene, carrying all of himself. A theatrical self goes to the stage: the translator lives in the individual, but the translation lives in the body. When I am the book, to take up the title of Sutton-Spence and de Quadros (2014) previously mentioned, the awareness that, despite the central role of subjectivity, the self is not on stage as self, but as a translating body, as a body that builds the translation, is essential.

The translator / interpreter can produce his translation in recorded form or in person; in any case his physicality is included and in any case the translation is oral. We agree with Crasborn (2006), who affirms that, considering that sign languages do not have a writing system commonly used by deaf people, poems in sign language, both presented face to face and recorded, are always performances. We share the idea of a translation that privileges “the parameters of the recitability of sense, of its performativity” (Lavieri, 2016b, p. 29, our translation).

Another aspect that we should consider is that, just like performances, the translation, even if it is defined, is not fixed once and for all: since it is oral, every time it is produced, it is not the same as the previous time. Furthermore, especially in the case of translating a poem in presence, a new relationship is established each time with the audience. Regarding the relationship with the public, we would like to consider the thought of the well-known French playwright Artaud (1964)14: for him it was a priority that the spectator had the opportunity to 'enter the scene', thanks to an emotional sharing between the parties, a sharing through sight and hearing15. An intuition that, we could say today, has its foundation in mirror neurons, whose existence was not yet known at the time. Therefore, starting from the idea of a new ένέργεια (energy) that lives in the relationship between actor and spectator, we can say that translating into signs means creating a performance whose sense is corporeal energy. In fact, corporeal translation cannot ignore a bodily dialogue that is built with the spectator: a dialogue with an interlocutor who, whether physically present or only supposed, has a corporeality that in any case becomes presence. When we refer to the link between sense and corporeality, we think that it is appropriate to consider not single bodies, but several bodies in interrelation with each other: taking into account the thought of Artaud, we believe that we can speak of co-construction of sense.

A Practical Example of Poetic Translation

Meschonnic's wish is not to split the théorie-pratique union, in the awareness that one is indispensable to the other. Considering his teachings, in this paragraph we put into practice what we have expounded on a theoretical level: we translate one of the best-known poems of Italian literature, L'Infinito by Giacomo Leopardi (composed between 1818 and 1819).

Sempre caro mi fu quest'ermo colle,

E questa siepe, che da tanta parte

Dell'ultimo orizzonte il guardo esclude.

Ma sedendo e mirando, interminati

Spazi di là da quella, e sovrumani

Silenzi, e profondissima quiete

Io nel pensier mi fingo; ove per poco

Il cor non si spaura. E come il vento

Odo stormir tra queste piante, io quello

Infinito silenzio a questa voce

Vo comparando: e mi sovvien l'eterno,

E le morte stagioni, e la presente

E viva, e il suon di lei. Così tra questa

Immensità s'annega il pensier mio:

E il naufragar m'è dolce in questo mare16.

We propose our translation in LIS, which is available online17. First of all, we note the sensory perceptions that characterize the poem: in the first part the prevailing sense is sight, the sensation of seeing, or rather of not seeing (impossibility of seeing beyond the hedge), while in the second part the auditory sensations prevail18. How can these sensory perceptions be translated? Let us begin our reflection by considering the double nature of infinity, which is both spatial and temporal.

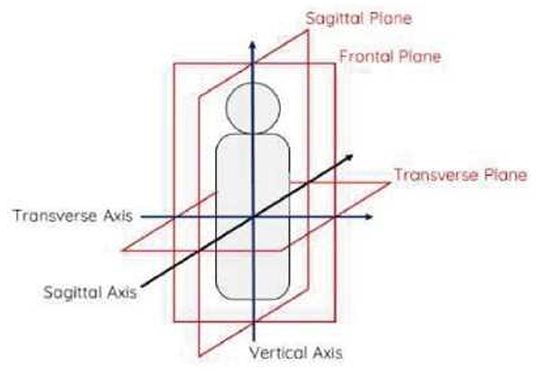

As regards the time line, we would like to emphasize that in LIS temporality is expressed along the sagittal axis: the past is behind, the future is ahead. This structure, whose nature is metaphorical, cannot be considered a characteristic of sign languages in a broad sense since in other sign languages it varies [cf. Taub, 2001]. Having considered this, we have come to the hypothesis that the idea of infinity could be re-enunciated in sign language by taking up the axes by convention linked to a certain concept and going beyond them, even toward unusual axes. Consequently we have decided to create the “rhythm” of infinity (spatial infinity as much as temporal infinity) through the use of both the sagittal axis and the transverse axis (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Body planes (sagittal, frontal, and transverse) and axes (sagittal, vertical, and transverse)3.

By doing so, however, we obtained a result that is in line with what (Sutton-Spence, 2010) observes about the frequent use of the transverse axis in poetry, due to the embodied nature of sense. Sutton-Spence notes that the transverse axis is used above all to create symmetries: in our translation there are signs made on the transverse axis in a symmetrical, but also asymmetrical, way. We believe that the introduction of the transverse axis appears to have been inserted harmoniously: it is a harmony that arises precisely from a rhythm that is in line with the body, with the embodied nature of sense.

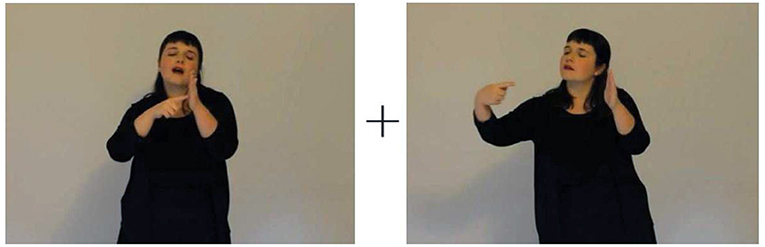

We would also like to reflect on the strategies adopted to achieve what we have defined as the synesthetic construction of sense. While sight, being an intact sense in deaf people, did not require any specific adaptation, the question of hearing is different. The part dedicated to auditory perception begins with “E come il vento / Odo stormir tra queste piante” (“And when I hear / the wind stir in these branches”): the poet's attention is attracted by the sound of the wind in the trees. We kept the idea of the wind in the trees but we transformed it into an image, a scene that the poet turns to look at (through the use of transfert, to use Cuxac's terminology). The combination of movement of turning and sign GUARDARE (to look) places emphasis on the permanence of visual perception: that allows to translate the conjunction E (And) found at the beginning of the line (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Our translation of “E come il vento // Odo stormir tra queste piante.” (“And when I hear / the wind stir in these branches”).

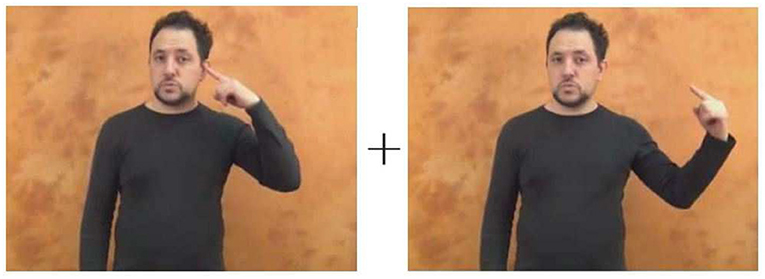

In the same way, when the poem mentions the sound of the present living season, with the words “e il suon di lei” (“and how it sounds”), we have used the sign SUONO (sound) with its movement that reproduces the waves but, instead of articulating it on the ear, we have articulated it on the hand. We resorted to a metaphorical strategy that exploits the variation of parameters (Sutton-Spence, 2005, Figures 3, 4).

Figure 3. SUONO (sound) – Spread The Sign Dictionary, 2022.

In doing so, we have kept the images and the rhythm, while letting them converge toward a sensoriality that is accessible to deaf people.

We believe that the strategies we have used also clarify what we mean by co-construction of sense. In person or through video, the recitation of the poem, and in particular the re-creation of the sense, can generate each time new sensations in the public: every member of the audience gives his own, personal interpretation, that enriches the sense and gives life to a co-constructed sense.

Conclusion

First we would like to emphasize that the analysis of translation processes clearly shows the pivotal role of the image, achieved in a particularly effective way by iconic structures with the potential of donner à voir (Cuxac, 2000). The realization of the image within the performative event is largely based on complex structures with a high level of iconicity, that are reproduced each time within the translation performance. Although, in the context of poetic translation, they are well-studied and predetermined, their rhythm is always new: it is a rhythm that can never be the previous one due to the oral nature of the sign languages.

The direct consequence of this centrality of the image created through the body is that the analysis of the translation processes also allows us to observe the role of the embodiment: it is precisely the body, whose relationship with the world determines the acquisition of perception (Merleau-Ponty, 1945), that plays a primary role in translation. The body constitutes the communicative channel in sign languages, but the same articulators deal with communication and daily actions (for example grasping an object). It follows that the link between language and sensorimotor system is strengthened, the language is sufficient to activate the areas that are neurologically responsible for perception and action, thus the mechanism of embodied simulation takes place (Gallese and Sinigaglia, 2011).

Our study allows us to observe that the centrality of the body in translation processes determines, as a direct consequence, the centrality of the senses. Translating poetry from a vocal language to a sign language (and vice versa) means starting from a discours thought to be received through a certain sensory modality and obtaining a discours thought to be perceived through another sensory modality. In our opinion, this passage generates a very specific encounter between the senses: the senses meet, the text has the potential to become such as to be 'heard' through sight, or to be 'seen' through hearing. Modifying the perceptual experience constitutes the strategy for constructing reflections based on the perceptual systems and the mechanisms of embodied cognition, with the aim of exploring the paths of sensoriality and observing how the senses cooperate, intertwine with each other, at the same time opposing and binding.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^The phenomenon of translating is very ancient, as evidenced by the archaeological finds in several languages: we can for example refer to the bilingual Lycian-Greek inscriptions dated 5th-4th century B.C.

2. ^Original edition 2007.

3. ^Image taken from Paredes et al. (2017).

4. ^We underline that, however, various systems of writing / transcription of sign languages have been proposed over time. We could mention Mimographie, Stokoe Notation, HamNoSys, D'Sign, and last but not least SignWriting, the one which to date is the most widespread system in research (cf. Antinoro Pizzuto et al., 2008; Garcia and Sallandre, 2013).

5. ^We propose to consider the distinction found in the Routledge Encyclopedia of Translation Studies edited by Mona Baker:

translators deal with written language and have time to polish their work, while interpreters deal with oral language and have no time to refine their output. The implications are:

- ≪translators≫ need to be familiar with the rules of written language and be competent writers in the target language; interpreters need to master the features of oral language and be good speakers, which includes using their voice effectively and developing a “microphone personality”;

- any supplementary knowledge, for example terminological or world knowledge, can be acquired during written translation but has to be acquired prior to interpreting;

- interpreters have to make decisions much faster than translators.

A subtler level of analysis of the skills required in translation and interpreting must await advances in psycholinguistics and cognitive psychology. Unlike translation, interpreting requires attention sharing and involves severe time constraints≫ (Baker, 1998, p. 41).

6. ^We specify that, even where we will not use the term in its double form, we always mean “translator / interpreter”.

7. ^For further information on our work, cf. Raniolo (2021).

8. ^In his 2000 volume, Cuxac identifies three types of transfert: transfert de taille et/ou de forme; transfert de situation; transfert de personne. Despite having different characteristics, they are all structures characterized by a high level of iconicity. Over time, further types of transfert have been identified (Sallandre, 2010).

9. ^We refer to this model because we believe it is particularly suitable for describing sign languages, precisely because it is structured starting from iconicity and centrality of the body, both aspects that prove to be fundamental in translation.

10. ^Émile Benveniste, in his 1951 essay entitled “La notion de ≪ rythme ≫ dans son expression linguistique” (republished in the 1966 work), focuses on the notion of rhythm. Having recognized that the word has been generalized (in fact it could be applied to all human activities, when their duration and succession are considered), Benveniste retraces its origins and observes its change. The scholar comes to the conclusion that the concept that today is commonly attributed to the term (that is, an ordered sequence of movements), is not the original one but is due to Plato. The word ρυθμóς in the Greek world meant “form” (to be precise, it meant distinctive form, proportionate figure, arrangement), in various contexts.

11. ^The title is based on the opinion of Paul Scott, a deaf poet who composes in BSL (British Sign Language). The essay refers to the literature originally produced in sign language, but we think that the considerations can be extended to the translation.

12. ^In this work we focus in particular on the poetic translation from vocal language into sign language, but our conclusions are reached in the light of a broader reflection that also includes the translation in the other verse. For further information, see Raniolo (2021).

13. ^Iconic productive structures account on average for 13.5% of formal discourse (conferences), 43% of free storytelling and 53.4% of poetry [Russo Cardona, 2004].

14. ^Original edition 1938.

15. ^He proposed to go beyond the text, not to submit to it, but rather to subject it to a compression énergique (energetic compression, our translation) (Artaud, 1964, original edition 1938, p. 133).

16. ^The poem is taken from a collection dating back to about twenty years ago (Leopardi, 2001). Translation to English by Jonathan Galassi (2010): This lonely hill was always dear to me, / and this hedgerow, which cuts off the view / of so much of the last horizon. / But sitting here and gazing, I can see / beyond, in my mind's eye, unending spaces, / and superhuman silences, and depthless calm, / till what I feel / is almost fear. And when I hear / the wind stir in these branches, I begin / comparing that endless stillness with this noise: / and the eternal comes to mind, / and the dead seasons, and the present / living one, and how it sounds. / So my mind sinks in this immensity: / and foundering is sweet in such a sea.

17. ^The translation is available on the website https://www.raniolotraduzionils.it/ The password is TRAD LS Raniolo, E., Traduzioni in LIS e LSF, accessed March 11, 2022 (Raniolo, 2022).

18. ^Our choice of a poem based on perceptions allows us to give full realization to our reflections; however, in our opinion, they would still be valid even in the case of a poem of a different nature, but perhaps to a lesser extent (an aspect that could be interesting to investigate).

References

Antinoro Pizzuto, E., Chiari, I., and Rossini, P. (2008). “The representation issue and its multifaceted aspects in constructing sign language corpora: questions, answers, further problems”, in Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (3rd Workshop on the Representation and Processing of Sign Languages: Construction and Exploitation of Sign Language Corpora), Marrakech, 26th May – 1st June 2008, European Language Resources Association, eds O. Crasborn, E. Efthimiou, T. Hanke, E.D. Thoutenhoofd, and I. Zwitserlood (Paris), 150–158.

Bauman, H. L., Nelson, J. L., and Rose, H. M. (2006). (a cura di), Signing the Body Poetic. Essays on American Sign Language Literature. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Buonomo, V., and Celo, P. (2010). L'interprete di lingua dei segni italiana. Problemi linguistici, aspetti emotivi, formazione professionale, Hoepli Editore, Milano.

Catteau, F., and Blondel, M. (2016). Stratégies prosodiques dans la traduction poétique de la LSF vers le français, in Double sens, revue de l'association des interprètes et traducteurs en langue des signes (AFILS), 27–38.

Celo, P. (2009). I Segni del ‘900. Poesie italiane del Novecento tradotte nella Lingua dei Segni Italiana. Libreria Editrice Cafoscarina, Venezia.

Celo, P. (2015). I segni del tradurre. Riflessioni sulla traduzione in Lingua dei Segni Italiana, Aracne, Roma.

Chateauvert, J. (2016). Le tiers synesthète : espace d'accueil pour la création en langue des signes, in Intermédialités: Histoire et théorie des arts, des lettres et des techniques / Intermedialité: History and Theory of the Arts, Literature and Technologies, n. 27. Available online at: https://doi.org/10.7202/1039816ar (accessed March 12, 2022).

Cohn, J. (1999). Sign Mind: Studies in American Sign Language Poetics. Boulder, CO: Museum of American Poetics.

Crasborn, O. (2006). A linguistic analysis of the use of the two hands in sign language poetry, in Linguistics in the Netherlands, eds J. van de Weijer, B. Los. John Benjamins, Amsterdam, 65–77.

Finnegan, R. (1977). Oral poetry: Its Nature, Significance and Social Context. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Fontana, S. (2014). Traduzione e traducibilità tra lingue dei segni e lingue vocali, Rivista Italiana di Filosofia del Linguaggio, 102–111.

Fontana, S. (2016). Tradurre la poesia: un percorso possibile tra segni e parole?, ed Blityri V, Edizioni ETS, Pisa, 129–142.

Franchi, M. L., and Maragna, S. (2013). Manuale dell'interprete della lingua dei segni italiana. Un percorso formativo con strumenti multimediali per l'apprendimento, Franco Angeli, Milano.

Galassi, J. (2010). Infinity, translation of L'Infinito, in G. Leopardi, Canti (poems, bilingual edition translated and annotated by J. Galassi), Farrar, Straus and Giroux, New York.

Gallese, V., and Sinigaglia, C. (2011). What is so special about embodied simulation?, Trends Cogn. Sci. 15, 512–519. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2011.09.003

Garcia, B., and Sallandre, M. A. (2013). Transcription systems for sign languages: a sketch of the different graphical representations of sign language and their characteristics, in Body-Language-Communication. An international handbook on multimodality in human interaction, Vol. 1, eds C. Müller, A. Cienki, E. Fricke, S. Ladewig, D. McNeill, and S. Teßendorf. De Gruyter Mouton, 1125–1338.

Houwenaghel, P., and Risler, A. (2020). Traduire la poésie signée, in La traduction épistémique: entre poésie et prose, ed T. Milliaressi. Presses universitaires du Septentrion, Villeneuve d'Asc. Available online at: https://doi.org/10.4000/books.septentrion.93768 (accessed March 12 2022).

Jouison, P. (1995). Ecrits sur la langue des signes française, edited by Brigitte Garcia, L'Harmattan, Paris.

Lavieri, A. (2016a). Translatio in fabula. La letteratura come pratica teorica del tradurre, Editori Riuniti, Roma (original edition 2007).

Lavieri, A. (2016b). Tradurre il Mon Faust. Il senso, la scena, la voce, Testo a fronte, n. 55, II semester, 25–32.

Leopardi, G. (2001). L'Infinito (XII), in Canti, introduction by F. Gavazzeni, notes by F. Gavazzeni and M.M. Lombardi, 3rd Edn, Biblioteca Universale Rizzoli, Milano, 267–274.

Meschonnic, H. (1982b). Qu'entendez-vous par oralité, Langue française, n. 56, 6-23. Available online at: https://www.persee.fr/doc/lfr_0023-8368_1982_num_56_1_5145 (accessed March 9, 2022).

Mirzoeff, N. (1995). Silent poetry. Deafness, sign, and visual culture in modern France, Princeton University Press, Princeton.

Ormsby, A. (1995). The Poetry and Poetics of American Sign Language (Unpublished PhD thesis), Stanford University, Stanford, CA.

Paredes, P. E., Hamdan, N. A., Clark, D., Cai, C., Ju, W., and Landay, J. A. (2017). Evaluating in-car movements in the design of mindful commute interventions: exploratory study J. Med. Internet Res. 19, e372. doi: 10.2196/jmir.6983

Peters, C. L. (2000). Deaf American Literature. From Carnival to the Canon, Gallaudet University Press, Washington, DC.

Pollitt, K. (2019). Affordance as Boundary in Intersemiotic Translation: Some Insights from Working with Sign Languages in Poetic Form, in Translating across Sensory and Linguistic Borders - Intersemiotic Journeys between Media, eds M. Campbell and R. Vidal. Palgrave Macmillan, London/New York, 185–216.

Raniolo, E. (2021). Senso, ritmo, multimodalità. Uno studio comparativo dei processi traduttivi nelle lingue dei segni (LIS e LSF) (unpublished PhD thesis), discussed on May 17, Università degli Studi di Palermo, thesis director prof. A. Lavieri.

Raniolo, E. (2022). Traduzioni in LIS e LSF Available online at: https://www.raniolotraduzionils.it/ (accessed March 11, 2022).

Rizzi, M. (2009). Il ragno e la tela, in Studi di Glottodidattica, Bari: Universitá degli Studi di Bari Aldo Moro, break 106–117.

Russo Cardona, T. (2004). La mappa poggiata sull'isola. Iconicità e metafora nelle lingue dei segni e nelle lingue vocali, Centro Editoriale e Librario Università degli Studi della Calabria, Rende.

Russo Cardona, T., Giuranna, R., and Antinoro Pizzuto, E. (2001). Italian Sign Language (LIS) Poetry. Iconic properties and structural regularities, in Sign Language Studies, vol. 2, n. 1, 84–102; 104–112.

Sallandre, M. A. (2010). Va et vient de l'iconicité en langue des signes française , Acquisition et interaction en langue étrangère, 15, 2001, uploaded online November 9. Available online at: http://aile.revues.org/1405 (accessed March 8, 2022).

Spread The Sign Dictionary (2022). Available online at: https://www.spreadthesign.com/it.it/search/ (accessed March 9, 2022).

Stokoe, W. (1960). Sign Language Structure. An Outline of the Visual Communication Systems of the American Deaf, Studies in Linguistics, Occasional Papers, 8, University of Buffalo, Buffalo (NY).

Sutton-Spence, R. (2010). Spatial metaphor and expressions of identity in sign language poetry, in Metaphorik.de, 19, 47–86.

Sutton-Spence, R., and de Quadros, R. M. (2014). “I am the book” – Deaf poets' views on signed poetry, J Deaf Studies Deaf Educ. 19, 546–558.

Sutton-Spence, R., and Kaneko, M. (2016). Introducing Sign Language Literature. Folklore and Creativity, Palgrave and Macmillan London.

Taub, S. (2001). Language from the body. Iconicity and Metaphor in American Sign Language, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Valli, C. (1993). Poetics of American Sign Language Poetry, (Unpublished PhD dissertation), Cincinnati: The Union Institute Graduate School.

Keywords: translation, poetry, sign language, Italian Sign Language (LIS), embodied cognition

Citation: Raniolo E (2022) Translating Poetry in Sign Language: An Embodied Perspective. Front. Commun. 7:806132. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2022.806132

Received: 31 October 2021; Accepted: 28 April 2022;

Published: 23 May 2022.

Edited by:

Erin Wilkinson, University of New Mexico, United StatesReviewed by:

Rachel Sutton-Spence, Federal University of Santa Catarina, BrazilPierre Schmitt, École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales, France

Copyright © 2022 Raniolo. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Erika Raniolo, ZXJpa2EucmFuaW9sb0BnbWFpbC5jb20=

Erika Raniolo

Erika Raniolo