95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Commun. , 03 June 2022

Sec. Health Communication

Volume 7 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomm.2022.781564

This article is part of the Research Topic Global Suffering and Uncertainty in the COVID-19 Pandemic: Exposing the Fault Lines through Narrative/Discourse Analysis View all 4 articles

Canadians take great pride in their social values such as human and civil rights, universal health care and good government. In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, federal and provincial leadership teams forged new partnerships via shared focus, voluntariness, jurisdictional respect, and lowering of barriers. In our analysis focusing on the Province of British Columbia, we compare and contrast how leadership and politics have impacted the response to COVID-19 vs. the response to B.C.'s concurrent public health emergency, the overdose crisis. We argue that these dual epidemics are framed differently in the public discourse, and that a significant disparity emerges in how the two public health emergencies have been handled at every level of government. We further posit that constructing the narrative around a communicable disease outbreak such as COVID-19 is easier than for the overdose crisis, in large part because COVID-19 impacts every person whereas the overdose crisis is perceived to have a narrow impact on the population. We use three key communications indicators in our analysis: a) the primary groups that messaging from leadership needed to reach; b) the programs and initiatives that leadership needed to ensure receive broad dissemination; and c) the messaging and tone required to achieve the desired impact to encourage societal change. On the basis of our analysis, we conclude that Canada needs to be better at building the types of supports it has created to manage the COVID-19 crisis in order to also support individuals who are immersed in the overdose crisis. Many of the policy and communication decisions and insights learned through the COVID-19 pandemic can, and ought to, be put into effect to mitigate the ongoing overdose crisis in B.C. and beyond. Examples include: consistent messaging that emphasizes respect for all and reflects determination from our political leaders as they work together to change the narrative and enact policy change. COVID-19 has shown us that if we are determined and focused, even if we occasionally run into obstacles, we can move the dial forward to mitigate—and perhaps even eliminate—a health crisis.

On April 14, 2016, British Columbia's (B.C.) provincial health officer declared a public health emergency due to a significant increase in opioid-related overdose deaths. Although the overdose (or drug toxicity) crisis is national in scope, the Province of British Columbia continues to experience a disproportionately higher rate of deaths attributed to illicit drug overdoses, at 31.2 per 100,000 population (age-adjusted), relative to 11.9 for the whole of Canada (Special Advisory Committee on the Epidemic of Opioid Overdoses, 2021). Because need drives response, B.C. has often been cited as the leading jurisdiction in overdose crisis management (KPMG, 2018). However, on March 17, 2020, almost four years after the initial declaration, the overdose public health emergency was still in place even as B.C.'s provincial health officer declared a second public health emergency to support the province-wide response to the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. At the time of writing, Canada has two ongoing and concurrent public health emergencies, but the urgency with which policymakers and the public have responded to these dual epidemics is vastly different. B.C. and the rest of Canada continue to gain ground on managing the COVID-19 pandemic, but in contrast, the province recorded the highest number of overdose deaths ever in 2021. The COVID-19 pandemic has created an opportunity to interact with and reflect on our institutions in a way we may never have done before. For many, the pandemic has reinforced the necessity of having strong public institutions that are able to respond to crises and support Canadians when they need them most (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2021d).

As a whole, Canadians take a vast sense of pride in their health and social justice systems (Cameron and Berry, 2008; Martin et al., 2018). As Canadians have been required to readjust their thinking about successes and failures during the COVID-19 pandemic, many have begun to understand and recognize that the institutions that they have celebrated are insufficient in managing factors that contribute to equity and social justice.1 If we dare to look at our handling of the overdose crisis federally, provincially and municipally, we recognize that while there has been some investment and policy development regarding drug policy reform, we are now more than six years since the overdose crisis was declared an emergency. Our existing health system has not adapted to the types of responses an overdose crisis required. Unlike with COVID-19, in which there are continual, urgent, and reactive structural and policy changes, there has been almost no improvement—or even change—in how the overdose situation is unfolding. In this paper, we explore some of the structures and narratives that contribute to these outcomes.

In Canada, under the Canada Health Act (Government of Canada, 1985), the Federal government co-finances health care programs; the programs are primarily managed and delivered by the provinces and territories. The Canada Health Act sets pan-Canadian standards for medically necessary hospital, diagnostic, and physician services and requires adherence to the five underlying principles: publicly administered, comprehensive in coverage, universal, portable across provinces, and accessible (meaning that there are no user fees). The federal government also regulates the safety and efficacy of medical devices, vaccines/pharmaceuticals, and natural health products; funds health research; and administers several public health functions. Most provinces and territories have further established regional health authorities responsible for the delivery of hospital, community, and long-term care, and mental and public health services. B.C.'s First Nations Health Authority is the only provincial First Nations health authority in Canada. Provinces/territories also bear the responsibility of regulating health care professions (Allin et al., 2020, Figure 1). Conversely, drug policy reform falls under federal legislation such as the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act (Government of Canada, 1996) which is part of the Criminal Code.

For the purpose of this paper, we focused on the overdose and COVID-19 situations in B.C., primarily because the opioid overdose crisis has deep historical roots in our home province. B.C. has a diverse population of 5.071 million (approximately 13 per cent of Canada's population) spread across 944,735 square kilometers (four times the size of the United Kingdom) (Lawrence, 2021). The majority of B.C.'s population is clustered in the southwest corner of the province. As noted above, B.C. has consistently reported the highest number of deaths (per capita) since the beginning of the overdose crisis, while simultaneously establishing the most progressive drug policies in Canada, such as leading the call for decriminalization and establishing the first secure injection/consumption site. Other provinces/territories have been slower to take action, often due to a lack of political will, and this inaction has resulted in a disorganized approach to drug policy reform across the country.

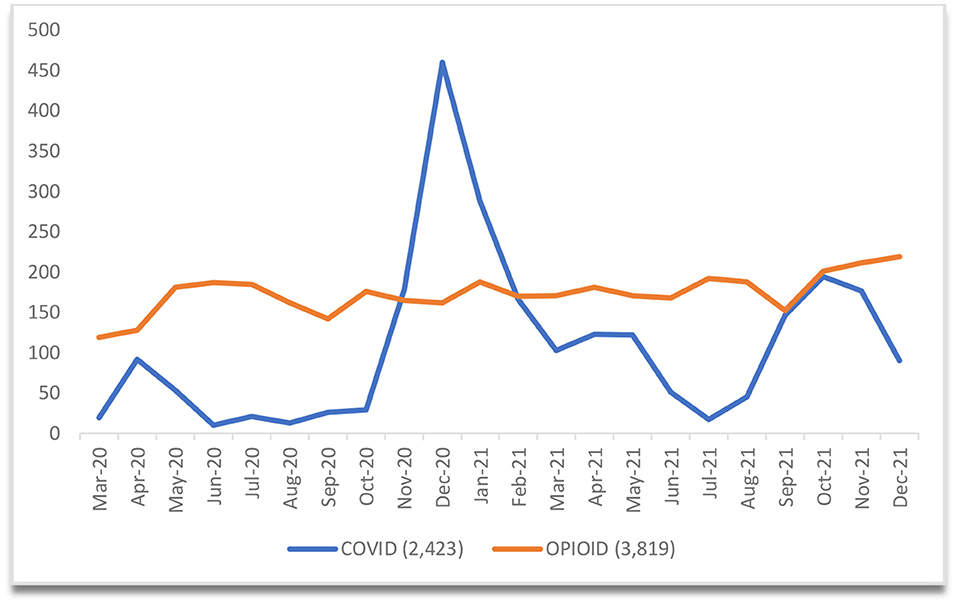

During the period since B.C. declared the overdose crisis a public health emergency up until the end of 2021, there have been 8,785 documented overdose deaths (April 2016 to December 31, 2021) (B.C. Coroners Service, 2022b). The toxic drugs causing overdoses are not only associated with opiates; in fact the unregulated, unpredictable, and increasingly toxic drug supply means that toxic drugs (such as fentanyl) are making their way into all types of substances. Thus, the “opioid overdose” crisis is more accurately depicted using terms such as “overdose” and “drug toxicity” crisis (Government of B.C., 2021e; B.C. Coroners Service, 2022a). From the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic (March 2020) until December 31, 2021, there have been approximately 2,423 deaths resulting from complications with COVID-19 in B.C. (Government of B.C., 2021b; B.C. Centre for Disease Control, n.d).2 The lag in reporting of overdose deaths makes it challenging to accurately compare up to the current date, but Figure 1 shows death during the first 20 months of the pandemic in contrast to the same period of the overdose crisis. The Government of Canada states, “The opioid overdose crisis continues to have significant impacts on Canadians, their families, and communities, and remains one of the most serious public health crises in Canada's recent history” (Government of Canada, 2021e, para 2). The high number of deaths due to overdose implores us to challenge the quality of our universal health care system when we have not made any substantive inroads into one of the most significant public health crises of our lifetime.

Figure 1. Opioid-related and COVID-19 Deaths in B.C. Between March 1, 2020 and December 31, 2021. B.C.'s first recorded COVID-19 death was March 8, 2020. B.C. reports COVID-19 deaths daily (Mon-Fri) (B.C. Centre for Disease Control, n.d). B.C. reports “confirmed and suspected illicit toxicity deaths” once per quarter (B.C. Coroners Service, 2022b).

What we have learned during COVID-19 is that we do have existing structures, both in terms of governance and our public institutions, to quickly, effectively, and with great determination, tackle a complex and concerning public health issue such as a pandemic. How do we then translate this success and the oversight that our institutions and leadership have provided, and apply some of the same communication and strategic tactics to other public health priorities? As it stands currently, the overdose crisis began four years prior to the pandemic and will still be going on long after we have learned how to manage COVID-19. For readers who are less familiar with the language and terminology related to the overdose crisis, the explanations in Box 1 may prove helpful.

Box 1. Terminology related to the overdose crisis.

Drug Decriminalization is an evidence-based policy strategy to reduce the harms associated with the criminalization of illicit drugs. For those who use illicit drugs, these harms include criminal records, stigma, high-risk consumption patterns, overdose, and the transmission of blood-borne disease. Decriminalization aims to decrease harm by removing mandatory criminal sanctions, often replacing them with responses that promote access to education and to harm reduction and treatment services. Not a single approach or intervention, decriminalization describes a range of principles, policies, and practices that can be implemented in various ways (Jesseman and Payer, 2018).

Drug Policy Reform is any action undertaken by a government to alter existing laws, statutes, codes, ordinances or precedents to generally reduce the severity of sentences, level of prosecution or amount of enforcement as it relates to (usually) possession, especially of minimal amounts of illegal substances. Much of drug policy reform and success in the twenty-first century, has focused on the decriminalization or legalization of cannabis for medicinal, industrial, and recreational purposes. Proponents of drug policy reform often take the position that the “war on drugs” that has been waged in the western world for so long, has not been successful and that it is time to adopt a new approach (Harm Reduction International1). Numerous organizations, coalitions, and groups under the drug policy reform umbrella advocate to all levels of government in Canada.

Harm Reduction refers to policies, programs, and practices that aim to minimize negative health, social and legal impacts associated with drug use, drug policies and drug laws. It is grounded in justice and human rights and focuses on positive change and on working with people without judgement, coercion, discrimination, or requiring that they stop using drugs as a precondition of support. Harm reduction encompasses a range of health and social services and practices that apply to illicit and licit drugs. These include, but are not limited to, drug consumption rooms, needle and syringe programmes, non-abstinence-based housing and employment initiatives, drug checking, overdose prevention and reversal, psychosocial support, and the provision of information on safer drug use. Approaches such as these are cost-effective, evidence-based, and have a positive impact on individual and community health (Harm Reduction International).

Injectable Opioid-Assisted Treatment (iOAT) programming forms the empirical evidence base underlying safe supply. IOAT programming in Canada uses injectable hydromorphone and in a few cases injectable diacetylmorphine (heroin) in therapeutic supervised and unsupervised settings for people with opioid dependence (Haines and O'Byrne, 2021).

Opioid Agonist Therapy (OAT) is an effective treatment for addiction to opioid drugs such as heroin, oxycodone, hydromorphone (Dilaudid), fentanyl, and Percocet. The therapy involves taking prescribed opioid agonists methadone (Methadose) or buprenorphine (Suboxone). These medications work to prevent withdrawal and reduce cravings for opioid drugs. People who are addicted to opioid drugs can take OAT to help stabilize their lives and to reduce the harms related to their drug use (Centre for Addiction Mental Health, 2016).

People who use drugs (PWUD) is a phrase aimed at helping to convey acceptance and understanding when talking about people who use drugs. Language such as addict or drug user can add to the stigma and rejection that people who use drugs so often encounter.

Recovery-oriented treatment systems offer an integrated approach to promoting the health of the addicted individual as well as the improved function of the family and community through a focus on social contribution. Emerging recovery definitions emphasize that recovery is more than the removal of destructive alcohol and/or drug use from an otherwise unchanged life. Recovery is a broader process that involves a radical reconstruction of the person-drug relationship, progressive improvement in global health, and the reconstruction of the person-community relationship (McLellan and White, 2012).

Safe supply is a phrase that flows from a long history of struggle against limitations and legal sanctions imposed upon PWUD. As a concept, safe supply's aim is systemic change: To provide legal and regulated drugs to people at risk of overdose as an alternative to the illicit drug markets (Canadian Association of People Who Use Drugs, 2019).

In addition, the book Overdose: Heartbreak and Hope in Canada's Opioid Crisis by UBC law professor Benjamin Perrin (2020b) provides a comprehensive plain language overview of this topic.

1. ^What Is Harm Reduction? Available online at: https://idpc.net/policy-advocacy/drug-policy-reform (accessed February 1, 2022).

Public health is a core responsibility of government. Health agencies alone are not solely responsible and in Canada, the “public health system” comprises many organizations across its 13 provinces and territories. These bodies include national and provincial ministries, agencies, organizations, and associations; Indigenous health organizations; local health authorities, and others. According to the Public Health Agency of Canada (2021d), “The overarching purpose of the public health system involves working toward optimal health and well-being for all people in Canada. In support of this purpose are three aims centered on protecting and enhancing the health of populations while achieving equitable health outcomes” (p. 48). The overdose crisis and COVID-19 pandemic are, of course, distinct public health emergencies that have necessitated different types of responses. While the overdose crisis and COVID-19 share some common traits, including global impacts, our intent in this paper is to highlight the very different ways these epidemics are framed in the public discourse:

• COVID-19 is a unique situation that the modern world has never experienced before. In the public health field, COVID-19 represents the health surveillance and emergency preparedness/response work many have done for decades around communicable disease control (e.g., sexually transmitted infection, Ebola) (Fournier and Karachiwalla, 2020; Public Health Agency of Canada, 2021d). This type of activity might be perceived as the more interesting part of public health work involving instant and swift reactions, fast decision-making, and solutions that change often as the situation unfolds.

• The overdose crisis, on the other hand, reflects the more steady and normalized type of health protection and disease/injury prevention that are also essential public health functions (along with, for example, reducing heart disease, ending smoking, wearing bike helmets, and addressing impacts of climate change). These activities reflect the core work of a public health system yet do not necessarily carry the same sort of intrigue and magic contained within a worldwide pandemic.

Ultimately, however, we can draw significant parallels between these dual epidemics as we reflect on what we have learned from COVID-19 to improve our response to the overdose crisis (as well as to future disease outbreaks). When we compare and contrast the response to COVID-19 vs. the response to the overdose crisis, a significant disparity emerges in how these two public health emergencies have been handled at every level of government. Specifically, for the purposes of this paper, we focus on how leadership and politics have impacted the COVID-19 pandemic and the overdose crisis in B.C. using three key communications indicators:

• The primary groups that messaging from leadership needed to reach (Table 1),

• The programs and initiatives that leadership needed to ensure receive broad dissemination (Table 2), and

• The messaging and tone required to achieve the desired impact (modification of attitudes, acquisition of knowledge, behavior change in individuals and groups) and encourage societal change (Table 4).

We examine both public health emergencies from each of these perspectives and consider the similarities and differences in approach. Lastly, we consider what we can learn from this comparison to recommend a stronger, and hopefully more successful, response to the ongoing overdose crisis.

One of the key components of any public health response is determining who the audience is that needs to receive information (Table 1). On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the 2019 novel coronavirus a global pandemic (World Health Organization, 2020a). When COVID-19 first became a known issue, governments around the world were quick to respond with lockdowns, urgent news conferences, and dire warnings of the potential the pandemic could have on the health and safety of individuals. In the case of COVID-19, “everyone” on the planet needed to hear the information, and the fastest conduit to achieve that is through the media. However, Sauer et al. (2021) note that throughout COVID-19, “widespread public health measures have been accompanied by a massive flow of COVID-19 information, misinformation, and disinformation. We are concurrently inundated with a global epidemic of misinformation, or an infodemic, primarily being spread through social media platforms; its effects on public health cannot be underestimated” (p. 67).

The bulk of quality communications throughout the pandemic at the national, provincial and local levels has been delivered by political and health leaders via news conferences where the media are empowered to ask direct questions of leadership on behalf of the public. A 2020 survey by Ryerson University showed that, when getting news about COVID-19, 61 per cent [of Canadians] reported that they trust the news when delivered from the public service, government, or a ministry department. This includes messages that are not filtered or analyzed (e.g., direct words from the prime minister). With respect to filtered (opinions) or interpretations by the media, 49 per cent of respondents felt they trust major media to get it right (Gruzd and Mai, 2020).

In B.C., the media has arguably played the most important role in getting information out (both good and bad) throughout the pandemic. With the health minister and provincial health officer broadcasting daily (and then weekly) news conferences with statistics, orders (restrictions), and information, British Columbians had an opportunity to hear analysis from the Legislative Press Gallery on a daily basis, with the same reporters asking questions and publishing their stories, not only on their own media platform, but also through their personal and public social media channels. According to public relations practitioner Hoggan (2021), “regular briefings on the COVID-19 pandemic delivered by British Columbia's top doctor are a master class in communicating during a public emergency” (p. 27). As a result, the media messaging in B.C. was fairly well-controlled, providing stakeholders with a largely unbiased, clear indication of the current status of COVID-19 in the province. Current COVID-19 information was (is) almost always the top news story, and British Columbians were generally well-informed (Chhabra, 2021).

It could be argued that this high level of trust and acclaim given to the media and officials throughout the pandemic was doomed from the start. The longer the pandemic has worn on, the harder it has been for people to believe and accept the assurances of leaders, particularly as things that were true one day (e.g., masks are not necessary; vaccine passports will not be implemented) were subsequently changed a month later (e.g., masks are mandatory; vaccine cards are required). As a result, the public has increasingly lost patience with leadership and with the media who delivers the message. This experience seems to be shared around the world, most notably with Dr. Anthony Fauci in the US (Florko, 2020). During the initial stages of the pandemic, Dr. Bonnie Henry was widely hailed as a hero (Marsh, 2020; Porter, 2020) by most British Columbians, to the point that songs were written in support of her work (Parmar and Bethlehem, 2020), a mural of her image painted in one Vancouver neighborhood and even a shoe designed in her honor by John Fluevog (Devlin, 2020). The tides have turned for Dr. Henry as well, with increasing discontent on social media over her work, protests, and the need to hire a security detail. This pandemic fatigue would be challenging in any long-term situation that causes discomfort and even in (World Health Organization, 2020b), the WHO recognized the need to reinvigorate the public and put forth plans and strategies to mitigate the effects of pandemic fatigue.

Unfortunately, it is not always easy to define exactly who needs to receive government messages and information. In regard to the pandemic, every British Columbian was impacted, and therefore, information was required to go to a broad audience. Alternatively with the overdose crisis, there is no clear decision at any level of government, on who the message needs to reach. Some would say people who use drugs (PWUD), some would say the families and friends of PWUD, others would say health and social service providers or other levels of government. Ultimately, it is much easier to target “everybody” than it is to target “some people who have only a few indicators in common.”

Aside from a handful of interested journalists, the Canadian and B.C. media does not appear to have been encouraged to learn and understand the scope of the overdose problem or how to report it in an accurate, respectful, and de-stigmatizing manner. The willingness of the public to accept the overdose crisis as something deserving of their attention is very different than COVID-19, as many remember the “War on Drugs” campaign of the 1980s [“this is your brain, this is your brain on drugs” (Partnership for a drug free America3)] and the fear that was intentionally imposed regarding the dangers of illicit drugs. And while the narrative around drug use has changed significantly in the past 30 years, the accompanying communication and media strategies have not followed suit. Thus, it is no surprise that in many cases, neither has the opinion of the public shifted.

The federal government has done very little campaigning or messaging around the overdose crisis and tends to leave the responsibility for messaging to the provincial governments. This is a realistic expectation because, as noted above, the Canada Health Act gives the provinces and territories primary responsibility for organizing and delivering health services and supervising health care providers. Ultimately, the biggest difference between delivering messaging on COVID-19 and messaging on the overdose crisis, lies in the inability of politicians and leaders to clearly identify the correct audience that needs to be reached regarding the overdose crisis, and to put in place the associated messaging and strategies to keep any messaging delivered at the forefront of the public's consciousness. With COVID-19, governments have accepted the responsibility to ensure every person receives instructions and information as quickly as possible. In contrast, there is no similar clarity when it comes to the overdose crisis (Table 2). Governments are also responsible to communicate regarding toxic drugs, but the stigma that citizens have toward PWUDs mean that, in practice, the actual dissemination of overdose-related information is deemed a lower priority and often outsourced to consultants and advocates.

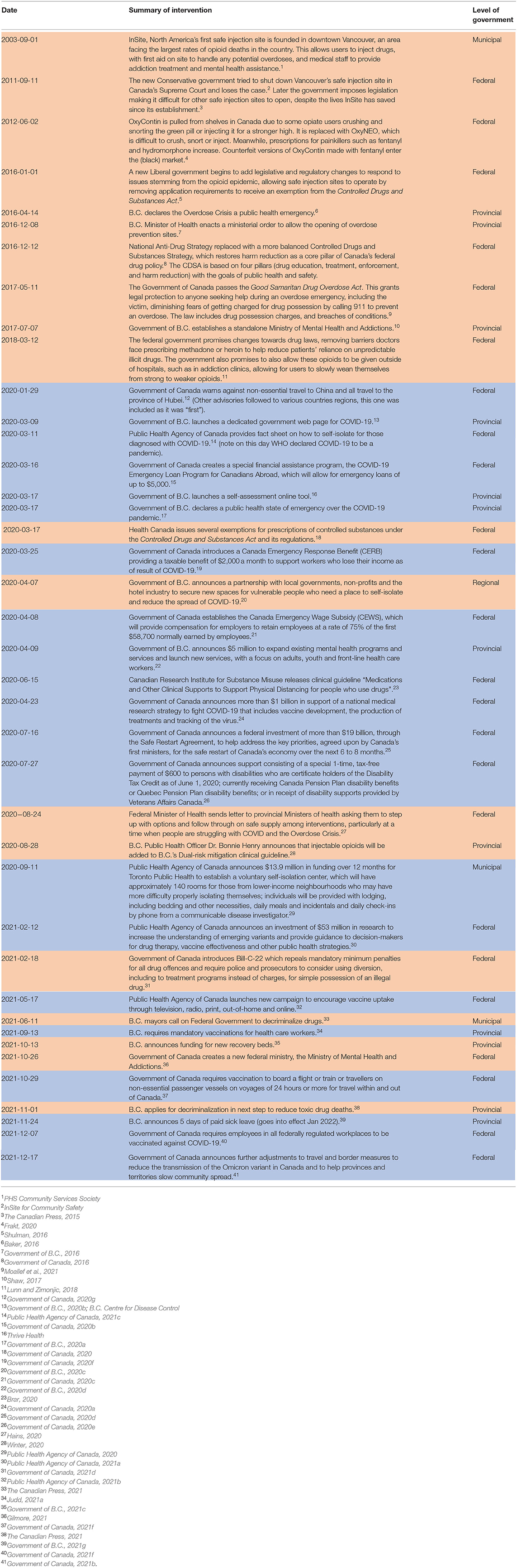

To facilitate our analysis of B.C.'s responses to the dual public health emergencies, we have compiled Table 3 to demonstrate the parallel timeline of select government (federal/ provincial/municipal) overdose-related interventions (beginning in 2003 with the opening of InSite) (shaded orange) and COVID-19 interventions (shaded blue). In what follows, we analyze the two narratives by comparing and contrasting how policymakers have managed these concurrent public health crises up until the end of 2021.

Table 3. Parallel timeline of select government (federal/provincial/municipal) overdose-related interventions and COVID-19 interventions (until December 31, 2021).

Immediately following the realization that COVID-19 was likely to have a significant impact in and on Canada, the federal government established programs and resources to help individuals safely ride out the pandemic. This involved the Government of Canada, a minority government, to quickly propose and pass several Legislative Acts designed to make management of the pandemic more efficient (Table 3). These measures included not only emergency funding, such as the Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB), which was an extension of Canada's Employment Insurance Program and offered those who were laid off due to the lockdown $2,000 per month (Government of Canada, 2021a), as well as the Canada Emergency Wage Subsidy (or CEWS), which was designed to support businesses in managing overhead with an eye to recovery post-pandemic, but also the procurement of vaccines and medical equipment and closing of the international border (Government of Canada, 2022c). Provincial/territorial governments also stepped up with increased programs and solutions to support citizens, such as rent relief and student financing programs (B.C. Housing4). Within provinces/territories, public health authorities worked closely with regional public health officers, local/municipal governments, and other partners, such as laboratories and pharmacies, to set policies and recommendations and to implement services, such as COVID-19 testing and contact tracing, and later to ensure citizens had easy access to free vaccines. The federal government was supportive, but its initial policies were focused on issues like international border closings and managing federal stockpiles of personal protective equipment, testing kits, and ventilators.

Although local/municipal governments do not have the same access to legislative tools or funds, their contributions throughout the pandemic have been no less significant as each municipality, along with its health authority, has been responsible for managing testing and immunization clinics within its catchment. This is a shared responsibility with the province/territory wherein the municipality and health authority manage things such as traffic flow and signage.

In a collaborative effort, Canada's federal government announced the Safe Restart Agreement in September 2020, which was intended to provide funding for provinces/territories and cities to recover economically from the pandemic and prepare themselves for future possible disruptions (Government of Canada, 2020). This investment was a clear example of federal/provincial/municipal collaboration and was a commitment of $19 billion in funds that would be dispersed by provincial/territorial government on a per capita basis (Horgan, 2020). Vancouver mayor, Kennedy Stewart, argued against the efficacy of this program on the basis that the funds were not appropriately administered (Horgan, 2020; McElroy, 2020). However, by and large, the Safe Restart fund provided an economic stimulus that was much-needed and valued to boost the economy.

Throughout COVID-19, it has been evident through media reports and the interventions described in Table 3 that there has been considerable cooperation between federal and provincial/territorial officials and politicians, and relatively little acrimony or conflicting messaging between levels of government. The federal government continually acknowledged the close collaboration required to succeed with managing the pandemic. For example, according to Katherine Cuplinskas, Chrystia Freeland's (deputy prime minister of Canada) spokesperson, “The prime minister and deputy prime minister have been in communication with Canada's premiers every step of the way. This has been a true Team Canada effort” (Hains, 2020, para 27).

The COVID-19 pandemic continues to create chaos around the world. The overdose crisis also has far-reaching consequences and is rapidly gaining casualties, yet the speed with which programs and supports were provided to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic has not been matched for those struggling with the overdose crisis. In fact, despite having been declared a public health emergency in B.C. almost seven years ago, based on our analysis in Table 3, the level of response (with all levels of government) remains much less than what we have seen since the beginning of COVID-19. In particular, innovative strategies, such as injectable opioid agonist treatment, naloxone distribution programs, overdose prevention sites, and drug checking services (Box 1) are emerging and expanding in some provinces and countries (less so in others as partisan politics override the evidence in terms of handling a health emergency). For example, iOAT programs in Switzerland (e.g., heroin-assisted treatment or HAT) have, for decades, now permitted “take home” or “carry” doses, which allow program participants the ability to use prescribed drugs at home, providing them greater autonomy in treatment (Strang and Taylor, 2018). Switzerland confirmed HAT via a referendum on the Swiss Narcotic Law in 2008, including provisions for up to two days of take-home doses. Despite B.C.'s advantage relative to the rest of Canada, the province's iOAT programming lags behind established standards of care in Europe. Typically, program participants must attend the program at least two to three times daily in B.C. Moreover, because such innovative harm reduction strategies are not the norm, the benefits of such strategies are not equitably distributed to people at risk of overdose in B.C., or across Canada.

While there are a small number of examples of innovative strategies in response to the overdose crisis, the crisis shows few signs of abating. To truly address this crisis, Canada needs governments at every level to be nimble and responsive as they work toward fully implementing a range of harm reduction strategies in addition to supporting rehabilitation and recovery (Strike and Watson, 2019). Programs and resources that respond to the overdose crisis are largely an uncoordinated patchwork, and funding opportunities are administered through small organizations or health authorities. In B.C., there is at least recognition of the problem and in 2017 the province implemented a Ministry of Mental Health and Addictions to manage the situation. B.C. has a slight advantage over other provinces/territories in that drug policy reform has been at the top of mind for many since Vancouver fought for Insite (North America's first legal supervised consumption site) at the Supreme Court (Harati, 2015). Building on this momentum, B.C. has also moved forward with some legislation and public health orders to try to mitigate the overdose crisis. Due to the lack of a full response by the federal government to what was a declared overdose death crisis, in September 2016 activists set up two unauthorized supervised injection tents in Vancouver's Downtown Eastside neighborhood. These community-driven responses were then acted upon by the B.C. Minister of Health, who concurred that federal approval for safe injection sites was taking too long. In December 2016, Minister Terry Lake issued a Ministerial Order under the Health Emergency Services Act and Health Authorities Act to support the development of overdose prevention sites (Government of B.C., 2016).

Municipally, the mayors of B.C. have regularly presented resolutions at their Union of B.C. Municipalities (UB.C.M) meetings, in an attempt to influence drug policy reform at both the provincial and federal levels. For example, in 2019 mayors voted in favor of passing resolutions “Safer Drug Supply to Save Lives” and in 2018 “Supporting a Comprehensive Public Health Response to the Ongoing Opioid Crisis in British Columbia” (Union of B.C. Municipalities, 2018). However, it is much more challenging and less effective to launch responses on the municipal level than on the provincial level, which is arguably the center of where drug policy and programs need to be established and managed.

Health Canada states, “The opioid crisis has brought to light the devastating effects opioids are having on individuals, families and communities across Canada” (Government of Canada, 2019, para 1). According to these same proponents of drug policy reform, indicators of a positive impact related to the overdose crisis interventions include: lowered stigma about drug use; lowered drug use; fewer overdoses and related deaths; reduced crime; and reduced need for heavy police involvement. Mayors in B.C. as well as other Canadian cities, have pushed the need for decriminalization to the provincial and federal governments, with the hope that by moving decriminalization forward, measurable improvements related to the overdose crisis will be possible (Larsen, 2021).

As outlined in Box 1, safe supply refers to providing legal and regulated drug alternatives to the unpredictable nature of the illicit drug supply. In fact, there are no legal barriers to a physician giving a prescription for safe supply drugs. The provision of pharmaceutical drugs to people at risk of overdose has become part of the federal government's strategy for addressing the overdose crisis, and is a stated key priority of governments at all levels. Pharmaceutical opioids such as injectable hydromorphone and injectable diacetylmorphine have an evidence base and have been proven to be cost-effective when used in injectable opioid-assisted treatment (iOAT) programs (Canadian Agency for Drugs Technology in Health, 2020). If safe supply is effectively implemented, the need for more traditional harm reduction measures such as naloxone, supervised consumption and overdose prevention sites, opioid substitution therapy, and drug checking are greatly reduced.

While the federal government may support the concept of safe supply and can make regulatory changes, such as changes to the Criminal Code or exemptions and special access, the provincial governments need to facilitate the practical administration of this health care service to benefit PWUD. For example, in B.C. barriers arise related to drug coverage. Fair Pharmacare, the government program that reimburses British Columbians for the costs of prescribed pharmaceutical drugs, does not cover injectable opioids, such as in the case of injectable hydromorphone (Government of B.C.5) where the coverage is tied to the injectable opioid-assisted treatment iOAT program. Provinces are reluctant to commit significant provincial funding to safe supply initiatives, and continue to rely on federal Substance Use and Addictions Program (SUAP) funding for safe supply pilot projects. Thus far, the will and the collaboration between levels of government needed to successfully implement safe supply appears to be lacking. As a result, safe supply is not part of standard care in addiction medicine.

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, overdose mortality was beginning to fall in many parts of Canada, despite still being much higher than it had been in years prior. B.C. recorded 984 overdose deaths in 2019, which was the first year since 2016 that the province saw less than one thousand overdose deaths (B.C. Coroners Service, 2021). There was a sense that the worst of the overdose crisis was over. As the government started to take their ‘foot off the gas', Health Canada's Opioid Response Team's focus was broadened to include emerging substance use related health concerns including vaping and cannabis. However, as 2020 unfolded and B.C.'s yearly number of overdose deaths almost doubled (1,733) from 2019, there came a realization that any progress made in the overdose crisis was fragile. As pandemic restrictions (such as requiring people to stay inside their homes and be physically distant from other people) impacted harm reduction services (including needle distribution, overdose prevention and supervised consumption sites), B.C.'s overdose prevention slogan “never use alone” became increasingly difficult for many people at risk of overdose during an era of physical distancing.

Additionally, pandemic border restrictions led to large-scale disruptions in the illicit drug supply across Canada, increasing the likelihood of overdose as the supply became increasingly unpredictable (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2021). In Ontario, Ali et al. (2021) studied the impacts of COVID-19 on PWUD, and found “a significant disruption in the substance supply. For many, these changes led to increased use and substitution for toxic and adulterated substances, which ultimately amplified PWUD's risk for experiencing related harms, including overdoses. These findings warrant the need for improved supports and services, as well as accessibility of safe supply programs, take home naloxone kits, and novel approaches to ensure PWUD have the tools necessary to mitigate risk when using substances” (p. 1).

In March 2020, B.C. introduced Risk Mitigation in the Context of Dual Public Health Emergencies guidelines. These clinical guidelines recommended, as a standard of care, legal prescription alternatives to people at risk of overdose including tablet forms of opioids, stimulants, and benzodiazepine drugs as a way to support physical distancing in the illicit drug-using population. While B.C. has some 83,000 people6 who meet the criteria for opioid dependence (Min et al., 2020), just a fraction of these have been able to obtain prescriptions for alternatives to the illicit drug supply under Risk Mitigation prescribing guidelines. The provincial government opted to focus on distribution of oral hydromorphone tablets via Risk Mitigation prescribing, citing cost and availability concerns for injectable hydromorphone [i.e., the drug used in injectable opioid-assisted treatment (iOAT)]. Oral hydromorphone tablets are prescribed off-label, and have not undergone the same rigorous safety and effectiveness testing that injectable opioids have undergone (Nosyk et al., 2021). The lack of evidence and existing safety concerns for oral hydromorphone may deter otherwise willing prescribers, and the province's Risk Mitigation prescriber guidelines omitted relevant health information, thus failing to properly provide informed consent to patients (Westfall and MacDonald, 2020).

Furthermore, despite the context of a pandemic requiring physical distancing, interim findings indicate that some 94 per cent of Risk Mitigation tablet prescriptions were dispensed from pharmacies daily, requiring patients to commute to their pharmacy each day for their prescription (B.C. Centre for Disease Control, 2021). As of May 2021, about 3,899 people (4.7 per cent of people with opioid dependence) had received off-label prescriptions for opioid tablets, mostly oral hydromorphone, but including stimulant and benzodiazepine tablets (Government of B.C., 2021b). However, this figure has recently been revised substantially, with B.C.'s government reporting over 7,000 people with oral hydromorphone prescriptions at some point between March 2020 and December 2021 (Government of B.C., 2022b). This revised number includes one-time prescriptions that occurred at any point within that timeframe, and so the number appears much larger. In February's Budget 2022 (Government of B.C., 2022a), the provincial government reconfirmed that there would be no new funding for safe supply, leading some to wonder how the province intends to address the overdose crisis without substantial funding into this area (Wyton, 2022).

Overall, with very few people with opioid dependence potentially benefiting from these prescriptions, risk mitigation prescriber guidelines are one example of a well-intended yet likely largely ineffective intervention to support PWUD that requires more evaluation. On the other hand, the injectable opioid-assisted treatment (iOAT) programs in B.C. target an even smaller number of people. There is capacity for only approximately 300 people to participate in iOAT programs, reaching 0.36 per cent of B.C.'s 83,000 people with opioid dependence (Min et al., 2020). There is a provincial commitment to increase spots in iOAT programming to 406 (0.49 per cent of the target population) (Government of B.C., 2021b).

In February 2021, during the height of the pandemic, B.C. also stepped up to change the laws and increase the scope of practice of registered nurses and registered psychiatric nurses to allow them to prescribe medications for treatment of opioid use disorder (nurse practitioners have been allowed to prescribe narcotics in B.C. since July 2016) (Government of B.C., 2021f). However, nurses' prescribing privileges are limited to opioid-substitution therapies like methadone and suboxone, and (to date) do not include safe supply drugs. And, as of August 2021, only 47 registered nurses have completed this training (Government of B.C., 2021d). In addition, in July 2021 B.C. recently published their policy on prescribed safe supply (Government of B.C., 2021a), which recommends injectable hydromorphone as well as several other drugs, including pharmaceutical fentanyl. Again, Fair Pharmacare presents an obstacle, only covering injectable hydromorphone in limited circumstances and not covering injectable or inhalable diacetylmorphine (pharmaceutical heroin).

In July 2021, B.C. established a take home prescribed heroin program for 11 program participants at Vancouver's Crosstown Clinic. The program design required participants to attend the program at least two to three times daily, even while pandemic restrictions urged people to stay home (Braich, 2021). To illustrate the lack of cohesion in provincial decision making, this program was abruptly stopped just weeks after starting, with no public explanation (Grochowski, 2021). One program participant said that take home doses helped them care for a significant other with a debilitating illness that requires around the clock medical care. “This is gradually getting worse and worse with her disease and I was so relieved to just know that I had my whole days with her again” (para 15). With the take home program abruptly stopped, the participant was again required to travel multiple hours each day to attend the program, leaving their significant other at risk, “It's terrifying… having to leave her all that time” (Braich, 2021, para 17).

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the federal government has pressured the provincial/territorial governments to step up and take more of a role in managing the overdose crisis, with former Health Minister Hajdu (2020) sending a strong letter in August 2020, in an attempt to encourage more action. While this letter was welcomed by drug advocacy groups, over the past year and a half it has done little to prompt provinces into developing comprehensive and forward-looking drug policy. In 2021, B.C. Chief Coroner Lisa Lapointe said that drug toxicity is now the leading cause of death in B.C. for people aged 19 to 39 and remains the overall leading cause of unnatural death: “This is a significant problem within our province, and the fact we come out here every 6 months and every year and the numbers keep going up and up and up, and no significant changes are being made, it's tremendously frustrating” (Wells, 2021, p. 4). Despite sustained focus on this topic in B.C. over the last six years, drug policy advocates and those who are most impacted by the overdose crisis would say that they have seen very little movement on making lasting change.

Rather, in some provinces, there is a clear political intention to regress drug policy to a more criminalistic approach (Perrin, 2020a). For example, in March 2021, the Alberta Government revised its strategy on substance use, crossing out “harm reduction” and replacing it with a “recovery-oriented approach” (Box 1) and this has led to heightened attention in B.C. where the Ministry of Mental Health and Addictions has also appeared to shift focus to recovery treatments rather than harm reduction. For example, B.C.'s government has committed $500 million to abstinence-based treatment programming (Culbert, 2021), while allocating just $22 million to safe supply programming (Government of B.C., 2021a). Moreover, recent recommendations for a more equitable post-COVID future, such as those proposed by Persaud et al. (2021) in the December 2021 Canadian Medical Association Journal, continue to exclude many of the innovative strategies that are already currently unavailable to many Canadians, including injectable-opioid assisted treatment (iOAT) and safe supply. This shift in approach is concerning to some proponents of drug policy reform because the principles of harm reduction are to support people in the situation they are in (reality), not to necessarily assume they must stop using drugs (an imagined future). Focusing solely on recovery and rehabilitation (rather than the full continuum of interventions) is a more traditional approach to drug policy—and one that has been largely unsuccessful.

The far-reaching impacts of COVID-19 affect every single individual in Canada, and as a result, there is an appetite for any program or strategy that will help to eradicate the virus and get the world back to normal. While there may be some criticism around various programs—the length they are available, the amount of support, etc.—the public feels very little need to be involved in pandemic programs and planning. Ultimately, as noted above, most drug (opioid) policies and programs receive “drive by” (pilot project) funding and are not guaranteed longevity, resulting in moments of action that are not sustained and often are retracted when funding ends.

In Canada, COVID-19 messaging has included mitigation strategies, such as appropriate hand and face hygiene practices, social/physical distancing policies including closing non-essential business and public spaces, restrictions and limitations on visitation in hospitals and long-term care facilities, and travel restrictions (Government of Canada, 2022a). More recently, upon acknowledging a shift in the science that “COVID is airborne,” strategies also include a focus on indoor air quality and ventilation (Government of Canada, 2021c). Effective and transparent communication of evolving information related to COVID-19 is needed to ensure the public understands how and why to adapt their behaviors to bolster individual, community, and public safety (Betsch, 2020; Sauer et al., 2021).

From the beginning of Canada's pandemic in March 2020, speaking from in front of the Prime Minister's residence, the Prime Minister took a sober approach, repeatedly warning Canadians to “Go Home and Stay Home”. As noted above, in B.C., messaging around COVID-19 was primarily delivered by Dr. Bonnie Henry and Minister Adrian Dix. Near the beginning of the pandemic, Dr. Henry coined her famous line, “Be Kind, Be Calm, Be Safe” (Zussman, 2020a; Henry and Henry, 2021). This emotional message was strong and clear, and was picked up by British Columbians and others as an expression that encapsulated the key momentum that most governments are looking for in a time of crisis: unity and compassion. A second feature of COVID-19 messaging in B.C. has been the daily (Monday to Friday) reporting of new cases and deaths. Along with numbers of deaths reported, each day officials have added, “our condolences are with the family, friends and caregivers of these people as well as with the loved ones of all of those who have died as a result of COVID-19 (Dix, 2022).

One of the key communication strategies we have seen emerge throughout the pandemic is the use of messaging in the form of catch phrases to try and ensure an idea becomes embedded in the psyche of the population (Table 4). This is a tried-and-true way of delivering key messages, although it does not always work or catch on in the way it has been imagined. One of the best health campaigns that effectively used a catchy idiom was for EpiPens “blue to the sky, orange to the thigh” (Pfizer Canada, 2017). Even for those individuals who lack familiarity with EpiPens, this is an easy and memorable way to know what to do if you are faced with a situation where someone is having a severe anaphylactic response. However, we have also seen these types of health catch phrases fail spectacularly, such as the unpopular anti-smoking campaign: “Put it out before it puts you out” (World Health Organization Tobacco Free Initiative, 1999).

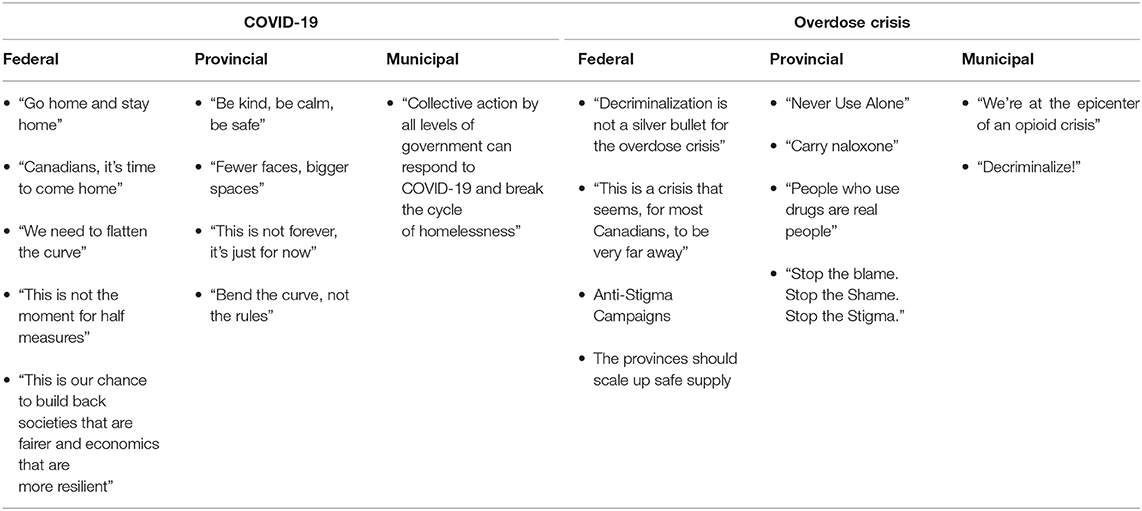

Table 4. What messaging has helped/hindered the information loop result in desired behavioral changes?

With respect to media reporting of the overdose crisis, no catchy or cute phrases, or respectful and compassionate phrases, have seared the minds of the public to date. Rather, news producers inflate the dramatic element of stories they perceive as ‘newsworthy' (Young, 2009), which draws the public's attention in ways that strengthen social orthodoxies (Cohen, 2011; Reed, 2015). A common framing characteristic of media reporting of opioid use and dependence is the use of hyperbole that dramatizes or sensationalizes the issue (Morris, 2005). Quan et al. (2020) examined Globe and Mail headlines such as “Drugs ravage picture-perfect community” and “We have opened Pandora's box—it's going to haunt us”. Descriptions such as “teenage girls would do housework in their underwear in return for pills”, “abusers cut up the [fentanyl] patches and eat the pieces” and “thefts and break-and-enters so they [PWUD] can feed their habits” demonstrate how the issue is being narrated for the public. Such framing may contribute to the construction of misleading and harmful stereotypes toward people who use opioids. In her (Lupton, 2015) article The pedagogy of disgust: the ethical, moral and political implications of using disgust in public health campaigns, Deborah Lupton argues that framing an issue in this way not only can have significant ethical, moral and political implications, but can also reinforce stigmatization and discrimination against individuals and groups who are positioned as disgusting. “It's like being put on an ice floe and shoved away, and now we have to go out on our own and try and figure things out” says one individual's experience with stigma and being denied healthcare (Antoniou et al., 2019, p. 19).

While some media outlets in Canada (such as the Georgia Strait or the Globe and Mail) occasionally focus on the overdose crisis (particularly when there is a significant change in policy or the coroner announces the most recent tally of overdose deaths), by and large coverage of the overdose crisis is random and inconsistent in terms of messaging. There is certainly no daily highlighting of those who have succumbed to an overdose in the same way there has been with COVID-19, leaving the public to make up their own messages and interpret the meaning of these deaths.

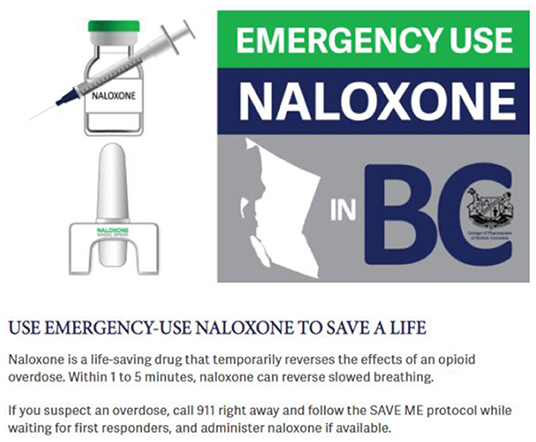

Under the umbrella of harm reduction, public health experts have developed several messages targeted to PWUD, most notably “do not use alone” and “carry naloxone” (Figure 2). While these are common slogans aimed at PWUD, there is little evidence regarding whether they are effective for the target audience. American researchers (Winiker et al., 2020) did in-depth interviews of young drug users in 2015/2016 and found that young PWUD inject alone for a variety of reasons, and thus “don't use alone” messages, while necessary, may not be sufficient given the complex realities of people who use injection practices. Although there has been increased uptake in PWUD carrying naloxone in high-risk situations (e.g., concentrated in an area like Vancouver's Downtown Eastside), such messaging has not had the same uptake within community settings. Naloxone is free and easy to access. There might have been missed opportunities to target messaging to groups, such as parents of teens/young adults or people who host parties that include recreational drug use, about why it is a good idea to keep naloxone kits on hand and understand the signs of an overdose.

Figure 2. British Columbia “Carry Naloxone” Campaign. Source: College of Pharmacists of British Columbia.7

McGinty et al. (2019) studied how the U.S. media has covered the overdose crisis from 2013 to 2017, in comparison to the previous period 1998 to 2012. They found that pre-2013 coverage primarily focused on criminal justice-oriented solutions, whereas in the years following, there was an increasing trend toward treatment (33 per cent of news stories), harm reduction (30 per cent), prevention (24 per cent), medication treatment for opioid use disorder (9 per cent) and safe consumption sites/needle exchange sites (less than 5 per cent) (McGinty et al., 2019). These results are comparable to the B.C. setting. While this trend is positive, it is still insufficient to provide enough information for any level of government to accurately state that they are reaching their target audience. To add further complexity, most governments seem to not be entirely sure who their target audience is.

In B.C., some of the strongest messaging throughout the overdose crisis has arguably been given by Chief Coroner, Lisa LaPointe, and Vancouver Mayor, Kennedy Stewart. During COVID-19, the mayor's press conferences always included discussion of how COVID-19 would impact the challenged drug-using population of Vancouver's Downtown Eastside (Bernard and Steacy, 2020). For example, in April 2021, Kennedy implored, “Five years into this public health emergency and we are still seeing record numbers of overdose deaths, not just in our city but across the province. Today serves as a grim wake up call, a moment for us to say ‘enough is enough' and to resolve to put an end to a tragic failure in policy that has needlessly cost too many of our neighbors their lives. Decriminalization, safe supply, and a ferocious campaign to save lives and end this crisis is the only option” (City of Vancouver, 2021, para 2). These types of social justice calls to action have been repeated often. In January 2022, Chief Coroner LaPointe lamented, “This is a huge crisis—it's hard to think of anything else that could happen in this province that resulted in the deaths of six or seven people every single day without a massive response. We just haven't seen that. We have not seen a response commensurate with the size of this crisis, with so many people dying every day. We know what a response to a public health emergency looks like because we have seen it with COVID—a provincial response, provincial testing, provincial vaccination sites and provincial data. We have not seen that” (Mulgrew, 2022).

In communications, any type of messaging can be boosted or thwarted depending on the person delivering the message. While Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has remained consistent, strong and on message regarding both COVID-19 and the overdose crisis, on several occasions B.C. Premier John Horgan has had to “walk back” well-intentioned words when he moves away from his approved messaging. For example, on March 15, 2021, the Premier stated his opinion that young people pay less attention to news conferences, and he went on to say directly to them in regard to spread of COVID-19, “I'm appealing to young people to curtail your social activity… my appeal to you is: do not blow this for the rest of us. Do not blow this for your parents and your neighbors and others who have been working really, really hard, making significant sacrifices so we can get good outcomes for everybody” (Judd, 2021b, para 6). The response from young people was swift, strong, and negative. Indeed, the premier has made similar faux pas regarding the overdose crisis, such as on July 17, 2020 when Horgan seemingly directly compared the nature of the overdose crisis to COVID-19: “Those are choices initially and then they become dependencies. Once people make those choices, they are no longer in a position to stop making those choices without intervention” (Kearney, 2020, para 7). Horgan's comments (whether taken out of context or not) signal why the overdose crisis has not received the type of muscular response summoned for the coronavirus—it seems to be acceptable to assume that those dying of an overdose are somehow “morally culpable” (as Lupton, 2015 argues above), rather than recognizing substance use as a socially constructed health and social justice issue.

Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, the B.C. government has continuously stated that they are providing as much information as possible to ensure the public is knowledgeable about the COVID-19 situation. According to Minister Dix, “The key part is giving people all the information, all the time. Letting people know what we know and that reinforces confidence. We were first to do our modeling, we put it out there” (Zussman, 2020b, para 17). Although the Minister may well believe what he is saying and aim to protect people's privacy, the media itself has frequently complained that other jurisdictions receive much more detailed and relevant information about cases, hospitalization, and deaths, with regional and sometimes “neighborhood” statistics and race/ethnicity data, etc. (McElroy, 2021). In contrast, information about the overdose crisis is not forthcoming. After public announcements for new programming (such as outlined in Table 3), there is often a lengthy delay before implementation. For instance, more provincial funding for overdose prevention sites (Zussman, 2020a), expanded prescribing privileges for nurses (including safe supply) (Ghoussoub, 2020), and an expansion of risk mitigation prescribing (Winter, 2020) were all promised during the summer of 2020 in B.C. However, the implementation of most of these initiatives were delayed by the fall 2020 provincial election, and progress on their implementation is slow, well over a year later.

Public health messaging typically targets “mainstream” society comprised of more powerful social groups. It is well-accepted that COVID-19 has contributed an additional layer of complexity for populations marginalized by society, such as people experiencing homelessness, PWUD, or those suffering from mental health challenges. We know that PWUD are among systematically disadvantaged groups at an increased risk of poor outcomes from COVID-19, often because of limited personal resources, inadequate and unstable housing, sharing of substance practices, and higher rates of chronic disease (Flood et al., 2020; Public Health Agency of Canada, 2021d). COVID-19 has had a negative impact on these populations, yet this is a discussion that has not been had with any degree of significance with any level of government. Drug policy advocates argue that PWUD are often “invisible” when decisions are being made about how to manage a current healthcare challenge. This invisibility is ethically problematic because members of disadvantaged groups are particularly vulnerable to being treated less fairly and less equitably than other members of society, and are thus further marginalized from “social goods, such as rights, opportunities and power” (Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, and Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, 2018, p. 8). We submit that PWUD continue to be ‘unheard' by decision makers, as efforts by PWUD activists to compel the provincial government to expand access to safe supply and other innovative strategies have been ongoing since 2018 (Lupick, 2018).

To be sure, the strategy and challenges involved in communications during a global pandemic are substantial. The uncertainty of a novel virus means that “facts” and “science” are changing, resulting in mixed messages, high levels of misinformation and opportunities for anti-science disinformation. COVID-19's impact on entire populations around the globe has been profound, with ongoing changes for individuals, small and large institutions alike. However, it is critical to emphasize the role of sociopolitical context (Kenny et al., 2010; Rodney, 2013); meaning, understanding that individuals and groups are differentially situated and disproportionally impacted, with health disparities and different abilities to navigate this shifting pandemic landscape. And as many have experienced, this multi-year global pandemic has been an emotional and difficult period, involving fear, anxiety, loss, and anger. Despite this array of challenges, we argue that constructing the narrative around a communicable disease outbreak such as COVID-19 is easier than for the overdose crisis, in large part because COVID-19 impacts every person whereas the overdose crisis is perceived to have a narrow impact on the population. Unfortunately, the inconsistent messaging and anti-stigma campaigns around drug use that have been produced to date have resulted in limited public awareness of the overdose crisis and its fallout. It is unclear if messages to PWUD about life-saving interventions such as “don't use alone” or “carry naloxone” are legitimate educational pieces, or if the drug-using community would have realized the benefits of using drugs with people they trust and of having a plan to respond to an overdose (such as ensuring naloxone was on hand).

In British Columbia, we have learned that as a society it has been relatively easy to modify the attitudes of the public regarding COVID-19. At the time of writing, the pandemic is ongoing. Most British Columbians continue to adhere to the ever-changing rules without significant complaint, accept the messages from our leaders, and believe that we will have greater success working together to achieve immunity and protect the vulnerable. In what follows, we examine this complex issue through changes in attitude, knowledge, skills, behavior, and society that could result in minimizing and mitigating the impact of the overdose crisis in B.C. safely, calmly, and with kindness.

1) Modification of Attitudes

As we consider how individuals view the pandemic and the messages that have been offered from leaders, in contrast with the overdose crisis, there are some obvious gaps in communication. Why do we, the public, not have regular updates about a crisis that has killed far more people in B.C. than COVID-19 (per Figure 1 above)? Would public perception be changed if we had routine news conferences that listed the number of individuals who passed from overdose, and offered our condolences to the friends and family of those people as well as to the loved ones of all of those who have died as a result of overdose? Could we use the existing COVID-19 news conferences to also speak in a good and respectful way about deaths and hospitalizations (and other relevant indicators such as police responses, other first-responder expenses, resuscitations, ambulance trips, emergency room costs, hospital admissions (Mulgrew, 2022)) due to overdose? The reality is that by talking about COVID-19 frequently and consistently, we have brought the pandemic into every part of our lives. In contrast, the social discomfort talking about addiction together with infrequent communication from government suggests that we have not normalized the overdose crisis to the point that people want (or demand) to know what is happening, and why. Instead, we turned away and normalized skyrocketing rates of overdose death. Therefore, government and public health leaders are missing an enormous opportunity to educate with compassion and raise awareness—and that might be the public campaign we need the most to slow down the number of deaths and bring the crisis to a close.

One of the concerns that is raised by the lack of continuity in sharing COVID-19 outcomes (deaths) along with overdose deaths is that our leadership appears to convey a “compassion gap” by acknowledging their sorrow at the loss of every single COVID-19 victim on a daily basis, but reporting overdose statistics once per quarter. Political leaders expressing opinions that “one is a choice” goes against the public health understanding of drug use as a health issue underpinned by complex social and structural determinants, and results in the compassion gap conveyed to all British Columbians. COVID-19 deaths, particularly the deaths of fully vaccinated people, are not only elevated and solemnized, but they are also portrayed as more important than overdose deaths. This is a direct result of the stigma we see throughout every aspect of society when it comes to PWUD. Stigmatizing attitudes from the government and their fears of negative public perception inhibit greater access to the more innovative harm reduction strategies such as safe supply. According to a 2018 internal briefing note, prepared by the Office of the Provincial Health Officer, B.C.'s government feared negative public backlash for distributing government supplied drugs to people at risk of overdose, noting that greater public acceptance for non-medicinal drug use was required (Hainsworth, 2021).

2) Acquisition of Knowledge/Skills

In Dr. Bonnie Henry's (Henry and Henry, 2021) book Be Kind, Be Calm, Be Safe about her first few months grappling with the COVID-19 pandemic, Henry states, “…although we're all in the same storm, we're certainly not all in the same boat” (p. 198). Whereas, the majority of the B.C. population have managed their pandemic using government supports, the Internet, social services, their employment network, their family physician, etc., many people who experience marginalization struggle to access these day-to-day opportunities. In the middle of the pandemic crisis, where the focus has to be on providing the most support to the most people, PWUD continue to fall through the cracks, or fall even further. It is difficult to physically distance if you are living in a shelter; it is challenging to home school your children if you are a single parent working the hours of nine to five; it is impossible to apply for government grant programs if you have no tax history or identification; it is confusing to access forms and services if English is not your first language or if you have low computer literacy; and it is shameful to access what you need to ensure a safe drug supply in your middle income home if you are a user but do not want your partner or boss or neighbors to know. These are just some of the challenges that are faced by a significant number of British Columbians and the onus is on government to produce strong, thoughtful discussion and messaging—narrative—for everyone.

The reality is, while there are people who use drugs at every level of society, and there are individuals who have COVID-19 at every level of society, the people who are the most at risk in terms of social and structural determinants of health (e.g., economic and social policies, politics, and social identity stigmas such as drug use stigma, racism, sexual stigma, gender identity stigma, ableism) are those who have a lower opportunity to access social determinants of help. The ability to navigate government and seek social programs, increases greatly as social position is elevated. Like health literacy, pandemic literacy is easier for those who have a stable job, access to information, good education, and access to internet and media—all of these things lead to a much higher likelihood that you will be able to access the services you need, when you need them. Unless we make a dedicated and concerted effort to improve the social and structural determinants of health for everyone, and unless we can actively get the right information into the right hands, individuals who experience marginalization (including some PWUD) will not thrive or survive as we move through similar situations in the future.

3) Behavioral Change

The pandemic has caused significant stress and mental health issues for a broad segment of the population. We are just starting to understand how personal dynamics, and relationships have changed. We still do not see the downstream ramifications. Will we ever return to a time when we did not have masks and hand sanitizer in our pockets? Will we travel the world with the same ease and comfort? Will every sneeze or sniffle result in panic?

After 9/11, many turban-wearing and dark-skinned individuals reported that they were treated with suspicion when getting on airplanes or going about their daily business. Racism was rampant, more visible, and immediate. Throughout COVID-19 many jurisdictions have seen increased racism toward individuals who present as Asian because of suggestions that have been raised such that China intentionally released the virus. These are unfortunate scenarios, but are not as fully embedded in the consciousness of the population as stigma around drug use, which is often centered around the construct that someone has had a “choice” to start using, and if they just stopped and got a job, they would be fine. With very little opportunity to counter decades of “the War on Drugs” mentality it is extremely challenging for proponents of drug policy reform to raise their own profile and to shift public opinion to a world where it seems appropriate, urgent, and necessary to support harm-reduction practices.

In September 2021, Canada had a federal election, during which the pandemic was front and center for several reasons. The success of the federal government's pandemic plan and management was a key factor during the debates and discussions, followed closely by the media, and ultimately became a point of decision for many Canadian voters. Whether overt (the leader supports/does not support masking, mandatory vaccinations or a vaccine passport), or subtle (the leader has generally done a good job in putting forward a plan for COVID-19 management, is sympathetic to those who are impacted, should not have called an election during the pandemic), the vote was influenced by the public perception of how the pandemic has been handled. On the other hand, despite overdose being a significant public health risk and described by Health Canada as a crisis (Government of Canada, 2019; Special Advisory Committee on the Epidemic of Opioid Overdoses, 2021), the overdose crisis did not appear to be on the radar during this election campaign, and had very little impact on the electorate. Aside from a small handful of individuals who are avid advocates for drug policy reform, the overdose crisis received almost no air-time with the Canadian public.

If there was truly the will amongst our political leaders in Canada to change the direction of the overdose crisis, one would think that an election campaign, which is arguably one of the best times for leaders to share ideas and seek input on how to “do better” would be the time when an issue such as the overdose crisis would be front and center (albeit perhaps not an election held during a pandemic). Importantly, if there is an intent to change how society perceives the overdose crisis, and if we want to increase the commitment of Canadians to ending both the COVID-19 and the overdose public health emergencies, we need our leaders to talk about them both with conviction and to generate the creativity and ideas we have seen deployed around COVID-19, used to consider how to manage the overdose crisis.

4) Societal Change

COVID-19 impacts everyone, and we recognize that our laws, norms, and the habits of Canada's population and society have changed significantly since the pandemic began. While there has been polarization of ideals and an increased tendency to politicize interventions, such as mask wearing and vaccine mandates (with accompanying reflection about that politicization), strong threads of safety and solidarity have been embraced and could endure in many aspects of society. Whereas, 10 years ago, seeing someone wearing a face mask on public transit in Canada was strange, it will probably not be strange to see many individuals embracing a mask in the future. Whereas, before social networks and gatherings were large and freeform, there appears to be a rising inclination to be careful and thoughtful about how we interact.

People who are struggling to manage the social and structural determinants of health are far less likely to embrace these societal changes because they often represent a financial or personal hardship that is outside of the experience they had already managed to adjust to. If you were a person who used drugs prior to the pandemic, you are probably having to learn new methods to secure what you need and ensure your safety. If you were homeless prior to the pandemic, you are now more likely to find locked doors, inaccessible bathrooms, and limited options for social distancing in shelters. We are hopeful that it is possible that in Canada, our laws, economic and social policies, politics, norms, and the attitudes and habits of the population and society can continue to evolve to become more effective and more compassionate to people who use drugs.

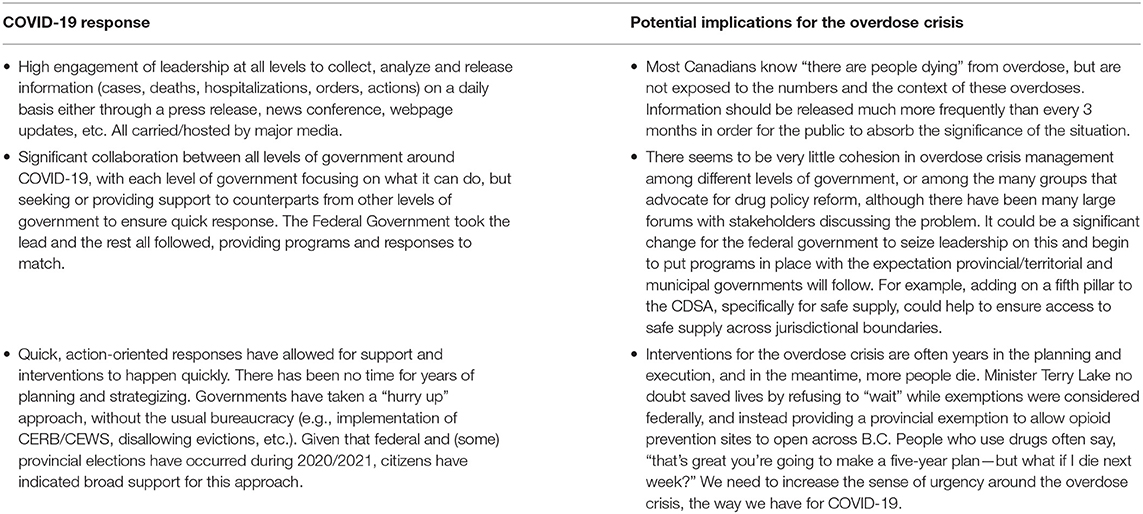

In this paper, we have provided an analysis of how Canadian policymakers have managed the COVID-19 pandemic thus far, and offer potential implications for the ongoing overdose crisis. COVID-19 has shown us: 1) that we do have strong public institutions that are able to respond to crises and support Canadians when they need them most, and 2) what is possible when we work together and focus on achieving our end results. We have argued that the pandemic has received immediate and strong support, while the overdose crisis continues and grows, with periodic attempts at intervention but very little cohesive direction. To see the change needed, in Table 5 we summarize the key lessons we have learned during COVID-19 that would go a long way toward mitigating the overdose crisis:

Table 5. Lessons learned from the COVID-19 pandemic and potential implications for the overdose crisis.

A review of the responses, by every level of government in Canada, to the COVID-19 and the overdose public health emergencies that have been declared in British Columbia demonstrates that there continues to be a wide gap in the types and impacts of the social and structural supports that have been delivered to date. If we want to prevent future deaths from the worsening overdose crisis, strong interventions are required from policymakers, stakeholders, and the community to establish permanent solutions to this complex problem.

While this paper highlights some of the challenges facing the health care system in Canada, our analysis is limited to one province, that, out of necessity, could arguably be among the most progressive in this country when it comes to managing the overdose crisis. While we have made every effort to thoroughly review the B.C. situation, both the COVID-19 pandemic and the overdose crisis are ongoing and continue to impact society, systems and individuals. Policy for both crises continues to change, sometimes on a daily basis, making it challenging to compare and contrast across provinces, particularly when both crises have significant political overtones. Future research into how these two epidemics have become politicized, the impact social identity stigmas have had on both, and the challenges of implementing and communicating policy “on the fly” will be an important contribution to understanding and mitigating the poor outcomes that individuals and groups face.

As a country, Canadians need to be better at building the types of supports they have created to manage the COVID-19 crisis in order to also support individuals who are immersed in the overdose crisis. Government has reacted to COVID-19 with urgency, with determination, and with a clear path for how they want to move forward. All levels of government have collaborated together, no matter their political stripes, to do the best thing for the most people. Vaccines happened quickly, mandates were put in place with strength, and the public has mostly swayed to the side of support for the hard work health care leaders and public health has done.