- 1School of Public Health Sciences, University of Waterloo, Waterloo, ON, Canada

- 2Centre for Sustainable Food Systems, Wilfrid Laurier University, Waterloo, ON, Canada

Access to and availability of food harvested from the land (called traditional food, country food, or wild food) are critical to food security and food sovereignty of Indigenous People. These foods can be particularly difficult to access for those living in urban environments. We ask: what policies are involved in the regulation of traditional/country foods and how do these policies affect access to traditional/country food for Indigenous Peoples living in urban centers? Which policies act as barriers? This paper provides a comparative policy analysis of wild food policies across Ontario, the Northwest Territories (NWT), and the Yukon Territory, Canada, by examining and making comparisons between various pieces of legislation, such as fish and wildlife acts, hunting regulations, food premises legislation, and meat inspection regulations. We provide examples of how some programs serving Indigenous Peoples have managed to provide wild foods, using creative ways to operate within the existing system. While there is overwhelming evidence that traditional/country food plays a critical role for the health and well-being of Indigenous Peoples within Canada, Indigenous food systems are often undermined by provincial and territorial wild food policies. Provinces like Ontario with more restrictive policies may be able to learn from the policies in the Territories. We found that on a system level, there are significant constraints on the accessibility of wild foods in urban spaces because the regulatory food environment is designed to manage a colonial market-based system that devalues Indigenous values of sharing and reciprocity and Indigenous food systems, particularly for traditional/country foods. Dismantling the barriers to traditional/country food access in that system can be an important way forward.

Introduction

Globally, food systems have come under threat from the impacts of climate change, industrialization, environmental degradation, as well as new threats such as the COVID-19 pandemic (FAO, 2021). These impacts have disproportionately affected Indigenous Peoples ability to access their lands for food and water sources (United Nations, 2007; CCA, 2014). There is a growing effort to increase knowledge and access to local food resources for Indigenous Peoples (Pal et al., 2013). The United Nations' Millennium Development goals highlight important issues impacting Indigenous groups, such as: sustainable development, reducing hunger, the empowerment of women, and increasing access to safe and nutritious foods. The harvesting, preparation, and consumption of traditional/country foods1 remains deeply embedded in the familial, cultural, and social fabric of communities is an essential component of the social and cultural well-being of Indigenous Peoples (Pal et al., 2013; CCA, 2014). Addressing some of these issues the Declaration of Atitlán, drafted at the First Indigenous Peoples' Global Consultation on the Right to Food, states that the “denial of the right to food for Indigenous Peoples is a denial of their collective Indigenous existence, not only denying their physical survival, but also their social organization, cultures, traditions, languages, spirituality, sovereignty, and total identity” (United Nations, 2002).

In Canada issues of food insecurity and food sovereignty for Indigenous Peoples are extremely pressing. Indigenous Peoples face disproportionate rates of food insecurity, six times higher than the national average and “represent the highest documented food insecurity rate for any aboriginal population in a developed country” (De Schutter, 2012). Half (49.2%) of First Nations households in Canada are food insecure (FNIGC, 2018) and data from the 2017/2018 Canadian Community Health Survey showed 21.6% of households in the Northwest Territories (NWT), and 16.9% in the Yukon as food insecure (Tarasuk and Mitchell, 2020). Investigations of Indigenous food security and sovereignty in Canada have focused primarily on First Nations and Inuit communities, however this picture is much more complicated. Common misconceptions suggest the boundaries between urban and community spaces are static, this is not the case. Food, both traditional/country and market-based flow between communities and urban spaces and very little attention has been paid to these movements.

Access to traditional/country foods for Indigenous Peoples in urban contexts promotes health and wellbeing, and there exists a strong desire to eat these important foods (Lardeau et al., 2011; Elliott et al., 2012; Skinner et al., 2016). Yet, there is evidence that a move to an urban center leads to dietary changes that includes the increasing consumption of both fast foods and fruits and vegetables, and a decrease in the intake of traditional/country foods (Brown et al., 2008). Access to traditional/country foods may be problematic for urban Indigenous Peoples (Baskin et al., 2008; Elliott et al., 2012) and food sharing of both traditional/country and store-bought food is less prevalent than within small community settings (Brown et al., 2008). Reasons cited include the distance from their home community, being disconnected with family still living in their community, and the emphasis on monetary culture in the city (Brown et al., 2008; Elliott et al., 2012). Despite these reasons, there is research that suggests Indigenous Peoples can overcome urban challenges to access traditional/country food through grass-roots collaboration with local partners (Cidro et al., 2015) and Indigenous cultural revitalization.

As we describe in this paper the acts, regulations, and legislation regarding wild food in three provinces/territories, we show that government policy continues to shape access to traditional/country food for Indigenous Peoples living in urban settings.

Prior to the establishment of wildlife policies by the Canadian governments, Treaties enacted by the Crown were the only policy texts implicating Indigenous Peoples access to wildlife (CIRNAC, 2020a,b). Canadian policies pertaining to wildlife have been in existence for more than a century, with the driving rationale for these policies being to preserve and conserve resources (Sandlos, 2011). Historically the use of federal and provincial/territorial wildlife policies, have been used to assimilate and discriminate against Indigenous Peoples (Moss and Gardner-O'Toole, 1991). The use of licensing systems to push institutional wildlife conservation goals ahead of Indigenous treaty rights have become ubiquitous across Canada (Passelac-Ross, 2006). In northern Ontario, Gardner and Tsuji (2014) found that the form to apply for a federal Possessions and Acquisition License was only available in English and French. This created a barrier for community members who predominately spoke Cree (Gardner and Tsuji, 2014). Furthermore, the process to acquire a Possessions and Acquisition License involves a paid course and licensing fees, which compound with the additional costs required to hunt (Pal et al., 2013; Gardner and Tsuji, 2014; Leibovitch Randazzo and Robidoux, 2018). These courses were developed with settler colonial perspectives, ignoring any Indigenous knowledge or practices. Hunting on the land is already a challenging activity, with the inherent challenges of finding an animal, the high upfront costs of fuel, equipment, and other harvesting supplies, and the growing number of safety risks through changes to land due to changes in the climate (Ford et al., 2006; CCA, 2014; Spring et al., 2018; NIECB, 2019).

Jurisdictional Complexities

The rights of Indigenous Peoples to harvest wildlife on their traditional lands are entrenched in Treaties and under Section 35 of the Constitution. However, the entrenchment of rights within the constitution alone does not provide an explanation of how harvesting activities can be controlled by governments or how Indigenous harvesting rights are applied in urban settings. This complexity is further compounded by the nation-to-nation agreements that were established prior to the constitution, better known as treaties.

The powers of both levels of government in Canada are entrenched within the Constitution Act of 1982 (Beaudoin, 2019). The federal government's major responsibilities are national defense, currency, and good governance (Beaudoin, 2019). In addition, the federal government is responsible for matters on Indigenous reserves, such as implementing social services and coordinating healthcare (Lavoie et al., 2011; Kerr and Kwasniak, 2014). On the other hand, provincial and territorial governments are responsible for managing lands and resources, hospitals, and civil rights (Beaudoin, 2019). The designation of jurisdiction over wildlife is not explicitly covered in the Constitution, rather it was arbitrarily transferred to the provinces through the Natural Resource Transfer Agreements in the 1930s, as wildlife was simply understood as a resource (Kerr and Kwasniak, 2014). A challenge with this division of governing responsibility is that accessing traditional/country foods in an urban setting intersects both areas of jurisdiction, as food, health, culture, and the lands are intrinsically linked for Indigenous Peoples (CCA, 2014; Halseth, 2015).

Our extended team has been working on a larger Canadian study that examines networks of food sharing and how government and organizations have shaped and informed food economies, policies, and access to traditional/country food in urban, and rural/remote settings (Johnston and Spring, 2021; Robin et al., 2021; Phillipps et al., 2022). A component of this project is to explore the policies involved in the regulation of traditional/country food harvested from the land and the impacts on access to these foods in urban environments, particularly for Indigenous Peoples (CCA, 2014). This paper provides a comparative policy analysis of traditional/country food policies across Ontario, the NWT, and the Yukon Territory (Figure 1), Canada, by examining and comparing various acts and regulations, such as wildlife acts, hunting regulations, food premises legislation, and meat inspection regulations. The single province and two territories within this paper were strategically chosen to assist in providing policy context for our community partners and their urban and rural/remote focused research projects throughout northern Ontario, NWT, and Yukon.

To do this, we ask the following research questions: (1) What policies are involved in the regulation of traditional/country foods and how do these policies affect access to traditional/country food for Indigenous people living in urban centers? (2) Which policies act as barriers? We classify a barrier as any part of a policy that inhibits an Indigenous person from accessing traditional/country foods.

Selection of Policies and Method of Analysis

This paper is exploratory in nature and does not utilize structured analysis of the policies surrounding access to traditional/country food in Ontario, NWT, and Yukon. Rather, this paper has taken a practical approach to identify the policies with authority over access to traditional/country food within the three provincial/territorial jurisdictions included in this analysis.

Search for and Screening of Legislated Acts and Regulations

With the establishment of the Montreal Declaration on Free Access to Law in 2002, participating legal information institutes committed to promoting access to public legal information through the internet (CanLII2). This resulted in organizations like the Canadian Legal Information Institute (CanLII, see text footnote 2) to provide the public with access to court cases, statutes, and bills. The establishment of this declaration encouraged governments across Canada to post their legislated bills and statutes on their respective government websites. A legislated act is a statute that was introduced to parliament and received assent from the House of Commons, The Senate and The Crown to become law (Health Canada, 2006). A legislated regulation is made authority under an Act, which defines the application of enforcement of the statute (Health Canada, 2006).

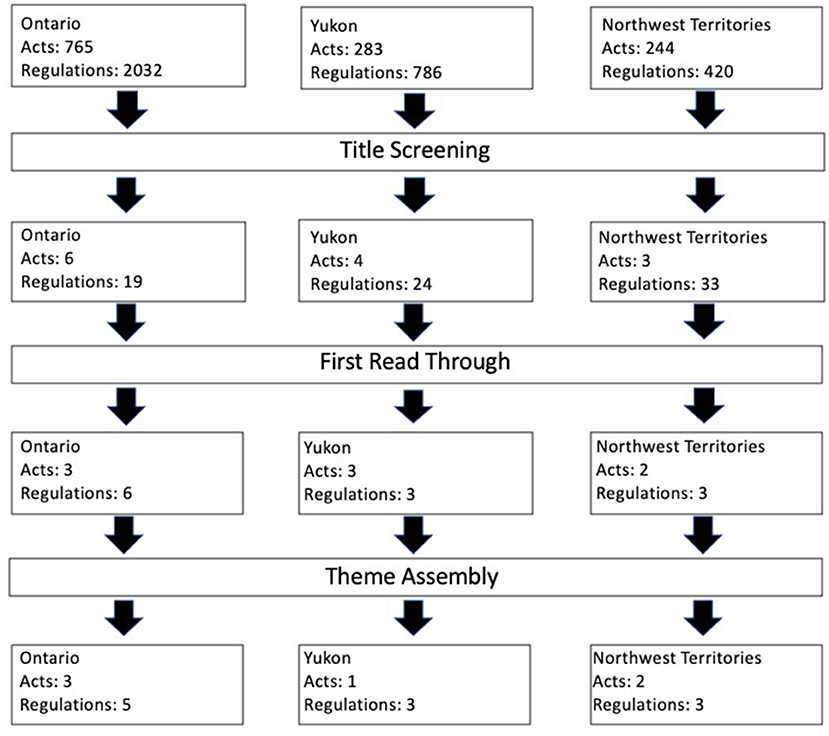

This paper utilized a title screening process (see Figure 2) of provincial (Ontario) and territorial (NWT and Yukon) government websites to identify all the legislated acts and regulations pertaining to wild food that were relevant for this study. Policy reference pages on federal agencies' websites were consulted to identify the relevant legislated acts and regulations from the federal government. For the provincial, territorial, and federal pages, every policy listed on the respective government agency website was included within the title screening process. This resulted in a total of 1,292 legislated acts and 3,238 legislated regulations between the three jurisdictions being included into the title screening. For the screening process, if a legislated act or regulation had oversight over traditional/country food, with regard to how it is acquired, processed, or served, it was considered relevant and retained. Whether or not an act or regulation was deemed relevant was left to the discretion of the researchers, whom have previous experience and background knowledge on Indigenous food insecurity, food systems, and policy. Due to the desired specificity and structure of legislation texts, simply reading an act or regulation's title was enough to screen and gauge if a title should be included. If a policy was ambiguous or suspected to have any relevance to the research questions, it was passed through this initial title screening to be reviewed and examined at the next step. After the first read through (see Figure 2), six legislated acts and 11 regulations were retained and included in the analysis.

Thematic Policy Analysis

If a section or subsection was found to have any relevance to any of the identified themes, these sections were copied and pasted into a separate document for tracking. This process was essentially the coding stage of the analysis, where the sections of policies from the three jurisdictions were organized into similar groupings. Drawing from the work of Braun and Clarke (2006) on thematic analysis, the grouping of codes was organized into three themes that captured the different aspects of policies that can be considered by Indigenous Peoples to access traditional/country food in an urban center (Braun and Clarke, 2006). The first theme was Wildlife and Hunting, which included all sections of policy that pertained to hunting, wildlife conservation, and wildlife management policy mechanisms. The second theme was Meat Processing, which included policies on abattoirs, wild game processing and meat inspection protocols. The third and final theme was Food Establishments, which included where wild game can be served, the requirements to process meat in a butcher shop, and the protocols to have charitable events that serve wild game meat. The results of this analysis are organized in the typical settler view of the supply chain for meat, where an animal is killed, processed, and then sold to the consumer.

Jurisdiction Profiles

Jurisdiction profiles have been established to situate the policies in a context that allows for a comparison between the three jurisdictions included in this article. In addition, as this study will highlight the importance of geography and place, as what lands a person plays a significant role on which policies apply in each situation. By establishing jurisdiction profiles, the context needed to inform the interpretation of a policy is constructed, allowing for a comparison to be made between jurisdictions. Each policy will be assumed to apply to an Indigenous person in each respective jurisdiction profile. We use the example of moose meat to illustrate each jurisdiction profile, where each hypothetical Indigenous harvester is trying to acquire moose meat within the jurisdiction of their provincial/territorial policies. We chose moose as different moose subspecies can be found within all three jurisdictions and are regularly harvested by Indigenous Peoples (Schuster et al., 2011; Skinner et al., 2013; Halseth, 2015). While there are no endangered species statutes or international conservation agreements that apply to the species of moose within the jurisdictions in this analysis, these types of policies often must be taken into consideration when hunting other species, such as caribou (Parlee and Wray, 2016). It is important to note that there are other types of traditional/country food such as fauna or fish that are regularly consumed by Indigenous Peoples (CCA, 2014; Halseth, 2015). However, expanding the search to include the policies that pertain to plants or oceans and fisheries was not feasible within the scope of this paper.

This paper utilizes John Weeks' definition of urban, which is “a placed-based characteristic that incorporates elements of population density, social, and economic organization, and the transformation of the natural environment into a built environment” (Weeks, 2010). In Ontario, the jurisdiction profile is located in Toronto, as the city has the largest Indigenous population in Canada, with roughly 47,000 people as of 2016 (City of Toronto3; Ministry of Indigenous Affairs, 2018). In the Yukon Territory, the jurisdiction profile is located in Whitehorse, with an estimated Indigenous identifying population of almost 3,900 (Statistics Canada, 2019). It is the biggest population center in the territory, and all policy barriers and facilitators will be situated as an Indigenous person living in the city (Statistics Canada, 2011). In the NWT, the largest urban center is Yellowknife, with an estimated Indigenous identifying population of 4,300 (Statistics Canada, 2017). Due to this city being biggest population center in the territory, the jurisdiction profile will be located here. With the establishment of jurisdiction profiles, the contexts can be assumed during the reading of the policy texts, and a comparison between the jurisdictions can be made.

Assessment of Policies

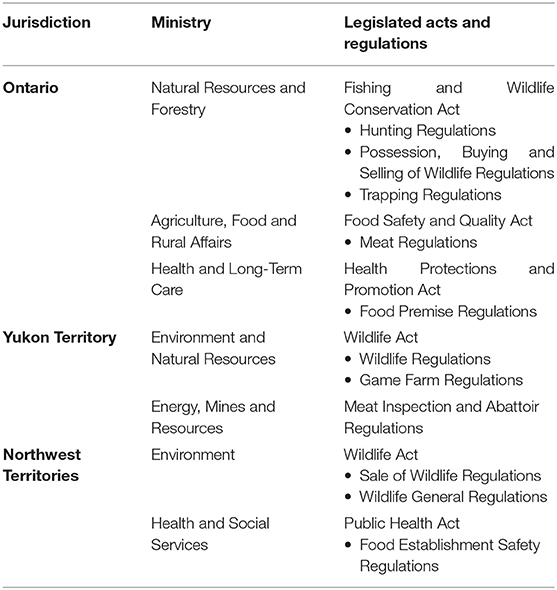

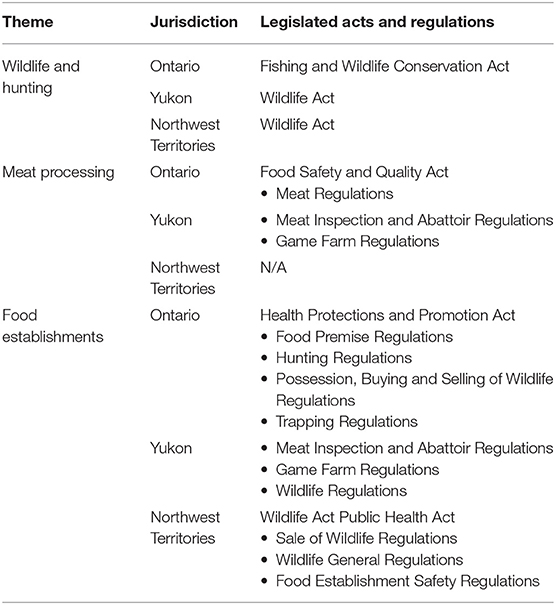

Through the title screening process, six legislated acts and 11 legislated regulations across three provincial and territorial jurisdictions were identified. These policies have been organized by Ministry (see Table 1) and by theme (see Table 2).

When the identified policies are organized by ministry, there is no apparent pattern or significance in its organization. However, when the policies are organized by theme, some interesting nuances appear. The first pertains to the relationship between legislated acts and the regulations that are under them. In some jurisdictions, the regulations under an act are not categorized under the same theme as the act itself. This can be seen with Both Wildlife acts (Yukon and NWT) and the Fish and Wildlife Conservation Act. Despite these acts falling under the Wildlife and Hunting theme, almost all the regulations fall under the Food Establishments theme. The second nuance is that some acts and regulations overlap between two different themes. This can be seen with Wildlife Act in the NWT being categorized under the Wildlife and Hunting and the Food Establishment themes.

Wildlife and Hunting

Policies pertaining to wildlife or hunting have a direct influence on access to traditional/country food since the only way for an Indigenous person to access traditional/country food is to go out on the land and harvest themselves. Despite the entrenchment of harvesting rights, territorial and provincial governments may impose restrictions through policy to achieve government mandates. The following section includes the findings from the analysis which highlights the barriers which Indigenous Peoples in urban centers encounter.

Lands

The prima facie similarity among these policies is that what can be done by an individual looking to harvest depends on what lands they are on. In Ontario, there are over 40 different treaties that exist in the province and Indigenous hunters are entitled to only hunt on the lands which their band is a benefactor under their unique treaty right (Ministry of Indigenous Affairs, 2018). Under the Indian Act, a band is defined as “a body of Indians, for whose use and benefit in common, lands, the legal title to which is vested in Her Majesty” (Indian Act, 2017). There are only certain circumstances where an Indigenous hunter can harvest on treaty lands that are not their own in Ontario. For example, possessing a Shipman letter, which is written permission from another band's leadership to hunt on their treaty lands within the province (Shipman, 2007). In the territories, the introduction of Comprehensive Land Claim Agreements and Self Government Agreements adds another layer of complexity to understanding what policies apply to harvesters on different lands. For an Indigenous person living in Whitehorse YT, they would be entitled to hunt on the traditional lands their band manages or the settlement lands that their land-claim or self-government-agreement encompasses (Yukon First Nations Self Government, 2019). In Yukon, there are 13 unique Land Claim and Self Government Agreements. These lands are the property of the Indigenous communities and the beneficiaries within, which gives exclusive rights to hunt on these lands, with some restrictions being imposed by the federal or provincial governments (Yukon First Nations Self Government, 2019). Similar to Ontario, to hunt on the traditional territory that is not of the hunter's band within Yukon, they must receive written consent from the Indigenous government group managing the land (Yukon Department of Environment, 2018). In the NWT, harvesters are only entitled to harvest within their respective band's lands (Government of Northwest Territories, 2013, 2020). There are four different settlement agreements and two reserves under the Indian Act, all of which have unique rules and restrictions for harvesting on their respective lands (Government of Northwest Territories, 2013, 2020). The identified policies involving land use for harvesting present challenges for Indigenous Peoples living in urban centers. These individuals have essentially only three options, enter the provincial or territorial lottery, to travel back to the lands where their band has treaty rights, or request for a Shipman's letter or similar permission to hunt on other treaty right lands.

Licensing

An Indigenous harvester in Ontario must have the necessary licensing and tags to hunt moose that is not on the lands which their band is benefactor (Fish Wildlife Conservation Act, 1997). For Indigenous individuals looking to harvest on lands other than their treaty lands, they must have an Outdoors Card, a federal firearms license, a H2 hunting license, an animal tag from the lottery system and, a Shipman's Letter (Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry, 2021). Tags are distributed by the Ministry through an online lottery system to hunters that pay a tag fee and apply to enter a draw within a specific wildlife management unit (Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry, 2021). In Ontario, Indigenous Peoples hunting on their band's treaty lands do not need any form of hunting license if they stay within the treaty's geographic boundaries (Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry, 2021). For Indigenous hunters in Yukon, a license is required under the Wildlife Act to hunt any animal, however there are certain circumstances where an individual may hunt game without a license (Wildlife Act, 2014). For example, if a wild animal is killed out of an absolute necessity for survival under Section 85, or under Section 200 which covers the general rights that an Inuvialuk possesses to harvest wildlife in the Yukon North Slope (Wildlife Act, 2014).

When comparing Ontario to the territories, treaty lands and lands under a Comprehensive Land Claim Agreement are very similar. Comprehensive Land Claims are treaties that have been institutionalized into contemporary governance structures. For example, hunting rights can be limited by the Inuvialuit Regional Corporation imposing harvesting restrictions for a specific species for conservation purposes (Wildlife Act, 2014). In the NWT, the roles for both territorial and Indigenous wildlife governing actors are included within the Wildlife Act. When comparing to Ontario and Yukon, the NWT also has licensing requirements for certain tags depending on what lands a harvester is planning to hunt on. An Indigenous hunter does not need to hold a license to exercise their hunting rights on their band's treaty or land claim agreements lands. However, if an Indigenous hunter would like to hunt on lands which they are not a benefactor, they can apply for a general hunting license (Wildlife Act, 2017). This type of license is subject to restrictions within the respective Comprehensive Land Claim Agreement. Within the NWT, the majority of wildlife management is managed by Renewable Resource Boards (RRB) and Local Harvesting Committees (LHC), which are both management branches under Land Claim agreements (Wildlife Act, 2017). This is an oversimplification of the relation between management boards and the territorial government in the NWT. However, since this study has an urban focus, the nuances of the relationship outside the scope of this paper.

Harvest Quota

Harvest quotas are a conservation tool used to ensure that certain species are not over harvested. These quotas are established in the context of each individual Comprehensive Land Claim Agreement in the territories and by the provincial government in Ontario. Within the Sahtú Dene and Métis Comprehensive Land Claim Agreement, the needs of the people on the land for sustenance, the previous year's harvest of the species, and the requirements for conservation are all taken into calculation (Dene and Métis Comprehensive Land Claim Agreement, 1993). This harvest quota “shall be equal to one half of the sum of the average annual harvest by participants over the first 5 years of the study and the greatest amount taken in any one of those 5 years (Dene and Métis Comprehensive Land Claim Agreement, 1993).

In the NWT, The Wildlife Act is the over-seeing policy which details the process of allocation of harvests in the territory. First is the allocation of Indigenous subsistence usages for those with land claim or treaty rights to harvest (Wildlife Act, 2017). Second, the allocation for holders of general licenses who do not have Indigenous treaty rights and those with special harvester licenses and resident hunting licenses (Wildlife Act, 2017). Third, the remaining allocation goes to non-resident license holders and for territorial commercial purposes (Wildlife Act, 2017). In the Yukon, subsistence quotas exist with very similar guidelines as a harvest quota. An example of this can be found within the Wildlife Act, where the subsistence quotas apply only to the beneficiaries of the Inuvialuit Final Agreement (Wildlife Act, 2017). In Ontario, quotas are calculated through a comprehensive reporting system, wildlife population monitoring, and actively managing the 95 different wildlife management units in the province (Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry, 2020a,b).

Meat Inspection and Processing

On the scale of the individual, no regulations dictate how the processing of wild game can be performed. This would be in direct violation of Section 35 of the Constitution, as traditional processing has cultural relevance to Indigenous Peoples (Constitution Acts, 1867–1892). Beyond the individual, there are two general routes that can be taken to get meat processed, a provincial/territorial abattoir or a custom-cut and wrap shop. The notable difference between these two routes can be found within the definition section of each respective territory or province. In the NWT, there is no difference between the two, as a food establishment includes a premise where food is manufactured, stored, offered for sale, and served (Public Health Act, 2007). This is a stark difference from Ontario and Yukon, which have semantically differentiated the two in legislation. In Ontario and Yukon, the provincial/territorial meat processing facilities are referred to as abattoirs, while custom-cut and wrap shops are classified either as a food premise or food serving premise if they serve meals for immediate consumption (Meat Inspection and Abattoir Regulations, 1998; Food Premises Regulations, 2017; Health Protection and Promotion Act, 2019). There is not a need to distinguish the two in the NWT, as there are no territorial licensed meat processing facilities or meat processing regulations in the territory (Judge, 2021).

In Ontario, there are two main consolidated policies that oversee meat inspection or processing. The Food Safety and Quality Act covers licensing, quality assurance, safety, and the powers of inspectors (Food Safety and Quality Act, 2001). The specific protocols and rules for meat processing can be found in the Meat Regulations. All food animals must receive an ante-mortem inspection and post-mortem inspection before being further processed into food (Meat Regulations, 2018). In the Yukon, polices around meat processing and inspection stem from one regulation: Meat Inspection and Abattoir Regulations. Section 6 states that no person shall bring a dead animal into an abattoir unless it has been inspected by a veterinarian (Meat Inspection and Abattoir Regulations, 1998). This essentially prevents any hunted game carcasses from entering a meat processing facility, as it is impossible to conduct an ante-mortem inspection on wildlife. In addition to this, the definition of meat under the regulation explicitly states that meat is only from farm slaughtered carcasses (Meat Regulations, 2018). This renders every part of the act that refers to meat to be from food animals that are raised on a farm. However, in Yukon there are game animals that can enter these facilities. Under Section 26 subsection (2) of the Game Farm Regulations are the restrictions and guidelines for how game farm animals can legally enter a territorial abattoir (Game Farm Regulations, 1995). Game farm animals may only be slaughtered at a game farm, a territorial licensed abattoir, or a federally licensed abattoir (Game Farm Regulations, 1995). However, the process of accessing game farm animals like elk or bison raised do not have the same cultural significance as going onto the land to hunt for wild animals, as being on the land is an opportunity to facilitate their well-being (Halseth, 2015).

In Ontario, the only exception that allows hunted game animals into a provincial facility is if the operator has an established hunted game carcass protocol (Meat Regulations, 2018). An operator must apply for approval under Section 48.48 of the regulation to have a hunting game carcass protocol (Meat Regulations, 2018). The restrictions for this protocol are stringent, as a facility must ensure that the utensils, equipment, and premises are not contaminated by any processed hunted game carcasses (Meat Regulations, 2018). This ultimately results in two possible approaches for meat processing facilities. The first is that the facility processes hunted game carcasses after all the scheduled farmed meat carcass have been processed. The facility would have to be sanitized twice, once to ensure that the farm carcasses do not contaminate the hunted game carcass, then once again to prepare for the next day of farm animal carcasses (Meat Regulations, 2018). The second option is having a separate section of the facility with separate utensils, equipment, and frozen storage areas. Both options are costly, as the first option entails deviation from the main revenue-generating-animals and the second involves building an entirely different facility. Due to the reality that finding a game animal while hunting is not guaranteed, hunting is seasonal, and the quantity of hunted carcass is often in single digits, establishing a hunted game protocol is not worth the investment for these provincial or territorial facilities.

At this current point in time in the NWT, there are no territorial meat processing facilities nor is there any meat processing legislation. The Meat Inspection and Processing Act was repealed in 2009, as it was deemed to be obsolete as no territorial meat processing facilities exist in the territory. In an interview with a GNWT employee, we learned that the territory was planning on building the new meat regulations from the food class licensing system in British Columbia (Judge, 2021). Specifically, the NWT is interested in the Class D licensing system, where small facilities can receive uninspected meat to be sold at local farm gate and food establishments (Judge, 2021; Ministry of Agriculture Food and Fisheries). At this point in time, there was no plan for the NWT to allow the sale of wild game meat within this system.

Food Establishments

For food establishments, jurisdiction over selling or serving traditional/country food is similar to hunting on lands in the sense it depends what type of establishment you are purchasing from. In Ontario's Food Premises Regulations, there is a difference between an establishment that sells food and an establishment that prepares food for immediate consumption (Food Premises Regulations, 2017). The former is in reference to a butcher shop that would custom cut, wrap and freeze wild game meat for an individual, while the latter is a restaurant or similar style business (Food Premises Regulations, 2017). The regulations in Ontario explicitly state that wild game meat cannot be for sale, as all wrapped cuts must have a label with “Consumer Owned, Not for Sale” clearly visible. (Food Premises Regulations, 2017). The specific guidelines to process wild game at a butcher shop are included within the Food Premise Regulations, while the Yukon has its guidelines are within a one-page document that can be found on the Ministry of Health and Social Services website (Yukon Department of Health and Social Services, 2014). For a butcher shop in Yukon to process wild game meat, it must follow these guidelines: have an established sanitation procedure, only allow wholesome meat to be processed, keep uninspected meat clearly identified and kept separate from inspected meat, and have dedicated work hours to process uninspected meat (Yukon Department of Health and Social Services, 2014).

This is very similar to Ontario, as under the Food Premises Regulations, the following is required to admit wild game, or uninspected meat into an establishment: if the owner has received approval from the ministry, has a protocol to ensure the uninspected meat will not come into contact with inspected product, that each quarter or large section of meat has its own tag, the tag reads “Consumer Owned, Not for Sale,” that the meat is not kept in areas were product is sold, and the meat is not offered for sale (Food Premises Regulations, 2017). An interesting discrepancy is that this one-page document does not have any reference to any of the licensing required to process wild game in Yukon. This is interesting, as Section 76 of the Wildlife Regulations states that no individual or business shall engage in the process of cutting or storing meat unless they are the holder of a wildlife meat processing license, which is issued by the Minister (Wildlife Regulations, 2012). As mentioned previously, there is only one type of food establishment in the NWT, however there are no specific details on guidelines for a custom-cut and wrap establishments to process wild game meat. Jurisdiction on this matter would fall under the repealed meat regulations in the territory.

Commercial Sale of Wild Game Meat

Between the three jurisdictions, there is a shared narrative on the restriction of sale of wildlife or paying an individual to hunt for wild game. In the definition section of the Fish and Wildlife Conservation Act in Ontario, “buy or sell” is defined to include trading, bartering, buying or selling (Fish Wildlife Conservation Act, 1997). This is similar to the CFIA's definition under the SFCA “includes agree to sell, offer for sale, expose for sale or have in possession for sale—or distribute to one or more persons whether or not the distribution is made for consideration” (CFIA, 2019a). In addition, a sale is considered to have taken place whether money (or other compensation) is exchanged (CFIA, 2019a). Under Section 48 (1) of the Fish and Wildlife Conservation Act, an individual is not permitted to buy or sell wildlife, unless the individual themselves, or the person who is selling, has the appropriate license or authority from the Minister (Fish Wildlife Conservation Act, 1997). There are several different types of licenses that allow an individual to commercially sell wild game meat, such as a trapping license, a farming license, or a commercial permit assigned by the Minister (Fish Wildlife Conservation Act, 1997; Trapping Regulations, 1997). The restrictions on selling wild food are covered between two Ontario Regulations: Possession and Buying and Selling of Wildlife and Hunting Regulations, where there are two different scenarios where wild food can be sold. The first is under Section 20 of Possession, Buying and Selling of Wildlife, where an individual who purchases wild game meat from a licensed seller can only offer it for consumption to the buyer themselves and their immediate family (Possession, Buying and Selling of Wildlife, 1997). In addition, the seller must provide written notice that the wild game meat for sale has not been inspected by an inspector under the Food Safety and Quality Act (Possession, Buying and Selling of Wildlife, 1997). The second scenario is covered under Section 135.1 of the Hunting Regulations is covered in more detail in the following section.

In order for a piece of meat to be sold in the Yukon, it must undergo inspection, as outlined in the Meat Inspection and Abattoir Regulations. Specifically, under Section 7, no person shall sell meat to any person unless it was slaughtered in a licensed abattoir, there was a post-mortem inspection, and it received a stamp of approval from an inspector (Meat Inspection and Abattoir Regulations, 1998). There is an exemption to these restrictions with game farm animals, as a game farm owner with a permit from the Minister can sell game meat through a direct sale to the consumer at their farm (Game Farm Regulations, 1995). In the NWT, the consolidated acts and regulations that establish the restrictions on selling or serving food are the Wildlife Act, Sale of Wildlife Regulations and Food Establishment Safety Regulations and Wildlife General Regulations. Under Section 75 of the Wildlife Act, no person shall engage in commercial harvests or sell the meat of wildlife unless they hold a commercial license (Wildlife Act, 2017). The criteria for obtaining a commercial license, or commercial tag, is covered under Section 2 of the Sale of Wildlife Regulations. It states that LHC can authorize the holder of a license to only sell the meat of barren-ground caribou, muskox, and polar bear if the harvest quota for the region has not been met (Sale of Wildlife Regulations, 2019).

Community Events

Despite harvesting being the main activity to access traditional/country food, sharing traditional/country food through kinship relations is a significant source of access for Indigenous Peoples. In Ontario, there are two different policies that permit wildlife to be sold and served on a menu, The Hunting Regulations and the Food Premise Regulations. Under Section 135.1 of the Hunting Regulations a person is exempt from the restrictions on selling wildlife covered in the Fish and Wildlife Conservation Act if all the following conditions are met: the meat is lawfully obtained under the act, the game or fish has been donated to a charitable event where all proceeds are toward the charitable purpose, written notice is given to local health units at least 5 days in advance of the event, that the record of who attended the event, the expenditures and revenue, and how the profits were used for profit are kept for 1 year after the event (Fish Wildlife Conservation Act, 1997; Hunting Regulations, 1997). The two policies are almost identical, but a notable addition within the Food Premise Regulations is the required signage that must be placed in high traffic areas as well as written notice explaining that the meat has not been inspected under the Ontario Meat regulations (Food Premises Regulations, 2017). The guidelines for serving wild game are also further expanded by the wild game serving protocols established by each local public health unit (Government of Ontario, 2019). The Yukon is very similar to Ontario when it comes to strenuous guidelines that must be followed to serve wild game meat at a community event. The Yukon Environmental Health Services offers a form on their website that includes the criteria for an event to be able to sell wild game and the form to apply to do so (Yukon Environmental Health Services, 2014). Within this form, there are two scenarios to which wild game can be served.

The first is an event where wild game meat is being sold for profit. In this scenario, the event planners must obtain a wildlife permit to sell wild game meat and a permit to operate a temporary food premise, must be a registered society or charity, and the wild game meat must be donated to event (Yukon Environmental Health Services, 2014). The details for the wildlife permit to sell game are listed under Section 5 of the Wildlife Regulations (Wildlife Regulations, 2012). The Minister may issue a permit to serve wild food for remuneration if: the permit is given to a non-for profit or charitable organization, the food is served in conjunction with other meals, and the hunted game was harvested legally under the Wildlife Act (Wildlife Regulations, 2012). The second type of event that serves wild game meat sold not for a profit, which the guidelines under this type of event are not as strict as the previous. An event operator must only ensure that written permission is received from conservation officer services, the wild game meat is donated, and that a permit to operate a temporary food premise is obtained (Yukon Environmental Health Services, 2014). In comparison to Ontario and Yukon, the NWT has very little guidance on serving or sharing wild game meat. Under Section 30 of the Food Establishment and Safety Regulations, a food establishment operator is allowed to serve uninspected wild game within their establishment, as long as it is obtained legally through an individual or organization with a commercial tag (Food Establishment Safety Regulations, 2018). However, individuals or organizations do need to apply for a food establishment permit if food will be sold in a setting without an existing permit. There are two types of food establishment permits under the Food Establishment and Safety regulations, for profit permits and non-for-profit permits. For profit food permits have a sliding scale cost depending on the length of permit, while all non-for-profit permits are free (Food Establishment Safety Regulations, 2018). In addition, no permit is required by the Department of Health and Social Services as if the event is a traditional community feast (Food Establishment Safety Regulations, 2018).

While the sale of wildlife in the NWT is limited to only commercial tags or establishments that buy from hunters with commercial tags, there is nothing that prevents Indigenous Peoples from sharing their traditional/country food (Food Establishment Safety Regulations, 2018). However, here are still policies that apply to the sharing of wild food in an urban center. For example, under Section 13 of the Wildlife General Regulations, if a gift of more than 5 kg of lawfully harvested game meat is to be given, it must have the following information with it: name of harvester, license number or name of Indigenous organization to which the person is donating, the date of the transaction, the species, and the exact weight of meat (Wildlife General Regulations, 2017).

Discussion

In discussing these findings, we look to incorporate case study examples from other countries and populations that have similar colonial histories that have impacted policy for Indigenous populations. However, within Canadian and international literature, there is a knowledge gap on the policy barriers which impact Indigenous Peoples access to traditional/country food in urban centers. The minimal literature available in this area of research pertains to Indigenous Peoples in remote and rural areas across the globe. Nonetheless, this literature was included to situate the results of this paper into the broader international context of Indigenous Peoples and the impacts policy has on accessing traditionally consumed foods. Furthermore, the countries included in this discussion are all supporters of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (United Nations, 2007).

Wildlife and Hunting

Lands

The results of this analysis show the significance that geographical boundaries of land established within policy can have when accessing traditional/country food. Within the literature, there appears to be no studies on the experience of other international Indigenous populations in urban settings. Most of the literature has focused on remote geographies. For example, in Cameroon the state owns the forests and is the institution responsible for enforcing the 1994 Forest Law, the piece of legislation which establishes the rules for hunting (Pemunta, 2019b). Traditional hunting is prohibited in protected areas, national parks, reserves, hunting areas and wildlife sanctuaries. In Mexico, hunting and land use for the Chinantla Peoples of Santiago Tlatepusco is managed by the National Forestry Commission of Mexico. The Chinantla Peoples of Santiago Tlatepusco have submitted two payments for hydrological environmental services areas as 47% of the community resides in the third largest tropical humid forest in the country (Ibarra et al., 2011). This resulted in an agreement with the community which entails restrictions on what activities can be practiced by community members in order to receive their annual payment (Ibarra et al., 2011). For the Sami in Norway, pastoral lands are co-managed by local district boards comprised of elected municipal and Sami representatives (Risvoll et al., 2014). In Norway, access to traditionally consumed food is more a matter of agriculture than wildlife. Reindeer husbandry is a significant economic and subsistence activity for Sami pastoralists. Within the Reindeer Husbandry Act, local district boards are responsible for establishing work plans to manage the reindeer populations of pastoralists within each board (Melkevik, 2002; Ulvevadet and Hausner, 2011). What is significant between the international cases and the result of this study is where an individual resides geographically has policy implications. However, the degree to which these place-based implications effect traditional/country food access for Indigenous Peoples in urban geographies was only apparent in the results of this analysis.

Animal Protection and Conservation

We can learn from international examples of how wildlife as food is governed. In Cameroon, the law has divided animals into three different categories, which allows the Indigenous Pygmy Peoples to only hunt animals under the third class, as the other two classes are protected for conservation (Pemunta, 2019b). This classification scheme has a direct impact on the ritual practices of the Pygmy Peoples. Hunting an elephant is part of a rite of passage ceremony. However, partaking in this ceremony is considered poaching which is illegal and has safety risks due to armed forest protection forces (Pemunta, 2019b). In Mexico, the Chinantla Peoples face a similar reality, where the establishment of PEH-S areas created restricted activities, such as hunting or agriculture. In Norway, the resurgence of predators has resulted in contemporary predator conservation measures which is negatively impacting Sami reindeer husbandry practices (Risvoll et al., 2016). The protection of animals from hunting through policy is also seen in Canada, with the establishment of Endangered Species Acts at the national and territorial/provincial level. Furthermore, there are instances of harvesting restriction policies for significant traditional/country foods like caribou being implemented at the community level for some remote communities (Spring, 2018; Judge, 2021).

The harvest quotas identified in results are another policy tool used in Canada to manage wildlife populations. For Norway, harvest quotas are used as a pasture conservation policy tool, where mandatory slaughters regulate reindeer populations to maintain seasonal pastures (Ulvevadet and Hausner, 2011). It is an interesting nuance that harvest quotas exist as a conservation policy tool in both Norway and Canada. However, the former pertains to managing overpopulation while the latter refers to managing over harvesting. These complex calculations that are supposed to ensure a sustainable number of animals can be harvested, while also accounting for the sustenance needs of Indigenous Peoples, do not account for the extrinsic, environmental, and economic factors that arguably have a greater impact on animal population health. For example, Parlee et al. found that subsistence harvesting has a minimal impact on caribou populations relative to the impacts of natural resource exploration (and exploitation) (Parlee et al., 2018). Logging and other resources development projects in Cameroon in tandem with animal conservation polices have left Indigenous Pygmy Peoples with only a small number of animal species to harvest, often not enough to meet their sustenance needs (Pemunta, 2019a). It is apparent that across the world, Indigenous Peoples and their ability to engage with the land and its resources are being controlled and manipulated by conservation policy.

Meat Inspection and Processing

Within the international literature we have brought into this discussion, there was no mention of meat inspection and processing policies. For this reason, this section will situate the results from the three jurisdictions in a broader Canadian context. Prior to the establishment of the Safe Food for Canadians Act and Regulations (SFCR, 2019), federal operators had the flexibility to prepare game meat under the existing meat inspection regulations (CFIA, 2015). The meat processing regulations mainly focused on meat from farms rather than wild game, with all the additional protocols required to process the latter in a government facility (CFIA, 2015). The Canadian Food Inspection Agency on their website cite that the new food safety regulations will encourage the industry to innovate and increase food export capacity (CFIA, 2019b). This intended design for the food system can also be seen in British Columbia, with the introduction of provincial meat inspection regulations greatly impacted small-scale farmers (Miewald et al., 2015). The new meat regulations were designed for more centralized facilities with a more industrialist and export-oriented approach to food processing (Miewald et al., 2015).

This approach to meat processing creates challenges for small scale and local processing initiatives, as these requirements require upfront capital investments which was also identified in the results of this analysis. The impacts of these policies are a loss of coherence between local food producers and the local community, which are expected results of a meat processing system rooted in neo-liberal agricultural values (Desmarais and Wittman, 2014; Miewald et al., 2015). A study within Alaska by Jenkins (2015) regarding traditional fishing economies echoes these sentiments. Neo-liberal policies on wildlife ignore the cultural significance of sharing food and the benefits to kin in their immediate and extended communities (Jenkins, 2015).

For Indigenous Peoples, food sovereignty is rooted in the disengagement from colonial food practices to reintroduce cultural traditions pertaining to food (Grey and Patel, 2015; Martens et al., 2016). Restrictions from meat progressing regulations as well as repealed policies for wild game meat identified in the three jurisdictions of this paper indicate there is still work to be done. The right to engage in cultural practices was established in several of the articles established in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (United Nations, 2007). With the close relation between to food and Indigenous culture and spirituality, the Canadian governments needs to focus on empowering Indigenous communities to work toward establishing and managing their own food systems.

Food Establishments

Reindeer have historically played a similar role to wild game (and moose and caribou in particular) in North America, where it has been used for clothing, food, and tools for Indigenous Peoples. This changed when policies were used to limit the number of reindeer pastoralists to conserve pastures and to increase reindeer meat profits (Bostedt et al., 2003; Ulvevadet and Hausner, 2011). This resulted in a shift that has made reindeers an important economic resource for Sami (Indigenous population in the circumpolar Scandinavian and Russian north) pastoralists and their families. In Cameroon, wild food can be sold if the harvester has obtained permission or a hunting license from the administration and has paid taxes (Pemunta, 2019b).

Country food markets have been a successful initiative to increase traditional/country food access in Greenland (Loukes et al., 2021). In Canada, there are also instances where country food markets have been briefly piloted. The sale of traditional food is not only affected by policy, there are also cultural norms for certain Indigenous groups across Canada that encourage sharing traditional/country food over selling it (McMillan and Parlee, 2013; Loukes et al., 2021). Within Canada, sharing traditional/country food is seen as a mediator for food insecurity (McMillan and Parlee, 2013; Spring, 2018). However, lack of access to the resources required to harvest due to poverty and other socioeconomic causes creates limits to sharing capacity (Ready, 2018). In the literature, the language of “stingy” has been associated with those who sell (or store) traditional food over sharing it (Martens et al., 2016; Searles, 2016; Judge, 2021). Within the policy barriers identified in this analysis, along with the nuances identified within the literature (Loukes et al., 2021), the complexities of selling and sharing traditional foods needs to be investigated further.

Barriers Beyond the Scope of Policy

Indigenous communities, especially those in the remote north often operate within a mixed economy, which is characterized by a blend of traditional activities like hunting and fishing, cash generating activities such as job contracts, and income from social transfers (Abele, 2009). This mixed economy is often complemented by kin networks, where one member will work for a wage, to provide the upfront capital required for other kin members to engage in traditional activities (Abele, 2009). For example, the cost of gasoline, ammunition, snow machine repairs, and guns are all costs have to be taken into consideration before engaging in traditional activities like hunting or fishing (Pal et al., 2013; Leibovitch Randazzo and Robidoux, 2018). This means that an Indigenous harvester needs to have a certain threshold of income in order to engage in traditional activities to access traditional/country foods. Without this upfront capital, harvesters are limited in the amount of traditional food that can be accessed, directing these families to rely on market foods. Furthermore, the pressure to participate in the market economy in order to sustain participation in traditional harvesting activities paradoxically results less time to engage in harvesting activities (Wilson et al., 2020).

The findings of this paper illustrate that there are policies in multiple jurisdictions across Canada that impact Indigenous Peoples access to traditional/country foods in urban centers. Not only do policies exist that have jurisdiction on how wild game can be accessed, but where it can be processed, where it can be sold, and how it can be shared. In addition, the findings from this paper contrasted with the international case studies identified in the discussion highlight that Indigenous Peoples globally, despite their international recognition to self-determine, are still being controlled by governments through policy.

Conclusion

The purpose of this paper was to identify barriers within policy for Indigenous Peoples to access their traditional food within an urban center. Barriers were identified in all three provinces/territories, Ontario, Yukon and the NWT, included in the analysis. In this paper, we began to unravel the complex web of government jurisdictions on traditional/country foods, such as hunting, processing, selling, and serving across Canada. Within our analysis, policies fell under three themes, which closely align with the different mechanisms to acquire traditional/country food: hunting, sharing, or selling. We found sections within policies pertaining to hunting and wildlife, meat processing, and food establishments that would result in barriers for Indigenous harvesters trying to access traditional/country food in each of the jurisdiction profiles within this analysis.

Due to the scope of this paper, we were limited in understanding all of the contextual factors specific to Indigenous communities that impact their food access, such as access in remote settings and access to other traditional/country foods such as fish. The results of this paper highlight the need for a more comprehensive analysis of the policies involved with access, processing, and serving traditional/country foods. It is a reality that Canada has many actions to take as it still moves toward reconciliation. As a nation, we must continue to hold the Canadian government accountable, and for provincial/territorial policy makers, for ensuring that action is taken and that the Truth and Reconciliation Calls to Action are implemented and enacted.

Author Contributions

CJ and KS: conceptualization and writing—original draft preparation. CJ: methodology, formal analysis, and investigation. CJ, KS, and AS: writing—review and editing. KS and AS: supervision. KS: project administration and funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by a Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC) Insight Grant (File Number: 435-2017-0926; PI: KS) and a Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Team Grant (Grant Number 166443; PIs: KS, and AS).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^Traditional food, country food, traditional/country and wild food are all terms utilized within this paper. The Canadian Council of Academies (CCA, 2014) has established that the use of traditional/country food is the most appropriate language to be more inclusive of the cultural-ethnic nuances among the diverse Indigenous groups in Canada. However, within the policy descriptions in this paper, the term wild food or wild game are used instead of traditional/country food as wild food/wild game is the terminology used in acts and regulations. This is due to the fact that within policy, wild game has no cultural significance and wildlife is understood only as a resource. This paper shall use traditional/country food interchangeably when referring to cultural and spiritually significant foods, while the term wild food or wild game will be used while referring to the context of a policy.

2. ^Canadian Legal Information Institute (CanLII). Montreal Declaration on Free Access to Law. CanLII. Available online at: https://www.canlii.org/en/info/mtldeclaration.html.

3. ^City of Toronto. Indigenous people of Toronto. https://www.toronto.ca/city-government/accessibility-human-rights/indigenous-affairs-office/torontos-indigenous-peoples/.

References

Abele, F. (2009). The state and the northern social economy: research prospects. North. Rev. 30, 37–56.

Baskin, C. A., Guarisco, B., Koleszar-Green, R., Melanson, N., and Osawamick, C. (2008). Struggles, strengths and solutions: exploring food security with young Aboriginal moms. Esurio: J. Hung. Pov. 1, 3–16.

Beaudoin, G. A. (2019). Distribution of Powers. The Canadian Encyclopedia. Available online at: https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/distribution-of-powers (accessed March 18, 2019).

Bostedt, G., Parks, P. J., and Boman, M. (2003). Integrated natural resource management in northern Sweden: an application to forestry and reindeer husbandry. Land Econ. 79, 149–159. doi: 10.2307/3146864

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Brown, J., Isaak, C., Lengyel, C., Hanning, R., and Friel, J. (2008). Moving to the city from the reserve: perceived changes in food choices. Pimatisiwin 6, 1–16.

CCA. (2014). Aboriginal Food Security in Northern Canada: An Assessment of the State of Knowledge: Expert Panel on the State of Knowledge of Food Security in Northern Canada. Canadian Council of Academies (CCA). Available online at: https://foodsecurecanada.org/sites/foodsecurecanada.org/files/foodsecurity_fullreporten.pdf (accessed April 7, 2019).

CFIA. (2015). Archived - Annex G - Game Meat Preparation. Government of Canada Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA). Available online at: https://www.inspection.gc.ca/food-safety-for-industry/archived-food-guidance/meat-and-poultry-products/manual-of-procedures/chapter-17/annex-g/eng/1433169076630/1433170816393 (accessed August 4, 2020).

CFIA. (2019a). Food Products that Require a Label, Definitions. Government of Canada. Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA). Available online at: https://www.inspection.gc.ca/food-label-requirements/labelling/industry/label/eng/1388160267737/1388160350769?chap=6#s12c6 (accessed August 4, 2020).

CFIA. (2019b). What the Safe Food for Canadians Regulations Mean for Consumers. Government of Canada. Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA). Available online at: https://www.inspection.gc.ca/food-safety-for-industry/information-for-media/consumers/eng/1528485005815/1528824875029 (accessed August 4, 2020).

Cidro, J., Adekunle, B., Peters, E., and Martens, T. (2015). Beyond food security: understanding access to cultural food for urban Indigenous people in Winnipeg as Indigenous food sovereignty. Canad. J. Urb. Res. 24, 24–43.

CIRNAC. (2020a). Self-Government. Government of Canada. Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada (CIRNAC). Available online at: https://www.rcaanc-cirnac.gc.ca/eng/1100100032275/1529354547314 (accessed August 5, 2020).

CIRNAC. (2020b). Treaties and Agreements. Government of Canada. Department of Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada (CIRNAC). Available online at: https://www.rcaanc-cirnac.gc.ca/eng/1100100028574/1529354437231#wb-cont (accessed August 5, 2020).

Constitution Acts (1867–1892). Available online at: https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/PDF/CONST_TRD.pdf (accessed April 7, 2019).

De Schutter, O. (2012). Report of the Special Rapporteur on the right to food, Olivier De Schutter, Addendum. Mission to Canada. Available online at: http://www.srfood.org/images/stories/pdf/officialreports/20121224_canadafinal_en.pdf (accessed August 11, 2020).

Desmarais, A. A., and Wittman, H. (2014). Farmers, foodies and First Nations: getting to food sovereignty in Canada. J. Peas. Stud. 41, 1153–1173. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2013.876623

Elliott, B., Jayatilaka, D., Brown, C., Varley, L., and Corbett, K. K. (2012). We are not being heard: aboriginal perspectives on traditional foods access and food security. J. Environ. Publ. Health. 2, 1–9. doi: 10.1155/2012/130945

FAO IFAD, UNICEF, WFP, and WHO. (2021). The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2021. Transforming Food Systems for Food Security, Improved Nutrition and Affordable Healthy Diets for All. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). (accessed May 5, 2019).

Fish Wildlife Conservation Act. (1997). S.O. c. 41. Available online at: https://www.ontario.ca/laws/statute/97f41 (accessed May 5, 2019).

FNIGC. (2018). Nutrition and Food Security, Chapter 3.. National Report of the First Nations Regional Health Survey Phase 3: Volume Two. Ottawa: First Nations Information Governance Centre (FNIGC). (accessed May 7, 2019).

Food Establishment Safety Regulations. (2018). R-082-2018. Available online at: https://www.justice.gov.nt.ca/en/files/legislation/public-health/public-health.r8.pdf

Food Premise Regulations. (2017). O.Reg. 493/17. Available online at: https://www.ontario.ca/laws/regulation/170493 (accessed May 5, 2019).

Food Safety Quality Act. (2001). S.O. c.20. Available online at: https://www.ontario.ca/laws/statute/01f20 (accessed May 5, 2019).

Ford, J. D., Smit, B., and Wandel, J. (2006). Vulnerability to climate change in the Arctic: a case study from Arctic Bay, Canada. Glob. Environ. Change 16, 145–160. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2005.11.007 (accessed May 6, 2019).

Game Farm Regulations (1995). OIC, 1995/015. Available online at: http://www.gov.yk.ca/legislation/regs/oic1995_015.pdf

Gardner, H., and Tsuji, L. J. S. (2014). Exploring the impact of Canadian regulatory requirements on the persistence of the subsistence lifestyle: a food security intervention in remote Aboriginal communities. Int. J. Soc. Sustain. 11, 1–10. doi: 10.18848/2325-1115/CGP/v11i01/55249

Government of Northwest Territories (2013). Understanding Aboriginal and Treaty Rights in Northwest Territories. Available online at: https://www.eia.gov.nt.ca/sites/eia/files/gnwt_understanding_aboriginal_and_treaty_rights_in_the_nwt.pdf (accessed February 02, 2022).

Government of Northwest Territories (2020). North West Terriorties Summary of Hunting and Trapping Regulations July 1, 2021 to June 30, 2022. Available online at: https://www.enr.gov.nt.ca/sites/enr/files/resources/enr_hunting_and_trapping_summary-en-web.pdf (accessed February 02, 2022).

Government of Ontario. (2019). Serve Fish or Wild Game at Charitable Events. Government of Ontario. Available online at: https://www.ontario.ca/page/serve-fish-or-wild-game-charitable-events (accessed May 19, 2019).

Grey, S., and Patel, R. (2015). Food sovereignty as decolonization: some contributions from Indigenous movements to food system and development politics. Agric. Hum. Values 32, 431–444. doi: 10.1007/s10460-014-9548-9

Halseth, R. (2015). The Nutritional Health of the First Nations and Métis of the Northwest Territories: A Review of Current Knowledge and Gaps. Available online at: https://www.ccnsa-nccah.ca/docs/emerging/RPT-NutritionalHealthFNsMetis-Halseth-EN.pdf (accessed April 7, 2019).

Health Canada. (2006). Legislation and Guidelines. Government of Canada. Available online at: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/corporate/about-health-canada/legislation-guidelines.html (Accessed April 8, 2019).

Health Protection Promotion Act. (2019). R.S.O. 1990, c. H.7. Available online at: https://www.ontario.ca/laws/statute/90h07 (accessed May 5, 2019).

Hunting Regulations (1997). O.Reg. 665/98. Available online at: https://www.ontario.ca/laws/regulation/980665 (accessed May 5, 2019).

Ibarra, J. T., Barreau, A., Campo, C. D., Camacho, C. I., Martin, G. J., and McCandless, S. R. (2011). When formal and market-based conservation mechanisms disrupt food sovereignty: impacts of community conservation and payments for environmental services on an indigenous community of Oaxaca, Mexico. Int. Forest. Rev. 13, 318–337. doi: 10.1505/146554811798293935

Indian Act. (2017). R.S.C, 1985, c. I-5. Available online at: https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/i-5/ (accessed April 7, 2019).

Jenkins, D. (2015). Impacts of neoliberal policies on non-market fishing economies on the Yukon River, Alaska. Mar. Policy 61, 356–365. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2014.12.004

Johnston, C., and Spring, A. (2021). Grassroots and global governance: can global–local linkages foster food system resilience for small Northern Canadian communities? Sustainability 13, 2415. doi: 10.3390/su13042415

Judge, C. (2021). Local Traditional/Country Food Processing and Food Sovereignty: Investigating the Political Challenges for an Indigenous Self-government to Self-Determine and Develop its Local Food System. Unpublished Masters Thesis. University of Waterloo, Waterloo.

Kerr, G. R., and Kwasniak, A. J. (2014). Wildlife Conservation and Management. The Canadian Encyclopedia. Available online at: https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/wildlife-conservation-and-management (accessed April 8, 2020).

Lardeau, M., Healey, G., and Ford, J. (2011). The use of Photovoice to document and characterize the food security of users of community food programs in Iqaluit, Nunavut. Rur. Remote Health 11, 1680. doi: 10.22605/RRH1680

Lavoie, L. G., Toner, J., Bergeron, O., and Thomas, G. (2011). The Aboriginal Health Legislation and Policy Framework in Canada. Prince George, Canada: National Collaborating Centre for Aboriginal Health.

Leibovitch Randazzo, M., and Robidoux, M. A. (2018). The costs of local food procurement in a Northern Canadian First Nation community: an affordable strategy to food security? J. Hung. Environ. Nutr. 14, 1–21. doi: 10.1080/19320248.2018.1464998

Loukes, K. A., Ferreira, C., Gaudet, J. C., and Robidoux, M. A. (2021). Can selling traditional food increase food sovereignty for First Nations in northwestern Ontario (Canada)? Food Foodways 29, 157–183. doi: 10.1080/07409710.2021.1901385

Martens, T., Cidro, J., Hart, M. A., and McLachlan, S. (2016). Understanding indigenous food sovereignty through an Indigenous research paradigm. J. Indigen. Soc. Dev. 5, 18–37.

McMillan, R., and Parlee, B. (2013). Dene Hunting Organization in Fort Good Hope, Northwest Territories: “ways we help each other and share what we can”. Arctic 66, 435–447. doi: 10.14430/arctic4330

Meat Inspection Abattoir Regulations. (1998). OIC, 1998/104. Available online at: http://www.gov.yk.ca/legislation/regs/oic1988_104.pdf (accessed May 6, 2019).

Meat Regulations (2018). O.Reg. 31/05. Available online at: https://www.ontario.ca/laws/regulation/050031 (accessed May 6, 2020).

Melkevik, B. (2002). The Law and Aboriginal Reindeer Herding in Norway, Sustainable Food Security in the Arctic: State of Knowledge, ed Duhaime, G., (Edmonton, AB: University of Alberta Press), 197–203.

Miewald, C., Hodgson, S., and Ostry, A. (2015). Tracing the unintended consequences of food safety regulations for community food security and sustainability: small-scale meat processing in British Columbia. Local Environ. 20, 237–255. doi: 10.1080/13549839.2013.840567

Ministry of Indigenous Affairs. (2018). Treaties in Ontario Infographic. Government of Ontario. Available online at: https://files.ontario.ca/treaties_in_ontario_infographic_2018.pdf (accessed May 19, 2020).

Ministry of Natural Resources Forestry. (2020a). Hunter Reporting. Government of Ontario. Available online at: https://www.ontario.ca/page/hunter-reporting (accessed April 8, 2020).

Ministry of Natural Resources Forestry. (2020b). Find Wildlife Management Unit Map. Government of Ontario. Available online at: https://www.ontario.ca/page/find-wildlife-management-unit-wmu-map (accessed April 8, 2020).

Ministry of Natural Resources Forestry. (2021). Hunting Regulations Summary Fall 2021 – Spring 2022. Available online at: https://files.ontario.ca/books/mnrf-2021-hunting-regulations-summary-en-2021-04-01-v2.pdf (accessed 08 Feb 2022).

Moss, W., and Gardner-O'Toole, E. (1991). Aboriginal People: History of Discriminatory Laws. Law and Government Division. Available online at: http://publications.gc.ca/Collection-~R/LoPBdP/BP/bp175-e.htm (accessed March 18, 2019).

NIECB. (2019). Recommendations on Northern Sustainable Food Systems. National Indigenous Economic Development Board (NIECB). Available online at: http://www.naedb-cndea.com/reports/What%20We%20Heard%20-%20Roundtable%20on%20Northern%20Sustainable%20Food%20Systems.pdf (accessed March 19, 2019).

Pal, S., Haman, F., and Robidoux, M. (2013). The costs of local food procurement in two Northern Indigenous Communities in Canada. Food Foodways 21, 132–152. doi: 10.1080/07409710.2013.792193

Parlee, B., and Wray, K. (2016). Gender and the Social Dimensions of Changing Caribou Populations in the Western Arctic. Edmonton, AB: Athabasca University Press. 169–190.

Parlee, B. L., Sandlos, J., and Natcher, D. C. (2018). Undermining subsistence: Barren-ground caribou in a “tragedy of open access”. Sci. Adv. 4, e1701611. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1701611

Passelac-Ross, M. (2006). Overview of Provincial Laws. Calgary, AB: Canadian Institution of Resources Law.

Pemunta, N. V. (2019a). Factors impeding social service delivery among the Baka Pygmies of Cameroon. J. Prog. Hum. Serv. 30, 211–238. doi: 10.1080/10428232.2019.1581041

Pemunta, N. V. (2019b). Fortress conservation, wildlife legislation and the Baka Pygmies of southeast Cameroon. GeoJ. 84, 1035–1055. doi: 10.1007/s10708-018-9906-z

Phillipps, B., Skinner, K., Parker, B., and Neufeld, H. T. (2022). An intersectionality-based policy analysis examining the complexities of access to wild game and fish for urban indigenous women in Northwestern Ontario. Fron. Commun. 6, 749944. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2021.762083

Possession Buying Selling of Wildlife. (1997). O.Reg. 666/98. Available online at: https://www.ontario.ca/laws/regulation/980666 (accessed May 5, 2019).

Public Health Act. (2007). S.N.W.T. 2007, c.17. Available online at: https://www.justice.gov.nt.ca/en/files/legislation/public-health/public-health.a.pdf (accessed May 7, 2019).

Ready, E. (2018). Sharing-based social capital associated with harvest production and wealth in the Canadian Arctic. PLoS ONE. 13, e0193759. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0193759

Risvoll, C., Fedreheim, G. E., and Galafassi, D. (2016). Trade-offs in pastoral governance in Norway: challenges for biodiversity and adaptation. Pastoralism 6, 4. doi: 10.1186/s13570-016-0051-3

Risvoll, C., Fedreheim, G. E., Sandberg, A., and Burn Silver, S. (2014). Does pastoralists' participation in the management of national parks in northern Norway contribute to adaptive governance? Ecol. Soc. 19(2). doi: 10.5751/ES-06658-190271

Robin, T., Burnett, K., Parker, B., and Skinner, K. (2021). Safe food, dangerous lands? Traditional foods and indigenous peoples in Canada. Front. Commun. 6, 762083. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2021.749944

Sahtú Dene Métis Comprehensive Land Claim Agreement. (1993). Crown-Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada. Available online at: https://www.eia.gov.nt.ca/sites/eia/files/sahmet_1100100031148_eng.pdf

Sale of Wildlife Regulations. (2019). R-034-2019. Available online at: https://www.justice.gov.nt.ca/en/files/legislation/wildlife/wildlife.r10.pdf (accessed May 8, 2019).

Sandlos, J. (2011). Hunters at the Margin: Native People and Wildlife Conservation in the Northwest Territories. UBC Press.

Schuster, R. C., Wein, E. E., Dickson, C., and Chan, H. M. (2011). Importance of traditional foods for the food security of two First Nations communities in the Yukon, Canada. Int. J. Circum. Health 70, 286–300. doi: 10.3402/ijch.v70i3.17833

Searles, E. (2016). To sell or not to sell: country food markets and Inuit identity in Nunavut. Food Foodways 24, 194–212. doi: 10.1080/07409710.2016.1210899

SFCR. (2019). SOR/2018-108. Safe Food for Canadians Regulations (SFCR). Available online at: https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/PDF/SOR-2018-108.pdf (accessed August 5, 2020).

Shipman, R. v. (2007). ONCA 338. Supreme Court of Ontario. Available online at: http://caid.ca/ShiDec2007.pdf (accessed March 19, 2019).

Skinner, K., Hanning, R. M., Desjardins, E., and Tsuji, L. J. (2013). Giving voice to food insecurity in a remote indigenous community in subarctic Ontario, Canada: traditional ways, ways to cope, ways forward. BMC Public Health 13, 427. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-427

Skinner, K., Pratley, E., and Burnett, K. (2016). Eating in the city: a review of the literature on food insecurity and indigenous people living in urban spaces. Societies 6, 7. doi: 10.3390/soc6020007

Spring, A. (2018). Capitals, Climate Change and Food Security: Building Sustainable Food Systems in Northern Canadian Indigenous Communities (Ph.D. dissertation). Wilfrid Laurier University, Waterloo, Canada. Available online at: https://scholars.wlu.ca/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3149&context=etd

Spring, A., Carter, B., and Blay-Palmer, A. (2018). Climate change, community capitals, and food security: building a more sustainable food system in a Northern Canadian Boreal Community. Canad. Food Stud. 5, 111–141. doi: 10.15353/cfs-rcea.v5i2.199

Statistics Canada. (2011). Aboriginal Peoples in Canada: First Nations, Métis, and Inuit: National Household Survey, 2011. Available online at: http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/nhs-enm/2011/as-sa/99-011-x/99-011-x2011001-eng.pdf (accessed May 19, 2020).

Statistics Canada. (2017). Yellowknife Population Centres, North West Territories – Census Profile 2016 Census. Available online at: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/dp-pd/prof/details/page.cfm?Lang=EandGeo1=POPCandCode1=1044andGeo2=PRandCode2=61andData=CountandSearchText=YellowknifeandSearchType=BeginsandSearchPR=01andB1=AllandGeoLevel=PRandGeoCode=1044andTABID=1 (accessed May 19, 2020).

Statistics Canada. (2019). Whitehorse Population Centre, Yukon and Yukon Territories – Census Profile. Available online at: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/dp-pd/prof/details/page.cfm?Lang=EandGeo1=POPCandCode1=1023andGeo2=PRandCode2=60andData=CountandSearchText=WhitehorseandSearchType=BeginsandSearchPR=01andB1=AllandGeoLevel=PRandGeoCode=1023andTABID=1 (accessed May 19, 2020).