- 1Department of European Languages and Literature, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia

- 2English Language Department, Taif University, Taif, Saudi Arabia

Saudi English has recently emerged as a new variety within the World Englishes framework. Many scholars have argued that there is still a gap in the literature and more studies on Saudi English are needed. This study hopes to contribute to the growing research interest in Saudi English studies. The current study aims to identify Saudi English syntactic characteristics classified in relation to noun phrase, verb phrase, prepositional phrase, and clausal structure. Data were collected using three methods: conversation in natural settings, open-ended questions, and students' writings. The findings confirm that substrate-superstrate interaction affects many syntactic characteristics of Saudi English.

Introduction

Saudi English (SE) is an emerging variety of English (Al-Rawi, 2012; Mahboob and Elyas, 2014; Fallatah, 2017; Elyas et al., 2021) that has not been well-researched and mostly investigated from a pedagogical perspective, where grammatical errors in English have been the focus rather than investigating them as features. However, few recent studies on SE were published within the World Englishes framework (Al-Rawi, 2012; Mahboob, 2013; Mahboob and Elyas, 2014; Fallatah, 2017; Bukhari, 2019; Elyas and Mahboob, 2021a; Elyas et al., 2021), but there is still a gap in the literature and more studies on SE are needed. This study hopes to contribute to SE literature by identifying its syntactic characteristics. To achieve this, several examples have been extracted from SE data collected in different contexts. Grammatical characteristics are analyzed based on Mesthrie and Bhatt (2008) and Kortmann and Szmrecsanyi (2009) classifications of New Englishes features.

Al-Shabbi (1989) stated that English in Saudi Arabia was first introduced in schools in 1924. In the beginning, English was taught for pupils in elementary school, but then it was restricted to intermediate and secondary stages in 1943. After that, English was taught as a subject in Islamic Law in the city of Makkah in 1949. The first English department in Saudi Arabia was established at King Saud University in 1957 [refer to Al-Haq and Smadi (1996) and Elyas (2011)]. The importance of English in Saudi Arabia increased in the 1970s in different domains, such as business, education, and government sectors. Saudi companies, such as Aramco, require their employees to be proficient in English, and different governmental institutions offer English training courses to their employees (Elyas and Picard, 2010, 2013; Elyas, 2011; Mahboob, 2013).

According to a study by Fallatah (2017), the status of English has changed since the King Abdullah scholarship program started in 2005. Many Saudi students traveled to English-speaking countries to earn higher academic degrees in many fields. The importance of English is also evident in its use as a lingua franca between Saudis and foreigners, such as pilgrims, tourists, and workers in international companies (Elyas, 2011). Al-Rawi (2012) stated that learning English helps university graduates to increase their chances of employment in many Saudi and international companies. This, in turn, has motivated well-off families with strong socio-economic backgrounds to send their children to schools where English is taught as a second language. As such, education and proficiency in English have become part of their social prestige (Al-Rawi, 2012). As a result, the Saudi government has made a step forward to increase the number of English institutions, and English-online courses have become a trend by many Saudis who pursue better employment (Elyas and Picard, 2010, 2012, 2018; Elyas, 2011).

Saudi English

Recent studies have discussed the grammatical errors in English by Saudis (Elyas, 2008, 2011; Mahboob, 2013; Alahmadi, 2014; Mahboob and Elyas, 2014; Osman, 2015; Khatter, 2019; Bukhari, 2021). Their approaches lie outside the scope of this study although many of the syntactic features that they tackle overlap with those found in our data in SE. According to Mesthrie and Bhatt (2008), the investigation of English varieties is not a modern approach as it began in the nineteenth century. They state that most English varieties were studied in isolation until the 1980s. Then, many pioneering scholars called these varieties of English “World Englishes”. Kachru is one of the important scholars in the field who received the main credit for founding this field of study. In a similar vein, Onysko (2022) state that “a range of studies have emerged along related strands of research concerned with the global spread and creation of Englishes (World Englishes),” where the spread of English, globalization, and explicit contact impact the “other languages and the influences that emerge from this contact” (p.1). A recent study by Bolton (2018) calls upon disciplinary debates and future directions in World Englishes. Globalization and language worlds have an immediate impact on World Englishes worldwide and contact with local languages (Bolton, 2013, 2019; Onysko, 2016). English is seen as a highly diversified language that appears in a multitude of different varieties and dialects across the globe (Siemund, 2013; Siemund et al., 2013, 2021; Vaicekauskien, 2020). In the Saudi context, we can find that the most directly related studies to Saudi English and World Englishes paradigm are those by Al-Rawi (2012); Mahboob (2013); Mahboob and Elyas (2014); Bukhari (2021), Elyas et al. (2021). In addition, there has been a growing scholarship in World Englishes in Arabian Gulf in recent years. The status of English in the Arabian Gulf was investigated and analyzed by many researchers such as Elyas and Mahboob (2021a), Hillman et al. (2021), Hopkyns et al. (2021), Siemund et al. (2021), Tuzlukova and Mehta (2021), and van den Hoven and Carroll (2021). A recent bibliography of World Englishes in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) has been documented by Elyas and Mahboob (2021b) stressing the importance of World Englishes by current research interests in the region.

Kachru (1985) succinctly proposed a model for World Englishes which consists of three circles of varieties. First, there are the Inner Circle varieties which involve native speakers of English as in the UK, the US, Australia, Canada, and New Zealand. Second, we find the Outer Circle varieties which involve second language Englishes such as those in Nigeria, Kenya, and India. Third, the Expanding Circle varieties refer to English as a Foreign Language (EFL) as in China, Egypt, and Saudi Arabia.

Se Studies Within the World Englishes Framework

Al-Rawi (2012) study investigated four syntactic properties of SE following the list of features found in Kortmann and Szmrecsanyi (2004), which are also relevant to the current study. The four syntactic features are, first, be deletion as in “They … not able to hear anyone”. The second feature is the insertion of the definite article the as in: “I prefer the fish”. The third feature is the omission of the indefinite article as in “When I grew older, I want to be doctor”. The fourth feature is the lack of subject-verb agreement as in “My father always teach me how to discover my capabilities”.

Mahboob (2013) and Mahboob and Elyas (2014) also studied SE and explored Middle East Englishes with a focus on SE. They studied the features of SE by examining high school textbooks and assumed that SE was regarded as a local variety having its own features. Al-Shurafa (2014) are related in the sense that the syntax of Arabicized English and its status in the Gulf are discussed at a wider level. Fallatah (2017) conducted a study that investigated bilingual creativity in SE. Elyas et al. (2021) studied SE and translanguaging in comedy clubs. Their findings identified several features of Saudi English bilingual creativity that can fall into certain categories and recurrent themes, for example, code-switching, syntactic and semantic creativity, translation, and lexical creativity. Elyas et al. (2021) argue that Saudi nationals have been using “simple English” with a local flavor of their “Saudi English” in their day-to-day communication as part of their translanguaging and mixing English with distinct Arabic linguistic repertoire creatively.

According to Kachru (1985), bilingual creativity is a linguistic process that results from the speakers' knowledge of two or more languages. In his study, he identified six forms of bilingual creativity reflected in the language of five comedians: code switching, syntactic variation, cultural reference, pronunciation shift, lexical variation, and semantic variation.

Methodology and Theoretical Framework

The methods used to collect data for this study are described in this section. Relevant demographic information about the participants and the number of the extracted expressions from the data for scrutiny are discussed.

Participants and Data

The data were collected from 139 educated male and female Saudis who speak English as a foreign language. Most participants learned English in school, starting in the intermediate stage when they were first exposed to English. Their age is between 18 and 44. There are 114 women and 25 men of different educational levels. One participant is a Ph.D. candidate, 15 participants have a Master's degree, 69 participants are in MA and B.Sc. programmes, 48 participants are from the preparatory year, and 6 are high school students who have not yet attended college. The participants have different academic degrees, including Medicine, Engineering, Nursery, Biology, Computer Science, Law, Business Administration, Kindergarten in Arabic and English. It is worth mentioning that 32 of the participants are majoring in English.

Data Collection

The data were obtained through three methods: spontaneous language, open-ended questions, and students' writings. First, language data were obtained from a chatting conversation among five friends in a WhatsApp group. They were discussing different topics of mutual interest. The participants were undergraduates majoring in English. Second, open-ended wh questions were given to participants, distributed in two ways. Four questions related to the participants' professions were sent to them via WhatsApp. The investigator sent these questions to 41 relatives and friends. Most of the participants answered orally by sending recordings of their speech while some of them sent written answers. Twenty-seven answers were recorded and transcribed by the researchers.

Open-ended wh questions were sent out via a questionnaire which was designed online using Google Forms. It consisted of several demographic questions and five questions relating to the participants' interests. The questionnaire was distributed through Facebook to Saudi academic groups, sent via WhatsApp, and shared with the staff at the Security Forces Hospital in Makkah. The number of participants obtained through this method was 54. However, only 49 of the respondents were used; four participants were excluded because they were not Saudi nationals, and one was excluded because her answers were written in Arabic. Twenty-nine sentences were extracted for this analysis. The problem with this method is that some participants gave short answers that only contained one or two words and some left questions unanswered.

The last method involved the collection of students' writings. The articles of 90 students studying in the preparatory year at college were collected. All of them were women, ranging in age between 18 and 21 years and studying various scientific courses besides the English language. They study English for 18 h a week and are either beginners or intermediate-level speakers. Beginners were asked by their English instructors to write short paragraphs about themselves to be read out in class, and they were collected immediately. Advanced-level students wrote about their favorite people and special celebrations. In total, 180 sentences were obtained for analysis. This method was effective because students wrote longer sentences which helped to elicit various features.

Data Analysis

The data were analyzed based on the structural categories of World Englishes that were presented in Mesthrie and Bhatt (2008). They divided the features found in World Englishes into two categories. The first category relates to the lexical and phrasal levels within the sentence while the second pertains to the clause level. The first category is divided into five subsections: noun phrase, verb phrase, prepositions, conjunctions, and wh-words. The second category is subdivided into nine sections within the clause level: word order, relative clauses, passive, comparison, tag questions, answers to yes/no questions, adverb placement, and other constructions that are limited to a few varieties (Mesthrie and Bhatt, 2008). In addition to Mestherie and Bhatt's classification, the data of this study was analyzed based on Kortmann and Szmrecsanyi (2004) scheme of categorization. On their list, they provided 76 features found in non-standard Englishes around the world. All of these features were listed under 11 major categories: pronouns, noun phrases, verb phrases, adverbs, negation, agreement, relativization, complementation, discourse organization, and word order (Kortmann and Szmrecsanyi, 2004, p. 1,146–1,148). The current study attempts to identify the syntactic characteristics of SE that were found in the collected data and examines those against the lists of the previous categories.

Results and Discussion

The syntactic characteristics found in the variety of SE are presented and discussed below. They involve divisions and subdivisions of noun phrase structures, verb phrase structures, prepositions, and clause structures. Related examples elicited by the participants are also provided.

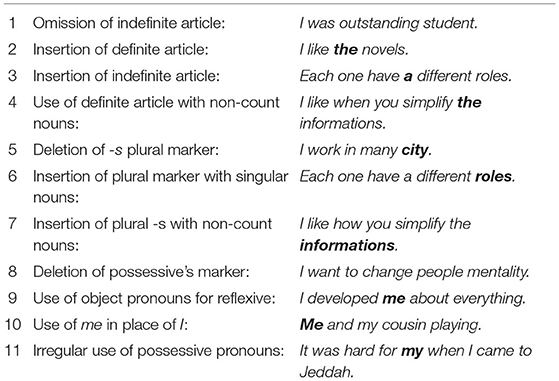

The Noun Phrase

Articles

Most participants demonstrated an irregular use of articles. For example, they tended to omit the indefinite articles a and an. This is a common feature of World Englishes. As illustrated in examples (1), (2), (3), and (4) below, the speakers omitted the indefinite articles:

(1) It is … international language.

(2) I was… outstanding student.

(3) I am… talented speaker.

(4) It is … hard question.

Interestingly, the speakers who uttered sentences (1) and (2) were majoring in English: the first speaker was a student pursuing a BA in English, and the second was a postgraduate student. The speakers of the last two sentences, (3) and (4), were majoring in other disciplines. The results of the first two methods, namely: natural speech and open-ended questions, were compared to the results from the third method (students' writings) because most participants involved in the first two methods were more educated than those involved in the third method. The students who participated in the third method were in their preparatory year of learning English. More examples are provided below where the indefinite article a/an are omitted:

(5) I am… student in the university KAU.

(6) She was…English student.

(7) She was …job assistant.

(8) I don't have… job.

Examples (5)–(8) exhibit the omission of a/an before the singular count nouns student, English student, job assistant, and job, respectively.

Moreover, the data showed that SE speakers used the article a before plural nouns, as examples (9) and (10) demonstrate.

(9) Each one have a different roles.

(10) I love watching a movies.

It is also observed that SE speakers tended to add indefinite articles even if the noun is preceded by an adjective modifier as in (9) above.

Another feature that was found in SE pertains to the redundant insertion of the definite article the, as illustrated in (11) – (15) below:

(11) I also like the novels.

(12) I believe that the women have their rights.

(13) I like cook and read the books.

(14) It is the very boring job.

(15) I like how you simplify the informations.

In examples (11), (12), and (13), the speakers inserted the before nouns, which is considered a deviation from Standard English. In (14), the definite article the was used irregularly, preceding the adverb very and defining a general noun “job”. The last example (15) was used by a participant of the third group who used the definite article the with the abstract noun information(s). This variation in the use of the definite article was also found in the syntax of many World Englishes (Mesthrie and Bhatt, 2008).

According to Al-Rawi (2012), SE speakers demonstrate this type of variation in their speech as a result of their native substrate effect. The system of the Arabic language does not involve the use of indefinite articles. Definiteness and the introduction of a topic that is already known to both interlocutors are expressed by the use of ?al- “the”.

Number

Participants also showed variation in their use of plural forms. Several SE speakers did not add the plural marker -s to pluralize nouns, as exemplified in (16) and (17). However, it is clear from the context of these sentences that plurality should be expressed, i.e., books and interests.

(16) I love reading book.

(17) Swimming, jogging, and cooking are my interest.

Moreover, a singular form of the noun is used instead of the plural form. In examples (18) and (19), the numerals one of and four before the nouns indicate that the respective nouns are plural. However, the plural marker -s was not used on the following noun as shown by the participants of the second group.

(18) I have four sister.

(19) One of my sister is married.

In (20)–(22), although participants used the quantifiers few, a lot, and many, the nouns that followed these quantifiers were expressed in the singular, as they were not marked with -s.

(20) There's few thing I'd like to change.

(21) A lot of thing.

(22) I work in many city.

In addition to plural -s omission, SE speakers may add the -s to singular nouns. According to Mesthrie and Bhatt (2008) this is called an overgeneralization of rules, as in (23).

(23) Each one have a different roles.

In (24), the plural form of the noun woman, which is women, is irregular, but the speaker did not change the noun and used the unmarked noun woman. The use of unmarked or singular nouns instead of the irregular form of the plural noun occurs a few times in the current data.

(24) Woman become as men.

In examples (25) and (26) below, the participants used the non-count nouns information and communication. In Standard English, these two nouns are uncountable and do not take plural -s. However, the data showed that SE speakers may add the plural marker -s to uncountable abstract nouns.

(25) I like how you simplify the informations.

(26) We have strong social communications.

The substrate system (L1) of the speakers' native language affected the use of the plural form by SE speakers. For example, the equivalent of the abstract nouns information and communication are considered countable nouns in Arabic. As a result, SE speakers tend to add plural markers to these nouns.

Possession

Within the current data, possessive's omission was not common. Only one example was found in (27) below:

(27) I want to change people… mentality.

In (27), the possessive marker on to the noun people is omitted. Interestingly, this sentence was produced by a female who majored in English and had knowledge of the language. This can be evidence that this feature requires more investigation in future studies. According to Mesthrie and Bhatt (2008), the possessive feature in New Englishes did not receive much attention. Platt et al. (1984) found that there is a deletion of's when New Englishes speakers express possession (as cited in Mesthrie and Bhatt, 2008), which is also common in African-American English.

Examples (28)–(33), below, indicate various features of possessive pronoun substitution, which is different from Standard English.

(28) My sister her name Waffa.

(29) My best friend she name is Amal.

(30) She name my mom is Souad.

(31) She name is Naem.

(32) She's name Aseel.

(33) My mother is name Misaa.

These substitutions are used many times by different speakers in the second group. In (28), the speaker substitutes the object pronominal her for possessive's, so my sister's name becomes my sister her name. In (29), the speaker uses the subject pronoun she instead of's. In both (30) and (31), the speakers use she to express possession but with different word orders. Interestingly, adding's to the pronoun she instead of adding it to the head noun. According to Lightbown and Spada (2013, p.47) “the possessive's is one of the grammatical morphemes that is not acquired early in the process of learning English”.

Pronouns

Variations in the use of pronouns are also found in SE as illustrated (34–42) below:

(34) My plan for the future to make me be better.

(35) I development me about everything.

(36) I know she in school.

(37) Correct me wrong thoughts.

(38) It was hard for my when I come to Jeddah.

(39) She name my mom is Souad.

(40) He name is brother Talal.

(41) Me and my cousin playing.

(42) Aseel it is my best friend.

In (34) and (35) above, the object pronoun me is used instead of myself . In (36), the pronoun she is used instead of the object pronoun her. SE speakers may use object pronouns in place of possessive pronouns. In (37) above, the participant uses the object pronoun me before the noun where the possessive pronoun my is expected to occur. In (38) above, the speaker uses the possessive pronoun my instead of me. In (39) and (40) above, the subject pronouns she and he are used instead of her and his, respectively. In (41) above, the object pronoun me is used instead of the subject pronoun I. Finally, in (42) above, it is inserted.

Table 1 below summarizes the SE characteristics in the nominal domain:

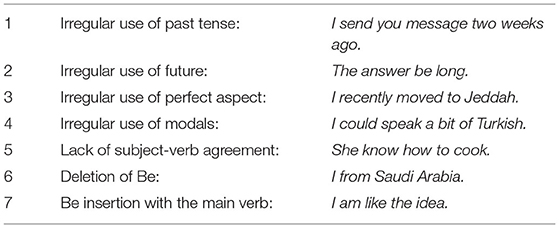

The Verb Phrase

Tense

Saudi English (SE) speakers, furthermore, showed variation in the use of different tenses. One of these features is the use of the unmarked verb in the past tense. This feature was frequently used in the speech of SE speakers. All the italicized verbs in the following examples are uninflected although they refer to temporal periods located before the moment of speaking.

(43) I just wake up.

(44) After finishing high school, I decide to major in English.

(45) I visit a lot of places.

(46) I was prepared and wear my simple make up and I do my hair.

(47) I send you message 2 weeks ago.

In (43), the speaker substituted wake up for the irregular past woke up. In (44) above, the speaker refers to a decision that was made in the past, as the context shows, and deleted the past marker -ed from the verb decide. In (45), the speaker talks about a trip that occurred in the past, but the verb is equally not marked with -ed. In (46) above, the speaker began the sentence in the past tense; then, the speaker used unmarked verbs in the following sentences. The speaker only used the -ed marker with the first regular verb, but did not use the irregular forms of wear and do and kept them unmarked. In (47), the speaker specified the time of the action as 2 weeks ago, which indicated that it happened in the past. However, the speaker used the unmarked verb send instead of the irregular form sent. This feature was used by SE speakers regardless of their educational levels.

Another variable use of tense marking occurs in reference to future time. According to Mesthrie and Bhatt (2008), speakers of World Englishes may use present and future tenses interchangeably. The data of the current study shows that there is no overlapping between present and future in SE. The following examples contain “will” to express the future tense, but the structure of their utterances was different from Standard English as in (48–51).

(48) I will be improve my English language.

(49) I will be finish from exams.

(50) I will to be hero nurse.

(51) The answer …be long.

In (48) and (49), the speakers added be to will to express the future tense. They added it to the sentence even though there is a main verb. In (50), the speaker inserted a redundant preposition. In (51), will was omitted by the speaker although she intended to use future tense.

Aspect

The perfect aspect in Standard English (have + past participle verb) is attested in the data. However, some World Englishes show variation in perfect aspect use. SE speakers, for instance, were also found to exhibit variation in aspectual usage, as in (52)–(55).

(52) I know her five years ago by accident.

(53) I recently moved to Jeddah.

(54) She never lie to anyone.

(55) Have you ever meet her?

(56) I don't fix my laptop yet.

In (52), (53), (54), (55), and (56) above, the speakers refer to aspectual events that started in the past and are still happening in the present by using the presents tense. In these contexts, the present perfect (have/has + past participle verb) is expected to be used instead of only the present or the past.

Modality

Modal verbs are used in English for the expression of the speaker's perspective. For example, it can say something about the “speaker's attitude toward the action that took place” [(Mesthrie and Bhatt, 2008), p. 64]. SE speakers showed variation in the use of modals. First, could is used in Standard English for the past of can which is used to express ability. Also, could is used to ask for permission. The participants of this study were found to use could instead of can. Variation in the expression of modality in SE is exhibited in (57)–(60).

(57) I could learn.

(58) I could speak a bit Turkish.

(59) We have strong social communications which could be good.

(60) They have should do a lot.

In (57), could is used to express her ability to learn something in the future. In (58), the speaker told the listener about her ability to speak Turkish. Both sentences are not in the past. However, the speakers used could to express their ability. SE speakers also used can instead of will to express future tense as (59) illustrates. In Standard English, may is used for probability, but it may be replaced with could in SE speech as in (59). The speakers in (60) insert the aspectual have next to the modal should.

Agreement

Lack of subject-verb agreement in the present tense is one of the most common features in many varieties of New Englishes (Mesthrie and Bhatt, 2008). It was also found as a common feature of SE based on the collected data of the current study.

(61) It give us insight for the truth.

(62) He always take me to the mall.

(63) She know how to cook.

(64) As my dad always say.

(65) He have a nice smile.

(66) She do not like animals.

(67) I knows her about 3 years.

(68) Dedication and honesty plays a big part.

Examples (61), (62), (63), (64), (65), and (66) show that the verb lacks the third person singular inflection to agree with the singular subject while in (67) and (68), the speakers add the inflection –s where it is not required. Al-Rawi (2012) points out that the non-standard agreement is highly frequent among SE speakers regardless of their level of education.

Forms of the Verb Be

Omission of the verb be is considered one of the commonly occurring characteristics of World Englishes in SE (Elyas, 2011; Al-Rawi, 2012; Mahboob, 2013; Mahboob and Elyas, 2014; Fallatah, 2017; Elyas et al., 2021). The current data also showed that participants delete copular be in the present tense as in the following examples:

(69) He… 10 years old.

(70) I… from Saudi Arabia

(71) We… good friends.

(72) I …… in the library.

(73) They …. twins.

(74) She ….. happy.

In (70)–(74), participants deleted the copular verb be that connects subjects with copulative complements.

Saudi English speakers further tend to drop the auxiliary be. The auxiliary be is an aspectual head that selects a progressive verb inflected with –ing as shown below.

(75) My father… working in King Abdulaziz University.

(76) She… doing her mother work.

(77) She… coming to me home.

Examples (75)–(77) show that participants drop the auxiliary form is before the progressive verbs working, doing, and coming.

Another form of auxiliary be, namely, the one preceding the passive verb is also deleted in SE as illustrated in (78) and (79).

(78) It should … done by all of us.

(79) He… saved by some of his teachers.

The sentences in (78) and (79) both lack the auxiliary be before the passive verbs done and saved.

Saudi English participants were also found to insert the verb be before the verbs in several sentences as manifested in the sentences below.

(80) It is seem that we cannot do it.

(81) He is read books every day.

(82) I am like the idea.

(83) We are totally agree with you.

Participants insert be where it is not expected to be used. In (80) and (81), is inserted. In (82), am is inserted. In (83), are is inserted.

Table 2 below summarizes the verb phrase characteristics in SE.

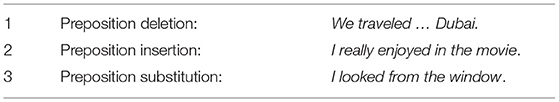

Prepositions

Saudi English speakers also showed variation in the use of prepositions in the current study.

(84) I went …. Makkah.

(85) I argue ….. the idea.

(86) I really enjoyed in the movie.

(87) He admitted by his mistake.

(88) I looked from the window.

Three types of variation are evident in (84)–(88). One type is the zero-use of the preposition. In (84) and (85), the preposition to is dropped, and in (86), the preposition for is dropped. Another type is the insertion of the preposition. In (86) and (87), in and by are inserted. The third type is the replacement of a preposition by another. In (88), the preposition through is being replaced by from. Table 3 summarizes SE characteristics of preposition use, which may indicate possible L1 influence as found in the data.

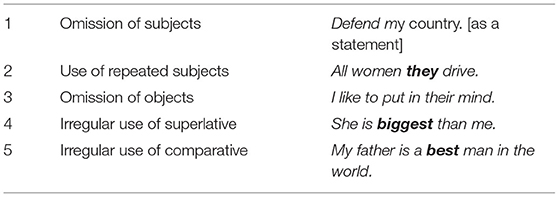

The Structure of SE Clauses

Omission of Subjects

Some SE speakers were found to omit the subject in the sentence, as in (89) and (90).

(89) Defend my country.

(90) She live in Makkah, but … come to Jeddah every day.

In (89), the speaker omitted the subject before the verb defend. In (90), the clause is left with a null subject before the verb come.

Use of Repeated Subjects

Participants repeat the subject by redundantly inserting a pronoun immediately after the subject.

(91) Men and women they have roles to play.

(92) All the women they drive.

In (91), although the speaker used coordinate subjects, the pronoun they is inserted after the subject forming a repetition of the subject. In (92), the subject (all the women) is followed by a redundant pronoun they that co-refers with the subject. This is a clear influence of the underlying L1 as in modern Arabic a subject pronoun is added after the subject to indicate an emphasis on the subject being discussed.

Omission of Objects

Saudi English speakers were also found to omit the object pronoun with transitive verbs. In (93), the participant left the place of the object empty as follows:

(93) I like … to put in their mind.

Comparative and Superlative Interchanging

The data also show variation in the use of comparative and superlative structures, as illustrated by the following examples.

(94) She is biggest than me.

(95) My father is a best man in the world.

First, the speaker in (94) applied the superlative in a comparative construction, as she added the morphological form -est to the adjective big. Second, the speaker in (95) used the indefinite article a instead of the definite article the when applying the superlative structure. However, these features were not frequently found in the collected data. As a result, further investigation is needed. Table 4 below summarizes the four characteristics found in our data in SE clauses.

Conclusion and Recommendation

To sum up, this study was conducted to identify the syntactic characteristics of SE which is considered an outer circle variety of World Englishes. This investigation examined the speech of several Saudi speakers in order to describe SE. The results of this study show that there are several grammatical characteristics in SE speech. In relation to noun phrases, it was found that speakers show variation in the use of articles, the plural, possession, and pronouns. In verb phrases, they showed variation in the use of tense, aspect, modality, number, and forms of be. SE speakers were also found to use prepositions differently from Standard English speakers as they delete, insert, and substitute prepositions. In relation to the structure of English clauses, SE speakers were found to omit subjects and objects, repeat subjects, and use comparative and superlative structures irregularly. These findings confirm the results found in previous studies in SE literature (Elyas, 2011; Al-Rawi, 2012; Mahboob, 2013; Al-Shurafa, 2014; Mahboob and Elyas, 2014; Fallatah, 2017; Elyas et al., 2021). Finally, further investigation is needed to elicit more syntactic characteristics of SE. Also, other aspects of language such as phonological and lexical features of SE need to be examined.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Author Contributions

TE and NAlS has worked on WE and Saudi English background, history, and paradigm. NAlo has collected the data. MA has done the analysis and conclusion. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Alahmadi, N. S. (2014). Errors analysis: A case study of Saudi learner's English grammatical speaking errors. Arab World Engl. J. 5, 84–98. Available online at: https://www.awej.org/images/AllIssues/Volume5/Volume5number4Decmber/6.pdf

Al-Haq, F. A. A., and Smadi, O. (1996). The status of English in the kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) from 1940-1990. Contrib. Soc. Lang. 72, 457–484.

Al-Rawi, M. (2012). Four grammatical features of Saudi English: charting the influence of Arabic on the syntax of English in Saudi Arabia. Engl. Today 28, 32–38. doi: 10.1017/S0266078412000132

Al-Shabbi, A. (1989). An Investigation Study of the Practical Preparation in EFL Teacher Preparation Programs in Colleges of Education in the Saudi Arabia (Unpublished PhD thesis), University of Wales, Cardiff.

Al-Shurafa, N. S. (2014). On the emergence of a gulf English variety: a sociocultural approach. Buckingham J. Language Linguistics 7, 87–100. doi: 10.5750/bjll.v7i0.924

Bolton, K. (2013). “World Englishes, globalisation and language worlds,” in Nils-Lennart Johannesson, Gunnel Melchers and Beyza Björkman, eds Of Butterflies and Birds, of Dialects and Genres: Essays in Honour of Philip Shaw (Stockholm: Acta Universitatis Stockholmiensis), 227–251.

Bolton, K. (2018). “World englishes: Disciplinary debates and future directions,” in The Routledge Handbook of English Language Studies, 1st Edn, eds P. Seargeant, A. Hewings, and S. Pihlaja (London: Routledge), 59–76.

Bolton, K. (2019). “World Englishes: current debates and future directions,” in The Handbook of World Englishes, 741–760. doi: 10.1002/9781119147282.ch41

Bukhari, S. (2019). Complexity Theory Approaches to the Interrelationships Between Saudis' Perceptions of English and Their Reported Practices of English (Doctoral dissertation, University of Southampton, UK).

Bukhari, S. (2021). English Language Teachers' Views on ‘Saudi English': errors vs. variants. Taibah University J. Arts Humanities 28, 464–496.

Elyas, T. (2008). The attitude of American English within the Saudi Education System. Novitas-ROYAL 2, 28−48.

Elyas, T. (2011). Diverging Identities: A'contextualised' Exploration of the Interplay of Competing Discourses in Two Saudi University Classrooms (Doctoral Dissertation, University of Adelaide, Australia).

Elyas, T., AlZahrani, M., and Widodo, H. P. (2021). Translanguaging and ‘Culigion' Features of Saudi English. World Englishes 40, 20–40. doi: 10.1111/weng.12509

Elyas, T., and Mahboob, A. (2021a). World Englishes in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA). World Englishes 40, 154–158. doi: 10.1111/weng.12504

Elyas, T., and Mahboob, A. (2021b). Englishes in MENA region: a contemporary bibliography. World Englishes 40, 290–296. doi: 10.1111/weng.12515

Elyas, T., and Picard, M. (2010). Saudi Arabian educational history: impacts on English language teaching. Educ. Business Soc. 3, 24–40. doi: 10.1108/17537981011047961

Elyas, T., and Picard, M. (2013). Critiquing of higher education policy in Saudi Arabia: Towards a new neoliberalism. Educ. Business Soc. 6, 31–41. doi: 10.1108/17537981311314709

Elyas, T., and Picard, M. (2018). “A brief history of english and english teaching in Saudi Arabia,” in English as a Foreign Language in Saudi Arabia (New York, NY: Routledge), 70–84.

Elyas, T., and Picard, P. (2012). Teaching and Moral Tradition in Saudi Arabia: A Paradigm of Struggle or Pathway towards Globalization? Procedia 41, 1083–1086. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.06.782

Fallatah, W. (2017). Bilingual creativity in Saudi stand-up comedy. World Englishes 36, 666–683. doi: 10.1111/weng.12239

Hillman, S., Selvi, A. F., and Yazan, B. (2021). A scoping review of world Englishes in the Middle East and North Africa. World Englishes 40, 159–175. doi: 10.1111/weng.12505

Hopkyns, S., Zoghbor, W., and Hassall, P. J. (2021). The use of English and linguistic hybridity among Emirati millennials. World Englishes 40, 176–190. doi: 10.1111/weng.12506

Kachru, B. B. (1985). “Standards, codification and sociolinguistic realism: the English language in the outer circle,” in English in the World: Teaching and Learning the Language and Literatures, eds R. Quirk and H. G. Widdowson (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 11–30.

Khatter, S. (2019). An analysis of the most common essay writing errors among EFL Saudi female learners (Majmaah University). Arab World Engl. J. 10, 364–381. doi: 10.24093/awej/vol10no3.26

Kortmann, B., and Szmrecsanyi, B. (2004). “Global synopsis: Morphological and syntactic variation in English,” in A Handbook of Varieties of English: A Multimedia Reference Tool. Volume 1: Phonology. Volume 2: Morphology and Syntax, eds B. Kortmann and W. E. Schneider (Berlin; Boston, MA: De Gruyter Mouton). doi: 10.1515/9783110197181

Kortmann, B., and Szmrecsanyi, B. (2009). The morphosyntax of varieties of English worldwide: a quantitative perspective. Lingua 119, 1643–1663. doi: 10.1016/j.lingua.2007.09.016

Lightbown, P. M., and Spada, N. (2013). How Languages are Learned, 4th Edn. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Mahboob, A. (2013). Englishes of the Middle East: a focus on the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Middle East Handbook of Applied Linguistics 1, 14–27.

Mahboob, A., and Elyas, T. (2014). English in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. World Englishes 33, 128–142. doi: 10.1111/weng.12073

Mesthrie, R., and Bhatt, R. M. (2008). World Englishes: The Study of New Linguistic Varieties. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Onysko, A. (2016). Language contact and world Englishes. World Englishes 35, 191–195. doi: 10.1111/weng.12190

Onysko A; and Siemund, P. (2022). Englishes in a Globalized world: exploring contact effects on other languages. Front. Commun.

Osman, M. A. A. R. (2015). Analysis of Grammatical Errors in Writings of Saudi Undergraduate Students (Doctoral dissertation). Sudan University of Science and Technology, Sudan.

Siemund, P. (2013). Varieties of English: A Typological Approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9781139028240

Siemund, P., Al-Issa, A., and Leimgruber, J. R. (2021). Multilingualism and the role of English in the United Arab Emirates. World Englishes 40, 191–204. doi: 10.1111/weng.12507

Siemund, P., Gogolin, I., Schulz, M. E., and Davydova, J. (2013). Multilingualism and Language Diversity in Urban Areas: Acquisition, Identities, Space, Education, Vol. 1. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing. doi: 10.1075/hsld.1

Tuzlukova, V., and Mehta, S. R. (2021). Englishes in the cityscape of Muscat. World Englishes 40, 231–244. doi: 10.1111/weng.12510

Vaicekauskien,e, L. (2020). The social meaning potential of the global english based on data from different communities. Taikomoji kalbotyra 14, 183–208. doi: 10.15388/Taikalbot.2020.14.13

Keywords: Saudi English, syntactic features, World Englishes, language in contact, English in Saudi Arabia

Citation: AlShurfa N, Alotaibi N, Alrawi M and Elyas T (2022) English Features in Saudi Arabia: A Syntactic Study Within the World Englishes Framework. Front. Commun. 7:753135. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2022.753135

Received: 18 August 2021; Accepted: 09 February 2022;

Published: 11 March 2022.

Edited by:

Peter Siemund, University of Hamburg, GermanyReviewed by:

Paolo Lorusso, University of Florence, ItalyAlejandro Javier Wainselboim, CONICET Mendoza, Argentina

Copyright © 2022 AlShurfa, Alotaibi, Alrawi and Elyas. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Tariq Elyas, dGVseWFzQGthdS5lZHUuc2E=

Nuha AlShurfa

Nuha AlShurfa Norah Alotaibi2

Norah Alotaibi2 Maather Alrawi

Maather Alrawi Tariq Elyas

Tariq Elyas