- 1School of Professional Communication, Ryerson University, Toronto, ON, Canada

- 2Graduate School of Social Sciences, Hitotsubashi University, Tokyo, Japan

Over the last few decades, self-injury has gained wide visibility in Japanese popular culture from manga (graphic novel), anime (animation), to digital games and fashion. Among the most conspicuous is the emergence of menhera (a portmanteau of “mental health-er”) girls, female characters who exhibit unstable emotionality, obsessive love, and stereotypical self-injurious behaviors such as wrist cutting. Tracing the expansion of this popular cultural slang since 2000, this conceptual article explores three narrative tropes of menhera—the sad girl, the mad woman, and the cutie. Within these menhera narratives, self-injury functions as a self-sufficient signifier of female vulnerability, monstrosity, and desire for agency. These menhera tropes, each with their unique interpretation of self-injury, have evolved symbiotically with traditional gender norms in Japan, while destabilizing long-standing undesirability of sick/detracted female bodies. The menhera narrative tropes mobilize cultural discourses about female madness and subsequently feed back into the social imaginaries, offering those who self-injure symbolic resources for self-interpretation. We argue that popular cultural narratives of self-injury like menhera may exert as powerful an influence as clinical discourses on the way we interpret, make sense of, and experience self-injury. Being attentive to cultural representations of self-injury thus can help clinicians move toward compassionate clinical practice beyond the medical paradigm.

Introduction

Self-injury, intentional damaging of one's body without a clear suicidal intent, is an enigmatic behavior that breaches boundaries between sanity and madness, physical and mental health (Chandler, 2014). Images of self-injury now surround us, along with voluminous narratives of mental ill-health1 in popular media. Studies have documented the growing number of self-injury portrayals across popular media including films (Chouinard, 2009; Trewavas et al., 2010; Danylevich, 2016; Bareiss, 2017), TV shows (Whitlock et al., 2009), young adult fiction (Miskec and McGee, 2007) and comics (Seko and Kikuchi, 2020). Alongside mass media, interactive and visual-rich social media platforms have enabled instant sharing of user-generated self-injury content at an unprecedented speed and scale (Seko, 2013; Seko and Lewis, 2016; Alderton, 2018).

While self-injury, with its enhanced visibility, touches many people's lives, the perceived meanings ascribed to this practice vary widely. Research on media portrayals of self-injury has revealed a range of implicit and explicit meanings attached to this practice, including emotional regulation, self-punishment, coping mechanism, interpersonal manipulation, self-affirmation, or resistance to oppression (Danylevich, 2016; Bareiss, 2017; Seko and Kikuchi, 2020). Although what self-injury means to the person varies across media narratives, there is a recognizable pattern in who engages in this practice. Studies indicate that self-injuring characters in popular media are predominantly female adolescents who self-cut (Whitlock et al., 2009; Trewavas et al., 2010; Radovic and Hasking, 2013). This portrayal reflects and reproduces the medical discourse that has historically associated self-injury with young women and an act of cutting (Brickman, 2004; Millard, 2013).

A body of critical sociological research illuminates the long-standing association between self-injury and femininity in clinical literature in which female mental fragility and irrationality is contrasted to the aggressive and violent male pathology (e.g., Millard, 2013). Statistical “facts” have cemented this “gendered paradox” in suicide (Canetto and Sakinofsky, 1998), namely, women have higher rates of suicidal ideation and non-fatal suicidal behaviors, whereas suicide mortality is higher for men than women. In modern psychiatry, female self-cutting has thus been framed as a “delicate,” non-fatal self-injury (Brickman, 2004) that resonated closely with gendered cultural norms on how women should act with and through their bodies. Chandler and Simopoulou (2021), in their arts-based participatory study, contend that self-inflicted injuries on a female body are often read differently than the same injuries on a male body. Violence acted by women on their bodies elicits “shock, disbelief, disgust,” thereby leading to immediate pathologization (p. 8).

To date, published research in English on media representations of self-injury has focused almost exclusively on the Anglophone content, paying little attention to non-Anglophone portrayals of self-injury and the role popular media may play in shaping cultural understanding of this practice. However, self-injury has been explicitly thematized in Japanese popular culture over the last few decades. In a previous study, we conducted an extensive search of slice-of-life2 manga (graphic novels) published between 2000 and 2017 portraying self-injury in everyday life context (Seko and Kikuchi, 2020). Across 15 manga we examined, the characters engaging in self-injury were predominantly young women cutting themselves to cope with feelings of despair, loneliness, or emotional numbness, replicating research on Anglophone media. However, there were two contrasting perspectives toward young girls who self-injure. On one hand, in manga targeting young girls (shōjo manga), characters engaging in self-injury were primarily protagonists of the narrative who choose self-injury as a maladaptive coping strategy against external pressures (e.g., bullying, oppressive parents). On the other hand, manga targeting adult male readers (seinen manga) portrayed women who self-injure as mentally vulnerable, attractive, and helpless mistresses waiting to be rescued by male protagonists. Notably, many of those female characters in seinen manga were called menhera (a portmanteau of “mental health-er”) that exhibited unstable emotionality, impulsivity, and sexual promiscuity, along with stereotypical self-injurious behaviors, most often recurrent wrist cutting without a clear suicidal intent (Seko and Kikuchi, 2020).

It was around 2014 that we became aware of menhera's growing visibility in the Japanese popular cultural landscape, not only in manga, but also across anime (animation) video games, fashion, and character merchandise. Building on our previous study (Seko and Kikuchi, 2020) and our continuous observation of Japanese popular culture over the past decade, this article provides an initial thought on the emergence of menhera narrative tropes, focusing on how self-injury is constructed, appropriated, and repurposed as a metonymy of female madness. We offer a typology of menhera by describing the three prevailing narrative tropes: the sad girl who adapts the menhera label to self-pathologize their mental angst, the mad woman who exhibits pathetic obsession over her love interest, and the cutie who playfully performs subcultural “sick-cute” aesthetic through fashion. As we will be discussing, these narrative tropes are not mutually exclusive nor occurring discretely; instead, they often converge and inflect one another within one single character and across diverse popular cultural products. We contend that these menhera tropes, each with their unique interpretation of self-injury, have evolved symbiotically with the long-standing gender norms in Japan, weaving a complex net of meanings within which female madness is pathologized, fetishized, and performed.

Although this article focuses on a Japanese cultural slang as a case in point, our aim is not to ignite an Orientalist discourse around Japanese culture as exotic or peculiar. Rather, given that Japanese manga, anime, games, fashion and other popular cultural texts and artifacts have now reached far beyond Japan and exercise significant influences on the cultural landscapes of Asia, North America, and Europe, we aim to ponder on representations of self-injury in popular culture and extrapolate their potential clinical and research implications. In so doing, this article aims to join the growing critical discussion on popular culture's contribution to “pathologization from below” (Brinkmann, 2014), a process in which popular culture provides a set of semiotic and material practices that shape people's interpretations, feelings, and experiences of mental ill-health. We argue that popular cultural narratives of self-injury like menhera may exert as powerful an influence as clinical discourses on the way we interpret, make sense of, and engage with self-injury.

Typology of menhera

The Origin

The slang menhera was reportedly spawned on the mentaru herusu ban (mental health board)3, one of the anonymous discussion boards at a massive online community 2-channel4. The mental health board facilitated discussions featuring a wide range of mental health issues including depression, mania, mood disorders, and trauma, among others. Regular users of the discussion board exchanged information about medications, therapies, or local healthcare providers, vented their pent-up feelings, and shared emotional support through anonymous postings. In October 2016, 090, a columnist for an online support network menhera.jp, conducted extensive archival research on 2-channel to trace the origin of the term menhera. The earliest use of the term dated back to August 2000 when the regulars of the board started describing their community as menheru ban, using an abbreviation of mentaru herusu (mental health) (090, 2016a). The abbreviation quickly spread among the board members who started calling themselves “menhera” (mental health-er) with the suffix “-er” to indicate their membership to the board. The initial use of the term “menhera” thus referred to the board members who self-identified themselves as living with some form of mental ill-health regardless of their diagnosis, gender, and age.

Since the onset of the mental health board, the topic of self-injury has been discussed sporadically among the members. Our observation of the oldest 6,907 threads on the 2-channel mental health board (between November 1999 and July 2001)5 suggests that there were at least 40 threads featuring the topic of self-injury, with the most prominent topic being risuka (wrist cutting). The messages posted on these threads entailed a complex set of cutting-related disclosures and advice: some turned to the board to report that they had just self-injured, while others asked for tips to hide scars. Some looked for advice on how to suppress the urge to cut, how to cut safely, or how to support significant others engaging in self-cutting. Notably, none of the 3,792 posts to the 40 threads featuring self-injury included the term menhera, which indicates that the link between self-injury and menhera was not explicitly established at the dawn of this online slang.

Later, the term menhera extended from the mental health board to the broader 2-channel community. According to 090 (2016a), users of other 2-channel boards began using the term around 2003 to refer to the regulars of the mental health board or persons living with mental ill-health in general. By 2005, the term appeared on one of the most popular boards nyūsoku VIP ban (newsflash VIP board)—notorious for vibrant discussions filled with insider jokes, slander, hate speech, and misogynist remarks. It was likely on the nyūsoku VIP ban when the term menhera was first explicitly linked to women in a pejorative manner. 090 (2016b) identified the emergence of a term menhera onna (menhera woman) on the nyūsoku VIP ban which disparagingly referred to women who engage in “pathetic” acts such as extreme mood swings, risky sexual behaviors, and self-injurious acts. One potential reason for this pejorative and gendered connotation was the perceived equation of menhera with persons living with borderline personality disorder (BPD) 090 (2016b). BPD is predominantly diagnosed in females (Grant et al., 2008) and is highly stigmatized within medical communities as “manipulative,” “demanding,” and “attention seeking” (Aviram et al., 2006). By 2008, the term came to derogatively refer to women with “BPD-like” behaviors as troublesome attention seekers from whom “normal” people should keep their distance 090 (2016b).

With the rapid growth of the Japanese digital landscape, the term menhera and its gendered connotation has expanded from the 2-channel subculture to a wider sea of the internet and merged into the mainstream popular culture6. In May 2021, we searched the term “menhera” in three digital databases for Japanese manga, anime, and games: the Japan National Diet Library's online catalog (http://www.ndl.go.jp/), the Japanese Agency for Cultural Affairs' media arts digital archive (https://mediaarts-db.bunka.go.jp), and Kyoto International Manga Museum's Manga Repository (http://mmsearch.kyotomm.jp/index_j.html). We also searched the term on the App Store (iOS) and Google Play Store (Android) to identify potential gaming apps and visited several online communities featuring Japanese popular culture including 5-channel. Our search identified 27 unique books (14 manga, 7 novels, 6 non-fictions) and 5 gaming apps with the term “menhera” in their titles, all of which were published in or after 2012. This echoes the study by Terada and Watanabe (2021) who assessed public interest in menhera using Google Trends to evaluate how frequently the term was queried on Google's search engine. They identified that the number of searches rose significantly during 2010-2011 and continued steadily increasing until the time of their writing (January 2021). Despite the fast-paced changes on the internet, this slang has stuck around for a decade and become part of everyday lexicon in Japan, generating three narrative tropes to which we now turn.

The Sad Girl

The first menhera narrative trope is the sad girl7, a young woman who struggles with feelings of anxiety, low self-esteem, hopelessness, and loneliness. This narrative focuses on the inner turmoil of girls living with mental angst expressed through a first-person narration of some kind. The sad girl narrative itself pre-dates menhera. Since the 1990's, when the Japanese economy suffered a prolonged recession, narratives of psychosocial angst have manifested widely in Japanese popular culture. The term ikizurasa (pain of living) has been used to denote anxiety experienced by many Japanese Millennials struggling with a sense of disconnectedness and self-blaming (Nae, 2018), caused by a vast array of issues from unemployment, poverty, family problems to bullying, social withdrawal and mental ill-health (Kido, 2016). The internet, with its relative anonymity, has provided a haven for people living with life struggles, including those who engage with self-injury. The advancement of user-friendly social media platforms has further provided a fertile ground for ikizurasa monologs to grow and multiply.

The term menhera, with its association with femininity, has a considerable appeal to young women struggling with ikizurasa. One of the earliest examples is an indie manga titled Menhera-chan written by then 14-year-old Kotoha Toko8 who started posting an autobiographical manga on her personal website around 2010. With the support from a professional editor who discovered her website, Kotoha published the manga in two-volume book format (Kotoha, 2012). In this coming-of-age manga, the female protagonist Menhera-chan (“the menhera girl”) is a junior high school student experiencing long-term school refusal and social withdrawal due to undiagnosed depression. Two other main characters, Kenkou-kun (“the healthy boy”) and Byoujaku-chan (“the frail girl”), become friends with Menhera-chan and offer her emotional support and encouragement. Although Menhera-chan does not engage in self-injury, there are repeated references to suicide by overdose and self-strangulation that provides a strong link between menhera and self-destructive acts.

When asked why she wrote Menhera-chan, Kotoha commented in an interview:

“When I looked around myself, I realized that there were quite a few people who easily cry or feel hurt. People who live normally may wonder about these people like ‘Why do you cry over such a small thing?' or tell them ‘Don't feel hurt by such a thing!' But even those who think they have nothing to do with ‘menhera' never know who would become the one, and indeed some people may step in the realm before they know it. This is why I wrote Menhera-chan with the hope that readers would think ‘Ah, I can relate' or ‘I can understand Menhera-chan's feelings”' (Da Vinci News, 2013).

For Kotoha who has personally experienced bullying and social withdrawal, menhera is a liminal state of being that anyone can “step in” at any time. This subtle normalization proposes an antithesis to the prevailing marginalization of social misfits who, due to various reasons, deviate from the mainstream Japanese career and life path of getting a stable job, having a family, and becoming a responsible citizen (Nae, 2018). Nevertheless, by naming the protagonist Menhera-chan, the author explicitly pathologized the prevailing ikizurasa among young women. Menhera girls “easily cry or feel hurt” because of their morbid individual pathology, which should be frowned upon and discouraged by “people who live normally.” It is also noteworthy that this manga ends with the protagonist overcoming her long-term school refusal and attending a part-time high school. By describing the protagonist's gradual return to the normative social trajectory, Kotoha (2012) frames the mentally unhealthy girlhood as part of the passage to adulthood—which can be managed with time and optimal support from significant others.

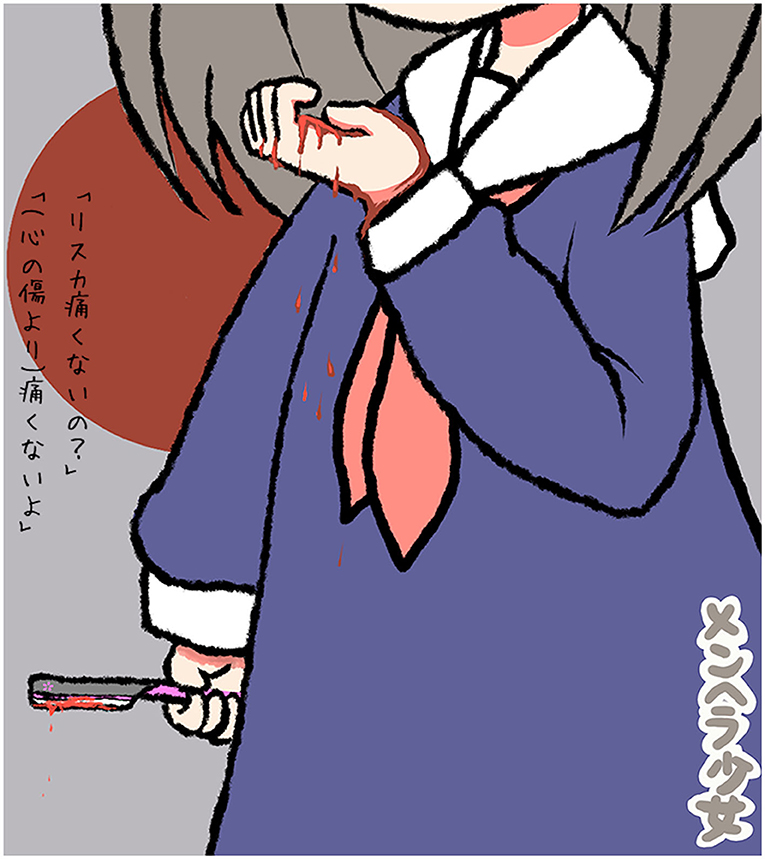

Another notable sad girl narrative comes from a series of graphic narratives posted on Twitter by a young illustrator Momose Asami under the username @menherashoujo (menhera girl). Since 2013 Momose has tweeted one illustration a day, featuring a mouthless girl in a sailor suit (school uniform). Unlike Kotoha (2012) manga which is drawn in a comic strip format, Momose's work is a single panel comic that depicts a girl suffering loneliness, sadness, and despair. Most images are accompanied with a few spoken lines of the menhera girl's monolog or a short dialogue between her and anonymous others who seemingly do not understand what the girl is struggling with. Although it is not described whether the menhera girl has a diagnosable mental disorder or what is causing her angst, self-injury (wrist cutting) is depicted as a way for the menhera girl to cope with inner pain or to manage a dissociative feeling to make sure she is still alive (Figure 1). As of May 2021, Momose's Twitter account has over 85,000 followers and the collection of her illustrations was published in a book titled “The Voice of a Gray Girl” (Momose, 2016).

Figure 1. “Doesn't wrist-cutting hurt?” “It doesn't hurt (as much as my heart).” A graphic narrative posted on Twitter by Momose Asami (@menherashoujo). Image reproduced with permission from the author.

These sad girl narratives indicate that the slang provided the creators with a relatively neutral and all-encompassing label to portray contemporary Japanese girls struggling with the pain of living. It deserves attention that the sad girl menhera embodies stereotypical Japanese femininity, such as submissiveness, self-control, and free of selfishness. Momose (2016) mouthless character eloquently suggests that the menhera girl suffers in silence; everything we see and hear about her is through her inner monolog filled with despair and distress, but she has no voice to raise. Self-injury is depicted as a means to externalize and cope with her inner pain, rather than communicating her angst to others. Momose's depiction of the menhera girl as a “gray girl” is particularly telling in this regard. In her study on media portrayals of eating disorders and self-harm among Japanese women, Hansen (2011) asserts that women in contemporary Japan often face “the paradox of navigating contradictive femininity in a gray zone between the normal and the disordered” (p. 57). To be “the good and clean girl” requires Japanese women to exercise rigid self-control over their bodies to “suppress the evil” in themselves (Hansen, 2011, p. 61). In the sad girl narratives, self-harming actions such as self-induced regurgitation, starvation, and self-cutting are portrayed as a borderline disordered act performed by young women attempting to navigate the contradictive femininity.

Paradoxically, the link between menhera and stereotypical femininity has resulted in menhera's sudden upsurge in popularity, particularly within manga/anime targeting male audiences. For example, Last Menhera (Amano and Ise, 2016) is a seinen manga (young male comic) that follows a high school boy falling in love with a beautiful classmate who self-cuts (Figure 2). Throughout the story, the heroine engages in recurring wrist slashing to “endure the pain of living” and “postpone the decision [to commit suicide]” (Amano and Ise, 2016, p. 56) which leads other characters to label her menhera. The male protagonist pretends that he, too, self-injures to attract her attention and affection. Through the protagonist's male gaze, the heroine's scarred body becomes the object of affective consumption wherein self-injury symbolizes her vulnerability, helplessness, and deformity, which altogether constitutes a twisted sexual appeal (Seko and Kikuchi, 2020).

Figure 2. Last menhera (Amano and Ise, 2016) features a male protagonist who falls in love with a menhera girl. Image reproduced with permission from the publisher Futaba-sha.

The Mad Woman

Whereas, the sad girl narrative domesticates female madness as vulnerable and potentially erotic, the mad woman exaggerates her abnormality and derangement, particularly in the context of romantic relationships. In this narrative, the menhera is obsessed with her love interest and makes devastating efforts to be with this person. Intriguingly, in many manga, anime, and games, menhera girls are first introduced as cute, loveable, and nurturing to their love interests. However, when a third person gets into the equation, their insecurity manifests as possessive thoughts and actions, overprotectiveness, and extreme jealousy that appears eccentric and terrifying to others (Kato, 2018). Unlike the sad girls who walk a tightrope between the normal and the disordered, the mad woman firmly inhabits the realm of madness.

In the mad woman menhera narrative, self-injury is often depicted as an act of interpersonal manipulation. For example, in her autobiographical self-help book titled “All Girls are Menhera,” self-identified “former” menhera Suisui (2020) reflects her wrist cutting as motivated by an intense fear of abandonment. Whenever she needed reassurance, she self-cut in front of her boyfriend or sent him photos of her bleeding wounds. Although Suisui (2020) does not specify whether she had a diagnosable disorder, this self-mockery reflects the long-standing negative stereotype attached to people with BPD, the connotation first established in popular 2-channel threads and expanded to mainstream popular culture—menhera as troublesome attention seekers (090, 2016b). The mad woman may also commit violence toward others, from verbal aggression to physical expressions, to perform her devotion to the beloved. Across recent manga, anime, and games, menhera girls are frequently portrayed as holding a sharp weapon indicating that their jealous aggression can be easily turned onto others (for an example of this caricature, see Kurii, 2016)9.

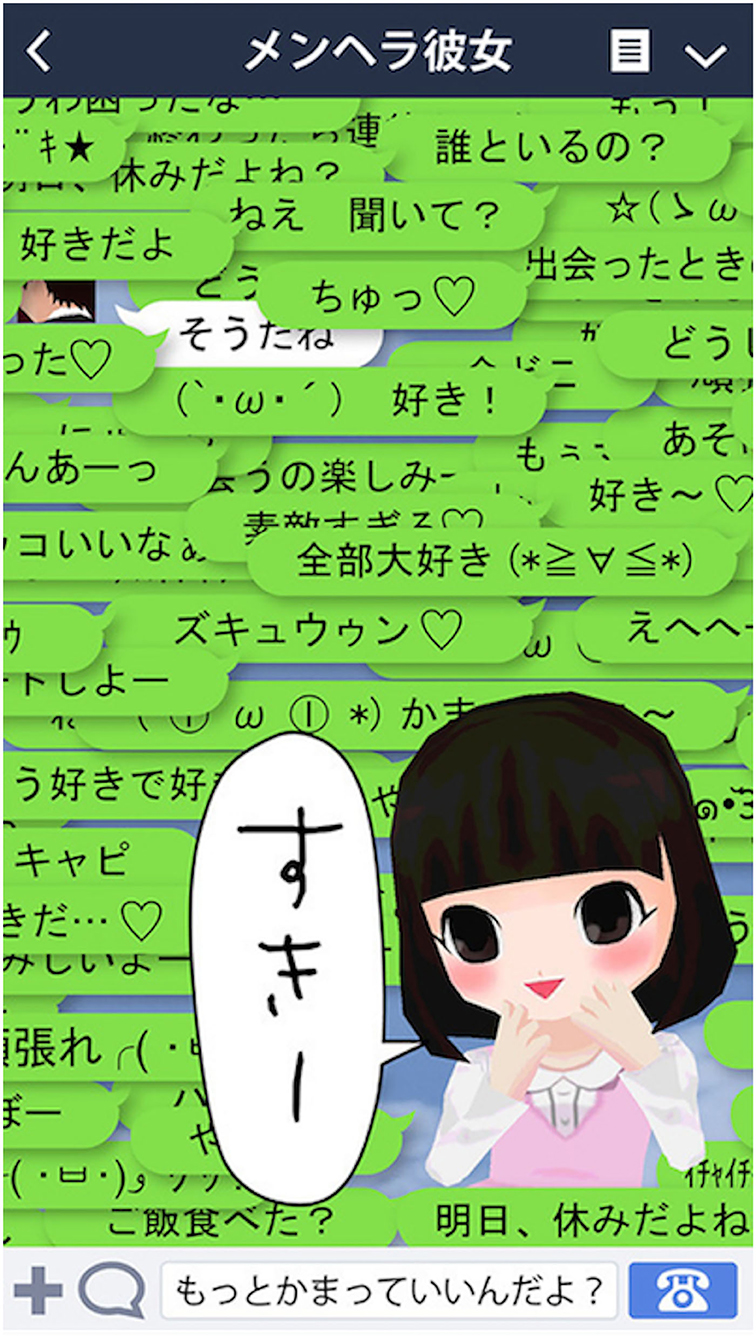

Another salient and stereotypical caricature of the mad woman takes the form of her obsessive communication style. Menhera girls are often portrayed as engaging in digital stalking through relentless texting and social media monitoring to check their lovers' whereabouts and make sure they are always within reach. This “pathetic” behavior has become the subject of mockery and even gamification. For example, in 2016 rock band Mio Yamazaki released an Artificial Intelligence (AI) named Menhera Girlfriend as part of a promotional campaign for their new album (http://ai-girl-mio.jp/). This program allowed users to chat with a bot that sends sarcastic and depressive messages representative of menhera personality. If a player does not respond quickly, the AI would text “Why don't you respond?” “Don't you love me?” or “Do you mean I should die?” imitating a menhera girl going emotionally awry.

Similarly, a mobile gaming app named “Menhera Girlfriend and One Million Text Messages” features obsessive texting between a menhera girl and her boyfriend (Figure 3). In this game, the player takes the role of a menhera girl and sends an excessive amount of text messages to her boyfriend. The player earns points as they send a text and can exchange points for items and decorations. Items are saturated with satire and dark humor, including surveillance cameras that help monitor the boyfriend 24/7, or an assassin to eliminate any person who has a crush on the boyfriend. Launched in February 2014, the gaming app has reached 500,000 downloads in <1 year (Happy, Gamer Inc, 2015)10.

Figure 3. A screenshot of mobile game “menhera girlfriend and one million messages.” The green speech bubbles represent excessive amounts of text messages from the menhera girlfriend character. Image reproduced with permission from Happy Gamer Inc.

In these examples, the narrative trope is deployed in ways that disdain and embellish the girl, isolating “pathetic” behaviors within the individual. Whether she is struggling with mental ill-health no longer matters—the emotional blackmailing, obsessive texting and manipulative self-injury alone prove she is a menhera. Further, the mad woman embodies a dualism between gender norms and deviation from them. On one hand, she opposes normative gender constructions by exhibiting aggression and violence historically associated with stereotypical masculinity. Her obsessive and assertive behavior appears frightening, immoral, and unfeminine. Yet on the other hand, her character trait still resonates with normative femininity in that her obsession with the beloved, albeit distasteful, can be seen embodying a feminine value of selfless devotion. In this regard, the mad woman menhera trope represents what Chouinard (2009) calls “postmodern monstrosity” associated with female madness. Analyzing film portrayals of mad womanhood, Chouinard (2009) argues that mad women are depicted as horrific because they evoke deep-seated fears that “the monstrous other is always already inside the self” (p. 799). Similarly, the menhera girl simultaneously embodies the menace long associated with mental ill-health and the all-too-human desire to love, care for, and nurture. With the innate moral and aesthetical ambiguity, she becomes a postmodern monster.

The Cutie

The final narrative trope is the cutie who embodies an emergent aesthetic of yami-kawaii (sick-cute), a subculture originating in Harajuku, a district in Tokyo known as the mecca of youth countercultures (Refinery29, 2018). As a portmanteau combining yami (sick, dark) with kawaii (cute), yami-kawaii mixes traditional cute elements with dark and grotesque motifs; pink hearts, strawberries, fluffy stuffed animals are juxtaposed with knives, blood splatters, hangman's nooses, syringes, pills, as well as suicidal slogans and swearwords (Refinery29, 2018). Practitioners of yami-kawaii fashion often feign injury by wearing bandages and eye patches or carrying syringes and needles as accessories. Yami-kawaii makeup emphasizes a mental illness motif, including “sickly pale” foundation and red blush-lined eyes to make them “look like swollen from crying” to express the mental angst and “the need of comfort” (Terada and Watanabe, 2021). At the heart of this girl's subculture lies a proposition: menhera is cute.

Illustrator Ezaki Bisko is often credited to have popularized the yami-kawaii movement through his character Menhera-chan. Created in 2013 as a simple doodle posted on Twitter, the character has quickly gained popularity and expanded into a manga series on Pixiv, an illustration-based online community (Ezaki, 2018). The manga features a group of schoolgirls who transform into justice heroines by slashing their wrists with a magical box cutter. The protagonist Menhera Pink and other “risuka senshi (wrist cut warriors)” are big-eyed, lovely-faced girls in pastel-colored sailor suits with their wrists bandaged (indicating self-injury). They fight evil spirits that lure people into derangement, while concealing their real identities (i.e., ordinary schoolgirls) during the day (Ezaki, 2018). It imitates the magical girl fantasy, a well-established manga/anime genre that features metamorphosis that turns an ordinary girl into a super powered alter ego.

Although it follows the convention of the magical girl genre, the cutie menhera strategically disrupts traditionally innocuous kawaii culture through its encapsulation of mental angst and re-appropriation of self-injury. The portrayal of wrist cutting as a ritual for transformation is deliberate and provocative, oozing with dark humor. It is neither a red-flag symptom of mental morbidity nor a gesture of interpersonal manipulation, but a simple means of magical transformation to defeat evil spirits/mental illness. The menhera girls are not mad or deranged, because mental illness has been detached and externalized as villains and it is their mission as justice warriors to defeat the evil. Rather than romanticizing or pathologizing self-injury, they calmly slash their arms to do their job.

From its onset, the cutie menhera narrative has been accompanied by a unique material culture. Ezaki Bisko has produced various character merchandise featuring Menhera Pink and fellow wrist cut warriors since 2014. Many of the frilly, pastel-colored clothing and kitsch accessories carry provocative messages like “kill you,” “sick,” or “death” representing the duality of yami kawaii aesthetic (Refinery29, 2018). Among the Menhera-chan merchandise, the most controversial was the “risuka bangle” (wrist-cut bracelet) that emulated gaping wounds caused by self-cutting. Produced by an indie brand Conpeitou in collaboration with Ezaki in October 2014, the bracelet was sold out quickly. The brand then made an announcement of a resale on Twitter in June 2015 (Conpeitou, 2015a). However, this time it caused a storm of criticism on social media, resulting in immediate discontinuation of the product (Conpeitou, 2015b). On the company's blog, the designer commented that they, too, had a long-term experience with self-injury and apologized to those who were offended by the idea of treating self-injury as a fashion item (Conpeitou, 2015b).

Whereas, the wrist-cut bracelet and other Menhera-chan merchandise have stirred criticism as trivializing self-injury and other “serious” issues behind the act, the idea of wearable/removable self-cuts paradoxically suggests the subversive potential of cute aesthetics. In the cutie menhera trope, the yami-kawaii outfits and accessories can work as a sugar-coating layer to communicate one's inner turmoil and social discomfort in a playful and exaggerated manner. Drawing attention to its superficial materiality, the cutie menhera plays resistance to a “symptomatic” reading, which assumes a text's truest meaning is not immediately apprehensible and must be unveiled by an expert interpreter (Best and Marcus, 2009). Against the medico-political proposition that there must be a “real” issue buried beneath one's self-injury, the wrist-cut bracelet reduces self-injury to the depthless surface, rendering it commodifiable, consumable, and thus controllable body work through the façade of cuteness.

This assertive, in-your-face cuteness of the cutie menhera embodies what Sharon Kinsella (1995) calls a “rebellious, individualistic, freedom-seeking attitude” (p. 229) of Japanese kawaii culture. However, whereas Kinsella (1995) puts an emphasis on the infantile, escapist dimension of kawaii by equating being cute with behaving childlike, Menhera Pink and wrist cut warriors engage in aggressive social commentary through their bloody fight against mental illness (evil spirits). Likewise, the practitioners of yami-kawaii fashion refute the premises of the medical model that casts self-injury as a self-evident sign of pathology. The scars and wounds could be read as a removable accessary, rather than unwanted marks of individual morbidity. Regarding the subversive potential of cute, Brzozowska-Brywczyńska (2007) contends that cute aesthetic embodies the Foucauldian heterotopia—“the place outside the norm, the site of revolutionary potential to change, to post an alternative order, where the coherence between words and reality is no more possible, where the paradox is structuring rule” (p. 225). As a heterotopic being, the cutie menhera may perform the agentic self by pushing back against the pathologization long associated with female self-injury.

Discussion

Over the past few decades, the slang menhera has gained unique versatility to travel across the Japanese popular cultural landscape. Even though the term initially referred to a self-label for a person living with mental ill-health, a multitude of interpretations have emerged over time, transforming menhera into a multivocal discourse. All three narrative tropes examined in this article are entangled with sociocultural constructions of mad womanhood in Japan. Menhera girls in some ways reproduce and reinforce traditional gender norms, while in other ways disrupt the framing of women with mental ill-health as abnormal others. Pejorative connotations associated with self-injury, such as attention-seeking, manipulative, and obsessive, mobilize the normative discourse that demonizes female aggression. Simultaneously, menhera embody traditional femininity such as submissiveness, silence, and selfless devotion, which paradoxically enhances the desirability of menhera girls as an object of affective consumption.

Eventually, menhera has become part of what cultural critic Azuma (2009) metaphorically calls a postmodern “database” of cultural imaginaries. The database offers content creators an attractive caricature, a dramatic tool, and a source of plots with handy narrative tropes to draw from, while providing audiences with a rich repository of affective stimuli to satisfy their drives (Azuma, 2009). Within the database, menhera becomes an archetype of contemporary female madness that can be consumed with little need of backstories and contextual knowledge. A series of personality traits attached to the slang menhera (e.g., preoccupied attachment style, insecurity, excessive jealousy) are essentialized, caricatured, and sexualized, shaping the collective understanding of what menhera girls are and do. Self-injury is framed as an iconic act that confirms menhera girls' abnormality, which in turn triggers a series of pre-packaged responses from contempt, pity, abhorrence, to attraction and fetish.

Once integrated into this ever-expanding database, the menhera tropes play a powerful role in shaping one's experience with self-injury. Just as psychiatric diagnoses provide those facing life problems with “languages of suffering” to narrate their experiences (Brinkmann, 2014), the menhera tropes may mobilize a set of understandings and potential actions distinct from clinical conceptualizations. In her study with female college students in Tokyo, Matsuzaki (2017) found that 13% of survey respondents had used the word menhera in daily conversation to refer to themselves. Matsuzaki posits that mental health slangs like menhera may provide people with a convenient frame of reference to understand and describe subjective experiences of mental ill-health. Here, the label menhera may work metonymically to protect the persons who adapt it, since wearing it enables them to instantly perform a “mentally unhealthy” identity without disclosing actual medical diagnoses (if any) or the reason for their angst. For women who self-injure, it may be at times easier to call themselves menhera to self-pathologize their abject self than to ponder root causes of their mental angst pertinent to the contemporary Japanese society – such as the patriarchal social system, the lack of equality caused by a widening socio-economic gap, and the pressures of economic deprivation (Nae, 2018).

This process can be understood as what Ian Hacking has called “classifications of people” in that a system of classification formulates general truths about people's suffering (Hacking, 2004). Drawing on Hacking's work, Millard (2013) argues that gendered pathology of self-cutting may exert powerful influence over women who self-injure. Millard notes: “as self-harm becomes further entrenched as ‘female cutting,' the more people gendered as female have access to a resonant behavioral pattern said to signify ‘distress”' (p. 136). Similarly, through the menhera tropes, self-injury can be culturally recognized as a mean for women to externalize ikizurasa (pain of living), which simultaneously frames self-injury as a self-sufficient act to classify a woman as menhera. However, Hacking (2004) further argues that the dialectic between classifications and people classified is rather dynamic and cyclical. When people interact with systems of classification, those who classified “cause systems of classification to be modified in turn” (p. 279), a feedback mechanism that he coined “looping effects.”

In the light of this looping effect, the intersection of mental health and female counterculture is worth further exploration. We have argued that the cutie menhera embodies an inherent tension associated with the cute aesthetics between reproducing and subverting the existing social order. Although there is an understandable concern that their sarcastic, tongue-in-cheek attitude toward self-injury and mental illness may trivialize or fetishize the issue, the cutie menhera's impulse to “cute-ify” the socially abject self—as a commodity amenable to change—can potentially disrupt pathological judgment ascribed to them. The cutificaction process may provide the opportunity for people who self-injure to open spaces for vocality and performance apart from the medical model that renders a clinical approach as the only appropriate way to make sense of self-injury. We thus echo Kato (2018) proposition that yami-kawaii (sick-cute) culture may destabilize the long-standing undesirability of sick/detracted female bodies. The practitioners of menhera fashion seem to thrive on dialectical oppositions: cute and ugly, engaged and apathetic, wild and tame, subordination and resistance to chauvinist fantasies. With the ambivalence at the heart of their aesthetics, the cutie menhera cheekily questions: What's wrong with being mentally ill?

Nonetheless, the politically subversive potential of the menhera subculture requires a cautious observation to avoid blind celebration or denigration. The cutie menhera's social commentary is considerably limited to the realm of cisgender and heterosexist normativity. Their aesthetic focuses primarily on an idealized feminine cuteness and deviance from it, while little attention is paid to social class, race, ethnicity, sexuality, dis/ability, and other identity makers that may ascribe different meanings to self-injury and female madness. It would be fruitful for future research to apply an intersectional lens that takes into account material and discursive socio-political contexts that inform theorization of mad womanhood. Moreover, the menhera-the-cutie subculture is deeply entangled with consumerism that equates empowerment with the capacity to purchase. As Mooney (2018) comments on girls' digital subcultures, subversive identity performances by youth sometime end up swallowed by mainstream consumer culture. Given the widening socio-economic gap in Japan, future theoretical work should interrogate who has access to the subversive readings of self-injury and mental health, while others may fall into the prey of poverty and poverty shaming.

Conclusion

Today, menhera girls abound in Japanese popular culture in many forms and manifestations. One may encounter them in manga, anime, games as well as clothing, makeup, and other character merchandise. Within the three narrative tropes examined in this article—the sad girl, the mad woman, and the cutie—self-injury functions as an iconic signifier of women's vulnerability, monstrosity, and desire for control over their bodies. Even though the act is strongly associated with one's mental ill-health, in these narrative tropes it also represents a deviant performance and a tongue-in-cheek statement of agency that troubles the pathological reading of the practice.

Given the ongoing dialectic between popular cultural classification and people classified, developing an intersectional, cross-disciplinary understanding of how popular culture represents self-injury has implications for clinical practice and research. Just like any other human behavior, clinical practices do not exist in a cultural vacuum. When people use cultural slangs like menhera to explain their engagement with self-injury, they may attempt to narrate their pain of living that cannot be captured by a medical frame of reference. Their vernacular illness narrative can then feed back into the clinical system of classification and shape clinical providers' understanding of what self-injury is and does. In this regard, we concur with Chandler (2014) assertion that attending to the diverse ways in which self-injury is understood and narrated “should comprise an important aspect of compassionate clinical practice” (p. 5). Exploring the cultural milieu wherein people explain, perform, and make sense of self-injury can illuminate important conversations occurring outside of the clinical practice that have considerable influence on people who self-injure and those who are affected by it.

Author Contributions

Both authors have made a substantial and intellectual contribution to the work and approved the submitted manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Ryerson University Faculty of Communication and Design under a new faculty start-up fund granted to YS.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^In this article we selectively use “mental ill-health” rather than “mental illness” or “mental disorder” to avoid unnecessary pathologization and infer that anyone could temporarily experience worsening of mental health in their life. Our use of this terminology is informed by our positionality that mirrors that of critical health communication and disability studies. It is also reflective of our experience working with people with lived experiences of self-injury.

2. ^Slice-of-life manga (nichijō-kei in Japanese) refers to a narrative genre that features realistic depictions of everyday, mundane life.

3. ^In 2017, along with the transfer of ownership, all 2-channel past logs were opened to the public for free. According to the 2-channel archives (https://mevius.5ch.net/utu/kako/kako0000.html), the mental health board was launched on November 21, 1999 by Nishimura Hiroyuki, the founder of 2-channel as “sou-utsu ban” (manic-depressive board). As of May 18, 2021, there were 75,987 threads posted under the mental health board with each thread hosting up to 1,000 posts.

4. ^2-channel changed its name to 5-channel in 2017.

5. ^Since 1999, the mental health board has been hosted on 16 different servers. Most of the oldest threads were on a server named “piza” (https://piza.5ch.net/utu/kako/) that hosted a total of 6907 threads between November 1991 to July 2001. We went through the titles of 6907 threads and took a closer look at posts made to the 40 threads that include “risuto kat (wrist cutting)” “risuka (a portmanteau of risuto kat)” or “jisho (self-injury)” in their titles.

6. ^Around the same time, the term menhera also generated art subculture among artists living with mental ill-health. Between 2014-16, a group of artists in Tokyo started applying this label to their work and organizing a yearly art fair called “Menhera Exhibit” to display and sell their “outsider art” (TAV Gallery, 2016).

7. ^The term “sad girl” may remind some readers of the Sad Girls movement that had gone viral across North American social media around 2014-15. Digital artist Audrey Wollen (@tragicqueen), who is credited with coining the term “Sad Girl Theory” in 2014, claimed that the sadness of girls should be re-historicized as an act of resistance (Tunnifliffe, 2015). Wollen's online performance of sadness, chronic illness, and depression can be considered a protest against the liberal feminist ideal of “Girl Power” that emphasizes women's will-power despite patriarchal social structures. By framing women/girls as responsible for their own success, the Girl Power discourse was criticized as denying and pathologizing women's sadness (Mooney, 2018). Although there are certainly commonalities between the (White) Sad Girl movement and the sad girl menhera, the latter is oriented more toward pathologization of female fragility and conformity to cultural norms rather than resistance to and disruption of such norms.

8. ^In this article we present Japanese names in the Japanese convention – the family name (surname) followed by the given name (first name).

9. ^In Japanese subculture, this caricature is sometimes called “yandere,” a portmanteau of “yanderu” (sick) and “deredere” (lovestruck), referring to a deranged girl who uses violence or brutality to express her obsessive love. Kato (2018) argues that yandere embodies borderline personality disorder, while menhera is “in the type of narcissistic personality disorder” (p. 47). Although we disagree with this blunt and pseudo-medical dualism, it is worth noting that yandere girl is an exaggerated caricature of menhera girl with strong emphasis on her brutality.

10. ^In June 2015, the company changed the game title to “Yuru-yami girlfriend and one million messages” where the term yuru-yami (loosely sick) replaced menhera. While Happy Gamer Inc. did not specify the reason for this decision, the game's official twitter alluded that Apple's app store policies might have led to the title change. (https://twitter.com/Sendergirlgame/status/607784210602983425).

References

090 (2016a). ‘Menhera' to iu kotoba no rekishi: 2-channel de ‘menhera' ga tanjo surumade. [Japanese] (An early history of the term ‘menhera' on 2-channel). Available online at: https://menhera.jp/975 (accessed May 21, 2021).

090 (2016b). Utsuri kawaru ‘menhera' no imi: kono 10-nen de ‘menhera' no shiyohou wa donoyouni kawattanoka. [Japanese] (The changing meaning of ‘menhera': how the use of the term ‘menhera' has change over the past 10 years). Available online at: https://menhera.jp/1095 (accessed May 21, 2021).

Alderton, Z. (2018). The Aesthetics of Self-Harm: The Visual Rhetoric of Online Self-Harm Communities. New York, NY: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781315637853

Aviram, R. B., Brodsky, B. S., and Stanley, B. (2006). Borderline personality disorder, stigma, and treatment implications. Harv. Rev. Psychiatry 14, 249–256. doi: 10.1080/10673220600975121

Bareiss, W. (2017). Adolescent daughters and ritual abjection: narrative analysis of self-injury in four US films. J. Med. Human. 38, 319–337. doi: 10.1007/s10912-015-9353-5

Best, S., and Marcus, S. (2009). Surface reading: An introduction. Representations 108, 1–21. doi: 10.1525/rep.2009.108.1.1

Brickman, B. J. (2004). ‘Delicate' cutters: Gendered self-mutilation and attractive flesh in medical discourse. Body Soc. 10, 87–111. doi: 10.1177/1357034X04047857

Brinkmann, S. (2014). Languages of suffering. Theory Psychol. 24, 630–648. doi: 10.1177/0959354314531523

Brzozowska-Brywczyńska, M. (2007). “Monstrous/cute. Notes on the ambivalent nature of cuteness,” in Monsters and the Monstrous: Myths and Metaphors of Enduring Evil, ed N. Scott (Brill Rodopi). doi: 10.1163/9789401204811_015

Canetto, S. S., and Sakinofsky, I. (1998). The gender paradox in suicide. Suicide Life-Threat. Behav. 28, 1–23.

Chandler, A. (2014). Narrating the self-injured body. Med. Humanit. 40, 111–116. doi: 10.1136/medhum-2013-010488

Chandler, A., and Simopoulou, Z. (2021). The violence of the cut: gendering self-harm. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18:4650. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18094650

Chouinard, V. (2009). Placing the ‘mad woman': troubling cultural representations of being a woman with mental illness in Girl Interrupted. Soc. Cult. Geography 10, 791–804. doi: 10.1080/14649360903205108

Conpeitou (2015a). [Tweet]. Twitter. Menhera chan corabo: Riska banguru nyushu shimashita. [Japanese] (Collaboration with Menhera-chan: Wrist cut bracelet now on sale). Available online at: https://twitter.com/_conpeitou_/status/613563672187682816 (accessed June 13, 2021).

Conpeitou (2015b). Risuka banguru hatsubai chushi no oshirase. Ameba Blog. Available online at: https://ameblo.jp/0-conpeitou-0/entry-12043269584.html (accessed June 28, 2021).

Da Vinci News (2013). Gen-eki joshi kousei ga kaita manga ‘Menhera-chan': Kotoha Toko interview. Available online at: https://ddnavi.com/serial/99169/a/ (accessed June 12, 2021).

Danylevich, T. (2016). De-privatizing self-harm: remembering the social self in how to forget. J. Bioeth. Inq. 13, 507–514. doi: 10.1007/s11673-016-9739-8

Grant, B. F., Chou, S. P., Goldstein, R. B., Huang, B., Stinson, F. S., Saha, T. D., et al. (2008). Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV borderline personality disorder: results from the Wave 2 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J. Clin. Psychiatry 69, 533–545. doi: 10.4088/JCP.v69n0404

Hacking, I. (2004). Between michel foucault and erving goffman: between discourse in the abstract and face-to-face interaction. Econ. Soc. 33, 277–302. doi: 10.1080/0308514042000225671

Hansen, G. M. (2011). Eating disorders and self-harm in Japanese culture and cultural expressions. Contemp. Japan 23, 49–69. doi: 10.1515/cj.2011.004

Happy Gamer Inc. (2015). Menhera Kanojo Kyuzou chu. Available online at: https://happygamer.co.jp/post/113224874165 (accessed June 12, 2021).

Kato, G. (2018). A New Meaning of Mental Health in Japanese Net World. Bull. Fac. Sociol. 12, 43–55.

Kido, R. (2016). The angst of youth in post-industrial Japan: A narrative self-help approach. New Voices Japan. Stud. 8, 98–117. doi: 10.21159/nvjs.08.05

Kinsella, S. (1995). “Cuties in Japan,” in Women, Media and Consumption in Japan, eds L. Skov and B. Moeran (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press).

Matsuzaki, M. (2017). Definition of “Mental Health Slang” from the study among young women in Tsuda College. Bull. Tsuda College 49, 197–216.

Millard, C. (2013). Making the cut: the production of ‘self-harm' in post-1945 Anglo-Saxon psychiatry. Hist. Human Sci. 26, 126–150. doi: 10.1177/0952695112473619

Miskec, J., and McGee, C. (2007). My scars tell a story: Self-mutilation in young adult literature. Child. Literat. Assoc. Q. 32, 163–178. doi: 10.1353/chq.2007.0031

Mooney, H. (2018). Sad girls and carefree Black girls: Affect, race, (dis)possession, and protest. Women Stud. Q. 46, 175–194. doi: 10.1353/wsq.2018.0038

Radovic, S., and Hasking, P. (2013). The relationship between portrayals of nonsuicidal self-injury, attitudes, knowledge, and behavior. Crisis 34:324. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910/a000199

Refinery29 (2018). Style Out There: The Dark Side of Harajuku Style You Haven't Seen Yet. Available online at: https://www.refinery29.com/en-ca/yami-kawaii-fashion-harajuku-style-dark (accessed June 27, 2019).

Seko, Y. (2013). Picturesque wounds: a multimodal analysis of self-injury photographs on flickr. Forum 14:2. doi: 10.17169/fqs-14.2.1935

Seko, Y., and Kikuchi, M. (2020). Self-injury in Japanese manga: a content analysis. J. Med. Human. 2020, 1−15. doi: 10.1007/s10912-019-09602-9

Seko, Y., and Lewis, S. P. (2016). The self—harmed, visualized, and reblogged: Remaking of self-injury narratives on Tumblr. New Media Soc. 20, 180–198. doi: 10.1177/1461444816660783

Suisui (2020). Subete no joshi wa menhera de aru. [Japanese] (All Girls are Menhera) [Japanese]. Tokyo: Asuka Shin-sha.

TAV Gallery (2016). Menhera Ten: Dream (Menhera Exhibition: Dream). Available online at: https://tavgallery.com/dream/ (accessed May 17, 2021).

Terada, H., and Watanabe, M. (2021). A study on the history and use of the word “Menhera.” [Japanese] Hokkaido University Bull. Counsel. Room Dev. Clin. Needs 4, 1–16. doi: 10.14943/RSHSK.4.1

Trewavas, C., Hasking, P., and McAllister, M. (2010). Representations of non-suicidal self-injury in motion pictures. Arch. Suicide Res. 14, 89–103. doi: 10.1080/13811110903479110

Tunnifliffe, A. (2015). Artist Audrey Wollen on the Power of Sadness: Sad Girl Theory Explained. Nylon. Available online at: https://www.nylon.com/articles/audrey-wollen-sad-girl-theory (accessed June 17, 2021).

Keywords: menhera, self-injury, Japanese popular culture, female madness, representations

Citation: Seko Y and Kikuchi M (2022) Mentally Ill and Cute as Hell: Menhera Girls and Portrayals of Self-Injury in Japanese Popular Culture. Front. Commun. 7:737761. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2022.737761

Received: 07 July 2021; Accepted: 10 February 2022;

Published: 11 March 2022.

Edited by:

Victoria Team, Monash University, AustraliaReviewed by:

Peter Steggals, Newcastle University, United KingdomMike Alvarez, University of New Hampshire, United States

Copyright © 2022 Seko and Kikuchi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yukari Seko, eXNla29AcnllcnNvbi5jYQ==

Yukari Seko

Yukari Seko Minako Kikuchi2

Minako Kikuchi2