- Division of Arts and Letters, Governors State University, University Park, IL, United States

This article contributes to the scholarly discussions about the role of religion in social and political action rhetoric by revealing the complexities of rhetorical resources found in the logic of theology. To this end, I explored rhetorical functions of theology in Bishop Michael Burbidge's 2013 Statement on Comprehensive Immigration Reform. Close textual analysis of the text allows scholars to identify what I call the textual theology—a mediating level of theology between theological traditions and the rhetoric in a text. Analysis of the textual theology in the Bishop's statement provides insights as to how the more abstract levels of theology animate texts in the real world in ways that have implications that reach beyond the particular text.

Immigration policy was one of the most pressing political issues facing the Catholic Diocese of Raleigh, North Carolina in 2013. As many as half the Catholics in this vibrant diocese, approximately 250,000 people, were undocumented residents (The diocese, n.d., para. 2). With such a large percentage of membership experiencing the implications of the national immigration system, Church leadership was keenly aware of the shortcomings of the government's immigration policies. The diocese's concern about immigration policy was highlighted by its inclusion as one of the six areas of focus on the Catholic Voice NC website (Issues, n.d.). In addition to the impact of immigration policy on the diocese and the positioning of immigration as an area of key social concern for Catholics in North Carolina, Bishop Burbidge of the Diocese of Raleigh was a member of the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, a body of Church leadership that had issued numerous calls for comprehensive immigration reform in the United States (Catholic Church's position on immigration reform., 2013. USCCB Position).

In June 2013, the United States Senate passed Senate Bill 744, the Border Security, Economic Opportunity, and Immigration Modernization Act (S.744 - Border Security, 2013). While issues of immigration were largely debated along political party lines, this bill was formulated by the bipartisan gang of eight and garnered just enough bipartisan support to pass the Senate (Roeper, 2013). Having passed the Senate, the bill only needed to be approved by the Republican-controlled House of Representatives to enact comprehensive immigration reform. While the bill enjoyed modest bipartisan support in the Senate, Republicans in the House of Representatives refused to bring Senate Bill 744 to the floor for a vote (Gibson, 2013). The only hope for comprehensive immigration reform to become a reality in the United States in 2013 was for a number of Republican Representatives to break party lines and reverse their opposition of Senate Bill 744.

While leaders of religious communities do not hold special government positions nor receive special votes in the United States government, Bishop Burbidge did have an opportunity to help meet the immigration needs of their undocumented parishioners by influencing the Congressional Representatives of the diocese to support Senate Bill 744. The Diocese of Raleigh encompassed eight congressional districts. Two Congressional Representatives in those districts were Democrats and six representatives were Republicans. Three of the six Republican Representatives had recently come to office as a part of the conservative Tea Party Republican surge in North Carolina (Members of Congress, n.d.). This conservative wing of the Republican party was staunchly opposed to comprehensive immigration reform. If Senate Bill 744 was going to be passed, or even be brought to the floor of the House of Representatives, at least some of the Republicans representing the Congressional districts in the Diocese of Raleigh would need to reverse or soften their opposition to the bill. As the leader of a religious community of half a million persons, and a religious tradition that designates considerable authority on him as a leader, Bishop Burbidge had the ability to mobilize the members of the diocese to contact their Congressional Representatives and advocate for the passing of the comprehensive immigration reform bill.

This case study brings to mind the ongoing conversations about the place of religion in public and political discourse. While these discussions often focus on the appropriate roles and boundaries of religion in public discourse, I will not make the claims of what I believe the boundaries should be in an abstract argument. Rather, by looking at the rhetoric of a prominent and politically active clergy, I will see how rhetors negotiate those boundaries in practice. I begin with the understanding that the presence and influence of religion and, as I will go on to argue more specifically, theology in American public discourse is virtually undeniable (Lovin, 2012, p.88; Mathewes, 2012, p.113). This study, then, attempts to better understand how theology uses and is used by clergy in contemporary public and political discourse.

Berger's (1979) famous secularization thesis, the belief that modern societies would inevitably be secular societies as religion faded away in the face of modernity, has been largely dismissed even by Berger (1999) himself (Cavanaugh et al., 2012, loc. 111; Grasso, 2012, loc. 115). Today, scholars generally acknowledge that religion continues to be vital in the modern world, in both our private and public lives (Habermas, 2011, loc. 271; Mendieta and Vanantwerpen, 2011, loc. 36 & 45; Cavanaugh et al., 2012, loc. 104; Grasso, 2012, loc. 112; Edwards, 2015, loc. 243 & 491). Instead of fading away or being relegated to a private realm, modern religion, according to Casanova (2003), “has, assumes, or tries to assume a public character, function, or role” (p. 111). While in recent decades some scholars believed that religion would, or perhaps should, fade out of American public life, a growing number of scholars are recognizing that religion has never left American public discourse.

Rhetorical scholars, regardless of their personal views on religion, should continue to grow in understanding the roles of religion and theology in public discourse because religion continues to be a significant part of contemporary public and political discourse. As the secularization thesis is no longer a prominent lens to view religion in public life, some prominent scholars have called for further study on religion in public discourse (Troup, 2009; Habermas, 2010, pp. 37, 46, & 49; DePalma and Ringer, 2015). For instance, Pernot (2006) justified his study on the intersection of rhetoric and religion in ancient Greece by noting that scholars increasingly acknowledge that religion continues to be present in the modern world. He urged the academic community to follow his lead and take the presence of religion in public life seriously because religion was growing in influence on public discourse, “This is why it is important— and perhaps why it is the duty of us academics and intellectuals—to find new ways of thinking about religion” (p. 236). In similar fashion, Calhoun (2011), reflecting upon a panel of scholars discussing the power of religion in public discourse, called for further scholarly consideration of the powerful influence of religion in contemporary public discourse. Calhoun argued that while some scholars had predicted that religion would fade away, it has in fact remained a powerful force in American public discourse. Pernot (2006) and Calhoun (2011) justified their work on religion in public discourse by claiming there is a need for rhetorical scholarship on public discourse that employs religion because the secularization theory has proven false and religion has maintained a prominent role in public discourse. Furthermore, they urged other rhetorical scholars to contribute to this line of study.

This article contributes to scholarly discussions about the role of religion in public discourse and political action rhetoric by highlighting the rhetorical functions of theological logics. The functional definition of theology I use in this study is discourse about God and God's interactions with the world that acts as interpretative systems. This definition reflects my study's focus on theology in action in life rather than formalized theology. Recognizing the breadth of this definition of theology, I will also identify three levels of theology that enhance the definition and will be noted in the study. First, there are theological traditions that have emerged as human discourse about God and God's interactions in the world have found commonalities and built off of one another. These theological traditions will predate and may or may not influence the role of theology in the invention of a rhetorical text. Second, on the most specific level, individual rhetors describe God and God's interactions in the world in particular texts. The text may or may not be influenced by theological traditions. It will likely be influenced by the situation or need that has encouraged the rhetor to speak at that moment. The text can be analyzed using a variety of rhetorical methods, some of which may identify theology in the text. Third, and of primary concern in this study, is a mediating level of theology between theological traditions and the rhetoric in a text. I will refer to this as textual theology.

Textual theology is observable in but not limited to a specific text. It can be transferred to other texts as the interpretive lens or perspective for communicating and making sense of the world, including the situations encouraging the rhetorical invention of the texts. While textual theology is not the same as a specific text, there are traces of the textual theology present in the text. In this study, I will use rhetorical methods to pull patterns of textual theology out of a text in order to understand how the more abstract theology animates texts in the real world in ways that have implications that reach beyond the particular text because they tell us about a way of looking at the world and coaching people's actions and attitudes. Textual theologies mediate abstract beliefs about how God operates in the world and historical theological traditions for immediate, real-world situations. Identifying textual theology also strengthens the rhetorical scholar's ability to predict a rhetor's future rhetoric.

In this article, I identify and analyze the role of textual theology in Bishop Burbidge's Statement on Comprehensive Immigration Reform. First, I will identify the explicit rhetorical strategies in Bishop Burbidge's Statement on Comprehensive Immigration Reform. Next, I will use rhetorical methods to pull patterns of textual theology out of the social action text. Then, I will highlight ways the textual theologies in the Bishop's statement mediate abstract beliefs about how God operates in the world and historical theological traditions for immediate, real-world situations. Finally, I utilize the textual and logical analysis to predict the future impact of the Bishop's social action rhetoric and social action rhetorics with similar logics.

The Bishop Calls For Prayer and Advocacy

On Sunday, September 8, 2013, Bishop Burbidge celebrated a Mass of Thanksgiving at Saint Mary Basilica Shrine in Wilmington, North Carolina, in recognition that Pope Francis had designated the church as a basilica of prayer for all people. At the conclusion of the mass celebrating this significant event, Bishop Burbidge claimed that prayer should lead Catholics to advocacy. He then called on the congregation, and the entire Diocese through video, to contact their federal legislators and urge their support of the comprehensive immigration reform bill in the United States Congress. Video of the Bishop's statement on comprehensive immigration reform was posted on the Diocese of Raleigh's YouTube page and the text of the statement was posted on the Diocese of Raleigh's official website.

Bishop Burbidge's “Statement on Comprehensive Immigration Reform” called Catholics in the Diocese of Raleigh to join him in support of Senate Bill 744. Burbidge argued that there was a moral imperative to pass the bill, because the nation's current immigration policies failed to recognize the dignity of immigrants as human and often violated the integrity of the family. Burbidge noted that he and the other American Bishops had publicly given their support to the legislation. The Bishop spent considerable time making the case that the teachings of the Catholic Church call for immediate action to improve the nation's immigration policy. He cited Church teachings on the value of immigrants and families and the responsibility of nations to treat immigrants with openness and fairness even as those nations protect their boundaries. Bishop Burbidge claimed that Senate Bill 744 met the Catholic Church's moral standards for national immigration policy three different ways. First, it provided a pathway for immigrants to come to the United States legally. Second, it recognized the nation's right to regulate and protect its borders. Third, it allowed immigrants to meet their financial needs through labor rights. Finally, the Bishop called Catholics to support Senate Bill 744 in two different ways: praying for immigration reform and asking their congressional representatives to support the bill.

In addition to the overall argument that Burbidge made for the support of the 2013 comprehensive immigration reform bill, the Bishop's speech also directed the argument through his definitions of certain key terms and of the general situation. First, the Bishop transitioned from the Mass of Thanksgiving for the Pope's naming of the Basilica Shrine for Prayer to his statement on comprehensive immigration reform with a definition of prayer. Burbidge invited the audience to join him, “where our prayers necessary leads us—to advocacy.” This definition of prayer as something inherently connected to advocacy prompted the audience, who had just celebrated and participated in prayer for all people, to also participate in his call to advocacy on behalf of immigrants. Second, before naming the issue of comprehensive immigration reform, Burbidge defined it as an “important moral issue.” This definition set high stakes for the issue. It also placed the political issue in the realm of morality, a realm on which Catholics are taught to look to the Church for direction, rather than the realm of partisan politics. Third, the Bishop defined the issue by noting that the Catholic Church embraces people of all nations. This definition both called on the audience's identity as Catholic and positioned the immigration debate in the context of their Catholic practice of welcoming persons of other nationalities, including immigrants. Burbidge further defined the need for immigration reform by contrasting the Church's practice of welcoming all people against the United States' current immigration system, which he further defined as “broken.” Finally, Burbidge defined any delay of immigration reform as “immoral.” This definition of inaction or deferral to act for what is moral as a violation of morality increased the urgency of the Bishop's call to action.

Having looked at the explicit arguments and strategic definitions employed by Bishop Burbidge in his call for Catholic advocacy for immigration legislation, this article will proceed to explore deeper levels of logic, particularly the theological logic, at work in this call to action. However, we must first look to the methodologies of rhetorical analysis that will allow us to uncover the logics at work below the surface of the text.

Internal Logical Frames and Close Textual Analysis

Burke's (1974) conception of terministic screens provides insights into the nature and functions of logical frameworks in texts. A terministic screen is an internally coherent perspective through which a human interprets the world. Terministic screens are visible as they work in texts through systematic vocabularies with internal logics. Whether or not the symbol user is aware of its existence, all humans communicate through terministic screens and those terministic screens are manifested, therefore observable, in symbolic communication. A terministic screen is not deterministic of what a rhetor will say, in fact it may not necessarily predate the text, but it does act as a constraint that influences a rhetor's rhetorical choices with its coherent logic. This theory impacts how I view the Bishop's political action text in this study by claiming there is a coherent system of symbols within the text, a system that has placed constraints on the development of the text and can be identified through the text. This logical system symbols includes theological logics.

Rather than simply categorizing a text containing theological logics as religious, identifying and understanding terministic screens provides the rhetorical scholar an understanding of the logic at work in the text. Burke (1974) claimed, “the injunction, ‘believe that you may understand' has a fundamental application to the purely secular problem of ‘terministic screens”' (p. 47). When one has identified the particular terministic screen that is guiding the observations and understands the logical pattern that holds the screen together, the observations will then be clear and understandable as they fit the pattern of the screen. In other words, understanding terministic screens will help the rhetorical scholar understand the texts emerging from the terministic screens. The process can, and perhaps must, also be reversed; the rhetorical scholar can identify and understand a particular terministic screen by understanding a rhetor's texts. Furthermore, once identified, a particular terministic screen can allow a critic to foreshadow what and how that screen's adherents may think and speak about various undeclared issues (Olson, 2002). This rhetorical theory directly connects with rhetorical methods. A text itself provides evidence of the terministic screen that a rhetor is operating from as the words of the text can reveal an internally consistent logical frame. A cluster-agon analysis of the text will help the rhetorical scholar identify those themes.

I used Burke's cluster-agon analysis and narrative arc analysis in my study in order to identify the terministic screen revealed in Burbidge's September 8, 2013 speech. Burke (1968) claimed that the dramatistic method was “the most direct to the study of human relations and human motives is via a methodical inquiry into cycles or clusters of terms and their functions” (p. 445). The interrelationships between the associated clusters in the text itself are the rhetor's motives in which he or she communicates the text (Burke, 1974, p. 20). This approach brings with it a dramatistic understanding of texts, but it answers the questions directly from a close, careful, and rigorous analysis of the text (Burke, 1974, p. 69). This approach grounds the analysis in the rhetor's text rather than the rhetorical scholar's bias regarding the rhetor, their social cause, or their ideological commitments.

In my close reading, I identified the dramatic alignment and interrelationships as directly revealed in the text. I answered two basic questions: “what goes with what?” and “what is opposed to what?” (Burke, 1974, p. 69). The first question was answered by identifying what symbols were linked together in a text. At times this clustering of terms was literally that terms were placed next to one another or were repeatedly mentioned together (Brummett, 2011, p. 107). Symbols of a text could also be recognized as going together by sharing a common value, characteristic, or setting. Another way terms could be clustered together was that they were on the same side of a struggle described in the text. This leads me to identify ways terms in a text may be opposed to one another. Symbols in a text may be placed in opposing clusters of terms if the text presents the symbols in conflict with one another or simply as a contradiction to one another (Brummett, 2011, p. 110).

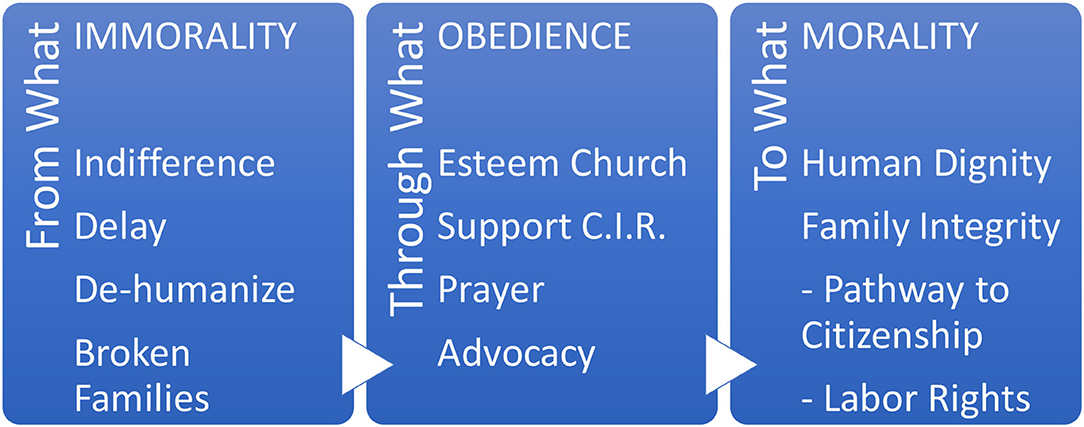

The next step of the locating the implicit strategies of the text is to identify the dramatic development that takes place in the text. This dramatic development may or may not be clear in the explicit tactics or structure of the text. The dramatic development and transformations of the interrelationships in the text can be uncovered by identifying the beginning, middle, and end of the drama in the text. These points are often not the same as the literal beginning, middle, and ending of the text, rather they are the beginning, middle, and end of underlying dramatistic struggle subtly implied in the text. The dramatic development can be found by answering the questions, “from what?” “through what?” and “to what?” in careful study of the text (Burke, 1974, p. 71). In a political action texts, the “from what” or beginning of the drama will likely be presented as the current situation or aspects of the current situation that need to change. The dramatic development's middle, the “through what,” will likely include the actions required of the audience to leave the current situation in order to move toward a preferred future. The “through what” of the implied drama in the political action text will also likely include the challenges and transformations that will take place in that journey toward the preferred future. The drama's ending or “to what” will include the descriptions of the preferred situation that the requested political action is intended to lead toward. The ending is generally preferable to the beginning, justifying the costs of the requested actions.

The Internal Logic of the Call to Prayer and Advocacy

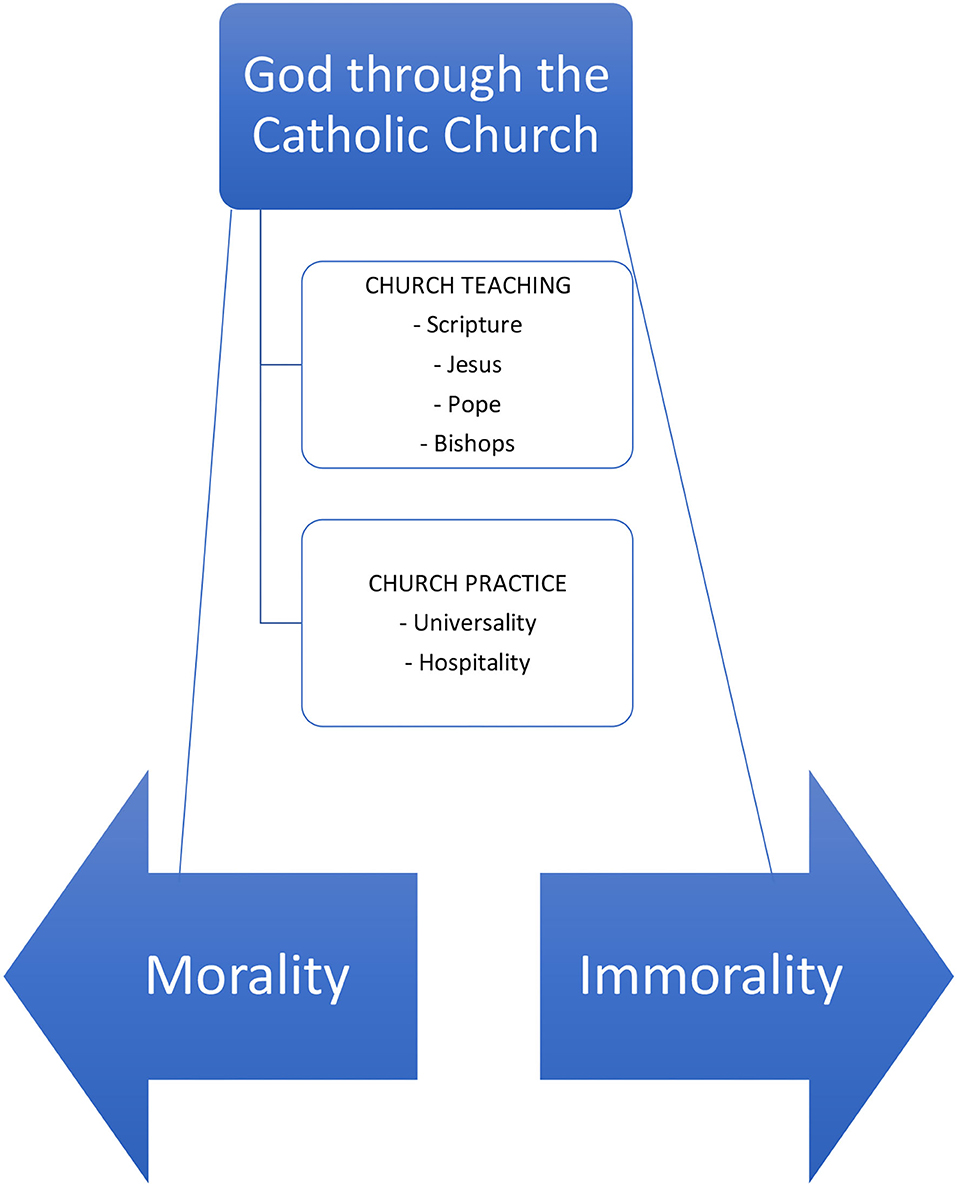

With the explicit tactics in Burbidge's (2013) “Statement on Comprehensive Immigration Reform” identified, and having explained my theoretical and methodological foundations, the next phase of analysis is to conduct a cluster-agon analysis and a narrative arc analysis on the Bishop's speech in order to uncover the terministic screen and ambiguities in the text. First, I will identify the central conflict at work in the speech's logic (Figure 1). In this speech I have identified the conflict between morality and immorality. Next, I will describe clusters of terms on the two sides of the central conflict (Figures 2, 3). This analysis will include identification of the terms and relationships between terms within and between the two clusters. Then, I will identify the text's underlying narrative of how the central conflict proceeds toward the desired ending of a faithful Church and a moral national immigration system and how the audience may participate in such a narrative (Figure 4). Finally, as my study reveals the text's unique terministic screen, I will take special notice of theology at work in the logical framework of the speech.

A Clear Moral Choice

Grounding Authority

Bishop Burbidge's statement on comprehensive immigration reform displays a complex system of authority and an extensive reliance upon the sources of authority in the logical framework and motivation of the audience. The ultimate source of authority in Bishop Burbidge's terministic screen is God through the Catholic Church (Figure 1). With twenty-seven references to the authoritative sources of the Catholic Church in the five-and-a-half-minute speech, their presence was central to the Bishop's, himself, of course, a figure of authority in the Church, rhetoric and logical framework. I have identified Church practice and Church teaching as two kinds of authoritative sources of God through the Catholic Church in the Bishop's terministic screen. The authority of Catholic teaching and the authority of Catholic practice are consistent and united in the terministic screen and only differentiated in my analysis to display the scope of the authority of God through the Catholic Church.

The Choice Between Morality and Immorality

The divine authority in the Catholic Church provides an authoritative judgment of morality and immorality (Figure 1). That judgment reveals and generates the driving conflict in the speech's terministic screen, the agon between morality and immorality. Unlike the terministic screens uncovered in some clergy political action speeches (Vining, 2020), the terministic screen in Bishop Burbidge's speech does not include a fierce and urgent battle against a ruthless enemy as an immediate expression of a cosmic battle. Instead, the agon in the Bishop's terministic screen places morality against immorality as the conflict driving the Catholic audience's choice to support the reform of a broken immigration system that currently violates the Catholic Church's moral teaching and practices. While the agon in the Bishop's terministic screen does not invite the same intensity as a battle against an evil enemy, it does carry high stakes within the speech's logical framework. The terministic screen heavily emphasizes the God-given authority of the Catholic Church. The Church's judgment of morality, then, carries a divine authority for those aligned with the speech's logic, and violation of the Church's moral judgment is a violation of God's moral judgment. The Bishop's placement of his call to support comprehensive immigration reform expands the stakes of the response to the realm of divine moral judgment.

Finally, the morality cluster is significantly larger than the immorality cluster, comprising the overwhelming majority of the speech. This is another significant difference between the Bishop's terministic screen and the other terministic screens of other political action speeches where the speeches gave approximately equal time to the positive and negative clusters (Berthold, 1976; Lynch, 2006; Vining, 2020). The Bishop's emphasis upon the positive cluster contributes to the motivation of the Catholic audience to make the moral choice through a celebration and explanation of morality according to the commonly accepted God-given authority of the Catholic Church.

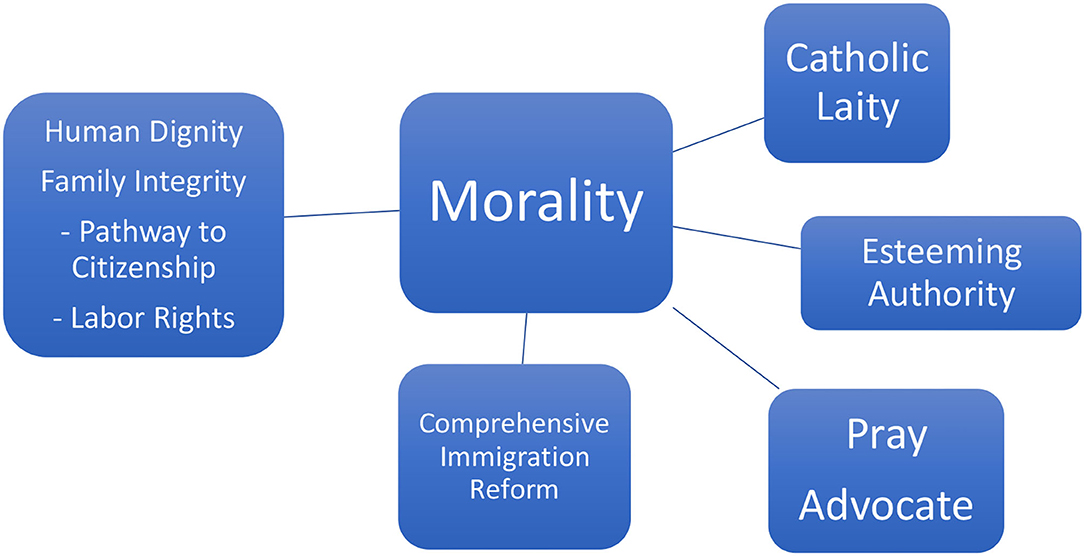

The Morality Cluster

The positive cluster dominates the tone and logic of Bishop Burbidge's statement on comprehensive immigration reform. The speech was almost entirely about the ideas and practices the Bishop favored, even as he called for support of significant changes to an immoral system. Morality is the key term at the center of the positive cluster of Burbidge's terministic screen (Figure 2). As discussed in the agon section above, the designation of morality is grounded in the God-given authority of the Catholic Church. Morality is the driving motivation for the agent's action in the positive cluster of the speech's terministic screen. The logic of this motivation can be further explored by examining the various satellites of supporting terms and their relationship with the key term and the other supporting terms.

The first satellite of supporting terms in my analysis of the morality cluster is the Catholic laity. The second supporting satellite in the Bishop's positive cluster is the attitude that the Catholic laity carry in the morality cluster. I have identified this positive attitude as esteem for authority. The third satellite of terms connected to the key term morality contains the agencies that the Catholic laity use to accomplish the positive cluster's primary action. The two means by which Catholic laity can support comprehensive immigration reform are prayer and advocacy. The primary act of the positive cluster is found in the fourth satellite. The act of supporting comprehensive immigration reform is the primary act for agents to take in the morality cluster of the speech's terministic screen. The fifth satellite of terms in the morality cluster consists of the ends of comprehensive immigration reform—human dignity and the integrity of the family. The ends of comprehensive immigration reform are connected to the cluster's key term morality as they have been judged moral by the authority of the Catholic Church, and thus are motivational for an audience aligned with the logic of the speech's terministic screen.

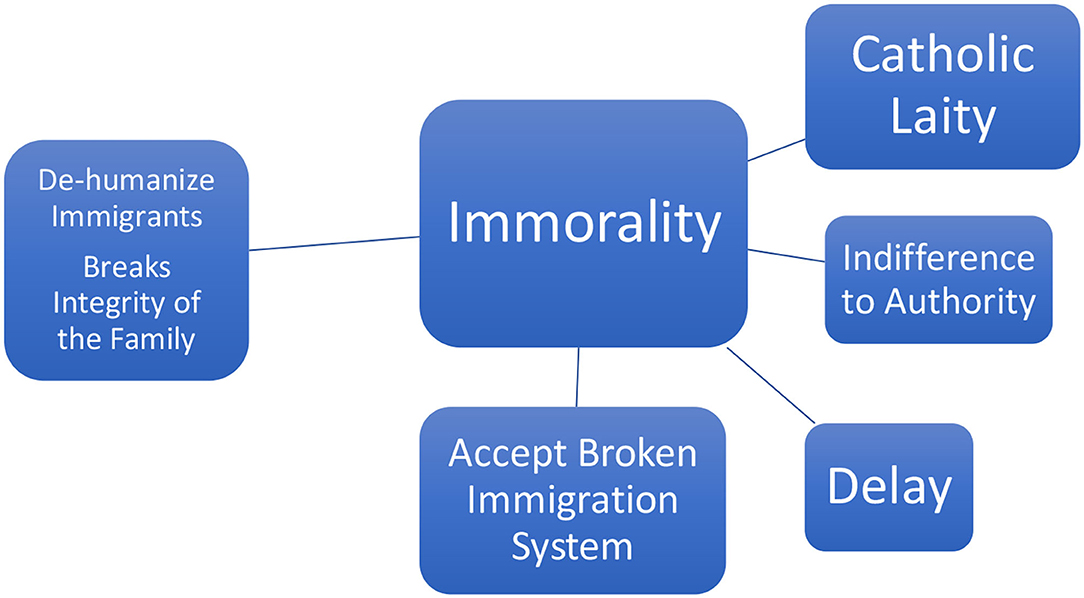

The Immorality Cluster

The negative cluster (Figure 3) of Bishop Burbidge's September 8, 2013 statement on comprehensive immigration reform is considerably smaller than the positive cluster in terms of the amount of content and emphasis it was given during the speech. However, the cluster has a parallel structure and opposing terminology to the positive cluster, reflecting a sharp division between the two clusters in the speech's terministic screen. The division between clusters is rooted in the opposition of the key terms: the key term in the negative cluster is immorality which acts in direct opposition to the positive cluster's key term of morality. As discussed in the agon section, the designation of immorality is grounded in the God-given authority of the Catholic Church. The following description of the satellites of supporting terms and their relationship with other terms in both the morality and immorality clusters provides the logic of the negative cluster within the speech's terministic screen.

The primary agent in the Bishop's negative cluster, located in the cluster's first satellite of terms, is the Catholic laity that he directly addressed in the speech. This means that the morality cluster and the immorality cluster have the same agent. The second satellite of the negative cluster contains the attitude of the Catholic laity in the immorality cluster and possible key to the difference between the agents in the two clusters. The Catholic laity in the immorality cluster carry an attitude of indifference to the authority of the Catholic Church. The third satellite in the immorality cluster is the agency that the Catholic laity uses to accomplish the central act in the negative cluster. The agency in the immorality cluster is delay. The central act in the immorality cluster in the terministic screen of Bishop Burbidge's statement on comprehensive immigration reform is the acceptance of the broken immigration system. The final satellite identified in my analysis of the negative cluster consists of certain ends of the broken immigration system—de-humanizing immigrants and breaking families. The ends of the broken immigration system are judged as an expression of immorality by the terministic screen's grounding authority in the Catholic Church, expressing a sharp contrast with the ends of comprehensive immigration reform in the morality cluster in the Bishop's terministic screen.

From Immorality to Morality

My quest to uncover the terministic screen in the Bishop's political action text includes both a cluster-agon analysis and a narrative arc analysis. While the guiding narrative development is not explicit in Bishop Burbidge's speech, it is present in the text and a central piece of the terministic screen. My analysis revealed a three-part narrative in which the audience was invited to participate (Figure 4). The first stage of the narrative in Bishop Burbidge's terministic screen is composed of the various terms that the Bishop is calling the audience to move from. The key term defining this stage is immorality. The second phase of the narrative in the logical framework in the Bishop's statement on comprehensive immigration reform contains the elements of the story that the audience must go through to move from the immorality phase. I have defined this phase with the key term obedience. Morality is the key term for the conclusion of the narrative that the speech invites the audience to desire and work toward. The positive moral judgment of the Catholic Church grounded in the Church's God-given authority carries motivation in the speech's logical framework.

My narrative arc analysis of Bishop Burbidge's (2013) statement of support for comprehensive immigration reform reveals a three-part story within the speech that calls the audience of Catholic laity to move from immorality to morality through obedience to the Church. The story begins with the immorality of the Catholic laity's indifference to Church authority manifested in their delay in supporting comprehensive immigration reform and resulting in the immoral ends of the broken immigration system. Then the story turns as the Catholic laity obey the Church, including himself as their Bishop, in esteem to Church authority and support comprehensive immigration reform through prayer and advocacy. Finally, in the conclusion of the terministic screen's underlying narrative, the moral obedience of the Catholic laity leads to an immigration system that more fully reflects the teachings and practices of the Catholic Church by treating immigrants with dignity and respecting the integrity of immigrant families.

The Theological Logic of Prayer and Advocacy

Having uncovered the terministic screen in Bishop Burbidge's (2013) statement on comprehensive immigration reform, I will now highlight some of the theological inspirations in the terministic screen in order to analyze how specific theology interacts with other elements of the text's logical framework. Again, my purpose in this study is to evaluate these theological elements not on any particular theological tradition or critique of a theological tradition but on how they seem to function within the text's internal logical framework as delivered. The Bishop's terministic screen presents a conflict between morality and immorality. Theology plays a significant role in defining the central conflict, and theology can be found at work in the various satellites of terms supporting both sides of the conflict between morality and immorality. Morality, as defined in the speech's terministic screen, has Divine origin and goodness and is judged through the God-given authority of the Catholic Church. While the purpose of the Bishop's speech is to mobilize Catholic laity to act in support of comprehensive immigration reform, the speech's terministic screen reveals that the difference between morality and immorality hinges on the audience's response to the Church. This primacy of the Catholic Church in the terministic screen emphasizes the importance of theology, and a specific theology, at work in the rhetoric's logical framework.

While the Bishop certainly came to the speech with theological commitments influenced in part by his theological tradition, the focus of my study is on the theology expressed in the text of this particular speech, so I only reference the Bishop's theological tradition when it is mentioned in the text and when most relevant for the study. This study considers theology to be part of a dynamic relationship with logic and rhetoric in a clergy member's political action text. In this dynamic relationship, theology, rhetoric, and logic inform, constrain, and animate one another. In the following analysis of the terministic screen's theological statements, I will frequently mention only one or two elements of the theology—logic—rhetoric dynamic; in such cases the dynamic of the relationship should be implicitly understood. I do not explicitly name all three elements on every occasion as it would become burdensome for the reader and because mentioning one or two elements can at times provide more direct entry points into analysis and at other times more precise observations. The naming of specific elements should be understood in the context of the ongoing dynamic relationship of theology, logic, and rhetoric in the text.

I will now highlight six different theological emphases in Bishop Burbidge's terministic screen as identified through my cluster-agon analysis and narrative arc analysis of the Bishop's statement on comprehensive immigration reform. First, God speaks and acts authoritatively through the Catholic Church. Second, following the God-given authority of the Catholic Church leads to morality. Third, God calls the Church to engage in the sacred and the secular. Fourth, God's moral authority applies to both the Church and the state. Fifth, God and humans act in the world. Finally, God has given dignity to all humans and family units. I propose that these six theological emphases are active and significant elements of Burbidge's terministic screen. They have influence and are influenced by the logic and other rhetorics in the text. Furthermore, these particular theological emphases interact in the text in ways that other theological statements would not interact in the text.

God Speaks and Acts Authoritatively Through the Catholic Church

The first theology I will identify in Bishop Burbidge's terministic screen exhibits significant influence on the speech's logic. The Bishop's speech includes a theology that God speaks and acts through the Catholic Church with authority. This authority was addressed at length in this article's agon analysis. The teaching, leadership, and practices of the Catholic Church operate with a high level of authority in the Bishop's terministic screen, grounding judgments of what is moral and immoral and adding motivation of the importance of audience action. In the speech's logical framework, the Church acts and speaks on behalf of God in unique and authoritative ways. The uniqueness of the Church can be seen in the designation of various elements, including, for example, the Holy Father and the Sacred Scriptures, as special and uncommon. The authority of the Church can be seen in the text's call for the application of Church teachings on government policies. For example, the Church teaches that humans have dignity and the Church calls for Catholic laity to advocate for government policies that treat humans with dignity. As the Church has authority in the world, the terministic screen reveals that there are sources of authority within the Church. As these authorities, including the Pope, Scripture, and Bishops, speak to the Church, they also speak to the world.

This theology offers a motivation of a shared and recognized authority, namely the Catholic Church, in the Bishop's political action text. The claim that this common authority is uniquely sanctioned by God provides a still greater motivation lifting the Church to the highest levels of authority, wisdom, and goodness in the speech's logical framework. This significant theological claim may logically lead the audience to consider the teaching of the Church above political ideology or personal opinion in matters of political debate. The strong central divinely-endorsed authority also helps to provide a confident clarity on contested issues, which can generate united conviction and action from the audience. Finally, the God-given authority of the Catholic Church contributes to a motivation for action by the Bishop's Catholic audience by contributing to the audience's identity in the logical framework as agents of God.

While the logic of this theology provides a powerful motivation for Catholics to actively support comprehensive immigration reform, the theology also contains a weakness for the application of the Bishop's requested action of advocating for comprehensive immigration reform. The Bishop's audience may be motivated by this theology's logic to support Senate Bill 744 because of Catholic teaching and practice. However, this textual theology does not provide the resources to facilitate effective engagement with persons who do not recognize Catholic sources of authority. For instance, Catholics who accept the Bishop's terministic screen and respond by contacting their Congressional Representatives, sworn to uphold the Constitution rather than Catholic Church as their authority, might only offer Catholic teaching and practice as reasons for passing Senate Bill 744. In such a case, persuasion of the Congressperson is unlikely.

Following The God-Given Authority of the Catholic Church Leads to Morality

The second theology I identify in Bishop Burbidge's terministic screen is closely related to the first theology. The Bishop's speech contains a theology that following the God-given authoritative teaching of the Catholic Church leads to morality and rejecting or ignoring the teaching of the Catholic Church leads to immorality. As God, through the Church, is the terministic screen's highest authority and logical grounding, the terms in the terministic screen are evaluated by the authority of the Church. Likewise, agents in the logical framework make choices in light of the authority of the Church. As God makes judgment of morality and immorality through the Catholic Church in the Bishop's terministic screen, agents' moral choices are directly connected to the judgment of the Church. The attitude that the agents take toward the Church is pivotal in their morality; indifference to the Church leads to immorality and esteeming the Church leads to morality.

This theological logic contributes to a motivation for acting on Bishop Burbidge's call to pray and advocate in support of the comprehensive immigration reform bill because the Bishop extensively cited the teaching and practice of the Catholic Church to make a positive moral judgment on supporting the bill. In this theological logic, choosing not to act for what the Church has taught as moral is an act of immorality. Furthermore, the speech's logical framework positions indifference to the Church's moral teaching as an attitude of immorality and delaying action as the agency of immorality. This theologically-inspired terministic screen removes a middle ground for the audience and leaves them with a clear choice between morality or immorality. Most would, of course, choose to act on the side of morality.

However, the theological logic that following the God-given authority of the Catholic Church leads to morality contains points of weakness for potential audience challenges to the Bishop's terministic screen. First, audience members may question the theology because the well-publicized moral failures by Catholic Church leadership seem to contradict the claim of moral authority. Second, the audience may question the theological logic as too narrow a view of morality for contemporary moral issues. Third, the audience may identify apparent contradictions among the vast amount of Church teaching as too ambiguous for moral clarity.

These potential oppositions to the theological logic may be reduced by the breadth and depth of Catholic Church teaching and practice. The term the Church is a single entity, but in Bishop Burbidge's speech there are indications of the diversity and complexity of the Church. Viewing the Catholic Church as a diverse, worldwide community, spanning centuries of ongoing practices and conversations may provide the terministic screen with the complexity and ambiguity to bear occasional moral failure or contradiction and provide the rigor and intricacy to engage with complicated moral dilemmas.

God Calls the Church to Engage in the Sacred and the Secular

Bishop Burbidge's terministic screen contains a theological logic that God has called the Catholic Church to engage in both the sacred and the secular realms of the world. This theology can be seen in the two agencies that the Catholic faithful are urged to engage in the morality cluster of the terministic screen: prayer and advocacy. The Bishop spoke of prayer—communication with God—as a holy and sacred practice of the Catholic Church. The Bishop, speaking with divine authority, was also explicitly direct that “our prayer necessary leads us—to advocacy,” meaning political advocacy to the secular state. Furthermore, Bishop Burbidge supported his call for Catholic laity to communicate with their government leaders about changing a government system by citing Catholic teachings that engaged both sacred and secular.

The theology that God calls the Church to engage in both the sacred and the secular contributes to the speech's logical framework in at least three ways. First, this theology is consistent with the theological logic that God speaks and acts authoritatively through the Catholic Church. In order to fulfill the calling to speak and act on behalf of God in the world, the Catholic Church would need to interact with both God (sacred) and the world (secular). If the Church fails to engage and communicate with either God or the world, then God would not be speaking to the world through the Church. Second, the theology enhances the motivation of the audience to respond to the Bishop's call for action in support of comprehensive immigration reform. The theological logic provides resistance against competing theological, social, or political logics that restrict the Church's divine calling to the realm of the sacred. The theology expands the scope of the Church's calling and identity to include common and shared public life. Finally, the theology that the Church is called to engage in both the sacred and the secular provides a logic that maintains the Church's calling and identity in the sacred while extending the calling and identity into public life. The Church's long-term motivation to respond to calls for political action appears strengthened as this theology provides resistance against competing theological, social, or political logics that threaten to consume the Church's calling and identity into the secular realm.

While the theology contributes to the speech's logical framework, strengthening the motivation for audience members who accept the terministic screen, the logic that God calls the Church to engage in the sacred and secular has potential weaknesses in application. This potential weakness is consistent with the weakness identified in a previous theological logic. While the theology enhances motivation for the audience of Catholic laity to engage with the secular world, the terministic screen does little to provide the audience with resources for engagement with members of the secular world who do not share the audience's source of authority in the Catholic Church. The audience may have access to those resources, but the availability, possibility, or need of resources for secular engagement is unclear from the terministic screen identified in my textual analysis of the Bishop's speech.

God's Moral Authority Applies To Church and State

The fourth theological logic in Bishop Burbidge's terministic screen that I will analyze states that God's moral authority applies to both Church and State. This theology fits logically within the theological emphasis in the Bishop's terministic screen. If, as expressed in the terministic screen, God speaks through the Catholic Church with authority, following Church teachings leads to morality, and the Church is called to engage in both the sacred and the secular, then God's moral authority expressed through the Church would apply to institutions outside of the Church, including the state. In this theological logic in Bishop Burbidge's political action text God's rule extends beyond the Church and includes politics and government. However, in the Bishop's terministic screen, the theology that the Catholic Church speaks and acts with God-given authority also influences the logical framework, seemingly placing the Church in authority over the state.

The theological logic that God's moral authority applies to both Church and state contributes to the audience's motivation to engage with the state. More specifically, the theology contributes to a logical framework that, if accepted, prompts the audience to heed the Bishop's call to ask their congressional representative to support Senate Bill 744 for comprehensive immigration reform. The theological emphasis of God's moral authority extending to the state in Bishop Burbidge's speech offers a sense of confidence for the audience in their political engagement with the state for at least three reasons. First, the audience has confidence in the teachings of the Catholic Church as the authoritative source of God's moral judgments. Second, the audience will likely have confidence in referencing Catholic teachings on political issues because they have developed trust and familiarity with Church teachings in other areas of life. Third, as members of the Church, the audience may have confidence in their theologically-informed identity as God's agents in the world. Acceptance of the Bishop's theological logic that the Church's moral authority applies to the state will incline the audience to follow Church directives to advocate to the state.

While this theology is likely motivational in the logical framework of the speech, it also has the potential to blur the line in the framework's separate roles for the Church and the state. The speech indicates that the nation's immigration laws should follow the Church's moral teachings, even implying that the nation should welcome immigrants as the Catholic Church welcomes all people. This theological logic could raise concerns about a lack of distinction of roles, ethics, and practice between the Church and the nation state. While such a concern would be higher for those who do not accept Bishop Burbidge's terministic screen, the Bishop's logical framework indicates that the Church and the state have distinct roles in the world, and that distinctness might be strained by the theological logic addressed here. However, this potential tension in logic is likely avoided as the terministic screen includes both the logic that the Church's voice has moral authority over the state and the state fulfills a role that is distinct from that of the Church. For example, the Bishop referenced Catholic teachings on the responsibilities of the state in which the Church set the moral standard for the nation state to uphold in its unique role that was distinct from the role of the Church.

Divine and Human Action in the World

A fifth theological logic in the Bishop's terministic screen is that there is both Divine and human activity at work in God's world. This theology can be seen at work in the Bishop's statement that prayer leads to advocacy. The logic of Burbidge's theology will lead an audience member to ask both God and their congressperson to help the immigrants by passing comprehensive immigration reform, recognizing that both agents have the ability to act toward this end.

This theology provides a balance between the responsibility of human agency and the hope of Divine intervention in pressing political issues. The theology carries a logic that human actions make a difference in God's world. In addition to supporting the call for audience members to advocate to government authorities, the logic also prompts the audience to recognize the importance of their choice to act upon the instructions given to them by the Bishop. There is an urgency of action that comes from a logic that claims that human actions matter in God's world. On the other hand, the theology also presents God as active in the world, providing a hope in something beyond their own actions. In the terministic screen, God is active through the teaching and witness of the Church and God is able to directly engage situations. When urging the audience to prayer, the Bishop described God as being able to “guide” human actions. The theology participates in a logic in which an audience member would both request that a human take an action and request that God guide that same human in taking that action.

The theology of both Divine and human action in the world has the potential to create a tension in the logic of Burbidge's terministic screen. The theological logic could create a logical tension in the identity of the agent acting for comprehensive immigration reform. However, the potential tension can avoid a logical contradiction in two ways. First, the agent in Bishop Burbidge's terministic screen was the Catholic laity praying and advocating, consistent with the theological logic, in support of comprehensive immigration reform. Second, the logical fidelity can be maintained as the logical framework has God and humans in a non-competitive relationship. The God who is not a being as a human can act without competing with free human action. In other words, within this theological logic, God can act in the world without violating human agency to act in the world.

God Has Given Dignity to All Humans and the Family Unit

The final theological logic at work in Bishop Burbidge's terministic screen that I will explore in this article is that God has given dignity to all people and all families. The Bishop claimed that all humans have “inherent dignity given to them as members of God's human family.” This theology of Divinely-rooted dignity of all humans animates the rhetoric about immigrants through a logic that people of all nationalities, including immigrants, have a dignity that cannot be taken away and should be honored by all humans and human systems. The theology is supported in the speech's description of the Lord Jesus himself as a refugee while on earth and by the claim that people welcome Jesus when they welcome immigrants. This theological logic is also consistent with the speech's celebration of the universality of the Catholic Church. The Bishop's theology extends the dignity of humans to a God-given dignity for the family unit. The family unit in the Bishop's speech consists of spouses and their children. In the speech's theologically-inspired logical framework, the God-given dignity of the family is recognized by maintaining the integrity of the family unit, that is, keeping the spouses and children together.

In the logical framework of the speech, the theology that all humans and families have God-given dignity contributes to the motivation for supporting comprehensive immigration reform. The theological logic grounds the dignity of immigrants and immigrant families in the terministic screen's highest source of authority, God. The theology frames immigration from the perspective of the God-given dignity of the immigrant and immigrant family rather than considering immigration primarily through other frames such as nationalism, security, or economics. This framing of immigrant as bearer-of-Divine-dignity likely inspires the audience to be receptive to expanding the rights and opportunities of immigrants by supporting comprehensive immigration reform. The theological logic also contributes motivation in the terministic screen because it presents a sharp contrast with the act of accepting the broken immigration system and its ends in the immorality cluster. The nation's current immigration system was presented as keeping immigrants from providing for their family's basic human needs and as violating the integrity of the family by separating family members, and is therefore judged as immoral.

While the theology that God has given dignity to all humans and to the family unit does not seem to create any significant weaknesses in the speech's terministic screen, there are two points of tension worth noting. First, there was not a direct connection established between the theological statement and support of Senate Bill 744. It is logically possible that a person could hold this theological position and logically reject the specific legislation addressed in the speech. While a direct cause and effect connection was not established in the speech, I propose that the Bishop provided enough additional material, such as a theology of the family, the practices of the Church, and statements of Bishops, to support the connection between the theology of human dignity and support of Senate Bill 744, showing the connection consistent with a broad range of authoritative Church teachings. If nothing else, the theology provided logical fertile ground for supporting comprehensive immigration reform. Second, the logic of the transition from the theology of human dignity to the dignity of the family unit appears to have a weakness. The Divine dignity of the family unit was not given as extensive support in Catholic teaching as was the theology of the God-given dignity of humans. However, the lack of an explicit connection might not be a significant issue because, within the logical framework, statements of bishops carry significant authority and presumes connection with the Church's larger body of teaching.

Prayer and Advocacy Theology's Logical Patterns of Motivation

The insights gained to this point in the study provide textually-grounded suggestions as to how the theologically-inspired logical framework in Bishop Michael Burbidge's terministic screen might recommend future rhetoric and actions. I began the article with descriptions of both the context and explicit arguments and definitions in Bishop Burbidge's (2013) statement on comprehensive immigration reform. Next, I identified the Bishop's terministic screen through careful textual analysis of the speech. Then, I provided additional analysis of six theological logics active in Burbidge's terministic screen. Finally, in this section I will identify three ways the Bishop's theological logic explored in this study may influence those adhering to his terministic screen as they encounter other political controversies in the future.

Safeguards For The Integrity of Catholic Identity

The theological emphases in Bishop Burbidge's terministic screen provide a strong motivation for political action while providing logical buffers to deter the Catholic Church from being used as a tool for political action. While the Bishop's statement in support of comprehensive immigration reform was a political action text with a clear call to Catholic laity in the Diocese of Raleigh to act in support of Senate Bill 744, the terministic screen focuses on the Catholic Church as the Divinely-appointed judge of morality and logical grounding. The theological emphases in the Bishop's terministic screen acknowledge the important role of the state, but places the definition of the role of the state and the moral judgment on the actions of the state as subject to the God-given authority of the Church. The theological emphases at work in the Bishop's speech inform Catholic political action with the theological logic that God calls the Church to engage in both the sacred and the secular aspects of the world, deterring the Bishop's Catholic audience, for example, from either neglecting secular advocacy to exclusively practice sacred prayer or neglecting sacred prayer to exclusively practice secular advocacy.

Engagement May Create Opportunities

A second theological inspiration to the Bishop's logical framework that will likely direct the speech's Catholic audience in future political action is the divine calling for moral engagement with the secular world, including the state. While the speech's terministic screen is driven by a clear conflict between morality and immorality and the Catholic Church is placed as the authoritative judge in the conflict, even in issues of the state, the terministic screen also places the focus of the conflict between morality and immorality on the Catholic laity and their choice to respond to Church teaching. The theological emphases in the Bishop's terministic screen contained a cosmic struggle, but did so without a godless other acting as the oppositional agent. This theological logic may lead audience members who embrace the Bishop's terministic screen to engage the secular world, including the state, with a motivation to do what is moral and build or repair the morality that the Catholic Church teaches should be a part of the state and secular public. This theology provides a more positive motivation and constructive perspective for political debate than the theological logics at work in other terministic screens of other clergy political action speeches that place God's agents in conflict with agents of evil or injustice.

Emphasis on Identity Could Limit Opportunities

A final logical outworking of the Bishop's terministic screen is that the theology's strong emphasis upon the authority of the Catholic Church could act as a weakness when the Church answers the theological calling to engage the secular world. As the lack of an evil enemy in the theological logic may help foster political dialogue, the theological emphases on the Catholic Church's authority on moral judgment in all areas of life and that recognizing the Church's authority is the way to morality may limit the Church's engagement with the secular world, not out of animosity, but because of a lack of shared logical groundings. The Catholic audience's sources of authority are recognized, while clearly with a range of interpretations, within the Church, but would not act as a shared logical grounding in secular public advocacy. The argument that a public policy should be passed because it is consistent with Catholic teaching is not persuasive to those who do not identify as Catholic or value Catholic teaching. Claiming the Divine authority of the Catholic Church as the grounding reason in a public policy discussion may deter non-Catholics as they may dismiss the public policy position as only a position for people who claim a Catholic identity and recognize the Catholic Church as their moral authority.

Conclusion

Religion continues to play a role, or several roles, in public and political discourse in the United States of America. While there may be a wall of separation between church and state in the law of the land, the animations and constraints of religions can be observed in the lives and discourses of the people of the land. This study was an attempt to help rhetorical scholars better understand how religion participates in political action rhetoric.

I chose to study a call for political action by a religious leader because it would provide a clear case of the interaction of religion, or theology, and politics in single text. As anticipated, these elements were present in the text's explicit arguments and strategic definitions. In order to reveal the more implicit activity of religion at work in Bishop Burbidge's (2013) Statement of Comprehensive Immigration Reform, performed close textual analysis, using cluster agon analysis and narrative arc analysis, to identify the text's interpretive framework.

The detailed account of the text's terministic screen allowed for the next, and most unique, step in the study—identification of the textual theology. While presumably connected to abstract propositions of theological traditions and explicit theological claims stated in the text, textual theology is district as it consists of the theological logics at work within a text's interpretive framework. Textual theology, the mediating level of theology between the theology of traditions and theological statements in a text, interacts with logics and other rhetorics within the text's terministic screen. In these interactions, the textual theology animates and constrains the logic of the text. The identification of textual theology provides rhetorical scholars textually-rooted pathway to observe how religion works in political action rhetoric.

Once I identified elements of the textual theology in Bishop Burbidge's (2013) Statement of Comprehensive Immigration Reform, I was able to describe specific ways the textual theology logically interacted with other rhetorics in the text. Furthermore, identification of the textual theology provided opportunities to observe the tensions, weaknesses, and motivational functions of the logics. The analysis of these logical interactions within the text's terministic screen also allowed me to predict some future directions the theological logics are prone to in future public discourse.

Future studies could compare and contrast different textual theologies at work in political action texts. As not all terministic screens act the same in texts, I propose that not all textual theologies act the same in texts. As textual theologies have logics that engage in terministic screens, I propose that different textual theologies have different logics that will engage in terministic screens, animating and constraining texts, in different ways. Such a line of study, would assist rhetorical scholars toward a complex and nuanced understanding of how religion works, and is worked, in public and political discourse.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Berger, P. L. (1979). The Heretical Imperative: Contemporary Possibilities of Religious Affirmation, 1st Edn. Garden City, NY: Anchor Press.

Berger, P. L. (1999). The Desecularization of the World: Resurgent Religion and World Politics. Grand Rapids, MI: Ethics and Policy Center.

Berthold, C. (1976). Kenneth Burke's cluster-agon method: Its development and an application. Central States Speech J. 27, 302–309.

Burbidge, M. (2013). Bishop Burbidge Issues Immigration Statement [Video file]. Availkble online at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Si9I3llGM_Q (accessed February 3, 2016).

Burke, K. (1968). “Dramatism,” in International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences, Vol. 7, ed D. I. Sills (New York, NY: Macmillan), 445–52.

Burke, K. (1974). The Philosophy of Literary Form: Studies in Symbolic Action, 3rd Edn. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Calhoun, C. (2011). “Afterword: religion's many powers,” in The Power of Religion in the Public Sphere [Kindle book], eds E. Mendieta and J. Vanantwerpen. Available online at: http://www.amazon.com.

Casanova, J. (2003). “What is a public religion?” in Religion Returns to the Public Square, eds H. Helclo and W. M. McClay (Washington, DC: Woodrow Wilson Center Press), 111–140.

Cavanaugh, W. T., Bailey, J. W., and Hovey, C. (2012). in An Eerdmans Reader in Contemporary Political Theology [Kindle book], eds W. T. Cavanaugh, J. W. Bailey, and C. Covey. Available online at: http://www.amazon.com.

DePalma, M. J., and Ringer, J. M. (2015). “Introduction: current trends and future directions in Christian rhetorics,” in Mapping Christian Rhetorics: Connecting Conversations, Charting New Territories [Kindle book], eds M. J. DePalma and J. M. Ringer. Available online at: http://www.amazon.com.

Edwards, J. J. (2015). Superchurch: The Rhetoric and Politics of American Fundamentalism [Kindle book]. Avaialble online at: http://www.amazon.com.

Gibson, G. (2013). Boehner: No Vote on Senate Immigration bill. Politico. Available online at: http://www.politico.com/story/2013/07/john-boehner-house-immigration-vote-093845.

Grasso, K. L. (2012). “Introduction: theology and the American civil conversation,” in Theology and Public Philosophy [Kindle book], eds K. L. Grasso and C. R. Castillo. Available online at: http://www.amazon.com.

Habermas, J. (2011). “The political: the rational meaning of a questionable inheritance of political theology,” in The Power of Religion in the Public Sphere [Kindle book], eds E. Mendieta and J. Vanantwerpen. Available online at: http://www.amazon.com.

Habermas, J., and Ratzinger, J. (2010). The Dialectics of Secularization [Kindle book]. Available online at: http://www.amazon.com.

Issues. (n.d.). Catholic Voice NC. Available online at: http://www.catholicvoicenc.com/issues.html (accessed April 1, 2016).

Lovin, R.W. (2012). “Consensus and commitment: real people, religious reasons, and public discourse,” in Theology and Public Philosophy [Kindle book], eds K. L. Grasso and C. R. Castillo. Available online at: http://www.amazon.com.

Lynch, J. (2006). Race and Radical Renamings. K.B. Journal – The Journal of the Kenneth Burke Society. Available online at: https://kbjournal.org/lynch.

Mathewes, C. (2012). “Re-framing the conversation,” in Theology and Public Philosophy [Kindle book], eds K. L. Grasso and C. R. Castillo. Avaialble online at: http://www.amazon.com.

Members of congress: North Carolina. (n.d.). Govtrack.us. Avaialble online at: https://www.govtrack.us/congress/members/NC (accessed March 15 2016).

Mendieta, E., and Vanantwerpen, J. (2011). “Introduction: the power of religion in the public sphere,” in The Power of Religion in the Public Sphere [Kindle book], eds E. Mendieta and J. Vanantwerpen. Available online at: http://www.amazon.com.

Olson, K. (2002). Detecting a common interpretive framework for impersonal violence: The homology in participants' rhetoric on sport hunting, “hate crimes,” and stranger rape. South. Commun. J. 67, 215–244. doi: 10.1080/10417940209373233

Roeper, J.G. (2013). Senators Reach a Bipartisan Agreement for Comprehensive Immigration Reform. The National Law Review. Avaialble online at: http://www.natlawreview.com/article/senators-reach-bipartisan-agreement-comprehensive-immigration-reform (accessed March 15, 2016).

S.744 - Border Security Economic Opportunity, and Immigration Modernization Act. 113th Congress. (2013). Congress.gov. Available online at: https://www.congress.gov/bill/113th-congress/senate-bill/744 (accessed March 15, 2016).

The diocese. (n.d.). The Catholic Diocese of Raleigh. Available online at: http://dioceseofraleigh.org/about-us/the-diocese#sthash.RGS5rb6s.dpuf (accessed April 1 2016).

Keywords: cluster-agon analysis, religious rhetoric, social movement rhetoric, comprehensive immigration reform, Catholic social teaching, United States immigration debate, political action rhetoric

Citation: Vining JW (2022) Prayer Leads to Advocacy: The Theological Logic in a Bishop's Statement on Comprehensive Immigration Reform. Front. Commun. 7:712047. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2022.712047

Received: 19 May 2021; Accepted: 16 February 2022;

Published: 16 March 2022.

Edited by:

Denise Voci, University of Klagenfurt, AustriaReviewed by:

Luis Rodolfo Moran, University of Guadalajara, MexicoRobert L. Walsh, Sisseton Wahpeton College, United States

Copyright © 2022 Vining. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: James W. Vining, anZpbmluZ0Bnb3ZzdC5lZHU=

James W. Vining

James W. Vining