- Department of Language and Literature, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim, Norway

Tourism discourse, referring to communication in tourism as global industry, contributes to the creation of tourist spaces, where space is a social and affective construct as opposed to place as a geographical one. Tourists and hosts are part of these spaces and form them with their language practices, both offline and online. This article presents a case study of tourism discourse related to Zanzibar on Instagram, focusing particularly on linguistic repertoires, the role of English in them and language choices as well as their implications for identity construction. A central issue, in line with discourse-centred online ethnography, is the comparison of the digital data with previously collected data from the physical tourist space. Theoretically and methodologically, the concept of (linguistic) transnationalism is central for the study, which uses geotags and hashtags as means of data retrieval and framework of analysis to further this concept.

Introduction

Increasingly large amounts of language are mediated digitally, and linguistic studies on computer-mediated communication abound (e.g., Herring, 1996; Thurlow and Mroczek, 2011; Tannen and Trester, 2013). Many of these focus on language practices specific to the digital sphere and social media, such as hashtagging (Zappavigna, 2015). The importance of language use online has also been acknowledged for the study of New and World Englishes (e.g., Heyd, 2016; Mair, 2018; Shakir and Deuber, 2019). However, many of these studies are based on large text corpora, comprising blog and website data, and do not analyze the specificities of microblogging on social media, whose importance has been emphasized by recent studies employing geotagged data from urban centers in the Global North (Androutsopoulos, 2014; Hiippala et al., 2019; Lyons, 2019). Investigations of geotagged social media data from less urban locations in the Global South remain scarce, however.

This article presents a case study of tourism discourse relating to such a space, i.e., Zanzibar, a semi-autonomous archipelago in the Indian Ocean, on Instagram. The social network is particularly relevant in this regard, given its focus on sharing (holiday) pictures, which are an important “souvenir” among tourists. The investigation, applying a discourse-centered online ethnographic approach (Androutsopoulos, 2008), focuses on the use of hashtags and their pragmatic functions. Some of these functions are similar to those of speech acts like greetings, with a strong focus on phatic communion, which has been proven to be central in tourism discourse (Mohr, 2020). The data stem from a corpus of geotagged posts by tourists and hosts, retrieved using a dedicated application programming interface (API). This method of data retrieval is particularly interesting for the study of World Englishes as it provides a very recent angle of analysis: while collected “in” a specific place (Zanzibar), the posts offer a window of analysis for English(es) used to create space not tied to specific nation states, given the international background of tourists and hosts using Instagram, and away from traditionally studied academic contexts.

Correlating data from the digital tourist space with data and results on language choices and use in the physical tourist space is in line with the demand for relating offline and online data (Androutsopoulos 2008; Leppänen et al., 2020). The analysis also draws on previous in situ fieldwork in Zanzibar, which inspired the research focus on language choices and identity construction via language in the era of globalization. The central aims of this study are hence to find out 1) whether the digital tourist space is equally linguistically diverse as the physical tourist space, i.e., whether English is a “multilingua franca” (Jenkins, 2015), 2) whether there are specific linguistic patterns to be made out in hashtags that might be uncommon in the physical tourist space and 3) what the implications of the (lack of) linguistic diversity for the construction of identities in the digital tourist space of Zanzibar are.

To this end, the paper discusses Englishes and tourism discourse online in Englishes and Tourism Discourse Online, especially touching upon central issues concerning mobility, transnationalism, identity construction (online) and the Zanzibari tourist space. Methods and Data outlines methodological issues relating to data collection, coding and hashtags and their functions on social media, used here as an analytical framework. The results of the analysis are presented in Results and Discussion, touching upon linguistic patterns and themes observed in relation to identity construction. The final section provides some conclusions and an outlook on possible future research.

Englishes and Tourism Discourse Online

World Englishes research, i.e., the study of features of varieties of English around the world as well as the socio-political and ideological implications of these varieties co-existing with other languages (Onysko, 2021), has recently been claimed to have reached an impasse (Saraceni, 2015; Saraceni and Jacob, 2021). The field seems not entirely up to date with recent developments in sociolinguistics and has only started to tackle issues such as globalization, superdiversity and digitization. More research in this vein is hence needed, also accounting more strongly for concerns such as multilingualism and translingualism. Among others, questions as to how English functions in international communication (i.e., considering the interface of World Englishes and English as a lingua franca (ELF) research) and how English is shaped by different modes and media will be central in future research (Onysko, 2021). While some literature on these issues exists (Friedrich and Diniz de Figueiredo, 2016; Bolander, 2020; Lim, 2020), more research inspired by a sociolinguistics of globalization framework (Blommaert, 2010) is desirable and it is one of the aims of this paper to provide such a study.

All these issues are closely related to Englishes being used outside of the traditionally studied academic circles in World Englishes, i.e., “at the grassroots” among non-elite speakers and in heterogeneous contexts with regards to acquisition and proficiency in English (Kubota, 2018; Meierkord and Schneider, 2021: 8). The present paper can contribute in this vein, given its focus on tourism discourse online.

(World) Englishes, Mobility and Transnationalism

The concepts of mobility, tourism, transnationalism, and globalization are closely linked. Transnationalism refers to “multiple ties and interactions linking people or institutions across the borders of nation states” (Vertovec, 1999: 447) and is probably most closely linked to globalization as “complex connectivity […] the rapidly developing and ever-densening network of interconnections and interdependencies that characterize modern social life” (Tomlinson, 1999: 2). Bolander (2020: 678) comments on the difficulty of prying these two concepts apart, as they partly overlap. The differences between them depend on the conceptualization of both terms, however, and there is hence no definite answer. Some researchers have argued that transnationalism has a more limited purview (see also Bolander, 2020). Given that transnationalism is quite important for this article, it is discussed in more detail here.

Vertovec (1999) discusses six ways in which transnationalism has been conceptualized in research across different disciplines. Not all of them can be discussed or are indeed relevant here; I focus on the most pertinent aspects in the following. The most wide-spread notion is that of transnationalism as social morphology, i.e., a “social formation spanning borders” (Vertovec, 1999: 449), which is closely linked to migration and often applied in sociolinguistics (see Bolander, 2020). Tourism as the largest peaceful movement of people across cultural boundaries (Lett, 1989) can be conceptualized as a form of migration, or mobility at least (see Mohr, 2020). Thus, as people move across borders, new networks and communities of practice are formed, which constitute intriguing sociolinguistic environments worth studying. The notion of “community of practice” is usually fitting in these contexts offline but might be more complex in online spaces or at the nexus of both (King, 2019). This is elaborated on later, in Constructing Identities Online. Another conceptualization important for this paper is that of transnationalism as an opportunity for capital, in sociolinguistics often linked to commodified language practices in late capitalism (Bolander, 2020). Given that tourism is “the single largest international trade in the world” (Thurlow and Jaworski, 2017: 187), this is a central aspect in the study of the sociolinguistics of tourism and English in tourist contexts. This has been shown to be directly relevant for the physical tourist space of Zanzibar, where language use of English and the local language Kiswahili, as well as language learning are strongly commodified (Mohr, 2020; Mohr, 2021). Commodification and opportunities for capital are hence expected to play an equally central role for tourism discourse, i.e., “language and communication in tourism as global cultural industry” (Thurlow and Jaworski, 2011: 222), online. Finally, transnationalism can be conceived as hybrid cultural phenomena, i.e., “facets of culture and identity [that] are […] self-consciously selected, syncretized and elaborated from more than one heritage” (Vertovec, 1999: 451) and in that sense closely connected to transnationalism as the (re)construction of place or locality. Set in tourist spaces, the investigation presented in this paper focuses on how discourse and identity construction contribute to the construction of space, i.e., Zanzibar as a tourist destination, digitally.

Due to globalization, languages are generally less associated with nation states and “third wave” sociolinguistics focuses on speaker styles and globalized vernaculars as indexical of identities (Eckert, 2012). In World Englishes research, Bolander (2020: 682) argues, we need more investigations into “how varieties […] are used as resources for constructing place and space, particularly in […] territories where marking difference is/was coupled with drawing territorial distinctions”. This is closely linked to the notion of translingualism as employed by Canagarajah (2020: 560) for instance, which is an extension of the concept of the language repertoire, moving beyond labelled national languages. The language practices in these repertoires are then utilized to construct space, a social and affective construct as opposed to place, a primordial geographical construct (Canagarajah, 2020: 559). In the study of transnational and translingual practices, it is important to document small scale contexts and their entanglement with global dynamics (Al Zidjali, 2019). This is what the current study aims at by documenting a relatively small space, i.e., Zanzibar, and its entanglement with the global dynamics of tourism.

A move away from nationalism and towards transnationalism does not only apply on the conceptual but also on the methodological level in World Englishes. An enhanced focus on linguistics of contact and language practices would be conducive to this (Bolander, 2020) and, in line with previous research on the physical tourist space of Zanzibar (Mohr, 2019; Mohr, 2020; Mohr, 2021), this is one of the present study’s objectives as well. In this regard, the notion of the language repertoire (Benor, 2010) comprising various linguistic resources that a speaker can draw on depending on the context has been central and is again emphasized for this study.

The Physical Zanzibari Tourist Space

In order to further demonstrate some of the issues raised in the previous section and to contextualize the analysis provided later in this paper, a brief description of the physical Zanzibari tourist space is necessary. Zanzibar is an archipelago off the coast of Tanzania, of which it forms part as a semi-autonomous region. Thus, it is subject to the language policies of Tanzania, with Kiswahili as the de facto national language, spoken by ca. 47 million first and second language speakers, besides the 125 other languages spoken in the country. Kiswahili is also the lingua franca of Eastern Africa, with a considerable number of speakers in neighboring Kenya, some users in Burundi, Uganda and a few in Rwanda (Eberhard et al., 2021). Unguja island, the main island of Zanzibar, is also home to Kiunguja, the standard variety of Kiswahili, and the archipelago is hence an important linguistic center in East Africa. English is the de facto national working language of Tanzania (Eberhard et al., 2021). In World Englishes research, the country has been argued to be an “Outer Circle” country where English is used as a second language (Schmied, 2008). However, it has been argued recently that English is in fact an additional language in Tanzania (for a recent account see Mohr, 2022). This seems different in Zanzibar, where tourism accounts for a major part of the local economy and many Zanzibaris learn English in order to be eligible for employment in the tourist sector (Mohr, 2020; Mohr, 2021).

Tourism has an important impact on language use on the archipelago. Thus, Zanzibaris spend a lot of financial resources on acquiring English semi-privately, i.e., in tuition classes taught by (retired) school teachers or in language classes at NGOs, given that many Zanzibaris do not think that language instruction in schools is sufficient to acquire the language fluently (see, Mohr, 2021). Besides English, many acquire additional foreign European languages like Italian or German in order to be even more attractive for the job market and to better accommodate tourists and their mother tongues (Mohr, 2019; Mohr, 2020). This closely relates to the abovementioned conceptualization of transnationalism as an opportunity for capital.

The most interesting phenomenon observed in this space and related to transnationalism as an opportunity for capital is what has been termed “Hakuna Matata Swahili” (HMS) (Nassenstein, 2019). It refers to a pidginized version of Kiswahili, allegedly developed for the tourists who usually do not speak the language (Mohr, 2020). It exhibits similarities to “mock languages”, such as Mock Spanish as described by Hill (1998) for the United States. Interestingly, the Zanzibari participants in Mohr (2019, 2020) report that it is also frequently employed for communication not only by but with tourists as it supports selling touristic goods and services. To this end, it is also printed on souvenirs, postcards etc., thus making language directly purchasable.

In view of the many languages that are spoken in Tanzania, Zanzibar is a highly multilingual space and Zanzibaris have highly diverse language repertoires.1 They draw on the various language practices comprised in these resources depending on different contexts and interlocutors (Mohr, 2019; Mohr, 2020). This is an illustrative example of translingual practices (see Canagarajah, 2020). When adding the tourists’ various native languages and English to this already great linguistic diversity, a “superdiverse” space (Vertovec, 2007) is created that lends itself to investigations into multilingualism and language contact. In these spaces, English can hence be considered a “multilingua franca”, i.e., one of many possible language choices in a multilingual space (Jenkins, 2015). This superdiversity is similar to digital spaces, which have been claimed to be inherently superdiverse, irrespective of tourism (see Leppänen et al., 2020). An investigation into a digital tourist space hence promises to be doubly intriguing.

Constructing Identities Online

Contemporary, “third wave” sociolinguistics (Eckert, 2012) is concerned with the indexicality of speech styles with regard to speaker identities. Speakers draw on various means of constructing meaning, i.e., verbal, discursive and semiotic resources, thus indexing (lack of) commonality, connectedness and groupness (Leppänen et al., 2020: 25). Nowadays, identities are increasingly viewed as temporary interactional positions “that social actors briefly occupy and then abandon as they respond to the contingencies of unfolding discourse” (Bucholtz and Hall, 2005: 591). Thus, identities are socially and situationally constructed and anything but fixed. In our globalized world, they are also complex and usually multiple, depending on individuals and groups alike. Turkle (1995: 180) mentions that “people experience identity as a set of roles that can be mixed and matched”. These dynamics are closely linked to the concept of community of practice and related notions as discussed by King (2019). Online, where there might be no shared (strong) feeling of belonging among members of a group sharing similar interests, we might rather be concerned with affinity spaces (see also Gee, 2005), as more generalized social spaces (King, 2019). Publics, i.e., indefinite, unaccountable audiences addressed through circulated discourses or identity performances (Warner, 2002), are especially relevant with regard to social media. These concepts are often interrelated and co-occurring online, with affinity spaces containing sub-groups in the form of communities of practice, for instance (King, 2019). As will be shown in the analysis, the digital Zanzibari tourist space is also complex in this regard.

Situational dependency and complexity of identities specifically hold true for online digital spaces, where sociolinguistic research into identity work is a key topic (see Thurlow and Mroczek, 2011; Tannen and Trester, 2013; Leppänen et al., 2020). There, two factors that have also been shown to be central for the sociolinguistics of tourism in general and of Zanzibar in particular, are the playfulness of identity construction and the intersection of identity work and authenticity (Thurlow and Mroczek, 2011; Leppänen et al., 2015). Playfulness refers to language use being playful in tourist contexts in order to appeal to tourists on vacation, such as HMS in Zanzibar mentioned in the previous section. Authenticity, often aimed at by stylizing the location using a local language (see Salazar, 2006 on Tanzania), is another central aspect of many tourist spaces. With regard to digital spaces, playful language use has been attested frequently online and on social media, where users draw on different semiotic resources, such as emojis, pictures and verbal language, when communicating (e.g., Thurlow and Mroczek, 2011; Thurlow and Jaroski, 2020). Authenticity plays a role for the performance of identities online in that the disembodied nature of online communication apparently makes it easier for users to express themselves in ways that would normally be perceived as inauthentic (Turkle, 1995), for example using a variety of English spoken in another country. Chong (2020) reports an example from Singapore, where young Singaporeans employ different sociolinguistic resources to construct various online personae.

As the similarities between physical tourist spaces and online spaces demonstrate, there are parallels between offline and online language use. Thus, it has been argued that we do need research into connections between offline and online discourse, as these are an important aspect of digital language use (e.g., Androutsopoulos, 2008; Leppänen et al., 2020), especially where translocally connected groups are concerned (Blommaert, 2017). This would also thwart the too narrow focus on the particularities of digital discourse as present in the beginning of the field (Mair, 2020). With regard to identity work, it has been argued that online identities are an extension of offline identities, where language choices and code-switching illustrate different facets of a person’s identities, depending on their perceived or desired social positioning (Barton and Lee, 2013: 55–68). This is particularly interesting in superdiverse spaces like the tourist space of Zanzibar (Mohr, 2020) or online spaces in general. It is this interface that the present paper aims at investigating.

Methods and Data

Many studies into World Englishes online are based on large text corpora and do not analyze the specificities of microblogging and multimodal meaning making on social media in detail. Some studies do exist however, sometimes also employing geotagged data (e.g., Hiippala et al., 2019; Lyons 2019). Investigations of less urbanized locations in the Global South remain scarce, however. The data presented here stem from such a space, i.e., from tourism discourse associated with Zanzibar in the social network Instagram. The network’s focus on pictures, which are a popular “souvenir” among tourists and often used to advertise services, hotels etc., among hosts, makes Instagram an ideal site for data collection. The general methodological framework applied is discourse-centered online ethnography (Androutsopoulos, 2008), combining participant observation of several Zanzibar tourism related accounts via an own Instagram account and the retrieval of posts via a dedicated API. The latter is described in more detail in the following section. In the future, interviews with key stakeholders are planned.

Data Collection

The move away from methodological nationalism (Schneider, 2019) and towards a more language contact oriented, transnational methodology mentioned earlier in (World) Englishes, Mobility and Transnationalism is one of the challenges this paper aims at addressing. As mentioned above, the investigation is based on Instagram posts retrieved using geotagged data from Zanzibar, that means Stone Town on Unguja island in particular. This might at a first glance seem rather nationally oriented but the geotags were not chosen out of a concern for Zanzibar as a place where a certain language variety is spoken that needs to be studied (even if that might ultimately be an interesting issue for research in World Englishes). They were rather employed for two reasons:

a) To create a manageable window of analysis on the digital tourist space

b) To create an unbiased window of analysis on the digital tourist space, as far as topics and language practices are concerned

The first issue refers to the potential size of the digital tourist space, which would be difficult to analyze in a meaningful way within a qualitative framework, at least within the scope of this paper. 30 posts were retrieved weekly from September 2019 until September 20202 via a dedicated API in Twitter, subsequently feeding R. This was necessary due to some difficulties with the Instagram API (see Lyons, 2019 for a more detailed discussion of this issue). Posts were retrieved from Stone Town and 5 kms around the city; an extension to other tourist locations where data for the study of the physical tourist space had been collected previously (Mohr, 2019; Mohr, 2020; Mohr, 2021) turned out to be futile due to a lack of social media activity there. Social media activity in general was limited, especially after the start of the COVID-19 pandemic and on a few occasions, there were fewer than 30 posts that could be retrieved per week.

The posts were subsequently “cleaned”, i.e., three categories of posts were excluded from the data set. This refers to 1) posts that were not cross-posted on Instagram, 2) posts from accounts that are private and 3) posts that were not related to tourism in any way. With regard to 1), retrieving data via Twitter was necessary as mentioned above. However, posts that were only posted on Twitter and not on Instagram too, i.e., cross-posted, were not relevant for the study with its focus on Instagram. Concerning 3), the criterion was not interpreted very strictly so as not to restrict the data set too much. The determining factor were the participants themselves, i.e., participant profiles and previous posts were investigated closely in order to determine whether someone might have been a tourist in Zanzibar at the time of posting. Posts by hosts were in general easier to determine. The content of the post was another criterion considered. For instance, a post by a local Zanzibari, reading only “family” and showing a family picture, was excluded from the analysis. This overall procedure left a corpus of 363 posts (out of 534) in total. However, as indicated briefly above, the number and quality of posts changed considerably after the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, and only the data from 2019 are hence considered here. They comprise a corpus of 205 posts with 1,842 hashtags in total. The significance and use of hashtags are outlined in the next section of this article.

Issue b) above is related to an inductive approach to data collection, which is in line with ethnography in general. The application of geotags for data retrieval did not pre-determine the choice of participants, topics discussed by the participants of the tourist space, nor did it pre-determine language practices (including scripts or other semiotic material such as emojis) chosen in that space. Searching for particular key words would have been another option for data retrieval but since I wanted to treat the nature of topics forming part of tourism discourse and hence creating the tourist space as an empirical question, I abandoned that idea. The use of key words would also have pre-determined the language practices I could have investigated and since the choice of these practices was another of the empirical questions to be answered by the study, I did not want to impact them. In this way, I applied an approach that was as inductive as possible and I pre-determined the tourist space as little as possible. This methodology then again emphasizes the close connection of place to the construction of space as suggested in transnational and translingual approaches.

Analytical Framework

Social media posts consist of many different components, drawing on diverse semiotic material (Zappavigna, 2015). In order to understand them in their entirety, all of these components have to be analyzed. Since this is the first study on digital tourism discourse associated with Zanzibar, choosing a certain focus was necessary for practical reasons. Hence, hashtags were chosen as an analytical framework based on their important functions on social media, linking different parts of the posts. Other material (text in the posts, pictures, likes) are briefly commented on where necessary. They will be the object of future analyses.

Hashtags have various functions that have been discussed extensively in the literature (e.g., Page, 2012; Zappavigna, 2015; Zappavigna and Martin, 2018). There are four functions that are relevant for this study. Others have put forth groupings into three main functions (e.g., Sykes, 2019) but a slightly more fine grained approach seemed more fruitful here. The first one is supporting visibility and findability (Page, 2012). Thus, posts can be found by other social media users interested in a specific topic and Instagram is indeed searchable for specific hashtags, which can also be followed. A user will employ a specific hashtag to be found by others interested in that topic, and possibly to generate likes. These have important phatic functions on social media in a similar way to hashtags. The visibility function is closely related to several other functions of hashtags that have been discussed in the literature. One of them is folksonomic topic marking emerging through community use (Zappavigna and Martin, 2018). This refers to users tagging their posts for what they perceive to be important issues in their posts. By doing so, they simultaneously enact the ambient community (Page, 2012), i.e., they create a subcommunity of, in this case Instagram, users interested in the same topic. Finally, they might express their attitude towards that topic or the post in general (in case it contains material they did not create themselves) and thus hashtags fulfill a meta-discursive function (Page 2012; Zappavigna, 2015). These four functions were central for the analysis provided in this article and for the coding scheme outlined in the next section.

Data Coding

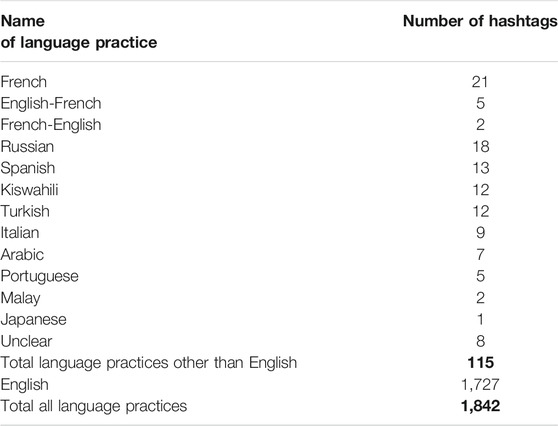

The hashtags were coded according to several parameters using the NVivo software tool (QSR International Pty Ltd, 2020). The first parameter was language practices, i.e., English, French etc. The names for these practices were based on names that the participants in the investigation of the physical tourist space of Zanzibar used themselves (Mohr, 2019). They do not entail that I myself view them or other languages as bounded entities. For a discussion of the difficulties related to differences in epistemic interests and the choice of the “proper” ontology in sociolinguistics, see for example Røyneland (2020). Table 1 shows an overview of the language practices used in the hashtags. As can be seen there, the majority of the 1,842 hashtags (N = 1,727 = 93.8%) are in English. That means that the various and oftentimes large language repertoires of the Instagrammers are not utilized fully in hashtags in the digital tourist space of Zanzibar.

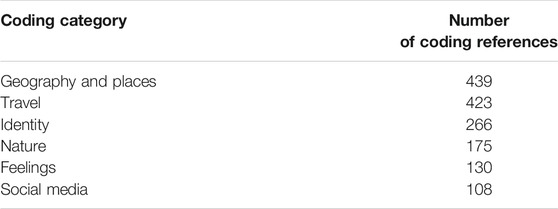

Secondly, the data was coded semantically. This resulted in 133 codes + 1 “other” category subsumed under 22 + 1 larger (“super”) categories. The most frequent of these are shown in Table 2.

An example of the abovementioned codes and super-categories is “animals” with 69 coding references, which comprised the sub-categories “cats,” “protection,” “sea creatures” and “wildlife.” Double coding was generally possible and necessary due to the complex nature of hashtags. An example of this is shown in (1), a hashtag which was coded for “feelings > positive”, “geography and places > earth”, “time” and “travel > vacation”.

1) #beautifuldestinations_earthearthfocuswonderful_placesourplanetdaily

The third coding type referred to the hashtags’ socio-pragmatic functions mentioned above, i.e., enacting the ambient community, expression of attitude, topic marking, supporting visibility/findability. Here, double coding was possible but rarer.

Like every method, this one had a few weaknesses. One issue that needs to be mentioned in this regard is that of naming language practices. While I do want to move away from conceptualizing languages as bounded entities, I did employ commonly used language names for coding. In this context, I employed these names as coding categories only. Another problem that I encountered relates to the difficulty–if not impossibility–of clearly delineating languages and attributing linguistic material unequivocally to a particular language practice in superdiverse contexts. There are several words that are frequent in tourism discourse, and could be attributed to various language practices, among them voyage, which could be French or English for example, and wanderlust, which could be German or English. In these cases, contextual decisions were made, coding the material according to the language practice used mainly in the accompanying post. This is shown in example (2)3, where #wanderlust was coded as English. Given the multilingual and translingual nature of the posts, these decisions are not completely incontrovertible though and eight cases that could not be determined remained (see Table 1).

2) Africa isn’t all desert […] #africa #tanzania […] #travel #wanderlust #backpacker

The other problem that I experienced was my limited language knowledge. I retrieved linguistic material in languages that I do not speak (fluently), and determined the meaning of these posts and hashtags by using Google Translate. This generally worked well but I had to ask colleagues for their support in some cases. This specifically applied to material in what turned out to be Russian but was labelled as various Slavic languages by Google Translate. This emphasizes that working on projects like these makes interdisciplinary collaboration highly desirable.

Results and Discussion

In the following, the results are presented according to the coding categories mentioned in the previous section, i.e., language practices chosen and other linguistic patterns observed in the hashtags (Linguistic Patterns) as well as themes observed, i.e., semantic categories (Observed Themes). A particular focus is on English in contact with other language practices, given the results shown in Table 1.

Linguistic Patterns

General Patterns

Generally, there were two translingual linguistic patterns that could be observed. Either language practices were mixed within a single hashtag or they were switched across hashtags. Mixing within one hashtag was relatively infrequent though as shown in Table 1. Thus, only French and English were combined and only in 7 out of 1,842 hashtags. As can also be seen in the table, the pattern English + French was more frequent than French + English. The individual hashtags that could be found were (French material underlined): #travelnoire, #travelafrique, #Blackvoyageurs, #eurasietravel and #petitejoys. Of these, #Blackvoyageurs made up almost half of all tokens. It was coded for “travel” and “identity” > “Black identity”. Given that these two categories were among the most frequent super-categories, it is worth investigating these instances in more detail. #Blackvoyageurs occurred in four separate posts by two different Instagrammers. One of them had deactivated their profile at the time of writing this article. The anonymized post is shown in example (3).

3) Glowing different with [product name]

.

.

.

For a feature, follow and tag [account name] and use the hashtag #[account name]

.

.

.

You glow differently when you’re on holiday

.

.

.

#womenwhoexplore #weworktotravel #passionpassport #blackvoyageurs #blackgirltravelslay

#iamtb #btravelcreators #travelnoire #blackgirltravelmovement #blackgirlstraveltoo

#blacktravelfeed #blacktravelmovement #blacktraveljourney #travelisthenewclub

#blackandabroad #urbaneventsglobal #mytravelcrush #weworktotravel #travelingwhileblack

#wanderlust #blacktravel #blackgirlstravel #melanintravel #blacktravelhackers

#blacktravelista #workhardtravelwell #soultravel #blacktravelgram #blackpassportstamps

In this example, Black identity seems to be one of the central issues to be emphasized by the hashtags #blackvoyageurs, #blackgirltravelslay, #btravelcreators, #travelnoire, #blackgirltravelmovement, #blackgirlstraveltoo, #blacktravelfeed, #blacktravelmovement, #blacktraveljourney, #blackandabroad, #blacktravel, #blackgirlstravel, #melanintravel, #blacktravelhackers, #blacktravelista, #blacktravelgram, #blackpassportstamps, as does female identity to some extent, as expressed in the hashtags #womenwhoexplore, #blackgirltravelslay, #blackgirltravelmovement, #blackgirlstraveltoo, #blackgirlstravel. All these hashtags together then create a sub-community on Instagram (the post had received 129 likes at the time of retrieval), i.e., Black female travelers, supported by one of the abovementioned functions of hashtags. Given its prominence for the authors of the posts themselves, which will be discussed further in the remainder of the analysis, this sub-group is reminiscent of a community of the imagination, which is formed as part of the larger affinity space. These communities are based on envisioned social relationships with others contributing to a strong sense of belonging (see also Wenger, 1998; King, 2019).

At the same time, some of these hashtags mark topics such as work and travel and support findability, especially a tag in -gram like #blacktravelgram, which is frequent (see Ludic Tendencies and Linguistic Creativity for further details). This function, as well as community creation, seems to be central to the post that has an advertising function. The use of voyageurs as a French word seems to support this, as the advertisement is for a beauty product. Further, the use of a language practice other than English appears to emphasize a certain air of worldliness that the Instagrammers want to convey and that seems important for the digital Zanzibari tourist space. This is also stressed by the use of the German loanword wanderlust in one of the hashtags.

The other posts using the hashtag #Blackvoyageurs emphasize all of the above arguments and stress pride in Black (female) identity, using for example hashtags like #blackslayingit [as shown in example (4)]. They were all posted by an organization “Blackvoyageurs” that has 153,000 followers at the time of writing and aims at advertising cultural and travel experiences around the world. Most posts show pictures of Black women, emphasizing their central role for that organization and the sub-community created. The issue of themes and various identities expressed via hashtags is discussed in more detail in Observed Themes.

4) Beach bum. So sad it’s all come to an end. Could really be an island girl this place makes me so happy. Back to reality this time with a tan and with a light heart heart

Corps de plage. Tellement triste que tout soit fini. Je pourrait vraiment être une fille des îles, cet endroit me rend si heureux. Retour à la réalité cette fois-ci avec un bronzage et un cœur léger

#Blackvoyageurs #Zanzibar #Tanzania

#Zanzibar #Tanzania

#melaninonfleek #melanin #afropolitan #wanderlust #instatravel #blacknomad

#SurpriseTrip #AfricanAdventure #blacktravel

#blackking #blackisbeautiful #blackbeauty #melaninqueensonly #melaninart #blackrockingit

#africansthatslay #blackslayingit

#melanina #rainhanegra #negroelindo ( [user name])

[user name])

As can be seen at the end of example (4), where the camera emoji and a username are mentioned, the post was a re-posted picture from another user and hence the “Blackvoyageurs” were not in fact in Zanzibar when they posted. This illustrates the rather analytical nature of geotags, which might not be directly related to actual places in the world but rather create social spaces online. At the same time, this emphasizes the transnational nature of this social space, including not only participants from or in Zanzibar but also those who in some way feel affiliated with the archipelago and local tourism, i.e., this affinity space.

Another issue that is apparent in example (4) is the relatively frequent use of other language practices than English. This directly relates to the other linguistic pattern mentioned at the beginning of this section, namely that of switching language practices across hashtags. Thus, the hashtags above start in French, move to English with #melaninonfleek and to Portuguese with #melanina. Interestingly, both of these hashtags marking switches refer to skin color, a central concept for this group in terms of the identity that is indexed. Different language practices are also used in the posts themselves, English and French here. This emphasizes the diversity of the group writing but also the audience or public appealed to as do the multilingual hashtags, which can be found by Instagrammers using these other languages. The other two posts tagged #Blackvoyageurs were structured in the same way, with the English post preceding the French post and mixing different language practices in the hashtags. Transnationalism and transnational identities are clearly invoked here, most importantly as social morphology and as hybrid cultural phenomena (Vertovec, 1999).

The Use of Kiswahili

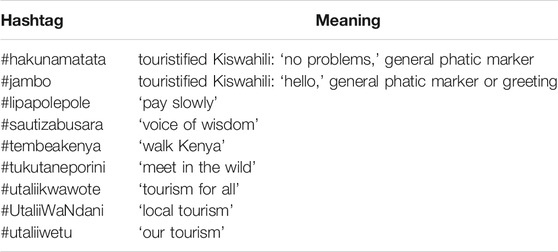

Kiswahili as the official national language of Tanzania and Zanzibar deserves some attention. As can be seen in Table 1, there were only very few Kiswahili hashtags (N = 12). They are shown in more detail in Table 3.

The fact that there is little Kiswahili used in the hashtags is not surprising, given the general lack of fully fledged Kiswahili in the physical tourist space, especially among tourists. Tourists usually do not learn Kiswahili beyond a couple of formulaic phrases, and neither do migrants from outside of Tanzania and East Africa who come to work in the tourist industry (Mohr, 2020). Zanzibaris themselves use HMS, a pidginized form of Kiswahili, to communicate with tourists, which might be another reason why there is little fully fledged Kiswahili in the hashtags.

Of the hashtags mentioned in Table 3, #hakunamatata and #jambo occurred together, as did #lipapolepole and #tembeakenya, and #utaliikwawote and #utaliiwetu, thus reducing the number of posts with Kiswahili hashtags to 9 (there are 4 tokens of #hakunamatata in total). All of these hashtags, except for #UtaliiWaNdani, which accompanied a Kiswahili post, accompanied English posts. This emphasizes the absence of Kiswahili and its token or exotic status in the digital tourist space of Zanzibar even more. Again, this pattern is not surprising given that only two of the posts were written by (local) tourism providers, while all others were written by tourists. The post tagged with #UtaliiWaNdani was written by a local tourist from mainland Tanzania, which explains the language choice. The presence of Kiswahili in the hashtags does certainly not contribute to the findability of the posts. Instead, it seems to stylize and exoticize the location, a function that has been attributed to indigenous languages in many tourist locations (see Salazar, 2006 on Tanzania). Their function is rather that of enacting and appealing to the ambient (tourist) community that is acquainted with a truncated but not a fully fledged version of Kiswahili. This emphasizes the importance of performativity, of putting on a certain identity in the digital tourist space, which is similarly central in the physical tourist space (Mohr, 2020).

Hakuna matata and jambo, part of HMS, create a rather touristified, pop-cultural, even “disneyfied” space online. They are central lexical items of HMS (Nassenstein, 2019) and hence very important for tourists. Two of the posts they accompany are especially noteworthy. They both include several pop cultural references as could be expected with these hashtags. These refer to the “Jambo song” and Walt Disney’s “The Lion King” movie (Nassenstein, 2019; Mohr, 2020). The latter is explicitly mentioned in one of the posts [example (5)] and implicitly in the other [example (6)].

5) I’m sorry… I had to do it again!!!!

People actually say it ALL the time…it’s not just for #disney •

•

•

#hakunamatata #whatawonderfulphrase #handsome […] #funny #sunshine #airport […] #zanzibar #danzibar #tanzania #salsa #bachata #kizomba #singing #fun #friends

6) This Lion didn’t sleep tonight!.

.

.

.

.

.

.

#doingthesupermanthing #isolemlyswearthatiamuptonogood #livingmybestlife […] #happy #thisisthedecadeivebeenwaitingfor […] #handstandsaroundafrica #becauseiwasinverted […] #goodvibes #positiveenergy #hakunamatata […] #travel #wanderlust […] #handstands […] #handstandsaroundtheworld #mischiefmanaged #upsidedown […]

In example (5), there are several explicit references to Walt Disney, such as the hashtag #disney, and the song from the Lion King movie that made the expression hakuna matata so famous. Further, the pictorial material included in this post is a video showing the Instagrammer (a choreographer and life coach) and their group of friends, all starting to sing the Hakuna Matata song. This emphasizes that for most tourists, hakuna matata is associated with Walt Disney. Interestingly, they say in the post that “it is not just for #disney”, thus wanting to emphasize the authenticity of the phrase and creating a type of insider identity with regard to Zanzibari and African culture (i.e., they enact the ambient community), possibly also stressing their worldliness. Absurdly, the post emphasizes exactly the opposite, as this pidginized form of Kiswahili is only used with tourists, and outsiders who do not know much about Zanzibari or Kiswahili culture. The lack of fully fledged Kiswahili in the presence of pidginized Kiswahili mostly used by tourists is reminiscent of Mock Spanish as described by Hill (1998). Mock Spanish refers to grammatically incorrect and/or hyperanglicized Spanish as used by White Americans in the South-West of the United States, often linked to particular stereotypes of Spanish speakers in that region. Similar phenomena have been reported by Blommaert and Backus (2011) with regard to various languages and their acquisition in the era of globalization. Some of the stereotypes described by Hill, e.g., laziness (emphasized by the frequent use of mañana in Mock Spanish), can also be found in HMS, e.g., the use of pole pole “slowly” as a general phatic marker. In contrast to the very explicit reference in (5), the pop cultural reference in example (6) is subtler and more ambiguous. “This lion didn’t sleep tonight” could refer to the Disney movie but also to a popular pop song first performed in 1939 by Solomon Linda called “Mbube” (‘lion’) in isiZulu, before it was translated into English under the title “The lion sleeps tonight”. The song was subsequently adapted and performed by several artists, one of the most common adaptations being the one by The Tokens from 1961. It is world famous and could very well be meant here. The other pop cultural references in the post are equally interesting. #isolemlyswearthatiamuptonogood and #mischiefmanaged refer to the Harry Potter Universe. These, together with #hakunamatata, and many of the other hashtags which are very positive as expressed by their coding “feelings > good,” for instance #goodvibes and #positiveenergy, convey a positive attitude of the Instagrammer. This also emphasizes the attitudinal function of hashtags and the disneyfied, movie-like nature of the space created by this hashtag. Further, the post in example (6) is very playful, as is example (5), due to these hashtags and the accompanying picture, which included a handstand (not shown for privacy reasons). This is taken up in the hashtags #handstands, #handstandsaroundafrica and #handstandsaroundtheworld. Ludic tendencies like these are common in tourist contexts and are elaborated on in the following section.

Ludic Tendencies and Linguistic Creativity

Ludic tendencies, i.e., pop cultural references in the posts and in pictures and videos, are common in tourist contexts (Dann, 1996). They convey a laid-back tourist identity and in hashtags seem to enact the tourist community on social media, and hence have an important function. These hashtags are also easily findable, by tourists and people interested in the pop cultural content referred to alike, and thus exhibit another central function of hashtags.

Ludic tendencies are closely linked to linguistic creativity and, as observed in hashtags, equally contribute to the enactment of the relaxed tourist community or affinity space. This creativity is visible in language play and specific word formation patterns. Here, the possibilities of multimodal meaning making become especially visible. Using upper and lower case letters in clever ways, tourists [see example (7)] and hosts [see example (8)] hence make use of the possibilities provided by script online.

7) #TANnedZANIA

8) #AGameOfTones

Both of these examples refer to tanning, a central activity among many tourists. This emphasizes the hashtag’s function of enacting the ambient tourist community. This seems to extend beyond Zanzibar in example (8), as the hashtag was used by a tour provider that also offers services in mainland Tanzania, the Maldives, Australia and Europe; all of these destinations are also mentioned in the other hashtags accompanying the post in question. On the one hand, this illustrates that worldliness is a central concept for tourists that is catered for by hosts. On the other, it demonstrates that it might not only be a local, Zanzibari tourist community that is enacted with these hashtags but rather a global, transnational one.

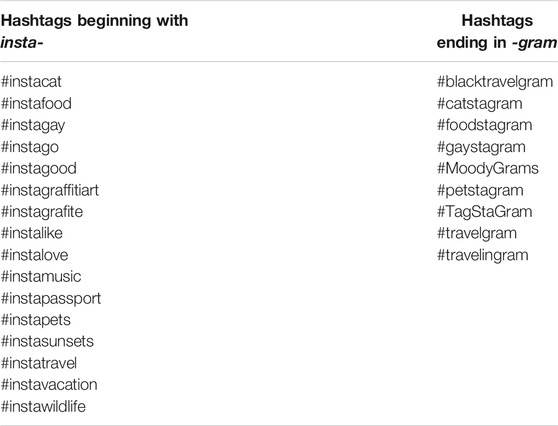

In-group identity is also expressed by word formation processes such as compounding and blending. These are frequent with respect to semantic categories like Black identity, LGBTQ+ identity and traveler identity (three sub-groups and possible communities of the imagination), and often these formations include references to Instagram. Examples of the first were given earlier in General Patterns such as #blacktravelgram, examples of LGBTQ+ references are #gaystagram, #instagay, the latter also referring to Instagram and other examples being #travelgram, #travelholic and #instavacation, #instatravel. Insta- and -gram are extremely frequent in hashtags on Instagram and combine with all kinds of lexemes. Table 4 shows all hashtags beginning with insta- or ending in -gram in the data.

These hashtags fulfil the function of enacting sub-communities or groups on Instagram centering around specific topics, the ones that emerge in Table 4 seem to be the abovementioned Black and LGBTQ+ identities and travelers, as well as food, pet and specifically cat lovers. #instagood was especially frequent and is a bit different from the other hashtags in that it rather expresses an attitude towards a post. Linguistic creativity in marking in-groupness and the coining of new words is a commonly observed strategy in sociolinguistics and has also been documented for youth languages, for instance (Hollington and Nassenstein, 2015). The issue of identities performed and indexed by these patterns and the semantics of the hashtags are discussed in more detail in the following section.

Finally, another brief comment on the patterns observable in Table 4 is necessary. Generally, formations in insta- were more frequent (both concerning types and tokens) than those in -gram but the reason for that remains unclear. From a structural perspective, these formations are blends. Given their high frequency, they seem to be an important in-group marker and an integral part of the language repertoires of specific sub-communities on Instagram.

Observed Themes

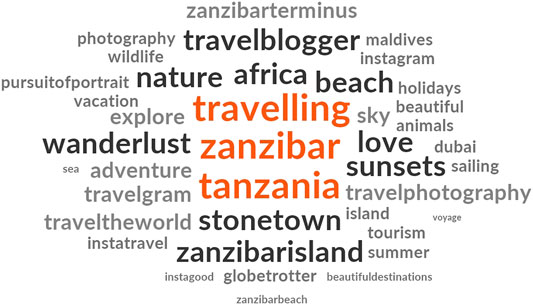

As shown in Table 2, there were six coding super-categories, i.e., larger themes, that were frequent in the data. Most of them are not surprising given the posts’ concern with tourism: they referred to geographic locations, nature or traveling, as well as social media (e.g., the insta- and -gram formations mentioned above). This is also illustrated in Figure 1, showing the 30 most frequent hashtags in the data, where #travelling, #zanzibar and #tanzania are the top three. Other hashtags noteworthy here are #sky and #sea, which are hashtags belonging to the category of “nature” and #instatravel and #instagram, which were coded for the category “social media.” The category “feeling,” which was also part of the six most frequent super-categories, is represented by hashtags such as #instagood and #love in the word cloud.4

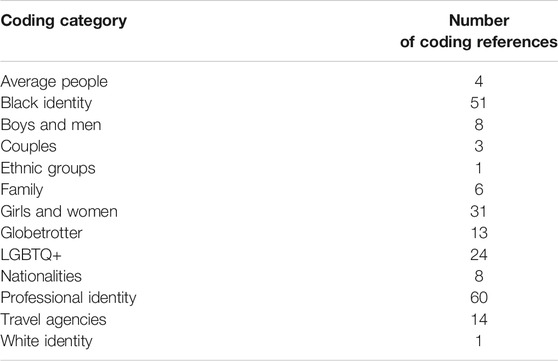

Identity was a frequently coded category; interestingly, it is only represented by #globetrotter in the word cloud. While this might imply that references to identity were not that frequent after all at a first glance, the lack of references among the 30 most frequent hashtags might rather suggest that the category as such is diverse. This is emphasized by Table 5, which shows an overview of its sub-categories and their frequency in the data.

As can be seen in Table 5, there are certain sub-categories of the “identity” category that are more frequent than others. These are “Black identity,” “girls and women,” “globetrotter,” “LGBTQ+,” “professional identity” and “travel agencies,” each with more than 10 coding references. The frequency of categories related to traveling is again not surprising given that the study is concerned with tourism discourse. Some remarks are in order though, specifically concerning the globetrotter category, which included the word itself as well as #worldtraveller. These hashtags were exclusively used by tourists, some of them travel bloggers. Their posts included several other hashtags referring to traveling and (semi)professional identities, such as blogger. An example is shown in (9). In this case, the professional identity is also related to other functions of hashtags which are important for social media personae, such as #follow and #like. These hashtags are hence central for the performance of professional identities on Instagram.

9)  TZ•

TZ•

#beautiful #paradise #zanzibar #tanzania […] #travel #intrepid […] #explore #africa #safari #visitafrica #wanderlust #adventure #backpacker #nomad #traveller #livelife #worldtraveller #travelbug #blog #blogger #follow #like #share

Hashtags such as #travel, #explore, #safari, #wanderlust, #adventure, #backpacker, #nomad, #traveller, #worldtraveller and #travelbug in (9) all refer to the Instagrammer’s identity as a traveler, as well as the appeal of traveling. This is emphasized by hashtags such as #intrepid, referring to desirable character traits for travelers, and #livelife, which stresses that traveling is a desirable activity that makes life worth living. Framing this with references to Zanzibar as a #beautiful location, even a #paradise, makes this identity even more desirable. The fact that no reference to nationality is made whatsoever (and nationality was in general not a frequent sub-category as shown in Table 5) seems to emphasize the Instagrammer’s identity as an international traveler–on their travels, nationality seems to become less relevant. This is striking, given the fact that nationalities are very much relevant when it comes to crossing borders, as certain passports allow for easier travel than others. Not mentioning nationality hence might hint more at this and other Instagrammers not needing to worry about such matters and hence creates a certain kind of in-group as well. In any case, nationality is rarely expressed in hashtags and this emphasizes the transnational nature, via a reconstruction of place or locality, of the digital tourist space.5 As mentioned above, other professional identities were also sometimes mentioned. Many of these are event planners, specifically wedding planners when referring to the poster’s identity. Hashtags include #destinationpartyplanner and #nigerianweddingplannerhouston. While these hashtags certainly express identity and group membership, they also function as advertisements and thus serve visibility enhancing functions and perform the authors’ professional role on Instagram. This is the case with many of the other professional identities mentioned, including the abovementioned travel agencies, as well. Professional identities of the people posted about, for example in the accompanying pictures, are an exception. They included for example #fisherman or #musician.

The other marked identities often referred to as shown in Table 5 are Black identity, female identity and LGBTQ+ identities. These hashtags were additionally marked by using language practices other than English and especially creative hashtags, as outlined in the previous sections. These hashtags emphasize the special and sometimes minority status of these groups, at least with respect to the international travel community coming to Zanzibar. In contrast, the respective majority groups such as White travelers or men rarely indicate their (unmarked) identities by using specific hashtags (see Table 5). Further, all hashtags, except for #boy, in the category “boys and men” refer to LGBTQ+ identity as well. Examples are #gayboy and #gayguy. These seem to relate to, as mentioned in General Patterns, communities of the imagination, characterized by a strong sense of belonging or in-group membership (Wenger, 1998), and thus a marked identity. This might be one of the reasons why other language practices than English are used in the hashtags creating these communities. For people from majority groups it seems to be less relevant to express their group membership, or they indicate membership in the larger tourist community (a majority group) and affinity space less closely connected than communities of the imagination (Gee, 2005; King, 2019).

What has been shown in this section is that besides indirect means of indicating identity, i.e. using particular language practices or linguistic creativity as outlined earlier in Linguistic Patterns, there is also the direct means of indicating one’s identity by stating it in a hashtag. Neither of these means occur in isolation, they are usually combined in order for the poster to construct and perform their identity. One of the most characteristic examples of this is (4) above. The fact that all identities indicated in the examples provided here are multilayered, as illustrated for instance in (4) where Black and female identity are simultaneously invoked or in hashtags such as #gayboy where male and LGBTQ+ identities are indicated, supports previous accounts of complex identities online (e.g., Leppänen et al., 2020). It seems indeed as if roles can be mixed and matched (Turkle, 1995) in the online tourist space of Zanzibar (an affinity space), drawing on different social roles and groups (such as communities of the imagination) one feels affiliated with. The fact that many Instagrammers in the data invoked an identity as travelers also stresses that identities are temporary interactional positions (Bucholtz and Hall, 2005). The idea of traveling and the traveler inherently refer to temporariness and liminality (Mohr, 2020), as they can only be invoked in contrast to the notions of home and the people staying there. These identities are hence inherently temporary and fluid. Exceptions from this rule are the professional identities (of hosts) indicated by the hashtags, as well as the minority group affiliations mentioned above. Thus, the aforementioned Blackvoyageurs invoked their Black identity repeatedly, as did one Instagrammer from the LGBTQ+ community, using hashtags such as #gay and #gayman in all of their posts that form part of this data set. Membership in minority groups and expressing this clearly hence seems to be so central to their members that they constitute a relatively stable part of their performed identities online, even in a liminal space such as the tourist space.

Conclusion

The aim of this article was to provide insight into language choices and use in the digital tourist space of Zanzibar, with a special focus on identity construction through language. To this end, geotagged Instagram data was analyzed, using hashtags as a framework of analysis given their unique (meta)discursive functions. Hashtags and geotags provide a recent angle of analysis in the study of Englishes, moving away from theoretical and methodological nationalism (Schneider, 2019) and focusing more on the creation of space in line with a sociolinguistics of globalization (Blommaert, 2010). Furthermore, correlating the data from the digital space with results from previous studies on the physical tourist space of Zanzibar provided insights into the nexus of offline and online communication, which is typical of contemporary communicative patterns (Blommaert, 2017). The results illustrate the polycentricity of communicative norms, amounting to invisible normativity (Hill, 1998; Blommaert, 2017), in a transnational social space. This is similar to what has been reported for the physical tourist space (Mohr, 2019; Mohr, 2020) and hence emphasizes the close connection between offline and online communication. The results also demonstrate the complexity of social spaces online, where various actors perform various identities, thus contributing to a loosely bound affinity space with different sub-groups or communities of the imagination with their own distinct linguistic practices (King, 2019).

The analysis reveals both similarities and differences concerning language choices and use in the digital as compared to the physical tourist space of Zanzibar. The absence of fully fledged Kiswahili is one of the most striking similarities. Thus, only a negligible percentage of the hashtags analyzed here were in Kiswahili, and the number of posts in Kiswahili was even lower. Much of the little Kiswahili that can be found is Hakuna Matata Swahili (Nassenstein, 2019), employed by tourists to signal their insider knowledge of Zanzibar and Zanzibari culture and supposedly to create an authentic space. This, however, actually demonstrates their lack of in depth linguistic and cultural knowledge. Kiswahili seems to fulfil an exoticizing function that is typical of indigenous languages in holiday locations and that has also been found in the physical Zanzibari tourist space. The use of HMS also expresses a laid-back attitude that many, specifically tourists in Zanzibar, are eager to invoke (Mohr, 2020). This is emphasized by the ludic linguistic tendencies in Kiswahili/HMS and especially English, that creatively make use of various semiotic means such as word formation patterns, typesetting and song (in videos), also observed in the data and typical of tourism discourse (Dann, 1996). The type of space that is constructed via the discourse is similar to the cartoonish imaginaries observed in the physical tourist space (Mohr, 2019; Mohr, 2020). These practices in particular are similar to Hill’s (1998) findings on Mock Spanish and invisible normativity in that Kiswahili proper seems very much ignored, while cartoonish images of it are invoked and popular. In the Zanzibari tourist space, it seems to be the status as tourist and service-receiver, as well as host and service-provider that is the determining force concerning this particular language practice.

Transnational spatial patterns are created through language and specifically different language practices. In general, other language practices than English are rarer than in the physical tourist space where they are present in multilingual greetings specifically, making English less of a “multilingua franca” in hashtags online (Jenkins, 2015). This might be due to the functions of hashtags: to connect with the (international) tourist community and be visible, users employ hashtags that have been previously used or are likely to be found because they are in a language globally spoken. English is the hypercentral language of the world (de Swaan, 2002) and hence a good choice in order to be visible and increase one’s number of followers. Interestingly, choosing other language practices for hashtags (and posts) seems to express an identity relating to worldly tourists then, especially where French is concerned in some in-groups. Both the choice of other language practices and ludic tendencies were shown to be crucial for indicating membership in certain minority groups. Overall, deliberate language choices serve to index identity and (dis)affiliation in a diverse online space, emphasizing the need for investigations of speaker styles at the micro level in third wave sociolinguistics (see Eckert, 2012).

The combination of more indirect indexing of identities and social roles via language choices and particular linguistic structures as outlined above with direct indexing of identities through specific themes in hashtags shows that contemporary identities are multifaceted (Leppänen et al., 2020). The data further showed that identities in tourist spaces are indeed temporary interactional positions that can and will be abandoned after a relatively short time (Bucholtz and Hall, 2005). Minority group membership seems to be an exception, however. In this case, online identities seem to be an extension of offline identities, which further emphasizes the different character of these groups as compared to the much more loosely connected tourist space in general. Importantly, both more liminal and more stable identities in the context investigated here seem local and global at the same time (Leppänen et al., 2020) and this is one of the most interesting aspects of the nexus of offline and online identities in contemporary communication.

While the results presented here are interesting and could only be retrieved with the methods applied in this study, these had some weaknesses, as outlined in detail in Methods and Data. One issue that has not been addressed at length is the question as to who participates in the tourist space as it was analyzed here, i.e., who posts about Zanzibar on Instagram. As shown in the analysis, this includes people who were not in Zanzibar at the time of posting on Instagram. However, these were often representatives of large companies. One of my key participants from Zanzibar said that “Tour operators dont have skills of promoting through social media […] They are few tour operators who use social media mainly facebook to attract DOMESTIC TOURISM rather than international tourists”.6 Thus, language choices and language use as observed in this data set seem skewed towards the tourist side of the tourist space, with hardly any local and smaller businesses participating. However, in the physical tourist space, they are a crucial part of the tourist sector (Mohr, 2021) and they should also be represented in studies of the digital tourist space. With the methods applied here, i.e., the API and subsequent observation, most hosts are relatively large and often international companies run by immigrants. In order to adequately account for smaller businesses, data from other social networks, especially Facebook, should hence be considered. Data collection to this end is currently being carried out.

The present article was the first based on the current data set and aimed at providing a preliminary insight into language practices in the digital Zanzibari tourist space. Hence, it only considered hashtags and only from 2019 for analysis. This leaves several avenues for future research unexplored, among them an analysis of hashtags from 2020, which are also part of the larger data set, and a more comprehensive analysis of all components of the Instagram posts, including pictorial material. Especially the posts from 2020 and after the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic will be an interesting basis for research into mobile language practices during a time of forced immobility and lack of travel. Analyzing speaker styles during these turbulent yet still times will certainly contribute to the study of language use and contact irrespective of national boundaries, and in the spirit of a sociolinguistics of globalization and transnationalism.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusion of this article will be made available by the author, within the constraints imposed by ethical considerations.

Ethics Statement

The data used in this article were anonymized to protect the privacy of the individuals concerned. Images could not be included for ethical reasons.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Funding

This research was partly supported by a Feodor Lynen return fellowship from the Alexander von Humboldt foundation and by a fellowship from the Africa Multiple Cluster of Excellence at the University of Bayreuth, funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) under Germany’s Excellence Strategy–EXC 2052/1–390713894.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

I am indebted to all Instagrammers whose data I was able to use. I especially want to thank Abdulsatar Ali Mohammed for discussing social media usage among Zanzibaris with me. I am also thankful to Anastasia Bauer for support with the Russian part of my data. Two reviewers, who provided critical and inspiring comments on an earlier version of this article, also deserve my gratitude.

Footnotes

1While there are fewer languages indigenously spoken in Zanzibar as compared to mainland Tanzania, especially work migration from the mainland and other parts of East Africa increases the linguistic diversity on the archipelago (Mohr, 2020).

2There was a break in March 2020 due to the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic.

3A few hashtags have been deleted from this example in order to protect the Instagrammers privacy. This is indicated by […].

4While word clouds might not be a frequently employed method of visualization in academic papers, it was chosen here due to its quick readability and because it nicely captures the character of the data analyzed in this article, i.e., the playfulness of Instagram posts.

5This was also mentioned by one of my participants for an earlier part of this study (see Mohr, 2020), who maintained that “people don’t run around with flags on their heads,” thus emphasizing that in the tourist space, nationality does not or should not matter.

6Quoted with permission from a WhatsApp conversation in June 2021.

References

Al Zidjali, N. (2019). Society in Digital Contexts: New Modes of Identity and Community Construction. Multilingua 38 (4), 357–375.

Androutsopoulos, J. (2014). “Computer-mediated Communication and Linguistic Landscapes,” in Research Methods in Sociolinguistics: A Practical Guide. Editors J. Holmes, and K. Hazen (Oxford: Wiley), 74–90.

Androutsopoulos, J. (2008). Potentials and Limitations of Discourse-Centred Online Ethnography. Language@internet 5, article 8, https://www.languageatinternet.org/articles/2008/1610 (retrieved on August 9, 2019).

Barton, D., and Lee, C. (2013). Language Online. Investigating Digital Texts and Practices. London: Routledge.

Benor, S. B. (2010). Ethnolinguistic Repertoire: Shifting the Analytic Focus in Language and Ethnicity1. J. Sociolinguistics 14 (2), 159–183. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9841.2010.00440.x

Blommaert, J., and Backus, A. (2011). Repertoires Revisited: ‘Knowing Language’ in Superdiversity. Working Pap. Urban Lang. Literacies 67, 1–26.

Blommaert, J. (2017). Durkheim and the Internet. On Sociolinguistics and Social Imagination. London: Bloomsbury.

Bolander, B. (2020). “World Englishes and Transnationalism,” in The Cambridge Handbook of World Englishes. Editors D. Schreier, M. Hundt, and E. W. Schneider (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 676–701.

Bucholtz, M., and Hall, K. (2005). Identity and Interaction: A Sociocultural Linguistic Approach. Discourse Stud. 7 (4-5), 584–614. doi:10.1177/1461445605054407

Canagarajah, S. (2020). Transnational Work, Translingual Practices, and Interactional Sociolinguistics. J. Sociolinguistics 24 (5), 555–573. doi:10.1111/josl.12440

Chong, C. X. J. (2020). Glossy Girls, Calm Girls and Grown-Up Girls: Comparing the Stylistic Practices of Young Singaporeans on Instagram (Singapore: National University of Singapore). BA Honours Thesis.

Dann, G. M. S. (1996). The Language of Tourism. A Sociolinguistic Perspective. Oxon: CAB International.

Eberhard, D. M., Simons, G. F., and Fennig, C. D. (2021). Ethnologue: Languages of the World. Twenty-Fourth Edition. Dallas, TX: SIL International. Available at: http://www.ethnologue.com (Accessed August 17, 2021).

Eckert, P. (2012). Three Waves of Variation Study: The Emergence of Meaning in the Study of Sociolinguistic Variation. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 41, 87–100. doi:10.1146/annurev-anthro-092611-145828

Friedrich, P., and Diniz de Figueiredo, E. (2016). The Sociolinguistics of Digital Englishes. Oxon and New York: Routledge.

Gee, J. P. (2005). “Semiotic Social Spaces and Affinity Spaces: from the Age of Mythology to Today's Schools,” in Beyond Communities of Practice. Editors D. Barton, and K. Tusting (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 214–232. doi:10.1017/cbo9780511610554.012

Herring, S. C. (1996). Computer-Mediated Communication: Linguistic, Social, and Cross-Cultural Perspectives. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Heyd, T. (2016). “Global Varieties of English Gone Digital: Orthographic and Semantic Variation in Digital Nigerian Pidgin,” in English in Computer-Mediated Communication: Variation, Representation, and Meaning. Editor L. Squires (Berlin: De Gruyter), 101–122. doi:10.1515/9783110490817-006

Hiippala, T., Hausmann, A., Tenkanen, H., and Toivonen, T. (2019). Exploring the Linguistic Landscape of Geotagged Social media Content in Urban Environments. Digital Scholarship in the Humanities 34 (2), 290–309. doi:10.1093/llc/fqy049

Hill, J. H. (1998). Language, Race, and White Public Space. Am. Anthropologist 100 (3), 680–689. doi:10.1525/aa.1998.100.3.680

Hollington, A., and Nassenstein, N. (2015). “Youth Language Practices in Africa as Creative Manifestations of Fluid Repertoires and Markers of Speakers’ Social Identity,” in Youth Language Practices in Africa and beyond. Editors N. Nassenstein, and A. Hollington (Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter Mouton), 1–22.

Jenkins, J. (2015). Repositioning English and Multilingualism in English as a Lingua Franca. English Pract. 2 (3), 49–85. doi:10.1515/eip-2015-0003

King, B. W. (2019). Communities of Practice in Language Research. A Critical Introduction. London: Routledge.

Kubota, R. (2018). Unpacking Research and Practice in World Englishes and Second Language Acquisition. World Englishes 37 (1), 93–105. doi:10.1111/weng.12305

Leppänen, S., Kytölä, S., Westinen, E., and Peuronen, S. (2020). “Introduction. Social media Discourse, (Dis)identifications and Diversities,” in Social Media Discourse, (Dis)Identifications and Diversities. Editors S. Leppänen, E. Westinen, and S. Kytölä (Oxon and New York: Routledge), 1–35.

Leppänen, S., Møller, J. S., Nørreby, T. R., Stæhr, A., and amd Kytölä, S. (2015). Authenticity, Normativity and Social media. Discourse, Context and Media 8, 1–5. doi:10.1016/j.dcm.2015.05.008

Lett, J. (1989). “Epilogue,” in Hosts and Guests: The Anthropology of Tourism. Editor V. L. Smith (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press), 275–279.

Lim, L. (2020). “The Contribution of Language Contact to the Emergence of World Englishes,” in The Cambridge Handbook of World Englishes. Editors D. Schreier, M. Hundt, and E. W. Schneider (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 72–98.

Mair, Christian. (2020). “World Englishes in Cyberspace,” in The Cambridge Handbook of World Englishes. Editors D. Schreier, M. Hundt, and E. W. Schneider (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 360–383.

Mair, C. (2018). “When All Englishes Are Everywhere: Media Globalization and its Implications for Corpus Linguistics and World English Studies,” in Anglistentag Regensburg (2017): Proceedings (XXXIX). Editors A.-J. Zwierlein, J. Petzold, K. Boehm, and M. Decker (Trier: Wissenschaftlicher Verlag Trier), 65–72.

Meierkord, C., and Schneider, E. W. (Editors) (2021). World Englishes at the Grassroots (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press).

Mohr, S. (2019). Assembling Concourse Material and Selecting Q-Samples on the Sociolinguistics of Tourism Discourse in Zanzibar. Operant Subjectivity 41 (1), 65–82. doi:10.15133/j.os.2019.005

Mohr, S. (2021). “English Language Learning Trajectories Among Zanzibaris Working in Tourism,” in World Englishes at the Grassroots. Editors C. Meierkord, and E. W. Schneider (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press), 70–90. doi:10.3366/edinburgh/9781474467551.003.0004

Mohr, S. (2020). Language Choices Among South African Migrants in the Tourist Space of Zanzibar. South. Afr. Linguistics Appl. Lang. Stud. 38 (1), 60–72. doi:10.2989/16073614.2020.1750966

Mohr, S. (2022). Nominal Pluralization and Countability in African Varieties of English. Oxon and New York: Routledge.

Nassenstein, N. (2019). “The Hakuna Matata Swahili: Linguistic Souvenirs from the Kenyan Coast,” in In Language and Tourism in Postcolonial Settings. Editors A. Mietzner, and A. Storch (Bristol: Channel View), 130–156. doi:10.21832/9781845416799-010

Onysko, A. (2021). “Where Are WEs Heading to? An Introduction to the Inaugural Volume of Bloomsbury Advances in World Englishes,” in Research Developments in World Englishes. Editor A. Onysko (London: Bloomsbury), 1–10.

Page, R. (2012). The Linguistics of Self-Branding and Micro-celebrity in Twitter: The Role of Hashtags. Discourse Commun. 6 (2), 181–201. doi:10.1177/1750481312437441

QSR International Pty Ltd (2020). NVivo. Available at: https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home (released in March, 2020).

Røyneland, U. (2020). “Regional Varieties in Norway Revisited,” in Intermediate Language Varieties: Koinai and Regional Standards in Europe. Editors M. Cerruti, and S. Tsiplakou (Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins), 31–54.

Salazar, N. B. (2006). Touristifying Tanzania. Ann. Tourism Res. 33 (3), 833–852. doi:10.1016/j.annals.2006.03.017

Saraceni, M., and Jacob, C. (2021). “Decolonizing (World) Englishes,” in Research Developments in World Englishes. Editor A. Onysko (London: Bloomsbury), 11–28. doi:10.5040/9781350167087.ch-002

Schmied, J. (2008). “East African English (Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania): Phonology,” in Varieties of English. Africa, South and Southeast Asia. Editor R. Mesthrie (Berlin: Mouton de Guyter), 150–163.

Schneider, B. (2019). Methodological Nationalism in Linguistics. Lang. Sci. 76, 101169. doi:10.1016/j.langsci.2018.05.006

Shakir, M., and Deuber, D. (2019). A Multidimensional Analysis of Pakistani and U.S. English Blogs and Columns. Eww 40 (1), 1–23. doi:10.1075/eww.00020.sha

Sykes, J. M. (2019). Emergent Digital Discourses: What Can We Learn from Hashtags and Digital Games to Expand Learners' Second Language Repertoire. Ann. Rev. Appl. Linguist 39, 128–145. doi:10.1017/s0267190519000138

Tannen, D., and Trester, A. M. (Editors) (2013). Discourse 2.0. Language and New Media (Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press).

Thurlow, C., and Jaroski, V. (2020). “"Emoji Invasion": The Semiotic Ideologies of Language Endangerment in Multilingual News Discourse,” in Visualizing Digital Discourse. Editors C. Thurlow, C. Dürscheid, and F. Diémoz (Berlin & Boston: De Gruyter Mouton), 45–64. doi:10.1515/9781501510113-003

Thurlow, C., and Jaworski, A. (2011). “Banal Globalization? Embodied Actions and Mediated Practices in Tourists' Online Photo Sharing,” in Digital Discourse. Language in the New Media. Editors C. Thurlow, and K. Mroczek (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 220–250. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199795437.003.0011

Thurlow, C., and Jaworski, A. (2017). Introducing Elite Discourse: The Rhetorics of Status, Privilege, and Power. Social Semiotics 27 (3), 243–254. doi:10.1080/10350330.2017.1301789