95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Commun. , 31 January 2022

Sec. Psychology of Language

Volume 6 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomm.2021.777569

This article is part of the Research Topic Englishes in a Globalized World: Exploring Contact Effects on Other Languages View all 17 articles

This paper presents a variational pragmatic analysis of multilingual question tags in Nigerian English, combining a corpus-pragmatic analysis of the Nigerian component of the International Corpus of English with a survey study on the preferences and attitudes of Nigerian students toward different question tag forms. The corpus study highlights multilingual pragmatic variation in terms of form and function of variant as well as English and non-English (i.e., derived from indigenous Nigerian languages) invariant question tags in six text types: conversations, phonecalls, classroom lessons, broadcast discussions, broadcast interviews, and legal cross-examinations. Nigerian speakers combine a wide range of English and non-English invariant forms, whereas variant question tags only play a marginal role and are not characteristic of Nigerian English. Text type influences the overall frequency of question tags and – together with the pragmatic function – constrains the use of individual forms. The survey study shows diverging results as the participants generally prefer variant over invariant question tags and show a strong dispreference for indigenous Nigerian forms when speaking English. Nevertheless, their preferences for specific forms over others are guided by the communicative setting and requirements of a given situation. The students also hold most positive attitudes toward variant question tags, while non-English tags are rated less positively on items reflecting decency. However, all question tag forms are valued in terms expressiveness. Hence, Nigerian students’ dispositions toward multilingual question tag use are guided by a prescriptive ideology that is biased toward canonized English forms. While indigenous Nigerian forms are well integrated into question tag use, indicating a high degree of nativization of Nigerian English at a pragmatic level, acceptance for these local forms is lagging behind. In general methodological terms, the paper shows that question tags – or discourse-pragmatic-features in general – have high potential for studying multilingual variation in New Englishes. However, studies on the multilingual pragmatics of New Englishes need to consider the full range of multilingual forms, take into account variety-internal variation via text type, and should ideally also study the users’ perspectives.

The World Englishes paradigm has pushed the decolonization of the academic study of the English language by highlighting the global diversity of the English language along different national Englishes (e.g., Kachru, 1985). Much research in this area has focused on New Englishes, which are varieties of English that have developed out of colonial contact situations. New Englishes are used in countries where English serves an official function but is usually learned as a second/subsequent language (or dialect). The notion of New Englishes was first used to describe emerging national standard varieties (Platt et al., 1984), such as Indian or Nigerian English, but may also include English-based creoles (Mufwene, 1994) or hybrid Englishes (Schneider, 2016). All of these different types of New Englishes exist in highly multilingual ecologies and monolingualism is most often the marked case. For example (Anderson and Ansah, 2015: 60), describe code-switching as so pervasive in many domains of language use in West Africa that it has become the norm rather than an act of identity. Consequently, the development of Standard New Englishes, which emerge in such multilingual environments and are not fully codified, can be assumed to be strongly affected by other languages and dialects.

A case in point is Nigerian English, the emerging Standard English of Nigeria (Schneider E., 2007: 199–212). Nigeria is located in West Africa and is home to more than 140 million inhabitants from diverse ethnic groups who also speak various languages/dialects (Jowitt, 2019: 4–5). As the distinction between language and dialect is very complex, estimations range from around 400 to more than 500 languages in Nigeria. The three major ethnic groups and their first language are Hausa, Yoruba, and Igbo, which are recognized officially alongside English. English is mainly learned as a second/subsequent language and functions as an interethnic lingua franca in many formal domains, such as the government or higher education. Nigerian English is not a monolithic fixed norm but exhibits a high degree of variation, for example in terms of ethnicity or the level of education of speakers (Jowitt, 2019: 24–33). In addition to the different first languages, Nigerian English is also influenced by Nigerian Pidgin, an English-based contact language that is mainly used as a lingua franca in informal domains, such as on the market or in public transportation (Deuber, 2005). The distinction between these two varieties is increasingly blurred as there is mutual borrowing and Pidgin has been making inroads into domains formerly reserved for Nigerian English, such as the media (Schneider E., 2007: 207–209). In support of the codification of Nigerian English (Gut, 2012), many studies on this variety have focused on describing its grammatical (e.g., Gut and Fuchs, 2013), phonetic (e.g., Oyebola et al., 2019), and pragmatic (e.g., Unuabonah and Gut, 2018) properties. Much of the most recent research on Nigerian English has used the Nigerian component of the International Corpus of English (ICE) (Wunder et al., 2010).

The ICE project (Greenbaum and Nelson, 1996) includes national corpora of Standard Englishes from countries where English has an official status. Each corpus has a size of one million words and has the same design, covering 15 spoken and 13 written text types. Hence the ICE corpora are a rich tool for analyzing variation across and within World Englishes and has been used extensively (e.g., Hundt and Gut, 2012). The ICE corpora are designed to represent Standard English exclusively, which means that multilingual/-dialectal variation is often suppressed in the compilation process. This bias toward monolithic standard language ensures comparability across corpora but fails to depict the actual multilingual embedding of Standard New Englishes. Hence (Mair, 2011: 234), states that the failure to recognize the embedding of New Englishes in intensely multilingual communities is the most “glaring lacuna” in corpus-based research on New Englishes and he argues for the compilation of multilingual corpora. However, recent corpus-pragmatic research has demonstrated the presence of many ‘non-English’ discourse-pragmatic-features (i.e., syntactically optional particles used to express stance, to guide utterance interpretation, or to structure the discourse; Pichler, 2013: 4) in ICE-Nigeria, such as abi, o, or sha (e.g., Unuabonah and Oladipupo, 2018). Hence, discourse-pragmatic-features seem to be a promising area to analyze multilingual variation in New Englishes.

In this paper, I highlight multilingual variation in Nigerian English by analyzing the use and perception of question tags, which I treat as a set of discourse-pragmatic-features that includes English (e.g., isn’t it, right) and non-English/indigenous Nigerian forms (e.g., abi, o). On the one hand, I analyze the use of question tags in ICE-Nigeria, demonstrating that the ICE corpora can be used to study multilingual variation in New Englishes. This corpus-pragmatic analysis highlights internal variability in Nigerian English by investigating the use of multilingual question tags across six dialogic text types: conversations, phonecalls, classroom lessons, broadcast discussions, broadcast interviews, and legal cross-examinations. On the other hand, I investigate Nigerian students’ perception of multilingual variation of question tag use in a survey study. The survey includes a multiple-choice task, in which the participants indicate which question tag form they prefer in different situations, and a written Matched-Guise-Test, in which the participants rate the use of different question tag forms on attitudinal scales. With this mixed-methods approach, I address the following research questions:

• Which question tag forms do Nigerian speakers use when speaking English?

• How does text type influence the overall distribution of question tag forms?

• How do text type and function constrain the selection of particular forms over others?

• Which question tag forms do Nigerians prefer in different situations?

• Which attitudes do Nigerians hold toward different question tag forms?

This paper makes an important contribution to the description of Nigerian English and highlights new methodological paths to using the ICE. I also present new methods to analyze speakers’ perception of discourse-pragmatic-features. On a theoretical level, the paper merges a fundamental assumption of sociolinguistics with multilingualism in World Englishes. Thus, I argue that the structure of New Englishes can only be understood by illustrating their internal variation, which in large parts is caused by their multilingual embedding. Question tags are used as a case in point to illustrate the structure of multilingual variation in Nigerian English.

The paper is structured as follows. Section 2 discusses previous variational-pragmatic research on World Englishes, focusing on previous studies on question tags. In Section 3, I present the methods of the corpus-pragmatic and the survey study. The findings of these two studies are presented in Sections 4 and 5. Section 6 discusses these findings and highlights the methodological implications for research on multilingual variation in New Englishes.

Most descriptive (Kortmann and Schneider, 2008) and comparative work (e.g., Hundt and Gut, 2012; Siemund, 2013) in World Englishes has focused on morpho-syntax, lexicon, and phonetics. ICE-based research has largely focused on the first two levels of variation, but newer ICE corpora also allow studying phonetics (e.g., Oyebola et al., 2019). The results of ICE-based research on New Englishes are mostly compared to Englishes spoken as a native language, mainly British English, to delineate their level of nativization based on the degree of difference. See (Hansen, 2018: 48–54) for a critical discussion of this approach.

Pragmatic phenomena, including discourse-pragmatic-features, have been studied less frequently. Traditionally, they are not used as indicators of nativization. Instead their use is ascribed to idiosyncratic preferences. For example (Bautista, 2011: 81), describes the use of ‘no by Filipino teachers as a verbal tick of some speakers. Aijmer (2013: 145) explains the use of discourse-pragmatic-features by speakers of New Englishes as a result of their lower competence in English. In his overview of African Englishes (Mesthrie, 2008: 30), dismisses invariant question tags as “garden-variety” structures of New Englishes.

Pragmatics, as the study of language in context, mirrors the research gap in World Englishes as regional and social variation has been neglected. Schneider (2012: 464) illustrates that pragmatics was initially concerned with establishing seemingly universal theories of speech acts, politeness, or the structure of conversation, but conventions in and across particular languages/varieties did not play a role. The discipline of variational pragmatics (Schneider and Barron, 2008) fills this research gap by investigating pragmatic variation with regard to region and other macro- (e.g., social class) or micro-sociolinguistic (e.g., power) factors. Variational pragmatics mostly draws on corpus or survey data. Corpus-pragmatic analyses often combine qualitative coding of individual pragmatic phenomena (i.e., horizontal reading of corpus texts) with quantification (i.e., vertical reading of corpus texts) (Aijmer and Rühlemann, 2015: 3–9). In addition, research on speech acts in different varieties has shown the benefits of combining analyses of language use with survey data (e.g., Schneider K. P., 2007). Besides speech acts, the pragmatic phenomena most often studied in this field of research are discourse-pragmatic-features. However, there has been a strong focus on English varieties spoken as a native language, such as British English (e.g., Pichler, 2013; Beeching, 2016). In addition, corpus analyses of discourse-pragmatic-features have mainly focused on face-to-face conversation, while other text types have been neglected. Moreover, there are hardly any studies on discourse-pragmatic-features that have utilized survey data; an exception is Beeching (2016). Survey data in general is rare for studying pragmatic phenomena in New Englishes; exceptions include Schröder and Schneider (2018) and Anchimbe (2018).

If discourse-pragmatic-features are studied in New Englishes, for example in Nigerian English, the full range of multilingual variation for these pragmatic phenomena is not considered. On the one hand, research focuses on individual ‘non-English’ forms, which derive from Hausa, Igbo, or Yoruba and are integrated into Nigerian English – often via Nigerian Pidgin. Unuabonah and Oladipupo (2018) investigate abi, o, and sha, Unuabonah and Oladipupo (2021) analyze jare, biko, jor, shebi, shey, and fa, and Unuabonah (2020) examines na wa, shikena, ehn, and ehen. There are also studies on indigenized uses of English forms. Oladipupo and Unuabonah (2021) analyze the particle now in Nigerian English. All these studies use ICE-Nigeria, show the general frequencies of these forms, and list their different pragmatic functions. However, they do not investigate the sociolinguistic dynamics of pragmatic variation, for example by analyzing the constraints of use of the different discourse-pragmatic-features (e.g., text type, age, or gender). In addition, the local discourse-pragmatic-features are not analyzed in relation to alternative English forms which may fulfill similar pragmatic functions.

If entire sets of discourse-pragmatic-features are studied, then the focus is on English forms and their use is compared to British English. Unuabonah and Gut (2018) investigate 173 commentary pragmatic markers, Unuabonah (2019) analyzes 71 discourse markers, and Unuabonah et al. (2021) examine the 64 intensifiers in ICE-Nigeria. The concordance lists of discourse-pragmatic-features are based on previous research on English varieties spoken as a native language and do not include non-English forms. These studies generally conclude that Nigerian English shows an overall lower frequency of the selected discourse-pragmatic-features but there are distinct patterns of use. According to these studies, speakers of Nigerian English use a reduced inventory of discourse-pragmatic-features and demonstrate a lower stylistic variability in comparison to British English. These conclusions seem somewhat biased as indigenous forms are not included. Despite this already large and still growing body of research on the pragmatics of Nigerian English, there is the need to investigate multilingual variation for an entire set of discourse-pragmatic-features that includes English and non-English forms and considers constraints of variation (e.g., text type). This approach allows expanding the understanding of the structure of Nigerian English and by extension of New Englishes in terms of the dynamics of multilingual variation.

Question tags are one set of discourse-pragmatic-features frequently studied in World Englishes. There is a wide range of forms that can function as question tags and hence they are not defined by their form but by their function. In most general terms, speakers append question tags to statements to receive a confirmation from their interlocutors, to integrate other participants in the conversations, or to emphasize their statements (Wilson et al., 2017: 732–734; Kimps, 2018: 14–27). In terms of forms there is a major distinction between variant (also called canonical) and invariant question tags. Grammars (e.g., Biber et al., 1999: 208–210) mostly focus on the formal properties of variant question tags, whose structure depends on the main clause they are attached to.

Variant question tags consist of a pronoun and an auxiliary verb, which is identical to the one in the main clause 1); if there is no auxiliary verb in the main clause, do is used 2). The main clause and the question tag also agree in terms of tense, aspect, and mood (1–2). However, the use of these forms often does not align with these rules. For example, many speakers commonly use invariant isn’t it 3). Canonical question tag constructions are a typological anomaly, which is typical for English and only found in few other languages (see Axelsson, 2011: 823–829).

1) <#>But I should take it again <#>But I wasn’t dictating was I (les_13)

2) <#>You like it don’t you (con_09)

3) <#>We’ll be selling them for six thousand isn’t it (ph_01)

Invariant question tags have a fixed form that does not depend on the main clause to which they are attached, and they are not discussed in much detail in grammars (e.g., Biber et al., 1999: 1,089). Invariant question tags may be single words or particles, such as right or eh, as well as multi-word units, such as you know (4–6).

4) <#>It’s not like as if he’s the Messiah right (con_09)

5) <#>Is no is no good kuli it was not the good one eh (con_45)

6) <#>He just cannot condone such hypocrisy you know (ph_01)

In addition to such English forms, invariant question tags also include forms borrowed from indigenous Nigerian languages, such as sha or abi (7–8), which are mainly used to add emphasis in these two examples.

7) <#>No I don’t really like chilled water sha (con_36)

8) <#>Philosophy is not maths at all abi (con_50)

Previous research on question tags in World Englishes exhibits several gaps. The overwhelming amount of studies on question tags has been done for Englishes spoken as a native language (e.g., Tottie and Hoffmann, 2006; Gómez González, 2018) and there is a dearth of research on other text types than conversations (see Barron, 2015: 224). Furthermore, most research has focused on variant question tags exclusively. For example, Borlongan (2008), Parviainen (2016), and Hoffmann et al. (2017) analyze variant question tags in Asian Englishes comparing them to British (and American) English. All three studies find a very high number of invariant uses of isn’t it, is it, or is it not and they conclude that these invariant uses are characteristic for Asian Englishes. However, this conclusion seems biased as invariant question tags were not considered. A notable exception is Columbus (2009, 2010), who studies invariant question tags across several Englishes and shows that specific question tag forms are often typical for individual varieties, such as na for Indian English or eh for New Zealand English. She also illustrates that a wide range of forms which are often not included in analyses and descriptions of question tags are highly frequent across varieties, such as OK, yeah, you know, or you see. Similarly, Takahashi (2014) shows that speakers of Asian Englishes combine various English and indigenous question tag forms. Research on discourse-pragmatic-features in Singaporean English and Singlish (see Leimgruber, 2013: 84–96), such as ah, meh, or lah, does not discuss these forms as question tags nor in relation to English alternatives.

Gómez González (2018) investigates both types of question tags in British English, showing that variant ones are five times as frequent as invariant ones. In contrast, recent research on New Englishes (Wilson et al., 2017; Mbakop, 2020; Westphal, 2020) has shown that invariant question tags outnumber variant ones by far. These studies have also demonstrated that the use of isn’t it is rare. In their analyses of Trinidadian and Philippine English, respectively, Wilson et al. (2017) and Westphal (2020) also show that text type exerts a strong influence on the general frequency of question tags and on individual forms. For example, non-English forms in New Englishes are more common in informal text types, or OK is most commonly used in classroom lessons by teachers. Both studies demonstrate that individual question tags serve specific functions. For example, eh is mainly used to add emphasis and variant question tags are preferentially used to receive confirmation from interlocutors.

Despite this prevalence of invariant forms in New English, there seems to be strong prescriptivism in terms of question tag usage in New Englishes contexts, such as anglophone West Africa. Mbakop (2020: 1) argues that in Cameroon English Language Teaching focuses very strongly on variant question tags, which is in strong contrast with usage patterns of Cameroonian English. One of the sketches of the Ghanaian-American comedian Ebaby Kobby makes fun of the ‘incorrect’ use of question tags among Ghanaian students.1 There are also prescriptive papers on the correct use of question tags in Nigerian English (Osakwe, 2009). Hence, there seems to be a strong standard language ideology which devalues invariant question tags, but so far, no perception study on English question tags has been carried out.

The analysis of the use of question tags in Nigerian English utilizes the spoken component of ICE-Nigeria (Wunder et al., 2010), which was published in 2015 and includes transcriptions and sound files for most texts. Like other ICE-corpora the spoken component has a size of 600,000 words but individual texts vary in size, in contrast to the standardized ICE format of 2,000 words per text. Individual text types have the same subcorpus size as in other ICE-corpora. As question tags are an integral part of spoken dialogues and more common in these text types than in others (e.g., Borlongan, 2008), this corpus-pragmatic study of ICE-Nigeria only uses texts from six dialogue text types: conversations, phonecalls, classroom lessons, broadcast discussions, broadcast interviews, and legal cross-examinations.2 The dialogic subcorpus analyzed in this paper includes 97 texts with an overall size of 233,752 words. Table 1 shows the number of texts and the word count for each text type.

These six text types differ substantially in terms of the communicative setting, which includes the level of formality, the degree of prestructruing of the dialogue, and speakers’ roles in the given discourse. Conversations and phonecalls are private dialogues, they are the least formal, open in terms of their structure, and the interactions are very diverse as speakers do not have fixed roles. This is different to the four public dialogues, which are all more formal, have a higher degree of prestructuring, and speakers fulfill specific roles. In classroom lessons, there is one teacher/lecturer who gives explanations and asks questions to their students. In broadcast discussions and interviews, hosts moderate these public dialogues and guests answer the hosts’ questions, voice their opinion, or debate with each other. Legal cross-examinations are the most formal text types. They are rigidly structured and controlled, as attorneys question witnesses, who have to testify in front of court.

Due to the form-function mismatch of question tags, a top-down concordance analysis was not possible. Searching for a specific form that may function as a question tag produces numerous concordances that are not question tags. For example, right may be used as an adjective (e.g. the right choice), to backchannel, or as a question tag. In addition, relying on a pre-defined list of question tag forms may lead to biased results. There might be many forms that fulfill the function of question tags but are not included in this list and are thus overlooked.

Hence, I read and – if the sound files were available3 – listened to all 97 texts. I identified and coded each question tag token qualitatively. Much previous corpus-based research on question tags has mainly relied on formal criteria to define a question tag. Many studies have analyzed variant question tags exclusively (e.g., Tottie and Hoffmann, 2006; Borlongan, 2008; Barron, 2015; Parviainen, 2016; Hoffmann et al., 2017), while others also allow invariant forms but only focus on sentence-final question tags (e.g., Takahashi, 2014). Instead, I applied a much wider understanding of question tags similar to Columbus (2009, 2010) and tried to capture all forms that may function as a question tag, using function-based criteria to define what counts as a question tag. Pichler (2010, 2013: 28–32) discusses the problems of such an approach for variationist analyses of discourse-pragmatic-features. In the conclusion, I revisit this methodological issue.

For the purpose of the current study, the decision whether a specific form functions as a question tag is grounded on the following criteria. Question tags are discourse-pragmatic-features (i.e., they are syntactically optional), and they are attached to utterances. Question tags are neither fillers (i.e., forms surrounded by repetitions or other fillers, such as uhm, were excluded) nor entire utterances on their own (e.g., right used as a backchannel). Furthermore, they are neither items used in their full literal sense (e.g., the right choice) nor part of fixed expressions (e.g., right now). In cases of repetitions of a question tag in an utterance, only the final form was counted. The main functional criterium is that question tags fulfill an informative, facilitative, or punctuational function. A form was identified as a question tag if it fulfills one of these functions.

Speakers use question tags in an informative way when they are unsure of the content of an utterance, and they want new information or a confirmation for the assumption they have expressed. An answer is expected when question tags are used informatively. In (9), the attorney demands information whether the witness has written a piece of information themselves. Speakers use question tags in a facilitative way to integrate interlocutors more into the discourse either by signaling that they are willing to hand over their turn or to invite (verbal or non-verbal) responses. In (10), a teacher adds OK to their utterance to check whether the students have understood the explanation and invites them to backchannel or to interrupt if there are any uncertainties. Question tags with a punctuational function are used for stylistic purposes, mainly to add emphasis. The speaker is sure about the content of the utterance and mostly no answer is expected. In (11), the speaker uses o to add emphasis to his suggestion to his interlocutors.

9) <#>Did you write it yourself not so (cr_10)

10) <#>This times four is four OK (les_06)

11) <#>You guys should call him before he goes o (con_11)

This tripartite functional distinction is a reduced system of previous functional classifications (e.g., Algeo, 1990; Tottie and Hoffmann, 2006; Wilson et al., 2017). A six-way distinction into confirmatory, facilitating, attitudinal/punctuational, informational, peremptory, and aggressive tags, which is based on Algeo (1990), has been widely used but proved problematic for the Nigerian data. A distinction between informative and confirmatory uses, which is based on different levels of prior knowledge of the speaker (Tottie and Hoffmann, 2006: 299), proved impossible to make. Hence, these two functions were merged to one category, which I labelled informative. Similarly, peremptory and aggressive tags could hardly be distinguished from general attitudinal ones. Thus, these three categories were fused to one, which I labelled punctuational. Tottie and Hoffmann (2006) and Wilson et al. (2017) classify over 90% of their question tags as confirmatory, facilitating, and attitudinal/punctuational. Thus, the current three-way distinction (i.e. facilitative, informative, punctuational) covers the main uses, facilitates coding and allows using function more easily in regression modelling. However, there are also cases in which it was very difficult to clearly distinguish between different pragmatic functions, and as question tags are multifunctional, they sometimes fit into more than one category. In these cases, question tags were ascribed to all the respective functional categories and were coded as multifunctional. In (12), the guest (<$A>) in a broadcast discussion uses you see both to add emphasis to his argument but also invites backchannelling from the host (<$B>) and the other guest, checking whether they are still following his line of argumentation.

12) <$A><#>Let me tell you why we cannot do anything for now you see <$B><#>Mhm (bdis_12)

These codings of the forms and pragmatic functions were used for a quantitative analysis of the use of question tags in the six dialogue text types from ICE-Nigeria. For all statistics on text type variation, conversations and phonecalls were merged to the overarching category of private dialogues. Broadcast discussions and interviews were unified to the single category broadcast dialogues. Normalized frequencies are presented as tokens per fifty thousand words (tpf). The descriptive statistics first describe the general diversity in question tag forms in the subcorpus. Second, I demonstrate the overall frequency distribution of variant vs. invariant question tags across the different text types. Third, I highlight the distribution of the most frequent English and non-English question tag forms across the text types and their functional diversity. I define non-English forms as forms borrowed from indigenous Nigerian languages (as defined in previous research: e.g., Unuabonah and Oladipupo, 2018; Jowitt, 2019; Unuabonah, 2020; Unuabonah et al., 2021).4 English forms may also include local innovative forms unusual for many varieties of English, such as not so or no be.

The inferential statistics then show in detail how text type and function constrain the use of selected question tag forms: o, OK, you know, and variant question tags. These forms were selected as they are sufficiently frequent across the corpus and serve to illustrate different socio-pragmatic profiles of question tags in Nigerian English. For this analysis, I used binary regression models in RBRUL (Johnson, 2009) with form as a dependent variable, which was reduced to a binary distinction. In one model, the use of one form is compared to all others (e.g., o vs. all other forms). Text type (four levels: private dialogues, classroom lessons, broadcast dialogues, legal cross-examinations) and function (three levels: facilitative, informative, punctuational) were used as fixed predictor variables. Speaker was inserted into each model as a random factor to avoid Type I errors as idiosyncratic variation is very pronounced for individual question tag forms (e.g., Wilson et al., 2017: 734). Multifunctional question tags were excluded from the regression analyses. For all binary regressions p-values for the general effect of a factor and centered factor weights for the individual levels are given. Factor weights indicate the direction and size of the effect. They range from 0 to 1; values above 0.5 signal a preference and values below 0.5 a dispreference.

The survey study combines a multiple-choice task, which analyzes the participants’ preferences for different question tag forms in various scenarios, and a written Matched-Guise-Test, which investigates participants’ attitudes to a range of question tag forms.5 The multiple-choice task is modelled after a discourse-completion-task but with fixed answer options. This means that there is a brief description of a dialogue and the participants had to imagine that they are a part of this situation. This communicative scenario is followed by a dialogue, which the participants completed by selecting a question tag form from pre-given options. There are seven scenarios, which are based on corpus data, reflect different text types, speaker roles, and speaker relationships (e.g. teacher-student, attorney-witness). In addition, the scenarios target a specific pragmatic function of question tags (facilitative, informative, punctuational). For each scenario the participants chose from ten different options including non-English forms (abi, o, sha), English forms (eh, OK, variant question tag, invariant isn’t, you know), and the option ‘other’, which participants could fill out freely.

• Scenario 1 is an informal private dialogue between friends and targets an informative question tag.

• In scenario 2, participants imagine that they are a teacher in a classroom lesson and use a question tag facilitatively to check whether students have any questions.

• Scenario 3 depicts a legal cross-examination. Participants imagine they are an attorney eliciting information from a witness using an informative question tag.

• Scenario 4 is an informal private dialogue between friends and requires the use of an informative question tag.

• Scenario 5 is a classroom lesson. Participants assume the role of the teacher adding a punctuational question tag to an imperative targeted at a student.

• Scenario 6 is an informal private dialogue between friends, which targets the use of a facilitative question tag.

• In scenario 7, participants imagine they are a student at university and ask their lecturer for a confirmation of information using a question tag.

The second part of the survey investigates the participants’ attitudes toward the same nine forms given as options in the multiple-choice task, using a modified Matched-Guise-Test with written stimuli, adapted from Beeching (2016: 38–41). The participants were presented with nine scenarios that contain a description of the situation which is typical of the pragmatic profile of the question tag form under investigation as used in ICE-Nigeria. The description is followed by two almost identical utterances produced by two speakers. One contains a question tag and the other does not. The participants were asked to rate the speaker who uses the question tag in contrast to the other speaker on six personality traits, using six-point semantically differential scales (impolite vs. polite; reserved vs. outgoing; aggressive vs. gentle; indirect vs. direct; unfriendly vs. friendly; uneducated vs. educated). Hence, participants’ attitudes toward question tag forms were elicited indirectly (see Garrett, 2010: 39–43). An additional blank space was given, where participants could add their additional thoughts on the use of the specific question tag form.

The descriptive statistics for the multiple-choice task describe the frequencies of selection for each scenario individually. For individual question tag forms, binary regression models were run to highlight how scenario influences the choice of one form over the others. Form was used as the dependent variable (e.g., variant question tag vs. all other options) and scenario (7 levels) was the fixed predictor variable. The descriptive statistics for the Matched-Guise-Test illustrates the ratings of all nine forms on the six scales. Principal Component Analysis was used to investigate how the different items pattern together, illustrating the underlying attitudinal dimensions (Garrett, 2010: 55–56). To illustrate the ratings of the nine question tag forms along the different dimensions, mean values of all items that clustered together were calculated for each participant. These mean values were then used in further regression analyses. Rating scores for the different dimensions were employed as dependent variables and question tag form was used as fixed predictor variable.

University students were selected as the target demographic for the survey. Students might be a convenience sample but as they are generally fluent in English, young, well-educated, and hence part of the future middle-class, they are an important group for the emerging standard variety in Nigeria. Fieldwork was carried out by Folajimi Oyebola at the University of Lagos in January 2020 among 1st year students who participated in the class Use of English in Nigeria. This is a compulsory class students across all disciplines must attend in their first year at the University of Lagos. 49 Nigerian students completed the questionnaire. The larger majority of them is female (32 female; 16 male; 1 no answer) and between 18 and 25 years old (41 18–25; 5 younger than 18; 3 no answer). Of the students who indicated their type of studies (N = 40), the majority studied law (18; 45.0%), followed by ‘English’ (13; 32.5%),6 adult education (7; 17.5%), and educational administration (2; 5.0%). The sample is rather small and does not allow any internal differentiation but gives first insights into the perception of different question tag forms in Nigerian English.

Question tags are a frequent feature in the six dialogue text types of ICE-Nigeria. 1,326 tokens (284.85tpf) were identified in the 97 texts. Nigerian speakers use a wide range of English and non-English forms. Table 2 provides an overview of these different forms. The overall most frequent question tag form is you know followed by now, OK, and o. With only 33 occurrences, variant question tags are marginal. Of these 33 question tags only 15 agree with the main clause they attach to in terms of the auxiliary (or use do in a canonical way), tense, aspect, and mood. Of the 18 invariant uses, 13 occurrences are invariant isn’t it or is it (not) as in (3) and (13), but there are also other invariant uses as in (14).

13) <#>No but you’re talking about the G twenty summit isn’t it (bdis_01)

14) <#>You attended University of Illorin don’t you (con_06)

The speakers of Nigerian English from the subcorpus use a mix of English and non-English forms. 832 tokens (62.7%) were classified as English, while 261 (19.7%) question tags derived from indigenous Nigerian languages or Nigerian Pidgin. The most frequent indigenous forms are o, abi, and sha. Now accounts for 233 question tag occurrences. However, now is a special case as there is variation in spelling between na, ne, and now. The most frequent spelling is now (216), followed by na (13), and ne is least frequent (4). These spellings do not match the variation in pronunciation consistently, which includes [naʊ], [naʊ], [na(ː)], [nə], [næ], and [nɛ], the latter two being very rare. In addition, there is variation in the tonality of now (Oladipupo and Unuabonah, 2021: 375–377). The extended pragmatic uses of now in Nigerian English can be viewed as a result of nativization of the general English pragmatic particle now (Oladipupo and Unuabonah, 2021), however, the Nigerian Pidgin form na might overlap with now (Unuabonah et al., 2021). Whereas previous studies have looked at now and na independently (Oladipupo and Unuabonah, 2021; Unuabonah et al., 2021), a detailed analysis that looks at now, na, and ne is required. In addition, this analysis should also study the exact phonetic realization now and its spelling variants. Due to this complexity of now a separate analysis is needed and now is not discussed further in this paper.

Text type has a strong influence on the frequencies of question tags in the dialogue subcorpus. Figure 1 shows the normalized frequencies of variant and invariant question tags for the four general dialogue text types. Question tags are most frequent in private dialogues closely followed by classroom lessons. In broadcast dialogues, question tags are less than half as frequent as in private dialogues. Question tags are by far the least frequent in legal cross-examinations. Hence, a general correlation with formality becomes apparent. The more formal the text type the fewer question tags are used. Despite this general effect of text type on question tag frequencies, there is also substantial internal variation for text type. This is most pronounced for classroom lessons. For example, in les_11 the teacher does not use any question tag and for les_01 (105.6tpf), les_05 (113.5tpf), and les_07 (127.6tpf) normalized frequencies are very low. In contrast, the teachers in les_06 (454.8), les_03 (770.0tpf), and les_14 (832.1tpf) use a very high frequency of question tags. This variation has to do with the different teaching styles. Teachers with low frequencies of question tags often dictate entire passages to their students, hence these texts have a quasi-written character. Les_05 and les_07 are special cases as these texts are bible classes and all participants read out passages from the bible extensively with very little dialogue between them. In contrast, teachers who use many question tags rely on oral explanations, want to make sure their students are following along, and interact more directly with them. Hence, idiosyncratic variation in terms of question tag use is guided by the exact type of classroom lesson and the pedagogical style of the teacher.

Text type also has a substantial effect on the distribution of individual English and non-English question tags, which is shown in Figure 2. Generally, non-English question tags are mostly used in private dialogues, and they are rare or even completely absent in public and more formal text types. This text type variation is categorical for abi, ba, and sef and very pronounced for o and sha. Ah is an exception as this form seems to be more frequent in classroom lessons and broadcast dialogues than in private dialogues. However, whenever ah is used in these two public text types, teachers/lecturers and guests in broadcast dialogues use ah exclusively in direct speech when imitating opinions of other people – very often views of the average citizen. In (15), a lecturer uses ah in direct speech when imitating common criticism of the statistical modelling she is presenting.

Eh is found across all four text types but there seems to be a slight preference for private dialogues. Eh also seems fairly frequent in legal cross-examinations but the four tokens of eh in this text type are very specific and rather unusual for these very formal interactions as all of them appear in rare antagonistic disputes between attorneys and witnesses (16) is an excerpt from a very heated controversy between an attorney and a witness, which eventually results in an intervention of the police in court who take violent action against the witness. The attorney uses eh to emphasize his verbal attack at the witness. OK is found most commonly in classroom lessons. Teachers frequently use OK in a facilitative way to check whether the students are still following their explanations, have understood everything, or have a question, as in (10) and (17). No right tokens were found for legal cross-examinations, but the distribution across the other three text types is fairly balanced. You know is used across all four text types but is less frequent in legal cross-examinations. The text type distribution of variant question tags seems quite even according to the descriptive statistics.

15) <#>Anybody can say ah this test is not reliable (les_08)

16) <#>I will disgrace you more than that eh (cr_09)

17) <#>And one of the important concepts in discourse analysis is cohesion OK <#>Cohesion and Coherence OK (les_03)

In terms of the functions of question tags, punctuational uses dominate (653; 49.2%) followed by facilitative question tags (452; 34.1%). Only 138 question tags (10.4%) were classified as informative. 83 question tags were coded as multifunctional, which mostly serve a facilitative and punctuational function (74; 5.6%). Question tags that combine an informative with punctuational (5; 0.4%) or facilitative (4; 0.3%) functions are rare. While many question tag forms are used for all three functions, there are preferential differences as some forms have a more focused form-function mapping. Figure 3 shows the functional diversity of the most frequent English and non-English question tag forms; multifunctional tags were excluded.

Ah has the most focused functional profile as it only serves punctuational functions. This functional exclusivity suggests that the classification of ah as a question tag is somewhat problematic as it seems that this form cannot fulfill all functions that are central to the definition of a question tag in this analysis. However, the findings for ah, similar to ba and sef, should be treated with some caution due to the low token frequency. O and sha also have a very focused form-function relationship with a strong preference for punctuational uses. Abi has a slightly more diverse functional profile but is preferentially used informatively. The functional diversity of ba is quite balanced but there is a slight dispreference for punctuational uses. No token of sef was classified as facilitative and there is an almost even distribution between punctuational and informative uses. Eh may fulfill all three functions but punctuational uses clearly dominate. Right has a functional profile that is quite balanced but there is a slight preference for facilitative uses. Both OK and you know have a rather focused functional profile as OK is mainly used facilitatively and you know punctuationally. For variant question tags the descriptive statistics demonstrate a preference for informative uses.

The descriptive statistics and examples have illustrated multilingual variation in question tag forms and the effects of text type on question tag use. In addition, this section has shown the form-function relationship of the most frequent English and non-English question tag forms in a descriptive way. As both text type and function influence which question tag forms Nigerian speakers select in dialogues, a further multivariate inferential analysis is necessary to highlight the details of variation. Further inferential statistics are not possible for question tag forms with a low token frequency or forms that exhibit (almost) categorical variation, i.e., abi, ah, ba, eh, right, sef, and sha.

The regression models demonstrate the effects of text type and function on the selection of o/OK/you know/variant question tags in contrast to all other question tags. These results are shown in Tables 3–6. All forms have a specific functional profile. For o, there is a strong preference for punctuational uses and the Nigerian speakers show a preference for using OK in a facilitative way. You know is preferentially used for punctuational and facilitative functions and there is a strong dispreference for informative uses. In contrast, variant question tags are preferentially selected for informative uses and dispreferred for both other functions.

Text type has a significant effect on the use of o, OK, and you know. However, the results for text type variation are somewhat vulnerable to the low token frequencies in legal cross-examinations. Consequently, these results need to be viewed with some caution despite the use of speaker as a random factor, which helps to prevent Type I errors. As already shown in the descriptive statistics, there is a strong preference for o in private dialogues, while it is dispreferred in classroom lessons and broadcast discussions. Legal cross-examinations demonstrate no tendency. For OK, there is a strong preference for classroom lessons and a somewhat lower preference for legal cross-examinations, while both other text types exhibit a dispreference. For you know, there is a strong preference in broadcast dialogues, no tendency in private dialogues, and a dispreference in classroom lessons and legal cross-examinations.

Hence for most question tags, text type and function together constrain their use. This combination of predictors reflects the communicative needs of speakers in specific situations. O is commonly used in informal conversations among friends to add emphasis to arguments, humorous remarks, or expressions of surprise. O is often used when speakers become emotionally involved in a discussion, as in (18) where a student expresses her anger against certain study regulations.

18) <#>Ah ah god will not allow it o (con_13)

OK is a typical teacher question tag used as a pedagogical strategy in longer explanatory passages to integrate the students into the discourse as already highlighted in (10) and (17). You know is used very frequently by hosts and guests in broadcast discussions to add emphasis to statements and to integrate the other participants into the discussion. In (19), the host talks about interethnic relationships in Nigeria and expresses her joy about a famous interethnic couple. She uses you know to emphasize her emotions and to invite the other participants to contribute to the discussion.

19) <#>Sometimes when I see them on screen I could just see love radiating between the two <#>Two handsome and beautiful looking individuals you know (bdis_05)

Variant question tags tend to be used in an informative way across all four text types irrespective of whether the exact question tag form agrees to the main clause or not, as shown in (1, 2, 3, 13, and 14). Due to the overall low token frequency of variant question tags, a more detailed analysis of the exact form (e.g. variant vs. invariant uses or polarity) in relation to form and function was not possible.

While the formality of text types plays a crucial role for variation in question tag use, particularly for non-English forms, text type variation is more complex than an informal-formal dichotomy suggests. For many question tags, the speakers’ roles and the particular communicative needs that go along with that role in a given context are decisive for the selection of a particular question tag form.

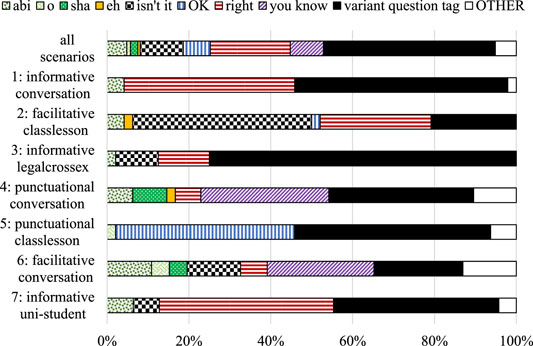

The survey study illustrates which question tag forms Nigerian students prefer in different situations and which attitudes they hold toward a selection of English and non-English forms. Overall, the survey shows a strong preference among the participants for variant question tags over invariant ones, which contrasts the corpus-based results on language use. Moreover, English forms are generally preferred over non-English ones in both parts of the survey. Figure 4 demonstrates the participants’ choices of question tag forms in the multiple-choice task in percent across all seven scenarios and for each one individually. Overall, variant question tags were selected most frequently (42.0%), followed by right (19.5%), invariant isn’t it (10.5%), you know (8.1%), and OK (6.6%). Eh and all non-English forms were strongly dispreferred. Of these forms abi was selected the most frequently, being chosen in 4.7% of all cases.

FIGURE 4. Results of multiple-choice task (N = 49). Classroom lesson and legal-cross examination are abbreviated as classlesson and legalcrossex, respectively.

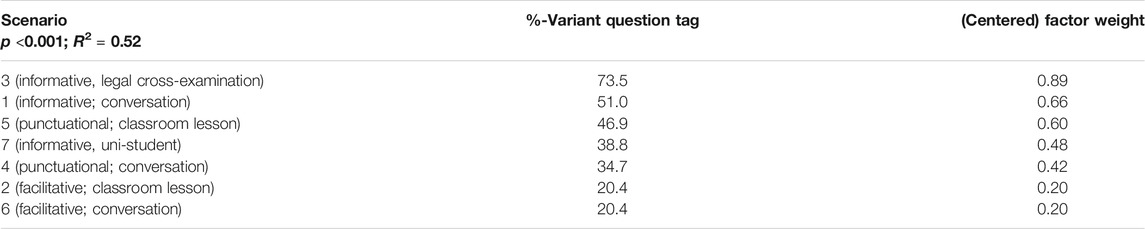

The multiple-choice task also shows that speakers’ choices for particular forms were constrained by the communicative settings and question tag functions targeted by the different scenarios. The preference for variant question tags is most pronounced in scenarios three, one, and five; the former two require the use of an informative question tag. Right was mostly chosen for informative uses in scenarios one and seven. At the same time, right was also chosen relatively frequently in scenario two.

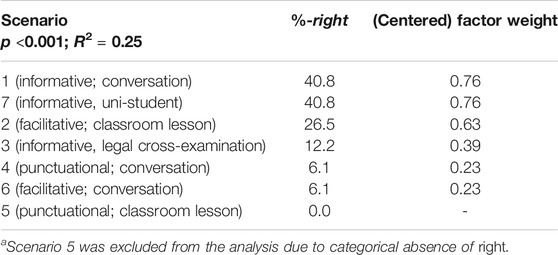

Regression analyses that investigate how scenario affects the selection of one form in contrast to all others for variant question tags and right demonstrate that scenario has a significant effect on the selection of either right or variant question tags, corroborating the descriptive results. The results in Table 7 illustrate that there is a strong preference for the selection of variant question tags in scenarios three, one, and five, while variant question tags are strongly dispreferred for facilitative uses in scenarios two and six. Table 8 shows that for right, there is a strong preference for informative uses as well, as given in scenarios one and seven. In addition, right is also a relatively frequent form in scenario two, which is a classroom lesson and targets a facilitative question tag. For punctuational uses and facilitative uses in a conversation right is dispreferred. The level of formality of a situation seems to be decisive for the difference between the selection of variant question tags and right for informative uses as variant question tags clearly dominate over right in the scenario depicting a legal cross-examination.

TABLE 7. Regression analysis on the effect of scenario on the selection of variant question tags in contrast to all other forms in the multiple-choice task (N = 49).

TABLE 8. Regression analysis on the effect of scenario on the selection of right in contrast to all other forms in the multiple-choice task (N = 49)tbl8fnlowasta.

The effect of the communicative setting and function are also evident for the other question tag forms that are overall less frequent and were hence not investigated via inferential statistics. For example, OK was only selected for scenario five, which depicts a classroom lesson and requires a punctuational question tag. You know was only selected for informal conversations between friends, either for punctuational (scenario 4) or facilitative (scenario 6) uses. Non-English question tags were only selected in scenarios depicting informal private dialogues. For example, 19% of students selected either abi, sha, or o in scenario 6. For invariant isn’t it, no clear usage profile emerges from the multiple-choice task.

The Matched-Guise-Test also demonstrates a clear preference for variant question tags and English invariant ones, while non-English forms and eh are perceived less positively. Figure 5 shows the mean ratings of the nine question tag forms (as different lines) on the six items on six-point scales. Values below 3.5 are negative and values above 3.5 positive. Generally, all speakers using question tags were rated rather positively, typical of an acquiescence bias (Garrett, 2010: 45). The descriptive statistics illustrate that the variant question tags seem to be rated overall most positively across the six items. In contrast, speakers using abi, eh, o, and sha were rated least positively. The ratings of invariant isn’t it, OK, you know, and right fall in between these poles; with speakers using right being rated somewhat less positively than the other four question tags.

Figure 5 also demonstrates that the ratings of the individual question tags vary substantially according to the rating item, but this level of variation is difficult to interpret. To facilitate the further interpretation of the data a Principal Component Analysis was run to extract individual components. Due to the rather small sample size, Principal Component Analysis is not ideal and the outcome should not be interpreted in mathematical detail but shows the general underlying structure of variation in the sample.7 Principal Component Analysis was forced to extract two components and Varimax with Kaiser Normalization was used as a rotation method. The Rotated Component Matrix was used to interpret which items form a cluster. According to this model, polite, educated and gentle clustered together to a first component, which has an eigenvalue of 4.4 and explains 75% of the variation. The factor loadings of the three items are very similar (polite: 0.88; educated: 0.87; gentle: 0.83). This first component was labelled ‘decency’. The second component is less central to the variability in the data as it has an eigenvalue of 0.6 and only explains 11% of the variation. Outgoing, direct, and friendly loaded onto this second component. With a factor loading of 0.92, outgoing is most central to the second component, followed by direct (0.76). Friendly is least important to the second component with a factor loading of only 0.62, and friendly also loaded onto the first component (0.64). However, friendly was still grouped to the second component as friendly fits outgoing and direct better on a conceptual level. This second component was labeled ‘expressiveness’. For further analysis, ratings for decency and expressiveness were calculated as mean values of the respective three items that loaded on the specific component.

Logistic regression modelling was used to further analyze variation in the decency and expressiveness ratings for the nine question tags. Decency and expressiveness ratings were used as the dependent variables in two separate models and question tag form as a fixed predictor variable. Table 9 shows the mean values for the decency and expressiveness ratings as well as the results for the regression models. Variation for the decency ratings is much more pronounced than for expressiveness. For the former ratings, there is a range of 1.83, while for the latter the range is only 0.74. For both dimensions, variant question tags and invariant English question tags were rated more positively than eh and the three non-English forms. For decency, these differences in the ratings reach the level of significance and the coefficients clearly illustrate this rating pattern. There are positive coefficients for the English forms except for eh, and negative coefficients for the non-English forms and eh. However, for expressiveness, the differences in the ratings did not reach the level of significance. Hence, no coefficients and R2 are reported.

Open comments on the different question tags were rare in the surveys. Most comments were made for the non-English forms abi, o, and sha. In many comments, participants tried to explain the specific pragmatic functions of the forms, for example highlighting that “the use of o is showing emphasis”, or gave English translations, such as “abi is a Nigerian slang for right”. Opinions were very divided in terms of the ‘correctness’ of the use of non-English question tags. One student commented that “The use of ‘abi’ is really wrong in English language. That is code-mixing. Mixing Yoruba and English”. In contrast, others expressed their appreciation of these question tags: “I love that use of ‘o’ like that”. Several students commented that the use of o, abi, or sha does not indicate a low level of education but is a common form of code-mixing in Nigeria: “abi is a Yoruba word, if it is used it doesn’t mean the user is uneducated. It’s just code mixing”. Students also stated that the use of non-English forms signals and also requires intimacy and a close relationship between interlocutors: “it is not proper to use abi for someone you just met”. Several comments highlighted that students generally perceived the use of question tag forms as informal: “speaker is informal with the use of you know”. The few comments made do not allow any closer analysis but illustrate that speakers are aware of the diversity of question tag forms and that these forms carry diverse indexicalities in Nigerian English.

This study has illustrated multilingual variation in question tag use in Nigerian English and Nigerian students’ perception of this variation. The corpus-pragmatic analysis of six dialogue text types of ICE-Nigeria has shown that Nigerian speakers use a wide range of English and non-English question tag forms. Similar multilingual variation has been described for Cameroonian (Mbakop, 2020), Philippine (Westphal, 2020), and Trinidadian English (Wilson et al., 2017). In contrast to the overwhelming focus on variant question tags in previous research (e.g., Tottie and Hoffmann, 2006; Borlongan, 2008; Barron, 2015; Parviainen, 2016; Hoffmann et al., 2017) in World Englishes, these types of question tags are marginal in Nigerian English as they only account for 2.5% of occurrences. Invariant uses make up 54.5% of these canonical question tag structures. However, they still cannot be viewed as particularly characteristic of Nigerian English in contrast to the many indigenous Nigerian forms, such as abi, o, or sef.

The strong dominance of invariant forms in general and the use of many indigenous forms is in line with other studies on New Englishes that have also investigated variant and invariant question tags (Wilson et al., 2017; Mbakop, 2020; Westphal, 2020). In contrast (Gómez González, 2018: 122) shows a higher frequency of variant than invariant question tag forms for British English. Taken together this means that New Englishes are not necessarily characterized by invariant uses of isn’t it or is it (not) as argued by Borlongan (2008), Parviainen (2016), and Hoffmann et al. (2017) but by the usage of a wide range of English and particularly non-English invariant question tags. Hence, future research on question tags in New Englishes needs to operationalize question tags as a multilingual set of diverse forms and should not be restricted to ‘canonical’ ones.

The multilingualism of question tags in Nigerian English is also evident for the form now, which seems to combine nativized patterns of English now (Oladipupo and Unuabonah, 2021) and Nigerian Pidgin na (Unuabonah et al., 2021). Furthermore, the high frequency of you know (71.2tpf) in contrast to Cameroonian (52.8tpf; Mbakop, 2020), Philippine (26.6tpf; Westphal, 2020), and Trinidadian English (43.4tpf; Wilson et al., 2017) suggests that this form might also be characteristic of Nigerian English in contrast to other New Englishes, but you know requires a closer cross-variety analysis.

Considering the high frequency of non-English forms, the fluid integration of these forms into Nigerian English, and their alternation with English forms, the strict distinction into English and non-English seems inapt. All question tag forms identified in the analysis, whether abi, right, or variant question tags, are part of the repertoire of speakers sampled in ICE-Nigeria when speaking English. Hence, all forms are part of Nigerian English but just have different origins and different usage patterns.

Text type has a strong effect on the frequency of all forms taken together and individual ones. Question tags are overall most frequent in private dialogues, followed by classroom lessons, broadcast dialogues, and legal cross-examinations. Hence, formality and the degree of pre-structuring seem to play a decisive role. The more informal the text type and the less predefined the communicative situation, the higher the frequency of question tags. Hence, question tags can be viewed as somewhat informal structuring devices in dialogues. In addition, the particular communicative setting/conventions of a text type and how these are realized are decisive for the use of question tags. In classroom lessons, there is a teacher who leads the dialogue with the students and has to integrate them into the classroom discourse. However, the analysis has shown that there are different teaching styles in classroom lessons in ICE-Nigeria. Some teachers have a quasi-written teaching style, dictating texts to the students and quoting extensively from written material, and use very little question tags. In contrast, other teachers have a more interactive teaching style, speaking freely and trying to integrate the students into the discourse by means of question tags.

Similar to Wilson et al. (2017) and Westphal (2020), text type also has a strong effect on the selection of particular question tag forms over others. The analysis has shown that most non-English question tag forms are mainly used in informal private dialogues, while they are rare in more formal public text types. In addition to text type, function is decisive for the use of specific question tags. Several forms have a very focused functional profile. For example, ah, eh, and o are dominantly used in a punctuational way, while abi and variant question tags are preferentially used for informative functions. These two factors interact and together influence the choice of individual forms. For example, the choice between abi and variant question tags is controlled by the formality of the text type. Abi is restricted to informal situations and variant question tags are used across all text types. OK is mainly used facilitatively, and Nigerian teachers used it particularly often for this purpose, similar to Trinidadian and Philippine teachers (Wilson et al., 2017; Westphal, 2020). Hence, the choice of specific forms is determined by the communicative needs of speakers in accordance with their discursive role. For example, you know is very versatile in ICE-Nigeria being used in facilitative and punctuational ways. You know is especially frequent in broadcast discussions. Hosts mainly employ it facilitatively to integrate the audience and the guests into the conversation. In contrast, guests use you know mostly in a punctuational way to emphasize their arguments.

The survey study contrasts the findings for language use strongly as it has shown a general preference for variant question tags over invariant forms and non-English forms are strongly dispreferred. Despite the general bias toward variant question tags, the students’ choices in the multiple-choice task are guided by the particular communicative settings and demands targeted in the different scenarios. These constraints on the students’ selections overlap with the usage profiles of individual question tags. For example, variant question tags were selected especially often for informative uses and OK for a classroom situation. You know was only selected for facilitative and punctuational uses in informal private dialogues. This means that the test – which is the first of its kind for discourse-pragmatic-features – works, as scenario has a significant effect on the students’ choices.

The Matched-Guise-Test has shown that the participants’ attitudes are guided by a prescriptive ideology (e.g., Osakwe, 2009; Mbakop, 2020: 1), which positions speakers using variant question tags as more polite, gentle, and educated. In contrast, abi, o, and sef were rated less positively in terms of the items reflecting the attitudinal dimension of decency. The strong dominance of this prescriptive ideology was further supported by comments devaluing non-English forms as incorrect for English. However, there were no differences in the ratings of the different question tags on items reflecting expressiveness. This means that all speakers using question tags were viewed as being more outgoing, direct, and friendly – irrespective of the particular form. The open comments also illustrated a certain pride in the Nigerian forms abi, o, and sef, which are viewed to mark a Nigerian identity when speaking English.

The mixed-methods approach of this study has illustrated the multilingual pragmatics of Nigerian English from two perspectives. On the one hand, indigenous Nigerian languages and Nigerian Pidgin have been shown to have a substantial influence on the use of question tags in dialogues from ICE-Nigeria. The Nigerian speakers sampled in the corpus combine English and non-English forms in fluid ways as forms originating from indigenous language are well-integrated into Nigerian English albeit to different degrees. For example, o is used frequently across a wide range of communicative situations and can be used for different pragmatic purposes. In contrast, several indigenous forms, such as ba and sef, are rarer and restricted to informal conversations, and have much narrower pragmatic profile, such as ah. As already argued, now is especially characteristic for the multilingual pragmatics of Nigerian English but requires further socio-pragmatic and socio-phonetic analysis. Both text type and function have a significant effect on the multilingual variation of question tag use and indicate that sociolinguistic factors should be considered when describing the multilingual dynamics of New Englishes, which exhibit substantial internal variation. Future variational pragmatic research on the multilingual pragmatics of Nigerian English or other New Englishes may also take into account macro-social factors, such as age and gender, but should still pay close attention to the particular roles speakers have in the contexts under analysis.

On the other hand, the survey study has shown that the acceptance of indigenous and Nigerian Pidgin forms is clearly lagging behind their widespread use in English. This difference between corpus and survey data for pragmatic phenomena is reminiscent of Schneider K. P. (2007) analysis of the speech act of thanking responses. Both perspectives are important for the assessment of the degree of nativization of Nigerian English (Schneider E., 2007). In terms of multilingual variation for question tags, the study suggests that there is a high degree of nativization in Nigerian English at this pragmatic level of variation, but there is a strong ‘complaint tradition’ (Schneider E., 2007: 43), which devalues local innovations. Further qualitative interviews (e.g., Anchimbe, 2018) are needed to investigate Nigerians’ perspective on multilingual variation in question tag use in more detail.

On a purely methodological level, this study has worked with a very wide understanding of what counts as a question tag relying on function-based criteria in contrast to much previous research that has used formal criteria (e.g., Tottie and Hoffmann, 2006; Borlongan, 2008; Barron, 2015; Parviainen, 2016; Hoffmann et al., 2017). The current approach is not unproblematic as many forms are included in the analysis that have a very focused functional profile and are rarely used for informative purposes. For example, you know and o are mainly used punctuationally, ah is exclusively used in this way, and OK mostly serves facilitative functions. In addition, the participants did not select you know, o, and OK for informative uses in the multiple-choice-test. Hence there is a dispreference for informative uses and the pragmatic profile of these forms differs significantly from variant question tags, which are mainly used informatively by the Nigerian speakers and selected most often for informative uses in the survey. However, variant question tags also fulfill other functions and are also selected by the Nigerian students for punctuational and facilitative uses in the survey. In addition, previous research on variant question tags in other varieties has demonstrated that while informative uses are very frequent, the majority of question tags is used in other ways. For example, informative (i.e., informative and confirmatory uses combined) only account for 36.9% in Tottie and Hoffmann (2006: 302) or for 32.6% in Borlongan (2008: 14). This means that there is still enough pragmatic overlap of ah, o, OK, you know with variant question tags to conceptualize all these forms as question tags. In conclusion, a function-based conceptualization of question tags casts a much wider net and shows a broader range of variation. This approach may be problematic as one of the defining criteria for sociolinguistic variables of equivalence of meaning is violated, as is generally the case for using discourse-pragmatic-features for a variationist analyses (Pichler, 2010; Pichler, 2013: 28–32). However, relying on specific formal criteria excludes many forms, which in the case of Nigerian English are integral parts of the speakers’ linguistic repertoire. This choice between form and function reflects the tension in the field of corpus-pragmatics, which brings together the two very different disciplines of pragmatics, which is mainly concerned with pragmatic functions, and corpus-linguistics, which relies mostly on forms (see Aijmer and Rühlemann, 2015: 1–9).

On a further methodological level, the corpus-pragmatic analysis of ICE-Nigeria has shown that the ICE corpora may be suitable to analyze multilingual variation in New Englishes. However, it is essential to investigate multilingual variables. Discourse-pragmatic-features seem especially suitable for such an endeavor as speakers in New Englishes have been shown to integrate indigenous forms when speaking English (e.g., Unuabonah and Oladipupo, 2018; Unuabonah, 2019; Unuabonah, 2020; Westphal, 2020). However, in order to describe the sociolinguistic dynamics of multilingualism in New Englishes, analyses must consider English and indigenous forms. Excluding entire groups of variants may veil essential aspects of pragmatic variation and may lead to biased conclusions. Corpus-pragmatic analyses of entire sets of discourse-pragmatic-features in New Englishes should use pre-defined concordance lists that are based on previous research on British or American English with caution and should consider other forms or ways of expressing similar pragmatic functions targeted in the analysis. Such an approach may complicate cross-variety comparisons but may show further differences between Englishes spoken as a native language and New Englishes not covered when multilingual variants are excluded. Besides discourse-pragmatic-features, ICE-Nigeria may also be used for close qualitative analyses of code-switching as the corpus itself contains many instances of code-switching to indigenous Nigerian languages, which however are often not transcribed but are still accessible through the accompanying sound files. Such a detailed qualitative approach may also look more closely at the exact pragmatic functions of question tags in a given situation, which were operationalized in a very generalizing way in this quantitative study to allow regression analyses.

Finally, the corpus analysis of question tags has shown that text type variation is essential for describing the dynamics of multilingual variation. Standard New Englishes are by no means homogenous entities, but local innovations and indigenous languages are integrated to different degrees, which can be operationalized along different text types. Although the ICE corpora may be used to illustrate multilingual pragmatic variation in New Englishes, their possibilities are somewhat limited due to the corpora’s main focus on (monolingual) Standard English. Hence, Mair’s (2011: 234) call for the compilation of multilingual corpora for New Englishes still applies, as such corpora may be more suitable to illustrate the multilingual pragmatics of New Englishes as well as multilingual variation on other levels of linguistic variation. Studies on New Englishes that describe multilingual variation are essential for a better understanding of their linguistic structure and hence for issues of description and codification. In addition to such studies on multilingual language use, research on New Englishes must also take into account the users’ perspective on linguistic variation more earnestly, which may well differ from the findings on language use and provide additional insights not anticipated.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

I acknowledge support from the Open Access Publication Fund of the University of Muenster.

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

I would like to thank Folajimi Oyebola carrying out the field work and all students at the University of Lagos who participated in the study. In addition, I would like to thank the two reviewers and the editors for their close reading and highly valuable suggestions and comments.

1See online at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=trLjM5XHELo.

2Parliamentary debates and business transactions were not used as discourse-pragmatic-features are rare in the former text type and texts from the latter type are very heterogenous in terms of the communicative setting.

3Sound files were available for all texts except for four conversations: con_9, con_11, con_12, and con_16.

4See Jowitt (2019: 139–141) for a discussion of the origin and meaning potential of several indigenous discourse markers typical of Nigerian English.

5The survey can be accessed online at: https://www.uni-muenster.de/imperia/md/content/englischesseminar/question_tag_survey_-_nigeria.pdf.

6The category ‘English’ includes a range of answers referring to English in one way or another, such as “education (English)”, “English language”, or “English”. However, it seems likely that some students misunderstood the question and inserted the name of the class.

7See Field (2009: 636–650) for a detailed discussion of sample size, reliability, and validity of Principal Component Analysis.

K. Aijmer, and C. Rühlemann (Editors) (2015). Corpus Pragmatics (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

Aijmer, K. (2013). Understanding Pragmatic Markers in English. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Algeo, J. (1990). “It’s a Myth Innit?: Politeness and the English Tag Question,” in The State of the Language. Editors C. Ricks, and L Michaels (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press), 443–450.

Anchimbe, E. (2018). Offers and Refusals: A Postcolonial Pragmatics Perspective on World Englishes. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Anderson, J. A., and Ansah, G. N. (2015). “A Sociolinguistic Mosaic of West Africa: Challenges and Prospects,” in Globalising Sociolinguistics: Challenging and Expanding Theory. Editors D. Smakman, and P. Heinrich (London: Routledge), 54–65.

Axelsson, K. (2011). A Cross-Linguistic Study of Grammatically-Dependent Question Tags. Stud. Lang. 35 (4), 793–851. doi:10.1075/sl.35.4.02axe

Barron, A. (2015). “"And Your Wedding Is the Twenty-Second of June Is it?",” in Pragmatic Markers in Irish English. Editor C. P. Amador-Moreno (Amsterdam: Benjamins), 203–228. doi:10.1075/pbns.258.09bar

Bautista, L. (2011). “Some Notes on ‘no in Philippine English,” in Exploring the Philippine Component of the International Corpus of English. Editor L. Bautista (Manila: Anvil), 75–89.

Biber, D., Johansson, S., Leech, G., Conrad, S., and Finegan, E. (1999). The Longman Grammar of Spoken and Written English. London: Longman.

Columbus, G. (2009). “A Corpus-Based Analysis of Invariant Tags in Five Varieties of English,” in Corpus Linguistics: Refinements and Reassessments. Editors A. Renouf, and A. Kehoe (Amsterdam: Rodopi), 401–414.