- Department of Political Science, Carleton University, Ottawa, ON, Canada

“Food” and “policy” are ambiguous concepts. In turn, the study of food policy has resulted in varying approaches by different disciplines. However, the power behind the discursive effects of these concepts in policymaking—how food policy is understood and shaped by different actors as well as how those ideas are shared in different settings—requires a rigorous yet flexible research approach. This paper will introduce the contours of discursive institutionalism and demonstrate methodological application using the case study example of Canada’s national food policy, Food Policy for Canada: Everyone at the Table! Selected examples of communicative and coordination efforts and the discursive power they carry in defining priorities and policy boundaries are used to demonstrate how discursive institutionalism is used for revealing the causal and material consequences of food policy discourses.

Introduction

In 1976 Richard Simeon (p. 449) argued “almost every aspect of policy-making in Canada remains shrouded in ignorance if not mystery. The need, therefore, is to develop both theory and information-gathering together; each must inform the other”. Forty-five years later, this argument still rings true for studying food policy development. “Food” and “policy” are two ambiguous concepts, lending to policy makers in Canada’s Indigenous, municipal, provincial, and federal governments to approach and frame food issues and solutions differently. Specifically, Canada’s federal system is built on the recognition and support of its component parts-the policies and priorities of each jurisdiction reflect its people and regional characteristics. This means that food policy is understood and applied differently across Canada, including within different policy sectors (e.g., agriculture, health, education, poverty reduction, land development and economic development) and at different times in response to the needs of different populations. Developing a national food policy is therefore considered a wicked policy problem1 in Canada.

Collectively, there is no standard framework across Canadian governments for developing and implementing food policy. This makes it challenging for policy actors2 to collaborate and for policy processes to be inclusive. Many scholars have highlighted the need for more integrated or systems frameworks to better align complex food environments (MacRae3 and Winfield, 20164; Lang, Barling and Caraher, 20095). Deriving from political science and policy studies, discursive institutionalism (DI) is a useful analytical framework for studying the complexities of food policy development in Canada. DI is an umbrella term that encompasses substantive content of ideas (objectives, motives, shared characteristics of actors involved in policy) as well as studies interactive processes of discourse (where ideas generate and under what conditions) to explain how institutions, including policies and programs, remain stable or change (Schmidt, 2011).

DI is a flexible and appropriate approach for understanding how ideas about food policy are communicated within and between different actors. It offers an interdisciplinary perspective for explaining the complexities of food policy development within complex institutional environments such as Canada’s. The first part of the paper contextualized the Canadian case study and impetus for DI. First, research project is situated by presenting the aim of the Research and the research questions. Second, the single case study is illustrated within contours of Canadian food policy to substantiate the impetus for DI. Third, the core elements of DI are presented, highlighting what factors are required to assess ideas as causal forces influencing policy development. The second half of the paper demonstrates the pliability of DI to food policy research from two perspectives. First, the methodology for studying the development of Canada’s national policy, Food Policy for Canada: Everyone at the Table! (2019) demonstrates how the DI framework can be applied by providing explanation of how the DI framework is used to analyze the Canadian case study. Second, select findings are presented to highlight important considerations and recommendations for adopting the DI framework; this section demonstrates how the DI framework was tested using the Canadian case study. Collectively, the latter half of the paper presents a dual trajectory to substantiate how DI can be used and should be considered in order to develop both theory and information-gathering together where each informs the other.

Aim of Research and Research Questions

Broadly, the research aim is to systematicity describe real-world and context-dependent constraints and opportunities that development of a national food policy faces in Canada. The underlying goal is to identify and describe how the ideas and beliefs of key actors were (or were not) causal forces in the development of Canada’s first national food policy between November 2015 and June 2019. Specifically, the single case study focuses on efforts to build an integrated national policy that coordinates policy intra- and inter-departmentally within the federal government as well as through inter-intergovernmental communication and coordination. It explores a variety of issues across Canada’s food system (i.e. food insecurity, student nutrition, agro-ecology, agricultural trade) and provides insights and contributions to better understand food policy within Canadian food studies.

The main research question is: To what extent have efforts for an integrated approach to national food policy influenced a shift towards a new approach to food issues in Canadian policy making? The supplementary questions are: 1) Where has the idea of a more integrated approach to food policy come from in Canada? and 2) How does Canada’s multi-level political system shape the possibilities and challenges associated with developing and implementing a more integrated food policy approach? The overarching question considers whether the “Food Policy for Canada” process demonstrates continuity or transformation of Canadian food policy. In turn, the first supplementary question asks about the cognitive frames that influenced the policy’s development while the second asks about the structural and procedural constraints and opportunities faced during policy development. These questions draw from and compliment different literatures in Canadian political science.

The Contours of Canadian Food and Agricultural Policy: The Impetus to Study the Complex Relationship of Ideas and Institutions in National Food Policy Development

Canada is a federation that includes a national government, ten provinces, and three territories. Under the British North America Canada The Constitution Act, 1867-1982, 2021 and subsequent Constitution Act, 1982, the provinces have the exclusive authority to govern in certain areas, such as health, natural resources, and education, while the federal government has authority over other areas, for example, trade and commerce. These two levels of government also share jurisdiction in certain domains, such as agriculture. However, since 1867, courts have added nuance to questions of jurisdiction related to many areas of food system governance, sometimes granting more power to the provinces (e.g., environmental protection and land management), and sometimes articulating a more expansive view of federal power (e.g., international trade) (Richardson and Lambek, 2018).

In turn, over the last 150 years, the various levels of government have each developed myriad laws, policies, and regulations governing different aspects of Canada’s food system(s). Canada’s earliest federal legislation focused on food safety and adulteration of food products (e.g., the Inland Revenue Act 1875 and the Adulteration Act 1884—early versions of the Food and Drug Act). Over time, the term “food policy” has expanded to encompass the importance of and intersections between policies focused on agriculture, fisheries, nutrition, public health, the environment, and economy, “insofar as these policies help define the food that is produced, processed, distributed and consumed in Canada or exported” (Andrée et al., 2018: p.8).

Federal legislation directly governing food includes the Food and Drug Act (1920, 1985), the Canada Safe Food for Canadians Act (2012), the Pest Control Products Act. S.C., 2002, to name just a few. Canada also has cost shared federal-provincial policy frameworks such as the Canadian Agri-Food Policy Framework. Then, there are federally funded programs that shape food systems outcomes such as Nutrition North Canada, a program which subsidizes food retailers in select remote communities. Canada also has developed national strategies in consultation with provinces and territories, such as the Poverty Reduction Strategy (2018) and National Housing Strategy Act (2019) as well as federal dietary guidelines found in the Healthy Eating Strategy (2016) and Canada’s Food Guide (2019). Meanwhile provincial, municipal, and territorial laws and policies, including recent provincial food policy efforts in Québec and British Columbia, as well as a raft of recent municipal food charters, combined with the effect of Comprehensive Land Claim Agreements negotiated between the Crown and Indigenous governments, all add layers of complexity to the policy landscape shaping food systems in Canada (Martorell and Andrée, 2018).

Furthermore, since the 1970s Canada has had two federally led food policy efforts: A Food Strategy for Canada (1977) and Canada’s Action Plan for Food Security (1998) (Andrée et al., 20188). However, the substance of both policies reflects discursive efforts supporting the federal government’s international trade relations and economic objectives for the agricultural sector. Predominant focus on these facets and the absence of social and environmental externalities ultimately lends to material consequences of Canada’s historical patchwork of food-related law and policy that lacks coherence or a common vision of a healthy, just, and sustainable food system.

In response to this trend, Canadian stakeholders call for an integrated “pan-Canadian approach” (Andrée et al., 2018), or a “joined-up food policy” (MacRae, 2011; MacRae and Winfield, 2016), one which requires coordination across multiple federal policy domains (finance, health, environment, fisheries, agriculture, etc.) and levels of government, as well as encourages active engagement with civil society and industry actors. Between 2000 and 2014 these concerns gained enough momentum to move national food policy onto the federal agenda. In 2015, the window of opportunity opened when Prime Minister Justin Trudeau mandated Minister of Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) Lawrence MacAulay to develop “a food policy that promotes healthy living and safe food by putting more healthy, high-quality food, produced by Canadian ranchers and farmers, on the tables of families across the country” (Canada, 2015).

This moment was met with both excitement and concern by many stakeholders; at stake was the possibility to rectify shortfalls of the past. However, the ideas of what a national food policy could and should look like varied across food system actors. Some wanted transformative policy that proactively attended to issues faced by certain populations or regional needs (e.g., northern and indigenous food insecurity6) while others desired a “high-level” approach that reinforced and justified the existing agricultural framework but made room for slight adjustments (e.g., integrating programs or incentives that support the organic sector). The mix of demands from stakeholders and existing shortfalls of agricultural policy frameworks placed AAFC’s food policy team in a challenging position: it lacked the necessary resources (i.e., available labour, expertise, funding, time) and precedence within the Department (e.g., existing policy templates, jurisdictional authority) to meet all stakeholder expectations. In June 2019 Canada released Food Policy for Canada but the final policy document was criticized for lacking focus and proactive direction to achieve all the policy’s objectives in an equal and effective manner.

Collectively, Canada’s patchwork approach to agricultural, agri-food, and food policies demonstrates the need to study the development of Canada’s national food policy from an institutional approach, one that considers its historical underpinnings as well as exploring current constraints and opportunities within and across policy domains. The next section delves into the theoretical framework of DI highlighting important elements relevant for studying national food policy development.

How the Research Compliments and is Substantiated by Existing Literature

A scan of Canadian food policy literature reveals there are no other examples of DI in Canadian food studies literature. However, Skogstad’s (2012) work on agricultural policy shows that certain policy paradigms have played an important role in Canadian agricultural policy and help explain why food policy emerged and is evolving as a distinct policy field. In Canada, food policy is distinguished from agricultural policy by its focus on the production of food and agricultural products for sustenance and human necessity (e.g., food as a human right; policy reflecting social justice issues). However, it has historically been dominated and subsumed by AAFC, with its focus on economic and trade of agricultural products. Thus, conceptualizations of food policy as social policy are historically not included in the federal Agricultural Portfolio.

Skogstad (2012) identifies three paradigms of agricultural policy in Canada that have emerged since the Second World War. First, the Productivist Paradigm in Canada was shaped by state assistance programs between 1945–1980 with the objective to develop high quality and safe products for consumption, and to increase the overall amount of food produced ensuring a secure supply for both domestic consumption and for international export (Skogstad, 2008; Skogstad, 2012). Second, the Global Trade Regime Paradigm, underpinned by liberal market competitiveness (1980–2000) legitimized capitalist and corporate restructuring, globalization, overt dismantling of the welfare state, and reinforcing of state-market relations (Skogstad, 2008; Skogstad, 2012). During this period, agricultural reform became a priority for many countries, including Canada, and consequently, the Canadian government distanced its control and oversight of certain agricultural goods and services allowing for commodities to be more competitive in the global market (Skogstad, 2012). Finally, the still emergent Multifunctionality Paradigm (2000-present) is implicated in more comprehensive policy approaches but has had limited impacts in Canada to date. Specifically, “a multifunctional paradigm of agriculture puts value on the non-commodity social, environmental, and rural development outputs of agriculture, and recognizes that the market either will not produce them or will underproduce them—and rewards agriculture for doing so” (Skogstad 2012: 22). Examples of such non-commodity outputs include organic food production, traceability, and consciousness of environmental externalities.

Canada’s agricultural policy making is dominated by the Productivist and Trade Regime Paradigms. This is illustrated by the continued focus on export orientated agricultural production and increased production for international trade. Further, this approach has held because it safeguards against crises in Canada’s food system. That is, crises in the production and processing of agri-food goods (e.g., disease outbreaks among livestock; food safety recalls) do occur but their impact is mitigated or not identified as high priority to push decision-makers to consider alternative approaches for food and agricultural policy, such as a national food policy. In other words, the material consequences of the Productivist and Trade Regime Paradigms suggest Canadian agriculture and its management are strong. In turn, however, benefits to the overall economic well-being of the Canadian agriculture sector (e.g. corporate investments and state supported industrial farming practices) mask ongoing social justice issues (i.e. uneven distribution of food among populations, animal welfare) and negative environmental consequences (i.e. jeopardizing future sustainable food production).

Complementary to Skogstad’s argument that the Multifunctional paradigm was still emergent in Canada in 2012, the national food policy conversation leading up to 2015 suggested a distinct discourse of food policy was gaining momentum, placing pressure on the existing agricultural policy framework. Specifically, the food policy discourse includes a larger breadth of issues brought forward by stakeholders who historically have not been part of agricultural policy development. The case study of “Food Policy for Canada” compliments Skogstad’s work by exploring whether and how agricultural policy paradigms in Canada are connected to but distinct from food policy paradigms and whether agricultural paradigms have shifted (or not) with the rise of food policy discourse and a whole of government approach to food policy making.

The supplementary research questions speak to the institutional constraints for integrative policy. Reflecting MacRae’s (2011, 2016) work on integrated or joined-up food policy, existing politics and political institutions pose both possibilities and challenges for forming an integrated national food policy in Canada. MacRae (2011) explains that food is a complex and challenging policy area because several dynamic factors are concurrently present, including: 1) intersections between a number of policy systems that are historically divided intellectually, constitutionally and departmentally (Barling et al., 2002; Skogstad, 2008); 2) Canadian government(s) have not institutionally enshrined food policy (e.g., a Department of Food does not exist) (Anderson, 1967; Cameron and Simeon, 2002; Simeon and Nugent, 2012).

This project considers the structural and procedural mechanisms of policy making within the Canadian federal system to better understand the communication and coordination challenges in designing Food Policy for Canada. Three areas come to the fore: 1) centralization 2) intergovernmental policy coordination with provinces and territories, and 3) inter-departmental and intra-departmental cooperation and collaboration in policy development. However, integrative policy points to centralized decision-making and accountability. Thus, the latter two areas of literature discussed are heavily reflective of the former.

Since 1867, Canada has swung between centralist7 and decentralist approaches. More recently, centralization and decentralization occur simultaneously across different policy fields and between jurisdictional authorities where policy makers agree both approaches are warranted. André Lecours (2017: 57) explains “the last several decades have witnessed decentralization in several policy fields, such as agriculture, citizenship and immigration, and natural resources, but also centralization in such crucial ones as social welfare and language.” Donald Savoie (1999), Savoie (2008), however, argues that power effectively rests with the Prime Minister who sits at the centre of government and strategically surrounds themselves with hand selected actors (e.g., ministers, civil servants, political advisors). The overarching objective of these political elites is to construct a strong central government. In turn, centralization is seen as a strategic approach for controlling communication and coordination of policy development. Collectively, this literature notes Canada’s federal policy making is more centralized than most (Hansen et al., 2013). Therefore, studying the development of national food policy which rests on the idea of integrative policy, requires the consideration of the power relations of actors (and their ideas) within and across different political institutions under centralized constraints, and speaks to understanding how and why coordinative and communicative discourses might differentiate within and across these policy arenas.

The literature of inter-governmental policy coordination between the federal government, provinces, territories, as well as municipalities and Indigenous governments (Csehi, 2017; Bakvis and Skogstad, 2020; Simmon, Graefe, and White, 2013), suggests that food policy development has historically occurred separately, with the exception of the Agriculture Partnership. Hedley (2006) argues that such an approach reflects the idea that governments confine their activities to their own arenas and are reluctant to intervene in food policy decisions of the broader Canadian food system unless it aligns with the greater socio-economic pressures of the day. In turn, the issue of coordinating policy development through government collaboration is one of the major intergovernmental challenges facing Canada and needs more attention (Bakvis and Brown, 2010). Regarding the development of “Food Policy for Canada” it is necessary to capture the communicative and coordinative discourses occurring (or not) between governments to comprehend if and how intergovernmentalism is a key attribute to food policy formation. Thus, the fiscal, political, and administrative incentives used to invite or hinder communication and coordination across the different orders of government must be considered to explain how and why actors participated when shared rule remains underdeveloped and/or constantly changing.

Interdepartmental coordination8 or “new” or horizontal governance has been widely accepted as the current model of governing (Rhodes, 1997; Philips, 2004). In a number of policy areas (e.g., environment, health) there is a growing recognition the traditionally disjointed and siloed approach to policy making produces challenges for solving complex and sensitive policy problems. In response, this literature emphasizes that governments should encourage interdepartmental interactions, dialogue and exchange of information, all preconditions for the development of mutual trust and shared worldviews, as a strategy to enhance interdepartmental coordination (Peters, 1998; Salamon, 2002; Peters, 2003; Perri, 2004). In this effort central agencies can either play a disproportionate or supportive role in shaping the environment for policy development under interdepartmental coordination, especially when deciding policy solutions and administrative frameworks that are detail oriented to a policy or program’s objectives (Bakvis and Juliett, 2004). Here the literature points to the need to identify the variety of choices surrounding the type of objectives pursued, as well as deep deliberations of the appropriate combination of instruments and the extent of support for institutional innovations (Bourgault and Lapierre, 2000; Lahey, 2002; Gagnon, 2012).

Discursive Institutionalism: A Theoretical Approach for Addressing Ideas and Policy Frames as Causal Forces in Policy Development

Individual actors and groups operate in structured environments or institutions, which Peter Hall and Taylor (1996, p. 938) define as “the formal or informal procedures, routines, norms and conventions embedded in the organizational structure of the polity or political economy”. Therefore, from the institutional perspective, policy can be understood as an institution and the policy making process requires critical attention. DI helps to explain how human behaviour is shaped through institutionally prescribed rules, and conversely, how behaviour—especially discourse—can influence institutional change (North, 1990; Pierson 1993; Goodin, 1998; Immergut, 1998; Ostrom, 1999; Pierson, 2000a; Pierson, 2000b; Pierson, 2000c,; Kay, 2005; Pierson, 2005; Pierson, 2006). The DI framework rests on the premise that ideas are causal forces in institutional settings, and brings together ideas, discourse, and institutions by addressing how agents create, maintain, and change institutions by considering how ideas influence the political and policy making context within a given set of institutional rules and dynamics.

DI considers how organizational rules and procedures coordinate the actions and cognitive limits of institutional actors (Berman, 1998; Schmidt, 2008), but also position some actors to wield ideational power through discourse, that is “the capacity of actors (whether individual or collective) to influence (other] actors’ normative9 and cognitive10 beliefs” (Carstensen & Schmidt, 2016: p. 320). Ideational discourse considers the source and articulation of ideas, the context and objectives of those ideas, the meaning and mode of delivering the intended message, the target audience(s), as well as what is not communicated. From this perspective, policy actors are ““sentient” (thinking and communicating) agents who generate and deliberate about ideas through discursive interactions that lead to collective action” (Schmidt, 2011: p. 107). In turn, understanding how and why actors think, say, and act is important for explaining the driving forces of policy formation and change.

Policy Frames and the Logics of Communication

In order to conceptualize and explain agency, actors’ behaviour is distinguished between foreground and background discursive abilities. Foreground discursive abilities are the deliberate and persuasive arguments actors make to change or maintain institutions and policies, and includes the order, context and manner in which communication occurs. Background discursive abilities are internal to actors and are usually subconscious (Schmidt, 2008). These are the processes that enable actors to speak and act without consciously following rational or external rules. Taken together, these discursive abilities represent a logic of communication, “which enables agents to think, speak, and act outside institutional constraints even when located within them, to deliberate about institutional rules even as they use them, and to persuade one another to change those institutions or to maintain them” (Schmidt, 2010: p. 1). Therefore, DI takes into consideration both the influence institutions have on actors, and how actors simultaneously influence institutions (Fioretos et al., 2016).

The logic of communication tends to be conceptualized through the formation (and change) of policy frames. A policy frame is “coherent systems of normative and cognitive elements which define mechanisms of identity formation, principles of actions, as well as methodological prescriptions and practices for actors subscribing to the same frame” (Surel, 2000: 496). From an analytical standpoint, DI scholars investigate the core beliefs, interests, and objectives of actors to understand their perception of discrepancies between what is and what ought to be (Berman, 1998; Bhatia and Coleman, 2003; Schmidt, 2011). Studying discourses—that is, how ideas are communicated to and coordinated between actors—helps with understanding how policy-actors’ attention comes to focus on particular elements or issues, whether attention is diverted from alternative perspectives, and how decision-makers come to define what are acceptable and unacceptable choices. Schmidt (2011: p.106) argues that “only by understanding discourse as substantive ideas and interactive processes in institutional context can we fully demonstrate (ideas and discourses’) transformational role in policy chane”.

DI categorizes discourses into communicative and coordinative, depending on the institutional context within which they occur. Coordinative discourse occurs in the policy sphere11 when policy actors, consisting of state representatives (bureaucrats and public officials) and non-state stakeholders (advocacy groups, academics, for-profit organizations), are “engaged in creating, deliberating, arguing, bargaining, and reaching agreement on policies … ” (Schmidt, 2011: 116). They may have different resources, and varying degrees and kinds of influence, but ultimately they have shared ideas about a common policy enterprise (Haas, 1992). Comparatively, agents of communicative discourses attempt to influence mass political opinion and engage with the public to elicit support or disapproval for policy ideas. Habermas (1989) argues this can include any actor or manner of public engagement and communicative action that ultimately forms opinions (e.g., media, advocacy and interest groups), but Schmidt (2011) points out that in DI, communicative discourses are typically strategically designed by political actors and externally directed toward non-state audiences (e.g. government media release).

Policy Frames as Indicators of Transformation and Continuity

With the DI framework, policy frames are used to identify which and how norms and preferences that influence behaviour come to persist and change over time (Kangas et al., 2014). Policy frames rise and fall with changing political contexts and come to be replaced with new (or sometimes old) ideas and interests. The focus on policy frames helps theorists understand how old policy ideas give way to new ones, and how policy undergoes fundamental change (Blyth, 1997; Blyth, 1998).

A new policy frame and its associated ideas alone, however, do not come to indicate a shift in policy making. Instead, policy actors come to frame policy problems differently, and in turn, certain policy choices or policy frames appear more possible while others less so. If successful, an alternative, mutually agreed upon policy frame emerges (Bhatia and Coleman, 2003). As institutions shape the rules that govern which actors, whose ideas, and under what constraints are influential, the relationship between ideas (as expressed by institutional actors) and institutions is mutually constitutive and reinforcing, and sentient actors are the agents that connect the two. Here the DI framework focuses on the way in which institutions influence whether the discourse will be communicative or coordinative—that is, how and with whom do actors have to engage to make their desired outcome happen.

Collectively, the logic of communication and its intricate components highlight important elements for unfolding the narrative of Food Policy for Canada. Ultimately as the precedent structures and functions of Canada’s federal system suggest challenges for designing and implementing a national food policy, and there are many conceptualizations of what a national food policy can or should entail, DI is necessary for parsing out the substance and processes that lead to the cognitive and normative elements found in the final policy document. Further, this approach can demonstrate logic of communication, helpful for considering if a shift in federal policy making, distinguishing food policy, has occurred.

Food Policy for Canada Case Study Methodology

The example methodology provided in this section is gleaned from the author’s dissertation research and is supported by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) funded partnership Food Locally Embedded Globally Engaged (FLEdGE)12, 13.

Methods and Methodological Framework

Looking across the literatures of policy paradigms, centralization, intergovernmental policy coordination, and inter-departmental policy development, identifying and considering the normative and cognitive elements of integrative policy and policy transformation requires a rigorous set of methods and methodological framework.

Data collection included primary data gleaned from semi-structured interviews and participant observation, as well as the collection of secondary data from policy documents. These methods occurred simultaneously between 2016 and 2021. Fifty-eight14 semi-structured interviews occurred with elite state and non-state policy actors active in the development of Food Policy for Canada. Interviewees included politicians, public servants, academics, agri-food industry representatives, and not-for-profit organization representatives. Participant observation occurred at academic conferences (i.e., Canada Food Law and Policy, Canadian Association of Food Studies), government led events (i.e., public consultation online survey, Food Summit), and non-governmental led efforts (i.e., Food Secure Canada’s General Assemblies, developing a policy brief with the ad hoc Working Group on Food Policy Governance). The collection of policy documents included resources generated by policy actors from both within the state and from organizations across Canada’s food system(s) (e.g., policy briefs, reports). These resources included those both published prior to and during the 2015–2019 policy’s development periods. Those collected before reached as far back as the 1970s and provided data of food policy discourses before the case study and a means for considering if policy frame transformation was occurring.

With three methods of data collection the data analysis required triangulation to confirm observations. Manually transcribed interviews were coded along side participant observation field notes and policy documents using NVivo 12 coding software. Coding highlighting themes reflecting cognitive and normative policy elements (e.g. common or distinct ideas or asks of policy actors—alleviating food insecurity, systems thinking approach, national food policy council—, specific policy instruments) as well as highlighted the processes of discourses, specifically, the context and means for conveying and coordinating information (e.g., public forums, politicized media events, departmental mandates, constitutional requirements, closed door meetings, types of policy instruments). Text, discourse, and thematic analysis were conducted to identify and examine the differences/similarities and points of convergence/divergence of coded data.

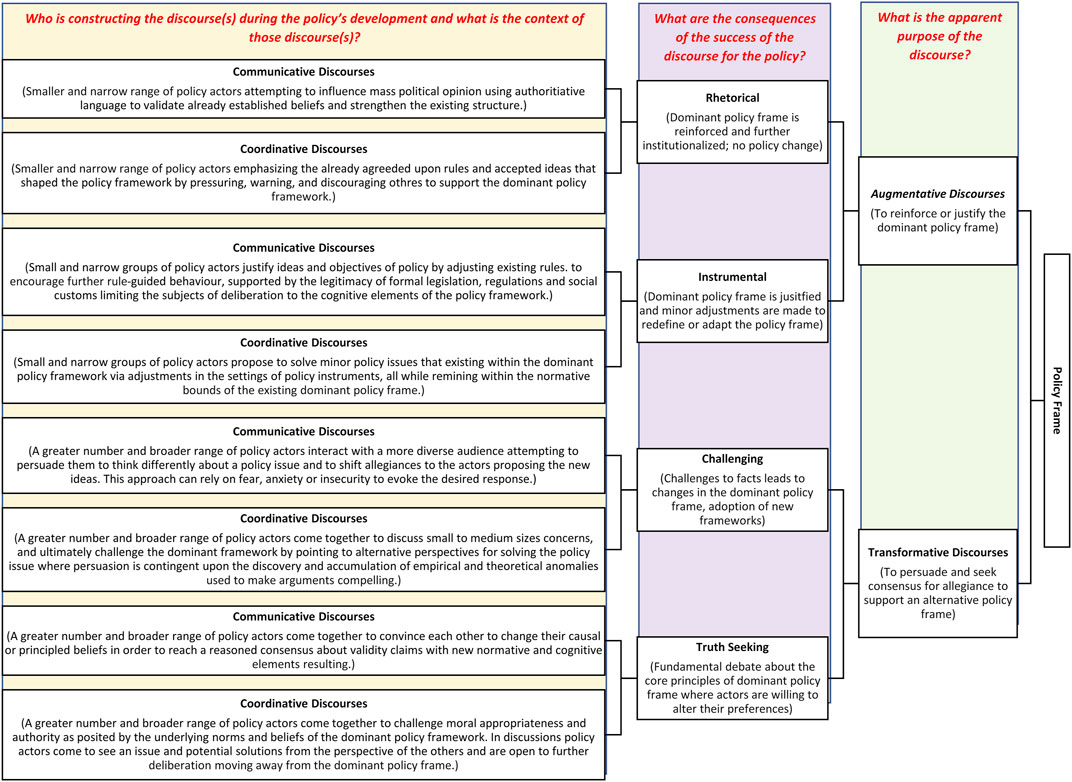

In order to identify and assess the ideational and institutional elements that demonstrate constraint and opportunity of the policy frame(s), the author developed the following framework (Figure 1) adopting tenets from Vandna Bhatia and William Coleman’s (2003: p.720–721) Framework for Analyzing Political Discourse and Policy Change. Figure 1 rests on three questions.

FIGURE 1. Methodological framework for analyzing communicative and coordinative discourses and policy change.

First, it is asked: Who is constructing the discourse(s) during the policy’s development and what is the context of those discourse(s)? Here the researcher looks for elements that highlight the underpinning normative and cognitive aspects prominent in the policy frame: specific policy elements (problem definition, causal relationships, problem ownership, accountability, proposed solutions, policy instruments) and generic policy elements (new or historical policy relevant knowledge, individual or collaborative efforts activities or events). Data is categorized as coordinative discourse if it demonstrates policy actors are engaged in creating, deliberating, arguing, bargaining, and reaching agreement on policies, or as communicative discourses if it demonstrates an attempt to influence mass political opinion and engage with the public to elicit support or disapproval for the policy frame. Collectively, the data reveals: 1) what policy-actors’ attention came to focus on particular ideas, elements, or issues; 2) whether attention has been diverted from alternative perspectives; 3) and how decision-makers come to define what are acceptable and unacceptable choices within the policy frame.

Looking across communicative and coordinative examples, the data is then considered for the kinds of influence and power different actors had and executed (or withheld) in shaping the policy frame. This is addressed by the second question: What are the consequences of the success of the discourse for the policy? Here the researcher considers if the communicative and coordinative examples point to trends in the types of discourse(s) occurring. As the research focuses on the causal forces of discourse and how communicative or coordinative discourses can serve to reinforce or to alter an existing policy framework, the data is categorized under rhetorical, instrumental, challenging, or truth-seeking discourses.

Rhetorical discourse furthers an existing institutionalised and dominant policy frame where language is authoritative to validate already established beliefs and “strengthens the authority structure of the polity or organization in which it is used” (Bhatia and Coleman, 2003: 721; Edelman, 1997:109). Normative foundations of the framework are at the center of communication to emphasize what the policy issue(s) faced by society are and how the public had agreed to address them. Specifically, the already agreed upon rules of the system are emphasized and linked back to the previously accepted ideas that shaped the policy framework in the first place. Such efforts are illustrated through pressuring, warnings, and discouragement to support the dominant policy framework and actors become labeled based on their merit, competence, or other characteristics (Bhatia and Coleman, 2003).

Instrumental discourse is used to acknowledge small policy malpractices or inconsistencies that existing within the dominant policy framework. Such problems reflect efficiency and effectiveness that “policy elites propose to solve through adjustments in the settings of policy instruments, all while remining within the normative bounds of the dominant policy frame” (Bhatia and Coleman, 2003: 721). Here, the aim is to justify ideas and objectives of policy by adjusting existing rules. This encourages further rule-guided behaviour, supported by the legitimacy of formal legislation, regulations and social customs. Bhatia and Coleman (2003) explain this type of discourse limits the subjects of deliberation to the cognitive elements of the policy framework (policy relevant knowledge, activities, events and actions that affect desired outcomes).

Challenging discourses are directed outward seeking to alter a more diverse audience to think differently about a policy issue and to shift allegiances to the actors proposing the new ideas (Bhatia and Coleman, 2003: 721). This approach can rely on fear, anxiety or insecurity to evoke the desired response, or appeals can be reasoned and based on factual information/evidence. The cognitive elements of this policy framework challenge the facts that the dominant policy framework rests, and ultimately point to alternative perspectives of the policy issue. In turn, disagreement circulates the relevancy and accuracy of factual information, and how it should be interpreted. Drawing on Hall (1993), Bhatia and Coleman (2003: 721) explain “persuasion takes the form of a cognitive process that is contingent upon the discovery and accumulation of empirical and theoretical anomalies in the dominant policy frame.” Collectively, facts and reasons are used to make arguments compelling.

Truth seeking discourses challenge moral appropriateness and authority as posited by the underlying norms and beliefs of the dominant policy framework. In this discourse “actors try to convince each other to change their causal or principled beliefs in order to reach a reasoned consensus about validity claims” (Risse, 2000: 9), and compared to the other three discourses noted above, actors are prepared to be persuaded when they see an issue from another perspective. If successful, an alternative and agreed upon policy frame emerges with new normative and cognitive elements (Bhatia and Coleman, 2003: 721). Schön and Rein (1995: 45) refer to this process as “frame reflection where in discussions policy actors come to see an issue from the perspective of the other’s policy frame, thereby creating a “reciprocal, frame-reflective discourse”.

Categorizing data as rhetorical, instrumental, challenging, or truth-seeking discourses is also important for understanding if, how, and why either communicative or coordinative discourses may have held more influence in the policy’s overall development and if those trends ultimately lend to continuity or transformative policy change. Specifically, challenging and truth-seeking discourses are hypothesized to be more conducive to significant policy change than are rhetorical or instrumental discourses (Bhatia, 2005). This leads to the third question: What is the apparent purpose of the discourse? Reflecting the DI framework, this question brings together data from questions 1 and 2 regarding the core beliefs, interests, and objectives of actors to understand their perception of discrepancies between what is and what ought to be (Berman, 1998; Bhatia and Coleman, 2003; Schmidt, 2011). In turn, trends across the data are grouped and categorized as either augmentative discourses, where actors focus on preserving an existing dominant policy frame, or transformative discourse, where actors seek to persuade others of an alternative frame.

Findings, Discussion and Recommendations: Different Ways of Using DI

Here select findings are presented to highlight important considerations and recommendations for adopting the DI framework. Specifically, this section demonstrates how the DI framework was tested using the Canadian case study and discussed important considerations for selecting and using the DI framework. As with other interpretive approaches researchers adopting the DI framework find themselves reviewing and adjusting their methods and methodology as they progress. Recalling Simeon (1976) argument, that we must develop both theory and information-gathering together in order for each to inform the other, this should not be seen as a burden but instead a learning process and steps required for validating the research. The case study of Food Policy for Canada garners important learning curves for others who are considering DI.

Preliminary Findings

The preliminary findings of this research situate Food Policy for Canada as demonstrating instrumental and augmentative discourse. Early stages of the policy’s development do demonstrate challenging discourses (i.e. where AAFC’s food policy team outwardly seeking a more diverse audience to conceptualize the possible solutions to the policy issue and to shift allegiances to the actors proposing the new ideas). However, later stages of the policy’s development, those focused on writing the policy document and including/excluding certain ideas, demonstrates instrumental discourse. Specifically, the predominant policy approaches in AAFC limited the policy’s development to minor adjustments of existing policy and programs because the discourse limited and focused the subject of deliberation to the cognitive elements of the policy framework (i.e. previous policy relevant knowledge, activities, events, and actions that affect desired outcomes under the Agricultural Portfolio). Collectively, although new policy actors were invited and enabled to participate in the policy’s development, behaviours of state policy actors continue to be heavily influenced by the structures, processes, and policy norms underpinning the historical trajectory of AAFC and the government of the day.

The preliminary findings, however, do not provide a comprehensive narrative of the intricate elements that shaped the policy’s development. Below select examples provide further detail and explanation. Furthermore, the subsequent sections point to important facets researchers should consider in order to parse out important information when designing and revising their methodology and selecting analytical framework(s).

Identifying and Explaining Ideational Power Relations

When analyzing the data, it became apparent that the substance of ideas and the processes lending to communicative and coordinative discourses were not consistent throughout different stages of the policy’s development. In turn, analysis needed to identify and explain the ideational power relations occurring between policy actors during the individual stages of policy development. When this new layer of analysis was applied it was found that multiple policy frames were present and being fought for by different policy actors during different stages of the policy’s development. Martin Carstensen and Vivian Schmidt’s (2016) work on types of ideational power proved helpful for unpacking and explaining how power was shaped by ideas and institutions within the policy’s development.

Power through ideas is the capacity of actors to persuade other actors to support and adopt their views through reasoning and argument. In this view ideational power is not about manipulating (Lukes, 1974) but demonstrating to other actors how a particular approach should stand out. In this sense, assessment of cognitive elements focus on an actor’s ability to clearly define the issue at hand and to put forth adequate and appropriate solutions. In turn, power is the ability to affect the range of possibilities other actors will consider (Campbell, 2004; Schmidt, 2006). Assessment of normative elements reflect how well an actor posits the narrative about the causes of the problem and what needs to be done (Schmidt, 2006). Together, these elements demonstrate if and how an actor can stand back and critically engage with the ideas they hold.

An example of power through ideas is where stakeholder groups actively engaged with AAFC’s Food Policy Team to broaden their comprehension of the issues and potential solutions regarding food insecurity in Canada. Before public consultations (2015–2016) the AAFC Food Policy Team indicated a narrow understanding of the issues inhibiting food security in Canada. This is demonstrated via the first of the Four Pillars15 (Food Secure Canada, 2016): the objective of “increasing access to affordable food”. Many stakeholders took offense to this problem definition as it did not adequately identify or consider the underlying systematic problems lending to food insecurity nor population specific needs. However, during and after public consultations in summer of 2017 the understanding of food insecurity in Canada and the possibilities for achieving food security were recognized by AAFC. In turn, AAFC’s 2018 What We Heard Report16 identified a broader scope of priorities under the banner of food security: “increasing access to affordable, nutritious, and culturally-appropriate food in Canada included, among others: recognizing the link between food and cultural identity; increasing food security for all people living in Canada; addressing food security as an issue based on income security; increasing food security in Indigenous and isolated northern communities; and supporting local, community-based solutions to food security” (p. 6). Altogether, the capacity and power of policy actors outside AAFC influenced the Food Policy Team to support and adopt alternative views through reasoning, evidence, and argument.

Power over ideas is the ability of actors to control or dominate the meaning of ideas. Carstensen and Schmidt (2016) point to three areas where power can be examined. First is the control over the production of meaning and the diffusion of information occurs where an actor in power (e.g., prime minister, minister of cabinet) exercises their coercive power to promote and impose their ideas in order to guard against structural and institutional changes that may undermine them. Such power is exercised through mass media and propaganda to shape attitudes, convince the general public of the validity of their ideas, and crowd out alternative ideas. The second area considers actors with less power (e.g., advocacy groups) who are able to shift others into conforming with their ideas, but not through persuasion. The actor(s) affected may not believe in the ideas they adopt but the way in which discourse is employed is strong enough to compel them to adhere to or conform with alternative ideas. The third area considers the capacity of actors, usually powerful political actors, to resist considering alternative ideas. The legitimacy of resistance is often based on technical or scientific information which substantiates parameters of what actions and solutions are workable or best fit.

Between 2015 and 2019 AAFC’s Food Policy Team communicated and collaborated with a number of state and non-state policy actors to best capture the policy issues and potential solutions, demonstrating a collaborative control over the production of meaning. However, as the policy’s draft moved through the formal adoption process between 2018 and 2019 (i.e., 5 revisions and memorandums for Cabinet to consider) the content and specific language adopted in the final policy document was constantly altered by higher level policy and political actors. For example, on June 17, 2019 on route to the launch of the policy in Montreal, the Minister of Agriculture, Marie-Claude Bibeau, was editing and reviewing the policy’s contents even though the document had already been approved. One interviewee noted the adjustments caught the AAFC Food Policy Team off guard requiring them to halt releasing the final policy document and amending the webpage. Further, the adjustments made did not necessarily change the focus of the policy, but the added language and content was said to better reflect the Government’s priorities at that time. Specifically, the Government’s focus on expanding international agricultural exports: “There is tremendous potential for economic growth within Canada’s food system given the growing global demand for high-quality food … ” (2019: p. 7). Collectively, the act to alter the policy’s content in and of itself undermined the meaning production efforts undertaken by AAFC and stakeholders demonstrating the first area Carstensen and Schmidt (2016) point to—where an actor in power exercises their coercive power to promote and impose their ideas.

Last, Power in ideas is concerned with analyzing deeper level ideas and institutional structures that actors subconsciously draw upon and situate their ideas against in order to substantiate their ideas. This level of analysis asks how and why actors seek to depoliticize certain ideas to the point that meaning becomes accepted or forgotten in policy discussions; why certain ideas enjoy more authority than others in structuring (Carstensen and Schmidt, 2016). This type of power is exerted through actors’ subconscious philosophies and sentiments that ultimately shape policy making processes (Campbell, 1998; Schmidt, 2008). Here, analysis of power looks beyond the explicit ideas driving policy and program mandates and looks at the historical underpinnings of institutions that serve to guide or justify what ideas and actions are acceptable and not. This allows for a deeper assessment of constraints placed on policymakers when legitimizing their ideas to others and of elements limiting the range of policy options believed to be acceptable. Although a slow and evolutionary process, actors are constantly reconstructing these structures as they use them to navigate the changing realities in which they are situated (Carstensen, 2011a).

The concept of a national school food program17 in Canada illustrates how institutional factors outweighed ideational power in the development of Food Policy for Canada. The idea of a national school food program in Canada is long lived and supported by stakeholders across the food system. However, as the policy progressed AAFC’s Food Policy Team found that the concept and proposed solutions were underpinned by a variety of issues not previously or adequately attended to in Canada (i.e. food insecurity, local food procurement, infrastructure in schools). Further, most of these issue areas fell outside the traditional domain of AAFC. Specifically, AAFC render school food as social justice policy and this framework could not be easily adopted within the rigid contours of economic policy traditionally executed in the department. In turn, the final 2019 policy document only referenced a national school food program as an ongoing effort: “The Government of Canada will also engage with provinces, territories, and key stakeholder groups to work toward the creation of a National School Food Program” (Government of Canada, 2019b: p. 9). Later in the summer of 2019, AAFC ended up handing the effort of a national school food program over to Economic and Social Development Canada (ESDC), the fourth largest department in the federal government headed by four different Ministers18, with the hopes that such a collaboration and pool of resources could bring the idea of a national school food program to fruition. Collectively, when analyzing the deeper institutional structure that lend to constraint and opportunity for Food Policy for Canada, the historical underpinnings of AAFC guided and justified to state policy actors that a national school food program was not possible under AAFC’s portfolio.

Altogether, identifying and explaining ideational power relation is relevant for the case study of Food Policy for Canada because it helps for better understanding how and why some policy actors and policy paradigms prevail over others. Specifically, how certain policy actors come to exercise ideas and discourses, as well as institutional positions and resources to influence policy development. Power through ideas and power over ideas allowed for the researcher to consider what elements led certain ideas to be effective in influencing policy actors’ normative and cognitive beliefs (direct interaction of actors and foreground abilities). In turn, power in ideas helped with parsing out the already established systems of knowledge and discursive practices in institutional settings which shaped what ideas were given attention over others (background abilities and deeper subconscious forces at play).

Brining in Regulative Organization Analysis for Explaining Ideational Power Relations

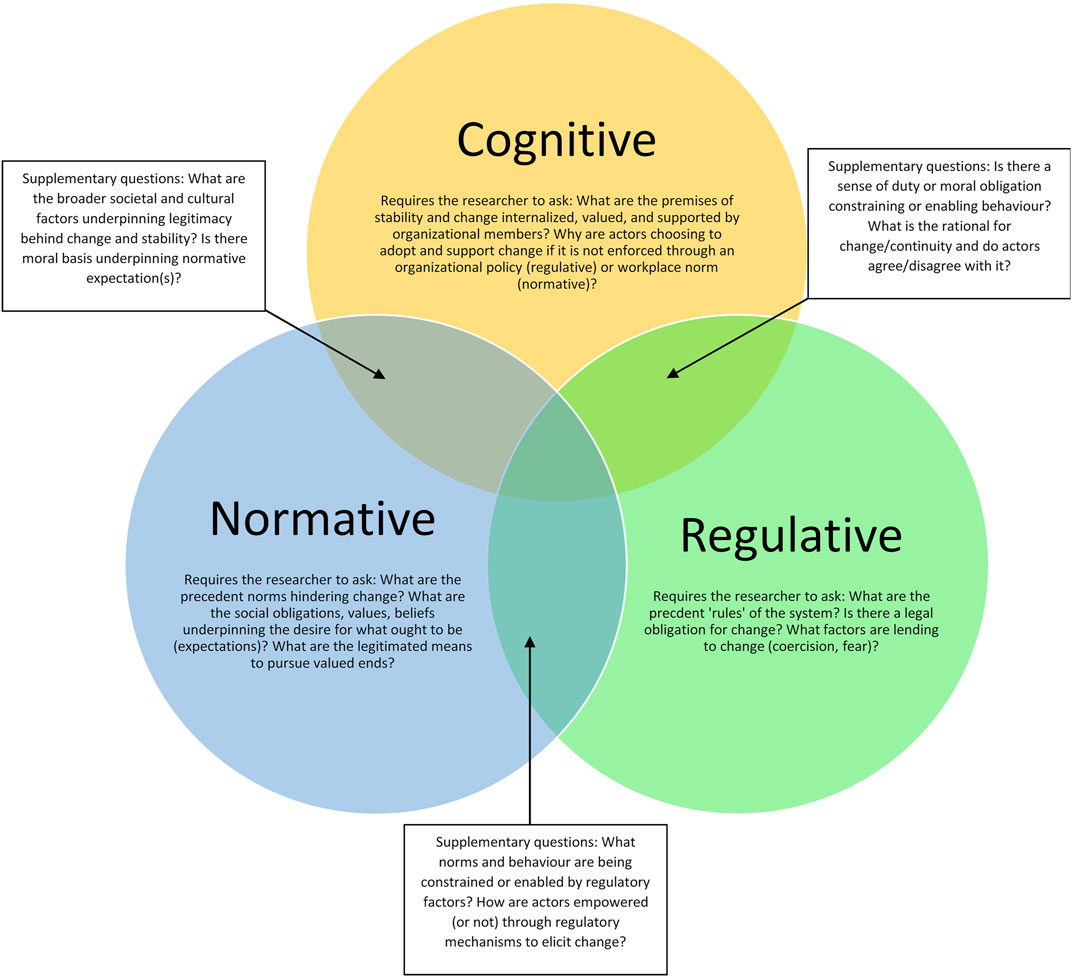

Adopting the DI framework places emphasis on ideas as causal forces ahead of institutional constructs. In some instances, the data “fit” within the DI framework demonstrating that particular ideas held more power in the decision-making process than institutional factors. However, the data also revealed powerful influence derived from regulatory facets, which DI literature does not adequately explain. In hindsight, placing a pronounced focus on the cognitive elements of ideas and less attention to the normative and regulatory elements of institutions made it challenging to untangle and comprehend the competing or simultaneous layers of ideational power relations (power through ideas, power over ideas, power in ideas) that came to shape the final policy document. On one hand, this is beneficial because DI does not funnel food policy researchers towards specific institutional areas of study, and this provides for flexibility and adaptability of framework. On the other hand, however, where the regulatory elements hold profound influence on ideation power it is necessary for researchers to bring analytical questions about regulative elements. Doing so lends to a more holist and thorough approach for analyzing different institutional factors impacting ideation and discursive power in food policy development. As a remedy, it is recommended that those using the DI framework should reflect the contours of regulative organization, drawn from public administration and management literature, in order to orchestrate deeper analysis across cognitive, normative, and regulatory elements of policy development (Figure 2.)

FIGURE 2. Considering the cognitive, normative, and regulative elements lending to ideational and institutional power dynamics in food policy development.

Regulative theorists view the organizational changes of a bureaucracy as a fundamental product of regulative organization. Specifically, the impacts on bureaucratic organization, management, and policy and program design are the result of the conflicts and compromises that arise between new and old policy frameworks (Palthe, 2014). As regulative aspects of institutions constrain and shape organizational behavior the role of regulative processes (e.g. rule-based systems of compliance and enforcement mechanisms) can be analyzed as drivers of institutional power and indicators of policy change (Scott, 1981; Meyer and Scott, 1983). Therefore, when studying ideational power dynamics there is also the need to consider if, why, and how convergence of regulative, cognitive, and normative elements in policy development and policy change occur.

Within this literature, the normative perspective points to a sense of duty and moral obligation driving change, usually from broader societal influences. For example, bureaucratic policy actors may feel obligated to alter their behaviour even if they do not identify or agree with the rationale. In turn, deeper analytical questions arise surrounding how actor behaviour is empowered or constrained by regulatory elements. From the cognitive perspective, premise of change requires researchers to look at ideas and values internalized at the individual or smaller group level. For example, bureaucratic policy actors “choose to adopt and support a change because they believe in it and personally want to support it, even if it is not enforced through an organizational policy (regulative) or workplace norm (normative)” (Palthe, 2014: p. 61). Parsing out the regulative, normative, and cognitive factors underpinning policy actor(s) behaviour provides for explanation of legitimacy. Considering the underlying rationale for legitimacy in turn lends to parsing out why and how ideational power and institutions constructs come together to influence policy development. Here deeper analytical questions consider how conflicts between policy frames arise, are disputed, and resolved in the face of changing or continued underlying rational regarding regulative frameworks.

This lens is helpful for understanding how cognitive, normative, and regulative factors effected AAFC Food Policy Team’s communicative and coordinative discourses of food waste19. Prior to 2015 AAFC had paid limited attention to, nor adequately responded to, the issue(s) of food waste. Only through asking why and how food waste was not a policy priority was it explained that the regulative history in AAFC predominantly shaped normative and cognitive behaviour of AAFC policy actors. Specifically, precedent mandates, legislation, policy, and programs in AAFC focused on primary agricultural, processing (including food safety), trade, and in more recent years retail of food products; from AAFC’s perspective, food waste was located in the food supply chain after human consumption and therefore fell outside their domain (an example of power in ideas). Early in the policy’s development (between 2015 and 2016) this perspective made it challenging for the AAFC Food Policy Team to consider food waste as a priority area for AAFC and for Food Policy for Canada. However, as the policy process unfolded, food waste was strongly advocated for by policy actors outside of the state (i.e. The National Zero Waste Council, 2018; Food Secure Canada, 2016; Conference Board of Canada) and became a policy priority under Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC).

The AAFC 2018 What We Heard Report on Food Policy demonstrates that non-state policy actor’s advocacy during the 2017 public consultation pushed food waste into the growing territory of Food Policy for Canada (an example of power through ideas). Specifically, food waste became understood as an integral part of other policy priorities, including: enhancing health and safety by mitigating the spoilage of food before it reaches northern and remote indigenous communities (2019b: p. 17); improving food literacy and labeling of food products for consumers to make informed choices (2019b: p. 18); addressing environmental implications of food production in Canada and redirecting food loss and food waste back into the supply chain as a non-food resource (p. 20). However, when compared to the framing of food waste outlined in the final policy document of Food Policy for Canada (2019b) the specific asks of stakeholders are not directly reflected but instead the overarching objectives of the government to alter existing regulatory elements within the Canadian food supply chain are: “…reducing food waste in Canada by transforming operations for the processing, retail, and food service sectors, and reducing food waste within the federal government” (Food Policy for Canada: Everyone at the Table!, 2019: p. 9). This priority was substantiated by noting Canada’s obligations to fulfill the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 12 (Responsible Production and Consumption): “Target 12.3: By 2030, halve per capita global food waste at the retail and consumer levels and reduce food losses along production and supply chains, including post-harvest losses” (Government of Canada, 2019b: p. 13).

Collectively, it was found that throughout the policy’s development the AAFC Food Policy Team was constantly conflicted between influences of power through ideas and power in ideas. Specifically, the rationale for including food waste as a priority area in the domain of AAFC and Food Policy for Canada was due to another ministerial department already tackling food waste, and less so a reaction to the broader cognitive and normative rationale provided by stakeholders. Specifically, the path dependency of AAFC—the precedent regulative, normative, and cognitive constraints that previously disempowered policy actors to adopt new policy areas—became loosened to incorporate food waste within AAFC’s normative and regulative frameworks. Specifically, the AAFC’s Food Policy Team took the opportunity to work interdepartmentally with the Waste Reduction Management Division within the Plastics and Waste Directorate at ECCC whose efforts specialized on food waste between 2015 and 201920. In turn, the objectives surrounding the concept of food waste found in Food Policy for Canada (2019b) align with content found in ECCC’s 2019 report Taking Stock: Food Waste and Reduction in Canada and with the government’s explicit obligation to reduce food waste under the SDGs.

Collectively, the DI framework emphasizes ideas as causal forces, yet a methodological framework should be designed to remind and allow the researcher to consider how ideas AND institutions come together to affect policy development and change. In order to do so the regulatory aspects of policy making need to be brought to the fore along side normative and cognitive elements in analysis, instead of subsuming regulative elements within normative policy elements. This provides an additional lens of analysis requiring the researcher to ask important questions about how legality influences cognitive and normative elements and vice versa.

Conclusion

The first half of the paper explains how Canada’s patchwork approach to food-related law and policy lacks coherence or a common vision of a healthy, just, and sustainable food system. By considering the historical trajectory of Canadian agriculture and agri-food policy in Canada the paper situates the impetus for using the DI framework. This invites others to consider the impacts of previous policy objectives and how those effect the recent development of Food Policy for Canada.

The latter half of the paper takes a dual trajectory to demonstrate the pliability of DI to food policy research. Specifically, how DI can be used and should be considered in order to develop both theory and information-gathering together, where each informs the other. First, select findings demonstrate that using the DI framework is beneficial for understanding the power underlying discursive effects in policy making—how food policy is understood and shaped by different actors as well as how those ideas are shared in different settings—as well as the material consequences. Second, select findings highlight important considerations and recommendations for adopting the DI framework, demonstrating how the DI framework was tested using the Canadian case study.

Considering the Canadian case study, the preliminary findings point to an overall minimal transformation in the arena of Canadian agri-food policy. However, the discursive effects within and across the stages of policy development, including different policy actors and different policy spaces, do emulate efforts were taken to challenge existing policy frames. Altogether, this paper demonstrates that the logic of communication and its intricate components highlight important elements for unfolding the narrative of Food Policy for Canada. Ultimately DI is necessary for parsing out the policy’s substance and developmental processes that lead to the cognitive and normative elements found in the final policy document.

Broadly, however, this paper also points to important intellectual and practical questions of food policy research. First, without DI what might be a consequence of the research process and findings? Without the DI framework a researcher may not consider the power of ideas as causal forces meaning important insights about the development and maintenance of power hierarchies within and across policy arenas is omitted. This is vital information for academics because DI compliments existing literature that overlaps disciplines providing flexibility for multi-disciplinary research. The case study of Food Policy for Canada compliments Skogstad’s (2008; 2012) work by exploring how agricultural policy paradigms in Canada are connected to but distinct from food policy paradigms—thus lending to multiple disciplines studying the intersection of food and agricultural policy. From a practical perspective, DI helps bring theory and practice together; DI positions researchers to provide detailed explanation of observations and tangible solutions for future food policy efforts to other scholars and practitioners—a step not always considered in the research process.

Second, what are the material consequences?; how can using DI ultimately help shift food policy efforts towards transformative policy making in Canada? For the research process, DI helps with generating focused research questions and encourages depth and detail when explaining material consequences by blending multiple layers of policy and administrative organizational analysis. Specifically, DI focuses researchers’ attention to policy actors’ behaviour and policy environments in order to explain how discursive effects lend to the short- and long-term material consequences of policy development—consequences that demonstrate continuity or change of previous policy-making behaviours. From an institutional perspective this approach can highlight missed opportunities where policy actors can better collaborate to overcome pitfalls of the past—potentially identifying where and why change needs to occur (e.g. aligning ministerial department mandates regarding food policy; establishing a permanent interdepartmental committee on food policy) if the trajectory of Canadian agriculture and agri-food policy is to shift towards more socially just and environmentally conscious efforts based on holistic or joined-up policy making.

In moving forward, a comparison of national food policy discourses with localized and/or international examples would be interesting. Continuing research in Canada, a comparison of food policy discourses within and between provinces and territories and the federal government would help not only identify existing food policy efforts (i.e., generate an inventory of Canadian food policy), but also identify how and why specific institutional bodies can proactively collaborate to produce effective food policy in the future. Further, identifying similarities and differences in how and why food policy development occurs in Canada, the United States of America, and Mexico could be helpful for navigating future collaborative policy making within and between these countries, especially for shaping trade discourse.

Altogether, adopting the DI framework reflects Simeon’s call of doing theory and practice simultaneously in order to generate rigorous research practices; a framework offering many benefits to those interested in the discursive effects and material consequences observed through food policy analysis.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusion of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by The Carleton University Research Ethics Board-A (CUREB-A) Ethics Clearance ID: Project # 106467. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

MC, the sole contributor to the conception and design of the study. as well as organized and performed the analysis, wrote the draft and attended to all revisions, read, and approved the submitted version.

Funding

The dissertation research referenced in this paper is funded by the FLEdGE (Food, Locally Embedded, Globally Engaged) research and knowledge sharing partnership hosted at the Laurier Centre for Sustainable Food Systems at Wilfrid Laurier University. FLEdGE is funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) Partnership Grant #895-2015-1016. Researchers are committed to fostering food systems that are socially just, ecologically regenerative, economically localized and that engage citizens. The research is based on principles of integration, scaling up and innovative governance with projects exploring the current and potential role of community and regional food initiatives for transformative food systems. For more, visit https://fledgeresearch.ca/about.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Vandna Bhatia and Irena Knezevic for providing comment of the early draft.

Footnotes

1Wicked policy problems are issue in policy and planning, at any level, that are difficult if not impossible to solve (Head and Alford, 2015). They cross multiple policy domains, stakeholders, levels of government and jurisdictions with each brining in different views, priorities, values, cultural and political backgrounds and championing alternative solutions (Weber and Khademain, 2008).

2The term policy actor is used to identify both state actors (political and bureaucratic) and non state actors (stakeholders from across the food system) active in policy development

3MacRae (2011) argues food policy must be designed and implemented to reflect our biological and social dependence on food and the resources needed to produce it in a sustainable manner

4In more recent work MacRae elaborates the argument by urging that change must occur through joined-up policy, a concept leaning on elements of policy integration and reflects an ecological public health approach to food policy: “…coherent and comprehensive policy environment that links food system function and behaviour to the higher order goals of health promotion and environmental sustainability. A joined-up policy unites activities across all pertinent domains, scales, actors, and jurisdictions. It employs a wide range of tools and governance structures to deliver these goals, including sub-policies, legislation, regulations, regulatory protocols and directives, programs, educational mechanisms, taxes or tax incentives, and changes to the loci of decision making” (2016: p.141).

5Situated from a European perspective, Lang, Barling and Caraher (2009) advocate for an integrated approach to addressing food and nutrition-related health issues. They argue for food policies at multiple, interrelated, levels of governance based on the fundamental principles of ecological public health. This approach brings insights from complexity theory and systems dynamics, to encourage the open debate and pursuit of social values and embrace of interdisciplinarity as well as multi-actor approaches to address health challenges (Lang and Rayner, 2012).

6Food insecurity is the “inability to acquire or consume an adequate diet quality or sufficient quantity of food in socially acceptable ways, or the uncertainty that one will be able to do so” (Health Canada, 2021).

7Centralization is described as a trend toward increasing the powers of a central government as opposed to regional and local governments (Scott, 1981). In comparison, decentralization is the delegation of state power and authority to subordinate agencies and actors

8Interdepartmental coordination is the “coordination and management of a set of activities between two or more organizational units, where the units in question do not have hierarchical control over each other and where the aim is to generate outcomes that cannot be achieved by units working in isolation” (Bakvis and Julliett, 2004: p.9).

9Normative ideas or elements are those which appeal to a logic or value of appropriateness (March and Olsen, 1989; Schmidt, 2000). These ideas constitute institutional change as a product of preferred behaviour and expectations which ultimately specify how things should be done (Palthe, 2014). Normative elements include: 1) the process by which an idea comes to the fore, makes it onto the policy agenda, and how it is perceived by interested parties; 2) asking what underpinning aspects shape the particular explanation of the idea; and 3) identifying if certain actors hold legitimate authority in attending to the issue

10Cognitive ideas are conceptual interest and necessity-based beliefs, usually orchestrated through shared meaning making when an institution undergoes change (Hall, 1993; Schmidt, 2002). DI theorists emphasize change is internalized by institutional actors and culturally supported (Palthe, 2014). Cognitive or logical analysis considers where particular foreground ideas and strategies for actions come from (e.g. previous experience) as well as asking what types of background ideas are rendered legitimate and relevant for solving the issue (Bhatia and Coleman, 2003).

11From an institutional standpoint, this context usually reflects activity within the state (e.g. within the bureaucracy and across ministerial departments and agencies). However, societal actors (e.g. advocacy groups, academics, businesses) are also active in shaping policy and therefore the policy sphere can reach beyond the physical settings of government buildings and include actors beyond the state

12FLEdGE is a research and knowledge sharing partnership hosted at the Laurier Centre for Sustainable Food Systems at Wilfrid Laurier University. Researchers are committed to fostering food systems that are socially just, ecologically regenerative, economically localized and that engage citizens. Research is based on principles of integration, scaling up and innovative governance with projects exploring the current and potential role of community and regional food initiatives for transformative food systems. For more, visit https://fledgeresearch.ca/about.

13Ethics was passed March 13, 2017 under the title FLEdGE: The Pan-Canadian Food Policy Project

14Of the 58 interviews 23 occurred with state actors and 35 occurred with non-state actors. This number reflects both initial interviews (46) and follow up interviews (12).

15This document highlights four themes or pillars, deemed from the perspective of AAFC’s food policy team in 2016, as central to Food Policy for Canada. This document has since been removed from Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada’s website but can be access via Food Secure Canada

16This document provides reflection of what was heard in the public consultations which took place between May 31, 2017 and September 31, 2017

17A National School Lunch Program is a government orchestrated meal program operating providing nutritionally balanced, low-cost or free food options to children and youth in schools and childcare institutions

18ESDC falls under the mandates and oversight of the Minsters of: (a) Employment, Workforce Development and Disability Inclusion, (b) Families, Children and Social development, (c) Labour, and (d) Seniors

19The National Zero Waste Council, a prominent advocate against food waste in Canada during the development of Food Policy for Canada, defined food waste as “the loss of edible food and inedible food parts at the point of retail or consumer use” (2018: p.6). In comparison, food lost occurs in the stages between production and distribution, (e.g. food spoiled as a result of production and processing technologies). Food Loss and Waste (FLW) is used throughout this strategy. In some instances, food waste encompasses both loss and waste throughout the supply chain

20The efforts around food waste within ECCC precede the 2015–2019 period. However, the 2015–2019 period reflects the active communication and coordination efforts that aligned the focus on food waste across the ECCC report Taking Stock: Food Waste and Reduction in Canada (2018) and AAFC Food Policy for Canada (2019).

References

Anderson, W. J. (1967). Agricultural Policy in Perspective. Ottawa, ON: Agriculture Economics Research Council of Canada.

Andrée, P., Coulas, M., and Ballamingie, P. (2018). Governance recommendations from forty years of national food policy development in Canada and beyond. Canadian Food Studies 5, 6–27. doi:10.15353/cfs-rcea.v5i3.283

Bakvis, H., and Brown, D. (2010). Policy Coordination in Federal Systems: Comparing Intergovernmental Processes and Outcomes in Canada and the United States. J. Federalism 40, 3484–3507. doi:10.1093/publis/pjq01110.1093/publius/pjq011

Bakvis, H., and Juillet, L. (2004). The Horizontal Challenge: Line Departments, Central Agencies and Leadership. [Government Publication]. [Ottawa (ON)]. Canada School of Public Service. Available at: https://publications.gc.ca/collections/Collection/SC103-1-2004E.pdf.

Bakvis, H., and Skogstad, G. (2020). Canadian Federalism: Performance, Effectiveness, and Legitimacy. Fourth Edition. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Barling, D., Lang, T., and Caraher, M. (2002). Joined-up Food Policy? the Trials of Governance, Public Policy and the Food System. Social Pol. Admin 36, 6556–6574. doi:10.1111/1467-9515.t01-1-00304