95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Commun. , 13 September 2021

Sec. Psychology of Language

Volume 6 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomm.2021.730914

This article is part of the Research Topic Variability in Language Predictions: Assessing the Influence of Speaker, Text and Experimental Method View all 11 articles

German and French football language display tense-aspect-mood (TAM) forms which differ from the TAM use in other genres. In German football talk, the present indicative may replace the pluperfect subjunctive. In French reports of football matches, the imperfective past may occur instead of a perfective past tense-aspect form. We argue that the two phenomena share a functional core and are licensed in the same way, which is a direct result of the genre they occur in. More precisely, football match reports adhere to a precise script and specific events are temporally determined in terms of objective time. This allows speakers to exploit a secondary function of TAM forms, namely, they shift the temporal perspective. We argue that it is on the grounds of the genre that comprehenders predict the deviating forms and are also able to decode them. In various corpus studies, we explore the functioning of these phenomena in order to gain insights into their distribution, grammaticalization and their functioning in discourse. Relevant factors are Aktionsart properties, rhetorical relations and their interaction with other TAM forms. This allows us to discuss coping mechanisms on the part of the comprehender. We broaden our understanding of the phenomena, which have only been partly covered for French and up to now seem to have been ignored in German.

German and French football language features tense-aspect-mood (TAM) forms which deviate from the TAM use in similar structural environments in other genres. We set out to investigate these phenomena in depth using various online corpora. Both phenomena are verbal in nature. They also share the property that the form used lacks a relevant feature which, by contrast, a competing form would express. However, they differ with respect to the relevant referential domain and therefore also in terms of the paradigmatic position of the forms in the language system. On the one hand, in German football language, the present indicative may take the place of the pluperfect subjunctive, which impacts the world reference coordinate. On the other hand, French football reports contain uses of the imperfective past tense-aspect form (imparfait) expressing sequences of events which would be realized by a perfective past in other genres. The deviation is thus located on the level of temporal reference. Although one might suspect erroneous interpretations in terms of truth values (for German) and temporal sequentiality (for French), the deviating forms do not seem to pose difficulties for comprehenders. The phenomena share strong functional parallels. Therefore, a combined analysis is highly fruitful. A particular benefit concerns our understanding of their licensing, which, according to our account, is rooted in the genre they appear in.

The analysis of the two languages indicates that it is specifically the genre which enables speakers to interpret the conflicting forms correctly. We argue that due to the properties of the genre, the precise semantic and script-based expectations outweigh the effect of the deviating TAM forms. Football reports are special in several respects. There is a reduced set of typical events, they adhere to a well-entrenched script, and the events referred to may also be temporally determined in terms of an objective time line. We argue that these properties allow the speakers to exploit secondary functions of TAM forms. They access the temporal coordinates and shift the temporal perspective (see de Saussure and Sthioul, 1999). Thus, the hypothesis is that in the case of football language, deviating TAM forms are predicted on the grounds of genre.

There has been some work on tense in English football language (see Walker, 2008), and also on the imperfectives occurring in French football language (see Labeau, 2004; Labeau, 2007; Egetenmeyer, In press). By contrast, the German phenomenon does not seem to have been covered in the literature. Furthermore, as we show in the present contribution, the French imperfective may in fact appear as the only inflected verb form in entire newspaper articles on football. Our investigation deepens the understanding of the different phenomena in German and French. On the grounds of several corpus studies with different kinds of data, we carve out the relevant properties and determine how the phenomena function within discourse. In order to achieve this aim, we address five research questions. The first two focus on the quality of the phenomena in the linguistic system. 1) In what kind of texts and contexts do the deviating TAM forms appear and what can we say about their frequency? 2) What is the status of the forms within the given linguistic system? The other three questions relate to the speaker’s intentions and the role of the genre for the decoding of the message on the part of the comprehender. 3) For what reason do speakers apply deviant TAM forms? 4) How do comprehenders cope with the deviating TAM forms and how do they resolve the missing information? 5) Finally, what do these phenomena tell us about predictive language processing?

We proceed as follows. In the next section, we introduce the Theoretical Background. We show in what way the forms in question deviate from the standard TAM use (German Tense-Aspect-Mood Forms: Present Indicative Substituting Pluperfect Subjunctive and French Tense-Aspect-Mood forms: Imperfective Substituting Perfective Past). We discuss the commonalities of the uses (Commonalities: Football Frame and Shifted Perspective Time) and the role of predictions in their decoding (The Role of Predictions and What We Can Learn from the Data). In Materials and Methods, we describe the corpora used in this study and how we approach them. First, we focus on the German data (Collection of German Data in Specialized and Non-Specialized Corpora), then on the French (Collection of French Data in Non-Specialized Corpora). Then the results are presented. We begin with what we found on the Aktionsart of the verbs involved (Aktionsart Properties) and continue with properties pertaining to the discourse level (Discursive Properties). In Discussion, we discuss our results and summarize what we have found regarding the research questions mentioned above. Furthermore, we draw up observations on possible further research.

This section covers the relevant theoretical background necessary to discuss the data of interest properly. This is important for the following reasons. We account for linguistic phenomena in two languages, German and French. The two languages pertain to different language families and the functioning of TAM categories is not identical. The two phenomena are different in nature, concerning mood choice in German and tense-aspect choice in French. However, we approach both of them with the same interest, namely, the role of genre for decoding them. Importantly, they are deviations from the expected forms. As comprehenders understand them without difficulties, we argue that they actually predict such forms to occur in football language. The object of study, especially the German TAM forms of interest, and the way we address the data is to some extent new; for instance, TAM research does not normally include the factor of genre, and therefore needs theoretical backing. Thus, finally, apart from the linguistic phenomena and insights into their commonalities, we also introduce predictive language processing in this section.

The subsections are ordered in the following way. German Tense-Aspect-Mood Forms: Present Indicative Substituting Pluperfect Subjunctive presents the German phenomenon of interest. French Tense-Aspect-Mood forms: Imperfective Substituting Perfective Past continues with the French counterpart. With regard to both languages, we specify the linguistic variety in which the phenomena in question appear. In the first two subsections, we will mention important characteristics. Commonalities: Football Frame and Shifted Perspective Time discusses the common core of the functioning of the German and French phenomena. It shows that they are both licensed by the specific properties of the genre. Thus, the section also motivates why we account for the two very different phenomena in a parallel fashion. The Role of Predictions and What We Can Learn from the Data replenishes the theoretical background with insights into the factor of prediction.

The formal deviation we are interested in with respect to German occurs in conditional clauses with past reference and a counterfactual or irrealis reading. In standard German, this is expressed by means of the pluperfect subjunctive, that is, “das Perfekttempus des Konjunktivs II” (Duden, 2009, p. 517, “the perfect tense of the subjunctive II”). (1) is drawn from the examples presented in Duden (2009, p. 518). Both wäre festgebunden gewesen (“had been tied down”) and hätte durchbohrt (“would have pierced”) are pluperfect subjunctive forms. Example (2), with the conjunction wenn (“if”), is a semantically close alternative.

1) Wäre er festgebunden gewesen, hätte ihn die Stange sicher durchbohrt. (Duden, 2009, p. 518, p. 518).

‘Had he been tied down, the pole would surely have pierced him.’

2) Wenn er festgebunden gewesen wäre, (dann) hätte ihn die Stange sicher durchbohrt.

‘If he had been tied down, (then) the pole would surely have pierced him.’

While not all uses of the forms of the German subjunctive are stable and substitutes may be found, especially in spoken discourse (see Duden, 2009, p. 516 and for instance, Gallmann, 2007 who, however, focuses on morphological reasoning), the TAM use in counterfactual conditional clauses has a distinctive value (see Duden, 2009, p. 518–519, see below). Thus, in order to express counterfactuality, the use of the pluperfect subjunctive is considered “unverzichtbar” (Duden, 2009, p. 540, “indispensable”). However, contrary to this expected standard, present indicative verb forms can be found in counterfactual conditional clauses in German football language (see example (4) below).

Thus, this first puzzle forms part of the realm of modality. According to the basic definition of Palmer (2001, p. 1), “[m]odality is concerned with the status of the proposition that describes the event.” Although the definition has been said to be imprecise (see Salkie, 2009, p. 79), it may serve to emphasize a crucial point, as it does not specify how this status is brought about. In German conditional clauses, the protasis may or may not be introduced by the conjunction wenn (“if”) (see examples (1) and (2) above). The alternatives falls (“if”) and sofern (“provided that”) are not compatible with the counterfactual reading (see Zifonun et al., 1997, p. 2280) and might be used as a test battery. When there is no conjunction, as in example (1), the subordinate clause is realized as a verb-first clause (see Zifonun et al., 1997, p. 2281). The apodosis may but does not have to involve the adverbial dann (“then”) (see example (2)). Although, in general, certain cases of syncretism between indicative and conjunctive exist (see Zifonun et al., 1997, p. 1739–1743), the verbal forms occurring in the protasis and the apodosis indicate the propositional status in a largely unequivocal fashion (see Zifonun et al., 1997, p. 1745–1746). This is a more general phenomenon, which is not restricted to German; for instance, Portner (2009, p. 221–247) discusses the interplay between modality and tense-aspect forms for English. As Zifonun et al. (1997, p. 1745) put it, when there is an indicative in the protasis this may yield a hypothetical reading, but counterfactuality is generally ruled out. As noted, when counterfactuality is attributed to the condition, a pluperfect subjunctive is used in the subordinate clause. This also indicates past reference. Although in this case the main clause often features the same TAM form (see Duden, 2009, p. 518), it may also contain a past subjunctive (called Konjunktiv II or Konjunktiv Präteritum, see Fabricius-Hansen, 1999, p. 131) (see also Zifonun et al., 1997, p. 1745–1746). However, this alters the temporal reference. Declerck (2011, p. 28) calls this phenomenon ““[m]odal backshifting” (or “formal distancing”).” Importantly, its functioning differs from the backshifting of verb forms found in indirect speech, and therefore should not be confused with it (see Declerck, 2011, p. 28; Duden, 2009, p. 516–541). Zifonun et al. (1997, p. 1746) present the following example.

3) Wenn die Sängerin gelächelt hätte, {wären wir glücklich/wären wir glücklich gewesen}. (Zifonun et al., 1997, p. 1746, adapted)

‘If the singer had smiled, we {would be/would have been} happy.’

If we focus on the apodosis in (3), the first variant yields a co-temporal reference with regard to the moment of speech, while the preferred reading of the second possibility is one of past reference (see Leirbukt, 2008, discussed below). Still, Zifonun et al. (1997, p. 1747–1748) mention the less typical possibility that a counterfactual reading may arise with mixed forms in which one half of the structure contains a past subjunctive form while the other shows an indicative. However, as becomes apparent in the examples cited in Zifonun et al. (1997, p. 1747), a strong contextual determination is necessary and the structure appears to be marked.

In his introductory section, Leirbukt (2008, p. 1–6) presents the various possible ways of expressing potentiality and counterfactuality in German. As he shows, the distinction is not independent of the temporal localization (see Leirbukt, 2008, p. 1–6). Lewis (1979) takes a philosophical stance and discusses the role the divergence of an invariant past, as opposed to an undetermined and therefore flexible future, has on counterfactuals. Now, as already noted, when the German pluperfect subjunctive occurs in a past context, a counterfactual reading is typically realized; however, it is not the only possibility, as Leirbukt (2008, p. 27 with further references) shows, although he focusses on non-past temporal reference (see Leirbukt, 2008, p. 6).

However, we assume that in general, the argument cannot be inverted. As noted, in order to express a counterfactual reading in the past, the pluperfect subjunctive should be necessary. But football language teaches us otherwise, as example (4) shows. Up to this point, in our inquiry into the research literature, we have neither found reference to the present indicative substituting the pluperfect subjunctive in general, nor to its highly interesting use in football language. Furthermore, we have not come across this phenomenon in French, for which we analyze another phenomenon, as presented in the following section (see Becker, 2014 for a description of mood in Romance languages).

4) Latza […] dachte nach dem 1:1 in der Domstadt an die vergebene Großchance des eingewechselten Teamkollegen Robin Quaison in der letzten der 97 Minuten: „Wenn er den macht, heulen hier 50.000 rum – und wir freuen uns. Schade.” (FR 1)

‘After the 1:1 in Cologne, Latza thought about the missed big chance of the substitute teammate Robin Quaison in the last of the 97 minutes: “If he had converted (lit.: converts) that one, 50,000 people would have cried (lit.: cry) with disappointment—and we would have been (lit.: are) happy. Too bad.”’

As the example shows, a clearly counterfactual proposition is conveyed by means of verbs marked by the present indicative in both the protasis and the apodosis of the conditional clause. To our knowledge, beyond football language this is ruled out. Crucially, the use shows a tendency towards being an oral phenomenon. However, as shown by the above example and example (5) below, it is brought into the written form within direct quotes. Furthermore, in our analysis, we found cases from live tickers, a written (but close-to-speech) variety (see Discursive Properties). In example (4), the occurrence shows two further markers of genre and sociolinguistic status, namely, the structure in the protasis (den machen, “convert that one”) is a typical expression in the realm of football, with a noticeable marker for the language of proximity in the terms of Koch and Oesterreicher (2011). Furthermore, the apodosis features the verb rumheulen (“whine”), which is marked as colloquial. According to our data, example (4) may be seen as a quite typical instance of the phenomenon. Among the factors to discuss are the following. The protasis features a telic event expression (den machen, “convert that one”). The apodosis expresses an activity (rumheulen, “whine”) (and an additional state, freuen, “are happy”). They show a rhetorical relation of consequence (see Asher and Lascarides, 2003, p. 169), which may be considered less typical.

However, apart from the genre restriction, the phenomenon is versatile. Most importantly, it has two different syntactic instantiations paralleling the introductory examples (1) and (2). The second type is exemplified in example (5), where the protasis lacking the conjunction wenn (“if”) is realized as a verb-first sentence (see Zifonun et al., 1997, p. 2281). Following the apodosis, another consequence of the situation expressed by the conditional clause is expressed. Interestingly, the speaker switches to the pluperfect subjunctive (wären gelaufen, “would have gone”). The switch underlines that the speaker is well aware of the counterfactual meaning of his own words. Apparently, the standard TAM form expressing this kind of world reference is available as an alternative.

5) [D]er Innenverteidiger, der sich noch immer über seine vergebene Kopfballchance im letzten WM-Gruppenspiel gegen Südkorea ärgert[, sagte]: „Mache ich das Tor, kommen wir gegen Südkorea weiter, dann wären viele Dinge sicherlich anders gelaufen.“ (Spiegel 1).

‘The central defender, who is still upset about his missed header chance in the final World Cup group match against South Korea, said: “If I had scored (lit.: score), we would have succeeded (lit.: succeed) against South Korea to the next round, then many things would probably have gone differently.”’

However, as our final example (6) indicates, a speaker may also continue with the present indicative when expressing a further consequence. This example comes from a live commentary. It underlines two important properties of this use especially clearly. First, it indicates grammatically (wär’ gewesen, “would have been”) and lexically (Theorie, Theorie, Theorie, “theory, theory, theory”) that reference is made to a counterfactual situation. Second, it excludes a generalizing meaning, as reference is made to a specific event in which a player (Volland) did not get the pass he was supposed to get. As the feature of specific reference is an important property of the structure investigated here, it is also given in examples (4) and (5). However, in (4) and (5) the referential status is not determined by the same speaker, but rather by the author of the article, while the structure of interest is part of a direct quote of an interviewee. By contrast, in example (6), there is only one speaker. As noted, in the sentence following the conditional structure, the speaker goes on to speak of a further consequence the successful pass would have had and maintains the present tense.

(6) Und das wär’ das Tor gewesen. Theorie, Theorie, Theorie, noch ist nicht Schluss. Kommt der Ball, kann Volland den machen. Dann heißt der Gegner nicht England, sondern Schweiz. Aber die Uhr tickt noch (ZDF 1).

‘And that would have been the goal. Theory, theory, theory, it’s not over yet. If the ball had gotten (lit.: gets) to him, Volland could have scored (lit.: can score). Then the opponent would not have been (lit.: is not) England, but Switzerland. But the clock is still ticking.’

In classic literary French, two main past tense forms are used which express the aspectual distinction between perfective (passé simple) and imperfective (imparfait). Diachronically speaking, the passé simple has been extensively substituted in oral discourse and, to a certain extent, also in written discourse by the compound past (passé composé) (see Verkuyl et al., 2004, p. 253, 265–266). However, the opposition with the imperfective past is maintained (see Molendijk et al., 2004, p. 298; refinements can be found, however, in Facques, 2002). Thus, typically, series of past events are expressed by the simple past or the compound past, while the imperfective past tense-aspect form is used for co-occurring or background eventualities (see Weinrich, 1964; Kamp and Rohrer, 1983). However, in certain contexts, the imperfective past may be used instead of its perfective counterpart. This phenomenon is often called the imparfait narratif (“narrative imperfect”; see Gosselin, 1999; Bres, 2005; and others). Importantly, such occurrences are quite restricted in terms of syntactic, contextual and genre-related terms (see Caudal, submitted; Egetenmeyer, In press). Apart from literary texts and newspaper articles on politics (see Egetenmeyer, In press), we also find football reports among the genres which feature such imperfective tense-aspect uses (see Labeau, 2007, p. 220 who quotes Herzog, 1981, p. 67 as having noted the distribution quite early). Importantly, as Egetenmeyer, In press underlines, its use in football reports is peculiar: It is the only genre which seems to allow for a full substitution of non-imperfective tense-aspect forms with the imperfective (however, see Facques, 2002, p. 115 for an example coming from a non-football related newspaper article which also shows a rather strong tendency to avoid non-imperfective tense-aspect forms). An important differentiating property is that while the typical narrative imperfect is normally embedded under an adverbial expression (see Vetters, 1996, p. 128), as shown in example (7), in football reports explicit reference to times may be dropped entirely.

7) Quinze jours plus tard, lady Burbury qui résidait en compagnie de son époux dans leur domaine de Burbury,s’éprenaitd’un jeune pasteur des environs, venu déjeuner au château. (Aymé, 1968, p. 38, cited after Tasmowski-De Ryck, 1985, p. 60, p. 60).

‘A fortnight later, Lady Burbury, who was residing with her husband at their Burbury estate, fell in love with a young clergyman from the area who had come to lunch at the castle.’

In (7), the adverbial expression quinze jours plus tard (“a fortnight later”) introduces a (relative) time point at which the event of falling in love (s’éprendre) is realized. As Egetenmeyer (In press) shows, this factor, along with other properties, restricts the use in comparison with the one found in football reports. Interestingly, whole reports of football matches may be written using the imparfait where otherwise perfective (or non-imperfective) tense-aspect forms would be used. When comparing the situation with Spanish, which shows many parallels in the use of the corresponding imperfective past (see Escandell-Vidal, submitted with further references), we find that the usage in question is not paralleled there. For instance, as Quintero Ramírez and Carvajal Carvajal (2017, p. 229) indicate, in Mexican Spanish newspaper reports the imperfect past tense is not used to express sequences of eventualities.

Example (8), taken from Egetenmeyer (In press), is the beginning of a newspaper article reporting a football match. All five finite verb forms would be expected to be realized as compound past forms due to the expression of sequences of events. However, they are all marked by the imperfective, as are most of the other finite verbs in the rest of the article (see Egetenmeyer, In press).

8) [1] Le Blésois Gonçalvesétaitle premier à se mettre en action (10e), [2] mais sa frappepassaitjuste à côté. [3] Les locauxrépondaientde suite, avec une bonne tête de Maelbrancke, [4] mais le défenseur Radetsauvaitsur sa ligne. [5] La réponse blésoise ne sefaisaitpas attendre […]. (Sketch Engine: La Nouvelle République, 22.08.2016)

‘[1] The Blesoisian Gonçalves was the first one to get into gear (10th), [2] but his shot just missed. [3] The locals responded immediately with a good header by Maelbrancke, [4] but the defender Radet saved on the line. [5] The Blesoisian answer was not long in coming.’

As we will see, in such structures, there is a high proportion of verbs lexically expressing boundedness (see also Bres, 1999, p. 5), which we assume facilitates processing. As noted above, the specialty of this usage is that no temporal determination is necessary in order to license it (see Egetenmeyer, In press). This contrasts with other similar uses, such as the typical narrative imperfect, which tends to co-occur with a temporal sentence adverbial under which it is embedded (see Egetenmeyer, In press), but also uses appearing in relative clauses (see Caudal, submitted, who analyzes the examples in Bres, 2005). Those types of uses show a direct or indirect temporal determination of the expressed eventuality. It should be mentioned, however, that the above example does in fact contain an explicit (relative) temporal indication, namely, “10e [minute]” (“10th minute”). In terms of discourse structure, it is relevant to note that the indication is realized as an insertion and is therefore not syntactically integrated into the sentence. As our data show, such an indication is not necessary for the usage. However, as discussed in the following subsection, it makes a principle explicit which we assume to be relevant for the occurrence of imperfective tense-aspect forms in football reports, namely that it shows that a football match is measured in terms of an objective time. In addition to this principle, possible temporal indications and temporal adverbs, as well as verb meaning (in terms of and beyond Aktionsart), support the decoding of temporal relationships when distinctive grammatical means are not available. It should be noted that not all imperfective forms occurring in football reports have the same function (see Discursive Properties). For instance, the imperfective verbs may lack narrative features altogether. By contrast, there may also be instances of the typical narrative imperfect, although this is not frequent.

In example (9), a temporal specification is only given in the case of a decisive event within the match (see clause [5]). The adverbial expression (la 21e(minute), “the 21st minute”) is syntactically integrated into the discourse. Furthermore, clause [4] includes an adverb (puis, “then”), which typically expresses a sequence and may therefore be considered a relevant tool in contexts lacking grammatical markers of sequentiality as in the phenomenon at hand. However, in the example, it does not strictly express a sequence but has additive meaning. In terms of rhetorical relations, clauses [2] to [4] are an elaboration with regard to [1] (see Jasinskaja and Karagjosova, 2020, for subordinating rhetorical relations). Although the order of mention is meaningful, only the events expressed in [2] and [3] are temporally adjacent, not those of [3] and [4]. Thus, the example underlines the temporal flexibility of the imperfect in football reports.

9) [1] Les Malouins semontraientles plus entreprenants, [2] Desmeneztiraitun corner dangereux [3] quicontraignaitShungu, le portier visiteur à s’imposer [4] puis un coup franc de Desmenezmettaiten diffficulté Shungu. [5] Ilfallaitattendre la 21epour voir une première offensive des visiteurs grâce à son attaquant Orhand [6] quiobligeaitFavris, le gardien local à se détendre. (Emolex: Ouest-France, 19.03.2007).

‘[1] The Malouins showed themselves as more enterprising, [2] Desmenez shot a dangerous corner [3] that forced Shungu, the visiting keeper, to come forward [4] and then a free kick from Desmenez challenged Shungu. [5] It was necessary to wait until the 21st minute to see a first offensive of the visitors thanks to their forward Orhand [6] who forced Favris, the local keeper, to reach out.’

Finally, when the report is reduced to the most important events in very brief match presentations, the temporal specifications may be indicated regularly, as in example (10). In this example, the temporal indications are again introduced within the inserted brackets and are not syntactically integrated into the discourse.

10) [1] Pour ses grands débuts sur le banc de Montpellier, Frédéric Hantzétaitservi. [2] Après un débordement de Martin, Yatabaréouvraitla marque à bout portant (15e). [3] Martinmarquaitensuite le but du break sur penalty (41e) [4] et Daboclouaitenfin le spectacle avec un doublé face à un Ajaccio méconnaissable (53eet 58e) (Sketch Engine: Foot01.com, 369844001).

‘[1] For his big debut on the Montpellier bench, Frederic Hantz was served. [2] After a cross attack by Martin, Yatabaré opened the score from close range (15th). [3] Martin then scored the breakthrough goal from the penalty spot (41st) [4] and Dabo finally closed the show with a double against an unrecognizable Ajaccio (53rd and 58th).’

The two preceding subsections introduced the basic characteristics of the phenomena of interest. While the phenomena show certain parallels, they are also different in important respects. They share the basic property of pertaining to the verbal domain. In both languages, the TAM marking deviates from what would be expected in a different genre. Simply put, the marking would not withstand a normative stance. By contrast, an important difference is that the German TAM marking deviates in the realm of world reference, while the French counterpart shows its deviation with regard to temporal reference. Finally, they share two decisive properties, which also motivate their joint treatment. First, an important licensing factor for their realization, which is directly connected with the factor of genre, is given by the frame or the script of football matches. Second, the functioning of both phenomena can be explained as a shift in perspective time. In the following, we go into the details of these last two ideas.

A football match is conventionalized and functions according to a specific set of rules, of which at least the basic ones are known to the general public in the speech communities relevant for this paper (see also the interesting properties ascribed to football reports in newspapers by Engel and Labeau, 2005, p. 204–205, with reference to Grevisse, 1997, some of which, however, would need sociological verification; in addition, see Hennig, 2000, p. 43–44, for live football reports on television and radio). Therefore, (at least) the central information block of football language may be taken to show relevant features covered by accounts of scripts (see Schank and Abelson, 1977, p. 36–68) and frames (Fillmore, 1977; Fillmore, 2006). There are three further related properties of football matches which distinguish them, for instance, from the often-cited restaurant script. First, the non-generalized events of the football match are directly related to an objective time line. In a related matter, Engel and Labeau (2005, p. 215, with further references) remark that in football reports the events are often presented chronologically. Second, the matches of interest to a large group of people are televised. The large group of passive participants (i.e., viewers) and the factor of television broadcast further objectivizes the match, as there are many witnesses and the match can be (and is, in fact) recorded to be watched again. Importantly, the objective temporal determination of specific events is not circumstantial, but plays a decisive role for the match. For instance, it may have consequences for tactical planning. Furthermore, due to its role within the match, it has a high informative value in football reports and many other situations where football language is used. These very specific temporal properties have an influence on what needs to be conveyed in a relevant speech situation. We assume that it is due to such properties that the rigidity of certain components of the linguistic system may be attenuated. As a consequence, other functions may be exploited. As we will see, both languages make use of this principle in a similar way, although they diverge in terms of what exactly is modified.

In terms of discourse structural functioning (see Becker and Egetenmeyer, 2018 for our conception of temporal discourse structure), the two phenomena adhere to the same principle, namely, they show a shift in temporal perspective. For the French narrative imperfect, this has been discussed in a similar vein by Berthonneau and Kleiber (1999), de Saussure and Sthioul (1999) and Schrott (2012). Further relevant discussions come from the realm of free indirect discourse (see, for instance, Banfield, 1982; Ehrlich, 1990; and Eckardt, 2014; distinctions between different forms of perspective taking are presented in Hinterwimmer, 2017). Labeau (2006) mentions perspective specifically in the context of television talk, a category to which the genre of football reports partly pertains. According to Becker and Egetenmeyer, 2018, p. 37, with reference to Guéron, 2015, p. 278), the perspective time “is the point in time where the text-internal origo is situated.” While, in a standard narration of successive events expressed by means of verbs marked with the perfective past, the perspective time is anchored to the speech time, the eventive use of the imparfait in football reports is accompanied and licensed by a shift in perspective to the past. In terms of de Saussure and Sthioul (1999, p. 6), the perspective time is included in the run time of the event, which, however, may be determined more precisely as the location time corresponding to the event (see Becker and Egetenmeyer, 2018). With regard to football language, we have to keep in mind a further component which seems to be missing in the above-mentioned publications, namely, that this perspective time needs to be continuously updated as the events are narrated one after the other by means of verbs marked by the imparfait. A similar principle is described by De Swart (2007, p. 2282) with regard to the special use of the French present perfect in Camus’ L’Étranger, which, according to her, is mirrored by the adverbials used in the text. Schrott (2012) emphasizes the underlying perception of the perspectivizing entity with the narrative imparfait. Envisioned in this way, this use of the imparfait could be understood as a means to bring the report closer to the speaker / hearer and thereby to render it livelier (see, however, Labeau, 2007, p. 220, who notes that the literary narrative imparfait with a temporal adverbial tends to render a passage rather clumsy). In this way, an (intended) immediacy of the experience is conveyed (see also below). The actualization of the secondary (competing) perspectivizing function in the footballer’s context might also be applied to the English narrative present perfect, described in the football context by Walker (2008), and even to the use of the present perfect in Australian police reports (see Ritz, 2010). These two publications, however, do not mention this interpretation.

Although the German phenomenon we are interested in does not pertain to the realm of tense-aspect but to the modal domain, it may also be interpreted in this way. In this interpretation, the speaker shifts the temporal perspective to a past reference time, which, as we saw above, may correlate with a distinct objective time. From this past perspective time, the expressed event is posterior; that is, it is a kind of future in the past. Correspondingly, conceptualized from this perspective time, the realization of the event is still possible. The present indicative is then the corresponding TAM choice. Thus, even more clearly than in French, the effect of an immediacy of the experience in operationalized. An important clue to substantiate our hypothesis is, as we will see, that the collected instances all pertain to oral or close-to-speech varieties (see Discursive Properties) (see Wüest, 1993, p. 231 for the varying strength of correlation between temporal perspectivization and text types). We have already noted above that the phenomena at hand make use of secondary functions of the linguistic forms. In oral speech, exploiting the potential of flexibility of language is even more common (see also Labeau, 2006, p. 18–19).

When processing language, comprehenders partly resort to prestored knowledge in order to predict what is to come next (see Kuperberg and Jaeger, 2015 for a theoretical overview). Thus, prestored knowledge has an important function in communication. As Kuperberg (2013, p. 14) underlines, the “benefit of a predictive language processing architecture is comprehension efficiency.” It may also be calculated, as shown, for instance, by Levy (2008), who focusses on surprisal (that is, basically, when predictions are not met). The research in the realm of predictions frequently discusses verbal properties and also touches upon the role of genre (see below). Importantly, as we will indicate below, we suggest an alternative way of approaching the phenomena, which takes genre to be a predictor of deviating TAM forms. Addressed in this way, football language is an especially revealing case. The analysis of corpus data containing the phenomena in question is also a basis from which future experimental research may profit.

As discussed in the preceding sub-sections, the analyzed structures deviate from otherwise expected ones. This is especially interesting against the backdrop of predictive language processing. First, we might be inclined to ask how speakers would deal with deviating TAM forms if they interpreted them as errors. Hanulíková et al. (2012) indicate that when confronted with speakers with non-perfect acquisition of an L2, hearers do not show any reaction to syntactic errors (no P600 effect). Kuperberg (2013, p. 17) calls this “predictive error-based learning.” One might be inclined to think that the same is happening in the case of the deviating TAM forms in football language. There are two main arguments against this view. First, as already indicated, the phenomena of interest are not extremely rare. Second, journalists and reporters are not completely free in their linguistic choices. We may assume that their employers would refuse to accept an overly individual or defective style of speaking or writing. By contrast, the use of a specific diastratical marking in order to indicate pertinence to a group (see Koch and Oesterreicher, 2011), such as the group of football fans, may be permissible or even desirable in order to reach a high number of listeners or readers. However, idiosyncratic markers should never be too strong, in the sense that the content of the utterance still needs to be comprehensible to the general public. This is another argument favoring licensing effects, as discussed in Commonalities: Football Frame and Shifted Perspective Time. Again, if a hearer/reader were to incur processing difficulties every time she/he is confronted with a non-standard TAM form, the form would quickly be banned from the genre it appears in. By contrast, as the phenomena in question are frequent in football speech, they cannot be expected to be overly costly in terms of the comprehenders’ processing. Rather, we assume a genre-based prediction that such TAM forms will occur.

What do we know about the role of TAM forms in predictive language? In the research literature, verbal properties are shown to play a crucial role in the predictive processing of language (see, for instance, Kuperberg and Jaeger, 2015, p. 6–7, and the references therein). Among the best studied verb-related factors are its argument properties, such as its selection restrictions (see Altmann and Kamide, 1999). However, tense and aspect have also been investigated (see Kuperberg and Jaeger, 2015, p. 7; Arai and Keller, 2013, p. 5; both with further references). For instance, Altmann and Kamide (2007) show that the tense-aspect morphology is relevant for predicting the verb’s object. Furthermore, Philipp et al. (2017) discuss the interaction of semantic roles with telicity and event structure with respect to processing costs. Graf et al. (2017) analyze the interaction between verbal (telicity) and nominal (agentivity) features. As a final example, Dery and Koenig (2015) specifically focus on temporal updates. By contrast, mood and modality do not seem to have aroused much interest. However, genre, our second category, has also been studied (see Kuperberg and Jaeger, 2015, p. 16). For instance, according to Fine et al. (2013, p. 15), comprehenders are sensitive to genre and other more individual properties of the input, and they “continuously adapt their syntactic expectations” as they are exposed to new linguistic input. Further evidence can be found in Squires (2019). She discusses insights from several studies underlining that the knowledge of the listener about the speaker in terms of dialect or sociolect positively influences how possible expectation violations are processed (see Squires, 2019, p. 2–4, with further references). More specifically, she presents three experiments concerning the role the genre of pop songs has on the evaluation of non-standard morphosyntactic forms by listeners (see Squires, 2019, p. 8–23). She concludes “that speech genre can serve as an expectation-shifting sociolinguistic cue during sentence processing” (Squires, 2019, p. 23). However, according to Squires, the listeners’ expectations are rather vague with respect to what phenomena might occur and how they deviate from standard language (see Squires, 2019, p. 23).

An important part of the research literature focusses on syntactic or morphological markers as predictors. By contrast, Fine et al. (2013) take syntactic structure as the predicted component. Similarly, we analyze TAM forms as predicted elements. To be precise, we argue that they are predicted on the grounds of the genre they occur in. The relevance of this idea is backed by Kuperberg and Jaeger (2015, p. 4, with reference to Anderson, 1990), who state that a comprehender will “use all her stored probabilistic knowledge, in combination with the preceding context, to process th[e] input.” However, we do not analyze prediction locally, that is, in a sentence-based way, but globally in the sense of the classification of a whole discourse in terms of the subject it covers. We find a similar principle in the study by Schumacher and Avrutin (2011), who analyze the role of a certain discourse type for the processing of article-less noun phrases. The discourse type that they are interested in, a classification for which they use the category term “register” (see Schumacher and Avrutin, 2011, p. 306, footnote 3, for the way they determine it), is that of newspaper headlines. The authors present two studies involving NPs without an article, where the participants are only made aware of the pertinence of the critical items to a headline in one study, not in the other (Schumacher and Avrutin, 2011, p. 307). They show “that awareness of a particular register, and the expectations associated with it, has an impact on the readers’ processing patterns” (Schumacher and Avrutin, 2011, p. 318). On these grounds, we assume that an analysis in our terms is promising.

As its definition is content-based, football language is a broad concept linguistically (see Burkhardt, 2006 for a distinction of three lexically motivated sub-types). Football-related content may be presented in very different situational (for instance, with regard to the aim of the speech or writing event), social (with respect to the speaker/hearer constellation) and medial (concerning the medium) contexts. Typical situations for football language are football news reports on the radio, live commentaries on television (see Hennig, 2000, p. 43–44, for properties distinguishing the two), newspaper articles or printed interviews, but also fans talking among themselves. Thus, the concept of football language needs to capture a possible diversification in terms of diaphasics, diastratics and diamedial realization (see Koch and Oesterreicher, 2011). We assume an oral predominance with regard to the general use of football language, which however, may be taken to be a general property of linguistic data (see Sinclair, 2005, Discussion, who classifies the distribution as a general problem for corpora). However, due to practical issues we restrict ourselves to written data at this point, which may include direct quotes and spoken interviews published in a written format.

An important part of the insights generated comes from the data collection process and the challenges we encountered when retrieving the linguistic material from the corpora. Therefore, the present section goes into further details regarding the data analyzed. It is especially dedicated to the corpus studies we conducted, the factors we considered and how we solved the issues that arose.

In order to understand the phenomena in depth, we collected data from pertinent corpora. In both languages, the linguistic material was annotated upon retrieval. Although the phenomena analyzed, in their core, both boil down to deviant TAM forms, they do not pertain to directly parallel verbal paradigms. Due to the systemic differences, different factors need to be accounted for in their retrieval and in the ensuing analysis. On the one hand, in German, the syntactic structure is relevant, in the sense that the occurrences are combinations of a subordinate and a main clause. However, as the annotations of the corpora we used do not consider syntactic structure, we can only make use of it in the corpus queries in cases where an explicit subordination marker is realized or a specific word order is used (verb-first). By contrast, an implicit subordination is much more difficult to find. On the other hand, in French what is of most interest is basically the re-occurrence of a tense-aspect form in a sequence of sentences. But the information on the quantity of a form within the textual entity it occurs in (the sentence, the paragraph or a text in its entirety) cannot be directly retrieved from a standard online corpus.

An issue beyond the linguistic means of expression is the availability of specialized corpus data, which differed between the two languages. With respect to German, we had specialized corpora at our disposal (see Collection of German Data in Specialized and Non-Specialized Corpora). Interestingly however, relevant examples were not easy to find there, which might be considered a sign of low frequency. By contrast, we did not have specialized French corpora. Therefore, in order to collect the data, we used specific verbs and collocations (see Collection of French Data in Non-Specialized Corpora). Furthermore, as we intended to analyze whole articles in French, we extended the passages retrieved step by step using the corresponding database or through queries on the general internet.

As already noted, the German phenomenon does not seem to have been described in the literature. Therefore, we started off with an unstructured study using the general internet (via www.google.de) in order to determine relevant factors for its occurrence. They concerned the syntactic structure and, more importantly, the relevant verbal types (see below). For the main study, we had corpora at our disposal which specifically contained German football language. Interestingly however, we only found few instances of the phenomenon of interest. Therefore, we additionally used unspecialized corpus data to balance our findings. Finally, we conducted a counter-study in order to test whether there are similar phenomena beyond football language. We analyzed sub-corpora contained in Cosmas II, a database issued by the Leibniz-Institut für Deutsche Sprache (IDS) (https://www2.ids-mannheim.de/cosmas2/). It comprises 570 sub-corpora with a total of 56.5 billion tokens (https://www2.ids-mannheim.de/cosmas2/uebersicht.html, accessed: June 16, 2021). The sub-corpora are organized into eighteen different archives (https://www2.ids-mannheim.de/cosmas2/projekt/referenz/archive.html, accessed: June 16, 2021). Table 1 gives an overview of the studies conducted.

In a first step, we analyzed three sub-corpora of football language, which are contained in the corpus “W - Archiv der geschriebenen Sprache.” The first one is “KSP - Fußball-Spielberichte, kicker.de, 2006–2016.” As the name indicates, it consists of a collection of data from the German football journal Kicker. The other two corpora consist of data from football live tickers. More precisely, the second corpus, “KIC - Fußball-Liveticker, kicker.de, 2006–2016” collects live ticker data coming from the very same journal. The third sub-corpus, “SID - Fußball-Liveticker, Sport-Informations-Dienst, 2010–2016,” contains live ticker data from the biggest German sports news agency (see https://www.journalistenkolleg.de/service/organisationen/sid-sport-informations-dienst, accessed: August 6, 2021). “KSP” and “KIC” each amount to 3,000 texts. However, “KSP” contains 1.9 million tokens, while “KIC” comprises nearly 3.5 million. “SID” contains approximately 1,800 texts with close to 3.8 million tokens. Already in the unstructured pre-study, we found a tendency for an oral predominance. However, there are two reasons why the three sub-corpora appear to be promising despite the fact that they present written texts. First, they may contain direct quotes. Second, the live tickers (KIC and SID) may be said to be rather close to the pole of a language of immediacy on Koch and Oesterreicher’s (2012) scale of linguistic conception.

The corpus research with regard to the three sub-corpora had to be carried out in two steps. The first step exploited an important advantage of Cosmas II, namely that the entries are lemmatized and the corpus allows for relatively complex queries. As discussed in German Tense-Aspect-Mood Forms: Present Indicative Substituting Pluperfect Subjunctive, the forms we are interested in are simple present tense forms (or share the form of the present indicative). As a consequence, we had to deal with a considerable amount of noise. Therefore, in the second step, we went through the hits manually and retrieved the relevant examples in order to analyze them more in depth.

In formulating the corpus queries we took into consideration the two different syntactic possibilities, namely, 1) clauses introduced by an explicit conjunction wenn (“if”), or 2) clauses displaying verb-first word order. For the case of an overt conjunction, we used the query that the verb should follow within a range of five words from the conjunction. We intended the verbal inflection not to be restricted. Thus, we used the query, “wenn /+w5 &verb,” where we filled the verb slot with a specific lexical item (see below). The second query type specified a verb-first clause (see German Tense-Aspect-Mood Forms: Present Indicative Substituting Pluperfect Subjunctive). In Cosmas II, this can be spelled out as “&verb /w0 <sa>,” which determines that the verb should occur as the beginning of a new sentence.

In the previously conducted unstructured analysis using the search engine google (www.google.de), we had intended to find out what verbs may occur in such contexts. There, we used simple co-occurrence patterns of different verbs in the present tense and denotations of individuals typically involved in football activities like Torwart (“goalkeeper”) and Schiedsrichter (“referee”). The findings indicated that at least two factors were relevant. First, we only found verbs expressing typical actions in football matches, especially if they were compatible with rather colloquial football language. Due to its seeming frequency, an appropriate example is machen (“make”) combined with the short demonstrative pronoun (den) in the structure den machen (“to score a goal (as part of a specific opportunity)”). Second, all the verbs we found were telic.

On these grounds we chose nine different verbs for our structured study of the specialized corpora, among them flanken (“to center”), halten (“to stop (a ball); to save a penalty”) and verwandeln (“to convert (for instance, a penalty)”). All of these verbs are typical of football contexts. In the uses we looked for, they are all telic or ingressive and most have a punctual reading. We considered all of them in both syntactic configurations. This led to a total of six relevant hits. The amount of noise was considerable. In “KSP,” there were 423 hits, of which, however, none was relevant. Of the 474 hits in “KIC” only one was relevant. By contrast, in “SID,” there were 380 hits, including the remaining five relevant ones.

In a second step, we chose the sub-corpora of two local newspapers with a relatively high circulation, namely the Kölner Stadt-Anzeiger and the Frankfurter Neue Presse. They both belong to newspaper groups which are often listed among Germany’s top ten regional newspaper groups (see, for instance, for the second quarter of 2019 https://meedia.de/2019/07/22/die-auflagen-bilanz-der-groessten-83-regionalzeitungen-kaum-noch-titel-mit-einem-minus-unter-2/, accessed: June 16, 2021). Both sub-corpora are contained in “W2 - Archiv der geschriebenen Sprache.” “KSA - Kölner-Stadtanzeiger, 2000–2019” contains 20 years of the newspaper, amounting to over two million texts with more than six hundred million tokens. “FNP - Frankfurter Neue Presse, 2000–2020” covers 21 years, close to 2.6 million texts and over seven hundred million tokens. Again, we used both query types presented above, but we reduced the target verbs to four. We chose verbs which had a high probability, in terms of their lexical content, of occurring in football contexts. They express scoring (machen, “to make,” see above, treffen, “to hit,” verwandeln, “to convert”) or saving a goal (halten, “to save”) and are all compatible with a colloquial style. We restricted the study to the first one hundred occurrences per query. However, the structures involving verwandeln (“to convert”) are less frequent and both sub-corpora yielded fewer than one hundred cases per query. The resulting 1,427 hits are comparable to the amount of data from the specialized corpora. In the same vein, the hits were examined manually in order to retrieve the relevant cases. Again, there was a high proportion of noise. However, although the corpus data was not reduced to football content in this case, six of the hits are relevant in our terms. They are distributed evenly, with three examples per sub-corpus. Interestingly, all six instances present direct speech. This matched our expectation based on the preliminary unstructured studies. By contrast, the hits from the live tickers (KIC, SID) were not instances of direct speech; however, given the nature of live tickers, they represent a close-to-speech variety (see Discursive Properties).

Finally, we also conducted a minor counter-study. The aim was to minimize the possibility that the phenomenon could be more pervasive and not restricted to football language. We used a set of four verbs which do not express typical football actions. However, they have comparable properties to the verbs in our football set, namely that they are telic and, due to their semantic content, may easily refer to decisive events within the texts where they appear (see Discussion). We investigated beenden (“to bring to an end”), entscheiden (“to decide”), sterben (“to die”) and unterbrechen (“to interrupt”), and again tested both structures. We used the sub-corpus “ZEIT - Die Zeit, 1953–2020,” included in “W - Archiv der geschriebenen Sprache” of Cosmas II. Die Zeit is the weekly newspaper with the second-highest circulation in Germany (see https://meedia.de/2020/01/17/die-auflagen-bilanz-der-tages-und-wochenzeitungen-bild-und-welt-verlieren-erneut-mehr-als-10-die-zeit-legt-dank-massivem-digital-plus-zu/, accessed: August 6, 2021). We chose the data of this national weekly in order to allow for a wide range of subjects and more varied linguistic structures. The sub-corpus, which covers 68 years, contains close to 388 thousand texts and 343 million tokens. As before, we restricted our study to the first one hundred hits per item, totaling another eight hundred hits. We examined them manually. Importantly however, none of them instantiated the structure of interest.

In contrast to the German data, for French we did not have specific corpora of football language at our disposal. Therefore, we slightly adapted our procedure. We maintained lexical meaning as a central component and also used verbs expressing typical football actions. Furthermore, we made use of collocations (see Lehecka, 2015). We retrieved the relevant hits and their context from the corpora. Furthermore, we augmented the context as much as possible by using queries with strings from the preceding or the following context, either within the database or on the general internet.

The newspaper data investigated with respect to French stem from the two databases Emolex and Sketch Engine. We collected relatively long strings of context as we intended to find out more about the discursive functioning of the narrative imperfect. More specifically, our aim was three-fold. First, we collected sequential data in order to analyze the discourse context. In this respect, we investigated, for instance, the positioning of the form in question within a paragraph and what other tense-aspect forms it co-occurs with. Second, we analyzed the interaction of different imperfect uses in co-occurring contexts. Third, we were interested in the pervasiveness of the form in the text type at hand. While some of the insights from the first two aims are presented in Egetenmeyer (In press), the last issue is most relevant for the present paper.

We began with an analysis of the newspaper data contained in Emolex (see Diwersy et al., 2014) (the original URL, http://emolex.u-grenoble3.fr, is no longer available and has been changed to http://phraseotext.univ-grenoble-alpes.fr/emoBase/, accessed: June 16, 2021). It is a monolingual press corpus containing data from national and regional newspapers from the years 2007–2008. Kern and Grutschus (2014, p. 188) illustrate the two groups with Le Monde from 2008 and Libération from 2007, contrasted with Ouest-France from 2007 to 2008. In total, the corpus contains over 112 million words from close to 300,000 texts (see http://phraseotext.univ-grenoble-alpes.fr/emoConc/emoConc.new.php). Its data coverage is thus especially good. An important advantage of the corpus is that it contains the whole articles and does not inhibit their retrieval piece by piece in their entirety.

We conducted two different studies. The first one concerned nine verbal types or verbal phrases, where the verbs involved were marked for third person singular, imparfait d’indicatif. In terms of lexical context, the verbs were likely to occur in a football context. Among them were centrer (“to center”), dévier (“to deflect”) and the collocation marquer + but (“to score + goal”). As centrer (“to center”) presented a considerably higher number of instances than the other verbs used in the queries, we restricted our analysis in this case to the first 50 occurrences with football content. We found relevant instances for five of the verbs and retrieved forty-four relevant examples from a total of forty-two different newspaper articles. As indicated above, we were able to retrieve the whole texts in all cases.

Interestingly, the verb choice in combination with the inflection yielded a low percentage of noise in this corpus study. Approximately 83% of all hits occurred in a football context. Among these hits, the verbs contained in our queries may be classified in nearly 42% of cases as narrative uses of the imperfect in the sense defined in Egetenmeyer (In press) for football language. That is, they were part of strings of verbs marked by the imparfait which expressed sequences of events. Other instances showed a descriptive or background reading and the like, and were therefore not included in our data collection.

In order to test whether we could replicate our successful first study with another database, we issued further queries in the database Sketch Engine, and more specifically, within the sub-corpus “Timestamped JSI web corpus 2014–2017 French.” The corpus is very large. Therefore, we restricted the data to the year 2016, leaving us with over one billion tokens. We looked for the two verbs contrer (“to counter”) and dribbler (“to dribble”/“to pass someone dribbling”) and the verbal collocation marquer + but (“to score + goal”), whose components had to occur within a range of five words. Due to the high amounts of hits in all queries, we limited our focus to the first fifty items with a football context and where the noun but occurred in the singular. Thereby, we retrieved thirty relevant instances from twenty-nine different texts. In twenty-two cases we were also able to retrieve the entire article, either from the database or from the free internet, using queries in Google. Again, we analyzed the data retrieved in more depth.

In the previous section we discussed the ways in which we collected data on the linguistic phenomena presented in Theoretical Background. These phenomena are formally different, although they are based on a similar conceptual principle. As the phenomena pertain to different languages, different databases and corpora had to be used. The databases differ with respect to content-related specificity and with regard to the corpus query language, that is, what kinds of queries are possible. Therefore, we adapted our queries and we were able to retrieve relevant data in all cases. We then analyzed the data retrieved in depth.

It is important to recall the paramount aim of the contribution. We intend to collect evidence for the role genre plays in building up predictions for TAM marking. To achieve this goal, we need to understand the phenomena better. This guides the presentation of the results. In the following two sub-sections, we make reference to both German and French. Furthermore, both sub-sections combine quantitative and qualitative insights. The first sub-section considers Aktionsart properties of the verbs involved in the deviant TAM marking. The second sub-section discusses how the structures are embedded into the discourse they occur in.

Our interest concerns morphological marking on the verb, tense-aspect and mood marking, which deviate from a basic prescriptive marking. As indicated in Commonalities: Football Frame and Shifted Perspective Time, the phenomena in both languages show an important parallel in their temporal anchoring, resulting from the temporal perspective involved. Therefore, we can determine the most direct and pervasive potential factor of the forms analyzed as being the part of the verbs’ lexical meaning which is relevant in terms of temporal structure, namely, the Aktionsart of the verbs.

As part of the queries, we controlled for the Aktionsart properties. In the German queries, all verbs we searched for were telic in the reading in question. The examples we retrieved consist of eleven achievements and one accomplishment. In addition, the apodosis of the structure also contains a verb. There, we found a certain variance in terms of Aktionsart. The data retrieved show two achievements, four accomplishments, one activity and five states in the apodosis (see Table 2). This variance is also relevant for the relationships holding within the structures (see Discursive Properties).

Although in our French queries one verb was atelic, we were only able to retrieve instances with telic verbs. In the most extensive study, the one realized with Emolex, we were able to retrieve examples containing five different verbs of which, in their typical reading, three express achievements, one an accomplishment and one an ingressive process. Of the achievement verbs, centrer (“to center”) yielded most relevant examples (19), followed by dévier (“to deflect”) (9) and marquer + but (“to score + goal”) (8). The queries with the accomplishment verb dribbler (“to dribble” in the sense of “to pass someone by dribbling”) and the ingressive process contrer (“to counter”) both yielded four relevant occurrences each (see Table 3).

As noted in Collection of French Data in Non-Specialized Corpora, in this study, we retrieved whole articles and analyzed them further. The forty-four hits pertained to forty-two articles. From these forty-two articles, we selected those where at least 75% of all inflected verbs, not counting direct discourse if it occurred, were marked by the imparfait. In these cases, the imparfait forms typically occur in long sequences in which other forms intervene only very rarely. The non-imperfective forms rather tend to occur at the beginning or at the end of the articles. This augments the probability of narrative uses in sequence. The data set contained two articles which did not involve any other finite form than the imparfait and a further twenty-three articles showed 75% or more imparfait markings. Four further articles were close to the threshold, but we excluded them from the further step, together with the articles with fewer imparfait verbs than this. As part of this step, we analyzed the Aktionsart of all the imparfait verbs contained in the subset of twenty-five articles. In cases of doubt on the classification of the Aktionsart, we took a bearing on Lehmann (1991). We thereby intended to test the finding of Bres (1999, p. 5) that narrative imperfects frequently occur with lexically bounded verbs. However, it is important to note that not all of these imparfait verbs show a narrative use. Although a very high share actually occurs in chains of imparfait verbs, some may express intervening descriptions, fulfilling the function of stage setting or other non-narrative functions. Habituals are also possible. However, as the sheer proportion of verbs marked by the imparfait is unprecedented in French texts, it is reasonable to maintain this broad focus and not to select specific uses at this point.

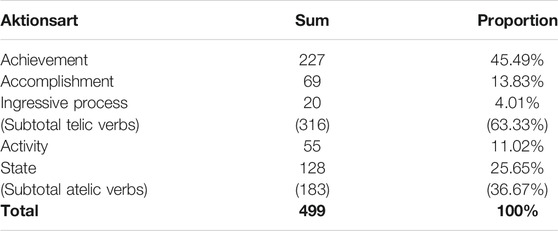

In the twenty-five texts identified, we found a total of 599 inflected verbs. Four hundred and ninety-nine of these verbs are marked by the imparfait (83.3%). Table 4 gives an overview of the distribution of imparfait verbs. Of these verbs, 316 are telic (63.3%) and 183 are atelic (36.7%). By far the largest group is that of achievement verbs, with 227 (45.5% of all verbs marked by the imparfait). This is precisely what we may expect from a football report, namely that events in sequence are narrated. The group with the second largest share is that of states, with 128 verbs (25.7%). Again, given the way we counted the verbs, this may be expected. Many of these verbs contribute background information against which the importance of the narrated events may be evaluated. Furthermore, there are 69 accomplishment verbs, 20 verbs expressing an ingressive process, which we also counted as telic, and 55 activity verbs.

TABLE 4. Aktionsart distribution of imparfait verbs in the 25 texts with the highest proportion of imparfait verbs (data from Emolex).

As noted with respect to the data coming from Sketch Engine, we were not able to retrieve the entire article in all cases. Therefore, we did not repeat the extensive study of the Aktionsart of all imparfait verbs in the articles, as we did with the data retrieved from Emolex. However, we analyzed the data with respect to preceding, following and intervening non-imparfait tense-aspect forms (see Discursive Properties).

In the preceding sub-section, we have already presented insights from the French articles which we retrieved as a whole. This was a first glance with respect to the more global perspective. However, the present subsection is dedicated to insights concerning the relational structure of the forms within their co-text. There are four main discursive properties which we derived from the data. With respect to German, we analyzed the function that the structure plays in the discourse context and the rhetorical relation which holds between its components. With regard to French, we investigated what tense-aspect forms occurred before and after long strings of verbs marked by the imparfait. Furthermore, we examined whether another form intervened and if so, which form that was. These insights may also be understood as indications of the discursive anchoring of the structures in question.

We expected the German present indicative substituting a pluperfect subjunctive to occur in oral or close-to-speech varieties. Interestingly, none of the cases we found in the corpora with specific football language are direct discourse (six instances), while in the non-specific newspaper corpora all six hits occur as part of direct speech. As noted with respect to the specialized corpora, we retrieved all six instances from corpora presenting live ticker data (“KIC,” “SID”) (see also Table 1 in Collection of German Data in Specialized and Non-Specialized Corpora for the distribution), which is a variety with characteristics of a language of proximity. Thus, the distribution of the data is as expected.

Furthermore, we analyzed the rhetorical relation between the two clauses comprising the German structure (see Kehler, 2002; Asher and Lascarides, 2003 and others). This is summarized in Table 5. Interestingly, relationships involving temporal sequentiality predominate. Five instances show a strict contiguity between the two eventualities expressed, which may be best classified as cases of occasion in terms of Kehler (2011, p. 1970) (see example 11). And, if we were to make such a fine-grained distinction, five further instances express a less direct temporal sequence that may be classified as NARRATION in the sense of Asher and Lascarides (2003, p. 162) (see example 12). One example shows a result relation (see example 13) and one an elaboration relation (see example 14).

11) Der Peruaner kommt an den Fünfer gerauscht, verpasst den Ball aber ganz knapp, der durch seine Beine geht. Wenn er den trifft, dann zappelt das Leder auch im Netz. (Cosmas II: SID/B16.00096).

‘The Peruvian rushes to the goal area, but just misses the ball, which passes through his legs. If he had hit (lit.: hits) it, the leather would have wriggled (lit.: wriggles) in the net.’

12) [1] Nach 70 Minuten hätte Nhu-Phan Nguyen den VfL erneut in Führung bringen können, [2] scheiterte jedoch […] an FCB-Torhüter Kevin Kraus. [3] “Womöglich war das der Knackpunkt. [4] Verwandelt er, [5] dann gewinnen wir das Spiel, [6] da bin ich mir sicher”, [7] erklärte Brunetto (Cosmas II: KSA14/SEP.08133).

‘[1] After 70 min, Nhu-Phan Nguyen could have given VfL the lead again, [2] but failed to beat FCB goalkeeper Kevin Kraus. [3] “Possibly that was the crux. [4] If he had converted (lit.: converts), [5] then we would have won (lit.: win) the game, [6] I’m sure,” [7] explained Brunetto.’

13) Alles oder nichts: Galvez steigt mit viel Risiko ins Tackling gegen Arnold ein und spielt den Ball. Trifft er das Leder nicht, muss er wohl frühzeitig zum Duschen. (Cosmas II: KIC/B15.00264)

‘All or nothing: Galvez makes a risky tackle on Arnold and plays the ball. If he had (lit.: does) not hit the leather, he would probably have had (lit.: probably has) to take an early shower.’

14) [1] Schäfer faustet einen Groß-Freistoß genau vor die Füße von Lex, [2] der aus etwa 16 Metern Maß nimmt [3] und mit Gewalt drauf hält. [4] Geht er rein, [5] schießt er das Tor des Monats – [6] doch so geht die Kugel über den Querbalken. (Cosmas II: SID/Z15.00097)

‘[1] With his fist, Schäfer diverts a free kick by Groß right at the feet of Lex, [2] who takes aim from about 16 meters [3] and shoots forcefully. [4] If the ball had gone (lit.: goes) in, [5] he had scored (lit.: scores) the goal of the month – [6] but this way the ball flies over the crossbar.’

While example (12) shows direct discourse (see also the examples in German Tense-Aspect-Mood Forms: Present Indicative Substituting Pluperfect Subjunctive), examples (11), (13) and (14) pertain to the written medium. Live tickers have a relatively strong tendency towards the present tense (see Hennig, 2000, p. 62–63 for a similar preference in live football reports). This is due to the way content is presented, namely, the utterance is supposed to be realized (or somewhat more realistically, to start) at the very moment the events referred to are seen. However, as examples (11) and (13) show, the conditional clauses refer to situations which might have become the case at a previous point in time (den trifft, “hits it”; trifft das Leder nicht “does not hit the leather”) but, as the speaker knows at the moment of speech, were not realized in that way (verpasst den Ball, “misses the ball”; spielt den Ball, “hits the ball”). The conditional clause is thus counterfactual. Similarly, in example (12), the interviewee (Brunetto) refers to a specific past moment described in clauses [1] and [2]. He considers that at a time point anterior to this, a win would still have had been possible. However, the condition of a goal (sentence [4]) was not met (see sentence [2]).

Example (14) is a bit more subtle and underlines what we argued for in Commonalities: Football Frame and Shifted Perspective Time, namely, the conceptual proximity between the true futurate present tense and the present indicative taking the place of a pluperfect subjunctive. Again, the live ticker seems to present the information as if it were in objective real-time. At the time of the shot, the goal is still possible. Thus, uttered strictly at this time, a present tense form may express potentialis or future reference. However, even if we abstract away from the fact that an utterance (in written form) is impossible in objective real-time (perception and taking notes simply takes too much time) and take the relevant temporal measurement to be a subjective time flow, we may still classify the second sentence of the example ([4], [5]) as irrealis. This is so because of the evaluation in clause [5] (schießt er das Tor des Monats, “he scores the goal of the month”), which can only be ascribed after the realization of the shot. And at that point in time, it is already known to the speaker that the attempt has been in vain.

In the French data, we analyzed the tense-aspect forms occurring before the sequences of verbs marked by the imparfait. This part of the study included all examples retrieved. We analyzed both the data from Emolex and the data from Sketch Engine. The sequences of verbs, typically one or more paragraphs, consisted of or at least contained the narrative uses of the imparfait which had been the focus of the data collection.

As noted, in the data retrieved from Emolex, in two cases two relevant verbs are contained in the same article. As, in both of these cases, the two verbs also pertain to the same sequence of imparfait verbs, we do not count two separate instances (which would amount to four); this leaves us with 42 relevant texts. Table 6 presents the frequencies of the different TAM forms. Twelve cases actually show an imparfait as first verb. Most frequently, the preceding verb shows a past tense with indicative mood (23 cases, 54.8% of all cases and 76.7% of the cases showing a verb other than an imparfait before the sequence). This may be expected. However, within this group the distribution does not adhere to a clear principle. There are eight verbs marked by the plus-que-parfait (the pluperfect), six marked by the passé simple (simple past marked for perfectivity) and nine marked by the passé compose (compound past). The remaining preceding verbs comprise four verbs marked by the present tense, one by the present conditional and two by the past conditional. With respect to the tense-aspect forms following the sequence of verbs marked by the imparfait, there is no clear tendency. The largest share is composed of the cases where no verb with a different tense-aspect form follows (19 cases). Apart from this group, there are three verbs marked by the pluperfect, four marked by the passé simple and another four by the passé composé. Nine verbs are marked by the present tense, two by the past conditional and one by the simple future. Finally, we analyzed the persistence of the imparfait within the largest sequence of imparfait forms in the articles. In our data from the Emolex corpus, the imparfait was predominantly persistent, as 26 “chains” of imparfait verbs were not interrupted at all (61.9%). In the 16 cases with an interruption (38.1%), we analyzed the verb forms intervening in the chains. More specifically, we focused on the first interrupting verb form. The variance is conspicuously reduced. There are only five different TAM forms, of which only three occur more often than once. Five verbs are marked by the pluperfect, four by the present tense, five by the past conditional and one each by the futur antérieur (future perfect) and the present subjunctive. In this data set, the interruption of the chain of imparfait verbs is mainly realized by only one verb. By contrast, there are only three cases where the interruption comprises more than one verb, and in one further case, the chain of imparfait verbs is interrupted twice. As stated, we only counted the first intervening tense-aspect form. Furthermore, it is interesting to note that many of the intervening tense-aspect forms are typical indicators of a perspective shift, namely, the pluperfect and the present tense (see Becker et al., 2021). This is another indication favoring our hypothesis of a special perspective in the case of the footballer’s imparfait (see Commonalities: Football Frame and Shifted Perspective Time), as interruptions of the chains correlate with a shift in perspective (see also Sthioul, 2000 for the interplay of tense-aspect forms and perspective taking).