- 1Department of Communication Studies, Kansas State University, Manhattan, KS, United States

- 2Leadership Communication Doctoral Program, Kansas State University, Manhattan, KS, United States

The unjust distribution of poor health outcomes produced via current United States food systems indicates the need for inclusive and innovative policymaking at the local level. Public health and environmental organizers are seeking to improve food environments from the ground up with locally driven policy initiatives but since 2010 have increasingly met resistance via state-government preemption of local policymaking power. This analysis seeks to understand how political actors on both sides of preemption debates use rhetorical argumentation. In doing so, we offer insights to the meaning-making process specific to food systems. We argue that advocates for local food-system innovations are forwarding understandings of food and community that contradict the policy goals they seek. We offer suggestions for local food and environmental advocates for adjusting their arguments.

Introduction

Opportunities to access healthy food and, consequently, diet-related health outcomes are unevenly distributed and disadvantage people of color, rural areas, and communities with lower educational attainment and economic activity (Larson et al., 2009; Walker et al., 2010; Cooksey-Stowers et al., 2017). The same is true of environmental hazards (Taylor, 2014). To address food and environmental health disparities, government officials, advocates, and community groups are engaging citizens in developing and advocating for healthy food environments. Such strategies include local policy initiatives ranging from healthy kids’ meals in restaurants to sugary drink taxes to requiring farmers’ markets to participate in food-assistance programs (Gorski and Roberto, 2015; Whitsel, 2017).

However, state governments have responded to such citizen-driven policy initiatives with an old tool—preemption—deployed in a new way. Preemption is a necessary means of ensuring consistency between levels of government, but evidence indicates that state legislatures increasingly turn to preemption to preserve favored policy by banning local discretion. Food-system reform is at risk, as is the democratic trust required of representative governance.

Because policymaking is intrinsically communicative and integral to food-systems equity, we undertook a rhetorical analysis of public testimonies offered for and against two preemption bills in Kansas, which has been a leader in state preemption. Through analysis of topoi and appeals in statements made by lobbyists, trade associations, nonprofit leaders, public-health officials, local-food activists, and concerned individuals, we find that those countering preemption’s limits on food and environmental policies could be undermining their cause with rhetorics of local control and responsibility.

We begin by reviewing scholarship relevant to democratic inclusion in policymaking and food-systems reform. We then highlight the general philosophy of food and environmental law in Western democracies, community-level efforts to improve, and how the new preemption in the United States blocks this work. We next turn to the role of rhetoric in policymaking, the cases we studied, and how we conducted the analysis. Our findings include simple counts of appeals and topics as well as interpretive readings to explain the connection between patterns of rhetorical choices made by those for and against preemption and the meanings they invited audiences to accept. We end by discussing what the appeals and topoi imply for food-system reform and make communication recommendations to address the new preemption.

Food Systems and the New Preemption

Reform via Policymaking: Possibilities and Limits

Our analysis enters food-systems communication scholarship via policymaking. As fundamentally communicative acts, policy and policymaking are ideal spaces for communication scholars to advance food-system reform.1 LeGreco (2012, p. 61) reminds that polices “serve important communicative roles in organizing everyday experiences.” Similarly, Asen (2010, p. 129) distinguishes policymaking from policy by pointing to their respective communicative functions, with the former concerned with meaning-making and the latter maintaining and enforcing meaning.

Regarding types of communication relevant to food-systems reform, Gordon and Hunt (2019, p. 13) identify “lobbying, boycotting, and mobilizing to call upon organizations—from non-profits, government institutions, and corporations” as typical. Recently and increasingly, scholars explore how peoples enact such advocacy outside formal channels. Nevertheless, institutional and organizational procedures such as federal rulemaking, legislative hearings, and strategic planning continue to facilitate policymaking. Ultimately, whether publics work within or outside of officially sanctioned processes, the policies they seek to alter merit consideration as they can profoundly shape food systems.

Arguably, people turn to extra-institutional communications in part because organizations disadvantage certain voices in policymaking, thus sowing “the seeds of distrust between leaders and community members” (Hunt et al., 2019, p. 5). In the context of food-systems reform, citizen-driven policy innovations are needed for practical and ethical reasons. Practically, policy initiatives are more likely to reduce health inequities when they are locally crafted and supported. Ethically, the very populations marginalized from policymaking uncoincidentally also suffer disproportionately from environmental (cancer, asthma) and nutritional (obesity, diabetes, etc.) diseases. Thus, “an important goal of law should be to maximize community voices, and especially the voices of socially disadvantaged and marginalized groups, in public health solutions” (Aoki et al., 2017, p. 11).

However, incorporating the diversity of knowledge, experience, communication styles, and opinions into a common process of policymaking in a fair and consistent manner across time and place is, to say the least, difficult. Through cross-cultural study of participatory processes in mostly for-profit organizations, Stohl and Cheney (2001) highlight four tensions that undermine inclusive policymaking: structure, efficacy, identity, and power. For example, as democratic organizations seek to successfully compete for resources and profits, they tend to encourage workers to participate in decision-making about issues immediate to their daily tasks while disallowing input in company-wide policy (Stohl and Cheney, 2001). As LeGreco (2012, p. 52) comments in her study of school-lunch policymaking, “Managing these types of paradox is an important part of working with policy, because stakeholders can encounter practices of text and talk that undermine policy goals.”

In public policymaking, the tensions of participation are magnified for at least three reasons. First, authority is fragmented across various agencies, making it difficult to enact policies that account for systemic interactions. In the case of food systems, departments of agriculture promote food production and marketing while departments of health and environment address air and water quality. Consequently, the interdependent effects of food production and consumption on soil, air, and water are inadequately addressed.

Second, public policymaking tends to be dominated by experts and special interests. While public-interest groups and concerned persons find spaces to contribute to state-level processes (Crow et al., 2020), Yackee (2006, 2019) demonstrates that businesses exercise out-sized influence in policymaking in fact and public impression. Yackee (2019) identifies two reasons for the dominance: the high cost of participation and the specialized expertise demanded of participants. Because commercial interests are most directly affected by regulations, they more readily justify the time and effort of lobbying at all stages of rulemaking. Regarding expertise, most public processes demand a specialized language and communication conventions. Additionally, Yackee (2019) finds that agency officials place greater value on the abstract arguments and technical details offered by experts compared to emotional appeals. At the legislative level, agribusiness campaigns successfully defend nutritionally and environmentally harmful farm subsidies as protecting the family farmer, indicating propaganda at work in policymaking (Schnurer, 2012). Ironically then, food and environmental policymaking in the United States is neither accessible nor deliberative since it fails to meet standards of discourse quality (Steiner, 2012).

Third, public policymaking is especially strained thanks to neoliberalist assumptions about personal responsibility and market omnipotence. As scholars across various fields demonstrate, public discourse presumes that markets know best and privatize the rights and responsibility of consumers to care for their own health. In the context of environmental policy, J. Robert Cox (2007) critiques “U-curve” arguments supporting economic development as the most effective and natural way to achieve environmental sustainability in the long term. Cox demonstrates that rhetorically, these considerations privilege economic development over environmental concerns while also making democratic debate irrelevant. Regarding food policy, framing obesity as an epidemic places responsibility on individuals, giving corporate food a pass (e.g., Lawrence, 2004; Thomson, 2009; Singer, 2011; Seiler, 2012).

Even when public participation in policymaking is encouraged, neoliberalist thinking channels it through consumerism, which offers the semblance of choice while in fact limiting options to those that preserve the consumerist system. Recent analyses show how such discourses hide in a cloak of common concern. Through analysis of Canadian public-health documents, Derkatch and Spoel (2017, p. 155) find that agencies “appear collectively to promote high civic values such as physical well-being, community prosperity, and sustainability.” However, the “notion of responsibility (particularly consumer responsibility) is mobilized to influence individual behavior regarding food consumption” (Derkatch and Spoel, 2017, p. 155). Similarly, via analysis of Australian food-policy documents, Ehgartner (2020) finds that environmental sustainability is included in policy considerations but only through the lens of consumer choice and personal responsibility. This framework emphasizes a free-enterprise model of consumption in which the healthy consumer is figured as an autonomous agent (Ehgartner, 2020). Thus, across Western representative democracies “civic values are instantiated within a framework of consumption and choice that invests market ideologies into the very language of public health” (Derkatch and Spoel, 2017, p. 165).

In contrast, the United States holds agriculture to a different standard. Rather than individual responsibility, much United States policy exempts agricultural businesses from liability for environmental harms (Ruhl, 2000). While the siting of concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs) generally remains the purview of county officials, “Right to Farm” acts further insulate agriculturalists from legal challenge over water, air, or noise pollution (Ruhl, 2000). Similarly, ag-gag laws that criminalize the undercover filming of industrial animal agriculture protect public conditions of “non-knowing” about its full effects (Broad, 2016).

Read together, food policy and environmental law support an understanding of publics primarily as food consumers responsible for their own choices. But as scholars and activists have documented, one’s health and environment are consequences not just of individual decisions. Social structures condition what food choices and physical activities are available, the quality and quantity of obtainable medical care, and how much pollution exposure one experiences. Dixon and Issacs (2013, p. 67) point to the growing global recognition that “health of populations cannot be divorced from eco-systems broadly understood.” Therefore, they (2013, p. 75) advocate for making “healthy and sustainable choices easy choices” through policies that lower costs and increase access.

The New Preemption and Food-System Reform

Toward similar ends, United States public-health practitioners and advocates employ a variety of policy, systems, and environmental (PSE) strategies to address institutional policy change, modify infrastructures or procedures, or improve social norms and attitudes toward healthy food. Emerging research shows that local policies may be effective in reducing obesity and type 2 diabetes rates (Freudenberg et al., 2015). But state preemption threatens to block food-systems reform. In fact, Bare and colleagues label the “threat of preemption to public health” to be “so great that the Institute of Medicine devoted a full chapter to the risks associated with preemption” in its 2011 report (Bare et al., 2019, p. 101).

In the simplest terms, preemption occurs when a higher level of government removes or limits the authority of a lower level of government. Preemption may take two forms: floor or ceiling. Floor preemptions, such as minimum wage laws, mandate a lowest standard beyond which local governments might adopt more stringent requirements. Floor preemptions are rarely relevant to PSE policy. In contrast, ceiling preemptions set a maximum standard for local policy. For example, a state preemption might disallow counties from raising property taxes more than 2% annually.

Preemption is an integral part of the United States system of governments, which is structured so that higher levels of government can limit the authority of lower levels to harmonize policy. Legitimately in many areas the states have an interest in uniformity or comprehensive regulation. Moreover, preemption has been used to advance well-being and equity. Haddow (2019) points to the federal Civil Rights Act of 1964 as a positive example.

While regulatory uniformity is often advantageous, political scientist Lori Riverstone-Newell (2018, p. 31) states that “it is not always necessary to create a workable business environment.” Nevertheless, every year since 2010 has seen more state preempting of local laws than the last. Termed “the new preemption” by Richard Briffault (2018) and “hyper-preemption” by Erin Scharff (2017), the current state preemption drive “is distinctive in its magnitude, malice and disruption of democratic norms” (Haddow, 2019, p. 49 ELR 10767). Over the past decade, dozens of states have passed laws to restrict or remove local authority on a wide range of issues, including anti-discrimination laws, short-term-rental rules, gun and knife control, creating municipal ISPs, sugary-drink taxes, and plastic-bag regulation (Hodge and Corbett, 2016; O’Connor and Sanger-Katz, 2018; Preetika, 2020). According to Jessica Bulman-Pozen (2018), an increase in single-party state government facilitates preemption, as well as partisan polarization. Additionally, many preemption bills in different states show uncanny consistency. Originally crafted by the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC), business organizations such as the National Rifle Association and the American Progressive Bag Alliance now distribute model preemption legislation. In doing so, they seize “not only on ideological affinity, but also on state legislators’ lack of time and resources” (Bulman-Pozen, 2018, p. 28).

Ostensibly, preemption battles are conflicts between state and local governments (Hicks et al., 2018). In fact, business interests and other lobbying groups drive the new preemption behind the scenes. Aoki and colleagues point to “the priorities of powerful interest groups such as Big Tobacco, Oil, Food, and even health-related trade organizations like the American Dental Association (ADA),” which “often conflict with health equity and community goals” (Aoki et al., 2017, p. 11). As Riverstone-Newell (2018, p. 31) concludes, the “role of industry and interest group influence on state preemption policies is clear, as are the effects of this influence on local autonomy.” Riverstone-Newell (2018, p. 31) goes on to warn that “state leaders, in their attempt to remove obstacles for industry groups or to create a social environment more pleasing to their constituents … may be overlooking the costs associated with lost local control.”

With these concerns in mind, we analyzed arguments made for and against two Kansas preemption bills: one broadly preempting local food and nutrition regulation and the other easing restrictions on siting poultry CAFOs irrespective of local land-use planning. We wanted to understand what strategies each side used as they sought to advance their respective cases with state legislators. Analyzing policy advocacy allows us to assess the potential effectiveness of various argumentative strategies and, more fundamentally, to explore how dominant understandings of the food system are resisted or reaffirmed in public discourse.

Analyzing Policymaking in Preemption Debates

Rhetorical Acts in Policymaking

Like other policymaking processes, local initiatives to improve food systems and the state laws that preempt them are “irreducibly rhetorical acts” (Asen, 2010, p. 129). Because policymaking processes are “atypical moments in the lives of policies where meaning-making appears as the central task occupying participants,” rhetorical analysis becomes an ideal means to consider this communicative dimension of food systems. Asen (2010) also attests to the inherently political nature of policymaking, which both constrains and enables rhetoric as a force within policy debates.

Therefore, we cataloged, described, and interpreted the “reoccurring inventional structures,” or topoi, drawn on by advocates for and against state preemption of food-system policymaking (Eberly, 2000, p. 4). Translated from the ancients as “commonplaces” or “haunts” where arguments could be found, conceptualizations of topoi vary widely. In his review of topical systems from Aristotle through Boethius, Michael Leff (1983, p. 24) concludes that “the classical lore of topics is as confused as the contemporary efforts to revive it.” Even so, scholars today consistently apply topoi in a way complementary with an understanding of knowledge/power as seated in discourse, making it an ideal “food systems perspective” in its concern for “the matrices of power, history, and ongoing forms of domination that affect food systems” (Gordon and Hunt, 2019, p. 11).2

Eberly (2000) argues that an analysis of topoi allows for least two things that a thematic analysis does not. First, it emphasizes “rhetoric as an art concerned centrally with the production—invention and judgment—of discourses” (Eberly, 2000, p. 5). Therefore, the topoi of policymaking debates “serve as both source and limitation for further discussion and deliberation.” Second, “topoi are architectonic in that...they serve as probabilistic function for the intentions and judgments of arguments” (Eberly, 2000, p. 5). For these reasons, a critical inquiry into topoi, rather than themes or frames, allows us to draw conclusions about the practical use of rhetoric in the world and suggest ways that advocates might improve their communication.

While Aristotelian commonplaces such as “more or less likely” or “consistency of motive” can help generate arguments, we sought an emergent reading of the texts and rhetorical situations. Toward a similar end, Eberly (2000, p. 6) approaches topoi-in-use as organic, meaning that they “disclose argument from the common ground up.” Therefore, rather than applying an existing topical system we approached the artifacts inductively, drawing on our knowledge of the controversies, the first author’s experience in policy advocacy, and our collaborative discussions to identify and assess patterns of topoi. Our goal was to understand how reliance on topoi by various actors constrained and enabled food-system reform.

Because special interests are commonly involved in preemption debates, we also analyzed appeals to self-interest and the common good. Deliberative democrats generally concur on the value of the common good but are divided on the proper place of self-interest (Steiner, 2012). We take the position of Mansbridge et al. (2010); namely, that expressing self-interest, properly constrained, improves the quality and diversity of information available in public decision-making and supports democratic inclusion. However, our primary interest is not in the normative questions of deliberative democracy but in the rhetorical choices of various political actors. Environmental advocacy groups, for example, use emotional communication productively, contradicting the frequent critique of environmental messaging as overwrought and manipulative (Merry, 2010). This research caused us to wonder whether and how various sources in preemption debates would use common-good and self-interest appeals, respectively, toward their political ends.

The Kansas Case

The Kansas legislature has been very active in state preemption. Since 2011, among other preemptions the legislature has revoked lower-level gun and knife regulations (Hanna, 2014), banned local minimum wages and housing inspections (Wentling, 2016), and eliminated inclusionary zoning. Additionally, the Kansas legislature considered but failed to pass bills banning municipalities from regulating retail bags (Swaim and Asbury, 2020) and providing internet services, a strategy for overcoming the digital divide in rural areas (Hiltzik, 2016).

In food policy, the legislature debated and passed HB2595 in 2016. It was one of 14 similar initiatives enacted within the past decade in the United States, but the Kansas version was the most restrictive of them all. It not only bars political subdivisions from addressing food and nutrition labeling, but it bans state agencies from doing the same, deferring all such policy to the federal government (Pomeranz et al., 2019). Modeled on an ALEC bill, it prevents local authorities from restricting portion sizes, taxing soda and sugary drinks, and banning incentive items in meals. Misty Lechner of the American Heart Association told Kansas City Public Radio that “no one was talking about wanting to ban soda sizes” in Kansas. Rather, localities considered “requiring park concession stands to provide healthy options alongside hot dogs, nachos and other typical snack foods,” but were thereafter “scared off by the state law” (Fox, 2019, para. 9–10).

Local citizen engagement figured into SB405, too, though in a different way. In 2017, a planned Tyson, Inc., development in Tonganoxie, Kansas, was rejected over county commissioner approval and Kansas Department of Agriculture recruitment, thanks in large part to community activism. The following year, the Kansas Department of Health and Environment introduced SB405. While not a preemption bill per se SB405 strengthened state control over land use, a function traditionally left to counties. Kansas law prohibits local zoning of agricultural land, with state statutes or executive agency interpretations determining how closely CAFOs may be placed to adjoining property (Volland, 2018). At the request of Tyson, which seeks another Kansas location for integrated chicken production, SB405 codified setbacks for dry-manure chicken barns, which were not previously addressed in state statute. The rule now allows barns of up to 333,333 chickens to be confined at a single site within 1/4 mile of any occupied structure and within 100 feet of a neighboring property line. Legislators also rejected a proposed amendment that would have allowed county citizens to vote on whether to site a large chicken slaughterhouse and associated CAFOs. Current Kansas law allows counties to vote on corporate-owned hog factories and dairies; therefore, failing to extend the same local consideration for chicken production demonstrates the bill’s de facto preemption.

Kansas in several ways mirrors others states active in preemption over the past decade. For most of this period, the state has experienced unified government, with Republicans controlling the House, Senate, and governorship. In fact, Republicans have controlled both legislative bodies in Kansas since 1993. Additionally, several of the preemption bills passed in Kansas were ALEC-authored bills, including HB2595. Finally, Kansas preemption laws targeted issues in which citizen groups in local communities engaged in policy work, including gun control in Topeka, safe housing in Manhattan, inclusionary zoning in Lawrence, and high-speed internet access in Chanute. For scholars of political participation and organizing, as well as social movements and contentious politics, the Kansas case offers a chance to learn how state preemption debates speak to citizen engagement and special-interest efforts to shape policy.

At the same time, Kansas affords several unique factors relevant to the new preemption and food-system reform. While many state preemption fights can be accurately characterized as partisan power struggles between Republican statehouses and Democratic cities, this in no way describes the Kansas experience. With the exceptions of Lawrence and Topeka, no Kansas county or city is controlled by or perceived to be controlled by Democrats. Therefore, striving for partisan dominance in policymaking cannot be driving Kansas preemption. Additionally, considering the food-labeling and agricultural-zoning bills together allows for comparison of policy preemption at different points in the food system, as well as contrasting political and legal contexts. While HB2595 originated in a nationwide partisan organization and banned local innovations at the point of sale, SB405 strengthened existing law in ways amenable to the agricultural industry and that explicitly rejected local consent. Therefore, we chose to analyze public debate before the legislature on these bills as case studies of meaning-making in policymaking.

Texts and Procedure

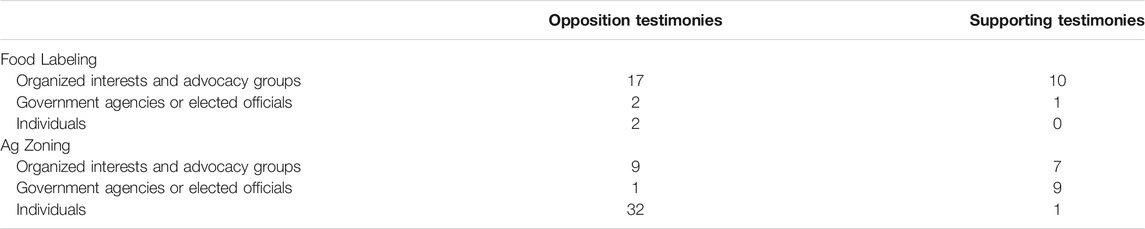

We conducted the analysis as follows: Public testimonies submitted for both bills were downloaded from the Kansas State Legislature website. In total, 91 were analyzed, with 32 submitted on HB2595 (hereafter, food-labeling bill) and 59 on SB405 (hereafter, agricultural-zoning bill).3 Except for three testimonies offered by science and technology experts, none run more than two, single-spaced pages. Most are only one page long. Table 1 summarizes the sources, categorized by who the testifier represented. Governmental agencies included executive branch (e.g., Kansas Department of Agriculture), local governments (e.g., Johnson County, The City of Lawrence), and research institutions (Kansas State Research and Extension). Organized interests and advocacy groups spanned trade associations (e.g., Kansas Corn Growers Association), public-interest organizations (e.g., American Heart Association and Kansas Sierra Club), and issue lobbies (Americans for Prosperity).

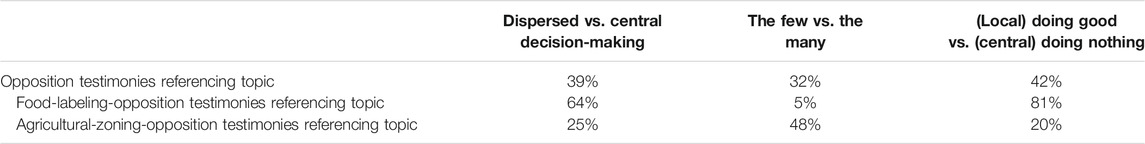

While initially reading the texts, we noticed that advocates for and against the respective bills offered markedly different kinds of arguments. Preemption advocates were clear and consistent. They posited that the bill provides uniformity and standardization for doing business; the bill protects the exercise of some right; and the bill prevents locals from making uninformed or malevolent policy. In contrast, PSE testimonies were heterogeneous, offering a greater number of novel reasons for opposing the bills. Ultimately, we decided to focus on what appeared to be the three most frequently used topoi in oppositional testimonies, which included the following: local decision-making is better than state legislators making decisions for locals; the bill preferences the few over the many; the bill ends positive civic work and/or policy preferred by locals. Tables 2, 3 summarize the topoi and their use in testimonies.

Regarding self-interest and common-good appeals, we followed Steiner (2012). Specifically, we defined self-interest as any reference to benefits or costs to self or one’s own group. For example, when Greg Krissek of the Kansas Corn Growers Association testified that the ag-zoning bill “would provide another marketing opportunity for the producers of Kansas corn to market their product and increase the production and profit potential of Kansas farmers,” we considered this an expression of self-interest. Conversely, common good included references to costs or benefits incurred by everyone in Kansas. In the same testimony, Krissek states that the new policy will lift “the entire Kansas economy,” a common-good appeal. We included both utilitarian (i.e., this does the most good for the most people) and difference appeals (i.e., all are served by helping the least advantaged in society) in our counts of common good.

The analysis proceeded as follows. We jointly developed a code sheet to guide the distinction between common good and self-interest appeals and to identify topoi. We next worked collaboratively on 20% of the testimonies, refining our criteria as we encountered disagreements and liminal instances. We then worked independently, recording the presence of common good and self-interest appeals as well as topoi in the remaining 80% of testimonies. Our agreement ranged from 81% to 97%.

For the second stage of analysis, we undertook collaborative readings of all testimonies. We did so to draw connections between the patterns of evidence in the artifacts to the messages’ persuasive potential (Hart et al., 2018, p. 85). More specifically, we sought to understand how topoi and appeals serve, to paraphrase Eberly (2000, p. 5), as resources and limits for further deliberation. Overall, we were struck by the ways the preemption advocates were advantaged in the debates and concluded that the types of arguments made and avoided had much to do with this impression.

Preemption Debates: Local Welfares, Mutuality, and Who Decides

Self Interest vs. Common Good, and Locals vs. Kansans?

Table 2 presents relative frequencies expressed as percentages of opposition and supporting testimonies with at least one common-good and one self-interested appeal, respectively. Strong majorities of both opposing and supporting testimonies included at least one self-interested appeal. Interestingly, a slightly lower percentage of supporting testimonies, which were almost exclusively submitted by trade associations, contained appeals to self-interest. Likewise, a higher percentage of opposition testimonies appealed to the common good of all Kansans relative to supporters of preemption.

Our analyses indicate that the opposition’s comparatively frequent appeals to self-interests are complemented by a foregrounding of the local. As detailed in Table 3, more than a third of all opposition testimonies include arguments drawn from the topoi of local versus central decision-making. Food-labeling testimonies especially relied on this topic, with almost two-thirds arguing for the superiority of provincial policymaking.

Some warrant decentralization based on the value of targeted innovations that leverage community characteristics. For example, Kansas Rural Center President Mary Fund concludes that “each community is unique and needs to be able to address food, nutrition, and access differently for the wellbeing of their populations. … This bill would take away a community’s ability to... address food-based health disparities and solutions tailored to their needs.” Amanda Gress of Kansas Action for Children echoes a similar sentiment: “KAC encourages policy makers to allow local government the ability to innovate and explore options to encourage healthy eating.” Others assert that local governments must be responsive to citizens. Johnson County officials testify that they support “the retention and strengthening of local home rule authority to allow locally elected officials to conduct the business of their jurisdiction in a manner that best reflects the desires of their constituents.” Still other PSE advocates turn to both policymaking and citizen trust to justify local authority: “The American Heart Association urges to you avoid a one-size-fits-all solution and allow our local units of government to be responsive to the desires of their constituents.” Overall, PSE advocates assert, as does Tonganoxie resident Kerry Holton, “The state needs to leave the rules as they are and allow local communities and counties to decide what sort of industry they want.” These examples illustrate that opponents offered different reasons for the supremacy of local food-systems decisions, but all originated from the same topoi: locals know best.

But as PSE advocates explain why local policymaking is needed, a contradiction emerges: the problems addressed are not local in cause, effect, or scope. In the food-labeling testimonies, preemption opponents turn to state-wide health indicators to support the need for local action, with a damning litany of facts indicating system failure:

• American Heart Association: “64.4% of Kansans were overweight or obese.”

• Kansas Rural Center: “Kansas ranks 13th in the nation for adult obesity, with an obesity rate of 31.3%. 30% of Kansas children age 10–17 are considered overweight or obese.”

• KC Healthy Kids: “Currently, 30% of Kansas children age 10–17 are considered overweight or obese.”

• Kansas Public Health Association: “The health of Kansans has not been moving in the right direction. According to a 2015 America’s Health Rankings report, Kansas dropped to the 26th healthiest state in the nation, down from 8th place in 1991.”

Given the widespread, negative outcomes of the food system, these presentations would prompt a naive listener to wonder why the state government is not being called upon to address the issue.

Regarding causation, Ashley Jones-Wisner of KC Healthy Kids cites the 2010 Dietary Guidelines for Americans, which she says point to “eating and physical activity patterns that are focused on consuming fewer calories, making informed food choices, and being physically active.” Jones-Wisner does not explain why these general causes require tailored policies. Critical analyses detail how the obesity frame preferences personal culpability over systemic changes to remedy health inequities (see e.g., Seiler, 2012). In preemption debates such discourses are doubly detrimental, as faulty individual actions dispersed across society do not directly support the need for localized, systemic solutions.

Likewise, advocates opposing the ag-zoning bill point to a systemic problem, that being industrial-scale animal production and slaughter, but do not explain why local policy is the preferred response. Sue Lamberson of Clearwater passionately testifies as follows:

Not only do these methods use up precious water resources, and pollute the air and ground where they are, they also produce meat that isn’t healthy for us to eat. The cruelty to the animals and the unsafe, low wage jobs that come with these places are other reasons to keep them from establishing any more locations in our state. We do not need to produce toxic, cheap meat at the expense of our precious water resources and our clean air.

Janet Hofmeister, Tonganoxie, also testifies against “The Tyson Bill” by pointing to state environmental harm. Nevertheless, she seems resigned regarding whether anything can be done, state-wide or locally:

I feel sad for Kansas. I have always boasted to my out-of-state relatives and friends on how beautiful Kansas is...how our lakes are beautiful and our air fresh. However, more and more, our state is being ruined by legislation that is more beneficial to big business and less beneficial to the people who live in Kansas.

Opposition testimonies such as these essentially argue that no one should have to suffer industrial chicken production, contradicting calls for local policy discretion. Lamberson concludes, “We can’t let Kansas go the way of Iowa with all their CAFO’s. And as a property owner and taxpayer, I should be allowed to vote on whether some monstrosity like this is allowed to set up shop in my community.” But as her testimony makes clear, if “this monstrosity” comes to her town of Clearwater, the ill effects will be felt throughout the state. Why ought Clearwater residents have a say, for example, while Arkansas City, 50 river miles downstream, should not?

Certainly, a case can be made for homegrown standards to ameliorate systemic problems. For instance, the localized nature of foodways and living arrangements, as well as the uneven geographic and social distribution of health outcomes, ought to justify local policymaking. And a few PSE advocates provide local evidence. The Latino Health for All Coalition testifies thusly:

The issue of nutrition and the food environment is particularly important to our community. In Wyandotte County, almost 40% of adults are reported to be obese. Approximately one in five Wyandotte County residents live in areas with limited access to opportunities to purchase healthy foods in supermarkets or large grocery stories.

Despite the association’s mission, the testimony lacks a specific reference to the disproportionate health effects faced by Latinx communities in Wyandotte County, which could benefit the argument that cultural knowledge is a strength of localizing policymaking. Thus, the testimony does not go as far as to indicate why local solutions are necessary to attend to cultural rules, norms, and the social environment of the Wyandotte County community.

When advocates working to defeat the Tyson Bill turn to local distinctions, they sometimes point to factors that have as much to do with relative privilege as unique policy needs. Kerry Holton admits that “corporate agricultural processing facilities have a place in Kansas, but, when they are inappropriately located, the harm done to communities can be devastating and permanent.” Holton further explains that his town of Tonganoxie, a bedroom community for Topeka and suburban Kansas City, is too densely populated to be suitable for industrial-scale chicken farming. Undoubtedly, more people will suffer the air pollution, noise, truck traffic, and declining property values of a Tyson plant if placed in Leavenworth County instead of sparsely populated Cloud County, for example, 150 miles to the west. However, Cloud County’s median household income also is 38% lower than Leavenworth’s, leaving open the possibility that socioeconomic status has much to do with Cloud County’s appropriateness. In the end, PSE advocates undercut their own rationale for local control by allowing a place for CAFOs in any community.

Meanwhile, preemption advocates deemphasize what they will gain by curtailing local policymaking and instead present preemption as serving the common good. Sometimes, they do so by connecting agricultural businesses to the broader Kansas economy, as does the Kansas Agricultural Alliance, which states, “The construction of a new agricultural processing facility and the accompanying investment in animal agriculture infrastructure in Kansas is a great way to encourage growth and provide job security for both rural and urban Kansans.” Alternately, preemption supporters refrain from directly addressing either special or public interests. The testimony of Stacy Forshee, a Farm Bureau member from Cloud County, is illustrative. In her 360 words on HB2595, Forshee clearly communicates Farm Bureau’s position on the bill (supportive, with a preference for federal rather than state labeling standards) without explicitly stating why. She details what Farm Bureau supports (“consumer friendly, science-based labeling”) and rejects (“mandatory labeling of food products containing biotechnology”) but never explains the costs or benefits of these policies to farmers or anyone else. Apparently, she does not need to do so, for she uses phrases that signal positions Kansas Farm Bureau has put before legislators dozens of times in committee testimony and other lobbying activities. Consequently, preemption supporters can offer their backing without testifying explicitly to what they potentially gain from the bill.

Some PSE advocates present the food system and its shortcomings as a common, state-wide problem. Dawn Buehler of Friends of the Kaw, an organization protecting the Kansas River, reminds legislators that the watershed crosses three states and provides “drinking water for 800,000 Kansans.” She claims the ag-zoning bill is not a threat to any community but to all of them: “All of that waste has the potential to pollute our drinking water every time it rains and the water and pollution from this facility will impact everyone downstream, all the way to Kansas City.” Eschewing scientific language for a plainspoken style, Buehler makes the case that what happens on a farm in Central Kansas affects all on the river: “That is how watersheds work—if you are down stream, you get the pollution.” Brian Morely of Lawrence puts it even more succinctly: “S.B. 405 is an affront to our common wealth and a dangerous health risk as well.” However, these examples serve as exceptions. As a group, the PSE testimonies posit the non sequitur claim that food systems are failing the state’s citizens and locals ought to be empowered to improve them.

Critiquing Policy or Power

Thinking strategically, the preceding discussion raises a no-win choice for PSE advocates: Should they point to legislative inaction as justifying local initiative? Or should they foreground local successes in improving food systems? PSE advocates in the food-labeling testimonies overwhelmingly chose the latter, dipping into a deep well of nascent efforts across the state to improve healthy food access and information. As reported on Table 3, 42% of all opposition testimonies found inspiration in the local-action topic, with an overwhelming 81% of food-labelling statements using the topoi.

Several illustrations of how reform advocates use the local-action topoi follow:

• Marjorie Van Buren, Topeka: “[HB2595] would hinder, if not stop altogether, the fledgling efforts of Kansas communities to create more economic development around local food.”

• Lea Ann E. Seiler, Hodgeman County: “HB 2595 will halt the momentum of GROW; as well as that of our Lions Club Community Garden; Countywide Farmers Market; and initiatives that support increased access to healthy foods in our community (such as adding frozen yogurt sticks to the snack menu at the swimming pool in the summertime--instead of only candy bars).”

• Johnson County officials: “HB2595 would be a huge step backwards in JCPRD’s efforts, and successes, to positively impact the community’s health and well-being.”

• Cultivate Kansas City: “HB 2595 will halt the growth of the food policy councils, community gardens, local farms, urban agricultural zoning, and other local initiatives that support wider availability of health food across Kansas communities.”

In contrast, practically no one mentions state-level inaction to address glaring food-system failures. While not part of our topical tally, we found exactly two such examples. In both cases, the authors make this point near the end of their respective testimonies, offering it more as an afterthought than a central argument.

But for a body charged with enacting policy in the best interests of the state, success at the local level could be read as evidence of the legislature’s fecklessness or, worse, a competitor succeeding where legislative authority has failed. Preemption advocates encourage this interpretation, offering liberal-state boogeymen as visions of what lies ahead if locals go unchecked. While the Kansas Chamber of Commerce states that “burdensome regulations and restrictive laws are unfortunately becoming a part of everyday life,” they point to no Kansas examples. Instead, they turn to “New York City’s proposal to ban sugary drinks, and San Francisco’s ban of Happy Meal toys.” As examples of “restrictive regulations on the food service industry,” the Kansas Restaurant and Hotel Association predicts “specific labeling requirements related to trans fats, sodium etc., along with local limitation on the size of sodas and french fries (sic.) and prohibitions against toys in a chain’s value meal.” Never mind that no Kansas cities or counties have ever considered such policies. Rather, the hot-button examples plucked from media coverage suggest a threat to businesses and legislative authority.

Those supporting stronger preemption of agricultural zoning use similar tactics. The Kansas Farm Bureau has “seen political subdivisions in others states limit agriculture producers from being able to raise or grow certain products based off of biased and non-science-based information, including misleading marketing ploys.” In case legislators miss the point, Roger Woods of Americans for Prosperity reminds that competing political subdivisions are legion: “Kansas has more than 700 municipal and county governments that currently have authority to impose local ordinances.” While the casual reader might not immediately recognize these as scare tactics, the primary audience is Republican state legislators. If they have committed to maintain a positive business climate and have any ego invested in being an elected official, such statements could provoke a motivating fear to kill challenges to their policymaking authority while they still can.

To protect their position from being understood as a power grab, PSE advocates employ several rhetorical strategies. LiveWell Lawrence, for example, defines local policy initiatives as a capacity that the state should be encouraging, not a competitor to quash: “Local authorities need support to develop effective solutions to address the most pressing public health concerns in Kansas today … If this legislation were to become law, it could negate the capacity that exists in our local communities to develop evidence-based strategies to address these issues.”

Most notably, PSE advocates return to the topoi of local authority. In Hodgeman County, the local food-policy council is said to have been “developed in response to the community’s need AND desire” for more healthy choices: “Kansas residents WANT to enhance their LOCAL food system, and want the local control to do it. A resolution authorizing GROW was signed by our Board of County Commissioners in May 2015.” Johnson County officials cited a 2012 survey indicating overwhelming support for calorie counts and healthy food options at county concessions and workplaces. Billie Hall of the non-profit Sunflower Foundation defends local governments as “responding to the preferences of their constituents by increasing access to nutritional information.” Hall continues as follows: “Kansas consumers want nutritional information so that they may choose healthy options for themselves and their families. Voters have made this clear with the recent increase in publicly appointed food policy councils across the state.”

Nevertheless, business advocates paint pre-empting local food policy as a legislative duty that must be taken up lest chaos ensue. We note the appeal to the legislature’s authority in a Kansas Farm Bureau testimony, made more urgent by the federal government’s failure to assert its own: “In the absence of federal regulation on nutrition and menu labeling, the state of Kansas should exert authority and ensure fair and unbiased sound-science labeling is enacted in all 105 counties and all cities within the state.” Additionally, advocates suggest legislators’ pre-emptive responsibility is relatively modest. Thus, compared to the regulatory morass threated by 700 uncheck local governments, preemption bills are said to be an unobtrusive and necessary means of standardization. Nearly three-quarters of the pro-preemption testimonies take advantage of this commonplace (see Table 4) to argue for the exertion of legislative authority for homogenous business rules.

Meanwhile, only 24% of preemption proponents look to the topoi of sound science versus incompetent and nefarious local politics. Even so, when read carefully the arguments originating from this place suggest that preemption must be something more than mere neutrality. For example, a hypothetical offered by the Kansas Association of Wheat Growers indicates that “if a regulation requires only the disclosure of carbohydrates, then it could lead the consumer to reasonably conclude that a Fudgesicle (16 g of carbohydrates per 100 g) is healthier than a slice of bread (22g of carbohydrates per 100g).” The absurdity surely is meant to draw a chuckle, but the fantastic scenario also invites questioning. No subdivision would require labeling only carbohydrates in the name of more nutrition information, so what are the Growers suggesting?

Similarly, Christianne Miles of the vending company Treat America Foodservice warns that without the bill, doing business will be nightmarish:

Vending operators would need to warehouse and transport more product with different labels that meet the local requirements. … In addition, it would also place a burden on manufacturing and distributors that would be face with having to have different product packet for each of their items sold to comply with local rules.

It indeed sounds onerous, but the reality of state-and-federal policy shows it to be mostly mythmaking. To our point, automakers have not responded to California’s tougher fuel-efficiency standards by manufacturing a separate line of California cars. And despite the scare tactics, only two states—Kansas and Mississippi—have pre-empted local food policy to the bill’s extent. Yet nationwide no one is arguing Fudgsicles to be health food nor are manufacturers creating separate lines of food packaging for various cities.

In sum, while preemption advocates suggest that their bills are a legislator’s apolitical duty—nothing more than establishing a uniform set of rules—in fact preemption blocks policy reform. To its credit, the Kansas Chamber of Commerce is explicit in why it supports the bill: “HB2595 prohibits excessive regulations on restaurants and vending machines in the state.” Thus, the new preemption allows industry to rhetorically position the bill as a disinterested leveling of the playing field while in fact putting its organized thumb on the policy scale by protecting the status quo.

In the instance of agricultural zoning, the choice of rhetorical stance for food-system reformers is foregone since Kansas does not allow local control. Only 20% of opposition testimonies on the ag-zoning bill forward the superiority of local initiatives, while 48% contend that the interests of a few are privileged over the many (see also Table 3). Some authors offer a strident tone as they directly accuse legislators of failing to represent constituent interests, as do the following:

• Kerry Holton, Leavenworth County: “Senate Bill 405, if made into law, will allow large corporate agricultural processing corporations to make an adverse impact on the constituents who sent you to Topeka to represent them.”

• George Hanna, Tecumseh: “I respect each and every one of you…however, any consideration of such a bill like Senate Bill 405, blatantly disregards the wishes of the people for whom the communities are affected and their elected official within local government.”

• Alisa Branham, Douglas County: “Please encourage people to stand up against this bill, or at least allow local citizens to make the final decision about whether it’s built or not.”

Each of the proceeding advocates certainly opposed expansion of the poultry industry. But we also note that their arguments quoted here have little to do with the merits of the policy change. Rather, each is critiquing the legislative process. Put more crassly, these advocates are telling elected official how to do their jobs.

Alternately, some advocates save face and more directly address the policy at hand by pointing to the usurpation of local agricultural zoning, arguing legislators consequently are responsible for acting on behalf of citizens who might find themselves living next door to 333,333 chickens. In stating Kansas Rural Center’s opposition to the ag-zoning bill, Paul Johnson cites “expansion of State preemption power over county governments in siting and environmental issues in regards to industrial poultry operations.” He then calls for a year delay to research “the social and environmental impact of industrial poultry impacts on local communities and the State.” Thus, Johnson invokes the legislators’ responsibility to do right by the state’s citizens rather criticizing them for even entertaining the bill.

Because the ag-zoning bill effectively strengthens state control over land use, many PSE advocates are drawn into critiques that are only obliquely related to food-system failures and have more to do with who controls policymaking. These questions merit consideration, particularly in the face of the new preemption. But we also wonder about the effectiveness of this choice when testifying before legislators. Stylistically, it positions PSE advocates as outsiders, having to beat on the statehouse door to be heard.

Discussion

Others have pointed to partisan polarization as a driver of the new preemption (e.g., Bulman-Pozen, 2018). Certainly, readers of these testimonies might wonder if the authors from the respective sides were declaiming on the same legislation. According to Hart, Daughton, and LaVally (2018, p. 91), “Topical analysis is particularly useful for examining public controversies, arenas in which people often talk past one another precisely because they have begun their arguments in different places.” Our simple counts and critical readings indicate a more fundamental divide than partisanship, with proponents commencing from neoliberalism and opponents from populism. In what follows, we consider implications of these choices for food-systems reform, as well as the specific ways that advocates might shift their arguments to challenge the new preemption.

Neoliberalism or Populism: A False Choice for Food-System Policy

In their testimonies 79% of proponents visited the topic of uniform business regulation. A few argued from the position that diffuse policymaking is deleterious and even fewer defended preemption as emanating from a held right. These totals, combined with our interpretive readings, indicate that supporters start from neoliberalist assumptions about the cool rationality and effectiveness of markets. Consequently, preemption supporters find themselves in an enviable rhetorical situation: While they are on the offensive in advancing new legislation, they can do so with a discourse that defends unfettered markets as maximizing good, which is mostly taken for granted in United States politics.

Meanwhile, opponents of preemption found inspiration in at least three different places: dispersed versus centralized decision-making, the few versus the many, and taking initiative versus expecting others to act. Thanks to its global resurgence, many will recognize the populist thread running through these topics. In a country founded on suspicion of distant elites and centralized power, populism is a reasonable place to look for arguments. Michael Lee (2006, p. 374) locates a similar topoi emanating from “The Declaration of Independence, in concert with a populist reading of the Preamble of the Constitution, Jefferson’s First Inaugural, and the rhetoric of anti-Federalist opposition … from which subsequent populists found a structure and a political language.” But as our reading suggests, deploying this discourse to reform food systems could be counterproductive.

To our point, our analysis suggests a form of NIMBYism (not in my backyard) at work in some of the opposing testimonies (DeLind, 2004). Gregory Koutnik (2021) posits a positive parallel between populism and NIMBYism. Koutnik (2021) argues that “ecological belonging” can be galvanized to mobilize people to participate in political action in defense of places they call home. Patrick Devine-Wright (2009) makes a similar suggestion from a social-psychological perspective. Even so, to avoid the exclusionary and authoritarian impulses of some populisms organizers will need to find ways to rise above defense of beloved places. Usher’s (2013, p. 825) study of anti-coal action in the United Kingdom speaks to the difficulties and potential of such an approach, which requires reformers “transcend localism” and its strongly felt place attachments. From our reading, we agree that the psychological drives that lead to NIMBYism are not the problem. Rather, the failure to see mutuality in others’ losses is what turns protection of home into regressive NIMBYism.

Additionally, by adopting what Lee (2006) terms the populists argumentative frame, food-system reformers lose an opportunity to challenge the dominance of neoliberalism in policymaking. Until presumptions that unencumbered markets provide the highest level of social good are called to question, it is unlikely that PSE advocates will be able to effectively argue that policy innovations at the state or local level are needed to improve public health and the environment. While home-grown innovations to food systems can strengthen local economies, at the statehouse such arguments will always be at a disadvantage when competing with organized business claiming to represent thousands of members and vast segments of economic activity. Likewise, arguing that preemption benefits the few over the many will fail to persuade since such a statement is illogical to neoliberalist thinking. Therefore, the dominance of neoliberal logics and the argumentative strategies that uphold them must be addressed in food-policy debates.

Rhetorical Strategies and Tactics for Countering the New Preemption

Arguably, PSE advocates in Kansas are not full and equal participants, giving credence to populist conspiracies. Both bills passed by comfortable margins despite opposing testimonies outnumbering supporters two-to-one. Others have documented how the hegemony of sound science marginalizes reform activists in institutional policy debates (e.g., Sauer, 1993; Healy, 2009). Given the demonstration of disregard for local control in the Kansas case and with sensitivity to the rhetorical context, public-interest advocates likely will need to use communication strategies that question the legitimacy of the process.

At the same time, our analysis suggests PSE advocates ought to reflect on the ways that their argumentation could be unwittingly reifying an understanding of food systems that contradicts their larger philosophy and goals. Overall, we encourage PSE advocates to creatively engage in preemption debates in ways that forward local innovations and consent as a necessary benefit to all. Specifically, we offer the following three recommendations.

First, in future preemption debates PSE advocates should emphasize that state food-system policies are failing everyone. While our quantitative results indicate just over half of opposition testimonies included appeals to the common good, our readings indicate that the weight of these arguments might be lessened by other rhetorical choices. By instead crafting testimonies that illustrate how state policy—or the lack thereof—has harmed the common good, advocates would be implicitly acknowledging the legislator’s power to act in a way that shapes local action for the benefit of everyone. This stance can be achieved without discursively relegating community action to a subsidiary role by emphasizing local efficacy as a state asset. Overall, rhetorics that approach food-system policy as a partnership between the state, local governments, and citizens will better support policymaking for all places and communities.

Second, we encourage PSE advocates to counter the dominant trade-association definition of preemption bills as objective and apolitical. Ultimately, no public policy is neutral; contra to supporter rhetoric, preemption is an effort to codify current practices. In our analysis, we found no examples of PSE advocates challenging this rhetorical argumentation. When advocates can forward their preferred definition of preemption as a neutral policy that only promotes fairness, opponents lose an opportunity to demonstrate that preemption ties the hands of public servants across all levels of government—including the legislator’s own—making it even harder to address public problems.

Third, rather than countering state preemption with claims of harm to local property values or as threats to citizen choice, we suggest PSE advocates look to undermine neoliberal logics in their argumentative strategies. For example, more coordination among advocates would allow them the speak with a unified voice on the social inequities endemic to the current food system. If the spokesperson from Latino Health for All speaks of the disproportionate effects of food deserts in her community, she might be able to build an appreciation for the common good on the principle of difference. But what if public-health advocates across the state spoke to the damage done in their own communities and others. To illustrate, imagine the local-food advocate from Hodgeman County in rural Western Kansas testifying that local innovation helps her neighbors as well as the residents of Wyandotte County in Kansas City. It now becomes harder for legislators to ignore that the market has failed to lift all boats as promised.

Alternatively, rather than allowing for the appropriateness of industrial animal slaughter in some communities PSE advocates might demand economic development driven by people and planet first. A handful of PSE advocates testifying against the Tyson Bill do this, as does Tad Kramar of Big Springs: “If you want to create economic opportunities, please vote ‘no’ on SB 405 and instead promote businesses that create good jobs rather than degrading jobs that produce personal injury and suffering to people, animals and the surrounding communities.” Margaret Kramar more directly questions the unspoken neoliberal assumption that more business is always good: “Of course we are united in wanting to bring economic opportunities to Kansas, but how low are we willing to go to pursue that objective? Would we stop at nothing?” Margaret Kramar goes on to detail the Kansas values sacrificed in pursuit of pure profit, closing thusly: “Sometimes compassion should take precedence over profit. Please oppose this bill, if not for the people, for the animals, and if not for the animals, for the people growing and slaughtering the chickens.” As did the Kramars, advocates can allow for economic needs while insisting legislators adopt policies consistent with other community standards.

Conclusion

This analysis considered two Kansas deliberations over who should set food and agricultural policy. We determined that some rhetorics resisting the new preemption offered populist, us-against-them understandings that failed to address neoliberalist assumptions and food-system inequities, potentially reifying public understandings that compound current crises. We also suggested alternatives to countering preemption of public-health and environmental policies. Through greater coordination and recognition of publics across locales, a discursive commitment to mutual well-being, and a reimagination what advocates ask of policymakers, public-interest advocates might cultivate more just food systems.

Policymaking is a struggle over not just policies but also cultural values, which are shaped over time by such debates. People can act purposefully to change their shared values, and politics, “an arena of competition and struggle between conflicting and genuine values,” is one means of doing so (Sleat, 2013, p. 136). While all public-policy deliberations can promote or delay social change, food systems affect the welfare of all peoples and the planet. Consequently, reordering our use of finite resources for justice and sustainability demands special urgency and ethical vigilance. We offer our analysis toward these ends.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

Written informed consent was not obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Funding

This research was funded in part by the Office of the Vice President for Research, Kansas State University.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the editor and reviewers for their pertinent and insightful suggestions. We also thank David Procter, who introduced the first author to preemption debates, and graduate research assistants Joseph Kauffman and Michelle Styrpejko for their dogged pursuit of information about preemption in Kansas.

Footnotes

1Gordon and Hunt (2019) suggest at least three paths for food-systems communication scholarship, including reform, justice, and sovereignty. As they suggest, the paths are not mutually exclusive. This analysis, too, primarily considers policymaking as a means of systems reform but also implicates questions of justice as well.

2See, for example, Condit’s (2019) “supra Aristotelian/Foucauldian” theory, as well as Eberly’s (2000) use of topoi in the classical sense along with a Foucauldian analysis of power and cultural authority.

3Testimonies on HB2595 are available at http://www.kslegislature.org/li_2016/b2015_16/committees/ctte_h_cmrce_lbr_1/documents/date-choice-2016-02-17/. Testimonies on SB405 are available at http://www.kslegislature.org/li_2018/b2017_18/committees/ctte_s_agriculture_and_natural_resources_1/documents/date-choice-2018-02-12/ and http://www.kslegislature.org/li_2018/b2017_18/committees/ctte_s_agriculture_and_natural_resources_1/documents/date-choice-2018-02-13/ and http://www.kslegislature.org/li_2018/b2017_18/committees/ctte_h_agriculture_1/documents/date-choice-2018-03-06/.

References

Aoki, J. R., Peters, C., Platero, L., and Headrick, C. (2017). Maximizing Community Voices to Address Health Inequities: How the Law Hinders and Helps. J. L. Med. Ethics 45 (S1), 11–15. doi:10.1177/1073110517703305

Asen, R. (2010). Reflections on the Role of Rhetoric in Public Policy. Rhetoric Public Aff. 13 (1), 121–143. doi:10.1353/rap.0.0142

Bare, M., Zellers, L., Sullivan, P. A., Pomeranz, J. L., and Pertschuk, M. (2019). Combatting and Preventing Preemption: A Strategic Action Model. J. Public Health Manage. Pract. 25 (2), 101–103. doi:10.1097/phh.0000000000000956

Broad, G. M. (2016). Animal Production, Ag-Gag Laws, and the Social Production of Ignorance: Exploring the Role of Storytelling. Environ. Commun. 10 (1), 43–61. doi:10.1080/17524032.2014.968178

Bulman-Pozen, J. (2018). State–local Preemption: Parties, Interest Groups, and Overlapping Government. PS. Polit. Sci. Polit. 51 (1), 27–28. doi:10.1017/S1049096517001421

Condit, C. M. (2019). Public Health Experts, Expertise, and Ebola: A Relational Theory of Ethos. Rhetoric Public Aff. 22 (2), 177–215. doi:10.14321/rhetpublaffa.22.2.0177

Cooksey-Stowers, K., Schwartz, M., and Brownell, K. (2017). Food Swamps Predict Obesity Rates Better Than Food Deserts in the United States. Ijerph 14 (11), 1366. doi:10.3390/ijerph14111366

Cox, J. R. (2007). “Golden Tropes and Democratic Betrayals: Prospects for the Environment and Environmental justice in Neoliberal “Free Trade” Agreement,” in Environmental Justice and Environmentalism the Social Justice Challenge to the Environmental Movement. Editors R. Sandler, and P. C. Pezzullo (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press), 225–250.

Crow, D. A., Albright, E. A., and Koebele, E. (2020). Evaluating Stakeholder Participation and Influence on State‐Level Rulemaking. Policy Stud J 48 (4), 953–981. doi:10.1111/psj.12314

DeLind, L. B. (2004). Social Consequences of Intensive Swine Production: Some Effects of Community Conflict. Cult. Agric. 26 (1-2), 80–89. doi:10.1525/cag.2004.26.1-2.80

Derkatch, C., and Spoel, P. (2017). Public Health Promotion of "Local Food": Constituting the Self-Governing Citizen-Consumer. Health (London) 21 (2), 154–170. doi:10.2307/2664516710.1177/1363459315590247

Devine-Wright, P. (2009). Rethinking NIMBYism: The Role of Place Attachment and Place Identity in Explaining Place-Protective Action. J. Community Appl. Soc. Psychol. 19 (6), 426–441. doi:10.1002/casp.1004

Dixon, J., and Isaacs, B. (2013). Why Sustainable and 'Nutritionally Correct' Food is Not on the Agenda: Western Sydney, the Moral Arts of Everyday Life and Public Policy. Food Policy 43 (0), 67–76. doi:10.1016/j.foodpol.2013.08.010

Eberly, R. A. (2000). Citizen Critics: Literary Public Spheres. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press.

Ehgartner, U. (2020). The Discursive Framework of Sustainability in UK Food Policy: The Marginalised Environmental Dimension. J. Environ. Pol. Plann. 22 (4), 473–485. doi:10.1080/1523908X.2020.1768832

Fox, M. (2019). On Food Policy, Kansas Defers to the Feds More than Anyone. Kansas City, MO: KCRU. Available at: https://www.kcur.org/post/food-policy-kansas-defers-feds-more-anyone.

Freudenberg, N., Franzosa, E., Sohler, N., Li, R., Devlin, H., and Albu, J. (2015). The State of Evaluation Research on Food Policies to Reduce Obesity and Diabetes Among Adults in the United States, 2000-2011. Prev. Chronic Dis. 12, E182. doi:10.5888/pcd12.150237

Gordon, C., and Hunt, K. (2019). Reform, Justice, and Sovereignty: A Food Systems Agenda for Environmental Communication. Environ. Commun. 13 (1), 9–22. doi:10.1080/17524032.2018.1435559

Haddow, K. S. (2019). Local Control Is Now "Loco" Control. Environ. L. Reporter 49 (8), 10767–10771.

Hanna, J. (2014). Kansas Lawmakers Ok Bill to Void Local Gun Rules. April 6. Topeka, KS: Associated Press State & Local.

Hart, R. P., Daughton, S. M., and LaVally, R. (2018). Modern Rhetorical Criticism. New York, NY: Routledge.

Healy, S. (2009). Toward an Epistemology of Public Participation. J. Environ. Manage. 90 (4), 1644–1654. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2008.05.020

Hicks, W. D., Weissert, C., Swanson, J., Bulman-Pozen, J., Kogan, V., Riverstone-Newell, L., et al. (2018). Home Rule Be Damned: Exploring Policy Conflicts between the Statehouse and City Hall. PS. Polit. Sci. Polit. 51, 26–38. doi:10.1017/S10490965170014211

Hiltzik, M. (2016). Cable and Telecom Firms Score a Huge Win in Their War to Kill Municipal Broadband. August 12. Los Angeles, CA: Los Angeles Times. Available at: http://www.latimes.com/business/hiltzik/la-fi-hiltzik-cable-municipal-broadband-20160812-snap-story.html#.

Hodge, J. G., and Corbett, A. (2016). Legal Preemption and the Prevention of Chronic Conditions. Prev. Chronic Dis. 13, E85. doi:10.5888/pcd13.160121

Hunt, K. P., Senecah, S., Walker, G. B., and Depoe, S. P. (2019). “Introduction: From Public Participation to Community Engagement—And Beyond,” in Breaking Boundaries: Innovative Practices in Environmental Communication and Public Participation. Editors K. P. Hunt, G. B. Walker, and S. P. Depoe (Albany, NY: State University of New York Press), 1–16.

Koutnik, G. (2021). Ecological Populism: Politics in Defense of Home. New Polit. Sci. 43 (1), 46–66. doi:10.1080/07393148.2021.1880702

Larson, N. I., Story, M. T., and Nelson, M. C. (2009). Neighborhood Environments. Am. J. Prev. Med. 36 (1), 74–81. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2008.09.025

Lawrence, R. G. (2004). Framing Obesity. Harv. Int. J. Press/Politics 9 (3), 56–75. doi:10.1177/1081180X04266581

Lee, M. J. (2006). The Populist Chameleon: The People's Party, Huey Long, George Wallace, and the Populist Argumentative Frame. Q. J. Speech 92 (4), 355–378. doi:10.1080/00335630601080385

Leff, M. C. (1983). The Topics of Argumentative Invention in Latin Rhetorical Theory from Cicero to Boethius. Rhetorica: A J. Hist. Rhetoric 1, 23–44. doi:10.1525/rh.1983.1.1.231

LeGreco, M. (2012). Working with Policy: Restructuring Healthy Eating Practices and the Circuit of Policy Communication. J. Appl. Commun. Res. 40 (1), 44–64. doi:10.1080/00909882.2011.636372

Mansbridge, J., Bohman, J., Chambers, S., Estlund, D., Fllesdal, A., Fung, A., et al. (2010). The Place of Self-Interest and the Role of Power in Deliberative Democracy*. J. Polit. Philos. 18 (1), 64–100. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9760.2009.00344.x

Merry, M. K. (2010). Emotional Appeals in Environmental Group Communications. Am. Polit. Res. 38 (5), 862–889. doi:10.1177/1532673x09356267

O’Connor, A., and Sanger-Katz, M. (2018). The Upshot: California, of All Places, Has Banned Soda Taxes. How a New Industry Strategy Is Succeeding. June 27. New York, NY: The New York Times. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/06/27/upshot/california-banning-soda-taxes-a-new-industry-strategy-is-stunning-some-lawmakers.html.

Pomeranz, J. L., Zellers, L., Bare, M., and Pertschuk, M. (2019). State Preemption of Food and Nutrition Policies and Litigation: Undermining Government's Role in Public Health. Am. J. Prev. Med. 56 (1), 47–57. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2018.07.027

Preetika, R. (2020). Airbnb's IPO Warning: Unhappy Neighbors Are Fighting Back. New York, NY: Wall Street Journal. Available at: https://www.wsj.com/articles/airbnbs-ipo-warning-unhappy-neighbors-are-fighting-back-11607533225.

Riverstone-Newell, L. (2018). State Preemption as Scalpel and Sword. PS. Polit. Sci. Polit. 51 (1), 30–31. doi:10.1017/S1049096517001421

Roberto, C., and Gorski, M. (2015). Public Health Policies to Encourage Healthy Eating Habits: Recent Perspectives. Jhl 7, 81–90. doi:10.2147/jhl.s69188

Ruhl, J. B. (2000). Farms, Their Environmental Harms, and Environmental Law. EcologyLaw Q. 27 (2), 263–350.

Sauer, B. A. (1993). Sense and Sensibility in Technical Documentation. J. Business Tech. Commun. 7 (1), 63–83. doi:10.1177/1050651993007001004

Scharff, E. A. (2017). Hyper Preemption: A Reordering of the State-Local Relationship. Georgetown L. J. 106 (5), 1469–1522.

Schnurer, M. (2012). “Parsing Poverty: Farm Subsidies and American Farmland Trust,” in The Rhetoric of Food: Discourse, Materiality, and Power. Editors J. J. Frye, and M. S. Bruner (New York, NY: Routledge), 89–102.

Seiler, A. (2012). “Let’s Move : The Ideological Constraints of Liberalism on Michelle Obama’s Obesity Rhetoric,” in The Rhetoric of Food: Discourse, Materiality, Power. Editors J. J. Frye, and M. S. Bruner (New York, NY: Routledge), 155–170. doi:10.4324/9780203113455-17

Singer, R. (2011). Anti-corporate Argument and the Spectacle of the Grotesque Rhetorical Body in Super Size Me. Crit. Stud. Media Commun. 28, 135–152. doi:10.1080/15295036.2011.553724

Sleat, M. (2013). Hope and Disappointment in Politics. Contemp. Polit. 19 (2), 131–145. doi:10.1080/13569775.2013.785826

Steiner, J. (2012). The Foundations of Deliberative Democracy: Empirical Research and Normative Implications. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Stohl, C., and Cheney, G. (2001). Participatory Processes/Paradoxical Practices. Manage. Commun. Q. 14 (3), 349–407. doi:10.1177/0893318901143001

Swaim, C., and Asbury, N. (2020). Kansas Bill Would Stop Wichita from Banning Plastic Bags. February 21. Wichita, KS: The Wichita Eagle. Available at: https://www.kansas.com/news/politics-government/article240519541.html#storylink=cpy.

Taylor, D. (2014). Toxic Communities: Environmental Racism, Industrial Pollution, and Residential Mobility. New York, NY: NYU Press.

Thomson, D. M. (2009). Big Food and the Body Politics of Personal Responsibility. South. Commun. J. 74, 2–17. doi:10.1080/10417940802360829

Usher, M. (2013). Defending and Transcending Local Identity through Environmental Discourse. Environ. Polit. 22 (5), 811–831. doi:10.1080/09644016.2013.765685

Volland, C. (2018). Kansas Legislature Passes Bill Favoring Big Chicken. April 29. Overland Park, KS: Sierra Club Kansas Chapter. Available at: http://kansas.sierraclub.org/kansas-legislature-passes-bill-favoring-big-chicken/.

Walker, R. E., Keane, C. R., and Burke, J. G. (2010). Disparities and Access to Healthy Food in the United States: A Review of Food Deserts Literature. Health & Place 16 (5), 876–884. doi:10.1016/j.healthplace.2010.04.013

Wentling, N. (2016). City Commission Responds to Kansas Senate Bill Targeting Lawrence’s Affordable Housing Ideas. February 23. Lawrence, KS: Lawrence Journal-World. Available at: https://www2.ljworld.com/news/2016/feb/23/city-commission-responds-kansas-senate-bill-target/.

Whitsel, L. P. (2017). Government's Role in Promoting Healthy Living. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 59 (5), 492–497. doi:10.1016/j.pcad.2017.01.003

Yackee, S. W. (2006). Sweet-talking the Fourth Branch: The Influence of Interest Group Comments on Federal Agency Rulemaking. J. Public Adm. Res. Theor. 16 (1), 103–124. doi:10.1093/jopart/mui042

Keywords: preemption, food policy, agricultural policy, rhetoric, common good, special interest, inclusion, topoi (argumentation schemes)

Citation: Lind CJ and Reeves ML (2021) Making Food-Systems Policy for Local Interests and Common Good. Front. Commun. 6:690149. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2021.690149

Received: 02 April 2021; Accepted: 11 August 2021;

Published: 10 September 2021.

Edited by:

Constance Gordon, San Francisco State University, United StatesReviewed by:

Nicholas Paliewicz, University of Louisville, United StatesJoe Quick, University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee, United States

Copyright © 2021 Lind and Reeves. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.