- 1Institute for Transportation, Iowa State University, Ames, IA, United States

- 2English Department, Iowa State University, Ames, IA, United States

The use of suprasegmental cues to word stress occurs across many languages. Nevertheless, L1 English listeners' pay little attention to suprasegmental word stress cues and evidence shows that segmental cues are more important to L1 English listeners in how words are identified in speech. L1 English listeners assume strong syllables with full vowels mark the beginning of a new word, attempting alternative resegmentations only when this heuristic fails to identify a viable word string. English word stress errors have been shown to severely disrupt processing for both L1 and L2 listeners, but not all word stress errors are equally damaging. Vowel quality and direction of stress shift are thought to be predictors of the intelligibility of non-standard stress pronunciations—but most research so far on this topic has been limited to two-syllable words. The current study uses auditory lexical decision and delayed word identification tasks to test a hypothesized English Word Stress Error Gravity Hierarchy for words of two to five syllables. Results indicate that English word stress errors affect intelligibility most when they introduce concomitant vowel errors, an effect that is somewhat mediated by the direction of stress shift. As a consequence, the relative intelligibility impact of any particular lexical stress error can be predicted by the Hierarchy for both L1 and L2 English listeners. These findings have implications for L1 and L2 English pronunciation research and teaching. For research, our results demonstrate that varied findings about loss of intelligibility are connected to vowel quality changes of word stress errors and that these factors must be accounted for in intelligibility research. For teaching, the results indicate that not all word stress errors are equally important, and that only word stress errors that affect vowel quality should be prioritized.

Introduction

Word stress, also called lexical stress, refers to a phonological feature of all multisyllabic words in a variety of languages, including English. Word stress is critical in how listeners identify words in the stream of speech, and misplaced stress can make words unintelligible; that is, listeners may misidentify the intended word or they may not identify it at all (Benrabah, 1997). Stressed syllables have thus been called “islands of reliability” in word identification (Dechert, 1984, p. 227; see also Field, 2005). In other words, stress imposes formulaic phonological patterns that make speech processing easier for listeners. When these expected patterns are not followed, listeners must put forth more effort for understanding (that is, words become less comprehensible) or understanding becomes impossible (that is, words become unintelligible).

Not all languages use stress to mark word prosody. Some use tone (e.g., Chinese, Thai), some pitch accents (e.g., Japanese, Swedish), and some have no identifiable word prosody (e.g., Korean, French). Of the languages with word stress, some have fixed stress (e.g., Polish, Hungarian), in which the same syllable is stressed in all words. For example, Hungarian words have the main stress on the initial syllable and Polish words on the penultimate syllable. Other languages have variable or free word stress, which means that stress occurs initially for some words, finally for others, and on the penultimate or antepenultimate syllable for yet others (e.g., PHOtograph, eLECtrical, ecoNOmic, questionNAIRE). Besides English, other free stress languages include Dutch, German, Spanish, Italian, and Russian.

Word stress in English can be signaled by multiple prosodic cues, including syllable length (i.e., duration), pitch (i.e., fundamental frequency), and loudness (i.e., amplitude). Each of these cues can signal distinctions in word stress by itself (Zhang and Francis, 2010) or in conjunction with the other cues, but the default cue used by L1 English listeners to identify stressed syllables is not prosodic but rather segmental—vowel quality. In other words, L1 English listeners, in evaluating whether a syllable is stressed, pay attention first to its vowel quality (Cutler, 2015). If the vowel is full, listeners judge it as stressed. If the vowel is reduced to schwa, listeners do not judge it as stressed. This tendency to evaluate full vowels as stressed extends even to unstressed full vowels, such as the initial vowel in audition (Fear et al., 1995). In other languages with vowel quality as a cue to stress, such as Dutch, vowels are not as reliable a stress cue as in English (Cutler et al., 2007). Other variable stress languages like Spanish do not use vowel quality as a cue to stress (Soto-Faraco et al., 2001).

When L2 learners learn a language with word stress, they face a variety of challenges in signaling stress so that listeners find stress to be an island of reliability. If the L2 learner comes from a language with another word prosody, or if they come from a language that has no word prosody, they must learn an entirely new system. If they come from a language with word stress, they need to learn both to hear and produce a new stress system with a new set of cues.

Misplaced stress can result in reduced comprehensibility or unintelligibility. But misplaced stress does not always seriously damage understanding. Slowiaczek (1990) found that changes in stress placement without a change in vowel quality (e.g., CONcenTRATE → CONcenTRATE) resulted in somewhat slower processing, but the words were successfully understood. Cutler (1986) found that hearing one member of stress minimal pairs such as INsight/inCITE and INsult/inSULT activated both words for listeners, resulting in no loss of processing time. In other cases, misplaced stress results in L1 English listeners hearing different words altogether. Benrabah (1997) described British listener transcriptions of English words spoken by Indian, Nigerian, and Algerian speakers. Unexpected stress patterns caused listeners to hear completely different words: UPset (with initial stress) was transcribed as absent (also with initial stress), riCHARD as the child, and seCONdary was heard as country. In other words, stress remained an island of reliability for listeners—but they identified the wrong island. When word stress errors cause loss of understanding is thus an open question that has implications both for phonological research and for L2 language teaching and learning.

Literature Review

Stress in English

English is a free or variable stress language. Although in principle multisyllabic words can have the main stress on any syllable, each multisyllabic word has an expected stress pattern. English speakers employ several criteria when deciding how to stress words. Guion et al. (2003) used two-syllable non-sense words to determine that stress decisions are phonologically conditioned, affected by word class, and related by analogy with other visually or phonologically similar words. They found that heavy syllables (CVV, CVCC) were more likely to attract stress than light syllables (CV, CVC), that noun and verb frames (e.g., I'd like a ____ vs. I'd like to _____) affected stress decisions differently, and that unknown words are likely to be stressed similarly to familiar, look-alike words.

Stress in longer words in English is often morphologically conditioned. Words that are etymologically related may be stressed differently based on affixes (e.g., eLECtric, elecTRIcity, electrifiCAtion), especially suffixes (Chomsky and Halle, 1968; Dickerson, 1989). In almost all cases, these varied stress patterns become part of the cognitive representation of words, allowing listeners to efficiently access the vocabulary stored in their mental lexicon (Cooper et al., 2002).

Of the four acoustic correlates associated with English word stress—vowel quality, duration, pitch change, and variation in amplitude/intensity/volume, vowel quality [i.e., the distinction between clear (uncentralized/unreduced) and reduced (centralized) vowels] has repeatedly been found the most reliable cue to English word stress (Bond, 1981, 1999; Bond and Small, 1983; Cutler and Clifton, 1984; Cutler, 1986, 2015; Small et al., 1988; Fear et al., 1995; van Leyden and van Heuven, 1996; Cooper et al., 2002; Field, 2005; Cutler et al., 2007; Zhang and Francis, 2010). Reduced (centralized) vowels are never associated with stress.

L2 Speakers and Word Stress

L2 speakers of English and other free stress languages can find stress difficult to perceive and produce. This is true even when they speak another free stress language (Maczuga et al., 2017) although this background does facilitate L2 stress learning (Lee et al., 2019). L1 and the age at which L2 speakers learn English are important factors in stress acquisition. The intuitions of early and late bilingual L2 Korean and Spanish speakers were shown to differ in how stress was applied to unfamiliar two-syllable English words (Guion et al., 2004; Guion, 2005). The intuitions of late bilinguals were less like L1 speakers than those of early bilinguals.

L1 can be a dominant factor in how L2 speakers navigate word stress in free stress languages. In the case of French speakers learning Spanish (a free-stress language), Dupoux et al. (2008) asserted that the learners exhibited stress “deafness” in perception of Spanish stress (p. 700). The same difficulties have been reported for French L1 speakers in English stress production (Isaacs and Trofimovich, 2012). Even L1 speakers of free stress languages may not fully be able to use their stress identification abilities when learning other free-stress languages Ortega-Llebaria et al. (2013) found that English speakers were generally sensitive to differences in Spanish stress, but they still struggled to quickly identify differences in Spanish because of contextual stress deafness.

Effects of Misplaced Word Stress on Intelligibility and Comprehensibility

Stress is critical in how L1 English listeners identify words in the stream of speech. Because 90% of lexical (i.e., content) words in spoken English begin with an initially stressed syllable (Cutler and Carter, 1987), L1 listeners treat stressed (or “strong”) syllables as marking the first syllable of a new word (Cutler and Norris, 1988; Cutler and Butterfield, 1992). It is no surprise, therefore, that lexical stress errors affect intelligibility and comprehensibility for L1 English listeners because listeners are trying to identify words without being able to identify the first syllable (Kenworthy, 1987; Brown, 1990; Anderson-Hsieh et al., 1992; Dalton and Seidlhofer, 1994; Jenkins, 2000; Field, 2005; Zielinski, 2008; Isaacs and Trofimovich, 2012).

By intelligibility and comprehensibility, we intend Munro and Derwing's (1995) definitions. Comprehensibility is the degree to which listeners can easily understand a speaker's message—that is, for comprehensibility, words, sentences or discourse can span the continuum of being highly comprehensible to being minimally comprehensible. Standard stress pronunciations are generally highly comprehensible—i.e., quickly and easily understood by listeners—and non-standard stress pronunciations with zero vowel errors can be expected to be more comprehensible than those with more errors (e.g., two vowel errors). Intelligibility, on the other hand, refers to the categorical distinction between intelligible and unintelligible pronunciations. Applied to words, listeners either understand a speaker's intended word or they do not.

Errors in English word stress placement interrupt how L1 listeners understand and process speech, thus affecting both intelligibility and comprehensibility. Zielinski (2008) identified word stress as critical for the intelligibility of L2 English speakers to L1 English listeners in both general and academic contexts. This was observed by having L1 English-speaking participants transcribe the utterances of three different L2 English speakers (L1: Chinese, Korean, Vietnamese). Each of the sentences was extracted from 2-h long interviews on the topic of education because listeners had difficulty transcribing it. Each sentence was phonetically transcribed to identify its phonetic deviations and to compare it with the words that were not transcribed correctly. Whenever there was a loss of intelligibility, Zielinski compared it to the non-standard features of the L2 speaker's pronunciation and concluded that L1 English listeners rely heavily on the lexical stress of L2 speakers to determine their intended meaning. Zielinski found that participant transcriptions maintained the L2 speakers' stress pattern 90% of the time.

Even though stress errors that do not change vowel quality are unlikely to prevent correct word identification, such stress errors can nevertheless force listeners to work harder (that is, cause deterioration of the words' comprehensibility). Slowiaczek (1990) examined the accuracy with which L1 English listeners identified mis-stressed words as real words as well as how quickly listeners repeated words. The study used words with two full vowels in which the stress pattern was switched (e.g., ANgry vs. anGRY) but vowel reduction was not involved. In the identification task, listeners were asked to type each word they heard in quiet and at three different Signal-to-noise (SNR) ratios. Results showed no difference in the accuracy of stressed and mis-stressed words, indicating that when vowel reduction was not involved, listeners successfully identified words despite mis-stressing. Second, listeners were less successful when SNR masking noise was involved, and increasing competition from this noise resulted in less accurate identifications. Third, the majority of the words listeners typed matched the intended word's stress pattern. A second experiment asked listeners to repeat the word they heard. Incorrectly stressed items were responded to more slowly than correctly stressed items, indicating that mis-stressed items interfered with processing.

In another study demonstrating the importance of word stress for comprehensibility, Isaacs and Trofimovich (2012) measured the correlation of 19 linguistic features to L1 English listeners' comprehensibility ratings. Using English picture narratives from 40 L1 French speakers, their goal was to identify the best features to use in an oral language assessment scale for teachers. Of this study's six phonological features, five were significantly correlated with listeners' comprehensibility ratings. Only one, however, word stress, was included in the recommended rating scale because of its high correlation and because teachers identified it as important.

The effect of stress on intelligibility and comprehensibility for L2 English listeners has been much more debated than for L1 English listeners. Largely on the basis of anecdotal evidence, some research has argued that word stress errors are unlikely to result in loss of intelligibility for L2 English listeners (Jenkins, 2000) while others have argued the opposite (Dauer, 2005; McCrocklin, 2012; Lewis and Deterding, 2018). These disagreements raise questions about whether stress errors affect L1 and L2 English listeners differently.

Empirical research suggests that word stress errors can cause loss of intelligibility and/or comprehensibility for both L1 and L2 listeners. Field (2005) developed a list of two-syllable words, half of which were stressed on the first syllable, the other half on the second syllable and recorded each word with standard stress and again with shifted stress. There was also a subset of words with a third condition: shifted stress plus a previously reduced vowel pronounced with full vowel quality. L1 and L2 high-school-aged listeners heard and transcribed the words. For L1 listeners, a shift in stress had a significant negative impact on intelligibility that was lessened if accompanied by full vowel quality. L2 listeners also appeared to follow this general pattern, but once full vowel quality was added, the decrease in intelligibility for L2 listeners was no longer significant. Field also found that stress shifted to the right had a stronger effect on intelligibility than stress shifted to the left.

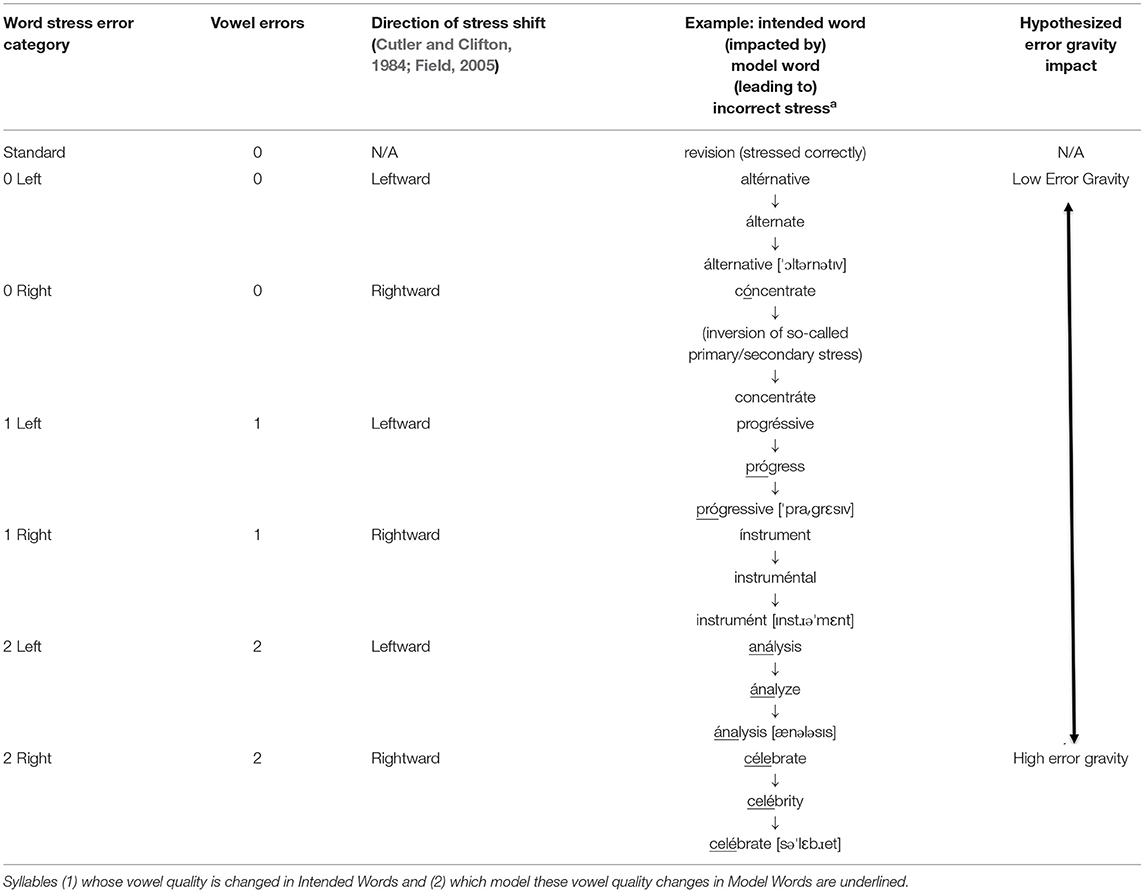

Hypothesizing an English Word Stress Error Gravity Hierarchy

In English, L1 listeners attend primarily to vowel quality in evaluating word stress (Cutler and Clifton, 1984; Cutler, 1986, 2015; Cooper et al., 2002; Cutler et al., 2007). This appears to be due both to stressed vowels signaling the beginnings of words in speech and to the reliability of reduced vowels in eliminating possibilities from a listener's subconscious cohort of possible English words (Cutler, 2012). We thus predict that the success of L1 and L2 English listeners' processing of standard and non-standard English stress pronunciations can be predicted based on the number of vowel errors and direction of the stress shifts. A few studies (Cutler and Clifton, 1984; Field, 2005) have found that English word stress errors pushing stress rightward are more damaging than those pushing stress leftward—possibly because English regularly licenses leftward stress shift for the purpose of discourse-level contrastive stress (Field, 2005). Informed by this empirical evidence, we developed the English Word Stress Error Gravity Hierarchy (Table 1), leading to two research questions:

1. To what extent do L1 and L2 English listeners process English words (mis)pronounced in accord with the Hierarchy?

2. How do number of vowel errors and direction of stress shift help explain the relative intelligibility and comprehensibility of word stress errors for L1 and L2 English listeners?

Methods

Participants

Sixty-nine undergraduates with normal hearing volunteered to participate in this auditory lexical decision (LD) (Cutler, 2012) and word identification (WI) (Barca et al., 2002; Balota et al., 2007; Cutler, 2012; Kuperman et al., 2014) study to earn course credit for their introductory psychology class. Thirty-eight spoke English as an L1 (22 females; mean age = 19.34 years, range = 18–26). Thirty-one spoke English as an L2 (14 females; mean age = 21.42 years, range = 18–27). (In our pilot study, we had attempted to limit variability among L2 listeners by including only those whose L1 was either Chinese or Korean, but our U.S. Midwest university context did not include enough participants from these L2s who were taking introductory psychology to make this feasible. As a result, we opened our study to L2 English speakers more generally).

Materials

All participants heard the same (mostly academic) words but were randomly assigned to either Counterbalance Set A or Set B, whose difference lay in which of each word stress category's 16-word sublists was presented with standard vs. non-standard English word stress. Each 16-word sublist was matched as closely as possible for (1) word frequency (van Heuven et al., 2014), since word frequency has long been known to powerfully influence lexical processing; (2) phonological Levenshtein distance 20 (Balota et al., 2007), a phonological similarity (or edit distance) metric, since the more similar neighbors a spoken word has, the more competition words experience during processing, which leads to reaction time delays, etc.; (3) word frequency of phonological Levenshtein distance 20 neighbors (Balota et al., 2007); (4) number of syllables (Balota et al., 2007); (5) dominant word class (Brysbaert et al., 2012); (6) percentage of dominance for dominant word class (Brysbaert et al., 2012); (7) concreteness (Brysbaert et al., 2014); and (8) word stress pattern frequency as analyzed by this study's first author.

Except with the 0 Right category, derivationally related word family members were used to inform all of this study's non-standard pronunciations because American English has ~14 stressed vowel sounds that are phonemic (Celce-Murcia et al., 2010). Thus, guidance regarding which particular stressed vowel to exchange with a given unstressed vowel (and vice versa) was needed. Because derivationally related words in English often do not have word stress on the same syllables, plausible stressed/unstressed vowel exchanges could be modeled by mapping the word stress pattern of a derivationally related word onto a given manipulated word. Thus, a mis-stressed word may have zero vowel errors (e.g., “altérnative” modeled on álternate to become “álternative”), one vowel error (e.g., “progréssive” modeled on “prógress” to become “prógressive”), two vowel errors (e.g., “económics” modeled on “ecónomy” to become “ecónomics”), etc. In the case of the 0 Right stress manipulation, each counterbalanced sublist manipulated only degree of stress for most words –i.e., exchanging primary vs. secondary stress. For all remaining words (Counterbalance A: 6/16 words; Counterbalance B: 5/16 words), the 0 Right stress manipulation rendered an ordinarily stressed syllable unstressed (“stress” being here defined only suprasegmentally) and an ordinarily unstressed syllable that nevertheless contained a clear (unreduced) vowel stressed (e.g., the word “therapy” pronounced as /′θɛrə′pi/ instead of as its standard pronunciation /′θɛrəpi/).

Transcriptions based on the International Phonetic Alphabet for the General American English pronunciation of all stimuli and of all derivationally related word family members modeling stress manipulations were generally obtained from the Web app Lingorado (Jansz, n.d.). However, in the few cases where Lingorado failed to provide an American English IPA transcription or provided a transcription that violated the authors' American English intuitions, other online dictionaries were checked (Cambridge University Press, 2015; Merriam-Webster, 2015; Oxford University Press, 2015) and standard American English IPA transcriptions were developed or revised accordingly. This study's first author then used Ittiam Systems' free ClearRecord Lite iPhone app to record all stimuli in both their standard stress and manipulated stress forms within one of the following four neutral sentence carrier sentences:

1. The word _____________ is interesting.

2. The answer _____________ is reasonable.

3. The choice _____________ is appropriate.

4. The option _____________ is probable.

Recording stimuli in such neutral recording frames avoided effects from either discourse-level rising intonation (signaling the list of words being recorded was not yet finished) or falling intonation (signaling the last word in the list was now being spoken). Stimuli were recorded within their respective carrier sentences with a slight pause before and after each stimulus word, so it could be excised from the recording without contamination from the preceding or following context. Each pronunciation was then evaluated by this study's first author and, upon her initial approval, by the second author, based on their substantial background in phonetics and phonology. Each pronunciation was evaluated within the context of its particular standard or non-standard stress stimulus set for (1) whether it clearly instantiated the target word stress manipulation, (2) whether it included all segmentals appropriately and clearly pronounced and (3) whether it exhibited comparable suprasegmental markers of stress, speed of speaking, etc. Often, stimuli were recorded multiple times before they were deemed satisfactory.

Procedure

Participants were orally introduced to the experimental procedure approved by our university's Institutional Review Board and provided informed consent. Within a comfortable private cubicle, each was interviewed using an extensive Language Background Questionnaire addressing questions about their child and teenage language experience, about their English-language-learning experience and current daily English usage and proficiency, and about any L3 or L4 languages, etc. (see Richards, 2016, for the full questionnaire). Upon the interviewer initiating the experiment and the leaving the cubicle, the participant read: “In this experiment, you will hear a series of correctly and incorrectly pronounced English words. For each word you hear, you will be asked the question ‘Was this a correctly pronounced English word?'…If the word was correctly pronounced, you should click ‘1' to indicate ‘Yes, this was a CORRECTLY pronounced English word.' If the word was NOT correctly pronounced, you should click ‘2' to indicate ‘No, this was NOT a correctly pronounced English word.'” Seven practice trials preceded the main experiment, after which participants were given a final review of the experiment's directions and encouraged to ask any questions. Each trial included the following steps.

1. Participants were directed to position their hands ready to click either “1” (“yes”) or “2” (“no”) as quickly and accurately as possible.

2. Participants pressed the number “1” when ready to continue and after 100 ms heard through their headset either a word spoken in isolation with standard stress or a word spoken in isolation with one of the Hierarchy's six stress manipulations described earlier. At the same time, he or she saw the prompt on the screen “Was this a correctly pronounced English word? Press the ‘1' key for yes and the ‘2' key for no.”

3. Participants then clicked either “1” or “2” and E-Prime recorded both their LD accuracy and reaction time (RT).

4. Participants were then prompted: “Please type the English word you think the speaker was trying to say and then press ‘enter.' (It's okay if you can't spell it correctly—just spell it as best you can ). If the word was mispronounced and you have NO idea what word the speaker was trying to say, just press the ‘enter' key directly.” E-Prime recorded all characters typed by the participant.

). If the word was mispronounced and you have NO idea what word the speaker was trying to say, just press the ‘enter' key directly.” E-Prime recorded all characters typed by the participant.

The study's counterbalancing involved each L1 and L2 participant listening, in random order, to all of the Appendix 1's set A words spoken with standard stress intermixed with all set B words spoken with manipulated stress, or vice versa (Appendix 2 has the words with their phonetic transcriptions). Our word identification task used typed spellings rather than spoken accuracy as a proxy for word identification because of concerns that, particularly with standard pronunciations, it would otherwise have been impossible to identify whether participants' articulations were grounded in their having successfully identified the intended word or were instead the effect of priming leading to their (likely accidentally) simply repeating what they had heard (cf., Field, 2005).

Analysis

One common challenge faced in studies of L1 and L2 language users (Whelan, 2008) is that L1 participants generally perform relatively homogeneously, whereas L2 performance is characteristically much more variable. The current study was no exception though both groups included outliers. An additional source of variability was the wide-ranging difference in performance found across Hierarchy categories, with both L1 and L2 listeners performing for some Hierarchy categories at ceiling and for one category basically at floor. Although several transformations (i.e., logit, arcsine square root and folded square root transformation for the accuracy data and reciprocal and log-normal transformation for the RT data) were tried, none were particularly effective at addressing the failure of this study's accuracy and RT data to meet ANOVA's homogeneity of variance and normality assumptions. An additional issue with non-linear data transformation is that while it can address questions of rank order, it cannot resolve questions about relative degree of impact (Whelan, 2008; Lo and Andrews, 2015) since, for example, the square root of 25 is 5, of 16 is 4, and of 9 is 3 (i.e., non-linear transformation can render non-equidistant values equidistant). Details of all non-linear data transformations attempted are available from the dissertation of this study's first author (Richards, 2016). Because this study's research questions are not so much about how L1 listeners and L2 listeners perform in relation to each other, but rather about how each group's performance compares to the predictions of our hypothesized English Word Stress Error Gravity Hierarchy, the current paper reports ANOVA analysis of the untransformed L1 and L2 listener groups' data separately. In other words, although we could not justify inferential analysis of the two groups together in light of our L1 and L2 listeners' substantial difference in variance, we relied on ANOVA's noted robustness to normality violations in light of our L1 and L2 groups' respective sample size of >30—as licensed by the Central Limit Theorem that describes how, no matter a particular data distribution's shape (i.e., normal or not), the greater the sample size, the closer the sample means will approximate their respective population means.

Results

Our results from testing the English Word Stress Error Gravity Hierarchy are presented in three parts. First, we report the results for Lexical Decision (LD) accuracy and reaction time in light of hierarchy predictions. These two variables, respectively, measure how accurate listeners were in determining whether words were correctly or incorrectly pronounced and how long it took them to decide. Next, we report the results of the Word Identification (WI) task, in which listeners typed out the word they heard. This task was our proxy measure for the intelligibility of (mis)pronounced words across the hierarchy. For each of this section's three parts, we present the L1 results, the L2 results, and then compare the L1 and L2 listeners. Finally, we look at how our study connects with the few others that have noted that listeners' word stress error processing appears to be predicted not only by the presence or absence of vowel errors, but also by direction of stress shift (Cutler and Clifton, 1984; Field, 2005).

Lexical Decision Accuracy and Reaction Time

The Hierarchy predicts that L1 and L2 English listeners' LD accuracy with the non-standard stress categories relatively close to standard stress will be poor but will progressively improve the further a non-standard stress pronunciation falls from the standard stress category of the Hierarchy. Specifically, it predicts that listeners' LD accuracy will be better for words at the two ends of the hierarchy (i.e., pronounced with a standard pronunciation and those most clearly pronounced with a non-standard pronunciation). The Hierarchy conversely predicts that listeners will exhibit reduced LD accuracy and slower reaction times (RTs) for mis-stressed English words falling into categories in the middle section of the Hierarchy due to struggles in identifying whether these “almost-correctly-pronounced” words have in fact been correctly pronounced.

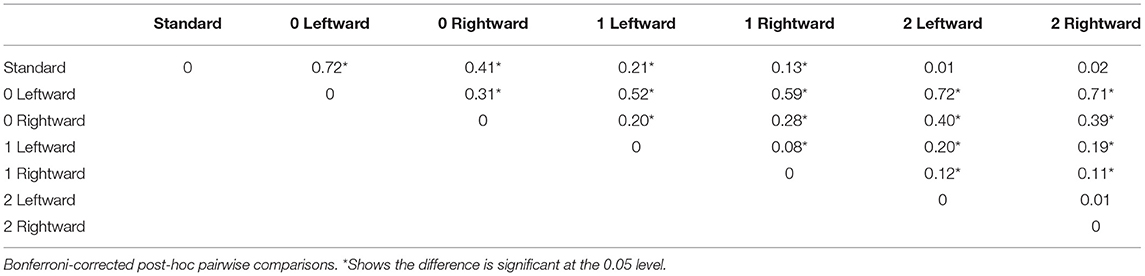

L1 English Listeners' LD Accuracy and LD RT

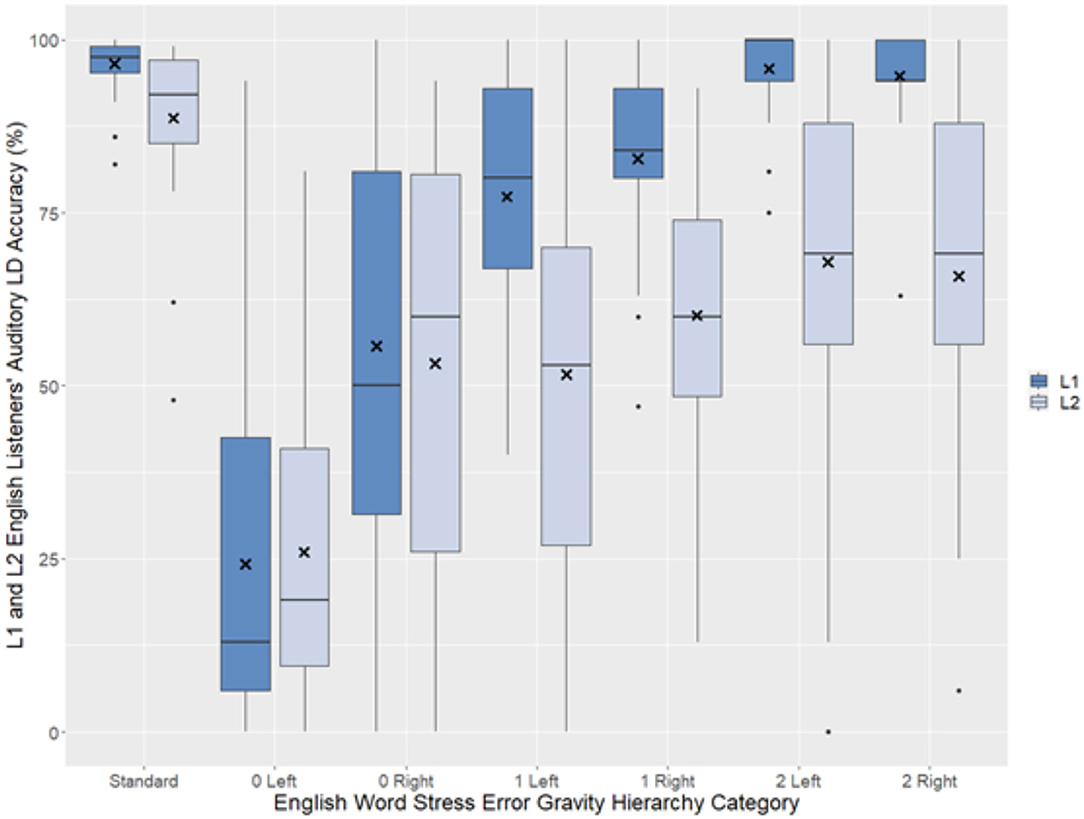

The L1 English listeners' LD accuracy data follow the expected pattern. A significant within-subjects ANOVA with a Greenhouse-Geisser correction, F(2.33, 86.19) = 136.98, p < 0.001, and very large partial η2 effect size show that 79% of the variance in L1 English listeners' LD accuracy can be attributed to Hierarchy category. Bonferroni-corrected pairwise comparisons of the percentage of mean difference between Hierarchy categories, as shown in Table 2, demonstrate that the L1 English listeners were nearly 100% accurate at identifying English words pronounced with standard stress as instantiating a standard pronunciation, and they were similarly nearly 100% accurate at recognizing basically all 2-vowel-error non-standard pronunciations as being non-standard. In contrast, their LD accuracy with the middle-of-the-Hierarchy non-standard stress categories was poor.

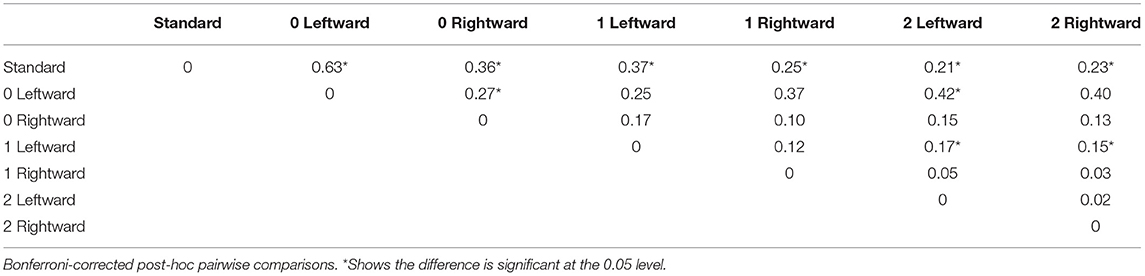

Table 2. Percentage of mean difference between pairs of hierarchy categories in L1 listeners' LD accuracy.

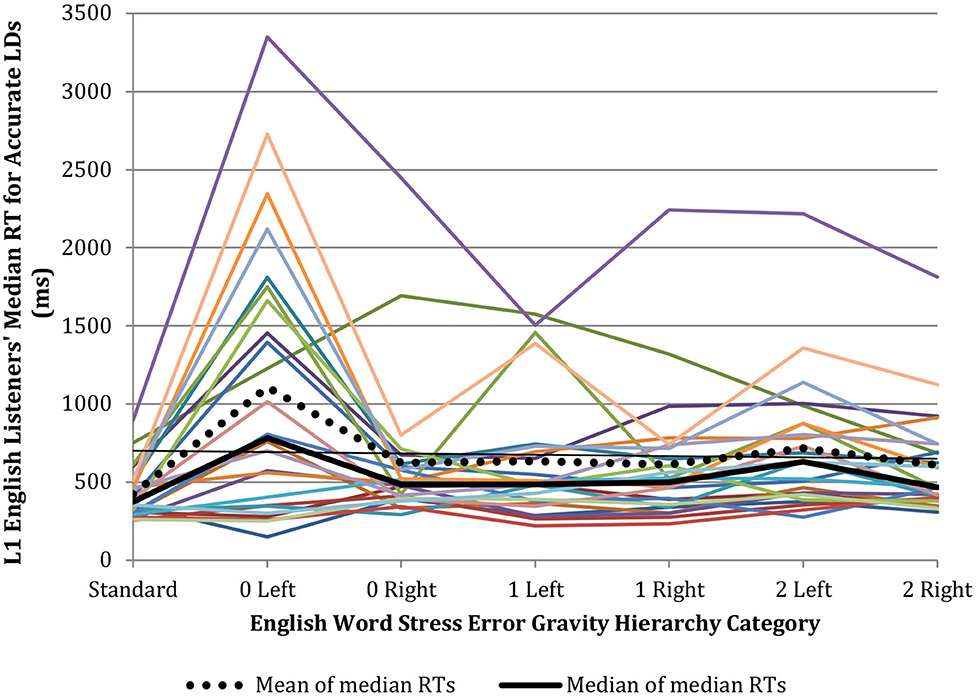

In terms of LD RT, seven of the L1 English listeners inaccurately rated all 0 Left non-standard pronunciations as instantiating “a correctly pronounced English word.” As a result, they had no RT associated with an accurate LD for the 0 Left category. Seven other L1 English listeners rated only one 0 Left non-standard pronunciation as non-standard and therefore had only one RT associated with an accurate LD for the 0 Left category. Therefore, LD RT data across all categories of the Hierarchy was available for submission to statistical analysis for only 24 of our 38 L1 English listeners. For these 24 L1 listeners, Bonferroni-corrected pairwise comparisons make clear their significant within-subjects ANOVA with a Greenhouse-Geisser correction, F(3.54, 120.27) = 9.47, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.218, is merely the characteristic artifact of the LD task that is predicted by the Dual Route Cascaded model, namely that accurate “Yes” responses will be faster and less variable (i.e., responding to standard stress stimuli with a “Yes” LD) than accurate “No” responses (i.e., responding to non-standard stress stimuli with a “No” LD) (Coltheart et al., 2001; Cutler, 2012). Specifically, as Figure 1 suggests, the RTs associated with L1 English listeners' increasingly greater number of accurate “No” LDs across the 0 Right−2 Right non-standard stress categories of the Hierarchy were statistically equivalent, indicating that across these non-standard stress categories, the mental cost of performing the LD task, as indexed by RT, was stable.

Figure 1. Parallel coordinate plot of median accurate auditory LDRT for L1 English listeners with 2+ accurate LDs per Hierarchy category (n = 24).

However, there is one telling exception to this overall RT trend. Although these 24 more sensitive L1 English listeners ultimately succeeded at identifying 0 Left non-standard stress pronunciations as non-standard, Bonferroni-corrected pairwise comparisons show this success came at a significant RT cost (median RT = 783 ms) relative to all Hierarchy categories except 2 Left. In other words, not only was the L1 English listeners' LD accuracy extremely low in recognizing 0 Left mis-stressings as non-standard, but on the rare occasions when they did succeed, the price tag was prolonged mental debate. L1 listeners' barely 50% LD accuracy and significantly slower median RT (=521 ms) when identifying the 0 Right mis-stressings as non-standard similarly contrasts with their nearly 100% accuracy and 365 ms median RT in recognizing each of the study's standard stress pronunciations as a “correctly pronounced English word.”

These findings are not surprising since previous research has made it clear L1 English listeners have difficulty utilizing the suprasegmental word stress cues of duration, pitch and intensity that are often redundant with the more salient vowel quality cue (Cooper et al., 2002; Cutler et al., 2007). After all, this study's 0 Left and 0 Right Hierarchy-defined non-standard stress pronunciations offered only these suprasegmental word stress cues. It is also no surprise the L1 English listeners struggled particularly to identify 0 Left word stress shifts as non-standard since, as mentioned earlier, English regularly licenses leftward stress shift for the purpose of discourse-level contrastive stress (Field, 2005).

Yet these LD accuracy and LD RT findings in conjunction with such research raised the following question: To what extent was the L1 English listeners' definition of a “correctly pronounced English word” broad enough to accommodate the 0 Left and/or 0 Right Hierarchy-defined non-standard stress pronunciations that offer solely suprasegmental word stress cues?

Post-hoc analysis by reverse-coding L1 listeners' Hierarchy-defined inaccurate LDs for the 0 Left and 0 Right categories as accurate and their Hierarchy-defined accurate LDs for these two suprasegmentally-demarcated categories as inaccurate allowed us to model this question. However, we removed in our reverse-coded LD RT analysis the most suprasegmentally sensitive L1 English listeners who made either zero or only one 0 Left or 0 Right Hierarchy-defined inaccurate LD. Bonferroni-corrected pairwise comparisons confirmed that for the remaining typical L1 English participants (n = 32), there was no significant difference in their median RT for indicating that standard stress pronunciations in comparison to 0 Left mispronunciations represented “correctly pronounced English word(s).” For the 0 Right stimuli, this post-hoc analysis revealed that their median 0 Right accurate LD RT and inaccurate LD RT were significantly slower than their median RT for accurate standard stress LDs. In sum, for the most part, L1 listeners did not hesitate to classify 0 Left pronunciations as “correctly pronounced English words,” but they struggled to determine whether 0 Right mis-stressings had been pronounced correctly or incorrectly, no matter what their ultimate decision. Thus, L1 listeners' sensitivity to the suprasegmental correlates of English lexical stress depended on the direction of stress shift.

L2 English Listeners' LD Accuracy and LD RT

The L2 listeners' LD accuracy data visually follow a similar pattern to that of the L1 listeners (Figure 2), though apparently from a lower baseline and, as is frequently the case in studies involving L1 and L2 language users (Whelan, 2008), with much greater variability.

Figure 2. Auditory LD accuracy by Hierarchy category for L1 (n = 38) and L2 (n = 31) English listeners. “X” marks the sample mean and center lines the median of listeners' individual mean LD accuracy, box limits indicate the interquartile range, whiskers contain all sample values within 1.5 times the interquartile range, and outliers are represented by dots.

A significant within-subjects ANOVA with a Greenhouse-Geisser correction, F(3.39, 101.81) = 37.75, p < 0.001, and very large partial η2 effect size show that 56% of the variance in L2 English listeners' LD accuracy data can be attributed to Hierarchy category. This effect size is impressive given that, for the 1 Left and 2 Left categories, L2 listeners' scores range all the way from 0 to 100%. Bonferroni-corrected pairwise comparisons, displayed in Table 3, show this large effect size is due to L2 listeners' performance with the standard stress and 0 Left Hierarchy categories being reliably different from all other Hierarchy categories and the 1 Left category reliably different from all other categories except the immediately adjacent categories 0 Right and 1 Right.

Table 3. Percentage of mean difference between pairs of hierarchy categories in L2 listeners' LD accuracy.

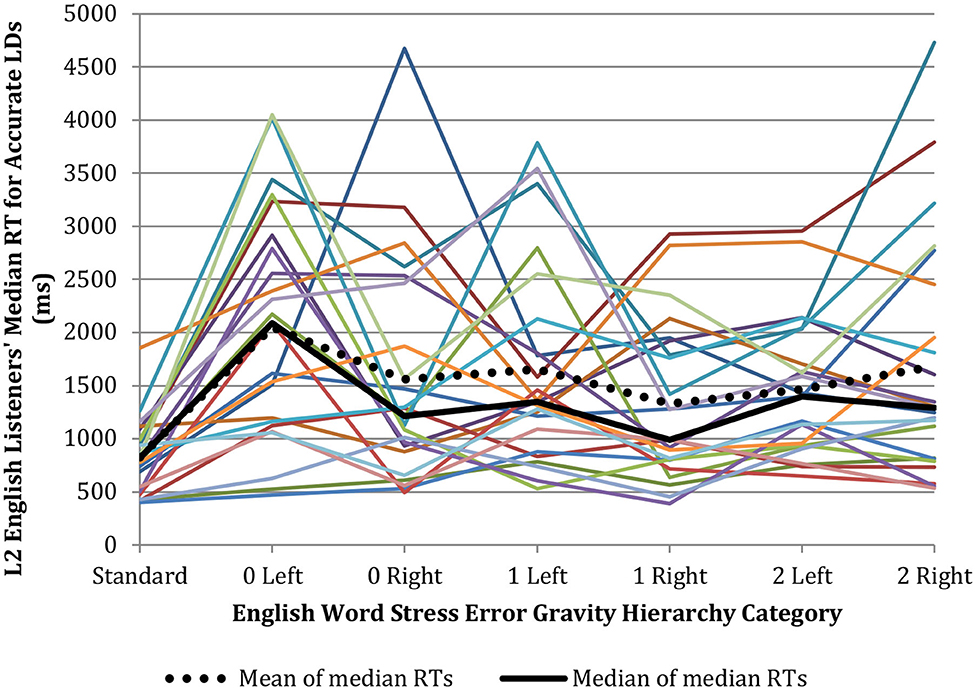

In terms of LD RT, L2 English listeners' median accurate 0 Left LD RT represents an ~850 millisecond increase in processing time over their median accurate LD RT for all other non-standard stress categories. It thus visually appears (Figure 3) that in cases when L2 listeners were able to make a Hierarchy-defined accurate LD with the 0 Left pronunciations, they paid an RT cost to do so. However, while within-subjects ANOVA with a Greenhouse-Geisser correction run on L2 English listeners' LD RT data was significant F(4.12, 90.57) = 7.34, p < 0.001, and had a large partial η2 effect size of 0.25, Bonferroni-corrected pairwise comparisons indicate L2 English listeners' only significant accurate auditory LDRT result, perhaps due to their overall wide variability, is that predicted by Dual Route Cascaded Model finding, namely that accurate “Yes” responses are faster and less variable than accurate “No” responses (Coltheart et al., 2001; Cutler, 2012).

Figure 3. Median accurate auditory LDRT for L2 English listeners with 2+ accurate LDs per Hierarchy category (n = 23).

L1 vs. L2 English Listeners' LD Accuracy and LD RT

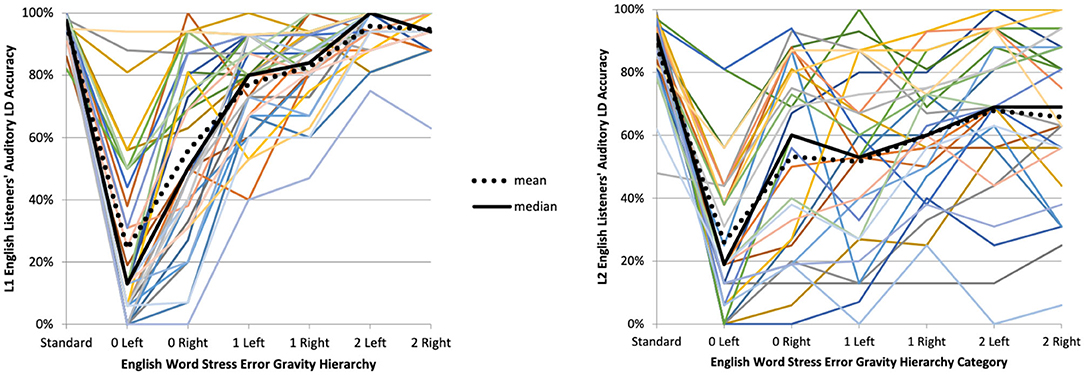

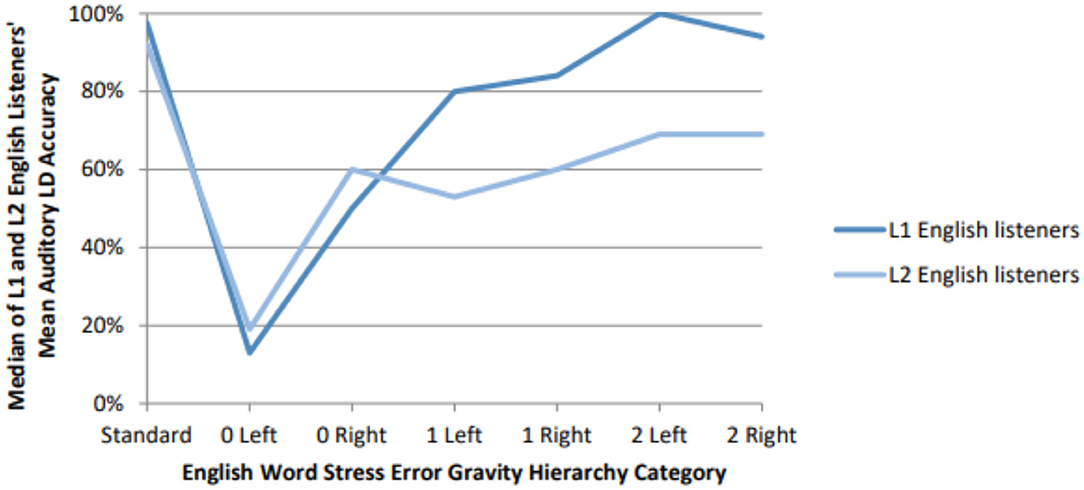

While the visual similarity in L1 and L2 listeners' LD accuracy data seen in Figure 2—and even more unmistakably in Figure 4—is intriguing, as mentioned earlier, it was impossible to test the significance of this potential LD accuracy difference because the L1 vs. L2 listener data strongly violated ANOVA's homogeneity of variance assumption.

Figure 4. Auditory lexical decision (LD) accuracy by English Word Stress Error Gravity Hierarchy category for L1 (n = 38, left) and L2 (n = 31, right) English listeners.

What should be noted from Figure 2 about L1 and L2 listeners' LD accuracy, however, is that L2 listeners' interquartile range barely overlaps with that of L1 English listeners for all non-standard stress categories in which an English word stress error induces one or more concomitant vowel errors. In other words, the L2 English listeners did not merely follow L1 English listeners' performance from a lower baseline. Rather, the further an English word stress error fell from the standard stress category of the Hierarchy, the more L2 listeners' LD accuracy was hurt in comparison to that of L1 listeners.

Also, one additional point for future research should be noted. For most Hierarchy categories, as one might expect, L2 listeners' mean and median LD accuracy is lower than that of L1 listeners. However, the L2 listeners' mean LD accuracy in Figure 4 for the 0 Left and 0 Right categories almost exactly mirrors that of L1 listeners—and L2 listeners' median LD accuracy in Figure 5 actually exceeds that of L1 listeners. How can this be?

Figure 5. Median of L1 (n = 38) and L2 (n = 31) English listeners' mean auditory LD accuracy by Hierarchy category.

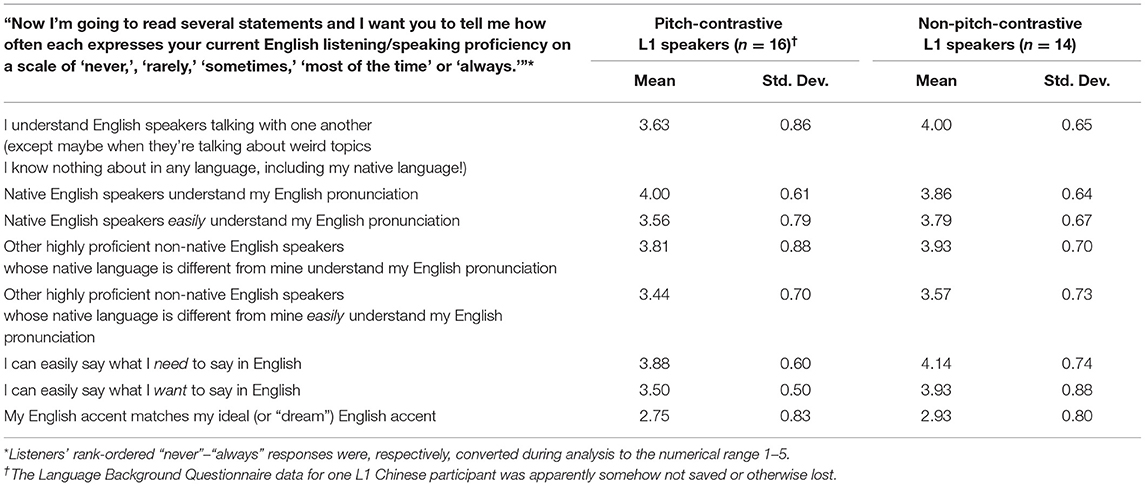

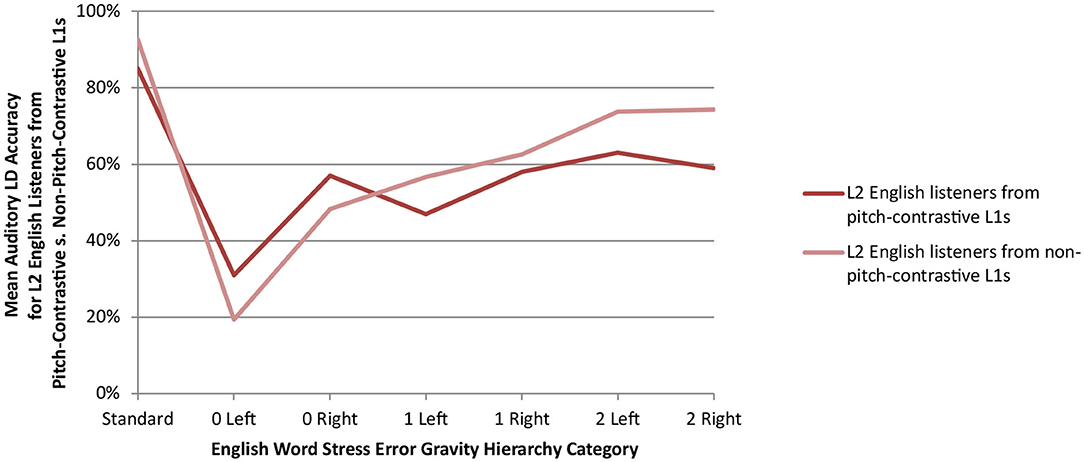

Post-hoc analysis of the L2 English listeners' Language Background Questionnaire data suggests this anomaly may be explained by the fact that the “L2 listener” group subsumed both those from pitch-contrastive and non-pitch-contrastive L1s. Specifically, 17 of our L2 listeners were from either a tonal or pitch-accent L1 (Chinese n = 11, Vietnamese n = 4, Lao n = 1, and Japanese n = 1) and 14 were from a non-tonal, non-pitch-accent L1 (Arabic n = 3, Korean n = 3, Malay n = 2, Spanish n = 2, Czech n = 1, Indonesian n = 1, Turkish n = 1, and Urdu n = 1). Largely in accord with L2 listeners' self-assessed English listening and speaking proficiency (Table 4), the pitch-contrastive L1 listeners' LD accuracy appears generally lower across Hierarchy categories than that of the non-pitch-contrastive L1 listeners—a finding one of our reviewers has suggested may be due to English including several short (lax) vowels that are not part of many East Asian languages' vowel inventory, making it difficult for speakers of these languages to accurately determine whether English words containing these short vowels have or have not been correctly pronounced.

Table 4. Responses to Language Background Questionnaire's Self-Assessment of English Listening and Speaking Proficiency.

Specifically, the only two English Word Stress Error Gravity Hierarchy categories where the tonal or pitch-accent L1 listeners apparently outperform not only their non-tonal, non-pitch-accent L1 peers (Figure 6), but also L1 English listeners (Figure 5) are the two categories where only the suprasegmental cues to non-standard stress—including the pitch cue—were available. In other words, as is characteristic of L2 speech processing generally (Cutler, 2012), retaining their L1 speech processing strategy of closely attending to the pitch cue apparently served pitch-contrastive L1 listeners well for these two Hierarchy categories. While this study's small sample size for pitch-contrastive vs. non-pitch-contrastive L1 listeners made it impossible to test the significance of their apparent LD accuracy differences, future research investigating this apparent phenomenon would be of interest.

Figure 6. Mean auditory LD accuracy for L2 English listeners' from pitch-contrastive L1s (n = 17) and non-pitch-contrastive L1s (n = 14) by Hierarchy category.

Word Identification Accuracy

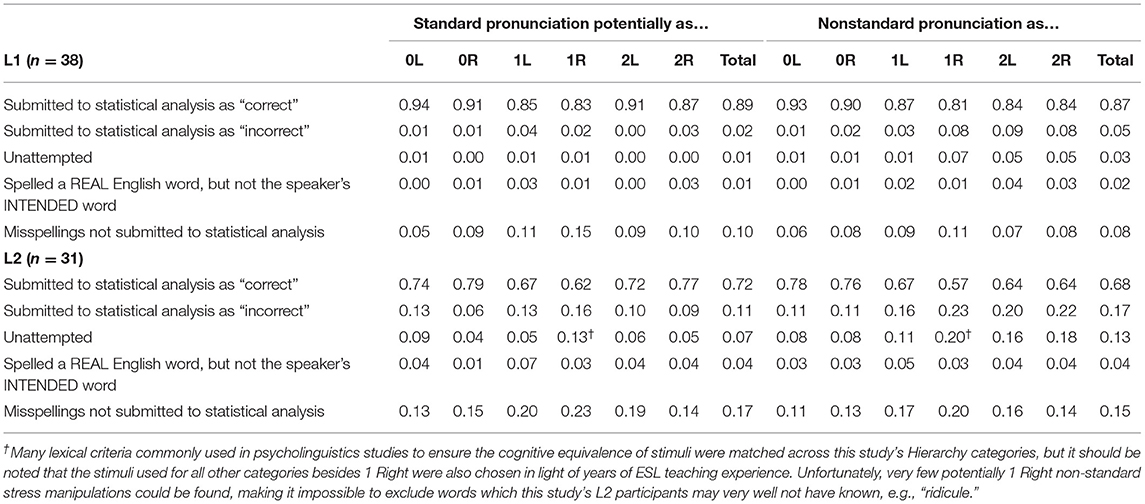

The English Word Stress Error Gravity Hierarchy predicts that L1 and L2 English listeners should generally be able to recognize a speaker's intended word for English words pronounced with standard stress or pronounced with non-standard stress that is marked only suprasegmentally (Bond and Small, 1983; Cutler and Clifton, 1984; Cutler, 1986; Small et al., 1988; Fear et al., 1995; Jenkins, 2000; Cooper et al., 2002; Field, 2005). However, the further a non-standard stress pronunciation falls from the standard stress category of the Hierarchy, the more intelligibility is expected to decrease and therefore the less accurate word identification (WI) accuracy should become. Inaccurate WI was defined in this study as either (1) not attempting at all to spell a speaker's intended word or (2) spelling a real English word other than what the speaker intended. Typos consisting only of added non-alphabetic characters were counted as instances of accurate WI. Other misspellings were deleted from the data prior to WI accuracy analysis, since it was oftentimes impossible to decide objectively whether they represented (1) listeners' misspelling of the speaker's intended word that they had in fact accurately identified or (2) listeners' attempt to spell phonetically what they had heard, a response likely on at least some occasions because most non-standard pronunciations had been modeled on the standard pronunciation of a derivationally-related word family member and therefore likely sounded somewhat familiar to listeners. After all, while some misspellings appeared to be minor misspellings, e.g., “affectionite” for “affectionate” pronounced as [ˈæfɛk∫ənət] and other misspellings were interesting in terms of this study's research questions, e.g., “mejestic” spelled instead of “majesty” for the pronunciation [məˈʤɛsti], we decided not to assume, in the absence of clear evidence, that a listener who typed, for example, “lugsurious” for “luxurious” pronounced as [ˈl∧gʒəriəs] successfully retrieved the speaker's intended word but simply misspelled it. In addition, because the WI task asked listeners to “Please type the English word you think the speaker was trying to say,” making clear that the speaker had (mis)pronounced a real English word, L2 listeners may have assumed that inability to identify the speaker's intended word would signal inadequate English proficiency on their part and therefore wished to save face by attempting to spell something rather than admit they were unable to accurately identify the speaker's intended word by not attempting any spelling at all (All WI responses are summarized in Table 5 and their underlying raw data are available from Richards, 2016, pp. 179–245).

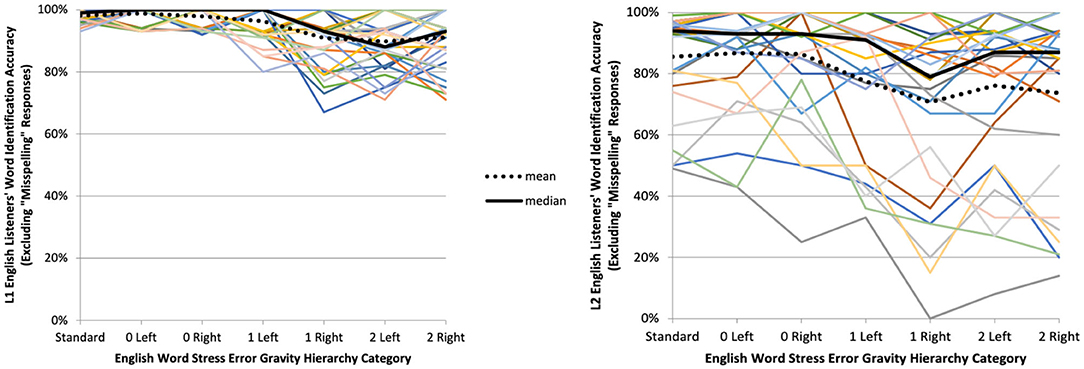

L1 English Listeners' WI Accuracy

We observed deterioration in L1 listeners' WI accuracy, our intelligibility proxy, with the non-standard stress categories furthest from standard stress (Figure 7 left). Within-subjects ANOVA with a Greenhouse-Geisser correction applied to L1 listeners' (typed) WI accuracy data indicates their WI accuracy varied significantly across Hierarchy categories, F(3.59, 132.96) = 18.76, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.34. This large partial η2 effect size shows that 34% of the variance in L1 English listeners' WI accuracy can be attributed to Hierarchy category. It is only at the 1 Right non-standard stress category that L1 listeners began exhibiting significant deterioriation in WI accuracy, either not attempting at all to spell the speaker's intended word or spelling a real English word other than that which the speaker intended.

Figure 7. (Typed) word identification accuracy (excluding misspellings) by Hierarchy category for L1 (n = 38, left) and L2 (n = 31, right) English listeners.

L2 English Listeners' WI Accuracy

Within-subjects ANOVA with a Greenhouse-Geisser correction indicates L2 English listeners' WI accuracy varied significantly across Hierarchy categories, F(4.12, 123.70) = 10.69, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.26. Despite the variability in L2 English listeners' WI accuracy evident in Figure 5 (right), this partial η2 effect size shows that 26% of the variance in their WI accuracy is attributable to Hierarchy category. Like for L1 listeners, the 1 Right non-standard stress Hierarchy category is where the L2 listeners began to exhibit significant deterioration in WI accuracy—though unlike the L1 listeners, this was true for L2 listeners relative only to L2 standard and 0 Left category performance.

L1 vs. L2 English Listeners' Word Identification Accuracy

Both L1 and L2 English listeners experienced the greatest deterioration in intelligibility with the Hierarchy categories farthest from standard stress. However, while the visual similarity in L1 and L2 listeners' WI accuracy data seen in Figure 7 is interesting, it was again impossible to test the significance of this potential difference because of how the L1 vs. L2 listener data strongly violated ANOVA's homogeneity of variance assumption. Although several (i.e., the logit, arcsine square root, and folded square root) transformations were attempted, no transformation succeeded at rendering this study's data homogenous.

Unattempted spellings may be the clearest possible indicator of unintelligibility as they occur only when listeners, despite being assigned no penalty for guessing, were nevertheless unwilling or unable to attempt identifying the speaker's intended word. For both L1 and L2 listeners, the number of unique words (types) and percent of total words (tokens) they declined to identify sharply increases at the 1 Right category (Table 5). However, the L2 listeners experienced substantially reduced intelligibility relative not only to L1 listeners, but even to their own standard stress performance. The L2 listeners therefore were not performing merely from a lower baseline than their L1 listener counterparts, but rather were impacted to an even greater degree (cf., Jenkins, 2000, 2002).

The Hierarchy and Word Stress Error Processing

The aim of the English Word Stress Error Gravity Hierarchy is to provide a means of predicting how listeners are likely to process any given word stress error. Many studies have noted the impact of vowel quality on L1 and L2 English listeners' word stress error processing (Bond and Small, 1983; Cutler and Clifton, 1984; Cutler, 1986; Small et al., 1988; Fear et al., 1995; Cooper et al., 2002; Field, 2005) and that direction of stress shift also impacts listener understanding (Cutler and Clifton, 1984; Field, 2005). This study adds to this research as follows.

In terms of our L1 listeners' LD accuracy data, within-within-subjects ANOVA with a Greenhouse-Geisser correction found a significant interaction between the number of vowel errors and direction of stress shift, F(1.91, 57.4) = 22.21, p < 0.001. Specifically, although both number of vowel errors and direction of stress shift significantly affected L1 listeners' LD accuracy, only the number-of-vowel-errors factor did so across the entire Hierarchy. That is, as in Field (2005), direction of stress shift was a statistically significant factor only where non-standard stress errors were not simultaneously inducing vowel errors.

In terms of L1 listeners' LD RT (with the 24 most sensitive L1 listeners who made 2+ accurate LDs for the 0 Left category), a within-within-subjects ANOVA with a Greenhouse-Geisser correction also found a significant interaction between the number of vowel errors and direction of stress shift, F(1.36, 31.29) = 9.07, p = 0.002. Specifically, the more sensitive L1 English listeners who, at least on occasion, succeeded in making accurate 0 Left “No” LDs significantly slowed from their accurate standard stress “Yes” LDRT baseline to do so, but within the remaining 0 Right – 2 Right Hierarchy categories L1 listeners' accurate “No” LDRTs were statistically equivalent. Interestingly, reverse coding L1 English listeners' 0 Left and 0 Right LDs under the hypothesis that their definition of a “correctly pronounced English word” was, in most cases, broad enough to accommodate non-canonical stress so long as it was instantiated only suprasegmentally. In contrast, for both Hierarchy-defined accurate and inaccurate LDs with the 0 Right stimuli, L1 English listeners' median reaction times were significantly slower relative to their accurate standard stress LDRT.

In terms of L1 listeners' word identification (WI) accuracy, a within-within-subjects ANOVA with a Greenhouse-Geisser correction found a significant interaction between the number of vowel errors and direction of stress shift, F(1.79, 66.22) = 7.23, p = 0.002. L1 English listeners were equally accurate in identifying a speaker's intended word whether that word was pronounced with standard stress or 0 Left, 0 Right or 1 Left non-standard stress. It was only at the 1 Right – 2 Left Hierarchy categories that L1 English listeners exhibited significant deterioration in WI accuracy. Thus, direction of stress shift did affect listeners' WI accuracy, but its impact was not stable across the Hierarchy.

In terms of L2 listeners' LD accuracy, a within-within-subjects ANOVA with a Greenhouse-Geisser correction found a significant interaction between the number of vowel errors and direction of stress shift, F(1.91, 57.4) = 22.21, p < 0.001. As with the L1 listeners, the L2 English listeners' mean LD accuracy was significantly lower for the 0 Left vs. 0 Right non-standard stress pronunciations, but both their 1 Left vs. 1 Right as well as 2 Left vs. 2 Right LD accuracy exhibited no significant difference. As with the L1 listeners, direction of stress shift mattered for the L2 listeners only where non-standard stress errors did not involve vowel errors.

In terms of L2 listeners' LD RT, a within-within-subjects ANOVA with a Greenhouse-Geisser correction found no significant interaction between the number of vowel errors and direction of stress shift, F(1.94, 42.76) = 2.76, p > 0.05. Although only L1 listeners showed a direction-of-stress-shift-modulated effect in terms of accurate LDRT, the L2 listeners did show a direction-of-stress-shift-modulated effect when inaccurately labeling 0 Left vs. 0 Right non-standard stress pronunciations as instantiating a “correctly pronounced English word.”

In terms of L2 listeners' WI accuracy, a within-within-subjects ANOVA with a Greenhouse-Geisser correction found no significant interaction between the number of vowel errors and direction of stress shift, F(1.89, 56.55) = 1.34, p = 0.27. In regard to the respective main effects of these two factors, however, both were significant. Unsurprisingly, number of vowel errors had the greatest impact, F(1.93, 57.96) = 17.88, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.37. Nevertheless, direction of stress shift fell just shy of the 0.14 rule-of-thumb partial η2 effect size boundary separating “medium” vs. “large” effects, F(1, 30) = 4.8, p = 0.04, partial η2 = 0.138. Specifically, L2 listeners (like L1 listeners) were equally accurate in identifying a speaker's intended word whether that word was pronounced with standard stress or 0 Left, 0 Right or 1 Left non-standard stress. It was only at the 1 Right – 2 Left Hierarchy categories that the L2 listeners (like the L1 listeners) exhibited significant deterioration in WI accuracy. In other words, direction of stress shift did affect both listener groups' WI accuracy, but its impact was not stable across the Hierarchy.

In sum, both number of vowel errors and direction of stress shift impacted L1 and L2 English listeners' English word stress error processing. The impact of number of vowel errors and direction of stress shift, however, varied across both Hierarchy categories and dependent variables. The Hierarchy should therefore prove a useful tool for L2 pronunciation teaching and testing, as it provides an easy way of assessing the likely error gravity on any given word stress error.

Discussion

Both L1 and L2 English listeners' word stress error processing largely followed the proposed English Word Stress Error Gravity Hierarchy, with stronger influence from the numbers of vowel changes and weaker influence from the direction of stress shift. As indexed by lexical decision (LD) accuracy, L1 and L2 English listeners frequently struggled to identify as non-standard the mis-stressings containing no vowel errors, even though the experiment instructions explicitly stated they would hear a series of “correctly and incorrectly pronounced English words.” That is, listeners in this study identified non-standard stress largely by the presence or absence of vowel errors, just as has been found to be the case by many previous studies (Bond, 1981, 1999; Bond and Small, 1983; Cutler and Clifton, 1984; Cutler, 1986, 2015; Small et al., 1988; Fear et al., 1995; van Leyden and van Heuven, 1996; Cooper et al., 2002; Field, 2005; Cutler et al., 2007; Zhang and Francis, 2010).

However, the L2 English listeners in this study did not follow L1 listeners' performance merely from a lower baseline. Rather, the further an English word stress error fell from the standard stress Hierarchy category, inducing one or more concomitant vowel errors, the more L2 listeners' auditory LD accuracy was hurt relative to L1 listeners. In addition, in terms of reaction time (RT) for accurate LDs, L1 and L2 English listeners both followed the predicted Hierarchy trajectory—but L2 listeners characteristically required from half a second to a full second longer to search their mental lexicons for the pronunciation they had heard in order to make an accurate LD regarding whether a word spoken in isolation instantiated a “correctly pronounced English word.” Finally, in terms of word identification (WI) accuracy, this study's intelligibility proxy, the L2 listeners again were not working merely from a lower baseline, but rather had higher rates than L1 listeners of unattempted word identification when non-standard stress induced vowel errors.

In other words, even in a non-discourse context, the further a word stress error falls from the English Word Stress Error Gravity Hierarchy's standard stress category, the more likely both L1 and L2 English listeners are to mis-segment the speech string, be led down a garden path forcing additional rounds of mental lexicon lookup, with the result of at least slowed processing (reduced comprehensibility) and perhaps failure to recover the speaker's intended word at all (unintelligibility) (Bond, 1981, 1999; Bond and Small, 1983; Cutler, 2012, 2015; Isaacs and Trofimovich, 2012).

It is true listeners may be able to use context to identify a mispronounced or otherwise unfamiliar word. However, L2 listeners face an uphill battle in taking advantage of context for many reasons. First, the process of acquiring an L1 is the process of becoming highly skilled at attending to the cohort of features most efficiently serving perception and production and becoming equally skilled at suppressing the processing of redundant (or L1-defined “meaningless”) features regarding which attention would waste processing resources. Unfortunately, maximally efficient subconscious strategies for processing the L1 so finely honed in the process of childhood language acquisition frequently have just the opposite effect when applied to an L2, where language features matching those one has learned during L1 acquisition to “tune out” are often those on which attention must be focused if the L2 is to be perceived and processed most efficiently (Cutler et al., 1983, 1986, 1992; Otake et al., 1993, 1996a,b; Cutler and Otake, 1994; Cutler, 1997; Kim et al., 2008). This impacts L2 listeners in that their default misapplication of L1 speech segmentation strategies to the L2 stream of speech characteristically renders slow and sometimes completely unsuccessful the word boundary identification that necessarily precedes mental lexicon lookup that necessarily precedes the context-building required for recovering the meaning of mispronounced words! In addition, context is not always particularly helpful for L2 listeners due to their less robust vocabulary and much stronger tendency than L1 speakers to hear phantom words rather than real words (Broersma and Cutler, 2008). Syntactic complexity and cultural unfamiliarity can further exacerbate L2 listeners' difficulty in identifying mispronounced words from context. These issues are compounded when the input contains multiple unrecognized forms, as less understood context from which the meaning of unknown forms can be inferred can make guessing from context untenably demanding for not only L2 listeners, but also L1 listeners (Schmitt, 2000; Nation, 2001; Folse, 2004; Field, 2008).

In sum, this study has replicated the findings of Cooper et al. (2002) and Cutler et al. (2007) in its investigation of how listeners map non-standard stress pronunciations onto their (presumably) standard stress mental lexicon prototypes. In the current study, both L1 and L2 English listeners from non-tonal L1s largely processed the suprasegmental correlates of English lexical stress merely as phonetic detail, i.e., as allophonic variation. The only correlate of lexical stress that these listeners consistently used to distinguish differences in word stress was not suprasegmental, but segmental. Our phonological understanding of English word stress errors—and our pedagogy—must therefore recognize that the non-canonical use of the suprasegmental correlates of English lexical stress is generally processed as acceptable allophonic variation by both L1 and L2 English listeners. It is only the vowel quality correlate of English lexical stress that is consistently processed categorically. Therefore, the traditional labeling of any non-canonical shift in English word stress as representing an error, regardless of whether the stress shift induces a vowel quality change, is problematic.

Traditionally, any non-canonical shift in English word stress has been treated as an error, without regard to whether the mis-stressing creates a change in vowel quality. However, L1 and L2 English listeners both frequently failed to recognize mis-stressings with no vowel errors as being non-standard. According to the WI accuracy results, neither L1 nor L2 English listeners show any deterioration in intelligibility with 0 Left and 0 Right non-canonical stress pronunciations. Instead, for these advanced L1 and L2 English listeners, non-standard English word stress was largely defined by the presence or absence of vowel errors (cf., Bond and Small, 1983; Cutler and Clifton, 1984; Cutler, 1986; Small et al., 1988; Fear et al., 1995; Cooper et al., 2002; Field, 2005). In the Hierarchy categories farthest from standard stress, word stress errors could and did induce vowel errors that significantly reduced intelligibility (Munro and Derwing, 1995).

Teaching Implications

A motivation for this study was to address the importance of word stress in L2 English learning and teaching. There is evidence that the accurate production of English word stress is crucial for intelligibility and comprehensibility. L1 English listeners use stressed syllables to identify the beginnings of words in speech (Cutler and Norris, 1988; Cutler and Butterfield, 1992), and incorrect word stress can cause listeners to completely misunderstand intended words (Benrabah, 1997; Zielinski, 2008). Incorrect word stress has also been found to lead to loss of comprehensibility (Slowiaczek, 1990; Isaacs and Trofimovich, 2012). Because of the critical role of vowel quality in determining stress, stress errors that change vowel quality result in both L1 and L2 English listeners struggling to identify words being spoken (Field, 2005). Unfortunately, due to the preference of English for alternating stressed and unstressed syllables (Liberman and Prince, 1977), non-standard word stress commonly triggers multiple vowel quality errors because stress exchange causes ordinarily reduced vowels to become clear, while adjacent ordinarily clear vowels become reduced.

Yet it is also the case that word stress errors do not invariably harm intelligibility and comprehensibility (Levis, 2018). For example, word stress minimal pairs such as INsight/inCITE and INsult/inSULT seem not to result in loss of intelligibility. Similarly, when stress errors do not involve changes in vowel quality (e.g., CONcentrate said as concenTRATE), there is no evidence for loss of intelligibility and little evidence for impaired comprehensibility (Slowiaczek, 1990). Field (2005) and this study have demonstrated that L2 English listeners are similarly affected by misplaced word stress but from a lower baseline due to causes such as the continued use of L1 processing strategies inefficient for English, phantom word activation, and a more limited vocabulary.

As a result, teaching English word stress to L2 learners is at the same time both critical and unimportant. Word stress is critical to intelligibility and comprehensibility in words where stress errors result in a change of vowel quality, with the tendency toward multiple changes in vowel quality likely to have greater impact than a single change. But there have also been influential arguments against teaching word stress that must be addressed. In perhaps the most influential, Jenkins (2002) argues that “the placement of word stress…varies considerably across different L1 varieties of English” resulting in “a need for receptive flexibility” (p. 98) but not productive accuracy. Jenkins' argument involves a number of implicit, problematic claims. First, Jenkins (2000), Jenkins (2002) says that word stress patterns vary considerably, which in light of findings about the importance of word stress for L1 English listeners would suggest there is marginal mutual intelligibility across varieties of English. This is clearly not the case. Berg (1999) says that about 1.7% of multisyllabic words have different stress patterns between AmE and BrE, for a total of about 930 words. Teachers should be aware of these differences, but having over 98% of words stressed similarly represents enormous agreement across varieties.

Second, Jenkins (2000), Jenkins (2002) implies that if L1 speakers of English vary considerably yet understand each other, L2 speakers will also be understood despite variations in word stress patterns. However, McCrocklin (2012) argues that “word stress affects a number of other important features, such as vowel quality and length… These features are listed as core features in Jenkins' proposal and were thus shown within her data to impact intelligibility” (p. 252). Thus, Jenkins' conclusion that word stress “rarely causes intelligibility problems…and where it does so, always occurs in combination with another phonological error” in fact does not imply word stress rarely causes intelligibility problems, but rather that since vowels (as well as other aspects of Jenkins' proposed Lingua Franca Core) are strongly contingent on accurate word stress, English word stress is critical for the intelligibility of L2 speech by L2 listeners (Deterding, 2013; Lewis and Deterding, 2018).

Jenkins (2000, p. 39) is right in saying that comprehensive analysis of all possible English word stress rules and their exceptions is “far too complex for mental storage by students and teachers alike.” However, it is not necessary to teach the full system since a relatively small number of word stress rules cover most academic English vocabulary (Murphy and Kandil, 2004; McCrocklin, 2012; Richards, 2016). As a result, materials developers and teachers of need to know specific underlying word stress patterns which facilitate perception and production of standard English word stress patterns for known and novel words (Nation, 2001; Aitchison, 2012; Cutler, 2012). If these word stress regularities are learned, only the small number of relevant exceptions need to be learned individually—a much more manageable task. Strategies such as condensing L2 learners' exposure to the similar-sounding words from which L1 listeners have acquired their implicit knowledge of English word stress patterns via rhyme-based (e.g., “-tion,” “-ssion” and “-cian”) pattern “flooding” (see Richards, 2016, p. 257ff.) are particularly recommended for helping produce stream-of-speech automaticity. Key academic word list words such as ANalyze, aNAlysis, and anaLYtical carry a high semantic load in academic and professional communication. Unfortunately, these are precisely the type of words that are most likely to result in vowel changes when they are mis-stressed, resulting in slowed understanding at best and loss of understanding at worst. Whether the speaker is a graduate student, business executive, healthcare worker, or one of many others whose job depends on clear communication, accurate stress of essential vocabulary can make speech more intelligible, especially when the words are longer than two syllables.

Limitations and Future Directions

This study, in order to examine the effects of word stress errors across the Hierarchy, admittedly used a task that is unlikely to show up in normal communication. As such, it is uncertain how well the results reflect how listeners respond to word stress errors in communicative contexts. The study also is limited in its use of L2 listeners. Although there were enough L2 listeners to statistically test the research questions, the listeners came from a wide variety of L1 backgrounds, and as a result, it is unclear whether the wide variation in L2 scores came from variations in the L1s of the listeners or other unexplored factors.

The study raises questions about how intelligibility and comprehensibility would be affected in more authentic communicative contexts. Our results especially showed that greater numbers of vowel changes led to less efficient understanding and processing by both L1 and L2 listeners. This suggests a correlation between spoken test scores and word stress accuracy, and examinations of spoken language test scores for populations such as international teaching assistants, who frequently use words from the academic wordlist (Coxhead, 2000) may show that types of word stress errors correlate with test scores. Additionally, we assumed that typical word stress errors happened due to analogy with other related words (Guion et al., 2003), but it would be helpful to have better data on the patterns of word stress errors that occur in real speech. A corpus of L2 speech that elicited varied multi-syllabic words would be useful in identifying the extent to which such analogical errors occur.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Institutional Review Board, Iowa State University. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

This article is based on the dissertation research of MG. As such, her work forms the foundation of the research. JL is her dissertation supervisor. In this paper, he contributed most heavily to reformulating the introduction, literature review, discussion, and teaching implications. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The handling editor declared a past co-authorship with one of the authors JL.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcomm.2021.628780/full#supplementary-material

References

Aitchison, J. (2012). Words in the Mind: An Introduction to the Mental Lexicon, 4th ed. Malden, MA: John Wiley & Sons.

Anderson-Hsieh, J., Johnson, R., and Koehler, K. (1992). The relationship between native speaker judgments of nonnative pronunciation and deviance in segmentals, prosody, and syllable structure. Lang. Learn. 42, 529–555. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-1770.1992.tb01043.x

Balota, D. A., Yap, M. J., Hutchison, K. A., Cortese, M. J., Kessler, B., Loftis, B., et al. (2007). The English lexicon project. Behav. Res. Methods 39, 445–459. doi: 10.3758/BF03193014

Barca, L., Burani, C., and Arduino, L. S. (2002). Word naming times and psycholinguistic norms for Italian nouns. Behav. Res. Methods Instrum. Comput. 34, 424–434. doi: 10.3758/BF03195471

Benrabah, M. (1997). Word stress - a source of unintelligibility in English. IRAL Int. Rev. Appl. Linguis. Lang. Teach. 35:157. doi: 10.1515/iral.1997.35.3.157

Berg, T. (1999). Stress variation in British and American English. World Englishes 18, 123–143. doi: 10.1111/1467-971X.00128

Bond, Z. S. (1981). Listening to elliptic speech: pay attention to stressed vowels. J. Phon. 9, 89–96. doi: 10.1016/S0095-4470(19)30929-5

Bond, Z. S. (1999). Slips of the Ear: Errors in the Perception of Casual Conversation, 1st Edn. San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Bond, Z. S., and Small, L. H. (1983). Voicing, vowel, and stress mispronunciations in continuous speech. Percept. Psychophys. 34, 470–474. doi: 10.3758/BF03203063

Broersma, M., and Cutler, A. (2008). Phantom word activation in L2. System 36, 22–34. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2007.11.003

Brysbaert, M., New, B., and Keuleers, E. (2012). Adding part-of-speech information to the SUBTLEX-US word frequencies. Behav. Res. Methods 44, 991–997. doi: 10.3758/s13428-012-0190-4

Brysbaert, M., Warriner, A. B., and Kuperman, V. (2014). Concreteness ratings for 40,000 generally known English word lemmas. Behav. Res. Methods 46, 904–911. doi: 10.3758/s13428-013-0403-5

Cambridge University Press (2015). Cambridge Dictionaries Online. Available online at: http://dictionary.cambridge.org/us/ (accessed March, 2016).

Celce-Murcia, M., Brinton, D., and Goodwin, J. M. (2010). Teaching Pronunciation: A Course Book and Reference Guide. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Coltheart, M., Rastle, K., Perry, C., Langdon, R., and Ziegler, J. (2001). DRC: a dual route cascaded model of visual word recognition and reading aloud. Psychol. Rev. 108, 204–256. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.108.1.204

Cooper, N., Cutler, A., and Wales, R. (2002). Constraints of lexical stress on lexical access in English: evidence from native and non-native listeners. Lang. Speech 45, 207–228. doi: 10.1177/00238309020450030101

Cutler, A. (1986). Forbear is a homophone: lexical prosody does not constrain lexical access. Lang. Speech 29, 201–220. doi: 10.1177/002383098602900302

Cutler, A. (1997). The syllable's role in the segmentation of stress languages. Lang. Cogn. Process. 12, 839–846. doi: 10.1080/016909697386718

Cutler, A. (2012). Native Listening: Language Experience and the Recognition of Spoken Words. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Cutler, A. (2015). “Lexical stress in English pronunciation,” in: The Handbook of English Pronunciation, eds M. Reed and J. M. Levis (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc), 106–124. Available online at: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/9781118346952.ch6/summary

Cutler, A., and Butterfield, S. (1992). Rhythmic cues to speech segmentation: evidence from juncture misperception. J. Memory Lang. 31, 218–236. doi: 10.1016/0749-596X(92)90012-M

Cutler, A., and Carter, D. M. (1987). The predominance of strong initial syllables in the English vocabulary. Comput. Speech Lang. 2, 133–142. doi: 10.1016/0885-2308(87)90004-0

Cutler, A., and Clifton, C. E. (1984). “The use of prosodic information in word recognition,” in Attention and Performance X: Control of Language Processes, eds H. Bouma and D. G. Bouwhuis (London: Lawrence Erlbaum), 183–196.

Cutler, A., Mehler, J., Norris, D., and Segui, J. (1983). A language-specific comprehension strategy. Nature 304, 159–160. doi: 10.1038/304159a0

Cutler, A., Mehler, J., Norris, D., and Segui, J. (1986). The syllable's differing role in the segmentation of French and English. J. Memory Lang. 25, 385–400. doi: 10.1016/0749-596X(86)90033-1

Cutler, A., Mehler, J., Norris, D., and Segui, J. (1992). The monolingual nature of speech segmentation by bilinguals. Cogn. Psychol. 24, 381–410. doi: 10.1016/0010-0285(92)90012-Q

Cutler, A., and Norris, D. (1988). The role of strong syllables in segmentation for lexical access. J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform. 14, 113–121. doi: 10.1037/0096-1523.14.1.113

Cutler, A., and Otake, T. (1994). Mora or phoneme? Further evidence for language-specific listening. J. Memory Lang. 33, 824–844. doi: 10.1006/jmla.1994.1039

Cutler, A., Wales, R., Cooper, N., and Janssen, J. (2007). “Dutch listeners' use of suprasegmental cues to English stress,” in: Proceedings of the 16th International Congress of Phonetics Sciences (ICPhS 2007), eds J. Trouvain and W. J. Barry (Dudweiler: Pirrot), 1913–1916.

Dalton, C., and Seidlhofer, B. (1994). “Is pronunciation teaching desirable? Is it feasible?,” in: Proceedings of the 4th International NELLE Conference, ed T. S. Sebbage (Hamburg, Germany: NELLE), 14–15.

Dauer, R. M. (2005). The lingua franca core: a new model for pronunciation instruction? TESOL Q. 39, 543–550. doi: 10.2307/3588494

Dechert, H. W. (1984). “Individual variation in speech,” in: Second Language Productions, eds H. W. Dechert, D. Möhle, and M. Raupach (Tübingen, Germany: Gunter Narr Verlag), 156–185.

Deterding, D. (2013). Misunderstandings in English as a Lingua Franca: An Analysis of ELF Interactions in South-East Asia, Vol. 1. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

Dickerson, W. B. (1989). Stress in the Speech Stream: The Rhythm of Spoken English. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Dupoux, E., Sebastián-Gallés, N., Navarrete, E., and Peperkamp, S. (2008). Persistent stress ‘deafness': the case of French learners of Spanish. Cognition 106, 682–706. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2007.04.001

Fear, B. D., Cutler, A., and Butterfield, S. (1995). The strong/weak syllable distinction in English. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 97:1893. doi: 10.1121/1.412063

Field, J. (2005). Intelligibility and the listener: the role of lexical stress. TESOL Q. 39, 399–423. doi: 10.2307/3588487

Field, J. (2008). Revising segmentation hypotheses in first and second language listening. System 36, 35–51. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2007.10.003

Folse, K. S. (2004). Vocabulary Myths: Applying Second Language Research to Classroom Teaching. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

Guion, S. G. (2005). Knowledge of English word stress patterns in early and late Korean-English bilinguals. Stud. Second Lang. Acquis. 27, 503–533. doi: 10.1017/S0272263105050230

Guion, S. G., Clark, J. J., Harada, T., and Wayland, R. P. (2003). Factors affecting stress placement for English nonwords include syllabic structure, lexical class, and stress patterns of phonologically similar words. Lang. Speech 46, 403–426. doi: 10.1177/00238309030460040301