- University of British Columbia, Department of English Language and Literatures, Vancouver, BC, Canada

This paper proposes a renewed and more textured understanding of the relation between deixis and direct discourse, grounded in a broader range of genres and reflecting contemporary multimodal usage. I re-consider the phenomena covered by the concept of deixis in connection to the speech situation, and, by extension, to the category of Direct Discourse, in its various functions. I propose an understanding of Direct Discourse as a construction which is a correlate of Deictic Ground. Relying on Mental Spaces Theory and the apparatus it makes available for a close analysis of viewpoint networks, I analyze examples from a range of discourse genres - textual, visual and multimodal, such as literature, political campaigns, internet memes and storefront signs. These discourse contexts use Direct Discourse Constructions but usually lack a fully profiled Deictic Ground. I propose that in such cases the Deictic Ground is not a pre-existing conceptual structure, but rather is set up ad hoc to construe non-standard uses of Direct Discourse–I refer to such construals as Fictive Deictic Grounds. In that context, I propose a re-consideration of the concept of Direct Discourse, to explain its tight correlation with the concept of deixis. I also argue for a treatment of Deictic Ground as a composite structure, which may not be fully profiled in each case, while participating in the construction of viewpoint configurations.

Introduction

This paper argues for the need to recognize the concept of Fictive Deictic Ground, to account for the uses of discourse in communicative contexts other than natural spoken conversation. In a standard situation, the deictic center is the contextually determined pre-condition for spoken communication–the speaker and the hearer need to share deictic space and time in order to engage in a conversation. The original formulation (Bühler, 1990 [1934/1984]) further uses the shared deictic context as an explanation of the meaning of expressions such as I, here, or now–the referents of these are determined deictically, in contrast to anaphoric usage. Importantly, Bühler’s approach does not automatically represent the Hearer you, or the resulting view of Deictic Ground as the site of conversational discourse. Research on deictic expressions has added a number of theoretical and cross-linguistic observations (e.g., Levinson, 2008; Fillmore, 1997; Fillmore, 1982) and deixis has remained one of the core concepts in pragmatics. Recent work, however, has expanded the scope of the enquiry–adding the discussion of joint attention (Tomasello, 1995; see also Turner et al., 2019 for a discussion of Blended Classic Joint Attention–in the context of TV, film, etc.), and numerous studies of gesture and eye gaze (e.g., Stukenbrock, 2014; Stukenbrock, 2020), as ways in which the speaker and the hearer use their bodies to make joint attention and communication possible1. Also, deixis is often talked about in terms of ‘grounding’, or Deictic Ground (Langacker, 1987; Langacker, 1991; Hanks, 1990; Brisard, 2012), to account for the numerous ways in which the use of deixis goes beyond just ‘being there’ for communication to happen, but rather being actively used to construe situations. I will follow Hanks in this respect and use the term Deictic Ground as a flexible construct relied on by communicators, and, as Cornish (2011) observes, also used to set up the subjective viewpoint or perspective which allows the discourse to be construed in a specific way. In what follows I introduce the concept of Fictive Deixis, to account for the cases where basic elements of deixis are missing or re-construed. To explain the phenomenon, I connect the general understanding of Deictic Ground to the use of constructional forms of spoken discourse.

The relation between Deictic Ground and spoken communication receives varied amounts of attention in various approaches. Scholars closer to Bühler follow him in the focus on ‘pointing’, which includes more work on gesture, eye gaze, and other embodied means of achieving joint attention. The focus on deixis-as-‘pointing’ is also clear in the rich literature on demonstratives (which includes a very recent Research Topic in Frontiers in Psychology [2020, Vol 11 https://www.frontiersin.org/research-topics/10557/demonstratives-deictic-pointing-and-the-conceptualization-of-space]). Much less attention (except the work by Fillmore (1997) and Fillmore (1982)) is given to the fact that deixis is at least partly defined by the inclusion of the speaker I and the hearer you and relies on discourse in complex ways. In this paper, I focus on the understanding of deixis as a ‘speech situation’, and I propose that it should further be considered in connection to the cluster of constructions known as Direct Discourse, which share the grammar of spoken communication, but appear in contexts other than natural discourse–such as narrative discourse. The role of deixis in the choices of grammatical forms of Speech and Thought Representation in narratives has been given much attention–especially in work by Duchan et al. (1995), Sanders and Redeker (1996)Vandelanotte (2004) and Vandelanotte (2009). In what follows, I will also look at examples from narratives, but only to the degree that they illustrate questions about the connection between deixis and spoken discourse.

In considering various contexts in which discourse is used against a non-typical Deictic Ground, this paper may evoke the concept of Deixis am Phantasma, as introduced by Bühler 1990 [1934/1984] and discussed from the semiotic perspective in West (2013). However, there is in fact little in common between Bühler’s work and the argument presented here. Bühler foundational theory 1990 [1934/1984] is focused on pointing, such that the object pointed at may be displaced from the current place and time (being imagined, recalled from memory or a dream). The situations pointed at may have never materialized but may nevertheless be felt as vividly experienced mental images. In this paper, however, I focus on cases of deictic construals which do not rely on pointing, but on spoken discourse instead, and which evoke and construct a Fictive Deictic Ground to legitimize discourse rather than structure imaginary experience. In other words, I focus on the ways in which the concept of Deictic Ground participates in our understanding of Direct Discourse (outside of colloquial spoken contexts) and on the mutual dependence of Direct Discourse and Deictic Ground. The examples to be discussed below represent a number of communicative situations evoking new Deictic Grounds, rather than relying on existing ones.

In the remainder of the Introduction, I outline two of the theoretical concepts I will use: Viewpoint and Mental Spaces Theory (MST). In Direct Discourse Construction and the Deictic Ground, I further develop the approach to Direct Discourse; The Use of Direct Discourse Construction in Literary Genres discusses examples from literary texts, while Multimodal Artifacts focuses on internet memes and storefront signs. Discourse Viewpoint and Final Comments sections conclude the discussion.

The understanding of viewpoint in this study builds on several broad assumptions, which I summarize here. All these aspects of perspective-taking have been discussed, in application to various discourse types, in several collections of studies (Dancygier and Sweetser, 2012; Dancygier, Lu and Verhagen, 2016; Dancygier and Vandelanotte, 2017b; Vandelanotte and Dancygier 2017).

Viewpoint (or perspective) is here understood as a mental alignment expressed by a discourse participant, through one or (quite often) more of the following devices: the choice of a linguistic expression, a visual artifact, performance of a sound sequence (such as a tune or intonation pattern), gesture (hand gesture, shrug, eye-brow movement etc.), eye gaze, body posture, or mime. The alignment can focus on the experiential aspects of the basic scene assumed to be the locus of the exchange: location (direction of motion, or distance), what can be seen or heard from the location assumed, the relationship between the speaker and other participants, or the action currently being performed. In more complex instances a participant can align with a temporal perspective, an emotional angle, a humorous or ironic attitude, and an epistemic or evaluative stance. One of the most common themes in viewpoint research is an analysis of types of viewpoints (e.g., visual, enactive, epistemic or emotional) adopted by participants in an event which is narrated, rather than experienced firsthand. I will assume, though, that the difference between viewpoint expression in spontaneous conversation and in fictional narratives is due to the nature of the linguistic material, rather than to the nature of viewpoint as such.

It is typical of most artifacts that they rely on multiple viewpoints–multiplicity is the norm, not an exception (see Dancygier and Vandelanotte, 2016). But the many viewpoint construals available in any scene are not a loose collection–they form a viewpoint configuration (Dancygier, 2012; Dancygier, 2017; Dancygier and Vandelanotte, 2016; Dancygier and Vandelanotte, 2017a). Even the simplest of expressions imply a viewpoint configuration, rather than a single perspective of a single participant (though one aspect of the viewpoint structure may be more prominent). For example, a speaker describing their location in a room (as in I am sitting at my desk) is making available a range of embodied and visual viewpoint parameters. Deictic parameters (time, location, the first-person speaker I) participate in that viewpoint configuration, but they are not the only aspects of the viewpoint network. Just to give a few examples, the sentence further suggests the speaker’s ability to reach objects on the desk, but not objects which the desk separates them from, their visual and enactive perspective such that they can see and interact with someone sitting across from them at the other side of the desk, that they can see the scene in front of them, but not behind them, etc.

If we change the tense (a grammaticalized deictic category), as in I was sitting at my desk, the sentence adds another layer of viewpoint to include the utterance about the past in the scope of the viewpoint parameters of the current speaker and their speech situation. The highest viewpoint level would further depend on the role the sentence plays in the discourse overall. If the speaker of the sentence is telling a story to an addressee, using distal forms (So I was sitting at my desk when I heard the news), the deictic viewpoint of the storyteller and the storylistener is higher than the experiential viewpoint of the participant depicted at the desk, hearing the news. But if the storyteller chooses proximal deixis (this as a discourse deictic, and proximal forms throughout) to tell the story (So this is the story. I am sitting at my desk, and my radio is on. . .), they bring the past scene and events up to the current deictic viewpoint of the story being told. At the most basic level, then, the Deictic Ground, with its participants (speaker and hearer), location (here) and time (now) provides the most rudimentary viewpoint configuration (Fillmore 1997; Fillmore, 1982). Deictic Ground is the site of a conversational exchange, in which the participants alternate taking the deictic role of speaker (I) and hearer (you), in the here and now. The interlocutors’ shared understanding of what is or is not accessible is reflected in the use of proximal or distal indexical expressions such as this/that (Diessel, 2006; Dancygier, 2019).

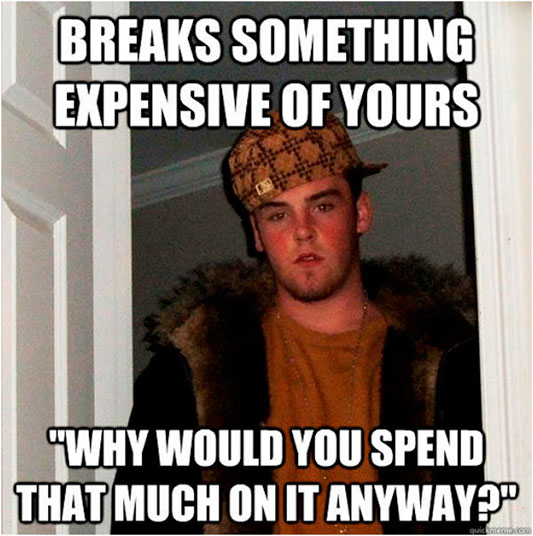

In accounting for the multiplicity of viewpoint I rely on the theory of Mental Spaces–conceptual packets representing situations (real, remembered, imaginary, desired, etc.), established and manipulated as discourse progresses; 2 the start point of the network of spaces is the base space–which includes the actual Deictic Ground of an event or an exchange. While Mental Spaces Theory has proven to be especially useful in analyzing reference, it also provides a clear set of tools to describe viewpoint constructions (expressions of emotional and epistemic stance, construal of conditional and imagined situations, etc (cf. Fauconnier, 1994; Fauconnier, 1997; Fauconnier and Sweetser, 1996; Sanders and Redeker, 1996; Dancygier and Sweetser, 2005). To remain within the scope of my simplistic past tense example above (I was sitting at my desk), the Deictic Ground of the sentence requires that we assume the presence of a speaker, informing the listener about the prior-to-now event, taking place in a not-here room where the speaker’s desk is located, and describing the speaker seated at the desk (then, not now). There are thus two mental spaces profiled–the base space when the sentence is uttered, and the Past space when the speaker sat at their desk for some time. At the same time, the base space (and its current Deictic Ground) provides a Viewpoint space, while the Past space is the Focus space. This is to say that the past situation and its Deictic Ground (as in the ‘desk’ example) is typically viewed as distal, from the perspective of the present communicative situation (and its Deictic Ground). The two spaces thus form a configuration, where the base space (now) is higher in the network than the Past space (then) discussed. As I have also shown, a speaker might shift away from the Ground correlated with the moment of speech and adopt the past situation as the current proximal Ground–that is, say something like So this is the story. I am sitting at my desk,. . .. Such configurations are unremarkable but exemplify a structure which makes switching the Ground to a different space possible and thus can yield new viewpoint effects. The mental space configurations of viewpoint networks in the three ‘desk’ cases (present, past, and present-as-past) are represented in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1. (A) I am sitting at my desk. (B) I was sitting at my desk. (C) So this is the story. I am sitting at my desk, …

Direct Discourse Construction and the Deictic Ground

Typically, the category of Direct Discourse (DD) applies to extended narratives, where what characters say or think can be represented in three different ways: as Direct Discourse (a not-necessarily-genuine quotation), as Indirect Discourse (reported by the narrator or another character), or as Free Indirect Discourse (which is more faithful to the assumed discourse of the character, but still adjusts grammatical forms such as tense and personal pronouns to the higher viewpoint from which discourse is being reported). DD is understood in terms of the default Deictic Ground and uses appropriate proximal forms. There is no Direct Discourse without an assumed Deictic Ground, and the Deictic Ground is a prerequisite for Direct Discourse. This correlation is used below to argue that the use of Direct Discourse cannot be separated from the Deictic Ground forming the base of a network of mental spaces. Using the form of Direct Discourse assumes a viewpoint structure such that there is (at a minimum) a base mental space determining the discourse participants, time, and location. I will refer to such a mental space as Direct Discourse Ground (DDG). It combines deictic elements (I, you, here, now) with other communicative affordances, which include the use of spoken language first of all, but also using one’s body to gesture, regulate joint attention with eye-gaze, etc. Importantly, a DDG can be embedded in higher DDGs (e.g., in a fictional narrative structure), and have lower level DDGs (other conversations or events reported during the base conversation) embedded in it. The viewpoint of each DDG contributes to the viewpoint network of a broader discourse structure (narrative, conversational, etc.). The need for such a multilevel understanding of discourse is further clarified by work on sign language (cf. Dudis, 2004, on body partitioning, Janzen, 2004 on ASL).

Direct Discourse Construction

In the context of Direct Discourse Ground, actual forms of DD are unique in that they are unrestricted constructionally–all that is required is the use of quotation marks, to signal the switch from the mental space currently being developed to a lower-level conversation space within it. In comparison, Indirect Discourse (ID) and Free Indirect Discourse (FID) both have formal constructional features which restrict the choice of forms (e.g., the embedded clause in Indirect Discourse undergoes a tense, pronoun and adverb shift, going, for example, from the assumed I will finish the paper tomorrow to indirect She said she would finish the paper the next day). However, in spite of its openness, Direct Discourse should also be treated as a construction. Vandelanotte (2004) shows convincingly that in spite of the use of forms correlated with the selected Deictic Ground, such choices in the narrative constitute a constructionally determined shift away from the Deictic Ground of the narrative flow as a whole. Besides, the three reporting forms (DD, ID and FID) together constitute a constructional cluster, where formal choices signal deictic concepts such as speakerhood in construction-appropriate ways (see Sanders and Redeker, 1996; Vandelanotte, 2009). I will therefore refer here to Direct Discourse Construction (DDC) and its various uses.

Every narrative sets up a number of mental spaces (more specifically, narrative spaces, cf. Dancygier, 2012). These spaces are inhabited by participants (characters) and occasionally represent conversations between these participants. When such a conversation becomes a part of what the narrative constructs, the two most likely options are Direct Discourse Construction (DDC), which shifts the viewpoint to the Deictic Ground of the scene in which the conversation occurs, and Indirect Discourse Construction (IDC), which embeds the conversational Ground in the higher narrative space. For example, if one character says to another I have to go now, the DDC representation would be “I have to go now”, she said, while the IDC would be rendered as She said she had to go right away, where the expression she said is part of the narrative flow in the third person past tense narrative, and also the Viewpoint space from which the actual words of the character are represented. The constructional shift from DDC to IDC (which moves the DDC space into an embedded status with respect to the IDC she said-space) is marked by changing the forms appropriate to the proximal Deictic Ground (I, Present Tense, now) into distal forms of the embedded Ground (she, Past Tense, right away). Additionally, the deictic verb go suggests that the speaker and the listener share the current location (here), but there is no such assumption of participant proximity in the IDC version, since the speaker/narrator using the she said form is aligned with her/his own Ground, in the higher (Viewpoint) space in which the reported situation (Focus space) is embedded3.

In the default set-up, DDC is used in correlation with the Deictic Ground in which the conversation happens (and thus forms a DDG). However, speakers may choose a different Deictic Ground as the backdrop to at least some parts of the conversation. Rubba (1996) describes how speakers may use proximal deictic words such as here to refer to a community they mentally align with, rather than to the current location. Rubba refers to such distal Ground which is talked about as if it were proximal as ‘Alternate Ground’. What is important about such alternate Grounds is that deictic terms may be used to align the speaker with mentally salient spaces, and not necessarily with immediately accessible spatial and temporal spaces; spaces evoked in this manner are not imaginary and can be ‘pointed at’ or marked as proximal. This is made possible by embedding the spatially distal space in the current DDG, and assuming a proximal viewpoint in rendering it. Such distal-to-proximal shifts are driven strictly by viewpoint shifts and alter the overall viewpoint network being elaborated. Somewhat similar use of deictic forms has been described by Hanks (1990). As the examples throughout this paper suggest, DDGs are subject to various viewpoint shifts and embeddings and there is a wide range of such cases, in creative contexts, but also in various ordinary situations.

The point I argue for in the remainder of this paper is that DDC should not be seen solely in terms of typical sentences, spoken against the background of a Deictic Ground. Instead, we should consider how DDC emerges in various discourse contexts, how it fits into the viewpoint network of the discourse, and how its basic deictic parameters participate in the interaction. One of the assumptions guiding the analysis is that the distinction between ‘real’ and ‘imaginary’ deixis does not allow us to interpret discourse with sufficient granularity. Tying up deixis with DDC (to focus on DDGs instead of separating deixis from direct speech) gives us an opportunity to go beyond sentential and/or gestural elements and understand the mechanisms and processes involved in the construction of non-typical uses of discourse and to interpret viewpoint networks with more accuracy. Below, I consider two types of examples where DDC is used in ways deviating from standard conversational DDGs: literary discourse and multimodal artifacts. Before discussing the two communicative genres, I will briefly review the approaches to the use of DDC as an other-than-literal correlate of a fully determined Deictic Ground.

What does Direct Discourse Construction do

Many examples suggest that not every use of the Direct Discourse Construction is correlated with a fully profiled Deictic Ground. Also, while in most contexts the Deictic Ground is what makes Direct Discourse possible (as a result of the speaker and hearer roles being profiled), there are cases (which I discuss below) where Direct Discourse is used so that a Deictic Ground can emerge, also when crucial aspects of a default Deictic Ground are missing. Such instances confirm that the correlation between DD and DG creates various discourse affordances.

There has been some discussion of how an utterance structured as DDC can be used to signal meanings other than the default representation of speech in a Deictic Ground (Clark and Gerrig 1990; Pascual, 2006; Pascual, 2014; Pascual and Sandler 2016). The shared focus of these analyses are examples of sentences which are structured as DDC, while remaining independent of the Deictic Ground of the surrounding discourse. Examples come from written and spoken discourse.

In a written text, Direct Discourse is often represented in quotation marks (or can be seen as a quotation even if the markers of a shift to DDC are missing)–the separate Deictic Ground is thus signaled through a written convention; in spoken discourse speakers may mark the quotation with a gesture representing the scare quotes. Thus, in their genuine use, quotation marks (in writing or in gesture) represent a switch into and out of the DDG that the current speaker (or narrator) presents as not aligned with the default Ground of current discourse. This is, however, not as clear as it seems. In spoken context, if the speaker interrupts the flow of discourse to signal a switch to a different DDG, by gesture, a pause, or change of tone of voice (see Clark, 2016 for a full overview of such usage), the discourse included inside the quoted fragment signals that the speaker says something from a perspective other than their own. In fiction, something similar happens, as the narrator yields the Ground to a character or characters in conversation. Overall, quotation status consistently marks a shift to a different level of discourse, with the overarching discourse viewpoint allowing for a consistent structuring of viewpoints, depending on the genre.

Importantly, the reasons why a string of discourse is placed in quotation marks may not be restricted to a simple embedding of a piece of discourse which faithfully (verbatim) represents what was actually said in the situation described. In their now classic article, Clark and Gerrig (1990) argue that quotations do not represent authentic discourse, but that they serve as demonstrations. They claim that “The prototypical quotation is a demonstration of what a person did in saying something” (1990:769). Quotations are thus thought to demonstrate an act, rather than represent speech. This approach was further extended to a broader theory of depictions in Clark (2016)–the general point being that many communicative forms (such as gesture, vocal imitation, etc.) do not ‘describe’ anything, but rather ‘demonstrate’ or ‘depict’. What is particularly important in the ‘depiction’ approach is its broad scope, but also its assumption of a special status of ‘quotations’–which we can assume refers to specifically marked uses of DDC. The issue of ‘faithfulness’ of DDC was also taken up in Short et al. (2002). They argue that rejecting any ‘faithful’ value of DDC (which is Clark and Gerrig’s point) is an overstatement and suggest that faithfulness should be textured in order to refer to various types of discourse.

Furthermore, Direct Discourse has been approached recently from the perspective of its possible fictive nature (Pascual 2006; Pascual, 2014; Pascual and Sandler 2016). The approach assumed in the ‘fictive interaction’ work points to a broad range of uses, such as the fictive use of verbs of communication (as in What does that tell you? Her behavior speaks for itself) as well as textual insertion of discourse snippets (“Any questions? Call us”, “the attitude of yes, I can do it”). Overall, the suggestion is that we naturally conceptualize attitudes or experience in dialogic terms. The ‘fictive’ aspect of such expressions is that even though they rely on verbs of communication or are represented as unattached discourse fragments, no actual conversation is implied to have taken place. The semantic mechanism whereby spoken discourse demonstrates or represents attitudes and emotional responses requires clarification–in what follows, I will refer to such cases as examples of metonymy. Importantly, the fictive utterances inserted in discourse do not lose their grammatical structure and are inserted without adjustments. Also, while expressions such as yes, I can do it are used metonymically to represent attitudes, they do not fit the understanding of being ‘imaginary’. They are not immersed in any unreal DDG and do not require being seen in terms of DDC. The DG parameters are simply not profiled at all.

The approaches briefly mentioned here are relevant to my examples, in that they show DDC forms used beyond ‘faithful’ representation of discourse connected to a Deictic Ground. DDC does not have any formal correlates of being embedded in discourse in ways that would support its interpretation–even when it is syntactically or morphologically embedded, as in many examples Pascual mentions (2006, 2014). This provides the grounds for the communicative effect of pretend-quotations being metonymic tokens of specific types of speech acts or communicative acts (so a phrase such as Yes, I can do it stands for a positive and determined attitude to a challenging task). Such uses do not rely on any fully profiled DDG and evoke instead any and all DDGs where such an expression of an attitude would be appropriate.

Importantly, a similar effect can be achieved in a more structured deictic context. When Barack Obama was running for President in 2008, his primary slogan was Yes we can!–used in campaign materials and also repeated in his speeches. The form of the slogan evokes a spoken exchange in which someone may doubt whether true change is possible (something like Can we? (achieve what we want)). Obama’s use of we includes his followers in the attitude, while the phrase as a whole is a (non-fictive!) response to a fictive question suggesting ‘doubt’. The answer comes from a specific subjectivity–the candidate himself, and so at least the speaker role in this Deictic Ground is filled–while the Yes I can do it generic attitude in Pascual’s examples does not profile anyone in particular as the speaker.

What appears to be the case, then, is that the categories of ‘demonstration’ and ‘fictive interaction’ both rely on shorter or longer strings of DDC which tacitly evoke a Deictic Ground or a full DDG. However, the Ground may fill only some of the four deictic roles (speaker, hearer, time, and place). The more roles are filled, the closer the expression is to a genuine use of DDG and DDC, in a recognizable communicative context. But the fewer roles are filled, the smaller the possibility of a genuine use of DDC and the stronger the indication of metonymic evocation. What specifically is evoked depends on the type of expression, its emotional load, and the discourse context. Some aspects of these types of uses of DDC are thus worthy of note. First, the form of DDC may appear without a properly construed DG. There are various degrees of how much of DG remains unprofiled; as an extreme case, the phrase the attitude of yes, I can do it does not profile any of the usual deictic parameters, relying instead on the metonymic emotional value of the phrase. And yet, the emotional viewpoint expressed via the form used is easily interpretable because, as listeners, we create a set of possible DGs and contexts where the generic DDC yes, I can do it would signal the viewpoint intended. The DDGs evoked are not imaginary in any sense. Rather, they make it possible for the phrase to ‘demonstrate’ the attitude in question.

The two very similar expressions (Yes, we can! and the attitude of Yes, I can do it!) prompt viewpoint networks of different nature and complexity. Obama’s slogan is licensed by a generic DDG, wherein he addresses voters to prompt the shared viewpoint of ‘determination’. The second example establishes a pattern that I will elaborate on in the remainder of this paper: an instance of DDC which is not aligned with any DG and thus needs to set up a Fictive DG, where there is a speaker using a phrase that metonymically evokes an attitude.

This is still different from inserting the sentence into an IDC (She was determined that she could do it) where the embedding of the DDC space in the higher narrative space binds all the Deictic Ground elements to a higher narrative space which inherits deictic material from a still higher narrative space. The viewpoint of the higher space precludes reading the lower space as purely metonymic and not ‘faithfully’ representing the discourse. What this suggests is that the issue of ‘faithfulness’ of quotations may not be a matter of the type of text (as Short et al., 2002 suggest), but rather should be seen in the context of the viewpoint and deictic structure provided by a higher space. In other words, the narrator can be ‘trusted’ to report what ‘she said’, so the assumption of faithfulness is easier to accept. But in DDC, there is no such assumption of viewpoint projection from the narrative into the lower space. And it is even more clear in contexts such as fictive interaction, where the existence of a higher viewpoint space is overtly denied. We can find many more contexts in which the phrase would continue to represent conviction and determination, but the important observation is that each such instance would represent a different viewpoint network, and that the complexity of the interpretation would depend on the viewpoint spaces that would need to be set up.

In the next sections of this paper, I look at two specific (and very different) contexts, to show the crucial role viewpoint configurations play in how Deixis and Direct Discourse Construction are to be understood. I will look at literary discourse and multimodal discourse, to show the role of Direct Discourse in establishing (rather than just fitting into) its Deictic Ground.

The Use of Direct Discourse Construction in Literary Genres

Literary discourse depends to a large degree on the use of DDC, though literary genres use it differently, with different assumptions and goals. A proper discussion of deixis in literary discourse requires a separate paper or book, but the examples below reinforce the points made so far. Literary examples of DDC are numerous, and sometimes complex, so a full discussion is beyond the limits of this paper. In earlier work (Dancygier, 2012), I discussed a number of options, but here I focus on the examples which best represent the correlation between DG and DDC.

Deictic Ground in Novelistic Prose

Dialogue (longer chains of DDCs) plays an important role in novels. In each case there are characters, well identified on the basis of the novel as a whole, communicating from the perspective of their own participation in the events of the plot. The special nature of such dialogues manifests itself on three levels. Firstly, they participate in a fictional story, and so they are embedded in narrative spaces constructed by the author and delivered by a narrator; they refer only to the fictional reality of the novel. Secondly, they are usually not represented in their (assumed) entirety, so that just the content relevant to the story is represented, and some turns can be missed. Thirdly, the uninterrupted flow of discourse is quite different from how natural colloquial conversations would be conducted.

Importantly, novelistic dialogue is a good example of DDG. As I argued in earlier work (Dancygier, 2012), a fictional narrative sets up a Deictic Ground by virtue of relying on two important subjectivities: the narrator and the reader. Time and space are not profiled in such a communicative set-up. While it is true that contemporary novels experiment with such a frame (multiple narrators, fragmented narratives etc.), early novels typically profile a narrator addressing the reader directly–which confirms the underlying deictic set-up. Within that set-up, any dialogic part (DDC), regardless of its form, is adding to the overall higher viewpoint of the novel. The simplification of novelistic dialogue in the ways mentioned above is possible and useful because the ultimate value of DDC is adding to the story as a whole.

A brief illustration in (1) is a conversation from Dave Eggers’ novel A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius. It is a conversation between two brothers–Toph, a middle school kid, and Dave, his older brother and guardian. They are orphans, living on their own. In the episode, Toph comes back from school:

1) “What happened today?” I ask.

“Today Matthew told me that he hopes that you and Beth are in a plane and that the plane crashes and that you both die just like Mom and Dad.”

“They didn’t die in a plane crash.”

“That’s what I said.”

This looks like a rather ordinary conversation: turns are taken, other conversations are reported, etc. The fragment profiles a full DDG (conversation, speaker, addressee, place and time), and includes several instances of Speech and Thought Representation (Matthew told me … , he hopes … , I said … ). However, this deictically complete conversational scene continues in (2), where there is no specified deictic ground, the addressee is generic, and the lines themselves demonstrate a generic attitude.

2) Sometimes I call the parents of Toph’s classmates.

“Yeah, that’s what he said,” I say.

“It’s hard enough, you know,” I say.

“No, he’s okay,” I continue, pouring it on this incompetent moron who raised a twisted boy. “I just don’t know why Matthew would say that. I mean, why do you suppose your son wants Beth and me to die in a plane crash?” (AHWOSG, p. 89)

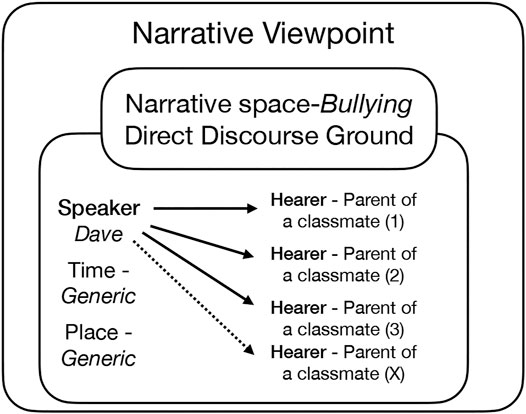

The point in (1), especially the reported conversation, is to give the reader an understanding of how other children treat Toph at school–it sets up the frame of Toph being bullied. There may have been similar conversations, and so the words do not represent one unique instance of bullying, though they are formally immersed in a specific Deictic Ground. In (2), the dialogue switches to a generic mode by relying on present tense (I say, I continue, in the ‘repeated’ or ‘generic’ sense of the verb form) and on the use of Sometimes (confirming a repeated pattern, not a unique instance). Example 2) consists exclusively of lines representing Dave manipulating various parents into feeling guilty, while the ‘parent’ lines are missed as irrelevant. Importantly, each of the lines sets up a Fictive DG, to give the grounding to DDC. The Fictive DG is incomplete (no addressee, specified time, or space), but it plays a role of elaboration on the topic of ‘school bullies’. Together, the lines in (1) and (2) demonstrate an aspect of Toph’s school experience and not any specific conversation. Figure 2 shows how the generic discourse ground yields the meaning intended–communicating to the reader that Toph’s school experience involves bullying.

The possibilities for specific roles DDC can play in a novel are almost endless. But there is a shared goal, which is focused on the DDG’s contribution to the viewpoint structure of the text as a whole. And Fictive DGs play an important role in maintaining the viewpoint structure.

Direct Discourse Construction in Contemporary Poetry

We typically do not think of poetry in deictic terms, and yet contemporary poetry relies on lines from conversations very often. It is enough to consider a poem such as The Applicant, by Sylvia Plath, discussed in detail by Semino (1997) and Freeman (2005). Sequences of DDC, such as … Stitches to show something’s missing? No, no? Then/How can we give you a thing? Stop crying. Open your hand!/Empty? Empty […] use the whole constructional variety of DDC forms, but they do not build off of a deictic Ground set up earlier in the text (as narrative fiction does)–rather, they evoke the Fictive (and incomplete) Deictic Ground by using DDC. The process is thus reversed, and what ties the discourse together is its insertion in specific frames (in the case of The Applicant, an interview and a sales pitch). Constructing an appropriate frame against which DDC lines can be understood is crucial to poetry of this kind.

It is even more visible in a poem like Funeral, by Wisława Szymborska, which consists entirely of lines of discourse (so that there is no voice of the ‘poetic subject’ or ‘poem’s persona’ represented anywhere). The poem is quite long, all written in the style represented in (3):

3) “so suddenly, who could have seen it coming”

“stress and smoking, I kept telling him”“not bad, thanks, and you” “these flowers need to be unwrapped” […]

“you were smart, you brought the only umbrella”

“so what if he was more talented than they were”

“no, it`s a walk-through room, Barbara won`t take it”

“of course, he was right, but that`s no excuse”

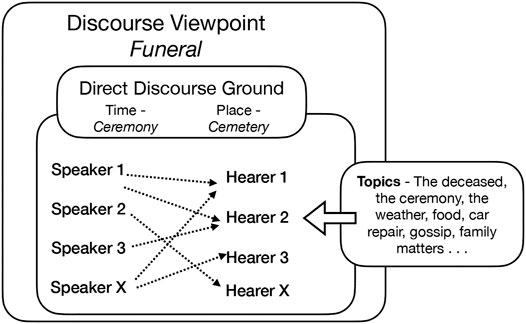

“with body work and paint, just guess how much”

The organizing frame is determined by the title–Funeral. The frame evokes family members or acquaintances who do not see each other often. It also sets up a Fictive Deictic Ground, with a specific place and time, where DDC engages a number of unspecified speakers and addressees. They all participate in conversations–about the deceased but also about various everyday matters. The multiple DDC lines uttered by unidentified speakers to unidentified addressees create an ironic viewpoint–people gathered to mourn are spending a lot of time catching up on gossip instead, and then swiftly disappear into their own lives. The poem constructs an overarching viewpoint on the basis of the shared time and space of these exchanges–it is natural to understand the poem as reflecting the event of the funeral ceremony from its beginning to its end. However, the multiplicity of unspecified speakers and addresees does not match the expected deictic format. Fictive Deictic Ground is needed here so that the disjointed DDC lines can form a DDG structure which gives rise to the ironic view of the event as a whole. The structure of such discourse is represented in Figure 3.

In the literary cases considered above the identities of all participants or the course of the conversations evoked are not central to the viewpoint constructed. The focus is on social situations and the emotional responses of discourse participants. In reading (2), we soon notice that bullying is not really a major concern for Dave or Toph; rather, the brothers respond in a manipulative way, shaming the parents. Similarly in (3), the representation of people engaged in inconsequential chatter in the context of someone’s death creates an ironic viewpoint. Importantly, the use of DDC in literary texts can evoke and set up incomplete Fictive Deictic Grounds, to construct (or ‘demonstrate’) viewpoints needed in the interpretation, rather than faithfully report conversations. In the next section, I consider examples from drama–the literary genre which ostensibly depends entirely on conversations.

Drama

Drama is the literary genre which uses Direct Discourse exclusively, and by definition. Anything said on the stage is ostensibly addressed to someone else (see Dancygier, 2012 for a discussion of the various ‘addressees’). However, the nature of dramatic discourse is much more complex than such a description might suggest. The specificity of dramatic discourse in comparison with spontaneous conversations can be described as follows: 1. Dramatic discourse relies on two major Mental Spaces: the story space, with characters conversing on the stage, and the audience space, populated by silent spectators/listeners; 2. Actors on the stage typically address each other (and not the audience), speaking the words of the characters represented; however, the audience is still the actual addressee; 3. The DDC status of all that is said on the stage is assumed, but the discourse on the stage does not fully comply with our expectations of what spoken discourse does (it can, for example, profile aspects of the narrative which are not directly acted-out on the stage).

One of the important considerations of the discourse of drama is how it represents character’s inner thoughts. In early forms (such as Shakespearean drama), characters often speak to the types of addressees that obviously cannot participate in conversations: objects, bodies, concepts or images, etc. For example, in Romeo and Juliet, such examples abound:

4) a. Come, gentle night, come, loving, black-brow’d night, … (Juliet speaks to the night)

b. Ah, dear Juliet./Why art thou yet so fair? (Romeo speaks to the body of Juliet)

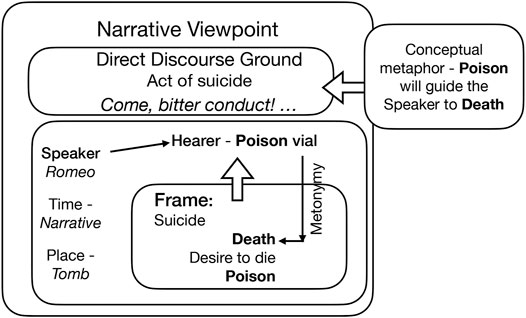

c. Come bitter conduct, come unsavoury guide, … (to the poison he will drink)

d. Eyes, look your last, … (to his eyes, when he looks at Juliet for the last time).

A more thorough look at the discourse of Early Modern drama is beyond the scope of this paper, but what such examples make clear is that inner thoughts and feelings are expressed by addressing entities which are at the center of what the character feels (anticipation of the nightly arrival of the lover, surprise at the beauty of one’s wife even though she is believed to be dead, expectation of relief that poison may bring, intensity of the final moment of parting, etc.). In other words, dramatic discourse sets up Fictive Deictic Grounds and DDCs with improbable addressees (ones that cannot ever be speakers). It is worth noting that such discourse makes full use of the potential of both deixis and DDC–the deictic verb come is used in (4) to talk about an approaching experience (meeting the lover, dying) the speaker desires, the sentences can take imperative or interrogative forms, pronouns are consistent with the speaker or addressee status, etc. In earlier work (Dancygier, 2012), I have referred to such usage as the ‘Vocative cum Imperative’ Construction–a type of literary construction relying on some central features of DDC, identifying the atypical frame-relevant addressee by using a vocative form. What matters from the perspective of this paper is that lines of text structured like DDC are used in incomplete or outright impossible Fictive Deictic Grounds, to make communication of emotions possible via evocation of relevant concepts. But the evocation of Fictive DGs creates Direct Discourse Grounds (DDGs) which house viewpoints relevant to the story (secrecy, surprise, anticipation of death, etc.). Such Fictive DGs also allow for a close connection between embodied action on the stage and the words spoken (holding a poison vial, looking at Juliet, etc.). Example 4c is represented in more detail in Figure 4.

Literary discourse provides much material for analyzing the use of DDC, though I cannot expand the discussion here. But even these limited examples show how literary genres all rely on DDC and Fictive Deixis, profiling the deictic roles in ways appropriate to the genre. Narrative fiction builds a story by setting up complex configurations of mental/narrative spaces, with each of the spaces marking a perspective needed. It uses DDC mainly as ‘demonstration’, whether to represent character’s speech in a specific narrative space, or generic behaviors and conversational patterns recuring in many narrative spaces. Poetry may use DDC in various ways (Dancygier and Vandelanotte, 2009) but also to evoke incomplete Fictive Deictic Grounds. Finally, drama may create specific DDC sub-constructions, to maintain the illusion of speech (against an evoked Fictive Deictic Ground) in order to communicate thoughts and feelings. Unlike the examples of fictive interaction discussed by Pascual, where there is no specific Deictic Ground referred to or evoked, literature requires the setting up of (Fictive) Deictic Grounds, so that DDC can be used, appropriately to the genre, and so that the emergent DDGs contribute to viewpoint networks.

Given that many of the literary Deictic Grounds are incomplete, it is important to ask what aspects of deixis they profile. Judging by the examples above (and other examples I have gathered), the speaker role is the one most fully profiled. The addressee role is filled by various elements of the mental space topology, and often not given any voice at all–this is true in the Eggers example, where parents of school bullies are not profiled as participants, the addressees of gossip lines in Funeral are not identified at all, while addressees in Romeo and Juliet are material objects, body parts, or disembodied concepts (such as night). The speaker is given a privileged role in all these cases.

The analysis so far provides the material needed to explain the concept of Fictive Deixis. Spoken discourse (DDC) is naturally used (in various contexts) to represent attitudes. This is a natural extension of the role of DDC, because the spoken idiom is capable of expressing emotional reactions most efficiently. I follow Vandelanotte (2004) in his explanation of a clear connection between the very concept of DDC and deixis. The approach to deixis that I have built here (focusing on discourse consequences rather than ‘pointing’) allows for two cases: either the DG is set up by other means (as in an extended discourse of a political campaign or a novel), or it needs to be evoked to give legitimacy to DDC, and is thus Fictive–set up for the needs of specific discourse, even if there are no standard deictic dimensions available. But because such an evoked Fictive DG works with DDC to create a mental space with clear topology, the resulting DDG serves the needs of viewpoint construction without relying on all four parameters. The easiest parameters to omit are time and space, but the addressee is also often missing (see ex. 2) or replaced with non-sentient presences (objects, concepts, time of day, etc.). The deictic parameter that cannot be omitted is the speaker, to provide an entry to the viewpoint configuration of the text.

Multimodal Artifacts

The question of the role played by DDC and deixis in various communicative contexts becomes much more complex in artifacts using an image, or a specific design, and also language. I will look briefly at two examples of internet memes, to then consider the phenomenon that I will refer to as ‘street deixis’.

Internet Memes

A genre of contemporary communication which makes a common and quite revealing use of DDC is internet memes. Memes are quite restricted formally, often using predetermined images, text slots, and phrases (Dancygier and Vandelanotte, 2017a). The way they make quick emergence of meaning possible is thus by infusing all formal aspects with maximum of meaning. One of the ways to achieve that goal is via pretend Direct Discourse, used in absence of a Deictic Ground. Examples are numerous, but I will restrict my attention to two representative cases.

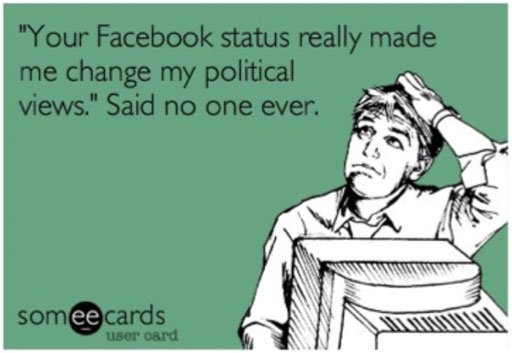

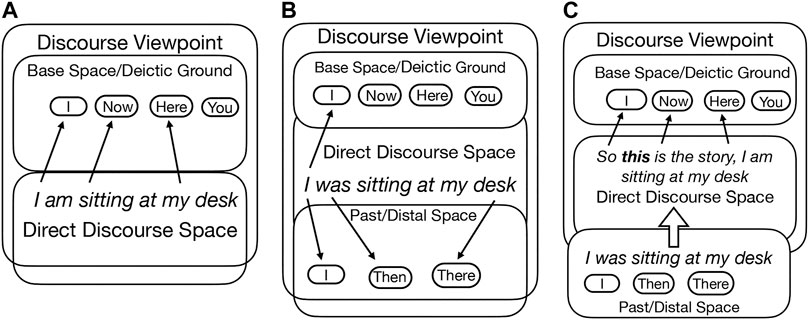

Figure 5 shows one of the early memes (Said no one ever), which starts with a pretend quotation. The sentence quoted is not attributed to any specific speaker or situated in any Deictic Ground. In fact, it is used only to then be explicitly rejected as a possible DDC, by the Said no one ever phrase, communicating the meme-maker’s rejection of the pretend-claim in quotes. The quotation in the meme thus evokes an attitude, somewhat similarly to the funeral conversations in (3), while constructing an ironic viewpoint (see Dancygier and Vandelanotte, 2017a for more discussion).

In Figure 6, one of the Scumbag Steve memes (which express complaints about various annoying misdemeanors), the quotation evokes some people’s irresponsible attitude to the property of their hosts. We should also note that the grammatical structure of the meme has some unusual features: subject suppression (Ruppenhofer and Michaelis, 2010; David, 2016) and disjointed syntax, but also the placement of DDC in a context-free slot, where the viewer has to construct a Deictic Ground and the whole context for the question to make sense. There are thus two Fictive Deictic Grounds evoked: in the Top Text the meme-maker addresses the generic ‘you’, while the other is a fictive situation, not profiling time or space, in which a rude guest (someone like Scumbag Steve, represented in the image macro) uses DDC to refuse to make amends for damaging the host’s property. Importantly, the Bottom Text question in quotation marks is addressed at the host imagined in the Top Text–the you addressee who had something damaged by a careless guest. The meme-viewer is thus a generic addressee of both texts, even though they are attributed to different speakers.

The roles of discourse participants (speaker and addressee) are not identified in these memes, but the presence of DDC calls for an emergence of a Fictive (generic) DG where the speaker and the addressee are profiled. The graded salience of the profiling is characteristic of Fictive DGs, and so the question in Figure 6 can be seen as addressed to any generic person dealing with a rude guest.

The use of you and the way in which some memes involve the viewer as an addressee shows the importance of the form of memetic text in how the Deictic Ground is set up and used. The specific viewpoint networks of these (and other) memes rely on constructing a stance (such as approval/disapproval of people’s beliefs and behaviors), and the viewer, even if addressed, is not a genuine participant in a DDC chain. Further confirmation of the specific nature of multimodal artifacts can be found in street signs–to be discussed in the next section.

Cityscape and ‘Street Deixis’

As we walk the streets of any city, we are constantly bombarded with information–shop windows, street names, parking rules, etc. However, there seems to be a more recent emergence of complex artifacts displayed in windows and on doors. I will consider two kinds of artifacts–standard door or window signs, which can be purchased ready-made by a business owner, and some custom-made displays, related to the specific business. Overall, the signs represent another use of Fictive Deixis. Unlike the literary examples above, these signs do not rely on the surrounding text to provide a viewpoint structure, and so they construct a viewpoint on the basis of the actual location and its function.

Many small businesses rely on storefront signs to notify prospective customers about their business hours,4 and also display a clear sign informing anyone approaching the shop whether it is open or closed. Such businesses typically refer to themselves as we.Figure 7 shows two standard open/closed signs.

The signs use we to mark self-reference, the use of which Levinson (2008) has described as a weaker version of the I deixis. Additionally, the signs perform speech acts which imply a prior action by a prospective customer. Yes We’re Open ostensibly answers a question, such as Are you open? Similarly, the invitation, issued with the use of the deictic verb come (in), appears to respond to a customer who is hesitant whether the business is available. When the shop is closed, it apologizes to the willing customers who were not able to enter (Sorry We’re Closed). Speech acts such as confirmation, invitation and apology are represented, but the actual performance only takes effect when a passer-by decides to stop and look at the sign displayed. In other words, the performance of the speech act relies on Fictive Deictic Ground: the speaker (we, the business) communicates something to a possible addressee, but the speech act is felicitously performed only when there is someone who passes the location of the store (here) at a specific time (now) and who is able and willing to become the recipient of the speech acts made possible by the sign. Still, even if the speech act is understood, it is not linguistically acknowledged (we do not quite imagine a passer-by reading Sorry, We’re Closed and replying out loud That’s all right, I’ll come back later).

There are also signs performing the speech act of giving thanks. Figure 8 represents such an example. The ‘speaker’ is the business, but it is now represented only by that sign, as it no longer sells flowers in the same location. The example instantiates one of the felicity conditions of the speech act of thanking–that the speaker can thank the addressee (metonymically referred to with the name of the neighborhood) for their action in the past mental space, where the act for which the speaker is expressing thanks has been performed. The surprising effect is that the relevant Fictive Deictic Ground is here used to enable the use of DDC between an absent business, a collective addressee, in a former location, and thanking the addressee now for things done in the past.

We should note that other ‘thank you’ acts have the power to set up mental spaces which are not reality spaces–rather, they are set up ‘retroactively’, to fulfill the felicity conditions of the act. This seems to be the case with most of the Thank you for not smoking signs–they prompt a setting-up of a non-factual mental space in the past, present or future, where the viewer of the sign refrains or has refrained from smoking. The addressee is the viewer again, regardless of their intentions and behavior, and the effect expected is to prevent them from smoking, so the thanks can become felicitous. A similar set-up applies in jocular interactions where a participant feels thanks should have been offered but weren’t and says Thank you not to thank the hearer, but, in a sense, to put the thanks in the hearer’s mouth retroactively (the tone of voice is then somewhat sarcastic). Overall, all those ‘thank you’ acts are made felicitous by setting up non-factual or topologically empty mental spaces (Fictive DGs) in which the gratitude-worthy acts exist.

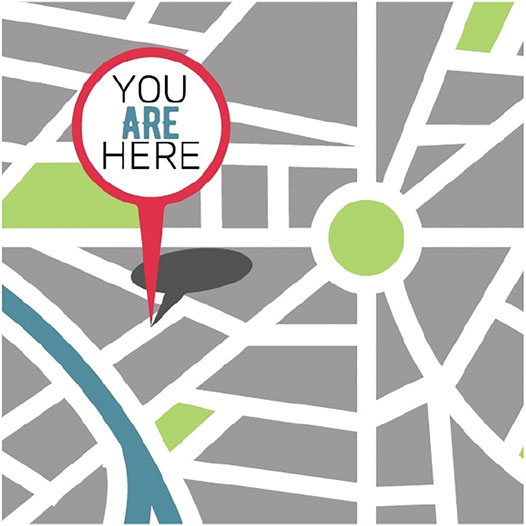

The spatial stability of the business is what drives this kind of cityscape communication. However, there are also instances where signs displayed in cities orient the deictic center to match the location of the addressee. I am referring especially to You are here pointers on maps displayed in various cities (especially historic sites, where tourists might wander and feel lost). A skeletal You are here sign is given in Figure 9.

The central aspect of deixis in these examples is the location, but the construal of what counts as ‘here’ is quite complex. First of all, maps informing people where they are can be found in specific locations, and the role they play is to allow people exploring the city on foot to plan their itinerary to the point of interest that they want to visit. The construal thus starts with someone (tourist information office?) deciding where to locate helpful city maps, and then adding ‘You are here’ signs to mark the location of the map (not of a participant in a conversation!). At this stage no new information is provided to anyone, but the set-up has been created wherein the Deictic Ground is primarily structured by a location (similarly to the business location case discussed above). The people making such maps have to adopt the viewpoint of a person walking around an unfamiliar city and arriving at a map. Such a person needs to design an itinerary which starts at the location of the map. The main point, however, is that the map is a schematic visual representation of a reality of the city. When the marker points to a section of the map and says you are here it actually “says” something more complex. It asks the viewer to first match their real spatial location with the location of the map and the location of the you are here sign on it. The viewer needs to cross-map the location of the map in reality space with the spatial configuration represented by the map–in other words, to figure out the landscape surrounding the marker on the map, and then map it back onto their surroundings in the reality space. So it is not just a construction of two spaces, reality and its representation. It is a complex back and forth between the two spaces, where bits of reality have to be gradually cross-connected to the bits of the representation, in an effort to create a reliable spatial viewpoint. What is particularly interesting about such usage is the opportunistic emergence of the Fictive Deictic Ground when an unspecified passer-by stops to look at the map. The emergent DDG profiles the spatial viewpoint the passer-by needs.

Most of the signs looked at above are quite standard. My final example, however, in Figure 10, combines a number of important dimensions of street deixis5.

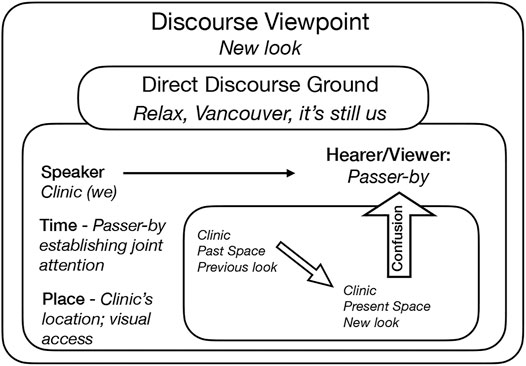

The photo in Figure 10 captures the window of a clinic in Vancouver which has undergone renovations. After the clinic opened for business again, they invited people with this line: Relax, Vancouver, it’s still us. It is another example of DDC used in the context of ‘street deixis’, and it explicitly uses many of the features discussed above:

• Imperative form (Relax): a bit unusually, the sign does not refer to ordinary business interaction. Instead, it speaks to the assumption that clients could be confused (because of the renewed look and appeal of the clinic). The ‘confusion’ frame is thus set up for the viewer to inhabit, whether they are actually confused or not.

• Addressee (Vancouver): similarly to Kitsilano above, this form refers metonymically to all inhabitants of Vancouver.

• Speaker (us): as usual, the clinic refers to itself in the first-person plural form.

• Location (it): though not strictly equivalent to here, this use of the pronoun seems to suggest ‘the business you see here’ rather than an anaphoric reference.

• Time (still): the time adverb still suggests continuation of a past state into the current situation (now)–this is, then, another case where a past mental space is being evoked. This usage refers to what a passer-by sees in the present, while reaffirming the continued identity of the clinic in spite of visual changes.

The structure of the artifact in Figure 10 is diagrammed in Figure 11.

Overall, examples of street deixis rely on the interaction of several phenomena. First of all, they all rely on creating scenes of joint attention, where the passer-by is made to notice the business and the information indicated by the sign. In a sense, the sign deictically points to the relevant communication from the business, and the passer-by may respond. Secondly, the signs are all examples of Direct Discourse Construction, but without the discourse context that determines the deictic center that the discourse builds on. Broadly speaking, it depends on the assumed visual viewpoint of a person walking along a street. When a passer-by sees a written sign and decides to read it, the Fictive Deictic Ground is prompted, in which the passer-by receives the information provided, and thus becomes an addressee. At the same time, the text displayed is understood to have been provided by a ‘speaker’–a business that needs to provide basic information to prospective customers. Even though the text may have been displayed for a while, the Fictive Deictic Ground is triggered only when someone decides to stop by and read. The location is stable (wherever the sign is displayed), but the deictic ‘now’ is reset afresh for every subsequent reader/interlocutor. Importantly, as in other cases discussed, the presence of the decontextualized DDC prompts the setting-up of the Fictive DG. However, what makes these examples different is that the Fictive DG is formed in the context of real, material scenes of joint attention.

In addition to these basic deictic elements, the signs often rely on the deictic verb come or come in, asking those who have stopped to look to make the next step and enter the premises. Also, in some cases the addressee is described as a group, distinguished metonymically with reference to the location they inhabit (Kitsilano, Vancouver). The signs also perform several speech acts–invitation, apology, giving thanks, etc. and rely on the imperative form (which further implies the intended way to see the viewer as an addressee (you)). We should also note the specific use of time and space. The location of the sign becomes the deictic ‘here’ only when someone stops to read the sign; similarly, the time ‘now’ is the brief time of the interaction between a passer-by and a sign. However, past spaces can be evoked and constructed (rather than referenced) to make the speech acts felicitous.

The discourse potential of street deixis is quite limited–first of all because the speaker and the addressee do not engage in turn-taking. At the same time, the limitations of such communicative artifacts are not of the kind which would make them examples of fictive interaction. The information is communicated by someone and received by someone else, and there is an identifiable time and space of the communication–which is not included in the definition of fictive interaction. Also, the ‘demonstration’ status of storefront signs is not uniform, as some signs express a generalizable act of announcing that the store is open or closed, while other signs are more narrowly suited to the purpose, the time and the space. The specificity of such usage is thus due to the use of deixis. Finally, these examples would not fit well into the category of imaginary deixis, because nothing is left to the imagination here. The location, the time, and the presence of a sign are all Base-space, material elements. The information the sign provides is relevant to the nature of the business it represents. But all these parameters do not start forming a Deictic Ground until the information is received by an addressee. Consequently, street deixis examples start by missing an important parameter (an addressee) and become complete once the addressee enters the joint attention pattern and reads the sign. The DDC message remains on display without interruptions, but the Fictive DG is evoked only for the time of interaction between a passer-by and the sign. Also, it does not open an ordinary DDC format, with turn-taking patterns.

Discourse Viewpoint

The range of examples discussed above considers the relationship between Direct Discourse and Deictic Ground in various contexts. I argued that the two phenomena are intricately connected and I have also shown how the Direct Discourse Construction needs to be seen against the foundation of a Deictic Ground–thus forming a more complex structure, the Direct Discourse Ground. To flesh out the way in which DDC and DG co-construct discourse, I have looked at three examples which represent non-standard uses of spoken discourse: literary genres, internet memes, and storefront signs. In each case I argued for an account of how DDC prompts a Fictive DG in absence of an ordinary deictic structure. One of the claims made in the analysis is that Deixis can be seen as a composite concept, such that certain uses do not fill all the parameters.

The question remains how these uses affect viewpoint networks. In my analysis of viewpoint in fictional narratives (Dancygier, 2012), I argued for the concept of Story Viewpoint Space–a narrative (mental) space which gives coherence to the narrative as a whole. Among other things, such a space determines the person and tense of the text, while also explaining how lower-level narrative spaces yield a coherent story governed by the Story Viewpoint Space. In later work, especially Dancygier and Vandelanotte (2016), where we clarified the nature of viewpoint networks in various discourse types, we expanded the concept of the top space governing the viewpoint constructed by the artifacts (including narratives), to propose the Discourse Viewpoint Space. The concept allows for a clear understanding of how discourse progresses by elaborating and texturing the viewpoint structure, and how listeners, readers, and viewers experience discourse as coherent in spite of multiple components and viewpoint shifts.

It is clear that all the artifacts and excerpts discussed above are primarily designed to create viewpointed construals of situations. The viewpoint can be aligned with a character (as in fiction or drama) or with a frame (poetry); it may involve commenting ironically on things people say or do, or engage the viewer in an unplanned interaction aimed at providing information and prompting action. The viewpoints communicated (emotional, ironic or persuasive) are constructed on the basis of setting up Fictive Deictic Grounds in contexts which do not set them up naturally (talking to the poison or to one’s eyes, a ‘talking’ map, an imagined confusion, a business which gives thanks, invites, or apologizes, etc.). They are Fictive Deictic Grounds and they are typically lacking some of the crucial elements of deixis, so the truncated deictic structures do not develop into natural conversations. Instead, they use various forms of DDC to construct DDGs for viewpoints–either by providing a mental space (in a novel or a play) wherein things relevant to the context can be said or by metonymically evoking emotions and attitudes. The role DDC strings play (fictional discourse or metonymic evocation) is determined by the network of viewpoints in which the DDC string is embedded.

Multimodal artifacts construct Discourse Viewpoint on the basis of visual representation spaces and discourse spaces set up. Memes further structure the viewpoint network by separating different discourse spaces (Top Text and Bottom Text) and construct their Discourse Viewpoint by resolving the contrasts set up–in the cases above, criticizing thoughtless statements or condemning rude behavior. Finally, examples of street deixis create a discourse set-up which may function as a speech act (invitation, apology, giving thanks), help structure the experience of the cityscape, etc.

The construction of Discourse Viewpoint is the ultimate goal of such discourses. The artifacts described here (as well as many other ones within the genres discussed and in other discourse contexts) start out by using DDC without its full, proper context, and in absence of a fully profiled DG. To complete at least the minimal deictic parameters required to establish the DDG for Discourse Viewpoint, a Fictive Deictic Ground is established.

Final Comments

I want to close the discussion by pointing out some of the conditions that make the usage described possible, but also interesting. First, why can DDC play so many roles, in spite of its primary function? I argue that the metonymic evocation function of DDC is possible only when the discourse strings used clearly suggest a type of situation and the discourse appropriate to that situation. In other words, not every string of DDC can do the evocation work in the context. This is especially true in the context of a multimodal artifact, where brevity and lack of context make discourse build-up impossible. The examples above support the approach to quotations that treats them as ‘demonstrations’, but requires a more textured approach, depending on the nature of the Deictic Ground in various cases. There are important differences across the discourse types exemplified above.

Examples of street deixis create scenes of joint attention (quite similarly to demonstratives, see Diessel, 2006) by using DDC strings which put the person walking by in the role of a conversation participant–which other artifacts considered do not do, even when, like memes, they use you as a way to engage the viewer. Because the cases of street deixis are crucially dependent on the proximal deictic understanding of space and time, and on engaging the gaze of a passer-by, they are in fact the closest to a default deictic set-up. However, a Fictive DG does not lead to a conversation, to the switching of conversational roles, or a reference to distal phenomena. What the storefront sign communicates, at the moment when attention is achieved, does not lead the recipient of the message to respond to it verbally, but it may prompt the passer-by to respond by acting–e.g. entering the business, returning at a different time, or designing an itinerary suggested by the map. Such cases make it clear that what the Fictive Deictic Ground makes possible in these cases is not only communication, but also action. Importantly, the multimodal nature of the artifacts of street deixis requires an approach which goes beyond images or text, but also include aspects of multimodality in interaction–body posture and eye-gaze first of all.

The difference in deictic salience noted above also helps us define two concepts which need to be clearly distinguished: imaginary vs. fictive. The term ‘fictive’ was used (Talmy, 1996; Talmy, 2020; Matlock 2004) to discuss what has become known as ‘fictive motion’–describing static objects in motion terms, as in The road goes from Vancouver to Kamloops. The term was further extended to ‘fictive vision/fictive experience’ (narrative instances where describing how a character conceptualizes a situation is achieved by describing what she fictively sees (Dancygier, 2012)), and to ‘fictive interaction’ mentioned above (using the language of spoken discourse when no speech takes place (Pascual 2006; Pascual, 2014)). Throughout this paper I have talked about ‘Fictive Deixis’–examples relying on conversational DDC forms suggesting a deictic center when there is in fact no deictic center underlying the discourse, or it is only partial. What these cases share, and what distinguishes them from other discourse uses, is that the language forms evoke real world situations (motion, vision, interaction, deictic grounding) to represent mental construals. Just as the ‘fictive motion’ category above does not ‘imagine’ the road moving (but builds on mental or visual scanning instead), fictive deixis does not set up imaginary deictic grounds–rather, it structures situations in deictic terms to capitalize on the meaning potential of spoken discourse. The concept of Direct Discourse Ground represents the fact that in order to use the potential of spoken discourse, one needs to situate it in a deictic ground–pre-existing one or a fictive one.

Such an approach allows us to notice cross-discourse-genre correlations which are otherwise missed. For example, there are similarities between DDC use in Szymborska’s poem and in internet memes, as examples from both genres are used for the purpose of evocation of more complex discourse appropriate to a frame (a funeral or a complaint). There are interesting correlations between the use of the deictic verb come in dramatic speech to non-human addressees and in storefront signs. There are also similarities and differences among fictive Deictic Grounds which profile non-prototypical hearers (the eyes, the poison, the city, any passer-by, etc.) or fail to profile any recipient at all (as in poetry). There are many aspects of Direct Discourse Constructions which can only be revealed when we consider the nature of the Fictive Deictic Ground as the primary step.

Finally, the approach taken in this paper develops concepts which can help us understand better the differences between literary language and colloquial speech, and between mono-modal and multi-modal artifacts. Further research will uncover other ways in which Fictive Deixis is used in a range of discourse genres.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Funding

This research has been funded by Insight Grant 435-2015-0158, Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC).

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank my colleagues Lieven Vandelanotte (University of Namur, Belgium), Anna Bonifazi (University of Cologne, Germany), Arie Verhagen (Leiden University, The Netherlands), and Wei-lun Lu (Masaryk University, Brno, Czech Republic). Their insights and support have helped me greatly throughout the writing process.

Footnotes

1I am referring here only to the work in which gesture and eye-gaze are discussed specifically in the context of deixis; there is a much larger body of work on gesture and eye-gaze focused on viewpoint management and other aspects of meaning construal (eg., Sweetser and Stec 2016; Brône et al., 2017). However, a broader discussion of these aspects of multimodality in interaction cannot be addressed in this paper.

2It might be worth pointing out here that some of the discussion of deixis to be found in Bühler 1990 [1934/1984] could quite naturally be reconsidered and further specified in terms of MST.

3I will deliberately skip the discussion of Free Indirect Discourse, which blends the two Deictic Grounds. The workings of the distal versus proximal choices are more complex in FID, and it is worth a separate discussion, but it would not add much to my argument.

4Business restrictions related to COVID-19 have prompted a major re-construal of storefront signs. There is on-going work on the patterns of form and meaning which have emerged as a result–the primary observation is that the storefront communication became much more personal and emotional. The work has also demonstrated the efficiency and flexibility of this form of communication (see Dancygier et al. forthcoming). (Feyaerts and Heyvaerts, 2021).

5Many thanks to Thomas McCullough for sharing this example with me.

References

Brisard, F. (Editor) (2012). Grounding: The Epistemic Footing of Deixis and Reference. Berlin/Boston: De Gruyter, Inc.

Brône, G., Oben, B., Jehoul, A., Vranjes, J., and Feyaerts, K. (2017). Eye Gaze and Viewpoint in Multimodal Interaction Management. Cogn. Linguistics 28 (3), 449–483.

Bühler, K. (1990 [1934/1984]). Theory of Language: The Representational Function of Language, Vol. 25. Philadelphia: J. Benjamins Pub. Co, first published.1934.

Clark, H. H. (2016). Depicting as a Method of Communication. Psychol. Rev. 123 (3), 324–347. doi:10.1037/rev0000026

Clark, H. H., and Gerrig, R. J. (1990). Quotations as Demonstrations. Language 66 (4), 764–805. doi:10.2307/414729

Cornish, F. (2011). 'Strict' Anadeixis, Discourse Deixis and Text Structuring. Lang. Sci. 33 (5), 753–767. doi:10.1016/j.langsci.2011.01.001

Dancygier, B., and Sweetser, E. (Editors) (2012). Viewpoint in Language: A Multimodal Perspective (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

Dancygier, B. (2017). Viewpoint Phenomena in Constructions and Discourse. Glossa 2 (1), 37. doi:10.5334/gjgl.253

Dancygier, B. (2019). Proximal and Distal Deictics and the Construal of Narrative Time. Cogn. Linguistics 30 (2), 399–415. doi:10.1515/cog-2018-0044

Dancygier, B., Lu, W., and Verhagen, A. (Editors) (2016). Viewpoint and the Fabric of Meaning: Form and Use of Viewpoint Tools across Languages and Modalities (Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton), Vol. 55.

Dancygier, B., and Sweetser, E. (2005). Mental Spaces in Grammar: Conditional Constructions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/cbo9780511486760

Dancygier, B. (2012). The Language of Stories: A Cognitive Approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Dancygier, B., and Vandelanotte, L. (2009). “Judging Distances: Mental Spaces, Distance, and Viewpoint in Literary Discourse,” in Cognitive Poetics: Goals, Gains and Gaps. Editors G. Brône, and J. Vandaele (Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter), 319–370.

Dancygier, B., and Vandelanotte, L. (2016). “Discourse Viewpoint as Network,” in Viewpoint and the Fabric of Meaning: Form and Use of Viewpoint Tools across Languages and Modalities. Editors B. Dancygier, W. Lu, and A. Verhagen (Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter), 13–40. doi:10.1515/9783110365467-003

Dancygier, B., and Vandelanotte, L. (2017a). Internet Memes as Multimodal Constructions. Cogn. Linguistics 28 (3), 565–598. doi:10.1515/cog-2017-0074

Dancygier, B., and Vandelanotte, L. (Editors) (2017b). Special Issue: Viewpoint Phenomena in Multimodal Communication. Cogn. Linguistics, 28 (3).

Dancygier, B., Lee, D., Lou, A., and Wong, K. Forthcoming “Standing Together by Standing Apart: Distance, Safety, and Fictive Deixis in the COVID-19 Storefront Communication,” in COVID 19: Metaphor and Metonymy Across Languages And Cultures. Editors X. Wen, W-L. Lu, and Z. Kövecses, (Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company).

David, O. (2016). Metaphor in the Grammar of Argument Realization. PhD dissertation: Berkeley: University of California.

Diessel, H. (2006). Demonstratives, Joint Attention, and the Emergence of Grammar. Cogn. Linguistics 17 (4), 463–489. doi:10.1515/cog.2006.015

Duchan, J. F., Bruder, G. A., and Hewitt, L. E. (Editors) (1995). Deixis in Narrative: A Cognitive Science Perspective (Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates).

Dudis, P. G. (2004). Body Partitioning and Real-Space Blends. Cogn. Linguistics 15 (2), 223–238. doi:10.1515/cogl.2004.009