94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

PERSPECTIVE article

Front. Commun., 29 April 2021

Sec. Science and Environmental Communication

Volume 6 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomm.2021.586297

This article is part of the Research TopicNew Directions in Science and Environmental Communication: Understanding the Role of Online Video-Sharing and Online Video-Sharing Platforms for Science and Research CommunicationView all 23 articles

Scientific information is a key ingredient needed to tackle global challenges like climate change, but to do this it must be communicated in ways that are accessible to diverse groups, and that go beyond traditional methods (peer-reviewed publications). For decades there have been calls for scientists to improve their communication skills—with each other and the public—but, this problem persists. During this time there have been astonishing changes in the visual communication tools available to scientists. I see video as the next step in this evolution. In this paper I highlight three major changes in the visual communication tools over the past 100 years, and use three memorable items—bamboo, oil and ice cream—and analogies and metaphors to explain why and how Do-it-Yourself (DIY) videos made by scientists, and shared on YouTube, can radically improve science communication and engagement. I also address practical questions for scientists to consider as they learn to make videos, and organize and manage them on YouTube. DIY videos are not a silver bullet that will automatically improve science communication, but they can help scientists to 1) reflect on and improve their communications skills, 2) tell stories about their research with interesting visuals that augment their peer-reviewed papers, 3) efficiently connect with and inspire broad audiences including future scientists, 4) increase scientific literacy, and 5) reduce misinformation. Becoming a scientist videographer or scientist DIY YouTuber can be an enjoyable, creative, worthwhile and fulfilling activity that can enhance many aspects of a scientist’s career.

“Science is guided by its metaphors” (Phillips, 2009).

“Analogy is the motor of the car of thought” (Hofstadter, 2001).

“Video is the next wave, and scientist must be prepared for it” (McKee, 2013).

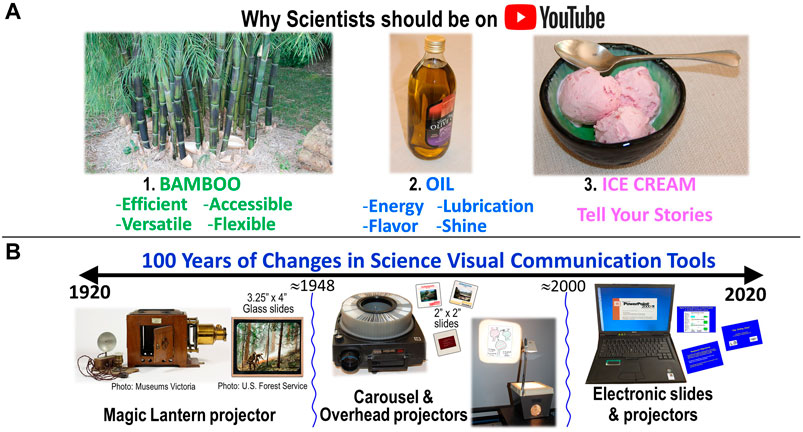

Scientific information is a key ingredient needed to tackle global challenges like climate change, health care for all, environmental conservation, and sustainable agriculture. But to do this it must be communicated broadly and in ways that are accessible to diverse groups (Nisbet and Scheufele, 2009; Canfield et al., 2020), and that go beyond the traditional methods such as peer-reviewed publications (Wilcox, 2012; Brossard, 2013; Eagleman, 2013; Liang et al., 2014; National Academies of Sciences, 2017). This is perhaps most urgent in the applied environmental sciences where research results can be readily adopted by stakeholders and appreciated by the general public. In this paper I use three memorable items (Figure 1A), analogies and metaphors to explain why I think that Do-it-Yourself (DIY) videos made by scientists and shared on YouTube can help in these efforts. I hope this will convince more scientists like me, with no formal video training, to start making videos.

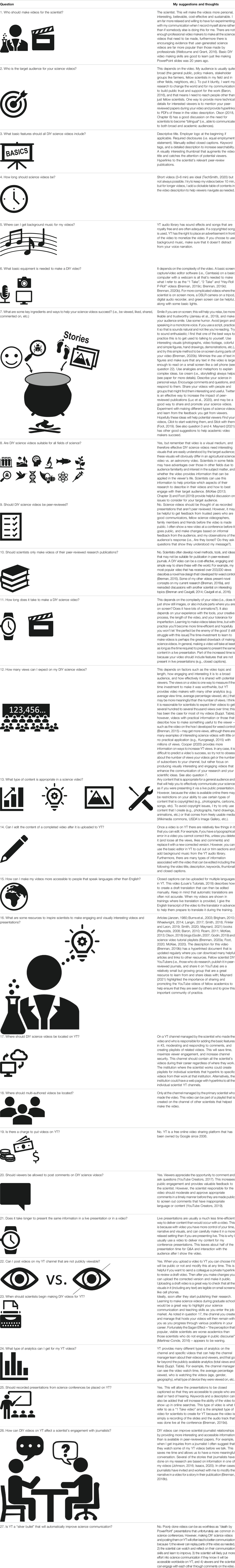

FIGURE 1. Three memorable items to help remind scientists why Do-It-Yourself YouTube videos are important for science communication (A), and three major changes in science communications tools from 1920 to 2020 (B).

This paper expands on a presentation I gave at a large agricultural science conference (Brennan, 2019a) in a symposium titled ‘Science Communication Hacks to Increase Public Engagement - Accessible Tools for Time-Limited Professionals’. When I received the invitation, I had to look up the definition of “hack”, and the ones I like best are from the online Urban Dictionary: “a clever solution to a tricky problem”, and “to modify or change something in an extraordinary way.” The invitation was a perfect venue for me to share ideas that I had been mulling over for years as I learned to make science videos, and navigate the “brave new world of science communication” (Dudo, 2015).

YouTube was created in 2005. But I believe that my journey to use videos to share my science on YouTube began in the 1960s–80s when I was growing up in Papua New Guinea, thanks in large part to my father who worked in linguistics and anthropology. He was an avid photographer who worked to document and preserve the rich traditions of the Enga people (Wiessner and Tumu, 2013) whom we lived among, and I always enjoyed listening to him tell stories of our experiences there using 2 × 2 inch slides. That inspired me to begin my own slide collection as a U.S. Peace Corps volunteer in Thailand (Brennan, 1990). I was soon using those slides along with my hand drawings on overhead projector sheets for agroforestry presentations I gave in Thailand, and in other parts of Asia and Africa where I worked before graduate school. My slides were essential in the lectures that I gave as a teaching assistant in graduate school. Many of my students had not been to the tropics and my slides allowed me to “take” them there and “meet” the farmers whom I worked with. In 2000 near the end of my PhD, my wife and I purchased a video camera when our first child was born. And soon, in addition to filming our son learning to walk, I was using the camera to record how leaf waxes affected insect walking (Brennan and Weinbaum, 2001). That inspired my first science video that I showed during my final presentation for my PhD.

My efforts and interest to share my science on YouTube began with a video (Brennan, 2014) on my research on interplanting flowers with organic lettuce to control insect pests (Brennan, 2013). I made the video for the 2013 annual meeting of the American Society of Horticultural Science that I could not attend. A friend at the meeting ensured that my video was shown in the session where I was scheduled to speak. A farmer was one of about 20 people in that session and emailed to ask if it was on YouTube. This motivated me to upload it to YouTube. Since 2014, this video has received an average of about 3,500 views annually, and has been joined by 25 other videos which I made that have received more than 328,000 combined views (Supplementary Table S1). For comparison, the paper (Brennan, 2013) that my first YouTube video was based on has only been cited 28 times.

I share this history of my journey to YouTube for two reasons. First, to illustrate that my passion and motivation for using effective, modern, visual tools for science communication comes from years of working with diverse groups—students, farmers, volunteers, extension agents, university faculty—in many countries. During this time, I strived to learn how to best communicate complex ideas about sustainable agriculture—often in more than one language—to people with very different educational and cultural backgrounds. And second, to illustrate how DIY science videos on YouTube can substantially increase the reach of scientific research. These visual tools have evolved in radical ways over the past 100 years (Figure 1B) (Myers, 1948; Burger, 1958; Shepard, 1987; Ervin, 2003; Velarde, 2019). The necessary transition from one communication tool to the next has often been resisted or viewed skeptically by scientists (DrDoyenne, 2010; Bik and Goldstein, 2013; McKee, 2013, Chapter 2). However, I consider DIY science videos as a natural step in this evolution of visual communication tools, and below I explain this with bamboo, oil and ice cream.

Tubes are ubiquitous structures in biology because they are an efficient way to get things done, whether it is moving water via the tubular xylem in the plants that provide our food, or air to your lungs via your windpipe and oxygenated blood through your arteries. Similarly, YouTube is one of the fastest and most efficient ways to communicate ideas visually. For example, my first video on YouTube has been viewed over 20,000 times compared to the 20 views that it received at the conference described above. Bamboo is one of the fastest growing plants in the world (Kleinhenz and Midmore, 2001) in large part because of its hollow tubular stems. The visually attractive, jointed stems of bamboo can remind us of the efficiency of YouTube as a science communication tool, in addition to it helping us to learn to do other important things like how to fix a leaky faucet.

Bamboo is often called the “poor man’s timber” because it is an inexpensive and accessible building material for people with limited financial resources in many countries (Perez et al., 1999; Lobovikov et al., 2012; Kumar, 2015). This reminds me of how YouTube can act as an open-access university where people worldwide can learn interesting and useful things that otherwise would be restricted to the few fortunate groups who had an opportunity to attend university. Even if a scientist’s papers are not open-access—which unfortunately remains a problem with publicly funded research—DIY videos can essentially make the research open-access but in more visually interesting and personal ways. I believe this will promote inclusive science communication (Canfield et al., 2020). These videos can also help scientists connect with and inspire diverse groups of students to become the next generation of scientists, and help to break down stereotypes of scientists (i.e., “competent but cold” (Fiske and Dupree, 2014); “white, old men” (Reif et al., 2020); women “lack the qualities to be successful scientists” (Carli et al., 2016).

Of the world’s economically important grasses, none rivals bamboo in its versatility (Soderstrom and Calderon, 1979). For example, during my childhood in Papua New Guinea, I saw bamboo used to carry water and to make woven walls, bow strings, arrow shafts, smoking pipes, knives, mouth harps, toys, and even start friction fires. Bamboo’s versatility comes from the unique shape and structure of its light-weight stems and the extraordinary physical and mechanical properties of its fibers that were even used for the filament in Thomas Edison’s incandescent light bulb (Levy, 2002, p. 124). Porterfield (1933) wrote that “bamboo is one of those providential developments in nature which, like the horse, the cow, wheat and cotton, have been indirectly responsible for man’s own evolution.” Likewise, YouTube provides scientists with the most versatile and flexible communication tool ever developed that is only limited by our creativity. For example, DIY science videos can vary from a basic screen capture recording of a live conference presentation, up to a more complex video where a scientist uses a green screen to place themself in front of visuals (Brennan, 2019d). Moreover, these can be made with relatively simple and inexpensive equipment and software (Brennan, 2019c) that is often less than half the price to attend a professional scientific conference.

DIY science videos can “energize” the information in our peer-reviewed publications, and “lubricate” it so that it moves out to the broader world where it can have far more impact than if it remains stuck or fused to the library shelves of academia that are accessible to relatively few. Consider for example the paper (Brennan, 2013) that my first YouTube video was based on which has only been cited 28 times. From this record, one might erroneously conclude that this research has had little impact, however, the 20,000 plus views and more than 300 “likes” that the video received tells the opposite story.

The science literature where we share our “exciting” research with the world is unfortunately often boring and difficult to read even by scientists (Sand-Jensen, 2007; Doubleday and Connell, 2017b). In other words, this literature is often “bloated, dense and so dry that no amount of chewing can make it tasty” (Doubleday and Connell, 2017a). However, I like to think of this literature like overly pungent raw onions that can be transformed into delicious and inviting food when they are gently fried in cooking oil.

I have always enjoyed working with my hands to create something of beauty from rough pieces of wood. One of the most satisfying parts of this process comes at the end, after sanding, when oil is rubbed into the wood to bring out the grain, colors and patterns that are often hidden below the surface. This is much like how DIY science videos can make our hard-earned research shine and sparkle in visual ways that go far beyond what is often seen in our papers.

I’ve often wondered when I “became a scientist.” If I had to choose a milestone it would be somewhere during the process of writing and successfully publishing my first, lead authored paper on research that I initiated during my M.S. degree (Brennan and Mudge, 1998). I call that first paper my “ice cream paper” because the topic of my paper was a tropical tree that is commonly called the ice cream bean. Now regardless of whether your first, lead authored science paper was on dung beetles or intestinal parasites, I will still call it your “ice cream paper.” I hope that the ice cream connection to YouTube will also be memorable simply because ice cream is such a delicious dessert—although I suggest you serve it to your viewers throughout your videos. In any case, what has always concerned me about my “ice cream paper” is that it did not allow me to share the interesting and somewhat serendipitous story that inspired me to study that amazing tree. This is a common issue with much of the peer-reviewed literature, not just our “ice cream papers”. And that is where video can help.

DIY videos provide scientists with an opportunity to tell the stories behind their research. This can add valuable artistic and human touches to the work that make it and the scientist more accessible. This is in keeping with the compelling title and message of the first book I read on science communication “Don’t be such a Scientist” (Olson, 2009). Perhaps after people learn about the stories and serendipity (Meyers, 1995) in our research, they’ll muster up the courage to wade, or dive into the gory details in our papers and find the valuable nuggets that are often hidden so well in our statistical analyses and dry language. One of my lofty goals is to produce at least one video that describes some broadly interesting aspect or story behind each of my papers. Perhaps the video on my “ice cream paper” will start like this: “You’ve probably heard of the story of Jack and the Bean Stalk, right? Although I didn’t like reading as a kid, that story was one of my favorites because I loved to climb trees and garden. But, I want to tell another story that I call “Eric and the Ice Cream Bean”. It started on a warm summer day on the North Shore of Oahu, Hawaii, about 30 years ago when I looked in a garbage can….” My gut feeling is that this video will radically increase the potential impact of the research in my “ice cream paper” that has only been cited seven times in the peer-reviewed literature even though I’m arguably one of the world’s “experts” on the science of clonal propagation of ice cream bean trees.

I hope that the metaphors and analogies I used will help you understand and remember why and how scientists can radically improve science communication by making DIY videos that are shared on YouTube. While there have been many calls for better science communication (Bragg, 1966; Janzen, 1980; Royal Society, 1985; Baron, 2010; Brigham, 2010; Kahan, 2010; Wilcox, 2012; Wheelwright, 2014; Baron, 2016; Langin, 2017; Olson, 2018), unfortunately, the problem persists. This is partly because most scientists lack training in effective science communication (Brownell et al., 2013; Simis et al., 2016) and often see it as a one-way transfer of information (Davies, 2008) not a dialogue. The problem is exacerbated by myths (Burke, 2015) and misunderstandings (Varner, 2014; Simis et al., 2016) among scientists about public understanding of science, such as the knowledge deficit model of science communication. This alluring model assumes that people are skeptical about scientific issues (i.e., vaccines, climate change, GMOs) because they lack knowledge or understanding, and that providing them with knowledge will change their thinking, or simply put “To know science is to love science” (Turney, 1998). DIY science videos are not a silver bullet that will automatically solve these communication problems, but perhaps they will help us to focus and reflect more on our science communication skills and approaches as we watch our videos and work to improve. Self-reflection is an often overlooked yet primary benefit of DIY video making (McCammon, 2014).

Are you ready to take the bold step of making DIY science videos for YouTube? I hope so, but I also understand why you might be reluctant (i.e., lack of time and equipment, lack of interest, institutional barriers, fear of failure, etc.). To help you understand these and potentially become a scientist videographer (McKee, 2013) – or scientist DIY YouTuber – I addressed several important questions and concerns that you might have (Table 1). I also created a growing series of videos (Brennan, 2020a) that explain the basic tools that I use, different types of videos that you can make from simple to more complex, resources that have inspired me, and my video making process.

TABLE 1. Important questions to consider when producing Do-It-Yourself (DIY) science videos, and organizing and managing them on YouTube (YT). Please email me if you have other questions that I have not addressed.

Making interesting and engaging DIY videos is a worthwhile time investment if you consider how it can radically increase the impact of your research. Furthermore, these videos are an excellent way for scientists to have a voice online to increase scientific literacy, meaningful engagement and help to reduce misinformation that is increasingly prevalent (Menezes, 2018) and often propagated on YouTube (Basch et al., 2015; Allgaier, 2019; D'Souza et al., 2020; Tokojima Machado et al., 2020) and other social media platforms (Thaler and Shiffman, 2015). Online videos may make you vulnerable to more criticism (and praise) than typically occurs with other forms of science communication. This will challenge you to improve in surprising ways, and develop new persuasion skills (Hornsey and Fielding, 2017) that could benefit other aspects of your career (writing, teaching, live presentations, grant writing, etc.). Keep in mind that making science communication videos is a journey, not a destination. So have fun experimenting and being yourself as you find your voice on YouTube.

Speaking of fun, I believe that DIY science video making should be enjoyable, as you can see in some of the unorthodox approaches I use in my videos. In a recent study, Besley et al. (2018) investigated what motivates scientists to engage with the public, in other words “what gets scientists out from behind their computer screens and lab benches.” What they found made me smile because it agrees with what motivates my DIY video making efforts. The most consistent predictors of engagement in the study were the beliefs that the scientist would enjoy the experience and that it would have a positive impact. This type of research is critical to improve science communication engagement, and address barriers to participation (Poliakoff and Webb, 2007; Ho et al., 2020).

Learning to make science videos has been one of the most rewarding, creative, and satisfying activities that I have done as a scientist because it makes me feel that the science I love doing is worthwhile and is having a much greater impact than my peer-reviewed papers alone could achieve. I admit that my advocacy for YouTube as a science communication tool is somewhat surprising given that I grew up in a country without television. But it makes sense because this format has allowed me to share my passion for science, and make connections and engage with diverse groups of people around the world from elderly neighbors and local farmers, to students from elementary school to university, and childhood friends from the other side of our planet. I hope it has similar benefits for you. If these thoughts help nudge you to make science videos, please contact me so that I can be one of the first to subscribe to your YouTube channel.

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

I am grateful to Richard Rosecrance, Paul Brennan, Jason Brennan and James McCreight who provided input to improve this article. I also appreciate the constructive comments by the reviewers.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcomm.2021.586297/full#supplementary-material.

Allgaier, J. (2019). Science and environmental communication on YouTube: strategically distorted communications in online videos on climate change and climate engineering. Front. Commun. 4 (36). doi:10.3389/fcomm.2019.00036

Baron, N. (2010). Escape from the ivory tower: a guide to making your science matter. Washington, DC: Island Press.

Basch, C. H., Basch, C. E., Ruggles, K. V., and Hammond, R. (2015). Coverage of the ebola virus disease epidemic on YouTube. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 9 (5), 531–535. doi:10.1017/dmp.2015.77

Besley, J. C., Dudo, A., Yuan, S., and Lawrence, F. (2018). Understanding scientists' willingness to engage. Sci. Commun. 40 (5), 559–590. doi:10.1177/1075547018786561

Bik, H. M., and Goldstein, M. C. (2013). An introduction to social media for scientists. Plos Biol. 11 (4), e1001535. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001535

Bragg, L. (1966). The art of talking about science. Science 154, 1613–1616. doi:10.1126/science.154.3757.1613

Brennan, E. B. (1990). “Using farmers and their ideas for effective extension work,” in Proceedings of strategies and methods for orienting multipurpose tree system research for small scale farm use. Editors C. Haugen, M. Medema, and C. B. Lantican, Jakarta, Indonesia: Forestry/Fuelwood Research and Development Project (F/FRED), International Development Research Centre of Canada). 94–97.

Brennan, E. B. (2013). Agronomic aspects of strip intercropping lettuce with alyssum for biological control of aphids. Biol. Control. 65 (3), 302–311. doi:10.1016/j.biocontrol.2013.03.017

Brennan, E. B. (2014). Efficient intercropping for biological control of aphids in transplanted organic lettuce. Available at: www.youtube.com/watch?v=KVLgt2_J1Wk (Accessed October 21, 2020). doi:10.4324/9781315756257

Brennan, E. B. (2015). How to make an inexpensive hoe for efficient weeding, “Recycle Strap Hoe”. Available at: www.youtube.com/watch?v=woHNgHkbWzA (Accessed October 21, 2020).

Brennan, E. B. (2018a). Juicing cover crops.... Are you Nuts? Maybe but hear me out!. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=H1GfRurgqKI (Accessed October 21, 2020).

Brennan, E. B. (2018b). Novel equipment and ideas for using cover crops on vegetable beds. Am. Vegetable Grower 66 (1), 36–42. doi:10.1023/A:1006594207046

Brennan, E. B. (2019a). “Why should scientists be on YouTube? Bamboo, oil & ice cream,” in Embracing the digital age. (San Antonio, TX: American Society of Agronomy, Crop Science Society of America, Soil Science Society of America). Available at: https://youtu.be/Ldf_6gbYJn0 (Accessed July 18, 2020).

Brennan, E. B. (2019b). Resources to inspire interesting diy science videos and presentations. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4HITsoOqkPg (Accessed October 21, 2020).

Brennan, E. B. (2019c). Three tools to make science videos for YouTube. Available at: https://youtu.be/LvJPBgZPHuc (Accessed October 21, 2020).

Brennan, E. B. (2019d). Three types of DIY videos that scientists can make. Available at: https://youtu.be/KOUrERx0uPk (Accessed October 21, 2020).

Brennan, E. B. (2020a). DIY video making tips/tutorials for scientists, teachers & other educators. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLn2iLaALBpErQ5DAY7Mmonb6b9NzVqyMX (Accessed September 23, 2020).

Brennan, E. B. (2020b). A novel DIY video making method for busy teachers, professors & scientists. Available at: https://youtu.be/2UHfaRF0TEY (Accessed October 21, 2020).

Brennan, E. B. (2020c). Using Camtasia to make visually-interesting, engaging, educational videos during COVID-19 & beyond. Available at: https://youtu.be/EK71QW4vSzA (Accessed October 21, 2020).

Brennan, E. B., and Mudge, K. W. (1998). Vegetative propagation of Inga feuillei from shoot cuttings and air layering. New Forests 15 (1), 37–51. doi:10.1023/a:1006594207046

Brennan, E. B., and Cavigelli, M. A. (2014). Organic versus conventional comparison - a devil without details. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=os-aM4FqPUA (Accessed October 21, 2020). doi:10.4324/9781315756257

Brennan, E. B., and Weinbaum, S. A. (2001). Effect of epicuticular wax on adhesion of psyllids to glaucous juvenile and glossy adult leaves of Eucalyptus globulus Labillardiere. Aust. J. Entomol. 40, 270–277. doi:10.1046/j.1440-6055.2001.00229.x

Brigham, R. M. (2010). Talking the talk: giving oral presentations about mammals for colleagues and general audiences. J. Mammalogy 91 (2), 285–292. doi:10.1644/09-mamm-a-271.1

Brossard, D. (2013). New media landscapes and the science information consumer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110 (Suppl 3), 14096–14101. doi:10.1073/pnas.1212744110

Brownell, S. E., Price, J. V., and Steinman, L. (2013). Science communication to the general public: why we need to teach undergraduate and graduate students this skill as part of their formal scientific training. J. Undergrad Neurosci. Educ. 12 (1), E6–E10.

Burger, A. W. (1958). Preparation of transparencies (slides) for use with overhead projectors in agronomic education 1. Agron. J. 50 (8), 495. doi:10.2134/agronj1958.00021962005000080029x

Burke, K. L. (2015). 8 Myths about public understanding of science. American Scientist [Online], Available at: http://www.americanscientist.org/blog/pub/8-myths-about-public-understanding-of-science (Accessed July 18, 2020) .

Burns, T. W., O'Connor, D. J., and Stocklmayer, S. M. (2003). Science communication: a contemporary definition. Public Underst Sci. 12 (2), 183–202. doi:10.1177/09636625030122004

Canfield, K. N., Menezes, S., Matsuda, S. B., Moore, A., Mosley Austin, A. N., Dewsbury, B. M., et al. (2020). Science communication demands a critical approach that centers inclusion, equity, and intersectionality. Front. Commun. 5 (2). doi:10.3389/fcomm.2020.00002

Carli, L. L., Alawa, L., Lee, Y., Zhao, B., and Kim, E. (2016). Stereotypes about gender and science. Psychol. Women Q. 40 (2), 244–260. doi:10.1177/0361684315622645

Cavigelli, M., Tomeck, M. B., and Brennan, E. B. (2016). What our organic gardens taught us about the challenges of organic regulations. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gOhXMYfgLoI (Accessed October 21, 2020).

Cooper, P. (2020). How does the YouTube Algorithm work? A guide to getting more views. Available at: https://blog.hootsuite.com/how-the-youtube-algorithm-works/ (Accessed September 21, 2020).

D'Souza, R. S., D'Souza, S., Strand, N., Anderson, A., Vogt, M. N. P., and Olatoye, O. (2020). YouTube as a source of medical information on the novel coronavirus 2019 disease (COVID-19) pandemic. Glob. Public Health 15 (7), 935–942. doi:10.1080/17441692.2020.1761426

Davies, S. R. (2008). Constructing communication. Sci. Commun. 29 (4), 413–434. doi:10.1177/1075547008316222

Doubleday, Z. A., and Connell, S. D. (2017b). Publishing with objective charisma: breaking science's paradox. Trends Ecol. Evol. (Amst) 32 (11), 803–805. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2017.06.011

Doubleday, Z., and Connell, S. (2017a). Bored reading science? Let’s change how scientists write. The Conversation (Online). Available at: https://theconversation.com/bored-reading-science-lets-change-how-scientists-write-81688 (Accessed July 18, 2020).

DrDoyenne, (2010). The future of science communication. Available at: http://womeninwetlands.blogspot.com/2010/02/future-of-science-communication.html (Accessed June 23, 2020).

Dudo, A. (2015). Scientists, the media, and the public communication of science. Sociol. Compass 9 (9), 761–775. doi:10.1111/soc4.12298

Eagleman, D. M. (2013). Why public dissemination of science matters: a manifesto. J. Neurosci. 33 (30), 12147–12149. doi:10.1523/jneurosci.2556-13.2013

Ervin, J. D. (2003). In praise of an old warhorse - despite impending changes, the overhead projector lives on. Entertainment Des. 37 (12), 22.

Finkler, W., and Leon, B. (2019). The power of storytelling and video: a visual rhetoric for science communication. Jcom 18, A02. doi:10.22323/2.18050202

Fiske, S. T., and Dupree, C. (2014). Gaining trust as well as respect in communicating to motivated audiences about science topics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111 (Suppl 4), 13593–13597. doi:10.1073/pnas.1317505111

Foot, G. (2020). Talking science: an introduction to science communication. YouTube course. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLD160RWuGai9oUnAVRq-GD2njEo1XHadF (Accessed September 23, 2020).

Godin, S. (2007). Really bad powerpoint. Available at: https://seths.blog/2007/01/really_bad_powe/ (Accessed July 14, 2020).

Godin, S. (2019). “Scrappy” is not the same as “crappy”. Available at: https://seths.blog/2019/07/scrappy-is-not-the-same-as-crappy/ (Accessed July 14, 2020).

Ho, S. S., Looi, J., and Goh, T. J. (2020). Scientists as public communicators: individual- and institutional-level motivations and barriers for public communication in Singapore. Asian J. Commun. 30, 155–178. doi:10.1080/01292986.2020.1748072

Hofstadter, D. R. (2001). “Analogy as the core of cognition,” in The analogical mind: perspectives from cognitive science. Editors K. J. H. Dedre Gentner, and B. N. Kokinov Cambridge, MA: The MIT Pres/Bradford Book Available at: https://prelectur.stanford.edu/lecturers/hofstadter/analogy.html (Accessed July 18, 2020).

Hornsey, M. J., and Fielding, K. S. (2017). Attitude roots and jiu jitsu persuasion: understanding and overcoming the motivated rejection of science. Am. Psychol. 72 (5), 459–473. doi:10.1037/a0040437

Isaacs, J. (2020). Juicy new approaches in cover cropping. Fruit & Vegetable [Online]. Available at: https://www.fruitandveggie.com/juicy-new-approaches-in-cover-cropping/ (Accessed July 17, 2020).

Jarreau, P. B., Cancellare, I. A., Carmichael, B. J., Porter, L., Toker, D., and Yammine, S. Z. (2019). Using selfies to challenge public stereotypes of scientists. Plos One 14 (5), e0216625. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0216625

Kahan, D. (2010). Fixing the communications failure. Nature 463 (7279), 296–297. doi:10.1038/463296a

Kleinhenz, V., and Midmore, D. J. (2001). Aspects of bamboo agronomy. Adv. Agron. 74, 99–153. doi:10.1016/s0065-2113(01)74032-1

Kumar, T. M. (2015). Bamboo “poor men timber”: a review study for its potential & market scenario in India. IOSR J. Agric. Vet. Sci. 8, 80–83. doi:10.9790/2380-08218083

Kurzgesagt, (2015). The fermi paradox — where are all the aliens? Available at: https://youtu.be/8ELpzmNeS4M (Accessed October 5, 2020).

Langin, K. M. (2017). Tell me a story! A plea for more compelling conference presentations. The Condor 119, 321–326. doi:10.1650/CONDOR-16-209.1

Liang, X., Su, L. Y.-F., Yeo, S. K., Scheufele, D. A., Brossard, D., Xenos, M., et al. (2014). Building buzz. Journalism Mass Commun. Q. 91 (4), 772–791. doi:10.1177/1077699014550092

Lobovikov, M., Schoene, D., and Yping, L. (2012). Bamboo in climate change and rural livelihoods. Mitig Adapt Strateg. Glob. Change 17 (3), 261–276. doi:10.1007/s11027-011-9324-8

Louie’s Tutorials (2018). How to create youtube subtitles in multiple languages for free! : YouTube Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nITNC9TDLUI (Accessed July 11, 2020).

Luc, J. G. Y., Archer, M. A., Arora, R. C., Bender, E. M., Blitz, A., Cooke, D. T., et al. (2020). Does tweeting improve citations? One-year results from the TSSMN prospective randomized trial. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 111 (1), 296–300. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.athoracsur.2020.04.065.

Martinez-Conde, S. (2016). Has contemporary academia outgrown the carl sagan effect?. J. Neurosci. 36 (7), 2077–2082. doi:10.1523/jneurosci.0086-16.2016

Maynard, A. D. (2021). How to succeed as an academic on YouTube. Front. Commun. 5 (130). doi:10.3389/fcomm.2020.572181

McCammon, L. (2014). Rethinking the flipped classroom pitch. YouTube Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s0ECkz8z2pU (Accessed July 7, 2020).

McKee, K. (2020). Science video tutorials: editing essentials. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLZWbXKooxgLB4CL0yV3dz8YOKFrCCRstC (Accessed September 23, 2020).

Menezes, S. (2018). Science training for journalists: an essential tool in the post-specialist era of journalism. Front. Commun. 3 (4). doi:10.3389/fcomm.2018.00004

Meyers, M. A. (1995). Glen W. Hartman Lecture. Science, creativity, and serendipity. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol 165 (4), 755–764. doi:10.2214/ajr.165.4.7676963

Myers, H. E. (1948). Guide for the preparation of slides and the use of projection equipment for the annual meetings of the society. Agron.j. 40 (12), 1141–1142. doi:10.2134/agronj1948.00021962004000120013x

National Academies of Sciences (2017). Communicating science effectively: a research agenda. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and medicine.

Nisbet, M. C., and Scheufele, D. A. (2009). What's next for science communication? Promising directions and lingering distractions. Am. J. Bot. 96 (10), 1767–1778. doi:10.3732/ajb.0900041

Pérez, M. R., Maogong, Z., Belcher, B., Chen, X., Maoyi, F., and Jinzhong, X. (1999). The role of bamboo plantations in rural development: the case of Anji County, Zhejiang, China. World Development 27 (1), 101–114. doi:10.1016/s0305-750x(98)00119-3

Phillips, J. D. (2009). Soils as extended composite phenotypes. Geoderma 149 (1-2), 143–151. doi:10.1016/j.geoderma.2008.11.028

Poliakoff, E., and Webb, T. L. (2007). What factors predict scientists' intentions to participate in public engagement of science activities?. Sci. Commun. 29 (2), 242. doi:10.1177/1075547007308009

Reif, A., Kneisel, T., Schäfer, M., and Taddicken, M. (2020). Why are scientific experts perceived as trustworthy? Emotional assessment within TV and YouTube videos. MaC 8 (1), 191–205. doi:10.17645/mac.v8i1.2536

Reynolds, G. (2008). Presentation Zen: simple ideas on presentation design and delivery. Berkeley, CA: New Rider.

Royal Society, (1985). The public understanding of science. The bodmer report. London, United Kingdom: Royal Society. Available at: https://royalsociety.org/∼/media/Royal_Society_Content/policy/publications/1985/10700.pdf (Accessed July 17, 2020).

Sand-Jensen, K. (2007). How to write consistently boring scientific literature. Oikos 116 (5), 723–727. doi:10.1111/j.2007.0030-1299.15674.x10.1111/j.0030-1299.2007.15674.x

Shepard, E. (1987). The magic lantern slide in entertainment and education, 1860-1920. Hist. Photography 11, 91–108. doi:10.1080/03087298.1987.10443777

Simis, M. J., Madden, H., Cacciatore, M. A., and Yeo, S. K. (2016). The lure of rationality: why does the deficit model persist in science communication?. Public Underst Sci. 25 (4), 400–414. doi:10.1177/0963662516629749

Smith, A. A. (2020). Broadcasting ourselves: opportunities for researchers to share their work through online video. Front. Environ. Sci. 8 (150). doi:10.3389/fenvs.2020.00150

Smith, A. A. (2018). YouTube your science. Nature 556 (7701), 397–398. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/d41586-018-04606-2. doi:10.1038/d41586-018-04606-2

Soderstrom, T. R., and Calderon, C. E. (1979). A commentary on the bamboos (poaceae: bambusoideae). Biotropica 11, 161–172. doi:10.2307/2388036

TechSmith, (2020). Video viewer habits, trends, and statistics you need to know. How to create instructional and informational videos that get watched. Available at: https://assets.techsmith.com/Docs/TechSmith-Video-Viewer-Habits-Trends-Stats.pdf (Accessed September 23, 2020).

Thaler, A. D., and Shiffman, D. (2015). Fish tales: combating fake science in popular media. Ocean Coastal Management 115, 88–91. doi:10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2015.04.005

Tokojima Machado, D. F., de Siqueira, A. F., and Gitahy, L. (2020). Natural stings: selling distrust about vaccines on Brazilian YouTube. Front. Commun. 5 (91). doi:10.3389/fcomm.2020.577941

Turney, J. (1998). To know science is to love it? Observations from public understanding of science research. Available at: https://communicatingastronomy.org/old/repository/guides/toknowscience.pdf (Accessed July 15, 2020).

Varner, J. (2014). Scientific outreach: toward effective public engagement with biological science. Bioscience 64 (4), 333–340. doi:10.1093/biosci/biu021

Velarde, O. (2019). Before PowerPoint: the evolution of presentations. Available at: https://visme.co/blog/evolution-of-presentations/ (Accessed July 5, 2020).

Welbourne, D. J., and Grant, W. J. (2016). Science communication on YouTube: factors that affect channel and video popularity. Public Underst Sci. 25 (6), 706–718. doi:10.1177/0963662515572068

Wheelwright, N. T. (2014). Plea from another symposium goer. Front. Ecol. Environ. 12 (2), 98–99. doi:10.1890/14.Wb.002

Wiessner, P., and Tumu, A. (2013). BeyondBilas: the Enga take anda. Oceania 83 (3), 265–280. doi:10.1002/ocea.5031

Wilcox, C. (2012). Guest editorial. It’s time to e-volve: taking responsibility for science communication in a digital age. Biol. Bull 222 (2), 85–87. doi:10.1086/BBLv222n2p85

You Tube Creators, (2017). Connect with your audience - featuring nick uhas. YouTube. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zBWGznmxwTg (Accessed July 15, 2020).

You Tube Creators, (2019). YouTube comments: replying, filtering and moderating. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=T8iFv4oo8Vw (Accessed July 15, 2020).

Keywords: science communication, public understanding of science, YouTube, science engagement, visual communication, story telling, knowledge deficit model, do-it-yourself video making, social media

Citation: Brennan EB (2021) Why Should Scientists be on YouTube? It’s all About Bamboo, Oil and Ice Cream. Front. Commun. 6:586297. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2021.586297

Received: 22 July 2020; Accepted: 08 February 2021;

Published: 29 April 2021.

Edited by:

Asheley R. Landrum, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, TX, United StatesReviewed by:

Lê Nguyên Hoang, École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne, SwitzerlandCopyright © 2021 Brennan. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Eric B. Brennan, ZXJpYy5icmVubmFuQHVzZGEuZ292

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.