- Department of Psychology, Adler University, Chicago, IL, United States

Despite increases in technical capacities for communication, contemporary society struggles with a persistent inability to effectively engage in collective action around a growing number of existential challenges manifesting in local, national, and global contexts. Confronted with environmental deterioration, economic disruptions, wars, and civil unrest, we are challenged to engage in coherent conversations that could lead to collective action, based on a shared understanding. Instead, we are enmeshed in polarized narratives, competing agendas, and emotional conflict. The uneven response to the global COVID-19 pandemic is but the most recent example of this lack of unity. As we seek to find our way in this increasingly complex social landscape, one of the best potential sources for learning about social systems and communication in conflict has gone largely unexamined. For nearly two decades, Military veterans of many nations have struggled while returning from wartime service in Afghanistan and Iraq. Despite best efforts to welcome these service members home and provide access to educational and health benefits, many of them report a difficulty in relating to fellow citizens and institutions upon their return. One indicator of this sense of alienation is the growing number of suicides among this population, now exceeding the number of casualties of combat service itself. Thwarted ability to communicate with others outside of the military and veterans community, and therefore participate in post-service social life, is increasingly recognized as a significant risk factor for suicide. It has never been easy for military veterans to talk about combat experiences. However, the levels of social isolation we are seeing now points toward a deeper and more systemic issue that is not necessarily connected to specific experiences of combat trauma, but instead rooted in real or perceived cultural and moral misalignments associated with difficult experiences in both service and post-serve transition. The longer term effects of thwarted communication and social isolation of veterans, or the feeling of not fitting in can lead to further damage to the underlying moral structures, manifesting as moral conflict (Pearce and Littlejohn, 1997) or moral injuries (Shay, 2014). These moral injuries may include perceived personal failings or culpability based on specific combat experiences, or more generally, a sense of futility in the political limitations of military missions, or perceived betrayals of trust by those in authority. Additionally, stressors and misalignments in the transition process around homecoming are likely as much of a factor as combat experience in creating moral injuries. Many veterans point to a lack of shared values and principles among citizens, and within social institutions and media, as one reason for the difficulty of post-service reintegration. Moral injuries in this sense have further existential implications, with important (but often unheard) messages for our entire society. These are not simple issues that can be addressed by our current array of social work or clinical interventions, or by altering narratives and messages. Rather, they demand a full and interdisciplinary engagement in collective assessment and meaning-making at the society level. As a way of inviting communication scholars into this conversation, I present several models drawn from the Coordinated Management of Meaning (CMM) Theory (Pearce, 2007) to look at the way that moral conflict and moral injuries are made or socially constructed in misaligned communication between returning service members and families, institutions, and others at both the population level and in community settings. Mental health implications are drawn Adlerian psychology, a body of psychological theory that is intersubjectively oriented, and shares a relational or social constructionist orientation with CMM. I then discuss the significance of these intersections in communication and mental health theory and practice, and implications for looking more closely at social connections and communication as key components of well-being and coherence.

Role of Veterans Experiences in Moral Conflict and Public Discourse

At the time of this writing, the United States is undergoing significant social challenges stemming from a highly partisan election year, the COVID-19 pandemic, and racial tensions around community policing and related symbology—complicated by demonstrations that are mostly peaceful but also in many cases include destructive attacks on commercial and government infrastructure, and public monuments. All of these phenomena are indicative of complex underlying communication issues, or wicked problems, that are not simply defined or easily resolved. It is increasingly apparent that the conventional model of communication as crafting and delivering messages is no longer up to the task of creating space for shared understanding and action. We are instead faced with a communication landscape in which competing narratives are doing battle for primacy in defining a prevailing social reality that is no longer determined exclusively by a shared sense of truth and factual evidence (Buechner et al., 2018). At the heart of these social tensions lies a phenomenon described by communication scholars Stephen Littlejohn and Barnett Pearce as moral conflict (Pearce and Littlejohn, 1997). While the moral conflicts in our society around race, politics, gender and other differences appear intractable, at the interpersonal level there remains space for connection and finding common ground. We could gain much needed insight into the nature of healing such rifts by looking at the growing body of literature around moral injury experienced by military service members in the nearly two decades of the global war on terror in Iraq and Afghanistan (Shay, 2014). Up to this point, the broader society has not had access to much of what has been learned from the experiences of these veterans, given longstanding barriers of culture and communication between the military and other elements of civil society. This gap of knowledge is not only unfortunate, it is potentially dangerous, depriving us of essential knowledge about the true nature of conflict, and the thin line between war and peace.

Taking a communication perspective of the experiences of the military, and the suffering of veterans and military families, has the potential to reveal important insights in the way that communication is engaged to “construct realities that allow wars to continue…or uncover important contributions to peace-making” (Parcell and Webb, 2015, p. 14). This also opens space to explore the essential healing capacity of truly inclusive community, as defined in Adlerian psychology as community feeling or “the individual's sense of feeling at home in the world at large, and responsible for the welfare of people in general” (Mosak and Maniacci, 1999, p. 113). As an expansion of the communication perspective, the Coordinated Management of Meaning (CMM) theory within the field of communication studies provides a range of heuristic tools, such as the hierarchy model, which allow us to consider communication at various levels of abstraction, including both content and relationship (Pearce, 2007, p. 141). Stated differently, the CMM hierarchy model provides a taxonomy of contextual forces with which to analyze ways that episodes of communication are shaped by historical, cultural and other relational factors, beyond the content of the message. Practically speaking, this type of multi-disciplinary social constructionist approach to examining the stories of moral injuries experienced by military service members can help us gain deeper awareness of our current systems of communication, leading to a better understanding of why they are not creating the desired results.

While it is true that many citizens in contemporary America have strong feelings about what is going on in our economic, political, and judicial institutions, most have not had the experience of being fully engaged as participating citizens with a personal stake in the enactment and embodiment of their underlying values and principles. On the other hand, American veterans (of all races, creeds, and genders) have a unique relationship with both the current realities of the country, and the aspirational ideals and principles upon which it was founded. This relationship is in many cases grounded in personal commitment and sensitive to moral complexity, as profoundly illustrated by this excerpt from an online opinion piece by Jeremy Butler, the current Chief Executive Officer of the Iraq-Afghanistan Veterans of America, titled “Why I Am Angry:”

There is anger at how quickly so many try to simplify the rage that exploded across the country into an opportunity to blame an individual, or a political party, or a protest movement, or to shift the discussion away from what this is really all about … love of country and patriotism don't mean unconditional loyalty. Dedication to service does not mean blind servitude. It means acknowledging that we live in a deeply flawed country while also working hard to make it better… I do say that I love America. And because I do, I call on Americans to use these tragic times to recognize America for what it is: a flawed country, suffering from its own original sin, founded on the highest ideals of freedom and liberty but which we have not yet achieved. And then commit to working to achieve them, in whatever capacity you are able—for every one of us, for all our communities, and for the sake of the America that we are meant to be (Butler, 2020).

Among other things, this perspective addresses the existence of dualities, or multiple realities, and recognizes that each of these have their own validity - while are at the same time being able to see how these competing or alternative realities are exaggerated and manipulated by polarized political narratives and identities. While acknowledging that both sides of the issue do indeed have capacity to provoke anger, taking the perspective of both/and serves as an invitation for all sides to make something positive together. Most importantly, this is an example of a cosmopolitan sensibility or “social eloquence” (Pearce, 1989, p. 169) which speaks to the potential to create a new understanding among presently divided elements of society by re-imagining our public dialogue about potentially divisive issues. This type of eloquence shifts our attention to coordination, or the way we communicate about things that matter most to us, and away from the filters of coherence that shape the way we respond to content of messages. This shift further serves to open a space of expanded awareness of the multi-dimensional moral hierarchy underlying the way we communicate about these issues (Haidt, 2012).

Moral Conflict and Mental Health

There are good reasons that we should turn to the experience of military service members in our efforts to make sense of the moral dynamics and complexities involved in our current polarized social context. Above all else, members of the military service are bound together by a sense of honor and loyalty to each other, and dedication to a higher purpose than self. This sense of obligation, rightness of action, and commitment or duty is a deeply embodied force within these communities, acting as a moral order or “moral logical force” which determines a “common sense” of how to act into given situations (Penman and Jensen, 2019, p. 41). When failures of purpose and intention occur in the face of such deeply-held personal and ethical commitments, the resulting sense of failure or betrayal at the individual level has great potential for harm to the individual psyche. At the collective level, such failures (or perceived failures) also have implications for alerting us to moral conflicts or inconsistencies at the collective or society level (Mosak and Maniacci, 1999, p. 6). It is therefore incumbent of the society in whose name these individuals are serving to engage in public discourse to listen to these experiences, take heed, learn from them, and consider their deeper implications. It is not only the right thing to do for them, but also strengthens the social fabric, and ultimately, in keeping with Adler's theory of social feeling (Gemeinschaftsgefuhl), enhances the mental health of individuals within the society.

The growing prevalence of moral injuries among members of the military may also be telling us something about an increasingly urgent need to pay more attention to certain other aspects of our civic interactions and public discourse. One immediate example in the COVID-19 era is the support of our front-line health workers and other first responders (Nash, 2020). For example, when slogans appear in the media such as “we're all in this together” and the reality on the street reflects an apparent disregard for sanitation, social distancing, and mask-wearing, the cognitive dissonance and irony is most keenly apparent to those most closely involved. This type of cognitive dissonance, or lack of a shared sense of responsibility, has long been reported by returning combat veterans, particularly those who return to higher education after service (Buechner, 2014).

While many universities have included student veteran support programs to help ease the cultural barriers for veterans coming to higher education, there are few examples of deliberate engagement with the experience of veterans as a part of academic study, or public discourse on campus. The Military Psychology program at Adler University offers one example of this type of military-civilian dialogue being enacted in a multi-disciplinary way, using conceptual models of Adlerian (social systems) psychology along with other heuristic perspectives-including phenomenology and CMM-to study the full range of the military and veterans' culture and experience (Kent and Buechner, 2019). The mixed cohort in this course of study includes veterans, their family members, and professional practitioners, with the result of creating dialogic possibilities about both veterans' experiences and prevailing social issues that are not commonly available in most social or academic settings. Additionally, these conversations are reflexive in the nature, in the sense that students are encouraged to draw upon their own feelings and experiences in context of the phenomena under study (Rascon and Littlejohn, 2017, p. 21). The result of this approach has been an expanded awareness of the social justice implications of veterans' experiences, increased attunement with the social and mental health implications of moral injury, and the expansion of “military cultural competence” as a way of enabling deeper conversations about the difficulties of the transition process for many veterans and their families (Troiani and Buechner, 2016, p. 118).

Metaphorical Warfare

When considering the potential lessons to be learned from listening to combat veterans, it is significant to note that the dominant metaphors, or mental models, we use to communicate about many social phenomena are drawn from the language of war and conflict (Buechner et al., 2018). Some examples include declaring war on COVID-19 or fighting crime in our communities. These metaphors have also crept into our social and political discourse, which, among other things, demonizes the opposition and makes compromise and negotiation much more difficult (Pearce and Littlejohn, 1997). On one level, the metaphors of warfare may not always be the most appropriate, productive, or generative way to view social institutions and processes. On another, they have potential to subconsciously influence our perceptions and shape our responses. As another way of stating this, the metaphors we use in conceptualizing social phenomena have power, and once established, are often enacted outside of our conscious awareness (Lakoff and Johnson, 2003). In particular, the metaphor of argument as war shapes our engagement in social interaction, often in unproductive ways (p. 5). When outcomes are defined in terms of winning and losing, there is little space in between for collaboratively creating something new. In a similar way, the metaphor of mental health as pathology results in certain ways of talking about the way we help veterans to deal with the impact of war on their psyche and worldview (Ruesch and Bateson, 1951). This realization invites us to the question of what we are making in conversations with and about veterans that are colored by these metaphors, and to consider how we can shift conversations—and perhaps also the underlying metaphors—to make better social realities (Pearce, 2007).

Co-constructing Alternatives

Looking at this situation from a social constructionist communication lens suggests some further ways that the lived experiences and stories of veterans in the post-9–11 world might hold valuable lessons for social change, including a re-conceptualization of the ways we think about conflict and assess and provide mental health support. This conversation is framed in an interdisciplinary context that draws upon literature of communication, mental health, leadership, and moral philosophy, centered around the phenomenon of moral injury as a disruption of deeply held values, beliefs, and frames of reference. Several of the working models of CMM theory (Pearce, 2007) will be used as heuristic tools, or metaphors for understanding the communication dynamics that underlie our perceptions of reality. We end with some implications for the use of CMM as a practical theory to help co-create more robust and inclusive meaning schemas that can assist with the identification and healing of moral injuries in our society, as well as the community of veterans and their families.

Marginalization: Cultural Barriers and Unheard Stories

Many of our contemporary social problems begin with the marginalization of some part of the population, often based on identity (Oliver, 2001; Dempsey and Brafman, 2017). Veterans, as a subset of the population, can be seen as a marginalized group in and of themselves, but as individuals they span other identities as well. This intersectionality may include differences in race, gender, age, religious belief, and political or social ideology, each of which may carry some form of lived or historical trauma (Menakem, 2017). Within the military community, these and other areas of difference are minimized to some degree by the adoption of commonly-shared values, practices, characteristics and language common to the services. One of the unifying forces among military and veterans is the notion of service to others, often at the cost of personal sacrifice. This sense of service can apply to family members as well as the service members themselves. Outside of the bounds of the military culture, many service members and veterans do not perceive similar demands and commitments being required of fellow citizens. They have also come to believe that others outside of their own community cannot or will not understand their experiences. This sense of separation has become reified over time in the form of a military-civilian gap of understanding between veterans who have served, and civilians who have not. This social division has been further reinforced by popular stereotypes and media portrayals of veterans as either heroes, victims, or perpetrators—none of which capture the complexity and essence of the veteran identity. Despite good intentions and a great deal of mutual respect, the real or perceived gap of cultural values and lived experience between veterans and civilians underlies much of the divide which has been growing since the World War II era in America. As a result of this gap, veterans' stories are not being heard, and potential for both individual and collective understanding and healing through storytelling is being lost.

Stigma, Secrecy, and Social Ambiguity

In the area of mental health, there is also a similar type of forced separation, which works on at least two levels to thwart communication with veterans about their wartime experiences. First, discussion of troubling experiences in therapy is protected by client-patient confidentiality. Secondly, many veterans have learned to not trust or rely on mental health professionals. This distrust, or lack of identification, is grounded in the values of the warrior culture, in which veterans tend to see themselves as strong and capable protectors and defenders. The language of clinical psychology, on the other hand, is mostly framed in pathology and deficit thinking, and therefore antithetical to the essences of warrior self and identity (Buechner, 2014).

Another barrier is the lack of clarity in most community or social settings as to whom a veteran might go to for the kind of conversations that are needed to sort things out. Within the service, specialized functions, hierarchies, and roles are clearly articulated. For enlisted veterans, the first resort when in doubt is to seek out the counsel of a seasoned Sergeant or Chief Petty Officer. There are few, if any, civilian counterparts to this role, which acts as a mediating force in offering guidance and interpreting right from wrong in morally ambiguous or difficult situations. Likewise, matters pertaining to ethical issues may be brought to an Inspector General, and moral or spiritual matters discussed in confidence with a Chaplain. Once a veteran is separated from these support structures and authority figures, there are few venues within which their stories–particularly those potentially involving moral conflict–can be told, and advice received.

Beyond Cognition Toward Meaning-Making

As noted earlier, most clinical conversations are also bounded by professional standards of confidentiality, which can impede openness in sharing these stories with others in the social context, which might otherwise normalize the experiences themselves (Ruesch and Bateson, 1951, P. 80), and allow the veteran to feel more in tune with significant others, including family and community. When confronted with problematic or disturbing lived experiences outside of the familiar structure of the military environment, a veteran must choose between dealing with it alone, finding peer support, or seeking mental health counseling. If the latter course is chosen, more often than not the counseling offered is with a government-employed psychologist or social worker. There are several additional barriers to communication in this scenario. As noted earlier, mental health counseling or therapy is not a recognized part of the military culture. Most therapies approved for use by the government are cognitive behavioral therapies (CBT) which address desensitization or management of symptoms attributed to stressful events. These types of therapies, if strictly applied, do not necessarily assist with making meaning of troubling events, and the stories that veterans have subsequently constructed about them. Therefore, if a form of moral injury is the underlying issue, the therapies being offered may not be appropriate or helpful, and might even be harmful (Brennan and O'Reilly, 2017, p. 191). This is particularly the case with prolonged exposure, which forces the veteran to re-visit a troubling experience without giving them additional insights on how to move beyond it. This type of focus on past trauma instead of looking forward has the effect of reinforcing Freud's notion of “acting out” rather than “working through” (Oliver, 2001, p. 76). Working through issues has more communicative complexity and potential, often leading to new realizations and possibilities. Acting out, along with the numbing effect of many psychotropic medications, can instead lead to a deadening, and away from hope and connections. As noted earlier, clinical conversations are most often couched in the “language of pathology” or the abnormal (Ruesch and Bateson, 1951, p. 70) which can further contribute to feelings of shame that might be associated with the experience. This, in turn, can color the veterans' view of their current identity, social role, and communicative relationships. If a veteran's identity as a strong warrior and protector is damaged by trauma or moral injury, and he or she no longer feels like a productive member of society, the results can be deadly. Research into causal factors of suicide among veterans has moved beyond the internalized concept of suicidal ideations, which veterans are almost universally disinclined to acknowledge (Brennan and O'Reilly, 2017, p. 190) toward interpersonal relationships. The “interpersonal theory” of suicide, for example, considers “thwarted belongingness” and “perceived burdensomeness” as two communication-related factors that predict suicide risk (Van Orden et al., 2010, p. 581). The shift in metaphor from the commonly-held view of suicide as a product of ideations toward a failing of social connectedness and communication is a significant departure from past practice. Interventions designed to affect the former have failed to make an impact in the numbers of suicide among veterans. As more data becomes available on the community contexts in which suicide by veterans takes place, through community based studies of suicide by veterans1, it is expected that strategies to change the qualities of communicative engagement—particularly during transition–will become more apparent.

The Spiritual Dimension

Space for talking about troubling experiences without the stigma of accessing clinical mental health services can be provided through spiritual or pastoral counseling, but this can be problematic for veterans who do not consider themselves to be aligned with a particular religious faith. In the military and US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) contexts, this gap is bridged by the chaplaincy, which is a spiritually-based counseling service that ministers to all, without regards to specific faith groups or religious denominations. Research conducted in the communicative roles played by military and VA chaplains suggest that, in addition to providing spiritual support, chaplains can often facilitate social connections and the development of qualities of psychological resilience (Cramer et al., 2015). One of the chaplains quoted in this study described the phenomenon of getting veterans to open up about troubling experiences as removing spiritual blockages between stories of the past and future:

If you have guilt, you may be blocked from looking into the past. If you have fear, you might be blocked from walking into the future. My role as a chaplain is to create a passage through time so they can go back to their good memories, learn from their bad memories, and be able to have a vision of their future—to set goals, and to be able to be in the moment as well (Cramer et al., 2015, p. 92).

Unless a veteran is a part of a faith community, or open to speaking with a pastor or chaplain, they may not have the context to identify the moral or spiritual basis behind experiences that may be troubling them. In the absence of professional mental health or pastoral counseling, veterans struggling with the impact of problematic or disorienting experiences may find themselves with few perceived options to communicate about these with others outside of their own peer group. While peers can offer the solace of being able to talk about things that may be considered off-limits with non-veterans, in most cases they lack skills to recognize and address problematic aspects of stories, which in any case may not always be complete or accurate. It also does not solve the matter of isolation from the broader society. Indeed, it may reinforce the notion of being disconnected, misunderstood, and marginalized.

Moral Injury and Moral Healing

For many of the reasons previously described, many veterans are rejecting the notion that their re-adjustment problems after the service are the result of a mental illness, or Post-traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)–especially in light of changes to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) which more tightly defines PTSD as stemming from embodied, existential fear (Jinkerson and Buechner, 2016). PTSD itself has become something of a cultural icon in the public mind as being associated with the military and veterans experience, even though it is in itself a social construct (Walker, 2016). At the same time, veterans are becoming more aware of the construct of moral injury, and are resonating with it–even though there is not yet full agreement on how to address it (Evans et al., 2020). In the interim, there is a growing body of cross-disciplinary knowledge about the phenomenon of moral injury that is being applied by counselors, coaches, and other mental health advisors to engage with veterans in a process of co-inquiry about possible moral injuries, and collectively imagining ways to respond to them. In this article, I propose further development of inter-disciplinary approaches to understanding and addressing moral injury, grounded in social systems theory, moral philosophy, human development and neurobiology, and framed by CMM as a practical theory of social construction in communication. Such an approach envisions the collective work of rebuilding a damaged moral framing to create space to accommodate or re-contextualize troubling experiences which may have led to the injury. At the root of such approaches is an increased awareness of the social construction viewpoint, in which the experience of reality is based upon certain co-constructed or agreed-upon understandings of individual and collective identity and social responsibility. Such approaches include, but are not limited to, Transformative Learning theory, Moral Foundations theory, CMM and Circular Questioning, and Adlerian psychology (Kent and Buechner, 2019).

Moral Foundations and Social Engagement

While current studies of moral injury among veterans has been largely undertaken from within the context of mental health, it has been understood by scholars in the field that moral injury is not just a question of psychology, but also has literary, philosophical and theological elements (Shay, 2014). Yet, at least in the beginning, the emphasis in studying moral injury in the United States has focused more on the psychological dimension of the phenomenon, or the “injury” in moral injury (Molendijk, 2018, p. 7). To gain an understanding of the moral dimension of moral injury, Jonathan Haidt's moral foundations theory has been used as a way of shifting attention to what is injured in moral injury as a way of considering multiple dimensions of moral forces in play. However, this can be problematic, in the sense that moral foundations are not empirical absolutes and the process of injury is a dynamic process and not a fixed quality (Jensen et al., unpublished manuscript). By taking a communication perspective of moral injury that is grounded in CMM and social construction, we can overcome these complications by paying more attention to the ways that moral injuries are made in communication, and the underlying moral conflicts that are in play (Pearce and Littlejohn, 1997).

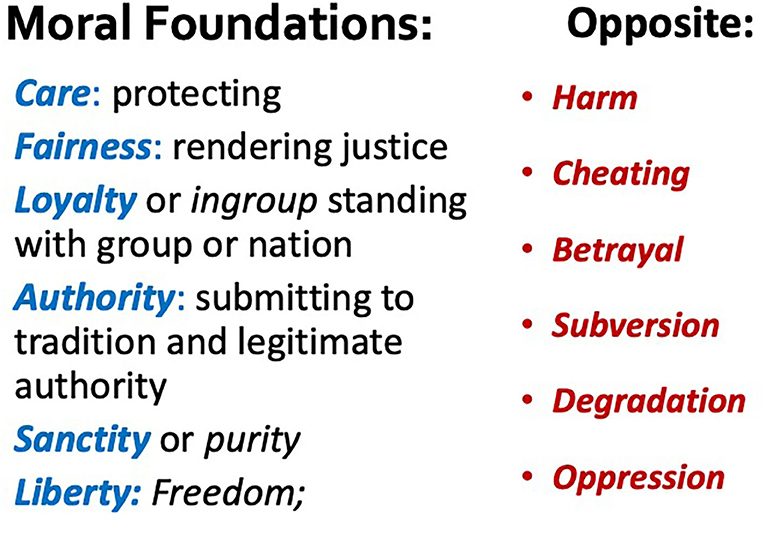

Jonathan Haidt's work in the area of moral foundations theory adds to our understanding of the multiple dimensions of ways that moral values can come into conflict, often outside of our conscious awareness. As illustrated in Figure 1 moral foundations theory defines six pillars of moral values: care, fairness, loyalty, authority, sanctity and liberty (Haidt, 2012). Moral foundations theory also differentiates between moral values that pertain to individual vs. collective well-being, using a variety of examples from the natural world to illustrate how these concepts operate. When one considers the types of qualities and principles that are inculcated in military service members through training and experience, one can readily see that military culture has a more collectivist orientation than that shared by the broader American society. This manifests in specific standards of conduct, such as never leaving a comrade behind on the battlefield, more general ideologies such as service over self, and the upholding of duty, honor, courage, and loyalty as universal values (Buechner, 2014). These values touch on each of the six foundational moral pillars—either overtly or tacitly. On the other hand, contemporary American society (which includes both liberal and conservative viewpoints) tends to intersect in only the first two of the moral pillars, care (vs. harm) and fairness (vs. cheating) and is more geared toward individual rights as opposed to collective well-being (Haidt, 2012). While military veterans have come to value loyalty, respect authority, gravitate toward purity and see themselves as defenders of liberty, upon leaving the service they do not see evidence of similar values in play in social/institutional settings or reflected in media narratives (Buechner et al., 2018). For this reason, separation from the military can be unsettling to many veterans in and of itself. Adding a perceived moral failure or betrayal encountered during service—nearly unavoidable when facing combat realities of self-preservation vs. regard for others—only compounds the sense of isolation and thwarts belongingness (Molendijk, 2018). Moral foundations theory also presents some challenges for working with episodes of moral injury, in the sense that the pillars may not always neatly define commensurate values (Jensen et al., unpublished manuscript). For example, the moral value of “caring” about a veteran's mental health might be taken as “pity,” which is something that most veterans do not want (Buechner, 2014). Also, veterans' stories, symbols and values are often tightly held resources pertaining to their identity, and therefore difficult to change—especially when the dominant metaphors (of warfare and competition) suggests they should be defended. Adding the dynamics of CMM as a “practical theory” (Barge, 2004) helps to mediate the use of moral foundations theory, providing conceptual models that may make it easier for veterans to put these resources “at risk” (Parrish-Sprowl, 2014, p. 297) and to experiment with them without fear of being considered incompetent or weak until a deeper perspective transformation can take place.

Identity, Marginalization, and Co-creation

It should also be pointed out here that the dilemma for veterans in dealing with experiences of moral conflict is not unlike the experiences of other marginalized groups in society who may feel cut off, wronged, or misunderstood (Menakem, 2017). Feminist scholar Kelly Oliver describes the phenomenon of moral recognition based on group solidarity, in which self-esteem and identity is based upon group characteristics that carry over to individuals (Oliver, 2001). Problems arise when the unique contributions of one's group are not recognized or disrespected, resulting in “shame and rage… (leading) to a sense of social or psychic death” (Oliver, 2001, p. 57.) The overtones of this statement as relating to the current unacceptable level of suicide among veterans is hard to overlook. Oliver goes on to prescribe co-creation of (new) identity as an antidote to such alienation. This is a significant statement, as co-creation can be seen as an act of moral imagination that results in something more than being forced into a binary choice between two undesirable polar opposites. This leads us to the next argument, for accomplishing this type of identity formation in social systems by re-thinking the way we enact processes of communication among groups, as re-imagined through an interdisciplinary perspective.

As the military and veteran community moves in the direction of addressing ways to work with moral injury, it is already apparent that we cannot expect licensed clinical therapists to act as moral philosophers or clergy in helping veterans to make meaning of difficult or challenging experiences involving moral conflicts. The implications for mental health seem clear, and yet organizational, institutional, or clinical solutions seem ill-suited to addressing the sense of isolation experienced by many veterans. Appealing to authority figures or social institutions is likewise generally not seen as a viable option—especially when the perceived wrongs are viewed as at least partly the result of corrupt or indifferent leaders, or a misapplied or unfair system. One critical question in healing moral injury is how to rebuild trust when it has been broken? This has been a vexing problem for combat veterans throughout history, and we are now seeing it emerge as a consequence of the constant barrage of warring narratives and counternarratives in all of our communicative media (Buechner et al., 2018).

Generative Metaphors and Moral Imagination

Returning to the earlier discussion of the role of metaphors in meaning-making, we could consider that at least part of the moral conflict experienced by veterans may be generated by a sense of misapplied or incommensurate metaphors. A challenge for communicators in healing these rifts might be described as shifting some of these dominant metaphors—or replacing them with new, more generative ones—as a way of allowing more space for imagination and co-creation. As metaphors often shape our perceptions outside of our conscious awareness, foregrounding and identifying commonly-used metaphors and their enactment in patterns of communication can be an important first step toward bridging gaps in understanding and identifying problematic misalignments of moral codes and conceptual framing. This not only has implications for the way we experience and make meaning of a phenomenon itself, but also in the way we engage with others around it (Lakoff and Johnson, 2003). As one example of this, rather than perpetuation of the argument as warfare metaphor introduced earlier, we might consider the more generative approach of “transcendent discourse” which instead consists of probing to learn more about how the other side thinks, looking more critically at our own communication, and considering new ways of thinking about the underlying issues (Pearce and Littlejohn, 1997, p. 153). In social and business settings, this might include accounting for complexity and awareness of higher levels of context from which to view outcomes, beyond a simple win-lose dynamic. An example of this would be members of an organizational work group deciding to focus on collaborating to make the organization better instead of arguing to win—shifting the dialogic goal from “being right” to “being effective” (Parrish-Sprowl, 2012, p. 19). Further evolution might be made possible by shifting or flipping the dominant metaphor from warfare altogether to something else, such as building a foundation for peace, as a way of generating other possibilities. As an example, West Point graduate Paul Chappell describes the use of the knowledge and lessons of warfare to build “peace literacy…” “much like medical doctors …become experts on disease and illness … to promote health” (Chappell, 2013, p. 18). Taking the analogy further, Chappell suggests that a deeper understanding of the patterns that cause war in the first place can help to dispel the illusions and myths (as social constructs) that perpetuate it. In this sense, turning the metaphor of war as enacting conflict to one of studying war to build capacity for peace opens space for a wider and more positive range of outcomes.

Similarly, finding alternatives to the mental health as pathology metaphor may have potential to create more acceptable forms of engagement with making meaning of difficult or challenging wartime experiences encountered by many veterans (Walker, 2016; Buechner et al., 2020). Adopting a focus for mental health as creating capacity for well-being, for example, results in a wider range of possibilities then simply eliminating or correcting specified disorders. Such a shift may well lead to opportunities for personal growth and development of veterans, as well as generating or uncovering valuable lessons for society. On one level, this may require a change in the way we communicate about mental health, and on another level, may involve a fundamental shift in the way we think about communication as a complex process by which we co-construct meaning together, and thereby, define and redefine future possibilities for creating coherence instead of discord. Such a shift in thinking about communication and mental health might involve more emphasis on building capacity for creativity and artistry to make new meaning together, and less on diagnosis and modifying cognitive processes (persuasion) to change behavior (Parrish-Sprowl, 2014).

Communication and Mental Health

Looking at the mental and social readjustment issue of returning veterans from a communicative and social constructionist lens serves two useful purposes: (1) giving us a new way to understand the role of community conversations with veterans and the way to talk with and about them as potentially healing conversations, and (2) expanding the moral frameworks within which the society looks at itself, engaging an outside perspective of returning veterans to shift attention to shared values and opportunities for exploring common ground. The second of these is likely the most difficult, but is invoked by the comments of Jeremy Butler referred to earlier. As he stated it, such a profound change is only possible if we shift our anger from the others we are being pitted against by polarized media narratives (on both sides of the conflict) and toward the forces of manipulation that are serving to divide us. Such a shift moves us toward paying further attention to the whole, and not just the parts that are, or appear to be, in conflict.

In keeping with Adler's concept of mental health as a function of social connection, we can envision that the social fabric provides a context for communication which is for the most part governed by moral and ethical codes (Ruesch and Bateson, 1951). Within this context, we also have a number of resources from which meaning is derived, including “stories, images, symbols, and institutions” sustained by practices that reflexively define and perpetuate them (Parrish-Sprowl, 2014, p. 296). These moral codes, practices and resources are shared within a culture, and in turn govern the quality of our relationships, and the coherence of meaning established within groups. We can also imagine that a moral injury is something that conflicts with or damages those moral codes. Therefore, it follows that the collective space in which we interact and share that meaning is a productive place to look when seeking to understand, analyze, or address moral injury. This leads us to further possibilities for finding new, and possibly more helpful, mental models to guide the process of analyzing the effects of moral incoherence, or rebuilding damage to the underlying moral structures.

Adler, Social Construction, and the Collective Turn in Healing Trauma

Although the term moral injury was not in common usage around the time that Alfred Adler was writing and practicing psychology, it is entirely likely that he was profoundly influenced by his own lived experience of the phenomenon, and its impact on social cohesiveness. It has long been recognized that war challenges deeply held ethical and moral values. Adler served in the German Army during World War I, and it was after this experience that he re-evaluated much of what he and his colleague, Sigmund Freud, had been teaching about the nature of psychology, and moved toward a more intersubjective and socially-grounded theory. Recent scholars of his work have referred to it as in-divisible psychology, meaning that the mental health of individual persons is inextricably linked to the quality of their engagement with the social worlds that they inhabit (Watts et al., 2004). From this point of reference, mental health itself is seen as a socially grounded, intersubjective phenomenon, and as such is neither fully individualistic nor wholly collectivistic in nature. The advent of Adlerian psychology also marks a relational turn, from focus on the cognition-based pathology of Freud toward the development of healthy engagement in social systems as the locus for mental health development. The resulting approach to therapy in the Adlerian tradition bridges between cognitive constructivist and social constructionist perspectives, with the quality of intersubjectivity itself as the focus of attention (Watts et al., 2004, p.9).

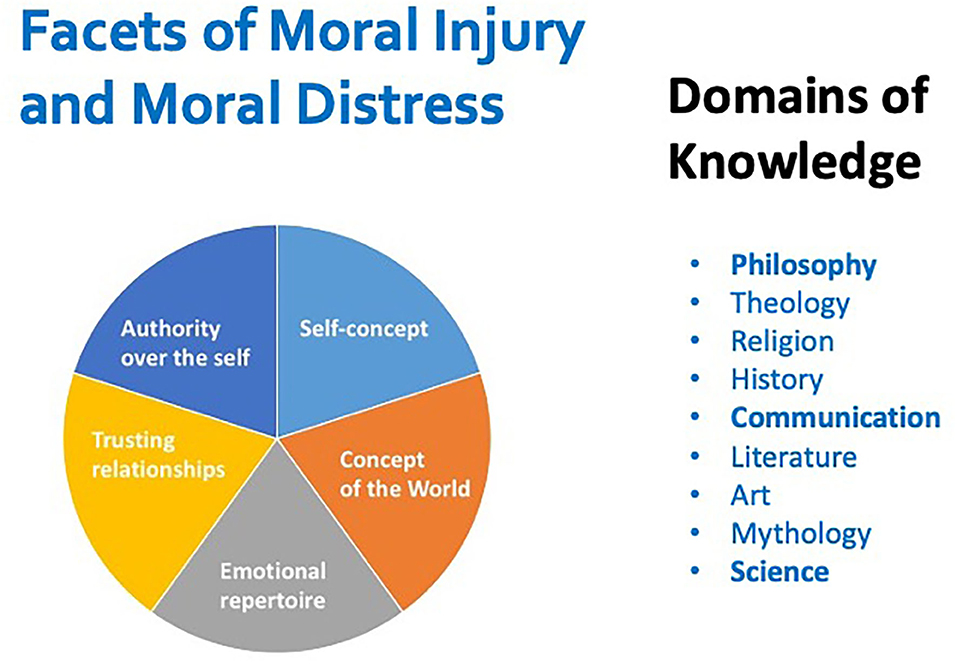

Although there has been robust discussion of moral injury, there has been a significant amount of disagreement in both military and clinical psychology communities about what it is and is not, and whether it is a form of trauma. At least part of the disagreement lies in the term moral itself, which implies the imposition of a particular set of values, and individual consequences of violating them. As is illustrated in Figure 2, the emerging view of moral injury as an interdisciplinary construct crosses several fields of study as well as facets of human experience. This includes identity and self-efficacy on the individual end of the spectrum, and worldview and relationality at the collective level (Nash, 2016). When we think of our social worlds as being constructed in communication, the need for more attention to the underlying process by which moral conflict and moral injuries are created becomes apparent. Using CMM tools and heuristics leads us toward a deeper and multi-disciplinary examination of the phenomenon of moral injury itself, and suggests the possibility of reconciliation and healing through expanding relational possibilities for “right action” (Penman and Jensen, 2019, p. 36). This may include co-constructing ways of going on that can help us to better account for moral complexity and multiple perspectives.

Within the field of psychology, Alfred Adler's turn toward an intersubjectively oriented, relational constructivist perspective is much like the shift in thinking that is invited by the social constructionist paradigm of CMM in communication, moving our attention from content to the process of what is being made in the process of communication (Watts et al., 2004; Pearce, 2007). For Adler, social feeling and individual mental health were inseparable constructs that shaped each other (Mosak and Maniacci, 1999). CMM lays out heuristic models that may be useful to identify, and change, assumptions and patterns that lead to undesirable outcomes. Like Adlerian psychology, this theory -based approach bridges the individual and the collective viewpoint, shifting focus to the underlying meaning structures. From the perspective of moral injury, it follows that an objective co-inquiry into the patterns of meaning and action that underlie an episode of perceived harm or betrayal can be a first step toward imagining and enacting other possibilities, or enlarging the moral imagination. In a practical sense, such a perspective serves to reduce the potential for individual blame or shame for actions one took, did not take, or witnessed. The ability of individuals to coherently engage in new social contexts or experiences which challenge or conflict with previously accepted norms may depend upon the acquired or developed capacity for interpreting and acting into uncertainty, or liminality by engaging the moral imagination (Buechner et al., 2020). Such a capacity is more than a matter of modifying cognitive responses, but rather is a shift of perspective or worldview (Kent and Buechner, 2019). Making such a change in perspective is not always based on empirical evidence, which can be selectively interpreted within one's already formed interpretive schemas. Instead, it may be cultivated by self-reflection (individually and in groups), the application of alternative theoretical models, and the shared development of new, more inclusive, ways of being and seeing the world. We will next consider how these interpretive schemas are embodied, and how collective engagement of moral imagination can influence them.

Neuroscience, Identity, and the Moral Imagination

There is increasing evidence from the field of neuroscience that shines light on the underlying influence of interpersonal neurobiology in the enactment of social frameworks and the formation of moral codes (Narvaez, 2014) Among other things, we now know that the moral imagination is a function of the right side of the brain, and that collectively engaging the moral imagination, or communal imagination is an important part of both personal and social evolution (Narvaez, 2014, p. 118). This suggests that including imaginal activities, including creative expression and development of other right-brain functions, should also be considered in addressing moral injury. One way to look at the particular relevance of both Adlerian psychology and CMM to addressing moral injury is to consider the creative potential of a social construction approach to addressing the underlying problem through co-construction of a more inclusive social reality. In many cultures, social problems and psychological dilemmas are resolved “respectfully, and with creativity and commitment” through the communal engagement of “moral imagination” (Narvaez, 2014, p. 118). This is to say that if our approach to resolving conflicts in a “win-lose” dynamic is failing us, then moving toward a both-and solution through co-construction of something new offers a way to transcend the apparent impasse, through co-construction of a new moral and social reality that is large enough to include the areas of previous conflict. As a social constructionist approach to mental health, Adlerian psychology engages the imagination as a way of shifting attention from a problematic experience in the past to a process of envisioning a repertoire that opens new future possibilities that are more in line with moral intention.

One aspect of the capacity for imagining better or more inclusive moral possibilities may include developing the ability to view situations from the perspective of others, or acquiring a less culturally-dependent worldview, or intercultural competency (Steen et al., 2018). This type of re-imagining and expanding moral and ethical frameworks and meaning schemas can serve as both a therapeutic strategy, and also may create opportunities for a developmental approach to prevention of moral injuries—the logic being that a worldview that is more inclusive and multi-faceted may be less subject to the emergence of moral conflicts, and therefore less susceptible to injury or damage. When moral conflicts do present themselves, we also have the ability to re-imagine them from a different moral framework, or, in the language of CMM, a “higher level of context” (Pearce, 2007, p. 147) in which the moral injury is either acceptable, or no longer seen as a conflict with the most significant moral value or values in play.

One example of this from the experience of the military and veterans is described by General Martin Dempsey, the former Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. While visiting with units operating in Afghanistan, Dempsey asked a young Army Captain how we could do things better. His reply was that military leaders needed to learn to “assess the outcome of our actions in the context of how they are understood by the local population” not just on military advantage (Dempsey and Brafman, 2017, p. 46). In his example, a military strike that cut off an insurgent supply network running through a village might create a helpful tactical short-term advantage, but the damage to the relationship with the local population would be more harmful in a strategic sense over the long term. This realization is not just an example of the application of cultural competence, but also implies a contextual and relational awareness of what we are making in communication in such situations. Acquiring this type of capacity to reflect in the moment about the multiple contexts from which an action could be viewed, and to choose the highest level of context, is an aspect of intercultural agility that is increasingly demanded by the complexity of the current military operating environment (Steen et al., 2018). This insight was one factor that led General Dempsey to a definition of leadership as “radical inclusion” or the ability to create a meaningful shared narrative that generates a sense of belonging to the largest possible group (Dempsey and Brafman, 2017, p. 68). This is a distinct departure from models of leadership that are oriented toward command and control, and exercise of authority. That view of leadership, in both military and social contexts, lacks nuance to account for moral complexity, and is very likely a source of moral injury, especially in cases where there are unintended but deadly consequences of such decisions. The value of leaders engaging in this more inclusive type of thought process in decision-making is that the resulting shift in perspective engages a wider range of perceptions in the co-creation of context around consequential decisions. This approach is more or less in line with the model of leadership embodied by Francis and Clare of Asisi in making “co-created moral relationships.2” This shift in leadership thinking has implications for both preventing moral injury, and dealing with its consequences in community settings. This is particularly true when moral injury threatens or challenges notions of identity and purpose.

Finding a new identity after service almost always presents a challenge. On one level, military service can be one of the most fulfilling things a person can do. The bonds of solidarity and friendship, even love, among fellow warriors is difficult to match in other contexts. On another level, a great number of veterans have had experiences in the service that (often for good reasons) lead them to be wary of organizations and institutions. With these conflicting logical forces in play during transition, many veterans find themselves being faced with the choice of rejecting their old identity and finding a new one, or holding onto the past identity (Buechner, 2014). Either way, the result can be a sense of liminality, being neither here nor there and not fitting in Buechner et al. (2020). The social constructionist perspective presents the opportunity to participate actively in creating a new role and identity while still retaining valued portions of service values and identity.

Practical Theory: CMM, Cosmopolitan Communication, and Storytelling

While CMM is mostly known among scholars in the communication field, it has been influential in the field of counseling as a “practical theory” which, among other things, offers a way of “joining and respect(ing) the centrality of (the experience of) others” (Barge, 2004, p. 187). One example of a CMM-informed approach to therapy, circular questioning, is a social constructionist method that has been employed in family systems work. The objective of this approach is to identify and change problematic patterns of behavior, without making judgments or fixing blame on particular individuals (Rossmann, 1985). While not yet engaged in the field of moral injury studies, the key principles of objectivity, neutrality and circularity as employed in circular questioning method (Rossmann, 1985) would likely be useful in unpacking experiences where moral injury was a result, given the demonstrated capacity of CMM to explore “moral orders and positioning” (Barge, 2004, p. 189). At this writing, circular questioning and other CMM-related concepts and models are lesser known among those presently working with the military and veteran population, although several have been introduced in the MA in Psychology with emphasis in military psychology program at Adler University in recent years (Troiani and Buechner, 2016). We will next explore some of the possibilities for working with these methods and models in situations where moral injury is present, or suspected.

Untellable Stories and Ineffable Experience

As noted earlier, military service members and veterans are often told that the rest of society—including in some cases their own family members—cannot understand some aspects of their service experience. It is also quite possible that many service members may not fully understand their own troubling or difficult experiences themselves, and therefore they never even try to express them, or if they do, may find aspects of these experiences to be ineffable (Buechner et al., 2020). This suggests a need for the creation of more appropriate spaces in the broader social context in which veterans' stories may be told and heard, and their importance absorbed into the social fabric in a mutually cathartic way. There are at least two CMM-based communication models which might have potential to map areas of division and point toward possibilities to create different results: Cosmopolitan Communication (Pearce, 1989) and the LUUUUTT (storytelling) model (Pearce, 2007). Both of these models support the more central premise of CMM as a way of looking directly “at” communication and its patterns, not “through” it (Pearce, 2007).

Culture and Inclusion

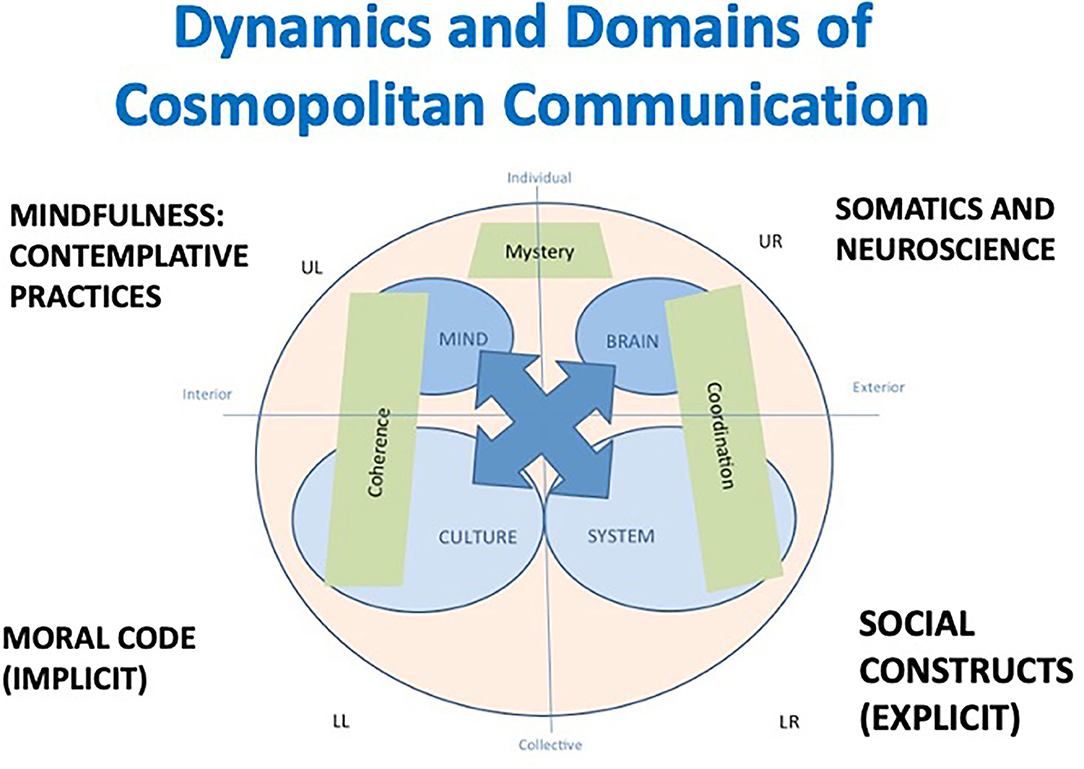

The Cosmopolitan Communication model is premised on the basis of four levels of engagement with those perceived as “others:” monocultural, ethnocentric, modernistic, or cosmopolitan (Pearce, 1989, p. 168). At the monocultural level, everyone is seen as the same. Within the military service, this way of thinking can be seen as desirable, as it supports complete and unambiguous coordination of action and coherence of meaning within the group. Moving to the next level of ethnocentric communication, others are acknowledged as different, but “outsiders” are considered as inferior, or even dangerous. In a modernistic view of communication, others are perceived as different, and it falls to us to change our thinking to accommodate that difference. Only at the fourth level, Cosmopolitan Communication, do we engage in coordinating with others in a way that respects the common humanity of the other, while also acknowledging differences. In the cosmopolitan form, communicative interactions take the form of either coherence, coordination, and Mystery, in which the latter is capitalized to denote a transcendent or emergent quality, not within the direct control of participants (Pearce, 1989, p. 169). Matoba (2013) adds to the utility of this Cosmopolitan Communication model by illustrating the dynamics of coordination and coherence across the four quadrants of the Integral theory model, encompassing the collective and individual domains, and the internal and external dimensions of human experience, respectively. With this refinement, it becomes possible to map the way coordination is achieved in the external (and empirically observable) space of systems, and coherence manifests in the cultural and spiritual domains, which are less under our awareness and control. Writing as an “unlicensed philosopher,” Jonathan Shay made much the same case for mapping moral injury across “brain, mind, society and culture” (Shay, 2010). The whole, in this case including the process itself, is substantially more than the individual parts in isolation, adding to the argument for an integrated approach to moral injury that is not situated in just one element of human experience. Figure 3 shows the working model of Cosmopolitan Communication derived from concepts drawn from sociology, neuroscience, wisdom traditions, and communication.

The potential significance of this Cosmopolitan Communication model to address moral injury is contained in at least two areas. First, it is a way to engage differences without forcing others into a predefined role (with potentially inferior status) within the dominant culture—providing recognition without invoking power differentials or feelings of oppression (Oliver, 2001, p. 9). Secondly, it offers an invitation to generative co-construction, or making something new together, that does not invoke previously problematic patterns, which Pearce describes as “transcendent eloquence” or “transcendent discourse” (Pearce, 1989). This is important because language and speech are collectively-owned, not proprietary or technical properties, and therefore not dominated by psychological processes (Jensen et al., unpublished manuscript). Inasmuch as veterans have been culturally and experientially conditioned to avoid clinical psychology, and have found many conventional therapies to be ineffective or harmful (Brennan and O'Reilly, 2017) such an approach is not only refreshing, but can help to avoid stigma and re-traumatization. This also invites the question as to whether teaching Cosmopolitan Communication skills as part of military training or transition preparation might be a useful strategy.

Prevention of Moral Injury: Cultural Competency and Leadership

Cultivating capacities for Cosmopolitan Communication among the military (including military leaders) is still in the emergent stages, but already is showing promise to reduce both internal frictions as well as the sometimes-deadly consequences of cross-cultural misinterpretation in the operational space (Steen et al., 2018). One of these capacities is development of the ability of leaders in “defusing conflicts among persons with different racial, gender, ethnic and social backgrounds, allowing the group to arrive at a shared perspective – if not agreement” (Steen et al., 2018, p. 410). This applies to working with allies, in operational settings, as well as maintaining unit integrity and capacities for independent, yet coherent, action. Military leaders, including General Stanley McChrystal, the former Commander of Special Operations forces in Iraq and Afghanistan, have recognized these qualities as essential for operating in environments that are both unfamiliar and unpredictable (McChrystal, 2015). A culturally-sensitive and developmentally-focused leadership is also seen as a defense against moral injury (Molendijk, 2018). It is also a counter to other harmful effects of what is increasingly described as “toxic leadership” in the military, which has been cited as a common underlying factor of poor unit morale, disillusionment, and failure to respond appropriately to allegations of sexual assault within the ranks.

Closing the Transition Gap

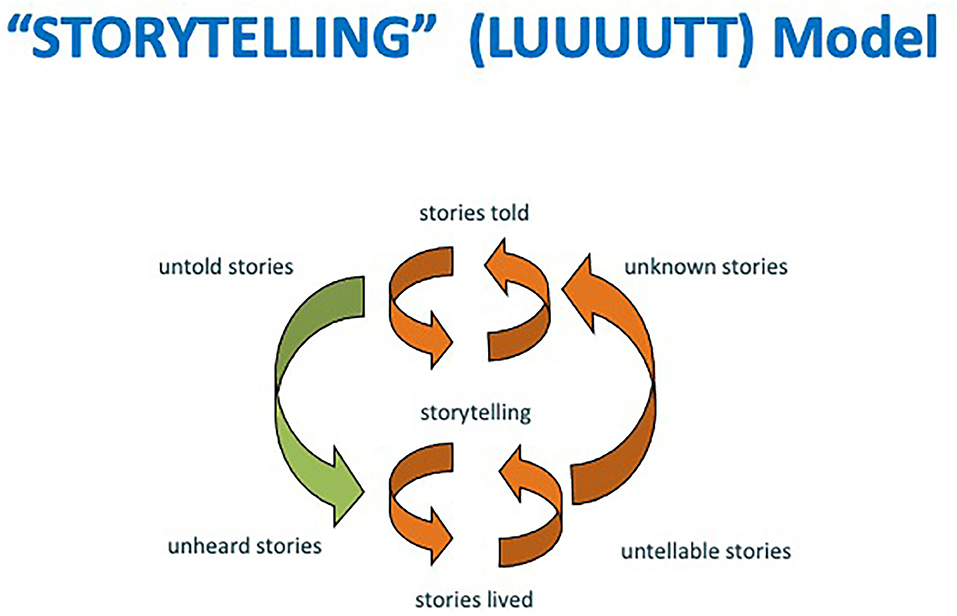

Viewed from a perspective of personal development, the acquisition of intercultural competencies and Cosmopolitan Communication skills may also support service members in their transition back to society at the end of their service. There is an acknowledged “military-civilian gap” that has evolved over time, presenting a real or perceived barrier between those who have served and those who have not (Buechner, 2014). One way to assess, and possibly overcome, the underlying causes of this gap of understanding is through use of the “Storytelling” or LUUUUTT model defined in CMM theory (Pearce, 2007), as illustrated in Figure 4. This is a systemic approach for mapping out potential blockages or discrepancies between the stories we tell ourselves, and those we tell (or cannot tell) others. Stories are mapped out in the context of storytelling as a basis for making shared meaning of lived experience (“stories lived” vs. “stories told”), with special attention to the stories that are either “unheard,” “untold,” or “untellable” (Pearce, 2007, p. 212). As one example derived from using the LUUUUTT model in working with veterans in a therapy group setting, the focus of attention on hidden power of “untold and untellable stories” as applied to a present conflict between two of the veterans in the group opened up space for exploration of formative childhood experiences related to enactment of masculine archetypes (Buechner et al., 2020). By bringing the underlying context and meanings connected with this earlier experience to the surface, the two veterans were able to not only de-fuse their current conflict, but engage in further self-reflection that enlivened and deepened connections among the entire group. Many of them subsequently reported this as a transformative experience, beyond their previous level of experience in such groups (Buechner et al., 2020). The addition of the LUUUUTT model to traditional therapy adds the critical elements of exploring otherwise unknown, untold or untellable stories, and examining them further for the meaning of why they have not been told, or have been unheard.

Applying this model at a larger scale to mapping out the stories that veterans do not or cannot tell, we can see at least part of the reason for the widening military-civilian gap of understanding. Due to social stratifications in both virtual and actual communities, some types of stories, or categories of stories, have been rendered “untellable.” Some of these stratifications are those mentioned earlier: contextual misalignments, professional ethics, and real and perceived cultural differences. Added to these barriers, veterans are also impeded from telling some kinds of stories through the fear of guilt or shame associated with incidents of moral injury, which can include real or perceived acts of omission or commission. While the facts or elements of such a story may be uncompelling or unremarkable to most citizens, the higher ethical and moral standards to which veterans often hold themselves may raise the bar of personal disclosure to an unattainable level. Another barrier to storytelling is the perception common among veterans that civilians would simply not understand, suggesting that storytelling would just lead to more unheard stories.

Creating a context where stories can be shared among relative “outsiders” without the normal social constraints presented here is not a simple task, but it has been shown to be possible. Writing programs, such as the one led by David Chrisinger at the University of Wisconsin, have created space where veterans are supported in writing and sharing such experiences (Chrisinger, 2016). Retreat centers which include mindful reflection as well as open space for storytelling and creative expression can also serve as catalysts for this type of communication between veterans and empathic others (Buechner et al., 2020). While these types of apparent “breakthrough” results have mostly been isolated cases up to this point, they suggest the value of further efforts by communication scholars and practitioners to help develop more widespread practices and competencies to enact these types of communication dynamics in the public space. The reflexive benefits of doing so would include more healing for veterans, and insights for the rest of us on ways that we can, as suggested by Jeremy Butler, come together in unity to better enact and embody the “highest ideals of freedom and liberty …which we have not yet achieved.”

Summary and Future Possibilities

The notion of the social construction of reality was at one time something of a fringe theory in the communication field, but over time has moved into the mainstream of academic literature and contemporary practice. Similarly, moral injury is a relatively new idea that is challenging conventional concepts and practices of mental health, as a complex construct that has roots and implications in both individual experience and in the social fabric itself.

The foregoing discussion offers some insights into why veterans have come to reject many conventional forms of mental health treatment, and also why they may not perceive viable communicative pathways in contemporary society to support their post-service reintegration. It also suggests some of the qualities of community engagement and communication that might help to open space where healing engagement and conversations can take place in ways that have not previously been possible. Such conversations may well cross conventional ideas of spiritual, mental health, or social services discourse, presently constrained by convention or perceived boundaries.

Developing and expanding capacity for these kinds of meaningful conversations between communities and military members and veterans may well be a matter of life and death. This is particularly critical during transition, when many veterans are feeling that they are in an unsupported state of liminality, no longer a part of the military yet not quite belonging anywhere else (Buechner et al., 2020). This is particularly important, as this type of transition stress is increasingly recognized as being possibly more prevalent than combat stress, which affects a relatively small number of veterans (Mobbs and Bonanno, 2018). While fewer than 10 percent of all veterans have experienced combat stress to the level of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) as rigorously defined, between 44 and 77 percent report “high levels of stress” during transition to civilian life, including “interpersonal difficulties” of various types (Mobbs and Bonnanno, p. 138). Further, the impact of “thwarted belongingness” appears to be a significant predictor of suicide risk among veterans, along with “perceived burdensomeness” and “capability for self -harm” (Van Orden et al., 2010, p. 592). The first two of these variables are directly related to the veterans' ability to communicate with others and to assume a new and valued social role after transition. Moral injury, or the damage to closely-held values and beliefs, affects both of these.

Acknowledging the presence and validity of moral injury connected to military service also calls us to a deeper awareness of the often-unexamined nature of our moral frameworks as a society, and our identities and identification with certain beliefs. CMM theory and the Cosmopolitan Communication model offer a way of looking at such beliefs from an objective or third-person perspective, offering heuristic tools that can uncover problematic communication patterns and their underlying implicit moral frameworks.

Moral injury as a concept is still relatively new and little-discussed outside of a small segment of the veterans mental health field, yet it has potential implications for application to identifying and mending other rifts in the social fabric. “Morality” has been treated as a more or less subjective quality in contemporary society; application of moral foundations theory offers a basis to further explore ways that values come into conflict. However, it is possible that application of moral foundations theory alone could generate further misalignments, misunderstandings, and conflicts by forcing the phenomenon of moral injury into a rigid set of criteria, diagnostics, and symptom definitions. A mediating theory of social construction such as offered by CMM can provide a framework within which these ideas can be examined as a complex dynamic process, rather than empirically defined as fixed qualities.

By combining insights of CMM with emerging findings from interpersonal neurobiology, we have further potential to explore and perhaps reshape our dominant metaphors, as they reflect the embodiment of our emotional as well as our rational nature into the moral fabric of our social systems. As another way of describing this, advances in neuroscience and epigenetics are telling us more about the reflexivity of experience and belief systems, and how each play a role in constructing the other. While coming to a realization of the degree to which our opinions, decisions and actions are based on emotion, we are also being faced with evidence that emotions themselves are constructed (Barrett, 2017, p. 157). Navigating this space successfully requires the capacity to maintain “emotional presence-in-the-moment” and further evolution dependent upon maintaining “a pro-social-egalitarian mindset” which is in turn reliant on a “well-functioning emotional system” (Narvaez, 2014, p. xxviii). This type of understanding of our own personal development and happiness being inextricably linked with the qualities of our social context and institutions is what Pearce (2007) described as “personal and social evolution” (p. 184). Combining these perspectives suggests further practical value in using CMM heuristics to reflect in-the-moment on the patterns that we are making in communication with others can help us come to a better understanding of our own identity and purpose, and co-construct better social realities with others in a mutually transformative process

Finding ways to communicate with veterans across cultural and experiential divides also has implications for the health of the entire society. Veterans are not the only members of contemporary society who have been—largely unintentionally—placed in a status of marginalization. Finding ways of bearing witness to this experience of being “others” in society, and creating new and more inclusive stories around that experience can lead to insights that may contribute to enlarging our notion of what it means to be a fully engaged and participating citizen. This could take the form of expanding other types of public and community service, other than the military, and using what we have learned from the experiences of war to create a more peaceful world. This might also involve taking a closer look at the labels pertaining to institutional identities and professional specializations, and replacing these with more abstract language and grammar around service, social contribution, and positive engagement. Contemporary examples include the way that firefighters and other first responders were viewed after their bravery at the World Trade Center and Pentagon on September 11, 2001, and now the ways that front-line health care and food chain workers are receiving appreciation for their sacrifices during the COVID-19 era.

It is important, as well, to make more informed and purposeful choices of the metaphors we use in shaping conversations with veterans in order to create more space for shared understanding and open more possibilities. Not only is Moral Injury a very different model from PTSD in a nosological or clinical sense, the entire worldview that accompanies it is based on different conceptualizations. More broadly, discourse around mental health is very different if we see it in terms of inviting social connectedness and well-being, or as diagnosing and fixing a brokenness or curing a pathology. Making the transition from military to civilian life is also viewed in very different terms if it is seen as the end of the only identity one knows in exchange for choosing a strange and unfamiliar one at random, or a process of carrying over character strengths and skills to “serve” in a new way. At the level of social engagement, civic leadership takes on a different character if the process is seen as a collaborative engagement in which all participants add something unique based on their talents and strengths, as opposed to a fight in which the victors wield power over the vanquished. With more veterans entering into political life, it may become evident that they see the limitations of the “politics as warfare” metaphor, and demand (and co-create) something better.

The use of many of these social constructionist theories and concepts has been explored and documented in educational settings, but broader awareness and widespread practical application has been constrained by disciplinary boundaries. There is more work to be done in adapting these models and concepts for use in other contexts to specific applications for directly addressing moral injury. While recognizing the place and value of clinically supervised and controlled therapies for acute cases where individuals are immobilized by trauma or moral injury, we should also acknowledge the potential for engaging the collective imagination in open settings (ie: local community, university, faith groups) by creating space for coming to grips with the collective stories of moral injury that veterans bring home with them—and that our first responders and health care front-line workers are living with daily.

Understanding the underlying moral conflicts that define our era—and gaining insights as to what to do about them—may be one of the most important lessons society can learn from veterans. And the process of listening to and learning from them in and of itself may ultimately be the best mental health therapy we could offer to them in return.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This paper owes a great deal to Barnett and Kim Pearce, and the Board and members of the CMM Institute for Personal and Social Evolution. In addition to the value of CMM itself for the unlocking the communication patterns behind the difficulty of post-war experience, Barnett and Kim took a personal interest in the dilemmas facing returning veterans, and have played a guiding role in the meandering process of discovery of ways that CMM can make a difference in the lives of many who continue to struggle.

Footnotes

1. ^A current and ongoing example of this is Operation Deep Dive, University of Alabama. Retrieved from https://www.americaswarriorpartnership.org/deep-dive?gclid=CjwKCAjwrKr8BRB_EiwA7eFapsS7faUNgYtuzpppH36VBziwH_nMyR4HROquJG0wrD7qFZtAdYE5keRoC72gQAvD_BwE

2. ^Dr. Pauline Albert, personal communication, July 29, 2020

References

Barrett, L. (2017). How Emotions Are Made: The Secret Life of the Brain. New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Brennan, T., and O'Reilly, F. (2017). Shooting G hosts: A U.S. Marine, a Combat Photographer, and Their Journey Back From War. New York, NY: Viking.

Buechner, B. (2014). Contextual mentoring of student veterans: a communication perspective (Doctoral dissertation), Proquest Dissertations & Theses (Publication number 3615729), Fielding Graduate University, Santa Barbara, CA, United States.

Buechner, B., Dirkx, J., Konvisser, Z., Myers, D., and Peleg-Baker, T. (2020). From liminality to communitas: the collective dimensions of transformative learning. J. Transform. Educ. 18, 87–113. doi: 10.1177/1541344619900881

Buechner, B., Van Middendorp, S., and Spann, R. (2018). Moral injury on the front lines of truth: encounters with liminal experience and the transformation of meaning. J. Schutz. Res. 10, 51–84. Retrieved from: https://www.zetabooks.com/docs/Barton-BUECHNER-Sergej-von-MIDDENDORP-Rik-SPANN_Moral-Injury-on-the-Front-Lines-of-Truth_Encounters-with-Liminal-Experience-and-the-Transformation-of-Meaning.pdf (accessed October 12, 2020).

Butler, J. (2020, June 3). Why I am Angry. ConnectingVets Blog. Retrieved from: https://www.radio.com/connectingvets/articles/iava-ceo-jeremy-butler-why-i-am-angry (accessed September 27, 2020).

Chappell, P. (2013). The Art of Waging Peace: A Strategic Approach to Improving Our Lives and the World. Westport, CT: Prospecta Press.