- 1Department of Psychology, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI, United States

- 2Department of Fisheries and Wildlife, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI, United States

Trust, defined as a willingness of one entity (e. g., stakeholders) to be vulnerable to the discretionary actions of another (e.g., a wildlife management agencies), is a key attribute of effective environmental management. A lack of clarity about which factors matter most in developing and sustaining trust creates an impediment to good governance. Our objective was to derive a set of antecedents of trust from research reported in peer-reviewed literature in natural resource and environmental science, management and policy domains. We conducted a meta-analysis of the relationships between trust and seven antecedents: reputation, communication, shared norms, and values, cooperation/support, negative past behaviors, satisfaction with/quality of services, and fairness. We also examined whether relationships between antecedents and trust differ depending on whether the target of trust is a specific person or the organization as an entity, as well as whether the relationship with the referent of trust is horizontal (i.e., between natural resource agencies partnering together) or vertical (i.e., between stakeholders and agencies). Results provide estimates of relationships between each antecedent and trust, as well as the relative importance of the antecedents in predicting trust. We conclude by evaluating the state of the literature on trust and providing recommendations for future research.

Introduction

A growing need exists for natural resource organizations to enhance relationships with myriad stakeholders involved in governance of the environment (Decker et al., 2016). Building and sustaining those relationships is a challenging endeavor (Davenport et al., 2007; Metcalf et al., 2015). Scholars identify trust as a key mechanism to facilitate cooperation and collaboration within these types of relationships (Hardin, 1998; Rindfleisch, 2000; Hattori and Lapidus, 2004; Vaske et al., 2007; Höppner, 2009; Olsen and Shindler, 2010; Henry and Dietz, 2011; Christoffersen, 2013; Perry et al., 2017).

Trust, broadly defined, is the willingness of a party to be vulnerable to the actions of another based on expectations that the other has positive intentions and actions toward the trustor (Mayer et al., 1995; Rousseau et al., 1998; Malhotra and Lumineau, 2011; Stern and Coleman, 2015; Riley et al., 2018). The definition of trust as a psychological state also allows for institutions to be targets of trust (PytlikZillig and Kimbrough, 2016). In regards to agency or inter-organizational collaborations, trust has been described as the “willingness to rely on an exchange partner in whom one has confidence” (Ganesan, 1994) and “the degree of confidence partners have in the reliability and integrity of each other” (Aulakh et al., 1996). Trust encompasses integrity, dependability, benevolence, and credibility (Zaheer and Venkatraman, 1995; Zaheer and Harris, 2006).

The primary goal of trust research at the natural resource agency level is to understand how it develops and is sustained (Ring and Van de Ven, 1994; Zaheer and Harris, 2006). However, this aim is hindered by the pronounced lack of clarity regarding factors for building trust in natural resource management (Boschetti et al., 2016; Riley et al., 2018). Indeed, although this topic has received considerable research attention with many empirical studies and conceptual reviews across management, marketing, and other fields (Zaheer and Harris, 2006; Seppänen et al., 2007; Lachapelle and McCool, 2012; Sharp et al., 2013; Agostini and Nosella, 2017), there are still ambiguities surrounding the factors important for building trust. We therefore take an interdisciplinary approach to examine research on antecedents conducted in the natural resources, management, and marketing literatures together. These areas employ similar conceptions of trust as a psychological state defined as the willingness to be vulnerable (Rousseau et al., 1998; Stern and Coleman, 2015; PytlikZillig and Kimbrough, 2016), often operationalize trust in terms of components such as ability, benevolence, and integrity (Mayer et al., 1995) and commonly study similar antecedents. Considering research across fields allows for a clearer view of the factors relevant for trust than would be obtained from considering research in the environmental context alone given the small number of empirical studies on antecedents. With this approach we seek to address several issues within the body of research on trust within natural resource management, and the literature on trust more broadly.

First, because the literature has been largely discipline-specific (Bachmann and Zaheer, 2008; De Jong et al., 2015), there has been a proliferation of constructs proposed as antecedents of trust. This proliferation of labels creates ambiguity in application to natural resource management and makes the task of integrating findings across studies to build a cumulative, coherent field of research more difficult. These studies also tend to empirically examine one or only a few factors for their relationship with trust, even though other antecedent factors are identified as important in qualitative studies. Individual studies also do not enable a sense of the relative importance of each of the many possible antecedent factors determining trust.

Second, there are inconsistencies in findings on the magnitude of the relationship between various antecedents and trust. For example, findings regarding perceptions of reputation and competence as a predictor of trust (Seppänen et al., 2007; Agostini and Nosella, 2017) are mixed. One study suggested that partner reputation was not related to trust (Nielsen, 2007), whereas others found that trust and partner reputation were positively related (Winter et al., 2004; Chu and Fang, 2006; Lui et al., 2006).

Third, important contingencies regarding the relationship between trust and its antecedents have been proposed, but not investigated systematically. Although Zhong et al. (2017) examined relationship duration as a potential moderator between trust and various predictors, other researchers propose at least two additional important contingencies that may play a role in understanding the antecedent to trust relationships. First, Rousseau et al. (1998), Parkins and Mitchell (2005), and Fulmer and Gelfand (2012) noted the importance of examining referents of trust across levels of analyses. Trust can be measured at the interpersonal level (where a particular person within the partner organization is the target of trust perceptions) and at the organizational level (where the organization as a whole is the target of trust perceptions). Second, Borys and Jemison (1989) suggested the type of relationship, namely horizontal (i.e., partnerships between agencies; Baral, 2012, or between agencies and stakeholder organizations; Parkins, 2010; Levesque et al., 2017, for resource management) and vertical (relationships with less reciprocal interdependence, i.e., between non-organized community members and resource management agencies; Olsen and Shindler, 2010; Smith et al., 2013), may alter the magnitude of the relationship between trust and its correlates.

Our goals in this paper therefore are three-fold. First, we categorized antecedents of trust, and integrated empirical and conceptual studies across disciplines. In doing so, our aim was to create meaningful and parsimonious categories to enable more succinct examination of linkages between antecedents and trust. Second, we conducted a comprehensive, quantitative meta-analytic approach to examine relationships between antecedents and trust across research studies and distinguish the relative importance of each. Lastly, we examined how the relationships between trust and its antecedents might vary based on the trust referent (contact person vs. organization) and type of relationship (horizontal vs. vertical).

We begin by reviewing identifiable antecedents and then integrate the perspectives to provide a framework for organizing the antecedents. We then review key findings, levels of analysis, and type of relationship issues as they pertain to the environment. We conclude with a discussion on the practical implications of findings.

Antecedents of Trust

To understand how trust develops, researchers across disciplines have proposed a variety of antecedents. For example, Seppänen et al. (2007) identified past behaviors, similarity, information sharing, reputation, values, commitment, continuity of relationship, integrity, among others as important antecedents. Agostini and Nosella (2017) identified partner attributes (capabilities and cultural sensitivity), relationship attributes (fit, proximity, and dependency), and environmental conditions (technology and competition) as key predictors of trust within the marketing literature. In their review, Zaheer and Harris (2006) suggested that specific organizations' actions and behaviors (i.e., flexibility, feedback), risks and costs, relational aspects interpersonal trust, and cultural factors (i.e., industry, nationality) influence the development of trust. Christoffersen (2013) proposed national culture distance and prior relationships as predictors. Within the environmental domain, Smith et al. (2013) described dispositional trust, shared values, and moral and technical competency as possible predictors of trust. Similarly, Winter et al. (2004) proposed that trust is derived from perceptions of an agency's competence, the risks and benefits of its practices, and its values.

Although the aforementioned studies and reviews differ in number and labels of factors that influence the development of trust, there are similarities in the predictors identified. For example, communication—labeled as feedback, information exchange, information sharing, and level of communication—is typically defined and measured as the extent to which both parties in a relationship are able to freely and frequently share information with one another. Similarly, although they vary on the distinct aspects of culture and levels of granularity, reviews of trust uniformly note the importance of cultural factors. For example, Christoffersen (2013) suggested national cultural distance, operationalized as dissimilarity of values, beliefs, and practices, as an antecedent of trust. Natural resource scholars working within the salient values similarity (SVS) model take an opposite perspective, proposing that similarity and similar values facilitate trust (Cvetkovich and Winter, 2003; Sponarski et al., 2014; Perry et al., 2017). Despite the aforementioned variation, an examination of the empirical studies on trust suggests a common theme across studies examining cultural issues is the extent to which values are shared across organizations, or between an individual and an organization.

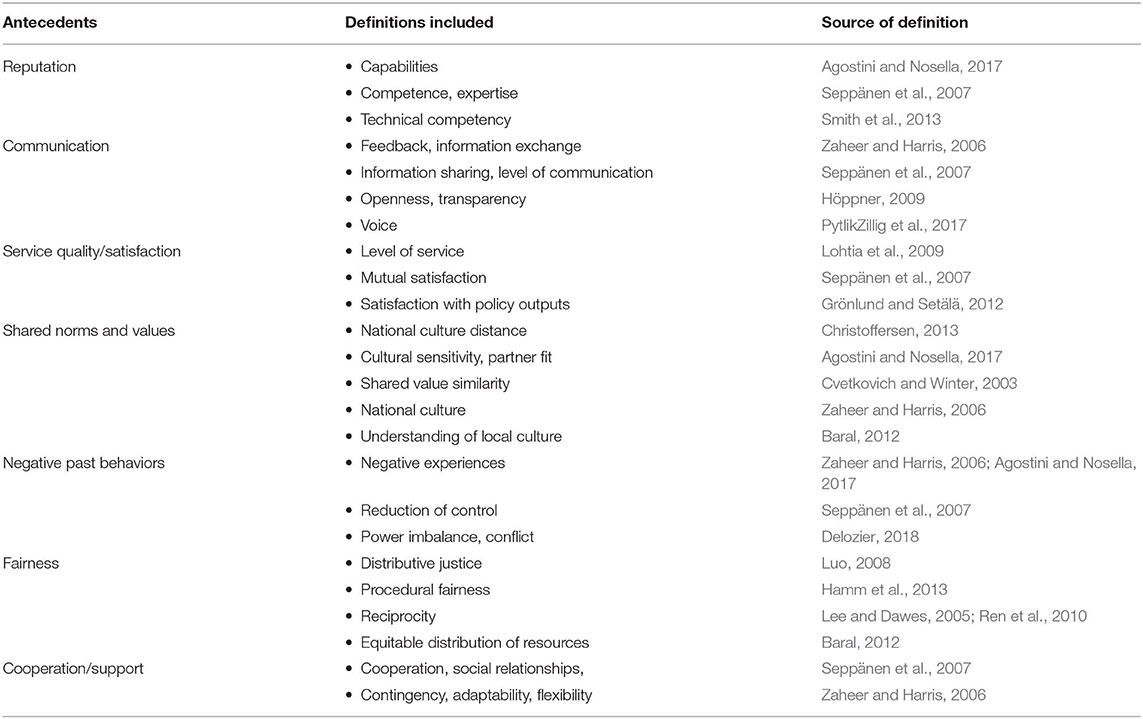

Empirical studies that had examined antecedent factors of trust were investigated and the antecedent variables to trust identified including the construct label, definition, operationalization, and measure. We used a grounded theory approach (Locke, 2002) to the data to capture and organize the antecedent categories that have been empirically studied as antecedents to trust. Based on this systematic examination of the primary studies, an organizing framework was created through an iterative, consensus based approach (Hill et al., 1997). This approach led to the creation of a framework consisting of seven antecedents (Table 1).

One category of antecedents is the reputation of the organization (or the person representing it). Reputation concerns the image that an individual has built up over time (Chen and Tseng, 2005) or the aggregate level of quality and competence that is ascribed to the partner group or organization (Swaminathan and Moorman, 2009). Included in this category are global perceptions of reputation (e.g., this organization has a good reputation in the field; Anderson and Weitz, 1989; Schilke and Cook, 2015) as well as specific perceptions of capability (Corsten and Kumar, 2005), competence and expertise (Moorman et al., 1993; Winter et al., 2004), or status (Lee and Dawes, 2005). One study that labeled the construct being studied as credibility was discovered upon review to have operationalized it as a proxy for the reputation of the organization and thus was placed in this category (Katsikeas et al., 2009).

A second type of antecedent concerns the level of information sharing, communication, and shared understanding that occurs between the two focal organizations. As noted by Goodman and Dion (2001), it is the formal and informal sharing of honest and meaningful information between the parties. This information sharing also include the relevance and timeliness of information exchanged as well as the amount or frequency of information exchange (Coote et al., 2003; Olsen and Sharp, 2013). The majority of studies included in this meta-analysis measured the extent to which trustors communicated with trustee (e.g., Anderson and Weitz, 1989) and exchanged information (e.g., Zhang et al., 2003). This category also includes quality of information shared (e.g., Monczka et al., 2015), frequency of communication (e.g., Perrone et al., 2003), and transparency (e.g., Pirson and Malhotra, 2011).

The third category of antecedents revolves around issues of satisfaction with the quality of service. The satisfaction can be around the level of service (Lohtia et al., 2009) and performance (Ryu et al., 2007), as well as an overall satisfaction with the relationship at the present time (Nyaga et al., 2010; Garbade et al., 2016) based on satisfaction with previous outcomes (Ganesan and Hess, 1997; Olsen and Sharp, 2013; Wald et al., 2019).

A fourth antecedent category is the extent to which focal organizations share similar values, norms, and culture. This notion of relational compatibility includes whether the focal organization shares a set of common beliefs about what behaviors are important or unimportant (Morgan and Hunt, 1994), have compatible relationship norms and expectations (Aulakh et al., 1996), are culturally compatible (Sarkar et al., 2001), and have high levels of goal congruence (Jap and Anderson, 2003). This category of antecedent also includes the extent to which a natural resource agency is perceived to have the same values, goals, and perspectives as citizens and stakeholders (Cvetkovich and Winter, 2003; Needham and Vaske, 2008).

A fifth type of antecedent concerns issues of negative behaviors and interactions (Lachapelle and McCool, 2012). This includes coercion and opportunistic behaviors. Opportunism is defined as self-interest seeking behavior or taking advantage of partner group or organization (Bianchi and Saleh, 2011). Barnes et al. (2010) note that opportunism can include deliberate misrepresentation, evasion of obligations, or limited efforts or actions expected of with a partner.

A sixth set of antecedents describes issues of fairness and reciprocity. Studies have examined types of justice such as procedural and distributive fairness (Jambulingam et al., 2009; Lijeblad et al., 2009; Hemmert et al., 2016; Schroeder and Fulton, 2017) as predictors of trust. Distributive fairness refers to perceived fairness in actual outcomes of decisions, such as the allocation of access to resources, harvest regulations, or allocation of grant money. Procedural fairness involves stakeholders' subjective evaluations of how decisions are crafted and outcomes are determined. For example, one measure targeted the extent to which decision makers conducted a fair and equal decision process (Hamm et al., 2013). Other studies have focused on an overall measure of fairness such as the extent to which a trustee treats other parties equally (Kwon, 2008; Höppner, 2009)

The final category involves issues of cooperation and support or what has been termed relationship building behaviors (Seppänen et al., 2007). Measures used center on issues of cooperation and support and include specific cooperative behaviors such as collaborative planning (Cai et al., 2010) and more general behaviors of coordinating efforts (Jap, 1999; Nyaga et al., 2010). Measures in this category of antecedents include the ability to reach compromise and avoid conflict (Zhang et al., 2003, 2011; Sharma et al., 2015). This category also includes the issue of flexibility or the willingness to customize or adapt one's service to better meet partner needs. This notion of adaptability includes observing and respecting informal obligations of the relationship and modifying the terms for continued value creation (Young-Ybarra and Wiersema, 1999).

With these categories, we placed studies on the antecedents of trust in an organized and systematic framework to investigate the effects of each antecedent and trust perceptions. In this way, we can determine the best evidence findings relevant to the existing literature on understanding factors relevant to trust.

Multilevel Perspective

Scholars argue that trust referents can exist across different levels of analysis (Zaheer et al., 1998; Parkins and Mitchell, 2005; Fulmer and Gelfand, 2012). For example, an interpersonal referent refers to a specific other, such as a contact person in the partner group or organization. An organizational referent refers to trust in an entity, such as a partner organization (Zaheer et al., 1998; Fang et al., 2008; Fulmer and Gelfand, 2012). It is important to note that although the target of trust exists at different levels (interpersonal and organizational referent) in the research literature, trust is typically measured as an individual's perception of that referent level.

Although empirical studies have investigated both trust in the organization and trust in a person within that organization (i.e., Perrone et al., 2003; Fang et al., 2008; Parkins, 2010; Sharp and Curtis, 2014), there have been no attempts to quantitatively measure how the target of trust one is responding to may differentially influence the magnitude of the relationship found between trust and its antecedents (Rousseau et al., 1998). This is particularly important as there is research evidence that relationships between trust and its predictors could vary depending on the referent taken (Zaheer et al., 1998; Fulmer and Gelfand, 2012). For example, Lee and Dawes (2005) discovered that engaging in reciprocity was positively related to trusting an organizational referent but unrelated with interpersonal referents. Other research, however, found that the magnitude of the relationship between both interpersonal and organizational targets of trust and information sharing was similar (Ashnai et al., 2016).

Given the various patterns of relationships between trust and its predictors across referent levels, we explore the level of relationship as a potential moderator. More specifically, we investigate the extent to which the trust referent (i.e., interpersonal target and organizational target) alters the relationship between trust and its antecedents.

Relationship Type

Trust occurs across a variety of relationships. Relational contracting, outsourcing, strategic alliances, citizen participation in decision-making, and stakeholder networks have all grown in frequency and extent of occurrence in recent years. A need to foster trust and collaboration has grown commensurately as these myriad organizational relationships common to environmental management evolve (McEvily et al., 2003; Henry and Dietz, 2011). Research has broadly categorized these varied relationships into vertical and horizontal relationships. Vertical relationships involve greater dependence of the trustor on the trustee. For example, suppliers may be more dependent upon manufacturers. Similarly, stakeholders, such as area residents or hunters (the majority of whom do not create or join coalitions for self-representation) are subject to the policies and regulations enacted by natural resource management agencies (Needham and Vaske, 2008; Höppner, 2009). Horizontal relationships are typified by reciprocal interdependence between the trustor and trustee. Strategic alliances between organizations represent such relationships (Borys and Jemison, 1989; Rindfleisch, 2000; Seppänen et al., 2007; Baral, 2012).

The type of relationship in which trust exists may influence the interaction patterns and nature of the relationships (Borys and Jemison, 1989; Rindfleisch, 2000; Zhong et al., 2017). Empirically, findings provide preliminary support for these differences. For example, Lioukas and Reuer (2015) found that idiosyncratic investments (investing in assets that are useful only for a specific context or application) were not significantly related to trust among alliances (horizontal relationship). Alternately, Lui and Wong (2009) reported a negative relationship between buyers' trust in suppliers (vertical relationship) and their perception of suppliers' opportunism (i.e., contractual and norm violations). Therefore, we explore relationship type (horizontal or vertical relationships) as a potential moderator in the relationship between trust and its antecedents.

Methods

Literature Search

We conducted an extensive search for primary empirical studies reporting a correlation between antecedents and consequences of trust. To identify relevant studies, we first searched computerized databases including PsycINFO, ProQuest, and Google Scholar using several keywords (e.g., interorganizational trust, inter-organizational trust, stakeholder trust, organizational trust, interorganizational distrust, organizational distrust, organizational trustworthiness, interpersonal trust, and relational governance). We also examined the reference lists of existing reviews on trust to ensure we did not miss any empirical papers (Zaheer and Harris, 2006; Seppänen et al., 2007; Agostini and Nosella, 2017) and other meta-analytic studies (Christoffersen, 2013; Vanneste et al., 2014; Zhong et al., 2017). Finally, we searched conference proceedings and presentations for additional working and unpublished papers. This search ran from 2016 to 2018. To ensure that we had sufficient representation from the natural resource literature, in 2019 we conducted a second database search using relevant keywords (e.g., “natural resources” and “wildlife agency” with “trust”), and searched top journals (e.g., Society and Natural Resources) using the keyword “trust.”

We used several criteria to select articles to be included in the final sample. First, each study had to contain enough information to compute a correlation coefficient, such as correlation coefficients, sample sizes, Cohen's d, univariate Fs, or t-values relevant to antecedents and consequences of trust. Studies that only reported these types of relationships with path coefficients or unstandardized beta weights were excluded. Second, the relationships with trust that were measured had to be between two different organizations or two organizational agents. Customers trusting organizations, for example, were excluded from analyses. We also excluded studies that solely examined intra-organizational trust (e.g., employees trusting their managers or co-workers). When multiple interdependent effect sizes were reported in the same sample, we created a linear composite correlation to avoid violating the independence assumption (Hunter and Schmidt, 2004; Geyskens et al., 2009) to account for these relationships. In total, we identified 147 (135 management and marketing and 12 natural resources) studies with 172 independent samples.

Coding

For coding of effect sizes, we prepared a form that specified the information to be extracted from the article (i.e., sample size, effect size, reliability). We also included additional background information (i.e., demographics of sample, measures used) and a space to record questions or concerns with the article. The authors and a doctoral candidate (i.e., the research team) coded 20 articles independently with 75% overlap to assess interrater agreement (IRA). For the straightforward indices (e.g., sample size, effect sizes), the overall agreement was 100%. When it came to labeling the antecedent category and the moderator relationships (i.e., type of relationship), some minor disagreement arose, which were resolved through discussion and consensus decision making. After checking for this initial agreement in coding sheets, at least two individuals coded each article and the research team met biweekly to discuss any challenges or discrepancies within the coding to ensure consistency across coders.

Antecedent Categories

Studies that met the inclusion criteria were examined and antecedent variables to trust identified. The research team came to consensus on what category to place each antecedent based on the framework provided in Table 1. The research team continually reviewed the categories and placement of variables to ensure that there was consistency in coding.

Trust

There is a noted proliferation of measures of trust, and constructs proposed to comprise it (McEvily and Tortoriello, 2011; Boschetti et al., 2016). While trust is conceptualized as willingness to be vulnerable to others, few empirical studies have directly measured felt vulnerability. Most of the studies in our sample combined individual items into a trust scale. Therefore, we coded trust as a unidimensional construct—which is consistent with most measures of trust in the primary studies. We were inclusive in representing trust as it has been operationalized in the literature. The majority of studies measured a general “trust” construct, although many studies utilized different theoretical definitions of trust, including agency trust, inter-organizational trust, social trust, institutional trust, and interpersonal trust.

There were a number of studies in the sample that measured trust as consisting of subcomponents. For example, 19 studies used a measure that conceptualized trust as consisting of predictability, consistency, and faith (Zaheer et al., 1998), 11 studies used a measure with the subcomponents reliability, confidence and integrity (Morgan and Hunt, 1994), 19 studies used a measure with the subcomponents credibility and benevolence (Doney and Cannon, 1997; Ganesan and Hess, 1997), and 8 studies used a measure with the subcomponents honesty and benevolence (Kumar et al., 1995). Researchers who used these measures combined the scores across the subcomponents to form an overall measure of trust, which is what we coded. For the studies that only reported correlations of antecedents with subcomponents of trust, we aggregated the effect sizes into a single score that represented the mean correlation between trust and its antecedent. In our sample, a majority of the studies (103 or 70%) used an established measure of trust (Morgan and Hunt, 1994; such as Mayer et al., 1995) or adapted the trust measure from an established measure. The other 30% of papers developed their own measure of overall trust. We also coded, when provided, reliability information on each trust measure.

Meta-Analytic Procedures

Following the strategy specified by Arthur et al. (2001) and Hunter and Schmidt (2004), we first calculated a sample-weighted mean correlation (r) for each focal relationship. We then estimated the proportion of variance among the effect sizes that was due to sampling error associated with sample sizes (Hunter and Schmidt, 2004). We corrected for unreliability in the antecedent and trust measures using information from the empirical studies (internal consistency alphas; Hall and Brannick, 2002) to derive the corrected estimate of the correlation coefficient (ρ; Hunter and Schmidt, 2004). For studies that did not include an internal consistency measure, we used an artifact distribution. The standard deviation of the corrected estimate was calculated to determine the 95% credibility interval (CV). The CV, built around the corrected coefficient estimate, serves as one method for determining the presence of between-study moderators (Arthur et al., 2001).

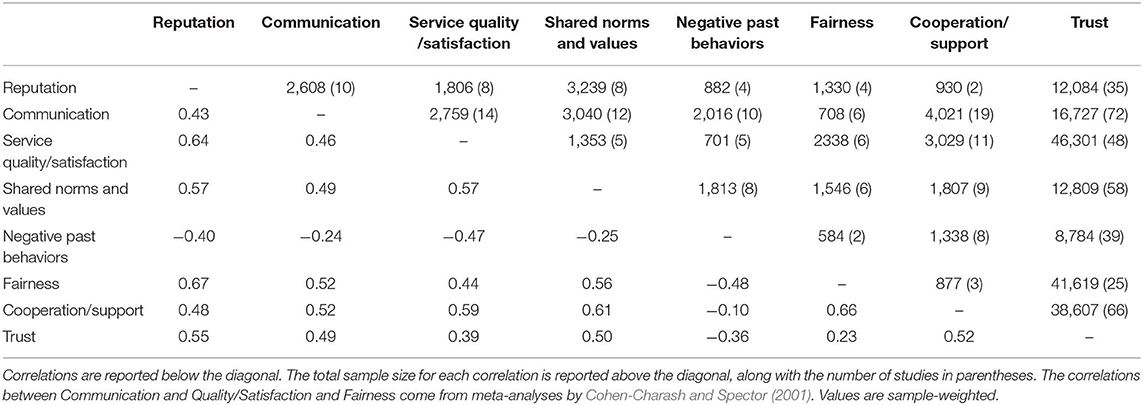

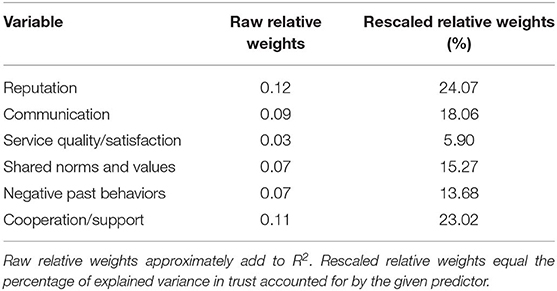

Relative Weights Analysis

We conducted a relative importance analysis to evaluate the unique contribution of each predictor in the total variance accounted for in trust (Tonidandel and LeBreton, 2011). We first created a matrix containing all intercorrelations between predictors and trust found in the studies in our meta-analytic review. Consistent with best practice, we used meta-analytic correlations found in other research (Cohen-Charash and Spector, 2001) as the data points in the correlation matrix for the relationships with few primary studies. We then ran the analysis on this matrix using RWA-Web (Tonidandel and LeBreton, 2015). The initial analysis resulted in an R2 > 1; accordingly, we computed the variance inflation factor (VIF) for each predictor. Fairness yielded the largest VIF (4.38), and values in this range indicate likely multicollinearity issues (Hair et al., 2013, p. 200). We therefore reran the analysis excluding fairness as a predictor. The output for this analysis includes raw relative beta weights and rescaled relative weights that equal the percentage of variance in trust (out of 100%) accounted for by each of the six included antecedent variables.

Moderator Analysis

To detect the possibility of moderating effects, we used the 75% rule proposed by Hunter and Schmidt (2004) and the credibility interval. Simulation research suggests that these methods result in a low Type I error rate when at least 60 samples are included in the meta-analysis, and that they have greater statistical power than other guidelines for detecting moderation (Sagie and Koslowsky, 1993). The 75% rule suggests that when variance from sampling and measurement error accounts for <75% of the observed variance, there is a potential for a moderator to be in effect. That is, if at least 25% of the variance in a relationship is left unexplained after accounting for sampling error, this “leftover” may signal that there are moderators. The credibility interval illustrates the degree to which a relationship is consistent across studies, and therefore generalizes across contexts. A wide interval that includes zero indicates the presence of moderators. We also conducted Z-tests to determine differences between subgroups for our moderators.

Results

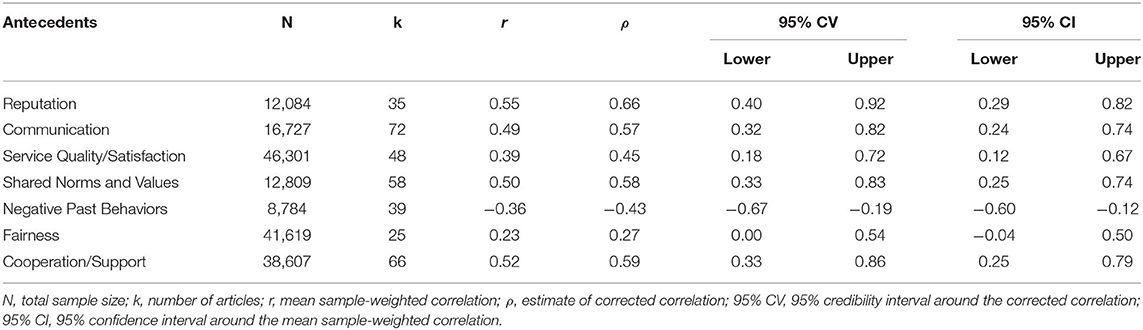

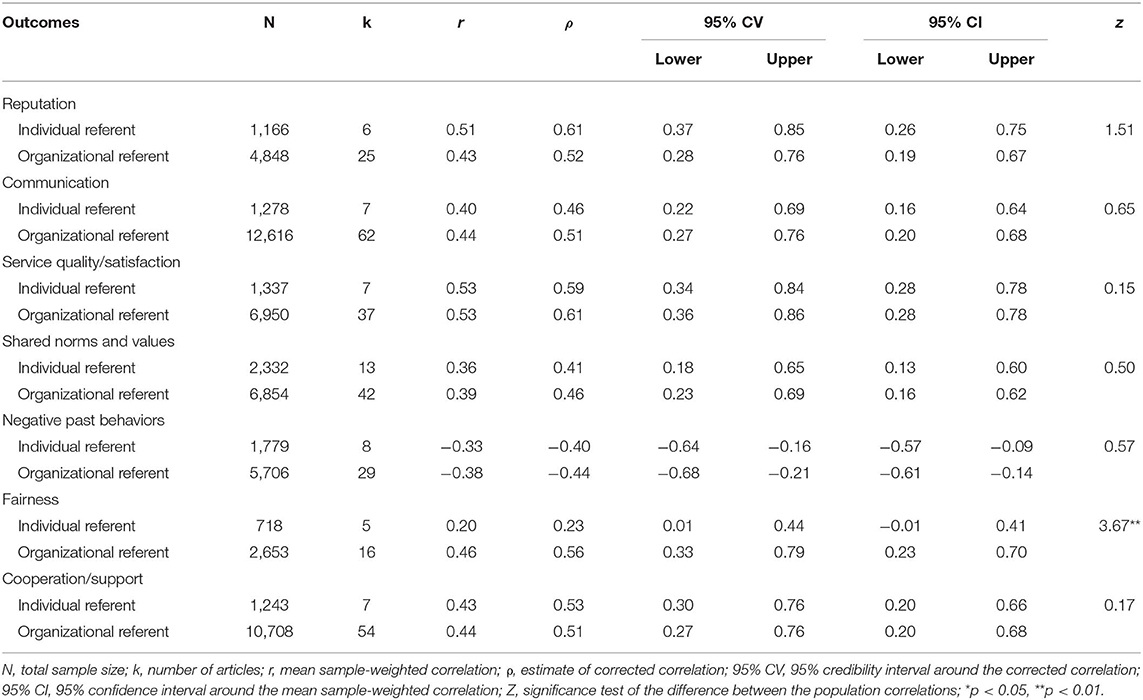

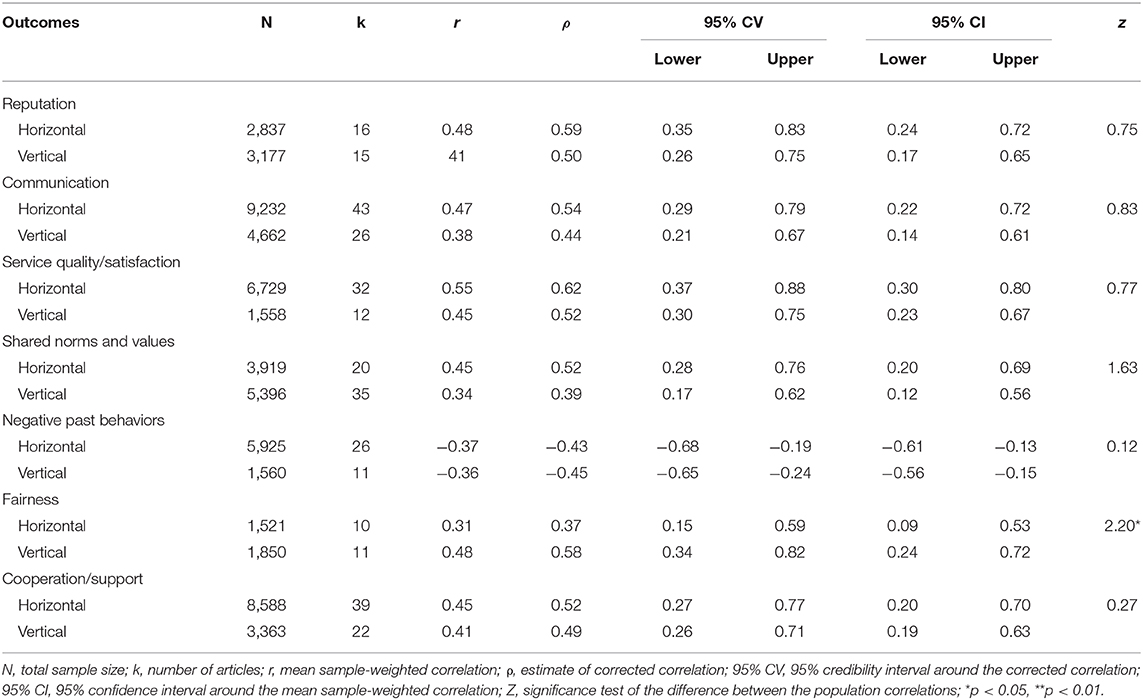

Meta-analytic estimates, sample sizes, 95% credibility intervals, and 95% confidence intervals for the antecedents of trust are reported in Table 2. Of the seven antecedents identified in the table, reputation (ρ = 0.66), cooperation and support (ρ = 0.59), shared norms and values (ρ = 0.58), and communication were strong correlates (ρ = 0.57). Service quality and satisfaction (ρ = 0.45) and negative past behaviors (ρ = −0.43) were moderately strong correlates, and fairness was also correlated with trust (ρ = 0.27).

The intercorrelation matrix calculated for the relative weights analysis based on the complete sample of studies is shown in Table 3, and results of the analysis are in Table 4.

The set of six antecedents (without fairness) explained ~49% of the variance in trust. The rescaled relative weights indicated that reputation (24%) and cooperation/Support (23%) accounted for most of the explained variance in trust, followed in effect by communication (18%), shared values (15%), and negative past behavior (14%), with service quality/satisfaction accounting for the least amount of explained variance (6%).

Detectable relationships of proposed moderators, of the referent of trust and the type of relationship (i.e., vertical or horizontal) are displayed in Tables 5, 6, respectively. For the trust referent, the relationship between fairness and trust is stronger for individual referents (ρ = 0.23) than for organizational referents (ρ = 0.56, z = 3.67, p < 0.01). Similarly, the relationship between fairness and trust also varied based on the type of relationship. Fairness and trust are more strongly related in vertical relationships (ρ = 0.58), than horizontal relationships (ρ = 0.37, z = 2.20, p < 0.05).

Discussion

There is growing evidence that trust is crucial for effective, efficient management of natural resources (Cvetkovich and Winter, 2003; Henry and Dietz, 2011; Stern and Baird, 2015). A better understanding of the antecedent factors of trust—factors affecting how trust is generated and sustained—in natural resource organizations or agencies will enable organizations to better serve the public good. The purpose of our study was to conduct a comprehensive meta-analysis of trust using an integrated framework of antecedents studied across disciplines with the dual objectives of clarifying theory and gaining insights useful to natural resource managers. In addition, we investigated two moderators that have yet to be studied systematically: the type of relationship (i.e., vertical vs. horizontal), and the trust referent (i.e., interpersonal vs. organizational). Our meta-analysis presents quantitative evidence to clarify some issues in the literature. Of seven antecedents proposed in our integrated framework, all were meaningfully related to trust. High quality services, fair and just behaviors, a strong reputation, high levels of communication, cooperation/support, along with shared norms and values, and whether or not negative behaviors by organization have occurred in the past were attributes with influences on levels of trust in organizations.

We can now make stronger conclusions relevant to factors where mixed results have been reported across primary studies. For example, as noted in the introduction, some primary studies found no relationship of reputation and trust (Nielsen, 2007) while others did detect an effect (Chu and Fang, 2006) with some variation in the size of effect found (Lui et al., 2006). Across the studies from our meta-analysis, we now have a firm point estimate of an effect—and where the 95% confidence interval does not include zero. This leads to the conclusion that reputation is an important factor relevant to trust.

In addition, the results of the meta-analysis indicate that all six of the antecedents included in the relative weights analysis account for unique variance in trust. Due to multicollinearity concerns, fairness was excluded from this analysis. This complication is consistent with research that has evaluated fairness as an outcome of the other antecedents of trust (e.g., communication, Kernan and Hanges, 2002, and reputation, Wagner et al., 2011). Our results suggest the most important factors impacting trust are reputation and cooperation/support. Communication, shared values, and negative behaviors accounted for smaller amounts of variance, and satisfaction with service quality/relationship accounted for the least. Thus, the relative weights findings provide additional information from the average correlational data generated from the meta-analysis. For example, although quality service and satisfaction with the relationship displayed a relationship with trust as indicated by the mean sample-weighted correlation and the estimate of corrected correlation, the relative weights show that this factor actually accounted for less unique variance than other factors.

Such distinctions between relative weights and meta-analytic findings are expected as the six antecedent (predictor) factors are intercorrelated to varying degrees [see Tonidandel and LeBreton (2015) for a discussion of differences between regression coefficients and relative weights]. One interpretation may be that key antecedents such as reputation and cooperation/support are important for determining quality service/satisfaction, thereby leaving service quality to explain less unique variance in trust. Reputation and expectations for performance by natural resource managers have been identified previously in other contexts as important for rational trust, which is usually predicated on past observations and anticipated abilities to produce desired outcomes (Stern and Baird, 2015).

In terms of moderators, the trust referent affected the meta-analytic correlation between trust and fairness. When the target for the measurement of trust was an organizational referent, the relationship between trust and fairness was stronger than when the target was a particular person in the organization. This finding suggests that for a natural resource agency to build trust with its partners, one needs to consider how the agency as a whole can engage in behaviors that are interpreted as high on justice; this includes the way outcomes are distributed to stakeholder groups, and how one follows previously communicated procedures. Regarding the type of relationship, fairness was more strongly related to trust for vertical relationships and less related in horizontal partner/alliance relationships. Some natural resource stakeholders are required to abide by agency regulations and are therefore subject to the authority of the agency; our results indicate that in such vertical relationships, the perception of an agency's fairness is even more strongly linked to trust than it is in partnerships with equal power distributions.

Level of trust is frequently identified as important for predicting key outcomes such as loyalty (Agostini and Nosella, 2017), sharing of knowledge (Zaheer and Harris, 2006), and intentions to continue in the relationship/partnership (Seppänen et al., 2007). Trust in the U.S. Forest Service as a management agency was found to be correlated with attitudes toward forest management actions such as prescribed fire or thinning (Vaske et al., 2007). Similarly, stakeholder participation in hunting to manage chronic wasting disease in Wisconsin was partially predicated on level of trust in the state wildlife agency (Vaske, 2010). Quantitative evidence from our meta-analysis suggests implications for improving trust perceptions in turn can lead to positive outcomes for the agency and their stakeholders. In particular, our findings point to priorities as to where efforts should be placed to build trust with citizen groups or other entities. For example, demonstrating fair and just behaviors via procedural justice, distributive justice, and reciprocity may be a direct way to build trust (Leahy and Anderson, 2008). Stakeholder and agency engagement that is perceived to be procedurally fair requires efforts that go beyond simple participation in decision-making (Lauber et al., 2012). Typically, four elements of process and procedures contribute to stakeholder determination about their fairness: opportunities for participation, a neutral forum in which participation occurs, trustworthy authorities, and benevolence by which stakeholders were treated. Importantly, given that fairness exhibited the greatest degree of interrelatedness with the other antecedents, maintaining fair practices may be contingent upon, and likely inform, levels of the other trust factors. Finally, enhancing cooperative behaviors in a timely manner can help to facilitate trust between two entities.

Alternatively, obtaining trust does not automatically translate into greater participation by stakeholders in resource management (Smith et al., 2013). Those researchers revealed an inverse relationship between levels of trust and stakeholder participation in natural resource management. Finally, as discussed earlier, reputation of an organization, such as a state wildlife agency, influences levels of relational trust, which in turn influence the ability of agencies to make sustained decisions (Stern and Coleman, 2015). Organizations that focus on showcasing expertise and competencies, while also being values-driven and displaying integrity as an agency are more likely to be viewed positively and develop rational trust by their stakeholders.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

As with any comprehensive attempt to aggregate data across primary empirical studies, the current meta-analysis has limitations but also point to needed research on trust in the natural resource literature. The majority of studies included in the meta-analysis did not use a measure that directly captured the conceptual definition of trust of being vulnerable to others. Instead many papers included an overall measure of trust and confidence in others or measured trust in terms of various components that some have argued are better described as factors of perceived trustworthiness (Mayer et al., 2006). For the meta-analysis, we followed the empirical research in how trust has been measured in studies. Therefore, the results do not speak directly to the issue of antecedents to perceptions of vulnerability. More research is need to separate out vulnerability perceptions from other trust measures.

The majority of studies included in the meta-analysis were single source and cross-sectional in nature. Though there are theoretical explanations in the primary studies for why certain factors should be considered as antecedents of trust, in most empirical studies antecedents and trust variables were measured at the same time, often by the same person. Blume et al. (2010) indicated in their meta-analysis on training transfer how measures of the strength of relationship frequently are inflated when data are obtained from the same source (self-report) within the same measurement context (where the antecedents and outcome measures are obtained at the same time). Future research is needed that gather data from multiple sources and/or conducted longitudinal studies that separated out by time the antecedents from the measure of trust.

Similarly, without a longitudinal focus, it is unclear how the antecedents to trust contribute to the overall development of trust between entities over time. Schilke and Cook (2013) created a process theory that depicts the developmental stages of trust. Although they propose certain predictors at various stages (i.e., reputation and familiarity influences trust at the initiation stage; interpersonal interactions and communication at the negotiation stage; shared understanding at the operation stage), the current empirical research on trust does not allow their model to be tested. This situation clearly calls for longitudinal studies that separate out when antecedents, trust, and trust outcomes are measured to test theoretical models of trust development through time. Moreover, given the issue with multicollinearity identified with fairness we strongly recommend that future studies adopt more fine-grained measures to capture fairness perceptions (e.g., for procedural, Riley et al., 2018, or distributive fairness, PytlikZillig et al., 2017), as opposed to generalized measures. Additionally, more studies are needed that gather trust data from multiple sources so as to better inform estimates of interrater agreement. Then research could examine the strength of the trust perceptions across individuals in an agency similar to the research that has effectively examined the relationship of within group variability in organizational climate perceptions on outcomes such as customer satisfaction (Schneider et al., 2002).

Finally, we were unable to differentiate between different types of trust (i.e., goodwill-based trust, calculative trust) as our focus was on overall trust and that there were not enough information in the primary studies to break down trust into component parts for analysis. There is an opportunity for future research to more clearly define the trust construct and use of well-validated multidimensional scales with divergent validity to help examine this issue more fully.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation, to any qualified researcher.

Author Contributions

JF and SR conceptualized and designed the study method and contributed in the writing. JF also performed data coding and directed the analysis of the data. TL and JV performed data coding, analyzed data, and contributed writing.

Funding

Our research was funded by the United States Fish and Wildlife Service through the Pittman-Robertson Wildlife Restoration Act Grant MI W-155-R, and the Michigan Department of Natural Resources through the Partnership for Ecosystem Research and Management.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Stanton Mak for his assistance with data coding.

References

Agostini, L., and Nosella, A. (2017). Interorganizational relationships in marketing: A critical review and research agenda. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 19:131–150. doi: 10.1111/ijmr.12084

Anderson, E., and Weitz, B. (1989). Determinants of continuity in conventional industrial channel dyads. Market. Sci. 8, 310–323. doi: 10.1287/mksc.8.4.310

Arthur, W. Jr., Bennett, W. Jr., and Huffcutt, A. I. (2001). Conducting Meta-Analysis Using SAS. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. doi: 10.4324/9781410600028

Ashnai, B., Henneberg, S. C., Naudé, P., and Francescucci, A. (2016). Inter-personal and inter-organizational trust in business relationships: an attitude–behavior–outcome model. Ind. Market. Manag. 52, 128–139. doi: 10.1016/j.indmarman.2015.05.020

Aulakh, P. S., Kotabe, M., and Sahay, A. (1996). Trust and performance in cross-border marketing partnerships: a behavioral approach. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 27, 1005–1032. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8490161

Bachmann, R., and Zaheer, A. (2008). “Trust in inter-organizational relations,” in Oxford Handbook of Inter-organizational Relations, eds S. Cropper, M. Ebers, C. Huxham, and P. S. Ring (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 533–554. doi: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199282944.003.0020

Baral, N. (2012). Empirical analysis of factors explaining local governing bodies' trust for administering agencies in community-based conservation. J. Environ. Manag. 103, 41–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2012.02.031

Barnes, B. R., Leonidou, L. C., Siu, N. Y., and Leonidou, C. N. (2010). Opportunism as the inhibiting trigger for developing long-term-oriented Western exporter–Hong Kong importer relationships. J. Int. Market. 18, 35–63. doi: 10.1509/jimk.18.2.35

Bianchi, C. C., and Saleh, M. A. (2011). Antecedents of importer relationship performance in Latin America. J. Bus. Res. 64, 258–265. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2009.11.010

Blume, B. D., Ford, J. K., Baldwin, T. T., and Huang, J. L. (2010). Transfer of training: a meta-analytic review. J. Manage. 36, 1065–1105. doi: 10.1177/0149206309352880

Borys, B., and Jemison, D. B. (1989). Hybrid arrangements as strategic alliances: theoretical issues in organizational combinations. Acad. Manag. Rev. 14, 234–249. doi: 10.5465/amr.1989.4282106

Boschetti, F., Cvitanovic, C., Fleming, A., and Fulton, E. (2016). A call for empirically based guidelines for building trust among stakeholders in environmental sustainability projects. Sustainab. Sci. 11, 855–859. doi: 10.1007/s11625-016-0382-4

Cai, S., Jun, M., and Yang, Z. (2010). Implementing supply chain information integration in China: The role of institutional forces and trust. J. Oper. Manag. 28, 257–268. doi: 10.1016/j.jom.2009.11.005

Chen, H. M., and Tseng, C. H. (2005). The performance of marketing alliances between the tourism industry and credit card issuing banks in Taiwan. Tour. Manag. 26, 15–24. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2003.08.018

Christoffersen, J. (2013). A review of antecedents of international strategic alliance performance: synthesized evidence and new directions for core constructs. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 15, 66–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2370.2012.00335.x

Chu, S. Y., and Fang, W. C. (2006). Exploring the relationships of trust and commitment in supply chain management. J. Am. Acad. Bus. 9, 224–228.

Cohen-Charash, Y., and Spector, P. E. (2001). The role of justice in organizations: a meta-analysis. Org. Behav. Hum. Dec. Proc. 86, 278–321. doi: 10.1006/obhd.2001.2958

Coote, L. V., Forrest, E. J., and Tam, T. W. (2003). An investigation into commitment in non-Western industrial marketing relationships. Ind. Market. Manag. 32, 595–604. doi: 10.1016/S0019-8501(03)00017-8

Corsten, D., and Kumar, N. (2005). Do suppliers benefit from collaborative relationships with large retailers? An empirical investigation of efficient consumer response adoption. J. Mark. 69, 80–94. doi: 10.1509/jmkg.69.3.80.66360

Cvetkovich, G., and Winter, P. L. (2003). Trust and social representations of the management of threatened and endangered species. Environ. Behav. 35, 286–307. doi: 10.1177/0013916502250139

Davenport, M. A., Leahy, J. E., Anderson, D. H., and Jakes, P. J. (2007). Building trust in natural resource management within local communities: a case study of the Midewin National Tallgrass Prairie. Environ. Manag. 39, 353–368. doi: 10.1007/s00267-006-0016-1

De Jong, B. A., Kroon, D. P., and Schilke, O. (2015). “The future of organizational trust research: A content-analytic synthesis of scholarly recommendations and review of recent developments,” in Trust in Social Dilemmas, eds P. van Lange, B. Rockenbach, and T. Yamagishi (New York, NY: Oxford University Press), 173–194.

Decker, D., Smith, C., Forstchen, A., Hare, D., Pomeranz, E., Doyle-Capitman, C., et al. (2016). Governance principles for wildlife conservation in the 21st century. Conserv. Lett. 9, 290–295. doi: 10.1111/conl.12211

Delozier, J. L. (2018). Boundary spanners and trust development between stakeholders in integrated water resource management: a mixed methods study (Dissertations and Theses in natural Resources), 266. Available online at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/natresdiss/266 (accessed February 20, 2019).

Doney, P. M., and Cannon, J. P. (1997). An examination of the nature of trust in buyer–seller relationships. J. Market. 61, 35–51 doi: 10.1177/002224299706100203

Fang, E., Palmatier, R. W., Scheer, L. K., and Li, N. (2008). Trust at different organizational levels. J. Market. 72, 80–98. doi: 10.1509/jmkg.72.2.80

Fulmer, C. A., and Gelfand, M. J. (2012). At what level (and in whom) we trust: trust across multiple organizational levels. J. Manage. 38, 1167–1230. doi: 10.1177/0149206312439327

Ganesan, S. (1994). Determinants of long-term orientation in buyer-seller relationships. J. Market. 58, 1–19. doi: 10.1177/002224299405800201

Ganesan, S., and Hess, R. (1997). Dimensions and levels of trust: implications for commitment to a relationship. Mark. Lett. 8, 439–448. doi: 10.1023/A:1007955514781

Garbade, P. J. P., Omta, S. W. F., and Fortuin, F. T. J. M. (2016). The interplay of structural and relational governance in innovation alliances. J. Chain Netw. Sci. 16, 117–134. doi: 10.3920/JCNS2014.x016

Geyskens, I., Krishnan, R., Steenkamp, J. B. E., and Cunha, P. V. (2009). A review and evaluation of meta-analysis practices in management research. J. Manag. 35, 393–419. doi: 10.1177/0149206308328501

Goodman, L. E., and Dion, P. A. (2001). The determinants of commitment in the distributor–manufacturer relationship. Ind. Market. Manag. 30, 287–300. doi: 10.1016/S0019-8501(99)00092-9

Grönlund, K., and Setälä, M. (2012). In honest officials we trust: Institutional confidence in Europe. Am. Rev. Pub. Admin. 42, 523–542. doi: 10.1177/0275074011412946

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., and Anderson, R. E. (2013). Multivariate Data Analysis: Pearson New International Edition. Essex: Pearson Higher Ed.

Hall, S. M., and Brannick, M. T. (2002). Comparison of two random-effects methods of meta-analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 87:377. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.87.2.377

Hamm, J. A., PytlikZillig, L. M., Herian, M. N., Tomkins, A. J., Dietrich, H., and Michaels, S. (2013). Trust and intention to comply with a water allocation decision: the moderating roles of knowledge and consistency. Ecol. Soc. 18:180449. doi: 10.5751/ES-05849-180449

Hardin, R. (1998). “Trust in government,” in Trust and Governance, eds. V. Braithwaitte and M. Levi (New York, NY: Russel Sage), 9–27.

Hattori, R. A., and Lapidus, T. (2004). Collaboration, trust and innovative change. J. Change Manag. 4, 97–104. doi: 10.1080/14697010320001549197

Hemmert, M., Kim, D., Kim, J., and Cho, B. (2016). Building the supplier's trust: role of institutional forces and buyer firm practices. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 180, 25–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpe.2016.05.023

Henry, A. D., and Dietz, T. (2011). Information, networks, and the complexity of trust in commons governance. Int. J. Commons 5, 188–212. doi: 10.18352/ijc.312

Hill, C. E., Thompson, B. J., and Williams, E. N. (1997). A guide to conducting consensual qualitative research. Couns. Psychol. 25, 517–572. doi: 10.1177/0011000097254001

Höppner, C. (2009). Trust—a monolithic panacea in land use planning?. Land Use Policy 26, 1046–1054. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2008.12.007

Hunter, J. E., and Schmidt, F. L. (2004). Methods of Meta-Analysis: Correcting Error and Bias in Research Findings, 2nd Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Jambulingam, T., Kathuria, R., and Nevin, J. R. (2009). How fairness garners loyalty in the pharmaceutical supply chain: role of trust in the wholesaler-pharmacy relationship. Int. J. Pharm. Healthcare Market. 3, 305–322. doi: 10.1108/17506120911006029

Jap, S. D. (1999). Pie-expansion efforts: collaboration processes in buyer-supplier relationships. J. Market. Res. 36, 461–475. doi: 10.1177/002224379903600405

Jap, S. D., and Anderson, E. (2003). Safeguarding interorganizational performance and continuity under ex post opportunism. Manage. Sci. 49, 1684–1701. doi: 10.1287/mnsc.49.12.1684.25112

Katsikeas, C. S., Skarmeas, D., and Bello, D. C. (2009). Developing successful trust-based international exchange relationships. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 40, 132–155. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8400401

Kernan, M. C., and Hanges, P. J. (2002). Survivor reactions to reorganization: antecedents and consequences of procedural, interpersonal, and informational justice. J. Appl. Psychol. 87:916. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.87.5.916

Kumar, N., Scheer, L. K., and Steenkamp, J. B. E. (1995). The effects of perceived interdependence on dealer attitudes. J. Market. Res. 32, 348–356. doi: 10.1177/002224379503200309

Kwon, Y. C. (2008). Antecedents and consequences of international joint venture partnerships: a social exchange perspective. Int. Bus. Rev. 17, 559–573. doi: 10.1016/j.ibusrev.2008.07.002

Lachapelle, P. R., and McCool, S. F. (2012). The role of trust in community wildland fire protection planning. Soc. Nat. Resourc. 25, 321–335. doi: 10.1080/08941920.2011.569855

Lauber, T. B., Decker, D. J., Leong, K. M., Chase, L. C., and Shusler, T. M. (2012). “Stakeholder engagement in wildlife management,” in Human Dimensions of Wildlife Management, eds D. J. Decker, S. J. Riley, and W. F. Siemer (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University), 139–156.

Leahy, J. E., and Anderson, D. H. (2008). Trust factors in community–water resource management agency relationships. Landsc. Urban Plan. 87, 100–107. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2008.05.004

Lee, D. Y., and Dawes, P. L. (2005). Guanxi, trust, and long-term orientation in Chinese business markets. J. Int. Market. 13, 28–56. doi: 10.1509/jimk.13.2.28.64860

Levesque, V. R., Calhoun, A. J., Bell, K. P., and Johnson, T. R. (2017). Turning contention into collaboration: engaging power, trust, and learning in collaborative networks. Soc. Nat. Resourc. 30, 245–260. doi: 10.1080/08941920.2016.1180726

Lijeblad, A., Borrie, W. T., and Watson, A. E. (2009). Determinants of trust for public lands: fire and fuels management on the Bitterroot National Forest. Environ. Manage. 43, 571–584. doi: 10.1007/s00267-008-9230-3

Lioukas, C. S., and Reuer, J. J. (2015). Isolating trust outcomes from exchange relationships: social exchange and learning benefits of prior ties in alliances. Acad. Manag. J. 58, 1826–1847. doi: 10.5465/amj.2011.0934

Locke, K. (2002). “The grounded theory approach to qualitative research,” in Measuring and Analyzing Behavior in Organizations: Advances in Measurement and Data Analysis, eds F. Drasgow and N. Schmitt (San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass).

Lohtia, R., Bello, D. C., and Porter, C. E. (2009). Building trust in US–Japanese business relationships: mediating role of cultural sensitivity. Ind. Market. Manag. 38, 239–252. doi: 10.1016/j.indmarman.2007.06.016

Lui, S. S., Ngo, H. Y., and Hon, A. H. Y. (2006). Coercive strategy in interfirm cooperation. J. Bus. Res. 59, 466–474. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2005.09.001

Lui, S. S., Wong, Y. Y, and Liu, W. (2009). Asset specificity roles in interfirm cooperation: reducing opportunistic behavior or increasing cooperative behavior? J. Bus. Res. 6, 1214–1219. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2008.08.003

Luo, Y. (2008). Procedural fairness and interfirm cooperation in strategic alliances. Strat. Manag. J. 29, 27–46. doi: 10.1002/smj.646

Malhotra, D., and Lumineau, F. (2011). Trust and collaboration in the aftermath of conflict: The effects of contract structure. Acad. Manag. J. 54, 981–998. doi: 10.5465/amj.2009.0683

Mayer, R. C., Davis, J. H., and Schoorman, F. D. (1995). An integrative model of organizational trust. Acad. Manag. Rev. 20, 709–734. doi: 10.5465/amr.1995.9508080335

Mayer, R. C., Davis, J. H., and Schoorman, F. D. (2006). “An integrative model of organizational trust”, in Organizational Trust: A Reader. ed R. M. Kramer (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 82–108.

McEvily, B., Perrone, V., and Zaheer, A. (2003). Trust as an organizing principle. Org. Sci. 14, 91–103. doi: 10.1287/orsc.14.1.91.12814

McEvily, B., and Tortoriello, M. (2011). Measuring trust in organisational research: review and recommendations. J. Trust Research 1, 23–63. doi: 10.1080/21515581.2011.552424

Metcalf, E. C., Mohr, J. J., Yung, L., Metcalf, P., and Craig, D. (2015). The role of trust in restoration success: public engagement and temporal and spatial scale in a complex social-ecological system. Restor. Ecol. 23, 315–324. doi: 10.1111/rec.12188

Monczka, R. M., Handfield, R. B., Giunipero, L. C., and Patterson, J. L. (2015). Purchasing and Supply Chain Management. Boston, MA: Cengage Learning.

Moorman, C., Deshpande, R., and Zaltman, G. (1993). Factors affecting trust in market research relationships. J. Market. 57, 81–101. doi: 10.1177/002224299305700106

Morgan, R. M., and Hunt, S. D. (1994). The commitment-trust theory of relationship marketing. J. Market. 58, 20–38. doi: 10.1177/002224299405800302

Needham, M. D., and Vaske, J. J. (2008). Hunter perceptions of similarity and trust in wildlife agencies and personal risk associated with chronic wasting disease. Soc. Nat. Resour. 21, 197–214. doi: 10.1080/08941920701816336

Nielsen, B. B. (2007). Determining international strategic alliance performance: a multidimensional approach. Int. Bus. Rev. 16, 337–361. doi: 10.1016/j.ibusrev.2007.02.004

Nyaga, G. N., Whipple, J. M., and Lynch, D. F. (2010). Examining supply chain relationships: do buyer and supplier perspectives on collaborative relationships differ? J. Oper. Manag. 28, 101–114. doi: 10.1016/j.jom.2009.07.005

Olsen, C. S., and Sharp, E. (2013). Building community–agency trust in fire-affected communities in Australia and the United States. Int. J. Wildland Fire 22, 822–831. doi: 10.1071/WF12086

Olsen, C. S., and Shindler, B. A. (2010). Trust, acceptance, and citizen–agency interactions after large fires: influences on planning processes. Int. J. Wildland Fire 19, 137–147. doi: 10.1071/WF08168

Parkins, J. R. (2010). The problem with trust: insights from advisory committees in the forest sector of Alberta. Soc. Nat. Resourc. 23, 822–836. doi: 10.1080/08941920802545792

Parkins, J. R., and Mitchell, R. E. (2005). Public participation as public debate: a deliberative turn in natural resource management. Soc. Nat. Resourc. 18, 529–540. doi: 10.1080/08941920590947977

Perrone, V., Zaheer, A., and McEvily, B. (2003). Free to be trusted? Organizational constraints on trust in boundary spanners. Org. Sci. 14, 422–439. doi: 10.1287/orsc.14.4.422.17487

Perry, E. E., Needham, M. D., and Cramer, L. A. (2017). Coastal resident trust, similarity, attitudes, and intentions regarding new marine reserves in Oregon. Soc. Nat. Resourc. 30, 315–330. doi: 10.1080/08941920.2016.1239150

Pirson, M., and Malhotra, D. (2011). Foundations of organizational trust: what matters to different stakeholders? Org. Sci. 22, 1087–1104. doi: 10.1287/orsc.1100.0581

PytlikZillig, L. M., and Kimbrough, C. D. (2016). “Consensus on conceptualizations and definitions of trust: are we there yet?” in Interdisciplinary Perspectives on Trust (Cham: Springer), 17–47. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-22261-5_2

PytlikZillig, L. M., Kimbrough, C. D., Shockley, E., Neal, T. M., Herian, M. N., Hamm, J. A., et al. (2017). A longitudinal and experimental study of the impact of knowledge on the bases of institutional trust. PLoS ONE 12:e0175387. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0175387

Ren, X., Oh, S., and Noh, J. (2010). Managing supplier–retailer relationships: From institutional and task environment perspectives. Ind. Market. Manag. 39, 593–604. doi: 10.1016/j.indmarman.2009.09.002

Riley, S. J., Ford, J. K., Triezenberg, H. A., and Lederle, P. E. (2018). Stakeholder trust in a state wildlife agency. J. Wildlife Manag. 82, 1528–1535. doi: 10.1002/jwmg.21501

Rindfleisch, A. (2000). Organizational trust and interfirm cooperation: an examination of horizontal versus vertical alliances. Mark. Lett. 11, 81–95. doi: 10.1023/A:1008107011529

Ring, P. S., and Van de Ven, A. H. (1994). Developmental processes of cooperative interorganizational relationships. Acad. Manag. Rev. 19, 90–118. doi: 10.5465/amr.1994.9410122009

Rousseau, D. M., Sitkin, S. B., Burt, R. S., and Camerer, C. (1998). Not so different after all: a cross-discipline view of trust. Acad. Manag. Rev. 23, 393–404. doi: 10.5465/amr.1998.926617

Ryu, S., Park, J. E., and Min, S. (2007). Factors of determining long-term orientation in interfirm relationships. J. Bus. Res. 60, 1225–1233. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2006.09.031

Sagie, A., and Koslowsky, M. (1993). Detecting moderators with meta-analysis: an evaluation and comparison of techniques. Pers. Psychol. 46, 629–640. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6570.1993.tb00888.x

Sarkar, M. B., Echambadi, R., Cavusgil, S. T., and Aulakh, P. S. (2001). The influence of complementarity, compatibility, and relationship capital on alliance performance. J. Acad. Market. Sci. 29, 358–373. doi: 10.1177/03079450094216

Schilke, O., and Cook, K. S. (2013). A cross-level process theory of trust development in interorganizational relationships. Strateg. Organ. 11, 281–303. doi: 10.1177/1476127012472096

Schilke, O., and Cook, K. S. (2015). Sources of alliance partner trustworthiness: integrating calculative and relational perspectives. Strat. Manag. J. 36, 276–297. doi: 10.1002/smj.2208

Schneider, B., Salvaggio, A. N., and Subirats, M. (2002). Climate strength: a new direction for climate research. J. Appl. Psychol. 87, 220–229. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.87.2.220

Schroeder, S. A., and Fulton, D. C. (2017). Voice, perceived fairness, agency trust, and acceptance of management decisions among Minnesota anglers. Soc. Nat. Resour. 30, 569–584. doi: 10.1080/08941920.2016.1238987

Seppänen, R., Blomqvist, K., and Sundqvist, S. (2007). Measuring inter-organizational trust—a critical review of the empirical research in 1990–2003. Ind. Market. Manag. 36, 249–265. doi: 10.1016/j.indmarman.2005.09.003

Sharma, N., Young, L. C., and Wilkinson, I. (2015). The nature and role of different types of commitment in inter-firm relationship cooperation. J. Bus. Ind. Market. 30, 45–59. doi: 10.1108/JBIM-11-2012-0202

Sharp, E., and Curtis, A. (2014). Can NRM agencies rely on capable and effective staff to build trust in the agency? Austr. J. Environ. Manag. 21, 268–280. doi: 10.1080/14486563.2014.881306

Sharp, E. A., Thwaites, R., Curtis, A., and Millar, J. (2013). Trust and trustworthiness: conceptual distinctions and their implications for natural resources management. J. Environ. Plann. Manag. 56, 1246–1265. doi: 10.1080/09640568.2012.717052

Smith, J. W., Leahy, J. E., Anderson, D. H., and Davenport, M. A. (2013). Community/agency trust and public involvement in resource planning. Soc. Nat. Resour. 26, 452–471. doi: 10.1080/08941920.2012.678465

Sponarski, C. C., Vaske, J. J., Bath, A. J., and Musiani, M. M. (2014). Salient values, social trust, and attitudes toward wolf management in south-western Alberta, Canada. Environ. Conserv. 41, 303–310. doi: 10.1017/S0376892913000593

Stern, M.J., and Baird, T.D. (2015). Trust ecology and the resilience of natural resource management institutions. Ecol. Soc. 20:14. doi: 10.5751/ES-07248-200214

Stern, M. J., and Coleman, K. J. (2015). The multidimensionality of trust: applications in collaborative natural resource management. Soc. Nat. Resourc. 28, 117–132. doi: 10.1080/08941920.2014.945062

Swaminathan, V., and Moorman, C. (2009). Marketing alliances, firm networks, and firm value creation. J. Mark. 73, 52–69. doi: 10.1509/jmkg.73.5.52

Tonidandel, S., and LeBreton, J. M. (2011). Relative importance analysis: a useful supplement to regression analysis. J. Bus. Psychol. 26, 1–9. doi: 10.1007/s10869-010-9204-3

Tonidandel, S., and LeBreton, J. M. (2015). RWA web: a free, comprehensive, web-based, and user-friendly tool for relative weight analyses. J. Bus. Psychol. 30, 207–216. doi: 10.1007/s10869-014-9351-z

Vanneste, B. S., Puranam, P., and Kretschmer, T. (2014). Trust over time in exchange relationships: Meta-analysis and theory. Strat. Manag. J. 35, 1891–1902. doi: 10.1002/smj.2198

Vaske, J. J. (2010). Lessons learned from human dimensions of chronic wasting disease research. Hum. Dimens. Wildlife 15, 165–179. doi: 10.1080/10871201003775052

Vaske, J. J., Absher, J. D., and Bright, A. D. (2007). Salient value similarity, social trust and attitudes toward wildland fire management strategies. Hum. Ecol. Rev. 14, 223–232.

Wagner, S. M., Coley, L. S., and Lindemann, E. (2011). Effects of suppliers' reputation on the future of buyer-supplier relationships: the mediating roles of outcome fairness and trust. J. Supply Chain Manag. 47, 29–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-493X.2011.03225.x

Wald, D. M., Nelson, K. A., Gawel, A. M., and Rogers, H. S. (2019). The role of trust in public attitudes toward invasive species management on Guam: a case study. J. Environ. Manag. 229, 133–144. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2018.06.047

Winter, G., Vogt, C. A., and McCaffrey, S. (2004). Examining social trust in fuels management strategies. J. Forest. 102, 8–15.

Young-Ybarra, C., and Wiersema, M. (1999). Strategic flexibility in information technology alliances: the influence of transaction cost economics and social exchange theory. Org. Sci. 10, 439–459. doi: 10.1287/orsc.10.4.439

Zaheer, A., and Harris, J. (2006). “Interorganizational trust,' in Handbook of Strategic Alliances, eds O. Shenkar and J. J. Reurer (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications), 169–197. doi: 10.4135/9781452231075.n10

Zaheer, A., McEvily, B., and Perrone, V. (1998). Does trust matter? Exploring the effects of interorganizational and interpersonal trust on performance. Org. Sci. 9, 141–159. doi: 10.1287/orsc.9.2.141

Zaheer, A., and Venkatraman, N. (1995). Relational governance as an interorganizational strategy: An empirical test of the role of trust in economic exchange. Strat. Manag. J. 16, 373–392. doi: 10.1002/smj.4250160504

Zhang, C., Cavusgil, S. T., and Roath, A. S. (2003). Manufacturer governance of foreign distributor relationships: do relational norms enhance competitiveness in the export market? J. Int. Bus. Stud. 34, 550–566. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8400051

Zhang, C., Viswanathan, S., and Henke Jr., J. W. (2011). The boundary spanning capabilities of purchasing agents in buyer–supplier trust development. J. Oper. Manag. 29, 318–328. doi: 10.1016/j.jom.2010.07.001

Keywords: organizational trust, stakeholder trust, meta-analysis, reputation, collaboration

Citation: Ford JK, Riley SJ, Lauricella TK and Van Fossen JA (2020) Factors Affecting Trust Among Natural Resources Stakeholders, Partners, and Strategic Alliance Members: A Meta-Analytic Investigation. Front. Commun. 5:9. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2020.00009

Received: 04 September 2019; Accepted: 31 January 2020;

Published: 19 February 2020.

Edited by:

Kristina M. Slagle, The Ohio State University, United StatesReviewed by:

Sue Schroeder, University of Minnesota Twin Cities, United StatesKaren M. Taylor, University of Alaska Fairbanks, United States

Copyright © 2020 Ford, Riley, Lauricella and Van Fossen. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: J. Kevin Ford, Zm9yZGprQG1zdS5lZHU=

J. Kevin Ford

J. Kevin Ford Shawn J. Riley

Shawn J. Riley Taylor K. Lauricella1

Taylor K. Lauricella1 Jenna A. Van Fossen

Jenna A. Van Fossen