94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Commun., 28 January 2020

Sec. Science and Environmental Communication

Volume 5 - 2020 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomm.2020.00001

This article is part of the Research TopicCritical Approaches to Climate Change and Civic ActionView all 10 articles

This paper investigates climate change activism among sportsmen and sportswomen, or hunters and fishers—a politically conservative group with historically deep roots to environmental conservation. Recently members of this community have created an NGO that focuses solely on climate change action—Conservation Hawks—and several other long-standing organizations have begun to include climate communication and activism within their mission. This article draws on fieldwork conducted throughout the rural western U.S., including ethnographic interviews with sportsmen/sportswomen, participant observation in hunter education courses and conservation events, and publicly-available media produced by hunting-oriented conservation organizations. Using an ethnographic and discourse analytic approach, I find that three primary discursive practices are particularly important within hunting and fishing community—a performed closeness to wildlife and wild places, a privileging of experiential and embodied epistemologies, and a valorization of the past wilderness. In both interviews and sportsmen-oriented media, these discourses can be drawn on when creating doubt and climate skepticism. Increasingly, however, activist groups use the same rhetorical strategies to promote climate change action. I argue that such shared discursive practices can thus mobilize collective identities, challenge political polarization, and create new political subjectivities around climate change in the rural western United States. I also argue that these discursive practices shape the actions portrayed as reasonable responses to the climate crisis within this community. This analysis thus illuminates climate activism within an understudied group, showing the depth of the civic movement on climate change. It also specifically highlights the importance of shared discursive practices to both climate skepticism and climate activism among one politically-conservative group in the United States, rural white hunters, and fishers.

As the impacts of a warming climate are increasingly felt around the world, a number of social movements have arisen to address the urgent need for action. Scholars of the environmental social sciences have thus become more and more interested in describing environmental social movements and civic action on several levels: their demographics (Tindall et al., 2003), the framing and other rhetorical strategies used (Alkon et al., 2013; Levy and Zint, 2013), the cognitive and affective precursors of activism (Roser-Renouf et al., 2014; Bamberg et al., 2015), and their efficacy (Han and Barnett-Loro, 2018). This research on climate change activism, however, has often focused on large movements, or those receiving the most media attention (Cox and Schwarze, 2015; Doyle et al., 2017). The urgency of the climate crisis, however, has led to climate change activism and social movements arising in many more contexts than those that are well-studied, and this article aims to analyze one such movement, that emerging among rural hunters and fishers in the United States. This paper thus endeavors to broaden our understanding of the civic movement for climate change action by examining community-based climate change activism among a historically politically-conservative community—sportsmen and women in the western United States.

Sportsmen and women in the U.S. are a community of people who view hunting and fishing activities as a central part of their identity. In addition, sportsmen portray a strong affiliation to firearms, a connection to the outdoors, an interest in conservation, and—although a small but growing number are not white men—an orientation to rural white masculinity. Due in part to links between rurality, gun culture, and conservative political ideology in the United States, sportsmen and women have primarily been associated with politically-conservative parties and policies (National Wildlife Foundation, 2012). They have also, however, long held themselves to be dedicated conservationists, and in fact there are a number of sportsmen-run and -funded non-governmental organizations that complete conservation-related projects throughout the United States. The affiliation of environmentalism and left-wing political ideology in the United States has caused sportsmen and women to feel distanced from the goals of the larger environmental movement, however, and many contemporary hunters and fishers view environmentalists as misguided, lacking a true understanding of the environment they are trying to protect. Climate change skepticism has also been widespread within this community, which is largely comprised of older white men. According to a U.S. Department of Fish and Wildlife's 2011 survey, over 90% of those who purchased hunting licenses in that year were men, and 96% were white. The prevalence of climate skepticism within the community is also exacerbated by the polarized perception of the climate crisis in the United States by partisan affiliation (Dunlap et al., 2016).

Recently, however, there has been a growing social movement among hunters and fishers for climate change action. Members of the hunting and fishing community have created an NGO that focuses solely on combatting climate change, called Conservation Hawks, and several other long-standing organizations have begun to include climate communication and activism within their missions. This article analyzes the emergent climate action movement within the hunting and fishing community from an ethnographic and discourse analytic framework. These methods allow for the analysis of micro- and macro-levels of linguistic structure and can illuminate how identities are created and negotiated through the discourses surrounding hunting and fishing (Bucholtz and Hall, 2005; Fairclough, 2013). Not only are hunters and fishers a large and historically-active group in conservation activities (Altherr and Reiger, 1995), but their ties to both political conservatism and environmental conservation demonstrate the importance of community-level analyses of conservation discourses and activism, which can be overlooked in broader approaches.

Furthermore, hunters and fishers in the United States have a long history of impacting U.S. conservation and are very engaged in the contemporary dialogues around the management of wildlife and wild lands (Reiger, 1975). Sportsmen are a politically-important group in the western, less-populated states, and have shown, through collective action, that they can impact public policy debates, such as the one surrounding the federal ownership and management of lands within the U.S. (Randall, 2019). This community therefore illustrates the potential of climate change activism which arises out of other movements through the mobilization of shared identities. By examining the discursive practices of an emerging climate change movement within an already politically-active community, such as hunters and fishers, this paper endeavors to show the potential for communication practices to be a “site for performing engagement” with climate change politics (Carvalho et al., 2017), which can also set the stage for further understanding how the historical context of collective action, in this community, can “translate opinion and action into political power,” as called for by Han and Barnett-Loro (2018, p. 2).

The paper proceeds as follows. I first briefly review the scholarship on identity and environmental practices and ideologies, describe the conservation movement within the hunting and fishing community, and explain the ethnographic context and the process of data collection and analysis taken in this study. I then analyze the mobilization of three discursive practices fundamental to the hunting and fishing community—the portrayal of closeness and connection with the more-than-human world; the privileging of embodied and experiential knowledge; and the prioritization of the wilderness past—within discourses of climate skepticism and climate action. I next discuss the potential for such discursive practices to create new political subjectivities through the mobilization of the shared hunting and fishing identity and discuss what that means for the climate change solutions pursued by hunters and fishers. I find that these shared practices form the basis of both discourses of climate skepticism as well as climate activism within this politically-conservative group. In addition, I argue that the use of such shared discursive practices within this community illustrates the potential of these practices to mobilize collective identities, challenge political polarization, and create new political subjectivities around climate change in the rural western United States.

Much scholarship has examined the relationship of individual identities to environmental beliefs or actions (Sparks and Shepherd, 1992; Sparks et al., 1995; Whitmarsh and O'Neill, 2010; Carfora et al., 2017)—finding that social identity is quite important to these beliefs and actions in a general sense, as well as to those specifically around climate change (Unsworth and Fielding, 2014). In the United States, for instance, researchers have shown that women tend to care about climate change more than men (McCright, 2010), that white men tend to be the least concerned (McCright and Dunlap, 2011), that partisan identification has a large impact (Davidson and Haan, 2012). In addition, scholars have shown that some identification categories—such as the labels “environmentalist” or “activist”—can be important to engagement with climate change politics (Roser-Renouf et al., 2014; Brick and Lai, 2018). With the exception of work on environmentalist and activist identities, however, most research in this area investigates social identity through macro-level demographic classifications, such as age, gender, ethnic or racial identity, political affiliation, and so on, rather than the identity categories that are most meaningful to communities themselves (McCright and Dunlap, 2011; Goebbert et al., 2012; Swim et al., 2018). This type of research can obscure the considerable variation in environmental ideologies and practices that exists within broad demographic categories (Howe et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2018). Furthermore, this research is also limited by assuming “conservation” as a shared concept across communities of practice, even though the meaning of “conservation” has been shown to vary widely across cultures and communities and even within academic work on the topic (Mace, 2014; Colloff et al., 2017). In addition, while much of this research implicitly involves the role of language in the reproduction and transmission of environmental ideologies, few studies explicitly analyze language use beyond thematic or content analysis. Finally, much of this research focuses on individual-level behaviors, and primarily those having to do with consumption and lifestyle, rather than the “political fabric of climate change” (Carvalho et al., 2017), which civic movements endeavor to affect. As scholars of environmental communication examine social movements, scholars have pointed out the need to go beyond the typical analysis of individual actors to understand the formation of collective power within these movements (Han and Barnett-Loro, 2018).

Meanwhile, linguists have long recognized language and communication to be constitutive of identities and social action, but have only just begun to examine collective action contexts (Bonilla and Rosa, 2015) and environmental beliefs and actions (Stibbe, 2014). This article builds on that emerging scholarship by examining the relationship between discursive practices, identity, and environmental activism from an ethnographic and discourse analytic lens, focusing on sportsmen and women, a group which complicates typical macro-level approaches to the relationship of identity and environmental practices. The majority of hunters and fishers, for instance, are older white men who are politically conservative. These identity categories, at the macro-level, have been shown to be less concerned about climate change (McCright and Dunlap, 2011), and less likely to participate in pro-environmental behaviors (Dietz et al., 2002). Sportsmen and women, however, express strong support for environmental conservation—something they portray as fundamental to the hunting and fishing identity—and see themselves as the original conservationists in the United States. They also engage in pro-environmental behaviors, primarily through donating to conservation groups and participating in volunteer activities with those groups. The hunting and fishing community thus challenges traditional macro-level approaches to identity and environmental ideologies and practices, showing the need to examine the discursive practices of local groups within broader research on environmental social movements. Furthermore, sportsman climate activists use a number of rhetorical strategies to explicitly challenge the polarization of climate change views within the hunting and fishing community. An analysis of the discursive practices of climate activists within this politically-conservative group can add to understandings of ways in which political polarization can be disrupted (Lucas and Warman, 2018) and new political subjectivities can be created around climate change action in the rural western United States.

As a community, hunters and fishers have a long history of participating in collective action for the conservation of wildlife and wild lands. In fact, the current version of the “sportsman” identity arose near the end of the nineteenth century primarily as a “hunter/naturalist”—someone who was both a student of nature as well as a hunter and/or fisher (Altherr and Reiger, 1995). At that time, the United States was experiencing extreme losses in wildlife numbers. Of the earlier 60 million American bison, for example, only a few hundred remained (Jones, 2015). The hunter/naturalist persona thus, from its earliest instantiation, included a strong focus on understanding wildlife and advocating for their conservation, which coincided with and reinforced early efforts to conserve these wildlife populations. Theodore Roosevelt, for example, said “All hunters should be nature lovers. It is to be hoped that the days of more wasteful, boastful slaughter are past and that from now on the hunter will stand foremost in working for the preservation and perpetuation of wild life” (Jones, 2015, p. 278). A number of ideals emerged from these early conservation efforts, contemporarily referred to as the North American Model of Wildlife Conservation, and are still used by governmental regulatory agencies as well as citizen conservation groups (Altherr, 1978; Geist et al., 2001; Organ et al., 2012). These principles banned the sale of game meat and prioritized management for the maintenance of healthy wildlife populations. Hunter/naturalists of the time also took several other actions in order to promote the conservation of wildlife, which included lobbying for the creation of national parks and promoting the Pittman-Robertson Act of 1937—a law imposing an 11% tax on firearms and other hunting equipment. These efforts have been quite effective, according to members of the community, providing funding for state Divisions of Fish and Wildlife and some federal lands administrations, among other things, and leading to a significant recovery in wildlife populations. The Pittman-Robertson Act has been amended several times, but still remains in effect, generating hundreds of millions of dollars a year that supporters say allow for substantial habitat preservation and other conservation efforts (United States Department of the Interior, 2018).

Hunter/naturalists of the early twentieth century drew on and valorized indigenous knowledge, but the constructed identity of the sportsman was a fundamentally white and middle-class identity. Indigenous hunters were thus not seen as hunter/naturalists (Vibert, 1996; Jones, 2015), and native American subsistence hunters were portrayed as being overly “savage,” a representation that was aligned with racist ideologies of the time. Upper middle-class hunters positioned themselves as ethical hunters—“true” sportsmen—and in opposition to those they represented as insufficiently moral: market hunters, subsistence hunters, and wanton adventurers. Through this contrast, hunter/naturalists portrayed themselves as the true champions of wildlife conservation, justifying policies changing hunting access throughout the nation, including the removal of lands from Native American control for wildlife conservation purposes (Reiger, 1975; Dray, 2018).

Contemporary hunters and anglers in the United States, sometimes called sportsmen (a term which is often used to refer to both men and women, and less commonly used in the feminine form, “sportswomen”), are a group of people for whom hunting and fishing forms a large part of their identity. Although overall numbers of hunters in the U.S. have declined since 1980 (Larson et al., 2014), which is a concern for many within the community, there were 11.5 million people who participated in hunting activities in the United States in 2016 (United States Fish Wildlife Service, 2016), and 35.8 million people who fished. In order to get a hunting license in the United States, applicants must first pass a hunter education course, which is administered on a state level but is semi-standardized across states. The courses are generally instructed by volunteers from the community, and the curriculum was developed collaboratively between the National Rifle Association (NRA) and state wildlife management institutions. In addition to the education process, the group is unified through media outlets, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and community events. Overall, the hunting and angling community tends to be politically conservative (National Wildlife Foundation, 2012), stemming in part from an affiliation with rural areas as well as a strong orientation to firearm access and ties to the NRA. At the recent Hunting and Conservation Expos in Salt Lake City, Utah, for instance, many keynote speakers had been, or continued to be, a part of Donald Trump's presidential administration, such as Ryan Zinke in 2017 and Donald Trump Jr. in 2018. In 2019 Donald Trump Jr. also spoke along with the Republican governor of Utah. Several other organizations, such as Ted Nugent's Hunter Nation and the NRA, also work to strengthen the links between the hunting identity and right-wing political ideologies. Despite associations of mainstream environmentalism with the political left wing, however, hunters and anglers strongly assert their commitment to conservation and their legacy of positive impacts on wildlife communities. In addition, recently several organizations within the community have opposed certain aspects of the U.S. Republican party's policy platform, such as challenging the initiative to transfer ownership of federally-held public lands to state or private ownership.

The community has also given birth to an emerging movement for climate change action. In 2009, a number of hunting- and fishing-oriented NGOs created a report called “Beyond Season's End” for dissemination to congress as well as the public. This report detailed the current and predicted effects of climate change on wildlife species and hunting and fishing opportunities and described suggested plans for both mitigation and adaptation. Since that report, many longstanding groups with extensive memberships, such as Ducks Unlimited, the National Wild Turkey Federation, Trout Unlimited, the Wild Sheep Foundation, Backcountry Hunters and Anglers, the Theodore Roosevelt Conservation Partnership, and so on, have begun to focus more on climate change. Their efforts include communication—creating media, educating hunters, lobbying politicians, and urging their members to speak to their elected officials—opposition to new oil and gas leases on public lands, and adaptation measures, such as fire prevention, wetland creation/restoration, and drought protection. Moreover, the NGO Conservation Hawks was founded in 2011 by a Montana-based hunter and fisher named Todd Tanner. Conservation Hawks pursues the exclusive goal of mobilizing sportsmen to urge action on climate change, has conducted workshops around the mountain west, especially in Montana, and has created extensive media which communicates the risks of climate change to hunters, including a documentary that recently premiered on the Outdoor Channel.

This article draws on fieldwork I conducted throughout the rural western U.S. From 2015 through 2019 I conducted semi-structured ethnographic interviews with 42 hunters, a method which involved conversational interviews that took place in naturalistic settings and ranged from informal exchanges to formally-arranged audio-recorded dialogues (Byram et al., 1996). In addition, I carried out participant observation in hunter education courses, a youth pheasant hunt, and conservation events and fundraising activities. Of the hunters who participated in this study, the majority were men (32 of 42), white (40 of 42), and over 50 years old (22 of 42), a demographic breakdown which is typical of the broader hunting community: the U.S. Department of Fish and Wildlife's 2011 survey found that over 90% of those who purchased hunting licenses in 2011 were men, and 96% were white. Participants were largely recruited either through their participation in hunting mentorship groups or via the snowball sampling method. The hunting mentorship NGO through which I recruited many of my participants, the First Hunt Foundation, maintains publicly-available lists of active volunteers who are willing to serve as mentors. After receiving permission from the NGO's director, I contacted volunteers to ask if they would be willing to be interviewed. During interviews, I also asked if participants knew others who would be interested in participating. While many of the younger hunters who participated in my interviews were more formally-educated than the older generation—having completed undergraduate or advanced degrees in natural sciences—almost all affiliated with the term sportsman, and most were active members of hunting-oriented NGOs. After collecting over 60 h of audio and video recordings of interviews and hunting activities, several research assistants and I coded all of the interviews and field notes for organizing themes. We first created an index of the recordings, a time-stamped outline of each interview which covered content as well as salient linguistic resources. From this outline, we then used a process of open-coding to collect the themes that emerged inductively during data collection and the activity of indexing interviews and reflecting on field notes. During this process, we identified several key recurring ideas. The list of key codes ultimately included: perceived anti-hunter sentiment/lack of understanding from non-hunters; indigeneity; gender; rurality vs. urbanity; the importance of conservation; hunting ethics; age and generation, distance/closeness to nature, nostalgia for the past wilderness; authentic hunter identity; relationships to food; relationships to the environment/wildlife/landscape; and the importance of embodied experience. From this list of codes, I selected the key themes for the analysis presented here, focusing specifically on sections of the interviews that dealt with climate change. I then conducted a more focused analysis around the three themes that emerged as most important during these discussions: closeness to nature, embodied experience, and nostalgia for the wilderness past. I selected crucial segments in which these themes emerged for transcription and close discourse analysis. I then analyzed these segments with the following research questions in mind: (1) how is the sportsman identity constructed and mobilized through its discursive practices? and (2) how are these discursive practices mobilized in the context of climate skepticism as well as climate action?

While ethnographic interviews illuminated the discursive foundations of the sportsman identity, within the discussions of climate change, participants provided mostly illustrations of climate denial discourses. The majority of my interviewees, like many older rural, white men (Dunlap et al., 2016), were still skeptical of anthropogenic climate change. Among the sportsmen who were concerned about the issue—many of those under 40 years old, for instance—several recommended that I look at a few NGOs which have been focusing at least part of their efforts on climate change recently and which function as the center of climate change activism within the hunting and fishing community. To that end, I collected publicly-available media produced about climate change by the recommended organizations—the conservation-related NGOs Conservation Hawks, the Theodore Roosevelt Conservation Partnership, Backcountry Hunters and Anglers, and Ducks Unlimited. My research assistants and I conducted a similar coding process for this media data, focusing especially on themes that had already emerged as relevant during ethnographic interviews.

Conservation Hawks was founded in 2011 by a Montana sportsman with the exclusive goal of communicating climate science to other hunters and fishers. As part of this mission, the organization holds workshops, creates media, and urges community engagement with politicians around the topic of climate change. The second organization, the Theodore Roosevelt Conservation Partnership, has existed since 2000 and works on a number of conservation issues of concern to the hunting and fishing community, such as the protection of public lands, hunting access on federal lands, the protection of wildlife species, and recently, climate change mitigation and adaptation. To those ends, TRCP is primarily a lobbying institution, working with members of congress to represent the interests of sportsmen and women. Backcountry Hunters and Anglers and Ducks Unlimited, in contrast, are both membership organizations that work to protect wildlife and their habitats, both at the policy level and the local, material level. All of these NGOs use several social media platforms as well as producing media and distributing it through other formats, such as YouTube or print magazines.

In order to conduct an analysis of the climate change activist discourses produced by these organizations, I collected climate change-focused media from the NGOs' websites and social media, especially Instagram accounts, as Instagram is the most popular platform for hunting personalities and brands. All materials collected for analysis were publicly-available, but I obtained consent for any media that would be reproduced. Social media interactions, because they allow for responses to the content, proved to be an especially rich site in which to observe interactions surrounding climate change activism and the ways in which community members take stances about the issue. I then analyzed these communications as well as the responses to that media (when available), focusing on the discursive strategies which had previously emerged as salient within the ethnographic interviews.

Across both interviews and media, I take a discourse analytic approach to analyzing the constitution of the sportsman identity—seeing each act of communication as a form of stance-taking that reinforces and reinscribes identities (Du Bois, 2007). This framework holds identities to be dynamic and created from below, rather than simply imposed from above (cf. Kahan et al., 2012), and it draws heavily on critical discourse analytic understandings of how subjects position themselves with respect to social and political issues through their communication practices (Fairclough, 1990).

My analysis is also informed by my previous experiences with the hunting and fishing community. I grew up as part of a family that occasionally participated in hunting activities and in a rural area where hunting is very common. I have never hunted myself, but as a researcher who identifies as a part of a rural community, and in some ways affiliated with sportsmen and women, I aim to create an analysis which is a respectful representation of climate change activism within the hunting and fishing community, while, at the same time, calling attention to potentially problematic discourses and practices. To that end, throughout the research planning and analysis process, I discussed the findings and interpretations with both participants and other hunters and fishers. I also intend for my findings to be shared with members of the community as well as academic audiences.

The discursive foundations of the sportsman identity have been discussed at length elsewhere (Herman, 2014; Love-Nichols, 2020), but for the purposes of this article, it is important to note that that the sportsman identity is closely related to other white, rural, “country” identities (Johnstone, 1999; Herman, 2014), but is distinguished discursively in three main ways. The first foundation of the sportsman identity is the ideology that hunters and fishers have a strong connection to the outdoor world—in contrast with others living in a modern world—because of the activities of hunting and fishing, which allow them to still be a part of the “outdoors.” Building from this, the second ideology constituting the sportsman ideology is the importance of experiential and embodied knowledge, rather than “removed” scientific ways of knowing. Lastly, the hunting and fishing community is constructed through a valorization of the wilderness past within environmental communications.

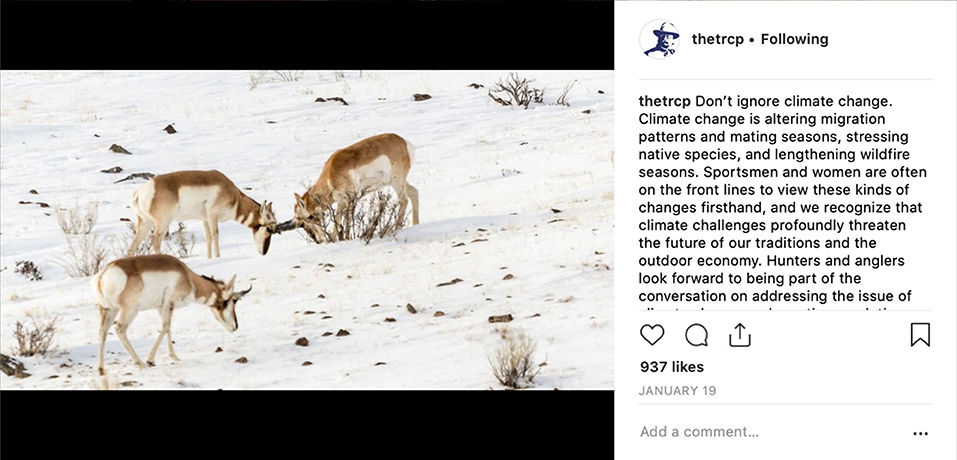

These discursive foundations are drawn on in both climate change skepticism and the emerging climate change movement within the hunting and angling community. The next few examples will illustrate how these constitutive discursive practices are mobilized in the context of climate skeptic discourses, which are historically common among rural, politically-conservative communities (Dunlap et al., 2016). The ideology of hunters' closeness to nature, for instance, is often drawn on in opposition to environmentalists, who were described by interviewees as people who meant well but were misled due to their lack of true connection with the outdoor world. An illustration of the mobilization of this ideology within climate change discourses occurs in the first example, in which a commenter expresses their doubt that humans could be causing the effects of climate change because they are a “part of nature” rather than above it. This comment was posted on January 19, 2019, in response to an Instagram post by the Theodore Roosevelt Conservation Partnership (Figure 1, discussed in detail later on), which encouraged climate change action by hunters. In the original post, the TRCP argues that climate change is “altering migration patterns and mating seasons, stressing native species, and lengthening wildfire seasons,” and urges hunters to not ignore the problem but to be “part of the conversation addressing the issue.” In response, the commenter, jd13756, expresses that those who believe in anthropogenic climate change must consider themselves “above” and “not part of nature,” a view which they consider ludicrous.

Figure 1. Instagram post by the Theodore Roosevelt Conservation Partnership (https://www.instagram.com/p/Bs08_QXDPIb/; used with permission).

jd13756: Comon bro?! That's really all I can say. So complex. Only humans can be so arrogant to think they are above and not part of nature and as a result are the cause of “climate change”.

(comment on TRCP Instagram post Jan 19, 2018)

This comment showcases a common trend among mainstream climate change skeptical discourses, which is to portray humans as incapable of causing changes to global climate patterns. While this ideology is often found in discourses outside the hunting community, the commenter here specifically links their view to the ideology that humans are a “part of nature” and that to think otherwise would be “arrogant,” thus challenging climate scientists' demarcation rhetoric (Taylor, 1991).

Similarly, many sportsmen also drew on the second discursive foundation of the hunting identity—privileging experiential epistemologies—when expressing skepticism about anthropogenic climate change in both ethnographic interviews with me as well as opposition to climate change activism on social media. For example, in one interview, when asked about whether hunters consider climate change to be a problem, an older hunter in western Washington answered in the following way:

What do you call climate change in your world. Global warming, yeah the earth is tipping1. Read back if you study any type of earth history, it's happened like four times, the earth has flipped over. Everything that was warm is cold. Everything that's cold is warm. (Interviewer: So it's like some sort of, like a natural cycle?) It's a natural cycle. You know. We can study it. We can predict it. We can blame somebody. We can't stop it. There's nothing you can do but bitch about it. I'm aware of that because I fish. I salmon fish. I'm aware that the fish are coming in later and later every year. The first are later, because the silvers should be in by now. They're not here yet.

In his response, this interviewee, who described himself as very politically conservative, portrays climate change as an event which has occurred before and that is attributable, in his opinion, to the earth having “flipped over.” The hunter does observe changes in fish behavior, and further seems to suggest that he has experienced changes in temperatures by saying “global warming, yeah the earth is tipping.” Although the explanations he gives for these observations can be perceived as farfetched, he draws primarily on his own experiences as the foundation for his beliefs, saying “I'm aware of that because I fish.” He agrees with my clarification that he's attributing climate change to “some sort of, like a natural cycle” and produces an understanding of climate change as not created by human activity, as taking place on a very long timescale, and as, at least at the moment, primarily impacting salmon and salmon fishers. The hunter's construction of climate change also positions himself, and by extension, other hunters and fishers, as closest to, and most knowledgeable about, a changing climate. He contrasts what climate change means in “your world”—the urban, presumably politically-liberal world of a university—with his world, which he portrays as closest to the salmon. What he knows about climate change, he says, is due to his contact with fish, and from this perspective, he understands that humanity does not have the power to impact “natural cycles” such as climate change. He draws a parallel between what “we” can do: “study it,” “predict it,” “blame somebody;” contrasting that with what we cannot do: “stop it.” He then shifts into the generic second person to discuss what “you” can do, which is “bitch about it.”

Likewise, the commenter in the next excerpt, who is also responding in opposition to the above-mentioned Instagram post by the Theodore Roosevelt Conservation Partnership (Figure 1), draws on embodied and firsthand experience to dispute the renewability of wind power, saying that they “see wind turbines … every day” and they are “not 100% renewable.”

geojohn.hutch: I see the wind turbines in my backyard every day and they surely are not 100% renewable. The problem is that gigantic footprint where wind farms exist will NEVER be the same. I'd rather see the co2 rise in ppm (PPM!) within the atmosphere before I see our land go to waste so California can buy expensive electricity and stay in deficit and never change the carbon cycle anyways.

(comment on TRCP Instagram post Jan 1,9, 2018)

While in this case the commenter may be interpreting the term “renewable” differently than in the scientific definition, potentially understanding it to mean something like “having no impact,” they do it by drawing on their own close embodied experience of seeing wind turbines in their backyard every day. By emphasizing that they personally experience the wind turbines every day, they reinforce their claim to understanding whether or not such structures are “100% renewable.” Similarly to the earlier interviewee, this commenter also portrays humans as unable to affect the global climate, saying that California can spend as much money as they want but will “never change the carbon cycle anyways.” The commenter also contrasts harms they can experience visually, like “our land go[ing] to waste,” with harms that are less available to embodied experience, such as carbon dioxide concentrations rising. They highlight the difficulty of experiencing carbon dioxide increases by first writing “ppm” in lower case, then repeating it in parenthesis in all caps with an exclamation point “(PPM!)” to suggest that it is ridiculous to be concerned about a substance that is measured in parts per million.

Finally, many interviewees and social media commenters also used the third discursive foundation of the hunting identity, a past-focused lens, in their responses to my question about whether they were concerned about climate change. One interviewee, for instance, said the following:

Well, I don't disagree that the environment's changing. I mean, the climate's changing. But don't forget in 1900, what was that a hundred and twenty years ago, Niagara Falls froze solid. You've got pictures on the internet, of people standing, on the ice at the bottom of Niagara Falls. In 1900 … So. You know in a hundred and twenty years we-. we haven't seen it freeze again, but it's been pretty cold in the winters around here.

In this response, the interviewee calls back to an event in 1900, portrayed as extraordinary, to suggest that the climate has been changing over a longer time than climate change activists suggest. He begins by agreeing that the environment is indeed changing, though he sets up his opposition to anthropogenic climate change by specifying that he does not disagree with only that part of my question. He then emphasizes a freezing event in 1900 which has not been repeated, pointing out that in the next 120 years Niagara Falls has not frozen again, as evidence that the observed changes in the environment are actually a part of some natural cycle which has been ongoing. An appeal to past events was a common climate skeptic discourse among my interviewees, functioning within one of the most prevalent climate denial discourses throughout the United States—the argument that climate change is a “natural cycle,” rather than a problem caused (and presumably solvable) by humans.

Past-focused discourses also often occur through appeals to heroic past hunters. Online commenters, for instance, draw on this type of nostalgia to construct their critiques of climate change concern. For example, in another reply to the Theodore Roosevelt Conservation Partnership's Instagram post (Figure 1), one commenter draws on the historical figure of Theodore Roosevelt to express skepticism about the phenomenon they describe.

rockymtnoutfitters:  really trcp…TR would slap you with with some sense right now

really trcp…TR would slap you with with some sense right now

(comment on TRCP Instagram post Jan 19, 2018)

In this case, the commenter, rockymtnoutfitters, expresses familiarity with Roosevelt by shortening the name to “TR” and arguing that Roosevelt would disagree strongly with the activist sentiments of the post. Roosevelt is a highly regarded figure in the hunting and fishing community, as seen in the invocation of his name and image by NGOs such as the Theodore Roosevelt Partnership, and he is often portrayed as the first true “sportsman” and the original conservationist. The commenter in this post specifically draws on the figure of Roosevelt in connection with the name of the posting organization, challenging the NGO's invocation of Roosevelt in their name and suggesting that Roosevelt would not, in fact, agree with their actions.

Nostalgia has long been identified as a discursive practice that is particularly effective at mobilizing ideas of shared identity (Boym, 2007), and it has been previously shown to be a prevalent rhetorical strategy in rural U.S. conservative communities (Rich, 2016). In other contexts, however, scholars have identified nostalgia as a powerful and common discursive practice for both progressive and conservative causes (Boym, 2007). As Tannock (1995) points out, “Nostalgic narratives may embody any number of different visions, values, and ideals. And, as a cultural resource or strategy, nostalgia may be put to use in a variety of ways” (p. 454). Within linguistic anthropology, the mobilization of a time-space unit is often analyzed through the lens of the chronotope (Bakhtin, 1981), which illustrates that conceptions of time, space, and figures of personhood are never truly separable. As Boym (2007) recognizes, the yearning for a time or place is often about much more than just a place or a time in the narrow sense: “nostalgia is about the relationship between individual biography and the biography of groups or nations, between personal and collective memory” (p. 9). In this community, the nostalgic framing of climate change works to tie the sportsman identity to a less modern, less urban time, which is then mobilized both for anti- and pro-environmental stances (as seen in the next the next section).

In the previous section, I illustrated how the three discursive foundations of the sportsman identity—a constructed closeness to wildlife and wild places, a privileging of experiential and embodied epistemologies, and an idealization of the past wilderness—are mobilized in the service of the denial of anthropogenic climate change among hunters and fishers in the western United States. The same discursive practices illustrated above, however, are also mobilized within the nascent climate action movement to urge engagement on the part of hunters and anglers. The next section shows the use of a performed closeness to nature, valorization of experiential epistemologies, and an orientation toward the rural past within the climate change messages created by hunting conservation NGOs.

Sportsmen's perceived closeness to the natural world, for instance, as well as a nostalgic lens, can be seen in a climate change PSA created by the Theodore Roosevelt Conservation Partnership.2 This video was created in 2012 as part of the “Beyond Season's End” initiative (detailed above) and explains several changes that climate change will cause to wild life and lands in the western United States. It also argues that carbon emissions must be reduced and urges sportsmen to contact their elected officials. The video begins with a view of the moon from space. Sounds of ducks quacking can be heard and then a recording of Neil Armstrong saying, “One small step for man, one giant leap for mankind.” Then, in a voice reminiscent Walter Cronkite-style news anchors, the narrator begins to discuss climate change-related facts. The text suggests repeatedly that sportsmen are best-positioned to see the effects of climate change, because, according to the video, they are the ones “who are most often out on the land,” and are “often some of the first to notice the effects that our changing climate is having on hunting and fishing opportunities.”

Similarly, in the much-disputed Instagram post in Figure 1, the Theodore Roosevelt Conservation Partnership implores hunters not to ignore climate change. The post provides several reasons why hunters, specifically, should care about climate change's effects, and then argues that hunters and anglers should be “a part of the conversation on addressing the issue.”

Instagram post by the Theodore Roosevelt Conservation Partnership3 (used with permission).

The photo in the post depicts several pronghorns on a snowy field, and the accompanying text argues that hunters and fishers should not ignore climate change. It emphasizes the close relationship between sportsmen and women, by saying that “sportsmen and women are often on the front lines to view these kinds of changes firsthand,” and contends that hunter and fishers' close relationship to nature is precisely why they should not ignore climate change, since they, and the “future of [their] traditions” will be profoundly affected.

Relatedly, hunter climate activists also draw on their embodied and participatory knowledge in climate change media aimed at other members of the community. In a short video created by the NGO Conservation Hawks, for instance, several hunters sit around a fire and reminisce about experiences they have had in better times.4 In the film, the actors emphasize their personal experience both prior to what they see as the effects of climate change, and after, when the effects they mention—fires, storms, and dying forests—have made it impossible for them to continue to hunt in the same places that they used to. The PSA exclusively privileges participatory and embodied epistemologies; it does not mention any climate science whatsoever. If viewers go to the organization's website, they will find some links to scientific studies, but the majority of the NGO's site focuses on highlighting sportsmen's personal experiences with the effects of a changing climate. In an interview, the director of Conservation Hawks also recognizes the privileging of participatory epistemologies as an effective rhetorical strategy, but states that he hopes sportsmen will begin to see that their knowledge aligns with that generated by scientific epistemologies. He says, “I think it helps that people are hearing from their peers. When other hunters and other anglers are saying, “hey—you know what, we are seeing this. It jogs perfectly with the science. It's exactly what the scientists are telling us” (O'Brien, 2015).

Lastly, the media produced by hunter climate change activists also situates itself largely in the rural past, instilling sadness for this lost bygone time, rather than fear for an apocalyptic future, like much other climate change media (Killingsworth and Palmer, 2012). For example, both of the previous media examples construct their concern for climate change through a nostalgia for past wildernesses. In the Conservation Hawks video, this occurs through the reminiscence about past hunting experiences, which draw heavily on a positively-evaluated remembered rural past. One man, for instance, reminisces, “Remember when we chased that monster whitetail up Bear Creek?” and another responds, “Man, those were the days.” During the first portion of the video, when the three men are recalling past hunting experiences, the conversation is punctuated with laughter and smiles. Halfway through, however, the tone of the conversation changes, with one man saying, “Before the droughts moved in.” The next several lines involve the men taking turns sadly describing a negatively evaluated present in which “the beetles ate the forest” and “everything burned,” there are numerous “crazy damn storms,” and they no longer have anywhere to hunt. By contrasting the positive nostalgia with the hunters' gloom about the present wilderness, the Conservation Hawks video portrays a modern world in which climate change has harmed the wilderness—a chronotope in which the hunters do not fit. The video implies that the hunters' natural context, the time and space in which they belong, is the past they previously described, one in which they were able to fully embody their identity, and which has been taken from them by the ravages of a changing climate.

In the Theodore Roosevelt Conservation Partnership PSA, the valorization of the past wilderness emerges through the idealization of the western United States when the “first explorers laid eyes on it.” The narrator intones, “when you think of Montana's Yellowstone River, the longest free-flowing stream in the lower forty-eight, you imagine cool, pristine waters with trout hiding behind colorful rocks. And when the explorer John Colter first laid eyes on the region, in 1807, that is what it must have looked like.” The text then contrasts this positively-evaluated rural past with the negatively-evaluated present in which “dryer and warmer weather patterns are having much of an effect across the Rockies. In Oregon, we find that fire, a natural force which is often friendly to nature, has taken on a new meaning, and it's not a good one.” Furthermore, in the Instagram post seen in Figure 1, the Theodore Roosevelt Conservation Partnership constructs a fear for the future through an orientation to past activities, arguing that “climate challenges profoundly threaten the future of our traditions.”

Commenters on social media also participate in this rhetorical practice, drawing on the past, especially figures from the past, in their discussions of climate change. This is especially evident in the following comment (reprinted from above, with response included) and the response to it, a discussion which took place in response to the Theodore Roosevelt Conservation Partnership's well-discussed Instagram post from Figure 1.

rockymtnoutfitters:  really trcp…TR would slap you with with some sense right now

really trcp…TR would slap you with with some sense right now

kirbylinck: I think Teddy would agree.

(comment on TRCP Instagram post Jan 19, 2018)

Here both participants draw on Theodore Roosevelt, positioning the historical conservationist in alignment with their own viewpoints in their debate of this call for action on climate change. In their challenge to the first commenter's skepticism, the second commenter, kirbylinck, also constructs a great familiarity with Roosevelt through the use of the single name, “Teddy.” Kirbylinck then argues that Roosevelt would agree that hunters should take action on climate change, situating their stance as continuing past hunters' long history of wildlife protection and conservation action.

Through the use of the shared discursive practices illustrated in this section—emphasizing the closeness of hunters and fishers to nature, privileging embodied and experiential epistemologies, and creating a past-focused lens—hunters within the emergent movement for climate action draw on their shared identity to construct climate change as an urgent problem of critical importance to hunters and fishers, not just urban environmentalists. These practices can also function to disrupt the polarization of climate change stances within politically-conservative groups, which will be discussed in the next section.

The previous section illustrated the discursive mobilization of their collective identity by sportsmen and hunting institutions in order to express both climate skepticism and to encourage climate action. Hunters and fishers are overwhelmingly white (Herman, 2014), largely conservative (National Wildlife Foundation, 2012), and mostly male (United States Fish Wildlife Service, 2016), all populations that have been shown to be particularly resistant to the acceptance of anthropogenic climate change (McCright and Dunlap, 2011). An emerging climate change movement within this community, however, shows the importance of analyzing community-level identities for understanding environmental action and climate change social movements. Furthermore, this mobilization of the hunter identity for climate action is taking place within a community that already wields a great deal of political power (Randall, 2019) and has an existing political network with a long-term record of effectively lobbying for policies on wildlife management, land use regulations, and firearm ownership. The nascent climate change movement builds from this context, using effective rhetorical strategies from other conservation movements by sportsmen and women. Climate change activists, for instance, draw on this collective identity to create new political subject positionings. In some cases, activists explicitly attempt to depolarize the debate around climate change and other environmental issues within this community, urging sportsmen to engage directly with politicians about the issues, rather than accept the policy positions of elected officials due to their partisan affiliation. This rhetorical strategy has previously been used widely, and effectively, in the support of federally-controlled public lands. The following quote, for instance, is from an article written during the 2018 midterm elections in the United States. In it, the writer for the hunting media website The MeatEater sets the stage for urging readers to vote for politicians who support federally-owned and -managed public lands, whichever party they may belong to.

If those of us who love to hunt and fish were to build the perfect politician, you would think it would be a fairly straightforward exercise. We all need access, healthy ecosystems, plentiful wildlife, and the right to bear arms, rods, and bows. We need to protect our traditions while also letting the non-hunters in on what we do outside. (O'Brien, 2018)

Similarly, during the 2018 midterm elections, another popular hunting figure, Randy Newberg, conducted an interview on his podcast with the Democratic senator from Montana, Jon Tester.5 In the introduction to this interview, he urges his listeners to be more invested in policy and to put less importance on political affiliation—to “get rid of the R, get rid of the D.” He highlights his membership in the collective hunting and fishing identity—saying “I come from the party of hunting, fishing, and public access”—to encourage his listeners to complicate the partisan polarization common in the United States.

I want people to understand maybe a little insight about how things work back there, about how important it is to be involved in policy, and also the fact that, no matter who the candidate, is they work for you, and you can hold them accountable. They might disregard you, and it's more important to make sure that the candidate understands what is your priority, how important these issues are to you, and get rid of the R, get rid of the D, get rid of the whatever. I'm so tired of that, you guys have heard me go on and on about that, that I come from the party of hunting, fishing, and public access. That's the only way I approach it.

This strategy, the mobilization of a collective hunting and fishing identity in order to complicate partisan issues, has already shown success in influencing the public policy surrounding federal lands in the western United States. For example, in 2017 a representative from Utah, Jason Chaffetz, had to withdraw a bill that would have transferred millions of acres of federal land to state ownership after public outcry, much of it from the hunting and fishing community (Gentile, 2017). In addition to supporting the federal ownership and management of public lands, these campaigns set the stage for climate activism as they also often oppose oil and gas leases on that land (Williams, 2019).

In some cases, the creation of new subject positionings has moved from media and institutional discourses into the in-person conversations. One of my interviewees, for example, mentioned his admiration for Steven Rinella, a hunting media figure who often partners with TRCP and uses similar rhetorical strategies to Ben O'Brien and Randy Newberg. The interviewee then echoed their anti-polarizing discourses, saying about climate change, “I can't stand agendas either way to be honest. Like I don't like that it's politicized. I don't think it should be. Science should never be politicized, ever … So it's very sad to me that the perception of climate change or whatnot, is a political motivation and not an objective thought.”6

Optimistically, the use of such complicating discourses by both media figures and individual members of the community illustrates the potential of shared discursive practices to mobilize collective identities and complicate the deliberate polarization of climate change views by right-wing conservative rhetoric. In fact, such discursive strategies do seem to be having an effect, even among some of the climate-skeptical older hunters I spoke to. For example, one interviewee began their response with common climate skeptic discourses, arguing that although the climate is changing (which they know because of their experience hunting elk), these changes are part of a natural cycle that is unrelated to human activities. After about 20 s of expressing their ideas, however, they began to consider the possibility that human-created carbon emissions have been having an impact on the climate:

But it's the natural course of events over thousands of years, things have done. You know the ice came in and then it went back. And now it's coming in, and now it's going back again. So, uh… Granted there's a lot of cars on the road, I thought about that yesterday coming back from [redacted]. It was bumper to bumper for nineteen miles. And that's just on a two-lane highway over here. I-5 and all those—. I mean you think about the number of automobiles that are on the road every day twenty-four hours a day. 46. There's a lot of … stuff, lot of stuff. So … how much impact we are having, I don't know.

After this period, the interviewee relieved the tension by saying “I'll be dead in 20 years so it don't matter [laughter]. I hope not but maybe,” and then pivoted back to their experiential knowledge as a hunter, saying, “So I can testify that there's changes, because of the way the elk season's rutting takes place.” This interviewee's consideration of the effect of human activity on global climate is, while a departure from their earlier stance, also rooted in their direct experience of observing large numbers of cars creating greenhouse gases, a hopeful indication that such discursive strategies may lead to positive outcomes, even among older, extremely conservative white men.

The association of political conservatism, rural white identity, and opposition to environmental movements and regulations within the United States has been created through a great deal of discursive work on the part of right-wing movements and organizations such as the National Rifle Association. These semiotic links have functioned to increase polarization around the issue of climate change and to create the perception that advocacy for climate change mitigation is a stance taken by urban, politically-liberal people. By reinforcing their collective identity through the use of shared discursive practices, however, hunting climate change activists within the nascent social movement are challenging this constructed polarization and building on their previous successes in the area of public lands to mobilize sportsmen and women to engage with their local and national politicians, educate other members of the community, and undertake mitigation projects to protect wildlife and wild lands from the worst effects of a changing climate.

It is important to note that while the mobilization of this collective identity through shared discursive practices has promising implications for climate action in the rural western United States, it can also constrain the solutions that are considered the most reasonable responses to the climate crisis. In this community, for instance, many NGOs already have projects underway to address some effects of a warming planet. The solutions these organizations pursue, however, are shaped by the community's discursive practices. In accordance with the emphasis on closeness with the more-than-human world and a distrust of “removed” environmental science, for instance, the solutions suggested by this community can tend to prioritize adaptation and local policies over mitigation at the level of the nation. Ducks Unlimited, for instance, anticipates rising sea levels which will threaten duck habitat along the coasts. In response, they are purchasing and preserving land slightly inland of the coast, with the expectation that this space can become new wetland once the original habitat is submerged. Other NGOs have undertaken projects installing water features in the desert, to help animals such as big-horned sheep survive prolonged droughts or have participated in fire prevention efforts or habitat restoration after fires occur.

Wildlife Management Institute The Theodore Roosevelt Conservation Partnership (2009), along with nine other hunting- and fishing-focused institutions, created the aforementioned report called “Beyond Season's End.” This booklet detailed the threats of climate change to wildlife and wild lands and focused on the benefits of protecting these resources from the anticipated effects of a changing climate. The report also provided detailed project plans and cost estimates for adaptation proposals. According to this report, tackling the climate crisis entails:

“Reducing the loss of wildlife and wildlife habitat resulting from climate change will require these agencies to adopt new strategies that: 1) assist wildlife through actions such as acquiring land for migratory corridors, restoring habitats and assessing the vulnerability and monitoring the condition of wildlife populations; 2) develop landscape-level conservation approaches, particularly those that are habitat-based; 3) partner with parties across jurisdictional boundaries to encourage consistent management practices and achieve landscape-level conservation objectives; 4) engage in efforts such as biological carbon sequestration projects and carbon emission reduction programs to mitigate the consequences of climate change” (p. 11).

The goals laid out in this report are organized by the category of fish or wildlife they are meant to protect. For fish, the goals include to: “Erect livestock exclusion fencing, Develop off-stream watering facilities; Restore riparian plant communities, Prioritize removal of culverts and other barriers to fish movement” (p. 44), as well as to “Dredge lakes and streams, construct fish barriers, stabilize shorelines, construct settling ponds” (p. 60), and “Install oxygen diffusers in lakes and impoundments” (p. 64). For big game, the proposed projects include a commission that: “Communicates information on wildlife corridors and crucial habitat” and “Uses incentives to encourage landowners to appropriately manage habitats and wildlife corridors on private lands” (p. 83). Finally, for upland birds, the aims are to, among other things: “Develop, research and evaluate test sites to identify biofuel plant mixes that provide quality pheasant habitat” and, “Develop, research and evaluate wildlife-friendly carbon sequestration practices, including species mix, management and harvest tactics and measurement of carbon storage” (p. 93).

In line with the discursive strategies illustrated in this community, the projects listed in “Beyond Season's End” focus primarily on adaptation, and adaptation specifically for game species. The exceptions to this include incorporating mitigation projects into adaptation goals, such as the proposed projects which improve rangeland to sequester carbon and identify biofuel plant mixes that are also good habitat for pheasants. Furthermore, aligned with the discursive construction of the ideal natural world as part of the past, the most plausible climate change solutions are often presented as a return to this past, and modern, technocratic efforts, such as expanding renewable energy, are not commonly portrayed as desirable responses to the climate crisis. These proposals also tend to place less importance on policy solutions at the national level, especially those that target climate change mitigation. This effect is reinforced by the discursive positioning of climate change as mired within a polarized political context. Within this communicative context, very few NGOs urge their members to vote as part of the solution to the climate crisis. The report does, however, include some letters sent on behalf of the hunting community to the United States Senate as a whole, rather than individual senators. This approach further challenges the political polarization of climate change, but also has the effect of restricting the policy solutions presented as possible and desirable to those potentially palatable to both parties.

Together, the actions taken and proposed by these hunting NGOs demonstrate the potential of the mobilization of the hunting identity through shared discursive practices for catalyzing collective action for climate change adaptation. The adaptation projects proposed in “Beyond Season's End” would undoubtedly be quite beneficial to game species and their habitat. The proposed projects, however, also demonstrate that the mobilization of this shared identity can also constrain the climate crisis solutions that are most salient and plausible for members of this community, highlighting some possible actions, and backgrounding others.

This article has investigated the emerging movement for climate change activism among sportsmen and sportswomen, or hunters and fishers—a politically conservative group with historically deep roots to environmental conservation. This nascent social movement is important, since not only are sportsmen and women a historically-active group in conservation policy, but, in addition, their ties to both political conservatism and environmental conservation illustrate the importance of community-level analyses of conservation discourses and activism, which can be overlooked in broader approaches. The article drew on fieldwork conducted throughout the rural western U.S., including ethnographic interviews with sportsmen/sportswomen, participant observation in hunter education courses, and data from publicly-available media about climate change produced by hunting conservation groups. Using an ethnographic and discourse-analytic approach, I found that hunters and fishers use three main discursive practices to express both climate skepticism and climate change activism—a constructed closeness to wildlife and wild places, a privileging of experiential and embodied epistemologies, and a valorization of the past wilderness.

Recognizing the importance of the discursive practices illustrated in this article for performing climate skepticism and climate activism within the hunting and fishing community can broaden scholarly understandings of the interaction of environmental communications and identities within politically-conservative groups in the United States. This article has demonstrated the importance of analyzing these discursive practices, showing that not only are they integral to constructing and performing identities, setting the stage for the nascent climate change activism movement within the hunting and fishing community, they also shape perceptions of reasonable and plausible solutions to environmental crises.

By examining the discursive practices of an emerging climate change movement—a movement taking place within a community that already has collective power, and in many ways, is accustomed to exercising it—this paper also showed the potential for communication practices to be a site for challenging the polarization of climate change stances within the United States and mobilizing engagement with climate politics. It also highlighted the importance of these practices for harnessing the power of existing politically-active communities, such as sportsmen and women in the United States, and set the stage for further understanding how community-specific climate change movements, such as the one analyzed here, can arise through the mobilization of shared discursive practices and identities.

This analysis thus illuminated climate activism within an understudied group, highlighting the depth of the civic movement on climate change. It specifically showed the importance of shared discursive practices to both climate skepticism and climate activism among rural white hunters and fishers, as well as the way NGOs mobilize a collective identity for successful activism within the politically-conservative community. For scholars, this study also highlighted resources which enable climate change activism across the political spectrum, a task which becomes increasingly more important as the potentially catastrophic effects of climate change draw nearer.

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by University of California, Santa Barbara Human Subjects Committee (Institutional Review Board). The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

JL-N completed the design and implementation of the research, the analysis of the results, and the writing of the manuscript.

This research was supported by National Science Foundation Doctoral Dissertation Research Improvement Grant #1824063.

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

1. ^This portrayal could be attributable to a misunderstanding of geomagnetic reversal—the phenomenon in which the earth's magnetic field reverses (Banerjee, 2001), as it is not a climate denial discourse that I have previously encountered.

2. ^“Climate Change in the West: Beyond Season's End.” Available online at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gYx_ncjJV0U.

3. ^https://www.instagram.com/p/Bs08_QXDPIb/

4. ^“Conservation Hawks: End of the Season.” Available online at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BXrf7v6c6Dw.

5. ^Randy Newberg's Hunt Talk Radio EP 096: Hunting Advocacy & Politics with US Senator Jon Tester (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RuEkfSfQcPo).

6. ^Here the interviewee uses the term politicized synonymously with polarized to discuss the association of climate change with one political party (as it is often used in non-academic U.S. discourse), rather than in the sense more commonly used in environmental communication literature (Pepermans and Maeseele, 2016).

Alkon, A. H., Cortez, M., and Sze, J. (2013). What is in a name? Language, framing and environmental justice activism in California's Central Valley. Local Environ. 18, 1167–1183. doi: 10.1080/13549839.2013.788483

Altherr, T. L. (1978). The American hunter-naturalist and the development of the code of sportsmanship. J. Sport Hist. 5, 7–22.

Altherr, T. L., and Reiger, J. F. (1995). Academic historians and hunting: a call for more and better scholarship. Environ. Hist. Rev. 19, 39–56.

Bakhtin, M. M. (1981). “Forms of time and of the chronotope in the novel,” in The Dialogic Imagination, ed M. Holquist (Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 84–258.

Bamberg, S., Rees, J., and Seebauer, S. (2015). Collective climate action: determinants of participation intention in community-based pro-environmental initiatives. J. Environ. Psychol. 43, 155–165. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2015.06.006

Banerjee, S. K. (2001). When the compass stopped reversing its poles. Science 291, 1714–1715. doi: 10.1126/science.291.5509.1714

Bonilla, Y., and Rosa, J. (2015). Ferguson: digital protest, hashtag ethnography, and the racial politics of social media in the United States. Am. Ethnol. 42, 4–17. doi: 10.1111/amet.12112

Brick, C., and Lai, C. K. (2018). Explicit (but not implicit) environmentalist identity predicts pro-environmental behavior and policy preferences. J. Environ. Psychol. 58, 8–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2018.07.003

Bucholtz, M., and Hall, K. (2005). Identity and interaction: a sociocultural linguistic approach. Discourse Stud. 7, 585–614. doi: 10.1177/1461445605054407

Byram, M., Duffy, S., and Murphy-Lejeune, E. (1996). The ethnographic interview as a personal journey. Lang. Cult. Curric. 9, 3–18. doi: 10.1080/07908319609525215

Carfora, V., Caso, D., Sparks, P., and Conner, M. (2017). Moderating effects of pro-environmental self-identity on pro-environmental intentions and behaviour: a multi-behaviour study. J. Environ. Psychol. 53, 92–99. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2017.07.001

Carvalho, A., van Wessel, M., and Maeseele, P. (2017). Communication practices and political engagement with climate change: a research agenda. Environ. Commun. 11, 122–135. doi: 10.1080/17524032.2016.1241815

Colloff, M. J., Lavorel, S., Kerkhoff, L. E., Wyborn, C. A., Fazey, I., Gorddard, R., et al. (2017). Transforming conservation science and practice for a postnormal world. Conserv. Biol. 31, 1008–1017. doi: 10.1111/cobi.12912

Cox, R., and Schwarze, S. (2015). “Strategies of environmental pressure groups and NGOs,” in The Routledge Handbook of Environment and Communication, ed A. Hansen and R. Cox (New York, NY: Routledge, 73–85.

Davidson, D. J., and Haan, M. (2012). Gender, political ideology, and climate change beliefs in an extractive industry community. Popul. Environ. 34, 217–234. doi: 10.1007/s11111-011-0156-y

Dietz, T., Kalof, L., and Stern, P. C. (2002). Gender, values, and environmentalism. Soc. Sci. Q. 83, 353–364. doi: 10.1111/1540-6237.00088

Doyle, J., Farrell, N., and Goodman, M. K. (2017). “Celebrities and climate change,” in Oxford Encyclopedia of Climate Science, ed M. Nisbet (Oxford: Oxford Research Encyclopedias).

Du Bois, J. W. (2007). “The stance triangle,” in Stancetaking in Discourse: Subjectivity, Evaluation, Interaction, ed R. Englebretson (Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 139–182.

Dunlap, R. E., McCright, A. M., and Yarosh, J. H. (2016). The political divide on climate change: partisan polarization widens in the US. Environ. Sci. Policy Sustain. Dev. 58, 4–23. doi: 10.1080/00139157.2016.1208995

Geist, V., Mahoney, S. P., and Organ, J. F. (2001). Why hunting has defined the North American model of wildlife conservation. Trans. North Am. Wildlife Nat. Res. Conf. 66, 175–185.

Gentile, N. (2017, February 2). Republican bill to privatize public lands is yanked after outcry. Think Progress. Retrieved from: https://thinkprogress.org/republican-bill-to-privatize-public-lands-is-yanked-after-outcry-d77bc0041c85/.

Goebbert, K., Jenkins-Smith, H. C., Klockow, K., Nowlin, M. C., and Silva, C. L. (2012). Weather, climate, and worldviews: the sources and consequences of public perceptions of changes in local weather patterns. Weather Clim. Soc. 4, 132–144. doi: 10.1175/WCAS-D-11-00044.1

Han, H., and Barnett-Loro, C. (2018). To support a stronger climate movement, focus research on building collective power. Front. Commun. 3:55. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2018.00055

Herman, D. J. (2014). Hunting and American identity: the Rise, fall, rise and fall of an American pastime. Int. J. Hist. Sport 31, 55–71. doi: 10.1080/09523367.2013.865017

Howe, P. D., Mildenberger, M., Marlon, J. R., and Leiserowitz, A. (2015). Geographic variation in opinions on climate change at state and local scales in the USA. Nat. Clim. Chang. 6, 596–603. doi: 10.1038/nclimate2583

Johnstone, B. (1999). Uses of Southern-sounding speech by contemporary Texas women. J. Sociolinguist. 3, 505–522. doi: 10.1111/1467-9481.00093

Jones, K. R. (2015). Epiphany in the Wilderness: Hunting, Nature, and Performance in the Nineteenth-Century American West. Boulder, CO: University Press of Colorado.

Kahan, D. M., Peters, E., Wittlin, M., Slovic, P., Ouellette, L. L., Braman, D., et al. (2012). The polarizing impact of science literacy and numeracy on perceived climate change risks. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2, 732–735. doi: 10.1038/nclimate1547

Killingsworth, M. J., and Palmer, J. S. (2012). Ecospeak: Rhetoric and Environmental Politics in America. Carbondale; Edwardsville, IL: SIU Press.

Larson, L. R., Stedman, R. C., Decker, D. J., Siemer, W. F., and Baumer, M. S. (2014). Exploring the social habitat for hunting: toward a comprehensive framework for understanding hunter recruitment and retention. Hum. Dimens. Wildl. 19, 105–122. doi: 10.1080/10871209.2014.850126

Levy, B. L. M., and Zint, M. T. (2013). Toward fostering environmental political participation: framing an agenda for environmental education research. Environ. Educ. Res. 19, 553–576. doi: 10.1080/13504622.2012.717218

Love-Nichols, J. (2020). “How much longer can you last in Brooklyn? Constructing and challenging the boundaries of ecocultural identity among sportsmen,” in The Routledge Handbook of Ecocultural Identity, eds T. Milstein and J. Castro-Sotomayor (New York, NY: Routledge).

Lucas, C., and Warman, R. (2018). Disrupting polarized discourses: can we get out of the ruts of environmental conflicts? Environ. Plann. C Polit. Space 36, 987–1005. doi: 10.1177/2399654418772843

McCright, A. M. (2010). The effects of gender on climate change knowledge and concern in the American public. Popul. Environ. 32, 66–87. doi: 10.1007/s11111-010-0113-1

McCright, A. M., and Dunlap, R. E. (2011). Cool dudes: the denial of climate change among conservative white males in the United States. Glob. Environ. Change 21, 1163–1172. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2011.06.003

National Wildlife Foundation (2012). National Survey of Hunters and Anglers. Retrieved from: https://www.nwf.org/News-and-Magazines/Media-~Center/Reports/Archive/2012/09-25-12-National-Sportsmen-Poll.aspx

O'Brien, B. (2018). Midterm elections 2018: a tough decision for hunters and anglers, podcast transcription. The MeatEater. Retrieved from: https://www.themeateater.com/listen/the-hunting-collective-2/mid-term-elections-2018-tracking-the-ideal-candidate-for-hunters-and-anglers

O'Brien, J. (2015, February 25). Hunters, anglers & climate change. Yale Climate Connections. Retrieved from: https://www.yaleclimateconnections.org/2015/02/hunters-anglers-and-climate-change/.

Organ, J. F., Geist, V., Mahoney, S. P., Williams, S., Krausman, P. R., Batcheller, G. R., et al. (2012). The North American Model of Wildlife Conservation. The Wildlife Society Technical Review 12-04. Bethesda, MD: The Wildlife Society.

Pepermans, Y., and Maeseele, P. (2016). The politicization of climate change: problem or solution? Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Change 7, 478–485. doi: 10.1002/wcc.405

Randall, C. (2019, January 11). Hunters and anglers flex their political muscles. High Country News. Retrieved from: https://www.hcn.org/issues/51.1/public-lands-~sportsmen-flex-their-muscles-in-state-politics.

Reiger, J. F. (1975). American Sportsmen and the Origins of Conservation. New York, NY: Winchester Press.

Rich, J. L. (2016). Drilling is just the beginning: romanticizing rust belt identities in the campaign for shale gas. Environ. Commun. 10, 292–304. doi: 10.1080/17524032.2016.1149085