- 1Department of English Language and Linguistics, University of Birmingham, Birmingham, United Kingdom

- 2School of Humanities, Coventry University, Coventry, United Kingdom

With the recent launch of the National Bereavement Care Pathways in the UK (http://www.nbcpathway.org.uk/pathways/) that are designed to help professionals to support families in their bereavement after any pregnancy loss, there has been an increased interest in aligning the care provided to the needs that are expressed by the bereaved parents. In order to do this we need in-depth knowledge of these experiences. In this paper, we report findings from a study, conducted in England, that explored the ways in which those who have experienced pregnancy loss talk about their experiences at different stages in the diagnosis and experience of pregnancy loss. We focus both on what they say and the language they use to describe their experiences, in order to gain insights that may make it easier for those who support them through the process to do so in an effective manner. We focus in particular on the metaphors they use to describe their experiences. Metaphors are often used by people when describing intensely painful, personal experiences that would otherwise be inexpressible. Exploring the metaphors used by the bereaved allows us to gain deeper insights into what they are going through and understanding these metaphors may allow us to support them more effectively. We also examined the accounts of midwives and other NHS maternity bereavement care practitioners in order to gain insights into their perspectives on the issues identified through our analysis of the metaphors used by the bereaved, and to identify areas of good practice which correspond to the experiences of the bereaved. We were interested in their own practice but also in the environment in which they work and the constraints that this sometimes brings.

Introduction and Background to the Study

With the recent launch of the National Bereavement Care Pathways in the UK (http://www.nbcpathway.org.uk/pathways/) that are designed to help professionals to support families in their bereavement after any pregnancy loss, there has been an increased interest in aligning the care provided to the needs that are expressed by the bereaved parents. In order to do this we need in-depth knowledge of these experiences. Research has shown that pregnancy loss is a complex experience, fraught with tension and ambiguity on both the psychological and the physiological levels. Psychologically, the grief following pregnancy loss is exacerbated by the lack of cultural scripts to frame the grieving process. Tensions may arise from the contrast between an experience that is on the one hand “natural” in the biological sense, but on the other hand considered “unnatural” to the point of being taboo in the social sense. While the bereaved have often begun to form their identities as parents, pregnancy loss deprives them of a means to enact their parental identity (Littlemore and Turner, 2019). Physiological conflict arises through the end of life occurring before birth, and through changes to the mother's body continuing despite there being no baby to sustain (Kuberska and Turner, 2019).

Studies have shown that there is a need for compassionate care following pregnancy loss and that a lack of such care has severe impact on the well-being of the parents (see Gold, 2007 for the US context and Cullen et al., 2017 for the UK context). Questionnaire studies have been used to explore the impact of factors such as the gender of the parent and the presence of siblings on the length of the grieving process (Volgsten et al., 2018). It has been acknowledged that pregnancy loss takes a toll on the midwives who support patients as well, with many midwives expressing a lack of confidence in knowing what to do (Agwu Kalu et al., 2018). This has led to an increase in training initiatives for midwives that are designed to promote their confidence in providing bereavement care to grieving parents. These training initiatives also aim to increase their self-awareness around their clinical practice in this area (Doherty et al., 2018). There is international variation in the ways in which support and treatment are offered following pregnancy loss (see Ravaldi et al., 2018 for the Italian context and Fleming et al., 2016 for the Swiss context). It should be noted that in this paper, we investigate pregnancy loss in the English context exclusively.

A particularly powerful way of exploring people's individual experiences is to examine the ways in which they use metaphor to describe them. Metaphor is a device by which one concept, experience or object is defined or described in terms of another (Cameron, 2003). For example, people sometimes talk about women's careers hitting a “glass ceiling.” While there is obviously no glass ceiling in any literal sense, the expression brings to mind ideas of invisible barriers to promotion, the idea that one can see through them but not get through them, and perhaps the idea that they might ultimately be shattered. While traditionally considered solely a literary or creative device, contemporary views of metaphor consider it to be a fundamental element of human language and thought, and an important device by which we understand, conceptualize and express our experiences (Lakoff and Johnson, 1980). Metaphor is a particularly useful mechanism for exploring experiences that are not widely shared as it frequently involves the use of something that is familiar, tangible or common to describe something that is unfamiliar. For this reason, it has been shown to be particularly prevalent when people are talking about complex, difficult or emotionally-charged experiences, such as depression (Charteris-Black, 2012), cancer (Gibbs and Franks, 2002), addiction (Shinebourne and Smith, 2010), mental health post-trauma (Wilson and Lindy, 2013), and end-of-life care (Semino et al., 2017, 2018), as it provides a tool to understand and describe these abstract, personal experiences by relating them to more concrete, universal ones. Unlike a content analysis, a metaphor analysis allows for an in-depth exploration of the ways in which people conceptualize emotional experiences and the underlying attitudes and assumptions that inform the way they describe them. Metaphors highlight some aspects of an experience whilst downplaying others (Lakoff and Johnson, 1980), and it is often necessary to employ more than one metaphor to capture the richness and conflicting facets of an experience, as evidenced in the papers in Gibbs (2016). Because metaphor analysis is effective in showing the complexities, tensions and ambiguities of emotionally-charged experiences, it is a useful tool for exploring the experience of pregnancy loss.

In this paper, we report findings from a study, conducted in England, that explored the metaphors used by people when talking about their past experiences of pregnancy loss. We define “pregnancy loss” as a loss occurring at any gestational stage, encompassing miscarriage, stillbirth, and termination for reasons of fetal anomaly. Our decision to include all three types of pregnancy loss was made at the project planning stage in response to feedback obtained from our project partners (Sands1, the Miscarriage Association and Antenatal Results and Choices) that different perceptions of pregnancy loss do not map neatly onto clinical gestational stages or the type of loss. However, in our analysis we do give consideration to the type of loss experienced. Our focus was on the metaphors that our participants used when they were talking about four key moments during the period of pregnancy loss, some of which involved important decisions. These are: (1) the point at which people received the diagnosis; (2) the time during which they were making decisions about the pregnancy, for example induction, medical or surgical management of miscarriage, or choosing to terminate in the case of fetal abnormality; (3) the time during which they were deciding how to “look after” the baby after delivery; and (4) the time during which they were making decisions about funerals, rites and rituals where appropriate. We hypothesized that metaphor would be prevalent in individuals' recounting of their experiences of pregnancy loss, and that these metaphors would shed light on their (sometimes conflicting) emotional experiences and the ways in which they construed them, facilitating a deeper understanding of what they were going through and how this impacted upon their decision making. Our aim was to provide insights into the experiences of people who go through pregnancy loss to help midwives and others who support them through this difficult time.

We also analyzed the ways in which midwives and other NHS maternity bereavement care providers (hereafter referred to as midwives2) talked about these issues, in order to gain insights into their perspectives on the issue and to identify areas of good practice which correspond to the experiences of the bereaved. We were interested in their own practice but also in the environment in which they work and the constraints that this sometimes brings.

Methodology

This research forms part of the “Death before Birth” project3, a 2-year ESRC-funded study4 running from 2016-18 and granted ethical approval5 by the University of Birmingham. The project was devised in association with the Stillbirth and Neonatal Death Charity (Sands), the Miscarriage Association (MA), Antenatal Results and Choices (ARC), and the Human Tissue Authority (HTA). Its overall aims were to examine how people in England who have experienced miscarriage, termination for fetal anomaly, and stillbirth talk about the ways in which they reached decisions concerning what happens to their baby after death, how their perceptions of the law impacted on their decision-making, and how they communicated their experiences and choices to those there to support them. We also examined the impact of Human Tissue Authority guidance on what happens to babies after they have died, investigating how it is interpreted in practice by professionals and the extent to which it takes account of the views, experiences and needs of the bereaved. This interdisciplinary project combined aspects of socio-legal studies, cultural studies, and linguistics.

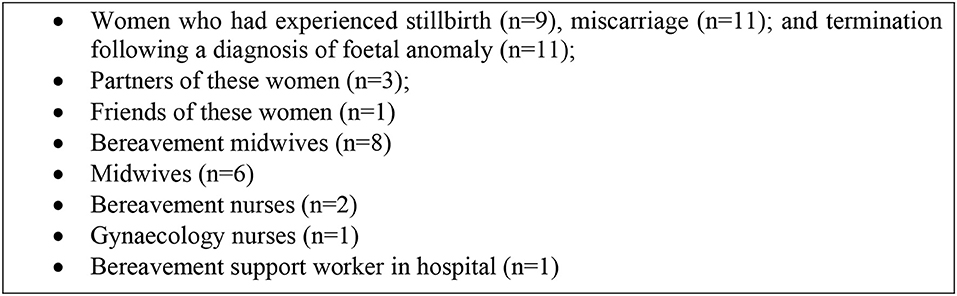

In order to obtain the data required for the current study, three members of the research team6 interviewed 35 people, the majority of whom had experienced miscarriage, termination for fetal abnormality (hereafter referred to as “termination”), or stillbirth in England a minimum of 6 months before the interview. Participants who had experienced pregnancy loss were recruited through Sands, the MA and ARC. Advertisements were circulated via their internal distribution networks, newsletters and public-facing websites. The advertisements invited potential participants to share their stories of pregnancy loss, including their emotional responses, the care they received, and the decisions they made regarding marking or commemorating the loss. They were informed that the aims of the project were to contribute to better support for people who have experienced pregnancy loss, and to improve public understanding about the choices and decisions made by bereaved families.

It should be noted that some of our participants had experienced more than one type of loss, and discussed all their experiences of loss in the interviews. Because of this, the codes given for the excerpts provided below may not necessarily reflect the type of loss under discussion. Written, informed consent was obtained from all participants. All participants were over 18 and living in England. Of the 35 participants, 31 were women who had experienced a loss, three were male partners of the female participants, and one was a friend of the bereaved (see Figure 1). We recognize that the dataset is somewhat unbalanced in terms of gender and experience, but this is due to the partially self-selecting nature of the recruitment process. Unfortunately, we do not know how many people our messages reached as we did not contact them directly, which is a limitation of our study. In addition, while were we able to recruit women who had experienced pregnancy loss, there was less response from their partners. We also recognize that because we recruited our participants through support organizations, our sample may be skewed toward those who felt the need for the support that these charities offer (although this is mitigated by the fact that some participants signed up to the study through word-of-mouth and had not approached the charities directly). It is important to note, therefore, that the experiences of our participants may not be shared by everyone who goes through pregnancy loss, as people's grief responses differ in nature and in strength. However, our project is designed to improve care for those who are finding it difficult to come to terms with their pregnancy loss, so we wanted to hear from people who needed this care most.

In order to explore the extent to which the care given by midwives corresponded to what the participants said would have been beneficial, a member of the research team7 conducted 12 interviews with 18 bereavement healthcare providers (see Figure 1 and Appendix 1 in Supplementary Material). These interviews explored their perceptions of bereaved parents' needs and how they attempted to meet them, their views on the support they offered and the procedures under which they were operating. They were recruited directly from hospitals across four NHS regions (London/the South/ the Midlands/ the North) through the Local Supervising Authority Midwifery Officers Forum UK (LSAMO). Our point of contact also facilitated access to relevant professional networks and associations, including online forums.

The interviews were semi-structured and 60–90 min in length. They were conducted in quiet surroundings away from the participants' places of work. While most of the interviews were 1-to-1, some of the bereavement care providers chose to be interviewed in pairs or small groups (see Appendix 1 in Supplementary Material). During the interviews with the bereaved, we explored their experiences of pregnancy loss, focusing on what they did with their baby in terms of funerary arrangements, and how they reached their decisions. During the interviews with the midwives, we asked them about the care they provided for the bereaved following pregnancy loss and the procedures used in their Trusts. Details of the participants in our study are shown in Figure 1.

The interviews were transcribed8 and the transcripts were uploaded into NVivo for coding. NVivo is a qualitative research package which is used to assist in data organization, annotation and categorization using a set of user-defined “nodes.”

We (Littlemore and Turner) first coded the transcripts of the interviews with the bereaved for metaphor. In order to decide whether an utterance was metaphorical or not, we employed an adapted version of the PRAGGLEJAZ Group (2007) Metaphor Identification Procedure, which involves recognition of the fact that something is being described in terms of a different entity and in some way compared to that entity. Following Cameron (2003), we adjusted this procedure slightly as we were more interested in identifying metaphors at the level of the phrase than at the level of the word. We then classified the metaphors into broad categories that reflected the semantic fields to which the metaphors belonged. For example, consider the following sentence, which a participant who had undergone a termination following a diagnosis of fetal anomaly used to describe her state of mind and her “recovery” process, following the loss:

(1) I tend to go off on tangents and lose where I am myself [WP4-T32-FA-P1]9

We identified two metaphors within this sentence: “go off on tangents” and “lose where I am myself.” We coded both of these as “journey” metaphors but we also coded the second metaphor as a “location” metaphor and as a “divided-self” metaphor.

Each metaphorical chunk of language was then assigned to at least one topic. Topics were identified via an iterative process. We included both practical topics (such as, “receiving the diagnosis,” “labor,” and “care provision”) and more emotional, less tangible topics (such as, “hopes and expectations,” “validation of the loss,” “isolation”). We used the context to establish what the topic of the metaphor was.

The coding scheme for both metaphors and topics was developed by three coders10 through detailed joint analyses of the first five transcripts. Subsequent transcripts were then coded individually in the first instance. Each coding decision was then verified by a second coder and all marginal cases were discussed in depth until agreement was reached11. An example of one such case is the following:

(2) [NAME] was saying the sort of waffly things that one would expect people to say and it wasn't hitting the mark [WP4-T35-S-F4]

Here, the phrase “hitting the mark” was coded by the first coder as “sport and games” and by the second coder as “violence and impact” because hitting the mark could refer to target practice or to impact. Following discussion, the decision was made to code this excerpt as both sport and games and violence and impact.

We identified 67 metaphor categories (such as, “fighting,” “nature,” “balance,” and “movement”) which were used to talk about 71 topics. A full list of metaphor categories with examples can be found in Appendix 2 (Supplementary Material) and a full list of topics can be found in Appendix 3 (Supplementary Material). We also coded salient cases of metonymy. Metonymy, like metaphor, is a figurative device, but whereas metaphor involves describing something in terms of something different, metonymy involves drawing on a particular aspect of the same concept in order to define it. One might refer to the UK government as “No. 10,” for example, using the street address to stand for the Prime Minister's residence, which in turn stands for the whole government.

Excerpts from our data include:

(3) Well, when [BABY NAME] had gone horribly pear shaped [WP4-T1-FA-1]

(4) Yeah, I've got that, I wanted to get that [a tattoo of the baby's name] as soon as possible. I was like, putting her on my body again [WP4-T10-FA-2]

In excerpt 3, the baby's name is used to refer metonymically to the whole pregnancy and the fact that it had ended in a loss. In excerpt 4, the tattoo is referring metonymically to the baby. The fact that the name of baby is tattooed on her body evokes a metonymic enactment of being physically close to her baby again. This is discussed in more depth in Littlemore and Turner (2019).

Because metonymy is a more pervasive phenomenon than metaphor and because it very often shades into literal language (see Littlemore, 2015) it is not useful to identify every potential instance of metonymy in a dataset. However, some uses of metonymy are particularly marked and their use stands out as being peculiar to a given group of people. Cases such as these were identified in our data.

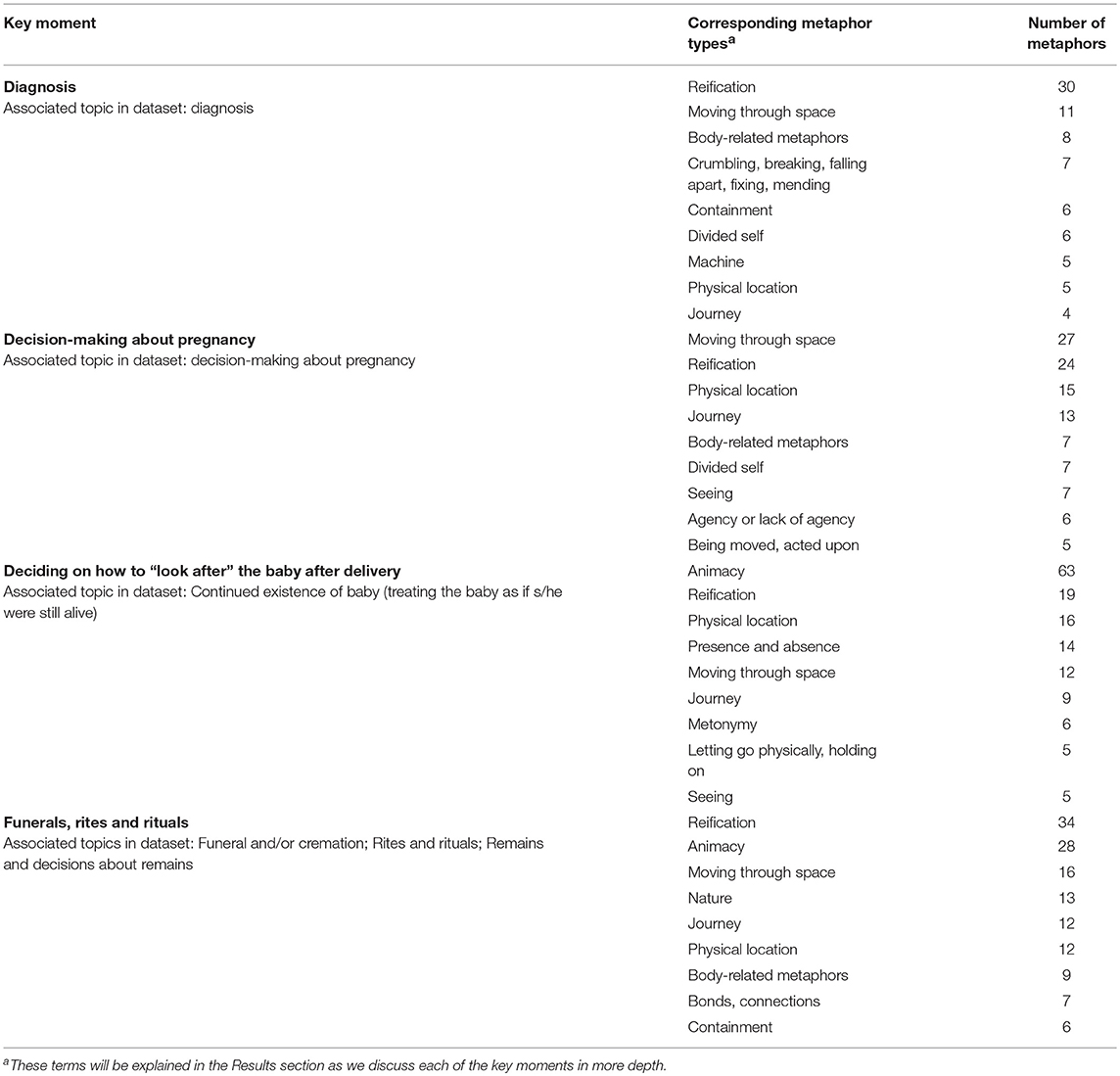

After having coded our data for these metaphor categories we were able to establish which metaphor categories co-occurred with which topics, thus providing insights into the ways in which those aspects of the pregnancy loss were commonly conceptualized. We focused on topics which corresponded to four key moments in the process of pregnancy loss and identified the metaphors that were most commonly used to talk about them. As stated above, the moments in question were: the point at which the diagnosis was received; the time during which they were making decisions about the pregnancy; the time during which they were making decisions on how to “look after” the baby after delivery; and the time during which they were deciding on funerals, rites and rituals. Our focus throughout is on the ways in which people use metaphor to describe these experiences, what their metaphors can tell us about their conceptualizations of their experiences, and the implications of this on care-giving.

We used Nvivo to identify the metaphorical categories that occurred most frequently for each of the four key moments under discussion. The key moments and their corresponding topics are summarized in Table 1, along with the numbers of metaphors of each type that were used at each stage. For the first two key moments, “Diagnosis” and “Decision-making about pregnancy,” there was a clear one-to-one match in the topics we had identified in our dataset. The other two key moments (“Deciding how to ‘look after' the baby after delivery” and “Funerals, rites and rituals”) reflect a tension which constitutes a recurring theme in our data. In brief, we noted over the course of our coding that parents were frequently talking about their baby as if s/he were, on some level, still alive (Littlemore and Turner, 2019). On the one hand, they want to parent their baby, but on the other they have to organize his/her funeral. This tension is expressed in the following excerpt from a parent:

(5) At the time it's just like, right, well, what coffin do you want for your baby? Well, I don't want a coffin. I don't want a coffin. I want him to be at home in a cot. So therefore I don't want a coffin. And that's the thought process you go through. [WP4-T28-S-7]

This tension was reflected in the topics we chose to explore these moments. For “Deciding how to look after the baby,” we chose the topic “Continued existence of baby,” in which the parents talked about treating the baby as if s/he were still alive. For the “Funerals, rites and rituals” key moment, we combined three topics emerging from our coding: “Funeral and/or cremation,” “Rites and rituals,” and “Remains and decisions about remains.”

After having identified the ways in which the key moments in the experience of pregnancy loss were conceptualized through metaphor, we conducted a content analysis of the transcripts of the interviews with the midwives to identify ways in which their conceptions of loss and the care that they required corresponded to those of the bereaved. We also examined their accounts of the ways in which their working practices were shaped by their professional contexts. We chose to conduct a content analysis of the interviews with the midwives rather than a metaphor analysis because these interviews had a much more practical focus and did not explore their emotional experiences. This is because we were interested in finding out how they looked after the bereaved. As we saw above, metaphor analysis is particularly useful for investigating complex emotional experiences.

Key Moments in Pregnancy Loss: How They are Experienced and Described Through Metaphor and How They are Viewed by the Midwives

In this section, we look at the four key moments in the experience of pregnancy loss and analyze the metaphors that were used by our participants to describe these experiences retrospectively during the interviews. For each of these areas, we talk about how they reported what they had felt at the time and subsequently. We focus on the experience itself, and the care, advice and information that they received. We discuss the implications that these findings have for the role of midwives in supporting people through pregnancy loss. Our focus is on the most frequently used metaphors corresponding to each key moment as these provide access to those conceptualizations that were most widely shared across our participant pool. We then explore the accounts offered by the midwives themselves in relation to each of these key moments, and identify areas of good practice as well as particular challenges they face in their roles.

The Diagnosis

Views of the Bereaved

Clearly the moment at which one learns of the diagnosis that their baby had died or that there is a serious fetal anomaly is a pivotal moment in the experience of pregnancy loss.

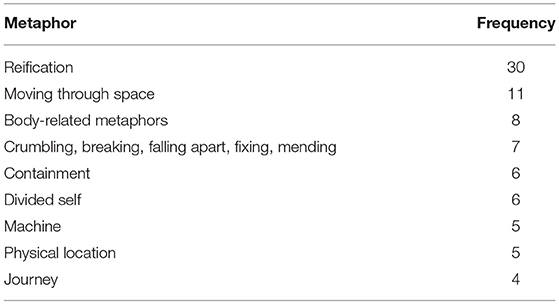

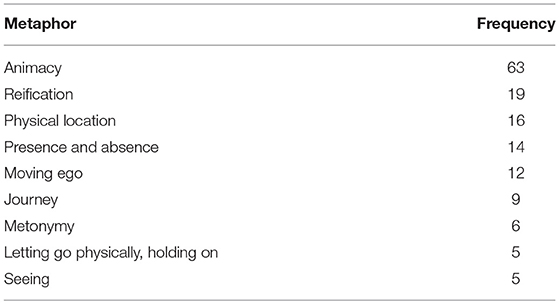

The most frequent metaphors observed when participants were talking about the moment of diagnosis are shown in Table 2. In this section, we demonstrate how these metaphors work together to paint a picture of the way in which our participants experienced this moment.

Table 2. Most frequent metaphors observed when participants were talking about the moment of diagnosis.

The most frequent metaphor category when participants are describing the diagnosis is reification. This refers to cases where people express abstract concepts in concrete terms. Reification underpins many of the other metaphor uses in this section (and indeed in the whole dataset), which explains its frequency. One theme that arises from the metaphors in this section is that of location and physical movement through space. Another theme is that of fragmentation and the subsequent need to “repair,” which is especially interesting when seen in conjunction with the “divided self” metaphor and “containment” metaphors. We now discuss these ideas in more depth.

The use of physical movement metaphors to talk about human experiences can be considered very conventional; consider phrases like “I'm going through a rough time,” or “We're coming up to the weekend.” However, while conventional, an analysis of the types of physical movement metaphors that our participants used can shed light on the ways in which they conceptualized what was happening to them. The physical movement metaphors that were employed by the participants in our study exhibited an unusually large amount of agency. Participants were significantly more likely to use movement metaphors to convey a sense of physical movement through the experience rather than passive reactions to an experience that was happening to them. Excerpts 6 and 7 below are taken from our interviews at moments where the participants were asked to talk about how they reacted to a diagnosis of fetal anomaly:

(6) Almost like I had this task I had to do which was to get to the end of this pregnancy … I was very focused on just getting to the end of it [WP4-T17-FA-6]

(7) I wasn't just gearing up toward losing the baby I was also gearing up toward having to make a decision to terminate the pregnancy [WP4-T20-M-10]12

In both these excerpts, the women seem to consider themselves to have a sense of agency in the situation, and in both there is a clear desire to take control, either by deliberately focusing their efforts on the “task” of getting to the end of the pregnancy, or by deliberately preparing to go through the loss of the baby. Their use of the journey metaphor could reflect their attempts to reconcile the conflicting tensions inherent in the experience of needing to terminate a wanted pregnancy. By conceptualizing this experience as a “journey,” they are focusing on the possibility of moving through the tension, and that highlighting the fact that the journey has a destination they will reach.

Other participants used metaphors that suggested the information they received felt somewhat fragmented and disjointed and that it was up to them to make sense of it; they needed to piece things together themselves in order to build a bigger picture:

(8) I sort of managed to stitch bits of information to try and picture it in my mind what was [going to] happen, what was expected so I was fully informed. [WP4-T10-FA-2]

Here too the participant demonstrates a degree of agency, but there is a sense in all these cases that this agency is reluctantly adopted as the participants would rather not be in situations where this is necessary. There is a tension here between having agency, which is usually considered a positive thing, and not wanting it. Participants seem to deal with this by focusing on the end goal and/or the bigger picture through the use of “journey” and “patchwork” metaphors.

When describing their reactions to the news, some of the participants who we interviewed made use of metaphors that reflected a sense of disorientation which was then associated with a lack of agency. Here, we take excerpts from interviews with two participants who had both suffered miscarriages:

(9) And then as soon as it [became] a real thing … I had to say the words “I've had a miscarriage” … that's when … I just felt like everything had just fallen out of the world and like I just failed and that … there was no control there was … nothing and I just felt so empty and … confused. [WP4-T9-M-8]

For this speaker, the world has emptied out, and she feels as if she is also empty: both her sense of location in a world and her sense of being have been destroyed by the physical experience of miscarriage. This perceived lack of agency provides an interesting counterpoint to the sense of agency and control that we saw in the excerpts above, possibly due to the nature of the loss and the idea of perceived “choice” inherent in a diagnosis of fetal anomaly. This becomes particularly interesting in excerpt 10 below, where the woman perceives her body and mind as having taken on “agencies” of their own, operating independently of the conscious self:

(10) I think it's quite hard because you have that massive shock … and your brain shuts down … and I couldn't process it. I knew they needed to tell me that then because of the nature of it. I knew that you couldn't wait … I don't even know even if she explained it really well … my brain was obviously still in shock mode by then. The sonographer, she basically gave us a file and told us where to go but I think would've been nice if she'd said “right look you will now be going to the early pregnancy unit, they are going to have other people there with scans, which I'm really sorry about … but it's just we don't have resources. Once you go into to there the lady or man or whoever will explain to you what has happened,” but it wasn't. She came in the room and she gave me my file and she said the EPU is … and I said where is it? She said just follow the signs … and I actually put in a complaint about her. And she was the senior sonographer which surprised me. [WP4-T4-M-3]

These metaphors were complemented by containment metaphors, through which participants talked about how they were unable to “take in” new information. These feelings of being overwhelmed, of disorientation and distance from one's own thought processes mean that clear support and direction are vital. This woman needed to be given much more guidance and shown what direction to take. Although this particular woman is talking about guidance in very practical terms (i.e., she literally needed to be shown where the early pregnancy unit was, and told what would happen when she got there), the need for clear guidance is also likely to extend more generally to emotional and psychological support.

This sentiment was expressed by a number of participants in our study who reported a sensation of compartmentalization when referring to the experience of pregnancy loss and all the decisions that they had to make as a result of it. A woman who had experienced a termination commented:

(11) Because it depends which bits of the process. Because there's so … many different parts to it, there's the procedures, there's the “what's the best option?” “What's the easiest option?” when you get that diagnosis that things are going wrong. There's what to expect afterwards, there's … I wouldn't even know where to begin to explain because in this whole situation … we found there were so many different sort of compartments almost to it. [WP4-T1-FA-1]

Reactions such as this suggest that some people may find it useful to break down the overwhelming experience of pregnancy loss into manageable parts. As a result, they may like to have the different issues explained to them one by one and then discussed separately along with their various implications and ramifications. It is important for those responsible for delivering information to give careful consideration to the way they pace the information.

Implications for Care

These insights into the way our participants felt immediately following the diagnosis have interesting implications for caregivers, and there may be differences according to the type of loss. Being given a diagnosis of fetal anomaly may cause women to feel they need to take control of the situation, albeit reluctantly. However, this need to take control may be hampered by what they consider to be the fragmented nature of the process, and the information they receive about it. Some patients may have a psychological reaction to the bereavement which results in a feeling that their own thought processes are alien to them. An effective way for caregivers to respond at this point in the process would be to provide as much information as they can and to ensure that there are no gaps in the information that is provided, so individuals do not feel the need to “stitch bits of information” together. The information may need to be provided in manageable chunks so that it is not overwhelming for a recently bereaved person. However, these chunks must be internally coherent and the links between them made clear. Women should be given opportunities to make informed choices regarding how to proceed, based on complete information.

Perspectives of the Midwives

In this section we turn to the midwives' perspectives on the ways in which people feel when they receive the diagnosis, and the ways in which they can help them cope with it in ways that reflect the fact they often feel out of control and disorientated.

Our data strongly suggest that midwives are acutely aware of the poignancy of this moment:

(12) Interviewee 1: all the research that I've read and all the studies that I've read, there's a common theme … and one of the common themes is they will never forget that moment. That moment, of how that news was shared is a memory that stays with them forever … you talk to women—talk to any woman that's lost a baby, they will remember that moment of how that was explained to them— [WP2-T7-BCP-04]

They are also aware of the need to present information in as clear a way as possible, avoiding euphemism, as we can see in the excerpt 13 below:

(13) and of course if it's a … missed miscarriage she's generally not passed the fetal remains really I think their biggest concern most often [because] you know the woman will be asked straightforwardly you know has she passed any solid material [WP2-T27-BCP-12]

They understand that people who are emotionally distressed do not always absorb all the information at once:

(14) Interviewee 1: They need … you know, adequate information. We understand that, you know, when you lose a baby initially you are in a state of shock, and you know … grief and sadness and … denial so … you cannot … be [a] hundred percent sure that all the information that you give at one stage that they absorb all the information so we provide … written information [WP2-T24-BCP-10]

We saw less acknowledgment of the fact that in some cases the bereaved felt the need to take control from the outset and get to the end of the process. This is a difficult issue as it needs to be balanced against potential information overload. One way of dealing with this is touched on in the excerpt 15 below:

(15) it's a lot of information and there is a lot of information that when you've lost a baby … that you have to take in, and there are lots of options and lots of things that people will come in and talk to you about and it is incredibly overwhelming … but we have our own parent information form, that works in conjunction with the consent form that we use, so they marry up together, so section one of the consent form is discussed in section one of the parents information so it takes the parents through the form that they're going to be signing … I think that the majority of time we do achieve this that the person who will be taking the consent will actually impart all of that information to them in an appropriate level and sensitive manner, that actually, the written information is just something for them to take away to back up a conversation [WP2-T16-BCP-06]

We can interpret this in the context of what the participants were saying about needing to “stitch the information together.” What this midwife is saying is important: that differential use can and should be made of the different forms of communication, with spoken and written information being used to complement one another.

Making Decisions About the Pregnancy and Termination Procedures

Views of the Bereaved

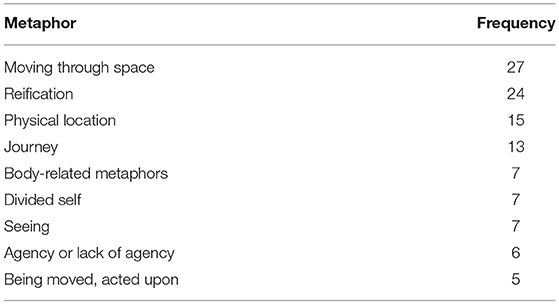

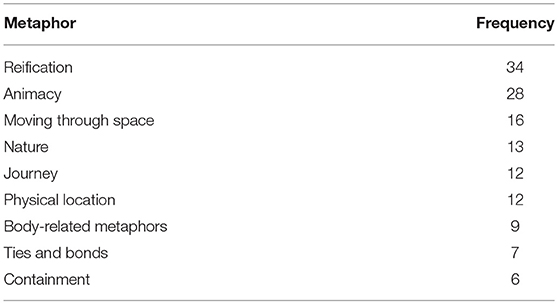

Following the diagnosis of a loss, people are faced with a number of decisions regarding how to proceed. The exact nature of these decisions will depend on the nature of the loss; whether to continue with a non-viable pregnancy in the case of fetal anomaly, choosing between medically or surgically managed miscarriage, and choices around labor and birth. The most frequent metaphors observed when participants were talking about making decisions about the pregnancy are shown in Table 3.

Table 3. Most frequent metaphors observed when participants were talking about making decisions about the pregnancy.

Similarly to the metaphors used when talking about the moment of diagnosis, the picture emerging here is one of dynamism and fragmentation. However, at this point a new metaphor is introduced: that of agency in varying degrees. We now explore the implications of these different metaphors in more detail.

Our participants made substantial use of metaphors referring to the decision-making process as a journey that they were about to embark upon, and sometimes alluded to its complexity. Excerpt 16 below, from a participant who received a diagnosis of fetal anomaly, is reminiscent of the “journey” metaphors employed at the moment of diagnosis discussed above:

(16) We had several conversations back at home … veering from really what to do … whether to terminate. Whether to carry on. [WP4-T32-FA-P1]

In a similar vein, this participant is relieved to be “in step” with and therefore following the same path as her partner through their experience of stillbirth:

(17) So at the end of that week … I remember [NAME] saying, oh, I don't know, and the blessing was we were both in step and that was a real gift. [WP4-T30-S-9]

An acknowledgment of the complex nature of this journey, the paths that need to be chosen, and the difficulties faced at every turn therefore appears to be an important part of the help provided for people who are making difficult decisions that follow pregnancy loss.

Many of the metaphors used did not explicitly involve journeys but they did involve various kinds of movement. Excerpt 18 below shows how the post-loss period is conceptualized as a dynamic process that unfolds, presumably revealing more and more features as time progresses:

(18) Just an acknowledgment as it is unfolding … that there's someone specific you can talk to [WP4-T31-FA-11]

The use of the word “unfolding” here also hints at pregnancy loss being experienced as a narrative; the types of things that are most likely to “unfold” in British English are “events,” “drama,” “history,” “stories,” “changes,” “the future,” and “plots”13. The use of the word “unfolding” also implies a loss of control as the woman is not actively involved in the process. This is interesting as the women are clearly at the center of this particular “plot” but they are not always in control of it.

Our participants' use of metaphors such as these suggests that for them, the decision-making process is a lengthy and involved process; it requires time and patience, and the bereaved appreciate having someone to advise them throughout this.

At the same time, some participants displayed an awareness of the time pressure that they were under and of the need to make decisions quickly while they still felt capable of doing so:

(19) We knew we had to choose a name for our child because … our baby was [going to] die and they needed to have a name or we wouldn't be able to choose a name after he died because we knew we wouldn't be in the right headspace [WP4-T20-M-10]

This tension between the need to give people time and the need to encourage them to make decisions in a timely manner is likely to be one of the more challenging aspects of the bereavement care role following pregnancy loss.

As with the language used when they were receiving the bad news, the language people employed when describing the decision-making process also contained divided-self metaphors:

(20) I took that decision to end it … because you know I didn't want to do that part … the mother part of me didn't want to do that at all. I wanted to carry him and have him [WP4-T11-FA-3]

Although the idea of dividing one's identity into different roles is a fairly conventional one, here we see that the woman has already acquired a new role, that of the mother, and that this role is in conflict with the reality of the situation. This conflict is likely to make the decision-making process harder. The fact that divided-self metaphors were so common in our dataset (they constituted the eighth most used metaphor category overall) suggests that some acknowledgment of this need to split oneself into separate “parts” may be beneficial when helping parents make difficult decisions around termination and pregnancy loss more generally. Not only might it help people to distance themselves from difficult decisions, it also enables them to incorporate their identity of parents into their decision-making processes. However, these parental identities may make it more difficult to make the sorts of decisions that are being recommended by healthcare professionals, particularly following diagnoses of fetal anomaly.

We encountered varying degrees of agency in terms of people's divided-self and distancing experiences. Some of our participants reported that mentally they were not really “there” throughout the process. The significance of the event hit them much later on and support was needed when this happened, as we can see in excerpt 21, from a participant who had been diagnosed with a fetal anomaly:

(21) It was almost like at the time we were on autopilot … and if I was to say to someone in retrospect, I don't think we, I certainly didn't deal with it properly at the time … and that's I think why I sort of struggled with it last year, because I think it all just sort of slapped me with it sort of out of the blue. [WP4-T1-FA-1]

These findings suggest that support for the bereaved at the decision-making stage is likely to involve a degree of balance between competing factors. The bereaved value input and advice on what they should do, but at the same time, may have strong intuitions that may compete with the advice they are given.

When asked about how their choices had been communicated to them, some of our participants reported that the medical staff had, at times, been overly-directive:

(22) She didn't really feel like she … could make the decisions she wanted to, she was being pushed in certain … ways [WP4-T19-FA-8]

(23) You know, I felt very much that my hands were almost tied that you know they were sort of pushing me to go down the medical route [WP4-T15-FA-5]

Others regretted the fact that they had not been given sufficient information to help them make the decision:

(24) I just feel that we need to be very aware that everyone's going to handle this differently. It may manifest its way differently … we just need … really holistic options. Just options options options. It's amazing the informed consent—the proper informed consent … I gave consent to my surgery but … it wasn't proper. I was never given the actual statistics … we found out but yeah but you know I mean he [the consultant] could have been a lot nicer as well. For goodness sake I was like grieving I was in anger and denial. I was I was at those stages that are really raw. [WP4-T9-M-8]

This participant is clearly very aware of how confused she was feeling at the time. What she needed was clarity and genuine choice.

In some cases, women do feel the need to know all the details about their diagnosis and the procedures being offered to them, but this is not always offered. This is shown in this example of a woman being given the post-mortem results following a stillbirth:

(25) Just said oh I've got [the] results here and … says blah blah blah…So … can you just talk to me about it you know instead of—it's a heavily medical like report. There's a lot of words I don't understand … I'm probably capable but you have just take me through it … I just wanted to … have the opportunity to understand it … that's what I'd understood the appointment to be. To go through the post-mortem. Not sort of, here's your A-level results. Here's an envelope. Go away. You're done … maybe they need to be clearer that you've only got 10 min or whatever and if you've got other questions make another appointment or something. I just—it's such a short process that—I needed to understand all of it and so I did keep pushing and I didn't care how he was reacting to me cause I'm strong enough to just keep going and going even though he was getting more and more pissed off. Um, but it wasn't great and then since we've got friends who we've met through [NAME OF SUPPORT ORGANIZATION] actually who are both doctors and they took us through the report and they explained it to us and there were things that we hadn't understood that he didn't tell us. [WP4-T25-S-4]

The analogy with A-level results14 is interesting here because it points up the power imbalance and hierarchy between “teacher” and “pupil” but also conveys the sense that the “results” are being trivialized because they are not being explained and contextualized.

Taken together, these findings suggest that midwives may find it beneficial to ask the patients how much information about the procedures they would like to have, and to tailor the information according to the needs of the parents.

Implications for Care

These findings have several implications for healthcare professionals who provide care for those who have experienced pregnancy loss. A pertinent finding is that of the split self: when talking to someone who has suffered pregnancy loss, it is important to be aware that one is likely to be dealing with a person who is experiencing a series of competing and changing identities. These different identities may be pushing them in different directions, making decision making that bit more difficult. A possible resolution here could be to use communication styles which acknowledge and honor the views of the parents, and to make efforts to incorporate emotional concerns into the decision-making process where possible. The conflicting experiences of time at this stage in the process are also likely to present challenges; a certain amount of time is often required to make decisions, but the time available is likely to be limited due to medical or other practical concerns. It may be helpful to clearly state any time constraints when discussing options with the bereaved, while reassuring them that certain decisions can take more time. While it may not be feasible for caregivers in some roles to remain on-hand to provide support and advice beyond the immediate aftermath of the loss, it is at this stage that the bereaved could usefully be signposted toward other sources of support, e.g., pregnancy loss charities and any other local provisions. Finally, midwives should be led by the patients in terms of how much information they provide.

Perspectives of the Midwives

Midwives are aware that bereaved parents need time to make decisions, and that these decisions might change several times over the course of their loss. This is shown in excerpt 26, taken from a conversation about parents giving consent for post-mortem:

(26) Interviewee 2: But we would also take into consideration that … that's still what she wants [because] they do change their mind from one to the other. So a lady saying yes she does then she doesn't. And we've got to always … adhere to that. So if I'm working with a family or … our screening midwife who normally does all the post-mortem work, she would be in constant contact with them making sure that that's still the decision that they want to go with. [WP2-T10-BCP-05]

However, while the midwives were aware of how parents needed time to make decisions, many felt hampered by staff shortages which meant that they were often the only bereavement midwife working in the hospital. This meant that they were unable to provide the continuity of care they felt was crucial, and this often led to midwives feeling that they were “overloading” their patients with information in order to give them all they needed before they went off-shift:

(27) We have to do everything with them in the 1 day. Sometimes it can be a bit overbearing for them, because you're having to give them every bit of information in 1 day because … you know you're not going to see them the following day … that can be hard [WP2-T23-BCP-09]

It can be difficult for midwives to strike a balance between giving enough information and giving too much, and this is likely to vary greatly between patients as we saw above. The following is an interesting example of an approach which may not be helpful in some contexts:

(28) Interviewee 2: And so in my research and then in my work … I don't think they wanted the medical stuff do—they, they just want … you to be there and … they don't want all the rubbish that surrounds it.

Interviewer: Well, what medical stuff for instance?

Interviewee 2: They just want what they need. They don't want … all the information. They just want the information they need and the information that they want and what they don't want they don't … for instance [you] tell them that are we [going to] give them a tablet that will help them to pass their baby but they don't need to know … it's called Mifobristone and what it will do is help cells separate it…Because they don't care about any of that … that doesn't matter it's just it will help them pass the baby … will give them pain relief. When they need it. That's the biggest thing isn't it they need to know … That we can stop it hurting [WP2-T27-BCP-12]

Although this approach may be appropriate for some patients, it may be dangerous to generalize these ideas to the population of bereaved parents more generally, as some may well want to be provided with as much information as possible including drug names, formal names for medical procedures and detailed explanations of these.

Although many midwives in our study gave examples of cases where they had taken time to provide clear and complete information to their patients, some felt unsure as to whether the protocols and policies they were explaining adhered to best practice. Many of the midwives felt that they would have benefited from clearer guidance, and that existing guidance was not sufficiently clear or directive. More broadly, the role of the bereavement midwife itself seemed unclear to some participants, with many feeling the need to construct their job role for themselves. This forced some midwives to take the initiative to construct their own support networks to clarify their roles and to train and support others:

(29) I run a bereavement midwife forum, because … this was quite … an isolating role … I felt really … sort of just alone, doing this, I didn't know really if I was doing the right thing, there was no … job description from anywhere [WP2-T1-BCP-01]

This was mirrored, in many cases, by a perceived lack of recognition of the role of the bereavement midwife within the hospitals, manifested through a lack of support, staff shortages, and insufficient time to perform their bereavement support duties. Structural issues within the hospital sometimes exacerbated this issue, with several midwives speaking of the challenges they faced in dealing with a high staff turnover (particularly among junior doctors), and difficulties in providing training to staff elsewhere in the hospital.

(30) Interviewee 1: I've just done a … presentation, “a day in the life of me,” particularly for management. Because I … don't think they appreciate what a bereavement role entails. It's not just caring for parents, it's doing everything else, it's liaising with mortuary services, liaising with crematoria … supplying figures [WP2-T17-BCP-07]

Our findings from this part of the study clearly indicate a need for more clarification of the role of the bereavement midwife, among bereavement midwives themselves and across the medical community more generally.

Deciding on How to “Look After” the Baby After Delivery

Views of the Bereaved

The most frequent metaphors observed when participants were talking about how to “look after” the baby after delivery are shown in Table 4.

Table 4. Most frequent metaphors observed when participants were talking about how to “look after” the baby after delivery.

In the Methodology section above, we introduced the idea of a tension between the desire to parent the baby and the need to organize his/her funeral. This tension is made manifest in the most frequent metaphors occurring in relation to this key moment. Metaphors of animacy, presence and absence, and letting go are notable here, along with metaphors of movement and reification already observed.

The majority of the participants we interviewed expressed a strong, emotional attachment to their baby's body. Many parents reported that it had been good to hold the baby's body after the procedure or the birth, but some expressed concern about the way in which this option was presented to them and the timing of the question. In one case, where a participant was going to have to give birth to a stillborn child, the hospital staff asked her and her partner whether they would want to hold the baby afterwards. They felt as if this had been the wrong time for the question to be asked as their view of the baby at that time was very different from their view of the baby after labor had been induced:

(31) I don't think it should be a pre-asked question … I think that's the biggest thing [because] they asked me this question on the Thursday. The day before I actually had him and at the time like said he was just at the time…when I was asked on the Thursday he was a problem. He was a dead baby inside of me … he was a problem … But because they'd asked me the question I had that doubt in my head of do I want to hold him would I want to hold him? Will I look at that baby and want to hold that baby. It's a dead baby. And it was only [because] me and my husband spoke and said we can't not hold him. We've got to hold him. But I think that if I was asked after I'd … had him and a midwife had been holding him and said here's your baby. Do you want to hold your son? That to me would be really different to being asked when you're not I don't know. [WP4-T28-S-7]

In their case, the situation had changed from a “problem to be solved” to “a baby to be grieved.” This reflects a change in the level of “animacy” ascribed to the baby. The woman went on to say:

(32) [I] just think it would've been a very different way [because] I think that a lot of women would then be able to see okay that's my son yes. Of course … I want to hold him. And I think that that's probably a different way around of maybe asking somebody as opposed to sort of that … everything that they asked felt very clinical. Very processed … as opposed to … how a friend would … ask you if you had a friend there who was kind of like dealing with everything for you then … I don't know they might clean the baby up if … you [want to] look at your baby. Look at how lovely they are. Look at the—it's the way of—rather than making it feel like it's a process that … you need to kind of go through … this this this this this this and this and there's your dead baby at the end of it … it almost needs to be … done in a, how a friend would kind of help you through something [WP4-T28-S-7]

For this woman, not only was the timing of the question crucial, but also the way in which the question was phrased. For her, and for many others (particularly those who had stillbirths), the baby needed to be treated, at least on one level, as if it was “alive” at the point of birth. Normally the term “animacy” is used when inanimate objects are talked about as if they are alive, but here we are extending the concept slightly to include cases where people talk about the dead as if they were still alive. We see other examples of this “animacy” metaphor in the following excerpts:

(33) I said I want him to go outside, I want him to see stars, and my husband went, “oh right, okay” and he picked him up and he walked him outside the fire exit and stood outside with him for a couple of minutes, and then afterwards I was thinking, well, I should've been supported by the midwives to get into a wheelchair and spend some time sort of outside with him or sitting outside … underneath the stars. But I was made to feel that wasn't an option. [WP4-T28-S-7]

(34) We are parents. we've got a … little girl. She's not here. She's not with us. But we have you know we've got we have got a little girl. [WP4-T29-S-8]

In excerpt 33, we see the parents wanting their baby to experience something of “life” and in excerpt 34 we see them seeking to give the baby an identity external to her parents. A common theme running through our participants' responses to questions about the way they perceived their baby was that their attitude toward the baby had changed significantly during the process. All these attitudes can be valid at different times and for different individuals, and it is of little use to attempt to impose any kind of over-riding “logic.” An implication of this for those responsible for caring for people who have experienced pregnancy loss is that they need to prepare for the possibility that people will change their minds, that parents need to be able to make unhurried decisions, and that decisions made early on in the process may not, in the end, turn out to be the “right” ones. Timing is crucial.

The fact that people think of their new-born baby as a living being, particularly in the case of stillbirth, also extends into non-verbal metaphor (see Jensen, 2017) as we can see in excerpt 35 below, in which a woman talks about how unhappy she was that medical staff would stand between her and her baby in his cot:

(35) If you come into a room with a normal … healthy baby … then you would never dream of ignoring that baby. Whereas, the cot was … put a little way away from the bed … And they would stand in between the cot and the bed which got to me more than anything because it was almost like they were ignoring the fact why I was in there in the first place … for them it was easier to stand in the way of it so they didn't have to acknowledge that he was there [WP4-T23-S-3]

This excerpt shows that metaphor extends beyond words and also appears in people's actions. The fact that the nurses positioned themselves physically between the bereaved mother and her baby's cot was seen as a physical embodiment of the idea that the nurse did not see her baby as “important.” In the eyes of this mother, the midwife appeared not to see the baby as a human being; she was literally disrupting the physical-spatial relationship between mother and child. In relation to this, an over-riding theme in the interviews was of a need for the parents to have an acknowledgment that the baby existed:

(36) We haven't moved on, like, ‘[NAME]'s gone now, let's get on with our lives'. He's part of our lives. We make sure that that [SIBLING] is aware of him but you reach a point where you sort of—you do move on. He's still part of it but you've [got to] live your life [WP4-T34-S-P3]

(37) That baby was here in your heart … no matter what anyone else says [WP4-T12-M-9]

Because the participants were being interviewed at least 6 months after the pregnancy loss had taken place, many were able to acknowledge this temporal perspective. Some acknowledged that it is possible to feel very differently about their baby further down the line:

(38) It's okay to have these experiences with your child because that is your son … it's not a dead baby. It's your son. It's your daughter. And that's the way you will view them going forward. You won't view them as being this problem, this stillbirth, this death that's happened, this process…That's how it's dealt with at the time but you will view them in the future as being your son. Your daughter. And then you'll look back and regret not treating them that way [WP4-T28-S-7]

By noting that the baby is considered a “stillbirth” or “a death that's happened” at the time of the loss, this woman is describing a use of metonymy which may help to objectify what has happened and make the process more manageable in the immediate aftermath of the loss. However, as she notes, these metonymic conceptions of the baby will not seem as relevant as time goes on.

A further interesting use of metonymy is found in descriptions of how the bereaved continue enacting parenting behaviors even after the baby has been cremated, as shown in excerpts 39 and 40 below:

(39) I literally carry her [i.e., her ashes] everywhere, even now. Like, we take her upstairs, take her downstairs … [T10-FA-2-SKW]

(40) We were going to scatter his ashes on his due date but I don't feel ready to let him go. I just like knowing he's in the house. I just—I just don't want to let him go right now. And I don't know if I ever will, I just—we don't have a special urn or anything. He really is just stashed away in a sideboard but I just like knowing he's at home with us. [WP4-T20-M-10]

In both these excerpts, the metonymy is found in how the ashes stand for the baby, reinforced by the use of the personal pronouns “her,” “his,” “him,” and “he.” There is a further metonymic relationship in the second excerpt which shades into metaphor, in that literally scattering the ashes (metonymically standing for the baby) equates to metaphorically letting go of the baby.

Implications for Care

We have already discussed some of the implications of these findings in the preceding section. The main messages that we can take from this section are that it is important to note that people's attitudes toward the baby can change quite significantly over time, for many the baby is on some level still very much “alive,” and that metaphors of pregnancy loss can be enacted as well as simply appearing in the language used. This is particularly relevant in the case of stillbirth, but may not be exclusive to it. If someone wants to show their baby the stars, it is important to let them do so. The best support for the bereaved at this stage therefore involves validation of their loss, and a willingness to take the lead from the parents.

Perspectives of the Midwives

The midwives who we interviewed were very much aware of the importance for many women of the fact that this was their baby:

(41) You need to make it known that you're … [there] to help them. And that you … care that they've lost their baby … Yeah that's a massive thing that their baby is important to us … and because we're one of the only people that are [going to] meet their baby … even if they're 16 weeks their baby's their baby [they are] parents now … And yeah we're one of the few people that are ever [going to] meet their baby and know that their baby existed and I think that's a massive thing to them … because the rest of the world don't know or their families don't understand … But we've met their baby and we know [WP2-T27-BCP-12]

This genuine care translates into a passion for supporting memory-making in a respectful and dignified way. This is not dependent on gestational stage:

(42) Interviewee 1: If I've got somebody on the ward who has had an 8 week miscarriage, to me it doesn't make any difference. They've still lost their baby, and we treat it exactly the same. [WP2-T23-BCP-09]

However, they were also aware that this was not a universal experience and that they should be led by the patient:

(43) It's a miscarriage, they don't want to see it, they just want to go home and move on. Doesn't happen all the time, but it does happen [WP2-T16-BCP-06]

One midwife spoke of the difficulties in working out whether the decisions being made are born of trauma or whether they are decisions that the bereaved will continue to hold; sometimes it is very difficult to make the call:

(44) That is often, a really … positive and helpful thing for the families that choose to do it. But I would never … [the] skill in bereavement care is being with the family and recognizing when somebody's telling you that they don't want to see their baby, they don't want handprints and footprints and photographs, that that is their decision. Versus somebody that is telling you is … terrified … who is in shock and hasn't maybe considered the value of doing these things or having these things and maybe needs some support … reassurance … and coaching through that process … the skill is picking out those mums, and not … distressing the ones that have made their decision that you're trying to talk them out of it. [WP2-T16-BCP-06]

The midwives were also aware of the fact people's attitudes could change very significantly over time and that people therefore needed to be given opportunities to change their minds and ongoing support through the process. We can see this in the following excerpt:

(45) I had a set of parents who are always in my head, and they know it … big family, and … they had a little boy…they were so shocked they didn't want to do anything and I went to see them on a Friday … they were sitting with their coats on waiting to go home … mum had seen the baby very, very briefly. Dad didn't want to see it at all … they were just waiting to go, but they'd been told that this person called [NAME] was going to come and see them before they went … I could have taken a photograph of them … I wish I'd have had the courage to do it, but I didn't … they'd been told … you can do this, you can do that. They didn't want to do anything, they just wanted to go home … I went to see them and it wasn't just because it was me … it could have been another bereavement midwife. You just put those few words and few ideas, and they stayed within the hospital until Sunday afternoon. Initially they hadn't wanted anything … but over the weekend, they saw their baby, they bathed their baby, dressed their baby, took hundreds of photographs. The rest of the family came in, because that baby would have been part of a big family … they ended up with an album that was six inches thick … from beginning, right to the funeral, with flowers and everything. But initially they hadn't wanted anything…if we hadn't given them the time, they'd have gone home and they'd have done nothing … but they did absolutely everything … I think parents are … sometimes really frightened. If they don't want to see their baby straightaway, they think ‘does that make me a bad parent?' “Does that make me a bad person?” and we just give them time, and if they still decide … that that's not what they want, you know, we give them the options and we support them, but it's their choice. But we have very few parents that go home, from delivery suite anyway, that don't see their baby. [WP2-T17-BCP-07]

These comments underscore the crucial role played by bereavement midwives in helping bereaved parents to enact parenting behaviors that will help them through the difficult aftermath of pregnancy loss. The skill lies in deciding if, when and how to help them engage in such behaviors.

Funerals, Rites and Rituals

Views of the Bereaved

In this section, we focus primarily on stillbirth. This is because under English law, the context in which this research was conducted, a stillborn baby must be buried or cremated by law. However, it should be noted that some of the sufferers of other types of loss also arranged funerals.

The most frequent metaphors observed when parents were talking about the funeral arrangements for their baby are shown in Table 5.

Table 5. Most frequent metaphors observed when participants were talking about making decisions about funerals, rites and rituals.

Again, we see metaphors involving reification, animacy, containment, movement and physical location, but we also see metaphors involving ties and bonds and nature. In this section we discuss how the use of these metaphors reflects the tensions that we have discussed throughout this article that emerge when a parent has to bury their baby. In the section Deciding on How to “Look After” the Baby After Delivery, we saw that for many people, it is hard to reconcile the fact that their baby has died with the identities that they have been developing as parents and the associated need to enact parenting behaviors.

The mindset that led the parents to want to parent their babies continues to inform the decisions they make about funeral arrangements. Therefore, we still see a number of animacy metaphors in which the bereaved talked about their deceased baby as if he or she was still “alive.” Many parents did not want their baby to be on their own and this informed their decisions about the funeral:

(46) She's buried with my dad … I didn't want her to be on her own, um, so she's with my dad, um, in [PLACE] cemetery [WP4-T29-S-8]

This excerpt underscores the importance for many parents of the need to treat the baby as a person, as we saw in the previous section. It also links back to the quotation above about the family coming in to visit the baby. Both of these quotations show that, in addition to being seen as a person in his/her own right, the baby is also very much part of the family and has thus already begun to form part of a network of social relationships.

The issue of timing also plays a key role with respect to the questions that are asked about funerary arrangements. Here a participant who had experienced a stillbirth comments that it would have been more appropriate to have been asked about her preferences for funeral arrangements after the induction, rather than before:

(47) I know that they have to ask the questions but like I said when they come in with the clipboard and the piece of paper and it's a tick sheet and you're having … question after question after question and … they're asking about funeral stuff and they're sitting with me and my husband and we're like well we haven't even considered a funeral. Why would I know the answer to that? I don't know the answer to that and…I don't think it was necessarily the right time to ask about the funeral. Before he was born. I think that that should have, could have, waited until after the birth … After everything'd calmed down. After everything I think that would've been a better time to ask. [WP4-T28-S-7]

When asking parents to make decisions about funeral arrangements the issue can be broached prior to the loss. However, parents need to be given time to make the final decision after the loss has taken place, if possible, as they often view their baby in a very different way after this has happened.

The connections that people felt to their babies are reflected in the use of metaphors related to ties and bonds. Although for many, creating a “bond” with their new baby was deemed to be important, for some, the idea of being “tied” to their baby's memory was worrying and it made them not want to have a grave. We see this in the following comments, the first of which was produced by a participant who had experienced a miscarriage, the second a stillbirth:

(48) Our worry about having a burial is that then there's a grave that you have to visit. And you're tied to that grave. And we both thought that we would never be able to move on from the loss of our child. [WP4-T20-M-10]

(49) I don't want a tie. That sounds very selfish but I didn't want a tie to a specific place [WP4-T26-S-5]

Finally, metaphors relating to nature demonstrate how people attach symbolic meaning to natural phenomena in order to help them come to terms with the death of their baby. While not specific to formal funerals, nature often played an important role in the personalized rituals that the bereaved and their loved ones undertook following loss. Here we have a parent talking about how her friend planted a snowdrop in honor of her stillborn baby and how much this meant to her:

(50) Some people unexpectedly were just so appropriate and lovely anyway I have a friend … who just came up trumps … planted a snowdrop. And every year I get a picture of how this snowdrop's doing [WP4-T26-S5]

Here the snowdrop appears to metaphorically represent her baby and she is able to see it grow. The symbolic importance of nature also led this parent to be hesitant to engage in some memorialization activities:

(51) There was a little flower [in the memory box] but I was too scared to grow the flower in case it died. I have a rose in the garden and the rose didn't do very well this summer and my mum was like, now, you're not to think this as any sort of reflection on what happened. I was like, “no no no, it's fine. It's fine.” But I wasn't ready, for some reason, for the flower in the box. it was too soon to have that sort of rational thinking about, “it's just a flower.” [WP4-T26-S5]

Taken together, these excerpts demonstrate the power of nature as a metaphorical resource upon which bereaved parents can draw. However, they need to do so on their own terms and in their own time.

Implications for Care

All of the metaphors discussed in this section work together to show how memorialization rituals, including funerals, are important, but that parents vary significantly in terms of what they deem appropriate. For carers, the main message to be taken from these findings is that we should expect a degree of variety and that parents have very different needs when it comes to making decisions about funeral arrangements. Decisions about whether, and if so where, to bury the baby's body can be very difficult to make, as parents need to take into account both their current and their perceived future relationship with their baby.

Perspectives of the Midwives

Midwives recognized the fact that people vary in terms of whether or not they want a funeral for their baby and if so the kind of funeral they want. They noted that people with earlier losses often wanted some kind of funeral service too. However, it was noted that procedural demands and administrative errors sometimes made the process much more difficult for parents than it needed to be:

(52) We also had a problem 6 months to a year ago the lady that sorts out releasing the body to the parents for the cremation, the body can't be released if certain forms aren't filled in properly and nobody will take responsibility for this form that wasn't filled out. So the poor parents were ringing every day we want our baby and we couldn't give them their baby [WP2-T26-BCP-11]

We had a number of accounts of midwives going to great lengths to smooth the process when this sort of thing happened:

(53) Interviewee 2: If they want to arrange it themselves or do we contact the … funeral director for them? We've got a good funeral director don't we?…will take the babies really early gestation won't they, I think, and does it for free. I understand because of personal reasons they offer it free?…and then they collect them from the mortuary and then just deal with it and contact the family. I just work my way through the paperwork and then discuss it as it is on the paperwork [WP2-T27-BCP-12]

Even when the funeral arrangements went smoothly, midwives spoke of engaging in activities that went beyond the job description, including reading out a poem at the remembrance service and creating a Facebook page for parents and grandparents.

This perceived need to exceed the expectations of their job description sometimes adds stress to the midwives' personal lives:

(54) Interviewee 1: Little silly things that … have a massive impact, or—say for instance I've booked a funeral for somebody and then the doctor that was going to do the cremation form goes off sick. That kind of thing keeps me awake at night thinking, I really want to get this form done, I don't want to have to phone this family and say I'm going to have to cancel the funeral because I can't get the cremation paperwork done. [WP2-T16-BCP-06]

Our analysis of the interviews with the midwives show that they were aware of the need for choice around the types of funeral. However, midwives also highlighted the institutional constraints where they worked surrounding hospital-provided funeral services. In some cases, for example, parents were not permitted to attend the services organized by the hospital for miscarried babies, but midwives recognized that parents should have the option to do so. This is also stated in the guidance offered by the Institute of Cemetery and Crematorium Management (ICCM). In many cases, therefore, institutional demands rendered it very difficult for the midwives to provide the care and the choices that they knew the bereaved parents needed.

Conclusion and Implications for Practice

In this paper, we have seen that metaphor is a useful tool in providing insights into people's experiences of pregnancy loss. Our analysis has shown that their heightened emotional state means that they find it difficult to take in a lot of information at once, their feelings fluctuate considerably and this has implications for the decisions they make. Many take on identities as parents which they enact in a variety of ways, and this can impact on their choices for funeral arrangements. However, there is considerable variation in their experiences with some patients viewing the lost pregnancy in more medical terms. In many ways, our findings cohere with previous work on the role of metaphor in gaining insight into the experiences of those who have suffered trauma, ill health or addiction as discussed in the Introduction and Background to the Study sections. In those cases, metaphor has been shown to be a powerful therapeutic tool, helping people to reframe their experiences and eventually to replace their painful conceptualization with ones which are more hopeful (see also Tay, 2013 for a more in-depth discussion of the use of metaphor in therapeutic contexts). While such an approach is beyond the scope of our study, it therefore seems likely that a metaphor approach would also prove beneficial in supporting those who have suffered pregnancy loss in a therapeutic context.