- 1Department of Political Science, University of California, Santa Barbara, Santa Barbara, CA, United States

- 2Climate Advocacy Lab, San Francisco, CA, United States

Building public will to address the climate crisis requires more than shifting climate change opinion or engaging more people in activism. Despite growing activism, the climate movement still needs to do more to translate public action into the power needed to effect meaningful change. This article identifies the kinds of research questions that need to be answered to bridge the gap not only between opinion and action, but also between action and political power. We draw on discussions from a conference that brought social scientists together with climate advocates in the United States. At this conference, movement leaders argued that to better support building a robust climate movement, research should move beyond traditional public opinion, communications, messaging, and activism studies toward a greater focus on the strategic leadership and collective contexts that translate opinion and action into political power. This paper thus offers a framework for synthesizing research on movement-building that demonstrates ways to focus research on power, and emphasizes the importance of organizing collective contexts in addition to mobilizing individuals to action.

Introduction

Building public will to address the climate crisis requires more than shifting climate change opinion or engaging more people in activism (Raile et al., 2014). By many measures, the climate movement today is stronger than ever: more people taking actions, more financial resources, and deeper concern. Nonetheless, despite increasingly widespread popular demand for sensible climate solutions (Leiserowitz et al., 2017; Hestres and Nisbet, 2018) and broad organizational infrastructure to support climate activism across most Westernized democracies (Brulle, 2014), public will that translates into the political power needed to effect meaningful change has been elusive (McAdam, 2017). Even the 2014 and 2017 People's Climate Marches that drew hundreds of thousands to the streets, demonstrations in support of the Paris Climate Accords, and large-scale acts of civil disobedience in opposition to the Keystone XL and Dakota Access pipelines have resulted in only short-lived campaign victories. Nearly 10 years after the failure to pass comprehensive climate and clean energy legislation at the federal level, experts largely agree there is “little hope” existing policies are sufficient to address the scale of the crisis (Keohane and Victor, 2011).

How can research help bridge the gap not only between opinion and action, but also between action and power? Many articles in this special edition examine the question of the conditions that make it more likely individuals will take action around climate issues. Indeed, the gap between opinion and action is well-known (Kahan and Carpenter, 2017), and burgeoning research in many fields of social science seeks to bridge it (Rickard et al., 2016; Doherty and Webler, 2016; Feldman and Hart, 2018). One of us works for the Climate Advocacy Lab, which supports field experimentation through direct funding and in-kind research assistance to build our collective understanding of the most effective strategies for moving people into action.

There is less attention, however, to the question of how those actions might translate into political influence. The challenge is this: in most cases, the null assumption is that activism becomes power at scale: that collective action is merely the sum of its parts, and the more people who take action, the more likely a movement is to achieve its goals. All things being equal, it is true that more is better (Madestam et al., 2013). Additional research, however, shows that for our stickiest social problems (like climate change), simply having more activists, money, or other resources is not sufficient to create and sustain the kind of large-scale change needed (Baumgartner et al., 2009; Canes-Wrone, 2015). Instead, we need a social movement that translates our actions into power. Social movements are a set of “actors and organizations seeking to alter power deficits and to effect transformations through the state by mobilizing regular citizens for sustained political action” (Amenta et al., 2010). Instead of focusing only on resources, movements focus on power. Instead of focusing only on individual action, they focus on collective action. To become a source of power, collective action must be transformative.

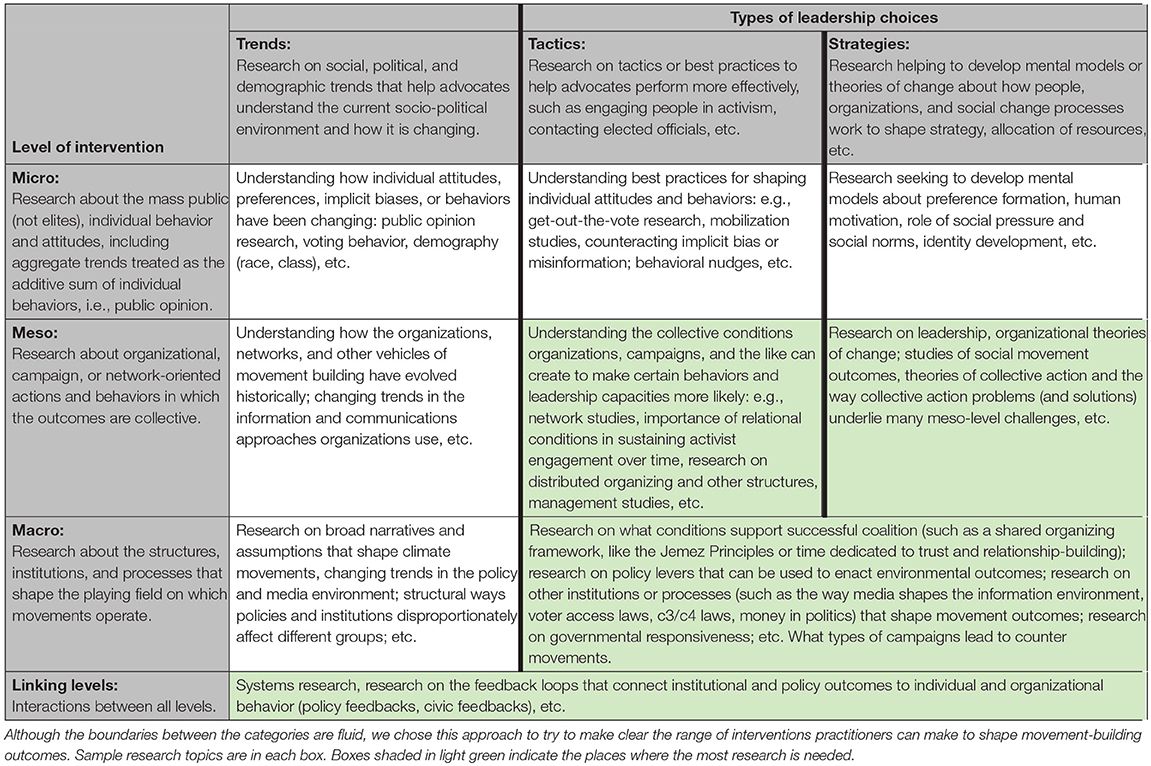

How, then, do we build the kind of movements that generate the collective action necessary to shift existing power dynamics? For scholars, what research can help advocates understand how to translate individual actions into the powerful, and transformative collective action necessary to create change? To examine this question, we co-hosted a conference that brought social scientists together with climate advocates in the United States. At this convening, movement leaders argued that to better support building a robust climate movement, research should move beyond traditional public opinion, communications, messaging, and activism studies toward a greater focus on the strategic leadership and collective contexts that translate opinion and action into political power. This paper thus offers a framework, described in Table 1, for synthesizing existing research on movement-building and highlighting the places where additional research is needed. We hope this framework can help focus more future research on the collective, relational contexts and strategic leadership choices necessary to generate collective action that translates into power. In describing the framework, we draw on Slater and Gleason's (2012) typology to show what we know and do not know about supporting movement actors seeking to make more impactful choices.

Assessing the State of Research on Climate Movement Building

How do movement leaders translate supportive public opinion and grassroots activism into political influence? Answering this question rests on first understanding a few key points about social movements. First, movements operate in an environment of uncertainty. For the climate movement, everything from oil spills to hurricanes, domestic elections to international treaties, legal decisions, and market forces can affect the terrain they must navigate. Movement leaders cannot directly control many of these things. Second, policy change is not power. A given policy change will not automatically effect change in the world consistent with movement interests (Hacker, 2004). Moreover, policies can be easily overturned, as exemplified by the transition from Obama to Trump, and immediate rollback of key policies including the Clean Power Plan, restrictions on drilling and mining on public lands, and coal ash protections. To create lasting power, movements need broad constituencies that persist through the ups and downs and whims of different administrations. Third, there is no direct line from activism to power, because power is a dynamic relationship between movements and their targets. To wield power, movements use their resources to act on the interests of political decision-makers (Hansen, 1991). In fact, some research suggests the advocacy group resources most predictive of large-scale policy change are relationships with decision-makers—more so than lobbying money, campaign contributions, or the number of grassroots members (Baumgartner et al., 2009). Some argue that the climate movement's failure to build and sustain the kind of constituency that would pressure decision-makers contributed to the failure of cap-and-trade legislation in 2010 (Skocpol, 2013).

Given these three factors—persistent uncertainty, the need to focus on power not policy, and the complex interests of movement targets—what are the questions movement leaders need to answer to build a more effective climate movement? We argue that most research has focused either on documenting trends in the political environment in which movements work or on questions of how the movement can focus on building more of its resources (such as more supportive public opinion or more activists). Those questions are important. Particularly in today's uncertain, dynamic political environment, however, we also need research on strategy: how do movements create the leadership capacities and organizational (or “meso-level”) conditions needed to navigate uncertain political situations and shifting relationships, and thus translate resources to power?

Organizations that have successfully wielded power in other issue areas can be instructive in showing why understanding strategic leadership and meso-level, collective contexts matters. Consider the gun debate in the United States. Polls show strong public support for stricter regulation of guns, advocates like Michael Bloomberg have poured hundreds of millions of dollars into the fight, and protests have brought millions of people into the streets for gun control. Nonetheless, the National Rifle Association (NRA) has been more effective in translating its activists and resources into political power. Why? First, leaders within the NRA undertook an intentional campaign to build an ardent constituency of gun owners that was willing to stand together, again and again, through ups and downs of any political fight, to support gun rights. As recently as the early 1970s, the NRA supported sensible gun regulations. Beginning in the 1970s, however, a group of hardline conservatives took control of leadership of the organization (Melzer, 2009). To build constituency, they used three key tactics: widespread benefits provided to gun owners from the national organization, strong appeals to identity, and a complex latticework of interpersonal relationships sustained at the local level (LaCombe, forthcoming). Second, leaders strategically leveraged this constituency to negotiate relationships with the Republican Party. The recurrent ability of leaders to deliver support from this constituency for policymakers became the basis through which the NRA built high-level relationships with elected officials and the Republican Party, thus cementing its hold over gun policy in the United States. By linking base-building with elite politics, the NRA transformed the political dynamics around gun rights.

The story of the power of the NRA in the last generation, thus, is a story about strategic leadership choices, and particular choices about how to leverage meso-level, collective contexts to shape a new kind of constituency around gun ownership. The NRA's base was built through work they did to create organizational settings around the country in which people developed collective identities as gun owners, and undergirded those identities with overlapping networks of relationships.

Research on climate activism, however, is not as robust on questions about strategic leadership or meso-level contexts as it is on questions of individual behavior and opinion change. How can the climate movement learn to build the same kind of strategic leadership and politically influential organizations from a durable, coherent constituency? The diffuse ecosystem of climate and clean energy advocacy organizations coupled with the complexity of the issue and requirement of significant cultural and economic shifts to address systemic drivers of the problem—necessitate deeper, evidence-informed recommendations from the academic community. Answering these key questions will require additional research on meso- and macro- level leadership choices, as depicted in Table 1.

Table 1 provides a framework for research on movement-building to show where questions about strategy and collective action can fit alongside existing work. The columns in Table 1 distinguish between research that documents trends, or political conditions that shape the work movements do, and leadership choices, or the kinds of tactics and strategies movements can use. The rows depict the different levels at which trends can be studied or advocates can make interventions: individual (micro), organizational (meso), and institutional (macro). Examples of the kinds of research topics that fall into each category are listed in the boxes. We are not claiming this is a comprehensive overview of climate movement research, or the only way to organize the research. Instead, it emerged from our conversations with advocates and is intended to sharpen our understanding of the places where research can support their work.

Looking first at the columns, we argue that we have more research on trends and tactics than we do on strategy. A robust body of research on social movements focuses on the external political conditions, or trends, that make movement outcomes more likely—for example, how partisan majorities in legislatures shape outcomes (see e.g., Amenta et al., 2010 for a summary). The power of structural trends in shaping political outcomes makes this a fertile area of research. Advocates argued, however, that although they need to understand those trends, they also need research on actionable choices where they can exercise agency, however, marginal the effects may be. Thus, the second and third columns examine choices movement leaders can make to increase the likelihood they will build the collective power need to win. In looking at these columns, however, we argue there is more work on tactics (such as questions around what kind of messaging is most effective) than strategy (such as broader questions asking which theories of change are most effective under what conditions), with most research focusing on the question of generating individual (micro-level) action.

Looking at the rows, we argue that there has been much more research at the micro-level, tracking the causes and consequences of individual behavior and opinion, than research at the meso or macro levels. Developing research at the meso-level can help movement leaders work smarter, not just harder, allowing them to more effectively mobilize resources in support of strategies and tactics that support collective action and build power. Focusing only on the attributes and behaviors of individuals at the expense of the meso-level can limit movements in two ways: first, it leaves many organizations struggling to scale outreach to ever larger groups of individuals; second, it focuses on selection instead of socialization, limiting our understanding of how to generate activism to the kinds of people who are easiest to activate, regardless of whether of those constituencies are the ones most essential to long-term power building efforts. This approach also can ignore the many ways in which people's citizenship is shaped by social and collective contexts, the relational processes that make movements work, and the way those contexts vary across diverse groups. Research shows the most durable, powerful constituencies emerge from collective contexts that transform people's interests, capabilities, relationships, and commitment to each other (Han, 2014). Just as gun clubs are crucibles for constituency-building in the NRA, so too were churches in the Civil Rights Movement, and locally created efforts to shut down bars in the temperance movement at the turn of the twentieth century. What is the equivalent for the climate movement? Environmental organizations have long been organized at the local level, around community-focused campaigns, fighting toxic waste facilities or coal-fired power plants, as well as shared interests in activities such as birds or hiking. More work can be done to parlay their large, dedicated member based into a politically powerful constituency.

There is also further work to do at the macro level, and linking across levels. How do climate and clean energy-focused organizations operating at sub-national, national, and international levels coordinate and collaborate more effectively to be mutually reinforcing? How do movement organizations create the conditions that make it likely their leaders will have the strategic capacity to figure out how to turn the resources they have into the political power needed to address the climate crisis (Ganz, 2000)?

In sum, we argue that existing research has taught us most about the micro-foundations of opinion and behavior on the climate (the top row), and the socio-political trends (the left column) that shape a movement's ability to achieve its goals (Amenta et al., 2010; McAdam, 2017). In Slater and Gleason's (2012) framework, much of the research on these topics would fall into what they refer to as Strategy 2, 3, or 4—in other words, this is an area in which a great deal of robust theory has been developed and scholars are doing studies to better understand how the theories apply in different contexts, what variables mediate and moderate the effects, and what some of the indirect pathways to change might be.

Relatively speaking, we have much less research on the strategic leadership choices that can be made at the meso and macro levels to build the climate movement we need (highlighted in green on the table). At the conference, advocates argued that more research is needed in these areas to offer leaders guidance on how to move beyond motivating individual actions toward building collective constituencies that have the flexibility and commitment needed to act on the interests of public officials over time, even as external conditions and internal movement priorities shift. Although important foundational research in this area exists, more work is needed, given the challenges of the current political context. In Slater and Gleason's (2012) framework, we would argue that research in this area is more at the stage of what they define as “theory development,” which is strategies 6 and 7 in their typology.

Conclusion

The Social Science Citation Index lists over five thousand research papers published over the last 5 years that reference “climate change” or “global warming,” offering insights for organizations at the micro and meso-level of intervention, helping inform the climate movement's approach to strategy, tactics, and communication. This body of research has contributed to the success of a number of important campaigns from stopping the construction of fossil fuel development and distribution infrastructure to shaping renewable energy portfolio standards to informing tactical decisions around decisionmaker contact and digital communications.

In our work with climate advocates, however, we hear that more research at the macro-level is needed to support decision-making around movement strategies. In particular, researchers can make an invaluable contribution toward addressing the climate crisis by helping to identify choice points that make it more likely movement leaders will build sufficient, lasting political power. Movement leaders are obviously not the only audience researchers seek to reach in building a knowledge base about the climate movement; but for a body of work focused on such an urgent and critical topic, movement leaders are certainly a relevant audience. This paper is an effort to organize research in a way that helps speak to their needs. Through this kind of research, we can learn to build vehicles that will translate people's actions into political voice.

Author Contributions

HH and CB-L contributed equally to the intellectual development of this paper. HH took the lead in writing.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Amenta, E., Caren, N., Chiarello, E., and Su, Y. (2010). The political consequences of social movements. Ann. Rev. Sociol. 36, 287–307. doi: 10.1146/annurev-soc-070308-120029

Baumgartner, F., Berry, J. M., Hojnacki, M., Kimball, D. C., and Leech, B. L. (2009). Lobbying and Policy Change: Who Wins, Who Loses, and Why. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. doi: 10.7208/chicago/9780226039466.001.0001

Brulle, R. J. (2014). Institutionalizing delay: foundation funding and the creation of U.S. Climate Change Counter-movement Organizations. Climate Change 122, 681–694. doi: 10.1007/s10584-013-1018-7

Canes-Wrone, B. (2015). From mass preferences to policy. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 18, 147–165. doi: 10.1146/annurev-polisci-050311-165552

Doherty, K. L., and Webler, T. N. (2016). Social norms and efficacy beliefs drive the Alarmed segment's public-sphere climate actions. Nat. Clim. Change 6, 879–884. doi: 10.1038/nclimate3025

Feldman, L., and Hart, P. S. (2018). Is there any hope? How climate change news imagery and text influence audience emotions and support for mitigation policies. Risk Anal. 38, 585–602. doi: 10.1111/risa.12868

Ganz, M. (2000). Resources and resourcefulness: strategic capacity in the unionization of California Agriculture, 1959-1966. Am. J. Sociol. 105, 1003–1062. doi: 10.1086/210398

Hacker, J. (2004). Privatizing risk without privatizing the welfare state: The hidden politics of social policy retrenchment in the United States. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 98, 243–260. doi: 10.1017/S0003055404001121

Han, H. (2014). How Organizations Develop Activists: Civic Associations and Leadership in the 21st Century. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199336760.001.0001

Hansen, J. M. (1991). Gaining Access, Congress and the Farm Lobby, 1919-1981. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Hestres, L. E., and Nisbet, M. C. (2018). “Environmental advocacy at the dawn of the trump era: assessing strategies for the preservation of progress.” in Oxford Encyclopedia of Climate Change Communication, eds L. E. Hestres and M. C. Nisbet (New York, NY: Oxford University Press).

Kahan, D. M., and Carpenter, K. (2017). Out of the lab and into the field. Nat. Climate Change 7, 309–311. doi: 10.1038/nclimate3283

Keohane, R., and Victor, D. (2011). The regime complex of climate change. Perspect. Polit. 9, 7–23. doi: 10.1017/S1537592710004068

LaCombe, M. (forthcoming). The political weaponization of gun owners: the nra's cultivation, dissemination, and use of a group social identity. J. Polit.

Leiserowitz, A., Maibach, E., Roser-Renouf, C., Rosenthal, S., Cutler, M., and Kotcher, J. (2017). Climate Change in the American mind: March 2018. New Haven, CT: Yale University and George Mason University, Yale Program on Climate Change Communication.

Madestam, A., Shoag, D., Veuger, S., and Yanagizawa-Drott, D. (2013). Do political protests matter? evidence from the tea party movement. Q. J. Econo. 128, 1633–1685. doi: 10.1093/qje/qjt021

McAdam, D. (2017). Social movement theory and the prospects for climate change activism in the united states. Ann. Rev. Polit. Sci. 20, 189–208. doi: 10.1146/annurev-polisci-052615-025801

Raile, E., Raile, A., Salmon, C., and Post, L. A. (2014). Defining Public Will. Politics Policy 42, 103–130. doi: 10.1111/polp.12063

Rickard, L. N., Yang, Z. J., and Schuldt, J. P. (2016). Here and now, there and then: how “departure dates” influence climate change engagement. Glob. Environ. Change 38, 97–107. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2016.03.003

Slater, M. D., and Gleason, L. S. (2012). Contributing to theory and knowledge in quantitative communication science. Commun. Methods Meas. 6, 215–236. doi: 10.1080/19312458.2012.732626

Keywords: climate change, social movements, activism, power, organizing

Citation: Han H and Barnett-Loro C (2018) To Support a Stronger Climate Movement, Focus Research on Building Collective Power. Front. Commun. 3:55. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2018.00055

Received: 30 August 2018; Accepted: 23 November 2018;

Published: 19 December 2018.

Edited by:

Neil Stenhouse, University of Wisconsin-Madison, United StatesReviewed by:

Dave Karpf, George Washington University, United StatesAdam Levine, Cornell University, United States

Copyright © 2018 Han and Barnett-Loro. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Hahrie Han, aGFocmllQHVjc2IuZWR1

Hahrie Han

Hahrie Han Carina Barnett-Loro

Carina Barnett-Loro