95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Commun. , 25 July 2016

Sec. Disaster Communications

Volume 1 - 2016 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomm.2016.00004

Disasters create an urgent need for people to deal with novel emergent problems. To respond effectively, people require information (about the event, support resources, actions, etc.) and the ability to interpret and use available information to deal with diverse, emergent hazard consequences and demands over time. This diversity renders top-down, homogeneous approaches to disaster communication ineffective. This paper examines whether a social media-based communication strategy, using Facebook, represents a more effective way of accommodating this diversity (e.g., event impacts, geographical, demographic, social), meeting the information needs of affected populations, and enhancing the quality of disaster communication. Data on how 479 people who used a Facebook page (Tassie Fires – We Can Help) specifically developed to assist response and recovery for the 2011 Tasmanian wildfire/bushfire disaster were obtained using an open-ended questionnaire. The accounts of people’s experience of the event and their engagement with the Facebook page obtained from their responses to the questionnaire were analyzed using thematic analysis. The paper also discusses evidence regarding how the development of functional social relationships among those who engaged via the page enhanced the effectiveness of the disaster communication process. In particular, it discusses how engagement with the page and the way the page was managed by the Administrator facilitated the development of Sense of Community, a social structural characteristic known to influence the quality of disaster communication. The paper concludes with a discussion of the implication of the findings for future research into the relationship between Facebook use, disaster communication, and disaster recovery.

Disasters expose affected citizens and social systems to demands and consequences that fall well outside the usual realm of people’s experience. The complexity and novelty of these demands and consequences requires people, individually and collectively, to develop creative solutions to emergent problems. Disaster communication plays a pivotal role in providing the information people need to respond to these problems. While disaster communication has predominantly been the province of formal response agencies (e.g., emergency services etc.), online emergent groups are increasingly playing active roles in communication and information exchange (Blanchard et al., 2010; Vieweg et al., 2010).

This paper presents a case study of disaster communication using a Facebook page [Tassie Fires – We Can Help (TFWCH)] specifically set up to provide a medium for communication during the response and recovery for a wildfire (bushfire) disaster in Tasmania, Australia in 2013. The study explored people’s interpretation of their experience and how information made available using a Facebook resource influenced the nature and effectiveness of community-based disaster response and recovery. This paper argues that how disaster communication influences the quality of this experience is a function of the interrelationship between information and the social context in which information is received and used. The rationale for taking this position is discussed next.

Disaster communication is a challenging endeavor. In a disaster, people’s encounters with novel and uncertain circumstances means that, if they are to respond, they require timely, consistent, and accurate information that informs how they might meet their needs. Furthermore, the circumstances and the needs people experience, and thus the information and competencies required to meet these needs, vary from place to place, from group to group, and over time (Comfort et al., 2004; Ehnis and Bunker, 2012; Paton et al., 2014). The consequent diversity in circumstances and needs renders a “one-size-fits-all” approach to disaster communication ineffective. However, such an approach remains the mainstay of communication delivered via top-down disaster response strategies. In this context, it is not surprising that a frequently cited reason for people turning to social media for information is dissatisfaction with information provided by traditional media (Sutton et al., 2008; Shklovski et al., 2010). Official response agencies and conventional mass media sources cannot respond effectively to meet the specific, local, and evolving information needs of affected populations (Bruns et al., 2012; Palen et al., 2012). While social media have expedited opportunities for accessing local knowledge (Palen et al., 2012), social media as such may not automatically represent a universal panacea for the challenges faced by disaster communication.

A key issue here is that it is not information per se that determines action, but how people interpret it and render it meaningful in the context of their (unique) needs and expectations (Marris et al., 1998; Lindell and Whitney, 2000; Lion et al., 2002; Rippl, 2002; Norris et al., 2008; Paton, 2008; Lindell et al., 2009; Eiser et al., 2012). This represents effective disaster communication as the product of two things; appropriate information being available in timely ways and the ability of its recipients to interpret and use information to understand and formulate their responses to the novel hazard consequences and circumstances they are confronted with. It, thus, becomes important to understand how people interpret, make sense of, make decisions about how to act when dealing with novel events.

Peoples’ interpretation of high risk events, particularly when faced with uncertain and challenging circumstances, and what they might do to confront the novel and challenging conditions they encounter is influenced by others’ views (Lion et al., 2002), with those perceived to share similar values being especially important (Earle, 2004; Poortinga and Pidgeon, 2004). Hence, when seeking to make sense of and take action to deal with novel and uncertain events, people do so through discussions that arise from engaging with those with similar values, interests, and needs. People are more likely to perceive information from those with similar values and needs as empowering, increasing the likelihood that they will trust the source and use the information provided to make decisions and take action (Eng and Parker, 1994; Earle, 2004; Paton, 2008).

People, however, rarely develop the social interpretive capabilities required to understand novel and challenging events prior to disaster events occurring. Consequently, they have to do so during disaster response and recovery phases (McAllan et al., 2011; Paton et al., 2014). These authors discussed how social interpretive capabilities emerged from regular face-to-face interaction between those similarly affected in disaster response and recovery settings (the 2009 Black Saturday Fires in Australia and the 2011 Christchurch earthquake and aftershock sequence, respectively).

In both the above cases, face-to-face interaction with those sharing a similar fate underpinned the development of a collective and enduring capability to respond to the issues experienced. This paper presents an exploratory investigation into whether social media use in disaster communication can extend beyond information brokerage to include creating the kind of “community” context found to influence peoples’ ability to interpret and use information in disaster recovery settings when people interact face to face. The growing use of social media in disaster response settings makes it important to explore the relationship between social media and the development of effective disaster communication.

To explore this relationship between social media and the development of social interpretive capability, it was necessary to identify a theoretical construct to structure the exploratory research questions used to guide the analysis and interpretation of the data. The theoretical construct was selected from work on social capital and adaptation (e.g., Norris et al., 2008). This paper focuses on one aspect of social capital, Sense of Community (SoC) (Flora, 1998; Portes, 1998; Alesina and La Ferrara, 2000; Putnam, 2000; Forrest and Kearns, 2001; Morrison, 2003). The reason for adopting SoC (McMillan and Chavis, 1986; McMillan, 1996) will now be introduced.

Sense of Community was selected for two reasons. First, it provides a well validated approach to representing the meaning of “community” (McMillan, 1996). SoC encompasses members’ feelings of belonging, the belief that members matter to one another and to the group, and encompasses the existence of a shared faith that members’ needs will be met through their commitment to be together (McMillan and Chavis, 1986). Second, SoC has a history of informing understanding of effective communication in disaster readiness and recovery settings (Paton et al., 2001, 2008, 2014; Carroll et al., 2005; Brenkert-Smith et al., 2006; Keller et al., 2006; Hodgson, 2007; Cottrell et al., 2008; Paton and Tedim, 2013).

Sense of community facilitates both the social construction of risk and how information about managing risk is disseminated and used within social networks (Alesina and La Ferrara, 2000; McGee and Russell, 2003; Morrison, 2003; Hannigan, 2006; Holstein and Miller, 2006; Paton et al., 2008; Frandsen et al., 2012). When SoC is high, members are more likely to be regarded as credible and trusted sources of information (McGee and Russell, 2003). Furthermore, when those with whom SoC is shared have local hazard experience and knowledge, these others become an important resource for developing and implementing locally relevant hazard response activities (Indian, 2008; Frandsen et al., 2012).

Since SoC develops over time via regular interactions in mainstream community life (Dalton et al., 2007), this might be expected to remain its logical source. However, within pre-disaster contexts, SoC is being eroded by, for example, resident turnover and reduced neighborhood interaction (Forrest and Kearns, 2001; Morrison, 2003; Indian, 2008; Prior and Paton, 2008). A consequence of this is a reduction in the availability of a resource (SoC) that assists formulating and enacting local responses when disaster strikes. Consequently, it becomes a resource that needs to be developed within disaster response and recovery settings (Paton et al., 2014). The question posed here is whether SoC can develop and function in virtual social network settings when interaction is mediated through a Facebook page in disaster response and recovery settings.

Support for pursuing this topic derives from the proposition that the sudden experience of a significant, novel experience that affects a large number of people in comparable ways (creates a sense of shared fate) can create a context in which shared unique needs, expectations, and goals emerge (McMillan and Chavis, 1986; Dalton et al., 2007). This paper explores (a) whether shared experience of a disaster setting can trigger the emergence of shared needs and goals and (b) whether this sense of shared fate can, when subsequent interaction occurs via a Facebook page, result in people developing a SoC. It also examines whether another factor identified as crucial for developing an effective collective response within disaster recovery settings, emergent community leadership (McGee and Russell, 2003; Mamula-Seadon et al., 2012; Paton et al., 2014), functions in a similar way when people engage through using a Facebook resource.

In face-to-face settings, the effectiveness of emergent local community leaders is a function of their ability to use their local knowledge, social networks, and management skills to help community members deal with local issues (McGee and Russell, 2003; McAllan et al., 2011). Virtual communities differ from their face-to-face counterparts in an important respect. The “leader” of an online Facebook page may not be local and may have no prior, or only indirect, knowledge of or connection with those affected by a disaster. It, thus, becomes pertinent to ask if the leadership of a social media setting plays a role in the development of a functional community.

The study will explore whether an emergent SoC can be discerned in people’s accounts of their disaster experience and whether there exists evidence to suggest that SoC makes a unique contribution to increasing the quality of disaster communication. From the above discussion, the following research questions emerged:

1. Sense of Community can arise from interactions that emerge in the context of a “provocation” that creates a strong sense of shared fate and common needs (Dalton et al., 2007). In this case, does the shared experience of a wildfire disaster act as a catalyst for the development of a functional community (RQ 1) and, if so,

2. Does a social media (Facebook) communication strategy afford opportunities for timely, relevant, and reciprocal information sharing in ways that facilitate relationship building and collective action (in this case, SoC) in an online emergent community (RQ 2)? and, if this is the case,

3. Does the Administrator (community leader) contribute to developing and maintaining a functional online community (RQ 3)?

It should be noted that while posed separately, these questions are interdependent. For example, people’s experience of the event creates information needs and seeking information to meet these needs via social media increases the likelihood of engaging with others to understand and meet comparable needs in similar circumstances. If engagement is mediated by a Facebook page, the Administrator of that page could influence information access and how people engage with each other. The research questions should, thus, be regarded holistically. How answers to these questions were sought is discussed next.

Many emergency response agencies use social media (both pre-event and during response and recovery) as part of their disaster communication strategy. However, regular usage may confound analysis of data collected during crisis events. For example, in the absence of longitudinal analysis of the social media usage, pre-event beliefs regarding the perceived credibility and trust in a source can make it difficult to systematically assess how a resource affects communication. Post hoc research may be affected by participants having used several (e.g., Facebook pages of several different agencies, Twitter, etc.) social media sources, making it difficult to identify the specific contributions of each. These factors can confound analysis of emergent social groups and how social media use informs their recovery.

This study surmounts these issues by basing data collection and analysis on data linked to a Facebook (TFWCH) page developed specifically as a resource to assist response and recovery for a specific event, the 2013 wildfire in southern Tasmania. The page commenced operation during the fire event. Since the commencement of the page and the onset of the response and recovery coincided, the data discussed here afford opportunities to explore how a social media resource functions as an information and social resource in the context of disaster recovery and to seek answers to the first two research questions posed above.

Answers to the third research question were afforded by the TFWCH page being managed by a single Administrator throughout the several weeks of the wildfire disaster. This made it possible to explore the relationship between the Administrator role and online group functioning in ways that would be impossible with mainstream social media. For example, if people accessed several Facebook pages managed by different Administrators, it would be difficult to isolate the relative contributions of each to any outcomes observed. Collecting data from a page administered by a single person makes it possible to explore emergent leadership in online settings and its role in relationship development.

The study used a retrospective case study design, using the results from online questionnaires administered to all those who had used the TFWCH page after the 2013 wildfire event. The study obtained ethics approval from the University of Tasmania Social Science Ethics Committee (Approval Number: H004624). Participants were invited to participate because they had direct and indirect involvement in this event through their sustained engagement with the TFWCH page.

Semi-structured questions were designed to obtain people’s accounts of their experience of the response and recovery phases of this event, but were phrased in a way that avoided specifically asking about any social structural relationships that could have emerged. This provided a more objective basis for an exploratory analysis of whether SoC can emerge from socially mediated interaction. The data upon which the analysis is based derived from answers to four open-ended questions:

1. Any details/comments/clarification you would like to add? Or is there another way you helped that I haven’t asked you about? I would love to hear more

2. What do you think the TFWCH page did well? What was good about the page?

3. What do you think the TFWCH Facebook page could have done better? How could it be improved?

4. There were other good pages on Facebook about the fires. Did any help you? Which were good? Were any pages “not-so-good”? How were they different to the TFWCH page?

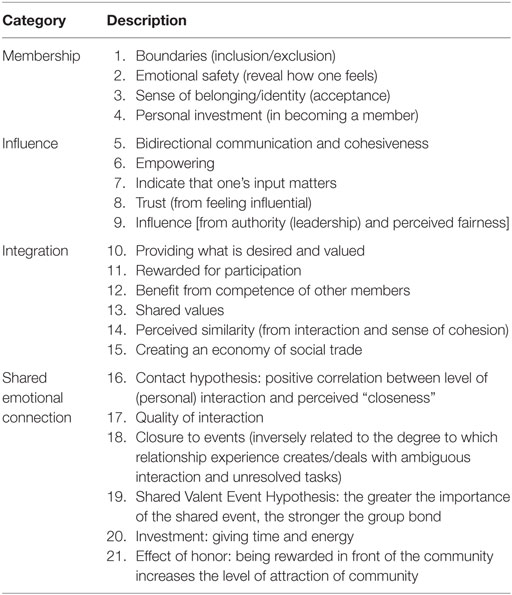

Data were obtained from 479 participants. Comments from the open-ended questionnaires were imported into NVivo (www.qsrinternational.com) from a Windows Excel spreadsheet, generated using the online survey tool Wufoo (Wufoo™ Online Forms). Data analysis was conducted using thematic analysis, and followed the guidelines proposed by Braun and Clarke (2006). This analysis examines the relationship between the quotes provided and SoC. To facilitate this exploratory analysis, an interpretive framework developed from McMillan and Chavis (1986) and McMillan (1996) was used. The categories of SoC are listed in Table 1.

Table 1. Sense of Community categories and descriptors (McMillan and Chavis, 1986; McMillan, 1996).

The presentation of the results is organized around a series of “analysis boxes.” These are not tables per se, but provide a way to illustrate how the elements of people’s accounts of their experience mapped onto the characteristics of SoC. The numbers in the right-hand column correspond to the SoC items listed in Table 1.

As introduced above, SoC can emerge from a “provocation” (i.e., a highly salient issue that collectively impacts many people) that suddenly presents people with a sense of shared fate or set of conditions that they all share (Dalton et al., 2007). It is postulated that a disaster can create a context in which people who may not have had any prior relationship have the potential to experience a sense of affinity with these others as a direct result of the event stimulating the emergence of common needs, goals, and expectations. Answers to RQ1 were sought by exploring whether people’s accounts of their experience of the 2013 wildfire disaster indicate that the event acted as a catalyst for creating a social entity defined by shared involvement in this specific event.

The analysis of the data revealed evidence that people’s interpretation of their experience of the fire could be construed as a salient event (provocation) capable of creating a sense of shared fate among those involved in the fire. Fires were collectively described as “catastrophe,” “traumatic,” “devastating,” and “distressing,” both by those in affected areas, and those experiencing the event vicariously, indicating that the experience was significant and capable of acting as a context in which a sense of shared fate can emerge. A sense of shared fate was further enhanced by feelings of being directly impacted and through having (e.g., family directly involved) or acquiring (e.g., wanting to help) a connection with the people and places affected. These views offer support for RQ 1. Further support was evident in the spontaneous emergence of new relationships; new relationships emerged as a result of people experiencing a sense of affinity with others as a consequence of their shared involvement.

A sense of shared fate does not, however, guarantee that a SoC will develop. Rather, it acts as a catalyst for it to emerge. For functional capacity to evolve, people must be aware of their shared fate and this must motivate people to interact with others to confront shared issues. Because a disaster presents people with circumstances that fall outside their past experience, and because levels of hazard preparedness are low (Paton and McClure, 2013), disasters create a need for people to interact with civic authorities and others they know to acquire the information they need to support their recovery. The transformation of shared fate into “community” was cultivated by the collective need of those involved in the event needing to seek information.

Answers to research question RQ2 requires evidence that the need for information resulted in the TFWCH page becoming a setting in which regular information sharing occurs. Doing so would represent the page providing a setting for this emergence. One factor that motivated this transformation emerged from people’s accounts about the adequacy of the formal response and, thus, why people turned to social media.

A common denominator in people’s experience of the event was their shared and convergent perception of “crucial gaps in official response information,” “problems contacting formal authorities,” “lack of relevance of information from and frustration with authorities,” and “encountering red tape.” People needed information to inform both their understanding of the novel and challenging circumstances in which they found themselves and to guide the action they might take to deal with the local issues encountered. Formal agencies were not seen to be acting as information conduits for either those directly affected or those wanting to help. By not doing so, people’s need to seek information elsewhere provided a secondary catalyst for the emergence of community, and one that could be pursued because the TFWCH page created a context for this to happen.

Thus, the perceived ineffectiveness of formal sources as providers of information created circumstances conducive to drawing people into an embryonic social setting created by the TFWCH page. This page, thus, provided opportunities for people to connect in ways that derived from their shared experience. Furthermore, because it was established specifically to assist recovery for this event, interacting with the TFWCH page brought people who had experienced the same event and who had needs relating to this shared fate or common experience to interact with others to understand what was happening and identify what they could do to respond and do so in meaningful and relevant ways. The page, thus, provided a context in which people could realize their affinity with others and it provided a context in which this sense of affinity (facing a novel threat, needing information) could blossom into a community.

People emphasized the importance of mutual assistance in their experience of their disaster response and recovery; it created a “sense of community spirit and support,” with people willing to help others. People commented that the disaster brought people together and that goodwill was contagious; that “helping breeds helping.” The page, thus, provided a mechanism to realize people’s “in-built desire to help.” By creating a social setting that mobilized active and functional involvement, the TFWCH page created other opportunities for the emergence of the Membership, Influence, and Integration (see Table 1) facets of SoC. The development of SoC in this context was assisted by the page affording opportunities for communication built around the reciprocal exchange of information and resources.

The TFWCH page was identified as a resource whose utility was heightened by it facilitating the distribution and use of information. Key issues here included its capacity to function as a broadcaster (e.g., sharing information that could not be shared with the community in other ways) and amplifier (e.g., re-posting and sharing agency-sourced information to increase its accessibility by a broader audience) of information. These functions contributed to the ability of the page to supply relevant and timely response-related information that might otherwise have been lost to affected populations. Importantly, it facilitated reciprocal communication between those using the page.

By creating a setting that facilitated reciprocal communication, the page acted as a resource whose functioning extended beyond being a provider of information to include it acting as a setting in which narratives between those using the page were created and used. People appreciated that the page enabled them to tell their own stories – the inspiring stories, and the beautiful stories – but the page also told the “bad” stories (e.g., stories that participants had not through, making unnecessary suggestions, keeping re-telling the same story, stories about unnecessary and unneeded donations that clogged the newsfeed.). However, balanced content facilitated inclusivity and sustained people’s sense of trust in the page. This was also reflected in users commenting that the TFWCH page told “the real story.”

The importance of this aspect of people’s experience derives from the fact that the appearance of stories within a social network is an important indicator of the emergence of SoC (McMillan, 1996). Access to community stories both inspired and motivated continued engagement and contributed to the development of enduring relationships built around people’s sense of shared fate and common purpose.

Making people’s stories available resulted in the page being seen as a source of inspiration. Exposure to stories assisted people to see the importance of their involvement and the value of their personal investment. This, in turn, helped sustain people’s belief in being empowered by their engagement with the page and motivated their continued commitment to engage with others through the page. The page, thus, provided continued opportunities for meaningful engagement (e.g., using information that was relevant and timely, appropriate help getting to where and to whom it was needed) through engagement with the page, with this supporting people’s sense of membership, influence, and integration.

The belief that the page was “telling the real story” was also influenced by users acknowledging that information was sourced from people in situ who were “close to the action,” knowledgeable, and up-to-date. Knowing that information circulating through the page was accurate, factual, and usually verified provided users with evidence of some “quality control” over content and “increased trust in the page.”

This sense of being connected to real time events meant that those involved were kept informed as events and people’s needs evolved over time. Together, these elements made progressive contributions to sustaining trust and to enhancing people’s sense of membership and being part of an empowering setting that increased their ability to deal with evolving consequences and demands, and to do so in timely and effective ways. The reciprocal nature of the communication that arose from engagement through the page facilitated people’s active involvement in managing their own recovery or directly assisting people’s ability to do so. This reflects elements of bidirectional communication and cohesiveness that contributed to people feeling they had a continuing role to play (Influence and Integration). Bidirectional (reciprocal) communication and cohesion also helped maintain trust in the page as a source of information.

Trust in the page contributed to it enhancing both the perceived quality and relevance of information and, thus, its utility to inform decision making and people’s ability to take action with confidence. This is very important in disaster communication contexts where uncertainty and ambiguity can otherwise hamper action (Paton, 2008).

The themes of trust, empowerment, and the enduring sense that people’s input was valued and used also emerged from statements identifying how the Administrator (see below for discussion of this role) both encouraged people’s involvement and identified potential ways in which they could help. This had secondary benefits in terms of sustaining people’s sense of involvement (belonging) with others over time.

The capacity of the page to provide near-instantaneous connections between those requiring or requesting help and those best equipped to meet these needs sustained a sense of meaningful engagement and contributed to people’s sense of being empowered. This, in turn, reinforced people’s sense of their operating in an economy of social trade (e.g., exchanging information, putting those with needs in touch with those capable of meeting those needs) over time. This facilitated people’s appreciation that they were operating collectively, rather than individually, and that by doing so, they were making a difference; the response required the whole “community” to work together. People appreciated that everyone was coming together to the “one place” (the page) and “working together through a single source” to define and resolve the issues encountered. This resulted in people describing their experience of the page in ways that encompassed feelings of membership, influence, and integration.

An important consequence of this emergent collective capability (the “synergies”) was its role in increasing the scope of people’s activities. People became more proactive as a consequence of having access to more diverse knowledge and experience; the whole became more than the sum of its parts. This is comparable to another characteristic found in functional communities, collective efficacy, or collective intelligence (Vieweg et al., 2008; Paton and McClure, 2013). It emerged here through the sense of mutual influence and integration. The proactive element is inferred based on work that identified how collective efficacy predicts people’s collective ability to cope with emergent demands that derives from sustained meaningful collaboration on issues of common interest or concern (Paton and McClure, 2013). This emergent collective capability manifests itself in other interesting ways.

Some respondents noted that if they saw things on the page that were relevant to people they knew they would then make that information available to those others. This is akin to the concept of implicit communication (Pollock et al., 2003). Implicit communication is a crisis management capability not normally seen or studied outside the networks found in professional crisis management groups. This concept describes the proactive provision of information without (potential) recipients asking for it and, in so doing, facilitates network members’ ability to respond more effectively to emergent issues.

This can only occur if people engage with their social network in ways that include the development of deeper level relationships. These deeper level relationships encompass not only knowledge of the needs of a broad range of people but also feeling sufficiently connected to them in reciprocal and caring ways that result in people anticipating (and wanting to anticipate) others’ needs and proactively helping them meet their needs. This provides evidence of how engagement with the page could lead to a higher sense of membership and integration. This function added to the quality of the bidirectional cohesiveness that emerged from using the page and to its ability to maintain an empowering setting in which mutual influence took on a proactive character and optimized the quality of the social trade occurring through the page. This sense of meaningful engagement was further supported by the way the page provided feedback and recognition to those involved.

The quality and functionality of relationships forged through engaging via TFWCH was supported by the page acknowledging people’s contributions and publically thanking them for actions that would have otherwise gone unacknowledged. Respondents commented that they “felt heard.” The page, thus, afforded opportunities to ensure that people knew that their contribution was making a difference and that their help was publically appreciated, with this contributing to people’s sense of membership, influence, and integration (Table 1) through the development of emergent, enduring relationships.

The reciprocal and anticipatory social exchange discussed above reflects the development of emergent relationships (“strangers assisting strangers,” and “strangers collaborating together”) and the creation of a context in which people could work together toward achieving common goals.

Several respondents commented on how friendships forged through their engagement with the TFWCH page fostered their developing a “sense of community spirit.” The emergence of (relatively) enduring relationships was supported by the page affording opportunities for reciprocal information flows in a context of mutual influence. This reinforced people’s sense of Membership and Integration with this emergent community. At the same time, the Influence and Shared Emotional Connection (Table 1) that arose within this emergent community played a role in the page contributing to stress management and people’s psychological well-being.

By providing a medium for sharing experiences and emotions and obtaining help, engagement through the page had additional implications for stress management. People said the TFWCH was a source of emotional support because they had an outlet to voice their experiences, concerns, opinions, thanks, love, sympathy, and praise. The emotional connectivity that emerged from engagement through the page created a context in which people could appreciate that the emotions they were experiencing were not unique to them, that similar feelings were being experienced by many others, and that these feelings were normal for people confronting abnormal circumstances.

The fact that the page acted as a medium through which people could benefit from the competences and resources of others and that they could access information in a timely way about issues they were facing contributed to stress management by increasing people’s sense of perceived control. Some respondents said that they believed the affected communities had gained much comfort from being involved in such a collaborative effort as members of a supportive community. People believed that the page gave physical, informational, and emotional social support to those impacted by the event.

Some respondents described the page as absolutely vital to their psychological well-being while isolated by the fire, road closures, and loss of infrastructure. Others described how their sense of well-being was augmented by the page allowing them to feel useful even though they were stuck on “the outside,” while people they cared about were stuck on “the inside” experiencing the consequences of the wildfire. People who were helping said there was solidarity in knowing that they were not alone in feeling a need to help.

Some respondents commented on how being able to actually do something was cathartic. Respondents described how the level of support was incredible; that it was “truly heart-warming and humbling” seeing so many people “stepping up” to help. Respondents reported how being involved with the page in ways in which they and others made a difference gave them a restored faith in humanity and added to the quality of the shared emotional connectedness prevailing within this emergent community.

The preceding discussion provided support for the proposal that engagement and social exchange mediated through the TFWCH page facilitated the development of the properties of membership, influence, integration, and shared emotional connection (SoC) that warrant it being regarded as a functional, emergent community in ways comparable to what has been observed in face-to-face interactions (e.g., McAllan et al., 2011; Paton et al., 2014). These latter authors, however, identified another factor pivotal to ensuring that SoC is developed, maintained, and used in disaster response and recovery settings; emergent leadership. The fact that the TFWCH page was managed throughout by a single person made it possible to explore the role online leadership played in creating and sustaining SoC. The evidence supporting this is discussed next.

A theme that emerged described how the agency and power held by the Administrator (the social media term for leader) and her capacity to forge functional relationships with the authorities contributed to the perceived credibility of the page. Credibility and trust are important predictors of people’s involvement with a source of information, especially under the kinds of uncertain conditions that prevail in disaster response and recovery settings (McGee and Russell, 2003; McAllan et al., 2011; Mamula-Seadon et al., 2012; Paton et al., 2014). The Administrator’s role in translating and deciphering information for diverse audiences was important in this context, as was the belief that the Administrator ensured that the page was characterized by a climate of positivity and optimism in ways that made additional contributions to people’s sense of membership, integration, and shared emotional connections.

Several leadership qualities (described in terms such as “delegation,” “intelligent handling of sensitive issues,” “being knowledgeable and capable,” “having good organizational and communication skills,” and “being humble and genuine”) were identified by respondents as enhancing their perception of the quality of the page. These traits translated into the Administrator being seen as “trustworthy” and as providing leadership that facilitated creating a community of action. Hence, support exists for the Administrator playing a role in establishing and maintaining a SoC in emergent online communities.

Sense of community is one facet of a functional community that influences how people deal with uncertain, novel, and challenging events. Factors such as resident turnover are diluting the availability of SoC. This makes it important to include developing this social resource within disaster risk reduction strategies. However, given evidence (McAllan et al., 2011; Paton et al., 2014) that people may have to develop this resource in disaster response settings makes it important to understand how resources, such as SoC develop in disaster response settings and to use this knowledge to inform ways to expedite the development and use of social response capability in order to hasten the recovery process. This study explored how social media-based (Facebook) strategies function in this regard.

The 2013 Tasmanian wildfire event contained at least two “provocations” (Dalton et al., 2007) that acted as catalysts for the emergence of a SoC in this case study. One was the event itself. Another was dissatisfaction with the ability of formal communication processes to meet the diverse needs of those affected and those who volunteered to assist. The response to this dissatisfaction reiterates earlier findings (Sutton et al., 2008; Shklovski et al., 2010; Bruns et al., 2012; Palen et al., 2012). This dissatisfaction made people receptive to the opportunities afforded by social media (Facebook page) to access information. The analysis, thus, furnished support for RQ1 and RQ2.

A shared event and a need for information provided conditions conducive to the emergence of community. The transformation into a functional community derived from how the TFWCH facilitated reciprocal communication. Opportunities for reciprocal communication allowed people to engage with others through the page in meaningful ways with people with similar needs, goals, and expectations. The page, thus, created a social setting in which structured interaction with others with similar needs and goals culminated in the emergence of a social setting that possessed the qualities of membership, influence, integration, and shared emotional connections (see Table 1). The emergence of these qualities allowed the setting to be characterized as it having a SoC. This provides support for RQ1 and RQ2. An event that affected a large number of people directly and indirectly and that created a collective need for people to seek information and ways to offer help to deal with complex, evolving problems can act as a catalyst for the emergence of community and SoC.

While the analyses provided support for the emergence of SoC, this cannot be taken to automatically imply that SoC played a role in the communication process. That is, it cannot be implied that SoC mediates the relationship between information communicated and effective community outcomes. There is, however, evidence to suggest that this may be the case.

One line of evidence supporting SoC playing a mediating role in disaster communication comes from people’s accounts that the sense of membership, integration, and influence (via reciprocal communication) enabled through engaging with others via the page, underpinned the development of a proactive, collaborative approach to using information to achieve shared, meaningful outcomes. Through the page, the whole became greater than the sum of its parts and increased the assortment of resources available to people and, consequently, the range of issues people were able to deal with. Individual capabilities and knowledge did not change, but what they could accomplish did as they had access to both more information and input on how that information could be used.

Another line of evidence for SoC playing a mediating role in the communication process emerged from people’s accounts of their emergent sense of integration and shared emotional connection facilitating proactive (implicit communication) communication. People were sufficiently engaged with others to understand and anticipate others’ needs. Linked to this was the emergence of trust in the page and its users as a component of people’s emergent SoC. Because trust has been identified as a crucial predictor of people’s ability to use information under conditions of uncertainty (Paton, 2008), this adds weight to the argument that SoC played a role in the communication process. The reciprocal relationships facilitated the emergence of relationships bound together by stories circulating through the page.

Storytelling and sharing is pivotal to creating an enduring SoC and facilitating adaptation (McMillan, 1996; Norris et al., 2008). Another line of evidence can be discerned in the emergence of storytelling through the medium of the page. This supports the conclusion that page afforded opportunities for the development of SoC. But more than that, the fact that stories emerged to sustain awareness of successes achieved and that shared stories provided sources of inspiration and motivation provide some support for SoC playing a mediating role in disaster communication. Taken together, these examples warrant future work being undertaken to systematically explore how SoC develops and contributes to effective communication.

With regard to RQ3, as with their face-to-face counterparts (McAllan et al., 2011; Paton et al., 2014), an online community leader (the Administrator) contributed to the development and maintenance of a social setting that facilitated people’s ability to feel a sense of inclusive, integrated membership, in a setting where the management of information flow contributed to ensuring that members remained influential. Thus, the analysis provides some qualified support for the view that an emergent SoC enabled community members to use their initiative, knowledge, and connections to collaborate and engage in community action in ways that allowed people to proactively engage in their own recovery.

This study is exploratory. Its findings and conclusions remain tentative until further work is undertaken. One issue derives from the fact that, as is true of all community research, there is no way of knowing what those who decided not to complete the questionnaire thought. It can, however, be assumed that the responses of those who did offer their insights were doing so about how social media (Facebook) helped people respond in disaster contexts. It is also important to acknowledge that the participants were a social-media using cohort. No attempt was made to contact people in any way other than social media. Future work could also seek to replicate this study across, for example, urban and rural populations and different hazard events and to include the study of Facebook pages established and operated by the authorities and those set up and run by communities themselves. While affording an opportunity to examine the leader role, this also meant it was not possible to separate out the respective contributions of group processes and leader processes. Future work could include conducting a similar analysis with leaderless groups.

Sense of community was used here because of it having a history of being linked to effective disaster communication. Future work should examine other theoretical frameworks. This could include frameworks examining how communication is embedded in social context (e.g., Lindell et al., 2009), those exploring how information and social structures interact (e.g., Norris et al., 2008), and others examining how SoC interacts with community and agency characteristics (e.g., Paton et al., 2008; Paton and Tedim, 2013).

In conclusion, the findings presented here support the view that when established and managed specifically to support disaster response and recovery, social media-based (Facebook) strategies can facilitate effective disaster communication. Facebook strategies can assist with ensuring that disaster-affected populations receive timely, consistent, and accurate information. The analysis supports the view that a Facebook-based strategy can function to enable and sustain the development of social resources, such as SoC, that help affected populations develop and apply collaborative disaster response strategies. Furthermore, Facebook-based disaster communication strategies can do so irrespective of where members are located or how the demands and needs experienced change over time.

With regard to authorship, the following criteria were satisfied by both authors: substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; or the (DP, MI) acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work; and drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content; (DP, MI), and final approval of the version to be published; (DP, MI), and agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that (DP, MI), questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Alesina, A., and La Ferrara, E. (2000). Participation in heterogeneous communities. Q. J. Econ. 115, 847–904. doi: 10.1162/003355300554935

Blanchard, H., Carvin, A., Whittaker, M. E., Fitzgerald, M., Harman, W., and Humphrey, B. (2010). White paper: the case for integrating crisis response with social media. American Red Cross. Available at: http://www.scribd.com/doc/35737608/White-Paper-The-Case-for-Integrating-Crisis-Response-With-Social-Media

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Brenkert-Smith, H., Champ, P. A., and Flores, N. (2006). Insights into wildfire mitigation decisions among wildland-urban interface residents. Soc. Nat. Resour. 19, 759–768. doi:10.1080/08941920600801207

Bruns, A., Burgess, J., Crawford, K., and Shaw, F. (2012). #qldfloods and @QPSMedia: crisis communication on Twitter in the 2011 South East Queensland floods. ARC Centre of Excellence for Creative Industries and Innovation. Available at: http://cci.edu.au/floodsreport.pdf

Carroll, M. S., Cohn, P. J., Seesholtz, D. N., and Higgins, L. L. (2005). Fire as a galvanising and fragmenting influence on communities: the case of the Rodeo-Chediski Fire. Soc. Nat. Resour. 18, 301–320. doi:10.1080/08941920590915224

Comfort, L. K., Ko, K., and Zagorecki, A. (2004). Coordination in rapidly evolving disaster response systems: the role of information. Am. Behav. Sci. 48, 295–313. doi:10.1177/0002764204268987

Cottrell, A., Bushnell, S., Spillman, M., Newton, J., Lowe, D., and Balcombe, L. (2008). “Community perceptions of bushfire risk,” in Community Bushfire Safety, eds J. Handmer and K. Haynes (Melbourne: CSIRO Publishing), 205–225.

Dalton, J. H., Elias, M. J., and Wandersman, A. (2007). Community Psychology: Linking Individuals and Communities, 2nd Edn. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Earle, T. C. (2004). Thinking aloud about trust: a protocol analysis of trust in risk management. Risk. Anal. 24, 169–183. doi:10.1111/j.0272-4332.2004.00420.x

Ehnis, C., and Bunker, D. (2012). Social media in disaster response: Queensland polices service – public engagement during the 2011 floods. Paper Presented at the 23rd Australasian Conference on Information Systems, Geelong, Australia. Available at: https://dro.deakin.edu.au/eserv/DU:30049056/ehnis-socialmedia-2012.pdf

Eiser, J. R., Bostrom, A., Burton, I., Johnston, D. M., McClure, J., Paton, D., et al. (2012). Risk interpretation and action: a conceptual framework for responses to natural hazards. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 1, 5–16. doi:10.1016/j.ijdrr.2012.05.002

Eng, E., and Parker, E. (1994). Measuring community competence in the Mississippi Delta: the interface between program evaluation and empowerment. Health. Educ. Q. 21, 199–220. doi:10.1177/109019819402100206

Flora, J. L. (1998). Social capital and communities of place. Rural Sociol. 63, 481–506. doi:10.1111/j.1549-0831.1998.tb00689.x

Forrest, R., and Kearns, A. (2001). Social cohesion, social capital and the neighbourhood. Urban Stud. 38, 2125–2143. doi:10.1080/00420980120087081

Frandsen, M., Paton, D., Sakariassen, K., and Killalea, D. (2012). “Nurturing community wildfire preparedness from the ground up: evaluating a community engagement initiative,” in Wildfire and Community: Facilitating Preparedness and Resilience, eds D. Paton and F. Tedim (Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas), 260–280.

Hannigan, A. J. (2006). Environmental Sociology: A Social Constructionist Perspective, 2nd Edn. London: Routledge.

Hodgson, R. W. (2007). Emotions and sense making in disturbance: community adaptation to dangerous environments. Hum. Ecol. Rev. 14, 233–242.

Holstein, J. A., and Miller, G. (2006). Reconsidering Social Constructionism: Debates in Social Problem Theory. New York: Aldine Transaction.

Indian, J. (2008). “The concept of local knowledge in rural Australian fire management,” in Community Bushfire Safety, eds J. Handmer and K. Haynes (Melbourne: CSIRO Publishing), 205–225.

Keller, C., Siegrist, M., and Gutscher, H. (2006). The role of the affect and availability heuristics in risk communication. Risk Anal. 26, 631–639. doi:10.1111/j.1539-6924.2006.00773.x

Lindell, M. K., Arlikatti, S., and Prater, C. S. (2009). Why do people do what they do to protect against earthquake risk: perception of hazard adjustment attributes. Risk Anal. 29, 1072–1088. doi:10.1111/j.1539-6924.2009.01243.x

Lindell, M. K., and Whitney, D. J. (2000). Correlates of household seismic hazard adjustment adoption. Risk Anal. 20, 13–25. doi:10.1111/0272-4332.00002

Lion, R., Meertens, R. M., and Bot, I. (2002). Priorities in information desire about unknown risks. Risk Anal. 22, 765–776. doi:10.1111/0272-4332.00067

Mamula-Seadon, L., Selway, K., and Paton, D. (2012). Exploring resilience: learning from Christchurch communities. Tephra 23, 5–7.

Marris, C., Langford, I. H., and O’Riodan, T. (1998). A quantitative test of the cultural theory of risk perception: comparisons with the psychometric paradigm. Risk Anal. 18, 635–647. doi:10.1111/j.1539-6924.1998.tb00376.x

McAllan, C., McAllan, V., McEntee, K., Gale, W., Taylor, D., and Wood, J. (2011). Lessons Learned by Community Recovery Committees of the 2009 Victorian Bushfires. Melbourne, VIC: Cube Management Solutions.

McGee, T. K., and Russell, S. (2003). “It’s just a natural way of life.” an investigation of wildfire preparedness in rural Australia. Environ. Hazards 5, 1–12. doi:10.1016/j.hazards.2003.04.001

McMillan, D. W. (1996). Sense of community. J. Community Psychol. 24, 315–325. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1520-6629(199610)24:4<315::AID-JCOP2>3.0.CO;2-T

McMillan, D. W., and Chavis, D. M. (1986). Sense of community: a definition and theory. Am. J. Community Psychol. 14, 6–23. doi:10.1002/1520-6629(198601)14:1<6::AID-JCOP2290140103>3.0.CO;2-I

Morrison, N. (2003). Neighbourhoods and social cohesion: experiences from Europe. Int. Plan. Stud. 8, 115–138. doi:10.1080/13563470305154

Norris, F. H., Stevens, S. P., Pfefferbaum, B., Wyche, K. F., and Pfefferbaum, R. L. (2008). Community resilience as a metaphor, theory, set of capacities, and strategy for disaster readiness. Am. J. Community Psychol. 41, 127–150. doi:10.1007/s10464-007-9156-6

Palen, L., Anderson, K. M., Mark, G., Martin, J., Sicker, D., Palmer, M., et al. (2012). “A vision for technology-mediated support for public participation & assistance in mass emergencies & disasters,” in Proceedings of ACM-BCS Visions of Computer Science. Available at: https://www.cs.colorado.edu/~palen/computingvisionspaper.pdf

Paton, D. (2008). Risk communication and natural hazard mitigation: how trust influences its effectiveness. Int. J. Glob. Environ. Issues 8, 2–16. doi:10.1504/IJGENVI.2008.017256

Paton, D., Buergelt, P. T., and Prior, T. (2008). Living with bushfire risk: social and environmental influences on preparedness. Aust. J. Emerg. Manag. 23, 41–48.

Paton, D., Johnston, D., Mamula-Seadon, L., and Kenney, C. M. (2014). “Recovery and development: perspectives from New Zealand and Australia,” in Disaster & Development: Examining Global Issues and Cases, eds N. Kapucu and K. T. Liou (New York, NY: Springer), 255–272.

Paton, D., and McClure, J. (2013). Preparing for Disaster: Building Household and Community Capacity. Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas.

Paton, D., Millar, M., and Johnston, D. (2001). Community resilience to volcanic hazard consequences. Nat. Hazards 24, 157–169. doi:10.1023/A:1011882106373

Paton, D., and Tedim, F. (2013). Enhancing forest fires preparedness in Portugal: integrating community engagement and risk management. Planet@Risk 1, 44–52.

Pollock, C., Paton, D., Smith, L., and Violanti, J. (2003). “Training for resilience,” in Promoting Capabilities to Manage posttraumatic Stress: Perspectives on Resilience, eds D. Paton, J. Violanti and L. Smith (Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas), 74–88.

Poortinga, W., and Pidgeon, N. F. (2004). Trust, the asymmetry principle, and the role of prior beliefs. Risk. Anal. 24, 1475–1486. doi:10.1111/j.0272-4332.2004.00543.x

Portes, A. (1998). Social capital: its origins and applications in modern sociology. Ann. Rev. Sociol. 24, 1–24. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.24.1.1

Prior, T., and Paton, D. (2008). Understanding the context: the value of community engagement in bushfire risk communication and education. Observations following the East Coast Tasmania bushfires of December 2006. Australas. J. Disaster Trauma Stud. 2008-2. Available at: http://www.massey.ac.nz/~trauma/issues/2008-2/prior.htm

Putnam, R. (2000). Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York: Simon & Schuster Paperbacks.

Rippl, S. (2002). Cultural theory and risk perception: a proposal for better measurement. J. Risk. Res. 5, 147–165. doi:10.1080/13669870110042598

Shklovski, I., Burke, M., Kiesler, S., and Kraut, R. (2010). Technology adoption and use in the aftermath of hurricane Katrina in New Orleans. Am. Behav. Sci. 53, 1228–1246. doi:10.1177/0002764209356252

Sutton, J., Palen, L., and Shklovski, I. (2008). “Backchannels on the front lines: emergent uses of social media in the 2007 southern California wildfires,” in Proceedings of the 2008 Information Systems for Crisis Response and Management Conference (ISCRAM) Conference. Available at: https://www.cs.colorado.edu/~palen/Papers/iscram08/BackchannelsISCRAM08.pdf

Vieweg, S., Hughes, A. L., Starbird, K., and Palen, L. (2010). “Microblogging during two natural hazards events: what twitter may contribute to situational awareness,” in Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. Available at: http://www.pensivepuffin.com/dwmcphd/syllabi/insc547_wi13/papers/microblog/vieweg.et.al.TwitterAwareness.CHI10.pdf

Vieweg, S., Palen, L., Liu, S. B., Hughes, A. L., and Sutton, J. (2008). “Collective intelligence in disaster: an examination of the phenomenon in the aftermath of the 2007 Virginia Tech shootings,” in Proceedings of the 5th International ISCRAM Conference. Available at: http://amandaleehughes.com/CollectiveIntelligenceISCRAM08.pdf

Keywords: social media, sense of community, leadership, online community, disaster communication, disaster response

Citation: Paton D and Irons M (2016) Communication, Sense of Community, and Disaster Recovery: A Facebook Case Study. Front. Commun. 1:4. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2016.00004

Received: 05 May 2016; Accepted: 05 July 2016;

Published: 25 July 2016

Edited by:

Natalie Danielle Baker, Virginia Commonwealth University, USAReviewed by:

Tonya T. Neaves, George Mason University, USACopyright: © 2016 Paton and Irons. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Douglas Paton, ZG91Z2xhcy5wYXRvbkBjZHUuZWR1LmF1

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.