- 1Faculty of Graduate Studies, Dalhousie University, Halifax, NS, Canada

- 2Faculty of Science, School for Resource and Environmental Studies, Dalhousie University, Halifax, NS, Canada

- 3Environmental Sustainability Research Centre, Brock University, St. Catharines, ON, Canada

- 4Department of Sociology and Social Anthropology, Dalhousie University, Halifax, NS, Canada

- 5Department of Social Sciences, Faculty of Arts, University of New Brunswick, St. John, NB, Canada

Climate change will affect many global landscapes in the future, requiring millions of people to move away from areas at risk from flooding, erosion, drought and extreme temperatures. The term managed retreat is increasingly used in the Global North to refer to the movement of people and infrastructure away from climate risks. Managed retreat, however, has proven to be one of the most difficult climate adaptation options to undertake because of the complex economic, social-cultural and psychological factors that shape individual and community responses to the relocation process. Among these factors, place attachment is expected to shape the possibilities for managed retreat because relocation disrupts the bonds and identities that individuals and communities have invested in place. Research at the intersection of place attachment and managed retreat is limited, partially because these are complicated constructs, each with confusing terminologies. By viewing the concept of managed retreat as a form of mobility-based climate adaptation, this paper attempts to gain insights from other mobility-related fields. We find that place attachment and mobility research has contributed to the development of a more complex and dynamic view of place attachment: such research has explored the role of place attachment as either constraining or prompting decisions to relocate, and started to explore how the place attachment process responds to disruptions and influences recovery from relocation. Beyond informing managed retreat scholars and practitioners, this research synthesis identifies several areas that need more attention. These needs include more qualitative research to better understand the dualistic role of place attachments in decisions to relocate, more longitudinal research about relocation experiences to fully comprehend the place attachment process during and after relocation, and increased exploration of whether place attachments can help provide stability and continuity during relocation.

1 Introduction

In 2010 at COP16 (Conference of the Parties), the International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) recognized that one of the effects of climate change would be the increased mobility of people (UNFCCC, 2010). It has been estimated that disasters triggered about 24 million new internal displacements in 2023, most of which were due to storms and floods (IDMC, 2024). These numbers are expected to increase according to researchers working to predict displacement patterns and trends (de Sherbinin et al., 2019; Rossi et al., 2024). For example, under low emissions scenarios 190 million people are predicted to be living below the high tide line by 2100 (Kulp and Strauss, 2019). Accordingly, moving people away from places at high-risk of becoming uninhabitable due to the effects of climate change (high-risk places) is no longer seen as a last resort but as a smart and necessary form of risk management that will reduce residents’ hazard vulnerability and emergency response costs, while promoting restoration of land and ecosystem function (Hino et al., 2017; Siders, 2019). As well, moving people can avoid the high costs of structural protection measures that will increase with more severe and frequent climate change impacts (Doberstein et al., 2020). This “strategic relocation of people, assets and activities to avoid and reduce natural hazard risks and to adapt to impacts of climate change” (Hanna et al., 2019, p. 2) is known, in research and policy, as managed retreat.

Managed retreat is one of the most difficult climate-induced adaptation options to undertake because there is a complex nexus of economic, social-cultural and psychological factors that together shape individual and community responses to the relocation process (Esteban et al., 2020; Hanna et al., 2019; Hino et al., 2017; Steimanis et al., 2021; Thistlethwaite et al., 2018). Even the language of retreat, with its military connotations, can be interpreted as defeatist and intimidating (Koslov, 2016). If managed retreat is to be successfully implemented at the scale that is required due to increasing sea level rise, flooding, drought, and wildfires, then more understanding about the psycho-social dimensions of managed retreat is required (Agyeman et al., 2009; Brunacini, 2023; Fresque-Baxter and Armitage, 2012; Pucker et al., 2023; Raymond, 2013).

Understanding more about the psycho-social aspects of disruptions to place or because of relocation, such as place attachment, is highlighted as a future priority in the emerging research area of climate mobility (Dandy et al., 2019; Seeteram et al., 2023; Simpson et al., 2024). Place attachment merits exploration because relocation will disrupt the bonds and the identities of individuals and communities that are grounded in place (Brunacini, 2023; Devine-Wright, 2014; Relph, 2008; Simpson et al., 2024). Ruptures to people-place bonds create physical and emotional losses that can cause grief (Kothari, 2020) and threaten mental health and well-being (Solecki and Friedman, 2021). Research at the intersection of place attachment and managed retreat is in its infancy, but there are increasing calls to understand how place attachment may inform human responses to retreat (Agyeman et al., 2009; Devine-Wright and Quinn, 2020; Low and Altman, 1992; O’Donnell, 2022; Quinn et al., 2015). There are several potential connections between the two concepts that can be further explored including how place attachments can change over the course of managed retreat; how managed retreat can affect place attachment and vice versa; and how place attachment can impede managed retreat or help in recovery. Increased understanding of these processes has the potential to inform policy and planning initiatives that will ease transitions and limit the negative impact to individual and community well-being (Agyeman et al., 2009; Binder et al., 2019; Cox and Perry, 2011; Fresque-Baxter and Armitage, 2012; Jamali and Nejat, 2016).

The contribution of this paper is to articulate and synthesize the research at the intersection of place attachment and managed retreat. Since research that connects place attachment and managed retreat is limited, in order to obtain useful insights, we take a broader view of managed retreat as a climate-induced mobility, as it requires the movement of people and infrastructure. This has motivated us to conduct a targeted review that incorporates neighboring scholarly fields. For example, the fields of personal mobility, migration and displacement, and forced relocation and resettlement have all incorporated place attachment research and offer insight into the dynamism of place attachments, the role of place attachment in the decision to relocate, and the role of place attachments in recovery. Improved understanding of place attachment and how it may inform human responses to retreat in general will be helpful at both the theoretical and practical levels (Agyeman et al., 2009; Devine-Wright and Quinn, 2020; Low and Altman, 1992; Quinn et al., 2015).

2 Background

The literatures of managed retreat and place attachment show us that both concepts are incompletely conceptualized. Both fields suffer from multiple constructs that are often used interchangeably, and from a wide variety of related research fields which produce an abundant amount of literature about various philosophies, approaches and methods. These issues have been identified in the literature by many researchers and can result in difficulty compiling an accurate body of knowledge that reflects the current state of our understanding (Bukvic, 2015; Nelson et al., 2020).

2.1 Managed retreat

Many terms are used interchangeably in the literature to describe the movement of individual people and communities (Bukvic, 2015). Terms vary in whether they describe movements that are fast or slow, forced or voluntary, planned or unplanned, state-led (managed) or self-governed. For example, the term evacuation describes an abrupt and temporary movement, whereas abandonment may take more time to reconcile but is more permanent. Migration, abandonment, and displacement are seen as primarily un-planned and self-driven, but only displacement is seen as being forced (Burkett et al., 2017; Paul et al., 2024). Likewise, relocation, retreat, and resettlement also tend to refer to forced relocation, but also imply state-led, planned, and the more permanent movement of people (Ajibade et al., 2022; Burkett et al., 2017; Ferris, 2015; Imura and Shaw, 2009; Marter-Kenyon, 2020). Relocation and retreat are also more likely to include the relocation of assets and activities along with people.

Within the climate-induced adaptation literature there are also multiple terms used specifically to describe climate-induced, or climate-related relocation (CRR). For example, in the Global South, the term planned resettlement is most often used, in the United Kingdom and Europe the term managed realignment is often used, and in the United States, Canada and Europe, the terms planned, strategic or managed retreat are used (Doberstein et al., 2020; Hanna et al., 2019; Rupp-Armstrong and Nicholls, 2007). This does not mean you cannot also find references to planned or forced relocation, or resettlement in the CRR literature. Furthermore, newer terms like climigration (climate + migration) are entering the lexicon (Ajibade et al., 2020). Unfortunately, many of these terms have been used interchangeably over the years which is problematic for gathering an accurate state of knowledge in the field. For example, although much of CRR research occurs in the Global South (Ajibade et al., 2022; Marter-Kenyon, 2020), searching for the terms planned or managed retreat will deliver more cases from the Global North (Marter-Kenyon, 2020). Many authors call for more standardized terminology in order to provide consistency in the literature, especially as interest in dialog about climate-related relocation continues to increase (Bukvic, 2015; Paul et al., 2024). New terms like transformative adaptation have been proposed to provide one, all-encompassing term, that invokes fewer negative connotations, and focuses on the positive aspects of relocation (Dundon and Abkowitz, 2021; O’Donnell, 2022). The debate continues about which term to use and when. In this paper we focus on the term managed retreat to represent the forced relocation of individuals, communities and infrastructure due to climate risks, because the term has been widely adopted in academia and policy spheres at this time. This decision however, does affect our search results. Given the linguistic bias discussed above, the focus of this paper is on the movement of people and assets in the Global North.

The construct of managed retreat builds on a long history of both involuntary and voluntary human movement from forced residential relocation as a result of urban expansion and renewal, large infrastructure projects, establishment of protected areas, unsustainable land use patterns that expose people to risks, and man-made and natural disasters (Doberstein and Stager, 2013; Hanna et al., 2019; Marter-Kenyon, 2020; Piggott-McKellar et al., 2020; Wilmsen and Webber, 2015). Some of the earliest managed retreat cases were due to riverine and coastal flooding in the United States and Europe (Koslov, 2016; Pinter, 2021; Pinter and Rees, 2021; Siders, 2019; Tubridy et al., 2021). More recently however, managed retreat has differentiated itself from other types of forced relocation as primarily being driven by climate change hazards. There continues to be managed retreat literature as a result of riverine and coastal flooding (Abel et al., 2011; Dundon et al., 2023; Mayr et al., 2020; Okada et al., 2014; Rupp-Armstrong and Nicholls, 2007), but now, there are also documented responses to extreme weather-related events and sea level rise. For example, there has been much written about relocation after Hurricanes Katrina and Sandy in the United States (Binder et al., 2019; Braamskamp and Penning-Rowsell, 2018; Koslov, 2016; Pinter et al., 2019), and about retreat from low-lying coastal communities (Marter-Kenyon, 2020; Pinter, 2021; Simms et al., 2021). Some of the most well-known cases of managed retreat include the relocation of the island Pacific communities of Kiribati and Fiji, and Indigenous coastal communities in Alaska and the southern United States (Pinter, 2021). Climate change caused wildfires, extreme heat, and permafrost melting are emerging reasons where managed retreat may also be considered necessary (Dundon et al., 2023; Siders, 2019).

Managed retreat may need to occur quickly, such as after a disaster, or may happen more slowly, such as in the case of gradual sea level rise. It is typically a planned, coordinated, and mostly an involuntary process that is overseen by the state through regulations and financial incentives. Depending on the circumstances surrounding the managed retreat, a variety of positive and negative consequences can occur (Simpson et al., 2024). In the best-case scenarios, managed retreat can protect lives, reduce costs related to staying in place, reduce stresses and uncertainty associated with living in high-risk areas, free up land for ecosystems (Ajibade and Siders, 2021; Hanna et al., 2019; Koslov, 2016; Siders, 2019), change historical marginalization (Simpson et al., 2024), and potentially present other life opportunities (Jamali and Nejat, 2016; Siders, 2019). In the worst cases, managed retreat can disconnect people from their communities, culture and livelihoods, exacerbate social inequalities and increase socioeconomic vulnerabilities (Ajibade and Siders, 2021; Koslov, 2016; Simpson et al., 2024), negatively impact mental health and well-being, and disrupt place attachments (Ajibade and Siders, 2021). These positive and negative outcomes may occur simultaneously and fluctuate over time (Ajibade and Siders, 2021).

Despite the increased urgency of needing to move people away from high-risk areas there is still resistance to the use of managed retreat, and considerable difficulties with its implementation (Lawrence et al., 2020; Mallette et al., 2021). Several recent reviews of managed retreat literature address questions about how to undertake managed retreat in ways that deal with the complexities arising from implementation costs, compensation of relocatees, maladaptations from urban and rural planning and the insurance industry, and jurisdictional issues under the law (Ajibade et al., 2022; Dundon and Abkowitz, 2021; Kousky, 2014; Marter-Kenyon, 2020; O’Donnell, 2022; Pinter, 2021; Siders, 2019). Furthermore, finding an equitable or just approach to managed retreat is of increasing interest since it is often the economically, politically, and socially disenfranchised people who are the most vulnerable, and will suffer the most as a result of retreat (Ajibade and Siders, 2021; Loughran and Elliott, 2022; O’Donnell, 2022; Pinter, 2021; Simms et al., 2021; Thaler, 2021). This includes the loss of place.

2.2 Place and place attachment

Interest in place was led by the disciplines of human geography and environmental and social psychology (Williams and Miller, 2020), but it is now studied in almost all aspects of social science and the humanities (Devine-Wright, 2013b; Nelson et al., 2020; Patterson and Williams, 2005). This has resulted in the production of a large and growing body of literature, and a reputation that the field is complex (Relph, 2008). Several reviews—including those by Duggan et al. (2023), Edensor et al. (2020), Erfani (2022), Manzo (2003), Nelson et al. (2020), Patterson and Williams (2005), and Raymond et al. (2021)—capture many of the theories, methods and applications in place research. Here we only give an overview.

The concept of place evolved through several key societal movements that bred a diversity of philosophies and approaches, many of which continue to be practiced concurrently (Cresswell, 2009; Morgan, 2010; Williams, 2014a; Williams and Miller, 2020). The humanism movement of the 1970s was one of the most impactful periods in place research. During this time, humanists pushed back on modernistic ideas that neglected human-environment relations, in favor of prioritizing human experiences and meaning (Lewicka, 2011a; Raymond et al., 2021; Williams, 2014a; Williams and Miller, 2020). Later, critical constructivists focussed on how place was socially constructed through narratives, and shaped by politics, power, and social and cultural processes (Manzo and Pinto De Carvalho, 2020; Williams, 2014a; Williams and Miller, 2020). More recently, globalization, migration, and the increased mobility of people in general has resulted in what social science researchers Sheller and Urry (2006) coined the mobilities turn. The mobilities turn has challenged the view that mobility is a threat to place (Di Masso et al., 2019; Lewicka, 2020). Through these historical movements, place has evolved from being considered solely a geographic location, to becoming a place comprised of physical attributes, experiences and meanings (Relph, 2008), to more recently being thought of as complex and dynamic networks of things and connections (Edensor et al., 2020; Raymond et al., 2021; Williams and Miller, 2020). The fact that place research is not grounded in a single research tradition is often blamed for the lack of progress in theoretical coherence and maturity in place research (Herandez et al., 2020; Nelson et al., 2020; Patterson and Williams, 2005; Stedman, 2003).

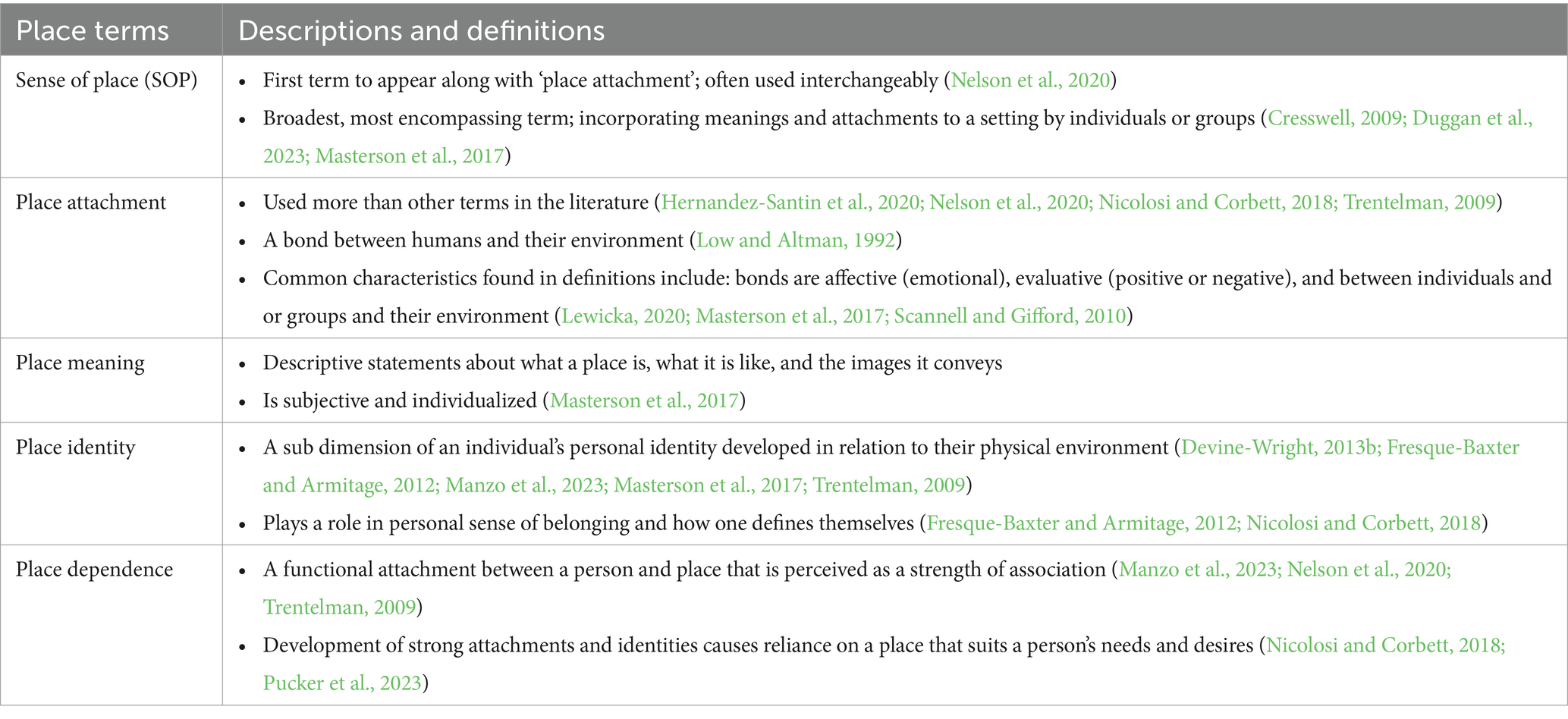

Many terms have been used in the literature to capture the nature and meaning of connection to place (Masterson et al., 2017; Patterson and Williams, 2005) (Table 1). Sense of place, place attachment, place identity, and place dependence are the main terms used (Manzo, 2003; Stedman, 2003). There are however, many other terms and phrases representing this connection to place found in the literature including topophilia (Tuan, 1974), community sentiment and identity (Low and Altman, 1992), the ancient Roman term genius loci (Patterson and Williams, 2005), sense of belonging, (Nelson et al., 2020), community attachment (Hernandez-Santin et al., 2020), and perception of place (Duggan et al., 2023). There is widespread criticism in the literature about the lack of conceptual clarity about the concept of place attachment. This could be due to the use of so many different terms and the lack of consensus about how they relate to each other (Devine-Wright, 2020; Manzo et al., 2023). Like with managed retreat, this makes it difficult to compare or accumulate research findings because disciplines frequently use different definitions for the same construct (Giuliani and Feldman, 1993; Masterson et al., 2017; Trentelman, 2009), or use terms interchangeably, despite subtle differences in meaning (Nelson et al., 2020; Williams and Miller, 2020).

For the purposes of this paper we adopt the term place attachment because it is the most frequently used term in the literature to represent connection to place (Hernandez-Santin et al., 2020; Nelson et al., 2020; Nicolosi and Corbett, 2018; Trentelman, 2009). Place attachment at its most basic is a bond between humans and their environment (Low and Altman, 1992). Common characteristics found in various definitions include that bonds are affective (emotional), evaluative (positive or negative), and between individuals and or groups and their environment (Lewicka, 2020; Masterson et al., 2017; Scannell and Gifford, 2010).

3 Methods

This review takes a narrative approach, in part due to the challenges of language described above. An initial search for research at the intersection of place attachment and managed retreat using those terms yielded very few results, so conducting a systematic review did not seem beneficial. Knowing there was relevant literature about place attachment and relocation available, we proceeded to broaden the search and consider managed retreat as a mobility-based concept. This allowed us to expand our search and explore other fields related to the movement of humans and assets in relation to place. We conducted our search on the Scopus database using the terms discussed in Section 2.1 to describe the movement of people and assets, and paired them with the main terms used in the literature for connection to place (as discussed in Section 2.2). Over 400 resources were captured in the search which included book chapters, but not books or conference papers. We also found many sources through the reference lists of other papers.

Screening focused on including the literature on relocation that shared similarities to managed retreat. Therefore, of particular interest to our review was literature about place attachment and climate-related relocation, and relocation that was permanent, planned or forced, and state-led. As a result, this excluded some results that focused solely upon human movement, or that was voluntary and self-motivated. The latter results correlated primarily with human movement literature on the Global South, so the reviewed literature ended up being heavily focused on the Global North. However, we did not exclude research about the Global South, nor did we exclude non-climate related relocation, particularly if it referred to how place attachment responded to relocation or place change. The remainder of the paper will review the literature found in these targeted domains.

4 Research fields at the intersection of place attachment and mobility

By taking a broader view of managed retreat as a climate-induced mobility, our search found several neighbouring mobility-based fields that have incorporated place attachment research, including migration and displacement, personal mobility, and forced relocation and resettlement. A brief discussion follows of these fields and how they may be similar or different than managed retreat.

4.1 Migration and displacement

Millions of people migrate within, or between countries each year. Migration can be driven by individual choices, such as seeking better opportunities, or in less voluntary ways, because situations are risky or untenable due to war, politics, or natural hazards (De Sherbinin et al., 2011; Hanna et al., 2019; Paul et al., 2024). Migration is typically unplanned, uncoordinated, and is the result of complex relationships between perceptions, needs, desires, real or perceived risks and benefits, and financial or legal ability to move (Barcus and Brunn, 2010; Koslov, 2016). Involuntary migration is often referred to as displacement and typically affects more vulnerable populations who frequently live in poorer, high risk areas (Paul et al., 2024). Conversely, lack of financial or social resources can lead to immobility, causing some people to be trapped in place (Koslov, 2016; Upadhyay et al., 2024).

Interest in migration caused by climate change is increasing so rapidly it has made its way into popular discourse with recently published non-academic books about the displacement of people away from areas of climate risk (Bittle, 2024; Vince, 2022). The current literature about climate change and migration, or climigration as it is often referred to, mainly focuses on determining the extra impact that climate change contributes to existing socio-economic drivers of migration, how and when climate change will affect which places, and how many people will migrate in the future (Upadhyay et al., 2024). However, the literature also illustrates the similarities between migration and managed retreat, such as when the drivers are climate-driven (Pinter, 2021).

Although there are many opportunities to learn from the field of migration, there are many distinctions between it and managed retreat. Ajibade and Siders (2021) point out that migration is primarily about human mobility and focuses on people in the Global South, whereas managed retreat is a withdrawal of people and the resources they value (e.g., homes, infrastructure, ecosystems, and other assets) (Ajibade and Siders, 2021, p. 102187). Ajibade et al. (2020) also outlines several specific distinctions between managed retreat and climigration, such as their causal mechanisms. Further, according to Ajibade et al. (2020) managed retreat is initiated directly from a climate hazard (i.e., sea level rise), whereas climigration is triggered by indirect climatic effects. For example, extreme heat could lead to drought which causes crop failure and food insecurity. People may thus be motivated to relocate to find areas that have more food resources. The two constructs also differ in their legal protections, rights and funding structures, and discursive effects (Ajibade et al., 2020; Hanna et al., 2019).

4.2 Personal mobility

Research in residential mobility has driven a significant proportion of place attachment research. Moving residences is typically voluntary and peaceful, driven by factors that pull people toward a new place, including benefits such as a better job or improved living conditions. Alternatively, people can be pushed from a place because their needs do not match what a current place offers (Dang and Weiss, 2021), their socioeconomic statues changes, or physical changes may make a place undesirable to live in (Kothari, 2020). In these situations, moving can feel positive, like a search for new opportunities or a liberation from constraints, or it can feel oppressive and out of one’s control (Madanipour, 2020; Williams and Miller, 2024). For example, tenants’ rights research identifies the perils of forced relocation of low to moderate income renters from no-fault evictions such as renovictions (eviction to allow for renovations) and demovictions (eviction to demolish aged housing stock), which are made in the name of housing stock and neighborhood renewal (Ramiller, 2022).

In the Global North personal mobility has become a normal part of people’s lifestyles rather than a one-off experience due to an increase in pleasure travel, commuting for work, second home ownership, and new technologies allowing for virtual travel or telecommuting (Cresswell, 2006; Gustafson, 2014; Lewicka, 2020). There is a tension identified in the literature among mobility, sedentarism, and privilege. This tension is heavily dependent on social position. Currently those who are able to opt into a mobile lifestyle are often considered more privileged than those who may be restricted in their movements, or are forced to move (Cresswell, 2009; Gustafson, 2001). However, it was not long ago that sedentarism was considered a privilege in place attachment research, and those who were able to have a secure and stable place to call home possessed an advantage (Di Masso et al., 2019). These debates have contributed to more interest in relocation and social justice issues which is only expected to increase as climate change intensifies (Ajibade et al., 2022; O’Donnell, 2022; Seeteram et al., 2023).

4.3 Forced relocation and resettlement

Approximately 15 million people are forced to relocate each year as a result of development induced/forced displacement and resettlement (DIDR or DFDR) (Doberstein and Stager, 2013; Piggott-McKellar et al., 2020; Wilmsen and Webber, 2015). This includes those relocated due to urban expansion, gentrification or redevelopment; and large infrastructure development like dams, hydro lines, mines, airports, national parks, and more recently green infrastructure projects such as windfarms (De Sherbinin et al., 2011; Hay, 1998; Vanclay, 2017; Wilmsen and Webber, 2015). Several authors have outlined similarities between DIDIR/DFDR and managed retreat cases, including that they are a result of human actions, can have long lead times (as is the case with sea level rise), and often impact the least powerful (Wilmsen and Webber, 2015). However, a major difference between the two fields, is that DIDR/DFDR projects are typically economically motivated and driven from the top-down (Hsu et al., 2019; Piggott-McKellar et al., 2020).

Natural disasters also force many people to relocate each year and motivates a substantial amount of research on place attachment and mobility. There is clear overlap between the fields of disaster risk and disaster recovery (DRDR) and managed retreat, especially when the drivers are climate-induced storms, floods, fires, and drought. This can sometimes make it difficult to distinguish the fields from each other in the literature. For example, some articles discuss DRDR and climate change adaptation (managed retreat is an adaptation tool) together and treat them the as one and the same (Doberstein et al., 2020). Although there are many similarities between the literature of place attachment and DRDR, and place attachment and managed retreat, there are also points of distinction. For example, the DRDR literature also includes temporary displacements (Iuchi, 2014), people eventually returning to place (Chamlee-Wright and Storr, 2009; Imura and Shaw, 2009; Paul et al., 2024), or situations in which people are not required to move at all, such as after earthquakes and volcanoes (Hsu et al., 2019; Piggott-McKellar et al., 2020; Wilmsen and Webber, 2015).

Forced relocation from DIDR/DFDR or DRDR may be structurally different and hold different implications for people than those experienced under managed retreat but they still provide useful insights into the social dynamics of population displacement (De Sherbinin et al., 2011; Pinter, 2021). For example, it is generally acknowledged in the DRR and DIDR literature that in the past, relocations have often had poor outcomes. Beyond the economic costs, these include exacerbation of historical inequities (Ajibade et al., 2022); the social, psychological, and cultural impact experienced by people when breaking of ties with cultures and communities (Ajibade et al., 2022; Hanna et al., 2019; Hino et al., 2017); top-down approaches that fail to communicate with and involve communities in meaningful ways (Hsu et al., 2019; Tadgell et al., 2018; Wilmsen and Webber, 2015; Yi and Yang, 2014); lack of long-term perspective (Imura and Shaw, 2009); adverse effects of power dynamics and government bureaucracy (Wilmsen and Webber, 2015); unsuitability of new locations; and lack of consideration of impacts on host communities (Perry and Lindell, 1997; Vanclay, 2017; Wilmsen and Webber, 2015). In order to address some of these lessons learned, organizations like the United Nations have produced resettlement policies and performance standards that focus on the protection of human rights of relocatees in developing nations (OECD-DAC, 1992; UN OCHA, 2004; UNHCR, 2015). Other researchers have also provided lessons learned from past relocations (Tubridy et al., 2021; Wilmsen and Webber, 2015), establishing guidelines for future relocations, including for less developed nations (Tadgell et al., 2018) and informal settlements (Doberstein and Stager, 2013).

5 Lessons from the literature

Important lessons about place attachment can be drawn from the various fields that encompass human movements discussed above. Since each mobility field differs in its similarities with managed retreat, some mobility fields contributed more resources to this review than others. The wide range of articles found illustrate how managed retreat affects place attachment and how it is influenced by place attachment. The key lessons are outlined below.

5.1 People have complex and changing attachments to places

5.1.1 People can have attachments to multiple different places

The mobilities turn in particular, has challenged the dominant paradigm of place attachment as sedentary, centred around a primary residence (home), and strengthened by longevity in place (Di Masso et al., 2019; Lewicka, 2020). It has caused place and place attachment researchers to grapple with the once-accepted idea that mobility is a threat (Devine-Wright, 2020; Lewicka, 2020; Williams and Miller, 2020) and to consider whether, instead of eroding place attachments, mobility can actually increase the number and types of attachments people hold. Research on multiple place attachments has centered around attachments to places other than a primary residence, including summer or second homes, wilderness and outdoor recreation areas (Lewicka, 2011a), meeting areas and public places, and sacred structures (Manzo, 2003). This research confirms what Brown and Perkins (1992) proposed long ago, that people can experience multiple attachments with a plurality of place meanings (Gustafson, 2014; Manzo et al., 2023). Devine-Wright and Quinn (2020, p. 226) suggest that with mobility becoming a lifestyle, more than ever people will experience a “mosaic of places” over their lifetime.

Within place attachment research, the life course approach explores how people attach to multiple places as they move through various stages of their lives (Di Masso et al., 2019). The life course paradigm has been part of social psychology research since the 1960s (Elder, 1994). Several studies explore people’s relationships to a multitude of places from childhood to retirement, capturing changes to place attachment over this span of time (Bailey et al., 2021; Di Masso et al., 2019; Giuliani and Feldman, 1993; Manzo, 2003). Bailey et al.’s (2016) research about a proposed power line addition in Bristol, England, builds on the life course approach. These researchers proposed that currently held residential place attachments are influenced by people’s life course trajectories. They proposed five distinct life course trajectories based on mobility patterns associated with different types of attachment, and found those who had a life trajectory characterized by living in one location for a long time were more rooted in place. For these people, power lines were deemed acceptable since they were always part of the landscape. The other extreme described people with life course trajectories that were more mobile. These people often moved to the area in search of places similar to their previous locations. They placed value on landscape aesthetics and viewed power lines as negative, ultimately opposing the power line project. This finding is consistent with research on place-based opposition by new residents. Life course research such as this highlights that people navigating place changes in their lives are often looking for continuity in their attachments and identity (Di Masso et al., 2019).

5.1.2 People can have many different types of attachments to a place

Along with research about having attachment to multiple different places, there is research about the idea people can have multiple types of place attachments to a place (Adams-Hutcheson, 2015). The concept of place attachment as singular has changed as researchers have sought language to capture the more nuanced linkages people have with places, and the sense of mobility within and across types of attachment (Bissell, 2020; Lewicka, 2011b; Devine-Wright, 2020b; Van Manen, 1990).

Gustafson (2001) explained that people could have static or dynamic place attachments. They considered traditional and sedentary place attachments in terms of roots, and the more progressive, mobility influenced perspective of attachments as routes. They also emphasized rather than being mutually exclusive, there was room for both static and dynamic place attachments to co-exist. For example, one may still enjoy the stability of having a strong, fixed connection to a primary residence, while mobility in the form of travel can provide an opportunity for connections to other places (Gustafson, 2014; Raymond et al., 2021). In a similar fashion, Di Masso et al. (2019) proposed a fixity and flow framework comprised of six different categories of place attachment that range in dynamism from fixed (representing a place attachment that is centered and anchored in one place), through various ratios of fixity-flow, to flow (which has an absence of anchors and could represent virtual or imaginative travel). Like the life course approach, this framework helps to show that people can have place attachments with different levels of mobility that can change as one navigates across the life course.

Hummon’s (1992) typology was one of the first to capture greater complexity in place attachment bonds by considering their emotional valence (positive or negative), their intensity (strong or weak), and their agency (active or passive). Lewicka (2011b) further developed Hummon’s five-fold typology by renaming the two types of positive rootedness as traditional and active attachments (Bailey et al., 2016; Devine-Wright, 2020; Hummon, 1992; Lewicka, 2020, 2011b). They also included Hummon’s three negative types of weak/non attachments, including alienation (dislike of place and desire to leave), place relativity (ambivalence or conditionally accepting attachment), and placelessness (place indifference or absence of emotional association with place). Of the two rooted types of positive place attachment, traditional attachments are thought to evolve through passive interaction with place (Bailey et al., 2016; Devine-Wright, 2020) by way of long-term rootedness such as familial or cultural ties (Pucker et al., 2023). Active attachments, in contrast, are more consciously made, often when people deliberately seek out a place and relocate there (Lewicka, 2020; Pucker et al., 2023). Overall, this refined typology by Lewicka has become the prevalent form used in the literature (Pucker et al., 2023).

Low (1992) furthered the idea of being able to have different types of place attachment at the same time by stating any of their proposed six types of place attachments could occur simultaneously. The different types of place attachment they proposed include genealogical, narrative, loss and destruction, economic, celebratory cultural events, and cosmological. Hay (1998) elaborated Low’s genealogical type to show these historical linkages have multiple layers, including personal, familial, ancestral, and cultural (Cross, 2015). Cross (2015) also proposes several place attachment types but refers to them more as processes that shape residents’ attachments. They state these processes are dynamic, occurring simultaneously, but each with a unique relationship to time (Cross, 2015). For example, “historical processes tend to deepen and expand attachment over time, while the narrative process might either deepen or weaken attachments … commodifying process generally fades over time while the spiritual process is notably static over time” (Cross, 2015, p. 515). They also note that these different types, or processes, of attachment can extend for long periods even after a person leaves a place (Cross, 2015).

Researchers have engaged in research that correlates various types of place attachment with different variables such as personality type, education, age, and social relations (Lewicka, 2020). There have also been studies looking for links between an individual’s predominant type of attachment and their response to a disruption (Lewicka, 2020). For example, people with more active attachments may be able to adjust more quickly to a disruption than those whose place attachments are based on long-held daily routines (traditional attachments) (Lewicka, 2020). Other studies have compared types of place attachments to environmental threat response (Sullivan and Young, 2020), coping styles related to climate change (Parreira and Mouro, 2023), responses to community energy projects (Devine-Wright, 2013c; Van Veelen and Haggett, 2017), and to flood preparedness behavior (Mishra et al., 2010). These types of studies help provide more insight into how people may respond to different disruptions based on the types of attachments they have.

5.1.3 People can have attachments to places they visit for short periods of time or visit virtually

Research in residential mobility has explored place attachments and short-term and non-migratory relocation due to work travel and tourism, and in virtual settings (Bailey et al., 2021; Bissell, 2020). Innovations in travel infrastructure have increased mobility for work as well as for tourism (Di Masso et al., 2019; Gustafson, 2001). Employment-related mobility includes daily commuting, travel for work such as meetings and conferences, or relocation for longer periods of time (i.e., seasonal employment and fly-in/fly-out work; Bissell, 2020). Research in tourism explores the idea of having attachments to distant places in which we may not spend much time, especially recreation sites (Devine-Wright, 2020; Di Masso et al., 2019).

Research in such fields has brought attention to the differences between those who feel they belong in a place (i.e., insiders, such as residents who work and live in a place), and those who do not belong (i.e., outsiders, such as tourists and visitors to a place) (Gustafson, 2001; Lewicka, 2011a; Relph, 1976). For example, Gurney et al. (2021) and Marshall et al. (2019) found that after a coral bleaching event at the Great Barrier Reef, both residents and tourists reported a form of climate grief (an expected or real sense of loss due to degradation to places and ecosystems; Allen, 2020; Marshall et al., 2019) and solastalgia (“the inability to derive solace from the present state of one’s environment”; Philippenko et al., 2021, p. 21). They found residents (insiders) who had a more meaningful relationship with the reef had higher rates of solastalgia and climate grief than those who were more interested in the aesthetic value of the reef (outsiders). Adams-Hutcheson (2015) found, among people relocated after an earthquake in New Zealand, that feelings of being an insider or an outsider were not mutually exclusive. Further, they found that strong place attachments could interact with the insider-outsider dynamic such that those who relocated felt like outsiders compared to those who were allowed to stay in place. This may undermine the sense of belonging and ability to make new attachments among the relocated.

Advancements in communication technologies will also require new ways of exploring how connections between people and places are evolving as more people have a ‘virtually’ mobile lifestyle without having to physically relocate (Barcus and Brunn, 2010). Within place attachment research scholars have proposed that virtual mobility may overcome geographical distance, allowing one to be attached to places visited by way of visual images, or virtually online (Di Masso et al., 2019; Gustafson, 2014). In essence, allowing us to be in two places at once (Di Masso et al., 2019). The idea of being transported elsewhere through technology could help recreate, maintain, or change place attachments to places left behind as well as places people have yet to visit (Di Masso et al., 2019).

An example of the potential of technology in this context is the concept ‘place elasticity,’ a form of attachment proposed by Barcus and Brunn (2010) that recognizes how we can stretch our place boundaries. Such stretching is often driven by advances in transportation and technology, allowing for increasingly virtual relationships and connections with places where we used to live. Place elasticity allows for long-term engagement and connections to occur despite not living in, or even visiting, a place. This allows people to take advantage of economic or social opportunities away from the places which they physically live. Di Masso et al. (2019) emphasizes that these types of virtual attachment do not replace conventional place attachments. The research in this field challenges the long-held belief that development of place attachments is a slow process that depends on length of time in a place. Arguing that meaningful place attachments can also be created more quickly, Devine-Wright (2020) suggests follow-on questions including whether more mobile people have more place attachments, and how tangible place must be to foster attachment.

5.2 Place attachments are dynamic

5.2.1 Place attachment is a dynamic process

Place attachment research has traditionally focused more on the existence, strength and shape of attachments rather than the dynamic processes of attaching, detaching, and reattaching to place over time (Cross, 2015; Devine-Wright and Quinn, 2020; Fried, 2000; Grocke et al., 2022; Gustafson, 2014; Scannell and Gifford, 2010). Massey (1991) and Brown and Perkins (1992) were early critics of place being seen as only singular and static, which was a popular stance of humanistic geographers at the time (Dickinson, 2019). As places increasingly began to be considered more complex and dynamic, place attachments evolved along parallel lines (Dandy et al., 2019; Giuliani and Feldman, 1993; Gustafson, 2014; Lewicka, 2020). Place attachments are now thought to be dynamic, continually being (re)constructed, adapted, reshaped, and ebbing and flowing over time (Kim, 2021; Williams and Miller, 2020).

The literature sometimes refers to the process of how people-place bonds form as building place (Million, 1992) or place-making (Kothari, 2020; Williams, 2014b). Phenomenologists, such as Seamon (2014), have long argued that dynamic processes occur simultaneously to make place (Cross, 2015). For example, Seamon proposes that place-making develops through the everyday habitual body movements (i.e., walking to work, picking kids up from school etc.), that make up what he refers to as a body ballet of compounding daily, weekly, and monthly routines (Cresswell, 2009; Cross, 2015; Lewicka, 2011a; Seamon, 2014; Williams and Miller, 2020). Grocke et al. (2022) reiterates the idea that dynamic processes contribute to the place attachment process through “the dynamism of decision-making that constantly evaluates changes to social-environmental settings and the reiteration of the bonding process” (p. 301). Here, it is important to note, that planners, architects, and landscape architects also use the term ‘place-making’ but in a different context; deliberately designing places to improve community well-being and livability (Marshall and Bishop, 2015). Such work is outside the scope of this review.

Conceptual frameworks have been proposed by several authors in attempts to characterize the place attachment process after a disruption to a place or during a relocation (Brown and Perkins, 1992; Devine-Wright and Quinn, 2020; Greene et al., 2011; Inalhan and Finch, 2004; Million, 1992; Prewitt Diaz and Dayal, 2008). Although the frameworks vary, they all have a loose structure of a period before the disruption happens where there may or may not be preparation for change, followed by transition and recovery stages. The process is seen as a continuum but it is not linear in its progression (Kothari, 2020; Whittle et al., 2014). Additionally, the stages do not have clear edges and they may overlap with each other (Whittle et al., 2014). Little research has been done to understand mechanisms within the process (Lewicka, 2020; Manzo and Devine-Wright, 2020b) but it is thought to take considerable work because one must successfully let go of existing attachments (detach), re-establish old attachments, or create new ones in a new location (Brown and Perkins, 1992; Devine-Wright and Quinn, 2020; Dickinson, 2019; Perez Murcia, 2020; Zheng et al., 2019).

A few researchers have explored what happens in the transition stage of the place attachment process, finding it a dynamic time that is disorienting to people (Cox and Perry, 2011; Madanipour, 2020; Prayag et al., 2021; Silver and Grek-Martin, 2015). People feel unmoored during this period because disruption causes the loss of physical and psychological markers and forces changes to people’s routines, both of which in turn affect their sense of continuity and stability (Cox and Perry, 2011; Madanipour, 2020; Silver and Grek-Martin, 2015). Eventually people start to reorientate themselves and find their bearings by reconstructing their identity as they navigate through the psychological, social, and emotional responses to change they have experienced (Binder et al., 2019; Cox and Perry, 2011). Cox and Perry (2011) found place attachment to be important to reorientation because it helped to recreate community and self-identity through repeated cycles of disorientation and reorientation. Similarly, Harms (2015) referred to circuits of displacement and emplacement with each circuit having a role in the cumulative process of place making. These studies contribute to the understanding that place attachment bonds are in a process of continuous instability and renegotiation during a disruption (Madanipour, 2020).

The recovery stage of the place attachment process after a disruption is also not well understood, especially when relocation is required (Adams-Hutcheson, 2015; Dickinson, 2019; Rumbach et al., 2016; Whittle et al., 2014; Zheng et al., 2019). The term emplacement has been used to describe the processes of building or rebuilding connections after disruption or relocation (Kothari, 2020; Perez Murcia, 2020). Similar to place-making, this can be achieved by developing new habits and rituals that will result in new (re)attachments (Prayag et al., 2021) and by “renegotiating conflicts and reconciling losses and trauma” (Zheng et al., 2019, p. 7). Million (1992) also indicates the recovery period is a time when reflective reconciliation begins and displacement recedes to the background. They add that there may be moments that “jolt us back to our loss” (p. 199) which reminds us that the recovery process is recursive and not linear (Million, 1992). As for when this recovery process might be completed, Million (1992) muses that rebuilding place may be done after “the emergence of both the past and the future alongside the present during the course of daily involvements with daily things” (p. 207). Winstanley et al. (2015) indicates that despite irreversible change having happened, recovery is achieved when one “no longer has to renegotiate how to carry out everyday life activities, while acknowledging degrees of adaptation and change in the physical environment, in social interaction and in individual psychologies and behaviours” (p. 128).

5.2.2 Place attachments change during place change/relocation

The research is quiet about the specifics of how and when detachments and reattachments occur but there are several studies illustrating that place attachments do change when there is a disruption to place or a relocation from place. Chow and Healey (2008) are frequently referred to as one of the first to do a longitudinal study showing changing place attachments. Their research captured the transitional process first-year university students experience when they move away from home to a new social and cultural environment. Specifically, they studied students over a five-month period and found that place meanings were constantly being evaluated and re-defined after relocation. They acknowledge this may be influenced by the students’ age and stage of life, both of which present other complexities. Kim (2021) also found people’s attachments to place changed during neighborhood change caused by increasing short term rentals and overcrowding from tourism. In particular, they found that residents experienced fluidity in their attachment to place as they “continuously construct, adapt and reshape their connections to place” (Kim, 2021, p. 129). Further, they showed that place attachments could amplify or attenuate during neighborhood change depending on a variety of factors including proximity to development or how changes impact residents’ quality of life. Cheng and Chou (2015) also found that bonds grew or weakened depending on initial levels of attachment. Considering an environmental corollary to neighborhood change, Gurney et al. (2021, p. 27) found “emotional and intangible elements of sense of place” (including pride, place identity and place attachment) became heightened during reef decline, when more “instrumental elements of senses of place” (lifestyle and aesthetics) declined.

5.3 Place attachments play a role in decisions to relocate

5.3.1 Place attachments inhibit more than prompt decisions to relocate

Understanding environmental behavior is a primary focus in place attachment research, including the role of place attachment in the decision to relocate away from a risk (Feng et al., 2022; Solecki and Friedman, 2021). Multiple factors are involved in a person’s decision to relocate including economic, social, environmental, political, and emotional considerations, which make each situation unique (Chan et al., 2022; Dandy et al., 2019; Kothari, 2020). Among these factors, place attachment has been found to play an important role in a person’s decision to relocate (Bukvic and Barnett, 2022; Dandy et al., 2019; Mallette et al., 2021), either inhibiting or prompting a decision to leave (Bukvic et al., 2022; Dandy et al., 2019).

Although there are examples of place attachments prompting a decision to leave (Dandy et al., 2019; Depari and Lindell, 2023; Holley et al., 2022), overall, the majority of research shows strong place attachments are a barrier to relocation (Dandy et al., 2019; Masterson et al., 2017; Steimanis et al., 2021; Swapan and Sadeque, 2021). Several studies have found individual and community place attachments, among other factors, played a role in decisions not to migrate (Adams, 2016; Sengupta and Samanta, 2022; Upadhyay et al., 2024), or not to relocate when exposed to climate risks in particular (Dannenberg et al., 2019; Fattah Hulio et al., 2023; Holley et al., 2022; Phillips et al., 2022; Woodhall-Melnik and Weissman, 2023; Yee et al., 2022). This seems to contradict a common perception that disasters make people devalue place and relocate to safer areas (Oracion, 2021). Nevertheless, as Gurney et al. (2021) found around the Great Barrier Reef, if a place has been threatened or disrupted sometimes people become more aware and appreciative of their environment (McKinzie, 2019), strengthening their attachment to it (Binder et al., 2019; Cox and Perry, 2011; Devine-Wright and Howes, 2010; Lemée et al., 2019; Lewicka, 2020). This phenomenon is often referred to as latent place attachment and can affect relocation decisions, often adding to people’s determination not to relocate (Binder et al., 2019).

Based on the assumption that strong place attachments are a barrier to relocation, Bukvic et al. (2022) and Rey-Valette et al. (2019) mapped the strength of place attachments to predict future willingness to relocate from coastal risks in the eastern US and the south of France, respectively. Bukvic et al. (2022) found rural residents tended to have higher place attachment and determined such residents would therefore be less willing to relocate, and Rey-Valette et al. (2019) found there was a correlation between willingness to relocate and distance from the sea, where those further from the sea were more willing to relocate. Both studies were meant to inform planning and policy decisions by helping to understand who might be more open or resistant to relocation. Bukvic et al. (2022) also developed regional maps displaying exposure to coastal flooding. When compared to maps showing place attachment strength, they could identify which people living in high-risk areas may be more likely to relocate. In this situation, communities with lower place attachment could be targeted first for relocation and act as a signal for others with higher attachment to place who may be more resistant.

5.3.2 Risk perception and place attachment can influence each other in decisions to relocate

The contribution of risk perception to understanding the relationship between place attachment and decision to relocate is complex (Bonaiuto et al., 2016; Lie et al., 2023). In some cases, strong place attachment affects risk perception by making people more aware of environmental risks, resulting in increased risk coping behavior. For example, Woodhall-Melnik and Weissman (2023) found that those who were aware and concerned about future risks openly discussed willingness to relocate. Similarly, Quinn et al. (2018) found people with low place attachment were less likely to perceive flood risk and therefore less likely to feel motivated to choose adaptation measures like moving.

In other cases, strong place attachment diminishes risk perception, leading to actions that contribute to immobility (Jamali and Nejat, 2016; Lie et al., 2023; Steimanis et al., 2021). For example, Costas et al. (2015) and De Dominicis et al. (2015) both studied coastal communities facing risk from sea level rise and flooding, and found that place attachment moderated risk perception by leading to the underestimation of the impact of risk. This in turn weakened communities’ risk-coping intentions. Further, Pucker et al. (2023) found strong place attachment in Hawaiian residents living in vulnerable coastal areas made them feel secure enough to stay and handle changes that might happen to their place. This is often referred to as risk perception normalization (Dang and Weiss, 2021) or optimism bias (Solecki and Friedman, 2021). In these situations, residents seem to accept the risk (i.e., living near the coast) in exchange for benefits including the sense of permanence and stability offered to them by place attachment (Costas et al., 2015). In some circumstances however, diminishing risk perception and coping intentions could restrict other life opportunities (Jamali and Nejat, 2016), or put people in danger if they are in high-risk situations and they do not relocate (Chan et al., 2022; Dannenberg et al., 2019; Lewicka, 2011a; Masterson et al., 2017; Phillips et al., 2012).

Lastly, a few researchers have focused on how specific types of place attachment can affect response to a risk (i.e., stay or move away from a risk) (Devine-Wright, 2013c; Mishra et al., 2010; Sullivan and Young, 2020; Van Veelen and Haggett, 2017). With regards to making the decision to move away from a risk, Quinn et al. (2018) found people with relative (ambivalent) place attachment types at the town scale were less likely to perceive flood risk, which in turn affected their choice not to move. Similarly, Parreira and Mouro (2023) found active (intentional) attachment types were associated with higher risk perception and adoption of coping strategies like moving due to sea level rise. Lie et al. (2023) characterized different dimensions of place attachments and found bonds made through generational ties, historical knowledge, and closeness to nature increased risk awareness of flooding but did not necessarily translate into risk perception. However, Lie et al. (2023) are not alone in finding that place dependency and family bonds influenced people to not relocate (Woodhall-Melnik and Weissman, 2023).

5.4 Place attachments play positive and negative roles during place change/relocation

5.4.1 Disruption to place attachments due to place change/relocation can have negative consequences to health and well-being

Many factors can influence individual and community place attachments after a disruption to place or due to a relocation. These include the existing characteristics of individuals and communities (Jamali and Nejat, 2016; Rumbach et al., 2016) and the characteristics of the disruption itself (Barcus and Brunn, 2010; Di Masso et al., 2019; Solecki and Friedman, 2021).

Disruptions and relocations result in physical changes as well as changes to symbolic meanings and social aspects of place (Manzo et al., 2023). Further, in personal mobility studies, it has been known for some time that frequent relocation negatively affects physical health (Stokols et al., 1983), but there is increasing understanding that relocation can also severely affect psychological health and well-being (Carroll et al., 2009). One of the earliest studies about place attachment and mobility is Fried’s (1966) study on the forced relocation of a Boston neighborhood due to urban renewal. The frequently cited study found residents experienced grief and mourning when relocated. They also found that community ties either provided stability, allowing people to be highly functional, or prevented them from embracing wider life opportunities that mobility may provide (Fried, 1966). Psycho-social responses to disruptions or to a relocation can include profound feelings of loss for both tangible (possessions, homes, infrastructure), and intangible elements (Alston et al., 2018; Kothari, 2020; Prewitt Diaz and Dayal, 2008). Intangible losses can include histories, identity, social cohesion, belonging and community, and place attachments (Alston et al., 2018; Kothari, 2020).

More specifically, a disruption to a place or a relocation can strain or rupture people-place bonds (Quinn et al., 2015). This requires individuals to change or rearrange their old daily routines and habits (Dickinson, 2019; Lewicka, 2011a), and their psychological processes of cognition and affect (Zheng et al., 2019). Changes such as these can cause fear, anxiety and stress (Cheng and Chou, 2015; Phillips et al., 2022; Woodhall-Melnik and Grogan, 2019), a sense of powerlessness (Phillips and Murphy, 2021), and can produce feelings of nostalgia, alienation, or a sense of placelessness (Fullilove, 1996; Zheng et al., 2019). These feelings can undermine the positive aspects of place attachment such as a sense of stability, connectivity, security, and well-being (Fresque-Baxter and Armitage, 2012; Fullilove, 2014; Jamali and Nejat, 2016; Phillips and Murphy, 2021; Woodhall-Melnik and Grogan, 2019; Zheng et al., 2019). Research shows that relocation in particular adds stress to the disaster experience (Adams-Hutcheson, 2015) because being physically separated from your group identity and your sense of security affects mental health more profoundly (Dannenberg et al., 2019; Jamali and Nejat, 2016; McMichael and Powell, 2021; Porter, 2015; Woodhall-Melnik and Grogan, 2019).

Several expressions have been introduced to the lexicon to convey the loss, grief and mourning caused by disruptions to place or relocation from place (Fried, 2000; Phillips and Murphy, 2021; Silver and Grek-Martin, 2015). These include solstalgia (“the inability to derive solace from the present state of one’s environment”; Philippenko et al., 2021, p. 21) and rootshock (a “traumatic stress reaction to the loss of one’s emotional ecosystem”; Fullilove, 2014, p. 149). Both concepts have been found to affect people’s ability to cope and could be exacerbated by place attachment (Fried, 2000; Gurney et al., 2021; Marshall et al., 2019; Silver and Grek-Martin, 2015). The concept of climate grief has also been introduced (an expected or real sense of loss due to degradation to places and ecosystems) and is applicable to disruptions that are specifically climate-related (Allen, 2020; Marshall et al., 2019).

5.4.2 Place attachments have a dualistic role in recovery from place change/ relocation

After a disruption to place or a relocation, emphasis has traditionally been on a return to normal as fast as possible with the focus on physical and economic recovery over social-psychological concerns (Cox and Perry, 2011; Dickinson, 2019). However, rebuilding community, identity and belonging is also important (Perez Murcia, 2020), and increasingly the idea of fostering physical, mental and social wellbeing in parallel is increasingly considered important for recovery (Fresque-Baxter and Armitage, 2012; Prayag et al., 2021; Woodhall-Melnik and Weissman, 2023).

A challenge identified in the literature, however, is that place attachment may have dual roles in recovery, just like it does in decision to relocate (Table 2). On the one hand, place attachments can act as a barrier to, or hindrance to recovery, potentially making it harder to move forward in the recovery process (Binder et al., 2019). For example, change may feel so overwhelming that people want to protect their existing place attachments and identities in order to maintain some stability and security, even if those are only illusory (Fresque-Baxter and Armitage, 2012). This may inhibit people detaching from existing places enough to move them forward in the recovery process. Adams-Hutcheson (2015) also found strong place attachments can undermine relocated individuals’ sense of belonging and ability to make new attachments if they feel like outsiders compared to those who were allowed to stay in place. Lastly, Lewicka (2020) suggested that an individual’s predominant type of attachment may also affect their response to the overall impact of a disruption. Specifically, they proposed people with more traditional place attachments that are based on long-held daily routines may take longer to adjust after a disruption than those with active attachment types.

Table 2. Positive and negative roles of place attachment (PA) in decisions to relocate and in recovery after a disruption/relocation.

On the other hand, place attachment has also been found to act as an aid to recovery and to promote healing after a disruption (Jamali and Nejat, 2016; Paul et al., 2024; Prayag et al., 2021; Winstanley et al., 2015; Woodhall-Melnik and Grogan, 2019). For example, latent place attachments that strengthen after a disruption or relocation may inhibit detachment of old bonds, but they may also help with recovery. In particular, research has found that individual and community place attachments play a large role in the development and maintenance of social capital through social ties (Cox and Perry, 2011; Prayag et al., 2021). Social capital has been identified as playing a critical role in disaster recovery and is an indicator of overall well-being (Binder et al., 2019; Jamali and Nejat, 2016; Prayag et al., 2021; Quinn et al., 2021, 2015). However, the buffering effects of social connections may not be possible in situations where residents are relocated permanently and scattered (Quinn et al., 2021). For individuals who stay in or return to place, however, disasters can also lead to communal coping where communities come together during a disruption. This helps provide purpose, identity and fosters reconnection (Adams-Hutcheson, 2015; Silver and Grek-Martin, 2015; Woodhall-Melnik and Grogan, 2019). Understanding how to renew place attachments after a disruption or relocation may be an important factor in recovery to a new normal.

5.4.3 Place attachments may be able to provide stability during place change/relocation

Place attachment can have a positive impact on recovery by providing stability and purposeful direction while people are undergoing change (Di Masso et al., 2019; Manzo et al., 2023; Williams and Miller, 2024) (Table 2). People generally seek security and stability in their lives (Feldman, 1990; Lewicka, 2020), but rapid or ongoing changes to place can lead to feelings of instability and can affect our ontological security. Ontological security is a state that exists when one has safety and stability, both individually and collectively, that allows for the development of personal and group identity (Giddens, 1991; Laing, 1964). Brown and Perkins (1992) and later Manzo et al. (2021) proposed that people are constantly balancing a mixture of stable/fixed and changing/fluid place attachments to maintain a sense of security as they navigate through their lives. When a disruption or change occurs that overwhelms people, they may be able to find a “thread of continuity or stability” via their place attachments (Manzo et al., 2021, p. 282).

Minimizing and restoring broken bonds quickly after a disruption will obviously help maintain or re-establish a sense of security and could be important components of recovery (Lewicka, 2020). However, Brown and Perkins (1992) and Brunacini (2023) argue that the intentional loosening of existing attachments to place and related obligations (detachment), may also be a way to help navigate periods of instability. This implies that we can prepare people by increasing their anticipation of place detachment, and untangle their emotions about a current place while simultaneously imagining a new existence in a new place (Agyeman et al., 2009; Brown and Perkins, 1992; Brunacini, 2023; Giuliani and Feldman, 1993; Tschakert et al., 2017). By encouraging detachment to begin in the pre-disruption phase, perhaps recovery can start prior to relocation and the two processes of detachment and emplacement can occur simultaneously (Kothari, 2020; Tschakert et al., 2017). This could help an individuals’ stability and resilience, and potentially prompt a recovery experience more like those who relocate voluntarily (Brunacini, 2023; Manzo, 2003; Prayag et al., 2021; Quinn et al., 2015). This may work best in situations where there is a long pre-disruption phase, such as for those facing a slowly changing place or anticipating relocating in the future (Agyeman et al., 2009; Brown and Perkins, 1992; Brunacini, 2023; Giuliani and Feldman, 1993; Tschakert et al., 2017).

Residential mobility research explains how relocated people often try to (re)establish or maintain a sense of self continuity by choosing similar types of settlements (i.e., suburban, urban, rural, etc.), a phenomenon called settlement identity (Devine-Wright and Quinn, 2020; Feldman, 1990; Gustafson, 2001; Scannell and Gifford, 2010). Choosing similar settlement types may cause less disruption to people’s identity and personal sense of continuity, and it may help them grow roots in new places quicker (Feldman, 1990; Lewicka, 2020). Place congruent continuity is a similar concept that describes matching one’s self-concept to place features (i.e., I am a country person, I am a city person) to help maintain a sense of continuity in one’s life (Feldman, 1990; Lewicka, 2020). Lewicka (2020) describes two other ways people use places to serve as sources of continuity, including place referent continuity, which is triggered by conscious or unconscious memories of place, and perceived continuity, where place is perceived through its continuous history. These concepts can potentially inform future mobility decisions and place attachment formations (Bailey et al., 2021).

Lastly, a new conceptual tool has been proposed that may give insight in how to maintain ontological security through disruption/relocation (Williams and Miller, 2024). Building on the work of early champions for a more holistic and dynamic view of place (Brown and Perkins, 1992; Cresswell, 2009; Williams and Miller, 2020), several researchers suggest that places are uncentered, complex “multi-scaled relations of materials and flows” that normalize change over time and space (Williams and Miller, 2024, p. 298). Massey (1991) refers to these structures as constellations. Others suggest webs (Raymond et al., 2021), assemblages, or rhizomes (Williams and Miller, 2024). Their rationale is that these web-like structures can easily accommodate a more progressive view of place attachment, which considers individuals and communities to have multiple place attachments that: are plural in discourse and practice, vary in type and strength (Kim, 2021; Williams and Miller, 2020), represent a broad range of positive and negative emotions (Dandy et al., 2019; Manzo, 2003), are created by a variety of memories, emotions and experience (Manzo and Devine-Wright, 2020b), and are dynamic, ebbing and flowing over time (Kim, 2021; Williams and Miller, 2020). By considering places and attachments in this way, mobility and transitions can be normalized, allowing for (re)connection of people and communities to a multiplicity of places at various spatial and temporal scales (Berroeta et al., 2021; Manzo et al., 2021; Williams and Miller, 2024). This perspective may provide people a way to feel their ontological security is less impacted through disruption or relocation (Williams and Miller, 2024).

6 Conclusion

Renewed interest in managed retreat is driven by the urgency of climate change responses. Millions of people currently live in low-lying floodplains and high-risk coastal areas, and may need to relocate in the future due to climate-related flooding and sea-level rise. Managed retreat is a difficult climate adaptation option to undertake because it triggers a complex mix of economic, social-cultural and psychological factors. Place attachment is among these psycho-social factors that can contribute to understanding more about managed retreat. Specifically, how can place attachments change over the course of managed retreat, how can managed retreat affect place attachment and vice versa, and how can place attachment impede managed retreat or promote recovery? Research into these questions is currently limited and broadly distributed across fields and vocabularies (Bukvic et al., 2022), which could partially be a result as well as cause of the incomplete conceptualization of both constructs. Taking a broader view of managed retreat as climate-induced mobility has allowed us an opportunity for insight into place attachment research that may help managed retreat researchers and practitioners move the field forward. For example, research on the broader concepts of personal mobility and forced relocation have contributed to our understanding of place attachments by way of concepts like settlement identity, place elasticity and the life course approach. Other specific findings from our review that have improved understanding of place attachment and how it may inform human responses to retreat are summarized below.

Current research supports a more progressive view of place attachment that is complex, dynamic, and frames mobility not as a threat but as something more akin to an opportunity (Dandy et al., 2019; Giuliani and Feldman, 1993; Lewicka, 2020). Growing in acceptance is the idea that places can have multiple contested identities based on different perspectives, and individuals and communities have multiple types of attachments to a place that vary in type, valence, and strength, as well as over time (Kim, 2021; Williams and Miller, 2020). Further, they can have attachments to several different places, even those they have visited temporarily or virtually. More understanding is needed about the characteristics of different type of attachments, their relationships to each other, and how they influence and respond to change (Marshall et al., 2012; Masterson et al., 2017). This web-like view of place attachments raises questions about how the number and diversity of attachments influences our mobility patterns and our response during place change or relocation.

Although research on the dynamic nature of place attachments is sparse, there is greater receptivity to the possibility that they can change over time as they are continually (re)constructed, adapted, and reshaped (Kim, 2021; Williams and Miller, 2020). Disruptions to place, including relocation, reveal there is a non-linear, fluid process that place attachments may follow through pre-transition, transition, and recovery stages. Little is known about the temporal characteristics of each stage or how bonds detach and reattach. However, there is some understanding that the transition period is a tumultuous time when people move through cycles of disorientation and reorientation, which may help them move toward recovery by detaching, reorienting, and renegotiating place attachments (Cox and Holmes, 2000; Harms, 2015; Silver and Grek-Martin, 2015). We concur with researchers who call for more research to understand processes about how bonds to place are formed, developed, and sustained over time, as well as what happens when they are disrupted (Bailey et al., 2016; Brunacini, 2023; Cheng and Chou, 2015; Cross, 2015; Manzo and Devine-Wright, 2020b; Lewicka, 2011a). There is specifically a gap about place attachment changes during relocation (Adams-Hutcheson, 2015).

Making the decision to relocate is complex and is influenced by many factors including place attachment. The literature also indicates that place attachments have a dualistic role, helping or hindering the decision to relocate, and during recovery after a place change or relocation. This dual nature of place attachment is complicated, and there is still a lot of work needed to disentangle the nuances of the nature of place attachment and how it motivates some people to relocate, while constraining others (Woodhall-Melnik and Weissman, 2023).

There is a growing understanding that disruption to place attachments can have negative consequences on people’s physical and mental health and wellbeing. However, the stability and ontological security that place attachments provide, and which can have positive effects, are less understood. The promise that place attachment offers in reinforcing self-continuity should be better studied to understand its utility for promoting recovery and reinforcing self-continuity in persons who experience managed retreat (Brown and Perkins, 1992; Brunacini, 2023; Giuliani and Feldman, 1993; Lewicka, 2020; Masterson et al., 2017; Tschakert et al., 2017).

Full pre-and-post disruption longitudinal studies are presently rare but would be helpful to understand the dynamism of the psycho-social processes, including place attachments, that people undergo following disruption over a long period of time (Cox and Perry, 2011; Cross, 2015; Dang and Weiss, 2021; Devine-Wright and Quinn, 2020; Kothari, 2020; Lewicka, 2011a; Masterson et al., 2017; Zheng et al., 2019). As well, more qualitative studies are needed as they can offer a more nuanced understanding about decisions to relocate and the place attachment process, than can traditional quantitative studies that use surveys and self-report measures to determine the existence and strength of place attachments (Binder et al., 2015; Cheng and Chou, 2015; Devine-Wright and Quinn, 2020; Herandez et al., 2020; Lewicka, 2011a). For example, Simms et al.’s (2021) qualitative study of Isle de Jean Charles residents helped policy makers understand the deep connection residents had with their land and resulted in a change to a standard policy restricting access to properties left behind. By allowing continued access to their old land, residents have been able to maintain some emotional connection to the ‘old’ place, which played a role in their decision to accept a buyout while easing the relocation transition.