- 1Milano School for Urban Policy, Management and the Environment, The New School University, New York, NY, United States

- 2Urban Systems Lab, The New School University, New York, NY, United States

- 3Department of Human Geography and Spatial Planning, Utrecht University, Utrecht, Netherlands

- 4Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies, Millbrook, NY, United States

- 5Stockholm Resilience Centre, Stockholm University, Stockholm, Sweden

Sea level rise and increasing frequency and intensity of coastal storms are driving the need for managed retreat and relocation for at risk coastal populations. Managed retreat through voluntary buyouts is typically studied either from the perspective of the buyouts’ process or focused on those who leave, but little attention is given to who and what is left behind. How do buyouts impact those staying behind, and their senses of justice? We examine this question for the low-lying majority-minority neighborhood of Edgemere, Queens in New York City where Superstorm Sandy buyouts and a long history of failed urban renewal have led to large amounts of vacant land. This study analyzes ongoing and intersectional conditi ons of residents’ flood vulnerability. It grounds this analysis in 18 in-depth interviews with local residents capturing their perceptions of vacant land and its reuse, flood risk and neighborhood needs. The analysis is complemented with field observations, semi-structured interviews with city agencies involved in resilience planning initiatives and analysis of historical urban planning and open space plans in this area. Findings reveal the importance of elevating residents’ understanding of place to inform possible land uses after retreat in historically disinvested neighborhoods. Furthermore, they reveal both the injustices of and attachments to living in flood prone, disenfranchised coastal neighborhoods. They also show how these experiences entangle with the citywide housing crisis. In conclusion, if retreat and post-buyout efforts aspire to be just, they need to center how past and present contextual injustice shapes the relationships between distributive and recognitional injustice.

1 Introduction

With increasing extreme events such as cloudbursts, hurricanes and storm surges, coastal and riverine neighborhoods are at the forefront of the climate emergency. Managed retreat through voluntary buyouts is no longer “America’s last-ditch strategy” (Flavelle, 2018) in disaster management, due to the astronomical economic impacts of flooding (NASEM, 2019) rising cost of flood insurance (FEMA, 2023) and the challenge of rebuilding (Atoba et al., 2021). The process of property buyouts is however marred in procedural hurdles, heightening anxiety and opposition to it (Lynn, 2017; Dundon and Abkowitz, 2021; O’Donnell, 1854). Many scholars raise concerns about the equity implications of buyout processes and outcomes (Maly and Ishikawa, 2013; Muñoz and Tate, 2016; Lynn, 2017; Baker C. K. et al., 2018; Siders, 2019; Shi et al., 2022), especially for those who receive a buyout and relocate (Hino et al., 2017; McGhee et al., 2020) but less so for those who stay, exceptions include Koslov (2021) and Kimbro (2021). Buyouts tend to occur more often in pockets of high social vulnerability and racial diversity within majority-white neighborhoods (Mach et al., 2019) and while some of the conditions under which people decide to retreat are known (Robinson et al., 2018; Seebauer and Winkler, 2020), the historical oppression of black and brown people and its implications for residents perceptions of retreat, land restoration, and group place attachment receives little attention (Phillips et al., 2012; Lieberknecht and Mueller, 2023).

Land in North America’s floodplains often remains vacant after retreat (Zavar and Hagelman, 2016) despite government-led buyout programs promising floodplain restoration. Maintenance costs and land use requirements often get in the way of restoration (BenDor et al., 2020). When restoration is considered, this typically happens through the language of ecosystem services, stressing that land in floodplains be restored to its ecological functions (Baker, 2004; Gourevitch et al., 2020; Worley et al., 2023). More recently some scholars argued that buyout processes need to recognize and invest in socio-ecological relationships for residents who either remain or relocate (Dascher et al., 2023; Shi et al., 2023). Only focusing on ecological and hydrological functions neglects the experiences that people have with their surroundings, and how histories of devalued urban black and brown life (Barron, 2017; Pulido, 2017) influence these experiences. Centering these issues within managed retreat processes can reflect a concern for both human and ecological health that may lead to more just retreat and post-buyout land restoration.

Furthermore, staying in place often means being still exposed to flood risk, which is dynamic and uneven (Collins et al., 2018; Herreros-cantis, 2020). Determinants of social vulnerability, such as income, age, and sex, intersect with pre-existing contextual justice (McDermott et al., 2013) relationships of class and racial (dis)advantage, which leads to higher flood vulnerability for black and brown communities (Bautista et al., 2015; Maldonado et al., 2016; Bakkensen and Ma, 2020). For instance, in NYC people living in flood risk zones are older, predominantly renters and of black and brown descent compared to the city average (Dixon, 2013). Pre-existing contextual injustices are the result of institutional actions and policies that over time have systematically undermined the wellbeing and ability to thrive of black and brown communities by reducing opportunities for intergenerational equity (Elliott and Pais, 2006; Chen, 2021). Lesser intergenerational equity can affect the ability to meet rising insurance costs (O’Connor, 2023) and to find a comparable property when accepting a buyout (Greer and Binder Brokkop, 2017).

Here, we advance an intersectional and thick framing of equity in land restoration as an important, but often overlooked process, in managed retreat in already disenfranchised coastal neighborhoods. Empirically investigating the grounded understandings and relationalities of recognitional, distributive and contextual justice, we argue for a historically and racially sensitive approach to climate adaptation broadly and managed retreat in particular. We examine the case study of Edgemere in Queens, New York City, centering everyday black and brown residents’ experiences of remaining in place, despite the combined threats of flooding events, floodplain development, and future retreat. This study accounts for the racial ecologies of housing and urban development that continue to shape many urban low-lying coastal neighborhoods in the United States (Hardy et al., 2017; Paganini 2019; Moga, 2020).

Edgemere is a predominantly black and brown neighborhood of the Rockaway Peninsula (Queens, NYC) where decades of neighborhood disinvestment, institutional racism, and failed urban renewal generated large amounts of vacant land and mistrust in government institutions. Racial linked housing practices included redlining and blockbusting (see 6.1). Following Superstorm Sandy in 2012, the city planned and implemented 7 property buyouts, adding more vacant land to the existing (see 3.1), as well as prohibiting and/or limiting new developments on lots within a new established Hazard Mitigation Zone (HMZ). We review how contextual, and distributive equity can aid in understanding disinvested neighborhoods facing managed retreat and characterize the need for focusing on recognitional equity as the expression of senses of justice or how residents subjectively perceive, evaluate, and narrate their positions vis-a-vis managed retreat and land restoration in the context of their neighborhood. Then, we provide a background to Edgemere’s flood vulnerability and current adaptation programs and methods to elicit residents’ perceptions. We address how city agencies justify the production of more housing in Edgemere despite ongoing vulnerability, counterposing this to residents’ views of housing and vacant land and examining feelings of misrecognition (disrespect, neighborhood stigma and betrayal) as well as relationships to place and belonging. We illustrate how these feelings are rooted in the material socio-economic harms brought by present and past histories of racial dispossession in the Rockaway Peninsula. Finally, we discuss how a senses of justice approach and the relationality that exists between recognitional equity, distributive equity and contextual justice can inform more equitable post-buyout land restoration.

2 Dimensions of justice in the aftermath of managed retreat

In this section we lay out the theoretical embedding of our case study work. While typically justice and equity are used mostly synonymously (Walker et al., 2024), when we use the word equity, we mean it as a principle of justice, a normative criterion for the implementation of justice (Grasso, 2007). We keep the main focus on the processes leading to injustices, their sources of material and symbolic harms and their subjects (see 2.2.2). We begin by introducing contextual justice and its importance in disinvested neighborhoods, subsequently highlighting the equity implications for those who stay in post-buyout neighborhoods and how these lead to issues of recognitional justice. Finally, we propose understanding recognitional justice through the lens of senses of justice, to bring forth the way black and brown people understand environmental interventions and broader neighborhood needs.

2.1 Contextual justice

Climate adaptation plans frequently direct post-disaster investments toward “resilient” housing, infrastructure, and public spaces, yet are frequently driven by neoliberal capitalist agendas lacking a nuanced comprehension of the entangled nature of equity, adaptation, and climate vulnerability (Karki, 2021; Camponeschi, 2023). Environmental justice scholarship however insists on the importance of three interacting dimensions of justice in evaluating resilience plans: recognitional justice (the well-being, knowledge and perspectives of affected groups), procedural justice (the meaningful inclusion of affected groups in decision-making), and distributive justice (the distribution of costs, risk and benefits; Schlosberg, 2002). Because of their interaction, recognition for marginalized groups may be limited or enhanced by the way procedural concerns are negotiated (Harris et al., 2017) while greater participatory equality may enhance chances for equity or distributive justice (Fraser, 1995; Schlosberg, 2003). Few studies actually tease out how these relationships work in practice (Walker, 2023) and how they can be traced to differential valuation of land rooted into ongoing processes of racial dispossession in the US coast (Hardy et al., 2017; Paganini 2019; Lamb, 2020). Rather than treating vulnerability as something attached to individual characteristics, we seek an approach that is attentive to the “historical and multi-causal production of harms” (Ranganathan and Bratman, 2021, p. 132).

In this vein, the 2019 NYC Panel on Climate Change acknowledged that dimensions of justice must be understood within the context of the culture in question and defined contextual equity as the pre-existing socio-economic conditions and the “root causes” of social vulnerability (Foster et al., 2019). In this paper we move the focus to contextual justice as the underlying socio-political processes and urban development patterns shaped by racism, classism, power and privilege, that create zones of neighborhood disadvantage and prosperity (Van Zandt, 2012; Hendricks and Van Zandt, 2021). Examples include policies promoting segregation, redlining, blockbusting, and planned shrinkage (Aalbers, 2014) as well as urban renewal plans of the 1960s and 1970s (Pritchett, 2003) resulting in excess vacant land (Pagano and Bowman, 2000) and built environments in disrepair. To some extent, the segregation of certain populations in urban low-lying areas is the product of patterns of neighborhood investment and disinvestment (Gerken, 2023).

In NYC, almost half of today’s urban renewal programs are located in prior redlined areas (Winkler, 2017), and across the US buyouts are more likely to happen in communities that experienced white flight and redlining (Loughran and Elliott, 2022). Targeted buyouts can then be used to invest in historically underserved neighborhoods (Wolch et al., 2014), where relatively poorly maintained housing stock in predominantly black and brown communities frequently qualifies as ‘substantially damaged’ under FEMA buyout programs (Siders, 2019). In low-income and marginalized neighborhoods, however, residents may have less ability to participate in or push back against buyouts (Lynn, 2017; Schumann et al., 2021) when they are undesired. The option of retreat can be rejected based on deep seated government distrust (Ajibade, 2019) and can be seen as an outright threat to black and brown livelihoods (Doberstein et al., 2020). In some cases, faced with increasing flooding impacts, some people may feel they are being betrayed by agencies that are supposed to protect them and fail to do so (Askland and Bunn, 2018).

2.2 Equity in post-buyout neighborhoods and the importance of recognition

The process of buying out properties can lead to several distributive inequities for those who decide to stay (Kraan et al., 2021). First, the decision to leave a place is almost never a consideration people take lightly, but motivated by fears of living in a disaster zone, including losing insurance or witnessing the dissolution of their community (Baker C. K. et al., 2018; Koslov, 2021). Those who stay, may similarly not do so out of will but rather out of the inability to do otherwise (de Vries and Fraser, 2012; Cardwell, 2021). Moreover, since the property is given priority in the retreat process, what happens to the land once the property is demolished remains entirely in the hands of local governments. Studies investigating land restoration dynamics following retreat are scant, but existing research suggests most land following retreat remains vacant (Zavar and Hagelman, 2016) because maintenance is rarely part of a retreat program. For instance, if a post-buyout land use plan is not made part of flood mitigation management, this can lead to distributional inequities due to suboptimal use of space (Zavar, 2015). People may feel their social environment is deteriorating when parcels are left vacant (Seebauer and Winkler, 2020) because either land regulations require so, or because the social and ecological values of vacant land are not acknowledged by planners (Anderson and Minor, 2017; Atoba et al., 2020). In addition, urban vacant land’s association with blight, crime, and illegality can generate neighborhood stigma and negative feelings leading to health impacts (Garvin et al., 2013). Considering how those who stay behind feel about their changing neighborhood and their viewpoints on post-buyout land re-use becomes a crucial recognitional justice issue that deserves attention by adaptation scholars and policy makers alike.

2.2.1 Recognition in climate adaptation

Recognition is a relatively understudied issue in urban climate adaptation and resilience compared to procedural (Hill, 2008; Holland, 2017; Rudge, 2021) and distributional dimensions of justice (Collins et al., 2018; O’Hare and White, 2018; Ashley et al., 2020). More broadly, less than 5% of studies on equity and justice in adaptation do empirical work and even fewer address recognition implicitly or explicitly. Of the articles included in the systematic review (68 out of 1,391) investigated justice or equity empirically (Coggins et al., 2021). This study aims at meeting both the need for more attention to empirical evaluations of recognitional justice but also its relationality to the occurrence overtime of distributive and contextual injustices.

Recognitional justice consists of symbolic elements related to whether individuals or groups are treated with respect (Honneth, 1995) as well as material inequities related to the uneven distribution of risks and benefits (Fraser, 1995). In post-disaster landscapes recognitional justice is often at the mercy of state and non-state agencies who get the liberty “to define the affected community’s lifeworld” (Joseph et al., 2021, p. 10) without understanding how risk and recovery are actually embedded into everyday life. Misrecognition in climate adaptation is expressed through “racialized exclusion” from decision making process that focuses on professional and educational affiliations instead of community groups’ voices that advance self-determination (Grove et al., 2020). Some climate adaptation literature approaches recognition by assessing plans and strategies to understand whether they include relationships of power, contexts, vulnerabilities, knowledge, narratives (Preston and Carr, 2018; Meerow et al., 2019). Others, empirically show whether and how residents’ participation in resilience and adaptation visioning and plans accommodates for difference, while accounting for past injustices influencing current conditions of vulnerability (Grove et al., 2020; Joseph et al., 2021). The term “color blind adaptation” refers to plans and policies proposing one-size-fit-all adaptation or resilience strategies that ignore certain groups’ perspectives, knowledge, and ways of life; and bypass claims of suffering (Haldemann, 2008) and the burden of race-linked housing, planning, and health practices (Maantay, 2002; Paganini 2019; Lamb, 2020). In the interest of seeking a grounded approach to aspects of recognition, researchers should not just represent the interests of marginalized groups but investigate how these are expressed by and within marginalized groups themselves (Svarstad and Benjaminsen, 2020).

2.2.2 Grounding recognition through senses of justice

Svarstad & Benjaminsen coined the term senses of justice as the “ways in which affected people subjectively perceive, evaluate and narrate an issue, such as their perspectives on an environmental intervention” (2020:4). Senses of justice is a way of putting in the spotlight the lived experiences and knowledge of groups whose framing of normative ideas about justice is overshadowed by those of more resourced and powerful actors (i.e., project funders; Massarella et al., 2020). Moreover, variations within communities in what recognitional justice criteria matter for implementing environmental policies are common. Differences stem from whether recognitional justice is discussed at individual or community level, the type of overseeing institution, and people’s different roles and activities (Lecuyer et al., 2018). Overall, these studies underline the need for more nuanced and localized understandings of recognitional justice. Senses of justice is empirically evinced through residents’ narrations of subjects, harms and processes (Martin et al., 2016). Subjects have to do with who holds moral rights and is deserving of political attention, whether individuals or communities, present or future generations and non-human species. Subjects can also shed light on place attachments or the affective bond between people and places (Manzo and Perkins, 2006), where social relations and nature interact with the meanings, we give to various elements of place to produce everyday experiences of place (Burley et al., 2007). Harms are the kinds of inequities suffered by subjects, and they can be eminently material resulting from distributive inequities, or symbolic, caused by personal injuries to one’s self-esteem or a group’s identity and culture. Processes are the structural explanations for both distributive and recognitional inequities. This tripartite formulation seems particularly useful to engage with the relationality that exists between recognition (subjects), distributional (material harms) and contextual dimensions (processes) of justice. Here we use senses of justice to investigate how neighborhood residents perceive vacant land and how they would like to see it repurposed, as a springboard to discuss broader issues about present, past, and future flood risk and urban development in their neighborhood.

3 Methods

We use an in depth case study approach to study senses of justice after managed retreat. In-depth interviews were conducted to understand residents’ senses of justice after retreat on the one hand, and city officials’ perspectives on retreat on the other. The first author spent several months in the neighborhood volunteering for a community garden and a grassroots organization, which allowed for recruiting possible interviewees (see Supplementary materials). Document analysis of contemporary and historical zoning and planning documents provided insight into relevant dynamics. Neighborhood walks and a vacant land survey were used to identify lot conditions.

3.1 Study area

Toward the end of a long subway ride starting in dense and bustling Brooklyn and crossing Jamaica Bay, the Rockaway shoreline appears. As the train arrives at Beach 44th Street, Edgemere’s stop, there are no cafés and stores to greet you, but the sea view is still unencumbered by new development. The neighborhood of Edgemere is on the Rockaway peninsula of Queens (Figure 1) and has a population of 8,885 people (ACS, 2015–2019). Edgemere is a diverse and majority-minority low-lying waterfront neighborhood, where 59.4% of the population is African American, 35% is Hispanic, 26% is Caucasian, 2% Asian, and 12% are other races. During Superstorm Sandy (2012), flood depths of over six feet were recorded along the shoreline, while homes and infrastructures were destroyed, leaving thousands without heat, electricity, and/or with water damage leading to mold in their homes (Moore, 2014). The vulnerability of Edgemere’s population is nuanced. American Community Services (ACS) estimates for 2015–2019 show that vulnerable categories like elderly living alone (88%), female headed households (70%) and renters (80%) are high here and that there are significant increase in low to moderate income people suffering from rent burden (from 13 to 49%) compared to pre Sandy estimates (2008–2012). There are significant reductions in households living with people with disabilities (from 70 to 50%) as well as in owner occupancy (from 17 to 11%).

Many recovery programs were launched in the area, including the 2015 Resilient Edgemere Community Planning Initiative (RECPI). This multi-agency effort aimed to reduce flood risk, help with disaster recovery and bring infrastructural, housing and retail developments that 19 years of active Urban Renewal Area (URA) had not been able to deliver (see 6.1). The RECPI instituted the Edgemere Resilient Plan Area (see Supplementary materials) that through the Build it Back program channeled funds for property buyouts and acquisitions. The RECPI also introduced several zoning changes aimed at eliminating or limiting housing developments along a hazard mitigation area. For instance, the RECPI designated 119 vacant city-owned lots, which include 7 buyout and acquisition lots, to be managed by a Community Land Trust (CLT) as well as mixed-use housing developments (see 4.1 in this paper and Supplementary materials).

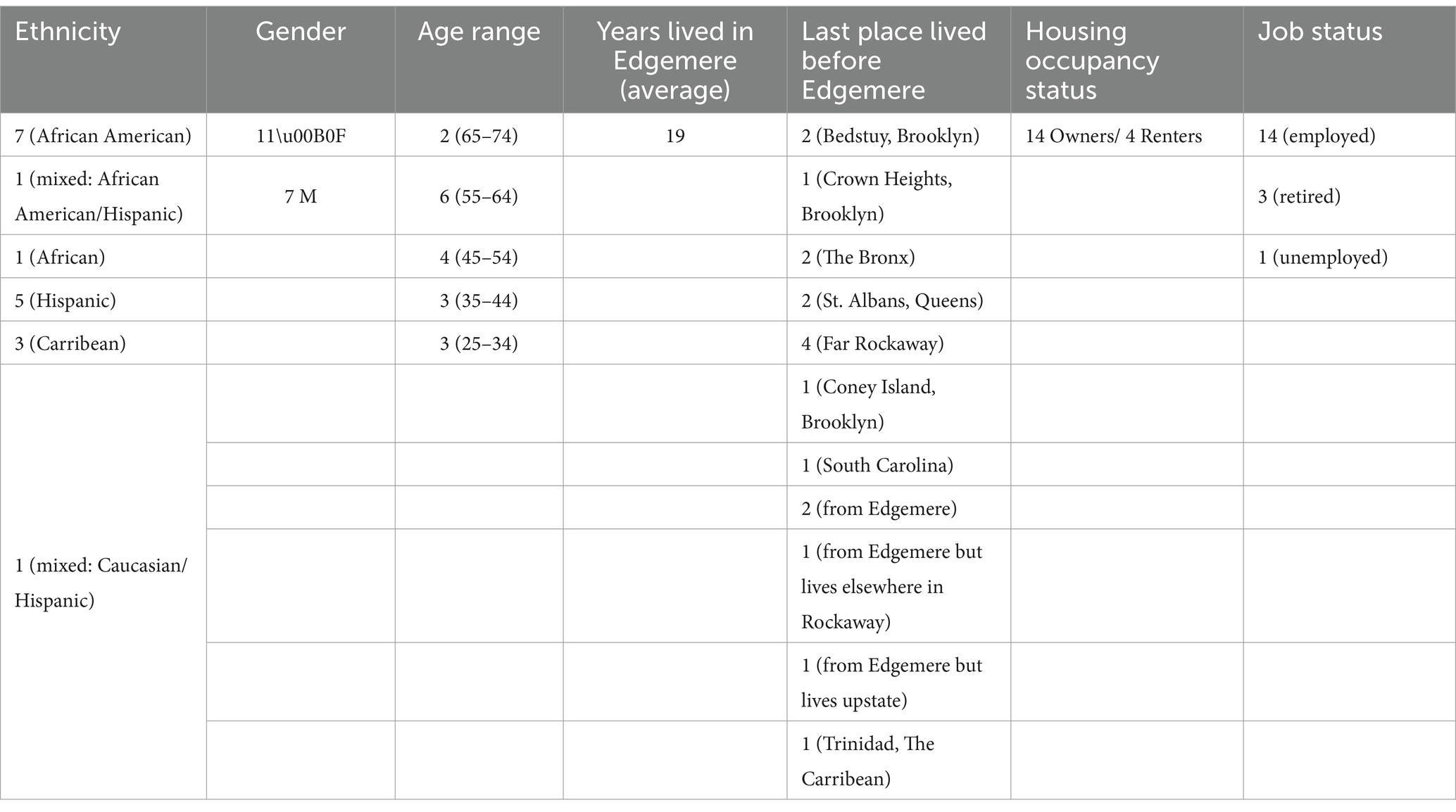

3.2 Qualitative interviews: rationale, recruitment, analysis

Between May 2021 and September 2022, the lead author maintained a continued engagement with the neighborhood of Edgemere by volunteering in two places: one community-based organization (CBO) and one local community garden. The lead author helped the CBO conduct land parcel surveys, lots mapping, and community outreach for land visioning workshops (see last paragraph), in exchange for being able to observe the workshops. The CBO and the garden provided opportunities to meet residents to be interviewed. Focusing on people’s accounts of living in their neighborhood, these interviews serve as a process of alternative knowledge production, which can fulfill affirmative politics of recognition (Barron, 2017). By talking to people about their personal feelings, opinions, and experiences, the interviews elicited past and lived experiences of recovering in the wake of Sandy and elevated people’s personal accounts of living with vacant land in a post-buyout and disinvested neighborhood (see Supplementary materials for interview protocol). Interviewees were representative of Queens in terms of their diversity, largely female and in adult age. As is typical of the Rockaways, all interviewees except four came from elsewhere in the city or other states and countries. Most were homeowners and employed at the time of the interview (Table 1). The 18 in-depth interviews were recorded and transcribed using a combination of AI powered software and manual corrections in MaxQDA. Keeping anonymity in mind, all interviewees’ names were changed to fictional names. Subsequently, we use a modified iterative four stage approach for coding analysis inspired by Lecuyer et al. (2018) who studied feelings of justice in conservation management (see Supplementary materials).

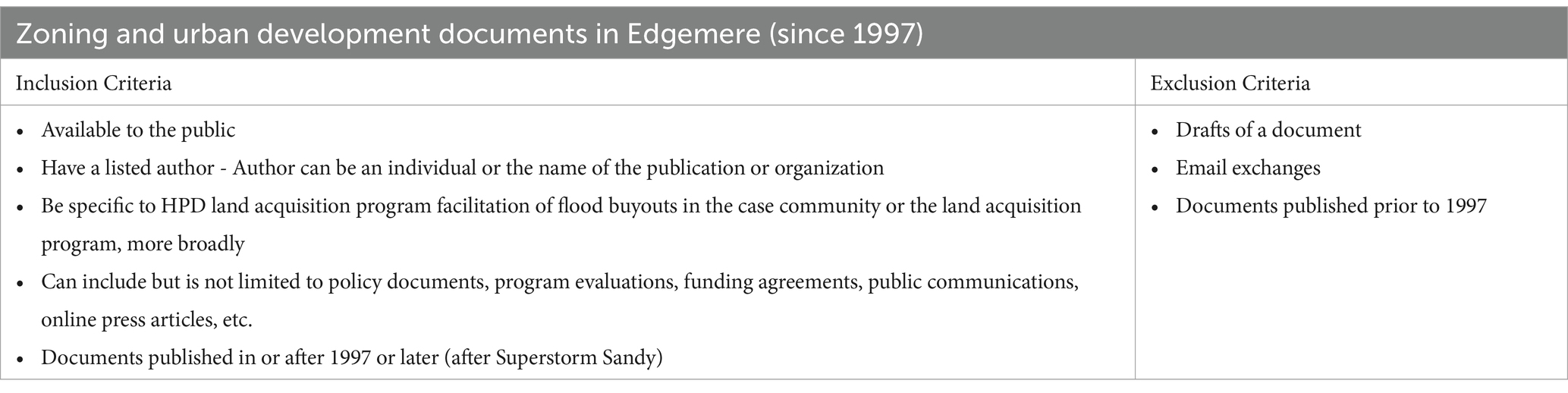

Furthermore, four semi-structured interviews with staff from the NY Housing Preservation and Development (HPD) (3) and the Mayor’s Office of Resilience (MOR) (1) were key to understanding perspectives on urban development, climate adaptation, and retreat in Edgemere and New York City. Finally, in 2023 an analysis of all the online publicly available documents was conducted, describing the zoning changes and urban development project documents in Edgemere since 1997, the date of the Urban Renewal Area was established. It utilized search engines as well as specific searches on official NYC portals (Table 2).

Between November 2021 and March 2022 three community visioning workshops were held in Edgemere as a first step toward a resident-led definition of possible land restoration actions (see Olivotto, 2024). Residents interviewed for this study offered insights that were mostly aligned with the outcomes of the workshops and added a more nuanced understanding of the importance of engaging residents living adjacent or in front of a vacant lot.

4 The present and future of Edgemere’s vacant land

In the following we illustrate city plans for building new housing on existing vacant land in Edgemere and reflect on its implications for flood risk and affordability for current residents. We contrast this with the position of some residents and community board vis-a-vis the developments, accompanied by our observations of the status of buyout lots and related residents’ perceptions and wishes for vacant land use.

4.1 Fighting the housing crisis, building out the floodplain

City and federal authorities used “a novel kind of angle” (MOR, Pos. 42) to deal with the simultaneous challenges of coastal flood risk, neighborhood disinvestment, and housing shortage in Edgemere. From their perspective, the RECPI provides a long-term land use strategy that aims to freeze development on city-owned land in areas beyond FEMA’s line of wave action, while allowing for waterfront recreational activities and areas of limited development. Amid a citywide housing crisis fueled by a combination of opposition to and restriction of affordable housing construction (Morris, 2021), the RECPI recognizes Rockaway and Edgemere as “the last bastions of affordable home ownership opportunities” as a member of the Mayor’s Office of Resilience put it (MOR, Pos. 69). This other quote by a former Housing Preservation and Development (HPD) officer summarizes the dilemma:

“There are parts of New York City that get tidal flooding. There's a little bit of it in Edgemere, but [elsewhere], it's truly a daily problem. You shouldn't be building a new multifamily building in Broad Channel. But that's a different question than what to do with tidal flood risk that's not starting in 2030 but coming sooner. How do you manage that disruption and that preparation? How do you create an out valve, so there's housing somewhere else. Right now, there's no housing anywhere. So like, you can't disassociate those things. If you say, we're not gonna do anything in the Rockaways, we're not going to build housing. Well, that was not serving anyone there. Like no one was happy with that solution. That disinvestment begets further racism and disinvestment.” (Former HPD Officer, Pos. 68).

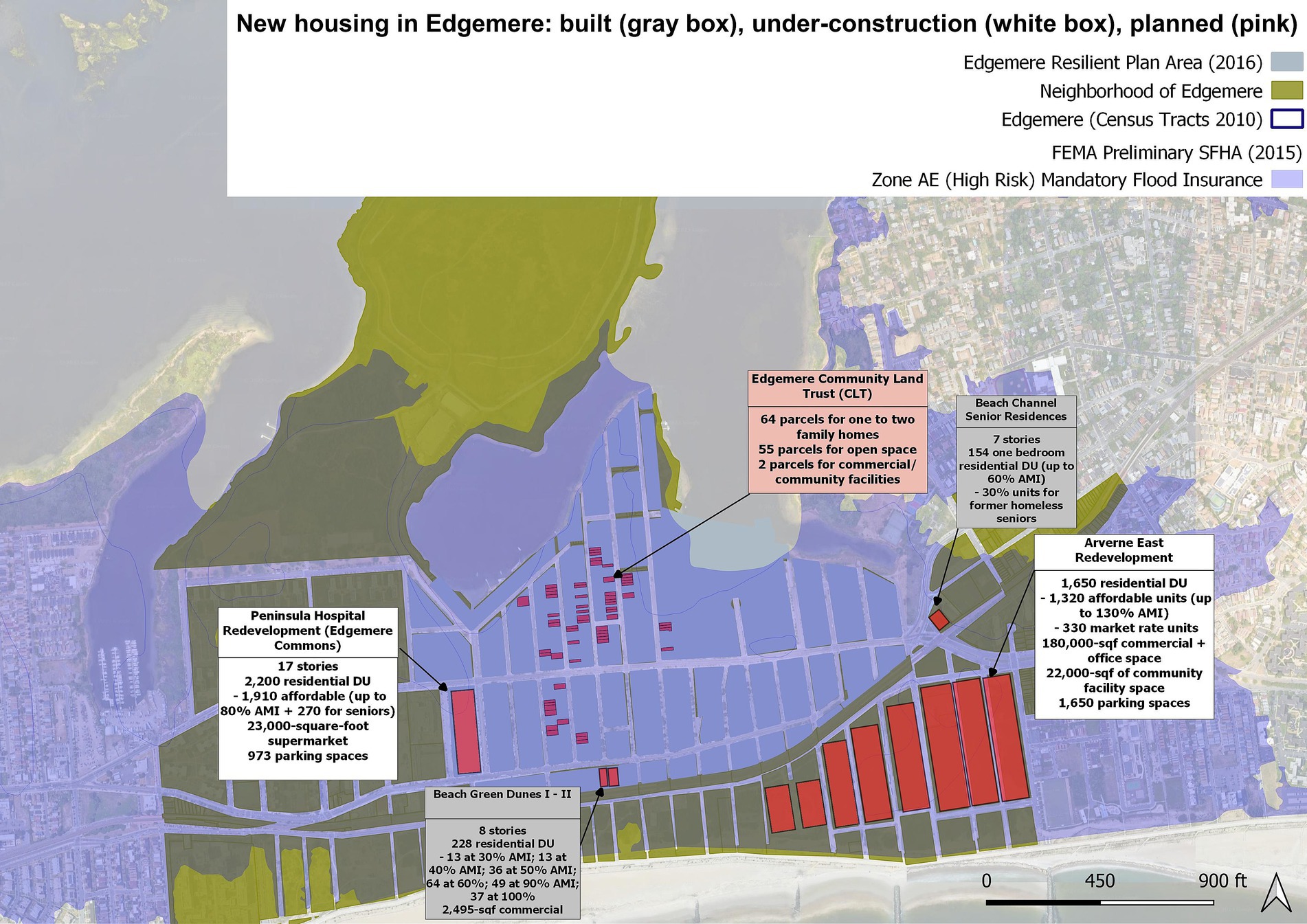

That one of the most low-lying areas in New York City, should be touted as the last remaining place for affordable housing is astounding and points to the ongoing double jeopardy—the double threat of gentrification and flood risk—occurring in many New York City coastline neighborhoods (Herreros-cantis, 2020). The former officer explained that building high rises here would be a way to improve building quality and provide Edgemere’s predominantly renter population living in one-and-two story homes, the option to live in an elevated building where water damage will not affect their apartments. But when fully built, the REPCI will bring 1,201 residential units (approximately 38% as affordable housing) and almost 150,000 square feet of retail space, and as many as 549 new parking spaces (City of New York, 2020). This plan stoked fears of gentrification among residents and was voted against by the local community board (see 4.2).

Much of the housing slated to be built under the REPCI is not affordable either. Figure 2 below shows all the residential units currently under construction as part of the RECPI as well as the Arverne East development. It is hard to get precise rates of affordable housing in relation to Area Median Income (AMI), but the largest developments should range between 30 and 130% of AMI (REW, 2019). At this rate many of Edgemere’s extremely low-income renters (earning $33,625 for a family of three, ACS, 2015–2019) will not be able to afford the new developments. The only truly affordable option may be the CLT, which lawyers, activists and a few renters strongly advocated for during the formulation of the RECPI in 2015.

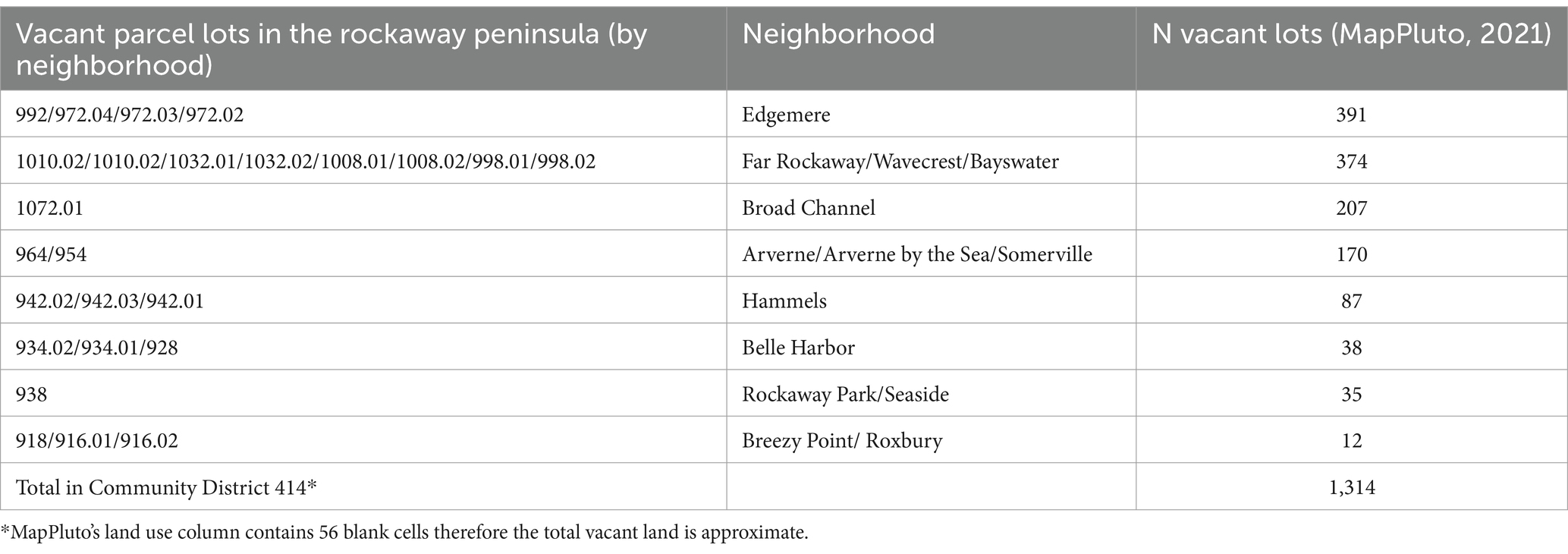

In the eyes of municipal officers, the construction of all this new housing in Edgemere is seemingly justified by the extent of its vacant land, itself a product of municipal disinvestment and housing foreclosure (see 6.1). According to NYC’s database MapPluto, the census tracts corresponding with Edgemere have the highest amount of vacant land in the Rockaway peninsula, 391 vacant parcels (Table 3). When this number is turned into square feet, 16% of Edgemere is occupied by vacant land (compared to a NYC average of 8%).

4.2 Residents’ views of housing and vacant land development

The municipal view of the future development of Edgemere is contrasted with the concerns voiced by residents through the local Community Board 14 as well as the actual desires for vacant land and larger neighborhood needs. In June 2022, the Community Board 14 presented a unanimous resolution imposing its rationale for a moratorium on all upzoning requests until an environmental impact study addresses concerns that new developments are not aligned with existing services and low density neighborhood character (Schwach, 2022b). While some residents questioned adding more housing to the floodplain “if the threat of flooding is real, why are you bringing more people to live here” (Ana, Pos. 34), others also questioned the need for commercial space that does not serve the community. As Sara put it:

“When you have commercial space attached to a mixed use development the owner/landlord dictates what retail is going to come in, rather than thinking about the entire zip code. It's easier to rent out spaces with no residents, because if there were already residents, they'd be "well I don't want an Indian restaurant under my house”. I agree with the Community Board motion. [..] The thrift way and supermarket that was there are not coming back and these are the things we need.” (Sarah (part III), Pos. 12).

Sarah who was born in Edgemere, saw what the mixed-use housing development on neighboring Arverne East brought to the area, mainly commercial eateries that satisfy the surfer community in the Rockaway Peninsula and not the working class. Existing need for a proper number of school seats, transportation options, emergency routes, parking spots and medical service on the peninsula are compounded by the state of vacant land.

Vacant land surveys done on foot in July 2021 showed a patchwork of vacant land conditions. Some lots have been encroached upon by adjacent residents and used as parking spots (L7 Figure 3) or garden extensions; others have overgrown vegetation (L707-79 in Figure 3); yet others are fenced with a “no trespassing” sign from HPD, who owns most of the vacant land in Edgemere. To date, as per NYC’s tax lot database, 4 buyouts and 3 acquisitions were completed in Edgemere and they are all still vacant (L59, L94, L92, L14, L42, L37, L34 in Figure 2). As of September 2022, 6 of the 7 buyout and acquisition lots are property of HPD and are fenced off. Two have still undemolished structures on them, some with vegetation but mowed, and one is unfenced and bushy. One more, at the tip of the bay, is asphalted and its ownership transferred to the Department of Parks and Recreation in June 2022.

Most interviewees who mentioned their concerns for vacant land surrounding their homes felt it was neglected (9/18) or expressed feelings of unsafety (3/18). Among residents who perceived neglect the majority had concerns about infestation by city rodents or poison ivy (9/9), while others had concerns about uncollected trash (3/9) and tall grasses and bushes (2/9). The only positive perceptions of vacant land came from two interviewees who recollected their childhoods in Edgemere. Alvin recalled how there “was always something to explore, whether it was out in the Bay Area or the beach area or, you know, the open land itself made for wonderful opportunities to become playing fields” (Alvin, Pos. 54). Three interviewees manifested the need for an option to purchase the vacant lot next door with the intention to use it as a vegetable or ornamental garden or simply to have direct control over how often it is mowed. They cited concerns about nuisance and noise should these lots be repurposed for residential or open public space. Vacant land purchasing programs tend to significantly improve the condition and care of lots (Santo et al., 2016; Gobster et al., 2020) but purchasing options are only created if an institution such as a City Land Bank is established to acquire, catalog, and transfer title deeds.

The majority of residents (10/18) expressed the desire for recreational land uses. For instance, mentioning children compatible uses (such as playgrounds) but also a place to store kayaks and fishing infrastructure. These desires are in line with the contextual observation and anecdotal evidence collected while walking the streets of Edgemere. For instance, it is not unusual to see make-shift basketball scores equipment next to curbsides, as well as for parents turning their backyards into spaces for their kids and their neighbors’ kids to play safely. This underscores a need that is not met by public infrastructure. Along with the rest of Rockaway, Edgemere is known for its fishing scene, especially for striped bass. Local resident fishermen as well as fishermen coming from other parts of Rockaway and NYC, frequent Edgemere’s north shoreline. Yet there’s no equipment to facilitate this activity, such as benches or wood canopies to provide shade. This microcosm of concerns and wishes for vacant land underlies some of the material neglect that this neighborhood has been subjected to for at least two decades and should be framed within a broader set of feelings of misrecognition that fuel institutional distrust.

5 Feelings of misrecognition: recognitional justice as senses of justice

Recognitional injustices in Edgemere manifest through feelings of misrecognition, specifically the feeling of being disrespected as a community (mentioned by 7/18 interviewees), through outsiders’ perceptions of their neighborhood (mentioned by 6/18), and as betrayal by government authorities (mentioned by 4/18).

5.1 Group disrespect

Residents mentioned the feeling of community disrespect in relation to perceived differential treatment by institutions on several development decisions relating to the city’s housing crisis as well as human/nature conflict in ecological preservation. A telling example of the experience of group disrespect is captured by the issue around La Quinta hotel on Beach 44th street. Only 1 year after the hotel’s opening in 2016, the Department of Homeless Services (DHS) informed locals that half the rooms would be used to house homeless women with children who are victims of domestic abuse; despite the De Blasio administration’s expressed ambition to scale back on the use of commercial hotels for such purposes. A mere 5 years later, the hotel was to transition once more into an all men shelter hosting former prison inmates. Anticipation of these kinds of changes made residents protest the proposed hotel construction already back in 2012 (Shain, 2020). These forced changes were seen as a sign of disrespect rooted in systemic racism. As Lorraine put it:

“This city is so disrespectful to minority communities. It’s unbelievable. I mean, again, I do not want to portray these men as the boogeyman, but we also have a right to be safe. We also have a right to know who’s in our community, especially coming through the shelter system.” (Lorraine, Pos. 43).

While residents understand the necessary function that this hotel now performs for New York City, they are angered by the surreptitious way in which these decisions were made: “Our community board district manager got an email from a Department of Homeless Services person, she sent the email from her iPhone! Her iPhone! No community meetings, no public meetings, no regards to us as a community.” (Lorraine, Pos. 43) Unlike other types of locally unwanted land uses (LULUs; Popper, 1983) such as mental health hospitals, hotel rooms turned to shelters maintain a certain façade of being good for the community while bringing the same assumptions of nuisance and negative externalities.

Residents believe their community of Edgemere, and more broadly Eastern Rockaway, is disproportionately targeted as a place to host homeless shelters, because it is predominantly a community of color. This ties into feelings of being treated differently from the Western portion of the peninsula. As Lorraine voiced: “you would have never done that to the West and you would never done that to Rockaway Park, Belle Harbor, Breezy Point, Howard Beach. They would have never detected the disrespect that they have shown this community.” (Lorraine 17, Pos. 47). The heaviest burden of sheltering the homeless normally falls on neighborhoods that are predominantly black and brown and with high rates of poverty, and the Rockaway Peninsula is no exception to this (Smith and Bhat, 2022).

Community level disrespect is also experienced by homeowners who perceive their neighborhood is disproportionately a target for lower-income people depending on Housing Choice Vouchers (HCV) such as CityFHEPS, a rental assistance supplement program, associated with documented challenges (Tegeler, 2020). Landlord discrimination against accommodating HCV families in well-off neighborhoods is widespread (Cunningham, 2018) leading to economic and racial segregation in poorer areas like Edgemere and fueling neighborhood divisions (Graham et al., 2016). As Alvin explained:

“But one of the benefits of CityFHEPS for a lot of folks is that if you have a vacant home and if it passes CityFHEPS inspection, you could actually get four months advance payment of rent. So, you know, it’s $11,000 that the city pays you upfront to get the home. So, you are getting paid that much more in advance. One of the benefits for a lot of slumlords is anytime they have a new family through CityFHEPS, you are getting that money coming in. And if they leave in a year, it does not matter. You put in for more CityFHEPS, you get new tenants. That’s an additional bonus.” (Alvin, Pos. 210).

There are also perceived ecological injustices in Edgemere. Two meaningful examples are the interrupted access to Edgemere’s closest beach point from mid-May to August to safeguard the piping plovers nesting grounds and the fight over including evening lighting in a newly built 35-acre nature preserve. The Edgemere Community Civic Action (ECCA), a coalition of homeowners, led a petition in 2022 to reinstate access to the beach, calling it a form of environmental racism and of community neglect (Schwach, 2022a). ECCA also fought the real estate developer’s decision to exclude lighting from the preserve, addressing it as an issue of wildlife versus human wellbeing issue:

“[.] is that fair to the people that live in this community? [..] What is more valuable? The lives of humans so that they can have adequate recreation.. because that nature preserve.. Yes, it is to protect bird life but what about human life? The community of Arverne and Edgemere is predominately people of color who are suffering from hypertension, diabetes, heart disease. What’s the problem of having bike trails and trails for people to be able to take that evening walk? How much inconvenience would that be for people to come in and say, you know what, we can make this more people friendly and maybe their lifestyles will change. Maybe they’d be more inclined to get out and exercise.” (Lorraine, Pos. 61).

Eventually lighting was added but only along one path cutting across the preserve leaving much of it in the dark after sunset (Dunning, 2022). The nature preserve, like the conservation area for piping plovers, emphasizes white ideals of nature, such as vegetation and non-provisioning green spaces that do not include recreational spaces valued by black and brown communities and cultures (Mullenbach et al., 2022). Preserving wildlife and ecological features without meaningfully addressing decades of injustices will only amount to more injustice in the minds of those who are oppressed.

5.2 Neighborhood reputation

Residents mentioned the issue of neighborhood reputation as a matter of recognitional justice, referring to three geographical layers of “bad” reputation: how neighbors from Long Island perceive Queens, how outsiders perceive Rockaway’s past, and how other residents of the Rockaway peninsula perceive Edgemere.

Darren, who attended community board meetings in Long Island said referring to how the members would react to a developer’s proposal to increase density “and without fail before that meeting ends, somebody is going to say, we do not want our community to become like Queens. That’s a code word for a lot of things. You do not want to become like Queens, you know, that’s code word for density, that’s code word for traffic, that’s code word for diversity, that’s code word for public housing, poverty. Every fear that drove people out to Long Island in the first place.” [Darren (part II), Pos. 136–138].

Darren also referred to Rockaway’s boom and bust history, when around the 1950s the summer bungalows and hotels for white middle-class New Yorkers were repurposed for migrants from the South and for low-income residents who were evicted from Manhattan by Moses’s slum clearance programs:

“You know, once it stopped being a vacation spot, it became a place where people did not want to move to. I remember in the nineties when I came to the U.S., the Rockaways had a terrible reputation. It was a place where people would get carjacked, it was poor, the robberies. So, people did not want to move here. And then over time a lot of immigrants settled in the United States, and wanted to purchase a house, Rockaway really became the only place where you could afford to buy a house.” [Darren 12 (part I), Pos. 47].

Neighborhood reputation, following (Otero et al., 2022, p. 22) can work “as a collective imaginary leading to a socially constructed stratification” influenced by the general perceptions held by outsiders to the neighborhood, peninsula and borough. Negative geographical reputation is a spatial inequality outcome of cultural inequalities, which can lead to very tangible loss of social opportunities (e.g., jobs) for less favored groups (Massey, 1990).

5.3 Betrayal

Unfulfilled promises over the span of several decades manifest in feelings of betrayal. These feelings are directed toward city authorities, in particular Housing Preservation and Development (HPD), the Department of Education (DOE), and the Department of Transportation (DOT). Following the first Edgemere Urban Renewal in 1997 and its amendments, which created homeownership opportunities for low-to middle-income families, these city agencies failed to bring services and infrastructure to the neighborhood (see 6.1). As Lorraine put it:

“And I get angry because I feel that if we bought our homes under a bait and switch, there was no support, infrastructure for the homeowner. They brought in moderate and middle income families where there was nothing. No new schools, no recreation centers, no shops. Even though this is what was promised to us. And the most disheartening thing that really bothers me, [..] when they did the reconstruction of the boardwalk, a $5.5 million dollar reconstruction [..] for the two miles where Edgemere lies, from Beach 32nd Street to Beach 59th Street, not one single thing came into the community. No bathrooms, no recreational activities, no concession stands. $126 million was left over from the reconstruction of the boardwalk, and they didn't see fit to put anything in.” (Lorraine, Pos. 17)

The bait and switch that Lorraine refers to are incentives that different real estate developers offered to teachers, nurses, and doctors to come live in the Rockaways. Half of our interviewees came from other neighborhoods of Queens, from the Bronx, and from Brooklyn because they could not find affordable homeownership opportunities that satisfied their needs. In Edgemere they found DOE signs advertising new schools, new parking spots under the A line, and new commercial opportunities. But none of it has materialized over the past 19 years, which is the average time my interviewees lived in Edgemere. What they found was less congested streets, less density, and homes with front yards and proximity to the sea.

Furthermore, Lorraine does not just voice disappointment at what was promised in the urban renewal area plan but also how little visible improvement occurred since the millions of dollars that poured into the Rockaway following Superstorm Sandy were spent in this neighborhood. Of the $120 million in FEMA funding left after the boardwalk reconstruction, the NYC Parks Department put out a call for spending preferences among nine projects initially conceived under the Rockaway Parks Conceptual Plan. Seven projects were approved and matched by $25 million from Queens Borough’s public and private entities: one project included in the RECPI, allocated $14 million to raise Edgemere’s bay shoreline and Rockaway Community Park (Rose, 2017) and another financed a new playground (The Wave, 2023). But only the latter was completed in 2020.

5.4 Subjects of recognitional justice and place attachments

A theme emerging from the interviews was how despite being neglected, Edgemere is a place where people enjoy living. Interviewees mentioned community strength resulting in mutual care, activism, and volunteerism. Although more strongly perceived in the months following Superstorm Sandy, some of the connections made through mutual care groups that sprang up then, are a source of encouragement to be an active community member still today. For instance, Ana said:

“Before the hurricane I was trying to be involved in different organizations but after the hurricane I stopped going to meetings and caring. My neighbor started a Civic Association for homeowners at that time, she really helped me during the hurricane and sometimes when we get discouraged today, we encourage each other to be more involved.” (Ana, Pos. 11).

Community gardening at local urban gardens such as the Garden by the Bay and Edgemere Farm, was also mentioned as a space for both individual and collective healing for African American and Latinx women as well as intergenerational and intercultural learning about caring and cooking with different vegetables. The Garden by the Bay is a community garden led by Lorraine and Mercedes founded by a group of black and brown women in 2013 with the help of the community land access advocacy organization 596 Acres. Today the garden is a place where mostly women and increasingly their children come to learn about practical gardening skills, seeds, harvest and eat together, celebrate festivities, tell personal stories and to discuss what’s happening in the neighborhood. Interactions with Edgemere’s open spaces stimulated many positive feelings, especially proximity to the bay’s water and its recreational opportunities, such as fishing, crabbing and sports like jet skiing, as well as the sight and sound of water. Access to two parks to the East (Bayswater Park) and West (Rockaway Community Park) of the neighborhood was mentioned less, probably because either park is further than a 10 min walk from Edgemere’s central streets and accessibility to one of them (Bayswater Park) was only improved in 2020.

Renters’ voices are not adequately represented in this study, but one of them mentioned something crucial for the future of managed retreat policy in this neighborhood. Elizabeth lives in a small apartment with two children and her husband and has been relying on rental assistance to get by. She recognized her ancestors who suffered from generational trauma and for whom the weight of generational homelessness is a daily fight and her goal of homeownership is to honor her grandmother who fought to get into a NYCHA apartment. The trauma of generational homelessness was also paired with the need for affordable housing that can be handed down to their kids for wealth building. Studies suggest that especially among black and brown people, buying a home represents a marker of their success and achievement (McCabe, 2018) because it addresses the issue of equalizing homeownership and reducing the racial wealth gap (Baker J., 2018). But in a community of renters with a history of disinvestment generating recognitional inequities like Edgemere, homeownership may be interpreted more as a sign of stable tenure and belonging in the context of anti-blackness and brownness and racial capitalism (Woods, 2002; Pulido and De Lara, 2018).

For this reason, when achieved, homeownership becomes a source of place attachment (Oh, 2004). Place attachment is an affective bond between people and places (Manzo and Perkins, 2006) where social relations and nature interact with the meanings we give to various elements of place to produce everyday experiences of place (Burley et al., 2007). Dawn and Randall, who own a waterfront property, said they’d never give up the privacy of their water-facing patio, and that they felt particularly connected to the views and the fresh air. They migrated from the Caribbean islands and found in Edgemere’s bay a place that reminded them of home. Others took pride in having a yard where they could garden or host friends and neighbors’ children. Ten out of eighteen interviewees moved to Edgemere around 2007, and this created a feeling of belonging around first time homeownership. As Mercedes said:

“We were all coming together because this was our first time owning a home, and we shared phone numbers. Whoever had a cookout, a party, we got invited. So, this felt, you know, like a real community.” (Mercedes, Pos. 43).

Although homeowners are a minority in Edgemere, their voices speak the loudest. The Edgemere Community Civic Action (ECCA) consistently lobbies with the city council about several of the environmental, flooding and services inequities. ECCA is a crucial counterpoint to a history of organizations, like the Rockaway Council of Civic Associations and the Rockaway Chamber of Commerce, that back in the 1960s predominantly represented the interests of white homeowners organizations, advocating for market-rate housing (Kaplan and Kaplan, 2003).

6 Contextual justice: the processes and material harms underlying recognitional justice

Feelings of misrecognition presented in section 5 are the result of material harms that can be contextualized within the history of Edgemere’s urban planning and broader forces shaping housing production in Rockaway and NYC. These processes represent structural explanations for distributional and recognitional harms.

6.1 Urban disinvestment: failed urban renewal and unfulfilled promises

Edgemere’s history cannot be disentangled from that of human intervention and control over streams, inlets, sands, currents, sediments and fauna of the Rockaways. Several development processes made Edgemere ultimately vulnerable to flooding: indigenous land expropriation (The Rockaway Review, 1948), land filling of surrounding marshlands due to a booming real estate market (Dawson, 2017), hosting the largest city landfill (1938–1981) now a superfund site, and delayed extension of the sewer and drainage system and road pavement. Despite investments in sewer and drainage infrastructure in 1997 and 2019, Edgemere still suffers from blue sky flooding today. These floods occur around old creeks that were built over, but still contribute to high groundwater and ponding in this area. This history of ecological overhaul and environmental degradation is important to consider in parallel with uneven disinvestment and disenfranchisement of Rockaway rooted in racial linked housing and planning discrimination.

Following WWII, a wave of migration to NYC put pressure on the housing supply across the city. In the 1950s, the City Planning Commission (CPC) approved a Master Plan identifying new areas for slum clearance and redevelopment, the latter especially low-rent housing in Rockaway, which had plenty of vacant and cheap land. Meanwhile, in the late 1930s exclusionary housing policies, such as redlining, enacted by the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) had assigned a C (or: hazardous conditions) to most of the east side of the Rockaway Peninsula. Black and brown people had to pay higher mortgage rates for homes in Rockaway and had difficulties (re)financing them (Taylor, 2019). These same banks received local deposits and invested them outside of the community, draining its economic base. In NYC, redlining was accompanied by practices, like blockbusting, which led to homeowners being harassed by brokers’ phone calls asking to sell in East Rockaway (Kaplan and Kaplan, 2003).

Initially, the Department of Welfare repurposed Rockaway’s beach bungalows to accommodate displaced populations (Callahan, 2010). Soon after, areas like Edgemere became targets of slum clearance, but instead of being relocated within Rockaway, residents were only offered the option of moving to other boroughs. In 1961, the city constructed the first and largest public housing complex in Rockaway. Meanwhile on the West side of the peninsula, organized in civic and commercial associations, local white people did whatever was in their power to evict “undesirable” tenants of color and to prevent any public housing projects or public open space projects that would disrupt their white enclaves (Kaplan and Kaplan, 2003).

Between 1963 and 1974, NYS Urban Development Corporation built a total of 1,300 units of affordable housing between Edgemere and other neighborhoods of East Rockaway. During the 1960s, public housing became increasingly exclusively available for families on welfare programs. The most difficult family cases from Manhattan and other Boroughs were sent to the Eastern portion of the Rockaway, where city housing agencies failed to make provisions for necessary supporting services.

At the same time, a series of court rulings gave New York City extensive eminent domain powers and authority over what land could be condemned to advance urban renewal plans (Soomro, 2019). When the Edgemere Urban Renewal Area plan was adopted in 1997, several housing and commercial uses were added. HPD acquired 89 parcels, only a small fraction of those not already owned by the city, but only built 200 out of 800 housing units and delivered none of the 100,000 sq. ft. of retail space (CPC, 1997). The 2007 mortgage foreclosure crisis brought the renewal plan to a standstill leading to more abandoned homes, with East Rockaway experiencing double the NYC rate of foreclosure in 2011 (FRB, 2011). Many 1997 amendments never materialized in actual homes or commercial spaces created yet kept resurfacing in subsequent amendments.

Interviewees who moved into the neighborhood around 2007 remember signs of abandonment and decay in the form of “dirt roads” and “zombie houses” on their block – an informal term for boarded up abandoned homes. Ultimately, individual citizens and community groups typically do not have the resources to be watchdog organizations that can keep track and attempt to hold the city and developers accountable for broken promises. Urban renewal projects last decades, and politicians who negotiated these agreements leave office by the time the planned development is complete (Schiller and Thill, 2023).

6.2 Present harms and race-linked housing and planning practices

Disinvestment in some of the eastern portions of Rockaway continues today. Interviewees highlighted three main areas of concern: access to services, abandonment and decay, and diminished neighborhood economy. In terms of services, half of the interviewees mentioned how hard it is to get urgent care, including maternal care and trauma care in the area, since the Peninsula Hospital shut down in 2011 due to bankruptcy. Since its closure residents have had to rely on expensive private hospitals or clinics or travel farther away. According to Sarah, who rallied to bring back the Peninsula Hospital, “nobody wanted to step in to save it” when it ran out of money.

Other residents mentioned the paucity of transportation options to reach other boroughs and neighborhoods. The A train is the only subway line, and while two buses were introduced in 2017, they mostly run on major roads. The situation is a long-standing concern in Edgemere, as well as other transit deserts (Jiao and Dillivan, 2013) in Rockaway (The Wave, 2020) especially for elderly and disabled people living far from the subway.

Easy access to healthy food options is another major concern, frequently understood as having fruits and vegetables available within walking distance (Rahkovsky and Snyder, 2015). The only large supermarket is however two subway stops away from Edgemere and there are no other grocery stores for fresh produce in the vicinity. In the Rockaways, only 34% of residents live within a 5 min walk to fresh produce compared to 49% citywide (New York City Food Policy Center, 2017).

A few interviewees connected disinvestment in their neighborhood with the visible lack of commercial spending opportunities, youth employment, and banking services. For instance, Lorraine noted:“I have to shop outside of my community. My neighbors have to shop outside of our community, our dollars do not mature in our community. We do not have an economic base in our community because all of our money goes out to support other communities […]. So we are taking our disposable income, our discretionary income out of this community. And it’s not being put back into our community. So apathy exists among residents, whether you are a homeowner or you are a tenant living in public housing or living in a private home, your dollars are not coming back to your community.” (Lorraine, Pos. 41). Indeed, Edgemere has very little local multiplier effect (CDC, 2014) which worsened when many businesses shut down in the aftermath of Sandy.

6.3 Immediate post-Sandy recovery harms

Within immediate post-Sandy recovery, half of interviewed residents brought to the fore the nuisance caused by city sponsored programs like Build-it-Back (BiB) and Rapid Repair (RR). None of the interviewees elevated their homes, mostly because when the property is attached, this means agreeing with their neighbor to do so, and agreement wasn’t reached. The general feeling was that, at best, the RR program and the elevation programs were not serving residents’ needs, and at worst, scams occurred. The RR program assisted residential owners with emergency repairs to their private properties to alleviate emergency conditions and allow them to return to their properties. Residents spoke out about how shoddy and slow the work was and that there were “antagonistic relationships” with the workers hired by the program and the contractors, who seemed to be cutting costs whenever possible to the detriment of quality repairs. Some residents ended up getting their own electricians or continuing the work by themselves, incurring extra costs.

These episodes are backed by a 2017 report by the NYC Department of Investigation confirming that contractors overstated the quantities of items being installed in homes, including electrical wiring and additional problems with reimbursement from damage assessments, saving millions of dollars. The document cites “poor oversight of the approval process” and “poor procedures in place by contractors to calculate construction items installed in homes” (Struzzi and Urso, 2015, p. 3).

Flood insurance coverage was another source of immediate post-storm harm for 25% of the interviewees. Indeed, there is evidence that even homeowners, like Mercedes, who had flood insurance prior to Sandy, did not receive enough payment to rebuild without taking on debt and having to use their own savings. Other studies confirmed this occurrence in other parts of Rockaway and Staten Island (Madajewicz, 2020; Koslov, 2021). Also, as risk heightened following the storm, Mercedes and Christine were dropped by their flood insurance provider and had to organize a class action lawsuit and find a new insurer. Furthermore, in order to minimize the risk of homeowners walking away after cashing a flood insurance payout, FEMA set up a system of phased payments with the guarantee of issuing another after receiving receipts for how the money was spent on the first check issued. But homeowners like Melanie, who regularly paid for flood insurance and had no intention of cashing and leaving, were upset by the time-consuming burden of this bureaucratic measure.

6.4 The threat of present and future flooding and perceptions of managed retreat

The threat of present and future flooding was mentioned by 75% of the interviewees but the degree to which flooding is perceived as a threat is very nuanced. Two respondents felt they had no control over it; one thought it wasn’t a responsibility for homeowners but rather for city agencies; others said future flooding was a concern but that another storm of such magnitude was unlikely to occur again. All the above responses recall fatalism, denialism and wishful thinking and are considered non-protective responses to perceived risk in flood mitigation behavior literature (Bubeck et al., 2013).

Of the six interviewees who addressed managed retreat, only Christopher contemplated the idea of accepting a buyout depending on “what was offered” as compensation, which is an important variable of buyout acceptance (Seebauer and Winkler, 2020). One other stated they would not leave because theirs is a prime location by the water. A resident said they would come back again and repair their home, like they did after Sandy. Studies show that location is a promiscuous factor in buyout acceptance because it can indicate multiple things to a homeowner, some positive (water proximity) some negative (risk of future damage; Robinson et al., 2018). Ana said that Edgemere is “where they can afford to live,” which points to residents’ concerns over their ability to secure an alternative housing solution (Greer and Binder Brokkop, 2017). Lorraine felt that city and federal agencies needed to fulfill their duty to protect people in place:

“If the proper resiliency infrastructure was in place, community members wouldn't need to move or relocate. Give us the same resiliency investments as Battery Park City. They are not buying out or displacing wealthier communities. I sincerely hope more communities and their residents start pushing back on these so-called buyouts and force the Government to do the necessary resiliency building needed.” (Lorraine, Pos 74)

Lorraine is pushing back on the city’s Coastal Land Use Framework narrative of protecting people in place where land use factors are conducive to growth (see 7.4). Although the US Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) plans to invest $252,544,000 in measures to reduce flood risk in mid-Rockaway (USACE, 2019) many citizens do not yet know about this plan because it is still in design phase (USACE, 2023).

7 Discussion

7.1 Reading post-buyout land restoration through Edgemere’s contextual justice and senses of justice

The analysis of subjects reveals that children and youth more broadly, homeowners’ rights, community solidarity and belonging according to Edgemere residents need moral and political attention. Land restoration opportunities should then account for high quality uses such as playgrounds, athletic fields and create uses conducive to block or garden parties, collaboration in yard or vacant lot work—that foster collective activity with neighbors and have the potential to create social cohesion and enhance awareness of how to steward vacant land (Stewart et al., 2019). When it comes to homeowners’ rights, some expressed fear that some land uses on vacant lots next to their property may cause nuisance or vandalism, which other studies also recognized (Anderson and Minor, 2017). Although civic engagement in vacant land restoration is important for anyone living in high vacancy areas (Kim et al., 2020) it is even more essential that homeowners living adjacent to a vacant lot partake into decisions about its potential uses and be given the right of refusal of interim public uses and the options to purchase the land. Ownership of land increases the chances that communities will put in time and other resources to steward it when they know it will not be taken away (Németh and Langhorst, 2014).

The analysis of senses of justice also revealed how black and brown people make place amidst and in spite of oppressive realities as Hunter et al. (2016) put it. Hosting cookouts, having neighbors’ children over to play in one’s yard, and community gardening are sources of belonging and liberation in wounded places like Edgemere (see 5.4). Sites of belonging, liberation, endurance and resistance often start from homely practices of black and brown place making that are usually discounted, but which are crucial to heal from historic trauma and form kinship to withstand stressors (Smith, 1989; Carroll, 2015; Heynen and Ybarra, 2021) caused by institutional neglect and racism and more frequent climate induced disasters. The opportunity to rethink vacant lots in floodplains, may initiate a process of undoing past harms (Dascher et al., 2023) as well as sites for the practice, articulation and enactment of resistance (Scott, 1990) to unjust treatment. Climate change practice as well as post-buyout land restoration cannot be divorced from harm done to black and brown spaces and bodies through histories of colonialism and contemporary race linked housing, planning and health, but they also should not be only confined to analyzing and retelling stories of injuries (Hunter et al., 2016). As McKittrick (2021, p. 50) put it when addressing the importance of a black sense of place, this kind of practice also “re-orients what we know by honoring where we know from. We choose to know from the perspective of black and brown folks because we believe in black and brown humanity.”

7.2 Interactions between contextual, distributive and recognitional justice

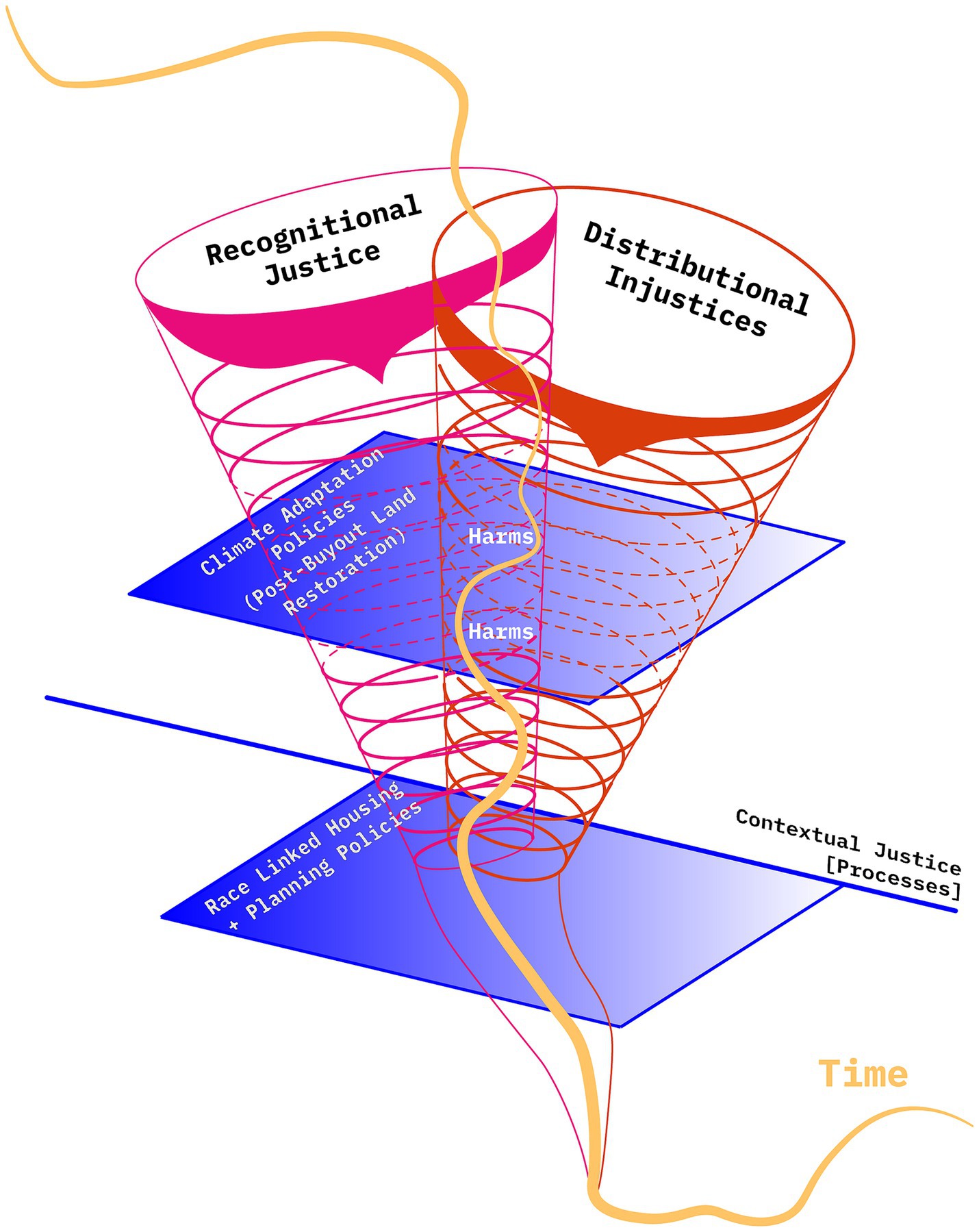

Though much of the scholarly literature focuses on distributional and procedural justice sometimes together, but more often separately, research poorly integrates recognitional and contextual justice together with these other dimensions. This study provides empirical evidence of how key dimensions of justice are perceived in land restoration after retreat. Results highlight both the interconnections and vicious cycles that exist between justice’s dimensions and provide a few concrete examples of how they unfold in the case of Edgemere. Figure 4 illustrates these relations in graphic form. For instance, the data suggests a clear link between contextual and distributional injustices (the blue plain intersects with the red cone in Figure 4), where systemic structural injustices in housing, food security, and healthcare make climate vulnerability and recovery incredibly difficult and a source of sustained trauma. They also make acting toward land restoration almost trivial compared to other livelihood needs. But these structural injustices also make losing homes or new land easements, a threat multiplier for a community that is been neglected through time. Many scholars emphasize that retreat is not just about property, infrastructure, market value and individuality (Marino, 2018) and it will result in social failure if place attachments, livelihoods, cultural integrity, sense of belonging and humanity go unaddressed (Burley et al., 2007; Agyeman et al., 2009; Felipe Pérez and Tomaselli, 2021).

Figure 4. Analytical framework showing how recognitional and distributional injustices (symbolic and material harms) interconnect and arise from unjust contextual processes across time.

The data also points to the influence that distributive harms can have over generating injustices of recognition (the pink and red cone intersecting with each other and with past and current policies plains in Figure 4). Unmaintained promises of urban renewal can be linked to feelings of betrayal, while group disrespect was more strongly mentioned toward local authorities’ practices of ‘welfare dumping’ and the policy of retreat. Neighborhood reputation is connected to past and present histories of crime, illegality, poverty and overall perceived quality of life in Edgemere. Distributive justice was closely related to the principle of need as well as equality, or the wish by Edgemere residents to have equal access to services, homes, safety and protection from climate risks. Recognitional injustice expressed as reputation, disrespect and betrayal may be linked to the idea of recognition as respect, or that individuals must enjoy the same fundamental rights in order to fulfill their autonomy (Thompson, 2006). These associations between dimensions of justice and underlying principles are confirmed in one other study (Lecuyer et al., 2018) while the interconnections between contextual, distributive and recognitional justice align with observations made by Walker (2023) who studied retreat in New York State’s rural communities.

This study shows how group mistreatment rooted in contextual injustices generates community divisions with possible implications for community organizing. Group mistreatment becomes a sign of recognitional injustice, which can arise from individual experiences of injustice that may become typical of an entire group (Honneth, 1995) meaning that personal experiences of suffering are understood as affecting others too (Honneth, 1995; Pilapil, 2013). These feelings can fuel collective struggles for recognition through shared meanings and resistance. If Edgemere residents are splintered, as this study suggests (see 5.1), also the practicing, articulation and enactment of organizing is fractured. Existing homeowners and renters’ divisions make it hard for Edgemere residents to organize and advocate around common harms, such as prompt flood risk reduction, housing affordability, environmental racism and availability of services. Social sites set apart from domination are needed for such meaning and practices to rise safely and land stewardship on Edgemere’s vacant lots should emphasize opportunities for such sites of self-determination to emerge (Shepard, 2022).

7.3 The implications of Edgemere’s contextual justice for retreat policy

Landscapes of race and deep histories of colonialism and racism shape the socio-ecological formations of US low-lying coastal areas (Hardy et al., 2017). Edgemere’s history is rooted in the fundamental lack of interest in protecting and in the thriving of black and brown spaces, which is of course not just a Rockaway history, but symbolizes the greed, opportunism, bigotry, racism and indifference to the poor in general and, to poor black and brown people in particular, that characterized much of the postwar decades (Sugrue, 2005; Cebul, 2020).

One may read Edgemere as part of what McKittrick and others called “urbicide”—killing of the city—where place, poverty and racial violence converge (McKittrick, 2011). A place where this violence not only manifests in undelivered services or letting key structures like hospitals go bankrupt, but also through extensive amounts of vacant land. As a marker of “urban decline” in popular discourses, where the state of urban infrastructure is linked to community character, representations of property vacancy can “calcify the seeming natural links between blackness, underdevelopment, poverty, and place” (McKittrick, 2011, p. 951). While New York City did not suffer from the same scale of de-industrialization as Detroit, Philadelphia and St. Louis, and it has infinitesimal amounts of vacant land compared to these cities, the borough of Queens and especially Eastern Rockaway, has historically had the largest density of vacant land, mostly characterized by small and medium sized lots (Kremer et al., 2013). As this study shows, Edgemere’s depressed landscape did not happen by chance, but it was the result of the little interest politicians had in the land and people living on it and where failed renewal befell through both local (city council running out of funds) and cascading international market failures (the mortgage crisis).

A contextual justice approach reveals how the contemporary racial geographies of Edgemere (of segregation, disinvestment and displacement) are the outcome of planning policies (housing, zoning and urban renewal) sorting out who lives where and under what conditions (Stein, 2019) effectively continuing the racial differentiation and domination and settler colonial style dispossessions (Porter, 2016). Contextual justice also shows how terraforming, and development are used to tame the sea and to make space for habitable land that today is some of the most vulnerable land to the effects of sea level rise. To most black and brown communities of Edgemere who took part in this study the idea of retreating is just another form of betrayal and should represent an equity dilemma to city officers proposing it. Retreating is difficult for any community independently of class and race, but communities that are repressed in many other ways experience retreat as a new form of neglect. When group feelings of injustice, such as betrayal, group disrespect and differential treatment go unsolved for so long these can generate renewed distrust in government agencies tasked with building urban climate adaptation (Rudge, 2021; Teirstein, 2022) and land restoration.

Should more retreat be proposed in the future, this study shows that existing in-community divisions (between renters and homeowners) could be detrimental for groups that are least able to navigate retreat plans (whether homeowners or renters). As Lynn (2017) suggested after studying the retreat of Kashmere Gardens in Harris County (Texas), retreat requires that homeowners to take upon themselves to stay informed of developments, communicating with other affected households and sharing information. It also requires pooling resources and hiring lawyers and appraisers familiar with public agency-sponsored retreat. This kind of organizing in Edgemere may be possible if ECCA steps up and other civic associations are formed to become a reference point with both public agencies, appraisers and homeowners. Renters, however, may still need to rely on public officials ramping up education and outreach campaigns about risks and insurance or implementing advanced door-to-door information campaign as part of FEMA’s Credit Rating System (CRS; Dundon and Abkowitz, 2021) of which the city of New York is part.

7.4 Dilemma in the making: retreating, reducing flood risks and green climate gentrification

Edgemere is an example of the present dilemmas of the concomitant climate and housing crises in New York City, where more housing gets built in floodplains at risk without also bringing adequate neighborhood infrastructure. New planned developments in Edgemere exemplify two dynamics. Firstly, that although the REPCI was successful in proposing permanent affordable housing and community stewardship of the land through the Edgemere CLT, the new mixed use developments currently being built are largely an attempt at mobilizing the resilience script to further neoliberal capital agendas for economic gains at expense of climate change risks (Karki, 2021; Camponeschi, 2023). Instead of addressing decades of disinvestment as city officers seem to think, developments may bring climate gentrification upon Edgemere and other eastward neighborhoods of Rockaway (Ehrenfeucht and Nelson, 2020; Shokry et al., 2020).