- 1School of Government and Public Transformation, Tecnologico de Monterrey, Monterrey, Nuevo Leon, Mexico

- 2RAND, Santa Monica, CA, United States

Media narratives employed in contemporary journalism, including data journalism, are critical in shaping public understanding of the complex systems that affect our lives. Depicting a chain of events in a “story” format, narratives are constructed with detailed, precise, and well-researched information based on character identification, human emotions, and real social problems. In many ways, they are indispensable intermediaries of practiced judgment and expertise that guide the public to meaningfully engage with evidence-based understanding of our world and how we can act upon it. DMDU narratives suggest that we can act to shape the future toward our liking even when we cannot predict what that future will be, that we need to simultaneously consider multiple rather than a single future, and that the quest for prediction can interfere with the task of identifying the best actions. DMDU practice relies on substantive stakeholder interaction, and it is supported by vast amounts of empirical evidence. This perspective discusses how media narratives intersect with DMDU to inform and to leverage the complexities of modern contemporary public challenges. We first explore how uncertainty might be actionable, as opposed to fearful. Next, while acknowledging limitations on transference of information during the journalistic process, we address the challenges and best strategies to distill information to the public to maintain and build trust about uncertainty. Next, we discuss how journalistic practices could be useful for disseminating more broadly findings of DMDU analyses.

Introduction

Media narratives1 play a significant role in shaping how people perceive and understand the complex issues that influence our lives. These narratives help to convey intricate details and foster comprehension among the public. However, uncertainty complicates these narratives, forcing journalists to balance uncomfortably between accuracy and telling a compelling story. This balancing act often leads to challenges in maintaining the integrity of the information while still engaging the audience. When knowledge is limited and complexity is high, the media may amplify certain narratives and perspectives (Kasperson et al., 2022), influencing public opinion and subsequent decision-making.

Decision Making under Deep Uncertainty (DMDU) traditionally focuses less on narratives, but its methodologies support an account that uncertainty is actionable. DMDU communicates the implications of different scenarios by identifying key decision trade-offs and vulnerabilities, suggesting robust, flexible responses that perform well over a wide range of futures (Lempert et al., 2006; Marchau et al., 2014; Kwakkel et al., 2016). But because DMDU has traditionally emphasized technical details and quantitative analysis, its results can become overly complex and difficult to disseminate broadly.

This perspective explores the extent to which DMDU narratives regarding uncertainty can help journalists mitigate the tradeoff between accuracy and compelling storytelling. By crafting stories that include uncertainty as a fundamental theme, journalists can create engaging narratives that remain faithful to the complexities involved. Furthermore, understanding and informing media narratives can help DMDU practitioners craft more compelling stories about their own work.

We discuss and exemplify how DMDU practice transforms uncertainty into actionable information, motivating individuals and organizations to act despite inherent uncertainties. We then analyze, from the journalism practice perspective, the challenges associated with conveying complex information through narrative journalism and discuss examples of the strategies that journalists use to distill information effectively while maintaining accuracy and trust. Finally, we examine how the intersection between DMDU research and narrative journalism can foster a deeper understanding of complex issues, empowering the public to participate in informed discussions and advocate for effective policies.

The narrative of uncertainty as actionable

Navigating complex systems under deep uncertainty2 often leads to paralysis and political gridlock. DMDU methods address these challenges with multi-scenario, multi-objective analytic tools and processes of stakeholder engagement using these tools. DMDU analytics use simulation models to scan over large numbers of plausible futures, statistical algorithms to cluster those futures into policy-relevant scenarios, and then help identify actions policy makers can take that make sense over a wide range of futures. DMDU participatory stakeholder engagement helps frame the analyses, generate shared understanding of key tradeoffs, and build consensus on near-term actions. DMDU leverages the very ambiguity of these decision-making contexts to activate informed action (Lempert et al., 2006; Marchau et al., 2014).

DMDU computer assisted reasoning leads to the development of dynamic narratives based primarily on empirical findings. Exploratory modeling enables decision-makers and stakeholders to quantitatively assess the implication of vast arrays of different alternative futures. This experimental engagement goes beyond abstract risk assessments, injecting curiosity and a sense of agency into the decision-making process. Unlike unidimensional predictions, DMDU computational experimentation methods encourage exploration, prompting stakeholders to test their assumptions in different situations, despite the absence of certainty in prediction (Groves and Lempert, 2007; Bryant and Lempert, 2010; Kwakkel and Pruyt, 2013).

DMDU methods, like scenario discovery and adaptive pathways, leverage uncertainty to identify key tradeoffs in decision-making. By exploring vast arrays of uncertainties and courses of action, DMDU methods seek to identify key assumptions upon which different decisions are guaranteed. This “stress-testing” exposes unforeseen vulnerabilities and fosters adaptive planning (Bryant and Lempert, 2010; Moallemi et al., 2020). Studies that use DMDU methods often identify potential pitfalls and unintended consequences of status-quo actions. This often empowers stakeholders to refine the design of their policies and plans before committing to real-world implementation (Groves et al., 2019; Molina-Perez et al., 2019; Kalra et al., 2023; Moallemi et al., 2023). Empirical studies support these DMDU methods for making uncertainty actionable. For instance, presentations of climate information that emphasize intersection (e.g., that experts agree on a range of projections) and balance (e.g., avoid unwarranted precision) generate more confidence than presentations that emphasize disagreement over specific projections or seem overly precise (Benjamin and Budescu, 2018). Decision support tools that present uncertainty as a range of scenarios encourage users to seek more resilient strategies than decision support that present uncertainty with best-estimate probability distributions (Gong et al., 2017).

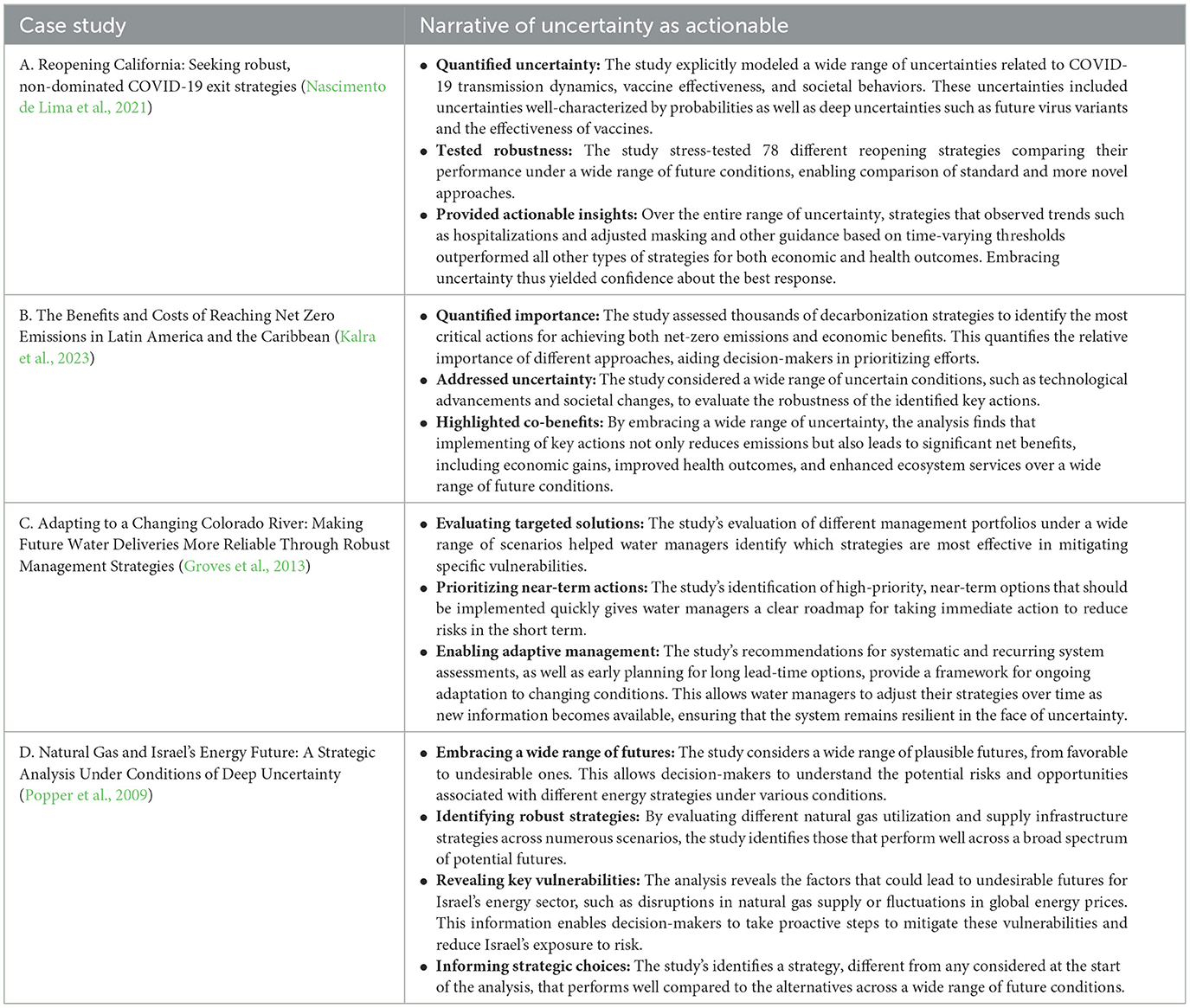

Existent literature in which DMDU methods and processes have been applied show that this analysis framework is conducive to construct actionable narratives that incentivize policy action. Table 1 summarizes four DMDU case studies. These four studies, despite their diverse contexts, collectively exemplify a narrative of uncertainty as actionable, revealing both commonalities and nuances in how they utilize DMDU methods to transform uncertainty into policy debate, re-design, and adaptation.

The four examples explicitly acknowledge and quantify uncertainty. In the pandemic response and Colorado River Basin studies, this involved modeling a wide range of scenarios to understand potential vulnerabilities and stress-test different strategies. The Israeli energy study embraced uncertainty by considering diverse plausible futures, while the decarbonization study quantified the relative importance of actions under varying conditions. This shared emphasis on quantification allows for more systematic decision-making under uncertainty. However, each case study operationalizes uncertainty differently. The pandemic response and Colorado River Basin studies focused on identifying vulnerabilities and evaluating targeted solutions, whereas the Israeli energy study prioritized the identification of robust strategies that perform well across diverse scenarios. The decarbonization study, on the other hand, emphasized the co-benefits of actions, making a compelling case for their implementation even under uncertain conditions. All studies highlight the importance of continuous learning and adaptation in the face of uncertainty. The pandemic response and Colorado River Basin studies explicitly recommend ongoing monitoring and evaluation to inform future decisions. The Israeli energy study emphasizes the need for strategies that are adaptable to changing conditions, while the decarbonization study underscores the importance of co-benefits in maintaining support for actions over time.

These four examples show how DMDU methods can lead to narratives where uncertainty is not a roadblock, but rather a steppingstone toward more informed, robust, and adaptive decision-making. In many respects, DMDU enables a process where it is possible to create a kaleidoscope of possible futures. By identifying “policy-relevant scenarios,” DMDU methods showcase diverse outcomes from multiple perspectives and dimensions of merit (Lempert et al., 2003; Haasnoot et al., 2013). ultimately equipping decision-makers with contingency plans and enabling them to navigate unexpected turns in a world in constant flux.

Journalistic processes to report deeply uncertain phenomena

The inherent tension in journalism between the pursuit of accuracy and the creation of compelling narratives is amplified when reporting on complex and uncertain phenomena.3 The dilemma lies in the fact that achieving absolute accuracy can sometimes lead to stories that are too technical or complex for a broad audience to follow, diminishing their appeal and impact.

Scientific claims are often accompanied by significant uncertainties. Journalists face a critical decision point in how to incorporate this uncertainty into their reporting. Ignoring uncertainty and presenting scientific findings as absolute truths can mislead the public and create a false sense of security. Conversely, abstaining from reporting on uncertain topics can deprive the public of crucial information and hinder informed decision-making.

A balanced approach, incorporating rhetorical techniques or diverse perspectives, can effectively contextualize scientific claims within the broader landscape of uncertainty (Peters and Dunwoody, 2016). Journalists' decisions about how to include uncertainty are influenced by several factors:

• Perceived uncertainty in the field: Journalists' understanding of the level of uncertainty inherent in the research they are reporting on.

• Audience expectations: The perceived needs and knowledge level of the intended audience.

• Competing media: The editorial choices made by other media outlets covering the same topic (Guenther and Ruhrmann, 2016).

Scientific claims in mass-media are often presented as more certain than would been described by the scientific community. This tendency can lead to an underestimation of risks (Peters and Dunwoody, 2016). In contrast, presenting conflicting scientific claims in media stories can lead to exaggerated audience perceptions of uncertainty (Kohl et al., 2016).

The motivations of various stakeholders, including scientists, representatives of companies, public interest groups, and government agencies, influence their willingness to talk about uncertainties. These motivations can be related to concerns about policy, public perception, or the potential consequences of acknowledging uncertainties (Post, 2016). Audience engagement also plays an important role (Besley et al., 2015). Comments and discussions by readers can alter the perceived meaning of stories, impacting the interpretation of uncertainty or certainty in the phenomenon being reported (Peters and Dunwoody, 2016).

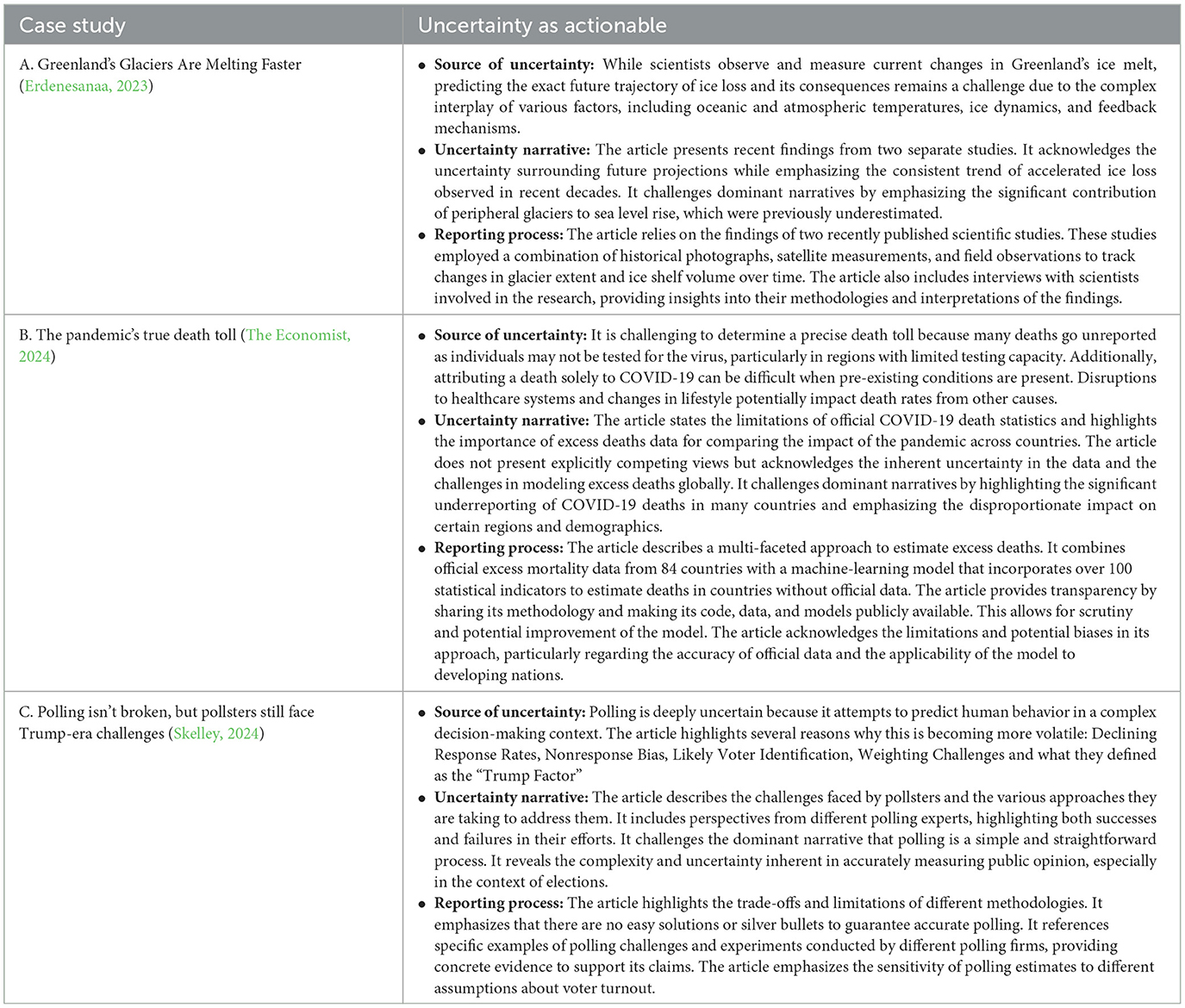

Table 2 provides three examples of journalistic efforts to report on deeply uncertain phenomena. The three examples use distinct journalistic approaches to deal with uncertainty. The Greenland ice melt article acknowledges the uncertainty inherent in predicting future ice loss, emphasizing the consensus among scientists regarding the accelerated melting trend while transparently citing recent studies as the basis for its reporting. The COVID-19 death toll article explicitly grapples with the complexities of defining and measuring the pandemic's impact, presenting its own model for estimating excess deaths while openly discussing its limitations and potential biases. The article on polling uncertainty, on the other hand, focuses on the methodological challenges and potential inaccuracies in polling, quoting experts and citing studies to contextualize the issue.

While all three articles acknowledge the inherent uncertainty in their respective topics, the degree of transparency and depth of analysis varies. The Economist's COVID-19 article focusses on the methodological approach and its potential limitations, inviting scrutiny and potential improvement. The Greenland article, while citing scientific studies, does not delve into the methodological details as deeply. The polling article, while informative, focuses more on highlighting the issue of uncertainty rather than providing a comprehensive solution. This diversity reflects the complexity of reporting on uncertain topics and the importance of transparency and critical analysis in journalism.

Journalism on complex public policy issues requires continuous updating and adaptation, as well as meticulous fact-checking and compartmentalization of key facts (Dunwoody, 2020). Journalists play a pivotal role in creating a reporting space for uncertainty, allowing for the emergence of diverse perspectives and challenges to dominant narratives. While compelling narratives are essential for popular journalism, editorial decisions must be made to mediate uncertainty and complexity need to be made. This editorial expertise can be of great value for the dissemination of DMDU research (Duffy, 2021).

Lessons DMDU and journalism can offer to one another

The fields of DMDU and journalism have valuable lessons each can offer to the other. For journalists grappling with the challenge of telling a crisp and accurate story amidst contested and inherently uncertain facts, DMDU offers a narrative of managing as opposed to reducing deep uncertainty. Rather than recounting a search for the truth, the narrative focuses on a recognition of inevitable surprise and skillful navigation (or the lack thereof) in the face of this reality. DMDU narratives highlight virtues that include a willingness to embrace uncertainty, humility about one's understanding, adaptability as conditions change, and finding certainty in robust and resilient plans rather than in any conviction that the world will behave as we expect.

DMDU suggests key themes journalists might explore in crafting narratives about uncertainty. The first is due diligence—to what extent do decision makers understand the vulnerabilities of their plans by having stress tested them over a wide range of futures? DMDU suggests that all policies are based in assumptions and many assumptions can potentially fail. Journalists can inquire whether decision makers have identified the conditions under which their plans will meet and miss their goals.

DMDU also encourages journalists to highlight the implications of high confidence information and the areas of agreement among contesting parties. For instance, DMDU uses high confidence information to identify scenarios that all can agree are policy-relevant, even if there exists significant disagreement as to their likelihood. In a typical example, all parties might agree that power plant near the shoreline would become inoperable if sea level rise exceeds one meter. But some might regard the likelihood of such a rise this century as too small to consider while others might see a much larger risk. Journalists can weaver a story around this disagreement while making clear that all would regard a meter of sea level rise as problematic.

Finally, DMDU encourages journalists to examine the extent to which decision makers have made uncertainty actionable—crafting policies that are robust and resilient. To what extent are policies designed to achieve their goals when things, as they often do, go wrong? Do decision makers exercise the necessary adaptiveness and flexibility? Assuming decision makers understand the futures in which their plans meet and miss their goals, can they describe how they are monitoring for such conditions? Have decision makers articulated what they will do if such conditions arise? Can decision makers explain why the balance of risks and opportunities in the plan they propose outweigh those of the alternatives?

DMDU practitioners seeking policy impact from their analyses can gain guidance from journalists' need to balance accuracy with compelling narratives. DMDU practitioners can emphasize the certainties that emerge from their analyses alongside the uncertainties. Practitioners can tell stories about making uncertainty actionable, using the embrace of uncertainty to motivate robust and resilient responses. They can tell stories about the process of going from uncertainty about what will happen to certainty about vulnerabilities and the best responses to them. Practitioners can describe how the analysis addresses the concerns and interests of various contesting parties to the policy debate. As will any good policy analysis, DMDU practitioners can also emphasize the concrete policy implications of their work.

Future directions

DMDU practitioners and journalists, despite operating in different fields, share a crucial common challenge: making complex information understandable, engaging, and useful for decision-making. Borrowing practices from journalists, DMDU practitioners can improve their delivery of DMDU analyses. To enable this, we identify three key areas for future research and work:

• Editorial role in DMDU practice: ultimately deciding how to handle uncertainty in a DMDU application is a collaborative effort between researchers, sponsors and government counterparts. However, the processes editors use and their experience in dealing with uncertainty in journalism can benefit DMDU practices. This includes rigorous quality assurance to guarantee scientific integrity, replicability and transparency of findings, but also editorial decisions that can help the team focus on the most relevant aspects of the analysis, ensuring budget and time constraints are met. A DMDU editor can help the team identify the core findings of their research and present them upfront, with supporting details following in a clear hierarchy.

• Framing DMDU findings as narratives: journalists excel at crafting compelling narratives that engage the public and guide them through the complexities and uncertainties of a topic. DMDU practitioners can adopt this approach by framing their findings as stories with a clear beginning, middle, and end. Highlight the decision tradeoffs contained in the data, its significance for the decision context under consideration and the potential implications for the stakeholders participating in the study. Being aware of the potential cognitive biases and framing effects of media narratives that readers may hold that influence their evaluation of different options and trade-offs with respect to an issue.

• Meaningful engagement with DMDU findings: journalists utilize diverse and creative ways to present data, such as infographics, interactive maps and visualizations, and animations. DMDU practitioners can explore these options to make their findings visually appealing, interactive, and easier to understand for their audiences. In fact, wider dissemination of DMDU work in this form, can enable bigger audiences to engage with DMDU analyses. This can enable learning from audience engagement through strategies used by journalists, like interactive forums, comments, and social media outreach, to tailor DMDU analysis delivery and foster meaningful dialogue with the public.

Progress in these areas can help the DMDU community apply systematically journalist-inspired approaches to deal with uncertainty. This can effectively help improve how DMDU findings are communicated, fostering trust and transparency, encouraging critical thinking, and enabling wider public engagement with DMDU findings.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

EM-P: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. RL: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JW: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

EM-P, RL, and JW wish to thank Andy Revkin, Sofia Ramirez, and Geoff McGhee for their participation in a panel on the topic of this article at the 2023 DMDU Society meeting in Mexico City and for crystalizing our interest in many of the questions discussed here.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^In this perspective we define narratives as stories with a beginning, middle, and end. Such stories have characters, temporality, and causality, and the details have cause-effect patterns, giving them their persuasive force (Dahlstrom, 2014).

2. ^Deep uncertainty refers to the lack of knowledge about what the future holds. When decision makers ignore this reality, they can become overly confident, miss out on opportunities, and implement policies that are vulnerable to unexpected events. Deep uncertainty arises when experts or stakeholders do not know or cannot agree on: (1) suitable models to represent the relationships between key factors influencing a system, (2) the probabilities associated with crucial variables and parameters, and (3) the relative importance and desirability of different potential outcomes.

3. ^There are typically two definitions of uncertainty in the media: (1) probabilistic uncertainty, that is, uncertainty about specific events where the statistical distribution is known, and (2) epistemic uncertainty, that is, uncertainty arising from the validity of truth claims (Peters and Dunwoody, 2016).

References

Benjamin, D. M., and Budescu, D. V. (2018). The role of type and source of uncertainty on the processing of climate models projections. Front. Psychol. 9:403. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00403

Besley, J. C., Dudo, A., and Storksdieck, M. (2015). Scientists' views about communication training. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 52, 199–220. doi: 10.1002/tea.21186

Bryant, B. P., and Lempert, R. J. (2010). Thinking inside the box: a participatory, computer-assisted approach to scenario discovery. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 77, 34–49. doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2009.08.002

Dahlstrom, M. F. (2014). Using narratives and storytelling to communicate science with nonexpert audiences. PANAS. 111, 13614–20. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1320645111

Duffy, A. (2021). Out of the shadows: the editor as a defining characteristic of journalism. Journalism 22, 634–649. doi: 10.1177/1464884919826818

Dunwoody, S. (2020). Science journalism and pandemic uncertainty. Media Commun. 8, 471–474. doi: 10.17645/mac.v8i2.3224

Erdenesanaa, D. (2023). Two Studies on Greenland Reveal Ominous Signs for Sea Level Rise. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2023/11/09/climate/greenland-glaciers-ice-melt.html (accessed November 9, 2023).

Gong, M., Lempert, R., Parker, A., Mayer, L., Fischbach, J., Sisco, M., et al. (2017). Testing the scenario hypothesis: an experimental comparison of scenarios and forecasts for decision support in a complex decision environment. Environm. Model. Softw. 91, 135–155. doi: 10.1016/j.envsoft.2017.02.002

Groves, D. G., Fischbach, J. R., Bloom, E., Knopman, D., and Keefe, R. (2013). Adapting to a Changing Colorado River: Making Future Water Deliveries More Reliable Through Robust Management Strategies. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation. Available at: https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR242.html2

Groves, D. G., and Lempert, R. J. (2007). A new analytic method for finding policy-relevant scenarios. Global Environm. Change 17, 73–85. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2006.11.006

Groves, D. G., Molina-Perez, E., Bloom, E., and Fischbach, J. R. (2019). “Robust Decision Making (RDM): application to water planning and climate policy,” in Decision Making under Deep Uncertainty: From Theory to Practice (Cham: Springer), 135–163.

Guenther, L., and Ruhrmann, G. (2016). Scientific evidence and mass media: Investigating the journalistic intention to represent scientific uncertainty. Public Understand. Sci. 25, 927–943. doi: 10.1177/0963662515625479

Haasnoot, M., Kwakkel, J. H., Walker, W. E., and Maat, J. T. (2013). Dynamic adaptive policy pathways: a method for crafting robust decisions for a deeply uncertain world. Global Environm. Change 23, 485–498. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2012.12.006

Kalra, N., Molina-Perez, E., Syme, J., Esteves, F., Cortés, H., Rodríguez-Cervantes, M. T., et al. (2023). The Benefits and Costs of Reaching Net Zero Emissions in Latin America and the Caribbean. New York: Inter-American Development Bank.

Kasperson, R. E., Webler, T., Ram, B., and Sutton, J. (2022). The social amplification of risk framework: new perspective. Risk Analysis 42, 1367–1380. doi: 10.1111/risa.13926

Kohl, P. A., Kim, S. Y., Peng, Y., Akin, H., Koh, E. J., Howell, A., et al. (2016). The influence of weight-of-evidence strategies on audience perceptions of (un)certainty when media cover contested science. Public Understand. Sci. 25, 976–991. doi: 10.1177/0963662515615087

Kwakkel, J. H., Haasnoot, M., and Walker, W. E. (2016). Developing dynamic adaptive policy pathways: a computer-assisted approach for developing adaptive strategies for a deeply uncertain world. Clim. Change 136, 495–518. doi: 10.1007/s10584-014-1210-4

Kwakkel, J. H., and Pruyt, E. (2013). Exploratory Modeling and Analysis, an approach for model-based foresight under deep uncertainty. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 80, 419–431. doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2012.10.005

Lempert, R. J., Groves, D. G., Popper, S. W., and Bankes, S. C. (2006). A general, analytic method for generating robust strategies and narrative scenarios. Manage. Sci. 52, 514–528. doi: 10.1287/mnsc.1050.0472

Lempert, R. J., Popper, S. W., and Bankes, S. C. (2003). Shaping the Next One Hundred Years: New Methods for Quantitative, Long-Term Policy Analysis. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation. Available at: https://www.rand.org/pubs/monograph_reports/MR1626.html

Marchau, V. A., Walker, W. E., Bloemen, P. J., and Popper, S. W. (2014). Structured decision making as a proactive approach to dealing with deep uncertainty. J. Environ. Manage. 146, 304–313.

Moallemi, E. A., Kwakkel, J., de Haan, F. J, and Bryan, B. A. (2020). Exploratory modeling for analyzing coupled human-natural systems under uncertainty. Global Environm. Change 65:102186. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2020.102186

Moallemi, E. A., Zare, F., Hebinck, A., Szetey, A., Molina-Perez, E., Zyngier, R. L., et al. (2023). Knowledge co-production for decision-making in human-natural systems under uncertainty. Global Environm. Change 82:102727. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2023.102727

Molina-Perez, E., Groves, D. G., Popper, S. W., Ramirez, A. I., and Crespo-Elizondo, R. (2019). Developing a Robust Water Strategy for Monterrey, Mexico: Diversification and Adaptation for Coping with Climate, Economic, and Technological Uncertainties. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation. Available at: https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR3017.html

Nascimento de Lima, P., Lempert, R., Vardavas, R., Baker, L., Ringel, J., Rutter, C. M., et al. (2021). Reopening California: seeking robust, non-dominated COVID-19 exit strategies. PLoS ONE 16:e0259166. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0259166

Peters, H. P., and Dunwoody, S. (2016). Scientific uncertainty in media content: Introduction to this special issue. Public Understand. Sci. 25, 893–908. doi: 10.1177/0963662516670765

Popper, S. W., Griffin, J., Berrebi, C., Light, T., and Daehner, E. M. (2009). Natural Gas and Israel's Energy Future: A Strategic Analysis Under Conditions of Deep Uncertainty. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation. Available at: https://www.rand.org/pubs/technical_reports/TR747.html

Post, S. (2016). Communicating science in public controversies: Strategic considerations of the German climate scientists. Public Understand. Sci. 25, 61–70. doi: 10.1177/0963662514521542

Skelley, G. (2024). Polling Isn't Broken, but Pollsters Still Face Trump-era Challenges. Available at: https://abcnews.go.com/538/polling-broken-pollsters-face-trump-era-challenges/story?id=110677969 (accessed May 30, 2024).

The Economist (2024). The Pandemic's True Death Toll. Available at: https://www.economist.com/graphic-detail/coronavirus-excess-deaths-estimates?fsrc=core-app-economist (accessed June 22, 2024).

Keywords: media narratives, deep uncertainty, journalism, complex systems, science communication

Citation: Molina-Perez E, Lempert RJ and Wong JCS (2024) How media narratives can be used in Decision Making under Deep Uncertainty practice? Front. Clim. 6:1380079. doi: 10.3389/fclim.2024.1380079

Received: 01 February 2024; Accepted: 12 August 2024;

Published: 12 September 2024.

Edited by:

Peter Haas, University of Massachusetts Amherst, United StatesReviewed by:

Bernd Siebenhüner, University of Oldenburg, GermanyCopyright © 2024 Molina-Perez, Lempert and Wong. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Edmundo Molina-Perez, ZWRtdW5kby5tb2xpbmFAdGVjLm14

Edmundo Molina-Perez

Edmundo Molina-Perez Robert J. Lempert

Robert J. Lempert Jody Chin Sing Wong

Jody Chin Sing Wong