- 1School of the Environment, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, QLD, Australia

- 2Climate Action Beacon and Griffith Institute for Tourism, Griffith University, Brisbane, QLD, Australia

- 3Cook Islands National Council of Women, Rarotonga, Cook Islands

- 4Further Arts, Port Vila, Vanuatu

As climate change worsens, loss and damage will rapidly accelerate, causing tremendous suffering worldwide. Conceptualising loss and damage based on what people value in their everyday lives and what they consider worth preserving in the face of risk needs to be at the centre of policy and funding. This study in three Pacific Island countries utilises a local, values-based approach to explore people’s experiences of climate change, including intolerable impacts, to inform locally meaningful priorities for funding, resources, and action. What people value determines what is considered intolerable, tolerable, and acceptable in terms of climate-driven loss and damage, and this can inform which responses should be prioritised and where resources should be allocated to preserve the things that are most important to people. Given people’s different value sets and experiences of climate change across places and contexts, intolerable impacts, and responses to address them are place-dependent. We call on policy makers to ensure that understandings of, and responses to, loss and damage are locally identified and led.

Introduction

Climate-driven loss and damage (L&D) is already with us (see early collation of studies by Warner and van der Geest, 2013). Even if the increase in global average temperature is limited to 2°C above pre-industrial levels, L&D will continue to be unavoidable for people around the globe (IPCC, 2018). L&D from climate change refers to the negative impacts that occur despite mitigation and adaptation efforts (Roberts and Huq, 2015). It can be irreversible (“loss”) or reversible (“damage”) and economic (i.e., things that are commonly traded on markets such as houses) or non-economic (i.e., things that are not widely traded on markets such as cultural knowledge) (Jackson et al., 2022). L&D can be driven by slow onset changes like sea level rise and droughts, or extreme and sudden events like cyclones and heat waves.

Understanding how people experience climate-induced L&D within their culturally specific contexts and places is paramount going forward (Tschakert et al., 2017; van Schie et al., 2023b). A better understanding of what is meaningful to people helps us understand limits to adaptation, what risks and impacts are perceived as acceptable, tolerable, and intolerable, and how individuals, communities, and societies prioritise risk reduction, risk transfer, adaptation, and restoration efforts (Tschakert et al., 2017). L&D praxis based on what people value in their everyday lives and what they consider worth preserving is critical (Tschakert et al., 2017). Conceptually, framing losses around localised values shifts the narrative to in-situ and localised expressions of loss, moving beyond the measurable and quantifiable. The approach taken in this study builds on such insights towards the everyday, place-based, and emotively attentive explorations of L&D, challenging the orthodoxy of L&D to date.

This study aims to explore people’s values and how they are affected by climate change, and identify locally meaningful priorities for funding and action. To do so, we utilise a values-based approach, which centres what people hold dear to them and considers these things of value in the context of everyday experiences of climate change. In a recent study, van Schie et al. (2023b) emphasised the significance of a local values-based approach for assessing L&D. The study, conducted in Bangladesh and Fiji, highlighted that using a values-based approach ensures that people’s experiences and perspectives are driving locally meaningful responses.

The Paris Agreement lays out a provision to help parties avert, minimise, and address L&D associated with the adverse effects of climate change (Chandra et al., 2023). It formalises the Warsaw International Mechanism, which was established at COP19 (December 2013) as the mandated institutional mechanism under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and the Paris Agreement to address L&D (UNFCCC, 2016). The historic and long-awaited decision at COP27 (December 2022) to establish and operationalise a global L&D fund was promising. The transitional committee, which was established in March 2023, worked to develop institutional arrangements and governance, define the funding arrangements and sources of funding, and ensure coordination with existing funding arrangements throughout the year (UNFCCC, 2023). At COP28 (December 2023), the global L&D fund was established with parties providing commitments to the fund.

This paper speaks directly to those involved in establishing the methodologies and assessments as part of the global L&D fund. As much-needed L&D support and finance starts to flow, it is important that decision-makers see the utility of a values-based approach for assessing and responding to L&D. We focus our attention on the Pacific Islands region which is experiencing and responding to significant and multiple climate change impacts such as sea level rise, increasing temperatures, increasing intensity of tropical storms and cyclones, ocean acidification, changes in rainfall patterns, and changes in inter-annual climate variability (Mycoo et al., 2022). All emission projections show that these climatic changes will rapidly increase over the next century. The impacts of these changes on human and ecological systems are increasingly dramatic and include declining food and water security, loss of agricultural lands, human health implications, threats to critical industries such as tourism, economic losses, and damage to coastal infrastructure and human settlements (see early study by Nunn, 2013).

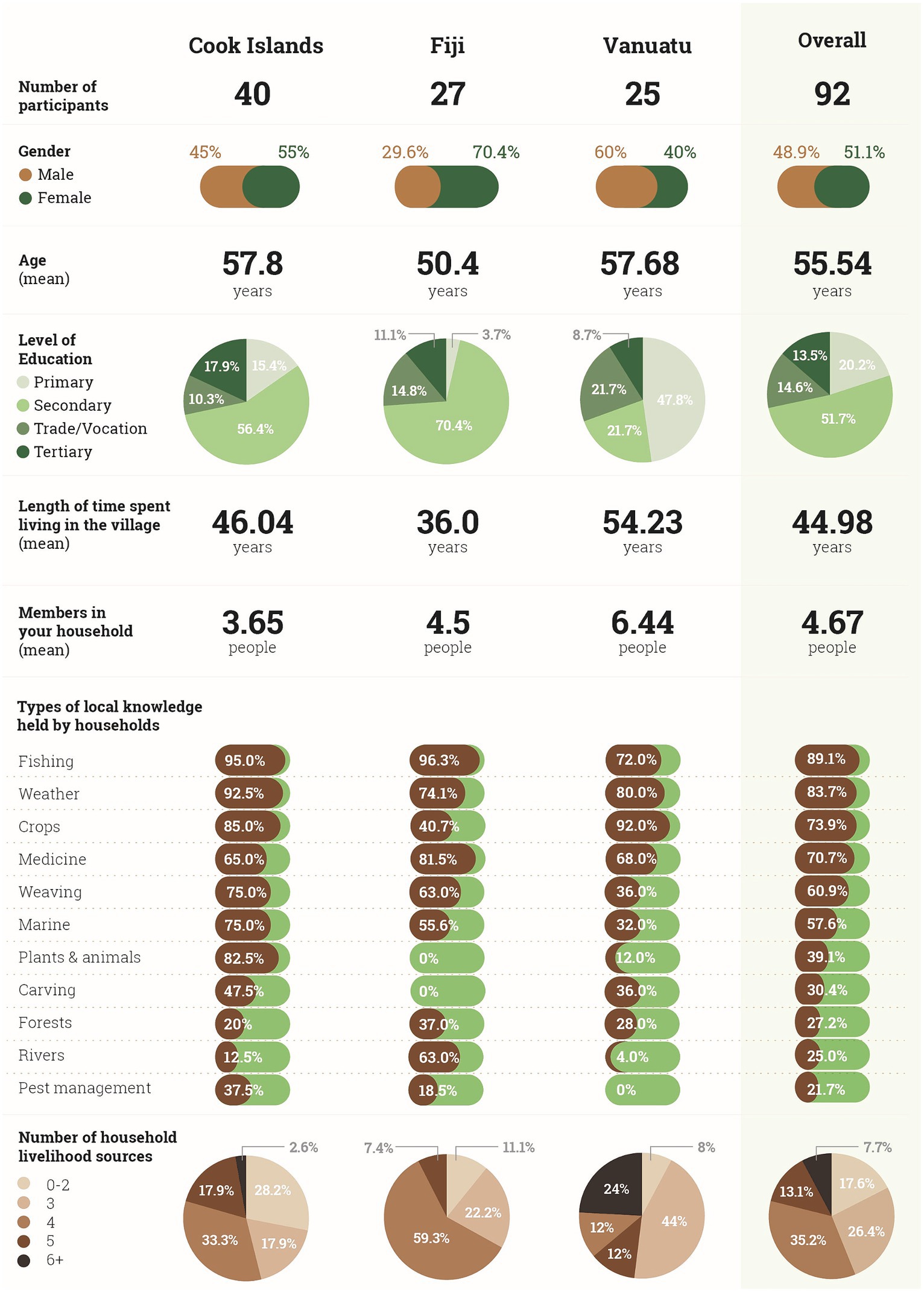

The policy recommendations that we make here are based on in-depth, semi-structured interviews with 92 locals living in the Cook Islands (in Mangaia, Mitiaro, Manihiki, Penrhyn, Pukapuka, and Rakahanga), Fiji (in Viti Levu and Vanua Levu), and Vanuatu (in Efate and Tanna). These interviews were conducted in relevant local languages, predominately in people’s homes, and lasted between one and two hours in length. They were undertaken between January and July 2023, and recorded and transcribed into Microsoft Word. Quantitative data was analysed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) v28, and qualitative data was coded and analysed using NVivo v12 to identify key storylines and themes. Human ethics approval for the study was granted from The University of Queensland (approval number: 2020000640) and participants consented to participate in this study. A research permit was granted for each country. Across all three countries, men, women, youth, and a few elderly participants were identified to ensure that a diversity of responses were collected (Figure 1). We focus on the differences and similarities in values between these countries, but are limited in our capacity to explain other drivers of differences in values and what is subsequently considered tolerable, intolerable, or acceptable. This is an important area to explore in more detail in future studies.

Policy must appreciate what is considered valuable in people’s lives

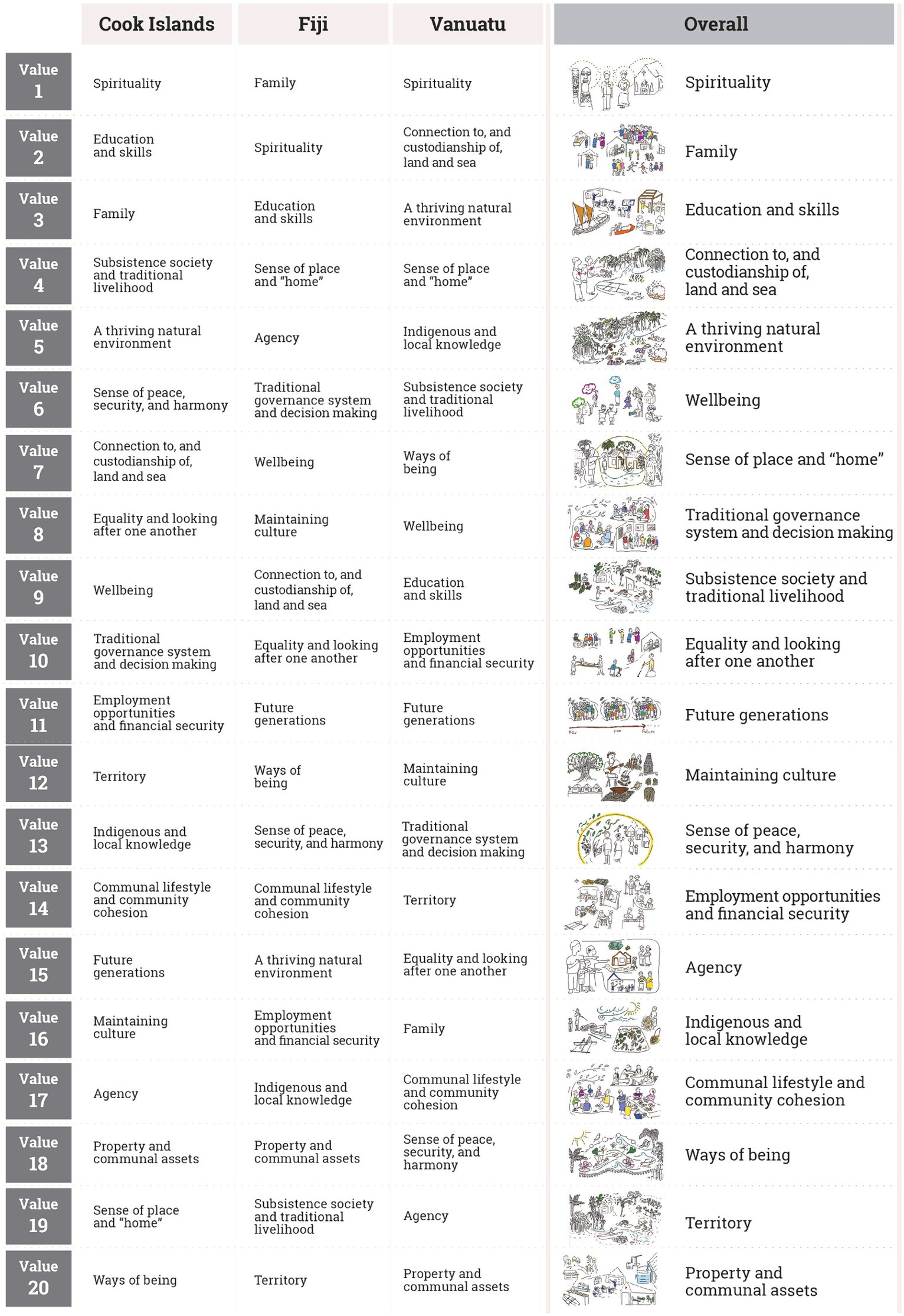

Values reflect a judgement by an individual or community on what is important in life. A list of relevant “values” in the Pacific was developed through a literature review and then discussed, validated, and fine-tuned with local research partners in the country case study sites. After several rounds of input and debate, 20 local values were selected. As part of the in-depth interviews, all 92 participants were asked to rank the 20 values from most to least valuable. These values were complemented with illustrations to support discussion and had descriptions in English and the local language to enhance understanding.

Figure 2 summarises what is most important to participants according to country and overall (i.e., the average scores across all three countries). There are differences in how these values were ranked across country sites, between communities and individuals. People do not necessarily share or prioritise the same values because experiences and daily practices influence them, as does the place and culture in which they are embedded (Adger et al., 2009; Barnett et al., 2016). People also do not necessarily hold the same values, and prioritise them in the same way, throughout their entire lives, highlighting how values are often not static.

Figure 2. Ranking of participant values by country and overall (i.e., average score across all three countries), including complementary illustrations used to support discussion.

Spirituality was the most highly ranked value overall (first in the Cook Islands and Vanuatu and second in Fiji). This highlights how spirituality is the foundation of culture, identity, and lifestyle. As explained by one participant:

Christianity is very important to bring everybody together and is a means of guidance and peace in the community. It is one of the pillars of the ruling system of the Cook Islands people and has always been upheld on all islands (#61, 41-year-old Penrhyn male, Cook Islands)

Other participants shared how spirituality provides the foundation for family, culture, livelihoods, and peace:

Been brought up in a Christian life and close community knit environment, everything has been about sharing, our culture and this has been ingrained in me (#31, 70-year-old Mangaia male, Cook Islands)

My belief has always been that God is the core of our life, and everything comes after that. Keeping our traditional way of life maintains our livelihood and respecting each other keeps us at peace with each other and is strong grounds for everything that comes after (#33, 66-year-old Mangaia male, Cook Islands)

Family was ranked second overall, and was particularly valued in Fiji and the Cook Islands (first and third respectively). In Vanuatu, family ranked lower at sixteenth, which may have been the result of a different interpretation of the value, with many ni-Vanuatu participants referring to family in the context of a family tree, family history and stories of the past, as opposed to their existing social units and support system. For many participants from Fiji and the Cook Islands: “Everything starts in the home” (#38, 49-year-old Mangaia female, Cook Islands). In this way, family is at the epicentre of all other inter-related values in life:

When you put one’s family at the centre, you make sure that you would do anything to protect your family. Family can offer support and security with love. That can contribute to positive wellbeing. Family is the springboard to a thriving life (#9, 35-year-old Sese male, Fiji)

Family also plays a vital role in preserving identity, kinship, community, and cultural practice, as summarised by one participant:

Family is important – this is the foundation of [a] better life. In this level, the members are taught their identity, their role in the family, and the village… Because they know their role and identity, this contributes to the maintenance of culture and practices (#12, 72-year-old Sese male, Fiji)

Education and skills were ranked third overall, with particularly high rankings in the Cook Islands (second) and Fiji (third). In Vanuatu, education was ranked lower at ninth. Ni-Vanuatu participants tended to emphasise the importance of education and skills development for one’s own life and opportunities: “…it helps us to survive in the bush, water or in our daily life” (#1, 88-year-old Erakor female, Vanuatu). This was similarly emphasised in Fiji and the Cook Islands: “[it’s] very important in moving forward in life” (#67, 69-year-old Rakahanga female, Cook Islands). The higher ranking in the Cook Islands and Fiji may be due to the extension of the importance of education and skills to family units and entire communities. It is, for example, considered critical to a family unit’s “brighter future” as education and skills development allow people to “get good jobs and be able to look after their children and their grandchildren… life in the future is definitely not going to be easy… I need to prepare my children for the future” (#4, 40-year-old Togoru female; #6, 38-year-old Sese female, Fiji). Benefits also extend to society in Fiji, where education was highlighted as: “The key to a thriving society [is] when one is educated” (#4, 40-year-old Togoru female, Fiji).

Custodianship of land and sea was ranked fourth overall, and was particularly valued in Vanuatu (second) compared to the Cook Islands (seventh) and Fiji (ninth). As one participant from Vanuatu shared: “The sea is very important to us because it gives us food and meat, as well as medicine, as well as our land. It is our life” (#68, 88-year-old Erakor female, Vanuatu). This connection to land and sea is powerful for a sense of belonging: “It is through the connection that I have in my land and sea I am able to live here, and I feel like I belong” (#74, 58-year-old Erakor male, Vanuatu). In Fiji, despite being ranked lower, connections with land and sea were still perceived as valuable for a fruitful life, especially in interaction with other values: “when one is groomed with spiritual values and connection to land and sea with a spoonful of education and skills – will lead to a thriving future” (#13–17, 28-69-year-olds Sese females, Fiji). Another participant highlighted how spirituality was about being “a better person for my family, village and the environment under my care”, insinuating that environmental stewardship is an important component of spirituality for some (#12, 72-year-old Sese male, Fiji).

A thriving natural environment was also ranked highly as fifth overall, although was much higher in Vanuatu (third) and the Cook Islands (fifth) than in Fiji (fifteenth). This important value is centred around: “Taking care of what we have – ‘taporoporo’, meaning conserve” (#52, 49-year-old Penrhyn male, Cook Islands). Benefits from a thriving natural environment are essential to supporting and maintaining people’s livelihoods and wellbeing:

Our land and sea are very important to us because it is like our resources that we depend on. We do not necessarily need cash or money in our hands, but as long as we have these resources, we have money. These resources are our banks, and we get them any time we want to earn money and exchange for services and other needs we want. For example, if I want to buy a bag of rice, I go to my pandanus tree, get some pandanus leaves, prepare it, and weave a mat and sell, then I go to the shop and buy a bag of rice (#73, 76-year-old Erakor male, Vanuatu)

Despite not being ranked highly in Fiji, the theme of protecting the environment emerged within discussions for other values, such as under spirituality and education and skills, as these were considered important values for promoting environmental stewardship: “it [education] provides the mentality of a changed and better future…how to treat others and the natural environment” (#4, 40-year-old Togoru female, Fiji).

Significant differences between countries were also found in the extent of meaning attributed to a subsistence society (fourth in the Cook Islands, sixth in Vanuatu, and nineteenth in Fiji), agency (fifth in Fiji, seventeenth in the Cook Islands, and nineteenth in Vanuatu), and ways of being (seventh in Vanuatu, twelfth in Fiji, and twentieth in the Cook Islands), among others. Drivers of differences in, and changes to, values should be explored further in future studies.

Policy must appreciate that values shape acceptable, tolerable, and intolerable impacts

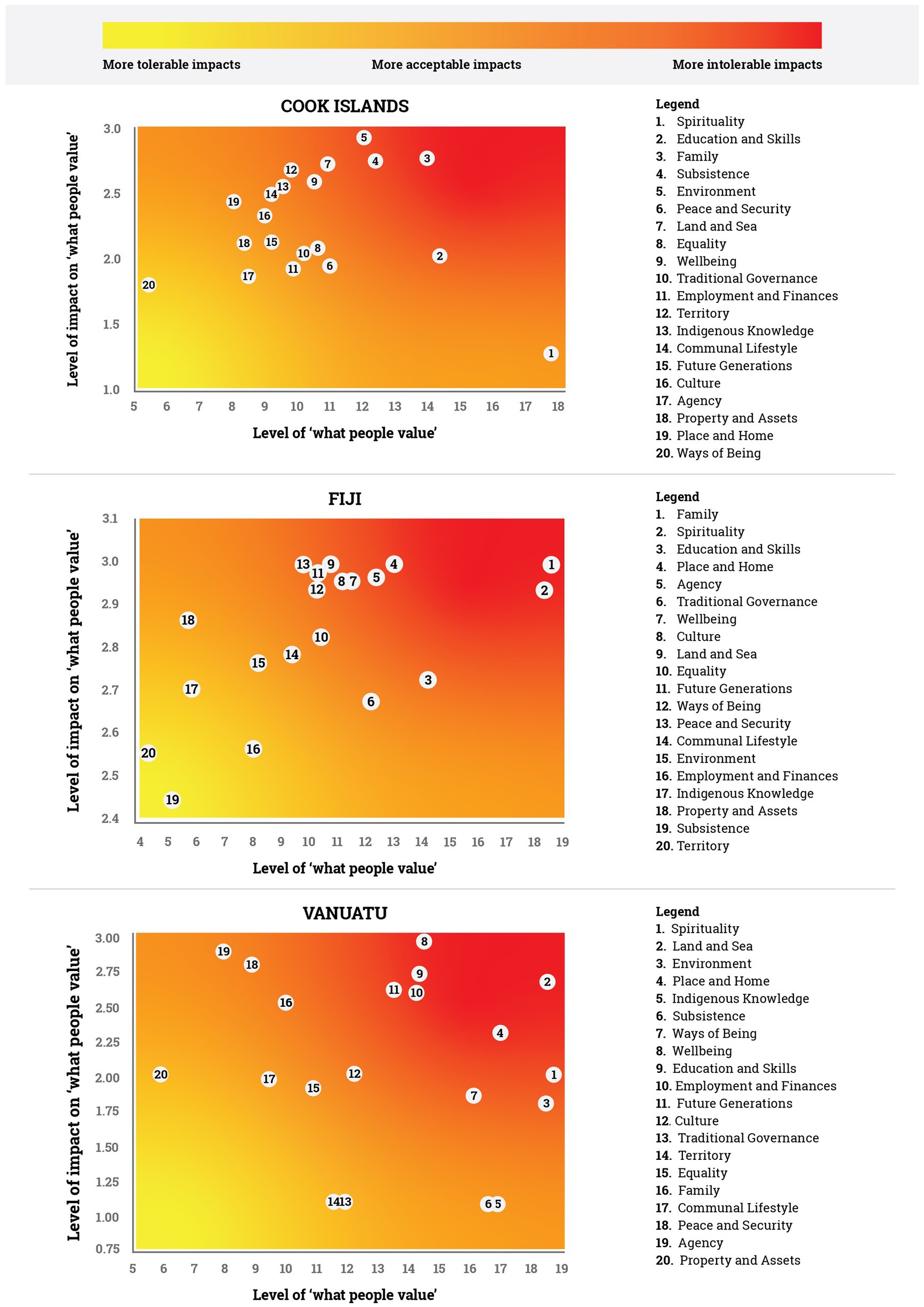

Participants were asked to reflect on how climatic stressors and associated impacts were affecting what they value, on a scale of 1 (least affected), 2 (somewhat affected), and 3 (most affected). Understanding how climate change affects what matters the most to people helps reveal – at a point in time – what is more acceptable, tolerable, and intolerable for people in the face of climate change (Tschakert et al., 2017). When a highly valued object is most affected by climatic impacts, and the measures used to cope or adapt to such impacts are not effective or exhausted, the impacts can become intolerable, and L&D becomes unavoidable.

Figure 3 illustrates the relationship between what is most important to people and the severity of climate change impacts on that value. Intolerable impacts are different for the case studies in each country, demonstrating the need for locally identified and place-based strategies for responding to, minimising, and addressing L&D. It is important to also emphasise that Figure 3 depicts the average values across communities within a specific period of time. It illustrates the multiple values at risk from climate change that people can hold at once, and that this can result in value prioritisation and trade-offs, determining where resources might be allocated to cope (O’Brien and Wolf, 2010; Tschakert et al., 2017). Values in reality are complex, with tensions between individuals and groups, and within communities, in how values are prioritised. Values also change over time based on the risk of their loss and the effectiveness of adaptation, and other social, environmental, political, and economic changes (Tschakert et al., 2017).

Figure 3. The relationship between what is valuable to people and the severity of climate change on that value to identify what impacts are considered to be more acceptable, tolerable, and intolerable in the Cook Islands, Fiji, and Vanuatu.

In the Cook Islands, while the impacts on ways of being and agency were considered more acceptable, the linked impacts on family, subsistence society and traditional livelihoods were considered intolerable. The intolerable impacts on subsistence society and traditional livelihoods were explained in the context of food insecurity, health, and wellbeing:

No rain, sometimes for up to over six months… Breadfruit trees, a livelihood for the island is dying, there are just a few left. The coconut trees on the motus are not bearing fruits and there is no coconut or uto (new coconut shoots) on the ground. This is the most important diet of our people. The water ponds on the motus have dried up and the fish (ava) that live in these ponds have died. This is also an important diet of the people (#59, 62-year-old Penrhyn female, Cook Islands)

Coconut trees are providing less fruits, fishing is getting worse. You’d be lucky today but the rest of the week or month you may not catch anything. Planting can be hard to do in our home at this time. It may rain today only to fill up a 50-litre bucket, sometimes it will never rain for about 2 to 3 months, and this is getting worse every year now (#56, 33-year-old Penrhyn female, Cook Islands)

These were then linked to the intolerable impacts on family, as participants were growing increasingly concerned about being unable to meet their family’s needs:

When the land is dry you have nothing to feed your family or the less fortunate people… When I have no extra food crops or fish to share to my people, I feel so low, or hopeless. I sometimes get angry unnecessarily. No extra money for my family, nothing to share and sometimes get to the stage of leaving the island and going overseas (#36, 63-year-old Mangaia male, Cook Islands)

Today, I have found that due to these changes in weather, it is causing suffering for my people, as it is hard to find food for our family, hard to get fish, hard to get taro, even we are continuously planting food crops, because when it doesn’t rain, the crops die. Of course, we cannot continue on feeding our families with coconut and uto everyday, and we cannot continue going to the shops for rice, flour and corn beef or tinned fish, they are expensive, we also want some money to upgrade our houses and other important things for the home. This is a sad story we are experiencing on our island (#65, 45-year-old Pukapuka male, Cook Islands)

As a result of less rainfall and longer dry periods, participants have faced the interrelated challenges of food insecurity, water insecurity, and declining health and wellbeing. Also, the inability to partake in communal sharing practices, such as sharing abundant food, has strained social cohesion, cultural practices, and community wellbeing.

In Fiji, the most intolerable impacts were those related to family and spirituality, while the impacts considered more acceptable at this stage related to subsistence lifestyles. The intolerable impacts on family and spirituality manifested in diverse ways, however, they were most often discussed in relation to losing sacred places such as burial grounds: “The sea has drowned the graves of their forefathers” (#3, 61-year-old Togoru female, Fiji). Participants expressed the substantial impacts on wellbeing and mental health because of losing these burial grounds:

Our loved ones who have passed away – when we bury them, we say “sili vakarua” (bath twice) because one is they bath before they are put into the coffin, and they bath again after they are buried as the waves come in and enter the new burial site. This is just traumatising for us (#1, 65-year-old Togoru female, Fiji)

The Togoru community moved the burial grounds to cope with this, but the second site had also been impacted by seawater. Locals in Sese village have had similar experiences. Their first burial ground is underwater, the second one exists but it is precariously situated on the shoreline edge, and the third one has been established on a hilltop that is less accessible from the village. For participants, losing these burial grounds is considered intolerable as it threatens their connection to loved ones and the continuity of traditions, and the measures used to cope and adapt are not proving effective long-term.

And lastly, for the two case study sites in Vanuatu, connection to and custodianship of land and sea, and wellbeing were the most intolerable impacts. A lost connection to and custodianship over land and sea has cascading impacts on other important and valued aspects of life as it is through this connection that “I feel like I belong,” “[that] I am connected to my resources and wealth” and it is “through the land and sea that I have food everyday… it is like my mother who feeds me every day” (#74, 58-year-old Erakor male, Vanuatu; #71, 61-year-old Erakor female, Vanuatu; #70, 61-year-old Erakor male, Vanuatu). Several participants highlighted how maintaining a sense of custodianship over land and sea is central to protecting their lives and livelihoods in general: “We need everyone’s assistance in whatever capacity they can muster in order to safeguard and maintain the lagoon. Because the majority of us rely on the lagoon for sustainable life, protecting it is one of the things I value most” (#70, 61-year-old Erakor male, Vanuatu). Wellbeing is also important as it is needed for participation in other life activities and engaging with other things that are valued: “I am happy when I am healthy and when you are healthy you can participate in physical, mental and your cultural activities” (#84, 40-year-old Tanna male, Vanuatu).

Policy must appreciate that values must drive responses to loss and damage

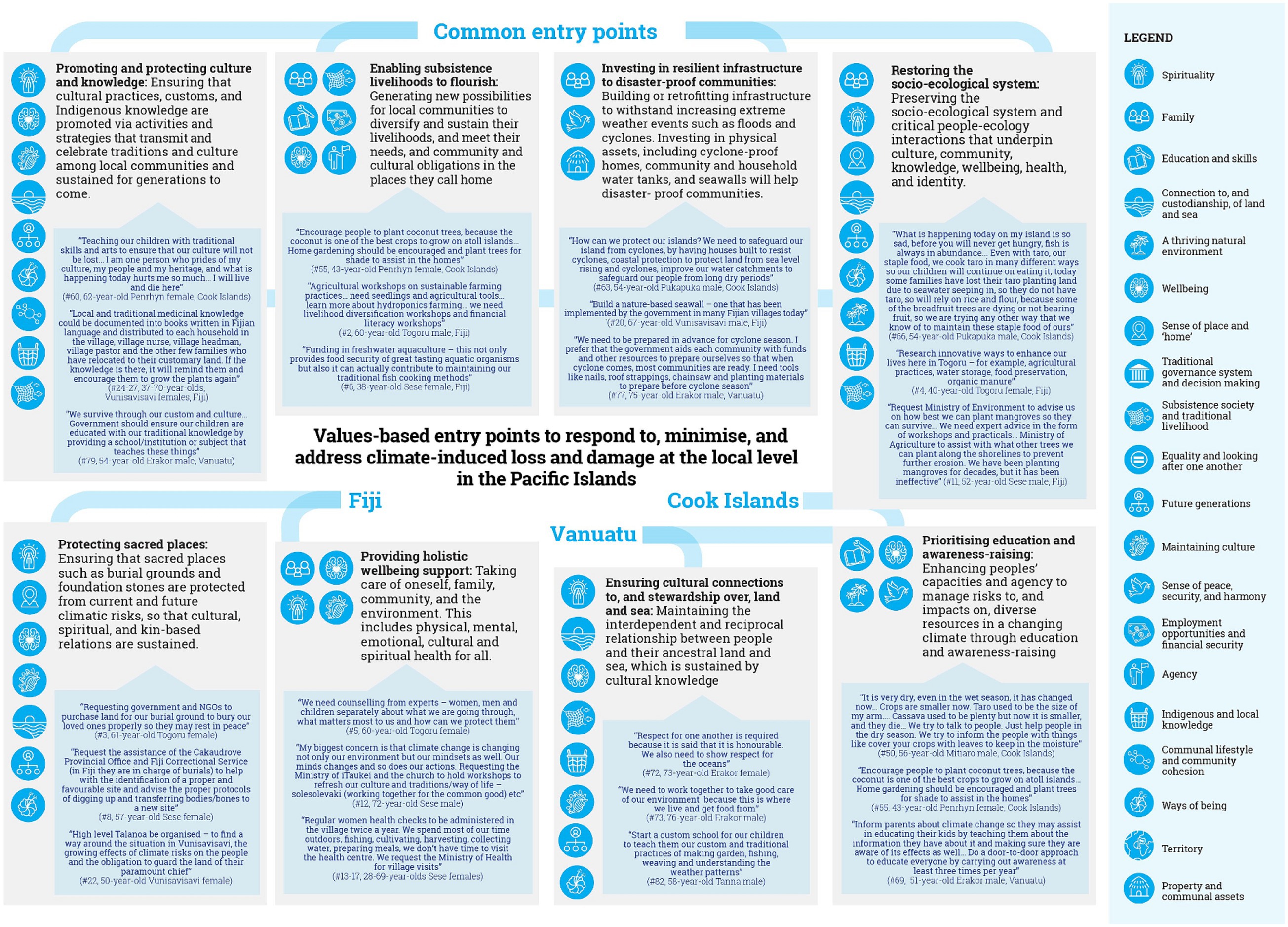

Scholarship has noted how responding to L&D, particularly the non-economic aspects, can be very difficult (Jackson et al., 2022). This study builds on newly-emerging work that starts to chart how locally-driven entry points can be identified to address L&D (see for example McNamara et al., 2023).

Figure 4 summarises critical values-based and locally identified entry points for minimising and addressing climate-driven L&D, particularly the most intolerable impacts. It emphasises where there are overlaps and crossovers in the entry points, especially in relation to promoting and protecting culture and knowledge, enabling subsistence livelihoods to flourish, investing in resilient infrastructure, and restoring socio-ecological systems. Across all three case studies, these strategies are addressing impacts to several values including culture, employment and financial security, wellbeing, environment, and land and sea, which are just falling into or edging towards the intolerable category, or impacts to property and assets which although are not considered intolerable, are experiencing a high level of impact across the sites.

Figure 4. Common and place-specific entry points to respond to climate-driven loss and damage in the Cook Islands, Fiji, and Vanuatu.

Figure 4 also highlights the place-specific differences for the Cook Islands, Fiji, and Vanuatu, again reinforcing the need for locally identified, place-based responses. In Fiji, there was a stronger emphasis on protecting sacred places, which are clearly driven by the prioritised value of spirituality, and the intolerable loss experienced to burial grounds, which are also affecting wellbeing, culture, connections to land and sea, future generations, sense of place, and ways of being – values which are also sitting on the edge of being intolerable. Although not necessarily the highest ranked value for Fijians, the emphasis on holistic wellbeing support is a clear response to the high level of impact on this value, which places it close to being an intolerable loss. Participants from the Cook Islands and Vanuatu also emphasised education and awareness-raising as integral to adaptation and resilience-building; reflecting the perceived importance that participants place on education and skills for survival, opportunities, and a thriving life. Although not emphasised by participants, the values analysis suggest that education and awareness-raising would also be a critical response strategy for L&D in Fiji. Vanuatu also highlighted the importance of ensuring cultural connections to, and stewardship over, land and sea. This reflects the much higher value rankings placed on land and sea, and the environment compared to the Cook Islands and Fiji, and the relatively high level of impact, making them intolerable. The trickling benefits that this entry point can have for other highly ranked values in Vanuatu, such as wellbeing, Indigenous knowledge, and subsistence also contribute to why this was a locally relevant response strategy.

Actionable recommendation: the need for a values-based approach to address loss and damage

What people value is critical in understanding how the impacts of climate change affect people’s everyday lives, now and in the future. That is, what people value determines what is considered intolerable, tolerable, and acceptable in terms of climate-induced L&D. This should, therefore, inform which responses should be prioritised and where resources should be allocated to preserve the things that matter most to people in the face of climate risk.

Intolerable impacts differ from place to place, given people’s different value sets and experiences of climate change across places, cultures, and contexts. This highlights that our understanding of intolerable impacts, and prioritisation for funding, resources, and action, is also highly context-dependent. As such, responses to minimise and address L&D must be locally identified and led to ensure they are locally meaningful, adequately building on people’s place-based experiences, cultures, contexts, and values (as done in the above section).

There are limited finance options for addressing L&D (Bakhtaoui et al., 2022). The new global L&D fund must ensure that funding is made available for locally-driven interventions to minimise and address L&D (van Schie et al., 2023a). We recommend that a values-based approach be utilised in assessments and methodologies for funding in the new global L&D fund. This will ensure that efforts are local, place-based and target and preserve the things that are most meaningful to people.

Conclusion

Values play a critical role in defining what shapes risks, limits, and L&D. By better aligning adaptation and risk mitigation efforts with people’s values, we can help avert, minimise, and address L&D in ways that sustain or enhance the aspects of life that are most valued. A values-based approach acknowledges that climate change impacts cannot continually be assessed or measured through objective scientific methods, economic analysis, or responded to in a universal way. It “recognises and makes explicit that there are subjective, qualitative dimensions to climate change that are of importance to individuals and cultures” (O’Brien and Wolf, 2010, p. 235).

As this study has shown, L&D is not only experienced locally but these experiences differ according to different contexts. This presents a strong case for a contextualised consideration of values, meaning that understanding and responding to L&D in contexts across the globe must be locally identified and led.

A values-based approach provides a locally meaningful method that can be transferred and used in countries across the world to understand and respond to L&D in ways that integrate the priorities and needs of local people. In the case study sites in the Cook Islands, Fiji, and Vanuatu, several locally identified entry points for minimising and addressing L&D were identified, particularly to respond to intolerable impacts. These values-based entry points included resilient infrastructure to disaster-proof communities, enabling subsistence livelihoods to flourish, protecting culture and Indigenous knowledge, and restoring the socio-ecological system, among several specific place-based initiatives. Decision-makers in other contexts and countries can draw on this approach to draw similarly locally relevant and meaningful entry points to respond to L&D.

Author contributions

KM: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. RC: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. RW: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. MY: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Investigation, Conceptualization. TM: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Investigation. VW: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Investigation. VO: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Investigation. PM: Writing – review & editing, Investigation. ER: Writing – review & editing, Investigation. MN: Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This research was funded through an Australian Research Council Future Fellowship grant (grant number FT190100114).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Adger, W. N., Dessai, S., Goulden, M., Hulme, M., Lorenzoni, I., Nelson, D. R., et al. (2009). Are there social limits to adaptation to climate change? Clim. Chang. 93, 335–354. doi: 10.1007/s10584-008-9520-z

Bakhtaoui, I., Shawoo, Z., Chhetri, R. P., Huq, S., Hossain, M. F., Iqbal, S. M. S., et al. (2022). Operationalizing finance for loss and damage: from principles to modalities. SEI Report. Stockholm Environment Institute, Stockholm.

Barnett, J., Tschakert, P., Head, L., and Adger, N. W. (2016). A science of loss. Nat. Clim. Chang. 6, 976–978. doi: 10.1038/nclimate3140

Chandra, A., McNamara, K. E., Clissold, R., Tabe, T., and Westoby, R. (2023). Climate-induced non-economic loss and damage: understanding policy responses, challenges, and future directions in Pacific Small Island developing states. Climate 11, 74–99. doi: 10.3390/cli11030074

Jackson, G., van Schie, D., McNamara, K. E., Carthy, A., and Ormond-Skeaping, T. (2022) Passed the point of no return: a non-economic loss and damage explainer. Loss and Damage Collaboration, London. pp. 1–24. Available at: https://www.lossanddamagecollaboration.org/publication/passed-the-point-of-no-return-a-non-economic-loss-and-damage-explainer

McNamara, K. E., Clissold, R., Westoby, R., Stephens, S., Koran, G., Missack, W., et al. (2023). Using a human rights lens to understand and address loss and damage. Nat. Clim. Chang. 13, 1334–1339. doi: 10.1038/s41558-023-01831-0

Mycoo, M., Wairiu, M., Campbell, D., Duvat, V., Golbuu, Y., Maharaj, S., et al. (2022). “Small Islands” in Climate change 2022: impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability. Contribution of working group II to the sixth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change. eds. H. O. Pörtner, D. C. Roberts, M. Tignor, E. S. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, et al. (Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA: Cambridge University Press), 2043–2121.

Nunn, P. D. (2013). The end of the Pacific? Effects of sea level rise on Pacific Island livelihoods. Singap. J. Trop. Geogr. 34, 143–171. doi: 10.1111/sjtg.12021

O’Brien, K. L., and Wolf, J. (2010). A values-based approach to vulnerability and adaptation to climate change. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Change 1, 232–242. doi: 10.1002/wcc.30

Roberts, E., and Huq, S. (2015). Coming full circle: the history of loss and damage under the UNFCCC. Int. J. Global Warming 8, 141–157. doi: 10.1504/IJGW.2015.071964

Tschakert, P., Barnett, J., Ellis, N., Lawrence, C., Tuana, N., New, M., et al. (2017). Climate change and loss, as if people mattered: values, places, and experiences. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Change 8, 1–19. doi: 10.1002/wcc.476

UNFCCC (2016) Adoption of the Paris agreement FCCC/CP/2015/10/add.1. 1–32, UN Climate Change Secretariat, Available at: https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/generalassembly/docs/globalcompact/FCCC_CP_2015_10_Add.1.pdf

UNFCCC (2023) Transitional committee, Available at: https://unfccc.int/topics/adaptation-and-resilience/groups-committees/transitional-committee

van Schie, D., Jackson, G., Candelon, P., Ayeb-Karlsson, S., Bakhtiari, F., Boyd, E., et al. (2023a) “Underemphasised and undervalued”: ways forward for non-economic loss and damage within the UNFCCC. Loss and Damage Collaboration, London, pp. 1–8.

van Schie, D., McNamara, K. E., Yee, M., Mirza, A. B., Westoby, R., Nand, M. M., et al. (2023b). Valuing a values-based approach for assessing loss and damage. Clim. Dev., 1–8. doi: 10.1080/17565529.2023.2289533

Keywords: climate change impacts, Pacific Islands region, non-economic loss and damage, values, intolerable impacts

Citation: McNamara KE, Clissold R, Westoby R, Yee M, Mariri T, Wichman V, Obed VL, Meto P, Raynes E and Nand MM (2024) Values must be at the heart of responding to loss and damage. Front. Clim. 6:1339915. doi: 10.3389/fclim.2024.1339915

Edited by:

Jose Antonio Rodriguez Martin, Instituto Nacional de Investigación y Tecnología Agroalimentaria (INIA), SpainReviewed by:

Vahid Karimi, Tarbiat Modares University, IranMia Wannewitz, Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich, Germany

Copyright © 2024 McNamara, Clissold, Westoby, Yee, Mariri, Wichman, Obed, Meto, Raynes and Nand. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Karen E. McNamara, a2FyZW4ubWNuYW1hcmFAdXEuZWR1LmF1

Karen E. McNamara

Karen E. McNamara Rachel Clissold1

Rachel Clissold1 Precilla Meto

Precilla Meto